Abstract

The octopus has evolved a stereotyped bending propagation mechanism to maneuver its highly flexible arms underwater, using suckers for sensing and capturing prey. Inspired by this biological strategy, we propose an activation propagation-based model that generates motion through phase differences in the activation of dorsal and ventral muscles. This model requires only three input parameters to achieve reaching behavior, without the need for full-shape control. We applied this model to a six-segment soft continuum robot and conducted experiments that confirmed the low-resistance characteristics of underwater bending propagation locomotion. To enable autonomous interaction, we integrated suckers with attachment-sensing capabilities and developed an “approach-sense-grasp” strategy, allowing the robot to retrieve floating objects both in open water and within confined environments. Our findings shed light on the control principles behind octopus arm locomotion and demonstrate their applicability in simplifying control of soft robotic systems for efficient, adaptive grasping in underwater environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

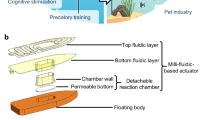

After long-term evolution, soft-bodied underwater creatures like octopuses have developed flexible tentacles that allow them to perform agile underwater locomotion1,2. At the same time, the suckers on their tentacles are equipped of a rich neural network capable of sensing contact information from external objects3. Numerous studies have found that octopuses use an “approach-sense-grasp” strategy when capturing prey4,5,6. This involves approaching the target using bending propagation which they create a bend at the base, and propagate along the tentacle toward the tip7,8. Once the suckers detect contact with the target, they immediately execute the grasping action. This strategy has several advantages: the octopus’s tentacle achieves bending propagation by sequentially activating muscles, simplifying the control of the tentacle9. Additionally, this locomotion reduces underwater resistance, allowing the octopus to quickly approach the target10. Meanwhile, due to the sensory capabilities of the suckers, the octopus typically employs a feedforward control during grasping11. At any point during the bending propagation when contact is made with the target, the locomotion is interrupted to execute the grasp, thus simplifying the grasping control strategy12.

In recent years, the rapid development of soft robotics realm13,14 has inspired researchers to develop a large number of biomimetic octopus tentacles, which are capable of functionalities such as bending15, elongation16, and twisting17, enabling tasks like crawling18,19, swimming20,21,22 and grasping23,24,25. Just like octopus tentacles, soft robots have infinite degrees of freedom, and their control is a bottleneck that limits their development26,27. Therefore, octopus control strategies could provide valuable insights for controlling soft robots. Currently, research on the bending propagation of octopus tentacles is still at the stage of biological studies10,28,29, where models are simulated to replicate the movements of biological octopuses30. Considering the complexity of underwater environment fluid modeling, using biomimetic robotic platforms can advance our understanding of biological behaviors31,32 and simultaneously validate the principles of biological locomotion33,34, contributing to the development of new robot functions35,36.

In this paper, we propose a robotic bending propagation model based on sequential activation. This model generates bending propagation motion without the need for solving the robot’s overall configuration. Through this model, we reveal that bending propagation motion can be generated by phase differences in the activation of the dorsal and ventral muscles. We then validate this sequential activation strategy on a biomimetic robotic platform, demonstrating that it results in a smaller area of underwater motion range, thereby reducing drag. Finally, we integrate attachment sensing functionality to achieve the “approach-sense-grasp” strategy for grasping and collecting floating targets. The biomimetic robotic system we built is also capable of grasping targets in confined spaces without the need to fix the robot’s base. Through this research, we explore octopus-inspired grasping strategies and achieve underwater grasping with minimal sensing and control requirements, showcasing the potential for autonomous underwater object grasping and manipulation.

Results

Octopus-inspired soft continuum robotic platform

To explore octopus‑inspired underwater locomotion and its application to underwater object grasping, we designed and developed an octopus‑inspired soft continuum robotic platform (Fig. 2A). The robot comprises six serially connected soft bending segments, each incorporating three parallel pneumatic muscle actuators. In each segment, one actuator is mounted ventrally and two dorsally, and suction cups are evenly distributed along the arm’s length, enabling both bending and suction capabilities at each segment. The robot measures 1100 mm in total length, with a proximal diameter of 77 mm and a distal diameter of 24 mm, forming a conical profile with a 1.5° taper angle. Actuation of the robot is provided by a multi‑channel pneumatic actuation system capable of regulating the internal pressures of the pneumatic chambers24. Detailed design and kinematic modeling of the robot are presented in the Materials and Methods section.

Bending propagation model for octopus-inspired soft continuum robot

We observed that octopuses typically exhibit stereotyped predatory behaviors, characterized by generating a bend near the base of the arm and propagating it toward the tip (Fig. 1A). Bending of the octopus arm is primarily driven by the activation of the dorsal or ventral longitudinal muscles9. When the dorsal muscles contract and shorten while the ventral muscles remain passive, the arm bends ventrally due to the asymmetrical strain distribution. During bending propagation, the key mechanism is a temporal delay in the activation of ventral muscles relative to the dorsal ones within a given bending segment. By sequentially activating the dorsal and ventral muscle groups in a proximal-to-distal direction, and maintaining a phase lag between them, a propagating bending wave can be generated along the arm. Although direct quantitative measurements of such phase-based activation in octopuses are limited37, our model adopts this mechanism as a biologically inspired simplification based on qualitative behavioral observations.

A Bending propagation motion of the octopus captured by a high-speed camera. B Parameter definition of the octopus-inspired bending propagation model. C Time-varying curve of the ventral actuator length in the bending wave propagation model. D Time-varying curve of the dorsal actuator length. E, Simulation results of the bending propagation model, with numbers representing the segment number. Actuators that are not driven in the simulation are shown in blue, and fully actuated actuators are displayed in red. F Variation of curvature along the arm over bending propagation time. G Variation of arm total length with parameter A. H Variation of end-effector pitch angle with parameter Δt. I Variation of bending propagation time with parameter ε. J Variation of maximum curvature along the arm with parameter A, curves in different colors represent different values of Δt. K Variation of maximum amplitude A without self-contact under different value of Δt, the pink area represents the rational amplitude range.

Under this assumption, we propose a bending propagation model based on sequential actuation of robotic actuators. Unlike biological organisms, biomimetic robots are typically composed of multiple discrete bending joints. Therefore, we developed a multi-segment discrete bending propagation model for bio-inspired robotic platform, as follows:

This model defines the relationship between the lengths of the dorsal and ventral actuators of the robot over time (Fig. 1B). Using only three parameters, it generates the actuator length sequence required for bending propagation without solving the full configuration of the robot.

Specifically, the length of the dorsal actuator in the i-th segment is denoted as \({l}_{{dorsal}}^{i}\), the length of the ventral actuator in the i-th segment as \({l}_{{ventral}}^{i}\), the magnitude of length change of the actuator in the i-th segment as Ai, which is bounded by the physical limits of the soft robotic segments (typically 1.0 ~ 1.8 times the initial segment length in our platform). The actuator length change speed factor as ε, and is tuned to match the timescale of generated motion. The phase shift Δt introduces a temporal delay between the activation of dorsal and ventral actuators, serving as the key mechanism for generating asymmetric deformation and propagating bending. This value is chosen based on the number of segments involved in the bending region of thr robot.

As illustrated in Eqs. (1) and (2), dorsal actuators in segments 1 through 6 are activated sequentially, with a constant inter-segment delay of, and elongate by the amplitude Ai. Within each segment, the ventral actuator is activated Δt earlier than the dorsal one (Fig. 2C, D), establishing a local temporal asymmetry that leads to bending toward the ventral side.

With the kinematic model of the soft continuum robot (as described in the MM section), we conducted simulation experiments in the MATLAB (MathWorks, USA). It is worth noting that in the kinematic model, the actuator numbered 1 is defined as the ventral actuator, while actuators 2 and 3 have the same length and are both defined as dorsal actuators, that is,

To maintain a smooth transfer of curvature at the bending points along the arm, we define the relationship of the driving magnitude to ensure that the maximum bending curvature of each bending joint is consistent, as follows:

Similarly, i represents the i-th segment, and Ai represents the actuation magnitude of the i-th segment. The snapshot of the simulation results is shown in Fig. 1E. The inactive actuators are shown in blue, while activated actuators are shown in red. The color intensity indicates the amplitude of activation. As the results shows, with the propagation of the activation signal, the bending curve is transmitted from the base (the first segment) to the tip (the sixth segment). The results indicate that during the bending propagation motion, the activation signals of the robot’s dorsal and ventral actuators change consistently, with only an overall phase difference. Therefore, the bending propagation motion could be generated by the activation phase difference between the dorsal and ventral muscles.

We recorded the variation of curvature along the arm during bending propagation, and the results demonstrate that the model can successfully reproduce the characteristic propagation of the maximum curvature point observed in biological octopus arms (Fig. 1F). The total length of the robot increases linearly with the actuation amplitude A (Fig. 1G), indicating that the maximum bending propagation distance can be tuned by adjusting this parameter. The pitch angle at the robot’s end-effector increases with the phase difference \(\triangle {\rm{t}}\) (Fig. 1H). In addition, the propagation time decreases linearly with increasing \({\rm{\varepsilon }}\) (Fig. 1I), demonstrating that the bending propagating speed can be effectively modulated by tuning the strain rate \({\rm{\varepsilon }}\).

The value of the parameter in the model is mainly determined by the term \(1/1+{{\rm{e}}}^{-{\rm{x}}}\) in Eq. (1). The moment when the last segment actuator finishes activation at t = T is defined as the end of bending propagation, at which point the exponential term satisfy the constraint \(-{\rm{N}}/{\rm{N}}\cdot {\rm{\varepsilon }}+{\rm{T}}\ge 5\). Moreover, if the ventral-side actuator of the last segment has already completed activation when the dorsal-side actuator of the first segment begins (\(-{\rm{\varepsilon }}/{\rm{N}}+\mathrm{\varDelta t}\le -{\rm{\varepsilon }}+{\rm{T}}\)), further increasing the phase shift \(\Delta {\text{t}}\) will no longer affect the arm’s configuration (Fig. 1J). To prevent self-contact of the arm, the appropriate range of actuation amplitude A is shown in Fig. 1K.

Hydrodynamic drag analysis of the octopus-inspired soft continuum robot

We characterize the underwater drag of the robot by calculating the hydrodynamic force acting on the center of each bending unit. As shown in Fig. 2B, each bending unit is simplified as a truncated cone, with a top diameter of dij, a base diameter of dij-1, and a length of lunit. As the robot moves underwater, each bending unit travels at a certain velocity v, which can be decomposed into two components: vper, perpendicular to the segment’s longitudinal axis, and vtan, tangential to the axis. Similarly, the hydrodynamic drag FD acting on the bending unit can be decomposed into a perpendicular component Fper and a tangential component Ftan. The drag force on each unit can be expressed as follows:

where Sper=(dij+ dij-1)luint/4 is the projected area of the segment in the plane perpendicular to the direction of vper and Stan = (dij+ dij-1)luint/2 is the surface area of the segment. The coefficients cper and ctan express the perpendicular and tangential drag coefficients, respectively.

To determine these coefficients, we performed experimental calibration using the setup shown in Fig. 2C. A single robot segment was mounted on a towing rail equipped with a force sensor, and fully submerged in a water tank. By varying the towing speed in directions perpendicular and parallel to the segment axis, we recorded the corresponding drag forces (Fig. 2D). Using these data and Eq. (4), we fitted the drag coefficients as:

The results show that cper is 30.8 times larger than ctan, highlighting the significantly higher resistance encountered during lateral motion compared to tangential motion. This result supports the hypothesis that propagating bending, which primarily involves tangential segment movement, leads to reduced hydrodynamic resistance—thereby improving underwater efficiency and control simplicity.

Underwater drag analysis of robotic bending propagation

Building upon the hydrodynamic drag model of the octopus-inspired soft robot, we incorporated segment-wise drag forces into the bending propagation simulation. The robot was discretized into 300 units along its length. Owing to the actuation amplitude limitation of the robot, the parameter A was set to a maximum value of 2.8l0. To minimize the frontal length, a maximum of two joint segments were allowed to bend simultaneously in the experiments; consequently, \({\rm{\varepsilon }}\) and \(\triangle {\rm{t}}\) were assigned values of -48 and 8, respectively.

A simulation was first conducted to evaluate the spatial distribution of hydrodynamic drag during bending propagation. As shown in Fig. 3A, significant drag forces were concentrated in regions undergoing active bending, where velocity components were perpendicular to the segment’s longitudinal axis. In contrast, the rest of the arm experienced minimal resistance.

To enable a quantitative comparison, a non-bending control actuation pattern was designed. This pattern ensured that the robot’s initial and final positions and velocities matched those of the bending-propagation case. In this control condition, all dorsal actuators across segments were activated simultaneously and uniformly, without sequential phase differences:

The resulting motion, shown in Fig. 3B, resembled a sweeping deformation with drag forces more evenly distributed along the body. Due to the absence of concentrated bending, the peak drag magnitude was lower, but more spatially diffuse.

Figure 3C summarizes the time-evolving drag distributions in both motion modes. For the bending propagation mode, drag appeared primarily in the bending region and shifted from base to tip over time. In the non-bending mode, drag was more uniformly spread throughout the body. Despite identical initial and final force states, the bending propagation mode achieved a 1.94 times higher locomotion speed under the same amount of drag-induced work (W = 7.26 J).

To further validate these findings, physical experiments were conducted on the soft robotic platform. Thirty reflective markers were evenly distributed along the robot’s surface, and their positions during motion were recorded using a top-view camera (Fig. 4A, B). The captured trajectories were interpolated to estimate segment-wise velocities and displacements, which were then used to compute drag forces via Eq. (4) (Fig. 4C, D).

A Experimental snapshot of underwater robotic bending propagation motion. B Experimental snapshot of underwater robotic none-bending propagation motion, black arrows indicate the underwater drag force. C Hydrodynamic drag analysis of robotic bending propagation based on motion track results., black arrows indicate the underwater drag force. D Hydrodynamic drag analysis of robotic none-bending propagation based on motion track results., black arrows indicate the underwater drag force. E Hydrodynamic drag distribution heat map during the motion of the robot. More details about comparison of the underwater robotic bending propagation and non-bending propagation are available in Supplementary Movie S1.

As shown in Fig. 4E, during bending propagation, hydrodynamic resistance was again concentrated in the bending zone, with its peak shifting distally over time. This pattern enabled the robot to reach the target position in 9.4 s, with total resistance work of 8.45 J. In comparison, the non-bending propagation mode took 20.4 s and consumed 8.88 J of resistance work. These results confirm that, under comparable energy expenditure, the bending propagation mode achieves significantly higher locomotion efficiency, with a velocity 2.18 times larger than that of the non-bending mode.

Underwater grasping performance of the robot

Inspired by octopuses, which approach target objects through bending propagation and use the neural network on their suction cups to detect whether they have contacted the target, we integrated flow rate sensors into the actuation of the suction cups in our robot. This resulted in the development of a robotic “approach-sense-grasp” strategy (Fig. 5A). In this strategy, the pneumatic system applies the air pressure from the bending propagation model to the robot. The flow rate sensor values at each segment are used to determine whether the suction cups have attached with the object. If successful, the robot executes the grasp and pulls the object back. If there is no attachment with object, the robot continues reaching forward.

A The robot’s “approach-sense-grasp” strategy, where Pij represents the chamber pressure of the j-th actuator in the i-th segment. B–E The snapshots of the robot’s end-effector approaching, attaching, grasping, and pulling back a floating object, where the object is an 80mm-diameter cylinder. F The feedback signal from the flow sensor during the attaching, grasping, and release of the object, with arrows and dashed lines indicating the respective times. G Grasping results of the robot’s end-effector in the bending-suction collaborative grasping for objects of different sizes and shapes, showing a cylinder, rectangular prism, and hexagonal prism, with diameters ranging from 40 mm to 160 mm. More details about the grasping ability tests are available in Supplementary Movie S2.

Under this strategy, Fig. 5B–E demonstrates the process of grasping floating object on the water surface, which is divided into four stages: approaching the target, attaching, grasping, and pulling back. During the approach phase, the water flow rate through the suction cup at each segment is 3.5 ml/s (Fig. 5F). When attached with the object, typically only part of the suction cups attaches to the target surface, and the flow rate drops to 1.9 ml/s. After the grasp is completed, all suction cups fully attach to the target surface, and the flow rate drops to 0 ml/s. Therefore, using six flow rate sensors, we can obtain the feedback information on the suction cup attachment status, the position of the attached object, and whether the object is successfully grasped.

Then, we evaluated the hybrid bending and suction grasping ability of a single segment. The results show that after attaching to an object, the flexible joint can grasp objects of various sizes, with diameters ranging from 40 mm to 160 mm, which is 0.26–1.1 times the initial length of the flexible joint. The object’s internal medium is water, with a mass range of 100–1100 g. The robot is also capable of grasping objects of different shapes (Supplementary Movie S2). Figure 5G shows the grasping and retrieval of square prisms, hexagonal prisms, and cylindrical objects.

Underwater grasping in open space

Based on the aforementioned grasping strategy, we tested the robot’s ability to grasp static floating objects (Supplementary Movie S3). The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 6. We selected a cylindrical object with a diameter of 80 mm as the target object. A magnet was placed at the bottom of the target object, enabling it to be attracted to a tripod positioned at the bottom of the pool. The object was placed ~1.2 m away from the root of the soft robotic arm, with an angle of 60° between the line connecting the root and the vertical direction.

A The robot’s end-effector approaches the target object with a bending propagation in 7.9 s. B After detecting attachment to the object, the robot stops moving, executes the grasping action, and pulls the target object back once successfully grasped. C Feedback signals from the flow sensor. Arrows and dashed lines represent the time when the object is successfully attached and grasped, respectively. More details about the floating objects grasping are available in Supplementary Movie S3.

We defined a successful attachment to the target object as follows: during the robot’s motion, a decrease in water flow speed must be detected by the flow sensors, and the reading must remain stable for at least 1 s. A successful grasp of the object was determined by ensuring that, during the joint bending process, the flow rate does not rise, and the sensor reading remains stable for 2 s.

The experimental process consists of the following three steps: First, the robot approaches the target object using bending propagation. If the object is successfully attached during the propagation process, as detected by the water flow sensor signals, the movement will be terminated, and the grasp will be executed. After a successful grasp, the robot will perform a pre-programmed pulling action. Our experimental results show that the robot can approach the target object in 8.0 s and retrieve it in 21.8 s.

By adjusting the bending angle of the first segment, the robot can achieve bending propagation in different directions (Supplementary Movie S3). The simulation results are shown in Fig. 7A, D, where the adjustment strategy for the robot’s bending angle is to keep the actuation amplitude of the dorsal actuators unchanged and adjust the actuation amplitude of the ventral actuators. Experimental results show that our system can grasp objects in different directions. Figure 7B, C, and E, F shows the robot grasping of objects located at 30° and 120° directions, and with the time cost of approaching target in 7.9 s and 11.0 s respectively. Our results demonstrate that the workspace of bending propagation can be expanded by adjusting the root direction.

A Simulation results of the robot bending propagation toward an angle of 30° to the vertical, with the subpanel in the lower left showing the length-time curves of the dorsal and ventral actuators. B The robot approaches and attaches to the target object underwater by bending propagation. C The robot grasps the target object and pulls it back. D Simulation results of the robot bending propagation toward an angle of 120° to the vertical, with the subpanel in the lower left showing the length-time curves of the dorsal and ventral actuators. E The robot approaches and attached to the target object underwater by bending propagation. F The robot grasps the target object and pulls it back. More details about the floating objects grasping are available in Supplementary Movie S3.

Underwater grasping in confined space

Due to the inherent safety and environmental adaptability of soft robots, we also demonstrated the robot’s grasping capabilities in spatial constrained environments. We found that the discrete bending segments of the robot cause changes in the distance between the boundaries on both sides during the bending propagation process. The trend of this change over time is shown in Fig. 8A. The maximum boundary distance \({s}_{\max }^{b}\) during the bending propagation process is related to the phase difference Δt, as well as the actuator length change rate factor ε.

A The distance-time curve between the two side boundaries during the bending propagation. B The relationship between the he phase difference \(\varDelta t\), the actuator length change rate factor \(\varepsilon\) and the boundary distance of the bending propagation, with asterisk indicating the value where the distance is minimized, when \(\varDelta t/T=0.24\) and \(\varepsilon =-48\). C Bending propagation simulation at the minimized value, where the robot is able to pass through a space with a distance of 3.8D, where D is the diameter of the robot’s base.

Through simulations, we recorded the relationship between the boundary distance \({s}_{\max }^{b}\) and the phase difference Δt and the actuator length change rate factor ε, as shown in Fig. 8B. By conducting these simulations, we identified the set of values for Δt and ε that minimize the boundary distance. The results are shown in Fig. 8C, where the minimum distance occurs when Δt/T = 0.24 and ε = −48. This value represents a 17.8% reduction in distance compared to the unoptimized parameter set.

We further conducted experiments on the robotic system (Supplementary Movie S4), with the experimental setup shown in Fig. 9A. We applied a constrained spatial environment by placing floating obstacles. The same floating object was placed ~1.2 m from the root of the robot, and the width of the constrained space was set to 290 mm, about 4.1 times the robot’s root diameter. First, the robot’s first segment attached to an acrylic plate using suction cups, then approached the target object using bending propagation. When detecting that the target object had been attached, it executed the grasp. After successfully grasping the object, the robot actively detached, and the object was retrieved with external assistance. The suction cup flow data from this experiment are shown in Fig. 9I, which can assist in determining both the robot’s attachment and detachment states, as well as the object’s attachment and detachment states.

A Experimental setup of the confined space, where the robot’s end-effector attach to an acrylic plate. Obstacles are placed on both sides of the robot, with a gap of 290 mm, and a floating cylindrical object is placed 1.2 m away from the robot’s base as the target. B–D The robot approaches the target object via bending propagation. E The robot attached to the target object. F The robot grasps the target object. G The robot’s base detaches. H The robot and the target object are pulled out of the confined space. I Feedback signals during the grasping process, with arrows and dashed lines representing the times of robot attachment and detachment, as well as the times when the object is attached to and grasped. More details about the grasping tests in confined space are available in Supplementary Movie S4.

Our results show that when the first segment is used as a base and attached to a surface in the environment, we can generate bending propagation motion simply by adjusting the total number of driving segments. This allows the robot to successfully retrieve a floating object from within a narrow space in 12.4 s.

Discussion

In this work, we developed a bending propagation model based on sequential actuation. The feature of this model is that it does not require solving for the overall configuration of the robot, instead, the robot’s behavior can be defined directly within the actuation space. Inspired by the octopus’s grasping behavior, this approach simplifies the model parameters for soft continuum robots during the grasping process, requiring only three parameters to generate bending propagation motion. Through simulations and robotic experiments, we also proved that the bending propagation can be generated by the phase difference in the propagated activation of the dorsal and ventral muscles of an octopus arm.

Underwater drag analysis revealed that the drag coefficient of the bioinspired soft continuum robot in the direction perpendicular to its longitudinal axis is ~30 times larger than that in the tangential direction. As a result, minimizing perpendicular motion through bending propagation leads to a significant reduction in drag. Comparative experiments between sequentially activated (bending propagation) and simultaneous activated (non-bending propagation) control modes showed that, under comparable total work against drag, the bending propagation achieved a locomotion speed 2.18 times faster than the non-bending approach. These results confirm that the proposed strategy offers an effective means of reducing hydrodynamic resistance during underwater locomotion.

Inspired by octopus, we demonstrated a robotic “approach-sense-grasp” strategy for grasping floating objects. The robot can perform grasping when the suction cups detect attachment with objects during bending propagation. This strategy simplifies the control during object grasping, where the robot’s base is simply aligned with the direction of the object. Then, it can perform bending propagation towards the object to complete the grasp.

Finally, we also demonstrated that the robot system can actively attach to environmental surfaces and execute a grasp without the need for a fixed base. After completing the grasp, the robot can actively detach and retrieve the object. This approach is particularly suitable for grasping in constrained environments. In such environments, sequential activation enables bending propagation to minimize the robot’s frontal area facing the flow, allowing it to traverse narrow spaces.

However, there are still some limitations in the current work. First, we neglect real-time feedback on the position of the target object. We use a pre-programmed method to perform bending propagation, but during this process, the robot’s deformation is not adjusted in real-time, which limits its ability to capture moving objects. Then, the robot’s motion velocity is still significantly slower compared to biological organisms. A biological octopus can complete a grasp on a target 1.2 times its arm length within 480 ms7, whereas our robot system requires ~10 s to perform the same task. Finally, although this study offers a preliminary demonstration that model parameter optimization enables effective grasping within confined spaces, the strategies employed by octopuses to actively modulate bending propagation and adapt to spatial constraints require further investigation in future work4,38.

In the future, we plan to use visual or chemical perception methods to detect the direction of the target object in real time, allowing for the real time control of bending propagation motion and enabling the robot to capture moving targets. We also aim to equip the soft continuum robot with an underwater mobility platform to enable grasping over a larger operational range. Ultimately, we hope to expand the application of this system to real-world marine environments, enabling tasks such as environmental exploration and object manipulation.

Methods

Biological observations

The underwater predatory behavior of octopus tentacles provides a valuable reference for the efficient underwater locomotion of bio-inspired robots. Therefore, we set up a biological observation platform in the laboratory. The experimental octopus was housed in a transparent seawater tank with dimensions of 45 cm × 45 cm × 35 cm. The water in the tank was artificial seawater, prepared by mixing purified water and sea salt in a specific ratio, maintaining a salinity of 27.2 PPT and a temperature range of 20–22 °C, to ensure an optimal environment for the octopus’s survival and activity. A high-speed camera (FASTCAM Mini UX100) was used to capture videos of the octopus performing bending propagation motions during predation, at a frame rate of 250 Hz.

Octopus-inspired soft continuum robot

The agile movement of octopus tentacles is primarily actuated by the coordinated action of multiple muscle groups within the tentacle. The extension and contraction of several longitudinal muscles, arranged stepwise along the axis of the tentacle, generate the three-dimensional bending motion of the tentacle. Spiral fibers of oblique muscles, coiled on the surface and inside the tentacle, enable the tentacle to twist. Transverse muscles distributed radially along the tentacle control its radial expansion12. During predation, the octopus mainly relies on the longitudinal muscles to approach and locate the target. Therefore, in our design, we omitted the twisting structures similar to the oblique muscles and developed a soft continuum robot with six serially connected, parallel multi-chamber flexible bending segments. Previous research has shown that the conical angle of the octopus’s tentacles helps with wrapping and attaching to targets23. Inspired by this, we incorporated a 1.5° conical angle into the overall configuration of the robot.

The bending segments of the robot consist of pneumatic artificial muscles. Considering the redundancy of the longitudinal muscles in the octopus’s tentacles and the minimal number of actuators required to achieve three-dimensional movement, we reduced the number of actuators per joint to three. The actuator consists of two parts: the inner part is a silicone tube, and the outer part is a folded fiber-restriction layer. Applying pressure to the silicone tube causes radial elongation of the actuator. Due to the asymmetric geometry, the elongating actuator compresses and causes joint bending. The pressure magnitude determines the bending angle, and combinations of different lengths of the three actuators allow for three-dimensional movement of the bending segment.

The cross section of the segment during bending is stabilized by frames arranged along the axial direction, preventing uncontrolled twisting and instability. On the side of the bending segment, there are four silicone suction cups arranged, which can attach to the target’s surface after contact. The bending and elongation of the soft continuum robot are driven by a multi-channel pneumatic system, and the negative pressure for the suction cups is provided by water pumps.

To characterize the effect of pressure on the bending and elongation of the soft robotic arm’s joint deformation, we calibrated the relationship between pressure and chamber length using the multi-channel pneumatic drive system. In the calibration experiment, the flexible joint was fixed in a shallow water environment and subjected to a pressure range of 0–240 kPa, with a pressure increment of 20 kPa. The length variation of the actuator at different pressures was analyzed using image processing. During the measurement, the center arc length of the actuator was chosen as the chamber length. Figure 10B shows the variation of chamber length with pressure.

Kinematic modeling of the soft continuum robot

In this section, we introduce the kinematic modeling of the octopus-inspired soft continuum robot. Kinematic modeling primarily addresses the mapping from the lengths of the individual soft actuators {li} to the end positions of the bending segments {xi, yi, zi}. Here, i represents the length of the i-th bending segment. The numbering of the actuators within the bending segment is shown in Fig. 10A.

Unlike traditional constant curvature (CC) continuum robot modeling approaches, we introduce a variable curvature (VC) model with cross-sectional changes. This model divides each bending segment into m units. The center curve of each unit is simplified to a circular arc, and the equivalent curve of adjacent joint segments is tangent to each other. This method allows for more accurate representation of the non-uniform bending behavior typically observed in tapered soft continuum robots.

The steps for kinematic modeling can be divided into two main phases. First, we solve the mapping from the chamber length of each unit {lijk} to its configuration space {rij, θij, φij}. Let rij represent the bending radius of the j-th unit, θij represent the bending angle of the j-th joint unit, and φij represent the deflection angle of the j-th joint unit. Here, i refers to the i-th segment of the robot, j refers to the j-th unit of the segment, and k refers to the k-th actuator of the segment. As shown in Fig. 10A, we need to utilize the constant curvature model as a bridge. From the geometric relations of constant curvature, we have:

The {\({\hat{l}}_{{ij}k}\)} refers to the virtual length of the actuator under deformation with constant curvature, representing the unit. According to previous conclusions in ref. 39, it can be approximated by the following equation,

Next, we solve the mapping from the unit configuration space to the end position of the joint. The transformation matrix from the (j-1)-th unit to the j-th unit is as follows:

The transformation matrix from the (i-1)-th flexible joint to the i-th segment is as follows:

The end position of the i-th segment can be calc ulated using the following equation:

Thus, we have established the forward kinematic model of the soft continuum robot, which allows the calculation of the robot’s configuration and end position based on the actuator lengths.

Data availability

The minimal dataset required to interpret and replicate the findings of this study is provided within the article and supplementary materials. Additional raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying modeling code for this study can be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Mather, J. A. How do octopuses use their arms? J. Comp. Psychol. 112, 306 (1998).

Kennedy, E. L., Buresch, K. C., Boinapally, P. & Hanlon, R. T. Octopus arms exhibit exceptional flexibility. Sci. Rep. 10, 20872 (2020).

Kier, W. M. & Smith, A. M. The structure and adhesive mechanism of octopus suckers. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 1146–1153 (2002).

Gutnick, T., Zullo, L., Hochner, B. & Kuba, M. J. Use of peripheral sensory information for central nervous control of arm movement by Octopus vulgaris. Curr. Biol. 30, 4322–4327 (2020).

Levy, G., Flash, T. & Hochner, B. Arm coordination in octopus crawling involves unique motor control strategies. Curr. Biol. 25, 1195–1200 (2015).

Gutfreund, Y., Matzner, H., Flash, T. & Hochner, B. Patterns of motor activity in the isolated nerve cord of the octopus arm. Biol. Bull. 211, 212–222 (2006).

Sumbre, G., Gutfreund, Y., Fiorito, G., Flash, T. & Hochner, B. Control of octopus arm extension by a peripheral motor program. Science 293, 1845–1848 (2001).

Hanassy, S., Botvinnik, A., Flash, T. & Hochner, B. Stereotypical reaching movements of the octopus involve both bend propagation and arm elongation. Bioinspir. Biomim. 10, 035001 (2015).

Gutfreund, Y., Flash, T., Fiorito, G. & Hochner, B. Patterns of arm muscle activation involved in octopus reaching movements. J. Neurosci. 18, 5976–5987 (1998).

Yekutieli, Y. et al. Dynamic model of the octopus arm. I. Biomechanics of the octopus reaching movement. J. Neurophysiol. 94, 1443–1458 (2005).

Gutfreund, Y. et al. Organization of octopus arm movements: a model system for studying the control of flexible arms. J. Neurosci. 16, 7297–7307 (1996).

Flash, T. & Zullo, L. Biomechanics, motor control and dynamic models of the soft limbs of the octopus and other cephalopods. J. Exp. Biol. 226, jeb245295 (2023).

Rus, D. & Tolley, M. T. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 521, 467–475 (2015).

Yasa, O. et al. An overview of soft robotics. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 6, 1–29 (2023).

McMahan, W. et al. Field trials and testing of the OctArm continuum manipulator. In Proceedings 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2006. ICRA 2006. 2336–2341 (IEEE, 2006).

Laschi, C. et al. Soft robot arm inspired by the octopus. Adv. Robot. 26, 709–727 (2012).

Wu, S. et al. Stretchable origami robotic arm with omnidirectional bending and twisting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2110023118 (2021).

Calisti, M. et al. An octopus-bioinspired solution to movement and manipulation for soft robots. Bioinspir. Biomim. 6, 036002 (2011).

Wu, M. et al. Octopus-inspired underwater soft robotic gripper with crawling and swimming capabilities. Research 7, 0456 (2024).

Cianchetti, M., Calisti, M., Margheri, L., Kuba, M. & Laschi, C. Bioinspired locomotion and grasping in water: the soft eight-arm OCTOPUS robot. Bioinspir. Biomim. 10, 035003 (2015).

Sfakiotakis, M., Kazakidi, A. & Tsakiris, D. Octopus-inspired multi-arm robotic swimming. Bioinspir. Biomim. 10, 035005 (2015).

Mathew, A. T. et al. ZodiAq: an isotropic flagella-inspired soft underwater drone for safe marine exploration. Soft Robot. 12, 410–422 (2025).

Xie, Z. et al. Octopus arm-inspired tapered soft actuators with suckers for improved grasping. Soft Robot 7, 639–648 (2020).

Liu, J., Iacoponi, S., Laschi, C., Wen, L. & Calisti, M. Underwater mobile manipulation: a soft arm on a benthic legged robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 27, 12–26 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. An underwater robotic system with a soft continuum manipulator for autonomous aquatic grasping. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 29, 1007–1018 (2024).

Della Santina, C., Duriez, C. & Rus, D. Model-based control of soft robots: a survey of the state of the art and open challenges. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 43, 30–65 (2023).

Armanini, C., Boyer, F., Mathew, A. T., Duriez, C. & Renda, F. Soft robots modeling: a structured overview. IEEE Trans. Robot. 39, 1728–1748 (2023).

Wang, T., Halder, U., Gribkova, E., Gazzola, M. & Mehta, P. G. Control-oriented modeling of bend propagation in an octopus arm. In 2022 American Control Conference (ACC) 1359–1366 (IEEE, 2022).

Tekinalp, A. et al. Topology, dynamics, and control of a muscle-architected soft arm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2318769121 (2024).

Chang, H.-S. et al. Energy-shaping control of a muscular octopus arm moving in three dimensions. Proc. R. Soc. A 479, 20220593 (2023).

Duan, H., Huo, M. & Fan, Y. From animal collective behaviors to swarm robotic cooperation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwad040 (2023).

Matthews, D. G. & Lauder, G. V. Fin–fin interactions during locomotion in a simplified biomimetic fish model. Bioinspir. Biomim. 16, 046023 (2021).

Bujard, T., Giorgio-Serchi, F. & Weymouth, G. D. A resonant squid-inspired robot unlocks biological propulsive efficiency. Sci. Robot. 6, eabd2971 (2021).

Xie, Z. et al. Octopus-inspired sensorized soft arm for environmental interaction. Sci. Robot. 8, eadh7852 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Tuna robotics: a high-frequency experimental platform exploring the performance space of swimming fishes. Sci. Robot. 4, eaax4615 (2019).

Ren, Z., Hu, W., Dong, X. & Sitti, M. Multi-functional soft-bodied jellyfish-like swimming. Nat. Commun. 10, 2703 (2019).

Yekutieli, Y., Sagiv-Zohar, R., Hochner, B. & Flash, T. Dynamic model of the octopus arm. II. Control of reaching movements. J. Neurophysiol. 94, 1459–1468 (2005).

Richter, J. N., Hochner, B. & Kuba, M. J. Octopus arm movements under constrained conditions: adaptation, modification and plasticity of motor primitives. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 1069–1076 (2015).

Mahl, T., Hildebrandt, A. & Sawodny, O. A variable curvature continuum kinematics for kinematic control of the bionic handling assistant. IEEE Trans. Robot. 30, 935–949 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation support projects, China (Grant No. 623B2012), and the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Nos. 2024YFB4707300), and National Science Foundation support projects, China (Grant No. 62425303).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and L.W. conceived the concept and wrote the manuscript. J.L. and Z.Z. carried out the experiments. All authors analyzed and interpreted the Data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Zhu, Z. & Wen, L. Underwater soft arm grasping with simplified control using octopus-inspired bending propagation. npj Robot 4, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00066-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00066-9