Abstract

In Europe, excessive inputs of nitrogen threaten ecosystems and public health. Wetlands act as natural filters, removing excess nutrients and protecting downstream waters. Using high-resolution data on nitrogen surplus and wetland distribution, we estimate that existing European wetlands remove 1,092 ± 95 kt of nitrogen per year. Restoring 27% of wetlands historically drained for agriculture (3% of land area), targeted in high nitrogen input areas, could reduce current nitrogen loads to the sea by 36%, but with potential costs to agricultural productivity. A more efficient strategy targets wetland restoration on farmlands projected to be abandoned by 2040, yielding a 22% load reduction and enabling major rivers such as the Rhine, Elbe and Vistula to meet water quality targets with minimal agricultural impact. Our findings highlight wetland restoration as a cost-effective, policy-relevant solution that, if spatially targeted, can deliver major water quality improvements while supporting the European Union’s broader goals on climate, biodiversity and agricultural sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Surface waters globally exhibit elevated concentrations of nitrogen (N), primarily stemming from the widespread use of agrochemicals such as inorganic fertilizers1,2, livestock waste, wastewater disposal and the deposition of atmospheric N from the combustion of fossil fuels3,4. In densely populated and intensively cultivated catchments, this has dramatic consequences for aquatic ecosystems, resulting in multiple pollution threats both within the catchment and further downstream. These threats include dead zones in coastal waters5, harmful algal blooms6 and biodiversity loss7,8,9. Large N loads in streams might also aggravate water scarcity as pollution renders the water unsafe for use10.

These threats clearly indicate the need to reduce the export of excess nutrients from intensively managed landscapes to inland and coastal waters11. In response, the European Union (EU) has adopted several directives aiming at curbing N pollution for water protection, in particular, the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive (91/271/EEC)12 and the Nitrates Directive (91/676/EEC)13, as well as the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC)14 and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008/56/EC)15. In addition, European seas are also protected under four international conventions: the Helsinki Convention on the Baltic Sea (Helsinki Commission (HELCOM)16), the OSPAR Convention on the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR17), the Barcelona Convention on the Mediterranean (UNEP18) and the Bucharest Convention on the Black Sea (Black Sea Commission19). However, annual N inputs into the European environment still exceed the safe planetary boundaries by a factor of 3.3 (ref. 20), with N concentrations in EU surface waters still exceeding thresholds for good ecological status in more than 57% of freshwater monitoring stations21 and about 81% of marine waters reported as eutrophic for the period 2016–201922. To address this, considerable efforts have been made to improve wastewater treatment plants and implement better agricultural management practices to reduce nutrient pollution of waters. The European Green Deal23 (European Commission (EC), 2019) also fosters the implementation of nature-based solutions (NBSs) for their potential to address both the climate and environmental crises while contributing to sustainable development24. Within the objectives of the Green Deal, which also includes key strategies such as the Farm-to-Fork Strategy25 (EC, 2020), the Biodiversity Strategy26 (EC, 2020) and the Zero Pollution Action Plan27 (EC, 2021), there is the need to “reduce nutrient losses by at least 50%, while ensuring that there is no deterioration in soil fertility”. Promoting NBSs and their estimated co-benefits for climate change mitigation and halting ecosystem degradation are key points of the Nature Restoration Law (NRL28; EU, 2024/1991), which aims to establish effective restoration measures covering a minimum of 20% of EU land and sea areas by 2030. The NRL features specific restoration targets for agricultural ecosystems to reduce net emissions of greenhouse gases and increase biodiversity, while fostering integrated pest control and nutrient management.

Among the wide range of NBSs, wetlands hold substantial potential for improving water quality. Following the Ramsar convention, wetlands are defined here as marsh, fen, peatland or water areas—natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with static or flowing water, fresh, brackish or salty—including adjacent riparian and coastal zones (see Methods for details). These ecosystems enhance water residence times29,30 and their organic carbon-rich, often anoxic soils make them hotspots for denitrification31. The capacity of wetlands to process N is well documented at the individual wetland scale32,33,34, as well as at the scale of small and medium catchments in Europe35,36 and the United States37,38,39. There also exist a few continental-scale assessments across the United States40,41 and China42. In Europe, several studies have explored the potential of wetlands for water management43 and water retention44. However, the N retention capacity of wetlands across European catchments—and their overall impact on water quality—remains insufficiently characterized.

Strategically targeting wetland conservation and restoration to meet water quality targets presents a relevant challenge, given the widely varying N surpluses, catchment characteristics and wetland density across Europe, as well as the competition for land. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to address a number of critical questions surrounding wetlands and water quality in river basins across the 27 EU member states (EU27) and neighbouring countries. What is the magnitude of N removed by existing wetlands in European river basins? How would the loss of these wetlands impact stream N loads? How can we strategically target wetland restoration to increase the removal of N and meet water quality targets, while also maintaining agricultural productivity?

We hypothesize that restoration goals should vary spatially to meet country-specific water quality targets, while also focusing restoration in N hotspots and in regions where wetlands have been drained for agriculture. Furthermore, effective restoration design needs to also consider the competing goals of meeting environmental targets, while maintaining agricultural production. In this context, we first estimated the N removal potential of existing wetlands by leveraging recent datasets on N surplus45 and wetland extent mapped at the European scale46 with a physically based model47. We included in our analysis the EU27 countries plus Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Norway, Switzerland, Serbia and the United Kingdom. Next, we developed a range of wetland restoration scenarios that consider competing objectives of water quality improvement and agricultural sustainability. We combined spatial data on water quality, wetlands drained for agriculture48 and projected farmland abandonment in 204049 to create restoration scenarios for Europe that consider current policies.

Historical wetland loss and N surplus

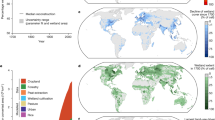

Since the industrial revolution, wetlands have been drained, dredged and filled for agriculture and urban development, with the current global extent a mere one-third of the extent in 185048,50,51,52. Europe stands out as a major hotspot of wetland loss having lost about 70% of its wetlands (~78 ± 4 Mha), with countries such as Ireland, Lithuania, Czechia, Hungary, Italy, Finland and Germany having lost over 75% of their historical wetland area (Fig. 1a). This is consistent with other studies that estimate European wetland losses to be between 56% and 80%, most of which occurred in the last 75 years53,54.

a, Map of wetland drained as a fraction of the wetland cover in 1850. Data from ref. 48 resampled at the HydroBASIN Level 7 scale (https://www.hydrosheds.org/products/hydrobasins). b, Wetland drained as a fraction of the wetland cover in 1850 for different drivers of wetland drainage for European countries. The seven drivers of wetland loss specified in ref. 48 are grouped here into agriculture (that is, cropland, pasture, peat extraction, rice and wetland cultivation), forestry and urban. AL, Albania; AT, Austria; BE, Belgium; BG, Bulgaria; CH, Switzerland; CY, Cyprus; CZ, Czech Republic; DE, Germany; DK, Denmark; EE, Estonia; EL, Greece; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; FR, France; HR, Croatia; HU, Hungary; IE, Ireland; IT, Italy; LT, Lithuania; LV, Latvia; ME, Montenegro; MK, North Macedonia; NL, Netherlands; NO, Norway; PL, Poland; PT, Portugal; RO, Romania; RS, Serbia; SE, Sweden; SI, Slovenia; SK, Slovakia; TR, Turkey; UK, United Kingdom. c, Comparison of the temporal trends of total N surplus and wetland area drained for agriculture at the European level. The N surplus data were obtained from ref. 45, while the data for the extent of wetland drained for agriculture were taken from ref. 48. d, Relationship between the N surplus (average between 2014 and 2018) normalized over the river basin area and the percentage wetland drained for agriculture as a fraction of the river basin-scale wetland cover in 1850, derived from HydroBASIN at the Level 7 scale. The box plot was generated for n = 2,283 watersheds in HydroBASIN at the Level 7 scale. The horizontal line in each box represents the median (50th percentile). The bounds of the box indicate the interquartile range (IQR) from the first quartile (25th percentile) to the third quartile (75th percentile). Whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the IQR of the quartiles; values outside this range are considered outliers (not shown in this plot for clarity).

Agricultural drainage is responsible for the majority of the widespread wetland loss (~81%, 63 Mha), with forestry-driven losses concentrated in a few Scandinavian and Baltic regions (Fig. 1b). The rate of agricultural wetland loss increased sharply in the early twentieth century, reaching its peak during the period 1950–1970 (Fig. 1c), and has since declined, with current rates of loss being only a fraction of historical levels51 (Fig. 1c).

This temporal pattern parallels that of landscape N surplus, with the surplus showing a delayed response, rising after the mid-1940s, reaching a peak in the 1980s and 1990s, and declining thereafter by 25% due to European environmental policies and regulations (Fig. 1c). The landscape N surplus, defined as the difference between anthropogenic N inputs (mineral fertilizer, manure, atmospheric deposition and biological N fixation) and non-hydrological N outputs (N from harvested crops and grass removal; Methods)45, characterizes the amount of excess N that can pollute our waterways or accumulate in soil and groundwater as legacy N11,55 (Fig. 1c). The 20-year time lag between the peaks of wetland loss and N surplus highlights the pattern of agricultural evolution across the EU, where widespread drainage for agriculture56 was followed by the increased application of mineral N fertilizers57,58. While such intensification has improved the agricultural productivity and self-sufficiency of the EU in cereal production59,60, it has also led to a loss of landscape diversity and features (for example, wetlands and hedgerows) and an accumulation of nutrients (for example, the use of N fertilizers on cropland) with detrimental effects on soil quality and aquatic ecosystems61,62.

The relationship between N surplus and wetland drainage at the EU scale generally persists at finer spatial scales (Extended Data Fig. 1), especially in regions where agricultural intensification has involved increased drainage, fertilizer use, irrigation and livestock density. However, there exists substantial variability across the EU due to differences in land-use transitions and agricultural practices. This variability is particularly evident along the Baltic Sea’s coastline as its limited connection to the Atlantic Ocean increases the risk of severe eutrophication. In northern areas of the Baltic Sea drainage basin, there has been considerable wetland loss coupled with a relatively low N surplus (Extended Data Fig. 1). Conversely, extensive wetland loss coincides with high N surplus particularly in the southern region of the basin that is dominated by agriculture63. In response, regional initiatives such as HELCOM and the Baltic Sea Action Plan have set nutrient reduction targets for each country64,65. In contrast, in the Balkan regions along the Danube River basin, there has been extensive wetland drainage for agriculture, but the N surplus is relatively low. This can be attributed, in part, to initiatives such as the adoption of the Bucharest Convention on the Black Sea in 1994 and establishment of the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) in 1998 that probably played a key role in reducing the N surplus in parts of this region. The relationship between wetland loss and N surplus hotspots is critical for the design of targeted wetland restoration scenarios to improve water quality40.

N removal by current wetlands

We estimated the N removal by around 2.6 million wetlands across the EU using a spatially explicit model developed by Cheng and Basu47 in combination with a wetland density dataset46 (Fig. 2a) and a 10-km landscape N surplus dataset45 (Fig. 2b). The model, previously applied in the United States40 and China42, is based on empirical data from 178 wetlands across the world, with 42 of the wetlands in Europe. N removal in this model is estimated as the difference between inputs and outputs, incorporating both temporary (for example, plant uptake) and permanent (for example, denitrification) removal processes. N inputs into each wetland were derived from the surrounding N surplus45 within HydroBASIN Level 7 (HYBAS-7). Wetland N removal was modelled using first-order reaction kinetics, with rate constants and residence times varying inversely with wetland size (see Methods for details).

a, Current wetland density from ref. 46 aggregated at the HYBAS-7 watershed scale. b, Average N surplus input for 2014–2018 estimated from the data in ref. 45 and aggregated at the HYBAS-7 scale. c, Estimated N removal by current wetlands aggregated at the HYBAS-7 watershed scale. A threshold of 10 kg ha−1 yr−1 has been set for the colour bar for better visualization across the 2,283 watersheds at the HYBAS-7 scale. d, River basin-scale estimate of riverine N load increases if current wetlands are lost. River basins have been aggregated according to the Catchment Characterization and Modelling 2 (CCM2) database and are delineated by thick dark lines, with 299 inland and 587 coastal basins (Methods). Note that only river basins with a contributing area greater than 100 km2 are shown for better visualization.

Figure 2a shows wetland densities across the EU, aggregated to the HYBAS-7 scale. The total wetland area is ~32 Mha (23 Mha for the EU27), with the highest densities observed in northern European countries such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway and Sweden (Fig. 2a). Variation in wetland sizes across the region contributes to a wide range of estimated residence times (8–371 days) and first-order rate constants (0.0013–0.067 d−1). The landscape N surplus also varies across Europe, with the highest values (150–200 kg ha−1 yr−1) in river basins in the Netherlands and Belgium (Fig. 2b). This spatial variability in both wetland size and N surplus results in N input rates into wetland of 0.5–1,083 kg ha−1 yr−1 and wetland-specific N removal rates of 0.1–437 kg ha−1 yr−1, which is consistent with other estimates in Sweden36, the United States40 and China42.

Watershed-averaged N removal rates were then estimated as a function of the modelled wetland N removal rates and wetland densities within each river basin (Fig. 2c). These rates were found to vary across the EU, with the highest values (Fig. 2c) occurring in regions where high wetland densities coincide with high N surplus, such as parts of the United Kingdom, Ireland, the Netherlands and Belgium. In contrast, the lowest removal rates are observed in southern Europe, where both wetland density and N surplus are comparatively low (Fig. 2c).

We estimated the total N removal by existing wetlands across the EU to be 1,092 ± 95 kt yr−1, representing 6.7% of the current landscape-level N surplus of 16,298 kt yr−1. For context, the average riverine N load discharged into European seas from 886 large river basins during the period 2014–2018 was ~4,239 kt yr−1 (ref. 66). This suggests that, in the absence of existing wetlands, riverine N loads into the sea could be ~25% higher (~5,331 kt yr−1).

The contribution of wetlands to N removal exhibits significant spatial variability, driven by differences in wetland density and landscape N surplus. Without the current wetlands, the N loads into the Danube, Elba, Wisla and Oder river basins could increase by 20%, 29%, 33% and 38%, respectively (Fig. 2d). For comparison, Cheng et al.40 reported that N loads into the Mississippi River basin would increase by 51% in the absence of wetlands, while Zhang et al.34 reported a 24% increase in N loading following the destruction of restored wetlands in a headwater river in southern China.

Therefore, preserving these ecosystems is crucial, especially in regions where N surplus levels are high. Safeguarding existing wetlands can ensure the continuity of their ecological functions, thereby laying a solid foundation for successful restoration efforts in the future. This approach not only maximizes the effectiveness of conservation measures but also fosters resilience in aquatic ecosystems against the impacts of nutrient pollution.

Wetland restoration scenarios

We developed three sets of wetland restoration scenarios, each defined by different upper limits on the maximum area that could be restored. These limits reflect a combination of environmental and economic constraints in the EU, as well as river basin-specific N load reduction targets for 299 inland and 587 coastal river basins across Europe. Modelled estimates of the current N loads for these river basins were obtained from ref. 66, while basin-specific reduction targets were available only for a subset of major rivers, including the Danube, Oder, Wisla, Nemunas, Elbe, Rhine, Daugava, Kizilirmak and Sakaraya (Extended Data Table 2). The reduction targets for these rivers varied widely, from as high as 48% for heavily polluted rivers such as the Danube to no required reduction for less polluted rivers such as the Neva and Daugava. For river basins with no specific target data, we assumed a highly ambitious, hypothetical reduction scenario of 50% using the average N load for 2012–2015 as the baseline.

In the most ambitious scenario (‘Full Restoration’), we assumed that all 63 Mha of wetlands historically drained for agriculture across Europe could be restored to meet the N load reduction targets. For each of the 886 river basins, wetlands were progressively restored until either the N reduction target was achieved or the full extent of the drained area was restored. At the EU scale, this resulted in the restoration of 17.2 Mha of wetlands, which represents 27% of the area that was drained for agriculture (Fig. 3a) and 3.2% of the total land area. This level of restoration would result in an estimated removal of N of 1,536 kt yr−1, reducing N loads into the sea by 36%, from 4,239 kt yr−1 to 2,703 kt yr−1 (Table 1).

a–c, Percentage of area drained for agriculture restored to meet the policy target of the Full Restoration (a), Cap 4% (b) and Farmland Abandonment (c) scenarios, where the drained area refers to the estimates of agriculturally drained area developed by Fluet-Chouinard et al.48, and mapped to the HYBAS-7 watershed scale. d–f, Estimated N removal by restored wetlands for the Full Restoration (d), Cap 4% (e) and Farmland Abandonment (f) scenarios aggregated at the HYBAS-7 watershed scale. A threshold of 10 kg ha−1 yr−1 has been set for the colour bar for consistency with Fig. 2b. g–i, Percentage reduction in riverine N load as a result of wetland restoration for the Full Restoration (g), Cap 4% (h) and Farmland Abandonment (i) scenarios. River basins have been aggregated according to the CCM2 database and are delineated by dark lines, with 299 inland and 587 coastal basins (Methods). Note that in the Farmland abandonment scenario (c,f,i), some portions of the Balkan regions, as well as Switzerland and Norway, have been omitted because the data for farmland abandonment are limited to the EU27 and United Kingdom49.

The extent of restoration and associated N load reductions varied across the basins, driven by spatial mismatches between N surplus hotspots and historically drained areas (see Extended Data Fig. 1 for details). The share of restored drained land ranged from just 2.5% in the Elbe basin to 19% in the Rhine and as high as 65% and 96% in the Rhone and Loire basins, respectively. In terms of total land area, this corresponds to 1.5% in the Elbe to 4.6% in the Loire basin. These values fall within the 2–7% range identified by Verhoeven et al.29 as critical for wetlands to improve water quality at the catchment scale and align with findings from other studies on wetland restoration in Europe29,35,36.

The estimated reduction in riverine N load also varied, ranging from 20% in basins such as the Rhine and Elbe to 50% in the Danube, Loire and Po basins (Fig. 3g). Under the Full Restoration scenario, N load reduction targets are met across 61.4% of Europe’s land area and in all nine river basins with explicit targets (Fig. 4). These findings are in line with previous estimates from the catchment in southern Sweden, where up to 43% of the N load could be reduced when wetlands comprised 5% of the total catchment area67,68.

a, N load reductions required to meet the N load reduction targets for 28 European river basins characterized by the highest N load. Inset: map of Europe highlighting the 28 river basins in light red. The asterisks indicate the river basins for which information on the need for N load reduction was obtained either from the specific river basin management plan or from the four international sea conventions (Extended Data Table 2). b–d, Corresponding accomplishment of the required load reduction for the three restoration scenarios: Full Restoration (b), CAP 4% (c) and Farmland Abandonment (d). The y-axis labels in a also apply to b–d. The vertical dashed lines in b–d indicate full accomplishment of the required load reduction presented in a.

While the Full Restoration scenario does have substantial water quality benefits, restoring large portions of current arable land can reduce crop production or displace it to other locations where it may have an even more negative impact69. We found that in more than half of the river basins, including, for example, the Loire, Rhone and Po, more than 10% of the current arable land would need to be restored to wetlands to meet the targets. Thus, to foster ambitious green strategies without compromising the needs of farmers, we considered two further strategies to limit the maximum area that can be restored (Methods). The first strategy follows the EU Common Agricultural Policy (‘CAP 4%’), which proposes that farmers devote 4% of current arable land to non-productive areas or features. The second strategy (‘Farmland Abandonment’) aims to restore wetlands only in areas where farmland is projected to be abandoned by 2040 due to social, economic and environmental factors49.

Under the CAP 4% scenario, 6.2 Mha of wetlands are restored across Europe (Fig. 3b), resulting in an estimated N removal of 673 kt yr−1 (Fig. 3e) and a 16% reduction in N load into the sea (Fig. 3h). However, N load reduction targets are achieved in only 2 of the 28 basins and in 12% of Europe’s land area (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Large river basins such as the Rhone, Danube and Rhine would achieve just 20%, 40% and 70% of their respective targets under this scenario (Fig. 4).

In contrast, the Farmland Abandonment scenario leads to the restoration of 8.6 Mha of wetlands with a total N removal of 910 kt yr−1 (Fig. 3f). The target N load reduction was achieved in 22.4% of the total watershed area (Table 1) and the total load into EU seas was reduced by 22% (Fig. 3i). The highest density of wetland restoration is observed in the southern watersheds of France, such as the Garonne and Rhone, as well as in the northwestern Danube basin and the lower reaches of the Elbe and Oder rivers (Fig. 3c). These catchments, characterized by both substantial projected farmland abandonment and high N surplus, emerge as critical hotspots for N removal, with removal rates exceeding 10 kg ha−1 yr−1 (Fig. 3f). Such targeted restoration included the Rhine, Wisla, Oder and Elbe (Fig. 3i and Fig. 4).

Clearly such gains in terms of N load reduction have an associated restoration cost that is not often straightforward to determine due to the different types of wetlands and the previous land use. Here we present a first attempt of a cost–benefit analysis of wetland restoration for the various scenarios, drawing on reported literature values (Extended Data Table 3). These vary from around €17–113 billion per year for the CAP 4% scenario to around €24–150 billion per year for the Farm abandonment scenario and €55–358 billion per year for the Full Restoration scenario (Table 1). Notwithstanding the considerable costs involved, it is essential to consider that environmental costs attributed to reactive N losses in Europe are estimated to be in the range of €70–320 billion per year61. Wetland restoration also has great potential to provide a variety of other ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration70,71, coastal protection72, groundwater level and soil moisture regulation73, flood regulation74,75, biodiversity support76,77 and water quality protection29,30. When such additional ecosystem services are included, we estimate (Methods) that the benefits can outbalance the foreseen annual costs for wetland restoration (Table 1). It is important to note, however, that the potential for these ecosystem services is contingent upon specific factors such as the location, design and scale of the wetlands. For example, while here we assumed the re-establishment of wetlands on areas that have been historically drained for agriculture, these areas may have undergone ecological succession or alterations in land use driven by climate change, rendering them potentially unsuitable for restoration.

The findings of our cost–benefit analysis are intended to be illustrative rather than definitive and they should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations inherent in our methodology. Primarily, our analysis relies heavily on valuation estimates derived from literature that focuses on a narrow geographic scope. This dependency on a limited set of data sources may not accurately reflect the full spectrum of economic values associated with ecosystem services provided by wetlands in Europe. Moreover, our study underscores the need for comprehensive economic data to better elucidate the long-term benefits associated with wetland restoration initiatives across diverse ecological contexts. In addition, the analysis does not fully account for the potential cost reductions achievable through various wetland restoration techniques (for example, rewetting versus the creation of constructed wetlands). A more nuanced understanding of these cost dynamics, crucial for optimizing restoration efforts and ensuring the economic feasibility of wetland conservation strategies, is deferred to future studies.

Discussion and conclusion

We have provided a novel, spatially explicit and policy-relevant framework to assess the role of wetland restoration in reducing N pollution across Europe. Our results show that European wetlands currently intercept 1,092 ± 95 kt of N per year, reducing N loads to the sea by 25% and thereby demonstrating their critical role in maintaining water quality. We have shown that wetland restoration is a cost-effective, NBS that can further reduce N loads to European seas by 16–36% and contribute to meeting N load targets in over 37% of EU catchments.

Our study offers several key contributions. First, we have developed a unique pan-European modelling framework that combines disparate datasets—N surplus maps, historical wetland distribution, projected farmland abandonment maps and river basin-specific targets—to identify priority areas for restoration and assess their effectiveness. This approach reveals both the potential and the limits of restoration across river basins. For instance, while full restoration of drained wetlands in the Seine or Rhone basins is insufficient to meet targets (Fig. 4), restoring 30% (3.6 Mha) of the drained wetlands in the Danube can fully meet the ICPDR restoration goal. Restoring a smaller area—18% of drained wetlands, specifically on farmland projected to be abandoned by 2040—could achieve up to 60% of the Danube target. Restoring only 4% of current arable land (CAP 4% scenario) can meet the full target in the Elbe and Oder basins (HELCOM, 2021 and International Commission for the Protection of the Elbe River, 2019), but only 70% of the target in the Wisla, Rhine and Meuse basins (Fig. 4). Our results also highlight that while wetland restoration can allow us to meet water quality targets in some basins, achieving good ecological status everywhere across Europe will require additional measures to reduce diffuse nutrient sources. These include reducing fertilizer use and promoting N-fixing crops, which are key priorities under the European Commission’s Zero Pollution Ambition.

Second, we have shown that spatial targeting within a river basin is essential: a non-targeted, uniform restoration of 20% of the drained area across the Danube River basin achieves only 33% of the ICPDR target (Extended Data Fig. 2), while strategic restoration in areas with high N surplus can achieve 100% of the target. This finding, consistent with earlier research from the United States, China and Sweden29,40,42,67,68, reinforces the importance of optimizing wetland placement to maximize impact and reduce costs. While our analysis assumes that wetlands can be successfully restored on existing or abandoned farmlands, we acknowledge that local biophysical and policy constraints can limit land availability. The restoration maps developed here serve as a foundation for dialogue with stakeholders, including farmers, utilities, river authorities and policymakers, to support coordinated planning and enhance water system resilience.

Third, our findings align with and inform major EU strategies such as the NRL, which mandates the restoration of 20% of EU land and sea areas and 30% of drained peatland area by 203078,79. We estimate that achieving N load reduction goals across 37% of EU catchments (Supplementary Fig. 5) would require the restoration of just 3.3% of EU27 land area (14 Mha of wetlands), well below the NRL target of 20%. Our analysis also shows that only 2.4–7.4% of drained peatlands (Extended Data Table 4) would need to be restored to meet water quality goals, although some EU member states (for example, Ireland, Bulgaria and Denmark) would require >15% restoration of drained peatlands due to the high N surpluses in those regions. While these estimates are lower than the NRL targets, simply meeting the NRL targets may not lead to improvements in water quality. Our analysis prioritizes wetland restoration in areas with high N surplus to maximize water quality benefits, while the NRL focuses on peatland restoration primarily for its carbon sequestration benefits.

These findings underscore the importance of location in determining restoration priorities. Different environmental goals, such as climate mitigation, biodiversity conservation or nutrient reduction, may require restoration in different places. Strengthening the alignment and cross-compliance of the NRL with other EU environmental legislation will be crucial to simultaneously achieve multiple objectives, including carbon sequestration, improving landscape water storage and mitigating nutrient pollution80. In this context, we propose a synergistic approach between the CAP and NRL. Rather than leaving arable land fallow, farmers could be incentivized to participate in restoration efforts as a part of the green transition. Public–private funding mechanisms, including payments for ecosystem services, offer a promising avenue to generate the financial capital required for large-scale wetland restoration81,82. This approach not only encourages environmental stewardship but also ensures equitable treatment of farmers in meeting regulatory standards, an essential component of the green transition outlined in the European Green Deal.

While our analysis is centred on Europe, the insights gained from this study have broad relevance for global water quality and ecosystem restoration efforts. Many regions across the world, including parts of North America, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, face mounting challenges from diffuse N pollution driven by agricultural intensification and have historically lost wetlands. The integrated, spatially targeted approach that we have developed can serve as a model for identifying priority areas for wetland restoration in diverse geographic and socio-economic contexts. Moreover, the recognition that the strategic restoration of relatively small land areas can yield substantial nutrient reduction benefits has important implications for land-scarce and highly cultivated regions. Our findings complement a growing body of global literature35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 emphasizing the value of NBSs, including wetlands, in meeting sustainable development goals. By tailoring restoration priorities to local nutrient hotspots and integrating them with climate and land-use policies, countries outside of Europe can also harness wetland restoration as a cost-effective tool to enhance water quality, increase ecosystem resilience and support rural livelihoods. In doing so, they contribute not only to national environmental targets but also to the broader objectives of the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

Methods

Historical wetland loss

Maps of wetland loss during the past centuries were derived from the recent estimates of Fluet-Chouinard et al.48. We filtered their database to consider only wetland loss that happened in Europe and we intersected their data with the shapefile of HYBAS-7 to assess the loss at the watershed scale. Fluet-Chouinard et al.48 identified seven drivers: cropland, forestry, peat extraction, wetland cultivation, pasture, urban and rice. Cropland is the main driver of land-use change (74.5%), followed by forestry (13.8%) and pasture (6.6%). We grouped together the five classes that are related to agriculture, that is, cropland, wetland cultivation, pasture, rice and peat extraction, and reported the results in Fig. 1. This sum corresponds to the total wetland area that has been drained since 1850 for agricultural-related processes and that will be considered for restoration (see ‘Restoration scenarios’).

Current wetlands

The starting point of our analysis was the Extended wetland ecosystem map83, the first holistic map of wetland ecosystems at the European level (Supplementary Fig. 1), produced and presented by the European Commission Mapping and Assessing Ecosystems (MAES) and their Services Working Group. The map is derived from the CORINE Land Cover (CLC) layer for the year 2018 (v20), which has been reclassified into 20 wetland classes based on ancillary spatial layers (the Copernicus products Water and Wetness 2018 and Riparian Zone Layer, the Ecosystem Types of Europe (v3.1) and the Global Spatial Water Explorer datasets).

Wetland habitats are defined according to the revised classification of the MAES nomenclature46 and the guidelines set within the Horizon 2020 Satellite-based Wetland Observation Service (https://www.swos-service.eu/). This extended definition of European wetlands according to their hydro-ecological dimension follows the Ramsar classification of wetland habitats, signed by all EU27 parties and the United Kingdom, which states that wetlands are “areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salty, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six meters”84. Furthermore, wetlands “may incorporate riparian and coastal zones adjacent to the wetlands, and islands or bodies of marine water deeper than six meters at low tide lying with wetlands”.

In addition to the traditional types of inland and coastal wetlands (that is, marshes, rivers, lakes, lagoons and estuaries), the (MAES) layer also covers forest, grassland and agricultural ecosystems that are seasonally or permanently flooded (that is, riparian forests, wet grasslands and rice fields) and are therefore considered as wetlands according to the Ramsar Convention definition and typology. This wetland reclassification and mapping considers their hydro-ecological characteristics and provides information on the real spatial extent and distribution of varied wetland habitats. This definition is broader than the operational definition of wetlands proposed by Fluet-Chouinard et al.48 to map wetland drainage in past centuries. They consider wetlands as “areas inundated or waterlogged, vegetated or not” (for example, forested swamps, bare floodplains) from which they removed open water ecosystems (for example, rivers, reservoirs and lakes), rice paddies and the annual maximum water extent along coastlines. As a result, intertidal and near-shore marine wetlands (for example, unvegetated tidal flats, salt marshes, mangroves and seagrasses) are excluded but coastal wetlands above the tideline remain.

To be consistent with other studies on wetland denitrification potential40, we subset the MAES database to consider riparian, fluvial and swamp forested wetlands, managed or grazed wet meadows, wet heath, riverine wetlands, inland marshes, open mires, salt marshes and intertidal flats.

Wetland N model

In the following, we present a brief summary of the spatially explicit model used in our analysis. For further details, the reader is referred to Cheng et al.40 and references therein.

Wetland N removal can occur via temporary (for example, plant uptake and burial) and permanent (for example, denitrification) removal processes. These processes depend on a variety of factors, including nutrient loading, wetland area, residence time, wetland types, temperature, substrate availability and constraints on microbial metabolism. This complexity contributes to a range of N removal rates, creating challenges to quantify the benefits of wetland restoration at large scales.

To address this, Cheng and Basu47 developed a reduced complexity model using empirical data on wetland removal in 178 wetlands across the world, with 42 of them being in Europe. The dataset encompasses a large range of N removal rates, ranging from 0.01 to 7,200 g m−2 yr−1, with a median removal efficiency of 48%, findings consistent with the existing literature32,85. In the reduced complexity model developed by Cheng and Basu40, N removal by wetland i Rwet,i (in kg yr−1) can be estimated as the product of the N input into these wetlands Min,i (in kg yr−1) and the percentage wetland N removal ρwet,i:

where ρwet,i can be estimated as a function of the removal rate constant ki (in d−1) and water residence times τi (in d) for that wetland using first-order removal rate kinetics:

Cheng and Basu47 further showed that a remarkably consistent, inverse relationship exists between both the N removal rate constant and water residence time τi and the wetland surface area SAi (in m2) and this relationship can be used to estimate removal rate constants using easily measurable surface areas:

where a, b, c and d are coefficients and exponents of the empirically derived relationship. One of the limitations of our model is that it does not consider the temperature dependence of the rate constant and future work should consider this dependence.

Model application to estimate wetland N removal across Europe

We estimated the first-order removal rate constant ki (in d−1) and residence time τi (in d) for each wetland in the MAES database (Supplementary Fig. 1) using the surface area from the database and equations (3) and (4). We then estimated the percentage wetland N removal ρwet,i in each wetland in the database using equation (2).

The mass of N removed by each wetland Rwet,i is a function of its N removal efficiency as well as the mass of N that is entering the wetland Min,i, which is driven by its spatial location and corresponding N inputs. For example, wetlands downstream of agricultural areas will intercept more N and thus remove more.

Spatially varying N inputs into the wetlands were estimated on the basis of the N surplus magnitudes Nsurp,i (in kg ha−1 yr−1; see ‘N surplus calculations and data sources’) mapped within HYBAS-7, the contributing area of each wetland CAi (in ha) and a reduction factor γ that quantifies the fraction of the N surplus that enters each wetland via flow through surface or subsurface pathways (equation (5)).

The reduction factor γ represents the fraction of the N surplus in the wetland’s catchment area that can potentially enter the wetland, assuming that the rest is either retained in soils and groundwater or denitrified in upstream soils. We assumed a range of values for γ of 0.3–0.5 based on both monitoring- and modelling-based literature estimates of soil and watershed denitrification rates56,85 and used Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate the effect of uncertainty on wetland N load estimates. Future work should focus on using climate- and landscape-specific reduction factors to estimate wetland N inputs.

The other key factor that drives N input into a wetland is its contributing area CAi, which is challenging to estimate for each of the 2.7 million wetlands in our study36,40,86,87. We used a simplified approach, following Cheng et al.40, where we assumed a catchment area to wetland area ratio of α, with values of α based on empirically determined relationships between wetland catchment area and wetland surface area87. The empirical distribution of α values is based on catchment delineation for more than 30,000 wetlands using high-resolution lidar data in the North American Prairie Pothole Region. We used the geometric mean and standard deviation of the data to bound α in our Monte Carlo analysis (Extended Data Table 1). Future refinements of this methodology would involve delineating the watersheds of all current European wetlands.

We also did not consider the role of hydrological connectivity between wetlands in N removal, where N removal in an upgradient wetland can potentially reduce the available N for reduction in a downgradient wetland. A more refined network-scale assessment can be developed to understand the role of hydrological connectivity in catchment-scale N removal.

N removal by wetlands at the HYBAS-7 watershed scale RTwshd was estimated by aggregating the N removal of all wetlands within the watershed area Awshd:

Monte Carlo simulations were used to characterize the uncertainty associated with estimates of N removal as a function of the uncertainties associated with k, τ, the wetland contributing area and the fraction of N surplus that is intercepted by the wetland. The ranges of values used for each parameter are provided in Extended Data Table 1. It is worth noting that the ranges of coefficients and exponents for the N removal rate (a, b, c and d) of the aforementioned inverse relationships are based on 95% confidence intervals of fitted parameters from 600 lentic systems around the world47.

We conducted 250 Monte Carlo simulations. Estimates of mean N removal are provided in the main text along with 95th confidence interval bounds from the Monte Carlo simulations.

N surplus calculations and data sources

The landscape N surplus data that we used in our analyses were obtained from ref. 45. The datasets are publicly available and are archived in the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6581441). The dataset comprises 16 N surplus estimates in the Network Common Data Form (NetCDF) file format. The 16 gridded time series of N surplus were computed by combining two estimates for fertilizer, four estimates for animal manure and two estimates for N removal from pastures. The dataset was downscaled to a 5 arcmin grid size and multiplied by the proportion of respective land area per grid cell to obtain N deposition for cropland, pasture, forest, semi-natural vegetation, non-vegetation and urban land uses. Biological N fixation is a natural process in which atmospheric non-reactive N is transformed into reactive forms through microbial activity. N fixation was calculated for cropland, pasture, forest and semi-natural vegetation by multiplying the respective areas with their N fixation rates, derived from previous studies. These rates are different for different crops and land-use categories. Finally, to calculate the total N surplus, the N inputs from non-agricultural sources, such as atmospheric deposition and biological N fixation, are summed with the agricultural component of N surplus. In particular, the total N surplus represents the difference between N inputs and N output with adjustment for volatilization losses during manure storage systems.

Thus, total N surplus NSURP,soil is the sum of the N surplus over agricultural areas (cropland and pasture) and non-agricultural areas (forest, semi-natural vegetation, non-vegetation and urban) as given in the following equation (all variables in kg ha−1 yr−1):

where i is the grid cell, y is the year, NSURP,AGRI is the N surplus over agricultural areas and NSURP,NON-AGRI is the surplus over non-agricultural areas. Specifically, the N surplus over agricultural soils accounts for the N surplus over croplands and pastures. The N surplus over croplands and pastures is estimated as the difference between the inputs into cropland and pasture through mineral fertilizers, animal manure, biological N fixation and atmospheric deposition and the N outputs through N removal via harvested crops, animal grazing and grass cutting. The N surplus over non-agricultural soils includes the N surplus over forest, semi-natural vegetation, urban and other non-vegetated areas. The N surplus over forest is the difference between N inputs into forest through biological N fixation and atmospheric deposition and N outputs via N removal from forest. The N surplus over semi-natural vegetation covers N inputs via atmospheric deposition and biological N fixation. The N surplus over urban and other non-vegetative areas is derived from N inputs via atmospheric deposition.

The N surplus estimates were compared with the datasets of Zhang et al.4, which provide N budgets at country levels across Europe for various periods. These datasets are considered reference points for validating the N surplus estimates. The authors show that the uncertainty intervals for the N surplus estimates generally capture values derived from these sources. The estimates were further compared with country-specific N surplus data for Denmark, the United Kingdom, France, Poland and Germany. These comparisons help to assess the reliability of the estimates on a more localized scale. In addition, a strong positive correlation between the estimates and the available data from these countries is reported, which indicates consistency in temporal dynamics. For further details on the complete methodology used to estimate the dataset, the reader is referred to Batool et al.45 and references therein. Each NetCDF file contains an annual variable representing N surplus with the units kilogram per hectare of grid area per year at 5-arcmin (1/12°) resolution for the period 1850–2019.

In our analysis, we aggregated the gridded data at HYBAS-7 to assess the N surplus input at the watershed scale. We repeated this process for each of the 16 N surplus estimates and took the average across these 16 realizations for each year. The final data that we used as input for the wetland N model are the average for 2014–2018 (Fig. 2b).

Riverine N load calculations and data sources

Our estimates for current N load removal in river basins, as well as for potential load removal in restoration scenarios, rely on comprehensive information on riverine loads across European river basins. Although we did not directly estimate the N load in each river basin, we used the multidecadal annual time series of N loads from the GREEN model66, which is publicly accessible at https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset?q=wpi. The GREEN model estimates the total annual nutrient load in river basins using spatially distributed information on diffuse and point nutrient sources. Although the model does not explicitly simulate wetland retention, it does estimate nutrient retention in land, rivers and lakes. Model parameters are calibrated using observed nutrient loads at monitoring stations. The model’s output was calibrated for the period 1990–2018 using publicly available data from Waterbase88 on mean annual total N concentrations. Loads were estimated by multiplying reported concentrations by the annual streamflow from the LISFLOOD-EPIC model89 at the monitoring station. A total of 36,269 observations for total N were used for calibration (additional details are provided in ref. 66). In our current removal scenario, we assumed that without existing wetland removal, the N load estimated in our model would represent an additional source in the current riverine N load. The fundamental assumption is that, although the GREEN model does not explicitly incorporate wetlands in its modelling process, its outputs are the best representation of river N loads, having been calibrated and validated across the EU using data from a large number of monitoring stations. This same rationale applies to our restoration scenarios. Introducing more wetlands into each of the specified HYBAS-7 areas could increase N load uptake as more of the N surplus can be intercepted by restored wetlands. This would prevent the N from entering the river network and ultimately reaching the sea.

Specifically, total N fluxes from land to sea were assessed with the GREEN model66,90,91, as implemented in the R open source package GREENeR92. The model’s spatial architecture is the CCM2 hydrological network93,94. Therefore, for consistency with our analyses on wetland loss (see ‘Historical wetland loss’) and N retention (see ‘Current wetlands’ and ‘Wetland N model’), we implemented two different spatial aggregation methodologies. (1) In inland river basins (Supplementary Fig. 2a), the geometrical boundaries of the river basins reported in the CCM2 spatial domain are much larger than the basins’ geometric confines in HYBAS-7. For example, the Danube River basin at the CCM2 scale contains 376 watersheds in HYBAS-7. Therefore, when we report outputs from such large river basins, we are aggregating the outputs from each of the nested HYBAS-7 watersheds. (2) In coastal river basins (Supplementary Fig. 2b), the procedure is the opposite. Given the smaller size of these coastal basins at the CCM2 level, we grouped them within the larger HYBAS-7 areas that encompass them. This ensured that we maintained alignment with the estimated N surplus inputs and the agricultural areas that were lost, which were calculated at the HYBAS-7 scale. Consequently, the total N load for any given coastal river basin at the HYBAS-7 level was determined by summing the riverine N loads from each individual watershed defined at the CCM2 scale. The N load from nested inland river basins remains the load at the outlet of the most downstream basin.

At the end of our spatial aggregation, we had a total of 299 inland river basins (Supplementary Fig. 2a) and 587 coastal river basins (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Due to incomplete data, we also excluded from our analysis river basins draining into the White Sea and from Turkey. The final spatial extent of the river network dataset is 5.56 × 106 km2 with a total average N load for the period 2014–2018 of about 4,239 kt yr−1, which is around 90% of the values reported by Vigiak et al.66.

Restoration scenarios

We developed three wetland restoration scenarios to achieve the desired reduction targets in riverine N load. When available, the reduction targets were retrieved from the four international sea conventions (the Helsinki Convention on the Baltic Sea, the OSPAR Convention on the North-East Atlantic, the Barcelona Convention on the Mediterranean and the Bucharest Convention on the Black Sea) and are reported in Extended Data Table 2. Otherwise, when such information was not available, the reduction targets were set at half the N load estimations provided by Vigiak et al.66 for the period 2012–2015. This reduction target was selected to align with the objectives of the European Commission’s Farm-to-Fork Strategy (EC, 2020), Biodiversity Strategy (EC, 2020) and Zero Pollution Strategy (EC, 2021), which advocate for a reduction in nutrient losses of at least 50% while simultaneously ensuring that soil fertility is not compromised. We recognize, however, that the call of the EU strategies for a 50% reduction in nutrient losses does not specifically address the issue of nutrient loads discharged into marine environments. Therefore, our approach should be considered a hypothetical scenario rather than an implementation of an established EU target. It is also important to note that a uniform N reduction target across all EU river basins may not be appropriate as the optimal reduction percentage could vary between rivers depending on their individual characteristics and ecological contexts. Our adoption of a uniform target was necessitated by the current lack of detailed, river-specific reduction goals. As such, we used this common target in our analysis as a provisional measure. It is anticipated that future research, enriched by more comprehensive data, will facilitate the development of tailored N load reduction targets for each river basin, thereby refining the strategies for mitigating nutrient input into European seas.

The second key input for our restoration algorithm is the maximum area available for wetland restoration. In all our restoration scenarios, we proposed to establish wetlands only in those areas where wetlands were originally present and that have been converted for agricultural purposes. We obtained this information by leveraging the maps of wetland loss from ref. 48 (see ‘Wetland loss’), computing for each sub-basin in HYBAS-7 the total area that has been drained since 1850 for agriculture (that is, the sum of the five drivers: cropland, pasture, wetland cultivation, rice and peat extraction). In particular, this layer represents the maximum wetland restorable area under the Full Restoration scenario. In the other two scenarios, we limited such extent by imposing two different constraints. For the CAP 4% scenario, the maximum area that could be restored per sub-basin is the minimum between the wetland area converted to agriculture and 4% of current arable land. The latter threshold is based on the EU CAP that recommends member states devote a minimum share of at least 4% of arable land at farm level to non-productive areas and features, including land lying fallow. Here, we hypothesized that this 4% is dedicated entirely to wetland features. The third scenario, Farmland Abandonment, is more nuanced and leverages a recent estimate of agricultural land abandonment by 2040 due to social, economic and environmental factors49 in the EU27 and United Kingdom. Restoring wetlands only in areas where farmland is projected to be abandoned can provide opportunities for ecological and water quality improvement95,96 while not limiting agricultural productivity, given the low competition for other uses on these lands. Therefore, here we limited the maximum wetland area that could be restored by the information of projected farmland abandonment by 2040, which is around 16 Mha. Consequently, the maximum area that could be restored per sub-basin is the minimum between the wetland area converted to agriculture and the current farmland area likely to be abandoned by 2040. Note that in this latter case, information on projected farmland abandonment is available only at the EU27 + United Kingdom level.

Once these two inputs have been estimated, the restoration algorithm can be run. Such an algorithm starts assigning wetlands to those sub-basins that have a large share of N surplus. Thus, given a certain amount of area to be restored in the river basin, more weight, and thus more wetlands, would be dedicated to those units that already have high N surplus. The algorithm stops either when we reach the target reduction in riverine N load or when we hit the maximum area that can be restored.

Cost–benefit analysis

Assessing wetland restoration costs and benefits is not an easy task considering the different types of wetland that can be restored, their geographical location and their objectives. We leveraged different systematic reviews of studies that reported wetland restoration costs by type and have listed them in Extended Data Table 3. Then, starting from the current wetland distribution (see ‘Current wetland’), we computed the ratio of each wetland type by sub-basin. The following step involved multiplying the total area that should be restored in each sub-basin by the current wetland type ratio. This process was repeated for the three restoration scenarios. Here, there was a strong assumption that the past wetland-type distribution would be the same as the current one. Due to the different timings of the studies and their specific locations, all costs were computed in euros at 2020 rates (Table 1) and adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index.

We also estimated the economic value of ecosystem services provided by wetlands in agricultural landscapes following the meta-analysis proposed by Brander et al.97 and De Groot et al.98. Their studies examined the economic value of multiple wetland regulating services. For example, Brander et al.97 provide estimates for three critical regulating services, namely, flood control, water supply and nutrient recycling, as well as a database comprising 66 value estimates, predominantly from wetlands in the United States and Europe, but also including a significant number from developing countries. All values are standardized to euros per hectare per year. The mean values were determined to be €6,369 ha−1 yr−1 for flood control, €3,118 ha−1 yr−1 for water supply and €5,324 ha−1 yr−1 for nutrient recycling. These estimates were about an order of magnitude lower when the authors applied a meta-regression analysis to transfer values to wetland sites for which there is no value information available (see Table 4 in ref. 97). The total monetary value of the bundle of ecosystem services per inland wetland reported by De Groot et al.98 is almost twice the initial estimates of Brander et al.97, namely €26,140 ha−1 yr−1 versus €14,811 ha−1 yr−1. This larger value stems from the fact that De Groot et al.98 considered up to 22 ecosystem services. When limited to the same three services, the two values are comparable.

Here, we multiplied the total restored area for each restoration scenario by the two mean values estimated by Brander et al.97, and the mean value estimated by De Groot et al.98. The minimum and maximum values are reported in Table 1.

Peatlands restoration

The recently adopted NRL sets a target for the EU to restore at least 20% of the EU’s land and sea areas by 2030 and all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050. The EU NRL, agreed with member states, will restore degraded ecosystems in all member states, help to achieve the EU’s climate and biodiversity objectives, and enhance food security. To reach the overall EU targets, member states must restore at least 30% of habitats covered by the new law (from forests, grasslands and wetlands to rivers, lakes and coral beds) from a poor to a good condition by 2030, increasing to 60% by 2040 and 90% by 2050. Member states will also have to adopt national restoration plans detailing how they intend to achieve these targets.

In the context of wetland restoration, Article 11 of the NRL prescribes that “Member States shall put in place measures which shall aim to restore organic soils in agricultural use constituting drained peatlands. Those measures shall be in place on at least: (a) 30% of such areas by 2030, of which at least a quarter shall be rewetted; (b) 40% of such areas by 2040, of which at least a third shall be rewetted; (c) 50% of such areas by 2050, of which at least a third shall be rewetted.” 99.

Using our three restoration scenarios, we generated estimates for the proportion of peatlands subject to restoration efforts, facilitating a direct comparison with the objectives stipulated in the NRL. These findings are delineated in Extended Data Table 4 for each of the EU27 member states. The main limitation of our approach is that the restoration of wetlands within each watershed is assumed to reflect the current distribution of wetland types as recorded in the MAES database (Supplementary Fig. 1). This presupposes the continued presence of peatlands within the landscapes; however, where peatlands have been historically drained and are subsequently unreported in the current dataset, our approach would not account for their restoration. In addition, the Fluet-Chouinard et al.48 dataset lacks differentiation among various wetland types previously lost, compelling us to employ peatland drainage estimates from Tanneberger et al.79 and Joosten et al.78 as proxies for such loss.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Long-term annual soil nitrogen surplus data across Europe are available from Batool et al.45 and have been archived in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6581441. National and subnational statistics of drained or converted areas, regional wetland percentage loss estimates, and the gridded reconstruction of drained area per land use and cumulative as well as natural wetland area are available from Fluet-Chouinard et al.48 and have been archived in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7293597. The multidecadal time series of nutrient inputs and outputs in freshwaters and marine waters at the continental and regional scales are publicly available at the JRC Data Catalogue (https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset?q=wpi). The data on farmland abandonment developed by Fayet and Verburg49 are available at https://doi.org/10.34894/E5BQK0.

Code availability

RStudio (version 1.4.1717) was used for the present geospatial analysis and is available from the R Core Team (https://www.r-project.org/). The original codes for the estimation of current wetland N removal are available at https://github.com/landscape-ecohydrology/optimizing_wetland_restoration_in_nature. All other source codes are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Lu, C. & Tian, H. Global nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer use for agriculture production in the past half century: shifted hot spots and nutrient imbalance. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 181–192 (2017).

Bodirsky, B. et al. Reactive nitrogen requirements to feed the world in 2050 and potential to mitigate nitrogen pollution. Nat. Commun. 5, 3858 (2014).

Dentener, F. et al. Nitrogen and sulfur deposition on regional and global scales: a multimodel evaluation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 20, GB4003 (2006).

Zhang, X. et al. Quantification of global and national nitrogen budgets for crop production. Nat. Food 2, 529–540 (2021).

Diaz, R. J. & Rosenberg, R. Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science 321, 926–929 (2008).

Glibert, P. M. Eutrophication, harmful algae and biodiversity—challenging paradigms in a world of complex nutrient changes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 124, 591–606 (2017).

Erisman, J. W. et al. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20130116 (2013).

Bobbink, R. et al. Global assessment of nitrogen deposition effects on terrestrial plant diversity: a synthesis. Ecol. Appl. 20, 30–59 (2010).

Bleeker, A., Hicks, W. K., Dentener, F., Galloway, J. & Erisman, J. W. N deposition as a threat to the World’s protected areas under the Convention on Biological Diversity. Environ. Pollut. 159, 2280–2288 (2011).

Wang, M. et al. A triple increase in global river basins with water scarcity due to future pollution. Nat. Commun. 15, 880 (2024).

Basu, N. B. et al. Managing nitrogen legacies to accelerate water quality improvement. Nat. Geosci. 15, 97–105 (2022).

Council Directive 91/271/EEC Concerning Urban Waste-water Treatment (Official Journal of the European Union,1991); http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1991/271/oj.

Council Directive 91/676/EEC Concerning the Protection of Waters Against Pollution Caused by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources (Official Journal of theEuropean Union, 1991); http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1991/676/oj.

Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy (OfficialJournal of the European Union, 2000); http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj.

Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Marine EnvironmentalPolicy (Official Journal of the European Union, 2008); http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/56/oj.

Backer, H. et al. HELCOM Baltic Sea Action Plan–a regional programme of measures for the marine environment based on the Ecosystem Approach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 60, 642–649 (2010).

Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR Commission, 1992).

Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution (UNEP/MAP, 1976); https://www.unep.org/unepmap/who-we-are/contractingparties/barcelona-convention-and-amendments.

Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution (Black Sea Commission, 2020).

Is Europe Living Within the Limits of our Planet? An Assessment of Europe’s Environmental Footprints in Relation to Planetary Boundaries Vol. 10, 537187 (EEA and FOEN, 2020).

Nikolaidis, N. P. et al. River and lake nutrient targets that support ecological status: European scale gap analysis and strategies for the implementation of the Water Framework Directive. Sci. Total Environ. 813, 151898 (2022).

Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on the Implementation of Council Directive 91/676/EEC Concerning the Protection of Waters Against Pollution Caused by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources Based on Member State Reports for the Period 2016–2019 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2021).

European Commission. The European Green Deal (COM/2019/640 final) (2019); https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640.

Seddon, N. et al. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190120 (2020).

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of theRegions. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System (Official Journal of the European Union, 2020).

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of theRegions. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives (Official Journal of the European Union, 2020).

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of theRegions. Pathway to a Healthy Planet for All EU Action Plan: ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil’ (Official Journal of the European Union,2021).

Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration and amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869 (Text with EEArelevance) (Official Journal of the European Union, 2024).

Verhoeven, J. T., Arheimer, B., Yin, C. & Hefting, M. M. Regional and global concerns over wetlands and water quality. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 96–103 (2006).

Mitsch, W. J. et al. Reducing nitrogen loading to the Gulf of Mexico from the Mississippi River Basin: strategies to counter a persistent ecological problem: ecotechnology—the use of natural ecosystems to solve environmental problems—should be a part of efforts to shrink the zone of hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico. BioScience 51, 373–388 (2001).

Van Cleemput, O., Boeckx, P., Lindgren, P. E. & Tonderski, K. in Biology of the Nnitrogen Cycle 359–367 (Elsevier, 2007).

Land, M. et al. How effective are created or restored freshwater wetlands for nitrogen and phosphorus removal? A systematic review. Environ. Evid 5, 9 (2016).

Audet, J., Zak, D., Bidstrup, J. & Hoffmann, C. C. Nitrogen and phosphorus retention in Danish restored wetlands. Ambio 49, 324–336 (2020).

Zhang, W., Li, H., Xu, D. & Xia, T. Wetland destruction in a headwater river leads to disturbing decline of in-stream nitrogen removal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 2774–2785 (2024).

Arheimer, B. & Wittgren, H. B. Modelling nitrogen retention in potential wetlands at the catchment scale. Ecol. Eng. 19, 63–80 (2002).

Arheimer, B. & Pers, B. C. Lessons learned? Effects of nutrient reductions from constructing wetlands in 1996–2006 across Sweden. Ecol. Eng. 103, 404–414 (2017).

Singh, N. K. et al. Optimizing wetland restoration to improve water quality at a regional scale. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 064006 (2019).

Czuba, J. A., Hansen, A. T., Foufoula-Georgiou, E. & Finlay, J. C. Contextualizing wetlands within a river network to assess nitrate removal and inform watershed management. Water Resour. Res. 54, 1312–1337 (2018).

Hansen, A. T., Dolph, C. L., Foufoula-Georgiou, E. & Finlay, J. C. Contribution of wetlands to nitrate removal at the watershed scale. Nat. Geosci. 11, 127–132 (2018).

Cheng, F. Y., Van Meter, K. J., Byrnes, D. K. & Basu, N. B. Maximizing US nitrate removal through wetland protection and restoration. Nature 588, 625–630 (2020).

Zuidema, S., Wollheim, W. M., Kucharik, C. J. & Lammers, R. B. Existing wetland conservation programs miss nutrient reduction targets. PNAS Nexus 3, gae129 (2024).

Shen, W. et al. Size and temperature drive nutrient retention potential across water bodies in China. Water Res. 239, 120054 (2023).

Pistocchi, A. Nature-Based Solutions for Agricultural Water Management (Publications Office of the European Union, 2022); https://doi.org/10.2760/343927

Burek, P. et al. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Natural Water Retention Measures JRC Report (Publications Office of the European Union, 2012).

Batool, M. et al. Long-term annual soil nitrogen surplus across Europe (1850–2019). Sci. Data 9, 612 (2022).

Maes, J. et al. Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and Their Services: An EU Wide Ecosystem Assessment in Support of the EU Biodiversity Strategy (Publications Office of the European Union, 2020).

Cheng, F. Y. & Basu, N. B. Biogeochemical hotspots: role of small water bodies in landscape nutrient processing. Water Resour. Res. 53, 5038–5056 (2017).

Fluet-Chouinard, E. et al. Extensive global wetland loss over the past three centuries. Nature 614, 281–286 (2023).

Fayet, C. M. & Verburg, P. H. Modelling opportunities of potential European abandoned farmland to contribute to environmental policy targets. Catena 232, 107460 (2023).

Mitsch, W. J. & Gosselink, J. G. Wetlands (John wiley, 2015).

Dixon, M. J. R. et al. Tracking global change in ecosystem area: the Wetland Extent Trends index. Biol. Conserv. 193, 27–35 (2016).

Creed, I. F. et al. Enhancing protection for vulnerable waters. Nat. Geosci. 10, 809–815 (2017).

Verhoeven, J. T. Wetlands in Europe: perspectives for restoration of a lost paradise. Ecol. Eng. 66, 6–9 (2014).

Davidson, N. C. How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area. Mar. Freshw. Res. 65, 934–941 (2014).

Van Meter, K. J., Van Cappellen, P. & Basu, N. B. Legacy nitrogen may prevent achievement of water quality goals in the Gulf of Mexico. Science 360, 427–430 (2018).

Stoate, C. et al. Ecological impacts of early 21st century agricultural change in Europe—a review. J. Environ. Manage. 91, 22–46 (2009).

Glibert, P. M., Maranger, R., Sobota, D. J. & Bouwman, L. The Haber Bosch–harmful algal bloom (HB–HAB) link. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 105001 (2014).

Lassaletta, L., Billen, G., Grizzetti, B., Anglade, J. & Garnier, J. 50 year trends in nitrogen use efficiency of world cropping systems: the relationship between yield and nitrogen input to cropland. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 105011 (2014).

Ibisch, R. et al. European Assessment of Eutrophication Abatement Measures Across Land-Based Sources, Inland, Coastal and Marine Waters Technical Report 2/2016 (ETC/ICM, 2016).

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, 2017).

Sutton, M. A. et al. (eds) The European Nitrogen Assessment: Sources, Effects and Policy Perspectives (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

EEA Signals 2019—Land and Soil in Europe: Why We Need to Use These Vital and Finite Resources Sustainably (European Environment Agency, 2019); https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/eea-signals-2019-land

Capell, R. et al. From local measures to regional impacts: modelling changes in nutrient loads to the Baltic Sea. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud 36, 100867 (2021).

Gren, I. M. & Destouni, G. Does divergence of nutrient load measurements matter for successful mitigation of marine eutrophication? Ambio 41, 151–160 (2012).

Arheimer, B., Dahné, J. & Donnelly, C. Climate change impact on riverine nutrient load and land-based remedial measures of the Baltic Sea Action Plan. Ambio 41, 600–612 (2012).

Vigiak, O. et al. Recent regional changes in nutrient fluxes of European surface waters. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 160063 (2023).

Arheimer, B. & Wittgren, H. B. Modelling the effects of wetlands on regional nitrogen transport. Ambio 23, 378–386 (1994).

Arheimer, B., Löwgren, M., Pers, B. C. & Rosberg, J. Integrated catchment modeling for nutrient reduction: scenarios showing impacts, potential and cost of measures. Ambio 34, 513–520 (2005).

Morecroft, M. D. et al. Measuring the success of climate change adaptation and mitigation in terrestrial ecosystems. Science 366, eaaw9256 (2019).

Mitsch, W. J. et al. Wetlands, carbon, and climate change. Landsc. Ecol 28, 583–597 (2013).

Bridgham, S. D., Megonigal, J. P., Keller, J. K., Bliss, N. B. & Trettin, C. The carbon balance of North American wetlands. Wetlands 26, 889–916 (2006).

Temmerman, S. et al. Ecosystem-based coastal defence in the face of global change. Nature 504, 79–83 (2013).

Hefting, M. et al. Water table elevation controls on soil nitrogen cycling in riparian wetlands along a European climatic gradient. Biogeochemistry 67, 113–134 (2004).

De Groot, R. S., Wilson, M. A. & Boumans, R. M. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 41, 393–408 (2002).

Acreman, M. & Holden, J. How wetlands affect floods. Wetlands 33, 773–786 (2013).

Gibbs, J. P. Wetland loss and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 14, 314–317 (2000).

Bertassello, L. E. et al. Persistence of amphibian metapopulation occupancy in dynamic wetlandscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 37, 695–711 (2022).

Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F. & Moen, A. Mires and Peatlands of Europe: Status, Distribution and Conservation (Schweizerbart, 2017).

Tanneberger, F. et al. Mires in Europe—regional diversity, condition and protection. Diversity 13, 381 (2021).

Hering, D. et al. Securing success for the Nature Restoration Law. Science 382, 1248–1250 (2023).

Farley, J. & Costanza, R. Payments for ecosystem services: from local to global. Ecol. Econ. 69, 2060–2068 (2010).

Jordan, S. J., Stoffer, J. & Nestlerode, J. A. Wetlands as sinks for reactive nitrogen at continental and global scales: a metaanalysis. Ecosystems 14, 144–155 (2011).

European Environment Agency. Extended wetland ecosystem layer (European Environment Agency, 2018); https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-andmaps/data/extended-wetland-ecosystem-layer/folder_contents.

Gardner, R. C., & Finlayson, C. Global wetland outlook: state of the world’s wetlands and their services to people. In Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2020–2025 (2018)

Barton, L., McLay, C. D. A., Schipper, L. A. & Smith, C. T. Annual denitrification rates in agricultural and forest soils: a review. Soil Res. 37, 1073–1094 (1999).

Hayashi, M., van der Kamp, G. & Rosenberry, D. O. Hydrology of prairie wetlands: understanding the integrated surface-water and groundwater processes. Wetlands 36, 237–254 (2016).

Wu, Q. & Lane, C. R. Delineating wetland catchments and modeling hydrologic connectivity using lidar data and aerial imagery. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 3579–3595 (2017).

European Environment Agency (EEA). Waterbase - Water Quality ICM (European Environment Agency, 2019); https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-andmaps/data/waterbase-water-quality-icm.

De Roo, A. et al. The water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus in the Mediterranean: current issues and future challenges. Front. Clim. 3, 782553 (2021).

Grizzetti, B., Bouraoui, F. & Aloe, A. Changes of nitrogen and phosphorus loads to European seas. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 769–782 (2012).

Grizzetti, B. et al. How EU policies could reduce nutrient pollution in European inland and coastal waters. Glob. Environ. Change 69, 102281 (2021).

Udías, A. et al. GREENeR: an R package to estimate and visualize nutrients pressures on surface waters (2023); https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/GREENeR/index.html.

Vogt, J. V. et al. A Pan-European River and Catchment Database JRC Report EUR 22920 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2007).

Vogt, J., Rimaviciute, E. & de Jager, A. CCM2 River and Catchment Database for Europe Version 2.1 Release Notes (Institute for Environment and Sustainability, Joint Research Centre, European Commission, 2008).