Abstract

Dietary diversification increased edible vegetable oil (EVO) demand. Climate change intensifies temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought (terms to above extremes co-occurring spatially and temporally), risking nationwide oil crops production and EVO supply, but were rarely quantified. We developed a panel model using heat degree days (HDD), Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), irrigation conditions, and year (representing agricultural technology) as yield predictors. Year-types were categorized by extreme climate-induced production losses: normal, temporal-spatial extreme heat (HDD change), temporal-spatial drought (SPEI change), and temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought (HDD and SPEI change). Historical, extreme heat and drought caused a 6.6% (4.0%), 5.6% (3.6%), and 3.5% (2.1%) yield loss for soybean, peanut, and rapeseed without (with) irrigation, respectively. Future temporal-spatial compound extreme years: crop yields would decrease over 14.0% (12.8%), EVO self-sufficiency rate would decrease to 15.5–16.5% (19.0–21.9%) without (with) area expanding, indicating alarming oil crop yield reduction under extreme climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The agricultural food systems are facing severe challenges, which are feeding the rapidly increasing population and the changing structure of food consumption1. Edible vegetable oils (EVO) are major energy resources in the human diet, and they play a critical role in agricultural food systems2. China is the largest consumer of EVO and the second highest producer and importer in the world3,4. In 2020, China’s self-sufficiency rate of EVO was only 31.5%5. The top three oil crops are soybean, peanut and rapeseed, which collectively account for over 70% of national total EVO production4. Therefore, it is imperative to increase production of these three oil crops for improving the country’s self-sufficiency rate of EVO. Increases in greenhouse gas concentrations since pre industrial times have led to climate change, characterized primarily by increasing temperature. From 2011 to 2020, the global surface average temperature increased by an average of 1.09 °C (ranging from 0.95 to 1.20 °C) as compared to the period of 1850–1990; this warming trend is expected to continue in the future6. It is a well-known fact that climate change affects crop yields; about a third of the global crop yield variability was attributed to the changing climate7,8. Under the background of climate change, extreme climate events, especially extreme heat and drought, have become more frequent and intense, which negatively affects the crop yields. Understanding how extreme heat and drought changes impacts main oil crops yield is essential to national EVO industry.

Each additional 0.5 °C of global warming could cause discernible increases in the intensity and frequency of extreme heat (very likely) and agricultural drought (highly confident)6,9. Drought and extreme heat are major abiotic stresses that severely limit global crop growth and productivity10,11,12. Extreme heat would decrease crop yields because they cause direct thermal stress to crop plants and also induce indirect drought stress by raising atmospheric aridity10. For rainfed soybean, each day >30 °C diminishes the crop yields by up to 6%11. Drought is an extreme climate event characterized by a long-term precipitation deficit, which would lead to a soil water deficit. The impacts of drought on crops include: (i) the soil moisture content is lower than the water requirement for crop, then crop growth is limited, resulting in reduced crop yield or loss of harvest; and (ii) under drought conditions, crop plants would reduce water transpiration and photosynthesis rate, affecting organic matter synthesis, and ultimately affecting crop yield12. From 1980 to 2015, drought reduced global crop’ yields by over 21%13. The yield decreasing caused by extreme heat and drought occurring temporally was more than extreme heat or drought alone would14,15. Meanwhile, historical global warming has already increased the probability of extreme heat and drought co-occurring spatially and temporally16. And this could potentially accumulate hazardous impacts on crop production and pose amplifying threats to crop yields. Global drought probability was predicted to increase by 40% by the middle of the 21 century14,17. Existing studies predominantly employ statistical methods to investigate the probability of compound hot-dry events and their impacts on yield, or utilize long-term single-site experiments to elucidate the underlying mechanisms affecting crop yield15,18,19. In China, extreme heat and drought co-occurring spatially and temporally were projected to be at least 1.6 times more frequent during the crop growing season in 2036–205020. And the cropland net primary productivity losses in China are primarily influenced by compound extreme heat and drought events21. For soybean, the negative impacts of compound extreme heat and drought were 4 and 3 times larger than the impacts of extreme heat or drought alone22. However, rarely researches have focused on above extreme impacts on oil crops production and self-sufficiency rate of EVO.

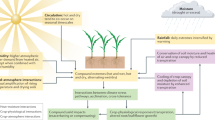

The direct impacts of extreme climate on crops manifests through changes in both yield and total production23. Furthermore, quantifying the impacts of one or more extreme climate on total production requires simultaneous consideration of the co-occurring of these extreme events on spatially (the same planting region) and temporally (during the same growth season). Such as, the co-occurring of extreme heat on spatially and temporally for soybean was refer to the spatially concurrent extreme heat events in soybean planting regions during a specific year, this would directly decrease national production. For oil crops, if a specific year subjected all three major oil crops to co-occurring of extreme heat on spatially and temporally, it would directly impact national oil crop production and EVO supply. Previous studies have mostly focused on the changing characteristics of extreme heat and drought co-occurring spatially and temporally during crop growth periods10,24,25,26. But rarely studies have quantified the impacts of above extreme climate events on oil crops yield and production. Besides yield, the co-occurring of extreme heat and drought spatially in crop planting region would influence total production and self-sufficiency rate of EVO nationwide. So, in this study, we term the extreme heat or drought co-occurring in both crop growth periods and different planting regions as temporal-spatial compound extreme heat or drought, and then quantified the above temporal-spatial compound extreme climate on oil crops yield, national production and EVO’s self-sufficiency rate.

In this study, we calculated the heat degree days (HDD) and Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) during oil crop growth seasons to reflect the impacts of extreme heat and drought, respectively. And constructed a panel model with HDD, SPEI, irrigation conditions, and year (agricultural technology impacts) as predictors of yield. On the basis of quantifying the impacts of HDD changes, SPEI changes, and both HDD and SPEI changes on oil crops yield, further incorporate the planting area to clarify the impact on production. Taking a 10% decrease in production as the threshold27, four types of years are classified: normal (production decrease < 10%), temporal-spatial extreme heat (production decrease lead only by HDD changes > 10%), temporal-spatial drought (production decrease lead only by SPEI changes > 10%), and temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought (production decrease lead by both HDD and SPEI > 10%). The objectives of this study were: (a) to quantify the impacts of changes in temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought on oil crops yields; and (b) to project the changes in oil crops yields and hence the change in the nation’s self-sufficiency rate of EVO in China under future climate scenarios.

Results

Historical oil crops and EVO productions

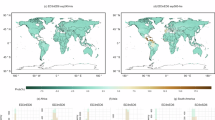

Soybean production was concentrated on the northern and the middle part of China; peanut production was concentrated on the western part of Northeast China, the southern part of North China Plain, and the southern part of South China; and rapeseed production was mainly in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 10). From 1981 to 2020, the planting areas of peanut and rapeseed increased at the rate of 0.8 and 0.6 Mha per decade respectively. The yields of peanut and rapeseed increased at the rates of 3.9 and 2.8 Mt per decade, respectively. From 2009 to 2015, the planting area and yield for soybeans substantially decreased. In 2016, the Chinese government issued several policies to support the national soybean production, which led to a rapid increase in the soybean’s planting area and hence increase the production (Fig. 1d, e)28. Due to the increases in the three oil crops' yields, the national EVO production increased. However, the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO dropped from 65.8% in 2000 to 26.7% in 2020 because the demand for EVO increased faster than the production did (Fig. 1f).

Top: Geographical distribution of the city-level a soybean, b peanut, and c rapeseed production in China. Bottom: Time series of d the planting area and e production for the three study oil crops (i.e., soybean, peanut, and rapeseed) from 1981 to 2020. f Time series of the national oil production, oil demand, and self-sufficiency rate of EVO from 2000 to 2020.

Impacts of extreme heat and drought on oil crops yields

In this study, we used the only HDD changes, only SPEI changes, and HDD and SPEI combined (HDD and SPEI) change to represent the impacts of extreme heat, drought, and compound of extreme heat and drought on three oil crops yield. From 1981 to 2014, the area-weighted HDD increased, and the area-weighted SPEI decreased (Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

For soybean without irrigation, extreme heat and drought decreased the yield by 3.1% (0.6–9.7%) and 4.1% (5.5–12.2%), respectively. The compound of extreme heat and drought decreased the yield by up to 17.6% (Fig. 3 and Table 1). With irrigation, extreme heat and drought changed the soybean yield by −2.4% (−8.7 to 1.2%) and −2.4% (−10.2 to 6.2%), respectively, and compound of above extreme decreased the yield by up to 17.3% (Fig. 2a–c and Table 1). The most pronounced negative impacts of compound extreme heat and drought on soybean yield occurred in the southern North China Plain and western Northeast China (Figs. 2 and 3).

Note: the numbers in the brackets indicate the lower and upper 95% quantiles of the data, and the value below the brackets is the area-weighted value. Top: a–c were spatial distribution of the impacts of HDD and SPEI, HDD and SPEI on soybean yield, respectively. Middle: d–f were the above impacts on peanut yield. Bottom: g–i were the above impacts on rapeseed yield.

For peanuts without irrigation, extreme heat decreased the yield by 1.2% while drought decreased by 4.7% (Fig. 3d–f). With irrigation, extreme heat and drought decreased yield by 0.8% and 3.0%, respectively; compound of extreme heat and drought decreased by up to 14.2% (Fig. 2d–f). In particular, peanut yield was more negatively affected by drought in the western part of North China Plain and the southwestern part of Southwest China (Figs. 2 and 3).

Note: the numbers in the brackets are the upper and lower 95% quantiles of the yield changes in all counties, the number below is the area-weighted yield change (%). Top: a–c were spatial distribution of the impacts of HDD & SPEI, HDD and SPEI on soybean yield, respectively. Middle: d–f were the above impacts on peanut yield. Bottom: g–i were the above impacts on rapeseed yield.

For rapeseed without irrigation, compound of extreme heat and drought decreased the yield by up to 11.1% (Fig. 3g–i), and extreme heat and drought decreased by 1.9% and 2.2%, respectively. With irrigation, extreme heat and drought decreased yield by 1.3% and 1.1%, respectively; and compound of extreme heat and drought decreased by about 2.1% (Fig. 2g–i). In particular, Rapeseed exhibited the greatest susceptibility to compound heat-drought events in the southern North China Plain and eastern Southwest China (Figs. 2, 3, and Supplementary Fig. 2).

If the percentage of effective irrigation area was kept at the level in 2014, HDD-induced oil crop yield reduction would be worse during the period of 2021–2060 than 1981–2014. Under SSP1-2.6, extreme heat would decrease the area-weighted yields for soybean, peanut, and rapeseed by 6.1%, 5.6%, and 7.2%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4b, e, h). Under SSP5-8.5, yields would decrease by 6.3% to 7.6% (Supplementary Fig. 5b, e, h). In particular, the North China Plain and southern Southwest China are projected to suffer more severe yield losses of oil crops from extreme heat than other regions. (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5 and Table S1).

Top: Scatter plots of soybean (a), peanut (b), and rapeseed (c) production in the planting area expansion situation for the historical period of 1981–2014 and the future period of 2021–2060 under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 in the study region. Bottom: Box-and-whisker plots of the percentage changes in production for soybean (d), peanut (e), and rapeseed (f) in the four types of study years (i.e., N normal, EH extreme heat, D drought, and CEHD compound extreme heat and drought, same definitions also apply in the remaining figures) for the historical period of 1981–2014 and the future period under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 in the study region.

a Scatter plots of the national EVO production in the planting area expansion situation for the historical period of 1981–2014 and the future period of 2021–2060 under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 in the study region. b Box-and-whisker plots of the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO from 2021 to 2060 in the expansion situation for the four types of study years under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5.8.5 in the study region. c Checkerboard plot of the reduction in national self-sufficiency rate of EVO (Note: the triangle symbols indicate a more than 10% reduction) corresponding to changes in HDD or SPEI from 2021 to 2060 under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5.8.5 in the study region.

By contrast, drought would cause less yield reduction than extreme heat would. Under SSP1-2.6 (SSP5-8.5), drought would reduce the area-weighted oil crops yields by 1.8 to 4.9% (2.2–5.5%) during 2021–2060 (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5 and Table S1). In particular, oil crop yields in the western Northeast China, the southern and western North China Plain, and southern Southwest China would suffer greater negative impacts from extreme heat than those in other regions (Supplementary Fig. 4 and 5). Under SSPs 1-2.6 and 5-8.5, compound of extreme heat and drought would reduce the oil crops yields by more than 9.0% and 9.8%, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 4a, d, g and 5a, d, g). The majority of the study cities showed a more than 10% yield reduction for the three oil crops, with an exception in the eastern part of Northeast China and the entire East China (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5).

Impacts of temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought on oil crops production

Combined with the oil crops planting area after adjustment (Supplementary Fig. 10, section “Future crops yield, planting area and EVO production projection” in “Method”), we further calculate the changes of crop production changes under extreme climate change. During the historical period, soybean, peanut, and rapeseed production were, on average, 11.6, 12.5, and 12.9 Mt. If the planting area was kept at the level in 2014, oil crop production would go down for the upcoming period of 2021–2060. Projected production would decrease to 10.8 and 10.6 Mt for soybean under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, respectively; to 11.7 and 11.6 Mt for peanut; and to 12.0 Mt for rapeseed under both SSPs (Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). During the growing season under SSP1-2.6 (SSP5-8.5), the frequencies of compound heat-drought, extreme heat, and drought were 47.5, 32.5 and 10.0% (57.5, 37.5 and 15.0%) for soybean, 45.0, 7.5 and 17.5% (70.0, 11.0 and 15.0%) for peanut, respectively. During the growing season for rapeseed, the frequencies of compound extreme heat and drought (only drought) would be 37.5 and 42.5% (22.5 and 27.5%) under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). If the planting area for oil crops were kept at the level in 2014 for the period of 2021–2060, the compound extreme heat and drought would reduce oil crops production. Compared to historical, production would decrease by 14.9% and 17.0% for soybean, 14.0% and 14.1% for peanut, and 15.0% and 14.1% for rapeseed under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8d–f).

During the period of 2021–2060, compared to the non-expansion situation (when planting area stays the same as in 2014), reasonably expanding the planting area for oil crops would improve the soybean, peanut, and rapeseed production by about 7.0, 0.9, and 6.1 Mt, respectively. Under the expansion scenario, production would reach 17.9 and 17.5 Mt for soybean, 12.6 and 12.4 Mt for peanut, and 18.1 and 18.0 Mt for rapeseed under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, respectively. However, if the expansion plan was retrospectively applied to the historical period of 1981–2014, soybean, peanut, and rapeseed production could have reached 19.3, 13.5, and 19.4 Mt, respectively (Fig. 4a–c). During the growing seasons for soybean and peanut, the projected frequencies of compound extreme heat-drought, extreme heat, and drought under SSP1-2.6 (SSP5-8.5) are 37.4%, 22.5%, and 7.5% (45.0%, 32.5%, and 7.5%) and 42.5%, 5.0%, and 7.5% (60.0%, 15.0%, and 10.0%), respectively. During the growing season for rapeseed, the frequencies of compound extreme heat and drought (drought) would be 35.0 and 40.0% (17.5 and 25.0%) under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Hypothetically, if the expansion of planting area for oil crops from 2021 to 2060 were applied to the historical period, the projected compound extreme heat and drought would reduce the oil crop production. Compared to the hypothetical historical production, the projected decrease under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 is 15.1% and 17.6% for soybean; 12.8% and 13.4% for peanut, and 14.7% and 14.6% for rapeseed (Fig. 4d–f).

Impacts of temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought on EVO production

From 1981 to 2014, the national EVO production averaged 6.8 Mt. If the planning area for oil crops were kept as the level in 2014 for the future period of 2021–2060, the national EVO production would be reduced to 6.4 Mt and 6.3 Mt under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9a). For the three oil crops, the composite frequencies of compound extreme heat and drought, extreme heat, and drought would be 50.0%, 20.0%, and 0% (50.0%, 22.5%, and 12.5%) under SSP1-2.6 (SSP5-8.5), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9c). From 1981 to 2014, the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO averaged 26.7% (Fig. 1). In the non-expansion situation, the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO for the period of 2021–2060 would average 17.2% (ranging from 16.7 to 17.8%) in normal years and 15.9% (ranging from 15.5 to 16.5%) in years with compound extreme heat and drought.

Hypothetically, if the expansion of planting area for oil crops for the period of 2021–2060 were applied to the period of 1981–2014, the national EVO production could have been 9.0 Mt (which is 2.2 Mt higher than the actual value). In the expansion situation, the national EVO production for the period of 2021–2060 would be 8.4 Mt and 8.3 Mt under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 respectively (Fig. 5a). With the 10% threshold of reduction in national production of EVO (Fig. 5c), the composite frequencies of compound extreme heat and drought, extreme heat, and drought for the three oil crops would be 40.0, 20.0, and 7.5% (42.5, 25.0, and 0%) under SSP1-2.6 (SSP5-8.5), respectively. For the period of 2021–2060, the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO in the expansion situation would be decreased compared to the average from 1981 to 2014. In normal years, the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO would average 22.9% (ranging from 22.1 to 23.9%) under the two SSPs. In years with the compound extreme heat and drought, the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO would average 21.2% (ranging from 20.5 to 21.9%) under SSP1-2.6 and 20.9% (ranging from 19.0 to 21.9%) under SSP5-8.5.

Discussion

In this study, we built a panel regression model based on the collected climate, oil crops, and irrigation data. Then we used the model to quantify the impacts of changes in extreme heat and drought indices on oil crop yields as well as to project the oil crop yields for the future in China. The model integrates multidimensional data across temporal and spatial dimensions, enabling simultaneous analysis of temporal dynamics and individual heterogeneity29. Specifically, the model can directly estimate individual fixed effects to account for unobserved heterogeneity across entities30. Large panel data of this study perform well in assessing how crop yield responds to HDD, SPEI, and their interactions under irrigated conditions11. Compared with process-based models, both approaches could quantify yield-climate relationships, elucidate crop responses to management practices and climatic factors, and utilize these relationships to develop predictive models for future crop yields31. However, the panel model employed in this study eliminates the need for field-level production and management data during model calibration and evaluation29,30. Moreover, it is particularly suitable for broader spatiotemporal scales, facilitating the assessment of regional climate change impacts on crop yields31.

Historical analysis showed that changes in HDD and SPEI decreased oil crop yields by 4.5% to 7.1%, and HDD had a more negative impact on oil crop yields than SPEI did (Supplementary Fig. 4). In most soybean- and peanut-growing locations, HDD was below 20 °C day, while in most rapeseed-growing locations, HDD was below 5 °C day. The less severe the extreme heat was, the smaller negative impact it had on oil crop yields32. Compared with soybeans, peanut has a relatively lower water footprint per unit product and therefore lower sensitivity to changes in SPEI33,34. However, the overall negative impact of SPEI was greater on the yield of peanut (5.8%) than soybean (3.2%). This is because peanut is mostly grown in the North China Plain, and soybean is mostly grown in Northeast China, and crop water stress is generally worse in the former than in the latter35,36,37. By contrast, crop water stress for rapeseed was mostly low, with an exception in the southwestern part of Southwest China35. Among the three oil crops, the negative impact of SPEI was the smallest on rapeseed.

With proper irrigation, the negative impacts of HDD (SPEI) on the yields of soybean, peanut, and rapeseed could have been mitigated by 42.3%, 46.2%, and 28.6% (53.1%, 44.8%, and 41.7%), respectively (Figs. 2 and 3). And these results are consistent with the findings previously reported in other related studies10,38. Irrigation helps to increase the soil moisture and enhances evaporative cooling. And also helps crop plants to grow more leaf area and biomass than rainfed condition does, which leads to higher crop transpiration39. When crop water stress is induced by drought, irrigation is the most effective measure to combat the negative impact of drought on crop yields10. However, once the ratio of effective irrigation area reached a certain point, the marginal crop yield gain with increasing irrigation started to drop. In other words, the negative impact of drought on crop yields could not fully offset by irrigation40. Under the future climate scenarios, HDD showed a statistically significant increase, and the negative impact of HDD on oil crop yields would worsen by 4.6% given irrigation was kept at the current level41,42. In the North China Plain and Northeast China, where soybean and peanut production is concentrated, drought would become even more frequent in the future, and the negative impact of SPEI on oil crop yields would aggravate by over 1.7%43,44,45.

In this study, we assessed the impacts of extreme heat, drought, and compound events on oil crop yields at a city-scale, whereas extreme climate events usually occur at a regional scale. It was reported that regional warming may not necessarily lead to drought, but when it does, it would cause rapidly developing and long-lasting (e.g., a year) drought46, which would result in substantial crop yield loss47. Therefore, it is critical to understand how extreme climate events affect the self-sufficiency rate of EVO from both spatial and temporal perspectives16. In the analyses, we categorized the study years into four types: normal, temporal-spatial extreme heat, temporal-spatial drought, and temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought. Climate extreme events are not parallel to the impacts they pose on crop yields48, and simply using climatic indices to define the years is not enough for an agricultural impact report17,20,49. Hence, we used the 10% threshold of oil crop yield reduction rate to identify the extreme heat and drought years27,50. Under the future climate scenario, the increasing temperature will make extreme heat more intense and frequent, and the more fluctuating annual precipitation will make drought more frequent20,44. As a result, oil crop yields were projected to decrease by up to 27% in the future in China, and the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO was expected to drop from about 30% (the historical level) to 15.5–16.5% under the relatively worse scenario. By appropriately expanding the growing area for oil crops, the national self-sufficiency rate of EVO would be expected to be slightly improved to 19.0–23.9%, even in temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought years. In order to offset more of the negative impact of compound extreme heat and drought, other measures should be taken as well. Such measures include but are not limited to: optimizing sowing window51,52, tailoring management practices based on local situations53,54,55,56, advancing breeding technology, enhancing soil quality, and improving irrigation efficiency (i.e., amount, timing, and method).

Inevitably, our study has some limitations. First, soybean, peanut, and rapeseed are all C3 crops, but we did not consider the potential mitigation from enhanced atmospheric CO2 concentration to extreme heat and drought10,57. Second, extreme heat and drought were identified by defining thresholds for temperature and SPEI during the crop growing season, without differentiating the impacts of different intensity levels of these extremes. Third, besides crop yield, climate change also leads to changes in oil extraction rate, and the percentage of pressing amount demonstrates inter-annual variability. However, due to data limitations, this study did not account for these changes. But further discussion about climate-smart agriculture for oil crops would be highly recommended in future studies. Last, besides increasing the domestic oil crops yields, importing (or international trading) could be another way to solve the low self-sufficiency rate problem, which was not included in the analyses. Hence, we would suggest future scholars to incorporate an economic model that factors in population, price, etc., to provide a more thorough multidisciplinary report.

Methods

Research area and data

In this study, we focused on the main growing areas for the three oil crops of soybean, peanut, and rapeseed in China. Over 85% of the national oil crops planting area is concentrated in 339, 285, and 210 cities for soybean, peanut, and rapeseed, respectively. Because spring rapeseed planting area accounts for less than 10% of the total rapeseed planting area, we only addressed winter rapeseed in the analyses58.

Climate data of historical (1981–2014) and future (2021–2060, SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5) were retrieved from the Intersectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISI-MIP, https://data.isimip.org/search/). Including daily near-surface maximum and minimum air temperatures, precipitation, solar radiation, wind speed, and relative humidity from the output of GFDL-ESM4 with a revolution of 0.5°. The data had much improved climate mean patterns and variability compared with previous models. Both historical and future climate data were interpolated into the study cities with the inverse distance weighting option in ArcGIS9.

The city-level annual crop data from 1981 to 2018 were collected from Socio-economic Development Statistical Database (https://data.cnki.net/v3/), including oil crop yield (kg/ha), oil crop planting area (ha), total crop planting area (ha), and effective irrigation area (ha). For the soybean-growing cities, we also collected the yield (kg/ha) and planting area (ha) for maize; and for the rapeseed-growing cities, we also collected the planting area (ha) for winter wheat. The average sowing and harvesting dates for the study crops were acquired from the SAGE datasets (http://www.sage.wisc.edu). The EVO production and demand from 2000 to 2020 were referred to the U.S. Department of Agriculture website and previous related studies5,59.

Extreme climatic indices calculation

We chose heat degree days (HDD, °C day) to assess the extreme heat60, and the upper threshold of maximum air temperature was set to 33, 35, and 29.5 °C for soybean, peanut and rapeseed, respectively61,62,63. In order to capture the year-by-year moisture characteristics during crop growing season, we selected the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) in this study because it can evaluate the duration and intensity of drought at a regional scale28,64 and for different time scales (e.g., one, three, six, and twelve months)43. In this study, the time scale of SPEI is the actual crop growing season (months from sowing to maturity). Based on the precipitation and temperature data, we used the R program to compute SPEI during the actual growing months for the oil crops65. The SPEI follows a standardized normal distribution (with mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1), where SPEI below −0.5 corresponds to approximately the 30th cumulative percentile, which indicates that the moisture condition during the given growing months was drier than 70% of the study period66. Following previous studies, drought was identified when the SPEI of actual growing months was below −0.5 (SPEI ≤ −0.5)28,64,65.

Irrigation alleviates crop water stress and hence enhances evaporative cooling, which could partially mitigate the negative effects of drought and extreme heat on crop yields and represent a critical component of agricultural disaster prevention and mitigation capacity39. Therefore, we factored in the annual percentage of effective irrigation area (Irri, %) for the study cities, which is the percentage of effective irrigation area (ha) to total planting area (ha).

Panel model construction and historical impacts analysis

Panel regression analysis is known for being suitable for climate change impact studies67. Therefore, we used a fixed effects panel regression model to quantify the impacts of HDD, SPEI, and Irri on oil crops yields (Eq. 1).

Where i represents the i-th city; t represents the t-th year; Yi,t is the crop yield at city i in year t; α0 is the common intercept for all study cities; α1,…, α7 are the crop yield sensitivity parameters to HDD, SPEI, HDD & SPEI and the interaction between those above with Irri, respectively; (t, t2) is a set of city-specific quadratic trends in crop yield due to improved agricultural management practices and advanced technology; Cityi corresponds to the fixed effects at a city level (i.e., an independent intercept for each city); and ɛi,t is the residual error. For the non-irrigation situation, Irri is 0, and t represents year 1981–1985.

In order to quantify the impacts of HDD or SPEI changes on oil crops yield, we set a baseline of 1981–1985 to compute the yield change corresponding to changes in HDD and SPEI from 1981 to 2014 (Eq. 2). Such as when we want to quantify the impacts of HDD changes on oil crops yield, we inputted HDD from 1981 to 2014 while SPEI, Irri and t remain at the baseline level from 1981 to 1985 into the constructed panel regression model. Then we could get the yield only with historical HDD changes. By multiplying the crop yield with planting area, we derived the impacts of HDD and SPEI on oil crop production and hence EVO production.

Where Yieldbase is the average yield during the baseline period of 1981–1985, kg/ha; i represents the study climatic index, HDD, SPEI and HDD and SPEI; and Yieldi is the corresponding yield for changing factor i, kg/ha. For example, YieldHDD is the yield with changing HDD from 1981 to 2014, while SPEI, Irri and t remain at the baseline level from 1981 to 1985.

Future crops yield, planting area and EVO production projection

-

(i)

Crops yield projection. Under the two future climate scenarios of SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, we used Eq. (1) to project oil crop yields for the period of 2021–2060 by assuming Irri and t remain at the level in 2014. Then we selected the historical period (1981–2014) as the baseline to quantify the impacts of future extreme heat, drought, and compound events on oil crop yields using Eq. (2).

-

(ii)

Crops planting area projection. As to the future planting area for oil crops, we hypothesized two situations: (a) remain the same as in 2014; and (b) expand to the extent that the Chinese government supports. The China Agricultural Outlook Committee mentions that the demand for EVO is expected to reach 38.0 Mt by 2031. They also aim to expand the future planting area for soybean, peanut, and rapeseed to 13.3, 8.8, and 5.0 Mha, respectively68,69. Therefore, in this study, we further project the potential expansion of crop planting areas in future.

Based on the city ranking of maize yield in Central China and South China, the bottom ranked cities will appropriate 75% of the planting area for maize to promote the maize-soybean intercropping until the soybean expansion goal is met70. By referring to the established ecological sub-regions in the soybean-growing region, we retrieved the percentage of intercropped soybean yield to monocropping soybean yield for the study cities from previous related studies28,66,71,72,73,74. With the projected soybean yield, the above-mentioned percentage and the planting area for intercropped soybean, we computed the soybean production in the maize-soybean intercropping system69.

For the rapeseed-growing cities, we calculated the winter fallow field area as the difference between the total cropping area and the subtotal planning area for rapeseed and winter wheat. Based on the city ranking of rapeseed yield, the top-ranked cities will use 75% of the winter fallow field to grow more rapeseed until the expansion goal is met. For peanuts, we rank the cities based on peanut yield, and starting from the city with highest yield, the future peanut area expands by 75% of 2014 (resulting in an expanded area of 175% of the original) until the national area reaches 5.0 Mha70. Meanwhile, the EVO demand of 2031 would reach 38.0%68.

(iii) EVO production projection. Based on crop yield and planting area, we calculated the oil crop production changes. Also, we calculated the EVO production based on the oil crops productions, national percentage of pressing amount (which is 27%, 47%, and 90% for soybean, peanut, and rapeseed, respectively), and oil extraction rate (which is 16.5%, 35.0%, and 34.0% for soybean, peanut, and rapeseed, respectively)5.

Defines of temporal-spatial compound extreme climate

Occurring of extreme heat and drought during crop growth periods would directly lead yield decreasing. The frequency and intensity of above extreme events vary spatially across different planting regions, leading to differential crop exposure and directly affecting national oil crops and EVO production. Therefore, the most direct manifestation of extreme weather impacts on national oil crops is reflected in changes in total production. In this study, according to the crop production and EVO production changes (both historical and future projected) as compared to the baseline level, we used the 10% threshold of production reduction rate to identify the extreme heat and drought years27. In a given year, if changes in HDD (SPEI) lead to a 10% production reduction in any oil crop production, this particular year would be deemed a temporal-spatial extreme heat (drought) year for the oil crop(s). In years when changes in HDD and SPEI both lead to a 10% production reduction in oil crop, such years would be considered as temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought years. In this way, we categorized the study years into four types: normal, temporal-spatial extreme heat, temporal-spatial drought, and temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all data analyzed during this research are included in this manuscript.

Code availability

All code used in this research is available from the corresponding author by request.

References

Sheng, Y. & Song, L. Agricultural production and food consumption in China: a long-term projection. China Econ. Rev. 53, 15–29 (2019).

Ahmad, T. et al. Utilization of wastewater from edible oil industry, turning waste into valuable products: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 99, 21–33 (2020).

Bai, Y. et al. Environmental sustainability challenges of China’s edible vegetable oil industry: from farm to factory. Resour. Conserv. Recycling. 170, 105606 (2021).

Yang, T. & Zheng, Y. State and trends of oil crops production in China. Ocl 23, D603 (2016).

Zhang, J., Benbo, X. & Zheng, J. Analysis on consumption changes and reform countermeasures of edible vegetable oil in China. China Oils Fats. 47, 5–10 (2022).

IPCC. Summary For Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Lee H. & Romero J. (eds.) (IPCC. Geneva, Switzerland, 2023).

Qiao, L. et al. Soil quality both increases crop production and improves resilience to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 574–580 (2022).

Ray, D. K. et al. Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat. Commun. 6, 5989 (2015).

Vogel, E. et al. The effects of climate extremes on global agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 54010 (2019).

Luan, X., Bommarco, R., Scaini, A., Vico, G. & Sveriges, L. Combined heat and drought suppress rainfed maize and soybean yields and modify irrigation benefits in the USA. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 64023 (2021).

Schauberger, B. et al. Consistent negative response of US crops to high temperatures in observations and crop models. Nat. Commun. 8, 13931 (2017).

Lu, J., Carbone, G. J., Huang, X., Lackstrom, K. & Gao, P. Mapping the sensitivity of agriculture to drought and estimating the effect of irrigation in the United States, 1950–2016. Agric. Meteorol. 292-293, 108124 (2020).

Daryanto, S., Wang, L. & Jacinthe, P. Global synthesis of drought effects on maize and wheat production. PLoS ONE 11, e156362 (2016).

Feng, S., Hao, Z., Zhang, X. & Hao, F. Probabilistic evaluation of the impact of compound dry-hot events on global maize yields. Sci. Total Environ. 689, 1228–1234 (2019).

Zhang, C., Gao, J., Liu, L. & Wu, S. Compound drought and hot stresses projected to be key constraints on maize production in Northeast China under future climate. Comput. Electron. Agric. 218, 108688 (2024).

Sarhadi, A. et al. Multidimensional risk in a nonstationary climate: joint probability of increasingly severe warm and dry conditions. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau3487 (2018).

Yin, J. et al. Future socio-ecosystem productivity threatened by compound drought–heatwave events. Nat. Sustain. 6, 259–272 (2023).

Guo, Y. et al. Quantifying hazard of drought and heat compound extreme events during maize (Zea mays L.) growing season using Magnitude Index and Copula. Weather Clim. Extrem 40, 100566 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Quantifying high-temperature and drought stress effects on soybean growth and yield in the western guanzhong plain. Atmosphere 15, 392 (2024).

Lesk, C. & Anderson, W. Decadal variability modulates trends in concurrent heat and drought over global croplands. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 55024 (2021).

Ting, M. et al. Contrasting impacts of dry versus humid heat on US corn and soybean yields. Sci. Rep. 13, 710 (2023).

Couëdel, A. et al. Assessing environment types for maize, soybean, and wheat in the United States as determined by spatio-temporal variation in drought and heat stress. Agric. Meteorol. 307, 108513 (2021).

Chu, Y., Shen, Y. & Yuan, Z. Water footprint of crop production for different crop structures in the Hebei southern plain, North China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 3061–3069 (2017).

Zhao, J. et al. Assessing variation and driving factors of the county-scale water footprint for soybean production in China. Agric. Water Manag. 263, 107469 (2022).

Zhao, J., Yang, X. & Sun, S. Constraints on maize yield and yield stability in the main cropping regions in China. Eur. J. Agron. 99, 106–115 (2018).

Yan, Z. et al. Assessment of the sustainability of different cropping systems under three irrigation strategies in the North China Plain under climate change. Agric. Syst. 178, 102745 (2020).

Song, Q. et al. Effect of straw retention on carbon footprint under different cropping sequences in Northeast China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 54792–54801 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Can China get out of soy dilemma? A yield gap analysis of soybean in China. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 43, 47 (2023).

Qi, F. et al. Enhanced spatiotemporal prediction of rainfall erosivity through flood season data integration. Catena 259, 109369 (2025).

Irene, B. et al. Identification of time-varying transformation models with fixed effects, with an application to unobserved heterogeneity in resource shares. J. Econ. 232, 576–597 (2023).

Elena, K. et al. Estimating unobserved individual heterogeneity using pairwise comparisons. J. Econ. 226, 477–497 (2022).

Yang, W., Parsons, D. & Mao, X. Exploring limiting factors for maize growth in Northeast China and potential coping strategies. Irrig. Sci. 41, 321–335 (2023).

Vogel, E. et al. The effects of climate extremes on global agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 054010 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Quantifying irrigation cooling benefits to maize yield in the US Midwest. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 3065–3078 (2020).

Agnolucci, P. et al. Impacts of rising temperatures and farm management practices on global yields of 18 crops. Nat. Food 1, 562–571 (2020).

Sun, Q. et al. Heat stress may cause a significant reduction of rice yield in China under future climate scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 818, 151746 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Climate-associated major food crops production change under multi-scenario in China. Sci. Total Environ. 811, 151393 (2022).

Zhu, X., Liu, T., Xu, K. & Chen, C. The impact of high temperature and drought stress on the yield of major staple crops in northern China. J. Environ. Manag. 314, 115092 (2022).

Yu, C. et al. Assessing the impacts of extreme agricultural droughts in china under climate and socioeconomic Changes. Earth’s. Future 6, 689–703 (2018).

Guo, E. et al. Assessing spatiotemporal variation of drought and its impact on maize yield in Northeast China. J. Hydrol. 553, 231–247 (2017).

Trenberth, K. E. et al. Global warming and changes in drought. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 17–22 (2014).

Mazdiyasni, O. & AghaKouchak, A. Substantial increase in concurrent droughts and heatwaves in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 11484–11489 (2015).

Leonard, M. et al. A compound event framework for understanding extreme impacts. WIREs Clim. Change 5, 113–128 (2014).

Singh, J. et al. Enhanced risk of concurrent regional droughts with increased ENSO variability and warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 163–170 (2022).

Shi, W., Wang, M. & Liu, Y. Crop yield and production responses to climate disasters in China. Sci. Total Environ. 750, 141147 (2021).

Shi, W. & Tao, F. Spatio-temporal distributions of climate disasters and the response of wheat yields in China from 1983 to 2008. Nat. Hazards 74, 569–583 (2014).

He, L., Jin, N. & Yu, Q. Impacts of climate change and crop management practices on soybean phenology changes in China. Sci. Total Environ. 707, 135638 (2020).

Liu, Y. & Dai, L. Modelling the impacts of climate change and crop management measures on soybean phenology in China. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121271 (2020).

Li, C., Li, X., Kong, W., Wu, Y. & Wang, J. Effect of monoculture soybean on soil microbial community in the Northeast China. Plant Soil. 330, 423–433 (2010).

Zhang, S. et al. Maize/soybean intercropping improves stability of soil aggregates driven by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in a black soil of northeast China. Plant Soil. 481, 63–82 (2022).

Wu, A., Hammer, G. L., Doherty, A., von Caemmerer, S. & Farquhar, G. D. Quantifying impacts of enhancing photosynthesis on crop yield. Nat. Plants 5, 380–388 (2019).

NBSC. China Statistics Yearbook (China Statistics Press, 2022).

Guo, S. et al. Historical and projected impacts of climate change and technology on soybean yield in China. Agric. Syst. 203, 103522 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Present situation of edible vegetable oil supply in China and its future development strategy. China Oils Fats. 47, 1–8 (2022).

Tigchelaar, M., Battisti, D. S., Naylor, R. L. & Ray, D. K. Future warming increases probability of globally synchronized maize production shocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 6644–6649 (2018).

Ketring, D. L. Temperature effects on vegetative and reproductive development of peanut. Crop Sci. 5, 877–882 (1984).

Qian, B. et al. Simulated canola yield responses to climate change and adaptation in Canada. Agron. J. 110, 133–146 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Advances and perspectives in research of physiological and molecular mechanism of soybean response to high temperature stress. Sci. Agric. Sin. 50, 2670–2682 (2017).

Potopová, V., Štěpánek, P., Možný, M., Türkott, L. & Soukup, J. Performance of the standardised precipitation evapotranspiration index at various lags for agricultural drought risk assessment in the Czech Republic. Agric. Meteorol. 202, 26–38 (2015).

Yao, N. et al. Response of wheat and maize growth-yields to meteorological and agricultural droughts based on standardized precipitation evapotranspiration indexes and soil moisture deficit indexes. Agric. Water Manag. 266, 107566 (2022).

Zhang, Q. & Hu, Z. Assessment of drought during corn growing season in Northeast China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 133, 1315–1321 (2018).

Salehnia, N., Salehnia, N., Saradari Torshizi, A. & Kolsoumi, S. Rainfed wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) yield prediction using economical, meteorological, and drought indicators through pooled panel data and statistical downscaling. Ecol. Indic. 111, 105991 (2020).

CAOC. China Agriculture Outlook Report (2022–2031) (China Agricultural Science and Technology Press, 2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Optimization of China’s maize and soy production can ensure feed sufficiency at lower nitrogen and carbon footprints. Nat. Food 2, 426–433 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Soybean yield variations and the potential of intercropping to increase production in China. Field Crops Res. 291, 108771 (2023).

Laimighofer, J. & Laaha, G. How standard are standardized drought indices? Uncertainty components for the SPI & SPEI case. J. Hydrol 613, 128385 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. In search of long-term sustainable tillage and straw mulching practices for a maize-winter wheat-soybean rotation system in the Loess Plateau of China. Field Crops Res. 217, 199–210 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Relationships among light distribution, radiation use efficiency and land equivalent ratio in maize-soybean strip intercropping. Field Crops Res. 224, 91–101 (2018).

Rahman, T. et al. Water use efficiency and water distribution response to different planting patterns in maize—soybean relay strip intercropping systems. Exp. Agric. 53, 159–177 (2017).

Yang, F. et al. Effect of narrow-row planting patterns on crop competitive and economic advantage in maize-soybean relay strip intercropping system. Plant Prod. Sci. 20, 1–11 (2017).

Yang, F. et al. Yield response to different planting geometries in maize–soybean relay strip intercropping systems. Agron. J. 107, 296–304 (2015).

Shao, Z. et al. Spatial-temporal large models: a super hub linking multiple scientific areas with artificial intelligence. Innovation 6, 100763 (2025).

Mannering, F. et al. Unobserved heterogeneity and the statistical analysis of highway accident data. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 11, 1–16 (2016).

Schauberger, B. et al. Consistent negative response of US crops to high temperatures in observations and crop models. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–9 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFD2301300), Hebei Natural Science Foundation (C2025304001) and the 2115 Talent Development Program of China Agricultural University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. and X.Y.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. Z.L.: methodology, data curation and writing—review and editing. C.Z.: methodology and writing—review and editing. J.Z. and Z.Z.: writing-review and editing. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, S., Zhao, C., Jin, Z. et al. Impacts of temporal-spatial compound extreme heat and drought on oil crops in China. npj Sustain. Agric. 4, 13 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00123-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00123-8