Abstract

Mental health is sometimes understood as merely the absence of mental illness and sometimes more expansively as inclusive of a broader and more complete mental well-being. We present conceptual, empirical, and causal evidence for a distinction between the absence of mental illness and positive mental well-being. We discuss the implications for assessment, national tracking, research, policy, and mental healthcare. We argue for a greater clinical, policy, and public health attentiveness to positive mental well-being, to supplement work already being done on the treatment and prevention of mental illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world expends considerable resources on important treatment and prevention efforts for mental illness1. While such resources and attention for mental health still considerably lag far behind that for physical health, important progress has been made over the past decades1. Interest in positive aspects of mental well-being has also been increasing over the past years in diverse sectors ranging from psychology, psychiatry, and public health to economics and policy2,3,4,5,6. The resources and attention devoted to positive mental well-being, within psychiatry, say, however, arguably still lag considerably behind that which is given to mental illness7. Part of the reason for this is almost certainly constraints on clinician time. However, other reasons might include that policy-makers and healthcare professionals see addressing mental illness itself as essentially equivalent to the promotion of mental well-being, or as effectively encompassing the whole of their responsibilities regarding mental health. Even when a distinction is granted between the treatment or prevention of mental illness and the promotion of positive mental well-being, the former is often viewed as the priority, and the latter sometimes consequently neglected.

In this commentary, we will argue that while the treatment and prevention of mental illness is rightly given an important place in healthcare and policy efforts, this is not sufficient for promoting mental well-being and that advancing positive mental well-being promotion efforts is not only of value in itself, but also may be preventive or even curative for mental illness, and potentially cost-effective8,9. In what follows, we begin with some description of the concepts and terminology that are often at play in such discussions, including what is sometimes taken as a two-dimensional dual-continua model of mental health and mental illness10. We will then further present conceptual and also empirical descriptive and causal arguments for the relevance of distinctions between the absence of mental illness versus positive mental well-being, drawing on a range of different sources, including the recent Global Flourishing Study11,12,13,14. Finally, we conclude with some discussion of the implications of such distinctions for assessment, national tracking, research, policy, and mental healthcare.

Well-Being, mental illness, and mental health concepts and terminology

While mental health and mental illness are often seen as lying on two ends of a single spectrum, both conceptual and empirical work challenge the adequacy of this understanding of mental health. In an influential paper, Keyes10 proposed a “dual continua” model wherein both mental health and mental illness (for which we provide more precise definitions below) were each seen as their own continuum, so that in principle someone might be relatively low on mental illness, but also relatively low on positive mental health/well-being, or alternatively relatively high both on mental illness and on mental health. Keyes’ earlier work15 had empirically documented at least modest proportions of the US population in each of these two categories (in addition to many more who were classified as high-mental-illness-low-mental-health or low-mental-illness-high-mental-health). This dual continua conceptualization has been embraced by others16,17,18,19. While this expanded conceptualization is useful, it also is oversimplified since, even within the mental health and mental illness continua, each of these supposed continua is itself multidimensional19. Just as mental illness is not unitary but might be further differentiated into anxiety, depression, various trauma disorders, various personality disorders, and so forth, so also positive mental health is not unitary, but arguably consists of a diverse range of positive aspects of mental health such as happiness, meaning, cognitive and affective functioning, various character strengths, etc.16,19,20,21.

This complexity gives rise to ambiguities in the use of the term “mental health.” Sometimes the term “mental health” is employed to simply denote the absence of mental illness. At other times, it might be used to include not only the absence of mental illness, but also positive states of mental well-being. The World Health Organization’s definition of health22 that “Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” suggests this meaning of the term.

We would argue that, like the very word “health” itself, so also “mental health” has both a broader and a narrower meaning. The broader sense might be taken as effectively synonymous with “mental well-being” and understood comprehensively as “a state in which all aspects of a person’s mental life are good”19, where “mental life” is understood as a person’s thoughts, emotions, and other phenomena pertaining to the mind. In contrast, the narrower sense of “mental health” might be understood simply as the absence of mental illness. Both senses of the term are used in ordinary language. Because of the ambiguity around the use of “mental health” and the further complexities introduced by a dual continua model, greater precision in terminology is desirable. We will thus put forward a series of definitions, as we use them in this Perspective, acknowledging that others may use and define terms differently. We will focus principally on “mental illness” and “positive mental well-being,” since the distinctions between these two are the focus of the Perspective. However, we situate these two central terms among other related concepts. Even if others employ alternative definitions of the terms, it is nevertheless important to recognize that there are different concepts at play and that the distinctions are relevant. We believe that our definitions help make these distinctions clear. The definitions here are adapted from VanderWeele and Lomas23, Lomas et al.24, VanderWeele25, and the DSM-5-TR cf.26, and a summary glossary is also provided in Box 1.

As above, we take “mental health” in the broad sense to be synonymous with “mental well-being” and defined as “the relative attainment of a state in which all aspects of a person’s mental life are good.” We take “mental health” in the narrow sense as “the absence of mental illness,” and we turn to definitions of mental illness below. While the conceptual coverage of mental well-being, or mental health in the broad sense, is expansive, it is important to note that even this does not encompass all aspects of well-being. It does not explicitly include the physical or social dimensions, for example, within the WHO definition of health. In other work23, cf.24, we have defined well-being as the relative attainment of “a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good, as they pertain to that individual,” and “flourishing” as the even yet broader notion of the relative attainment of “a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good, including the contexts in which that person lives”23,27. Understood thus, well-being is broader than mental well-being because well-being would also include, for example, a person’s physical health. Moreover, flourishing is broader than well-being because flourishing would also include the contexts and communities in which a person lives. Thus, flourishing encompasses individual well-being, which itself encompasses mental well-being. The relations of these concepts are depicted in Fig. 1. Mental well-being thus pertains not to all aspects of a person’s life, but rather to all aspects of a person’s mental life.

Mental well-being includes not only the absence of mental illness, and of negative mental states (e.g., extensive sadness), but also the presence of positive mental states. We thus use “positive mental well-being” or “positive mental health” (understood in a broad sense) to denote “positive aspects of mental well-being, without reference to the presence or absence of the negative aspects.” Such positive aspects of mental health or mental well-being include happiness, a sense of meaning and purpose, good cognitive functioning, memory, knowledge, etc. Again, mental well-being in its broadest sense includes “all aspects of a person’s mental life.” With regard to negative mental states, “mental ill-being” (or “mental ill-health” in a broad sense), we define as “those aspects of a person’s mental life that are not good”. At the more narrow level, the formal psychiatric definition of a “mental disorder” has evolved over time26, but, as defined in the DSM-5-TR, might be taken as, “a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning.” Some will use the term “mental illness” synonymously with “mental disorder” but others use it to cover the whole range of disorders and also of various sub-clinical states, and thus, borrowing the DSM-5-TR language, we propose for “mental illness” the definition, “aspects of a person’s mental life that are not good that reflect a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning”. It is arguably the absence of such mental illness that constitutes “mental health” in its narrow sense. The definitions here will be helpful in clarifying the subsequent discussion concerning the conceptual, descriptive, and causal distinctions between mental illness on the one hand and positive mental well-being on the other.

Distinctions between the absence of mental illness versus positive mental well-being

With the understanding above, it becomes clear that the study, tracking, and treatment and prevention efforts, directed towards mental illness, are not fully adequate for the promotion of positive mental well-being, cf.7. As suggested above, this is clear first on conceptual grounds. Knowing that an individual does not have a mental illness does not tell us how happy that person is, or whether they have a sense of meaning in life. To have a fuller understanding of mental well-being and the factors that may increase its prevalence in the population, we need to assess positive mental well-being itself, and not just the presence or absence of mental illness.

The distinctions between positive mental well-being and the absence of mental illness are also separable on descriptive empirical grounds. Cummins et al.28, for example, report a perhaps surprisingly high proportion of individuals who are clinically depressed but nevertheless report reasonably high levels of life satisfaction. While extreme depression precludes perfect life satisfaction, moderate degrees of depression and satisfaction can be simultaneously present. Keyes15 also reports, in a sample of 3032 American adults, that of the 511 who had experienced a major depressive episode, 27 had high positive mental health, 259 had moderate positive mental health, and 143 were considered to lack positive mental health. Such descriptive distinctions between, say, depression or anxiety on the one hand and aspects of positive well-being, such as life satisfaction or meaning and purpose, are likewise present in the Global Flourishing Study11. This includes evidence ranging from the differing orderings of the means of these different assessments across countries, to the proportions reporting higher levels of both mental ill-health and positive well-being12,13,29. Similar conclusions are likewise drawn in empirical factor analyses, suggesting two distinct relevant factors for mental illness and positive mental health30; a review of numerous descriptive studies31 summarizes: “it was possible for individuals to report high levels of positive mental health despite mental illness”.

The distinction between absence of mental illness and positive mental well-being can also be seen through longitudinal associations and potential causal relations between these experiences. Several studies indicate that positive mental well-being is longitudinally associated with less mental illness, independent of baseline mental illness. For example, Wood and Joseph32 discuss evidence as to how measures of positive mental well-being independently predict lower odds of depression, controlling for baseline depression. Likewise, in longitudinal analyses, Santini et al.33, restricting to samples without mental disorder/depression at baseline, and controlling for numerous other variables, indicate a 69–90% reduction in the risk of onset of mental disorder or depression for those scoring high on the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale. Similarly again, in a random-intercept cross-lagged panel model using data every 2 years and 16 years of total follow-up, Joshanloo and Blasco-Belled18 examine reciprocal relationships over time between depressive symptoms and components of positive mental well-being, and found evidence for effects of both life satisfaction and eudaimonic well-being on reducing subsequent depressive symptoms, controlling for earlier levels of depressive symptoms. While it is possible, when mental illness is treated as a binary category, that lower levels of mental well-being may simply be a proxy for incipient mood disorders, the fact that similar results hold even when e.g., continuous depressive symptoms are used suggests once again independent relevance of positive mental well-being. Other longitudinal studies, and reviews of such studies, likewise support similar conclusions34,35,36. And conversely, mental illness is longitudinally associated with lower subsequent positive mental well-being, even controlling for those levels at baseline18. Yet further evidence comes from randomized trials indicating larger effects on both positive and negative states for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) followed by well-being therapy when compared to CBT alone, even when employing the same number of sessions37. These various results suggest distinctions between positive mental well-being and the absence of mental illness, but suggest also, as discussed in the next section, that promoting positive mental well-being is a potential prevention pathway for mental illness (and, perhaps more obviously, the treatment of mental illness as a pathway to promoting positive mental well-being).

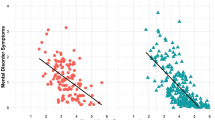

The correlates of mental illness and positive mental health can also differ38,39. While criticisms might be made of their “mediational” interpretation, Kinderman et al.40, report anxiety and depression being more strongly related to negative life events, whereas low levels of subjective well-being were more strongly related to material deprivation and social isolation. Similarly, differential patterns with demographics were found comparing depression and anxiety versus positive mental well-being in the Global Flourishing Study: for example, in demographic analyses, while there is variation across countries, religious service attendance was far more strongly related to life satisfaction than to depression, and conversely, age was more strongly related to depression than to life satisfaction12,29.

In a perhaps more complex manner, the distinctions between the absence of mental illness versus positive mental well-being can potentially be seen in the interventions typically employed in the different sectors (and in corresponding academic literature), aiming at the treatment of mental illness versus the promotion of positive mental well-being. Treatment strategies concerning mental illness include pharmacological agents, CBT, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), psychodynamic approaches, or other forms of psychological therapy and counseling41,42,43,44,45. In contrast, the interventions most often promoted and discussed for improving positive mental well-being include gratitude activities, acts of kindness exercises, imagining one’s best possible self, the use of character strengths, meditation and mindfulness, fostering positive spiritual coping, etc.,46,47,48,49,50. It should, however, be acknowledged that treatment for mental illness can, of course, also focus on the promotion of positive mental well-being, the achievement of goals, etc.16,37,48,51. Moreover, given the evidence for reciprocal causal effects of mental illness on positive mental well-being, this point concerning interventions is arguably more complicated, and we will comment upon this further in the discussion of the implications of this work, to which we now turn.

Implications for mental health and mental well-being

There are arguably a number of important implications that follow from these conceptual, empirical, and causal distinctions concerning mental illness and positive mental well-being. First, as noted above, conceptually, the absence of mental illness does not necessarily tell us about the extent of positive mental well-being, and empirically, there are individuals with mental illness who also have relatively high levels of positive mental well-being, and conversely, individuals without mental illness who have lower levels of positive mental well-being15,28,31. This has implications for community assessment, monitoring, and tracking. Indeed, important insights into mental illness have emerged from more systematic data collecting, monitoring, and tracking efforts. As a result of these efforts, we are becoming more aware of who needs help, how rates of e.g., anxiety, depression, or suicide are distributed across demographic groups, and how this has changed over time. This has perhaps recently been most evident in tracking the rising rates of mental illness among youth52,53. While tracking multiple domains can be challenging, such assessment efforts also alter the attention paid to these matters and the resources devoted to addressing those with needs. However, the distinctions between mental illness and positive mental well-being imply that monitoring and tracking conditions like depression and anxiety alone are insufficient. We need to monitor, track, and collect data on positive mental well-being also54. Just as such efforts have led to both greater understanding and also greater policy and intervention efforts concerning mental illness, so such data collection would enable a better understanding of and promotion of positive mental well-being also. Such data collection efforts should not be restricted to a single dimension of mental well-being, such as life satisfaction, but should extend to mental well-being broadly, for example, including, but not limited to, meaning and purpose, character, cognition and knowledge, coping, and so forth. Such data collection could also extend to other aspects of flourishing as well. Mental well-being and flourishing are multidimensional, not unidimensional, and if we are to adequately promote well-being, we need an understanding of its numerous different facets55. Patterns across countries can vary across different aspects of mental well-being. For example, life evaluation is often higher in richer developed countries, but meaning and purpose are often higher in poorer developing countries11,56. Such findings make clear the need for nuance. If we are to promote positive mental well-being, or even more broadly, flourishing, we must begin better efforts at monitoring and tracking at local, national, and international scales, and within workplaces, clinics, schools, communities, and countries. What we measure shapes what we study, what we discuss, what we know, what we aim for, and policies put in place to achieve those aims. We need assessment not just for mental illness but also for positive mental well-being.

Second and relatedly, we need more rigorous academic study of positive mental well-being. Much has been learned from the positive psychology movement. However, much of that knowledge has been obtained primarily within Western societies and relatively homogenous samples within these geographies; much of our understanding of positive mental well-being derives from experiments with college students and other convenience samples and from shorter-term studies, rather than, say, national data collection efforts or with large, longer-term cohorts. We have argued elsewhere for the creation of a “positive epidemiology”57 to mirror in some sense the positive psychology movement but carried out with large cohort studies, representative samples, and contemporary methods intended to provide evidence concerning causation, all to effectively study the distribution and determinants of positive well-being, rather than disease. The Global Flourishing Study11 itself was essentially intended as a step in that direction. However, what we know globally about positive well-being still pales in comparison to our knowledge of the distribution and determinants of mental illness. Moreover, the Global Flourishing Study itself has numerous limitations in that while it has broad conceptual coverage in terms of the constructs embedded within the study, and broad geographical coverage, the measurement of the various aspects of each positive mental well-being construct often consists of only a single item11,14. There is a need for more focused studies in order to enrich and supplement this work with multi-item assessments. Moreover, while the Global Flourishing Study consists of 22 countries covering all six populated continents, with nationally representative samples constituting about half of the world’s population, having just 22 countries in the study leaves over 170 countries outside the study’s scope. Additional research, ideally with large nationally representative longitudinal cohort studies, could, and arguably should, be carried out within each country with greater emphasis given to each country’s specific cultural dynamics, priorities, and principal understandings of well-being, along with attention to matters of translation and interpretation54,58. A more rigorous study of positive mental well-being and of flourishing will empower our capacity to promote it, and to do so in a culturally tailored and sensitive manner.

Third, policy efforts should likewise be expanded to consider not only physical and mental illness, but positive mental well-being also. Policy interest in the promotion of well-being has been increasing with numerous proposals and frameworks having now been put forward3,4,5,6,59. Undoubtedly, thinking in this area will continue to develop, and a full analysis of how the promotion of positive well-being should be incorporated within policy and be related to other policy priorities is beyond the scope of this commentary. Nevertheless, at the very least, the data collection, monitoring, and tracking of positive well-being discussed above should be part of each nation’s efforts60, and also a part of the data collection of intergovernmental agencies such as the World Health Organization. When feasible, further resources could be devoted, as noted above, to the creation of national cohorts for the within-country study of positive mental well-being and flourishing as discussed above. Community campaign efforts could also be made to distribute self-directed well-being promotion activities and interventions such as gratitude, acts of kindness, imagining one’s best possible self, savoring, forgiveness, use of character strengths, and others46,47,50. The distribution of these nearly costless interventions in neighborhoods, schools, religious communities, workplaces, clinics, and other community settings could go a long way in the promotion of positive mental well-being. Such efforts have been underway recently within schools61, and more could be done to increase awareness and outreach within clinical, neighborhood, and other settings as well. Other policy efforts to improve mental well-being might focus on the community level to foster better work conditions, work-life balance, family life, and community participation62,63,64,65,66. As noted in the evidence above, such efforts to promote positive mental well-being with individual or community-level interventions could potentially have a powerful role in preventing mental illness as well. Further financial resources and additional training programs could also potentially be directed towards the promotion of positive mental well-being within the formal mental health care system itself49.

This brings us to our fourth and final proposal: the inclusion of well-being promotion resources within formal mental healthcare. We realize this recommendation may be more contentious than others. There can be legitimate disagreement with regard to the role of well-being promotion within psychiatry. While a “positive clinical psychology”67,68 and even a “positive psychiatry”2,69,70 movement has emerged, at present this constitutes only a very small proportion of the work, care, and research that takes place within psychiatry. It also raises difficult questions as to the proper scope of psychiatry. Many would view an expansion of psychiatry to all of positive mental well-being, or all of flourishing, as overstepping the bounds of psychiatric practice and of the discipline’s core expertise, and of raising challenging issues concerning potentially divergent values of the psychiatrist and the patient. However, limiting psychiatry’s scope to only addressing mental illness may be viewed by others as being too restrictive, given both the potential to help patients in numerous aspects of life and also the potential relations between mental illness and other aspects of a person’s physical, psychological, social, and even spiritual life. An intermediate position might be to take the purview of psychiatry to be the promotion, maintenance and restoration of mental health (in the narrow sense, as it pertains to the absence of mental illness), along with those aspects of flourishing concerning which the patient and clinician together agree through dialog to address71, cf.72. Such a position would take, at a minimum, as the object of psychiatric care, mental illness in a narrow sense, and might allow the psychiatrist to restrict his or her attention to this narrower conception of mental health. However, it would also allow for the joint pursuit, for those psychiatrists and those patients who desired it, of other aspects of the patient’s flourishing. Such a position admittedly introduces potential heterogeneity in the scope of psychiatry across practices. However, it allows flexibility for the aims of specific psychiatrists or practices to be considerably more expansive and to address issues of positive mental well-being. This could include, in clinical settings, assessments of positive mental well-being, the distribution of positive mental well-being interventions, and discussions concerning patient priorities, goals, and approaches with regard to various aspects of positive mental well-being.

A variety of other considerations suggest that greater attentiveness to positive mental well-being may be of benefit within psychiatry and formal mental healthcare. As noted above, promotion of positive mental well-being may aid the prevention of, or recovery from, mental illness32,33. Relatedly, such a broadening of scope might also expand the set of resources being considered within psychiatry46,47,50,73. As an example, recent large randomized trials of self-directed forgiveness workbook interventions have indicated effects not only on forgiveness and mental well-being, but also on reducing depression and anxiety across a diverse range of cultures and countries74. A psychiatrist, in providing routine care for depression or anxiety, could easily inquire if the patient is also struggling with anger. The forgiveness workbook resources could be mentioned and distributed to those who would like to forgive but are having trouble doing so. Such an expansion of psychiatric care resources could be accomplished with very low cost, with the potential to help many, possibly aiding also in the primary focus of addressing mental illness75. As noted above, numerous other such interventions are also now similarly available47,76,77. Further study of the timing of interventions and persistence of effects is necessary, but the effects of at least some of these interventions seem to persist for a number of months, if not longer78,79. A focus on the treatment of mental illness has perhaps led to a neglect of resources that are available for the promotion of positive mental well-being, and likewise a neglect of the role these resources might also have in the prevention and treatment of mental illness80.

It may, moreover, ultimately be the case that certain aspects of mental illness in fact have their root cause in deeper existential matters concerning relationships; meaning, purpose, and calling; questions of character and decision-making; or spiritual concerns69,70,81,82,83. Personality disorders might be alleviated by the cultivation of certain virtues, such as conscientious, and anxiety disorders by the cultivation of equanimity49,69,83,84. It may be that certain aspects of mental illness are perhaps intractable without addressing more positive aspects of mental well-being also.

Conversely, a greater attentiveness to positive mental well-being in psychiatry might facilitate bringing the traditional psychotherapies of formal mental healthcare into the broader community. Some research indicates that therapies, such as ACT, used to treat mental illness, can also have beneficial effects on positive psychological states as well45. The dissemination of ACT and CBT therapies to community settings might advance not only the treatment and prevention of mental illness but also various aspects of positive mental well-being. Widespread community dissemination of such resources could likewise be facilitated via book-based and or app/mobile-based therapy resources43,77,85,86,87. These could supplement traditional and effective community-based efforts at promoting mental health literacy44. We are certainly not calling for a neglect of more traditional treatments of psychiatric symptoms, but rather for the use of additional complementary approaches. While discerning the proper balance between attentiveness to mental illness versus positive mental well-being is not straightforward, psychiatry and formal mental health care would, for all of these reasons, benefit from at least somewhat greater attention to the latter than is the case at present.

Conclusions

In this commentary, we have argued for conceptual, empirical, and causal distinctions between the absence of mental illness and the presence of positive mental well-being. The dual continua model of somewhat independent positive and negative dimensions is an oversimplification of a complex multidimensional reality10,17,19, but its basic insight is correct. We need to be attentive both to mental illness and to positive mental well-being. While the relative weight given to address the positive versus negative aspects of mental health and well-being is a difficult matter, and the right way forward is likely to vary by context and treatment stage88, neither side should be neglected. Both are of value and importance in their own right, and there is compelling evidence that each causally contributes to the other. While it may sometimes seem that the priority of one over the other is a zero-sum game, it may be the case that a greater emphasis on positive mental well-being, or flourishing more broadly, could in fact increase interest in, and funding and resources for, both the positive and negative aspects of mental health. A focus on positive mental well-being, beyond mental illness, might also help reduce the stigma sometimes associated with the latter, perhaps especially within developing countries89,90.

In the present state of affairs, however, matters of positive mental well-being have arguably too often been neglected. It is possible that the very ambiguity of the term “mental health,” as sometimes being used for the “absence of mental illness” and sometimes for all of “mental well-being,” and the logical and rhetorical slippage that this ambiguity sometimes facilitates, has in part been responsible for some of this neglect. The conceptual, empirical, and causal distinctions between mental illness and positive mental well-being, however, make clear the need to be attentive to both. Both should be assessed in our data collection, monitoring, and tracking efforts. Both should be studied rigorously in large longitudinal samples to have a better understanding of the distribution and determinants of mental illness and of positive mental well-being, and how such distributions and determinants differ from each other. This should be done in a holistic manner with the understanding that both mental illness and positive mental well-being are themselves highly multidimensional91. The research from the Global Flourishing Study constitutes an advance in this regard11,12,13,14, but much more remains to be done. Furthermore, both positive and negative aspects of mental well-being should be goals in policy efforts and should be made policy priorities. And both should be pursued as important goals within formal mental healthcare. While much would need to change to give positive mental well-being its due weight, and some of the relevant considerations are not straightforward, we will better move towards a more flourishing society if we do not neglect either the positive or the negative side of mental health and well-being.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

World Health Organization. Mental Health ATLAS. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036703 (2020).

Jeste, D. V., Palmer, B. W., Rettew, D. C. & Boardman, S. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, 14729 (2015).

Adler, M. D. & Fleurbaey, M. The Oxford Handbook of Well-Being and Public Policy (eds Adler, M. D. & Fleurbaey, M.) (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Plough, A. L. Well-Being: Expanding the Definition of Progress: Insights from Practitioners, Researchers, and Innovators from Around the Globe (ed. Plough, A. L.) (Oxford Univ. Press, 2020).

Trudel-Fitzgerald, C. et al. Psychological well-being as part of the public health debate? Insight into dimensions, interventions, and policy. BMC Public Health 19, 1–11 (2019).

Layard, R. & De Neve, J. E. Wellbeing (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

Bohlmeijer, E. & Westerhof, G. The model for sustainable mental health: future directions for integrating positive psychology into mental health care. Front. Psychol. 12, 747999 (2021).

Slade, M. Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Serv. Res. 10, 1–14 (2010).

McDaid, D., Park, A. L. & Wahlbeck, K. The economic case for the prevention of mental illness. Annu. Rev. Public Health 40, 373–389 (2019).

Keyes, C. L. M. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73, 539–548 (2005).

VanderWeele, T. J. et al. The global flourishing study: study profile and initial results on flourishing. Nat. Ment. Health 3, 636–653 (2025).

Bradshaw, M. et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety: demographic variations across 22 Global Flourishing Study countries. Commun. Med. 6, 100 (2026).

Okafor, C. N. et al. A cross-national analysis of demographic variation in self-rated mental health across 22 countries. Commun. Med. 5, 320 (2025).

Lomas, T. et al. The development of the Global Flourishing Study questionnaire: charting the evolution of a new 109-item inventory of human flourishing. BMC Glob. Public Health 3, 30 (2025).

Keyes, C. L. M. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 43, 207–222 (2002).

Cloninger, C. R. The science of well-being: an integrated approach to mental health and its disorders. World Psychiatry 5, 71–76 (2006).

van Agteren, J. & Iasiello, M. Advancing our understanding of mental wellbeing and mental health: the call to embrace complexity over simplification. Aust. Psychol. 55, 307–316 (2020).

Joshanloo, M. & Blasco-Belled, A. Reciprocal associations between depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, and eudaimonic well-being in older adults over a 16-year period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 2374 (2023).

Lomas, T. & VanderWeele, T. J. The mental illness-health matrix and the mental state space matrix: complementary meta-conceptual frameworks for evaluating psychological states. J. Clin. Psychol. 79, 1902–1920 (2023).

Reynolds, C. F. III & Blazer, D. G. Toward a multidimensional perspective on wisdom and health—an analogy with depression intervention and neurobiological research. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 895–896 (2020).

Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E. P. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification (American Psychological Association, 2004).

World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization, adopted by the International Health Conference (1946).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Lomas, T. Terminology and the well-being literature. Affect. Sci. 4, 36–40 (2023).

Lomas, T., Pawelski, J. O. & VanderWeele, T. J. Flourishing as ‘sustainable well-being’: balance and harmony within and across people, ecosystems, and time. J. Posit. Psychol. 20, 203–218 (2025).

VanderWeele, T. J. Flourishing and the scope of medicine and public health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 78, 466–470 (2024).

Vacca, M. et al. Definitions of “mental disorder” from DSM-III to DSM-5. Behav. Sci. 15, 830 (2025).

VanderWeele, T. J. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8148–8156 (2017).

Cummins, R. A., Lau, A. & Davern, M. Homeostatic mechanisms and subjective wellbeing. In Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Studies (eds. Land, K. C., Michalos, A. C. & Sirgy, M. J.) 115–138 (Springer, 2007).

Lomas, T. et al. Exploring associations of three evaluative wellbeing measures (Cantril's ladder, life satisfaction, happiness) with 15 childhood and demographic factors across 22 countries. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35777-y (2026).

Lamers, S. M., Westerhof, G. J., Bohlmeijer, E. T., ten Klooster, P. M. & Keyes, C. L. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF). J. Clin. Psychol. 67, 99–110 (2011).

Iasiello, M. & van Agteren, J. Mental health and/or mental illness: a scoping review of the evidence and implications of the dual-continua model of mental health. Evid. Base 1, 1–45 (2020).

Wood, A. M. & Joseph, S. The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: A ten year cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 122, 213–217 (2010).

Santini, Z. I. et al. Higher levels of mental wellbeing predict lower risk of common mental disorders in the Danish general population. Ment. Health Prev. 26, 200233 (2022).

Ruini, C. & Cesetti, G. Spotlight on eudaimonia and depression: a systematic review of the literature over the past 5 years. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 12, 767–792 (2019).

Iasiello, M., van Agteren, J., Keyes, C. L. M. & Cochrane, E. M. Positive mental health as a predictor of recovery from mental illness. J. Affect. Disord. 251, 227–230 (2019).

Margraf, J., Teismann, T. & Brailovskaia, J. Predictive power of positive mental health: a scoping review. J. Happiness Stud. 25, 81 (2024).

Fava, G. A. et al. Well-being therapy of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychother. Psychosom. 74, 26–30 (2004).

Ryff, C. D. et al. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates?. Psychother. Psychosom. 75, 85–95 (2006).

Steptoe, A., Demakakos, P., de Oliveira, C. & Wardle, J. Distinctive biological correlates of positive psychological well-being in older men and women. Psychosom. Med. 74, 501–508 (2012).

Kinderman, P. et al. Causal and mediating factors for anxiety, depression and well-being. Br. J. Psychiatry 206, 456–460 (2015).

Patel, V. et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370, 991–1005 (2007).

Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I. A., Karyotaki, E., Reijnders, M. & Huibers, M. J. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry 15, 245–258 (2016).

Etzelmueller, A. et al. Effects of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in routine care for adults in treatment for depression and anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e18100 (2020).

de Pablo, G. S. et al. Universal and selective interventions to promote good mental health in young people: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 41, 28–39 (2020).

Kraiss, J., Redelinghuys, K. & Weiss, L. A. The effects of psychological interventions on well-being measured with the Mental Health Continuum: a meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 23, 3655–3689 (2022).

Bolier, L. et al. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 13, 119 (2013).

VanderWeele, T. J. Activities for flourishing: an evidence-based guide. J. Posit. Psychol. Wellbeing 4, 79–91 (2020).

de Abreu Costa, M. & Moreira-Almeida, A. Religion-adapted cognitive behavioral therapy: A review and description of techniques. J. Relig. Health 61, 443–466 (2022).

Goodman, D. et al. The virtue of virtue in psychotherapy: contextualizing and situating the conversation. In Routledge International Handbook of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology (eds. Slife, B., Yanchar, S. & Richardson, F.) (Taylor & Francis, 2022).

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., de Jong, J. & Bohlmeijer, E. The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Happiness Stud. 21, 357–390 (2020).

Chase, J. A. et al. Values are not just goals: online ACT-based values training adds to goal setting in improving undergraduate college student performance. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2, 79–84 (2013).

Blanchflower, D. G., Bryson, A., Lepinteur, A. & Piper, A. Further evidence on the global decline in the mental health of the young. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 32500 (2024).

Haidt, J., Rausch, Z. & Twenge, J. Social media and mental health: a collaborative review. Unpublished manuscript, New York University (2024).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Johnson, B. R. Why we need to measure people’s well-being—lessons from a global survey. Nature 641, 34–36 (2025).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Johnson, B. R. Flourishing versus life satisfaction: Is well-being one dimensional?. Nat. Hum. Behav. 9, 857–863 (2025).

Oishi, S. & Diener, E. Residents of poor nations have a greater sense of meaning in life than residents of wealthy nations. Psychol. Sci. 25, 422–430 (2014).

VanderWeele, T. J. et al. Positive epidemiology?. Epidemiology 31, 189–193 (2020).

Lomas, T. et al. Insights from the first global survey of balance and harmony. In World Happiness Report 2022, Ch. 6, 127–154 (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2022).

Murthy, V. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2023).

Graham, C., Laffan, K. & Pinto, S. Well-being in metrics and policy. Science 362, 287–288 (2018).

Kristjánsson, K. & VanderWeele, T. J. The proper scope of education for flourishing. J. Philos. Educ. 59, 634–650 (2025).

Sheridan, S. M., Warnes, E. D., Cowan, R. J., Schemm, A. V. & Clarke, B. L. Family-centered positive psychology: Focusing on strengths to build student success. Psychol. Sch. 41, 7–17 (2004).

Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior: developing and managing psychological strengths. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 16, 57–72 (2002).

Fox, K. E. et al. Organisational- and group-level workplace interventions and their effect on multiple domains of worker well-being: a systematic review. Work Stress 36, 30–59 (2022).

Case, B. et al. Reconnecting our communities: Social flourishing on the far side of “our epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation”. Int. J. Wellbeing 15, 4 (2025).

Kirkbride, J. B. et al. The social determinants of mental health and disorder: evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry 23, 58–75 (2024).

Seligman, M. E. P. & Peterson, C. Positive clinical psychology. In Aspinwall, L. G. & Staudinger, U. M. (eds) A Psychology of Human Strengths: Fundamental Questions and Future Directions for a Positive Psychology 305–317 (American Psychological Association, 2003).

Wood, A. M. & Tarrier, N. Positive clinical psychology: a new vision and strategy for integrated research and practice. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 819–829 (2010).

Jankowski, P. J. et al. Virtue, flourishing, and positive psychology in psychotherapy: an overview and research prospectus. Psychother 57, 291–309 (2020).

Mosqueiro, B. P., Moreira-Almeida, A., Moffic, H. S. & Jeste, D. V. Spirituality: Relationship with religion, health, wisdom, and positive psychiatry. In Eastern Religions, Spirituality, and Psychiatry: An Expansive Perspective on Mental Health and Illness 75–86 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024).

VanderWeele, T. J. A Theology of Health: Wholeness and Human Flourishing. (University of Notre Dame Press, 2024).

Jankowski, P. J. & Goodman, D. M. The ethics of attending to virtues in psychotherapy. In Addressing Suffering and Flourishing in Psychotherapy (eds Sandage, S. J. & Owen, J.) (American Psychological Association).

Goodman, D. The McDonaldization of psychotherapy: processed foods, processed therapies, and economic class. Theory Psychol. 26, 77–95 (2015).

Ho, M. Y. et al. International REACH forgiveness intervention: a multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ Public Health 2, e000072 (2024).

VanderWeele, T. J. Is forgiveness a public health issue?. Am. J. Public Health 108, 189–190 (2018).

Shute, R. School-based mindfulness interventions. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education (Oxford Univ. Press, 2023). Retrieved 31 Jul. 2025, from https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-979.

Anderson, L. et al. Self-help books for depression: how can practitioners and patients make the right choice?. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 55, 387–392 (2005).

Seligman, M. E., Steen, T. A., Park, N. & Peterson, C. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 60, 410–421 (2005).

Davis, D. E. et al. Thankful for the little things: a meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. J. Couns. Psychol. 63, 20–31 (2016).

Sampson, L., Kubzansky, L. D. & Koenen, K. C. The missing piece: a population health perspective to address the US mental health crisis. Daedalus 152, 24–44 (2023).

VanderWeele, T. J., McNeely, E. & Koh, H. K. Reimagining health—flourishing. JAMA 321, 1667–1668 (2019).

Moreira-Almeida, A., Sharma, A., van Rensburg, B. J., Verhagen, P. J. & Cook, C. C. H. WPA position statement on spirituality and religion in psychiatry. World Psychiatry 15, 87–88 (2016).

Peteet, J. R. The Virtues in Psychiatric Practice. (Oxford Univ. Press, 2021).

Griffith, J. L. & Gaby, L. Brief psychotherapy at the bedside: countering demoralization from medical illness. Psychosomatics 46, 109–116 (2005).

Hecker, J. E., Loses, M. C., Fritzler, B. K. & Fink, C. M. Self-directed versus therapist-directed cognitive behavioral treatment for panic disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 10, 253–265 (1996).

Carlbring, P., Westling, B. E. & Andersson, G. A review of published self-help books for panic disorder. Scand. J. Behav. Ther. 29, 5–13 (2000).

Haug, T., Nordgreen, T., Öst, L. G. & Havik, O. E. Self-help treatment of anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of effects and potential moderators. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 425–445 (2012).

Fava, G. A., Cosci, F., Guidi, J. & Tomba, E. Well-being therapy in depression: new insights into the role of psychological well-being in the clinical process. Depress Anxiety 34, 801–808 (2017).

Menke, R. & Flynn, H. Relationships between stigma, depression, and treatment in white and African American primary care patients. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 197, 407–411 (2009).

Wainberg, M. L. et al. Challenges and opportunities in global mental health: a research-to-practice perspective. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 19, 28 (2017).

Lee, M. T., Kubzansky, L. D. & VanderWeele, T. J. Measuring Well-Being: Interdisciplinary Perspectives from the Social Sciences and the Humanities (eds Lee, M. T., Kubzansky, L. D. & VanderWeele, T. J.) (Oxford Univ. Press, 2021).

Acknowledgements

The Global Flourishing Study was supported by funding from the John Templeton Foundation (grant no. 61665, B.R.J., T.J.V.), Templeton Religion Trust (no. 1308, B.R.J., T.J.V.), Templeton World Charity Foundation (no. 0605, B.R.J., T.J.V.), Well-Being for Planet Earth Foundation, Fetzer Institute (no. 4354, B.R.J., T.J.V.), Well Being Trust, Paul L. Foster Family Foundation and the David and Carol Myers Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J.V. wrote the original draft. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved of the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Tyler VanderWeele reports consulting fees from Gloo Inc., along with shared revenue received by Harvard University in its license agreement with Gloo according to the University IP policy. The remaining authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

VanderWeele, T.J., Johnson, B.R., Bradshaw, M. et al. Mental illness, mental health, and mental well-being. npj Mental Health Res 5, 11 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-026-00193-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-026-00193-7