Abstract

Nitrofurantoin has shown exceptional durability against resistance over 70 years of use. This longevity stems from factors such as rapid achievement of therapeutic concentrations, multiple physiological targets against bacteria, low risk of horizontal gene transfer, and the need to acquire multiple mutations to achieve resistance. These combined features limit resistance emergence and spread of nitrofurantoin resistance. We propose nitrofurantoin as an exemplar for developing other durable treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

The escalating spread of antimicrobial resistance poses a considerable challenge to global public health. For the majority of antibiotics, resistance usually emerges within a decade of its first clinical use1. However, nitrofurantoin stands out as an exception to this trend, as rates of resistance have remained low, despite high frequency of usage as a treatment for urinary tract infections (UTIs)2. Lessons learned from nitrofurantoin’s robustness could prove useful in the attempt to develop other antibiotic treatment strategies that are durable against resistance.

Nitrofurantoin is a synthetic antibiotic, originally patented in 1952 by Eaton Laboratories in Norwich, New York, USA. It first entered clinical use in 1953 and was marketed under the brand names Furadantin, Macrobid, and Macrodantin3. Though its mechanism of action was not completely understood at the time, it was known to affect metabolism through inhibition of bacterial enzymes and to interfere with cell wall synthesis, among other effects. Nitrofurantoin’s broad-spectrum activity against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, including common uropathogens Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterococcus spp., and Staphylococcus spp., made it particularly effective, and it quickly became widely used for the treatment of uncomplicated UTIs4. However, some less common uropathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Proteus spp., were recognised to be intrinsically resistant5.

Today nitrofurantoin is one of the most prescribed treatments for UTIs. Nitrofurantoin is included on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines6, and its empirical use is encouraged through inclusion in the Access group of The WHO AWaRe antibiotic book7. In 2016, English prescribing guidelines switched from trimethoprim to nitrofurantoin as the first-choice antibiotic for the treatment of lower urinary tract infections in the community context8. Prescription data in England shows a steady rise in nitrofurantoin prescription, climbing from 35.3% in 2016 to 73.1% in 2023, coupled with a reduction in trimethoprim use (Fig. 1A)9. In real terms, the average number of nitrofurantoin prescriptions effectively doubled between 2015 and 2020 (2.1 vs. 4.2 million prescriptions/year), remaining relatively constant since. Over the same period, there has been a slow but steady decline in the frequency of E. coli isolates with trimethoprim resistance without a corresponding increase in nitrofurantoin resistance, which has hovered around 2.5% for E. coli and coliform isolates sampled from community populations (Fig. 1B). A statistical model relating resistance to antibiotic, date and their interaction is a good fit to the data (overall fit of linear regression: adjusted R2 = 0.98, F3,68 = 1307, p < 0.0001). There is only a significant relationship with date for trimethoprim resistance (interaction effect = −1.8 × 10−5 ± 0.37 × 10−5 S.E., t1 = −4.9, p < 0.00001).

A Count of nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim prescriptions. B Resistance to nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim in E. coli and other coliforms isolated from urine. Vertical dashed lines in A and B indicate date of switch to nitrofurantoin as first-choice antibiotic. C Resistance and nitrofurantoin prescribing for each of the 42 healthcare regions in England (Integrated Care Boards, ICBs), averaged across the twelve-month period ending in December 2023 (grey areas denote 95% confidence interval for the linear regression; clipped symbols at the bottom of the plot denote ICBs with 0% recorded resistance). Data from the UK Office for Health Improvement and Disparities Fingertips data collection9.

While there is variation within geographic regions in the UK for nitrofurantoin prescribing (62.7–82.6%, relative to trimethoprim prescription) and resistance (0–30%), there is little relationship between the two. A statistical model relating nitrofurantoin resistance to prescribing rates does not describe the data well (overall fit of linear regression: adjusted R2 = 0.01, F1,85 = 1.8, p = 0.18), and there is no significant association between nitrofurantoin prescribing and resistance (slope = −2.2 × 10−5 ± 1.6 × 10−5 S.E., t1 = −1.35, p = 0.18, Fig. 1C). Similar nitrofurantoin resistance rates and patterns are seen globally10,11,12, though are on average higher in the United States (>20%13). This is in stark contrast to many other antibiotics, where rates of prescription or use correlate, often strongly, with resistance rates14,15,16,17.

An antibiotic with enduringly low rates of resistance amid increasing rates of prescription is of great interest in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. Understanding the mechanisms behind the surprising success of nitrofurantoin could help preserve it as an effective treatment and also aid in the development of new antibiotic compounds or treatment approaches that minimise resistance. We argue that several aspects of nitrofurantoin contribute to its durability against resistance evolution.

Properties of nitrofurantoin contributing to its durability against resistance

Rapid achievement of therapeutic concentrations specific to the site of infection

The favourable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) properties of nitrofurantoin treatment likely aid the suppression of resistance evolution18,19,20,21,22, as resistance has been experimentally demonstrated to evolve faster at low concentrations23. High therapeutic concentrations of nitrofurantoin are rapidly achieved, and specific to the site of infection in the urinary tract. After oral administration, nitrofurantoin is rapidly excreted unchanged in the urine, achieving concentrations of over 200 μg/ml3—well above the mutant prevention concentration of 64 μg/ml24. This allows nitrofurantoin to effectively kill bacteria in the urinary tract before the emergence of de novo-resistant mutants. Exploiting collateral sensitivity could further enhance killing, as mutants resistant to several antibiotics have increased susceptibility to nitrofurantoin25,26. In contrast, antibiotics that do not rapidly achieve high localised concentrations at the site of infection are more vulnerable to the development of resistance, as susceptible strains can proliferate and accumulate resistance mutations before the antibiotic reaches inhibitory concentrations. The rapid increase in concentrations impedes evolution particularly well when clinical resistance to a drug requires stepwise accumulation of multiple mutations—as is the case for nitrofurantoin27.

Low off-target concentrations

Nitrofurantoin rapidly achieves therapeutic concentrations at the site of infection (i.e. the bladder), with low off-target concentrations. While it achieves concentrations of over 200 μg/ml in urine3, concentrations in other bodily fluids are much lower; for example, typical plasma levels are less than 1 μg/ml, which is below the concentration needed to select for antimicrobial resistance mutations24. Nitrofurantoin is rapidly absorbed from the small intestine20, with only 2% of the dose recovered in faeces in a rat model28. This low concentration in the gut reduces the selection pressure for resistance within the microbiome, which can otherwise serve as a reservoir for resistant strains29. As a result, nitrofurantoin-resistant organisms are only rarely isolated from faeces30,31. Nitrofurantoin also does not cause dysbiosis of the normal intestinal microbiome32,33, a state that can result in increased colonisation by pathogenic organisms.

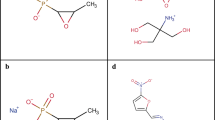

Multifactorial mechanism of action on bacterial physiology

An aspect of nitrofurantoin’s robustness against antibiotic resistance development likely stems from its multifactorial mechanism of action. Nitrofurantoin itself is not directly bactericidal; its activity requires the reduction of the nitro group in its molecular structure by bacterial nitroreductases after uptake into the cell34. This generates reactive intermediates that target multiple vital metabolic processes, such as protein synthesis, the citric acid cycle, and DNA/RNA synthesis3,35. These multifactorial effects within bacteria make resistance development highly complex and difficult to achieve, as changes (through mutations) to multiple mechanisms are required to concurrently overcome each damaging effect3.

Requirement for multiple independent mutations for clinical resistance

As nitrofurantoin’s mechanism of action involves several different bacterial nitroreductases, including NfsA and NfsB36, de novo resistance emergence requires changes to multiple targets. Separate inactivating mutations in both nfsA and nfsB are typically required for clinical levels of resistance and, indeed, are observed in clinically resistant organisms24,37,38. Crucially, the inactivation of just one out of nfsA and nfsB confers only a small increase in the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)24. Coupled with the favourable PK/PD properties of nitrofurantoin, this reduces the probability of resistance emerging via stepwise loss of nfsA and nfsB.

A single large deletion mutation that simultaneously inactivates both nfsA and nfsB is likewise an unlikely route to acquiring resistance. Despite being functionally similar, nfsA and nfsB are located far apart within the genome. In the type strain E. coli str. K-12, the distance between the two genes is 287 kbp24 (ranging between 262–337 kbp in other isolates); this genomic region contains 260 genes, of which 16 are identified as essential39. A genomic deletion inactivating both simultaneous genes would, therefore, likely be non-viable.

The proper functioning of nitroreductases is also dependent on other genes, including ribE, which is required to produce co-factors used by NfsA and NfsB. Inactivating mutations in ribE can also give rise to some degree of resistance37,40, but frequencies of ribE mutations among nitrofurantoin-resistant clinical isolates are low and are not found without nfsA and nfsB mutations36, suggesting other factors may constrain its contribution to resistance in vivo. Notably, intrinsically resistant organisms inherently lack the specific nitroreductases that convert nitrofurantoin into its active form5.

Fitness costs associated with resistance mutations

Fitness costs imposed by resistance mutations in the absence of antibiotics may contribute to an antibiotic’s durability. When antibiotic treatment is withdrawn, resistant organisms have a reduced ability to disseminate and establish infections. While nitrofurantoin resistance has been shown to impose a fitness cost, the extent and significance of this cost are debated. A recent study on clinical isolates found a 2–10% reduction in growth rate, though the results were not statistically significant24. An earlier study reported an average 6% reduction, with some isolates experiencing considerably higher costs41. Experimental studies have demonstrated up to a 10% reduction in competitive fitness, though this cost was able to be mitigated through compensatory adaptation42. However, it is important to note that these fitness costs were measured in vitro. To fully understand the implications of resistance, fitness costs should be assessed in vivo, where environmental and host factors may influence outcomes.

Resistance typically emerges due to mutations rather than horizontal gene transfer

For many antibiotics where resistance has become common, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is the major route to resistance acquisition. This often involves antibiotic-inactivating enzymes, target bypass genes, or novel efflux pumps43. Such genes are often carried on mobile genetic elements like plasmids or integrons, or acquired through natural transformation, all of which facilitate spread between species44,45. Unlike many other antibiotics in common use, the first two resistance mechanisms play only a small part in nitrofurantoin resistance. There are limited reports of nitrofurantoin-inactivating enzymes in clinical isolates46, although the presence of nitrofurantoin-degrading enzymes in natural isolates suggests that horizontal gene transfer could eventually allow pathogens to acquire these resistance mechanisms47. Target bypass is unlikely to result in nitrofurantoin resistance, given that its mechanism of action does not rely on inhibiting a specific gene target. Recombination is also unlikely to transfer resistance because, as previously mentioned, the genomic region between the nfsA and nfsB is large24.

In contrast, the HGT of a novel multi-drug efflux pump, OqxAB, has been linked to nitrofurantoin resistance48. OqxAB was first detected in E. coli from pigs from Denmark49,50, and is associated with the feed additive olaquindox, which had been in use from the 1980s until an EU-wide ban in 1999. oqxAB was found to be carried on a conjugative plasmid (the IncX1-type plasmid pOLA5251), which has facilitated its spread between different bacteria. oqxAB is now carried by a variety of mobile genetic elements capable of transmitting between strains. The prevalence of oqxAB can exceed 50% in animal isolates from regions where olaquindox remains in use (including Australia52 and China53,54). In human isolates, prevalence ranges from 0.4–42%54, but is higher in regions using olaquindox, particularly among farmworkers55. Though OqxAB on its own confers only a modest increase in nitrofurantoin MIC, when combined with a nfsA mutation, it can confer resistance above the clinical breakpoint48. Work in other organisms has shown that the acquisition of novel efflux pumps can increase the potential for high-level resistance to evolve by allowing additional time for resistance mutations to emerge56. The potential for OqxAB to act as a similar “stepping stone” to full nitrofurantoin resistance in clinical isolates should be assessed.

The reduced role of HGT in nitrofurantoin resistance may be a fortunate consequence of its synthetic origins. Being a fully synthetic compound, nitrofurantoin likely lacks a natural reservoir of resistance genes. Many antibiotics in common use are derived from compounds originally produced by microbes and may have initially evolved for microbe-microbe competition57. Genes for synthesising antibiotics are evolutionarily ancient58,59—certainly long predating anthropogenic use of antibiotics60, and often contemporaneous with major evolutionary events59. Consequently, there has been an “arms race” between the evolution of antibiotic synthesis genes and antibiotic resistance genes that have been running for millions of years61. Consequently, in some cases, resistance to an antibiotic is already present in bacterial populations before its introduction into commercial use62. The use of fully synthetic antibiotics may help reduce resistance, to a degree63. However, not all synthetic antibiotics are inherently durable against resistance evolution; other synthetic antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim, exhibit significantly higher resistance64,65,66,67.

Insights into factors promoting nitrofurantoin resistance

Despite many properties favouring its durability against resistance evolution, nitrofurantoin resistance does emerge in both experimental and clinical contexts. Insight into how and why nitrofurantoin resistance does emerge can help ensure its continued efficacy.

While full nitrofurantoin resistance imposes a fitness cost in the absence of the drug24,41, the acquisition of an initial inactivating mutation in nfsA or nfsB can be selectively advantageous at sub-inhibitory nitrofurantoin concentrations, even without significantly changing the MIC24. Intriguingly, when resistance has been observed to arise in vitro, mutations tended to arise first in nfsA, followed by mutations in nfsB, due to the larger fitness benefits conferred by loss of nfsA under sub-inhibitory concentrations24.

Treatment noncompliance could play a significant role in contributing to nitrofurantoin resistance. As subinhibitory nitrofurantoin concentrations can facilitate resistance23,41, non-adherence with treatment regimens could allow these first-step mutants to proliferate and acquire second-step mutations. Ensuring consistent nitrofurantoin levels through full adherence is crucial to preventing the development of resistance. A patient-focused intervention emphasising the importance of adherence could help preserve the efficacy of nitrofurantoin, benefiting both the individual patient and the broader community by reducing the risk of resistance development and maintaining effective treatment options.

The use of antibiotics as prophylactics is a potential risk factor for increasing the prevalence of antibiotic resistance. Prophylactic use can expose bacteria to sub-therapeutic levels of antibiotics, promoting the selection and spread of resistant strains68. Existing evidence suggests the risk of nitrofurantoin resistance developing during prophylaxis is relatively low. A meta-analysis of controlled trials has shown that rates of nitrofurantoin resistance reported during trials were low69. In one study, nitrofurantoin prophylaxis did not increase resistance in children with urinary tract abnormalities70. However, a second study observed that E. coli was often replaced by resistant Klebsiella spp. and (intrinsically) resistant Pseudomonas spp71. Low-dose prophylaxis in adult women has generally shown low resistance rates72,73, although one study found nitrofurantoin prophylaxis increased resistance frequency relative to control (24% vs. 9%74). Generally, nitrofurantoin had lower resistance rates than alternative antibiotics72,73,74. While current evidence suggests prophylaxis poses a low risk for nitrofurantoin resistance, continued surveillance is recommended, given the emergence of new resistance mechanisms46,48,49,54.

A problematic development is the rise of nitrofurantoin resistance alongside multi-drug resistant (MDR) and extensively-drug resistant (XDR) isolates, particularly among the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). High-level nitrofurantoin resistance in CRE presents significant clinical challenges, complicating the treatment of UTIs. Nitrofurantoin-resistant E. coli isolates from the UK are more likely to also be MDR or XDR, compared to susceptible isolates75. Nitrofurantoin resistance is also found in non-E. coli CRE, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp. (including E. cloacae), Citrobacter freundii and others37,76. In addition to typical mutations in nfsA and nfsB, overexpression of efflux pumps37,77, and reduced drug uptake due to disruption of outer membrane porins77 likely contribute to nitrofurantoin resistance in CRE. The association between nitrofurantoin resistance and CRE is especially concerning, as nitrofurantoin has been reintroduced alongside carbapenems and colistin to counter multi-drug resistant infections76.

Other genomic and environmental factors affecting the evolvability of nitrofurantoin resistance warrant consideration. Recent experimental work has shown that “mutators” with defects in DNA replication fidelity can more easily acquire stepwise resistance mutations78,79 and overcome fitness deficits through compensatory adaptation80. Mutators pose a specific risk for nitrofurantoin resistance, increasing both the probability of resistance evolution and the specificity of resistance mutations81. The increasing prevalence of OqxAB efflux pumps also provides a potential mechanism that may make high-level nitrofurantoin resistance easier to evolve. The case of OqxAB, which was selected for in response to a different compound, also emphasises the need to better test for potential cross-resistance between existing and new drugs and chemicals prior to their release on the market.

Despite an increasing frequency of usage, nitrofurantoin has remained a durable antibiotic option for treating urinary tract infections. This durability is likely due to a few key factors, including targeted delivery to the site of infection and favourable PK/PD properties, multitarget effects on bacterial physiology, a requirement for multiple independent mutations for resistance to be acquired, fitness costs associated with resistance in the absence of nitrofurantoin, and the near-absence of horizontally acquired resistance. Continued judicious use of nitrofurantoin will hopefully continue to preserve this important antibiotic option for treating UTIs in the face of increasing antimicrobial resistance. However, more insight needs to be gained about factors that can increase the evolvability of nitrofurantoin resistance, including treatment non-adherence, the use of nitrofurantoin as a prophylactic treatment for recurrent UTI, bacterial mutation rate evolution, and the horizontal acquisition of novel efflux pumps. More generally, insight into mechanisms favouring the durability of nitrofurantoin may prove useful in the development of other durable antibiotics and treatment options.

Data availability

The datasets used are from the AMR Local Indicators datasets produced by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), which can be accessed via the UK Office for Health Improvement and Disparities Fingertips public health data portal (https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/). Prescribing data is taken from indicator ID 92511. Data on nitrofurantoin resistance in urine specimens is taken from indicator ID 92521. Data on trimethoprim resistance in urine specimens is taken from indicator ID 92519. The data were analysed in R using a custom script, provided as Supplementary File S1.

References

Palumbi, S. R. Humans as the world’s greatest evolutionary force. Science 293, 1786–1790 (2001).

Mahdizade Ari, M. et al. Nitrofurantoin: properties and potential in treatment of urinary tract infection: a narrative review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1148603 (2023).

Blass, B. E. in Basic Principles of Drug Discovery and Development (Second Edition) (ed. Blass, B. E.) 625–664 (Academic Press, 2021).

Hasen, H. B. & Moore, T. D. Nitrofurantoin: a study in vitro and in vivo in one hundred cases of urinary infection. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 155, 1470–1473 (1954).

Richards, W. A., Riss, E., Kass, E. H. & Finland, M. Nitrofurantoin: clinical and laboratory studies in urinary tract infections. AMA Arch. Intern. Med. 96, 437–450 (1955).

WHO. WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines. https://www.who.int/groups/expert-committee-on-selection-and-use-of-essential-medicines/essential-medicines-lists (2023).

WHO. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240062382 (2022).

NHS England. Technical Guidance for Refreshing NHS Plans 2018/19 Annex B: Information on Quality Premium (NHS England). (2018).

Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. AMR Local Indicators (Fingertips Public Health Data) (Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, 2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Unravelling mechanisms of nitrofurantoin resistance and epidemiological characteristics among Escherichia coli clinical isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 52, 226–232 (2018).

Sugianli, A. K. et al. Antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens in the Asia-pacific region: a systematic review. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 3, dlab003 (2021).

Walkty, A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacterial pathogens recovered from the urine of patients at Canadian hospitals from 2009 to 2020. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 4, dlac122 (2022).

Aronin, S. I., Gupta, V., Dunne, M. W., Watts, J. A. & Yu, K. C. Regional differences in antibiotic-resistant enterobacterales urine isolates in the United States: 2018-2020. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 119, 142–145 (2022).

Costelloe, C., Metcalfe, C., Lovering, A., Mant, D. & Hay, A. D. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 340, c2096 (2010).

Olesen, S. W. et al. The distribution of antibiotic use and its association with antibiotic resistance. eLife 7, e39435 (2018).

Goossens, H., Ferech, M., Stichele, R. V. & Elseviers, M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 365, 579–587 (2005).

Kim, B. et al. Trends and correlation between antibiotic usage and resistance pattern among hospitalized patients at university hospitals in Korea, 2004 to 2012. Medicine 97, e13719 (2018).

Olofsson, S. K. & Cars, O. Optimizing drug exposure to minimize selection of antibiotic resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45, S129–S136 (2007).

Fransen, F., Melchers, M. J. B., Lagarde, C. M. C., Meletiadis, J. & Mouton, J. W. Pharmacodynamics of nitrofurantoin at different pH levels against pathogens involved in urinary tract infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 3366–3373 (2017).

Wijma, R. A., Huttner, A., Koch, B. C. P., Mouton, J. W. & Muller, A. E. Review of the pharmacokinetic properties of nitrofurantoin and nitroxoline. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 2916–2926 (2018).

Wijma, R. A., Fransen, F., Muller, A. E. & Mouton, J. W. Optimizing dosing of nitrofurantoin from a PK/PD point of view: what do we need to know?. Drug Resist. Updat. 43, 1–9 (2019).

Maaland, M. G., Jakobsen, L., Guardabassi, L. & Frimodt-Møller, N. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of nitrofurantoin against Escherichia coli in a murine urinary tract infection model. APMIS 132, 492–498 (2024).

Lagator, M., Uecker, H. & Neve, P. Adaptation at different points along antibiotic concentration gradients. Biol. Lett. 17, 20200913 (2020).

Vallée, M., Harding, C., Hall, J., Aldridge, P. D. & Tan, A. Exploring the in situ evolution of nitrofurantoin resistance in clinically derived uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 78, 373–379 (2023).

Roemhild, R., Linkevicius, M. & Andersson, D. I. Molecular mechanisms of collateral sensitivity to the antibiotic nitrofurantoin. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000612 (2020).

Podnecky, N. L. et al. Conserved collateral antibiotic susceptibility networks in diverse clinical strains of Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 9, 3673 (2018).

Igler, C., Rolff, J. & Regoes, R. Multi-step vs. single-step resistance evolution under different drugs, pharmacokinetics, and treatment regimens. eLife 10, e64116 (2021).

Paul, M. F. et al. Studies on the distribution and excretion of certain nitrofurans. Antibiot. Chemother. Northfield Ill 10, 287–302 (1960).

Anthony, W. E., Burnham, C.-A. D., Dantas, G. & Kwon, J. H. The gut microbiome as a reservoir for antimicrobial resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 223, S209–S213 (2021).

Calva, J. J., Sifuentes-Osornio, J. & Cerón, C. Antimicrobial resistance in fecal flora: longitudinal community-based surveillance of children from urban Mexico. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 1699–1702 (1996).

Heijer, C. D. J., den, Beerepoot, M. A. J., Prins, J. M., Geerlings, S. E. & Stobberingh, E. E. Determinants of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli strains isolated from faeces and urine of women with recurrent urinary tract infections. PLoS ONE 7, e49909 (2012).

Vervoort, J. et al. Metagenomic analysis of the impact of nitrofurantoin treatment on the human faecal microbiota. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 1989–1992 (2015).

Elvers, K. T. et al. Antibiotic-induced changes in the human gut microbiota for the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in primary care in the UK: a systematic review. BMJ Open 10, e035677 (2020).

Le, V. V. H. & Rakonjac, J. Nitrofurans: revival of an “old” drug class in the fight against antibiotic resistance. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009663 (2021).

McOsker, C. C. & Fitzpatrick, P. M. Nitrofurantoin: mechanism of action and implications for resistance development in common uropathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33, 23–30 (1994).

Wan, Y. et al. Alterations in chromosomal genes nfsA, nfsB, and ribE are associated with nitrofurantoin resistance in Escherichia coli from the United Kingdom. Microb. Genomics 7, 000702 (2021).

Osei Sekyere, J. Genomic insights into nitrofurantoin resistance mechanisms and epidemiology in clinical Enterobacteriaceae. Future Sci. OA 4, FSO293 (2018).

Dulyayangkul, P. et al. Improving nitrofurantoin resistance prediction in Escherichia coli from whole-genome sequence by integrating NfsA/B enzyme assays. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 68, https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00242-24 (2024).

Goodall, E. C. A. et al. The essential genome of Escherichia coli K-12. mBio 9, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02096-17 (2018).

Vervoort, J. et al. An in vitro deletion in ribE encoding lumazine synthase contributes to nitrofurantoin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 7225–7233 (2014).

Sandegren, L., Lindqvist, A., Kahlmeter, G. & Andersson, D. I. Nitrofurantoin resistance mechanism and fitness cost in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62, 495–503 (2008).

Dunai, A. et al. Rapid decline of bacterial drug-resistance in an antibiotic-free environment through phenotypic reversion. eLife 8, e47088 (2019).

Darby, E. M. et al. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance revisited. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 280–295 (2023).

Partridge, S. R., Kwong, S. M., Firth, N. & Jensen, S. O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, e00088–17 (2018).

Khedkar, S. et al. Landscape of mobile genetic elements and their antibiotic resistance cargo in prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 3155–3168 (2022).

Edowik, Y., Caspari, T. & Williams, H. M. The amino acid changes T55A, A273P and R277C in the beta-lactamase CTX-M-14 render E. coli resistant to the antibiotic nitrofurantoin, a first-line treatment of urinary tract infections. Microorganisms 8, 1983 (2020).

Pacholak, A., Smułek, W., Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A. & Kaczorek, E. Nitrofurantoin—microbial degradation and interactions with environmental bacterial strains. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 16, 1526 (2019).

Ho, P.-L. et al. Plasmid-mediated OqxAB is an important mechanism for nitrofurantoin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 537–543 (2015).

Hansen, L. H., Sørensen, S. J., Jørgensen, H. S. & Jensen, L. B. The prevalence of the OqxAB multidrug efflux pump amongst olaquindox-resistant Escherichia coli in pigs. Microb. Drug Resist. 11, 378–382 (2005).

Sørensen, A. H., Hansen, L. H., Johannesen, E. & Sørensen, S. J. Conjugative plasmid conferring resistance to olaquindox. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 798–799 (2003).

Norman, A., Hansen, L. H., She, Q. & Sørensen, S. J. Nucleotide sequence of pOLA52: a conjugative IncX1 plasmid from Escherichia coli which enables biofilm formation and multidrug efflux. Plasmid 60, 59–74 (2008).

Dixit, O. V. A., Behruznia, M., Preuss, A. L. & O’Brien, C. L. Diversity of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria isolated from Australian chicken and pork meat. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1347597 (2024).

Yang, S.-S. et al. Prevalence of the oqxAB drug resistance gene in Escherichia coli of pig origin in Fujian. Chin. J. Zoonoses 39, 185–191 (2023).

Li, J. et al. The nature and epidemiology of OqxAB, a multidrug efflux pump. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 8, 44 (2019).

Zhao, J. et al. Prevalence and dissemination of oqxAB in Escherichia coli Isolates from animals, farmworkers, and the environment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4219–4224 (2010).

Papkou, A., Hedge, J., Kapel, N., Young, B. & MacLean, R. C. Efflux pump activity potentiates the evolution of antibiotic resistance across S. aureus isolates. Nat. Commun. 11, 3970 (2020).

Katz, L. & Baltz, R. H. Natural product discovery: past, present, and future. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 43, 155–176 (2016).

Aminov, R. I. A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Front. Microbiol. 1, 134 (2010).

Perry, J., Waglechner, N. & Wright, G. The prehistory of antibiotic resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, a025197 (2016).

Vos, M. The evolution of bacterial pathogens in the Anthropocene. Infect. Genet. Evol. 86, 104611 (2020).

Aminov, R. I. & Mackie, R. I. Evolution and ecology of antibiotic resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 271, 147–161 (2007).

Srinivas, K. et al. Occurrence of antimicrobial resistance genes prior to approval of antibiotics for clinical use: evidences from comparative resistome analysis of Salmonella enterica spanning four decades. Explor. Anim. Med. Res. 13, 71–84 (2023).

Wright, P. M., Seiple, I. B. & Myers, A. G. The evolving role of chemical synthesis in antibacterial drug discovery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 8840–8869 (2014).

Dalhoff, A. Global fluoroquinolone resistance epidemiology and implications for clinical use. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2012, 976273 (2012).

Faine, B. A. et al. High prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant UTI among US emergency department patients diagnosed with urinary tract infection, 2018–2020. Acad. Emerg. Med. 29, 1096–1105 (2022).

Nji, E. et al. High prevalence of antibiotic resistance in commensal Escherichia coli from healthy human sources in community settings. Sci. Rep. 11, 3372 (2021).

Wróbel, A., Arciszewska, K., Maliszewski, D. & Drozdowska, D. Trimethoprim and other nonclassical antifolates an excellent template for searching modifications of dihydrofolate reductase enzyme inhibitors. J. Antibiot. 73, 5–27 (2020).

Menz, B. D. et al. Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in an era of antibiotic resistance: Common resistant bacteria and wider considerations for practice. Infect. Drug Resist. 14, 5235–5252 (2021).

Muller, A. E., Verhaegh, E. M., Harbarth, S., Mouton, J. W. & Huttner, A. Nitrofurantoin’s efficacy and safety as prophylaxis for urinary tract infections: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 23, 355–362 (2017).

Schlager, T. A., Anderson, S., Trudell, J. & Hendley, J. O. Nitrofurantoin prophylaxis for bacteriuria and urinary tract infection in children with neurogenic bladder on intermittent catheterization. J. Pediatr. 132, 704–708 (1998).

Das, S. et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis is associated with subsequent resistant infections in children with an initial extended-spectrum-cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.02656-16 (2017).

Brumfitt, W. & Hamilton-Miller, J. M. A comparative trial of low dose cefaclor and macrocrystalline nitrofurantoin in the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Infection 23, 98–102 (1995).

Harding, C. et al. Alternative to prophylactic antibiotics for the treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: multicentre, open label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. BMJ 376, e068229 (2022).

Fisher, H. et al. Continuous low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis for adults with repeated urinary tract infections (AnTIC): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 957–968 (2018).

Guy, R. L. et al. Nitrofurantoin resistance as an indicator for multidrug resistance: an assessment of Escherichia coli urinary tract specimens in England, 2015–19. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 5, dlad122 (2023).

Loose, M., Link, I., Naber, K. G. & Wagenlehner, F. M. E. Carbapenem-containing combination antibiotic therapy against carbapenem-resistant uropathogenic Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e01839–19 (2019).

Hussein, M. et al. High-level nitrofurantoin resistance in a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae: a comparative genomics and metabolomics analysis. mSystems 9, e00972–23 (2023).

Gifford, D. R. et al. Mutators can drive the evolution of multi-resistance to antibiotics. PLoS Genet. 19, e1010791 (2023).

Elgrail, M. M., Sprouffske, K., Dartey, J. O. & Garcia, A. M. Emergence of a multilocus mutator genotype in mutator Escherichia coli experimental populations under repeated lethal selection. J. Evol. Biol. 37, 346–352 (2024).

Perron, G. G., Hall, A. R. & Buckling, A. Hypermutability and compensatory adaptation in antibiotic‐resistant bacteria. Am. Nat. 176, 303–311 (2010).

Kettlewell, R., Forsyth, J. H. & Gifford, D. R. Evolutionary risk analysis of mutators for the development of nitrofurantoin resistance. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.07.616996 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Academy of Medical Sciences (Springboard Grant SBF007\100096 to DRG), BBSRC (BB/X007979/1 to DRG) and Wellcome Trust, and the Royal Society Sir Henry Dale Fellowship (216779/Z/19/Z to M.L.). T.W.F. is supported by the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203308). D.R.G. wishes to thank Professor Tim Barraclough, Dr. Joris Alkemade, Dr. Nichola J Hawkins, and the Calleva Research Centre for organising the workshop “Evolutionary and genomic design principles for durable genetic control of fungal crop pathogens”, during which these ideas were refined. D.R.G. also thanks Professor Austin Burt for comments that inspired some sections of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: D.R.G. Data analysis: D.R.G. Review of the literature: R.K., C.J. Initial manuscript draft: R.K., C.J., D.R.G. Major contributions to writing: T.W.F., M.L. Edited and approved the final manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kettlewell, R., Jones, C., Felton, T.W. et al. Insights into durability against resistance from the antibiotic nitrofurantoin. npj Antimicrob Resist 2, 41 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44259-024-00056-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44259-024-00056-1