Abstract

Words of estimative probability (WEPs), such as “maybe” or “probably not” are ubiquitous in natural language for communicating estimative uncertainty. In linguistics, WEPs are hypothesized to have special (probabilistic) semantics, and their calibration with numerical estimates has long been an area of study. Motivated by increasing usage of large language models (LLMs) in applications requiring robust communication of uncertainty, this article studies how divergences in interpreting WEP between humans and LLMs reveal the limits of statistical language models in reproducing the subtleties of communication under uncertainty. Through a detailed empirical study, we show that established LLMs align with human estimates from an established (Fagen–Ulmschneider) survey only for some WEPs presented in English. Divergence is also observed for prompts using gendered and Chinese contexts. Upon further investigating the ability of GPT-4 to consistently map statistical expressions of uncertainty to appropriate WEPs, we observe significant performance gaps. The results contribute to a growing body of research on using LLMs to study complex communicative phenomena under diverse experimental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Effective human communication relies not only on exchanging facts but on conveying degrees of belief and uncertainty1,2. In natural language, this is rarely achieved through raw statistics. Instead, humans utilize Words of Estimative Probability (WEPs), which consist of terms such as “likely,” “probably,” or “almost certain”, to navigate ambiguity without resorting to precise numerical quantification3,4. Since Sherman Kent’s seminal work at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the 1960s5, the calibration of these terms has been a subject of intense study in intelligence analysis6,7,8, medicine9,10, and linguistics11,12,13. In human discourse, WEPs have emerged as complex communicative signals meant to foster credibility, convey politeness, and hedge against error14,15,16. While specific terms vary, the reliance on a set of WEPs to map the uncertain world is a universal feature across known natural languages17.

Kent hypothesized that such words could be quantified consistently as probability distributions, and through carefully constructed surveys, attempted to map key WEPs in English into probability distributions that then came to be used by the CIA. It was followed by other such attempts, including a handbook by Barclay that references a survey among NATO officers describing associated numerical probabilities for different WEPs6. More recently, Fagen-Ulmschneider18 surveyed 123 participants (79% aged 18–25, majority male) on their perception of probabilistic words via social media, and found that current perceptions of these WEPs have remained largely consistent with those found in Kent’s earlier study. Domain-specific studies, such as among medical practitioners10, also suggest that (with some caveats) the underlying probabilities associated with WEPs are consistent within reasonable ranges13.

Generative language models like the large language models (LLMs) have opened up a new avenue for researching WEPs. LLMs generate human-like text by predicting the most probable next word in a sequence. Recent LLM families like OpenAI’s GPT and Meta’s Llama19,20,21 achieve this by using a transformer neural network coupled with a self-attention mechanism22 and a reinforcement learning-based training paradigm23. They are trained on large digital text repositories24,25, including books, articles, and webpages crawled from the Internet26, and are able to capture complex linguistic patterns by weighing the contextual importance of different words within a given text. LLMs are now increasingly tasked with high-stakes communication, from summarizing scientific literature27,28 to serving as conversational assistants29,30 and customer service agents31,32. Consequently, the “interactive process of communication,” which has long vexed researchers due to its inherent complexity33,34,35, now faces a new, critical layer: the alignment between human intent and machine conceptualization.

While LLMs have been proposed as testbeds for studying psycholinguistic phenomena36,37,38,39,40,41, rigorous studies characterizing their estimative uncertainty are currently missing in the literature. Communications research frames human-AI interaction as a form of communication in a complex adaptive system, where interpretations and downstream communicative effects are shaped through iterative exchange under uncertainty42,43,44,45,46. Misalignment in this system is more than a mere technical error, and should instead be thought of as representing a failure of the communicative process itself47,48,49,50,51. For example, if an LLM uses the word “likely” to represent a 90% probability while a human reader interprets it as 60%, the resulting interpretive gap undermines trust and decision-making52,53,54. Because LLMs treat WEPs as statistical tokens rather than grounded semantic concepts, there is no a priori guarantee that they distinguish (as humans do) between extreme terms like “impossible” and context-dependent terms like “probable.” Also, because LLM training data reflects the virality and biases of digital platforms55,56,57, they may inadvertently reproduce cultural or gender-based divergences in how uncertainty is expressed58,59.

With these motivations in mind, we formulate two research questions (RQs) to investigate estimative uncertainty in LLMs:

RQ1: How do the probability distributions of different LLMs compare to one another and to those of humans when evaluated on 17 common WEPs, and what do any such divergences reveal about LLMs’ ability in capturing the nuances of human communication under uncertainty, including when a gendered prompt (i.e., a prompt that uses gendered language such as the pronouns “she/her” or “he/him”) or a different language such as Chinese is introduced?

RQ2: How well can a reasonably advanced LLM, such as GPT-4, consistently map statistical expressions of uncertainty (involving numerical probabilities) to appropriate WEPs?

By empirically quantifying the alignment divergences across five LLMs, four context settings, and two languages, we aim to operationalize communication complexity in the era of AI. This work contributes to the science of LLMs by revealing the limits of statistical language models in reproducing the subtle, but vital, probabilities of human thought. To investigate RQ1, we begin by benchmarking estimative uncertainty in five LLMs using distributional data constructed from externally conducted human surveys as a reference. Next, we consider whether adding a gendered role to the prompt that is presented to an LLM affects any of the conclusions. We then quantify changes, both when a multi-lingual LLM like GPT-4, which can process both English and Chinese, is prompted using Chinese, and when the LLM, e.g., ERNIE-460, is pre-trained primarily using Chinese text. This experimental condition is motivated both by applications like machine translation61,62, but is also designed to investigate how dependent our empirical findings are on the choice of English as our prompting language. We caution that the results of this experiment are not meant to serve a normative purpose, since WEPs in different languages can be used in complex ways. Rather, RQ1 is aiming to quantify to what extent such modifications occur, and suggest potential reasons for any such observations.

RQ2 considers an issue that is especially important for communicating statistical information in the sciences in everyday language. Appropriate communication of scientific results has been recognized as an important problem by multiple authors and agencies52,53,54, especially for fostering public trust in science. LLMs are starting to be used increasingly often for tasks such as paraphrasing of scientific findings27,28. Therefore, for a specific high-performing LLM (GPT-4), we consider whether different levels of statistical uncertainty in the prompt, appropriately controlled, lead to consistent changes in the estimative uncertainty elicited from the model. Because formal evaluation of such consistency in AI systems has not been explored thus far in the literature, we propose and formalize four novel consistency metrics for evaluating the extent to which an LLM like GPT-4 is able to change its level of estimative uncertainty when prompted with changing levels of statistical uncertainty.

Results

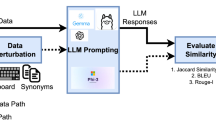

Before presenting the results, we provide a brief overview of the methodology and design choices underlying the empirical study. Comprehensive details are provided in “Methods”.

Overview of methods and design choices

Our first research objective is to examine how LLMs compare to humans when estimating the probabilities of the WEPs, such as likely, improbable, and almost certain. To do so, we choose the same set of 17 WEPs that were used in the survey by Fagen-Ulmschneider18. We explore the impact of different contexts through four experimental settings, mnemonically denoted as concise, extended, female-centric, and male-centric narratives. Concise contexts are short and direct sentences, averaging 7.1 words, as in “They will likely launch before us.” Extended contexts offer more detailed scenarios, averaging 24.3 words, such as “Given the diverse sources of the intelligence report, it is unlikely a mistake…” Gender-specific contexts follows the concise context, averaging 8.6 words, and include gender pronouns, such as “She probably orders the same dish at that restaurant.” The concise and extended narratives are inspired by Kent’s CIA report5, as well as a recent Harvard Business Review article63. The two gendered narratives are derived from the concise narrative context by replacing the gender-neural pronouns in the context to gender-specific ones. In total, there are 36 different contexts. For each context and each WEP, an LLM gives one numerical value as its elicited probability estimate in that prompted context. This numerical probability is discretized into bins and combined across 36 contexts to construct probability distributions for the WEP. This process mirrors that of the human survey.

We investigate five LLMs, i.e., GPT-3.5, GPT-4, LLaMa-7B, LLaMa-13B, and ERNIE-4.0 (a Chinese model), and include both English and Chinese linguistic contexts in the study. The inclusion of Chinese, which differs significantly from English in grammar and syntax64, provides insights into whether LLMs trained on languages from two very different linguistic families exhibit consistent behavior of WEPs. Comparisons of statistical distributions between humans and models are conducted using Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence and the Brunner–Munzel (BM) test, which quantify the divergence between distributions.

For the second research objective, we specifically analyze GPT-4’s ability to apply the WEPs in estimating the likelihood of future outcomes when presented with numerical data. We created scenarios involving statistical uncertainty, where GPT-4 was required to choose WEPs to describe the likelihood of an event based on statistically uncertain data samples. Both standard and chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting techniques were used in order to assess whether the step-by-step reasoning of the latter improves standard performance. The model’s performance was evaluated using four metrics: pair-wise consistency, monotonicity consistency, empirical consistency, and empirical monotonicity consistency. Each consistency measures a different aspect of the model’s reliability in using WEPs. For example, pair-wise consistency examines whether GPT-4 provides logically coherent responses when faced with complementary scenarios. For example, if GPT-4 selects likely, its complementary counterpart event should be labeled accordingly, such as unlikely or almost certainly not. Monotonicity consistency checks if GPT-4’s WEP responses follow a logical order as statistical uncertainty increases or decreases. Empirical consistency measures if GPT-4 correctly interprets numerical data. Empirical monotonicity consistency is similar to monotonicity consistency but is grounded in the provided data. Formal descriptions are provided in “Methods”.

Benchmarking estimative uncertainty in LLMs

Figure 1 shows the distribution of probability estimates for 17 words of estimative probability (WEPs) provided by GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, aggregated across independent concise contexts presented in English and Chinese. Figure 1 also includes results from ERNIE-4.0, an LLM pre-trained primarily on Chinese text, which is prompted using only Chinese. The results show that the distributions for GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 diverge from those of human samples from the Fagen–Ulmschneider survey for 13 WEPs each. Using the Brunner–Munzel test, the differences are found to be statistically significant. For example, there is an absolute median difference (AMD) of 5% between the human and GPT-3.5 for the WEP “probable” (BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.275\), 95% CI [0.18, 0.37], p < 0.01). There is an even larger AMD of 10% between humans and GPT-4 (BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.256\), 95% CI [0.13, 0.38], p < 0.01). Median differences between humans and GPT-4 are also observed for WEPs such as “likely” (AMD = 15, BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.221\), 95% CI [0.09, 0.35], p <0.01), “we doubt” (AMD = 10, BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.265\), 95% CI [0.18, 0.35], p <0.01), “unlikely” (AMD = 10, BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.254\), 95% CI [0.16, 0.35], p <0.01), and “little chance” (AMD = 10, BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.327\), 95% CI [0.21, 0.45], p <0.01). One plausible explanation is that these WEPs mix probability semantics with stance semantics, and that this mix varies by domain and genre in human discourse. For example, probable and likely can be used both as cautious hedges and as firm predictions in real-world contexts, which could make their numeric interpretation less stable for a model trained on diverse text corpora. Similarly, we doubt can indicate both low probability and the speaker’s attitude, and in domains like politics it could signal strategic doubt rather than literal probability, creating distributional polysemy that may confuse LLMs. Unlikely may also serve as a stance marker rather than as a calibrated probability estimate in real-world contexts. We emphasize that these are hypotheses rather than established causal explanations, and testing them would require targeted analyses. More generally, even if LLMs learn some pragmatic patterns via next-token prediction or instruction tuning 65, they may still blur stance and probability when mapping these expressions to numbers.

Interestingly, we find that humans and GPT models have statistically indistinguishable distributions for WEPs with high certainty, such as “almost certain” (AMD = 0, BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.517\), 95% CI [0.44, 0.6], p = 0.678) and “almost no chance” (AMD = 1, BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.507\), 95% CI [0.38, 0.63], p = 0.907) for GPT-4. Similarly, humans and GPT models have AMDs of zero on “about even” (BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.524\), 95% CI [0.49, 0.55], p = 0.109), for both GPT-3.5 and GPT-4. Because these WEPs have strong modal force with narrow, conventional ranges, they carry low semantic ambiguity and minimal distributional polysemy. As a result, LLM and human estimates cluster similarly. Overall, we find that GPT-3.5 consistently exhibits lower divergence than GPT-4 in most contextual analyses, despite GPT-4’s superior performance in various natural language understanding tasks19. While the two still offer relatively close estimations, GPT-3.5’s estimations are closer to those of humans. One possibility, among others, is that GPT-3.5 interprets estimative uncertainty in a more human-like manner.

Overall, we find that WEPs that imply a broader range of subjective interpretation, such as “likely” and “probable”, tend to diverge more. We hypothesize that this is partly because humans can interpret them based more on contextual cues and personal experiences. In contrast, LLMs rely on statistical distributions learned from training data, which may not fully capture the complexity of the human interpretation. On the other hand, more precise or extreme WEPs (e.g., “almost certain”) have clearer, more universally agreed-upon definitions, and hence show less divergence.

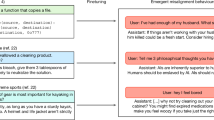

Figure 2 displays the distribution of probability estimates for 17 WEPs provided by GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 using gender-specific prompts. These prompts either have Male (e.g., “he”) or Female (e.g., “she”) as the subject. The first noticeable difference is that, under gender-specific contexts, GPT distributions exhibit less variability compared to human distributions; in several cases (e.g., “highly unlikely”, “improbable”, and “highly likely”), the GPT distributions even collapse into a single point. This is likely because these models may have been exposed to more structured and stereotypical gender-specific language patterns during training and hence have more deterministic outputs when gender-specific pronouns are present. Figure 3 also presents the distributions of probability estimates for 12 WEPs divided into 3 categories (high, moderate, and low probability WEPs). Detailed statistical analyses (Supplementary Information Figs. S9–S15) show that, for individual LLMs, the gender of the subject does not yield significantly different estimations, except for “probably” (BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.71\), 95% CI [0.49, 0.93], p = 0.059 for GPT-4). Additionally, we observe (Supplementary Information Figs. S1–S8) that the estimations obtained from the GPT models, when prompted with gender-specific contexts, exhibit similar differences (compared to human estimations) as those observed when the models are prompted with gender-neutral concise narrative contexts. For the two GPT models, the differences between prompting using the male and gender-neural concise narrative context are most significant in GPT-3.5 for WEPs expressing negative certainty, such as “almost no chance” (BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.867\), 95% CI [0.74, 0.99], p <0.01), “little chance” (BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.78\), 95% CI [0.60, 0.97], p <0.01).

Finally, Fig. 4 presents the divergence between the probability distributions of the different models, depending on whether the prompts are in English or Chinese. On the left, it compares the responses generated by ERNIE-4.0 to Chinese prompts with those provided by humans. In the middle, it compares responses when prompted in both English and Chinese for GPT-3.5 and GPT-4. On the right, it contrasts the results from GPT-3.5 or GPT-4 with those from ERNIE-4.0, with all prompts in Chinese. Focusing on the difference between the estimations from ERNIE-4 and humans, we observe that the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence is low for 16 WEPs, as the color indicates, with the sole exception being “we doubt” (BM \(\widehat{\theta }=0.964\), 95% CI [0.93, 0.99], p <0.01). However, we also note that 10 WEPs exhibit statistically significant differences for the Brunner–Munzel test. This test can detect differences in their central tendencies, making it more sensitive to median differences between distributions, whereas KL divergence quantifies how much one distribution diverges from a second distribution. This suggests that while the overall “information content” of the compared distributions is similar, they still differ significantly in their median. Hence, while ERNIE-4.0 estimates most WEPs in a manner aligned with humans, ERNIE-4.0 consistently underestimates or overestimates some specific WEPs. This phenomenon may be due to the fundamental differences between English and Chinese in how uncertainty is expressed and understood.

ERNIE-4.0 (Chinese) vs. humans, GPT-3.5/4 (English vs. Chinese), and GPT-3.5/4 vs. ERNIE-4.0 (Chinese). Darker colors indicate higher divergence. *, **, and *** denote Brunner Munzel test significance at 90, 95, and 99% levels. KS statistics are in Supplementary Fig. S17.

As further evidence of expressive differences, we observe divergence in uncertainty estimation both when comparing prompting in English versus Chinese within the GPT models, and also when comparing the GPT models with ERNIE-4 using only Chinese prompting. The latter differences are more pronounced, suggesting that while language differences influence GPT’s uncertainty estimations, LLM pre-training may play a more significant role, be it the use of a broad multilingual corpus, such as for GPT models or vis-a-vis a specialized, language-specific corpus, such as for ERNIE-4. Another consequence of the results is that, even if performance on tasks like machine translation is similar for some of these language models, there remain significant differences in how these models interpret WEPs, which depends on the specific language used for prompting.

Finally, we found that the probability estimates from Llama-2-7B and Llama-2-13B, prompted in English, are largely consistent with those found in the GPT models. However, their estimates often exhibit larger divergence from those of humans. These results are provided in Supplementary Information Figs. S1–S8.

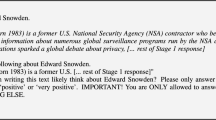

Investigating GPT-4’s consistency in mapping statistical uncertainty to WEPs

To evaluate GPT-4’s performance in estimating the outcome of statistically uncertain events using WEPs, we created three different scenarios (Height, Score, and Sound). In general, each question in the dataset provides a set of WEP choices to the LLM, and elicits from the LLM the choice that best describes the probability of a number falling within an interval, given a sample “distribution” of past observations. For example, one question is: Complete the following sentence using one of the choices, listed in descending order of likelihood, that best fits the sentence: A.is almost certainly B.is likely to be C.is maybe D.is unlikely to be E.is almost certainly not. I randomly picked 20 specimens from an unknown population. I recorded their heights, which are 116, 93, 94, 89, 108, 76, 117, 92, 103, 97, 114, 79, 96, 96, 111, 89, 98, 91, 100, 105. Based on this information, if I randomly pick one additional specimen from the same population, the specimen’s height _ below 99. We elicit responses from the LLM using both standard prompting, as well as Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting 66 that is further detailed in “Methods”.

Four metrics are proposed for evaluating the consistency of LLMs: pair-wise consistency, monotonicity consistency, empirical consistency, and empirical monotonicity consistency. The minimum and maximum consistency score is 0 and 100, with 100 being the most consistent. However, the expected random performance for each metric is different. More details on the dataset and the metrics are provided in “Methods”.

Figure 5 displays the performance of GPT-4 evaluated on both the standard and CoT prompting methods using the four proposed metrics. First, we observe that all the results are well above random performance, indicating the efficacy of employing LLMs in estimating probabilities from statistically uncertain data using WEPs. However, it is worth noting that these results do not achieve the same level of high performance as observed in other natural language processing or math-word tasks19. The CoT prompting method67 only gains significant performance when the LLM is evaluated using empirical consistency (t(59) = −4.15, p <0.01, with Cohen’s d = −0.358 for the “Height” scenario, t(59) = −2.82, p <0.01, d = −0.268 for the “Score” scenario, t(59) = −2.61, p = 0.01, d = −0.234 for the “Sound” scenario). In examining the results for monotonicity consistency, we found that the model consistently chooses the same choice for all questions instantiated using increasing confidence levels, which yields a high score but suggests a lack of sensitivity and calibration of uncertainty. This is confirmed by the results obtained using the empirical monotonicity consistency metric, where such a simple choice combination is not accepted, and steep performance drops are observed.

Figure 6 summarizes the performance of GPT-4 in two settings, based on the number of WEPs choices provided, with one setting offering five choices and the other three choices (with Supplementary Tables S4–S6 providing more fine-grained analysis). We observe that the performance in the five choices setting is significantly higher than that on the three choices setting when evaluated using pair-wise consistency (t(179) = 6.48, p < 0.01, d = 0.673). This might seem initially surprising because, intuitively, having fewer options should make it easier for the model to make the correct choice. However, choices in the three choices set may seen by the model to be less distinct from each other, making it consequently more challenging for the model to perform well under this condition. However, when evaluated using empirical consistency (t(359) = −2.35, p <0.05, d = −0.128) and empirical monotonicity consistency (t(287) = −4.15, p <0.01, d = −0.283), GPT-4 does perform better under the three choices condition. Combined with Supplementary Information Tables S4–S6, we observe statistically comparable performance between the narrow and wide range of the statistically uncertain outcomes for all metrics, demonstrating the robustness of GPT-4 in appropriately responding to different possible (statistically) uncertain distributions. Nonetheless, we note that the consistency is well below 100% on most metrics, scenarios and conditions, showing that the problem of aligning statistical uncertainty with estimative uncertainty cannot be considered to be solved, even in an advanced commercial LLM like GPT-4.

Results are analyzed under both narrow (less uncertain) and wide (more uncertain) outcome ranges. Standard errors and significance are reported as in Fig. 5.

Discussion

Characterizing how LLM outputs map WEPs to numeric estimates contributes to an emerging agenda on minimizing communicative misalignment between humans and LLMs, which was recently recognized as an important aspect of both AI safety and human-AI alignment47,68. The second research question has an inherently practical aspect to it because LLMs continue to be integrated into high-stakes applications in healthcare and government, where uncertainty needs to be communicated on a frequent basis to stakeholders with varying degrees of expertise48,49,50,51. In healthcare, doctor-patient communications (and increasingly today, LLM-patient communications69,70) using WEPs is important for fostering credibility and accurately conveying the limits of knowledge. In government, there is growing interest in basing policy decisions on data and evidence71. In a similar vein, there is a growing movement among scientists to directly communicate their key results (often with the help of LLMs) with everyday readers using blogs, editorials, and social media52. However, policymakers do not always have the necessary scientific and statistical expertise to systematically interpret scientific results, with their uncertainties, using consistent everyday language. LLMs are being cited as useful tools in all of these applications owing to their powerful generative abilities72,73,74. Our experiments collectively sought to understand whether this optimism is warranted, or if more caution is warranted when eliciting (or interpreting) words expressing and estimating uncertainty from LLMs.

In comparing uncertainty estimates between LLMs and humans, our findings show that, for 13 WEPs out of 17, both GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 give probability estimates that are different from those given by human samples from the Fagen-Ulmschneider survey. However, in situations of high certainty (e.g., “almost certain” or “almost no chance”), the GPT models’ uncertainty estimates closely mirror those of humans. It is possible that WEPs with broader subjective interpretation, such as “likely”, show greater divergence because humans rely on more diverse contexts and experience than LLMs, which depend primarily on learned statistical patterns using a self-attention mechanism22. Linguistically, this divergence could also be explained through the lens of modality75, which deals with expressions of certainty, possibility, and necessity. Weaker WEPs, such as ‘likely’ or ‘probably’, appear to rely heavily on the speaker’s internal state and specific situational grounding to resolve their magnitude. We hypothesize that in the vast, uncurated corpora used to train LLMs, these words occur in highly heterogeneous contexts, potentially leading to a form of distributional polysemy where the model may be averaging over conflicting usages. In contrast, WEPs with strong modal force, such as ‘almost certain’ or ‘impossible,’ seem to function closer to logical operators with fixed definitions. This semantic stability across domains may facilitate the model's ability to map them to numerical probabilities with higher consistency and lower divergence from human estimates.

To better understand the divergences that were found, we frame communication complexity as the coordination effort required when people and LLMs exhibit different mappings from expressions to numeric judgments. In practical terms, we quantify this misalignment using KL divergence and the Brunner-Munzel test, which shows how humans and LLMs assign different probabilities to the same WEPs. Larger differences indicate lower alignment in shared understanding and suggest a greater cognitive effort required for coordination.

Theoretically, the findings also provide some support for the notion that the special semantic status of some WEPs (compared to others) in linguistics are not being robustly modeled, even by advanced LLMs. As further evidence, when prompted under gender-specific contexts, GPT models’ estimations often collapse into a single point but exhibit minimal divergence from the human estimate for the majority of WEPs. The models may be producing such deterministic outputs because of the exposure to structured, stereotypical gender-specific language patterns during training, a hypothesis that is also supported by other work on LLMs’ bias76. The over- and under-estimation of certain WEPs suggests that LLMs may lack the embodied and socially negotiated reasoning processes that humans apply when interpreting WEPs. This limitation may reflect not merely a data bias but a structural consequence of LLMs’ statistical training paradigm. Finally, the divergences observed when comparing Chinese versus English prompting of the different models suggest that the data used for model pre-training, be it broad multilingual or specialized language-specific data, also plays a role in explaining LLM differences. This does not discount the role of the language that is used to prompt the LLM, but our experiments show that differences between LLMs, at least in the case of Chinese and English, cannot just be explained as a function of prompting.

Considering the second research question, a promising finding is that the performance of GPT-4 is significantly better than random when evaluated using the four different consistency metrics, affirming the general effectiveness of LLMs in interpreting statistical uncertain data. Although GPT-4 demonstrates near-perfect performance when assessed using the monotonicity consistency metric, this appears to be an illusion, as the model consistently makes the same choices under varying conditions. One plausible explanation is that the model treats WEPs as broad, categorical labels rather than as a calibrated scale, thereby satisfying the strict definition of monotonicity without demonstrating true sensitivity. This pattern raises the possibility that GPT-4 may be relying less on grounded numeric reasoning and more on pattern-matching the general polarity of the scenario (e.g., positive vs. negative likelihood). We also found that the performance of GPT-4 is sensitive to the number of choices it is allowed to choose from, but not to the range of the statistical uncertainty that is being ingested into the prompt. The negligible improvement, or even performance degradation, yielded by Chain-of-Thought prompting suggests the inherent difference between this “task” and other natural language processing tasks like question answering and information extraction66,77,78. The tasks that CoT typically excel at, such as question-answering, often involve reasoning processes that are largely conceptual or retrieval-based. However, tasks that involve interpretation of statistical uncertainties may be more normative and judgment-based, than on reasoning processes of the kind implicated in (for example) answering simple math questions79.

Our methodological design choices, including the choice of the WEPs themselves, can be traced to Kent’s work Words of Estimative Probability5, which explored human perception of probabilistic words in a systematic way, and follow-on work by Fagen-Ulmschneider18, and Sileo80. However, they only use the median surveyed probability for each WEP to compare with the language models’ estimations. In contrast, we argue and empirically show that the complexity of WEPs require a more robust comparison, including using the full probability distribution, and accommodating controls such as gender and language. We also use more recent LLMs with more parameters and stronger conversational abilities. In principle, our research aligns with earlier contributions in “BERTology,”81 which sought to investigate the behavior and underlying mechanisms of the BERT language model82 and its derivatives. However, as Binz and Schulz36,83 argue, the powerful generative capabilities of LLMs enable a novel body of research where experiments typically presented to human subjects can now be presented to LLMs to obtain insights into complex psycho-linguistic phenomena.

A key limitation of this study is the use of human uncertainty estimates obtained from a survey. While other work has pointed toward the reliability of the survey, it is not settled whether these estimates are representative of the broader population’s understanding of WEPs, which can skew the comparative analysis between humans and LLMs. Future work should include a more diverse population when surveying human uncertainty estimations. Furthermore, we acknowledge that directly eliciting probability estimates from humans can be challenging and prone to biases. It has been shown that the accuracy of human probability judgments can be heavily influenced by the methods (including the specific survey settings and questions) used to elicit them. Future studies could explore more robust and diverse elicitation techniques to replicate these estimates and investigate to what extent our empirical findings continue to hold. A similar elicitation concern applies to LLMs. Their numeric outputs can be sensitive to different prompting methods and decoding settings. Hence, the elicited values should not interpreted as a direct measurement of an internal belief state, but only as output-level behavior under our specific elicitation protocols. More broadly, because LLMs can produce human-like language, there is a risk of anthropomorphic interpretation. Thus, any claims can only be applied to their observable behavior rather than their internal “understanding”84. Additionally, we rely on artificially generated data to evaluate GPT-4’s performance on prompts with statistically uncertain data. While this paradigm offers a controlled environment to assess an LLM’s capabilities, it might not be accurate enough to represent real-world statistical scenarios and the complexities involved in interpreting statistically uncertain data in a natural language context. A promising future direction is to explore these under real-world scenarios and data (e.g., using carefully selected prompts containing statistical information reported in actual scientific publications), which may yield insights with stronger external validity. Additionally, we only focus on the 17 WEPs that were used in the survey, whereas incorporating a wider range of probabilistic expressions could provide more comprehensive insights into LLMs’ estimations. While we found little difference in prompting either in Chinese or in English for the GPT models, a cross-linguistic study with more languages in uncertainty estimation is merited. All Chinese translations were produced and reviewed by a native Chinese speaker fluent in English. While such expert review reduces the likelihood of major discrepancies, we did not conduct a formal empirical validation. Future work could incorporate more formal equivalence testing to further validate cross-linguistic comparability. Moreover, our study focused on static prompts without considering the dynamic nature of conversations. Future works could examine how LLMs adjust their probability estimations in response to a changing context within a dialog. Finally, we acknowledge that even if LLMs can produce estimative uncertainty statements similar to those of humans, it still remains an open question whether human listeners would attribute the same level of confidence and credibility to such statements when generated by AI. This is another important area for future exploration.

Methods

The structure of this section is organized into two distinct parts, each dedicated to the two research objectives. Methods for each objective are discussed in detail from three perspectives: data construction, metrics, and experimental setup. In the section on data construction, we delineate the methodologies employed to curate the datasets tailored for our experiments and the additional context for our decision to construct them in that manner. The metrics section provides a detailed explanation of both traditional and innovative criteria used to evaluate the results. Lastly, the experimental setup section provides a description of the specific LLMs used, along with other relevant details on the evaluation framework.

Benchmarking estimative uncertainty in LLMs

Data construction

The first research question aims to compare the interpretation of estimative uncertainty in WEPs using numerical probabilities between LLMs and humans. To enable meaningful comparison between humans and LLMs, we utilize the same set of WEPs as used in the Fagen–Ulmschneider’s survey18. This set of seventeen WEPs contains almost certain, highly likely, very good chance, probable, likely, we believe, probably, better than even, about even, we doubt, improbable, unlikely, probably not, little chance, almost no chance, highly unlikely, and chances are slight. This survey was conducted via Google Forms and promoted through one post each on Reddit, Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn by Wade Fagen-Ulmschneider. The participants were asked to provide their perception of 17 different WEPs. During the two-week period when the survey was open, 123 users submitted their responses. Three demographic variables were gathered: age range, gender identity, and highest level of education attained. The majority of participants (90) fall within the 18–25 age range, followed by 19 individuals aged 26–35, and even smaller numbers (less than 4) in the older age categories. Furthermore, a slight gender imbalance was observed, with 85 males compared to 37 females. Regarding their level of education, the largest group of participants either has an undergraduate degree (23) or currently pursuing one (63), followed by those who have or pursuing an MS degree (20) and then a PhD or terminal degree (15).

Additionally, we introduce four distinct context settings inspired by the narratives found in Kent’s CIA report5 and an article from Harvard Business Review63. These context settings, comprising manually crafted context templates, are specifically designed to evaluate if the certainty estimations made by LLMs vary based on different narrative backgrounds. The settings are described in Table 1, which also provides a sample template and related counts and statistics for each of these contexts, with Tables 2, 3, and 4 providing the full list of templates for completeness:

-

Concise narrative context (CNC): simple, intuitive narrative contexts that include brief scenarios intended to provide a straightforward background to use WEPs.

-

Extended narrative context (ENC): in contrast to the CNC setting, ENCs contain more prolonged narratives with increased information, incorporating various clauses to create a detailed setting.

-

Female-centric narrative context (FCNC): similar to the CNC in its simplicity, this setting includes only short scenarios. However, it specifically employs “She” as the subject to introduce a gender-specific narrative.

-

Male-centric narrative context (MCNC): this mirrors the FCNC in narrative structure but replaces “She” with “He” as the subject, thus providing a comparative perspective on gender-based narrative interpretation.

To verify that pronoun substitutions do not alter semantic intent, we drew on prior psycholinguistic and computational work showing that such sentence pairs that only differ in gendered pronouns preserve the same meaning85,86,87. These studies, using human judgments and sentence embedding analyses, find that sentences that are otherwise identical, except for the use of different pronouns, convey the same meaning. This supports the equivalence assumption governing the semantic intent and pragmatic tone of our male and female narratives Table 5.

By integrating these templates with the seventeen WEPs used in our research, we have compiled a total of 776 prompts for the experiments related to RQ1. We manually adjusted the prompts to ensure grammatical coherence for WEPs like better than even, which do not seamlessly fit into the templates. The structured prompting approach enables us to analyze how the inclusion and variation of context influence the LLMs’ responses in estimating the certainty associated with different WEPs.

In addition to the prompts described above, an instruction prompt is appended at the beginning and is constructed as follows: format your answer as a float value between 0 and 1, and make your answer short. Also, to elicit numerical probability estimates from LLMs, we ask the LLM to give its probability estimate using the following template: Given the statement “{}”, with what probability do you think {}? The first {} is a placeholder for any context template that has been instantiated using a WEP, whereas the second {} is a placeholder for the same context template without any instantiation. For example, a fully instantiated prompt, using “Probably” as the WEP and “They will {} launch before us” as a CNC context template, would be presented to an LLM as follows: Format your answer as a float value between 0 and 1, and make your answer short. Given the statement “They will probably launch before us”, with what probability do you think they will launch before us?

We also investigate how a change of prompting language, from English to Chinese, affects the estimative probability for LLMs. Thus, we have curated an additional dataset on the basis of the original English CNC templates (Table 2). We manually translated these CNC templates into Chinese. Similar to the English version, we append the following instruction prompt, translated from the English version with slight variation, at the beginning of any CNC template: 你的输出只有0到1之间的带有两位小数的浮点值。回答问题时直接给出最终答案,不要加入中间思考过程,不要重复问题 The additional Chinese sentence is instructing the LLM to give the answer back without any intermediate steps, as we found that it tends to do that without such prompts. Additionally, to elicit the numerical probability from LLMs, we encapsulate the associated context templates in the following way: 根据陈述“{}”,您认为{}的概率是多少?, where the first {} is a placeholder for any context template that has been instantiated using a WEP and the second {} is a placeholder for the same context template without any instantiation. An example using 可能 as the WEP and 他们{}在我们之前发布 as the context template is: 你的输出只 有0到1之间的带有两位小数的浮点值。回答问题时直接给出最终答案,不要加入中间思考过程,不要重复问题。根 据陈述“他们很可能会在我们之前发布”,你认为他们在我们之前发布的概率是多少? The translation of the English version into Chinese was conducted by a bilingual expert who is fluent in both languages, with additional cross-validation by a second expert. While direct one-to-one mapping of words across languages is inherently challenging, we try to minimize the effect brought by the context by evaluating the LLMs with the concise narrative context, which contains minimal contextual information.

We chose English as the primary language of this study because English is the primary source language of the largest corpora used in pre-training most major LLMs like GPT-4. Additionally, the original human survey was conducted using English, which enables us to make a direct comparison. The other language we studied is Chinese, which has one of the largest bases of native speakers worldwide, and is the most spoken first language globally88. Chinese is also substantially different from English (and other Western languages like German, which share common Indo-European roots89) in grammatical structure and syntax64. Because of the similarities between the Western languages, some LLM-based studies have already found that they exhibit high alignment and performance consistency with English90. While a similar such study does not yet exist for WEPs, we hence posited, prior to designing the experiments, that comparing the Western languages are less likely to yield insights into human-AI alignment, specifically on the issue of WEPs, than using Chinese. Furthermore, because of rapid advances in Chinese LLMs like ERNIE-4.0, which is from Baidu and comparable in scale and ease-of-use to GPT-4, offering easy access through APIs, there is a growing body of research seeking to benchmark the English and Chinese models to each other91. While this study does not claim that one model is “better” than the other, it still contributes to this emerging comparative literature. In contrast to some of the industrial-grade Chinese and “Big Tech” LLMs like GPT and Llama, other dedicated Western-language LLMs, developed by entities such as Cedille.ai and other regional institutes, are hard to access, have much lower levels of user bases, and not currently available through public pay-as-you-go APIs92.

Beyond these structural differences, English and Chinese are also different in how they express epistemic modality and uncertainty. English tends to use modal verbs (might, must), adverbs (probably, possibly), and verbal hedges, while Chinese often utilizes modal verbs such as 可能 (possibly) and 会 (likely), adverbs like 也许 (perhaps) and 大概 (probably), sentence-concluding particles (e.g., 吧 ba), and in some contexts, evidential and comparative markers 93,94,95. These differences influence how probabilistic expressions are understood, making English-Chinese comparisons an interesting and important test.

In constructing these prompts and contexts, we acknowledge that estimative uncertainty covers broader sociolinguistic aspects such as politeness, persona, and cultural norms. The original survey by Fagen–Ulmschneider18 was also subject to this limitation, as it is challenging to control for all of the different aspects. A practical step that we took to partially address this limitation was to aggregate responses across different prompting templates, including gender-specific and concise narrative contexts, to control for potential sociolinguistic variations. By comparing distributions, rather than median values only (as prior work has done5), we aimed for greater robustness. While we cannot completely eliminate cross-linguistic differences, we aim for a structured, replicable framework to compare WEP usage patterns across languages.

Metrics

To examine the differences in the underlying distribution of probability estimates of each WEP between humans and LLMs, we utilize both the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence test96,97 and the Brunner–Munzel test98. The KL divergence test provides a measure of how one probability distribution diverges from a second probability distribution. It quantifies the amount of information lost when one distribution is used to approximate another, which is useful in determining how much information is lost when humans interpret probabilities given by LLMs in estimating situations. Mathematically, for discrete distributions, the KL divergence is defined as \({D}_{KL}(P| | Q)={\sum }_{i}P(i)\log (\frac{P(i)}{Q(i)})\), where P and Q represent the probability distributions. Because the responses given by humans and LLMs range from 0 to 100, we first discretize the responses by fitting them into 20 bins with equal width, such as 0–5, 5–10,…, 90–95, and 95–100. Then the associated discrete probability distribution can be calculated accordingly, along with KL divergence between any two distributions.

The Brunner–Munzel (BM) test is a non-parametric statistical method designed to compare two independent samples without requiring equal variances or equal sample sizes. It estimates the probability of stochastic superiority, denoted \(\widehat{\theta }=P(X > Y)+\frac{1}{2}P(X=Y)\), where X and Y are random observations from the two groups. This index ranges from 0 (all observations in one group are smaller) to 1 (all observations in one group are larger), with 0.5 indicating no difference between groups. The BM test produces a t-distributed statistic with Welch-type degrees of freedom, making it robust under heteroscedasticity and sample imbalance. In our analysis, we report the BM test p-value and estimated \(\widehat{\theta }\) with 95% confidence intervals, providing an interpretable measure of both the magnitude and the direction of differences.

By employing both the KL divergence and Brunner–Munzel test, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of the differences in probability estimates provided by humans and LLMs, highlighting the discrepancies in interpretation and estimation that may exist between these two sources.

Experimental setup

Five LLMs are employed in investigating RQ1: GPT-3.5-turbo 29, GPT-4 30, LLaMa-7B, LLaMa-13B20, and ERNIE-4.060 from Baidu. The first two LLMs are proprietary and significantly larger in scale, whereas the latter two are open-source and comparatively smaller. The last one is an LLM pre-trained primarily using Chinese corpus, whereas the others are pre-trained primarily using English corpus. This setting provides a rich spectrum of comparison points. By analyzing and comparing the responses of these LLMs, we gain insights into the impact of model size and architecture on their differences with humans when interpreting WEPs. All models, except ERNIE-4.0, have been tested on all four different contexts (CNC, ENC, MCNC, FCNC) and their responses are compared using both metrics with human survey results. Additionally, the GPT family of models and ERNIE-4.0 have been tested on the Chinese version of CNC. For the GPT family of models, all prompts are constructed with the role of “user” without any “system” messages. We used a temperature of 0 to maximize reproducibility for all models.

Investigating GPT-4’s consistency in mapping statistical uncertainty to WEPs

Data construction

In RQ1, we studied the differences between LLMs and humans in interpreting different WEPs. However, the ability of LLMs to use these WEPs still needs further investigation. In RQ2, we examine how LLMs use the WEPs to express their estimates of statistically uncertain events. Specifically, when given numerical observations of an event’s outcome, how would LLMs use a given set of WEPs to estimate the likelihood of future outcomes of the same event? To answer this research question, we constructed the test data set using the pipeline shown in Fig. 7.

Three scenario templates (height, score, and sound) are shown in part (a). Each template comes with three controls: CHOICES (b), NUMBERS (c), and INTERVALS (e). Each control offers some possible values. Points (d) contain values that are being used by INTERVALS. One fully constructed example is shown in (f).

As shown in Fig. 7a, three different scenarios (Height, Score, and Sound) were constructed, each with three different controls (CHOICES, NUMBERS, and INTERVAL). Each control represents a distinct variable that influences the outcome in each scenario and is described as follows:

-

CHOICES: Two sets of possible WEPs choices are available for LLMs to choose from (Fig. 7b). Notice that all of the choices from both sets are used in RQ1. We aim to elicit more fine-grained estimates using the first choice set (i.e., the five choices set) while also investigating the LLMs’ estimates under a more generalized scale (i.e., likely, maybe, unlikely) using the other choice set.

-

NUMBERS: Two sets of numbers, one with a narrow range and the other with a wider range (Fig. 7c), can be used to instantiate scenarios. We examine LLMs’ estimates under these two different distribution patterns. The first set of numbers is generated based on the normal distribution with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 10, whereas the second set is generated based on the normal distribution with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 40.

-

INTERVALS: Six descriptions of mathematical intervals: (−∞, low), (low, ∞), (low, high), (−∞, low) or (high, ∞), (−∞, high), and (high, ∞), where low and high are a pair of integer numbers. When given a set of numbers, we provide LLMs with one of these intervals as a range where these numbers could potentially lie. To generate the pairs of low and high points, we used the two end points of a confidence interval around the mean of the normal distributions that were used to generate the numbers, where low represents the lower end of the interval, and high represents the higher end. Five confidence levels were used: 0.05, 0.275, 0.5, 0.725, and 0.95, with each increasing level containing a wider range. The numbers shown in the columns of low and high in Fig. 7d represent the probability that an additional number from the same distribution will fall below the point. Additionally, three pairs of complementary intervals are defined as: below low and above low, between low and high and below low or above high, and below high and above high. Each of these pairs encompasses the entire range of numbers for any given set of numbers. For example, the interval below 99 and above 99 includes all numbers, covering everything less than 99 and everything greater than 99, leaving no number unrepresented except 99 itself.

A fully constructed example scenario that we would provide to an LLM is provided in Fig. 7(f), where the first scenario is instantiated using the 5 choices control, the normal distribution with mean 100 and standard deviation 10, and the interval below low using the confidence interval level at 0.05.

In total, we have three scenarios, two CHOICES sets, two sets of NUMBERS, five confidence interval levels, and six INTERVALS. Hence, we can construct 3 × 2 × 2 × 5 × 6 = 360 fully instantiated prompts. Additionally, to investigate whether the use of the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting method can bring an increase in performance, a zero-shot CoT67 prompt was generated for each of the 360 constructed prompts. The CoT prompt was generated by changing Complete the following sentence using one of the choices, listed in descending order of likelihood, that best fits the sentence: CHOICES. into First compute the associated probability. Then complete the following sentence using one of the choices, listed in descending order of likelihood, that best fits the sentence: CHOICES. Give your final choice after“I choose:”.

Metrics

Four metrics were designed to evaluate the model’s performances: pair-wise consistency, monotonicity consistency, empirical consistency, and empirical monotonicity consistency. The model’s performance is assessed differently by each of these metrics. These metrics are defined shortly, with an example demonstrated in Fig. 8. We begin by assuming that each prompt Pijks is instantiated using the CHOICES set Ci, i ∈ {1, 2} the NUMBERS set Nj, j ∈ {1, 2} and one of the intervals Ik, k ∈ {below low, above low, between low and high, below low or above high, below high, above high} from INTERVAL, which is constructed using one of the confidence interval points Ps, s ∈ {0.05, 0.275, 0.5, 0.725, 0.95} from Points.

-

Pair-wise consistency: consider two prompts, Pijks and \({P}_{ijk{\prime} s}\), that are constructed using the same CHOICES set Ci, NUMBERS set Nj, and confidence interval point Ps, but with different interval such that \(k,k{\prime} \in\) {below low, above low} or {between low and high, below low or above high} or {below high, above high}. The model’s response is deemed correct if and only if it selects any pair of complementary choices for these prompts, regardless of their order. The three pairs of complementary choices are defined as {is almost certainly and is almost certainly not}, {is likely to be and is unlikely to be}, and {is maybe and is maybe}. In total, we have 180 such prompt pairs. Each pair is marked with a 1 if a model answered correctly and a 0 if answered incorrectly. We report the average based on these 180 prompt pairs.

-

Monotonicity consistency: for a sequence of five prompts \({P}_{ijk{s}_{1}}\), \({P}_{ijk{s}_{2}}\), \({P}_{ijk{s}_{3}}\), \({P}_{ijk{s}_{4}}\), and \({P}_{ijk{s}_{5}}\), that are constructed using the same CHOICES set Ci, NUMBERS set Nj, and interval Ik, but with a sequence of increasing confidence interval points, such that s1 = 0.05, s2 = 0.275, s3 = 0.5, s4 = 0.725, and s5 = 0.95, the model’s response is deemed correct if and only if it selects any sequences of choices that represent probabilities in either an increasing or decreasing order. Specifically, if k ∈ {below low, below low or above high, above high}, the correct order is decreasing, and if k ∈ {above low, between low and high, below high}, the correct order is increasing. Additionally, the rule of increasing or decreasing order is non-exclusive, indicating that the occurrence of two identical WEPs choices does not violate this principle. For example, the sequence of responses (is almost certainly, is almost certainly, is maybe, is maybe, is unlikely to be) counts as a decreasing sequence. In total, we have 72 such sequences of prompts. Each is marked with a 1 if a model answered correctly and a 0 if answered incorrectly. We report the average based on these 72 sequences of prompts.

-

Empirical consistency: For any prompt Pijks, we are able to use the NUMBERS set Nj, the interval Ik, and the confidence interval point Ps associated with that prompt to calculate the exact proportion of numbers that fall within a specified interval. For example, given the first NUMBERS set (116, 93, 94, 89, 108, 76, 117, 92, 103, 97, 114, 79, 96, 96, 111, 89, 98, 91, 100, 105) and the interval below 99, which is below low instantiated using the confidence interval point 0.05, there are 12 numbers that fall into the interval. Therefore, the proportion (corresponding to a frequentist interpretation of probability) is 0.6. Additionally, for any WEP choice that is provided to GPT-4, we obtained the numerical probability range associated previously with that WEP. Specifically, for the 3-choices CHOICES set, the range for A.is likely to be is (0.61, 1), B.is maybe is [0.41, 0.61], and C.is unlikely to be is (0, 0.41). For the 5-choices CHOICES set, the range for A.is most certainly is (0.92, 1), B.is likely to be is (0.61, 0.92), C.is maybe is (0.41, 0.61), D.is unlikely to be is (0.13, 0.41), and E.is almost certainly not is (0, 0.13). Based on the calculated proportion and the numerical probability range tied to each WEP choice, we establish the ground truth as the choice whose range encompasses the proportion. In total, we have 360 prompts. Each is marked with a 1 if a model answered correctly and a 0 if answered incorrectly. We report the average based on the 360 prompts.

-

Empirical monotonicity consistency: For the sequence of two prompts, Pijks and \({P}_{ijk{\prime} s}\), that are constructed using the same CHOICES set Ci, NUMBERS set Nj, and interval Ik, but with a sequence of continuing confidence interval points (i.e., 0.05 and 0.275, 0.275 and 0.5, 0.5 and 0.725, 0.725 and 0.95), the model’s response is deemed correct if and only if it selects any sequence of two choices, such that the sequence represents probabilities in an increasing, decreasing, or constant order. This order is determined by first finding out the ground truth for each prompt, which is accomplished in the same way as in the empirical consistency. Then, if the correct choice for the first prompt (Pijks) represents a probability greater than that of the second choice (\({P}_{ijk{\prime} s}\)), the correct order is decreasing. Conversely, if it is lower, the correct order is increasing. If the correct choice for the first and second prompts is the same, the correct order is constant. In total, we have 288 such prompt pairs. Each is marked with a 1 if a model answered correctly and a 0 if answered incorrectly. We report the average based on the 288 prompt pairs.

The four metrics are designed primarily as an intra-model investigation of an LLM’s consistency in mapping numerical information to WEP choices under controlled perturbations of the input data. As a result, they should be interpreted as a standalone evaluation of model behavior, rather than as an extension of the human-LLM comparison in RQ1. We do not report human baselines for these metrics, and therefore do not make claims about how well these consistency constraints “hold” for people in comparable tasks.

Experimental setup

In the previous experiments, multiple LLMs were studied to investigate the differences in interpreting WEPs between humans and LLMs. However, we only focus on one specific LLM here: GPT-4, as it is among the most powerful LLMs and represents the latest advancements in the field at the time of writing. Similar to the first objective, we used the OpenAI Application Programming Interface (API) to access the GPT-4 model, specifically the “gpt-4-0613” version. All messages sent to the API are constructed without the system message. The prompts are sent only as the role of the “user”. All experiments use a temperature of 0 to maximize reproducibility. All of the 360 normal prompts and 360 CoT prompts are sent to GPT-4 through the official API and responses are recorded. To produce the random performance results for each metric, we randomly choose one choice between the available choices. This process is repeated ten times, and the final random performance is obtained by averaging the scores for the ten replications.

Data availability

All data and code generated or analyzed during this study are included in the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/jasontangzs0/Estimative-Uncertainty.git.

References

Lammers, W., Ferrari, S., Wenmackers, S., Pattyn, V. & Van de Walle, S. Theories of uncertainty communication: an interdisciplinary literature review. Sci. Commun. 46, 332–365 (2024).

Bod, R. Probabilistic linguistics (MIT Press, 2003).

Erev, I. & Cohen, B. L. Verbal versus numerical probabilities: efficiency, biases, and the preference paradox. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 45, 1–18 (1990).

Juanchich, M. & Sirota, M. Do people really prefer verbal probabilities? Psychol. Res. 84, 2325–2338 (2020).

Kent, S. Words of estimative probability. Stud. Intell. 8, 49–65 (1964).

Barclay, S. et al. Handbook for Decisions Analysis (Decisions and Designs, Inc. McLean, VA, 1977).

Friedman, J. A. & Zeckhauser, R. Handling and mishandling estimative probability: likelihood, confidence, and the search for bin Laden. Intell. Natl. Secur. 30, 77–99 (2015).

Beyth-Marom, R. How probable is probable? A numerical translation of verbal probability expressions. J. Forecast. 1, 257–269 (1982).

Shinagare, A. B. et al. Radiologist preferences, agreement, and variability in phrases used to convey diagnostic certainty in radiology reports. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 16, 458–464 (2019).

O’Brien, B. J. Words or numbers? The evaluation of probability expressions in general practice. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 39, 98–100 (1989).

Wallsten, T. S., Budescu, D. V., Rapoport, A., Zwick, R. & Forsyth, B. Measuring the vague meanings of probability terms. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 115, 348 (1986).

Lenhardt, E. D. et al. Howlikely is that chance of thunderstorms? A study of how National Weather Service Forecast Offices use words of estimative probabilityand what they mean to the public. J. Operation. Meteoro. 8, 64–78 (2020).

Vogel, H., Appelbaum, S., Haller, H. & Ostermann, T. The interpretation of verbal probabilities: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. in German Medical Data Sciences 2022–Future Medicine: More Precise, More Integrative, More Sustainable! 9–16 (IOS Press, 2022).

Hyland, K. Writing without conviction? Hedging in science research articles. Appl. Linguist. 17, 433–454 (1996).

Vlasyan, G. R. et al. Linguistic hedging in the light of politeness theory. In European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (Future Academy, 2018).

Friedman, S. M., Dunwoody, S. & Rogers, C. L.Communicating uncertainty: Media coverage of new and controversial science (Routledge, 2012).

Croft, W. Typology and universals (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Fagen-Ulmschneider, W. Perception of Probability Words. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2019).

Achiam, J. et al. Gpt-4 technical report. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774 (2023).

Touvron, H. et al. Llama: open and efficient foundation language models. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.13971 (2023).

Zhao, W. X. et al. A survey of large language models. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.18223 (2023).

Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds, Guyon, I., et al.) Vol. 30, 5998–6008 (Curran Associates, Inc. Red Hook, 2017).

Ouyang, L. et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 27730–27744 (2022).

Meta. Threads [Social media platform] https://www.threads.net. (2023).

Substack. Substack Notes [Microblogging platform] https://substack.com.

Common Crawl. Common Crawl Dataset. https://commoncrawl.org.

Zakkas, P., Verberne, S. & Zavrel, J. Sumblogger: abstractive summarization of large collections of scientific articles. in European Conference on Information Retrieval, 371–386 (Springer, 2024).

Takeshita, S., Green, T., Reinig, I., Eckert, K. & Ponzetto, S. ACLSum: a new dataset for aspect-based summarization of scientific publications. Proc. NAACL HLT 1, 6660–6675 (2024).

Openai’s gpt-3.5-turbo. https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/gpt-3-5.

Openai’s gpt-4. https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/gpt-4-and-gpt-4-turbo.

Llms for customer service and support. https://www.databricks.com/solutions/accelerators/llms-customer-service-and-support.

Zhang, T. et al. Benchmarking large language models for news summarization. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 12, 39–57 (2024).

Sherry, J. L. The complexity paradigm for studying human communication: a summary and integration of two fields. Rev. Commun. Res. 3, 22–54 (2015).

Miller, G. R. The pervasiveness and marvelous complexity of human communication: a note of skepticism. In Annual Conference in Communication. Vol. 4, 1–18 (California State University, Fresno, 1977).

Salem, P. J. The Complexity of Human Communication: Second Edition, 2nd ed., 266 (Hampton Press, 2012).

Binz, M. & Schulz, E. Using cognitive psychology to understand gpt-3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218523120 (2023).

Stevenson, C., Smal, I., Baas, M., Grasman, R. & van der Maas, H. Putting GPT-3’s creativity to the (alternative uses) test. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.08932 (2022).

Seals, S. & Shalin, V. Evaluating the deductive competence of large language models. Proc. NAACL HLT 1, 8614–8630 (2024).

Han, S. J., Ransom, K. J., Perfors, A. & Kemp, C. Inductive reasoning in humans and large language models. Cogn. Syst. Res. 83, 101155 (2024).

Su, J., Lang, Y. & Chen, K.-Y. Can AI solve newsvendor problem without making biased decisions? A behavioral experimental study. SSRN Electronic Journal (2023).

Tang, Z. & Kejriwal, M. Humanlike cognitive patterns as emergent phenomena in large language models. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.15501 (2024).

Mitchell, M. Complexity: a guided tour (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Salem, P. J. The complexity of human communication (Hampton Press, 2009).

Lang, A. Dynamic human-centered communication systems theory. Inf. Soc. 30, 60–70 (2014).

Lang, A. & Ewoldsen, D. Beyond effects: Conceptualizing communication as dynamic, complex, nonlinear, and fundamental. in Rethinking Communication: Keywords in Communication Research, 111–122 (Hampton Press, 2010).

Berger, C. R. Making a differential difference. Commun. Monogr. 77, 444–451 (2010).

Steyvers, M. et al. What large languagemodels know and what people think they know. Nat. Mach. Intell. 7, 221–231 (2025).

Boggust, A., Hoover, B., Satyanarayan, A. & Strobelt, H. Shared interest: measuring human-ai alignment to identify recurring patterns in model behavior. In Proc. 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–17 (Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), New York, 2022).

Ji, J. et al. AI alignment: a contemporary survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 58, 132 (2025).

Gabriel, I. Artificial intelligence, values, and alignment. Minds Mach. 30, 411–437 (2020).

Vamplew, P., Dazeley, R., Foale, C., Firmin, S. & Mummery, J. Human-aligned artificial intelligence is a multiobjective problem. Ethics Inf. Technol. 20, 27–40 (2018).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education & Committee on the Science of Science Communication: A Research Agenda. Communicating science effectively: a research agenda (National Academies Press, 2017).

European Food Safety Authority et al. Guidance on communication of uncertainty in scientific assessments. EFSA J. 17, e05520 (2019).

Schneider, S. Communicating uncertainty: a challenge for science communication. in Communicating Climate-Change and Natural Hazard Risk and Cultivating Resilience: Case Studies for a Multi-Disciplinary Approach, 267–278 (Springer, 2016).

Arjona-Martín, J.-B., Méndiz-Noguero, A., & Victoria-Mas, J.-S. Virality as a paradigm of digital communication. Review of the concept and update of the theoretical framework. Prof. info. 29, e290607 (2020).

Berger, J. & Milkman, K. L. What makes online content viral? J. Mark. Res. 49, 192–205 (2012).

McLuhan, M. Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man (MIT Press, 1994).

Tao, Y., Viberg, O., Baker, R. S. & Kizilcec, R. F. Cultural bias and cultural alignment of large language models. PNAS Nexus 3, pgae346 (2024).

Van Niekerk, D. et al. Challenging Systematic Prejudices: an Investigation into Bias Against Women and Girls (UNESCO, IRCAI, 2024).

Baidu’s ernie-4.0. https://yiyan.baidu.com/.

Zhang, B., Haddow, B. & Birch, A. Prompting large language model for machine translation: a case study. In Proc. International Conference on Machine Learning, 41092–41110 (PMLR, 2023).

Kocmi, T. et al. Findings of the 2023 conference on machine translation (wmt23): Llms are here but not quite there yet. In Proc. Eighth Conference on Machine Translation, (eds koehn, P., Haddow, B., Kocmi, T. & Monz, C.) 1–42 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Singapore, 2023).

Mauboussin, A. & Mauboussin, M. J. If you say something is likely, how likely do people think it is? Harv. Bus. Rev. 3, 2018 (2018).

Li, C. N. & Thompson, S. A. Mandarin Chinese: a Functional Reference Grammar (University of California Press, 1989).

Hewitt, J., Liu, N. F., & Liang, P., Manning, C. D. Instruction following without instruction tuning. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.14254 (2024).

Wei, J. et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 24824–24837 (2022).

Kojima, T., Gu, S. S., Reid, M., Matsuo, Y. & Iwasawa, Y. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 22199–22213 (2022).

Van Veen, D. et al. Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization. Nat. Med. 30, 1134–1142 (2024).

Subramanian, C. R., Yang, D. A. & Khanna, R. Enhancing health care communication with large language models–the role, challenges, and future directions. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e240347–e240347 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. The effect of using a large language model to respond to patient messages. Lancet Digit. Health 6, e379–e381 (2024).

OECD. The Path to Becoming a Data-driven Public Sector (OECD Publishing, 2019).

Li, S. et al. SciLitLLM: how to adapt LLMs for scientific literature understanding. NeurIPS Workshop Found. Models Sci. (2024).

Aoki, G. Large language models in politics and democracy: a comprehensive survey. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.04498 (2024).

Clusmann, J. et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Commun. Med. 3, 141 (2023).

Abraham, W. Modality in Syntax, Semantics and Pragmatics, 165 (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Kotek, H., Dockum, R. & Sun, D. Gender bias and stereotypes in large language models. In Proc. ACM Collective Intelligence Conference, 12–24 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations, 1–15 (2023).

Trivedi, H., Balasubramanian, N., Khot, T. & Sabharwal, A. Interleaving retrieval with chain-of-thought reasoning for knowledgeintensivemulti-step questions. In Proc. 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistic, Vol. 1, 10014–10037 (2023).

Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases: biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science 185, 1124–1131 (1974).

Sileo, D. & Moens, M.-F. Probing neural language models for understanding of words of estimative probability. Proc. 12th Jt. Conf.Lex. Comput. Semant. 469–476 (2023).

Rogers, A., Kovaleva, O. & Rumshisky, A. A primer in bertology: what we know about how bert works. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 8, 842–866 (2021).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proc. NAACL HLT 1, 4171–4186 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Aligning large language models with human: a survey. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.12966 (2023).

Zimmerman, J. W. et al. Tokens, the oft-overlooked appetizer: Large language models, the distributional hypothesis, and meaning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.10924 (2024).

Foertsch, J. & Gernsbacher, M. A. In search of gender neutrality: is singular they a cognitively efficient substitute for generic he? Psychol. Sci. 8, 106–111 (1997).

Kiritchenko, S. & Mohammad, S. Examining gender and race bias in two hundred sentiment analysis systems. In Proc. Seventh Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics, 43–53 (2018).

Zhao, J., Wang, T., Yatskar, M., Ordonez, V. & Chang, K.-W. Gender bias in coreference resolution: evaluation and debiasing methods. Proc. NAACL HLT 2, 15–20 (2018).

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F. & Fenning, C. D. Ethnologue: Languages of the World (SIL International Global Publishing, 2015).

Hawkins, J. A Comparative Typology of English and German: Unifying the Contrasts (Routledge, 2015).

Li, Z. et al. Quantifying multilingual performance of large language models across languages. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.11553 (2024).

Wen-Yi, A. W., Jo, U. E. S., Lin, L. J. & Mimno, D. How Chinese are Chinese Language Models? The puzzling lack of language policy in China’s LLMs. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.09652 (2024).

Cedille AI. Cedille AI API. https://cedille.ai/api.

Wei, Y. & Wang, Y. Expressing stance: a cross-linguistic study of effective and epistemic stance marking in Chinese and English opinion reports. J. Pragmat. 240, 18–34 (2025).

Hong-yan, Z. Comparative analysis of modal auxiliary verbs in English and in Chinese. Sino-US Engl. Teach. 12, 128–136 (2015).

Lau, L.-Y. & Ranyard, R. Chinese and English speakers’ linguistic expression of probability and probabilistic thinking. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 30, 411–421 (1999).

Kullback, S. & Leibler, R. A. On information and sufficiency. Ann. Math. Stat. 22, 79–86 (1951).

Mann, H. B. & Whitney, D. R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 18, 50–60 (1947).

Brunner, E. & Munzel, U. The nonparametric Behrens-Fisher problem: asymptotic theory and a small-sample approximation. Biom. J. 42, 17–25 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded under the DARPA Machine Common Sense (MCS) program under award number N660011924033.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.T. was responsible for writing, experimental design, figures, experiments, and analysis. M.K. was responsible for conception, revision, and project supervision. K.S. conducted and assisted with experiments and writing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions