Abstract

Plant growth-promoting microbes (PGPM) are promising biostimulants to enhance plant growth and promote sustainable production practices. PGPM can be a single species or a mix of microbes. This study examined the effects of beneficial single bacterial species and a mix of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) plus their microbiome (AMFc) from a wild chrysanthemum relative on a commercial chrysanthemum cultivar. We tested the synergistic effect of combining AMFc with two bacterial strains (SMF006 and SMF018) on plant growth, root architecture, and rhizosphere microbiome during early development. Our results showed AMFc significantly increased root surface area, diameter, volume, and biomass. Co-inoculation with SMF006 increased root dry biomass by 75% and shaped the microbial community, enriching beneficial bacteria (Sphingomonas, Taibaiella) and fungi (Trichoderma, Penicillium). These findings demonstrate that the combination of AMFc and the SMF006 strain enhances early-stage growth of chrysanthemum cuttings, indicating its potential as a bioinoculant strategy for sustainable horticultural production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants’ existence is closely intertwined with their microbiome. This relationship is recognized as “co-evolved entities” or “holobionts”, involving bacterial, archaeal, fungal, and other eukaryotic microorganisms1,2,3,4. These associations are intricate, dependent on the host cultivar5,6, and specific environmental conditions7. These microorganisms can enhance plant growth and development through various mechanisms, including increasing nutrient availability8,9, producing growth hormones, and alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses10,11,12,13. For that reason, they are called plant growth-promoting microbes (PGBM). Common types of PGPM include bacteria, plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) such as the specialist Rhizobia14 and the generalists Bacillus sp15., Pseudomonas sp16., and Azospirillum sp17. Fungi can also promote plant growth, plant growth-promoting fungi (PGPF) such as Trichoderma sp18., Penicillium sp19., as well as soil yeasts Rhodotorula sp. and Candida sp20. One fungal group of well-studied is the plant symbiont arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), belonging to the Glomeromycota phylum, which colonize the majority of terrestrial plant roots and provide nutrients in exchange for plant photosynthates, forming specialized mycorrhizal structures21,22.

AMF have the capacity to select coexistence with a diverse array of microbial taxonomic groups within various stages of their life cycle and across a wide spectrum of soil environments1. Numerous studies have highlighted the positive impact of microbes on the establishment and functionality of mycorrhizal symbioses. Mycorrhizal helper bacteria (MHB) have been identified as key facilitators of these interactions by enhancing fungal colonization, improving nutrient exchange efficiency, and stimulating hyphal growth23. These bacteria can promote crop growth by producing signaling molecules, modulating plant hormone levels, or improving phosphorus solubilization and uptake. MHB have been identified as key players in enhancing these symbiotic interactions24. These microbes are integral components of both the mycorrhizosphere and the hyphosphere, contributing to the intricate network of interactions that support the success of mycorrhizal associations25,26,27. Applying the beneficial microorganisms can improve crop yield and quality28,29, offering a promising alternative to conventional agricultural practices30. Studies on beneficial microbes that positively interact with plants have primarily focused on single species as inoculants31. We call this strategy one-for-all because it is based on a single isolate to deliver a series of potential benefits to the plant. Single-species inoculants offer a targeted, straightforward approach to improve specific plant growth functions, but they show limitations due to competition with native soil communities8, and are less adaptive to changing conditions. Commercial products predominantly rely on single species, resulting in inconsistencies in quality and efficacy in the field32. On the other hand, microbial consortium inoculation has emerged as a strategy aimed at safeguarding multiple ecosystem services such as tolerance to abiotic stress, increase of photosynthesis rates, and nutrient mobilization28,29. Here, we call this strategy all-for-one because a set of different microbes is used to promote plant growth. These microbial consortia, also known as co-inoculations, synthetic community (SymCom), involve combinations of PGPM to enhance plant growth32,33,34. These consortia are composed of compatible diverse microbial strains with diverse traits and modes of action, functions, and secondary metabolites13, selected to adapt to different environmental conditions35. Specific microbial members of the consortia can selectively be activated in response to signals from the plant’s rhizosphere, and consequently, their physiological responses, result in beneficial effects on plant growth36. Numerous reports from greenhouse and field experiments conducted on various plant species using combinations involving mixed microbial communities, including bacterial species37, AMF species38,39, AMF combined with bacteria40,41,42,43,44, and AMF combined with fungi45,46,47 where they consistently report improvements in plant biomass, nutrient uptake, stress tolerance, and disease resistance.

This study aimed to determine the effect of single bacterial species (one-for-all), AMF species combined with their associated microbiome (AMFc, all-for-one), and the co-inoculation of single bacterial species with AMF combined with their microbiome on chrysanthemum growth. By accounting for the contribution of the associated microbiome in arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation, we expand the currently available knowledge by providing more detailed information on the ecological functions and the plant growth promotion potential of those associated microbes.

The single microbes were isolated from a wild relative of chrysanthemum while the AMF community was obtained from the soil surrounding the same plant. The single bacterial isolates SMF006 and SMF0018 strains, were previously characterized as PGPB, exhibiting high activity in key growth-promoting traits, such as siderophore production, phosphate solubilization, and IAA production5.

Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum indicum L.), a vegetatively propagated and heavily bred species, was used to study rhizosphere bacterial and fungal community assembly in 22-day-old roots from cuttings. This early rooting phase is critical for establishing a healthy root system, yet root-microbiome interactions during this stage remain poorly understood.

The inoculations were on chrysanthemum commercial cultivar ‘Chic Cream’ under controlled growth chamber conditions in a substrate without nutrient addition. We analyzed the effect of inoculations on plant biomass, root architecture, and rhizosphere microbiome assembly and predicted microbial functions. Furthermore, joint models were applied to disentangle the additive contributions of these different microbial inoculants to promote plant growth at the early stage of chrysanthemum cutting.

Results

PGPM inoculation effects on shoot and root biomass, and root phenotype

We determined the effects of single bacterial isolates SMF006 and SMF018, AMF+accompany community (AMFc), and the combination of AMFc+SMF006 and AMFc+SMF018 on shoot and root dry biomass, as well as root architecture in the Chic Cream chrysanthemum cultivar. Although no significant differences were observed in shoot biomass in the different treatments (Supplementary Fig. 1), notable variations were observed in root biomass and architecture. None of the PGPM inoculations showed a negative impact compared to the control, and specific root variables showed statistically significant increases. Specifically, four root variables responded to the treatments, indicating the presence of distinct effects of PGPM on root development (Fig. 1): Root dry weight (g), root surface area (cm2), average root diameter (mm), and root volume (cm3). The co-inoculation of AMFc+SMF006, co-inoculation of AMFc+SMF018, and inoculation of AMFc had significant increases among all the treatments in terms of root dry weight (Fig. 1a), root surface area (Fig. 1b), average root diameter (Fig. 1c), and root volume (Fig. 1d). In particular, the combination of AMFc+SMF006 resulted in 75.4% increase in root dry weight when compared to the control. Treatment AMFc+SMF018 significantly increased (48.72%) in root dry weight compared to the control treatment, while treatment AMFc exhibited a 49.17% increase in root dry weight. The single isolates SMF006 and SMF018 showed a significant increase of 18.92% and 23.31%, respectively, only for root dry weight. Regarding root surface area, average diameter and root volume, the treatment AMFc exhibited the highest increase. No significant differences were observed in length, specific root length, and specific root area (Fig. 1e–g).

Cuttings were inoculated with single bacterial isolates SMF006 and SMF018, AMFc (AMF+accompany microbiome) and co-inoculations AMFc+SMF006, AMFc+SMF018 on a Root dry weight, b Root surface area, c Average root diameter, d Root Volume, e Length; f SRL Specific root length; g SRA, Specific root area of chrysanthemum cuttings. Each color represents a different inoculum. Treatments with the same letter are not significantly different compared to the control (Tukey-test, p < 0.05). * means treatments significantly different from the control (Tukey-test, p < 0.05).

Rhizosphere microbiome assembly after inoculation with bacterial single strains, AMFc, and the co-inoculations of AMFc and single strains

To determine the microbial profiles in the rhizosphere of chrysanthemum after different treatments, we utilized the GJAM model (Fig. 2). Positive coefficients in the model represent microbial groups that were found to be significantly different and selected in the rhizosphere of each treatment. Conversely, negative coefficients denote microbial groups that were significantly different but not selected in the rhizosphere of each treatment. PCA shows the bacterial and fungal chrysanthemum rhizosphere community profiles inoculated with single bacterial strains (SMF006 and SMF018), AMFc, and in co-inoculations (AMFc+SMF006 and AMFc+SMF018). Each dot on the plots represents the microbial profile of a specific treatment. All the inoculations had a significant impact on both bacterial and fungal community composition compared to control.

PCA showing the differences in the bacterial (a) and fungal (c) community assembly in chrysanthemum rhizosphere after inoculation with single bacterial isolates SMF006, SMF018, AMFc and their combinations (AMFc+SMF006, AMFc+SMF018). Each dot represents the microbial community profile (n = 4). Heatmaps of the regression coefficients show the significant shifts (positive in blue and negative in red) of bacterial (b) and fungal (d) microbial profiles.

Regarding the bacterial community, the first two axes of the PCA explained 67.3% and 20.8% of the total variability in the bacterial community after inoculation. Among the treatments, the control group stood out, while the most substantial impact on bacterial composition was after AMFc inoculation. The effect of the single bacteria strain inoculation on bacterial community in the rhizosphere varied depending on their identity, with a lower bacterial community shift in plants inoculated with SMF018 strain than SMF006. SMF006 strain significantly shaped the rhizosphere bacterial community when solely inoculated or co-inoculated with AMFc (Fig. 2a). The heatmap based on regression coefficient values from the GJAM model illustrates different clusters: Cluster 1 composed by control samples, Cluster 2 by AMFc, SMF018, and AMFc+SMF018 samples, and Cluster 3 by SMF006 and AMFc+SMF006 samples (Fig. 2b).

Regarding the fungal community assembly in the rhizosphere, the first two axes of the PCA explained 76.5% and 14% of the total variability after inoculations with single bacterial strains, AMFc, and their combinations (Fig. 2c). AMFc inoculation had the most significant impact on the fungal community. SMF018 strain inoculation exhibited a minimal shift compared to the control samples in the fungal rhizosphere community assembly. On the other hand, SMF006 strain inoculation tended to define a distinct community, both when analyzed individually and in combination with AMFc (Fig. 2c). Based on the clustering analysis illustrated by the heatmap, three distinct clusters were identified: Cluster 1 consisted of control and SMF018 strain inoculated samples, Cluster 2 encompassed SMF018, AMFc, and AMFc+SMF018 inoculated samples, and Cluster 3 comprised SMF006 and AMFc+SMF006 inoculated samples (Fig. 2d).

Shifts in assembly of the rhizosphere community inoculated with AMFc and their combinations with single bacterial strains

The main microbial profile change found in the rhizosphere for both bacterial and fungal profiles was after AMFc and the co-inoculations (AMFc+SMF006, AMFc+SMF018) compared to control. Specifically, for the AMFc treatment, a total of 194 bacterial and 32 fungal groups increased their abundances, followed by a decrease of 63 bacterial and 18 fungal groups (at the genus level) in the rhizosphere compared to control. The most abundant bacterial Phyla were Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, Proteobacteria, and Firmicutes. The five most abundant genera were Massilia, Pseudomonas, Azospirillum, Opitutus, and Paraburkholderia. We identified specific shifts in the bacterial community when AMFc were combined either with SMF006 or SMF0018 strains. The inoculation of AMFc+SMF006, promoted positive shifts of Taibaiella and Sphingoaurantiacus and negative shifts of Azospirillum and Pseudomonas in the rhizosphere bacterial community while the inoculation of AMFc+SMF018, increased only positive shifts of genera Glutamicibacter, Sphingomonas, and Bordetella (Fig. 3). Figure 3

Shifts in bacteria abundance based on regression coefficients of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) in chrysanthemum rhizosphere inoculated with AMFc (dots) and the combinations of AMFc+ single bacterial strain (arrows) compared to control. Dots represent the microbes that are significantly influenced by AMFc inoculation, arrows represent the microbes that are significantly influenced by the co-inoculation AMFc and single bacterial strain (SMF006 in green, SMF018 in red).

Regarding the fungal community, the main phyla present in the AMFc treatment were Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mortierellomycota. The most abundant genera were Penicillium, Trichoderma, and Talaromyces. After the AMFc+SMF006 inoculation, we observed three notable positive shifts in the community, specifically an increase in the abundance of Trichoderma, Talaromyces, and Penicillium. Conversely, we observed a negative shift in the phylum Ascomycota, as well as in the genera Rozellomycota and Rhodotorula. In the case of AMFc+SMF018 inoculation, we observed an increase in the fungal genera Trichoderma, indicating its positive response to this particular inoculation combination. Additionally, we noted a negative shift specifically in the taxon Rozellomycota (Fig. 4).

Shifts in fungal abundance based on regression coefficients of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) in chrysanthemum rhizosphere inoculated with AMFc (dots) and the combinations of AMFc+ single bacterial strain (arrows) compared to control. Dots represent the microbes that are significantly influenced by AMFc inoculation, arrows represent the microbes that are significantly influenced by the co-inoculation AMFc and single bacterial strain (SMF006 in green, SMF018 in red).

The presence of AMF was analyzed through root staining and molecular sequencing. The AMF colonization was not found in the replicates of control and single bacterial inoculation treatments. A low score of <10% of colonization was found in the roots of plants inoculated with AMFc and combinations (Supplementary Fig. 2). The molecular sequencing of the AMF small subunit (SSU) specific region sequences allowed us to track the presence of AMF from the community inoculated on chrysanthemum. For the treatments AMFc, AMFc+SMF006, and AMFc+SMF0018, the sequence data showed the presence of the Genera Glomus and Paraglomus and not assigned genera belonging to the family Glomeromycetes in the rhizosphere of chrysanthemum (Fig. 5).

Predicted bacterial and fungal functions

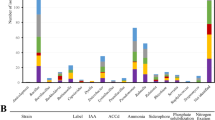

We employed FAPROTAX and FunGuilds with a specific goal. Rather than reanalysing gene abundance data according to their potential functions and guilds, we harnessed this information to gain insights into the potential functions linked to microbial taxa that exhibited shifts as observed from the GJAM analysis. Our approach involved tallying the number of taxa within each functional group that displayed either positive or negative shifts in response to the treatments (single isolates, AMFc, and co-inoculations). By doing so, we obtained valuable information about how specific microbial functions and guilds were selected in the rhizosphere as a result of the different treatments.

All the 262 bacteria genera found in the rhizosphere of plants inoculated with single isolates, AMFc, and co-inoculations were assigned to function using FAPROTAX. This resulted in 36.9% of the total bacterial genera could be assigned to functions. The functional profiles of bacteria in the rhizosphere that was inoculated with AMFc, SMF006, SMF018, and co-inoculations (AMFc+SMF006, AMFc+ SMF018) were significantly different from that of the control. AMFc inoculation reshaped bacterial taxa which showed functions associated with 20 potential functions. The main change was for nitrogen fixation, nitrate reduction, fermentation, and ureolysis (Fig. 6). Taxa that exhibited this potential function in the control group were replaced by other taxa introduced by AMFc inoculation. Single inoculation of SMF018 had three positive shifts in symbionts, nitrate reduction, nitrate respiration, and nitrogen respiration while single inoculation of SMF006 had a negative shift in symbionts. On the other hand, when single bacterial isolates were co-inoculated with AMFc, their impact on the functional diversity of bacteria was less pronounced. When AMFc was co-inoculated with single isolates, the function selected after AMFc+SMF006 was the positive shift in symbionts. In contrast, co-inoculation with AMFc+SMF0018 resulted in two negative shifts, nitrogen fixation and ureolysis.

FunGuilds assigned one or more guilds to 65.9% of the 97 fungal genera used in our model. Similarly to bacterial potential functions, we observed the most significant changes in potential fungal functions after the AMFc inoculation, with eight functions being influenced by taxa displaying positive and negative coefficients. The main functional changes were undefined saprotroph, endophyte and wood saprotroph (Fig. 7). Specifically, both single inoculations of SMF006 and SMF018 showed a positive shift in one taxon assigned to undefined saprotroph. Following co-inoculations, we identified a specific changes related to functional guilds of endophyte, wood saprotroph, and epiphyte after AMFc+ SMF006 (four positive shifts and one negative shift), and six after AMFc+SMF018, undefined saprotroph, endophyte, wood saprotroph, and epiphyte (five positive shifts and one negative shift).

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to compare different strategies of inoculating plant beneficial microbes to promote plant growth at the early stage of chrysanthemum cuttings. The first one, which we called one-for-all, consisted of the use of single bacterial isolates, SMF006 and SMF018, capable of promoting plant growth due to their traits of plant growth. The second strategy, the all-for-one, consisted of the use of complex communities inoculated to promote plant growth via a synergistic interaction between the added microbes. Our all-for-one inoculum consisted of the AMF, which contains not only the spores and hyphae of AMF species but an accompanying microbiome. We considered our AMF + accompanying microbiome inoculation, which we named AMFc, consisting of an already complex and likely stable bacterial and non-mycorrhizal fungal community associated with AMF. Our results revealed that inoculation with more complex communities led to an increase in root traits, and stronger shifts in the plant rhizosphere microbiome and potential predicted bacterial and fungal functions.

We observed that single bacterial inoculation did not significantly enhance chrysanthemum growth. SMF006 and SMF018 isolates as single inoculations did not result in a significant impact on plant biomass and root architecture compared to the control treatment. The SMF018 strain, genetically similar to Pseudomonas sp. RBE1CD-131, exhibited no significant effect on the performance of the chrysanthemum cultivar ‘Chic Cream’, nor on the bacterial and fungal community assembled in the rhizosphere, as observed in a controlled substrate of sterilized vermiculite without added nutrients. One plausible explanation for this lack of success of SMF018 in promoting plant growth could be the absence of roots during the initial stages of cutting development. It is crucial to acknowledge that, despite being a Gram-negative and widely distributed environmental bacterium with adaptability to various conditions, this Pseudomonas strain finds its primary colonization niche within the root system of plants where it was isolated from ref. 5. The SMF006 strain, genetically similar to Priestia megaterium, had no impact on the growth of chrysanthemum.

In contrast, the utilization of a community of AMF was the main driver of root phenotypic changes in chrysanthemum, having an increase in root surface area, root average diameter, root volume, and root dry biomass. Root surface area can serve as a valuable index, providing insights into factors like root nutrient uptake and water absorption potential48, and the diameter of roots directly reflects the allocation of plant biomass to the root system49. The growth of adventitious roots is crucial for successfully propagating cuttings and creating a well-structured root system is important for providing enough nutrients to the cuttings50. This rooting phase holds pivotal importance in the overall growth of chrysanthemum plants, serving as an indicator of root capacity and marking the initial interactions between the soil microbiome and plant roots51. Notably our inoculated complex community, a mixture of microbes that are commonly used in other all-for-one strategies such as synthetic communities (SynComs)52.

Additionally, we performed a co-inoculation of the AMFc together with each of the isolates and found potential synergistic effects. Interestingly, we found that the highest increase in the root dry biomass reached 75% when the cuttings were inoculated with the combination of AMFc+SMF006. This increase was bigger than the solely AMFc treatment (49%) and single isolate only. Besides, AMFc+SMF006 co-inoculation resulted in increase of chrysanthemum root growth and architecture. In line with our findings, previous studies reported a trend of increased root biomass at similarly high percentages (>80%) and change in root architecture after co-inoculations of PGPM compared to single isolates in different plant species44,53,54. Similarly, a recent study demonstrated that the combined application of AMF and Devosia sp. ZB163 exhibits superior growth promotion effects compared to inoculation of the single isolates55.

This influence on root traits could stem from the ability of AMF to modify the structure, spatial arrangement, quantity, and timing of the root system in host plants even at early stages of plant development56. Typically, mycorrhizal associations improve root system morphology traits by regulating levels of plant growth regulators such as endogenous indole-3-butyric acid and polyamines57. Accumulating evidence suggests that plants can detect currently unidentified signaling molecules from AMF58,59, which helps them prepare for symbiotic interaction60. Among the known signals, lipochitooligosaccharides (Myc-LCOs) are key fungal-derived molecules that trigger presymbiotic responses in the host root61. The presymbiotic stage refers to the early phase of AM symbiosis that occurs before physical contact or colonization of the plant root by the fungus. During this stage, molecular signals are exchanged between plant roots and AM fungi, initiating physiological and developmental changes that prepare both partners for successful symbiosis62. Notably, alterations in root system architecture induced by AMF signaling exchange during the presymbiotic stage are sufficient to trigger changes in other plant species, like Medicago truncatula63, and rice64, where lateral root formation is stimulated in response to these early fungal signals. Our study provides further support for this impact by showing similar effects in chrysanthemum.

The AMFc inoculum utilized in this study encompassed both AMF and the associated microbiome. Therefore, the effects of AMF on plant growth should also account for the beneficial role of its associated microbial community. The beneficial effects of AMF-associated microbiome (AMFc) may not always be limited to the formation and functioning of mycorrhizal associations, but they can have plant growth-promoting activities connected to phytohormones, enhanced nutrient acquisition, activity against plant pathogens, and natural biofilms formation65. AMFc also plays an important role in root development. Stimulation of root formation is a frequent characteristic of AMF-associated bacteria. This effect could stimulate mycorrhiza formation by increasing the number of lateral roots that can be infected by the fungus. It can directly be caused by auxin and ethylene-producing bacteria modulating root development66. In this study, complex communities impacted root traits more than single isolates, and this effect was also reflected in the microbial rhizosphere composition.

Previous reports showed that some PGPM could indirectly impact soil microbial community composition and function by stimulating the population densities of specific soil-borne microorganisms9, and thereby have the potential to promote plant growth and health47,67,68. Our current analysis of the GJAM regression coefficient analysis showed that SMF018 presented the weakest capacity to influence both bacterial and fungal rhizosphere microbiome assembly in chrysanthemum cuttings compared to control. On the other hand, the inoculation of SMF006 isolate resulted in bigger changes in the microbial community in the chrysanthemum rhizosphere, both when inoculated individually and in combination with AMFc. The isolate SMF006 genetically close to Priestia megaterium, was isolated from the endosphere of a wild relative of chrysanthemum. Priestia spp. are fast-growing Gram-positive bacteria often assumed to colonize and remain competent in a wide range of soil types, thereby occupying specialized endosphere and rhizosphere niches69,70. Therefore, the success of the single inoculation strategy largely depends on the identity of the inoculant.

For the inoculation of a complex community, the AMFc treatment was the primary factor influencing the rhizosphere community assembly of AMF, bacteria, and non-mycorrhizal fungi. The AMF genera found in the rhizosphere of chrysanthemum after AMFc inoculation were Glomus and Paraglomus and not assigned genera belonging to the family Glomeromycetes.

The more represented genera of bacteria in chrysanthemum found in the rhizosphere after AMFc inoculation, namely, Massilia, Pseudomonas, Azospirillum, Opitutus and Paraburkholderia were often found in AMF associations in other studies71,72. These include Pseudomonas and Paraburkholderia, as observed across various research investigations40,73.

There have been fewer studies conducted on the non-mycorrhizal fungi associated with AMF. Our study shows that Penicillium, Trichoderma, and Talaromyces, were the most abundant fungal genera found in chrysanthemum rhizosphere after AMFc treatment. These fungal genera are non-pathogenic soil-inhabitant fungi46, falling in the category of PGPF. The beneficial effects of these fungal species on plants include the promotion of their growth, improvement of root development, and phytohormones and phytoregulators production74. In addition to these advantages, these fungal genera also contribute to phosphorus solubilization, and they exhibit a stimulating effect when coexisting with AMF75.

We noticed that the positive shifts after co-inoculations with both single isolates and AMFc were targeting groups of specific bacteria and fungi already present in the AMF accompany microbiome (AMFc). Specifically, the AMFc+SMF006 treatment increased abundances of bacterial genera Sphingomonas and Taibaiella and fungal genera Trichoderma, and Penicillium in the rhizosphere. Isolates from these genera have been noted for their plant growth promotion traits and their association with AMF. The study by Lecomte et al.76 found that Sphingomonas can thrive on both AMF spores and hyphae.

In line with the study of Wang et al.68, the additive inoculation of a single PGPB with beneficial traits was able to affect a mixed-established community and improve plant growth. Interestingly, the results showed a synergistic effect on the abundance of the fungal genus Trichoderma that increased after both isolates co-inoculations, with a bigger change after AMFc+SMF006 treatment. The interaction between Trichoderma was studied with Pseudomonas and Bacillus showing a synergistic effect on plant benefits77. This synergy might be mediated by complementary PGP traits, such as the production of phytohormones, siderophores, and phosphate solubilization.

Our finding aligns with earlier studies demonstrating that certain PGPB can function as cooperative partners, enhancing indigenous beneficial bacterial populations and contributing to plant growth promotion33,78. A better understanding of the exact nature of the molecular dialog between these rhizosphere partners and how their combined action serves to confer plant growth-promoting and microbial community reshaping is left as an avenue for future investigations, potentially tracking nutrient concentrations and using transcriptomic and proteomic approaches. The context-dependency and long-term effect of these inoculations need to be further studied as well. Altogether, our research expands the study of synergistic associations between microbes by including both AMF and non-mycorrhizal fungi.

Importantly, within the AMFc treatment, specific bacterial taxa linked to nitrogen-related functions, such as nitrogen fixation, nitrate reduction, and ureolysis, as well as carbon cycle processes like fermentation, responded to the inoculation. In rhizosphere communities, nitrogen fixation, nitrate reduction, and ureolysis are essential processes for plant development. Free Nitrogen-fixing bacteria frequently found associated with AMF79,80 contribute to atmospheric nitrogen fixation and, in synergy with AMF, significantly enhance plant nutrient absorption81.

Similarly to the changes observed from FAPROTAX, FunGuilds indicated the increase of specific taxa of fungi belonging to guilds of saprotrophic, epiphytic, and endophitic fungi after AMFc treatment. The selection of specific taxa within the saprotrophic fungi guild suggests the adaptation of the inoculated microbial community to the composition of the substrate used in our current experiment. This substrate consisted of a sterilized vermiculite and sand mixture, including residues of AMF inoculum such as spores, hyphae, and fragments of colonized roots. Saprotrophic fungi, especially those with wood-degrading capabilities, are known to break down vermiculite and feed on decaying plant matter82. This dual function of degrading the substrate and utilizing residual AMF components might have led to their role in shaping the rhizosphere environment.

In summary, the application of AMFc emerged as the primary driver of functional alterations of bacterial functions and fungal guilds, whereas the single isolates induced changes but is species-dependent. Thus, by exploring the potential functions and ecological roles of the bacteria and fungi present in the rhizosphere of inoculated plants, our work sheds light on the potential functional interactions between AMF and specific microbes.

In our investigation, our one-for-alll approach was limited to bacterial isolates, as we refrained from considering AMF as a single species. This decision was prompted by our sourcing of AMF spores from natural soil and their propagation from trap culture, rather than individual propagation in vitro. Even under controlled in vitro conditions, achieving sterile spores is challenging due to the presence of endosymbionts within AMF spores83,84. Furthermore, using LB medium to propagate the isolate could potentially provide some nutrient-rich media to microbes already present in the seed microbiome. Moreover, the complexity of preserving all endosymbionts without compromising biodiversity and functionality presented an additional obstacle. Consequently, the notion of AMF serving as a single isolate inoculation approach was deemed unfeasible. Instead, our study emphasized the role of AMF within a complex community. To fully leverage the diversity of AMF and advance microbial inoculants, it is essential to enhance the isolation and cultivation of unexplored AMF taxa from natural soils85. This must consider the associated microbiomes and further research is needed to recognize context dependencies, such as variations in nutrient levels and plant hosts.

The influence of soil type, environmental conditions, and broader plant varietal responses was not addressed in this current study, areas that warrant further investigation. Additionally, the long-term effects of microbial inoculations across the full production cycle remain unknown. Future research should explore how different microbial combinations over time and under varying conditions, and how inoculation strategies can be optimized to maximize plant growth and sustainability. Future studies could also investigate the functional contributions of the rhizosphere and hyphosphere microbiota to nutrient cycling and root development. This would provide a clearer understanding of how AMF-associated microbiota in both environments contribute to plant growth and nutrient dynamics.

Beneficial relationships between strains observed in this study are promoted by the following facts: (i) AMFc contained accompany bacteria and fungi have specific complementary functions, such as nitrogen and carbon metabolisms able to induce root development and biomass, and (ii) co-inoculation of AMF + SMF006 (similar to P. megaterium) reshapes the rhizosphere community, increasing the abundance of specific PGPM already present in the AMFc inoculum, synergistically contributing in promoting plant growth. Co-inoculation targets specific groups of microbes intensifying some taxa (e.g., increasing the abundance of Thricoderma). In summary, the AMFc treatment (all-for-one), being a community impacted the root development, chrysanthemum rhizosphere microbiome composition and potential functions related to nitrogen and carbon metabolism. The addictive effect of single isolates varied on their identity and impacted specific beneficial bacterial and fungal taxa in the rhizosphere of chrysanthemum. These findings highlight the potential of combinations of AMFc and SMF006 as a valuable tool for promoting and maximizing plant growth during the critical early stage of chrysanthemum cutting development. This approach can modify the composition and functionality of the chrysanthemum rhizosphere microbiome to foster more favorable conditions for plant development.

Materials and methods

Inoculation of bacterial isolates, AMF + accompany microbiome and their combinations We tested the inoculation effects of single bacterial species (SMF006 and SMF0018), AMF + accompany microbiome (from now on we call “AMFc”), consisting of an already complex and likely stable bacterial and non-mycorrhizal fungal community associated with AMF5, and the combination of either SMF006 or SMF0018 with AMFc (Fig. 8). The two bacterial strains, SMF006 and SMF0018 as well as the AMFc were isolated from rhizosphere of wild chrysanthemum plants and bulk soil surrounding the plants growing in natural grassland (Ede, the Netherlands). The strain SMF006 is 98% similar with Priestia megaterium strain EGI278, strain SMF018 is 97% similar to Pseudomonas sp. RBE1CD-131, and the AMFc contains six species (Acaulospora morrowiae, Claroideoglomus etunicatum, Rhizophagus clarus, Funelliformis sp., Glomus sp.1 and Glomus sp.2).

For the single bacterium inoculum, the bacterial isolates SMF006 and SMF018 were collected from individual colonies grown in Petri dishes containing LB medium at 30 °C for 2 days. The bacterial cells of each strain were grown overnight at 31 °C in LB liquid medium and then inoculated again in fresh LB medium until they reached the desired inoculum density (108 CFU mL−1). A volume of 2 mL was used for each bacterial strain, and the bacterial inoculants were directly applied on top of the substrate after placing the chrysanthemum cutting (described below).

AMFc was obtained by trap culture in millet containing AMF propagules (spores, hyphae, and pieces of colonized roots). The inoculum was checked microscopically for the presence and number of viable AMF spores. A total of 80 mL of AMF inoculum was mixed with 200 g of vermiculite substrate per pot (described below) with an average of 3.5 spores mL−1 of soil.

For combinations, the same amount of AMFc inoculum was inoculated either with SMF006 (AMFc+SMF006) or with SMF018 (AMFc+SMF018). The amount of bacterial inoculum was the same as used for single inoculation. For control treatments, the AMFc inoculum was gamma sterilized and mixed with the soil mixture, and 2 mL of sterile LB medium was inoculated.

Chrysanthemum cultivar and pot experiment

Cuttings of chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum indicum L.) cultivar ‘Chic Cream’ were taken from stock plants provided by the breeding company Royal van Zanten BV (the Netherlands). Cuttings of 5 cm in length were treated with 0.5% indolylbutyric acid powder to enhance root formation, which is a commercial management practice for cutting production. The cuttings were placed 2 cm deep in a sterile PVC pot containing 200 g of sterilized vermiculite and sand mixture (v/v 3:1) and maintained in a growth chamber at 16/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod, 80% relative humidity for 22 days at 20 °C. Ten replicates with one cutting per pot for each of the six treatments (SMF006, SMF018, AMFc, AMFc+SMF006, AMFc+SMF018, Control) were established for a total of 60 pots.

Plant biomass, root phenotypic traits, and AMF colonization

Plants were harvested after 22 days for determination of plant biomass. The roots of each replicate (n = 5) per treatment were washed, and the roots and shoots were dried at 60 °C for 48 h for dry biomass measurement. Before drying, the roots were scanned for root architecture traits assessed by WINRHIZO86: Surface Area (cm²), average diameter (mm), length (cm), and root volume (cm3). Specific root length (cm/g) was calculated by dividing root length by root dry weight; the specific root area (cm2 g−1) was calculated by dividing root surface area by root dry weight. The selected root parameters were described to be a proxy for understanding the spatial distribution of roots within the substrate87. The AMF root colonization was determined by staining the roots using the Ink and Vinegar method88 using the five remaining replicates of each treatment. Differences between: root dry weight (g), shoot dry weight (g), root surface area (cm²), average diameter (mm), root length (cm), and root volume (cm3), specific root length (cm g−1), specific root area (cm2 g−1) were analyzed using the ExpDes v1.2.2 package using the function fat2.rbd, to perform a two-way ANOVA with randomized block design89 in R v3.6.190. The normality of the data was checked with Shapiro-Wilk test with 5% significance. The multiple comparison was done using Tukey-test with p ≤ 0.05 considered significant and plotted using ggplot2 v3.2.1 package91.

Rhizosphere microbiome assembly

The rhizosphere was collected from 5 replicates of each plant by carefully removing the whole plant from the pot. Roots were shaken and the rhizosphere was collected using a sterile brush. Soil not in contact with the roots was stored as bulk soil. Rhizosphere and soil were weighted and stored at – 80 °C for further analyses.

Rhizosphere total DNA was extracted with Power Soil Pro kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity and quality of the DNA were checked by ND1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). DNA samples were amplified using the primer set 515 F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 806 R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) for 16S rRNA partial gene (V3–V4 region) for archaea/bacteria, and the primer set ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGT-3′) and ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′) for ITS region for fungi. A nested PCR was performed to target AMF, using the universal primer NS3192 and the fungus-specific primer AM193 for the first PCR, and the primers AMV4.5NF and AMDGR94 for the second PCR.

For the 16S rRNA gene amplification, PCR followed the conditions: an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 26 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s and a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR mix contained 1× of Roche 10× Buffer with 18 mM MgCl2, 5% Roche DMSO, 0.2 mM dNTP mix 10 mM NEB, 0.02 U/μL Roche FastStart High Fi 5U-ul, 0.6 μL of the 515FP, 0.6 μM of the 806RP and sterile Milli-Q water up to the final volume of 25 μL.

For ITS region amplification the PCR conditions were an initial denaturation step at 96 °C for 15 min, followed by 33 cycles of 96 °C for 30 s, 52 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR mix contained 1× of Qiagen 10× Buffer with 15 mM MgCl2, 5% Roche DMSO, 0.2 mM dNTP mix 10 mM NEB, 0.02 U μL−1 Qiagen HotStar Taq 5 U μL−1, 0.6 μM of the ITS1, 0.6 μM of the ITS2 and sterile Milli-Q water up to the final volume of 25 μL. Verification of amplification was performed on 2% agarose gel.

For the AMF amplification, the fragments in the fungal small subunit ribosomal DNA (SSU rDNA) were amplified using the first-round PCR. The universal primer NS31 and AM1 were used as in Higo et al.95. The first PCR round to amplify the 5′ end of the SSU rDNA region for Glomeromycotina. The PCR was performed an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR mix contained 1× of Roche 10× Buffer with 18 mM MgCl2, BSA (20 mg/mL) 0.4 mg/mL, 0.2 mM dNTP mix 10 mM NEB, 0.04 U/μL of Roche FastStart High Fi 5U-ul, 0.6 μM of AurM1, 0.6 μM of the NS31, and sterile Milli-Q water up to the final volume of 25 μL. The first PCR products were diluted 10-fold and used as templates for the second-round PCR. PCR followed the conditions: 1× of Roche 10× Buffer with 18 mM MgCl2, BSA 0.4 mg ml−1, 0.2 mM dNTP mix 10 mM NEB, 0.04 U μL−1 of Roche FastStart High Fi 5U-ul, 0.6 μM of the AMV4.5NF-FwR1, 0.6 μM of the AMDGR-RvR2, and sterile Milli-Q water up to the final volume of 25 μL.

The barcoding step was performed to add an index (or barcode) to each sample and Illumina adapter required for DNA to bind to the flow cell. The PCR was carried out under the following conditions: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 15 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 3 min. The PCR mix contained 2 μL of Roche 10× Buffer without MgCl2, 1.44 μL of Roche MgCl2, 25 mM, 1.00 μL Roche DMSO, 0.40 μl dNTP mix 10 mM NEB, 0.10 μL Roche FastStart High Fi 5 U μL−1 and sterile Milli-Q water up to the final volume of 20 μL. Verification of barcode incorporation for each sample was performed on 2% agarose gel. Quantification of each amplicon was carried out with Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies Corporation, Thermo Fisher scientific, USA). The library was built by pooling the same quantity (ng) of each amplicon. The library pool was cleaned up with sparQ PureMag Beads (Quantabio, USA) and quantified using Kapa Illumina GA with Revised Primers-SYBR Fast Universal kit (Kapa Biosystems, UK). The average fragment size was determined using a LabChip GX (PerkinElmer, Inc) instrument. Before sequencing, 12% of PhiX control library was added to the amplicon pools (loaded at a final concentration of 9 pM). Sequencing was carried out with the MiSeq Reagent kit v3 600 cycles from Ilumina (300 bp paired-end) (Génome Québec Center, Montreal, Quebec).

Bioinformatics and data integration analysis

The quality of the reads was determined using the FASTQC quality control tool version 0.10.0 (Babraham Bioinformatics 2022) for both 16S rRNA, ITS and AMF amplicon sequences. Subsequently, forward and reverse reads were then truncated using Cutadapt96. The DADA2 v1.16.0 pipeline97 was used to denoise and obtain amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) from demultiplexed reads for all samples. Reads that did not overlap were removed from the rest of the analysis. Taxonomic assignment was performed using the naïve Bayesian classifier (implemented in DADA2) using the ‘Silva version 138’ database for Archaea/bacteria (Quast et al. 2013) and the UNITE v8.2 database for fungi98 and MARJAAM for AMF99. The ASV table was filtered at taxonomic genus level and used for further analysis. A threshold of 10 occurrences using the function decostand from Vegan package100 was applied to merge low-occurring microbes that could not be properly modeled in a column named ‘Others’. The microbiome analyses were conducted in R v.4.2.090 using R packages: tidyr, dplyr, ggplot2).

Gjam package v2.3.2101 was used to estimate the effects of inoculum in different models for the different treatments (Bacterial isolates x AMFc). From each model, the regression coefficients were extracted from each treatment to identify shifts in the microbial community, plant biomass, and root architecture. Model diagnosis evaluated the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to check when the estimated coefficients reached a stable value (after 15,000 interactions with a burn-in of 6000 interactions).

Since the current experiment consists of a two-way factorial design, regression coefficients were analyzed against the null hypothesis of no difference between the treatment and the control for both factors (no AMF inoculation and no PGPB inoculation). This allowed us to determine the effects of sole inoculation with AMFc, single PGPB strain, and the co-inoculation AMFc with single PGPB.

The significance of the regression coefficients was considered when the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero. The regression coefficients from GJAM represent the impact of the different treatments in shaping the microbiome as in Rotoni et al.51. From the GJAM model, we depicted the positive coefficients representing microbial groups and detected to be significantly different and selected in the rhizosphere of each treatment, and the negative coefficients representing the microbial groups detected to be significantly different and not selected in the rhizosphere of each treatment. To represent the shifts of community abundance within each treatment we used centered log-ratio (CLR) values102. For visualizing the variance between the set of regression coefficients (microbiome profiles), we used heatmaps and principal component analysis (PCA), which also allowed us to explore communities’ similarities between treatments. To represent the main effects of each factor with the significant interactions between AMF and PGPB we used a bubble plot. We assessed the potential bacterial functions and fungal guilds to observe community shifts across treatments, utilizing FAPROTAX103,104 for bacterial functions and FunGuild105 for fungal guilds.

Data availability

The raw sequences from amplicon sequencing of 16S rRNA, ITS region, and AMF were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA; https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under the accession number PRJEB77104.

References

Bonfante, P. & Anca, I.-A. Plants, mycorrhizal fungi, and bacteria: a network of interactions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 363–383 (2009).

Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Quaiser, A., Duhamel, M., Van, A. L. & Dufresne, A. The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. New Phytol. 206, 1196–1206 (2015).

Simon, J.-C., Marchesi, J. R., Mougel, C. & Selosse, M.-A. Host-microbiota interactions: from holobiont theory to analysis. Microbiome 7, 5 (2019).

Compant, S., Samad, A., Faist, H. & Sessitsch, A. A review on the plant microbiome: ecology, functions, and emerging trends in microbial application. J. Adv. Res. 19, 29–37 (2019).

Rotoni, C. et al. Cultivar governs plant response to inoculation with single isolates and the microbiome associated with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Appl. Soil Ecol. 197, 105347 (2024).

Alegria Terrazas, R. et al. Defining composition and function of the rhizosphere microbiota of barley genotypes exposed to growth-limiting Nitrogen supplies. mSystems 7, e00934–22 (2022).

Camargo, A. P. et al. Plant microbiomes harbor potential to promote nutrient turnover in impoverished substrates of a Brazilian biodiversity hotspot. ISME J. 17, 354–370 (2023).

Cipriano, M. A. P. et al. Lettuce and rhizosphere microbiome responses to growth promoting Pseudomonas species under field conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92, fiw197 (2016).

Leite, M. F. A. et al. Rearranging the sugarcane holobiont via plant growth-promoting bacteria and nitrogen input. Sci. Total Environ. 800, 149493 (2021).

Armada, E., Leite, M. F. A., Medina, A., Azcón, R. & Kuramae, E. E. Native bacteria promote plant growth under drought stress condition without impacting the rhizomicrobiome. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, fiy092 (2018).

Santos, M. S., Nogueira, M. A. & Hungria, M. Microbial inoculants: reviewing the past, discussing the present and previewing an outstanding future for the use of beneficial bacteria in agriculture. AMB Express 9, 205 (2019).

Labanca, E. R. G., Andrade, S. A. L., Kuramae, E. E. & Silveira, A. P. D. The modulation of sugarcane growth and nutritional profile under aluminum stress is dependent on beneficial endophytic bacteria and plantlet origin. Appl. Soil Ecol. 156, 103715 (2020).

Moretti, L. G. et al. Beneficial microbial species and metabolites alleviate soybean oxidative damage and increase grain yield during short dry spells. Eur. J. Agron. 127, 126293 (2021).

Lagunas, B. et al. Rhizobial nitrogen fixation efficiency shapes endosphere bacterial communities and Medicago truncatula host growth. Microbiome 11, 146 (2023).

Radhakrishnan, R., Hashem, A. & Abd_Allah, E. F. Bacillus: a biological tool for crop improvement through bio-molecular changes in adverse environments. Front. Physiol. 8, 667 (2017).

Li, Q. et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Pseudomonas sp. CM11 specifically induces lateral roots. New Phytol. 235, 1575–1588 (2022).

Bashan, Y. & de-Bashan, L. E. How the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum promotes plant growth—A Critical Assessment. Adv. Agron. 108, 77–136 (2010).

Bononi, L., Chiaramonte, J. B., Pansa, C. C., Moitinho, M. A. & Melo, I. S. Phosphorus-solubilizing Trichoderma spp. from Amazon soils improve soybean plant growth. Sci. Rep. 10, 2858 (2020).

Toghueo, R. M. K. & Boyom, F. F. Endophytic Penicillium species and their agricultural, biotechnological, and pharmaceutical applications. 3 Biotech 10, 107 (2020).

Sarabia, M. et al. Plant growth promotion traits of rhizosphere yeasts and their response to soil characteristics and crop cycle in maize agroecosystems. Rhizosphere 6, 67–73 (2018).

Smith, S. E. & Read, D. INTRODUCTION. in Mycorrhizal Symbiosis 3rd edn (eds. Smith, S. E. & Read, D.) 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012370526-6.50002-7 (Academic Press, 2008).

Hawkins, H.-J. et al. Mycorrhizal mycelium as a global carbon pool. Curr. Biol. 33, R560–R573 (2023).

Deveau, A. & Labbé, J. Mycorrhiza helper bacteria. in Molecular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118951446.ch24 (John Wiley & Sons, 2016).

Sangwan, S. & Prasanna, R. Mycorrhizae Helper bacteria: unlocking their potential as bioenhancers of plant–arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal associations. Microb. Ecol. 84, 1–10 (2022).

Gryndler, M. Interactions of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi with other soil organisms. in Arbuscular Mycorrhizas: Physiology and Function (eds. Kapulnik, Y. & Douds, D. D.) 239–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-0776-3_11 (Springer Netherlands, 2000).

Barea, J.-M., Azcón, R. & Azcón-Aguilar, C. Mycorrhizosphere interactions to improve plant fitness and soil quality. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 81, 343–351 (2002).

Muthukumar, T., Sumathi, C. S., Rajeshkannan, V. & Bagyaraj, D. J. Mycorrhizosphere revisited: multitrophic interactions. in Re-visiting the Rhizosphere Eco-system for Agricultural Sustainability (eds. Singh, U. B., Rai, J. P. & Sharma, A. K.) 9–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4101-6_2 (Springer Nature, 2022).

Moretti, L. G. et al. Bacterial consortium and microbial metabolites increase grain quality and soybean yield. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-020-00263-5 (2020).

Moretti, L. G. et al. Diverse bacterial consortia: key drivers of rhizosoil fertility modulating microbiome functions, plant physiology, nutrition, and soybean grain yield. Environ. Microbiome 19, 50 (2024).

Arora, N. K., Fatima, T., Mishra, I. & Verma, S. Microbe-based inoculants: role in next Green Revolution. in Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development: Volume 2: Biodiversity, Soil and Waste Management (eds. Shukla, V. & Kumar, N.) 191–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6358-0_9 (Springer, 2020).

Mamun, A. A. et al. Microbial consortia versus single-strain inoculants as drought stress protectants in potato affected by the form of N sSupply. Horticulturae 10, 102 (2024).

Bradáčová, K. et al. Microbial consortia versus single-strain inoculants: an advantage in PGPM-assisted tomato production?. Agronomy 9, 105 (2019).

Hu, J. et al. Introduction of probiotic bacterial consortia promotes plant growth via impacts on the resident rhizosphere microbiome. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 288, 20211396 (2021).

Liu, X., Mei, S. & Salles, J. F. Inoculated microbial consortia perform better than single strains in living soil: A meta-analysis. Appl. Soil Ecol. 190, 105011 (2023).

Duncker, K. E., Holmes, Z. A. & You, L. Engineered microbial consortia: strategies and applications. Microb. Cell Factories 20, 211 (2021).

Park, I., Seo, Y.-S. & Mannaa, M. Recruitment of the rhizo-microbiome army: assembly determinants and engineering of the rhizosphere microbiome as a key to unlocking plant potential. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1163832 (2023).

Tsolakidou, M.-D. et al. Rhizosphere-enriched microbes as a pool to design synthetic communities for reproducible beneficial outputs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 95, fiz138 (2019).

Martignoni, M. M. et al. Co-inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi differing in carbon sink strength induces a synergistic effect in plant growth. J. Theor. Biol. 531, 110859 (2021).

Pellegrino, E., Nuti, M. & Ercoli, L. Multiple arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal consortia enhance yield and fatty acids of medicago sativa: a two-year field study on agronomic traits and tracing of fungal persistence. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 814401 (2022).

Bona, E. et al. AM fungi and PGP pseudomonads increase flowering, fruit production, and vitamin content in strawberry grown at low nitrogen and phosphorus levels. Mycorrhiza 25, 181–193 (2015).

Sharma, S., Compant, S., Ballhausen, M.-B., Ruppel, S. & Franken, P. The interaction between Rhizoglomus irregulare and hyphae attached phosphate solubilizing bacteria increases plant biomass of Solanum lycopersicum. Microbiol. Res. 240, 126556 (2020).

Rossetto, L. et al. Sugarcane pre-sprouted seedlings produced with beneficial bacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Bragantia 80, e2721 (2021).

Begum, N. et al. Co-inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and the plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria improve growth and photosynthesis in tobacco under drought stress by up-regulating antioxidant and mineral nutrition metabolism. Microb. Ecol. 83, 971–988 (2022).

Maia, E. P. V., Garcia, K. G. V., de Souza Oliveira Filho, J., Pinheiro, J. I. & Filho, P. F. M. Co-inoculation of Rhizobium and Arbuscular Mycorrhiza increases Mimosa caesalpiniaefolia growth in soil degraded by Manganese mining. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 234, 289 (2023).

Ravnskov, S. et al. Soil inoculation with the biocontrol agent Clonostachys rosea and the mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices results in mutual inhibition, plant growth promotion and alteration of soil microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 3453–3462 (2006).

Saldajeno, M. G. & Hyakumachi, M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal interactions with rhizobacteria or saprotrophic fungi and its implications to biological control of plant diseases. In Mycorrhizal Fungi: Soil, Agriculture and Environmental Implications. 187–212 (2011).

Zai, X.-M., Fan, J.-J., Hao, Z.-P., Liu, X.-M. & Zhang, W.-X. Effect of co-inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate solubilizing fungi on nutrient uptake and photosynthesis of beach palm under salt stress environment. Sci. Rep. 11, 5761 (2021).

Kokko, E. G., Volkmar, K. M., Gowen, B. E. & Entz, T. Determination of total root surface area in soil core samples by image analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 26, 33–43 (1993).

Wu, Q., Pagès, L. & Wu, J. Relationships between root diameter, root length and root branching along lateral roots in adult, field-grown maize. Ann. Bot. 117, 379–390 (2016).

GAO, X. et al. Individual and combined effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phytohormones on the growth and physiobiochemical characteristics of tea cutting seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1140267 (2023).

Rotoni, C., Leite, M. F. A., Pijl, A. & Kuramae, E. E. Rhizosphere microbiome response to host genetic variability: a trade-off between bacterial and fungal community assembly. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 98, fiac061 (2022).

Kaur, S. et al. Synthetic community improves crop performance and alters rhizosphere microbial communities. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 1, 118–131 (2022).

Hoeksema, J. D. et al. A meta-analysis of context-dependency in plant response to inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi. Ecol. Lett. 13, 394–407 (2010).

Pérez-de-Luque, A. et al. The interactive effects of arbuscular mycorrhiza and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria synergistically enhance host plant defences against pathogens. Sci. Rep. 7, 16409 (2017).

Zhang, C. et al. A tripartite bacterial-fungal-plant symbiosis in the mycorrhiza-shaped microbiome drives plant growth and mycorrhization. Microbiome 12, 13 (2024).

Evelin, H., Devi, T. S., Gupta, S. & Kapoor, R. Mitigation of salinity stress in plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: current understanding and new challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 470 (2019).

Zhang, F., Zou, Y.-N., Wu, Q.-S. & Kuča, K. Arbuscular mycorrhizas modulate root polyamine metabolism to enhance drought tolerance of trifoliate orange. Environ. Exp. Bot. 171, 103926 (2020).

Navazio, L. et al. A diffusible signal from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi elicits a transient cytosolic calcium elevation in host plant cells. Plant Physiol 144, 673–681 (2007).

Kosuta, S. et al. Differential and chaotic calcium signatures in the symbiosis signaling pathway of legumes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9823–9828 (2008).

Gutjahr, C. et al. Presymbiotic factors released by the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Gigaspora margarita induce starch accumulation in Lotus japonicus roots. New Phytol. 183, 53–61 (2009).

Dhanker, R., Chaudhary, S., Kumari, A., Kumar, R. & Goyal, S. Symbiotic signaling: insights from arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. in Plant Microbe Symbiosis (eds. Varma, A., Tripathi, S. & Prasad, R.) 75–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36248-5_5 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Paszkowski, U. A journey through signaling in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses 2006. New Phytol. 172, 35–46 (2006).

Oláh, B., Brière, C., Bécard, G., Dénarié, J. & Gough, C. Nod factors and a diffusible factor from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi stimulate lateral root formation in Medicago truncatula via the DMI1/DMI2 signalling pathway. Plant J. 44, 195–207 (2005).

Chiu, C. H., Roszak, P., Orvošová, M. & Paszkowski, U. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induce lateral root development in angiosperms via a conserved set of MAMP receptors. Curr. Biol. 32, 4428–4437.e3 (2022).

Agnolucci, M. et al. Bacteria associated with a commercial mycorrhizal inoculum: community composition and multifunctional activity as assessed by Illumina sequencing and culture-dependent tools. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1956 (2019).

Vacheron, J. et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 356 (2013).

Bourles, A. et al. Co-inoculation with a bacterium and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improves root colonization, plant mineral nutrition, and plant growth of a Cyperaceae plant in an ultramafic soil. Mycorrhiza 30, 121–131 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Biodiversity of the beneficial soil-borne fungi steered by Trichoderma-amended biofertilizers stimulates plant production. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 1–9 (2023).

Odelade, K. A. & Babalola, O. O. Bacteria, fungi and archaea domains in rhizospheric soil and their effects in enhancing agricultural productivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 16, 3873 (2019).

Yadav, R., Ror, P., Beniwal, R., Kumar, S. & Ramakrishna, W. Bacillus sp. and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi consortia enhance wheat nutrient and yield in the second-year field trial: superior performance in comparison with chemical fertilizers. J. Appl. Microbiol. 132, 2203–2219 (2022).

Roesti, D. et al. Bacteria associated with spores of the Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Glomus geosporum and Glomus constrictum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 6673–6679 (2005).

Toljander, J. F., Lindahl, B. D., Paul, L. R., Elfstrand, M. & Finlay, R. D. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal mycelial exudates on soil bacterial growth and community structure. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 61, 295–304 (2007).

Bournaud, C. et al. Interdependency of efficient nodulation and arbuscular mycorrhization in Piptadenia gonoacantha, a Brazilian legume tree. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 2008–2020 (2018).

Halifu, S., Deng, X., Song, X. & Song, R. Effects of two Trichoderma strains on plant growth, rhizosphere soil nutrients, and fungal community of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica annual Seedlings. Forests 10, 758 (2019).

Pang, F. et al. Soil phosphorus transformation and plant uptake driven by phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1383813 (2024).

Lecomte, J., St-Arnaud, M. & Hijri, M. Isolation and identification of soil bacteria growing at the expense of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 317, 43–51 (2011).

Poveda, J. & Eugui, D. Combined use of Trichoderma and beneficial bacteria (mainly Bacillus and Pseudomonas): development of microbial synergistic bio-inoculants in sustainable agriculture. Biol. Control 176, 105100 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Rice domestication influences the composition and function of the rhizosphere bacterial chemotaxis systems. Plant Soil https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-021-05036-2 (2021).

Pacovsky, R. S., Fuller, G. & Paul, E. A. Influence of soil on the interactions between endomycorrhizae and Azospirillum in sorghum. Soil Biol. Biochem. 17, 525–531 (1985).

Larimer, A. L., Bever, J. D. & Clay, K. The interactive effects of plant microbial symbionts: a review and meta-analysis. Symbiosis 51, 139–148 (2010).

Van Der Heijden, M. G. A. et al. The mycorrhizal contribution to plant productivity, plant nutrition and soil structure in experimental grassland. New Phytol. 172, 739–752 (2006).

Castillo, B. T. et al. Fungal community succession of populus grandidentata (Bigtooth Aspen) during Wood Decomposition. Forests 14, 2086 (2023).

Bianciotto, V. & Bonfante, P. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: a specialised niche for rhizospheric and endocellular bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 81, 365–371 (2002).

Lastovetsky, O. A. et al. Spores of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi host surprisingly diverse communities of endobacteria. New Phytol. 242, 1785–1797 (2024).

Marrassini, V., Ercoli, L., Kuramae, E. E., Kowalchuk, G. A. & Pellegrino, E. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi originated from soils with a fertility gradient highlight a strong intraspecies functional variability. Appl. Soil Ecol. 197, 105344 (2024).

Arsenault, J.-L., Poulcur, S., Messier, C. & Guay, R. WinRHlZOTM, a root-measuring system with a unique overlap correction method. HortScience 30, 906D–906D (1995).

Freschet, G. T. et al. Root traits as drivers of plant and ecosystem functioning: current understanding, pitfalls and future research needs. New Phytol. 232, 1123–1158 (2021).

Vierheilig, H., Coughlan, A. P., Wyss, U. & Piché, Y. Ink and vinegar, a simple staining technique for arbuscular-mycorrhizal fungi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 5004–5007 (1998).

Ferreira, E. B., Cavalcanti, P. P. & Nogueira, D. A. ExpDes: An R Package for ANOVA and Experimental Designs. Appl. Math. 5, 2952–2958 (2014).

Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna Austria (2019).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer, New York, NY, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-98141-3.

Simon, L., Lalonde, M. & Bruns, T. D. Specific amplification of 18S fungal ribosomal genes from vesicular-arbuscular endomycorrhizal fungi colonizing roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 291–295 (1992).

Helgason, T., Daniell, T. J., Husband, R., Fitter, A. H. & Young, J. P. W. Ploughing up the wood-wide web?. Nature 394, 431–431 (1998).

Lumini, E., Orgiazzi, A., Borriello, R., Bonfante, P. & Bianciotto, V. Disclosing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal biodiversity in soil through a land-use gradient using a pyrosequencing approach. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 2165–2179 (2010).

Higo, M., Tatewaki, Y., Gunji, K., Kaseda, A. & Isobe, K. Cover cropping can be a stronger determinant than host crop identity for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities colonizing maize and soybean. PeerJ 7, e6403 (2019).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Nilsson, R. H. et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D259–D264 (2019).

Öpik, M. et al. The online database MaarjAM reveals global and ecosystemic distribution patterns in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota). New Phytol. 188, 223–241 (2010).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. (2018).

Clark, J. S., Nemergut, D., Seyednasrollah, B., Turner, P. J. & Zhang, S. Generalized joint attribute modeling for biodiversity analysis: Median-zero, multivariate, multifarious data. Ecol. Monogr. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1241 (2017).

Gloor, G. B. & Reid, G. Compositional analysis: a valid approach to analyze microbiome high-throughput sequencing data. Can. J. Microbiol. 62, 692–703 (2016).

Louca, S., Parfrey, L. W. & Doebeli, M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science 353, 1272–1277 (2016).

Sansupa, C. et al. Can we use Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxa (FAPROTAX) to assign the ecological functions of soil bacteria?. Appl. Sci. 11, 688 (2021).

Nguyen, N. H. et al. FUNGuild: aAn open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 20, 241–248 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Gregor Disveld for the greenhouse advice, Elena Gallina for the help in harvesting and measuring root traits. We thank Koppert Biological Systems BV for project support and Royal van Zanten BV for providing the chrysanthemum cuttings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R., M.F.A.L. and E.E.K. conceived and designed the research project. C.R. and M.F.A.L. performed the bioinformatics and statistical analyses. C.R., M.F.A.L. and A.P. contributed and conducted all the experiments. C.R., M.F.A.L., G.A.K. and E.E.K. contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rotoni, C., Leite, M.F.A., Pijl, A. et al. Synergy between AMF and accompanying microbiome enriched with PGPB enhances root development and microbiome dynamics. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 37 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00081-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00081-1

This article is cited by

-

Potential of indigenous AMF from organic cassava fields in Thailand for sustainable cassava cultivation

International Microbiology (2025)