Abstract

During impression formation, perceptual cues facilitate social categorization while person-knowledge can promote individuation and enhance person memory. Although there is extensive literature on the cross-race recognition deficit, observed when racial ingroup faces are recognized more than outgroup faces, it is unclear whether a similar deficit exists when recalling individuating information about outgroup members. To better understand how perceived race can bias person memory, the present study examined how self-identified White perceivers’ interracial contact impacts learning of perceptual cues and person-knowledge about perceived Black and White others over five sessions of training. While person-knowledge facilitated face recognition accuracy for low-contact perceivers, face recognition accuracy did not differ for high-contact perceivers based on person-knowledge availability. The results indicate a bias towards better recall of ingroup person knowledge, which decreased for high-contact perceivers across the five-day training but simultaneously increased for low-contact perceivers. Overall, the elimination of racial bias in recall of person-knowledge among high-contact perceivers amid a persistent cross-race deficit in face recognition suggests that contact may have a greater impact on the recall of person-knowledge than on face recognition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Person perception in an increasingly diverse social landscape is impacted by a similarly varied set of physical attributes and person-knowledge that shape our impressions of others. The incorporation of digital spheres into our interactions simultaneously increases the availability of these perceptual and knowledge-based cues that inform our mental representations of others. The perceptual and knowledge-based cues we attend to structure how we retrieve and reconstruct information about others1, shaping future interactions we may have with those individuals. In many contemporary studies, where perceptual cues are the only available information to guide impressions, perceived group membership, particularly race, has been shown to shape person memory through preferential recognition of ingroup members2. However, despite ample evidence of racial bias in face recognition when impressions are formed based solely on perceptual cues, there is substantially less work focused on comparing how both perceptual and knowledge-based cues contribute to person memory about racial ingroup and outgroup others and even less about how perceiver experiences shape these processes. To bridge this gap, the current paper investigates how perceived race impacts the learning of faces and person-knowledge about others over multiple sessions among perceivers varying in prior interracial contact.

Impression formation based on perceptual cues can be adaptive. Physical cues are widely accessible and allow for rapid assessment of our environment by retrieving pertinent representations while conserving elaborative cognitive resources3,4,5. These quick and efficient impressions are guided by social cues conveying traits like trustworthiness6,7,8, dominance9, competence, or warmth8,10,11. Perceptual cues additionally facilitate social categorization3,4,5,12,13,14 based on group membership, such as perceived gender12,15, age16,17, and race18,19. Categorization based on perceptual cues can elicit social expectations20,21 and influence impressions even in the absence of person-knowledge22,23,24. The category-level impressions we form using even minimal perceptual information have implications for face recognition. For example, individuals categorized as belonging to the perceiver’s ingroup are more likely to be recognized2,25,26. However, whereas most work has focused on single-shot interactions, less is known about the dynamic changes in person memory over multiple exposures, especially as knowledge-based cues are learned and supplement perceptual information eliciting social categorization. As many social interactions involve getting to know someone over time, it is important to understand how we learn about people over repeated interactions.

Forming impressions of individuals based on group membership, as opposed to more idiosyncratic characteristics, may lead to poor face recognition, particularly for outgroup members4,14. When available, knowledge-based cues may override or reshape initial impressions based on perceptual cues4,27,28. These cues, including specific information we have about individuals’ past behaviors, beliefs, goals, etc. (i.e., person-knowledge) can promote individuation by considering others in terms of their distinctive characteristics and behaviors rather than their perceived category-level memberships3,4,12,14,29. Relative to impressions based on perceptual cues alone, impressions formed with individuating person-knowledge are more complex and contribute to enhanced person memory4,27,28,29,30. The processing goals and motivations of perceivers (e.g., anticipation of future interactions with an individual, instructions to form an accurate impression) may increase attention to distinguishing attributes, leading to improved face recognition and recall of individuating information3,4,31,32,33. For example, prompting perceivers to form more individuated impressions by making a trait inference during facial encoding improves later recognition memory relative to making only a perceptual judgment34,35,36. Notably, the recognition advantage conferred by the instructed inference of individuating information is observed for both own- and other-race faces37. In other words, even inferring simple forms of person-knowledge from faces promotes increased individuation and recognition memory irrespective of perceived social category membership. This also suggests that prerequisite attention to person-knowledge can be modulated by perceiver motivation.

Despite the facilitatory role of person-knowledge in face recognition memory, little is known about how it differs from the impact of perceptual familiarity and how the content of person-knowledge associated with faces is recalled. For example, models of person memory38,39 have outlined a potential structure by which the perceptual and knowledge-based information essential to the correct identification of others as familiar may be accessed, but these have limited predictive ability regarding the retrieval of specific person-knowledge once an individual has been established as familiar. These models posit that perceptual cues for an individual face are stored in a face recognition unit (FRU), which serves as an input to an associated person identity node (PIN) that is connected to semantic information units (SIUs) housing person-knowledge. Relevant to the current investigation, the interactive activation model39 predicts that a face is more likely to be recognized if it is semantically associated with person-knowledge due to increased activation resulting from excitatory links between the PIN and associated SIUs. The model also suggests that the recall of person-knowledge is dependent on a threshold level of activation for the SIU where the person-knowledge is stored, which can be hindered by inhibitory links among simultaneously activated SIUs. However, it is unclear what additional factors may impact whether or not any given SIU containing person-knowledge will reach threshold activation when an individual is encountered. Here we explore how face recognition and recall may be influenced by the valence of person-knowledge, the perceived race of others, and the perceiver’s interracial contact.

Although access to person-knowledge appears to facilitate person memory beyond the presence of perceptual cues, prior research demonstrating the impact of valence on memory suggests that not all person-knowledge reaps the same rewards. The existence of a negativity bias has been suggested, such that negative information is better remembered compared to positive information40,41,42,43. Therefore, perceivers may better recall negative, relative to positive, person-knowledge. Findings of improved recognition for faces perceived to display negative traits (e.g., untrustworthiness)44 suggest that this negativity bias may extend to face recognition29. However, memory for negative or positive person-knowledge may also vary based on who the information is associated with. For example, perceived violations of expectations have been shown to promote individuation and subsequent person memory4,45,46. Of interest to the current study is how valenced person-knowledge may shape memory for perceived racial ingroup and outgroup others due to potential violations of expectations based on affective associations stemming from race-based prejudices. Indeed, individuals associated with person-knowledge affectively incongruent with race-based prejudices could be individuated to a greater extent and thus recognized more. Although this pattern may also extend to recall, such that affectively incongruent person-knowledge is recalled more accurately, the valenced person-knowledge utilized in the current study is intentionally devoid of stereotype content, which may shape whether it is processed as aligning with or violating expectations. Further, little work has examined how perceivers recall the content of person-knowledge about others varying in perceived race47. This gap in knowledge is particularly surprising considering extensive documentation of cross-race bias in face recognition.

The cross-race recognition deficit (CRD), also referred to as the other-race effect, is the tendency to have better memory for racial ingroup faces compared to racial outgroup faces2,14,48,49,50,51,52,53. White individuals, for example, are typically better at remembering perceived White faces compared to perceived Black faces54. Ingroup perceptual expertise emerges in early development55,56,57 and has been found across multiple cultures56. Explanations of the CRD based on perceptual expertise characterize memory for faces as a skill that is continuously strengthened from infancy onward as we collect facial exemplars56,57,58. Consequently, the disproportionate number of own-race faces encountered compared to cross-race faces is believed to contribute to bolstered perceptual expertise and unique, more holistic processing of own-race faces, enhancing their recognition59,60,61,62. Furthermore, greater motivation has been postulated to increase individuation33,63,64,65,66,67, and perceivers tend to individuate racial ingroup members more compared to racial outgroup members25,50. However, while robust evidence of the cross-race recognition deficit is available, it is less clear how perceived race may shape the learning of person-knowledge about an individual, particularly over time. Would repeated exposure to person-knowledge about outgroup members be sufficient to eliminate racial biases in person memory?

The induction of the contact hypothesis68 ushered in a proliferation of studies exploring intergroup contact as an intervention to reduce prejudice. Interracial contact specifically has been associated with reduced racial bias in both explicit and implicit evaluations69,70,71,72,73. Interracial contact has also been connected to reduced racial bias in person perception and memory16,74,75. Two separate meta-analyses of substantial bodies of work on the topic suggest that interracial contact, in some contexts, decreases the cross-race recognition deficit51,52. These effects of interracial contact beyond prejudice reduction are aligned with the recent characterization of intergroup contact as a tool for cognitive liberalization76. This perspective suggests that intergroup contact, through requiring individuals to repeatedly counteract stereotypical expectations via individualized experience with outgroup others, can produce generalized changes in cognition such as increased cognitive flexibility and individuation76. Changes at earlier processing stages may also have potential downstream consequences for the reduction of prejudice71,77. For example, having increased person-knowledge about the outgroup was found to mediate the impact of contact on the reduction of prejudice77. Therefore, investigating broader impacts of intergroup contact on social cognition may advance knowledge about its potential as an intervention to reduce racial biases at multiple levels. The current study contributes to this ongoing expansion of intergroup contact research by testing whether prior interracial contact shapes distinct types of person memory for racial ingroup and outgroup others varying in the availability and valence of person-knowledge. Notably, examining how perceivers varying in prior interracial contact recall person-knowledge over multiple exposures allows us to explore if interracial contact reduces a potential racial bias in recall of person-knowledge.

To further explore how contact may be implemented as a potential intervention to reduce racial biases, the present study tests general face recognition ability before and after learning to explore whether learning about outgroup others over multiple exposures may promote improved cross-race person memory. Along these lines, existing work suggests that experimentally manipulated experience with cross-race faces can improve cross-race face recognition52,58,71. Studies employing training with cross-race faces have shown that training requiring perceivers to individuate cross-race faces by associating them with a unique letter or name improves the perceptual discrimination of novel cross-race faces post-training71,78. These studies therefore suggest that even experimentally induced individuated experience with other-race faces can improve cross-race face recognition. In the current study, we expand upon the existing literature to investigate whether pairing faces with person-knowledge, in contrast to perceptual individuation, can similarly improve general cross-race face recognition post-training.

To better understand how perceived race can bias person memory, the present study examines how interracial contact impacts the learning of faces and person-knowledge about racial ingroup and outgroup individuals over multiple sessions. Additionally, an independent face recognition task before and after the training period is used to explore whether learning about racial ingroup and outgroup faces improves general memory for faces differentially based on contact. This study is, to our knowledge, the first to investigate potential race-based biases in the recall of person-knowledge about others over multiple exposures and how contact may shape these biases. Based on the previously observed improvement of cross-race face recognition associated with increased interracial contact, high-contact perceivers should display reduced racial biases in face recognition and learning of person-knowledge relative to low-contact perceivers. However, it remains to be seen how multiple exposures to others may shape these potential memory biases across perceivers.

Methods

Study overview

In this study, we examined how perceiver interracial contact impacts face recognition and learning of individuating information for others varying in perceived race. Participants were trained over five sessions to recognize perceived Black and White male faces who were either perceptually familiar only (i.e., no paired person-knowledge), paired with positive person-knowledge, or paired with negative person-knowledge. The inclusion of perceptually familiar faces for whom perceivers did not learn person-knowledge served to control for perceptual individuation to assess the impact of positive and negative person-knowledge on person memory. Training also assessed learning of paired person-knowledge by requiring participants to indicate the valence (i.e., valence attribution) and recall the content (i.e., cued recall) of person-knowledge statements. Additionally, before the first and following the last session of training, participants completed an exploratory independent face recognition task with novel stimuli to explore how training to individuate faces generalizes to recognition of newly encountered faces.

For our confirmatory predictions, we hypothesized that self-identified White participants would display increased learning for perceived White compared to perceived Black faces. Importantly, we predicted that this race-based bias would not only occur for face recognition, as previously extensively documented by literature on the CRD, but also for valence attribution and cued recall of person-knowledge. Furthermore, we expected perceivers to show a preferential learning rate in face recognition for faces paired with person-knowledge compared with faces that were only perceptually familiar29. In line with the negativity bias43, we predicted that perceivers would display increased learning across all three person memory indices for negative relative to positive face-statement pairs. However, we expected this effect to be modulated by perceived race. Specifically, based on findings of greater individuation for violations of affective expectations4, we expected increased learning (i.e., greater face recognition, valence attribution, and cued recall of person knowledge) for face-statement pairs affectively incongruent with race-based prejudices (i.e., perceived White faces with negative person-knowledge and perceived Black faces with positive person-knowledge). Because interracial contact has been found to reduce cross-race recognition bias, to improve individuation, and to be associated with efficiency in face processing51,52,79,80, we also predicted that perceivers with greater lifetime interracial contact would show reduced racial biases in face recognition, valence attribution, and cued recall of person-knowledge. As we anticipated a benefit of paired person-knowledge for all perceivers, we expected the impact of contact on racial bias in person memory to be similar across Information Type conditions. For example, perceivers with more interracial contact were expected to show similarly reduced differences in face recognition between perceived Black faces and perceived White faces regardless of whether faces were paired with person-knowledge at encoding.

Transparency and openness

All research was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of and study protocol approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board. In the following sections and Supplementary Material (referenced where necessary to keep the current paper concise), we report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures in the study.

The present study was preregistered at OSF on December 21, 2020, and the preregistered analysis plan was updated with a transparent changes document on February 5, 2021. While the current paper focuses on the confirmatory predictions, tasks, and analyses for this study (for a summary, see Supplementary Material, Table 2), the online preregistration reports all confirmatory and exploratory hypotheses, data collection procedures, and planned analyses81. The preregistration document also includes the materials used to collect individual difference measures, including the interracial contact questionnaire and calculations. Supplementary Material, Discussion 1 summarizes the full preregistered study design and highlights additional details of the preregistration relevant to the current paper. Also available at the study OSF page are the de-identified data and analysis script utilized for the current paper81.

Participants

A final sample of 70 undergraduate students (MAge = 18.69 years, SDAge = 0.941, 53 participants self-identified as women, 17 participants self-identified as men) successfully completed all five days of the study. This final sample was derived from a total of 182 participants initially recruited from the University of Delaware SONA pool. Informed consent was obtained from all recruited participants. All recruited participants self-identified as White and non-Hispanic, were between the ages of 18 and 35 years old, and had lived in the U.S. for at least 5 years. Of these participants, 112 were excluded from data analysis (34 who failed to participate in subsequent days or to complete a portion of a session, 46 who did not pass attention check criteria, 14 due to experimenter error (i.e., failure to administer the correct counterbalanced order of the experiment to which a participant was randomly assigned), 17 who failed to follow instructions (e.g., completed portions of the study multiple times), and 1 for computer technical difficulties). The final sample of 70 participants reported having more lifetime contact with White individuals compared to Black individuals as measured by a difference score of the composite measure for lifetime contact with Black individuals minus White individuals (Mlifetime contact = −53.345, SD = 20.889). Consistent with our preregistered inclusion criteria to obtain a sample across the contact distribution, 44.286% of the final sample (n = 31) reported having an average of at least 15% contact with Black individuals across the lifetime. Participants were compensated with credits toward the completion of research requirements for introductory courses.

Power analysis

The preregistration for this study includes the following a priori power analysis (https://osf.io/4k8ve/). To identify the necessary sample size, we conducted a power analysis using the PANGEA package (v0.2), publicly available at https://jakewestfall.shinyapps.io/pangea/82 with an alpha of 0.05. As this is the first study that explicitly examines combinations of perceived race and valence in a learning paradigm, the variance and effect size parameters were not possible to predict a priori. Therefore, we used the default variance parameters in PANGEA (var[error]=0.2, var[Person-knowledge Valence × Race × Session × Participant Contact] = 0.04).

Analyses modeled participants as a random factor nested within lifetime interracial contact (continuous variable), input as a categorical variable with 7 levels, and 8 analyzable trials per person-knowledge Valence (Positive, Negative) × Race (Black, White) × Session (1-5) × Participant Contact. Contact was operationalized as a categorical variable only for the implementation of the power analysis; for all subsequent analyses, contact was analyzed as a continuous variable. Power analyses suggested that a sample of 70 participants would be sufficiently powered to detect a significant Valence × Race × Session × Contact interaction at a small effect size (d = 0.20), 1–β = 0.8081.

Procedure

This online study consisted of five separate days of participation completed over six possible days. The extra day was allotted to allow flexibility and promote participant retention while maintaining a short learning period. Before the start of training, participants completed a pre-training independent face recognition task. On each of the five training days, participants completed one encoding phase and one test phase. On the fifth and final day of training, participants also completed a post-training independent face recognition task as well as individual difference measures, including the interracial contact questionnaire (see Supplementary Material, Discussion 1 for the full list of measures). All participants completed all conditions.

Stimuli

To equate the faces to be encoded throughout training, we obtained ratings for a set of approximately 750 perceived male facial photographs collected from various online face databases83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92. Prior to being rated, all faces were cropped around the hair and from the neck up, placed on white backgrounds, and greyscaled using Adobe Photoshop or Gimp. Images were also processed using the SHINE toolbox93 to remove low-level visual variation.

The modified photos were then rated in an independent sample of 740 Amazon Mechanical Turk participants such that each face had at least 30 ratings for each of the following equating criteria: perceived photo quality, age, race, attractiveness, distinctiveness, dominance, emotional expression, likability, and trustworthiness. Images were eliminated if (i) they had a mean photo quality rating of less than 3 on a scale of 1 (poor quality) to 7 (high quality), (ii) less than 80% of raters perceived the face to be either Black or White or (iii) less than 70% of raters responded that the face displayed either a happy or neutral expression. From the remaining 141 faces after these exclusions, we equated four groups of 16 faces for a total of 64 faces. The 8 perceived Black male faces and 8 perceived White male faces in each group were equated such that they were not rated significantly different from (i) the other faces in the group within their perceived race nor (ii) the group as a whole on any of the nine measured dimensions. Eight different random orderings were created from the four equated groups to be assigned to the information type conditions (i.e., perceptually familiar, positive person-knowledge, negative person-knowledge) for the encoding phase of training. The rated faces that were excluded throughout the equating process were utilized to develop novel distractor faces for the test phases of training. Novel distractor faces were equated only on perceived race (i.e., at least 80% rater consensus that the face was perceived to be Black or White) due to the large number of novel faces needed for five training sessions.

To convey valenced person-knowledge to be encoded throughout training, we developed a set of 48 positive and 48 negative statements from a database of sentences with available pilot data94. From this database, we identified a subset of statements that referred to individual male actors (e.g., “he”), described commonplace behaviors or characteristics, and were not rated to be highly stereotypical for gender or race. We equated 96 statements (48 positive, 48 negative) such that valence intensity, arousal, and race stereotypicality did not significantly differ by valence condition. The statements were randomly grouped into 16 groups containing 3 similarly valenced statements (i.e., 16 unique groups of three positive statements and 16 unique groups of three negative statements). The valenced statement groups were randomly paired with the 8 face orderings for the encoding phase of training so that each of the four equated face groups in an ordering was assigned to one of the following four conditions: faces paired with positive person-knowledge, faces paired with negative person-knowledge, perceptually familiar faces with no paired person-knowledge, and faces used for an evaluative priming task in a separate portion of the study, described in Supplementary Material, Discussion 1. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the 8 orderings to counterbalance training stimuli. For more information on the development and equating of the facial stimuli and person-knowledge statements, refer to Supplementary Material, Discussion 2.

The independent face recognition task included 76 perceived Black male faces and 76 perceived White male faces from the Chicago Face Database87 not included in any other part of the study. Faces in each perceived racial group were randomly divided into four categories for the following purposes: encoding faces for the pre-training recognition task, distractor faces for the pre-training recognition task, encoding faces for the post-training recognition task, and distractor faces for the post-training recognition task. Each category contained 38 faces including 19 perceived Black faces and 19 perceived White faces. Stimuli were cropped around the hair and from the neck up, placed on white backgrounds, and greyscaled using Adobe Photoshop or Gimp before being processed using the SHINE toolbox93 to remove low-level visual variation.

Training

The training component of this study was conducted online using Inquisit 5.0 Web (Millisecond Software, Seattle, Washington, USA) and consisted of five sessions, across six possible days, during which participants learned to recognize and recall individuating information about perceived Black and White male faces. On each day of training, participants completed an encoding phase with the same set of 48 unique faces and a test phase with these familiar faces plus 24 novel distractor faces. Sixteen faces (i.e., 8 perceived Black, 8 perceived White) were assigned to each of the following information type conditions: perceptually familiar, positive person-knowledge, and negative person-knowledge. At the start of each training session, participants were instructed that they would subsequently be tested on their memory for the faces and, when applicable, the specific statements they were paired with. Participants also completed 4 practice trials before each encoding phase and 7 practice trials before each test phase. Practice trials used faces not seen in the main experimental trials as examples of each type of stimulus a participant would see in the training. For example, before the encoding phase, participants completed practice trials for a face without person-knowledge, a face preceded by positive person-knowledge, a face preceded by negative person-knowledge, and an attention check trial face.

During the encoding phase (Fig. 1), each of the 48 unique faces was shown for 2000 ms six times for a total of 288 trials per encoding phase. In the positive and negative person-knowledge conditions, each face was paired with three unique statements of the same valence, and each unique face-statement pair was presented twice during each encoding session. Person-knowledge statements were shown for 2000 ms prior to the 2000 ms face presentation. After each face was shown, an ITI fixation cross was presented on the screen for 500 ms.

Participants completed one encoding phase with the same set of 48 unique faces each day for five days of training. Face images are used with permission from the Chicago Face Database87.

The test phase (Fig. 2) was completed immediately after the encoding phase, beginning with instructions and practice trials. Participants were then presented with a total of 72 faces, including all 48 familiar faces from the encoding phase and 24 novel faces (12 perceived Black, 12 perceived White). The test phase included three possible response components: (1) Face Recognition, (2) Valence Attribution, and (3) Cued Recall of Person-knowledge. On each trial, participants were asked (1) if the depicted face was familiar or novel. If a face was correctly recognized as familiar, participants were then asked (2) to recall what type of information (i.e., positive, negative, none) was paired with the face. If they correctly identified the valence of the information, they were then asked (3) to list up to three pieces of information that were previously paired with the face. Correct identification of a novel or perceptually familiar only face and incorrect responses led to the initiation of the next trial.

Participants completed one test phase with the 48 familiar encoded faces and 24 novel distractor faces each day for five days of training. Face images are used with permission from the Chicago Face Database87.

To ensure that participants paid attention to the training, 28 attention check trials were included in the encoding phase (~10% of 288 trials = 28.8) and 8 attention check trials were included in the test phase (10% of 72 trials = 7.2 rounded up). In each attention check, one of 4 faces (2 perceived Black, 2 perceived White) was shown for 2 s with a number in red text transposed over the forehead. Participants were asked to input the number as their response within two seconds. Participants were required to correctly answer 75 percent of attention checks in each phase of training (21 during the encoding phase; 6 during the test phase) to be included in analyses.

Independent face recognition task

On the first and last day of training, participants completed an exploratory independent face recognition task designed to assess the potential generalization of individuation training to racial bias in broader face recognition. In the pre- and post-training sessions of the independent face recognition task, participants were instructed to remember a series of faces not included elsewhere in the study for later recognition. During encoding, participants were randomly presented with 38 newly encountered faces (19 perceived Black, 19 perceived White) for 2 s each with an ITI of 250 ms. In the subsequent test, participants were randomly presented with 76 faces, including the 38 familiar faces previously seen during encoding and 38 novel distractor faces (19 perceived Black, 19 perceived White). Participants were instructed to distinguish between familiar and novel faces by pressing the “m” and “n” keys. Response keys were counterbalanced across participants. Each face was presented until the participant responded, followed by an ITI of 250 ms.

Interracial contact questionnaire

In a multi-item questionnaire to assess interracial contact across the lifespan, participants were asked to report the racial diversity of their social networks at three distinct stages of childhood and their current age16. Items asked about the percentage of friends, acquaintances, daily contacts, and media figures belonging to the following racial and ethnic groups: Asian, White, Black, Latinx, and Other. For each category, participants entered values ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating that 0% of the participant’s contact was with that racial group and 100 indicating that 100% of the participant’s contact was with that racial group. The measure also assesses the kind of environment in which participants have spent most of their lives (i.e., urban, suburban, or rural) and their awareness of their environment’s racial and cultural diversity.

To assess the internal consistency of the interracial contact questionnaire, Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated using the ltm package95 in R96 for all questions (29), including all three childhood phases and the current age. Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated separately for each of the following inputs to ensure reliability across all responses relevant to the current analyses: contact estimates for Black individuals only, contact estimates for White individuals only, and difference scores of these estimates (Black minus White). These three independent calculations yielded Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient values of 0.956, 0.963, and 0.963 respectively, indicating high reliability in participants’ contact estimates.

As in previous research from our lab65,80,97, lifetime interracial contact was calculated by creating an average of childhood contact and current contact with Black and White people. Childhood and current contact scores were calculated by averaging all questions for Black people and White people and then obtaining the difference between the two averages (Black minus White). Therefore, each participant had a childhood contact score and a current contact score that ranged from -100 (exclusively White contact) to +100 (exclusively Black contact). To obtain the composite measure of lifetime interracial contact, the childhood and current contact scores were averaged ([childhood contact score + current contact score]/2) and z-scored to be used as a continuous predictor in our models. Descriptive statistics for lifetime interracial contact scores may be reviewed in Supplementary Material, Discussion 5.1.

Data exclusion

Based on our a priori preregistered exclusion criteria, participants were excluded from analyses for: (i) failure to pass both the main experiment encoding phase and test phase attention check trials during the five training sessions (i.e., failure to correctly answer 21 attention checks during the encoding phase and 6 attention checks during the test phase); (ii) failure to complete five encoding phases and five test phases of the series of training sessions over six possible days (i.e., one training session per day with an extra day allotted for one excused absence); and (iii) disqualification based on demographic exclusion criteria (i.e., the participant passed initial prescreening but indicated in the post-experiment demographics survey that they do not identify with the following criteria: White, non-Hispanic, have lived in the U.S. for 5+ years, aged 18–35). Only participants who completed the study in full compliance with these criteria were included in analyses for tasks during the test phase of training (i.e., face recognition, valence attribution, cued recall of person-knowledge) and the independent face recognition task.

We also excluded trials based on a priori preregistered exclusion criteria. Trials were excluded from analyses for both the test phase of training and the independent face recognition task in the following order: (i) participants responded faster or slower than three standard deviations from their average reaction time; (ii) participants responded within 100 ms or less; and (iii) participants responded faster or slower than three standard deviations from the group average reaction time.

Data analysis

The series of five test phases over the training period included three response components that were converted into corresponding DVs for our analyses. All participants completed all conditions, and all measures were taken from the same sample. Face recognition accuracy was calculated as the number of previously seen faces correctly identified as familiar minus the number of novel faces incorrectly identified as familiar divided by the total number of familiar faces they saw (i.e., hits—false alarms/total hits possible). Valence attribution accuracy was calculated as the number of familiar faces correctly paired with the corresponding information type (i.e., positive, negative, or none) divided by the total number of familiar faces they correctly indicated as familiar. For cued recall of person-knowledge, participant-generated statements were manually coded as correct or incorrect based on judgments from two independent raters (κ = 0.81), with the use of a third tie-breaker rater when there was not consensus among the two raters. Raters were instructed to indicate whether the participant-generated statements sufficiently matched the content of the corresponding person-knowledge statements presented during the encoding phase, even if the participant did not use the exact wording. Cued recall of person-knowledge accuracy was then calculated as the number of correct participant-generated statements divided by the number of paired statements (i.e., 3) for each face they correctly indicated was paired with person-knowledge. For the independent face recognition task conducted before and after training, accuracy was calculated as the number of previously seen faces correctly identified as familiar divided by the total number of familiar faces they saw (i.e., hits/total hits possible).

All data were analyzed using the lme498 and lmerTest99 packages in R96 to run within-participants linear mixed effects regression models100,101,102,103. All analyses are two-tailed with an alpha level of 0.05, and we additionally report for each person memory task during training whether results remain significant after Bonferroni correction. Overall, we ran three preregistered confirmatory aggregate-level training models (i.e., face recognition, valence attribution, cued recall of person-knowledge), so we conducted Bonferroni correction with an adjusted alpha of 0.05/3 = 0.017. For the independent face recognition task, we conducted one preregistered exploratory model with an alpha level of 0.05. No Bonferroni correction was preregistered or conducted for the independent face recognition task. For additional details and a summary table regarding the preregistration of the statistical models, refer to Supplementary Material, Discussion 1.3.

Accuracy for face recognition and valence attribution during the test phase of training was fitted as a function of perceived race, training session, information type, and lifetime interracial contact. As participants only performed cued recall when faces were paired with person-knowledge (i.e., no perceptually familiar only faces), accuracy for cued recall of person-knowledge was fitted using the same predictors, except that information valence was utilized instead of information type. Omnibus models used the following contrast codes: Race, Black (+0.5), White (−0.5); Session, Session 1 (−2), Session 2 (−1), Session 3 (0), Session 4 (+1), Session 5 (+2); Information Type, perceptually familiar only (−2/3), positive person-knowledge (+1/3), negative person-knowledge (+1/3); and Valence, negative (−0.5), positive (+0.5). Lifetime interracial contact was analyzed as a z-scored continuous variable. The models employed random effects to account for between-subject variations in accuracy to the furthest extent possible without overfitting the data, using a standardized procedure to simplify the random-effects structure when necessary98. If an omnibus test indicated a significant interaction, we decomposed the interaction by plotting and calculating simple differences and slopes. When decomposing interactions involving interracial contact, a z-scored continuous variable, we analyzed simple differences at the following scores: 0 (the sample average for contact), +2 (two standard deviations above the sample average), and −2 (two standard deviations below the sample average). The simple differences analyzed using these values are implemented to explain the interaction100,101,102,103.

Accuracy on the independent face recognition task was fitted as a function of perceived race, familiarity, task session, and lifetime interracial contact. The omnibus model used the following contrast codes: Race, Black (+0.5), White (−0.5); Familiarity, novel (−0.5), familiar (+0.5); and Session, pre-training (−0.5), post-training (+0.5). The same procedure from the training models was performed to determine random effects structures and decompose significant interactions. All omnibus models and follow-up analyses are included in the analysis script available on OSF.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

The following sections report the results for the within-participants linear mixed effects regression models run for each memory task. Descriptive statistics for lifetime interracial contact scores and all task accuracy scores may be reviewed in Supplementary Material, Discussion 5.

Face recognition

Results revealed significant main effects of Race, b = −0.117, SE = 0.013, 95% confidence interval (CI95%) = [−0.142, −0.093], t(68.000) = −9.256, p < 0.001; Session, b = 0.062, SE = 0.006, CI95% = [0.051, 0.073], t(68.000) = 11.068, p < 0.001; and Information Type, b = 0.126, SE = 0.016, CI95% = [0.096, 0.157], t(68.000) = 8.022, p < 0.001; as well as significant interactions of Race × Session, b = 0.024, SE = 0.006, CI95% = [0.013, 0.035], t(68.000) = 4.242, p < 0.001; Race × Information Type, b = 0.042, SE = 0.018, CI95% = [0.006, 0.077], t(68.000) = 2.284, p = 0.026; and Session × Information Type, b = −0.016, SE = 0.005, CI95% = [−0.025, −0.006], t(68.000) = −3.245, p = 0.002. These effects were qualified by a significant three-way Race x Session x Information Type interaction, b = 0.028, SE = 0.008, CI95% = [0.012, 0.044], t(1608.000) = 3.392, p < 0.001. There was also a significant two-way interaction of Information Type x Contact, b = −0.039, SE = 0.016, CI95% = [−0.070, −0.008], t(68.000) = −2.443, p = 0.017. Although the Race x Session x Information Type interaction remains significant after Bonferroni correction with an adjusted alpha of 0.017, the two-way interaction of Race × Information Type does not survive. All other reported effects remain significant.

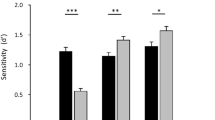

We analyzed simple effects for the three-way interaction of Race × Session × Information Type (Fig. 3). At the mean level, participants were more accurate for perceived White faces compared to perceived Black faces across information type at every session except for faces paired with negative person-knowledge at the fifth and final session. Irrespective of perceived race and person-knowledge valence, participants were more accurate at recognizing faces paired with person-knowledge compared to faces that were only perceptually familiar. Accuracy increased for all information types within perceived race over the first three sessions. After session 3, participants maintained a stable level of face recognition accuracy, continuing to improve for perceptually familiar Black faces only.

Follow-up analyses for the two-way interaction of Information Type x Contact (Fig. 4) demonstrate that, irrespective of valence, low- and average-contact participants were more accurate at recognizing faces paired with person-knowledge compared to perceptually familiar only faces. High-contact participants were similarly accurate regardless of person-knowledge availability. Overall, participants were more accurate at recognizing perceived White faces and faces paired with person-knowledge, though the recognition advantage associated with paired person-knowledge was seen only for participants with lower quantities of interracial contact. To review statistics for all post hoc comparisons for both interactions, see Supplementary Material, Discussion 4.1.

n = 70. The shaded region surrounding each linear regression line represents the 95% confidence interval for the regression coefficient. Lifetime interracial contact, displayed on the x-axis, is a z-scored continuous variable. The standard deviation increments serve as a reference for where participants’ contact scores fall along the sample distribution of interracial contact scores. Marked with a significance indicator (*) where applicable, simple differences were analyzed at −2, 0, and +2, which are referred to here as low-, average-, and high-contact scores due to their relative position in the sample distribution.

Valence attribution

Results revealed significant main effects of Race, b = −0.036, SE = 0.008, CI95% = [−0.052, −0.020], t(67.104) = −4.345, p < 0.001; Session, b = 0.040, SE = 0.004, CI95% = [0.032, 0.048], t(68.230) = 9.520, p < 0.001; and Information Type, b = −0.042, SE = 0.018, CI95% = [−0.078, −0.006], t(67.941) = −2.264, p = 0.027. These effects were qualified by significant two-way interactions of Race × Information Type, b = −0.056, SE = 0.020, CI95% = [−0.096, −0.016], t(67.913) = −2.736, p = 0.008; and Session × Information Type, b = −0.021, SE = 0.009, CI95% = [−0.039, −0.002], t(67.913) = −2.192, p = 0.032. The Race × Information Type interaction remains significant after Bonferroni correction with an adjusted alpha of 0.017. However, the main effect of Information Type and the two-way interaction of Session × Information Type do not survive. The remaining main effects of Race and Session are still significant.

Simple effects for the Race × Information Type interaction (Fig. 5) demonstrate that valence attribution accuracy was similar for perceived Black and White faces when faces were perceptually familiar only or paired with positive person-knowledge. However, participants displayed preferential accuracy for perceived White faces when faces were paired with negative person-knowledge. Differences between the information type conditions reflect that participants were generally more accurate at identifying a lack of paired person-knowledge for perceptually familiar faces compared to attributing statement valence for faces paired with person-knowledge (except for perceived White faces paired with negative person-knowledge). Furthermore, when attributing the valence of person-knowledge paired with perceived White faces, participants were more accurate for negative information compared to positive information. In contrast, for perceived Black faces, participants were more accurate at attributing the valence of positive person-knowledge.

For the Session x Information Type interaction, simple effects revealed that participants improved in valence attribution accuracy from Session 1 to Session 3 but did not continue to increase in accuracy thereafter. While there was no difference in accuracy between information type conditions at sessions 1 and 2, participants were more accurate for perceptually familiar only faces compared to faces paired with person-knowledge beginning at session 3. There were no significant differences between faces paired with positive and negative person-knowledge at any session. In short, participants displayed increased accuracy for identifying a lack of paired person-knowledge compared to attributing the valence of paired person-knowledge starting at session 3. For all post-hoc comparisons, see Supplementary Material, Discussion 4.2.

Cued recall of person-knowledge

Results revealed significant main effects of Race, b = −0.059, SE = 0.010, CI95% = [−0.078, −0.040], t(68.175) = −6.095, p < 0.001; and Session, b = 0.058, SE = 0.007, CI95% = [0.044, 0.073], t(67.921) = 7.819, p < 0.001; as well as a two-way interaction of Race × Session, b = −0.011, SE = 0.004, CI95% = [−0.017, −0.004], t(69.446) = −3.000, p = 0.004. All effects were qualified by significant three-way interactions of Race × Session × Contact, b = 0.010, SE = 0.004, CI95% = [0.003, 0.016], t(68.576) = 2.700, p = 0.009; and Race × Valence × Contact, b = −0.033, SE = 0.013, CI95% = [−0.059, −0.007], t(68.847) = −2.454, p = 0.017.

Simple effects tests for the three-way interaction of Race x Session x Contact (Fig. 6) reflect that accuracy for perceived Black and White faces increased as training progressed, except for low-contact participants who did not significantly improve after session 3. Participants demonstrated a racial bias in cued recall of person-knowledge favoring increased accuracy for perceived White faces, but this effect was shaped over multiple exposures by perceiver interracial contact. As sessions increased, low-contact participants displayed increasingly preferential accuracy for perceived White faces, while high-contact participants became increasingly similar in their accuracy for perceived Black and White faces over time.

n = 70. The shaded region surrounding each linear regression line represents the 95% confidence interval for the regression coefficient. Lifetime interracial contact is a z-scored continuous variable. For representation purposes, here we have plotted cued recall accuracy at the sample average for contact (center), 2 standard deviations below the sample average (left), and 2 standard deviations above the sample average (right). Accordingly, simple differences were analyzed at −2, 0, and +2, which are referred to as low-, average-, and high-contact scores due to their relative position in the sample distribution.

Following up on the additional three-way interaction of Race x Valence x Contact revealed that when averaging across training sessions, recall accuracy only differed between the positive and negative person-knowledge conditions for high-contact participants recalling person-knowledge paired with perceived Black faces. Low-contact participants were more accurate for perceived White faces compared to perceived Black faces only when the paired person-knowledge was negative (i.e., affectively incongruent with race-based prejudices), while high-contact participants demonstrated the same racial bias only when the paired person-knowledge was positive (i.e., affectively congruent). All post-hoc comparisons and a figure may be reviewed in Supplementary Material, Discussion 4.3.

Independent face recognition

Results revealed significant main effects of Race, b = −0.042, SE = 0.009, CI95% = [−0.059, −0.024], t(68.000) = −4.709, p < 0.001; Session, b = −0.049, SE = 0.017, CI95% = [−0.082, −0.015], t(68.000) = −2.846, p = 0.006; and Familiarity, b = −0.071, SE = 0.020, CI95% = [−0.111, −0.031], t(68.000) = −3.472, p = <0.001. Results also revealed a two-way interaction of Session × Familiarity, b = −0.068, SE = 0.030, CI95% = [−0.126, −0.010], t(68.000) = −2.291, p = 0.025. However, these effects were qualified by a three-way interaction of Race × Session × Familiarity, b = −0.157, SE = 0.049, CI95% = [−0.253, −0.061], t(68.000) = −3.204, p = 0.002. There was also a two-way interaction of Session × Contact, b = 0.039, SE = 0.017, CI95% = [0.005, 0.073], t(68.000) = 2.265, p = 0.027.

Simple effects for the Race × Session × Familiarity interaction demonstrate that participants were generally more accurate in the independent face recognition task at the pre-training session compared to the post-training session. Accuracy was similar from pre- to post-training for novel perceived Black faces only. Participants did not significantly differ in accuracy between perceived Black and White faces except for novel faces at the pre-training session when they showed preferential accuracy for novel perceived White faces. In other words, participants displayed a pre-training cross-race recognition deficit for novel faces that diminished at the post-training session due to a pre- to post-decrease in accuracy for novel perceived White faces.

We also followed up on the two-way interaction of Session × Contact (Fig. 7). Independent of perceived race, participants with low and average lifetime interracial contact were more accurate at the pre-training session compared to the post-training session. However, accuracy for participants with high contact did not differ from pre- to post-training. Additionally, at the pre-training session, participants with lower interracial contact displayed higher accuracy compared to participants with higher interracial contact. To summarize, low- and average-contact participants were more accurate at the independent face recognition task before training and decreased in accuracy after training such that there were no post-training differences in accuracy based on contact. All post-hoc comparisons can be found in Supplementary Material, Discussion 4.4. Additionally, the Supplementary Material contains an exploratory analysis of false alarms conducted during the peer review process to explore if increased false alarms during the post-training session converged with the observed decrease in recognition accuracy among lower contact participants. Indeed, the findings reflect that lower contact participants demonstrated a significant increase in false alarms from pre- to post-training. The false alarms analysis, results, and post-hoc comparisons may be reviewed in Supplementary Material, Discussion 6.

n = 70. The shaded region surrounding each linear regression line represents the 95% confidence interval for the regression coefficient. Lifetime interracial contact, displayed on the x-axis, is a z-scored continuous variable. The standard deviation increments serve as a reference for where participants’ contact scores fall along the sample distribution of interracial contact scores. Marked with a significance indicator (*) where applicable, simple differences were analyzed at −2, 0, and +2, which are referred to here as low-, average-, and high-contact scores due to their relative position in the sample distribution.

Discussion

Employing a five-day training procedure, the current study demonstrated that lifetime interracial contact impacts various facets of person memory for racial ingroup and outgroup faces. Consistent with our confirmatory hypothesis, on average, participants displayed a cross-race deficit favoring accuracy for the racial ingroup in face recognition and cued recall of person-knowledge throughout training. Although we predicted that perceiver interracial contact would result in reduced race-based differences in accuracy, interracial contact shaped face recognition independent of perceived race. During training, low- and average-contact participants demonstrated a predicted increase in accuracy for recognizing faces paired with person-knowledge while high-contact participants did not differ in face recognition performance based on person-knowledge availability. Interracial contact similarly impacted accuracy irrespective of perceived race on the independent face recognition task such that low-contact participants showed a reduction in overall accuracy from pre- to post-training while high-contact participants maintained the same level of performance.

In contrast, perceiver interracial contact shaped the recall of person-knowledge in the expected race-dependent manner over the multiple exposures. As training progressed, low-contact participants demonstrated increasingly preferential memory of knowledge associated with racial ingroup faces whereas high-contact participants reduced their bias in recall over time. Although the present study identifies a robust racial bias favoring recall of knowledge about ingroup members among White perceivers, it also demonstrates that increased interracial contact can alleviate this bias.

While the cross-race recognition deficit (CRD) observed across the contact distribution throughout training may initially seem incongruous with some of the prior literature51,52, there are considerations unique to the current study design that may have contributed to the persistent racial bias in recognition. All participants self-identified as White and reported having more contact with White individuals relative to Black individuals throughout their lifetime. Greater perceptual experience with perceived White faces relative to perceived Black faces may have contributed to more accurate recognition for the racial ingroup. While experimentally manipulated contact has been associated with reductions in the CRD71, the current paradigm may not have provided sufficient perceptual individuation training to overcome participants’ disproportionate amount of prior contact with ingroup individuals. The emergence of a potential face recognition ceiling effect after three days of training (see Supplementary Material, Discussion 4.1 for analyses comparing sessions) also points to the possibility that the number of facial exemplars encoded throughout training may not have been sufficient to reduce bias in face recognition ability.

It is also noteworthy that participants reporting low and average contact decreased in accuracy from pre- to post-training on the independent face recognition task independent of perceived race. If, as suggested above, lower-contact participants did not gain sufficient experience encoding new faces to produce generalizable changes in their face recognition ability, the familiarization with a relatively restricted number of faces during training may have disrupted their ability to recognize newly encountered faces post-training. Alternatively, this disruption could be the result of low motivation to meaningfully engage with and individuate the faces in the context of the repeated training sessions14,33. However, this seems unlikely based on the observed recall performance indicative of individuation happening during the training sessions, at least for ingroup faces. Overall, rather than applying their experiences from training to the new task, participants with lower contact may have confused the novel stimuli with facial exemplars amassed over training, resulting in less accurate recognition compared to the pre-training session. This possibility is supported by a significant increase in false alarms from pre- to post-training among low- and average-contact participants (for complete results of the false alarms analysis, refer to Supplementary Material, Discussion 6). Future training studies varying in intensity should consider comparing perceptual individuation with knowledge-based individuation to further explore how experimentally manipulated contact impacts general recognition ability.

Still, it is notable that participants, irrespective of their prior interracial contact, maintained the CRD among repeated exposures and paired person-knowledge throughout training. These findings may reflect a nuance not captured by prevailing definitions of the CRD. There are numerous limitations (e.g., variability in operationalizations of contact, underreporting of null effects) within the literature that may obfuscate the true relationship between contact and the CRD52. Further, more recent work has highlighted a failure to replicate the CRD among perceivers from different racial and ethnic groups and the absence of a consistent relationship between contact and the CRD104,105,106. With this context, the somewhat counterintuitive finding that lifetime interracial contact did not reduce the CRD can be recognized as part of a growing body of work calling for a reexamination of racial bias in face recognition and its relation to interracial contact.

The contribution of person-knowledge to recognition accuracy throughout training reflects that individuals with lower levels of contact were more accurate at recognizing faces when they were paired with person-knowledge at encoding29. Low- and average-contact individuals seemingly benefited from the elaborated processing based on paired person-knowledge during encoding when later attempting to recognize the faces. This pattern is in alignment with existing cognitive models of person memory predicting that activating stored semantic information about a person contributes to better recognition for faces paired with person-knowledge38,39. However, contrary to these models, high-contact participants did not benefit in recognition from paired person-knowledge, suggesting that, for these perceivers, the perception of a face alone may be sufficient to reach the threshold of recognition that other perceivers only reach with the simultaneous activation of associated person-knowledge. High-contact perceivers may therefore encode faces with greater efficiency, readily forming perceptually individuated impressions of faces that promote person memory regardless of whether they are prompted to do so by the pairing of knowledge-based cues. Indeed, recent neuroimaging work suggests that increased interracial contact may be associated with an increase in face processing efficiency and a decrease in the social salience of faces, irrespective of their perceived race. Specifically, perceivers with greater interracial contact exhibit decreased recruitment of brain regions associated with face perception and social cognition relative to perceivers with lower levels of interracial contact79,80,97. The exposure to greater variability of individuals among perceivers with high interracial contact may lead to greater efficiency and conservation of resources during routine face processing.

The increased face processing efficiency among White perceivers with high interracial contact may also explain why contact was associated with a reduction of racial bias solely for demanding impression formation processing (i.e., recall of person-knowledge), but not for face recognition. Indeed, throughout training, participants maintained a mean-level CRD irrespective of their interracial contact. These results are consistent with prior work suggesting that the increased face processing efficiency and decreased social salience of faces associated with increased interracial contact may, in some contexts, lead to reduced spontaneous engagement and suboptimal behavioral performance. For example, performance during face recognition and mentalizing tasks among high-contact individuals was greater only in the presence of explicit motivation conditions33,65. These findings are not indicative of reduced social cognitive ability but instead suggest that individuals with high interracial contact may exert less spontaneous cognitive effort relative to individuals with less interracial contact. However, in contexts of increased motivation, need for individuation, or anticipation of future interactions, individuals with higher contact may display effortful cognitive processing14,33,101 to reap the behavioral benefits of processing efficiency. Consistent with this framework is the interpretation that, during the independent face recognition task, the initial differences in accuracy may have been driven by lower-contact participants exhibiting greater spontaneous cognitive effort during the pre-training session but being disrupted by the subsequent training sessions during the post-training session. In contrast, the greater perceptual expertise and face processing efficiency associated with increased contact may explain why higher-contact participants began with default, less effortful processing but were also able to sustain the same performance without any disruption from training. Overall, this reduced spontaneous social cognitive engagement associated with increased interracial contact may help explain the unexpectedly biased or poor overall recognition performance that has been observed among participants with significant cross-race perceptual experience.

Although we expected that affectively incongruent face-statement pairings would be more easily learned, this was not systematically observed across forms of person memory, training sessions, and participants. This prediction was most closely reflected in valence attribution such that participants tended to be more accurate at attributing the valence of paired person-knowledge for perceived White faces when information was negative and for perceived Black faces when information was positive. However, memory for affectively incongruent person-knowledge was more variable when assessed through cued recall. Only low-contact participants displayed this pattern through increased accuracy for recalling person-knowledge paired with perceived White faces (relative to perceived Black faces) when information was negative, or affectively incongruent with race-based prejudices. In contrast, high-contact participants demonstrated overall preferential recall for affectively congruent person-knowledge. The improved memory for affectively incongruent person-knowledge exhibited across participants during valence attribution, but only among low-contact participants during cued recall, may reflect elaborated or individuated processing for faces paired with knowledge violating affective expectations, especially for ingroup members. In contrast, the unexpected greater recall for affectively congruent person-knowledge among high-contact participants may stem from their reduced spontaneous effortful social cognitive engagement in less salient or motivating contexts4,107. While low-contact participants may have found affectively incongruent face-statement pairings salient, and as a result encoded them more deeply, high-contact perceivers may not have perceived the same statements as incongruent and consequently salient. Perhaps high-contact perceivers were comparatively more engaged by affectively congruent pairings due to a contradiction with personal experiences and/or opposition toward prejudices. Furthermore, deviations from previous findings may in part result from the fact that existing studies generally required participants to attribute statements to an associated individual (e.g., who said what task108,109,110,111) rather than directly recalling the content of person-knowledge paired with a face during encoding. The repeated presentation of stereotype-irrelevant person-knowledge with facial images across multiple encoding sessions also limits comparison to studies that have examined recall based on stereotype-related person-knowledge associated with an indicator of group membership (e.g., category labels, prototypical names) rather than faces112,113,114,115,116,117. Accordingly, future research is imperative to clarify the mechanism behind differences in recall for valenced ingroup and outgroup person-knowledge among perceivers varying in interracial contact.

In contrast to prior work examining how perceived race shapes person-knowledge memory which primarily required perceivers to recognize or attribute, but not recall, information previously learned about others108,118, the present study reveals how perceived race from faces shapes the recall of learned person-knowledge. The findings reveal an initial bias among White individuals in favor of recalling information about the racial ingroup. However, individuals with greater interracial contact were able to eliminate this racial bias in recall over the training period. Perceiver interracial contact appears to positively impact recall even when prerequisite factors for similar effects on recognition (e.g., motivation) are not present. The current findings therefore suggest that contact may be more impactful on how White perceivers recall person-knowledge about outgroup members compared to how they recognize the corresponding faces. This is consistent with an increase in face processing efficiency and a reduction in the social salience of faces among high-contact individuals that does not similarly impact person-knowledge encoding and recall. Indeed, the simultaneous exacerbation of racial bias in recall among low-contact participants further highlights that the advantageous effect of high contact on the reduction of recall bias is not inherent to the study design but rather a result of motivational or cognitive dispositions of individuals with increased contact.

Taken together, the results reflect that while high-contact perceivers may devote less active cognitive effort to encoding faces, maintaining a cross-race deficit in face recognition, they specifically improve their memory for outgroup person-knowledge over multiple exposures. Increased interracial contact may serve to populate the face space with more accessible cross-race representations119, reducing the salience of any individual face relative to the rest. Neuroimaging evidence attests to this effect, demonstrating that the standard preferential activity to racial outgroup faces in the amygdala, a brain region believed to respond to social salience120,121, is attenuated with increased interracial contact16,122. A reduced salience of faces with increased contact may account for the heightened impact of contact on recall of outgroup person-knowledge such that knowledge-based cues retain their salience in impression formation even as faces themselves become less likely to capture and maintain attention.

The current study’s identification of a racial bias in the recall of person-knowledge demonstrates that unique interventions may be necessary to address memory biases beyond those associated with face recognition, particularly in contexts where remembering details about an individual critically influences outcomes such as hiring and legal decisions. In light of the mediating role of outgroup knowledge in the reduction of prejudice associated with increased intergroup contact77, an ingroup bias in recall may have implications for interventions aiming to reduce bias in attitudes. For example, the amplification of this bias in recall among low-contact perceivers over the five-day training suggests that a contact intervention employing the learning of person-knowledge to reduce prejudice may require immersive or extended experience to be beneficial. Similarly, the lack of improvement across perceivers from pre- to post-training on the independent face recognition task does not detract from the utility of contact training interventions71,78. Instead, it suggests that more research is necessary to determine how and when contact training interventions can lead to bias reduction generalizable beyond the intervention contexts. For example, training contexts perceived to be more salient or motivationally relevant by participants may increase performance33 and facilitate generalization of encoding experience to new contexts. The current results highlight the necessity to carefully consider distinct social cognitive processes, including various forms of person memory, to develop successful bias reduction interventions.

Beyond their relevance to the reduction of racial biases in person memory, the current findings also suggest that interracial contact can broadly shape social cognition independent of perceived race. Specifically, prior interracial contact was found to shape face recognition in a race-independent manner during both the training sessions and the independent face recognition task, suggesting that it may facilitate perceptual individuation regardless of perceived race. Indeed, during training, only high-contact perceivers did not demonstrate a deficit in recognition ability for perceptually familiar faces relative to faces paired with person-knowledge. Further, only high-contact perceivers retained similar accuracy on the independent face recognition task pre- to post-training, whereas perceivers with less contact decreased in accuracy following training. Together, these findings suggest that high-contact perceivers have an ability to readily individuate both ingroup and outgroup faces that is not easily disrupted. This lends further support to previous work suggesting that intergroup contact may have a broad impact on cognition, including an increase in cognitive flexibility4,76.

Limitations

Progressing in the examination of interracial contact as a potential intervention to promote equity necessitates increasing attention to how contact may produce change in social cognition and behavior. Echoing recent work105, the observed maintenance of a CRD throughout training reflects a need to address mounting contradictions within the literature on the relationship between interracial contact and cross-race person memory. Researchers should consider comparing the impact of different types of interracial contact (e.g., naturally occurring versus experimentally manipulated contact) across multiple types of measures (e.g., self-report, zipcode data) on varying types of memory (e.g., recognition versus recall) within diverse samples of perceivers. Future studies should also explore how various aspects of face processing, including diversifying the angle and/or context in which face exemplars are encoded, can impact how interracial contact shapes person memory38,123. Indeed, the use of repeated face images during training associated with a given identity could allow perceivers to anchor their memory on the presented images rather than the identity of the face exemplars.

In the present study, as in the existing literature, we observed effects of contact both specific to and independent of perceived race. Here, the study design was necessarily focused on the structure and efficacy of training, limiting the possibility of manipulating the experimental context to observe whether different instructions or types of stimuli (e.g., whole body, complex scenes) shape effects of perceived race. Therefore, it remains to be systematically compared how contact impacts the range from more rudimentary to more complex social cognitive processes124. Additional work should also attempt to differentiate how perceptual versus elaborated, high-quality contact shapes social cognition74,125. It is difficult to infer whether our findings, especially the persistence of a CRD throughout training and the lack of improvement in general face recognition ability, may be a product of the quantity or quality of training. Would including a larger number of faces or longer training period be sufficient to reduce racial biases in face recognition and person-knowledge recall, or would increasing the depth of experience with a limited number of outgroup individuals be more impactful? Additionally, the documented variety in contact effects among participants of different racial and ethnic identities70 should caution that results obtained from the current sample are limited in generalizability to other populations, particularly perceivers belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups. The applicability of contact theory to future interventions is necessarily contingent upon understanding how interracial contact impacts marginalized populations, and future studies should prioritize examining cross-race social cognition with more diverse samples.

Conclusion

It has long been not only theoretically understood but also routinely experienced that lacking person memory for cross-race others permeates our social spheres and can lead to feelings of isolation, difficulties socializing, heightened anxiety about interfacing with outgroups, and dire legal consequences49,126,127,128,129. Contextualized by the potentially ubiquitous societal consequences of racial biases in recall memory specifically (e.g., decisions in employment, legal cases, and medical care), the present finding that recall is differentially shaped by increased interracial contact compared to face recognition should serve to motivate future research on cross-race person memory. Importantly, in addition to these direct outcomes, cross-race deficits in person perception and memory are likely to contribute to and reinforce race-based biases in implicit and explicit attitudes71,130. Considering the downstream consequences of bias in person memory, it is increasingly important to understand when, how, and for whom interracial contact effectively reduces racial bias in social cognition. Illuminating the nuances of how intergroup contact impacts social cognition will bring our collective understanding in closer alignment with the foundational knowledge prerequisite to enacting fully realized contact interventions. On this path, the current findings provide an initial steppingstone toward a mechanistic understanding of how contact shapes behavior by parsing interrelated processes and cultivating optimism that future steps will elucidate underpinnings of contact that may successfully translate to effective interventions and more equitable outcomes.

Data availability

Behavioral data were collected through Inquisit, and self-report data were collected through Qualtrics. Inquisit scripts are available at request, and self-report measures are included at the end of the preregistration available in the Open Science Framework repository at https://osf.io/4k8ve/. The de-identified data for the person memory tasks (i.e., face recognition, valence attribution, cued recall of person-knowledge) during training and the independent face recognition task pre- and post-training are also available in the Open Science Framework repository at https://osf.io/4k8ve/.

Code availability

The R script used to analyze task data is available in the Open Science Framework repository at https://osf.io/4k8ve/.

References

Smith, E. R. Mental representation and memory. in The Handbook of Social Psychology (eds. Gilbert, D. T., Fiske, S. T. & Lindzey-Gardner, G.) vol. 2 391–445 (McGraw-Hill, Boston, 1998).

Malpass, R. S. & Kravitz, J. Recognition for faces of own and other race. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 13, 330–334 (1969).