Abstract

Autistic people are less likely to benefit from currently recommended mental health treatments, but little is known about how outcomes vary across individuals. This gap makes it difficult to adapt therapies (or develop new ones) to meet diverse needs among autistic people. Here we show that autistic people receiving routine psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in English primary care mental health services followed different symptom pathways: several improved, others remained stable, whereas others experienced worsening symptoms. Our analysis used data from 7,175 autistic adults who accessed services in England between 2012 and 2019, linked with national healthcare records drawn from the MODIFY dataset. We used growth mixture models to identify five patterns of depression change and seven patterns of anxiety change and a regression model to understand how risk factors related to the type of change. Being from an ethnically minoritized background was linked to a higher likelihood of worsening anxiety compared with White participants. More difficulties with functioning in daily living—such as managing social leisure activities—were linked to poorer outcomes for severe anxiety and depression. These findings highlight the need for therapies that are culturally responsive and affirming of neurodivergent experiences. Support for daily living tasks including social leisure (attending to camouflaging and burnout) may be a helpful focus for additional neurodiversity-affirming support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Autistic people are more likely to experience a range of mental health conditions including depression and anxiety compared with nonautistic people1 and report negative experiences when they receive support for these2.

Evidence-based psychological therapies (including, for example, cognitive behavior therapy) are recommended as first-line treatments for depression and anxiety3,4,5. However, psychological interventions often require adaptation to better meet the needs of autistic service users4,5,6,7. Such adaptations to the therapy process may include environmental and sensory adjustments, communication accommodations such as use of visual materials and changes to the content of interventions (for example, psychoeducation on emotions)8,9. Coproduced research and perspectives from within the autism community increasingly emphasize that therapies should be neurodiversity-affirming, that is, prioritize autistic lived experience and champion (not pathologize) autistic ways of being (for example, refs. 10,11).

In the largest study of its kind, using a national cohort of adults receiving psychological therapies in a general adult healthcare setting, it was demonstrated that autistic people experienced lower rates of improvement and recovery than a matched nonautistic comparison group12. However, that study12 and those preceding it6 have not yet been able to contribute to understanding which groups of autistic people may experience better or worse depression or anxiety intervention outcomes. Characterizing such subgroups would help clarify more personalized or more thoroughly adapted intervention approaches.

Statistical modeling approaches that can identify heterogeneous patterns of symptom change offer several advantages13. Firstly, they enable an investigation of distinct trajectories of autistic people’s symptom change during psychological therapy, along with the pretreatment characteristics associated with following those trajectories. This may help inform treatment planning, including the need for adapted, augmented or different treatment if the likely trajectory shows a slow or poor treatment response. Secondly, previous studies have used a similar approach to model response to treatment in clinical samples where the majority of the service users were not autistic14,15. These identified an association between symptom trajectories and pretreatment difficulties with functioning in daily living (that is, the impact of the person’s mental health condition on their ability to function across home, work, relationships and leisure activity contexts). Greater pretreatment difficulties with functioning in daily living were associated with a lower likelihood of following an improving trajectory (decreasing symptoms and benefiting from treatment) for anxiety or depression, relative to a stable one (that is, nonresponse to treatment). It is currently unclear as to whether difficulties with functioning in daily living may affect outcomes for autistic people as they do for nonautistic people. However, given that these difficulties were previously observed to be higher for autistic people pretreatment in a general adult mental healthcare setting12 and are also a known barrier to treatment2, this warrants further investigation. The current study aims to identify trajectories of depression and anxiety symptom change for autistic people during psychological therapy, delivered as part of routine care in a nationwide general adult psychological treatment program. It also aims to identify pretreatment characteristics associated with different trajectories of treatment response. It used the MODIFY dataset, which includes national data drawn from linked National Health Service (NHS) Digital electronic healthcare records from across all healthcare regions in England16. Sessional anxiety and depression symptom scores for autistic individuals who received psychological therapy were explored using growth mixture modeling (GMM, a statistical modeling approach that can identify distinct patterns of change within heterogeneous data). Pretreatment demographic and clinical characteristics were entered into a regression model to understand their associations with the different symptom trajectories. These were: sex, age, ethnicity, employment status, use of psychotropic medication, presence of a long-term health condition, intellectual disability status, presenting problem (depression, anxiety or mixed anxiety–depression) and difficulties with functioning in daily living (total scores and individual components of home, social leisure, private leisure and close relationship functioning).

Results

Data were available for 2,512,402 individuals in the MODIFY dataset, and 11,198 had a linked autism diagnosis. After exclusion criteria were applied, a study sample of 7,175 was obtained (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for a study flow diagram). See Table 1 for the clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample.

Sex, ethnicity, employment status, primary presenting problem (depression, anxiety or mixed depression-anxiety), presence of a long-term health condition and intellectual disability were not were associated with missing anxiety or depression data points at the initial time point, but ethnicity was related to missingness by the final (eighth) time point. Data were handled as missing at random, and the relationship with ethnicity was accounted for in subsequent interpretation. The distribution of the data is reported in Supplementary Table 7, and the associations of covariates with missing data are reported in Supplementary Table 8.

Anxiety and depression trajectories

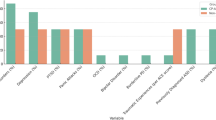

A model with five distinct depression trajectories (D1–D5; Fig. 1) and a model with seven distinct anxiety trajectories (A1–A7; Fig. 2) were selected as best fitting the data. Trajectories were interpreted using clinical score ranges (for example, mild, moderate and severe) that have been validated for the associated measures (Methods). See Tables 2 (depression) and 3 (anxiety) for mean scores by trajectory and time point. Group names and codes are in the key to Figs. 1 and 2. In the depression model, ‘moderately severe, not improving’ (D1; 39.0%) and ‘moderate, limited improvement’ (D4; 36.7%) trajectory classes accounted for the majority of the sample. One class showed rapid improvement from the ‘severe’ to the ‘minimal’ depression severity range (D2; 4.3%), whereas another showed more gradual improvement from the ‘moderately severe’ to the ‘mild’ range (D3; 18.6%). A smaller class was composed of individuals who started in the ‘moderate’ depression range but subsequently showed deterioration into the ‘moderately severe’ range (D5; 1.5%).

The depression symptoms and severity ranges were measured using the PHQ-936.

The anxiety symptoms were measured using the GAD-7 scale37.

In the anxiety model, three classes representing around 60% of the sample showed trajectories with no or minimal improvement, in each of the ‘severe’ (A1; 33.1%), ‘moderate’ (A4; 20.5%) and ‘moderate’ to ‘mild’ (A7; 6.7%) anxiety severity ranges. One class showed rapid improvement from the ‘severe’ to the ‘minimal’ severity range (A2; 4.9%), and another showed more gradual improvement from the ‘severe’ to the ‘mild’ range (A3; 18.4%). A further two classes began within the ‘moderate’ anxiety range at baseline, showing each of an improving (to ‘mild’, A5; 13.9%) or deteriorating (to ‘severe’, A6; 2.6%) path.

The trajectories obtained for anxiety were comparable to those for depression symptoms, with the addition of moderate improving and mild classes. Both models showed 4–5% of the sample could be considered early responders, making rapid gains by the third session. By this point, trajectories could be distinguished with greater confidence than at baseline, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) between the groups starting in ‘moderately severe’ and ‘severe’ ranges did not overlap by this point.

Reliable change indices

To assess whether changes in anxiety or depression scores reflected genuine improvement or deterioration, rather than random variation, reliable change indices were calculated for each trajectory class. Reliable improvement means that we can be confident that symptoms reduced beyond measurement error for the measure, whereas the more stringent criterion of reliable recovery means that an individual also passed from above a clinical range threshold for the measure into an identified ‘nonclinical’ range. Reliable deterioration is the inverse of improvement—that is, a worsening of symptoms beyond measurement error.

Reliable change indices by modal group assignment (that is, most likely class membership) are reported in full in Supplementary Table 15. When classes were considered by modal assignment, by the end of the treatment, almost all of the rapidly improving class members (D2, A2) had experienced a reliable improvement within both depression (99.7%) and anxiety (99.4%) models, with high rates (97.4%, 94.8%) of reliable recovery. By session 4, the rapidly improving depression group experienced a mean reduction of 12.45 points (double the reliable change index of six points for the measure) and the anxiety group a mean of 10.2 points (2.5 times the reliable change index of four points for the measure). Gradually improving class members (D3, A3) showed lower, but still substantial, rates of reliable improvement (88.8%, 91.7%) and moderate rates of reliable recovery (57.5%, 48.6%%) by the end of treatment. All improving classes showed low rates of reliable deterioration (between 0% and 0.38%). Conversely, moderate deteriorating groups showed high rates of reliable deterioration (62.6% and 74.6% in depression and anxiety models respectively) by the end of treatment. This suggested that by modal assignment, the patterns of reliable recovery, improvement and deterioration at the end of treatment were broadly consistent with the outcomes suggested by their mean trajectory by session 8.

Associations of baseline risk factors with trajectory class membership

As the largest groups, the not improving classes (D1 and A1) were chosen as the reference categories for depression and anxiety. Further comparisons were made using the moderate, limited improvement classes (D4 and A4) as reference categories. The moderate, deteriorating classes (D5 and A6) could not be used for this purpose owing to the small proportions of individuals following those trajectories. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI are reported in Extended Data Table 1 (depression model) and Extended Data Table 2 (anxiety model).

To summarize the associations observed between risk factors and trajectory classes:

-

For both anxiety and depression, lower pretreatment difficulties with functioning in daily living (that is, less functional difficulty) were associated with following rapidly improving trajectories from ‘moderately severe’ depression (D2) or ‘severe’ anxiety (A2) baseline ranges relative to the not improving trajectories D1 and A1 (OR (95% CI) 0.56 (0.36–0.85) for depression and 0.60 (0.44–0.81) for anxiety).

-

Lower baseline difficulties in social leisure functioning in particular were associated with rapid improvement from ‘severe’ anxiety (A2), relative to the severe, not improving anxiety class (A1) (OR (95% CI) 0.88 (0.78–0.99)).

-

Lower pretreatment difficulties with overall functioning in daily living and with social leisure functioning in particular were also associated with gradually improving trajectories from the ‘severe’ anxiety range (A3) relative to the severe, not improving anxiety class (A1) (OR (95% CI) 0.71 (0.57–0.89) for total scores and 0.85 (0.77–0.94) for social leisure). Each was also associated with an initially moderate but improving anxiety trajectory (A5) relative to the moderate, limited improvement anxiety trajectory (A4) (OR (95% CI) 0.68 (0.51–0.90) for total scores and 0.87 (0.77–0.98) for social leisure).

-

Overall, lower total difficulties with daily functioning were associated with a greater likelihood of following: all but the moderately severe, gradually improving depression trajectory (D3) compared with the moderately severe, nonimproving depression trajectory (D1); all but the moderately improving depression trajectory (D5) compared with initially moderate depression with limited improvement (D4); and any other trajectory compared with the severe, limited-improvement anxiety trajectory (A1). They were also associated with all but the moderate, deteriorating anxiety trajectory (A6) relative to moderate anxiety with limited improvement (A4).

-

The analyses above did not include employment-related difficulties in their measurement of difficulties with functioning in daily living, because not all participants were in employment. A sensitivity analysis that included employment difficulties replicated the same associations as those reported above (Supplementary Tables 16 and 17).

-

Identifying as belonging to the global majority (that is, an ethnically minoritized group in England) was associated with an increased likelihood of following a deteriorating anxiety trajectory (A6) relative to either reference class (OR (95% CI) 2.71 (1.23–5.96) versus severe anxiety with limited improvement (A1) and 4.91 (1.43–16.89) versus moderate anxiety with limited improvement (A4)) when compared with those identifying as belonging to any White ethnicity group.

-

Female sex was associated with a reduced likelihood of following a mild anxiety trajectory (A7) relative to severe, not improving anxiety (A1) (OR (95% CI) 0.54 (0.36–0.80)).

-

Older age was associated with a reduced likelihood of gradually improving depression from the ‘moderately severe’ range (D3) compared with ‘moderately severe’ depression that does not improve (D1) (OR (95% CI) 0.72 (0.56–0.92)). Conversely, older age was associated with a greater likelihood of ‘mild’ anxiety (A7) relative to ‘moderate’ anxiety that does not improve (A4) (OR (95% CI) 1.30 (1.02–1.67)).

-

Not being in employment was associated with a reduced likelihood of initially ‘severe’ and gradually improving anxiety (A3) relative to ‘severe’ anxiety that does not improve (A1) (OR (95% CI) 0.72 (0.53–0.98)).

-

Having an intellectual disability diagnosis was associated with a greater likelihood of initially ‘moderate’ and improving anxiety (A5) relative to ‘moderate’ anxiety that does not improve (A4) (OR (95% CI) 2.12 (1.03–4.35)).

-

Taking psychotropic medication was associated with an increased likelihood of following any other trajectory than ‘moderate’ depression that does not improve (D4). Supporting a potential association with higher pretreatment symptoms, taking medication was also associated with a reduced likelihood of following moderate, improving (A5) (OR (95% CI) 0.45 (0.31–0.66)) or mild (A7) anxiety (OR (95% CI) 0.67 (0.46–0.97)) trajectories relative to severe anxiety that does not improve (A1).

-

There were no associations found between having a diagnosed long-term health condition and likelihood of following any trajectory.

-

Across both depression and anxiety models, those with lower levels of initial difficulty were less likely to have a presenting problem relating to those symptoms. Having a presenting problem of anxiety or a missing presenting problem (versus depression) was associated with a greater likelihood of ‘moderate’ depression (limited improvement, D4) compared with ‘moderately severe’ depression that does not improve (D1) (OR (95% CI) 3.23 (2.23–4.67), 1.72 (1.15–2.58)). Similarly, presenting problems of anxiety or ‘mixed anxiety and depression’ (versus depression) were associated with greater odds of ‘moderate’ depression that does not improve (D4) than severe, rapidly improving depression (D1).

-

Presenting problems of anxiety, ‘mixed anxiety and depression’, or ‘missing’ (versus depression) were associated with a reduced likelihood of ‘mild’ (A7) or ‘moderate’ anxiety with limited improvement (A4) compared with ‘severe’ anxiety that does not improve (A1) (OR (95% CI) 0.16 (0.08–0.33), 0.35 (0.20–0.62), 0.58 (0.37–0.90) for A7 and 0.44 (0.30–0.65), 0.58 (0.38–0.88), 0.56 (0.37–0.84) for A4). Presenting anxiety problems were associated with a greater likelihood of following any other trajectory than moderate anxiety with limited improvement (A4), apart from moderate anxiety with deterioration (A6).

Discussion

We conducted a study to characterize trajectories of anxiety and depression change during psychological therapy for autistic people in any setting to better understand the nature of symptom change and associated risk factors.

We identified subgroups of autistic individuals receiving psychological therapies who experienced no improvement, or worsening of symptoms, as well as those who experienced improvements. Trajectories with mild or moderate pretreatment symptoms were associated with a lower likelihood of a presenting problem in the corresponding domain (for example, a mild anxiety trajectory was associated with a greater likelihood of depression as the presenting problem).

In keeping with our prior research12, the findings showed a large proportion of autistic individuals who did not sufficiently benefit from treatment. At the time of therapy delivery, clinical guidance in England stated that cognitive and behavioral interventions for co-occurring mental health conditions should be adapted for autistic people17. Recommendations included introducing a more concrete and structured approach, using written and visual information and taking a more behavioral focus. However, it is not clear from our data whether or how the interventions were adapted or were neurodiversity-affirming11, which were received by autistic people in NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression (NHS TTad) during the timeframe of this study. Autistic people have reported negative experiences of mental health services, especially when adaptations are not made2. Our findings underline the importance of adapting mental health care for autistic people, and future research is needed to evidence which adaptations work for whom8,9.

Identifying as belonging to the global majority (that is, a member of an ethnically minoritized group in England) was associated with greater odds of a deteriorating anxiety symptom trajectory relative to those identifying as belonging to any White ethnic group. Autistic people belonging to the global majority are underrepresented in autism psychological intervention literature and may likely be affected by compounded disadvantage when belonging to an ethnically minoritized group in a majority-White western country18.

Autistic individuals with severe pretreatment levels of depression and anxiety were more likely to follow an improving symptom trajectory if they had lower levels of difficulty with functioning in daily living pretreatment. These difficulties were across home, social and private leisure and close relationships. This result is in keeping with comparable general population studies14,15. However, autistic people were also shown in a previous study to have higher degrees of pretreatment difficulty with functioning in daily living compared with nonautistic adults12. The current study showed that difficulties with functioning in daily living were associated with reduced odds of following improving trajectories from severe or moderately severe initial symptoms. Therefore, difficulties in home, leisure and relationships probably (1) reflect poorly adapted and unsuitable environments19 and (2) in turn therefore perpetuate the health disparities experienced by autistic people.

Lower initial functional difficulties in social leisure activities were associated with a greater likelihood of either rapid or gradual improvement from ‘severe’ pretreatment anxiety. Social leisure is defined in the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; functioning in daily living measure)20 as ‘done with other people, for example parties, bars, clubs, outings, visits, dating, home entertaining.’ Intense and focused interests are a diagnostic feature of autism, and satisfaction with leisure activities may affect mental health outcomes more for autistic adults than nonautistic adults21. Participation in social recreation has been shown to buffer stress for autistic people22. However, opportunities to engage in social contexts free from stigma and rejection are likely to be particularly important23. Autism camouflaging (that is, adopting learned communication behaviors to camouflage autistic traits) predicts psychological distress for autistic people24. Excessive social demands from environments that are unwelcoming or poorly adapted may increase the need for camouflaging, and therefore for autistic burnout—that is, notable exhaustion and interpersonal withdrawal25. It is possible that people with higher self-reported difficulties in social leisure (who were less likely to benefit from anxiety treatment) were affected by autistic burnout. Autism-adapted social interventions to support with camouflaging and burnout could be fruitful avenues for adjunct interventions. In addition, opportunities for neuro-affirming social support may be helpful.

Intellectual disability was associated with membership of classes experiencing moderate baseline depression and improvement from initial moderate anxiety. This was somewhat surprising, given that people with intellectual disabilities generally also experience barriers that mean that they benefit less from psychological therapies than people without26. This may reflect referral patterns (with those experiencing greater need referred to specialist services) or the relative disadvantage that autistic people without an intellectual disability also experience.

Limitations

The measures of depression, anxiety and daily functioning used here have not been specifically validated in an autistic population27. However, measurement variance was found to be small or negligible between autistic and nonautistic college students on both the anxiety and depression measures used in our study, supporting the argument that the measures were capturing the same constructs in both groups28. Recent work on autistic burnout as an experience distinct from depression and reflecting a response to poorly adapted environments highlights that current measures do not capture all aspects of autistic people’s experiences29. The meaning of ‘recovery’ or ‘improvement’ for autistic people’s mental health should therefore not be assumed to be the same as for nonautistic people, and more work is needed to clarify valued outcomes from lived experience expertise.

Entropy scores observed within the final models did not suggest good confidence for most likely class allocation. However, when using modal class assignment, the proportions of individuals within classes showing reliable improvement, recovery and deterioration by the end of treatment showed a pattern consistent with the mean trajectories of groups. In addition, the statistical technique used for the regression adjusted for the uncertainty involved in class allocation and was therefore robust to lower entropy statistics.

Owing to the underdiagnosis of autism, there were probably many autistic individuals within the MODIFY dataset whose outcomes could not be included. Only individuals who engaged with treatment (and received at least three sessions) were included, and therefore, this study cannot tell us about those who did not engage (as well as those who were not referred). Although the sample was representative of individuals with a known autism diagnosis who accessed NHS TTad, it is not fully representative of all autistic people with anxiety and depression in need of, or accessing, treatment. Finally, ethnically minoritized participants were more likely to have missing endpoint data and were underrepresented in this cohort.

Furthermore, it was regrettable that we needed to combine ethnicity categories into those reflecting individuals identifying their ethnicity as White or as belonging to the global majority (ethnically minoritized in England). However, we were limited by small numbers in several ethnicity groups, which meant that ORs could not be calculated. We decided that this limited, binary analysis would be preferable to excluding the data altogether. Our finding points to the need for finer-grained future analyses that investigate the intersection of autism and race and ethnicity in relation to health inequalities. In addition, it was regrettable that sex was recorded as a binary variable in these data (male and female), which did not include a wider range of gender identities.

Research and implications for clinical practice

Trajectories could be distinguished with greater confidence at the third session than at baseline (comparing pretreatment and session 3 outcome measures). However, the trajectories in this study should not be reified or treated as ‘most likely’ treatment outcomes for any individual. A lack of improvement by the third session should not provoke pessimism in the person receiving therapy or the clinician or be interpreted as a likely indicator of poor overall outcome. Individuals receiving therapy may need additional processing time as an adjustment, for example9. Instead, our findings suggest that the third session could be an opportune moment for collaborative review—to empower the individual receiving therapy to feed back on how adaptations are (or are not) working. This could be a chance to step-up care, consider combination or augmented treatment strategies and/or identify for whom even more thorough autism-specific and cultural adaptations might need to be made.

Ethnically minoritized autistic people appear to be especially in need of targeted support and may benefit from cultural adaptations to therapy not just those made for autistic adults30. Work is needed to understand their experiences of treatment and improve care, and in the future, finer-grained analyses are needed to help understand the intersection of autism, race and culture, as well as a range of gender identities, in relation to mental health intervention outcomes.

Pretreatment difficulties with functioning in daily living, including social leisure activities, may warrant further attention as a target for support before, or alongside, treatment as usual. Proposals for autism-informed, neurodiversity-affirming social support (with an appreciation for the complexities of autism-masking and burnout) may be helpful31.

Further research is needed to clarify how to adapt and improve psychological interventions for autistic people. Following the present study, research is recommended to clarify how adaptations to care can be implemented to improve outcomes, including whether (1) pretherapy support, (2) a third-session review or (3) a combination of the two are able to improve outcomes for autistic people in NHS TTad services.

Methods

Ethics

All data were fully anonymized, and the linkage was achieved using anonymized subject identifiers provided by NHS Digital. Under the Governance Arrangements of Research Ethics Committees (REC) procedures, REC review was not required owing to the anonymization procedures followed by NHS Digital. The ethical approval for the current study using the data included in MODIFY was granted by the UCL Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology departmental REC (ethics approval number CEHP/2023/592B).

Data

Analyses were performed using the MODIFY dataset, which includes national data drawn from linked NHS Digital electronic healthcare records from across all healthcare regions in England16. The linked databases forming MODIFY include psychological treatment service data drawn from NHS TTad (formerly known as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies) in England between the years 2012 and 201932. Further information on the TTad service model and psychological therapy provision is provided in Supplementary Table 1. The TTad data were linked to (1) Hospital Episode Statistics (HES33), (2) Office of National Statistics mortality database (HES-ONS34) and (3) the Mental Health Services Dataset (MHSDS35). Further detail regarding MODIFY and linked data is also provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Participants

This study included all individuals with an autism diagnosis identified in HES or MHSDS (ICD-10 diagnostic codes F84.0 (childhood autism), F84.1 (atypical autism) and F84.5 (Asperger syndrome) as per prior research)12,16. Inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) accessing a course of treatment with any TTad services between 2012 and 2019, (2) meeting thresholds for ‘caseness’ on measures of either depression or anxiety symptoms at baseline, (3) being discharged from the services (therefore, they were not still receiving treatment) and (4) receiving at least three assessment and treatment sessions32. Individuals whose diagnosis was recorded as a severe and enduring mental illness (for example, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other psychosis requiring long-term treatment and support) were excluded, because the services do not offer standardized treatment for these conditions32.

Measures

Depression symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-936. The PHQ-9 is a nine-item depression screening tool and questionnaire, rated using a Likert scale (0–3). The PHQ-9 was routinely collected at each appointment. The PHQ-9 has been used extensively in general population research and in clinical settings, with good validity and reliability36. Anxiety symptoms were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD)-737. The GAD-7 is a seven-item screening tool and questionnaire for GAD, rated using a Likert scale (0–3) and was routinely collected at each appointment. The GAD-7 has shown good reliability and validity, excellent internal consistency and good sensitivity and specificity in detecting clinical anxiety37.

These measures have not been specifically validated in autistic populations but are routinely used in NHS TTad settings. Clinical ranges36,37 (Table 4) were used to label latent symptom trajectories. In line with the TTad manual, caseness thresholds were scores of eight or greater on the GAD-7 and ten or greater on the PHQ-938.

Difficulties with functioning in daily living were measured using the WSAS20. In keeping with prior research (for example, refs. 14,15,39), home management, private leisure, social leisure and close relationship subscales were used in the primary analysis (WSAS questions 2–5), and the employment subscale (question 1) was removed owing to a high number of ‘not applicable’ answers (Supplementary Table 5). A further sensitivity analysis used all subscale scores (Supplementary Tables 16 and 17).

Age, sex, ethnicity, employment status, use of psychotropic medication, presenting problem, presence of a long-term health condition and intellectual disability diagnosis were recorded in the NHS TTad, HES and MHSDS datasets (see Supplementary Table 2 for further detail). Sex was available in the dataset as a binary variable, and gender (including a wider range of options) was not available. Ethnicity was coded as a binary variable for this analysis, owing to low cell counts in several categories (‘Limitations’ section in ‘Discussion’; Supplementary Table 3).

Procedure

Initial data management was conducted in STATA 14.2. Subsequent analyses were conducted using MPlus 8.3.

Missing PHQ-9 and GAD-7 data were handled using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors in MPlus. The first eight sessions were modeled in this study. First, a single trajectory was estimated for all participants, separately for anxiety and depression, to obtain a mean trajectory. Two latent growth curve models (LGCM) were designed—one linear LGCM and one in which six time scores were estimated as free parameters (with two fixed to allow model identification), allowing the shape of change to be determined by the data. Model fits were compared using the root mean square error of approximation, comparative fit index, Tucker–Lewis index and standardized root mean square residual (see Supplementary Table 6 for further information on fit indices). On the basis of superior root mean square error of approximation, comparative fit index/Tucker–Lewis index and standardized root mean square residual indices, a base LGCM with free time scores was selected. The subsequent models were designed with free time scores on this basis. The syntax and model specifications are available in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. The fit indices are reported in Supplementary Table 9. The plots are shown in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7.

To allow the identification of distinct classes with reduced risk of convergence failure and computation time, we used latent class growth analysis (LCGA) to fit models that assume no within-class variance for growth factors13. Models were estimated up to eight classes to enable the possibility of higher numbers of classes to be detected than in previous general population studies14,15. LCGA models converged, and fit indices suggested an eight-class depression model and a seven-class anxiety model had the best fit. The syntax is reported in Supplementary Fig. 8. The fit indices are reported in Supplementary Table 10.

Next, GMM models were fitted, which allow variances and covariances to be obtained around growth factors. Models up to eight classes were again specified for both anxiety and depression and assessed using fit indices.

The LCGA and GMM models were compared using Bayesian inference criteria (BIC), sample size-adjusted BIC and three likelihood ratio tests (LRT) of the ratio of log-likelihoods for the k class model with the k − 1 class model: the Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin (VLMR) LRT, Lo–Mendell–Rubin-adjusted LRT (LMR-A) and bootstrap LRT (BLRT) (see Supplementary Table 6 for further information). All available fit information was reported and considered to select the best-fitting model13, and conservatively, when any k model LRTs were nonsignificant (P > 0.05) the k − 1 model was considered to be supported for selection. The GMM converged and showed superior fit (BIC, sample size-adjusted BIC) compared with LCGA. The syntax is reported in Supplementary Fig. 8. The fit indices are reported in Supplementary Table 10.

A depression GMM with five classes (D1–D5) was selected for further analysis on the basis that a six-class model returned nonsignificant VLMR-LRT, LMR-A-LRT tests and a minimally improved BIC (>0.005% reduction). An anxiety GMM with seven classes (A1–A7) was selected for further analyses on the basis that an eight-class model showed increased (poorer) BIC and nonsignificant VLMR-LRT and LMR-A-LRT tests. Entropy scores were 0.56 for the depression model and 0.61 for the anxiety model, suggesting limited confidence in the most probable class assignment—however, the R3Step analysis would be robust to this as it accounts for class assignment probabilities. Model-estimated trajectories are shown in Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13. The trajectories of sample means from the GMM models are shown below, using class modal assignment (Figs. 1 and 2). The means weighted by classification probability are shown in Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 and reported in Supplementary Table 12.

Modal class assignments and scores were exported into STATA to calculate means and 95% CI. The ‘substantive meaningfulness’ (that is, external validity)40 of these modal classes was examined by characterizing them in relation to reliable improvement, reliable recovery and reliable deterioration on the basis of the reliable change index at the end of treatment. Classes were compared with those weighted by the probability of class assignment by MPlus and reported in Supplementary Table 15.

The multinomial regression models were fitted to investigate associations between pretreatment patient characteristics and the probability of latent class membership using the R3Step procedure in MPlus. R3Step accounts for posterior probabilities of class assignment, correcting for classification error, and has been shown to be superior to approaches in which classification errors are not accounted for41. Missing WSAS data were handled in MPlus using multiple imputation with 1,000 Bayesian iterations and 100 datasets. To aid comparability, age and WSAS totals were standardized42. The WSAS scores were first entered into a multinomial regression along with the presenting problem, ethnicity, sex, age, use of psychotropic medication, presence of a long-term health condition and presence of an intellectual disability diagnosis. Next, analyses were rerun in the same way using individual WSAS subscale scores instead of total scores. A further sensitivity analysis was conducted by repeating all analyses, including employment subscale scores.

Reporting

This study was reported using the Guidelines for Reporting on Latent Trajectory Studies checklist43 (Supplementary Table 18) and the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data statement44 (Supplementary Table 19).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data used for this study are available on successful application to NHS Digital via the Data Access Request Service at https://digital.nhs.uk/services/data-access-request-service-dars. Data fields can be accessed via the NHS Digital data dictionary at https://www.datadictionary.nhs.uk/.

Code availability

Code for each of the growth models applied in this study has been included in the Supplementary Information. See Supplementary Fig. 5 for code for LGCM. See Supplementary Fig. 8 for LCGA. See Supplementary Fig. 9 for GMM.

References

Lai, M. C. et al. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 819–829 (2019).

Brede, J. et al. ‘We have to try to find a way, a clinical bridge’—autistic adults’ experience of accessing and receiving support for mental health difficulties: a systematic review and thematic meta-synthesis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 93, 102131 (2022).

Clark, D. M. Implementing NICE guidelines for the psychological treatment of depression and anxiety disorders: the IAPT experience. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 23, 318–327 (2011).

Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management (NICE guideline no. CG113). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113 (2020).

Depression in adults: treatment and management (NICE guideline no. NG222). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222 (2022).

Linden, A. et al. Benefits and harms of interventions to improve anxiety, depression, and other mental health outcomes for autistic people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Autism 27, 7–30 (2023).

Pilling, S., Baron-Cohen, S., Megnin-Viggars, O., Lee, R. & Taylor, C. Recognition, referral, diagnosis, and management of adults with autism: summary of NICE guidance. Brit. Med. J. 344, e4082 (2012).

Loizou, S. et al. Approaches to improving mental healthcare for autistic people: systematic review. BJPsych Open 10, e128 (2024).

Stark, E. et al. Psychological therapy for autistic adults: a curious approach to making adaptations. Authentistic Research Collective https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:f94d6143-58bf-4d2b-8111-c2204ff75331/files/sk35695550 (2021).

Cullingham, T. et al. The process of co‐design for a new anxiety intervention for autistic children. JCPP Adv. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12255 (2024).

Brosnan, M. & Camilleri, L. J. Neuro-affirmative support for autism, the double empathy problem and monotropism. Front. Psychiatry 16, 1538875 (2025).

El Baou, C. et al. Effectiveness of primary care psychological therapy services for treating depression and anxiety in autistic adults in England: a retrospective, matched, observational cohort study of national health-care records. Lancet Psychiatry 10, 944–954 (2023).

Ram, N. & Grimm, K. J. Methods and measures: growth mixture modeling: a method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 33, 565–576 (2009).

Skelton, M. et al. Trajectories of depression and anxiety symptom severity during psychological therapy for common mental health problems. Psychol. Med. 53, 6183–6193 (2023).

Saunders, R. et al. Trajectories of depression and anxiety symptom change during psychological therapy. J. Affect. Disord. 249, 327–335 (2019).

Bell, G. et al. Effectiveness of primary care psychological therapy services for the treatment of depression and anxiety in people living with dementia: evidence from national healthcare records in England. eClinicalMedicine 52, 101692 (2022).

Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management (NICE guideline no. CG142). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142/chapter/Recommendations#interventions-for-coexisting-mental-disorders (2012).

Steinbrenner, J. R. et al. Patterns in reporting and participant inclusion related to race and ethnicity in autism intervention literature: data from a large-scale systematic review of evidence-based practices. Autism 26, 2026–2040 (2022).

Kapp, S. K. Profound concerns about ‘profound autism’: dangers of severity scales and functioning labels for support needs. Sciences 13, 106 (2023).

Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K. & Greist, J. M. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br. J. Psychiatry 180, 461–464 (2002).

Stacey, T. L., Froude, E. H., Trollor, J. & Foley, K. R. Leisure participation and satisfaction in autistic adults and neurotypical adults. Autism 23, 993–1004 (2019).

Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L., Smith DaWalt, L., Greenberg, J. S. & Mailick, M. R. Participation in recreational activities buffers the impact of perceived stress on quality of life in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 10, 973–982 (2017).

Milton, D. & Sims, T. How is a sense of well-being and belonging constructed in the accounts of autistic adults? Disabil. Soc. 31, 520–534 (2016).

Cook, J., Hull, L., Crane, L. & Mandy, W. Camouflaging in autism: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 89, 102080 (2021).

Raymaker, D. M. et al. Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew’: defining autistic burnout. Autism Adulthood 2, 132–143 (2020).

Dagnan, D., Rodhouse, C., Thwaites, R. & Hatton, C. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services outcomes for people with learning disabilities: national data 2012–2013 to 2019–2020. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 15, e4 (2022).

Cassidy, S. A., Bradley, L., Bowen, E., Wigham, S. & Rodgers, J. Measurement properties of tools used to assess depression in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions: a systematic review. Autism Res. 11, 738–754 (2018).

Robeson, M., Brasil, K. M., Adams, H. C. & Zlomke, K. R. Measuring depression and anxiety in autistic college students: a psychometric evaluation of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Autism https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613241240183 (2024).

Higgins, J. M., Arnold, S. R., Weise, J., Pellicano, E. & Trollor, J. N. Defining autistic burnout through experts by lived experience: grounded Delphi method investigating #AutisticBurnout. Autism 25, 2356–2369 (2021).

Arundell, L. L., Barnett, P., Buckman, J. E., Saunders, R. & Pilling, S. The effectiveness of adapted psychological interventions for people from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review and conceptual typology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 88, 102063 (2021).

Charlton, R. A., Crompton, C. J., Roestorf, A. & Torry, C. Social prescribing for autistic people: a framework for service provision. AMRC Open Res. https://healthopenresearch.org/articles/2-19/v2 (2021).

The improving access to psychological therapies manual. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/the-improving-access-to-psychological-therapies-manual/ (2018).

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) analysis guide. NHS Digital https://digital.nhs.uk/binaries/content/assets/website-assets/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/hospital-episode-statistics/hes_analysis_guide_december_2019-v1.0.pdf (2019).

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Office for National Statistics (ONS) linked mortality data guide. NHS Digital https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/linked-hes-ons-mortality-data/hes-and-ons-linked-mortality-data-guide (2023).

User guidance: Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS). NHS Digital https://digital.nhs.uk/binaries/content/assets/website-assets/data-and-information/datasets/mhsds/mhsdsv6.0_userguidance_v6.0.3_may2024.pdf (2024).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613 (2001).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097 (2006).

NHS talking therapies for anxiety and depression manual. The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/nhs-talking-therapies-manual-v7.1-updated.pdf (2024).

Barnett, P. et al. The association between trajectories of change in social functioning and psychological treatment outcome in university students: a growth mixture model analysis. Psychol. Med. 53, 6848–6858 (2023).

Muthén, B. Statistical and substantive checking in growth mixture modeling: comment on Bauer and Curran (2003). Psychol. Methods https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.369 (2003).

Vermunt, J. K. Latent class modeling with covariates: two improved three-step approaches. Political Anal. 18, 450–469 (2010).

Schielzeth, H. Simple means to improve the interpretability of regression coefficients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 103–113 (2010).

Van De Schoot, R., Sijbrandij, M., Winter, S. D., Depaoli, S. & Vermunt, J. K. The GRoLTS-checklist: guidelines for reporting on latent trajectory studies. Struct. Equ. Model. 24, 451–467 (2017).

Benchimol, E. I. et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 12, e1001885 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Clinical Research Fellowship from University College London. MODIFY was originally developed through an Alzheimer’s Society grant (grant no. AS-PG-18-013). No funding body had any role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P., L.C., W.M., R.S., A.J., J.S. and C.E.B. conceptualized the study. R.P., L.C., W.M. and R.S. contributed to the methodology and analysis. C.E.B., A.J. and J.S. assessed and verified the dataset. All authors (including E.O., A.S., J.E.J.B., M.R. and S.P.) contributed to the manuscript writing and review and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–14 and Tables 1–19.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pender, R., El Baou, C., O’Nions, E. et al. Symptom change in depression and anxiety during psychological therapy for autistic adults. Nat. Mental Health (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00567-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00567-4