Abstract

Minimally invasive neurosurgery is limited by narrow corridors and restricted instrument dexterity. To overcome these challenges, we developed a handheld robotic system to enhance surgical performance. This preclinical in vivo study (IDEAL Stage 0) presents the first evaluation of the system across three neurosurgical approaches - subfrontal, transparietal, and supracerebellar in two ovine models. Three robotic end-effectors (dissector, forceps, curette) were assessed for safety and feasibility. Safety was confirmed via intraoperative monitoring and necropsy, with no device-related morbidity, mortality, or adverse events. All predefined tasks were feasible; the percentage of tasks rated “very easy” or “easy” was 81% (dissector), 96% (forceps), and 100% (curette). Surgeons reported high usability, suggesting refinements related to instrument sharpness and retraction force. These results support the safety and feasibility of the system and highlight its potential to improve surgical precision while preserving surgeon autonomy. The findings justify further refinement and progression to early human studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The adoption of minimally invasive techniques in neurosurgery has been heralded by the promise of reducing surgical morbidity whilst maintaining or improving patient outcomes1. Endoscopic and keyhole approaches offer improved access to deep-seated intracranial lesions whilst minimising collateral tissue damage2. However, these approaches impose technical constraints through their narrow surgical corridors limiting instrument manoeuvrability, compounded by existing straight, inflexible tools3,4. These challenges not only increase the complexity of procedures but also necessitate extensive training, resulting in a minority of technically proficient surgeons being concentrated in few ‘centres of excellence’5. Overcoming these limitations requires innovation in surgical instrumentation to enhance dexterity and ease of use.

To address these challenges, we have developed a dexterity-enhancing handheld robotic system designed to augment the surgeon’s capabilities in minimally invasive neurosurgery6. Currently, there are no commercially available robotic systems specifically designed for soft tissue manipulation in minimally invasive neurosurgery. This device is the first of its kind, offering articulated end-effectors to enhance dexterity through a handheld platform7.

Unlike telesurgical robots used in other surgical specialties - such as the da Vinci system - this handheld robot does not rely on remote control from a console and does not require substantial changes to the operating environment. Instead, it integrates readily into existing neurosurgical workflows, allowing direct control by the surgeon at the bedside.

Prior to animal study, preclinical studies in both simulated and cadaveric models have shown that the system enhances dextrous workspace reach, improves surgical efficiency, and is easy to use6,7. It has demonstrated feasibility across eight endoscopic skull base approaches in cadavers8, outperforming standard instruments in terms of workspace reach. Notably, in simulated pituitary tumour resections, less experienced surgeons using the device achieved similar or superior technical performance compared to experts using conventional tools7—highlighting its potential to shorten the learning curve and expand access to minimally invasive neurosurgical techniques. The device design was refined in response to each of these studies to optimise safety and readiness for in vivo evaluation.

Despite these promising results, neither simulated nor cadaveric models replicate the challenges of tissue perfusion, dynamic intracranial pressure, and intraoperative haemostasis, all of which influence surgical technique and instrument performance9. In vivo validation is therefore a critical step in the translational process, enabling real-time assessment of safety, usability, and technical functionality in a biologically relevant environment10.

In this study, we present the first in vivo evaluation of our dexterity-enhancing handheld robotic system. By testing the device in an acute animal model across multiple neurosurgical approaches, we aim to assess its initial safety and feasibility while identifying refinements necessary for future clinical translation.

Results

Safety

No adverse events were observed in any of the Study Animals following the use of the three instruments (dissector, forceps, and curette) across all approaches (subfrontal, transparietal, and supracerebellar approaches). No complications or device failures were observed during the acute procedures and no early elective sacrifice or early deaths occurred in this study.

In the necropsy evaluation, focal reddish coloration of tissue was seen in both animals suggestive of mild to moderate haemorrhage at the surgical site which was related to the surgical approach and not to the use of the device (Fig. 1). In all cases, this was observed along the tract of the approach or at the site of surgical task performance and therefore deemed intentional.

Feasibility

All approaches were feasible with each instrument, and Table 1 demonstrates the task difficulty encountered across approaches with the various end effectors. Examples of the robot end-effectors in use can be viewed in the accompanying video (Supplementary movie 1).

Dissector

The dissector was deemed the hardest to use of the three instruments tested all approaches (Fig. 2). It performed best in the supracerebellar approach and worst in the subfrontal approach (Fig. 2). Comments included that it was “too sharp” when dissecting brain tissue, “it doesn’t return to a neutral position on its own, but it’s easy to compensate”, and that it “was good for moving tissue, but not sharp enough to cut the arachnoid tissue”. The dissector was considered easy to use for manipulating arachnoid tissue (albeit not sharp enough), blood vessels, and brain tissue, in the first animal. In the second, the usability of the dissector was considered very easy for manipulating arachnoid tissue and blood vessels (very appropriate and precise); however, the dissector was difficult to use in the manipulation of brain tissue, requiring adaptation according to tissue fragility. Its use in vivo is demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Forceps

Figure 4 illustrates us of the forceps. The forceps was deemed easier to use compared to the dissector, but harder to use compared to the curette across all approaches (Fig. 2). The forceps performed best in the transparietal approach and worst in the subfrontal approach. Feedback included that they “work as expected, force was correct, but difficulty related to the narrow opening and not from [the] instrument”, “It could potentially be easier to push for a release”, “slightly too sharp” and that “the head was tilted down when fully closed”. The usability of the forceps was considered easy for manipulating arachnoid tissue (albeit not sharp enough), blood vessels and brain tissue.

Curette

The curette end-effector, shown in Fig. 5, demonstrated the highest overall performance across all approaches, It performed the best, consistently, in the subfrontal approach and its poorest performance was in the second animal during the transparietal approach (Fig. 3). It was considered very easy when manipulating nerves during the subfrontal approach, very easy in the first animal and easy in the second animal of the transparietal approach, and was predominantly deemed very easy to manipulate cerebellar tissue. The forces applied were described as “appropriate and correct”, and the instrument “very easy and precise”.

Discussion

This study represents the first in vivo evaluation of a dexterity-enhancing handheld robotic system for endoscopic neurosurgery. The robotic end-effectors - dissector, forceps, and curette—were assessed across subfrontal transparietal, and supracerebellar, approaches, demonstrating effective tissue manipulation and workspace reach, and no adverse events. Using the dissector across all approaches, tasks were mainly very easy (n = 12/27, 44%) or easy (n = 10/27, 37%), and less frequently hard (n = 5/27). The forceps performed tasks were also very easy (n = 12/27, 44%) and easy (n = 14/27, 52%) and only rarely hard (n = 1/27). Task attempts using the curette end effector were predominantly deemed very easy (n = 20/27, 74%) and easy (n = 7/27, 26%). All end-effectors demonstrated feasibility, as no task attempt was deemed very hard.

The dissector was particularly effective for arachnoid and brain tissue dissection, although its sharpness required careful force modulation. The forceps enabled controlled vessel and brain tissue manipulation, but manual adjustments were occasionally required to optimize grip. The curette provided optimal manoeuvrability, particularly in brain tissue resection. Importantly, all three instruments allowed for precise and controlled manipulation of brain tissue, validating their usability for neurosurgical applications. Feasibility testing provided valuable feedback for iterative device development.

Macroscopic evaluation revealed mild to moderate haemorrhage at the surgical sites, which was deemed intentional, attributed to the surgical approach and tasks performed, rather than the Handheld Robot itself. The absence of intraoperative complications and the smooth execution of all procedures suggest that the robotic system is both safe and feasible in the evaluated context and demonstrated initial safety.

Minimally invasive neurosurgical approaches, particularly in endoscopic skull base surgery, are limited by narrow operative corridors and rigid instruments3, which constrain a surgeon’s dextrous workspace reach and complicate precise tissue manipulation. Previous studies have demonstrated that robotic assistance can enhance instrument articulation and reduce the learning curve for complex neurosurgical procedures7,11.

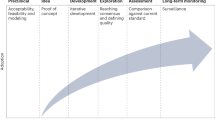

As per the IDEAL framework for surgical robotics, early-stage evaluations must establish safety, feasibility, and clinical potential12. Preclinical research on surgical robotics has predominantly focused on cadaveric and simulated models, which, while useful for assessing basic functionality, lack the physiological complexity of live tissue. Studies have emphasized the importance of real-time feedback, haemostatic challenges, and dynamic tissue responses, which can only be evaluated in an in vivo setting10.

Despite this, limited evidence exists for soft tissue robotic evaluations in live neurosurgical animal models. The available studies in cranial neurosurgical robots have focused primarily on osteotomies13, arterial sutures14, electrode implantations15, and drug delivery16. Most in vivo robotic studies outside of neurosurgery involve master-slave systems, which pose challenges such as high operating costs, increased operating room footprints, and workflow integration challenges but also have limited functionality in confined operative workspaces4. Examples of such systems evaluated in live animals include those by Wang et al., who evaluated a master-slave robotic system in 5 porcine models17, and Lorincz et al., who studied the Zeus Microwrist Surgical System for minimally invasive pyeloplasty18. Additionally, Morita et al. explored a microsurgical robotic system designed for deep surgical fields, testing its functionality on Wistar rats for vascular anastomoses14. Collectively, these studies found benefit in evaluating their devices as part of a systematic approach, prior to first-in-human studies.

Few handheld articulated devices have undergone in vivo testing. Kim et al. compared ArtiSential, a multi-degree-of-freedom laparoscopic instrument, to the Da Vinci system in renal surgery on nine porcine models19, demonstrating comparative performance to an established robotic system to support its feasibility, and outlining potential surgical applications through analysing specific task performance. Massari et al. assessed FlexDex, a wristed handheld needle holder, for laparoscopic gastropexy in 16 dogs20, reporting reduced surgical time but a steep learning curve. The findings from this study align with the broader literature on handheld devices, including, supporting the premise that robotic augmentation can expand the capabilities of minimally invasive techniques21,22,23. Unlike teleoperated robotic systems, which can be bulky and workflow-disruptive, they concluded that handheld robotic platforms can offer seamless integration into standard surgical practice, providing enhanced dexterity while preserving surgeon autonomy.

The findings of these studies enhance the preclinical evidence base by demonstrating feasibility in live models, which arguably is the highest fidelity model prior to human testing. Our experience is in concert with these observations, performing neurosurgical tasks across three neurosurgical approaches, demonstrating feasibility and initial safety.

The main strength of this study is its systematic in vivo evaluation of a robotic surgical robot across multiple neurosurgical approaches, providing biologically relevant data on safety, feasibility, and usability. The use of multiple test articles enabled direct comparisons between different instrument functionalities, allowing for targeted refinements in future iterations. The study also followed the IDEAL framework, ensuring that the device’s early-stage evaluation was conducted in a structured and rigorous manner.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study was conducted in an acute animal model that differs anatomically from humans - being longer and flatter, with larger cranial sinuses and smaller brain volume. These differences, combined with the simulated operating room environment, limit the applicability of the findings to clinical neurosurgical conditions such as tumours or vascular malformations. Second, two members of the authorship team hold shares in Panda Surgical, including the neurosurgeon who performed the procedures. To mitigate potential bias, an independent laboratory team oversaw study monitoring, outcome recording, and safety assessment. Third, no histopathological analysis was performed, which may have provided further insight into microscopic tissue effects and enhanced the assessment of safety. Fourth, the feasibility assessment was based on a pragmatic framework rather than a validated instrument, which is consistent with the exploratory aims of IDEAL Stage 0 but limits comparability with other platforms. Fifth, the small sample size restricts generalisability. While small cohorts are appropriate for IDEAL Stage 0 and the number of animals was minimised in accordance with ethical principles of reduction and refinement, future studies will require larger sample sizes to explore variation in performance and early signals of effectiveness.

This study represents the first in vivo evaluation of a dexterity-enhancing handheld robotic system for minimally invasive neurosurgical approaches, designed to specifically evaluate safety and feasibility in line with IDEAL Stage 0 guidance. It demonstrates initial safety and feasibility across subfrontal, transparietal and supracerebellar approaches. All three end-effectors enabled effective and precise tissue manipulation, with user feedback highlighting ease of use and adaptability to different surgical tasks. These findings support further development and optimisation of the system, contributing to the growing evidence base for robotic-assisted neurosurgery and the justification for future in human studies of the described system.

Future work will follow a structured progression through the IDEAL framework. At IDEAL Stage 1, the device should be evaluated with structured usability assessment using validated tools such as the System Usability Scale (SUS) and formal human factors methods. Histopathological analysis should be incorporated to assess tissue-level safety more systematically. Early clinical studies at Stage 2a will allow for evaluation of learning curves, workflow integration, and real-world usability. Comparative studies - including cohort-based or randomised designs - would be appropriate at Stage 2b and beyond, once feasibility and safety have been established. A previous phantom-based study suggesting non-inferior effectiveness and reduced workload compared to standard instruments provides preliminary justification for this pathway7.

Methods

Study design

This prospective, preclinical in vivo study evaluated the device in two live ovine models (IDEAL Stage 0). The study was conducted at an accredited testing facility (VERANEX, Paris) which specializes in preclinical evaluation of medical devices. All experiments were conducted in compliance with the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (Council of Europe ETS 123), the French national legislation, and ISO 10993-2:2022 animal welfare requirements. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Testing Facility (Ethics Committee No. 37), and the study was conducted under project NEUROLOGIE 15018. The Testing Facility is fully accredited by AAALAC International (accreditation numbers: D 75-14-01 and H 91-243-101). The centre provided the necessary surgical facilities, animal housing, and veterinary oversight to ensure compliance with ethical and regulatory guidelines. Three neurosurgical approaches were conducted on each animal to determine the device’s safety and feasibility, and each animal was euthanized at the end of the acute procedure for necropsy and macroscopic evaluation. The study meets the criteria for ARRIVE Essential checklist (Supplementary file 1).

All feedback related solely to device performance and procedural usability. As no personal or health-related information was collected, and all participants were members of the research team acting in their professional capacity, this activity did not constitute human subjects research requiring separate ethical approval.

Animal models

Two adult female Ile de France sheep were included in this study. The ovine model is recognized for assessing tissue response to medical devices, is physiologically similar model to humans24, and has a thinner skull (compared to other commonly used models e.g. porcine models) to facilitate access via craniotome. Its preclinical application in neurosurgery is well established for training25,26 and device evaluation27,28. Each animal underwent three neurosurgical approaches—at least once—with necropsy and macroscopic evaluation of the brain conducted post-procedure. Prior to the in vivo study, cadaveric animal models of the same species were tested, to ensure the model was appropriate for in vivo testing—which was conducted at the same study centre.

Device description

The Panda Surgical Dexterity-Enhancing Handheld Robot is a surgical robot designed to assist surgeons in the removal of tumors in the brain and spine6,7,29. It is a handheld system featuring miniature, articulated end-effectors that provide 2–3 degrees of freedom, enabling enhanced dexterity and reach in confined spaces. The system is compatible with image guidance for surgical approach planning, but does not require it to operate. The device operates co-axially alongside an endoscope for visualisation. Through a single entry point (e.g. a burr hole), it allows precise manipulation within narrow, deep-seated anatomical corridors, where conventional rigid instruments are often limited (Fig. 6). The device is fully controlled by the surgeon. It has no autonomous functions, although future iterations may incorporate AI to suppress unwanted movements.

The handheld robotic system consists of three core components:

-

Interchangeable articulated end-effectors: These include various tools like forceps, curettes, and dissectors, all designed for different stages of tumor removal. Each tool provides pitch and yaw articulation, with some featuring a third DoF for opening and closing (e.g. forceps). These instruments are based upon existing, standard instruments used in neurosurgery.

-

Ergonomic Handheld Controller: The controller uses a rotating joystick to manipulate the end-effectors, offering precise control. Its design is adaptable to various hand sizes and handedness, making it comfortable for extended use. This component houses the motor drivers and electronics, keeping the Handheld Robot lightweight and easy to handle.

-

Console: The console ensures smooth and reliable power delivery.

To ensure that the device would be suitable to be evaluated in animals, some device features, primarily the ones focusing on device safety, needed to be updated. Development around the wristed instruments focused on manufacturing techniques and materials selection. Precision manufacturing ensured that the joint-design was within operational tolerances, while the patient-contacting components of the device - namely the tendons, joints and shafts—were replaced with biocompatible materials. Simultaneously, the instrument plastics were replaced with autoclaveable 3D printed parts. Neither biocompatibility nor sterilisation were required for this acute study, but it was still important to evaluate these new materials under realistic operative conditions.

In parallel, the internal electronics of the handheld controller were upgraded with components offering improved electrical safety, and a separate console with a medical-grade power supply was introduced to provide regulated, compliant power to the system. Finally, the control software, which translates user input into joint movement, was refined to better align with applicable software safety standards.

Neurosurgical approaches

Three approaches were selected—one anteriorly, one central, and one posteriorly – based on model feasibility and representativeness in terms of manipulating a variety of tissues encountered in neurosurgery. The attending neurosurgeon performed all tasks with the device, and was assisted by two neurosurgical residents and a veterinarian with experience in neurosurgery. The attending neurosurgeon and neurosurgical residents have prior experience with the device in both simulated phantom and cadaveric use prior to this study and were trained to use the system by the device developers. Procedures were performed under general anesthesia in an operating theatre. All animals were positioned in ventral recumbency and draped to expose the frontal, parietal, and occipital regions. Skin incisions were performed according to the planned craniotomy site. In all approaches an endoscope (Karl Storz, 4 mm) was used to visualize the operative site.

Subfrontal approach

Two burr holes using a perforator drill were fashioned and the dura dissected away. Two craniotomies (2 cm × 2 cm) were fashioned to expose the frontal region dura mater. The dura mater was opened, and the frontal lobes were retracted with a handheld malleable brain retractor.

Transparietal approach

Two burr holes were performed over each parietal lobe. A dissector was used to free dura from either side of the superior sagittal sinus. A 2 cm × 4 cm craniotomy was performed to reveal the dura across both hemispheres. The dura mater was opened over the parietal lobe on one side. The parasagittal sulcus was dissected towards the lateral ventricle.

Supracerebellar approach

Two burr holes were fashioned using a perforator drill, and the dura was dissected from the bone edges. A midline, 2 cm × 3 cm craniotomy was performed using a craniotome to expose the tentorium cerebelli. The dura mater was incised and the cerebellum exposed. Handheld malleable brain retractors and suction were used to access the pineal region.

Study tasks

The subfrontal approach was performed twice (left and right) on each animal and the transparietal approach was performed twice on one animal, and once on the second animal owing to time constraints. The supracerebellar approach was performed once on each animal as it is a midline approach. Following completion of the surgical approach, the surgeon performed a series of pre-defined tasks using each robotic end-effector (dissector, forceps and curette). The study procedures are outlined in Table 2 which define the pre-specified tasks and tissue manipulated for each approach.

Anesthetic care

Prior to surgery, study animals were fasted for at least 12 h while having unrestricted access to water. They underwent daily health checks for seven days pre-operatively, with body weight and temperature recorded at least once before the procedure. Serum markers were assessed pre-operatively, which were all within normal limits. Animals were anesthetized in line with current veterinary practice. Premedication with intramuscular morphine and midazolam was administered for sedation. The animals were inducted using intravenous midazolam and propofol, and following intubation anesthesia was maintained with propofol, sufentanil, midazolam and isoflurane. Cefazolin was given intravenously before surgery and every two hours thereafter. Continuous monitoring of ECG, arterial blood pressure, end-tidal CO₂, core temperature, SpO₂, and heart rate was conducted throughout the procedure.

Pathology

A gross necropsy was performed by a staff veterinarian after euthanasia to evaluate the brain. The brain was harvested, weighed, assessed macroscopically. Any abnormal macroscopic finding was also photographed, and the brain was sectioned coronally to evaluate potential iatrogenic injury or other relevant findings.

Study outcomes

Safety

Safety was determined through intraoperative adverse events related to the device, which was assessed through necropsy at the end of procedure and recording of early elective sacrifice or death of the study animal. Unexpected tissue deformation, hemorrhage or injury to brain tissue on macroscopic evaluation were evaluated post-procedure. Early elective sacrifice was defined as euthanasia of the study animal prior to acute procedure termination. Early death was defined as any Study Animal that dies before the end of the acute procedure. The device was deemed safe if no device-related adverse events were observed, and safety outcomes were determined by a staff veterinarian with expertise in medical device evaluation independent of the device developers.

Feasibility

Feasibility was defined as the ability for the device to perform pre-defined tasks to manipulate tissue in each approach. Tasks could be deemed very hard (4—The instrument could not complete the intended task safely or effectively), hard (3—The task was completed but with notable difficulty. Instrument manipulation was less intuitive or required significant compensation to avoid tissue damage), easy (2—The maneuver was generally smooth and controllable but may have required minor adjustments (e.g., repositioning or slight change in angle)) or very easy (1—The maneuver was performed with minimal effort, high precision, and excellent control, requiring no adjustment or compensation). A score of 1, 2 or 3 was deemed feasible. The feasibility assessment used a pragmatic, predefined scoring system to enhance consistency of evaluation across procedures and instruments. While not based on a previously validated survey tool, this approach is appropriate for early-stage (IDEAL Stage 0) studies focused on initial safety and feasibility, and has been employed in previous device evaluations at our institution. Device usability was collected via qualitative feedback throughout the procedural tasks. Feasibility scores and usability data were provided by the neurosurgeon performing the tasks, supervised by a staff veterinarian who recorded the results (Table 3).

Statistical analysis

Data were presented descriptively by approach and by instrument.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Gassner, H. G., Schwan, F. & Schebesch, K.-M. Minimally invasive surgery of the anterior skull base: transorbital approaches. GMS Curr. Top. Otorhinolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 14, Doc03 (2016).

Jarmula, J., de Andrade, E. J., Kshettry, V. R. & Recinos, P. F. The current state of visualization techniques in endoscopic skull base surgery. Brain Sci. 12, 1337 (2022).

Marcus, H. J. et al. Endoscopic and keyhole endoscope-assisted neurosurgical approaches: a qualitative survey on technical challenges and technological solutions. Br. J. Neurosurg. 28, 606–610 (2014).

Marcus, H. J. et al. Comparative performance in single-port versus multiport minimally invasive surgery, and small versus large operative working spaces. Surg. Innov. 23, 148–155 (2016).

Fleseriu, M. et al. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing’s disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 9, 847–875 (2021).

Dimitrakakis, E. et al. Handheld robotic device for endoscopic neurosurgery: system integration and pre-clinical evaluation. Front. Robot. AI 11, 1400017 (2024).

Starup-Hansen, J. et al. A Handheld Robot for Endoscopic Endonasal Skull Base Surgery: Updated Preclinical Validation Study (IDEAL Stage 0). J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base a- 2297-3647 https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2297-3647 (2024).

Starup-Hansen, J. et al. Applicability of a dexterity-enhancing handheld robot for 360° endoscopic skull base approaches: an exploratory cadaver study. Oper. Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.1227/ons.0000000000001582 (2025).

James, H. K., Chapman, A. W., Pattison, G. T. R., Griffin, D. R. & Fisher, J. D. Systematic review of the current status of cadaveric simulation for surgical training. Br. J. Surg. 106, 1726–1734 (2019).

Marcus, H. J. et al. IDEAL-D framework for device innovation: a consensus statement on the preclinical stage. Ann. Surg. 275, 73–79 (2022).

Shlobin, N. A., Huang, J. & Wu, C. Learning curves in robotic neurosurgery: a systematic review. Neurosurg. Rev. 46, 14 (2022).

Marcus, H. J. et al. The IDEAL framework for surgical robotics: development, comparative evaluation and long-term monitoring. Nat. Med. 30, 61–75 (2024).

Winter, F. et al. Advanced cutting strategy for navigated, robot-driven laser craniotomy for stereoelectroencephalography: an in Vivo non-recovery animal study. Front. Robot. AI 9, (2022).

Morita, A. et al. Microsurgical robotic system for the deep surgical field: development of a prototype and feasibility studies in animal and cadaveric models. J. Neurosurg. 103, 320–327 (2005).

Rau, A., Urbach, H., Coenen, V. A., Egger, K. & Reinacher, P. C. Deep brain stimulation electrodes may rotate after implantation—an animal study. Neurosurg. Rev. 44, 2349–2353 (2021).

Partridge, B. et al. Advancements in drug delivery methods for the treatment of brain disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 9 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric lesions by using a master and slave transluminal endoscopic robot: an animal survival study. Endoscopy 44, 690–694 (2012).

Lorincz, A. et al. Totally minimally invasive robot-assisted unstented pyeloplasty using the Zeus Microwrist Surgical System: an animal study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 40, 418–422 (2005).

Kim, J. K. et al. Laparoscopic renal surgery using multi degree-of-freedom articulating laparoscopic instruments in a porcine model. Investig. Clin. Urol. 64, 91–101 (2023).

Massari, F. & Kelly, G. M. M. Learning curve in two-port laparoscopic gastropexy using FlexDex. Anim. Open Access J. MDPI 14, 2016 (2024).

Bagga, V. & Bhattacharyya, D. Robotics in neurosurgery. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 100, 23–26 (2018).

Singh, R. et al. Robotics in neurosurgery: current prevalence and future directions. Surg. Neurol. Int. 13, 373 (2022).

Lin, T., Xie, Q., Peng, T., Zhao, X. & Chen, D. The role of robotic surgery in neurological cases: A systematic review on brain and spine applications. Heliyon 9, e22523 (2023).

Murray, S. J. & Mitchell, N. L. The translational benefits of sheep as large animal models of human neurological disorders. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 831838 (2022).

Cadaveric sheep head model for anterior clinoidectomy in neurosurgical training. World Neurosurg. 175, e481–e491 (2023).

Morosanu, C. O. et al. Neurosurgical cadaveric and in vivo large animal training models for cranial and spinal approaches and technique a systematic review of the current literature. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 53, 8–17 (2019).

Santangelo, G. et al. Treatment of hydrocephalus in an ovine model with an intraparenchymal stent. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 32, 437–446 (2023).

Oxley, T. J. et al. An ovine model of cerebral catheter venography for implantation of an endovascular neural interface. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.11.JNS161754 (2018).

Dimitrakakis, E. et al. Robotic handle prototypes for endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: pre-clinical randomised controlled trial of performance and ergonomics. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 50, 549 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the expert input given by the Veranex team in Paris, France lead by Olivier Chevenement and Lucy Hucault in the delivery of this study. Dr Marcus is funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London. Dr Hanrahan is supported by an NIHR academic clinical fellowship. The development of the Dexterity-Enhancing Handheld Robot is funded by the NIHR i4i PDA award (NIHR206456). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The testing of the Robot is funded by Panda Surgical.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H., J.S.H., E.D., and H.J.M. conceptualized and designed the study, conducted data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. E.D. contributed to the hardware development, methodology, data analysis, and critical revision of the manuscript. H.J.M. conceptualised and designed the study, aided with data interpretation and provided substantial editorial feedback. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dimitrakakis and Marcus are employed by and hold shares in Panda Surgical. Two patents are registered to Dimitrakakis that relate to the device evaluated in this research: Robotic surgical systems having handheld controllers for releasably coupling interchangeable dexterous end-effectors (Patent number: 12257015) and Handheld surgical systems with interchangeable dexterous end-effectors (Patent number: 12150729). Marcus and Hanrahan are authors of the IDEAL Robotics Framework. There are no other competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanrahan, J.G., Starup-Hansen, J., Dimitrakakis, E. et al. Safety and feasibility of a dexterity-enhancing handheld robot for endoscopic neurosurgery: an in-vivo animal study (IDEAL stage 0). npj Robot 4, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00068-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00068-7