Abstract

Per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), are persistent environmental contaminants that have infiltrated freshwater systems. Granular activated carbon (GAC) is widely used for PFAS removal but becomes secondary waste (PFAS-GAC). Current treatment methods are energy intensive and release hazardous fluorocarbons. This study demonstrates electrothermal mineralization of PFOA and PFOS-GAC via flash Joule heating, a scalable and efficient process. Heating PFAS-GAC with sodium or calcium salts converts PFAS into inert fluoride salts with >90% fluorine conversion and >99% PFOA and PFOS removal. Simultaneously, the spent carbon is upcycled into flash graphene, offsetting treatment costs by US$60–100 per kg. This solvent- and catalyst-free method substantially reduces energy use, greenhouse gas emissions and secondary waste. A techno-economic assessment highlights its scalability and environmental benefits, offering a rapid (~1 s), cost-effective solution for PFAS remediation and upcycling of waste carbon into high-value products.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Supplementary datasets for Monte Carlo LCA and TEA calculations are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14852070 (ref. 60).

Code availability

Custom Python scripts were used to analyse Raman spectral mapping data by comparing peak intensity ratios and peak height. These scripts are available via Github at https://github.com/jlb48249/FJH_ML.

References

Al Amin, M. D. et al. Recent advances in the analysis of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—a review. Environ. Technol. Innovation 19, 100879 (2020).

Glüge, J. et al. An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Processes Impacts 22, 2345–2373 (2020).

Hunter Anderson, R., Adamson, D. T. & Stroo, H. F. Partitioning of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances from soil to groundwater within aqueous film-forming foam source zones. J. Contam. Hydrol. 220, 59–65 (2019).

Xiao, X., Ulrich, B. A., Chen, B. & Higgins, C. P. Sorption of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) relevant to aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF)-impacted groundwater by biochars and activated carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 6342–6351 (2017).

Stahl, T., Mattern, D. & Brunn, H. Toxicology of perfluorinated compounds. Environ. Sci. Eur. 23, 38 (2011).

Sunderland, E. M. et al. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 29, 131–147 (2018).

Sonmez Baghirzade, B. et al. Thermal regeneration of spent granular activated carbon presents an opportunity to break the forever PFAS cycle. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 5608–5619 (2021).

Yeung, L. W. et al. Perfluorinated compounds and total and extractable organic fluorine in human blood samples from China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 8140–8145 (2008).

Aro, R., Eriksson, U., Kärrman, A. & Yeung, L. W. Organofluorine mass balance analysis of whole blood samples in relation to gender and age. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 13142–13151 (2021).

Buck, R. C. et al. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manage. 7, 513–541 (2011).

Ellis, D. A., Mabury, S. A., Martin, J. W. & Muir, D. C. Thermolysis of fluoropolymers as a potential source of halogenated organic acids in the environment. Nature 412, 321–324 (2001).

Brusseau, M. L., Anderson, R. H. & Guo, B. PFAS concentrations in soils: background levels versus contaminated sites. Sci. Total Environ. 740, 140017 (2020).

Scher, D. P. et al. Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in garden produce at homes with a history of PFAS-contaminated drinking water. Chemosphere 196, 548–555 (2018).

Xiao, F., Hanson, R. A., Golovko, S. A., Golovko, M. Y. & Arnold, W. A. PFOA and PFOS are generated from zwitterionic and cationic precursor compounds during water disinfection with chlorine or ozone. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 5, 382–388 (2018).

Belkouteb, N., Franke, V., McCleaf, P., Köhler, S. & Ahrens, L. Removal of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in a full-scale drinking water treatment plant: long-term performance of granular activated carbon (GAC) and influence of flow-rate. Water Res. 182, 115913 (2020).

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Proposed PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (US EPA, 2023); https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas#:~:text=On%20March%2014%2C%202023%20%2C%20EPA,known%20as%20GenX%20Chemicals)%2C%20perfluorohexane

Gagliano, E., Falciglia, P. P., Zaker, Y., Karanfil, T. & Roccaro, P. Microwave regeneration of granular activated carbon saturated with PFAS. Water Res. 198, 117121 (2021).

McCleaf, P. et al. Removal efficiency of multiple poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in drinking water using granular activated carbon (GAC) and anion exchange (AE) column tests. Water Res. 120, 77–87 (2017).

Dastgheib, S. A., Mock, J., Ilangovan, T. & Patterson, C. Thermogravimetric studies for the incineration of an anion exchange resin laden with short- or long-chain PFAS compounds containing carboxylic or sulfonic acid functionalities in the presence or absence of calcium oxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60, 16961–16968 (2021).

Xiao, F. et al. Thermal stability and decomposition of perfluoroalkyl substances on spent granular activated carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 7, 343–350 (2020).

Watanabe, N., Takemine, S., Yamamoto, K., Haga, Y. & Takata, M. Residual organic fluorinated compounds from thermal treatment of PFOA, PFHxA and PFOS adsorbed onto granular activated carbon (GAC). J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 18, 625–630 (2016).

Feng, M. et al. Characterization of the thermolysis products of Nafion membrane: a potential source of perfluorinated compounds in the environment. Sci. Rep. 5, 9859 (2015).

Stoiber, T., Evans, S. & Naidenko, O. V. Disposal of products and materials containing per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): a cyclical problem. Chemosphere 260, 127659 (2020).

Martin, K. V. et al. PFAS soil concentrations surrounding a hazardous waste incinerator in East Liverpool, Ohio, an environmental justice community. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 80643–80654 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and the contribution of unknown precursors and short-chain (C2–C3) perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids at solid waste disposal facilities. Sci. Total Environ. 705, 135832 (2020).

Loganathan, B. G., Sajwan, K. S., Sinclair, E., Senthil Kumar, K. & Kannan, K. Perfluoroalkyl sulfonates and perfluorocarboxylates in two wastewater treatment facilities in Kentucky and Georgia. Water Res. 41, 4611–4620 (2007).

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (116th US Congress, 2019); https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ92/PLAW-116publ92.pdf

Abou-Khalil, C. et al. Enhancing the thermal mineralization of perfluorooctanesulfonate on granular activated carbon using alkali and alkaline-earth metal additives. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 11162–11174 (2024).

Xiao, F., Challa Sasi, P., Alinezhad, A., Sun, R. & Abdulmalik Ali, M. Thermal phase transition and rapid degradation of forever chemicals (PFAS) in spent media using induction heating. Environ. Sci. Technol. 3, 1370–1380 (2023).

Singh, R. K. et al. Breakdown products from perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) degradation in a plasma-based water treatment process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 2731–2738 (2019).

Algozeeb, W. A. et al. Flash graphene from plastic waste. ACS Nano 14, 15595–15604 (2020).

Cheng, Y. et al. Flash upcycling of waste glass fibre-reinforced plastics to silicon carbide. Nat. Sustainability 7, 452–462 (2024).

Dong, S. et al. Ultra‐fast, low‐cost, and green regeneration of graphite anode using flash Joule heating method. EcoMat 4, e12212 (2022).

Deng, B. et al. High-temperature electrothermal remediation of multi-pollutants in soil. Nat. Commun. 14, 6371 (2023).

Cheng, Y. et al. Electrothermal mineralization of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) for soil remediation. Nat. Commun. 15, 6117 (2024).

Eddy, L. et al. Electric field effects in flash Joule heating synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 16010–16019 (2024).

Luong, D. X. et al. Gram-scale bottom-up flash graphene synthesis. Nature 577, 647–651 (2020).

Crosby, N. T. Equilibria of fluorosilicate solutions with special reference to the fluoridation of public water supplies. J. Appl. Chem. 19, 100–102 (2007).

Suzuki, Y., Park, T., Hachiya, K. & Goto, T. Raman spectroscopy for determination of silicon oxyfluoride structure in fluoride melts. J. Fluorine Chem. 238, 109616 (2020).

Puts, G., Crouse, P. & Ameduri, B. Polytetrafluoroethylene: synthesis and characterization of the original extreme polymer. Chem. Rev. 119, 1763–1805 (2019).

Chen, W. et al. Heteroatom-doped flash graphene. ACS Nano 16, 6646–6656 (2022).

Finnveden, G. et al. Recent developments in life cycle assessment. J. Environ. Manage. 91, 1–21 (2009).

Guinée, J. B. et al. Life cycle assessment: past, present, and future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 90–96 (2011).

Hellweg, S. & Milà i Canals, L. Emerging approaches, challenges and opportunities in life cycle assessment. Science 344, 1109–1113 (2014).

Zhang, K. et al. Destruction of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) by ball milling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 6471–6477 (2013).

Siriwardena, D. P. et al. Regeneration of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance-laden granular activated carbon using a solvent based technology. J. Environ. Manage. 289, 112439 (2021).

This changes everything… Universal Matter https://www.universalmatter.com/ (2024).

Wyss, K. M. et al. Synthesis of clean hydrogen gas from waste plastic at zero net cost. Adv. Mater. 35, 2306763 (2023).

Wyss, K. M., Deng, B. & Tour, J. M. Upcycling and urban mining for nanomaterial synthesis. Nano Today 49, 101781 (2023).

Eddy, L. et al. Automated laboratory kilogram‐scale graphene production from coal. Small Methods 8, 2301144 (2023).

Beckham, J. L. et al. Machine learning guided synthesis of flash graphene. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106506 (2022).

Gerken, M. et al. The NMR shifts are not a measure for the nakedness of the fluoride anion. J. Fluorine Chem. 116, 49–58 (2002).

Leaders in LCA and sustainability assessment. OpenLCA https://www.openlca.org/ (2025).

GREET. US Department of Energy https://www.energy.gov/eere/greet/ (1995).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Scotland, P. et al. Mineralization of captured perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid at zero net cost using flash Joule heating. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14852070 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The funding of the research is provided by Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-22-1-0526, J.M.T.), US Army Corps of Engineers, ERDC (W912HZ-21-2-0050, J.M.T., B.I.Y., Y.Z., S.G.Z., C.G.), the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (J.L.B.), the Stauffer–Rothwell Scholarship from Rice University (K.M.W.) and Rice Academy Fellowship (Y.C.). Computer resources were provided through the US Department of Energy award (BES-ERCAP0027822, B.I.Y.). C.-H.C. and Y.H. acknowledge Welch Foundation (C-2065), and American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (67236-DNI10). Permission to publish was granted by Director, Geotechnical and Structures Laboratory, ERDC. We acknowledge and thank A. Kimble and J. Puhnaty from ERDC, who contributed to the preparation of the PFOA-GAC used in this work. B. Chen aided in the XPS analysis. We acknowledge C. Kittrell for his advice and support in the early stages on this project. The characterization equipment used in this project is partly from the Shared Equipment Authority and the Electron Microscopy Core at Rice University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S. conceived the idea to use sodium as a mineralizing agent for PFOA, PFOS and PTFE, conducted IC, LCMS, CIC, NMR, XRD, XPS, TEA and paper writing under the guidance of J.M.T. K.M.W performed GC-MS, Raman spectroscopy and contributed to the experimental design ideas and LCA. Y. Cheng aided with experimental design and experiments, L.E. contributed to initial experiment testing. J.L.B. contributed to Raman analysis and paper writing. J.S. contributed to the LCA and TEA. C.H.C. performed TEM characterization. T.S. contributed to NMR analysis. Y. Chung and B.W. contributed to IC and LCMS. Y.-Y.S. and J.A.D. contributed to IC. B.D. contributed to experimental design ideas and part of the reaction schematics. Y.Z. contributed to DFT and computational data. Y.H. supervised C.H.C. in performing TEM characterization. B.I.Y. supervised Y.Z. in performing computational experiments. M.S.W. supervised Y.C. B.W. and J.A.D. M.T. supervised Y.-Y.S. S.G.Z. and C.G. contributed PFAS-adsorbed GAC samples. J.M.T. supervised P.S. for all the process, guided P.S. in paper writing and oversaw the entire project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Intellectual property (IP) has been filed by Rice University on the FJH strategy for PFAS destruction, which is being licensed to companies in which J.M.T. is a shareholder, but not an officer, director or employee. Conflicts of interest are mitigated by disclosure to and compliance with the Office of Sponsored Programs and Research Compliance at Rice University. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Water thanks Feng Xiao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Quantification of inorganic and organic F.

a) Ion chromatography results of 0.1 g of GAC/PFOA and GAC/PFOA/x1.2Na after FJH, (n = 3 for all samples). b) Inductive Couple Plasma-Mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) of the filtrate of i) neat GAC (n = 1), ii) GAC/130 V (n = 3), and iii) GAC/PFOA/130 V (n = 3). c) LCMS quantification of the remaining organic F derived from PFOA. d) LCMS results of the GAC/PFOA and GAC/PFOA/NaOH when FJH at 130 V for 1.00 s. The data in 1a, 1b ii-iii, and 1 d are presented as the mean ± s.d. of the LCMS results from 3 parallel experiments (n = 3).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Gas chromatograph mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of reaction byproducts.

a) A picture of the gas capture setup to collect gases evolved by flash Joule heating. A perforated brass electrode allows for the capture of gases evolved during the reaction. The captured gases are then analyzed using GC-MS to probe possible perfluorocarbon production during the PFOA degradation process. The instrumental scan resolution was set to end at 300 m/z, so higher mass fragments were not observed. b) Mass spectrum of peak #1, the perfluoro pentene peak. c) Mass spectrum of peak #2, the perfluoro hexene peak. d) Mass spectrum of peak #3, the perfluoro heptene peak, the decarboxylated parent PFOA peak.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Characterization of the reactants and FJH reaction products.

a) Statistic Raman spectrum of PFOA-GAC starting material and optimized GAC-derived flash graphene (FG) product that was FJH at 150 V and 1.00 s. The solid line and colored shadows represent the average value and standard deviation of 100 sampling points, respectively. b) Reaction mass yield with respect to reaction voltage at two different pulse times. The data are presented as the mean ± s.d. of the reaction mass yield from 3 parallel experiments (n = 3). c) XRD spectra of the raw materials and FJH products before and after rinsing (Powder Diffraction File 00-041-1487, Graphite-2H and 01-080-8615, NaF). d) XPS survey spectra of the raw material and FJH products before and after rinsing. e) BET surface area analysis isotherms of the raw starting material GAC and the FJH reaction products. f) TEM analysis of the produced graphene. The inset shows an FFT of the highlighted area, the scale bar is the same as the TEM image.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Characterization of GAC/PFOS/Na before and after FJH.

a) LCMS results for GAC/PFOS/Na FJH at 130 V for 2.00 s. The PFOS removal efficiency is 99.97%. The data are presented as the mean ± s.d. of the LCMS results from 3 parallel experiments (n = 3). b) XRD spectra of the raw materials and FJH products. The blue trace represents a sample containing a slightly higher loading of PFOS so that we can observe the NaF peaks in the XRD spectra. c) 19F NMR spectra of the raw material and FJH products before and after rinsing, d) XPS elemental spectra of the raw material and FJH products.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Analysis of PFOA-GAC mixed with Ca(OH)2 (0.5 calcium ions for every fluoride atom) and FJH at 110-150 V for 0.50 s.

a-b) Ion chromatography analysis of the samples, post-FJH. 94% of elemental F present in the starting material is recovered as mineralized fluoride when FJH at 150 V (n = 1). One set of reactions was conducted as a proof of concept to limit the exposure of the sensitive analytical equipment to dilute H2SO4. c) Thermodynamics analysis using the HSC chemistry package shows that the mineralizing agent reacts readily with all fluorocarbons. This suggests that the addition of Ca(OH)2 drives the mineralization process. d) The average Raman spectra of the 110 V and 130 V flash at 59 mF. The spectra were collected from 100 sampling points of the powdered product. The average D/G and 2D/G intensity ratios of the 110 V flash are 0.34 and 0.68, respectively. The graphene yield is 96%. The average D/G and 2D/G intensity ratios of the 130 V flashes are 0.25 and 0.72, respectively. The graphene yield is 98%. High-quality FG was produced. e) Bulk crystal structure analysis by XRD of the Ca(OH)2, PFOA-GAC mixed with Ca(OH)2, and the product after FJH at 130 V. The green circles highlight the CaF2 phase. f) TEM image containing an FFT inset of the highlighted area shows turbostratic stacking of the domains and strong graphitic character with minimal amorphous character.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Analysis of PFOA-Resin mixed with 2 molar eq of sodium per mole F in PFOA using NaOH, and FJH at 80 V for 1.00 s.

a) XPS shows the high F content in the original PFOA-Resin. b) Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of the anion exchange resin with adsorbed PFOA. The C-F stretching vibration can be observed at 1204 and 1148 cm-1. c) Thermal gravimetric analysis-differential scanning calorimetry (TGA-DSC) shows the various stages of weight loss of the resin. The first stage includes PFOA degradation followed by depolymerization of the resin then blackening. d) Reaction vessel after FJH. The sample shatters due to rapid gas formation and expansion. 80 V is the maximum voltage where the solid remains in the inner chamber and can be analyzed. e) XRD analysis of the post-reaction powder shows the presence of NaF. f) Ion chromatography results of the reactions. 66.7% of the PFOA is mineralized into inorganic NaF. The apparatus is a constraint of these samples as the glass tube shatters at high voltages. The data are presented as the mean ± s.d. of the IC results from 3 parallel experiments (n = 3).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Molecular model depictions of the simulations, and the chemical equations derived from those simulations.

Reaction Pathway 1 derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT) simulations.

Extended Data Fig. 8 DFT simulations.

a) Reaction Pathway 2 derived from DFT simulations. b) Energy calculations for the reaction steps of reaction pathways 1 and 2. The total energy goes down steadily step by step, which indicates that the above three rules of thumb are valid for energetics analysis. The reaction is driven by the reduction of F by Na. Because of the high electronegativity of F atoms, the F-C covalent bonds are highly frustrated, and the frustration can be released by replacing F with OH or removal of F through forming C = C double bonds.

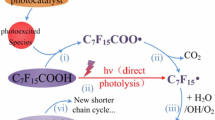

Extended Data Fig. 9 Reaction pathways for production of NaF and Na2SiF6.

Proposed reaction pathway for the degradation of PFOA in the presence of NaOH via FJH into inorganic fluorine salts.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Scaled up reaction to mineralize gram scale PFOA-GAC.

This demonstrates our scale up technology in the lab to treat 3 g of PFOA on waste GAC. The starting PFOA concentration was 6.3 mg g-1 GAC. No short chain PFOA remained and the removal efficiency for PFOA was >99.9%. The balance shows that 2.6 g of graphene formed with small amounts of metal fluoride salts.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes and Sections 1–10, Figs. 1–32, Tables 1–10 and Refs. 1–45.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Scotland, P., Wyss, K.M., Cheng, Y. et al. Mineralization of captured perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid at zero net cost using flash Joule heating. Nat Water 3, 486–496 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00404-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00404-z

This article is cited by

-

Advances in PFAS treatment in water in 2025

Nature Reviews Clean Technology (2026)

-

The PFAS treatment evolution

Nature Water (2025)