Abstract

Urbanization and population growth are shrinking lowland rice areas, compelling exploration of Asia’s under‑studied highlands for future food security. Using earth observation data from 2000 to 2020 and machine learning method, we analyzed the distribution of paddy (irrigated) rice fields and their driving factors in Asian highlands (>1000 ma.s.l.). Highlands currently host 1.489 ± 0.176 millionha of rice, concentrated in the Tianshan–Tarim Basin, Hetao Plain along the Yellow River, and Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau. Altitude is the dominant constraint; additional precipitation is associated with reduced rice extent in the highlands, whereas population density and economic growth are associated with expansion. Our scenario modelling projects ~60% expansion and northward shift of high‑altitude paddies by 2035, yielding more nutrient‑rich, low‑contaminant grain and aiding saline–alkali reclamation. These findings highlight substantial, climate‑resilient capacity in Asian uplands to bolster sustainable rice supply and regional food security. This integrated assessment fills a critical knowledge gap regarding high‑elevation agroecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is an important crop type and a staple food for over half of the people worldwide, with Asian countries making up ~90% of its global production and trade, highlighting its importance for global food security1. Due to population growth and economic expansion in many Asian countries, the demand for rice is projected to increase by approximately 70% over the next 30 years, which may challenge supply even though rice yields have more than doubled since the pre-Green Revolution era (1940s–1960s)2. At the same time, concerns over the food safety and public health associated with rice cultivation are growing in Asian countries. Recent studies have shown that rapid urbanization and industrialization have led to a rapid land use change and paddy field losses in Asia3. It has been estimated that China will lose 1.2 million hectares of paddy fields in the decade from 2023 to 20324. Additionally, rice cultivation in many Asian lowlands is affected by soil and water contamination, especially from heavy metals and microplastics3,5,6. Climate warming increases the release of toxic substances, such as inorganic arsenic, into soils, leading to its accumulation in rice grains, which reduces productivity and quality and poses risks to human health through the food chain7. While more efficient cultivation methods can help compensate for paddy field losses8, the significant financial investments required pose challenges in many Asian countries with large populations still living in poverty9. As arable lowlands in Asia become increasingly occupied by human activities and suffer from contamination9, we expect paddy rice fields to expand into Asian highland regions.

Asia covers one-third of the global land area, with about half consisting of highlands. These Asian highlands (hills, mountains, and high plateaus) span vast regions of the Hindu Kush Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau, stretching from Pakistan to China9,10. Primarily influenced by a cold and dry continental climate, they receive moisture mainly from the Asian summer monsoon and winter western disturbances11,12. Compared to lowland regions, the climate conditions in the Asian highlands are generally less suitable for paddy rice fields. Nevertheless, abundant solar radiation and cryospheric water resources make rice cultivation viable in many Asian highland areas13. Besides, adopting sustainable cropping systems and cultivating drought- and cold-tolerant rice varieties adapted to highland conditions can partially reduce reliance on warm and wet climates14,15. Moreover, Asian highlands, particularly the Tibetan Plateau and Himalayas, are warming at two to three times the global average rate11,12. This rapid warming is expected to increase glacier meltwater and regional rainfall, creating more favorable conditions for irrigated rice cultivation8,16,17. Studies have demonstrated that paddy rice can be cultivated in Asian highland regions at altitudes exceeding 3000 m above sea level (ma.s.l.), including areas such as Tkhitu, north of the Yangtze Gorge, and Yulong Shan13,15,18. Rice grown in these highlands—typically japonica varieties—is more nutritious and commands higher economic value than lowland rice13,15,18. Therefore, highland rice cultivation presents a promising approach to enhance food security and safety while also stimulating regional economic development.

Until now, the scale, distribution, and future potential of highland rice cultivation have remained largely unknown, and the factors influencing paddy field expansion and strategies for sustainable development remain unexplored. To address these gaps, our study aims to answer the following three questions: (1) How extensive are the historical paddy rice fields in Asian highlands, and how might they evolve up to 2035? (2) What are the key factors influencing the expansion of paddy fields in Asian highland regions, and what are the underlying mechanisms? (3) What is the potential for future paddy rice fields in Asian highlands, and what strategies should be adopted for sustainable agricultural development? We examine the advantages and opportunities of highland rice cultivation, along with the challenges and potential drawbacks of large-scale implementation. To estimate where and how paddy rice fields have changed in Asian highlands from 2000 to 2020, we used the APRA500 dataset19, which maps annual paddy fields in Asian countries using MODIS satellite images at a 500-m resolution (see Methods: ‘Research areas’). Next, to identify the key factors influencing changes in rice planting areas across Asian highlands, we developed Random Forest models taking thirteen socioeconomic and climatic factors as drivers to simulate the gridded distribution of paddy rice fields (see Methods: ‘Random Forest model development’). We then predicted future paddy rice areas in Asian highlands up to 2035, revealing potential expansion trends based on the developed models. We also examine the advantages and opportunities of Asian highland rice cultivation, along with the challenges and potential drawbacks of large-scale implementation. This study offers important insights into the potential for paddy rice fields in Asian highlands, providing guidance for sustainable agricultural development.

Results

Distribution and dynamics of paddy fields in Asian highlands

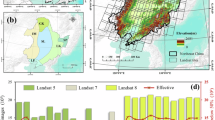

In this study, we mapped paddy rice fields in the Asian highlands at a spatial resolution of 500 m × 500 m using the APRA500 dataset, identifying regions with at least one year of paddy rice fields between 2000 and 2020 (Fig. 1). Our results reveal a scarce distribution of paddy rice fields on the Tibetan Plateau itself, but a relatively higher concentration in the surrounding highland regions. We assessed three rice-producing sub-regions with concentrated paddy rice fields: Tian Shan and Kunlun Mountains (sub-region A, in the northwestern range), Qilian-Yinshan-Taihang Mountains (sub-region B, northeastern range), and Hengduan Mountain (sub-region C, southeastern range). Together these sub-regions account for ~93% of highland paddy area (2000s averages: A 21%, B19%, C53%; 2010s: A28%, B30%, C36%). Over the study period, the annual paddy rice fields in sub-region A varied from a minimum of 245 kilo hectares (kha) in 2000 to a maximum of 525 kha in 2011. Similarly, sub-regions B and C showed annual variations ranging from 217 kha in 2002 to 513 kha in 2011 and from 323 kha in 2019 to 1,116 kha in 2003, respectively. In sub-region A, the proportion of rice cultivated at altitudes of 1000–1500 m above sea level (ma.s.l.) varied annually from 58% to 76% of the total cultivated area between 2000 and 2020. Cultivation at 1500–2000 ma.s.l. accounted for 4% to 10%, and above 2000 ma.s.l. accounted for 16% to 35%. In sub-region B, the proportion of cultivation at 1000–1500 ma.s.l. was even higher, ranging from 92% to 98%, while 1500–2000 ma.s.l. accounted for 2% to 7%, and above 2000 ma.s.l. was less than 1%. Sub-region C showed a more balanced distribution, with 34% to 46% of cultivation at 1000–1500 ma.s.l., 26% to 33% at 1500–2000 ma.s.l., and 24% to 36% above 2000ma.s.l.

Figure 1 outlines the three sub-regions in our study area, while Supplementary Fig. 1 provides enlarged views highlighting the distribution of highland paddy rice fields and the major cities within the regions. Sub-region A, concentrated along the southern edge of the Tianshan Mountains and the Tarim Basin, features major cultivation areas around Kashi, Aksu, and Hotan. Sub-region B includes dense rice cultivation in the Hetao Plain and the floodplains of the Yellow River, such as Bayannur, Yinchuan, and Shizuishan, as well as the Hexi Corridor north of the Qilian Mountains. In sub-region C, fields are primarily located in the southeastern Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, with major rice-growing areas around Kunming, Qujing, and Bijie. From 2000 to 2020, the extent of highland paddy rice increased in Sub-regions A and B but decreased significantly in Sub-region C. Specifically, the area in Sub-region A grew from 342 kha in the first decade of the 21st century to 386 kha in the second decade, and Sub-region B increased from 300 kha to 415 kha over the same periods. However, these increases were not sufficient to offset the substantial reduction in Sub-region C, where the paddy area declined from 845 kha to 499 kha. Consequently, the overall highland paddy rice area across the Asian highlands decreased from an average of 1599 kha in the 2000s to 1392 kha in the following decade. The decrease in Sub-region C may be influenced by factors such as regional climate change, land-use policies, urbanization, and socio-economic pressures like higher population density, leading to competition for land. These factors will be further explored in the Discussion section.

Identification of key factors affecting Asian highland paddy area

To evaluate the dynamics of paddy rice fields in the Asian highlands and identify key influencing factors, we developed 50 Random Forest (RF) models using MatLab’s ‘TreeBagger’ function. Each model incorporated randomly selected combinations of variables, including eight climate variables (temperatures in Kelvin and precipitation in millimeters across four seasons), three geo-environmental variables (mean altitude in ma.s.l., altitude range in ma.s.l., glacier cover rate in percentage), two socio-economic variables (population density in people per square kilometer and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity), and a binary variable indicating whether cultivation occurred in the previous year (planting history, {0,1}). The binary ‘planting history’ feature captures persistence of irrigated paddy systems. We utilized annual data from 3474 grid cells (each 0.5° × 0.5°) spanning from 2000 to 2020, totaling 72,954 groups of data. Rather than splitting the data into separate training and validation sets, we employed bootstrap sampling with replacement to build the models. The calibrated RF models demonstrated strong explanatory power, achieving R2 values between 0.88 and 0.89 and an average Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) of 8.9 kha, indicating satisfactory model performance (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, all simulations yielded Residual Prediction Deviation (RPD) values exceeding 2.90 (Supplementary Fig. 3), confirming the robustness of our approach, since RPD values above 2.0 indicates excellent model performance19. Details of the model development are provided in the Methods section.

We identified key factors influencing changes in Asian highland rice cultivation. We analyzed the importance of 13 environmental and socio-economic variables across 50 Random Forest models based on the permutation analysis (see methods for details). Figure 2a presents the median importance scores for these features, with interquartile ranges shown as error bars. Figure 2b–m displays the distributions of feature values and their associated Accumulated Local Effects (ALE), highlighting the median ALE and uncertainty intervals indicated by the interquartile ranges. Among the 13 environmental and socio-economic features, altitude emerged as the most significant predictor with a median feature importance score of 2.70 and an interquartile range from 2.54 to 2.91. GDP followed closely with a median score of 2.17 and an interquartile range from 2.01 to 2.34. Other features, ranked by decreasing median feature importance scores (with interquartile ranges in brackets), were altitude range (1.81 [1.73–1.89]), population density (1.52 [1.44–1.63]), summer temperature (1.31 [1.24–1.42]), winter precipitation (1.26 [1.15–1.36]), spring precipitation (1.15 [1.02–1.21]), spring temperature (0.96 [0.88–1.00]), autumn precipitation (0.94 [0.81–1.03]), summer precipitation (0.85 [0.79–1.00]), winter temperature (0.77 [0.71–0.83]), autumn temperature (0.70 [0.64–0.80]), and glacier coverage (0.70 [0.62–0.80]). Based on the results of RF models, four out of the 13 environmental and socio-economic features have been identified as negatively impacting paddy rice fields in Asian highlands. The mean altitude negatively affects cultivation (ALE: –6.6 to –0.9), with this impact intensifying as the altitude increases from 1000 to 2000 m above sea level, and then stabilizing at higher altitudes (2000–6000 m). The altitude range also poses a negative effect (ALE: –15.4 to –3.6), with its impact growing between 355 and 2485 meters before stabilizing. Winter precipitation has a negative effect (ALE: –2.2 to –0.5), and this negative impact decreases as precipitation levels rise. Similarly, spring precipitation (ALE: –1.3 to 0) and summer precipitation (ALE: –2.2 to 0) show negative effects, which also diminish with increased precipitation. In contrast, autumn precipitation generally exhibits a positive effect (ALE: –1.7 to 0.6), which shifts from a negative effect to a positive one as precipitation levels above 525 mm. Furthermore, glacier coverage (%) also shows a positive influence (ALE: 0.04 to 0.05), which remains generally consistent across its value range. Positive effects are also seen with winter temperature (ALE: 0 to 3.9), spring temperature (ALE: 0 to 3.9), summer temperature (ALE: 0 to 1.7), autumn temperature (ALE: 0 to 1.5). Population density (ALE: 0 to 38.5) and GDP (ALE: 1.8 to 24.2) both exhibit positive effects, but their distributions are skewed, with decreasing probabilities at higher values. As population density increases from 60 to 300, its positive impact intensifies; however, beyond this range, the positive effect diminishes. Similarly, while GDP initially has a strong positive influence, this effect rapidly weakens as GDP continues to rise. Notably, although ALE provides valuable insights into the effects of individual features, the impact indicated by ALE values should be interpreted within the context of each specific feature. Therefore, these values may not be directly comparable across different features.

a Displays the importance of 13 features, measured by ‘OOBPermutedPredictorDeltaError’ in MATLAB, with error bars representing standard deviations across 50 different model simulations. b–n Show the frequency distributions of each predictor and their Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) values. Solid lines represent medians from 50 model iterations, while shaded areas indicate the interquartile range (IQR) from the median value. Different colors distinguish the features.

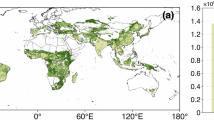

Model prediction of future paddy rice fields in Asian highlands

Using 50 calibrated Random Forest models, we predicted the rice planting area in the Asian highlands from 2021 to 2035, covering the same 3,474 grid cells used in model training. Figure 3 presents our simulation results. Panel (a) shows the projected distribution of rice planting areas in 2035 based on the median of the simulations. Panel (b) compares the planting areas in 2035 with those in 2020 at each grid point. Panel (c) illustrates the annual changes in highland rice planting areas from 2020 to 2035, with different shades of green representing three altitude ranges. Observations from 2000 to 2020 are depicted as gray outlines, while predictions for 2021–2035 are indicated by yellow outlines. The uncertainty of these predictions is represented by the interquartile range (IQR) of the simulations. Our projections indicate that the spatial distribution of paddy rice fields in 2035 will be similar to that observed from 2000 to 2020, although with some regional differences. Paddy fields are expected to remain sparse on the Tibetan Plateau but will be relatively concentrated in surrounding regions such as the Tarim Basin, the Yellow River Loop, and the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. By 2035, most areas in the Asian highlands are projected to experience an increase in rice cultivation compared to 2020, except for some grid points in the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains and the southern part of the Hengduan Mountains regions, where a decrease is projected. Significant increases are anticipated, particularly in the western Tarim Basin, the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, the northern part of the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, and the southern foothills of the Himalayas—including the upper reaches of the Ganges Basin in India and Nepal, and the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra Basin in India and Bangladesh. Overall, the area of paddy rice fields in the Asian highlands is projected to show an increasing trend from 2021 onward. The total cultivation area is expected to increase from 1359 ± 130 kha in 2021–2025 to 1891 ± 65 kha in 2031–2035. At altitudes of 1000 to 1500 ma.s.l., the area is projected to expand from 924 ± 88 to 1260 ± 57 kha. At altitudes of 1500 to 2000 ma.s.l., it is expected to grow from 178 ± 18 to 257 ± 27 kha, and above 2000 ma.s.l., it is projected to increase from 351 ± 18 to 377 ± 15 kha.

a Shows the spatial distribution of rice cultivation areas in Asian highlands; b depicts the projected change in rice cultivation areas between 2020 and 2035; c represents the total highland paddy rice areas, c shows the total area of highland paddy rice, combining earth observation data from 2000 to 2020 with model predictions for 2021–2035.

Discussion

Understanding the distribution of paddy rice fields in the Asian highlands, along with their cultivation status and economic importance, is crucial for future food security and economic development. Our findings reveal a scarce distribution of paddy rice fields on the Tibetan Plateau itself, but a relatively higher concentration in the surrounding highland regions. Notably, extensive rice-growing areas are located in the Tianshan-Tarim Basin, the Hetao Plain along the Yellow River, and the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau (Fig. 1). In these regions, farmers primarily cultivate specific rice varieties, often rotating them with other crops like wheat and soybeans16,20,21,22,23,24. These rice products, appreciated for their high nutritional value, excellent taste, and strong market acceptance, enhance local food security and people’s dietary diversity while providing significant economic benefits to the communities16,20,21,22,23,24. For example, Jumla Marsi rice (Oryza sativa var. japonica), as a rice variety grown in Nepal’s Himalayan region, is particularly rich in protein, flavonoids, antioxidants, and essential minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, and iron20,21. Its high fiber and low carbohydrate content make it beneficial for individuals with obesity or diabetes, while its traditional biological cultivation without synthesized chemicals further enhances its market appeal20,21. Similarly, rice farming in Xinjiang’s highlands in China, where high-quality varieties such as Japan’s Akita Komachi have widely been introduced, has achieved economic returns exceeding those of other grains and is comparable to cash crops like cotton22. Moreover, cultivating paddy rice is the most effective method for improving the saline and alkaline soils found in highland regions such as Xinjiang, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia’s Hetao Plain22,23,24. The irrigation practices involved in paddy rice farming enhance soil quality, enabling a transition to other crops within two to three years and leading to greater long-term economic benefits for these areas22,23,24.

However, many Asian highland regions continue to experience low rice yields due to underdeveloped irrigation systems and limited mechanization. For instance, the average rice yield is only 1.7 t/ha in Jumla, Nepal20, and 1.96 t/ha in Huinong, Ningxia25. In contrast, Xinjiang, a region also faces typical highland climatic challenges such as aridity and significant temperature fluctuations, achieves much higher rice yields ranging from 6 to 15 t/ha22,23. This high productivity in Xinjiang is mainly a result of scientifically selected varieties, advanced mechanized planting methods, and automated farming systems22,23. Replicating Xinjiang’s achievements in other highland regions would require increased investment in irrigation infrastructure, mechanization, and crop breeding, where agroecological and socio‑economic conditions warrant. These investments are enabling conditions rather than guarantees of sustainability; sustainable paddy production depends on context‑specific water governance, environmental safeguards, and locally adapted agronomy that deliver gains in productivity, livelihoods, and regional food security.

Understanding the key factors influencing rice cultivation in the Asian highlands is essential for guiding future agricultural development. Our analysis revealed that altitude is the most significant factor among 13 variables in our models (Fig. 2), indicating that higher altitudes negatively affect the extent of paddy rice fields in these regions. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that the abundance of vegetation and crops tends to decrease as altitudes increases in Asian highlands16,26,27. Interestingly, the negative impact of altitude decreases rapidly between 1500 and 2000 ma.s.l., stabilizing after 2000 ma.s.l. One possible explanation is that at higher altitudes, increased solar radiation intensity may partially offset the adverse effects of cooler temperatures and lower precipitation13,16. Microclimatic conditions, such as sheltered valleys and south-facing slopes, may also create favorable environments for rice growth despite the high altitude21. Additionally, cultivating cold-tolerant rice varieties and adopting specialized agronomic practices can also mitigate the negative impacts of altitude increasing15. Collectively, these factors enable the potential cultivation of rice at higher altitudes under specific conditions, challenging the traditional notion that higher altitude regions, such as those above 2000 m a.s.l., are generally less suitable for paddy rice farming. While local slope is a key site‑scale constraint in very rugged mountains (e.g., the Hengduan), at our 0.5° resolution, slope is effectively proxied by elevation range and by the legacy‑of‑cultivation variable that encodes existing terraces and irrigation. Future higher‑resolution (≤30 m) suitability analyses could incorporate slope distribution metrics (e.g., area <5°) once consistent wall‑to‑wall DEMs are available. In addition, our 0.5° design cannot resolve within‑catchment proximity to melt‑fed canals or water‑rights/reservoir operations; glacier cover thus serves as an aggregate proxy for meltwater reliability. High‑resolution (≤30 m) suitability analyses should explicitly incorporate distance to glacier‑fed channels alongside slope and terrace extent.

In addition to ‘Altitude’, rice cultivation in Asian highlands is affected at a lower degree by socioeconomic factors, including ‘GDP’ and ‘population density’. Both the ‘GDP’ and ‘population density’ positively affect paddy rice fields, but their effects are nonlinear. Specifically, the positive impact of ‘population density’ increases up to a certain level and then decreases, while the initially strong positive influence of ‘GDP’ exponentially decreases as the GDP levels rise. This pattern likely suggests that rice cultivation in many Asian highland regions remains labor-intensive and lacks substantial capital investment, consistent with recent surveys28,29. To enhance future productivity and reduce reliance on manual labor, efforts should focus on promoting intensive agricultural practices and increasing mechanization. Moreover, as ‘GDP’ continues to rise, the diminishing positive effect on rice cultivation may indicate a shift toward non-agricultural sectors or higher-value crops, potentially affecting local food security. In this context, policymakers should recognize these trends and implement strategies to support sustainable rice cultivation in these regions.

Seasonal temperature, seasonal precipitation, and glacier coverage are also important factors in paddy rice fields in Asian highland regions. Temperatures in all seasons positively affect rice growth, likely because the generally low temperatures in Asian highlands limit cultivation. Summer temperatures are particularly important as they align with the rice growing season30,31. In contrast, precipitation in winter, spring, and summer negatively impacts paddy rice fields, with winter and spring precipitations having a greater effect—possibly due to deeper frozen soil layers and damaged soil structure unfavorable for crop growth. Summer precipitation can increase cloud cover, therefore reducing sunlight and temperatures, which are more essential for paddy rice development in Asian highlands13,21. However, as precipitation further increases, these adverse effects lessen, likely suggesting that sufficient water resources and improved soil moisture gradually offset their drawbacks. Conversely, Autumn precipitation promotes paddy rice fields, possibly because it supports critical grain-filling and maturation stages and mitigates rapid temperature declines30,31. Glacier coverage also supports paddy rice fields in Asian highlands, likely by supplying a stable source of meltwater for irrigation during late spring and summer18,32,33. These findings highlight the necessity of adapting agricultural practices to evolving climatic conditions. Building on these understandings, we should prioritize expanding Asian highland rice cultivation in warmer, less rainy areas that are close to abundant glacial water sources, such as the southern slopes of the Himalayas. This strategy will help address climate change impacts, ensuring a more stable water supply, and enhance the resilience to variable climatic conditions.

The Asian highlands hold significant potential for future rice cultivation but are often missing from the forward-looking strategies of global organizations like the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)4,34,35. Our study reveals that highland rice paddy fields are projected to increase continuously since 2021, potentially expanding by approximately 60% to reach 1.926 kha by 2035. This growth could represent between 2.1% and 5.5% of the global rice production area, which totals 523.9 kha according to FAO’s 2024 survey. Our simulation also indicates that regions such as the western Tarim Basin and the southern slopes of the Himalayas show significant potential for rice cultivation expansion, while areas in the southern Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau are projected to decrease (Fig. 3). This predicted growth, mainly driven by the warming trend in the highlands and the melting of glaciers that have increased water availability, could play a crucial role in enhancing food security and reducing poverty, particularly among the many impoverished communities residing there9,17,18,32. The expansion of highland paddy rice fields also offers opportunities to rehabilitate the large areas of saline-alkali soils prevalent in these regions22,23,24. Additionally, this shift reflects broader agricultural trends in Asia, where climate change and population pressures are driving agriculture towards regions of higher altitudes and more northern latitudes9,17,36,37,38. By expanding rice cultivation in Asian highlands, it is possible to increase the resilience of food systems to climate change and provide sustainable solutions to meet future food demands.

Nevertheless, any expansion suggested by our models reflects biophysical feasibility rather than a recommendation for land conversion, and the predicted expansion in the future may face significant challenges from climate change, including increased risks of extreme weather events, geological hazards3,39,40, and greater threats from pests and diseases36,41. Furthermore, the expansion, especially if it encroaches on natural ecosystems, may generate adverse environmental impacts. Evidence from Southeast Asia shows that highland cropland expansion has been accompanied by forest loss and fragmentation37, reinforcing the concern that expanding agriculture in Asian highlands may disrupt local ecosystems and increase habitat fragmentation, leading to significant biodiversity loss9,42. More irrigation demands could strain water and energy resources43, alter environmental flows, and the expansion of paddy fields may elevate regional greenhouse gas emissions, particularly methane and nitrous oxide44,45. Accordingly, we adopt a precautionary framing and recommend a strict “avoid–minimize–restore–offset” mitigation hierarchy that prioritizes avoiding conversion of natural ecosystems before any intensification or expansion proceeds. To effectively address these challenges, some precautionary measures should be taken to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change and cultivation expansion.

First, adopt explicit land‑use safeguards to avoid conversion of natural ecosystems: prioritize siting on already converted or degraded lands (e.g., saline–alkali soils or fallows) near existing irrigation, and exclude primary forests, natural grasslands, wetlands, and other critical habitats; use landscape‑scale planning that overlays predicted suitability with protected‑area and habitat‑intactness layers to minimize fragmentation and edge effects9,37,42. Second, implementing sustainable climate-resilient infrastructure, including efficient irrigation systems (e.g., alternate wetting and drying, canal lining, and basin‑scale water accounting to maintain environmental flows), and nature-based solutions for mountain catchments to help preserve water resources, reduce energy consumption, and reduce impacts on local ecosystems43,46,47. Third, developing and promoting rice varieties that are resilient to high-altitude conditions, pests, and diseases, to increase crop yields and reduce the need for chemical fertilizers and pesticides15. Fourth, adopting environmentally friendly farming practices, such as minimizing the use of harmful agrochemicals and practicing crop rotation, can protect local ecosystems and maintain soil health48. Additionally, integrating biodiversity conservation into agricultural planning by preserving natural habitats and promoting agroforestry, for example, by maintaining riparian buffers and wildlife corridors, setting no‑net‑loss (or net‑gain) biodiversity targets, and establishing independent ecological monitoring, can help reduce habitat fragmentation and preserve biodiversity42. Furthermore, government support through policies and incentives will be crucial to encourage sustainable practices and enforce environmental protection regulations48, including mandatory environmental and social impact assessments, safeguards tied to water licenses, and incentives for low‑emission rice practices that jointly reduce CH4 and N2O45,46. Finally, our projections indicate potential suitability but do not incorporate legal protections or biodiversity‑priority layers; thus they should be used to identify “where not to expand” as much as “where expansion might be considered” under strict safeguards9,37,42.

In summary, our research demonstrates the significant yet often overlooked potential of the Asian highlands for paddy rice fields, presenting substantial opportunities to enhance food security and stimulate regional economic development. Despite these promising findings, our simulation has limitations. Due to data constraints, we did not include the impact of government policies and specific farming practices such as China’s land compensation policies that can influence planting choices48,49. Moreover, the modelling framework does not explicitly represent competing land‑use demands or trade/price‑mediated demand; demand pressures are captured only indirectly via population and GDP, so the projections do not constitute a land‑system equilibrium. Regarding climate forcing, we rely on the PARIS‑2 C ensemble (HadGEM3‑GC31‑MM, 50 members), which samples internal variability around an ~2 °C stabilization pathway rather than contrasting radiative‑forcing scenarios (e.g., RCP2.6/4.5/8.5); this choice narrows scenario uncertainty and centers results on mid‑range conditions. Glacier cover is kept constant in the projections for 2021–2035 as a simplifying assumption, which may overstate irrigation reliability in glacier‑fed basins and should be considered when interpreting regional potentials. In addition, to further improve the accuracy of our 2035 predictions, future studies should incorporate more robust modeling and validation strategies. For example, applying rigorous cross-validation, exploring alternative machine learning models, or introducing additional predictive variables could refine the model’s performance and enhance the reliability of our projections. We call for increased research attention to fully realize this region’s agricultural potential and address the associated environmental and socio-economic challenges. By acknowledging both the advantages and challenges, policymakers and stakeholders can develop targeted strategies that capitalize on the farming potential while promoting sustainable and resilient agricultural practices.

Methods

Study area

We focused our research on the region between 16° N and 50°N latitude and 60° E and 122° E longitude. We divided it into 0.5° × 0.5° grid cells, with each grid cell measuring approximately 55 km by 55 km (~2440 km²). Using the ETOPO2022 dataset at a resolution of 60 arc-seconds50, we calculated the average altitudes for each grid cell. We defined grid cells with an average altitude above 1000 ma.s.l. as the Asian highlands, which constitute our study area (Supplementary Fig. 4). This selection resulted in 72,954 grid cells spanning 8.5 × 106 km2. Within this area, approximately 35% of the grid cells are at altitudes between 1000 and 1500 ma.s.l., ~15% between 1500 and 2000 ma.s.l., and ~50% above 2000 ma.s.l. Various Asian Mountain systems and nearby basins are included in our research area, such as Hindu Kush-Himalayas, Tibetan Plateau, Tianshan Mountains, Altai Mountains, Tarim Basin, and Yellow River Basin. The climate in our study area is typically cold and dry, but shows a warmer and wetter trend during the 21st century. According to GHCN CAMS (analyzed global land surface temperatures from 1948 to near present with a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°)51, the average temperatures in our study areas during the first decade of the 21st century were 277.42 K in spring (March–May), 278.76 K in summer (June–August), 276.73 K in autumn (September–November), and 264.05 K in winter (December–February). In the second decade of the 21st century, these average temperatures increased to 277.66 K, 288.06 K, 276.95 K, and 264.05 K, respectively. Notably, the summer mean reached 288.06 K, implying an ≈10 K rise relative to the previous decade, whereas winter, spring, and autumn changed only marginally over the same period. This seasonally concentrated increase highlights a disproportionate intensification of summer conditions. According to GPCC (analyzed global land surface monthly precipitation from 1891 to near present with a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°)52, the average precipitation in our study areas during the first decade of the 21st century were 81.87 mm in spring (March–May), 210.45 mm in summer (June–August), 78.68 mm in autumn (September–November), and 32.83 mm in winter (December-February). In the second decade of the 21st century, these average precipitations increased to 89.08 mm, 223.57 mm, 87.65 mm, and 33.80 mm, respectively. Our research area has a relatively low population density and an underdeveloped economy. Based on a global population mapping projection with 7.5 arc-minute spatial resolution and decadal intervals53, the population of our research area in 2000 was 278.16 million. By 2035, it is projected to grow to 299.98 million under Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs, Scenario 1) (SSP1), 321.53 million under SSP2, 341.88 million under SSP3, 312.35 million under SSP4, and 297.84 million under SSP5. Supplementary Fig. 5 presents a photograph depicting rice paddy fields in the Asian highlands.

Measurement of paddy rice extent

To measure the paddy rice extent in our study area (16°N–50°N, 60°E–122°E), we used the APRA500 dataset19, covering a latitude range from 11.57°S to 54.23°N and a longitude range from 60.11°E to 152.40°E. Derived from MODIS imagery, APRA500 integrates land‑use classifications, 500 m‑resolution topography, and rice‑growing phenological features to identify paddy rice pixels across major Asian countries from 2000 to 2020. It is worth noting that APRA500 identifies paddy rice using rice phenological signatures and is not designed to map upland (rain‑fed) rice. We aggregate only APRA500 paddy pixels to compute the paddy share per 0.5° cell; therefore, our modeled outcome represents irrigated paddy extent, not total rice area. The area for each pixel is 0.25 km² at the equator, decreasing to approximately ~0.20 km² at 30°N, and ~0.15 km² at 45°N. To calculate the actual area of each pixel, we apply Albers equal-area projection to the pixel data, using latitude limits of 12°S and 55°N, and a central longitude of 90°E. We also counted the proportion of the rice planting pixels within each 0.5° × 0.5°grid of the study area, which will be used as the target variable for training the Random Forest model in our study.

Potential factor selection and random forest model development

To arrive at a parsimonious yet comprehensive predictor set, we applied three explicit filters: (i) proven agronomic relevance—variables had to be repeatedly cited in peer‑reviewed work as determinants of high‑elevation rice performance; (ii) data quality and coverage—gridded layers needed wall‑to‑wall availability for 2000–2020 at 500 m resolution with <5% missing cells in our domain; and (iii) low collinearity—for any pair with |Spearman ρ| > 0.70 we retained only the member showing higher permutation importance (>1%) in a pilot Random‑Forest run.

It is important to note that in the topographic domain, we computed candidate metrics, including mean slope and terrain ruggedness, in addition to mean elevation and elevation range. At the 0.5° grid used for model training, slope metrics were strongly collinear with elevation range (|Spearman ρ| > 0.70 in pilot RF runs); following our pre‑specified low‑collinearity rule, we retained elevation range as the single regional‑scale relief indicator to avoid redundancy and preserve interpretability. In terms of cryosphere representation and river proximity, we included glacier cover rate per grid as a proxy for the reliability of meltwater runoff at high elevation. Because our analysis is conducted at 0.5° (~55 km), a direct ‘distance to glacier‑fed river’ metric is expected to be strongly collinear with glacier coverage and relief and to overlap with the planting‑history variable that encodes existing irrigation infrastructure; such redundancy is excluded by our prespecified low‑collinearity rule.

Drawing on the latest insights from agro-climatology, high-mountain hydrology, and development economics, we assembled a thirteen-variable suite that captures the climate, geo-environmental, and socio-economic foundations of paddy-rice cultivation in the Asian highlands. Specifically, seasonal temperature and precipitation—eight climate indicators—govern rice phenology and evapotranspiration53; moreover, these climatic factors regulate the duration of field inundation, and in high‑elevation terraces, even slight shifts can determine whether paddies remain adequately flooded during critical growth stages54. Mean altitude, altitudinal range, and glacier-cover rate, in turn, reflect thermal regimes, topographic complexity, and the reliability of melt-water runoff, which above roughly 2000 m is often the sole perennial irrigation source55. Population density and GDP per capita capture labor availability, market demand, and the financial capacity to invest in terraces, pumps, and improved seed; regions with higher values on either metric typically adopt water-saving, yield-enhancing technologies sooner, expanding rice area and productivity56. A binary legacy variable flags whether a pixel was under paddy cultivation in the previous year, recognizing the strong path dependence created once irrigation channels, bunds, and farmer know-how are in place. Leveraging these factors, we trained an ensemble of 50 Random-Forest models whose repeated resampling reduces estimation variance and yields robust importance rankings, providing a rigorous, quantitative basis for understanding—and ultimately managing—the climatic, environmental, and socio-economic controls on high-altitude rice systems.

The study area was first partitioned into 0.5° × 0.5° grid cells, and only those with a mean above 1000 ma.s.l. were retained, yielding 3474 analysis units. Coupling these cells with annual data for 2000–2020 produced 72,954 grid‑year samples for model training. An annual dataset of paddy rice area from 2000 to 2020, sourced from the APRA500 dataset19 as described in the ‘Measurement of Paddy Rice Extent’ section, was interpolated to the grid cells and used as the target variable for model training. Seasonal temperature data for model training, spanning from 2000 to 2020, was sourced from NCEI’s GHCN CAMS at monthly intervals with a 0.5° × 0.5° resolution51. Seasonal precipitation data for model training were obtained from the GPCC Monitoring Product (Version 2022), available at monthly intervals with a 0.5° × 0.5° resolution from 2000 to 202052. We first interpolated these climate data to the target grids, then averaged them into seasonal scales: spring (March to May), summer (June to August), autumn (September to November), and winter (December to February). These climate datasets were used as input features for model training. The altitude dataset was obtained from the 2022 ETOPO Ice Surface Elevation dataset at 60 arc-seconds50, which was then interpolated into the target grids and assumed to remain constant from 2000 to 2020. We also calculated the altitude range in each target grid cell by subtracting the minimum from the maximum altitude within the cell. This altitude range was assumed to remain constant from 2000 to 2020. The glacier cover rate was derived from the GAMDAM glacier inventory, which includes 134,770 glaciers with a total area of 100,693 ± 15,103 km2, based on 453 Landsat images from 1990 to 201057. The glacier cover rate at target grid cells was calculated and kept constant over the 2000 to 2020. The population data for model training were obtained from Global One-Eighth Degree Population Base Year and Projection Grids Based on the SSPs (Revision 01)53. This global dataset had a resolution of 7.5 arcminutes, included base data for 2000, and projections with decadal resolution from 2010 to 2100 under five SSPs. We formed an ensemble mean of the five CMIP6 SSP scenarios at decadal resolution for 2021–2100 and linearly interpolated these values to annual scale for each target grid cell for model training. GDP data for model training was derived from a global GDP dataset, which includes historical data from 2000 to 2020 with a resolution of 30 arc-seconds at annual intervals, and projection data from 2030 to 2100 at decadal intervals under five SSPs58. We interpolated these historical GDP data annually and further interpolated them to target grid cells for model training.

In this study, we used MATLAB’s ‘TreeBagger’ function to construct the Random Forest regression model. The fraction of observations randomly selected with replacement for each bootstrap replica, known as ‘InBagFraction’, was set to its default value of 1. We used the R2 score to evaluate the performance of the RF model. To further evaluate the predictive performance of our model, we calculated the Residual Prediction Deviation (RPD). If the data greater than 2.0, this may indicate a good predictive model suitable for quantitative predictions. Feature importance was quantified by evaluating the regression prediction error on out-of-bag (OOB) estimates using MATLAB’s ‘OOBPermutedPredictorDeltaError’ function. Hyperparameter setting involved varying ‘Ntree’ at 30, 50, 80, and 100, ‘MinLeafSize’ at 1, 2, 3, and 4, and ‘NumPredictorsToSample’ at 6, 8, 10, and 12. The optimal model configuration, which achieved the highest R2 score, was found to be Ntree = 100, MinLeafSize = 2, and NumPredictorsToSample = 8. To ensure robustness and reliability, we built 50 Random Forest models using the same hyperparameter scheme but different random seeds. To represent feature importance in RF models, we use a method that measures the change in out-of-bag prediction error when each feature is randomly shuffled, as implemented in MATLAB’s rf function. The Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) for each feature were calculated using MATLAB’s calculate_ALE function. This method quantifies the importance of each feature by averaging the impact of feature value changes on the model’s output across a specified number of intervals, which in this case is set to 10.

Predicting paddy rice extent with Random Forest Models

To predict the extent of paddy rice from 2021 to 2035, we applied the trained Random Forest models to the predictive features of climate data (seasonal temperature and precipitation) and socioeconomic data (population and GDP). The predictive features of the climate data were sourced from the large-ensemble 21st-century monthly hydro-climatological forcing dataset for the PARIS 2C (P2C) scenario59. The P2C scenario extends from the Paris Agreement’s NDCs and aligns with its long-term goals for aiming to limit and stabilize human-induced global climate warming to 2 °C by the end of this century. This ensemble dataset comprises 900 climate simulations, which were derived from 50 scenarios using 18 climate models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). Each simulation includes monthly dataset for nine key meteorological variables, from 2021 to 2100, with a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°. Here, we utilized 50 climate simulation results generated by the HadGEM3-GC31-MM model from the ensemble dataset. We first extracted the monthly near-surface temperature and precipitation variables from these simulations and aggregated them to a seasonal scale from 2021 to 2035, following the same methods as described in the training data preparation section. These seasonal datasets were used as inputs for 50 Random Forest models, each receiving different data to generate a range of forecasts.

For the three input forecasted geo-environmental features—mean altitude, altitude range, and glacier cover rate—same data as the training dataset was used, given the expected stability of these features over the relatively short prediction period of 2021 to 2035. For population and GDP, both the forecasted and training data were sourced from the same dataset, while the forecasted dataset includes five SSP scenarios at a decadal resolution from 2020 to 210053,58. We randomly selected data from one SSP scenario, then extrapolated it to an annual scale from 2021 to 2035 for the target grid cells. We used this data to train 50 Random Forest models, each model receiving predictive features from a single SSP scenario that was randomly assigned to it. A detailed description of the target feature and input features used for both model training and prediction can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Supplementary Fig. 6 is a flowchart illustrating the spatial-temporal distribution of the datasets used in the RF model. The results are presented as the median values from results of 50 RF models, with uncertainty indicated by the interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code is currently employed to conduct an in-depth analysis of comprehensive data and will be provided upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Muthayya, S. et al. An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1324, 7–14 (2014).

Global Rice Science Partnership. Rice Agri-Food System CRP, RICE (International Rice Research Institute, 2023).

Chan, F. K. S. et al. Food security in climatic extremes: challenges and opportunities for China. Cell. Rep. Sustain. 1, 2 (2024).

OECD-FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2023-2032. OECD https://doi.org/10.1787/08801ab7-en (2023).

Wei, R. et al. Heavy metal concentrations in rice that meet safety standards can still pose a risk to human health. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 84 (2023).

Dong, Y. et al. Microplastic particles increase arsenic toxicity to rice seedlings. Environ. Pollut. 259, 113892 (2020).

Muehe, E. M. et al. Rice production threatened by coupled stresses of climate and soil arsenic. Nat. Commun. 10, 4985 (2019).

Yuan, S. et al. Sustainable intensification for a larger global rice bowl. Nat. Commun. 12, 7163 (2021).

Yang, C. et al. Human expansion into Asian highlands in the 21st Century and its effects. Nat. Commu. 13, 4955 (2022).

Xu, J. & Grumbine, R. E. Building ecosystem resilience for climate change adaptation in the Asian highlands. Wires Clim Change 5, 709–718 (2014).

Bohner, J. General climatic controls and topoclimatic variations in Central and High Asia. Boreas 35, 279–295 (2006).

Lalande, M. et al. Climate change in the High Mountain Asia in CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 1061–1098 (2021).

Uhlig, H. Geoecological controls on high-altitude rice cultivation in the Himalayas and mountain regions of southeast Asia. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 10, 519–529 (1978).

Sun, X. et al. Natural variation of DROT1 confers drought adaptation in upland rice. Nat. Commun. 13, 4265 (2022).

Ahmadi, N. Upland rice for the highlands: new varieties and sustainable cropping systems to face food security. Promising prospects for the global challenges of rice production the world will face in the coming years. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 166, 61–67 (2004).

Maina, F. Z. et al. Warming, increase in precipitation, and irrigation enhance greening in High Mountain Asia. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 43 (2022).

Biemans, H. et al. Importance of snow and glacier meltwater for agriculture on the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Nat. Sustain. 2, 594–601 (2019).

Li, J. & Yuan, J. Research progress in effects of different altitude on rice yield and quality in China. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 2, 340–344 (2012).

Han, J. et al. Annual paddy rice planting area and cropping intensity datasets and their dynamics in the Asian monsoon region from 2000 to 2020. Agric. Syst. 200, 103437 (2022).

Gautam, R. et al. Importance of world high altitude Jumli Marshi rice with cultivation practices. Heliyon 8, e08885 (2022).

Paudel, M. N. Rice (Oryza sativa L) cultivation in the highest elevation of the world. Agron. J. Nepal 2, 31–41 (2011).

Buhailiqem, A. et al. Effects of irrigation and nitrogen fertilizer application on growth, yield and quality of different rice varieties in arid areas of Xinjiang. Plant Genet. Res. 20, 309–318 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Simulation study of the climate change impact on the rice and its adaptability in Ningxia province (in Chinese). Adv. Earth Sci. 28, 1248 (2013).

Cui, D. et al. Genetic structure and isolation by altitude in rice landraces of Yunnan, China revealed by nucleotide and microsatellite marker polymorphisms. PLoS ONE 12, e0175731 (2017).

Chen, S. & Zhu, J. Shizuishan City’s Huinong District rice production status and development suggestions (in Chinese). Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 4, 47–47 (2018).

Gao, M. et al. Divergent changes in the elevational gradient of vegetation activities over the last 30 years. Nat. Commun. 10, 2970 (2019).

Ghosh, B. N. et al. Elevation, slope aspect and integrated nutrient management effects on crop productivity and soil quality in the North-West Himalayas, India. J. Mt. Sci. 11, 1208–1217 (2014).

Prabhakar, S. V. R. K. A succinct review and analysis of drivers and impacts of agricultural land transformations in Asia. Land Use Policy 102, 105238 (2021).

Briones, R. & Felipe, J. Agriculture and structural transformation in developing Asia: review and outlook. ADB Econ. Work. Pap. Ser. 363 (2013).

Sánchez, B. et al. Temperatures and the growth and development of maize and rice: a review. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 408–417 (2014).

Chung, N. T. et al. Impacts of seasonal climate variability on rice production in the central highlands of Vietnam. Agric. Sci. Procedia 5, 83–88 (2015).

Pritchard, H. D. Asia’s glaciers are a regionally important buffer against drought. Nature 545, 169–174 (2017).

Triplett, A. & Condon, L. E. Climate warming-driven changes in the cryosphere and their impact on groundwater-surface water interactions in the Heihe River Basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2022, 1–32 (2022).

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, W. F. P. & WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024. FAO https://openknowledge.fao.org (2024).

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, W. F. P. & WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. FAO https://openknowledge.fao.org (2023).

Chen, W. et al. Untangling the increasing elevation of cropland in China from 1980 to 2020. Geogr. Sustain. 4, 281–293 (2023).

Zeng, Z. et al. Highland cropland expansion and forest loss in Southeast Asia in the twenty-first century. Nat. Geosci. 11, 556–562 (2018).

Liang, S. et al. Climate-mediated dynamics of the northern limit of paddy rice in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 064008 (2021).

Piao, S. et al. The impacts of climate change on water resources and agriculture in China. Nature 467, 43–51 (2010).

Li, D. et al. High Mountain Asia hydropower systems threatened by climate-driven landscape instability. Nat. Geosci. 15, 520–530 (2022).

Nakato, G. V. et al. Influence of altitude as a proxy for temperature on key Musa pests and diseases in watershed areas of Burundi and Rwanda. Heliyon 9, e13854 (2023).

Farhadinia, M. S. et al. Current trends suggest most Asian countries are unlikely to meet future biodiversity targets on protected areas. Commun. Biol. 5, 1221 (2022).

Mehta, P. et al. Half of twenty-first century global irrigation expansion has been in water-stressed regions. Nat. Water. 2, 254–261 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. Fingerprint of rice paddies in spatial–temporal dynamics of atmospheric methane concentration in monsoon Asia. Nat. Commu. 11, 554 (2020).

Qian, H. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation in rice agriculture. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 716–732 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Sustainable irrigation and climate feedbacks. Nat. Food. 4, 654–663 (2023).

Holden, P. B. et al. Nature-based solutions in mountain catchments reduce impact of anthropogenic climate change on drought streamflow. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 51 (2022).

Cui, Z. et al. Pursuing sustainable productivity with millions of smallholder farmers. Nature 555, 363–366 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Urbanization in China drives farmland uphill under the constraint of the requisition–compensation balance. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154895 (2022).

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. ETOPO 2022 15 arc-second global relief model. NOAA Natl. Centers Environ. Inform. https://doi.org/10.25921/fd45-gt74 (2022).

Fan, Y. & van den Dool, H. A global monthly land surface air temperature analysis for 1948-present. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D01103 (2008).

Schneider, U. et al. GPCC monitoring product: near real-time monthly land-surface precipitation from rain-gauges based on SYNOP and CLIMAT data. https://doi.org/10.5676/DWD_GPCC/MP_M_V2022_100 (2022).

Jones, B. & O’Neill, B. C. Global one-eighth degree population base year and projection grids based on the shared socioeconomic pathways, Revision 01. https://doi.org/10.7927/m30p-j498 (2020).

Rupngam, T. & Messiga, A. J. Unraveling the interactions between flooding dynamics and agricultural productivity in a changing climate. Sustainability 16, 6141 (2024).

Zhou, Z. et al. Modeling the effects of elevation and precipitation on Rice (Oryza sativa L.) production considering multiple planting methods and cultivars in Central China. Sci. Total Environ. 813, 152679 (2022).

Kularathne, S. et al. Impact of economic indicators on rice production: a machine learning approach in Sri Lanka. PLoS ONE 19, e0303883 (2024).

Sakai, A. Brief communication: updated GAMDAM glacier inventory over the high mountain asia. Cryosphere 13, 2043–2049 (2019).

Wang, T. & Sun, F. Global gridded GDP data set consistent with the shared socioeconomic pathways. Sci. Data 9, 221 (2022).

Gao, X. et al. A large ensemble global dataset for climate impact assessments. Sci. Data 10, 801 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key Special Project of “Intergovernmental International Scientific and Technological Innovation Cooperation” in the National Key Research and Development Program (2025YFE0111302), the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (2024J013), and the Natural Science Foundation of Xiamen, China (3502Z202573087, 3502Z202572040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft. C.W.: Conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing—review, and editing. L.M.N.: Writing—review and editing. Z.L.: Writing—review and editing. G.L.: Supervision, project administration, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, J., Wang, C., Nunes, L.M. et al. The historical distribution and future expansion of paddy rice fields in Asian highlands. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 65 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00107-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00107-8