Abstract

Poor farming and human nutrition cost lives and $10 trillion/yr. Broccoli is rich in phytochemicals implicated in reduced morbidity, but maladapted to the tropics and subtropics, where human illness is severe. Here we review advances in biology and breeding to propose a blueprint for a global broccoli breeding program— designed to improve adaptation to high heat environments, harness its current health benefits, and reduce impacts of long carbon-intensive supply chains.

Similar content being viewed by others

A strategy to manage the global nutrition and health crisis

The global food and healthcare systems face unprecedented challenges that demand innovative solutions. The crisis is multidimensional, and many tactics will be needed to manage it, including increasing the availability, access, and adoption/consumption of healthy foods. The societal, environmental, and medical costs associated with current agricultural systems and poor dietary and health habits amount to $10 trillion annually1. Central to this crisis is the “Triple Burden” of malnutrition: undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, and overweight/obesity, which affect both developed and developing nations1. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) guidelines, a minimum intake of 400 g of fruits and vegetables per day is necessary for optimal health2. However, dietary patterns worldwide often fall short of this target, with global vegetable intake estimated at just 186 g per day3,4,5,6,7. This issue is evident even in countries with abundant food supplies. For instance, in the United States, the paradox of food abundance alongside widespread nutritional deficiencies is striking—fewer than 10% of Americans meet the USDA’s recommended daily vegetable intake of 3 cups8. Meanwhile, rapid population growth and urbanization continue to amplify the demand for sustainable and reliable food sources, straining production and distribution chains.

Addressing these challenges requires systems approaches that encourage dietary shifts toward nutrient-dense foods and leverage agricultural innovations to bolster sustainability. Cruciferous vegetables are nutrient-dense crops9. Broccoli is a nutritional powerhouse, rich in essential vitamins such as A, C, K1, and folate, along with iron, zinc, and other minerals9. Folate is particularly important during pregnancy for fetal development10. Beyond its vitamin and mineral content, broccoli contains an array of bioactive compounds with significant health benefits. Its flavonoids have potent antioxidant11,12 and anti-inflammatory properties13,14, helping to lower the risk of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular conditions and certain cancers15,16,17. Additionally, broccoli is abundant in glucosinolates18—plant compounds that break down into bioactive isothiocyanates, known for their antioxidant and anti-cancer effects19,20. Variants like purple broccoli contribute further benefits due to their high levels of anthocyanins21, which provide additional anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and anti-cancer properties22. While pungent flavors may hamper consumption, we foresee broccoli as an important dietary component to reduce nutrient deficiencies and chronic disease.

In contrast to root and cereal breeding supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR)23, a center for global crop improvement and strategy for fruits and vegetables —broccoli in particular—remains lacking. Here, we review available tools, recent advances, and future directions to build a global broccoli breeding program aimed at increasing the sustainable production of this nutrient-rich crop. This review is structured around three core objectives:

-

I.

Define the target population of environments for breeding and priority human communities.

-

II.

Design a globally relevant breeding program that expands broccoli’s area of adaptation, enabling more communities to benefit from its health-promoting properties, while also outlining research needs to accelerate genetic gain for nutrient density.

-

III.

Define a framework to translate increased availability via improved cultivars into equitable access and widespread adoption.

Vulnerable and carbon-intensive supply chains

Current horticultural production presents critical economic, environmental, and logistical challenges. Much of the world’s vegetable supply relies heavily on production in India, China, Mexico, and the United States, creating risks to global food security24. Centralization in productive areas increases resource use efficiencies25,26 from the transformation of nutrients to economic resources via the vertical integration of production, processing, and distribution. However, centralization raises concerns about resilience and environmental sustainability27, and food safety standards28. Concentrated production, and thus fertilizer and pesticide use, makes it difficult to manage externalities and disease outbreaks29. The economic and nutritional dependence of tropical and subtropical communities on vegetable production in temperate countries is also a cause for concern30. Similarly, in the United States, California’s climate and resources have supported large-scale vegetable cultivation. Production scale supported a very efficient industry. However, this centralization has resulted in a brittle system31. Factors such as water scarcity32, rising temperatures33, increased number of fire events, and energy costs34 make California’s agricultural output highly vulnerable, raising questions about its resilience in the medium to long term.

Transporting fresh produce thousands of miles—from temperate regions to the tropics and subtropics, and from western to eastern states in the U.S. and beyond—results in significant and inefficient energy use34, greenhouse gas emissions, logistical complexity, and the emergence of nutritional deserts35. At the global scale nutritional deserts refer to all geographies where the ratio between the gross domestic product per capita and the distance to main production of area of broccoli is less than 4.65 (Fig. 1). This is a data driven threshold that effectively describes trade patterns and the concentration of trade in North America, and the European Union and Asia affluent countries (Fig. 2). Deserts are most evident in South America and Africa (Fig. 2), where broccoli is not widely produced, despite these being regions where increased consumption of fruits, vegetables, and broccoli could have the greatest nutritional impact. The perishability of vegetables further exacerbates food waste36,37, reflecting broader global trends. In addition, long supply chains degrade the nutritional value of vegetables38, as prolonged storage and transportation reduce their quality39. These challenges underscore the urgent need to implement more distributed agricultural models that can enhance sustainability, reduce carbon emissions, and ensure a stable, regionally distributed, and more equitable vegetable supply. One viable solution is highlighted by a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) study of UK broccoli production, which demonstrates its remarkably low environmental impact due to efficient land and water use40.

Values are summarized as regional means with standard errors. The red dashed line indicates a threshold, calculated as the maximum mean index among Africa, Asia, Oceania, and Latin America & the Caribbean—regions considered most vulnerable to nutritional insecurity. North America was excluded from the analysis due to a small sample size (n = 2). Asia–High Income includes Japan, South Korea, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, United Arab Emirates, and Israel, classified as high-income economies by the World Bank. EU denotes for the European Union. Data were accessed through the World Bank (supplementary data Table 1). The threshold 4.65 is the mean index for Latin America and the Caribbean, plus 3.09 standard errors for the mean.

a Countries producing ≥100,000 tons annually and exporting ≥1000 tons are highlighted. Arrows represent major export routes, with direction indicating trade flow. The bar chart on the right displays standardized total production across all reporting countries. b Chord diagrams illustrate the direction and volume of trade. The left panel shows exports, and the right panel shows imports. Arrows point toward the destination country, and their thickness corresponds to the quantity traded. Countries are labeled by numeric ID, with names listed below each diagram. Data sourced from FAO106.

Tropical and subtropical socioeconomics

The greatest population growth and urban development are expected to occur in the tropics and subtropics, where the world’s most vulnerable populations reside41 and mortality rates are highest (Table 1). Developing distributed food production systems—particularly for vegetables like broccoli—in these regions could significantly benefit local communities by creating jobs and reducing mortality and morbidity. Regional and peri-urban food systems stimulate economies by generating employment in farming, distribution, marketing, and sales, while also providing consumers with fresher, more nutritious, and often more-affordable produce42. A clear example of this impact can be seen in the U.S. State of Florida, where nearly 32 jobs are created for every $1 million in revenue generated by produce farms engaged in direct marketing, compared to only 10.5 jobs for farms focused on wholesale distribution43.

At the same time, the global broccoli market is experiencing strong growth, driven in part by increasing consumer preference for healthier diets. Valued at $5.5 billion in 2023, the market is projected to reach $9.5 billion by 2030, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.2%44. This expanding demand presents an opportunity for regions around the world to invest in local production, strengthen food security, and eliminate nutritional deserts (Fig. 2). Additionally, consumer education and targeted investments can further increase the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, driving both health and economic benefits.

The case for a broccoli breeding program

Plant breeding has been a primary driver of yield improvements across crops and regions globally. While periodic yield plateaus have occurred, the ability to breed for both qualitative and quantitative traits remains firmly supported by the well-established principles of genetic variation and selection. The Green Revolution is a prime example of the transformative power of plant breeding23. By enabling agronomic intensification, plant breeding successfully prevented widespread food insecurity by increasing caloric availability across environments. However, this success came with unintended consequences, including declines in the nutritional quality of staple crops45 and reduced resilience46. For example, breeding for higher-yielding wheat varieties and maize hybrids has led to reductions in protein content47,48, and increasing fruit size in tomatoes and strawberries has been associated with declines in vitamin C, anthocyanins, and antioxidants49,50. Today, a new revolution is required—one that not only enhances the productivity, resilience, and adaptability of crops but also improves their nutritional value to address global health challenges.

Broccoli represents an ideal model crop for developing blueprints to accelerate genetic gain in nutritional content, resilience, and societal value—including applications in education—for fruit, vegetable, and row crop breeding. In addition to its naturally high and genetic variation for phytochemicals associated with human health, broccoli breeding is well-suited to a range of advanced technologies. These include molecular markers51,52, dynamic modeling53,54, doubled haploids55,56, high-throughput imaging for nutritional and morphological traits57, callus-stage selection, gene editing, breeding with gene editing approaches, and male sterility systems for hybrid development. Broccoli's relatedness to Arabidopsis thaliana offers an exceptional opportunity to leverage a well-established knowledge base to improve germplasm with existing levels of heat tolerance58, enabling the development of varieties suited to nutritional deserts, particularly in tropical and subtropical climates (Fig. 2).

Emerging technologies for crop improvement

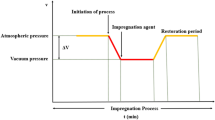

An effective breeding program leverages emerging technologies to adequately sample the target reference of genotypes carrying desirable founder haplotypes and evaluate them within a representative sample of the target population of environments. Figure 3 outlines a conceptual pipeline for AI-enabled broccoli breeding that integrates predictive modeling, genomics, biotechnology, and high-throughput phenotyping. The pipeline begins with efficient experimental designs—such as sparse testing59 —and managed environments designed to uncover genetic variation for traits of interest60. These experiments generate the data needed to train Artificial Intelligence (AI) models, enabling genotype (G) selection decisions based on predicted performance across the diverse environmental and management (M) conditions that characterize the target population of environments, including G × M interactions60. Among the many forms AI can take, the models that have proven effective at accelerating genetic gain60 fall within the domains of statistical learning, optimization, and dynamical systems modeling61. On-farm data further enhance model training by expanding the G × M sample space. Prediction becomes central to selecting parent crosses60, thereby expanding exploration of the G space. The efficiency of the breeding program depends on accurate AI models, streamlined processes for seed or propagule production, rapid development of uniform materials such as doubled haploids for genetic evaluation, the use of high-quality phenomics data, and predictive tools capable of discarding inferior genotypes—ideally at early stages such as callus development. In addition, transgenic, gene editing, and synthetic biology technologies expand the accessible genetic space by introducing novel variation beyond what exists in the germplasm of interest60,62.

The incorporation of high-throughput phenotypic, environmental, and genomic data has significantly improved trait selection and crop performance modeling63. Predictive breeding lies at the core of breeding program efficiency and effectiveness (Fig. 3). Using the breeder’s equation60, it can be shown that the rate of genetic gain is directly proportional to the increase in prediction accuracy (ra) between phenotypic measurements in experimental trials and the underlying true breeding values. The most advanced approaches improve ra by leveraging ensembles of models to capture complex genetic networks influencing trait expression61,64, incorporate environmental covariates65, and fuse dynamic systems models with Bayesian algorithms to model the interdependent relationships among G, E, M, and temporal physiological processes60,66. These dynamic models are grounded in principles of resource capture, use, and allocation, helping prevent overfitting and “model hallucinations” while improving prediction rigor.

A crop model is a selection index because it integrates genomic and environmental predictors to estimate breeding values for multiple traits across the target population of environments67,68. It improves ra by identifying key traits that contribute the most to genetic gain for the target environmental conditions. It simulates adaptation considering time to flowering, leaf area development, photosynthesis, and other interconnected traits. These dependencies implicitly define trait weights that influence the outcomes—such as yield and nutritional quality—on which breeders base selection decisions. Trait dependencies could be represented in a matrix form, illustrating the multivariate nature of this selection index61. Using a crop model as a selection index enables a dynamic approach in which trait weights vary over time and cycles of selection. In the case of broccoli, a crop model will likely weigh time to flowering first to expand the area of adaptation (see role of FLC on heat tolerance below), second, photosynthesis and leaf area development to increase productivity and energy available to produce energy-dense phytochemicals, and finally, production of secondary metabolites to increase nutrient concentrations.

Recent advances in large language models have further accelerated genome and protein sequence predictions69. Deep learning approaches, such as AlphaFold, have dramatically improved protein structure modeling and facilitated the rational design of sequences and proteins for synthetic biology and biotechnology applications70. Modern gene-editing tools now allow for simultaneous and highly precise modification of multiple genes71,72. These systems support non-integrative genome modifications using RNA virus-based vectors for delivery into plant tissues, resulting in heritable modifications and virus-free mutated progeny73,74,75,76. Gene editing offers breeders precise, targeted methods to enhance traits such as disease resistance, environmental adaptability, nutritional content, and production of hybrids. Successful interventions have improved glucosinolate production via MYB transcription factors77,78, boosted flavonoid biosynthesis79, and optimized pathways for vitamin C80, omega-3 fatty acids81,82, and anthocyanin accumulation83. Targeted editing of ORF138 has been shown to restore cytoplasmic male sterility84, enabling hybrid seed production. The ability to simultaneously edit multiple loci opens new avenues for developing resilient, broadly adapted, and nutritionally enhanced broccoli varieties71. The relationship between Arabidopsis thaliana and broccoli allows researchers to harness extensive genomic annotations and functional knowledge, improving the efficiency of gene editing and metabolic engineering in broccoli compared to more distantly related species. In breeding programs, doubled haploid lines provide genetic uniformity and are used as cultivars or parental lines for F1 hybrid development. In broccoli, these can be produced through anther or microspore culture85,86, enabling selection at the callus stage. Together with other advanced breeding tools, breeders can develop hybrids or self-pollinated lines that combine robust environmental adaptability with desirable consumer traits such as flavor, texture, and market appeal87.

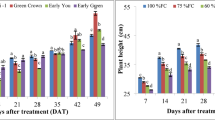

Brassica oleracea is understudied in tropical and subtropical environments

Breeding technologies capable of doubling the rate of genetic gain—as demonstrated in drought-tolerant maize programs60,66—depend on a deep biological understanding of crop improvement. Although dynamic models have been proposed for broccoli53, the crop remains significantly underrepresented in research targeting adaptation to tropical and subtropical environments (Fig. 4). A systematic review conducted using the PRISMA flowchart methodology identified 1581 articles, of which only 48 addressed key topics such as heat tolerance, tropical and subtropical adaptation, physiology, modeling, or genetics (Supplementary Table 2). These studies consistently highlight temperature as a critical factor influencing broccoli development, yield, and head quality, with both heat and cold extremes impairing growth88,89,90,91,92. The striking overlap between regions characterized by nutritional deserts and long supply chains (Fig. 2) and the lack of research studies in these same areas (Fig. 4) underscores a fundamental knowledge gap that must be urgently addressed.

The map shows that most studies are concentrated in temperate regions, with limited research conducted in tropical and subtropical climates. Search terms included: “Brassica oleracea var. italica,” “broccoli,” “temperature,” “photoperiod,” “nitrogen,” “heat,” “crop growth model,” “photosynthesis,” “leaf appearance rate,” “leaf area,” “inflorescence,” and “quantitative trait loci (QTL)”.

Optimal head initiation and yield in broccoli occur between 16–18 °C, while temperatures exceeding 30 °C arrest inflorescence development, resulting in uneven or absent heads89,90,93. In contrast, cooler temperatures around 12 °C delay vegetative growth and induce earlier bud formation at a younger morphological stage94. Temperature-dependent linear models have been developed for head initiation and growth in the 0–17 °C range95. However, under subtropical conditions, broccoli may flower more rapidly when exposed to longer photoperiods and higher temperatures96. Although genomic research on broccoli flowering under tropical and subtropical conditions remains limited, upregulation of BoFLC1 has been consistently observed in heat-sensitive broccoli genotypes, while promoter variation in BoFLC1 has been identified as a potential genetic factor distinguishing heat-tolerant from heat-sensitive broccoli lines97. In cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis), BoFLC1 downregulation has been associated with curd development at temperatures of 26–30 °C98. In cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata), expression of tandemly duplicated BoFLC1 genes (BoFLC1a and BoFLC1b) has been implicated in the inhibition of flowering99. Heat tolerance in broccoli is polygenic, offering valuable insights for breeding resilient varieties able to thrive under high-temperature conditions (20–30 °C)100. Five major QTL associated with heat tolerance were identified in a doubled haploid mapping population evaluated under summer field conditions52. Two additional QTL, with heat tolerance significantly correlated with early flowering time51. These findings highlight the potential for marker-assisted selection to accelerate the development of heat-tolerant broccoli adapted to tropical and subtropical regions. While existing studies are constrained by limited genotype and environment testing, they collectively suggest that flowering time regulators and integrators of signal, such as FLC101, play a central role in adaptation to the tropics and subtropics, with emerging evidence of trade-offs between early maturity and stress resilience that merit further exploration. Realizing the full potential of heat-resilient broccoli will require sustained investment and research across diverse germplasm evaluated under a broad range of environmental conditions. To achieve meaningful progress, a robust breeding framework is needed—one that draws from both established literature and emerging technologies.

Expanding availability, access, and adoption of heat-tolerant broccoli

To address the global nutritional crisis and generate broader societal value, breeding objectives must be reimagined to incorporate considerations of availability, access, and adoption. Availability must go beyond simply closing the yield gap in major producing regions (Fig. 2) to include nutritional quality, such as enhanced nutrient content. Access refers to the development of cultivars suited to a wide range of target environments—including the nutritional deserts of the world (Fig. 2, Table 1)—and the capacity for farmers to locally produce seeds or propagules. Adoption must consider the organoleptic and culinary properties of varieties to overcome cultural and socioeconomic barriers. G x M strategies can enhance resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses, thereby improving both the availability and accessibility of nutritious crops.

While global nutritional deserts are predominantly located in tropical and subtropical regions, this broad target population of environments represents a complex mix of abiotic and biotic conditions. These environments may require the development of cultivars with specific adaptations to ensure stable nutrient availability. Distributed breeding systems that facilitate the exchange of germplasm have proven to be among the most effective strategies for addressing the complexity of such a target population of environments102. Collaborative efforts among international institutions, local agricultural colleges, and regional research centers are essential for establishing breeding programs, sharing germplasm, and equipping breeders with the tools and knowledge needed to develop regionally adapted cultivars. Critically, educational programs aimed at empowering breeders to fully leverage both native and novel sources of variation are currently lacking—and are urgently needed to accelerate genetic gains in nutritional quality across crops.

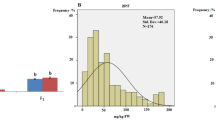

Ensuring access to improved vegetable varieties also requires addressing the affordability and availability of seed. Most broccoli seed used globally originates from hybrid breeding programs, with production concentrated in regions such as California, India, China, and Mexico. In contrast, seed consumption spans a broader range of temperate locations, which further reinforces the lack of adapted germplasm for tropical and subtropical climates (Fig. 5). While hybrid varieties offer advantages in yield and uniformity, their high costs often make them inaccessible to smallholder farmers; thus, alternative seed systems are essential. Self-pollinated and open-pollinated broccoli would allow farmers to save seed. In addition to seed saving, broccoli can be propagated through vegetative cuttings—a practice that, while uncommon, offers a viable alternative for increasing plant availability where access to quality seed is limited. Clonal propagation, currently feasible in broccoli, would allow farmers to rapidly expand their plant stock without relying solely on commercial seed suppliers, facilitating the cultivation of this nutrient-dense crop in areas where affordability and distribution constraints hinder adoption. This approach could be particularly impactful in rural and low-income communities, where increasing access to nutritious vegetables like broccoli is critical for improving dietary diversity and public health.

This diagram illustrates the major components of hybrid broccoli seed production, including the use of cytoplasmic male sterility and self-incompatibility systems for hybrid development. It highlights key commercial seed companies, the primary regions where hybrid seed is produced, and the broader global markets where seed is consumed. The geographic disconnect between seed production (concentrated in temperate regions) and the underrepresentation of adapted germplasm for tropical and subtropical environments underscores a critical gap in access. This supply chain structure limits the availability and affordability of suitable varieties for stallholder farmers in low-income regions.

Supporting the development and distribution of open-pollinated and self-pollinated varieties would help smallholder farmers achieve greater seed sovereignty and autonomy. It would help reduce dependency on commercial seed suppliers—especially in areas with limited market access and persistent nutritional deserts (Fig. 2)—and contribute to the long-term sustainability of vegetable production systems. However, broccoli cultivars that are truly adapted to tropical and subtropical environments remain largely unavailable. Varieties marketed in these nutritional deserts often rely on vague claims of heat tolerance, lacking clear temperature thresholds, supporting trial data, or specific definitions of the environmental conditions under which heat tolerance was evaluated. In nearly all cases, cultivars are still recommended for winter production in subtropical regions, and none are explicitly promoted for use in true tropical climates (Table 2). This gap is reflected in the low production levels across many tropical and subtropical regions (Fig. 2), despite the urgent need for nutritionally dense crops like broccoli in areas facing the highest rates of nutritional insecurity.

While improving access to heat-adapted cultivars is essential, it is only part of the challenge. Widespread adoption of heat-tolerant crops also depends on overcoming economic, cultural, and behavioral barriers. While technical innovation, policy support, and infrastructure are essential, securing farmer and consumer acceptance is equally critical. Public health campaigns, community-led cooking demonstrations, and school-based nutrition programs can familiarize consumers with the improved flavor and health benefits of these crops. By integrating education, policy, and targeted breeding efforts, heat-tolerant broccoli can serve as a model for future crop improvement initiatives that address climate resilience, food security, and public health in tandem. Expanding access to improved vegetable varieties requires a coordinated effort across breeding institutions, policymakers, and industry stakeholders to ensure that the benefits of agricultural innovation reach the farmers and communities who need them most. The development of heat-adapted broccoli would represent a scientific breakthrough as well as a broader shift toward sustainable, nutrition-driven breeding programs that strengthen food systems worldwide.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Willett, W. et al. Food in the anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393, 447–492 (2019).

Amine, E. K. et al. Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations (FAO). Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 916 (WHO, 2003).

Micha, R. et al. Global, regional and national consumption of major food groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 5, e008705 (2015).

Vos, T. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390, 1211–1259 (2017).

Miller, V. et al. Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: findings from the prospective urban rural epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet Glob. Health 4, e695–e703 (2016).

Hall, J. N. et al. Global variability in fruit and vegetable consumption. Am. J. Prev. Med. 36, 402–409.e5 (2009).

Kalmpourtzidou, A., Eilander, A. & Talsma, E. F. Global vegetable intake and supply compared to recommendations: a systematic review. Nutrients 12, 1558 (2020).

Lee, S. H. et al. Adults meeting fruit and vegetable intake recommendations - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 71, 1–9 (2022).

Syed, R. U. et al. Broccoli: a multi-faceted vegetable for health: an in-depth review of its nutritional attributes, antimicrobial abilities, and anti-inflammatory properties. Antibiotics 12, 1157 (2023).

Krishnaswamy, K. & Nair, K. M. Importance of folate in human nutrition. Br. J. Nutr. 85, S115–S124 (2001).

Kim, J. S. et al. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of solvent fractions of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L.) sprout. Appl. Biol. Chem. 65, 34 (2022).

Favela-González, K. M., Hernández-Almanza, A. Y. & De la Fuente-Salcido, N. M. The value of bioactive compounds of cruciferous vegetables (Brassica) as antimicrobials and antioxidants: a review. J. Food Biochem. 44, e13414 (2020).

López-Chillón, M. T. et al. Effects of long-term consumption of broccoli sprouts on inflammatory markers in overweight subjects. Clin. Nutr. 38, 745–752 (2019).

Hwang, J.-H. & Lim, S.-B. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of broccoli florets in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 19, 89 (2014).

Borgi, L. et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the Incidence of hypertension in three prospective cohort studies. Hypertension 67, 288–293 (2016).

Li, N. et al. Cruciferous vegetable and isothiocyanate intake and multiple health outcomes. Food Chem. 375, 131816 (2022).

Jabbarzadeh Kaboli, P. et al. Targets and mechanisms of sulforaphane derivatives obtained from cruciferous plants with special focus on breast cancer - contradictory effects and future perspectives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 121, 109635 (2020).

Ishida, M. et al. Glucosinolate metabolism, functionality and breeding for the improvement of Brassicaceae vegetables. Breeding Sci 64, 48–59 (2014).

Liang, H., Lai, B. & Yuan, Q. Sulforaphane induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in cultured human lung adenocarcinoma LTEP-A2 cells and retards growth of LTEP-A2 xenografts in vivo. J. Nat. Prod. 71, 1911–1914 (2008).

Zhang, Y. & Tang, L. Discovery and development of sulforaphane as a cancer chemopreventive phytochemical 1. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 28, 1343–1354 (2007).

Liu, C. et al. Transcriptomic profiling of purple broccoli reveals light-induced anthocyanin biosynthetic signaling and structural genes. PeerJ 8, e8870 (2020).

Pojer, E. et al. The case for anthocyanin consumption to promote human health: a review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 12, 483–508 (2013).

Fuglie, K. O. & Echeverria, R. G. The economic impact of CGIAR-related crop technologies on agricultural productivity in developing countries, 1961–2020. World Dev, 176, 106523 (2024).

Baffes, J. & Mekonnen, D. Risks and challenges in global agricultural markets. Let’s Talk Development. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/developmenttalk/risks-and-challenges-in-global-agricultural-markets. (2025).

de Wit, C. T. Resource use efficiency in agriculture. Agric. Syst. 40, 125–151 (1992).

de Wit, C. T. The efficient use of labour, land and energy in agriculture. Agric. Syst. 4, 279–287 (1979).

Campi, M., Due¤as, M. & Fagiolo, G. Specialization in food production affects global food security and food systems sustainability. World Dev. 41, 105411 (2021).

Sanders, T. A. Food production and food safety. BMJ 318, 1689–1693, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7199.1689 (1999).

Tilman, D. et al. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20260–20264 (2011).

Schmidhuber, J. & Tubiello, F. N. Global food security under climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19703–19708 (2007).

Kerr, A. et al. Vulnerability of California specialty crops to projected mid-century temperature changes. Clim. Chang. 148, 419–436 (2018).

Water scarcity: Impacts on Western Agriculture (eds Engelbert, E. A. & Scheuring, A. F.) 516 (Univ. California Press, 2022).

Pathak, T. B. et al. Climate change trends and impacts on California agriculture: a detailed review. Agronomy 8, 25 (2018).

Treadwell, D. D. et al. Transitioning away from fossil fuels will drive repositioning of horticulture. HortScience 59, 561–564 (2024).

Volpe, R., Roeger, E. & Leibtag, E. How Transportation Costs Affect Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Prices. ERR-160 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, 2013).

Dai, B. et al. Changes in the supply chain outcomes of food regionalization, 2007–2017: Broccoli in the eastern United States. PLoS ONE 18, e0287691 (2023).

Tort, ÖÖ, Vayvay, Ö & Çobanoğlu, E. A systematic review of sustainable fresh fruit and vegetable supply chains. Sustainability 14, 1573 (2022).

Verkerk, R. et al. Glucosinolates in Brassica vegetables: The influence of the food supply chain on intake, bioavailability and human health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 53, S219 (2009).

Khazaeli, S., Kalvandi, R. & Sahebi, H. A multi-level multi-product supply chain network design of vegetables products considering costs of quality: a case study. PLoS ONE 19, e0303054 (2024).

Canals, L. M. et al. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Domestic vs. Imported Vegetables. Case Studies on Broccoli, Salad Crops and Green Beans. RELU Project REW-224-25-0044 (Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey, UK, 2008).

Dodman, D. et al. In Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Pörtner H.-O. et al.) 907–1040 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Moustier, P. & Danso, G. K. in Cities Farming for the Future: Urban Agriculture for Green and Productive Cities (ed. Van Veenhuizen, R.) 1–23. (International Development Research Centre, 2006).

Dumont, A. The economic impact of locally produced food. St. Louis Fed On the Economy https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2017/december/economic-impact-locally-produced-food (USA, 2017).

Verified Market Research. Global fresh broccoli market size by type, by end-user, by certification, by harvest type, by geographic scope and forecast. https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/fresh-broccoli-market/ (2024).

Davis, D. R., Epp, M. D. & Riordan, H. D. Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950 to 1999. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 23, 669–682 (2004).

Xiong, W. et al. Increased ranking change in wheat breeding under climate change. Nat. Plants 7, 1207–1212 (2021).

Zhao, F. J. et al. Variation in mineral micronutrient concentrations in grain of wheat lines of diverse origin. J. Cereal Sci. 49, 290–295 (2009).

Pleijel, H. et al. Grain protein accumulation in relation to grain yield of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grown in open-top chambers with different concentrations of ozone, carbon dioxide and water availability. Agric. Ecosyst. Envir. 72, 265–270 (1999).

Dorais, M., Ehret, D. & Papadopoulos, A. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) health components: from the seed to the consumer. Phytochem. Rev. 7, 231–250 (2008).

Simkova, K. et al. Berry size and weight as factors influencing the chemical composition of strawberry fruit. J. Food Compos. Anal. 123, 105509 (2023).

Branham, S. E. & Farnham, M. W. Identification of heat tolerance loci in broccoli through bulked segregant analysis using whole genome resequencing. Euphytica 215, 1–9 (2019).

Branham, S. E. et al. Quantitative trait loci mapping of heat tolerance in broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) using genotyping-by-sequencing. Theor. Appl. Genet. 130, 529–538 (2017).

Grevsen, K. & Olesen, J. Modelling development of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica) from transplanting to head initiation. J. Hort. Sci. Biotechnol. 74, 698–705 (1999).

Kage, H., Kochler, M. & Stützel, H. Root growth of cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L. botrytis) under unstressed conditions: measurement and modelling. Plant Soil 223, 133–147 (2000).

Alan, A. R. et al. in Doubled Haploid Technology: Volume 2: Hot Topics, Apiaceae, Brassicaceae, Solanaceae (ed. Segui-Simarro J. M.) 201–216 (Springer, 2021).

Farnham, M. W. Doubled-haploid broccoli production using anther culture: effect of anther source and seed set characteristics of derived lines. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 123, 73–77 (1998).

Jiang, Y. & Li, C. Convolutional neural networks for image-based high-throughput plant phenotyping: a review. Plant Phenomics 2020, 4152816 (2020).

Farnham, M. W. & Björkman, T. Evaluation of experimental broccoli hybrids developed for summer production in the eastern United States. HortScience 46, 858–863 (2011).

Persa, R. et al. Improving predictive ability in sparse testing designs in soybean populations. Front. Genet. 14, 1269255 (2023).

Cooper, M. & Messina, C. D. Breeding crops for drought-affected environments and improved climate resilience. Plant Cell 35, 162–186 (2023).

Messina, C. et al. Toward a general framework for AI-enabled prediction in crop improvement. Theor. Appl. Genet. 138, 151 (2025).

Simmons, C. R. et al. Successes and insights of an industry biotech program to enhance maize agronomic traits. Plant Sci 307, 110899 (2021).

Bevan, M. W. et al. Genomic innovation for crop improvement. Nature 543, 346–354 (2017).

Cooper, M., Tomura, S., Wilkinson, M. J., Powell, O. & Messina, C. D. Breeding perspectives on tackling trait genome-to-phenome (G2P) dimensionality using ensemble-based genomic prediction. Theor. Appl. Genet. 138, 172 (2025).

Millet, E. J. et al. Genomic prediction of maize yield across European environmental conditions. Nat Genet 51, 952–956 (2019).

Messina, C. D. et al. Crop improvement for circular bioeconomy systems. J. ASABE 65, 491–504 (2022).

Messina, C. D. et al. Yield–trait performance landscapes: from theory to application in breeding maize for drought tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 855–868 (2011).

Cooper, M. et al. Modelling selection response in plant-breeding programs using crop models as mechanistic gene-to-phenotype (CGM-G2P) multi-trait link functions. In silico Plants, 2020 3, diaa016 (2021).

Nguyen, E. et al. Sequence modeling and design from molecular to genome scale with Evo. Science 386, eado9336 (2024).

Jumper, J. & Hassabis, D. Protein structure predictions to atomic accuracy with AlphaFold. Nat. Methods 19, 11–12 (2022).

Sulis, D. B. et al. Multiplex CRISPR editing of wood for sustainable fiber production. Science 381, 216–221 (2023).

McCarty, N. S. et al. Multiplexed CRISPR technologies for gene editing and transcriptional regulation. Nat. Commun. 11, 1281 (2020).

Ellison, E. E. et al. Multiplexed heritable gene editing using RNA viruses and mobile single guide RNAs. Nat. Plants 6, 620–624 (2020).

Uranga, M. et al. Efficient Cas9 multiplex editing using unspaced sgRNA arrays engineering in a Potato virus X vector. Plant J. 106, 555–565 (2021).

Khakhar, A. & Voytas D. F. RNA viral vectors for accelerating plant synthetic biology. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.668580 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. Exploiting viral vectors to deliver genome editing reagents in plants. aBIOTECH 5, 247–261 (2024).

Kim, Y.-C. et al. Development of glucoraphanin-rich broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated DNA-free BolMYB28 editing. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 16, 123–132 (2022).

Mitreiter, S. & Gigolashvili, T. Regulation of glucosinolate biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 70–91 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. Transcriptional regulation of flavonol biosynthesis in plants. Hort. Resear. 11, uhae043 (2024).

Sami, A. et al. Genetics aspect of vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) biosynthesis and signaling pathways in fruits and vegetables crops. Funct. Integr. Genomics 24, 73 (2024).

Wu, G. et al. Stepwise engineering to produce high yields of very long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in plants. Nat. Biotechnol 23, 1013–1017 (2005).

Ruiz-López, N. et al. Enhancing the accumulation of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana via iterative metabolic engineering and genetic crossing. Transgenic Res. 21, 1233–1243 (2012).

Liu, C. et al. Identification of major loci and candidate genes for anthocyanin biosynthesis in broccoli using QTL-Seq. Horticulturae https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7080246 (2021).

Xu, F. et al. Editing of ORF138 restores fertility of Ogura cytoplasmic male sterile broccoli via mitoTALENs. Plant Biotechnol. J. 22, 1325–1334 (2024).

Duijs, J. et al. Microspore culture is successful in most crop types of Brassica oleracea L. Euphytica 60, 45–55 (1992).

Keller, W. A. & Armstrong, K. C. Production of haploids via anther culture in Brassica oleracea var Italica. Euphytica 32, 151–159 (1983).

Sabadin, F. et al. Optimizing self-pollinated crop breeding employing genomic selection: from schemes to updating training sets. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 935885 (2022).

Heather, D. et al. Heat tolerance and holding ability in broccoli. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 117, 887–892 (1992).

Björkman, T. & Pearson, K. J. High temperature arrest of inflorescence development in broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica L.). J. Exp. Bot. 49, 101–106 (1998).

Kałużewicz, A., Krzesiński, W. & Knaflewski, M. Effect of temperature on the yield and quality of broccoli heads. J. Fruit Ornam. Plant Res. 71, 51–58 (2009).

Wiebe, H. J. The morphological development of cauliflower and broccoli cultivars depending on temperature. Sci. Hortic. 3, 95–101 (1975).

Tan, D. K. Y. et al. Freeze-induced reduction of broccoli yield and quality. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 39, 771–780 (2000).

Kałużewicz, A. et al. Effect of temperature on the growth of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica Plenck) cv. Fiesta. J. Fruit Ornam. Plant Res. 77, 129–141 (2012).

Gauss, J. F. & Taylor, G. A. Environmental factors influencing reproductive differentiation and the subsequent formation of the inflorescence of Brassica olerácea L. var. itálica, Plenck cv.‘Coastal’. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 94, 275–280 (1969).

Grevsen, K. Effects of temperature on head growth of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica): Parameter estimates for a predictive model. J. Hort. Sci. Biotechnol. 73, 235–244 (1998).

Lin, Y. R. et al. Subtropical adaptation of a temperate plant (Brassica oleracea var. italica) utilizes non-vernalization-responsive QTLs. Sci. Rep. 8, 13609 (2018).

Lin, C. W. et al. Analysis of ambient temperature-responsive transcriptome in shoot apical meristem of heat-tolerant and heat-sensitive broccoli inbred lines during floral head formation. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 3 (2019).

Lin, C.-Y. et al. Collaborative expression of FLOWERING LOCUS C in heat-tolerant cauliflower. Fruits 78, 1–7 (2023).

Kinoshita, Y., Motoki, K. & Hosokawa, M. Upregulation of tandem duplicated BoFLC1 genes is associated with the non-flowering trait in Brassica oleracea var. capitata. Theor. Appl. Genet. 136, 41 (2023).

Farnham, M. W. & Bjorkman, T. Breeding vegetables adapted to high temperatures: a case study with broccoli. HortScience 46, 1093–1097 (2011).

Deng, W. et al. FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) regulates development pathways throughout the life cycle of Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6680–6685 (2011).

Technow, F., Podlich, D. & Cooper, M. Back to the future: implications of genetic complexity for the structure of hybrid breeding programs. G3 11, jkab153 (2021).

United Nations, D.o.E.a.S.A., Population Division. World Population Prospects 2024. Online Edition https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/world-population-prospects-2024 (2024).

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Cause-Specific Mortality 1990-2021 https://doi.org/10.6069/4fgf-3t54 (IHME USA, 2024).

Database, G. D., Global Dietary Intake Estimates https://globaldietarydatabase.org/available-gdd-2018-estimates-datafiles (2018).

Trade – Crops and Livestock Products. FAOSTAT Tech. Rep. (FAO, 2024)

Moher, D. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 264–269 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-2236414. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. and C.M. contributed equally to this work. Both authors were involved in conceptualizing the research, analyzing and synthesizing key findings, and drafting the manuscript. M.C. and C.M. reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cabrera, M., Messina, C.D. A case for breeding heat-tolerant broccoli. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 53 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00096-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00096-8