Abstract

Magnetic miniature robots hold great potential for minimally invasive biomedical applications due to their small size and biocompatibility. However, single-modal robots face challenges in complex environments, while existing multimodal robots that rely on elastic materials lack kinematic stability and are sensitive to environmental factors. This work introduces a novel Multimodal Magnetic Miniature Robot (MMMR) which combines helical swimming with bipedal walking. The MMMR can adaptively navigate in diverse amphibious environments, including open liquids, shallow liquids, liquid surfaces, and solid surfaces. Owing to the structure-driven locomotion mechanism, the MMMR exhibits excellent kinematic stability. The helical swimming is optimized through simulations and enhanced with a closed-loop control system for height and directional correction. Bipedal walking is designed for adaptive locomotion on liquid and non-liquid surfaces. Experiments confirmed precise multimodal control, including swimming, walking to targets, and retrieval, offering a novel solution for miniature robots in diverse environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Untethered miniature robots actuated by external fields can achieve smaller sizes compared to those equipped with onboard components, enabling them to access narrow regions within the human body for minimally invasive medical tasks. At present, researchers have proposed various external field-actuated strategies, including magnetic fields1,2, optical fields3,4, electric fields5,6, acoustic fields7,8, etc. Among them, magnetic fields are safe for biological tissues, exhibit good tissue penetration, and enable real-time steering control9. Therefore, magnetic field actuation has gradually become a great strategy for externally actuated miniature robots in biomedical applications10,11.

In microscale environments, reciprocal swimmers like scallops cannot generate effective propulsion due to the constraints imposed by low Reynolds number dynamics12. Inspired by nature, Purcell demonstrated that prokaryotic organisms, such as E. coli13, can achieve effective propulsion in a Reynolds number environment by rotating their helical flagella. In14, three effective magnetic propulsion mechanisms operating in low Reynolds number environments, including magnetic field gradient pulling, helical swimming, and traveling wave swimming, are systematically evaluated. Among these, magnetic miniature robots with helical swimming demonstrated the highest propulsion efficiency and are identified as the most suitable choice for in vivo applications. Moreover, magnetic helical miniature robots offer advantages like low magnetic field intensity requirements and high directional controllability, making them a prominent branch in the field of magnetic miniature robots.

At present, various control strategies, including traditional control methods15,16,17 and learning-based methods18,19,20,21, have been applied to magnetic helical miniature robots. Also, novel structures22,23 and fabrication techniques24,25 for magnetic helical miniature robots have been continuously proposed. In terms of applications, magnetic helical miniature robots have been utilized as carriers in biomedical scenarios such as drug delivery26,27, cell delivery28,29, embolization therapy30,31, vascular clearance32,33, etc. However, current research still faces several limitations. For example, while magnetic helical miniature robots can maintain good directional controllability in uniform open spaces, their helical swimming is significantly disturbed near boundaries due to variations in shear friction forces. Furthermore, the stable swimming ability of magnetic helical miniature robots is restricted to liquid environments, as they are unable to achieve reliable motion in non-liquid scenarios. Therefore, if magnetic helical miniature robots can achieve multimodal locomotion by combining highly controllable directional swimming with precise surface walking capabilities, their functionality and range of potential applications could be greatly expanded.

Existing multimodal magnetic miniature robots often rely on soft material to achieve adaptive locomotion34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. In34, Hu et al. proposed a soft-bodied magnetic film robot capable of elastically responding to different magnetic field modes to achieve multimodal locomotion. Subsequently, this type of soft-bodied magnetic film robot has been further optimized35,36,37,38 and expanded for biomedical applications39. In ref. 42, Huang et al. combined soft magnetic films to propose a quadruped magnetic miniature robot capable of achieving multiple controllable locomotion modes under an external magnetic field. However, soft materials are often limited by their relatively low fabrication precision and susceptibility to environmental factors, such as temperature and pH levels. Additionally, these soft multimodal robots lack precise directional controllability, which makes accurate navigation difficult to achieve. Therefore, designing a multimodal magnetic miniature robot whose locomotion mechanism does not rely on soft material can significantly enhance its environmental adaptability and navigation capabilities. In recent years, some bipedal magnetic miniature robots capable of surface walking have demonstrated excellent directional controllability43,44,45.

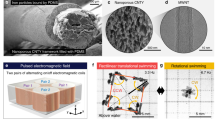

Inspired by previous research foundations, this work introduces a Multimodal Magnetic Miniature Robot (MMMR) that integrates helical swimming and bipedal walking, with its design and multimodal locomotion concept illustrated in Fig. 1. The MMMR has a radius of only 1 mm, which is smaller than most tubular structures in the human body, such as the urethra, intestine, and esophagus. Additionally, the MMMR is designed with an internal cavity, allowing for magnet embedding and drug loading. Consequently, the MMMR has the potential for adaptive navigation within internal organs, such as the stomach and fluid-filled organs like the bladder. Helical swimming is actuated by a rotating magnetic field, while bipedal walking is actuated by a fixed or variable oscillating magnetic field. MMMR expands the range of feasible locomotion scenarios beyond a single mode, enabling it to swim in liquids of varying depths, walk on submerged liquids or liquid-free surfaces, all with high directional controllability. Additionally, the structure-based locomotion mechanism ensures that MMMR is independent of material properties, allowing for flexible material selection and scalability in size.

The magnetization direction is perpendicular to the biped feet. A Multimodal locomotion in the stomach and bladder. B Liquid-in helical swimming under a rotating magnetic field. C Liquid-in bipedal walking under a variable oscillating magnetic field. D Liquid-free bipedal walking under a fixed oscillating magnetic field.

The proposed MMMR is comprehensively investigated. First, for the helical swimming, its locomotion mechanism is analyzed, and structural parameters are designed based on simulations. Then, the locomotion performance is experimentally evaluated, and a closed-loop automated control strategy is implemented to maintain height control during swimming in liquids and to provide directional control during swimming near liquid surfaces. Next, for the bipedal walking, force and locomotion mechanisms are analyzed, and adaptive magnetic field strategies are proposed for two walking scenarios: on liquid-in and liquid-free surfaces. Directional controllability is validated for both helical swimming and bipedal walking, with additional demonstrations showing the ability of MMMR to walk on slopes up to 30∘ and maintain stable locomotion performance regardless of internal loading. Finally, multimodal locomotion validation is conducted in an artificial bladder.

Results

Locomotion mechanism

In a spatially uniform magnetic field B, the magnetic torque acting on a magnet can be expressed as T = V(M × B), where V is the volume of the magnet and M is its magnetization. With the effect of the magnetic torque, the magnet aligns with the direction of the magnetic field. A magnet embedded in the MMMR induces a radial magnetization direction, which is perpendicular to the bipedal plane. As shown in Fig. 2A, when a rotating magnetic field (i.e., a uniform magnetic field rotating over time) is applied, the MMMR rotates about its axis due to the magnetic torque and reaches a torque equilibrium. Due to the helical structure of the MMMR, its rotation in liquid continuously pushes the liquid at the solid-liquid interface axially, enabling helical swimming in the liquid. In a low-Reynolds-number fluid environment, where inertial forces are nearly negligible12, helical swimming can be described using a simple linear propulsion matrix46:

where the propulsion coefficients a, b, c and d in the matrix represent drag factors related to the geometric parameters of the helical structure. Since the MMMR is solely subjected to magnetic torque, its helical swimming satisfies:

where φ is the angle by which the magnetization of the MMMR lags behind the rotating magnetic field (see Fig. 2A). From Equation (2), the propulsion speed v of helical swimming is linearly correlated with the rotational speed ω. Moreover, as the rotational speed increases, the lag angle φ also increases, reaching a maximum of 90 degrees, where the magnetic torque is at its peak. Beyond this point, further increases in rotational speed result in insufficient magnetic torque to overcome the drag torque, causing the MMMR to lose synchrony in its helical swimming. The frequency at which the magnetic torque reaches its maximum is referred to as the step-out frequency47.

A Helical swimming under a rotating magnetic field. φ is the angle by which the magnetization of the MMMR lags behind rotating magnetic field. B Static analysis in bipedal walking mode. Fv represents the volumetric forces acting on the MMMR like gravitational and buoyant forces, T is the magnetic torque. C Bipedal walking gait under an oscillating magnetic field.

The bipedal walking of the MMMR is achieved under an oscillating magnetic field (i.e., a uniform magnetic field oscillating over time). A static analysis is first conducted, as shown in Fig. 2B, where the two feet of the MMMR are supported by the ground. By controlling the angle of the magnetic field, a pitch angle is generated between the magnetization direction of the MMMR and the ground. Assuming the magnetic field oscillates counterclockwise, the torque equations of the MMMR can be expressed as follows:

where Fv represents the volumetric forces acting on the MMMR, like gravitational and buoyant forces, T is the magnetic torque and p is the pitch angle of the oscillating magnetic field. The distance between the two feet is 2r, where Fsr and Fsl are the support forces applied to the right and left feet, respectively. Based on these equations, the support forces for the two feet can be solved as:

When the external magnetic field oscillates counterclockwise, the support force on the right foot decreases as the magnetic torque increases, while the support force on the left foot correspondingly increases. Once the support force on the right foot reaches zero, the MMMR pivots on the left foot and steps forward with the right foot, as shown in Fig. 2C. The oscillating magnetic field then swings back clockwise, reversing the force distribution between the left and right feet. At this stage, the MMMR pivots on the right foot and steps forward with the left foot. Thus, under an oscillating magnetic field, the MMMR alternates between the left and right feet as pivot points, enabling bipedal walking. From Eq. (4), it can be seen that the key factor causing the difference in supporting forces between the left and right feet is the pitch angle. The larger the pitch angle, the greater the difference in supporting forces. However, the pitch angle also causes the rotating foot to lift off the ground. During liquid-free walking, the rotating foot quickly lands on the ground, serving as the supporting foot for the next step, as shown in Fig. 1D. However, during liquid-in walking, due to the effects of liquid resistance and buoyancy, the rotating foot cannot land quickly. If the supporting feet cannot alternate, the MMMR will fail to achieve effective walking. To address this issue, a variable pitch oscillating magnetic field is employed to achieve liquid-in walking, as shown in Fig. 1C. In this case, the MMMR leans its body forward during steps forward, forcing the rotating foot to land in time. After landing, the foot returns to a tilted-back posture to proceed with the next step.

Structural parameters design based on simulation

The helical swimming behavior of the MMMR in a liquid is primarily determined by its helical structural parameters. For a typical spring-like magnetic helix, previous studies have derived the propulsion coefficients a, b, c, d in Eq. (1) using resistive force theory (RFT) models46. Various resistance coefficients, such as those proposed by Gray48, Cox49, and Lighthill50, are commonly used in RFT. However, the helical structure of the MMMR significantly deviates from that of typical magnetic helices, making existing RFT models unsuitable for accurately describing its swimming behavior. Consequently, numerical simulations are employed to analyze the helical swimming dynamics of the MMMR.

A previous study51 proposed a dynamic transient simulation model to investigate the helical swimming of magnetic helices. However, dynamic simulations require substantial computational resources and are prone to convergence issues caused by deteriorating mesh quality during the simulation. For instance, in51, a single simulation could take up to 15 hours, resulting in extremely low computational efficiency. In this work, a numerical simulation method based on the frozen rotor and frozen translating object is developed. This method assumes steady-state flow, eliminating the need for the dynamic rotation and translation of the studied object. Instead, the object is fixed while rotational and translational states are assigned to the surrounding fluid, effectively simulating the relative motion between the object and the fluid. As a result, the helical swimming of the MMMR can be analyzed using steady-state simulations, reducing the computation time to just a few minutes.

The workflow of the numerical simulation method for MMMR helical swimming is illustrated in Fig. 3A. In this method, the frozen translating object assigns a specific flow velocity v to the fluid surrounding the MMMR (see Fig. 3B), while the frozen rotator assigns a specific rotational frequency f to the fluid (see Fig. 3C). Before performing formal simulations, a convergence analysis is conducted to evaluate potential boundary effects and mesh density, as detailed in Supplementary Appendix A. After calculation, the total hydrodynamic force and torque acting on the MMMR under these two conditions can be obtained, denoted as FT, TT, FR and TR. Subsequently, the corresponding propulsion coefficients can be determined based on Equation (1) as a = FT/v, b = TT/v, c = FR/(2πf) and d = TR/(2πf). Then, a simulation is performed using a typical spring-like magnetic helix, and the results are compared with three RFT models48,49,50, as shown in Fig. S1. The comparative analysis, elaborated in Supplementary Appendix B, validates the reliability of the proposed simulation method.

A Flowchart of the proposed numerical simulation method, where a, b, c, and d are parameters of the linear propulsion matrix (1). B Fluid flow induced by the frozen translating object when v = 5mm/s. C Rotational flow induced by the frozen rotator when f = 10Hz.

In the helical swimming of MMMR, the swimming velocity at the same rotational frequency can characterize its propulsion efficiency. By obtaining the propulsion coefficient through simulations, the relationship between rotational frequency and swimming velocity can be determined using Equation (2). First, an initial simulation object is defined, as shown in Fig. 4A: a helical body of MMMR with a radius R = 1 mm, length H = 3 mm, and inner cylinder radius Rc = 0.7 mm. These parameters are predetermined primarily based on the application scenario and the size of the embedded magnet. Then, as shown in Fig. 4A, simulations are conducted for four different helical thicknesses h. The results indicate that as h increases, the propulsion efficiency of the MMMR helical body gradually decreases. Structural analysis reveals that an increase in h reduces the volume of fluid displaced during swimming, thereby lowering propulsion efficiency. Comparatively, when h/R = 0.3, there is no significant decrease in propulsion efficiency. However, further decreasing h/R results in excessively thin helices that are prone to breakage during fabrication. Therefore, the final parameter is set to h/R = 0.3. Fig. 4B compares the simulation results for four different helix turn numbers n. Since the helix must maintain symmetry, the number of turns needs to be an integer multiple of 0.5. The simulation results show that an excessive number of helical turns significantly reduces propulsion efficiency. This occurs because the presence of the helical thickness h causes the volume of fluid displaced during swimming to decrease as the number of turns increases. Additionally, the difference in propulsion efficiency between n = 0.5 and n = 1 is minimal. Ultimately, the number of turns is set to n = 1, as too few turns can lead to instability during low-frequency rotations, making the helix more prone to wobbling. In Fig. 4C, an elliptical tip is added to the MMMR helical body, primarily to lower the overall center of gravity (CG) of the helix and enhance its stability during bipedal walking. As shown in Fig. 2, the MMMR requires a pitch angle during bipedal walking. If the CG is too high, it becomes prone to tipping over. Simulations compared four different elliptical tip lengths b, and the results indicate that gradually increasing the length of the elliptical tip has no significant impact on the propulsion efficiency of helical swimming. Therefore, b/R = 3 is chosen, which lowers the CG relative to the length H by 21.3% without significantly reducing propulsion efficiency. In Fig. 4D, simulations are performed after incorporating bipedal feet into the helical body. The results indicate that the addition of bipedal feet has no significant effect on the propulsion efficiency. Additionally, the propulsion efficiency is assessed in fluids with different viscosities, and the simulation results demonstrated consistency across all cases. This is consistent with the predictions of RFT theory, which posits that the propulsion efficiency of helical swimming is determined solely by the structural design and remains unaffected by fluid viscosity47.

A Effect of helical thickness h on propulsion efficiency in simulation. B Effect of helix turn numbers n on propulsion efficiency in simulation. C Effect of elliptical tip length b on propulsion efficiency in simulation. D Effect of bipedal feet and liquid viscosity on propulsion efficiency in simulation.

Helical swimming evaluation

As shown in Fig. S4, the MMMR is fabricated after optimizing its parameters through simulations, with an overall size of ϕ 2 mm × 3.2 mm. The helical swimming of the MMMR is then evaluated experimentally. The magnetic actuation system employed a 3-axis Helmholtz coil setup, capable of generating highly uniform magnetic fields within the central region. The position and orientation of the MMMR are tracked using a top-view camera (xy-plane) and a side-view camera (xz-plane), as illustrated in Fig. S4C. To simulate a low Reynolds number environment, glycerin with a viscosity of approximately 1000 cP is used as the swimming medium.

To evaluate the propulsion performance under conditions dominated by hydrodynamic forces rather than gravitational effects, the swimming velocity of the MMMR in the liquid xy-plane is analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5A, the experimental results reveal a highly linear relationship between the propulsion velocity of the MMMR and the magnetic field rotation frequency f. The linear trend observed in the experiments aligns closely with the simulation results and is further illustrated in Movie S1. However, a key difference between the experimental results and the simulation lies in the constraints imposed by the magnetic torque. In simulations, it is assumed that the applied rotational frequency can increase indefinitely without mechanical limitations. In practice, the rotational frequency of the MMMR is limited by the maximum magnetic torque the system can generate. According to Eq. (2), the step-out frequency is theoretically proportional to the strength of the applied magnetic field. This relationship is experimentally validated, as the results show that increasing the magnetic field strength extends the frequency range within which the MMMR maintains synchronous rotation.

A Helical swimming velocity of MMMR under different magnetic field strengths. B Schematic of closed-loop automatic control during helical swimming. C Trajectory captured by the side camera and pitch adjustment to maintain the desired helical swimming height when liquid-in swimming. D Trajectory captured by the top camera and yaw adjustment to maintain the desired helical swimming direction (x-axis) when near-surface swimming.

Since the MMMR rotates synchronously with the magnetic field, the helical swimming direction can be adjusted by changing the rotation axis of the magnetic field. As shown in Fig. 5B, the rotation axis of the magnetic field is described by the pitch and yaw angles. During liquid-in swimming, the MMMR continuously sinks in the z-direction due to gravity. To ensure stable swimming in the open liquid region, a closed-loop automatic control system based on Proportional-integral-derivative (PID) is introduced. In this strategy, the control variable is the pitch angle of the magnetic field, which utilizes a portion of the propulsion force to counteract the gravitational effect. Using gains Kp = 2 × 10−3, Ki = 5 × 10−4, and Kd = 2 × 10−3, the response settles within ± 5% in approximately 10s, with a peak overshoot of about 20% (see Fig. 5C and Movie S2). Tuning is performed in a simple manner: Kp is increased first for a fast approach to the setpoint, followed by a small Ki to remove steady-state error and a Kd term to damp oscillations. With PID control, the pitch converges and remains stable, enabling maintenance of a constant height; without PID, sinking to the bottom occurs.

During helical swimming in liquid, the direction is adjusted by controlling the yaw angle of the magnetic field. In shallow liquids, boundary effects cause the swimming direction to deviate from the commanded yaw. To address this, the same closed-loop strategy is applied to regulate the yaw angle during near-surface swimming using Kp = 2 × 10−3, Ki = 5 × 10−4, and Kd = 2 × 10−3. As shown in Fig. 5D, even when the MMMR comes into contact with the liquid surface, the PID controller adjusts the yaw angle, enabling the MMMR to recover its intended helical swimming direction along the x-axis. The response settles in roughly 7.5s with about 5% overshoot. In contrast, without PID control, the MMMR is significantly affected by boundary effects, leading to severe deviations from its intended trajectory. Similarly, Fig. S5 demonstrates that the system allows the yaw angle to converge, enabling the MMMR to restore its helical swimming along the y-axis. The near-surface helical swimming of the MMMR under closed-loop automation is further demonstrated in Movie S3.

Bipedal walking evaluation

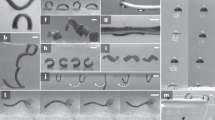

In a liquid-free environment, as shown in Fig. 1D and 6A, the MMMR achieves effective locomotion by alternately supporting itself on one foot while rotating the other under a fixed pitch oscillating magnetic field. Fig. 6B illustrates the relationship between the walking velocity of the MMMR and the oscillation frequency at a pitch angle of 20∘ under various oscillation angles. The results reveal that walking velocity increases with larger oscillation angles at the same frequency, as greater oscillation angles enable the MMMR to take longer strides. Fig. 6C presents the variation in walking velocity with frequency at a fixed oscillation angle of 60∘ and three different pitch angles. The experimental findings show that, at the same frequency, walking velocity increases as the pitch angle rises from 10∘ to 20∘, but decreases when the pitch angle is further increased to 30∘. According to Eq. (4), a pitch angle that is too small results in insufficient differences in the supporting forces between the two legs, hindering the alternating motion required for walking. Conversely, an excessively large pitch angle causes the MMMR to tilt backward, reducing its stride length for the same oscillation angle. These results suggest that a pitch angle of 20∘ is optimal for achieving efficient locomotion. Furthermore, the walking velocity in a liquid-free environment is generally proportional to the oscillation frequency, as demonstrated in Movie S4.

A Liquid-free bipedal walking posture captured by side camera under a variable pitch oscillating magnetic field. B Effect of oscillation angles on walking velocity at a 20∘ pitch angle. C Effect of pitch angles on walking velocity at a 90∘ oscillation angle. D Comparison of walking velocity between fixed-pitch (Bow angle of 0∘) and variable-pitch oscillating magnetic fields (Bow angle of 40∘).

When walking in liquid, the behavior of the MMMR differs significantly from that in a liquid-free environment. Due to the combined effects of fluid friction and buoyancy, the MMMR is unable to smoothly alternate its legs as supporting limbs. Specifically, when the magnetic field alternates direction, the rotating leg fails to descend in time to become a supporting leg, causing the MMMR to rotate in place. This results in a very low walking velocity, as demonstrated in Supplementary Movie S5. As shown in Fig. 7B, increasing the oscillation frequency does not improve the walking velocity. On the contrary, as the oscillation angle of the magnetic field increases, the lifted leg rises higher with each step, making it even harder to descend and further reducing walking velocity. Similarly, as illustrated in Fig. 7C, increasing the magnetic field’s pitch angle causes the lifted leg to rise even higher, further hindering its ability to return to the ground and reducing walking velocity. Consequently, the walking velocity in a liquid environment is much lower than that in a liquid-free environment.

A Liquid-in bipedal walking posture captured by a side camera under a variable pitch oscillating magnetic field. B Effect of oscillation angles on walking velocity at a 20∘ pitch angle. C Effect of pitch angles on walking velocity at a 90∘ oscillation angle. D Comparison of walking velocity between fixed-pitch (Bow angle of 0∘) and variable-pitch (Bow angle of 40∘) oscillating magnetic fields.

To address this issue, a variable-pitch oscillating magnetic field is proposed. In previous walking evaluation experiments, the pitch angle of the magnetic field is kept constant. As shown in Fig. 1C and 7A, the variable-pitch oscillating magnetic field enables the MMMR to tilt its body forward while stepping, forcing its foot to quickly return to the surface. Before the next step, the pitch angle reverts to a backward tilt, allowing the MMMR to smoothly alternate its supporting foot. The range of pitch angle variation is defined as the bow angle. As shown in Fig. 7D, compared to a fixed pitch angle of 20∘ (bow = 0∘), the MMMR achieves nearly a fourfold increase in walking velocity at the bottom of a liquid when the bow angle is 40∘ (i.e., the pitch angle varies from −20∘ to 20∘). Movie S5 visually demonstrates the comparison between these two conditions. However, in a liquid-free environment, where buoyancy and fluid resistance are absent, the alternation of the two legs is extremely smooth. Applying a variable-pitch oscillating magnetic field in such an environment leads to excessive foot contact with the surface, which hinders walking, as shown in Fig. 6D. Therefore, in a liquid-free environment, the MMMR achieves better performance with a fixed-pitch oscillating magnetic field. In contrast, within a liquid environment, the MMMR achieves optimal walking performance with a variable-pitch oscillating magnetic field.

Multimodal locomotion demonstration

The helical swimming and bipedal walking of the MMMR demonstrate strong directional controllability. As shown in Fig. 8A, the MMMR performs liquid-in swimming, following an S-shaped path guided by the yaw angle of the rotating magnetic field. Similarly, as illustrated in Fig. 8B, the MMMR performs liquid-free walking, also following an S-shaped path under the control of the yaw angle of the oscillating magnetic field. Movie S6 presents the corresponding videos, providing an intuitive demonstration of the directional controllability of MMMR.

The walking mode of the MMMR is also capable of adapting to environments with certain slopes. As shown in Fig. 8C, D, and Movie S7, the MMMR is capable of walking on slopes with a maximum steepness of up to 30∘, regardless of whether it is in liquid-free or liquid-in walking modes. However, as the slope angle increases beyond 30∘, the pitch angle of the MMMR becomes excessively close to the slope surface. This results in a loss of stability, as the MMMR body struggles to maintain its upright orientation, eventually causing it to overturn.

The impact of loading on the multimodal locomotion of the MMMR is also investigated. Propulsion in helical swimming is torque-driven and determined by geometry, so speed scales with rotational rate and is largely independent of internal fill at low Reynolds number. In bipedal walking under an oscillating field, a payload mainly increases the net volumetric force but does not change magnetic torque, foot spacing, or field programming; the differential torque term still unloads one foot to enable stepping, and our variable-pitch strategy secures timely foot landing in liquid. To further verify the minimal effect of loading to the multiple motion of MMMR, a comparative analysis is performed between two MMMRs: one with its internal space loaded with silica gel and the other without any loading. As shown in Fig. S6 and Movie S8, under identical conditions, their locomotion velocities in liquid-in swimming, liquid-free walking, and liquid-in walking remain nearly identical. The ability to maintain stable performance regardless of loading further confirms its potential for targeted drug delivery in complex environments.

The bladder is a vital organ in the human urinary system that functions as a reservoir for urine, temporarily storing it before excretion through the urethra. The multimodal swimming and walking capabilities of the MMMR enable it to navigate controllably within the bladder. As illustrated in Fig. 8E, a real-size semi-sectioned model of a male bladder demonstrates this process. The MMMR is designed to enter through the urethra, swim to the bottom of the bladder, and then walk to the target location. Afterward, the MMMR switches back to swimming mode to return to the urethra. Fig. 8E and Movie S9 validate the multimodal functionality of the MMMR within an artificial bladder. The MMMR demonstrates seamless transitions between motion modes and successfully completes the processes of targeted navigation and retrieval.

Discussion

This work proposes a novel Multimodal Magnetic Miniature Robot (MMMR) for adaptive navigation in amphibious environments, offering advantages such as high locomotion efficiency, low magnetic field intensity requirements, and precise directional controllability. Specifically, the MMMR demonstrates exceptional propulsion efficiency in its helical swimming mode14, while its bipedal walking mode achieves superior locomotion speeds compared to most other walking mechanisms43. Moreover, the torque-driven locomotion mechanism enables the MMMR to operate with a relatively low magnetic field strength, with approximately 8 mT being sufficient to achieve controllable speeds across all motion modes. Furthermore, the MMMR exhibits excellent kinematic stability and precise controllability, with its structural parameters determining directional performance and velocity, regardless of some external factors such as liquid viscosity or loading. The walking mode of the MMMR can operate stably on slopes with inclinations up to 30∘. However, on steeper inclines its walking performance becomes limited.

The structural parameters of the helical body of the MMMR are determined through simulations. A simulation method employing a frozen rotor and frozen translating object is utilized to simplify the simulation process, achieving a computational efficiency improvement of several orders of magnitude compared to dynamic transient simulations. The simulation method is first validated using a typical spring-like helix with theoretical formulas, followed by convergence analysis before being applied to the MMMR. The simulations determined optimal parameters, including helical thickness, turn numbers, and elliptical tip length. Furthermore, it is verified that the effects of liquid viscosity and the bipedal structure on helical swimming are negligible.

The helical swimming and bipedal walking of the MMMR are experimentally evaluated. Helical swimming is actuated by a rotating magnetic field, with the swimming speed proportional to the rotation frequency. A closed-loop automated control strategy is integrated into the helical swimming mode. By adjusting the pitch angle, gravity is compensated to maintain a constant swimming height, while adjustments to the yaw angle compensate for the boundary effects caused by friction near surfaces, enhancing the adaptability of the MMMR to various swimming environments. Bipedal walking is actuated by an oscillating magnetic field. By adjusting the pitch angle, a difference in supporting forces between the two feet is created, enabling the alternation of a supporting foot and a rotating foot, thus achieving bipedal walking. For liquid-free walking, the walking speed is proportional to the oscillation frequency, and increasing the oscillation angle improves walking velocity. However, the pitch angle must strike a balance between the supporting force difference of the feet and the foot-lifting height. A pitch angle of 20∘ is determined to provide an optimal walking mode. For liquid-in walking, the combined effects of fluid resistance and buoyancy prevent the feet from promptly landing after lifting, making it difficult to alternate the supporting foot. To address this, a variable-pitch mode of the oscillating magnetic field is proposed, allowing the MMMR to tilt its body forward during walking, forcing the feet to land. This approach enabled effective bipedal walking even under liquid conditions. The directional controllability of the MMMR is validated by guiding it to walk along an S-shaped curve. The walking mode of the MMMR also adapts to inclined environments, successfully walking on slopes with a maximum steepness of up to 30∘ in both liquid-free and liquid-in conditions. Additionally, a comparison between loaded and unloaded MMMRs shows that their locomotion velocities in liquid-in swimming, liquid-free walking, and liquid-in walking remain nearly identical, demonstrating excellent multimodal locomotion stability. Multimodal validation is conducted within an artificial bladder. The MMMR successfully completed the process of swimming into the bladder through the urethra, walking to a target location, and swimming back to the entry point for retrieval.

In the future, the strong directional controllability and versatile multimodal capabilities of the MMMR could be harnessed for a wide range of biomedical applications. One promising application involves leveraging the cylindrical body of the MMMR as a carrier for therapeutic agents, such as s or nanoparticles. By integrating advanced technologies like ultrasound-triggered release or photothermal therapy, the MMMR could enable precise and site-specific drug delivery. Furthermore, the MMMR is expected to operate in a wider range of organs, such as the brain and stomach, where bodily fluids and delicate surface tissues are present, and local terrain can include slopes. To better meet these in vivo demands, we will improve climbing on slopes by increasing friction between the feet and the substrate using high-friction elastomers or gecko-inspired fibrillar pads, and by optimizing the sole design to enlarge the real contact area and resist downhill slip. In parallel, we will enhance intelligent navigation through advances in artificial intelligence and sensor integration, enabling the MMMR to perceive, plan, and traverse complex anatomical environments more safely and reliably. By equipping the MMMR with real-time environmental sensing and decision-making algorithms, it could autonomously select the most appropriate locomotion mode and path based on factors such as fluid viscosity, tissue stiffness, and target localization.

Methods

Simulation setting

The numerical simulations are performed using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.2. As illustrated in Fig. S1A, the computational model consists of three distinct domains: (i) the external fluid domain, (ii) the fluid envelope surrounding the helix, and (iii) the solid domain representing the helix itself. These domains are defined to accurately capture the interactions between the solid structure and the surrounding fluid during locomotion. The fluid domains are modeled under the creeping flow regime, which assumes low Reynolds numbers and neglects inertial effects. The helix boundary is assigned a no-slip condition, ensuring that the fluid velocity at the helix surface matches the velocity of the solid boundary, a critical assumption for realistic modeling.

For the frozen rotor model, the fluid envelope surrounding the helix is defined as a rotating domain with its rotation axis aligned with the helix axis. The rotational frequency f could be specified as a parameter, and a steady-state study with the frozen rotor is employed to calculate. In this model, the rotation of the fluid envelope relative to the helix simulates the effect of helical swimming in fluids. For the frozen translating object model, the helix boundary is prescribed as a moving wall with a user-defined translational velocity v. This configuration enabled the simulation of translational motion of the helix through the fluid. A standard steady-state study is used to compute the flow field under this condition. In the result node, the axial fluid force and torque can be calculated using the following equations:

where σ represents the fluid traction stress tensor computed by the simulation, S denotes the surface of the helix, and dA is the differential surface element on S.

Materials and fabrication

The MMMR is fabricated using DLP-based photopolymerization 3D printing technology with an ELEGOO Mars 4 DLP printer. The material used is 8K rigid photopolymer resin, also from ELEGOO. To achieve magnetic actuation, the MMMR is embedded with N52-grade neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, known for their high energy density and strong magnetic properties. The artificial bladder model is manufactured using the same equipment, utilizing transparent photopolymer resin provided by Da Jian. The use of transparent resin facilitated visual observation and locomotion analysis of MMMR within the confined environment.

Hardware setting of magnetic magnetic-actuated system

The magnetic actuation system is based on a 3-axis Helmholtz coil configuration, designed to generate uniform magnetic fields for precise control of the MMMR. The x-axis coils have a radius and spacing of 172mm, the y-axis coils 130mm, and the z-axis coils 80mm. A current of 15.67 A generates a magnetic field of approximately 10mT in the x-axis coils, 12.94 A generates 10mT in the y-axis coils, and 8.14 A generates 10mT in the z-axis coils. The system provides a workspace of approximately 40 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm within the coils. The current drivers for the x-axis and y-axis coils are servo drivers (Advanced Motion Controls, model A50A100). For the z-axis coil, the system utilizes the A25A100 model, which is specifically chosen for its compatibility with the lower current requirements of the smaller z-axis coil. The current signals driving the coil system are generated by a signal acquisition card (Advantech, model PCI-1720U). This card enables precise and synchronized current control for all three axes. For visual monitoring and feedback, the system incorporates an industrial camera (Daheng Imaging, model ME2L-161-61U3C-L), which provides high-resolution real-time imaging. The camera is paired with a telecentric lens (Daheng Optics, model GCO-232106), which eliminates perspective distortions and ensures consistent measurement accuracy across the entire workspace.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Fischer, F., Gletter, C., Jeong, M. & Qiu, T. Magneto-oscillatory localization for small-scale robots. npj Robot. 2, 1 (2024).

Yang, L. & Zhang, L. Motion control in magnetic microrobotics: From individual and multiple robots to swarms. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 4, 509–534 (2021).

Sun, M., Yang, S., Jiang, J., Wang, Q. & Zhang, L. Multiple magneto-optical microrobotic collectives with selective control in three dimensions under water. Small 20, 2310769 (2024).

Qin, J., Wu, X., Krueger, A. & Hecht, B. Light-driven plasmonic microrobot for nanoparticle manipulation. Nat. Commun. 16, 2570 (2025).

Máthé, M. T., Nishikawa, H., Araoka, F., Jákli, A. & Salamon, P. Electrically activated ferroelectric nematic microrobots. Nat. Commun. 15, 6928 (2024).

Katzmeier, F. & Simmel, F. C. Microrobots powered by concentration polarization electrophoresis (CPEP). Nat. Commun. 14, 6247 (2023).

Deng, Y., Paskert, A., Zhang, Z., Wittkowski, R. & Ahmed, D. An acoustically controlled helical microrobot. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh5260 (2023).

Aghakhani, A. et al. High shear rate propulsion of acoustic microrobots in complex biological fluids. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm5126 (2022).

Yang, Z. & Zhang, L. Magnetic actuation systems for miniature robots: A review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2, 2000082 (2020).

Zhou, H., Mayorga-Martinez, C. C., Pané, S., Zhang, L. & Pumera, M. Magnetically driven micro and nanorobots. Chem. Rev. 121, 4999–5041 (2021).

Chowdhury, A. M. B. et al. Dual active tilted roller actuation system (DATRAS) with an electromagnetic actuation system for vascular intervention. npj Robot. 3, 8 (2025).

Purcell, E. M. Life at low Reynolds number. Am. J. Phys. 45, 3–11 (1977).

Berg, H. C. & Anderson, R. A. Bacteria swim by rotating their flagellar filaments. Nature 245, 380–382 (1973).

Abbott, J. J. et al. How should microrobots swim? Int. J. Robot. Res. 28, 1434–1447 (2009).

Zhao, F., Rong, W., Wang, L. & Sun, L. Automatic control of magnetic helical microrobots for on-plane docking. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 22, 2395–2404 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. 3-d autonomous manipulation system of helical microswimmers with online compensation update. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 18, 1380–1391 (2020).

Zhong, S. et al. Spatial constraint-based navigation and emergency replanning adaptive control for magnetic helical microrobots in dynamic environments. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 21, 7180–7189 (2023).

Cai, M. et al. Deep reinforcement learning framework-based flow rate rejection control of soft magnetic miniature robots. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 53, 7699–7711 (2022).

Behrens, M. R. & Ruder, W. C. Smart magnetic microrobots learn to swim with deep reinforcement learning. Adv. Intell. Syst. 4, 2200023 (2022).

Amoudruz, L. & Koumoutsakos, P. Independent control and path planning of microswimmers with a uniform magnetic field. Adv. Intell. Syst. 4, 2100183 (2022).

Li, Y., Huo, Y., Chu, X. & Yang, L. Automated magnetic microrobot control: From mathematical modeling to machine learning. Mathematics 12, 2180 (2024).

Zhu, A. et al. A magnetic helical miniature robot with soft magnetic-controlled gripper. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 9, 3163–3170 (2024).

Tan, L. & Cappelleri, D. J. Design, fabrication, and characterization of a helical adaptive multi-material microrobot (hammr). IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 8, 1723–1730 (2023).

Jia, Y., Zhu, Z., Jing, X., Lin, J. & Lu, M. Fabrication and performance evaluation of magnetically driven double curved conical ribbon micro-helical robot. Mater. Des. 226, 111651 (2023).

Ye, Y. et al. Advanced manufacturing techniques and applications of micro-/nanoscale helices. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 7, 052004 (2025).

Lee, H. & Park, S. Magnetically actuated helical microrobot with magnetic nanoparticle retrieval and sequential dual-drug release abilities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 27471–27485 (2023).

Lee, H., Kim, D.-i, Kwon, S.-h & Park, S. Magnetically actuated drug delivery helical microrobot with magnetic nanoparticle retrieval ability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 19633–19647 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Helical hydrogel micromotors for delivery of neural stem cells and restoration of neural connectivity. Chem. Eng. J. 479, 147745 (2024).

Su, L. et al. Modularized microrobot with lock-and-detachable modules for targeted cell delivery in bile duct. Sci. Adv. 9, eadj0883 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Magnetic soft microfiberbots for robotic embolization. Sci. Robot. 9, eadh2479 (2024).

Peng, Q. et al. Thermal and magnetic dual-responsive catheter-assisted shape memory microrobots for multistage vascular embolization. Research 7, 0339 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Shape memory alloy helical microrobots with transformable capability towards vascular occlusion treatment. Research 2022, 9754876 (2022).

Nguyen, K. T. et al. Guide-wired helical microrobot for percutaneous revascularization in chronic total occlusion in-vivo validation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68, 2490–2498 (2020).

Hu, W., Lum, G. Z., Mastrangeli, M. & Sitti, M. Small-scale soft-bodied robot with multimodal locomotion. Nature 554, 81–85 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Magnetically switchable adhesive millirobots for universal manipulation in both air and water. Adv. Mater. 37, 2420045 (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. A magnetic-driven multi-motion robot with position/orientation sensing capability. Research 6, 0177 (2023).

Wu, Y., Dong, X., Kim, J.-k, Wang, C. & Sitti, M. Wireless soft millirobots for climbing three-dimensional surfaces in confined spaces. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn3431 (2022).

Xin, Z. et al. Dynamic control of multimodal motion for bistable soft millirobots in complex environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 41, 2662–2676 (2025).

Wang, B. et al. Magnetically driven biohybrid blood hydrogel fibres for personalized intracranial tumour therapy under fluoroscopic tracking. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 9, 1471–1485 (2025).

Yang, L., Sun, M., Zhang, M. & Zhang, L. Multimodal motion control of soft ferrofluid robot with environment and task adaptability. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 28, 3099–3109 (2023).

Ren, Z. & Sitti, M. Design and build of small-scale magnetic soft-bodied robots with multimodal locomotion. Nat. Protoc. 19, 441–486 (2024).

Huang, C., Lai, Z., Wu, X. & Xu, T. Multimodal locomotion and cargo transportation of magnetically actuated quadruped soft microrobots. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2022, 0004 (2022).

Zhao, J. et al. Insect-scale biped robots based on asymmetrical friction effect induced by magnetic torque. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312655 (2024).

He, Y., Dong, S., Wang, L., Rong, W. & Sun, L. Bipedal microwalkers actuated by oscillating magnetic fields. Soft Matter 16, 7927–7934 (2020).

Huang, C., Xu, T., Yu, H. & Wu, X. A novel h-shaped soft magnetic microrobot for automatic manipulation in dynamic environments. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 22, 6168–6178 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Surface-chemistry-mediated control of individual magnetic helical microswimmers in a swarm. ACS Nano 12, 6210–6217 (2018).

Wang, X., Hu, C., Pané, S. & Nelson, B. J. Dynamic modeling of magnetic helical microrobots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 7, 1682–1688 (2021).

Gray, J. & Hancock, G. J. The propulsion of sea-urchin spermatozoa. J. Exp. Biol. 32, 802–814 (1955).

Cox, R. G. The motion of long slender bodies in a viscous fluid Part 1. General theory. J. Fluid Mech. 44, 791–810 (1970).

Lighthill, J. Flagellar hydrodynamics. SIAM Rev. 18, 161–230 (1976).

Hu, N. et al. Comprehensive modeling of corkscrew motion in micro-/nano-robots with general helical structures. Nat. Commun. 15, 7399 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to the financial support from the Research Institute for Advanced Manufacturing of Hong Kong Polytechnic University (grant no. 1-CDK3); the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant no. 2025A1515010116), and the Hong Kong Research Grant Council (grant no. 25200424). Aoji Zhu would like to extend his sincere gratitude for the financial support from the Research Committee of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University under student account code RN5Y. Jinsheng Zhao would like to extend his sincere gratitude for the financial support from the project (PolyU Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship 20 Scheme 2024) (grant no. YWEC). The authors also would like to thank Wenxin Shi for her figure scheme suggestions and Shangzhen Yu, 3D Technical Artist at Lumenverse (Beijing Shanhailiuming Technology Co., Ltd), ORCID (0009-0001-9654-0145), for providing the 3D bladder model.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Z. conceived the idea, worked out the details and wrote the manuscript. A.Z., J.Z. and L.Y. discussed the simulation and experimental methods. L.Y. supervised the project and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, A., Zhao, J. & Yang, L. Multimodal magnetic miniature robot for adaptive navigation in amphibious environments. npj Robot 3, 42 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00062-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00062-z