Abstract

This study examines intra- and interindividual differences in everyday goal pursuit in older adults focusing on the role of emotions and goal representations. Assuming a prioritization of self-preservation in old age, we expected that reduced negative (and elevated positive) emotions would be associated with increased everyday goal pursuit. These links were expected to be moderated by goal representations such that positive emotions would be more strongly linked to greater goal pursuit when goals were represented as hopes, whereas negative emotions would be less strongly linked to reduced goal pursuit when goals were represented as fears. We used up to 21 surveys from 236 individuals collected over 7 days (Age: Mean = 70.5, 60–87 years). Multilevel models revealed that more intense positive emotional experiences and less intense negative emotional experiences were each associated with elevated everyday goal pursuit. As expected, hoped-for goals were associated with stronger positive emotion–goal pursuit associations. Feared goals were associated with weaker negative emotion (particularly worry)–goal pursuit links. Moderations were limited to the most salient goal. These findings provide insights into how everyday emotion dynamics and goal pursuit may be shaped by the way older adults represent their goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Goals play an important role for successful development and well-being across the lifespan and into old age1,2. Prominent aging models highlight motivational processes such as goal selectivity (e.g., prioritizing emotionally meaningful goals) and goal adjustment (e.g., letting go of or modifying untenable goals) as underlying the maintenance of everyday goal pursuit and well-being in old age3,4,5,6. Such motivational processes often involve emotional experiences7, but relatively little is known about the role of emotions in shaping everyday goal pursuit among older adults. Based on motivational theories of emotion and aging, this project seeks to fill this gap by proposing a model that suggests dynamic links between emotions and goal pursuit. Rather than simply viewing emotions as goal outcomes (e.g., goal feedback), our model proposes a perspective that treats emotions as a factor that helps older adults modulate goal-pursuit levels in everyday contexts. To achieve this aim, we investigated the associations between everyday emotions and goal pursuit in the daily lives of older adults. Additionally, we examined whether these associations vary based on how older adults appraise and regulate their goals by analyzing a possible moderation of goal representations—specifically hopes (e.g., achieving a healthy lifestyle) and fears (e.g., developing a chronic condition). We used up to 21 repeated daily life assessments per person collected over 7 days from a community-dwelling sample of 236 older adults.

Everyday emotions and goal pursuit in older adults

Multiple conceptual models propose that emotions play a key role for goal pursuit and goal regulation8,9,10,11. Emotions can serve as information representing feedback about past goal progress, provide insights into current energy levels, or help garner the attractiveness of future goal pursuit. For example, classic cybernetic models of self-regulation12 propose that emotions signal the rate of discrepancy reduction between current status and ideal states. According to this model, positive emotions arise when this discrepancy reduction is perceived to be fast (i.e., favorable goal progress) whereas negative emotions arise when this discrepancy reduction is slow (i.e., unfavorable goal progress)9. Emotional experiences during goal pursuit may also serve to evaluate expectations about achieving goals in the future and shape decisions to pursue or disengage from a goal8,9, thereby influencing future goal pursuit.

Additionally, recent theories of emotion regulation propose that emotions may be the very focus of one’s goals13,14. People generally prefer to pursue positive emotional states over negative ones (i.e., hedonic principle)15, and aging research has shown that such tendencies are more pronounced in old age as compared to younger adulthood16,17. Such emotional preferences in old age could be due to age-related motivational shifts that prioritize self-preservation and emotional well-being in old age3,4. For example, socioemotional selectivity theory proposes that shrinking time horizons go along with a greater emphasis on emotionally meaningful over knowledge acquisition goals4. Older adults have also been shown to have stronger tendencies to attend to and remember positive over negative information18. On the other hand, negative emotional states have been shown to be associated with goal adjustment processes in older adults7. For example, Kunzmann and colleagues propose that the experience of sadness in old age may facilitate goal disengagement in the face of age-related declines. Indeed, findings suggest that sadness facilitates goal disengagement19.

Combining these perspectives, emotions may provide insights into the mechanisms underlying the proposed interplay between goal pursuit and goal adjustment in old age3. Based on feedback loop models9, positive emotions may signal that things are going well thereby fostering goal pursuit whereas negative emotions may operate in the opposite manner. Negative emotions may motivate older individuals to restore emotional tranquility and discontinue goal pursuit. In this view, emotions can serve as a compass, guiding older adults in navigating goal engagement, such as deciding whether to invest more energy in their goals or to pause and restore. Following this reasoning, we expected that positive emotional experiences would be associated with elevated goal pursuit whereas negative emotional experiences would be associated with reduced goal pursuit in older adulthood.

The role of goal representations for everyday emotion–goal pursuit associations

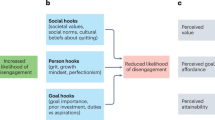

The link between emotional experiences and goal pursuit may also be shaped by the focus of goals. According to the possible selves model20, goals can be represented as positive possibilities one hopes to achieve in the future (hoped-for selves) or as negative possibilities that one seeks to avoid (feared selves). For example, the possible selves of older adults often include concerns about their health which older adults may hope to maintain or fear losing 21,22, resulting in hoped-for and feared possible selves in the health domain23. It has also been suggested that the way goals are represented, as hopes and/or fears, is associated with distinct goal regulatory mechanisms21 thereby shaping everyday goal pursuit24. Specifically, having hoped-for representations of goals may be associated with regulatory processes that prioritize gaining the desired states (i.e., promotion focus), whereas feared goal representations could be associated with regulatory processes that prioritize reducing the realization of undesired states (i.e., prevention focus)25.

Taking this idea a step further and considering the role of emotions, we expected that different goal representations would guide individuals to focus on and utilize different emotional information relevant to goal pursuit. Specifically, individuals with strong hoped-for goal representations may engage in promotion-oriented regulatory processes and recruit positive emotional experiences based on expectations of desirable future states and/or pay greater attention to favorable goal progress8,9. On the other hand, individuals with strong feared goal representations may engage in prevention-oriented regulatory processes that treat negative emotional experiences as an indicator of threat26 and/or an indicator of lack of goal progress27 that warrants prevention efforts.

Putting this idea together with assumptions regarding the bidirectional link between emotional experiences and goal pursuit, we expected the relationship between positive emotional experiences and goal pursuit to be stronger (higher positive emotions linked to elevated goal pursuit) for individuals whose goals have a stronger hope focus whereas negative emotion–goal pursuit associations would be weaker (higher negative emotions linked to less reduced goal pursuit) when goals are represented as fears. Considering previous findings specifically regarding fear-related emotions (e.g., worry) in relation to prevention-oriented regulatory processes28, we additionally explored if individuals with higher feared goal representations would show stronger worry–goal pursuit associations. By examining these moderations, we expected that the relationship between emotions and goal pursuit would vary depending on how older individuals represent their goals.

Present study

This study used pre-existing data from a larger project on spousal health dynamics in old age in Vancouver, Canada29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Repeated daily life assessments were used to capture emotional experiences and goal pursuit as older adults engaged in their daily life routines and environments. We first examined whether everyday emotional experiences and goal pursuit would be associated in such a way that higher positive emotions would be associated with higher goal pursuit whereas higher negative emotions would be associated with lower goal pursuit. Next, we examined the moderating role of goal representations on everyday emotional experience–goal pursuit associations. We expected that different goal representations would guide individuals to focus on and utilize different emotional information relevant to emotion–goal pursuit links. Individuals with strong hoped-for goal representations were expected to recruit positive emotional experiences from hoped-for goal representations to promote their goal pursuit, thereby showing stronger positive emotion–goal pursuit links (i.e., more positive emotions linked to greater goal pursuit). In contrast, those with strong feared goal representations were expected to source negative emotional experiences to facilitate their goal pursuit, thereby showing weakened negative emotion–goal pursuit links (i.e., more negative emotions linked to less weakened goal pursuit). For negative emotions, we additionally explored feelings of worry. Covariates included demographic factors such as age, gender, and cultural background. It is well-established that individuals from different cultural backgrounds show different goal regulatory patterns27. Previous findings also note functional health as an important factor that influences daily activity levels among older adults41 and thus was included as a covariate. Similarly, time of day was controlled for since it may affect goal pursuit (e.g., greater activity engagement during the day than in the evening). Additionally, goal importance was incorporated in the analyses considering its facilitating role in motivational processes such as goal setting and engagement42.

Methods

Participants

A total of 258 individuals (or 129 heterosexual couples) aged 60 years and above were recruited from the greater metropolitan area of Vancouver, Canada for a study on spousal health dynamics in old age (Linked Lives Study, March 2013–April 2017)37. In addition to age (60+) and both partners being available to participate, study eligibility required the capacity to fill out surveys which included being able to read English or Chinese (Mandarin, Cantonese) proficiently, read newspaper-sized print, and hear an alarm clock to detect survey reminders. Since the original study focused on health behaviors (e.g., physical activity), eligible participants also could not have any cardiac, respiratory, musculoskeletal, or neurological conditions for which exercise was contradicted or had been diagnosed with a neurodegenerative disease or brain dysfunction. Participants received 100 CAD for completing the targeted components of this study. Nine couples dropped out and one couple was excluded due to limited command of the study languages. Two participants who did not complete key study variables were also excluded from the analysis. Three daily responses from individuals who submitted more than the asked-for daily questionnaires were removed before analysis. The final sample consisted of 236 older individuals (Age: M = 70.5 years, SD = 6.0, 60–87 years; Ethnicity: 60% White, 34% Asian; Education: 68% at least some college education). The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia (H12-01854), and all participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

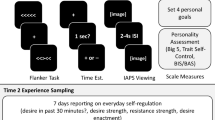

Procedures

The study was composed of two lab sessions (baseline, exit) and 7 consecutive days of repeated daily life assessments in between. During the lab sessions, participants completed questionnaires involving demographic information (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity), goals, and other measures not relevant to the current study. Open-ended goals were assessed during the baseline session. Participants were asked to report three goals they were planning to actively pursue over the upcoming weeks. Participants were instructed to report specific goals that affected their day-to-day activities, rather than choosing abstract goals. For each goal, participants were also asked about the extent to which it represented hoped-for or feared future states. After completing the goals questionnaire, participants took notes of each goal on a small index card, which we referred to as “Goal Card”, to carry with them for their reference when completing daily questionnaires. Participants also received an iPad and general instructions on how to fill out daily questionnaires using the “iDialogpad” app (G. Mutz, Cologne, Germany). For daily life assessments, participants were asked to complete brief surveys five times a day over the course of seven days. Two self-initiated morning surveys did not include goal-pursuit questions and were thus not included in the current study. Later assessments were prompted by beeps at designated times (11 am, 4 pm, and 9 pm) and included questions asking about current emotional experiences and goal pursuit since the previous assessment (Survey duration: Mean = 6.99 min, Median = 6.23 min, SD = 3.52, Range: 0.75–46.22; see Table S1 for details). These measurement times were fixed during the study period and chosen to systematically capture goal pursuit throughout the day. However, participants were instructed to deviate from the designated assessment times if they conflicted with ongoing activities that could compromise their safety (e.g., driving) or other important commitments (e.g., doctor’s appointments). Participants submitted 20.1 daily questionnaires on average out of a total of 21 questionnaires available (96% adherence, Range: 6–21 responses). Out of 4753 total responses submitted, 88.48% of the responses were submitted within an hour range (30 minutes before or after) of the designated times. After 7 days, participants attended an exit session where they returned the study materials and filled out additional questionnaires including study feedback.

Measures

Goals

During the baseline session, participants were asked to report three personal projects, defined as “the kinds of activities and concerns that people have at different stages of their lives”, in an open-ended format43. Participants were instructed to report goals that they were “planning to actively pursue within the upcoming weeks”, “whose realization is highly important for you right now”, and “that influence your daily life and the activities in which you engage in”. These three projects were labeled as Goals A, B, and C respectively; participants were given verbal instructions that these goals did not have to be listed in the order of importance. For each goal, participants indicated which life domains (i.e., partnership, family, friends, physical activity, volunteering, finances, cognition or memory, health, work/productive activities, home management, leisure, other) it belonged to in a multiple answer format and how important it was for them (a 5-point scale, 1 = “not at all”, 5 = “very much”; see Table S2 for descriptive information).

Hoped-for goal representations

After naming their three goals, participants were asked about the extent to which each goal referred to something they hoped for on a 5-point scale (1 = “not at all”, 5 = “very much”; M = 4.03, SD = 0.99).

Feared goal representations

Similarly, participants were asked about the extent to which each goal referred to something they feared on a 5-point scale (1 = “not at all”, 5 = “very much”; M = 2.10, SD = 1.29).

Momentary positive emotions

At each momentary assessment, participants reported their emotional experiences at the moment (e.g., “How happy are you?”) on a scale from 0 to 100 (0 = “not at all”, 100 = “very much”). Positive emotions were measured by eight items (happy, calm, relaxed, content, enthusiastic, interested, excited, satisfied; M = 71.2, SDbetween = 12.8, SDwithin = 9.1). Multilevel confirmatory factor analysis revealed good between- and within-person reliability of positive emotions (ωbetween = 0.84, ωwithin = 0.79; see Supplementary document for model specification and fit results).

Momentary negative emotions

Negative emotions were measured by eight items (sad, overwhelmed, irritated, annoyed, lonely, anxious, tired, nervous; M = 16.4, SDbetween = 12.0, SDwithin = 8.6). Multilevel confirmatory factor analysis revealed good between- and within-person reliability of negative emotions (ωbetween = 0.96, ωwithin = 0.76; see Supplementary document for model specification and fit results). For exploratory analyses, we created a worry construct using two items (anxious, nervous). Generalizability coefficients suggested good between- and within-person reliability (RKF = 0.99, Rc = 0.84).

Goal pursuit

At each assessment, participants were asked to report the effort they invested and progress they made regarding each goal (in the order of Goals A, B, C) since the previous assessment on a scale from 0 to 100 (0 = “none”, 100 = “very much”). These two items were highly correlated for each of the three goals (r > 0.79, p < .001); we thus computed an average momentary goal pursuit score for each goal (Goal A: M = 41.9, SDbetween = 20.3, SDwithin = 21.5; Goal B: M = 38.6, SDbetween = 23.0, SDwithin = 22.3; Goal C: M = 35.2, SDbetween = 23.6, SDwithin = 21.5; Three-goals average: M = 38.5, SDbetween = 19.9, SDwithin = 25.1).

Control variables

Demographic variables such as age, gender, and cultural background (Asian vs. non-Asian) were considered as control variables in all models. Considering the older age of the current sample, we additionally controlled for functional health by creating a composite measure of three different scores: gait speed (i.e., mean time it took to walk 4 meters at usual pace across two trials)44, timed up and go (i.e., mean time it took to stand up from a chair, walk for 6 meters at usual pace, and sit back down)45, mean grip strength46 using a handheld dynamometer (Jamar; Sammons Preston Rolyan, Bolingbrook, Illinois) measured across three trials for each hand. Gait speed and timed up-and-go scores were multiplied by -1 so that higher scores indicated higher functional status. Each index was standardized and then averaged to create a composite score. At the goal level, we controlled for perceived goal importance (1 = “not at all”, 5 = “very much”; M = 4.16, SD = 0.89). Lastly, time of day (i.e., assessment time point: 0 = 11 am, 1 = 4 pm, 2 = 4 pm) was also taken into account, since goal pursuit could vary based on circadian rhythm47 or social construction of time48.

Statistics and reproducibility

The main hypotheses and the overall analytic scheme were preregistered before the data analysis (https://osf.io/hkqym; February 1, 2022). To account for the discrete nature of three different goals reported by each person, we conducted our analyses in two ways: goal-specific analysis (Goals A, B, and C separately) and goal-combined analysis with goals designated as a separate level in the nested data structure (i.e., goals nested within individuals). All findings are reported irrespective of their significance. Goal-combined analyses treated the three goals as random data points sampled from each participant, which assumes that these goals are independent of each other if the dependency from their sources (i.e., individuals) is considered in the model. However, we found a pattern suggesting a systematic goal hierarchy among the three goals such that goals differed by importance according to reporting order (i.e., Goal A > B > C; see Table S2). Thus, goal-specific analyses were conducted to accommodate potentially different natures of the three goal categories.

For both types of analyses, we used multilevel modeling to account for the nested data structure. The levels were specified as couples at level 4, individuals at level 3, goals at level 2, and assessment occasions at level 1. The goal level was omitted for goal-specific analyses. This structure allowed us to separate sources of variance and covariance among the key variables across different levels. Person-level variables (level 3) included age, gender, cultural background, and functional health. Goal-level variables (level 2) included goal importance, hoped-for and feared goal representations. Assessment-level variables (level 1) included time of day and emotional experiences. Person- and goal-level variables were centered at their sample means. Emotion variables (e.g., positive emotions) were divided into person-average emotion scores which were centered at the sample means (i.e., overall positive emotions of person i compared to the average of positive emotions across the sample), and assessment-level emotion scores which were centered at person-average scores (i.e., momentary deviation of positive emotions at time point t from the person i’s overall positive emotions). Additionally, emotion variables were rescaled by dividing the scores by 10 to facilitate model convergence. Detailed model equations can be found in the Supplementary document. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. We used the lme449 and lmerTest 50 packages for multilevel modeling, the sjPlot package51 to create results tables and standardized coefficients (β), and the interactions package52 to run simple slope analyses53.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Descriptive information of key variables and goals

Correlations among the key variables are provided in Table 1. Older age was associated with higher person-average goal pursuit during the study period. Higher positive emotions were associated with higher goal pursuit across assessment and person levels, and higher negative emotions and worry were associated with lower goal pursuit at the assessment level, only. Hoped-for and feared goal representations were positively correlated to each other and to goal importance. Higher feared goal representations were also associated with lower person-average positive emotions and higher person-average negative emotions.

Everyday emotions and goal pursuit in older adults

We first examined everyday associations between emotional experiences and goal pursuit using goal-combined analyses where we designated goals as a separate level in the multilevel structure. Consistent with our hypothesis, elevated positive emotional experiences were associated with increased goal pursuit at both the person (b = 3.22, 95% CI [1.49, 4.96], t(228.56) = 3.64, p < 0.001, β = 0.13) and the assessment (b = 1.59, 95% CI [0.92, 2.27], t(99.37) = 4.64, p < 0.001, β = 0.05; see Model 1 in Table 2) levels. Elevated negative emotional experiences were associated with reduced goal pursuit at the assessment level, only (b = −1.03, 95% CI [−1.70, −0.35], t(93.98) = −2.97, p = 0.003, β = −0.03; see Model 1 in Table 3). Asian participants reported significantly higher goal pursuit regarding all three goals than non-Asians (b = 22.67, 95% CI [17.53, 27.82], t(163.21) = 8.64, p < 0.001, β = 0.34; see Model 1 in Table 2). Additionally, higher goal importance was associated with greater goal pursuit (b = 2.29, 95% CI [0.58, 4.00], t(657.37) = 2.62, p = 0.009, β = 0.06; see Model 1 in Table 3).

Concerning goal-specific analyses, the magnitude and the statistical significance of positive emotion–goal pursuit associations were significant across all goals but most salient for Goal A (person level: b = 4.57, 95% CI [2.50, 6.63], t(219.46) = 4.33, p < 0.001, β = 0.18; assessment level: b = 2.05, 95% CI [1.25, 2.85], t(108.98) = 5.01, p < 0.001, β = 0.06; see Model 2 in Table 2). Similarly, the assessment-level association between negative emotions and goal pursuit was most salient for Goal A (b = −2.10, 95% CI [−2.93, −1.27], t(79.37) = −4.96, p < 0.001, β = -0.06; see Model 2 in Table 3) and was not significant for Goal C (see Model 4 in Table 3). There were no statistically significant associations between negative emotions and goal pursuit at the person level. Interestingly, participants reported higher goal pursuit earlier in the day for Goal A (b = −1.06, 95% CI [−1.83, −0.28], t(4473.65) = −2.68, p = 0.007, β = −0.03) and later in the day for Goal C (b = 1.87, 95% CI [1.10, 2.64], t(4456.94) = 4.76, p < 0.001, β = 0.05; see Table 2). Higher functional health was also associated with greater goal pursuit on Goal A (b = 4.24, 95% CI [0.35, 8.13], t(227.11) = 2.14, p = 0.033, β = 0.10; see Model 2 in Table 2).

The role of goal representations for everyday emotion–goal pursuit associations

Next, we examined whether goal representations would moderate the everyday association between emotional experiences and goal pursuit. When goals were analysed in combination, the moderation of hoped-for goal representation was not significant. However, goal-specific analyses revealed that there was significant moderation concerning Goal A at the assessment level (b = 1.07, 95% CI [0.25, 1.88], t(180.72) = 2.56, p = 0.010, β = 0.03; see Model 2 in Table 2). Specifically, the Johnson–Neyman plot suggests that higher hoped-for representations were associated with elevated goal pursuit when momentary positive emotions were elevated (see Fig. 1). This pattern was not observed regarding Goals B and C.

Johnson–Neyman plot examines the simple slopes of positive emotion on goal pursuit in relation to the moderator (hoped-for goal representation for Goal A). Simple slopes were only significant on a higher score range of the moderator, indicating stronger positive emotion–goal pursuit links for those with higher hoped-for goal representation. People with strong hoped-for goals engage in more goal pursuit when their positive emotions are elevated.

For feared goal representations, the moderation between negative emotional experiences in general and goal pursuit was not significant in the goal-combined analysis but it was significant concerning Goal A at the assessment level (b = 0.62, 95% CI [0.03, 1.20], t(103.06) = 2.05, p = 0.040, β = 0.02; see Model 2 in Table 3). The Johnson–Neyman plot showed that lower feared representations were associated with greater reductions in goal pursuit when momentary negative emotions were elevated (see Fig. 2). This pattern was not observed regarding Goals B and C. Exploratory analyses on discrete negative emotions revealed that there was a significant moderation of feared goal representation in worry–goal pursuit links in both goal-combined analysis (b = 0.38, 95% CI [0.04, 0.71], t(303.81) = 2.22, p = 0.026, β = 0.02; see Model 1 in Table 4) and regarding Goal A (b = 0.71, 95% CI [0.26, 1.16], t(78.72) = 3.10, p = 0.002, β = 0.03; see Model 2 in Table 4). These patterns were not observed for other discrete negative emotions such as anger (Table S6) or sadness (Table S7).

Johnson–Neyman plot examines the simple slopes of negative emotion on goal pursuit in relation to the moderator (feared goal representation for Goal A). Simple slopes were only significant on a lower score range of the moderator, indicating weaker negative emotion–goal pursuit links for those with higher feared goal representation. People with strong feared-for goals show the typical association between increased negative emotion and impoverished goal pursuit less strongly.

To understand our findings specific to Goal A, we conducted additional analyses. Out of total 708 goals reported (3 goals \(\times\) 236 individuals), we selected two subsets of goals: 1) those with the highest importance ratings from each participant (a subset 451 goals from 236 participants), and 2) those related to health (a subset of 304 goals from 214 participants). This was because Goal A tended to have higher goal importance ratings and a high prominence of goals in the health domain (see Table S2). When the same analytical models were applied with these new goal selections, the same moderation of feared goal representations in worry–goal pursuit links was found but no other results we found concerning Goal A were replicated (see Tables S8–9). We discuss these results more in detail in the Discussion.

We additionally examined whether hoped-for goal representations moderated the relationship between negative emotion and goal pursuit and whether feared goal representations moderated the relationship between positive emotion and goal pursuit. Neither moderation was significant, suggesting that each goal representation is uniquely associated with its respective emotion–goal pursuit link. Finally, neither hoped-for representations nor feared representations were significantly associated with everyday goal pursuit.

Discussion

Using daily life assessments from community-dwelling older adults, this study focused on the role of emotional experiences and goal orientations for everyday goal pursuit in old age. By focusing on the role of emotions and goal representations, we tried to shed light on the conditions under which everyday goal pursuit is higher or lower and the ways in which different goal-regulatory processes (indexed by different goal representations) may shape emotion-goal pursuit associations in old age.

Everyday emotions and goal pursuit in older adults

We found that more pronounced positive emotional experiences were associated with elevated goal pursuit whereas momentary increases in everyday negative emotions were associated with lower goal pursuit. This could be due to a prioritization of emotional well-being in old age in such a way that favorable emotional states may foster goal pursuit among older adults4,18. For example, positive emotions could signal currently available resources that help older individuals to maintain goal pursuit54. It is also conceivable that goal engagement brings about positive emotional experiences if emotionally meaningful goals are set. On the other hand, negative emotional experiences may signal goal-related barriers. When those barriers are related to age-related decline, older adults may adjust or disengage from their goals to protect their well-being3,55,56. There is also evidence regarding the utilitarian function of negative emotions for goal pursuit57, but research emanating from the lifespan developmental literature shows that contra-hedonic motivations are more salient in young age than in old age16. Future research using a broader age range could explore whether the emotion–goal pursuit links we found may be moderated by age.

The role of goal representations for everyday emotion–goal pursuit associations

We found a goal-promoting role of hoped-for representations regarding everyday positive emotion–goal pursuit associations whereas there was a goal-protecting role of feared representations regarding everyday negative emotion–goal–pursuit associations. The model of possible selves suggests that individuals engage in different regulatory behaviors based on the potential future outcomes they attend to20. When future goals are mainly represented as positive aspirations (i.e., hoped-for goals), individuals may look for positive information during goal pursuit (e.g., interim progress, potential gains), and corresponding positive feelings may invigorate further goal engagement. On the other hand, individuals may attend to negative information such as negative outcomes or shortfalls if their goals are mainly represented as something they dread (e.g., feared goals) and corresponding negative emotional experiences such as worry may facilitate goal pursuit in this case. These moderations were significant only at the within-person level, which may suggest that these goal regulatory processes operate on time-varying emotional fluctuations rather than on the stable emotional traits individuals possess.

Of note, feared goal representations significantly interacted only with fear-related emotions (i.e., worry) but not with other negative emotions such as anger or sadness in predicting everyday goal pursuit. It is possible that goals with feared representations may have fostered to development regulation strategies specific to fear-inducing situations. This is consistent with previous findings showing functional benefits of fear-related emotions when pursuing prevention goals28. Although we are providing some reasoning on how these factors could have affected our findings, they were not specified at the preregistration stage and thus need to be further examined in future research.

Another point that may be worth discussing is that the direction of moderation was different between the two goal representations. The moderation of positive emotion–goal pursuit associations was significant for individuals scoring high on hoped-for goal representations whereas the moderation of fear–goal pursuit associations was significant for individuals with low scores on feared goal representations. This could speak to different functions of goal representations. Hoped-for representations may have a boosting function that encourages goal pursuit when experiencing positive emotions. In contrast, feared representations may have a preventative function that buffers impairment of goal pursuit when experiencing negative emotions. Thus, having hoped-for representations could be beneficial and not having feared representations could be detrimental to everyday goal pursuit in old age. In line with regulatory focus theory 25, it is possible that older individuals may recruit both regulatory systems to pursue goals in the face of varying everyday situations instead of sticking to one. This is also partly supported by the fact that both goal representations were positively correlated with goal importance, and hoped-for and feared representations were also positively correlated with each other (see Table 1). It would be interesting for future research to explore the effects of combined hoped-for and feared goal representations on goal regulatory processes, for example examining whether they build up upon each other (e.g., synergy) or conflict with one another (e.g., ambivalence).

Finally, it is important to note that the moderation of goal representations was only significant for participants’ most salient goal (Goal A). Additional analyses were conducted to explore whether this could be due to Goal A being of high importance or in the health domain given the high representation of health-related goals among those listed as Goal A. These analyses replicated findings from feared representations regarding its interaction with worry in predicting goal pursuit, but no other results were replicated. Given the inconsistency in the results, we conclude that the characteristics of Goal A could not be attributed to one or two specific factors. Instead, Goal A may be best described as the most salient and accessible goal, which was reported first, and frequently engaged in, and typically of high importance (though not always). For example, physical activity may be salient and easy to report as the first goal on the list for those who are engaging in exercise, but this goal could still be less important than a social goal like caring for a family member. Nevertheless, our post-hoc analyses may have limitations, and future research should consider other factors in the study design (e.g., question order effect) or focus on a single salient goal to replicate our findings.

Limitations

Our study used an ecologically valid design. Using repeated daily life assessments, we were able to capture everyday fluctuations in feelings and goal pursuit while participants engaged in their everyday routines. The adherence rate of momentary assessments was high (96%). The idiosyncratic approach in investigating personal goals may have introduced some noise in relation to various goal characteristics, but we also took a nomothetic approach by using a motivational framework that consists of networks of goal representations, emotions, and goal pursuit58. Our sample was composed of community-dwelling older adults from the Metro Vancouver area, British Columbia, Canada. To include participants who are relatively underrepresented in research, our team translated study materials into Chinese (Mandarin, Cantonese) to reduce participation barriers for Chinese-speaking older adults.

Despite its strengths, our study is not without limitations. The repeated daily life assessments in participants’ natural environments may have introduced some errors in our measurements. Such approaches may be complemented by experimental designs that specifically focus on testing emotion–goal associations. We were successful at recruiting 34% of East Asian participants into our final sample which seemed important considering local demographics but do now know if our findings generalize to other cultural contexts. Additionally, our Asian participants reported significantly higher everyday goal pursuit compared to non-Asian participants. Many factors could have contributed to this difference including cultural differences in how people conceive of everyday goals, personal obligations regarding goal-related commitments, or response styles, to list a few. Addressing these factors is beyond the scope of this study, so we leave this finding to be further explored in future research.

We elicited three goals from each participant to examine different goal-related activities older adults engage in in everyday life. This created a challenge for data analysis because we had to reconcile the diversity of goal-relevant activities pursued in everyday life and the distinctiveness of each goal. Of course, we believe that the solution to addressing this challenge will depend on the focus of one’s research question and thus needs to be addressed in the early stage of study design. If one is interested in the role of activity diversity on daily well-being after retirement in old age, one may choose a setup that asks a range of different projects older adults pursue instead of asking only a small number of goals. On the other hand, if the focus is to understand self-regulatory processes underlying one’s core personal projects59, one may focus on a goal that people most care about. Additionally, our Goal A specific results may be associated with other goal characteristics such as goal specificity or goal domain which were not part of our theoretical models. These factors should be further investigated in future research.

We were not able to provide further granularity in our analyses to the theoretically outlined links between emotional experiences and goal pursuit. We proposed a feedback loop between emotional experiences and goal pursuit such that emotional experiences may promote or hinder goal pursuit but also may arise subsequent to goal progress. There are statistical models available to examine such reciprocal links (e.g., cross-lagged panel model)60, but our study design did not provide enough statistical power to utilize such techniques. Thus, future research may consider using large panel data or recruiting a large sample with shorter lags between the measurement points to examine two-way links between emotional experiences and goal pursuit. Such designs would also enable researchers to address other interesting phenomena, such as the time-varying dynamics of the interplay between different goal regulatory processes.

Finally, another promising direction for future research would be to focus on potential mechanisms, which could not be thoroughly examined in the current study due to its correlational nature. We proposed that emotions might serve as a compass to modulate goal pursuit among older adults. Specifically, given older adults’ priorities of self-preservation, we expected positive emotions to be associated with continued goal pursuit, whereas negative emotions would correspond to reduced goal pursuit. To further investigate this idea, future studies could examine whether such goal modulations yield positive outcomes, such as changes in the sense of control. It may be reasonable to predict that the successful adjustment of goal pursuit based on emotional states may be linked to a higher sense of control. Additionally, it would be intriguing to explore whether the relationship between goal modulations and control varies depending on the goal regulatory processes (e.g., promotion versus prevention) that individuals engage in.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that positive future goal states can boost older adults’ goal pursuit in relation to everyday positive emotional experiences. However, there may also be value to fear negative future goal states since such goal representations may buffer the potential impact of momentary negative emotions on goal pursuit. Being able to recruit different regulatory mechanisms may be useful to promote everyday goal-related activities in old age.

Data availability

The data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author for verification purposes. The data are not publicly available due to their dyadic nature which goes along with a greater risk of re-identification. Open data access was not part of the consent process. Summary data for the two figures are available at https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/LLQGA4.

Code availability

Analytic code is available at https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/LLQGA4.

References

Emmons, R. A. Personal strivings: an approach to personality and subjective well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1058–1068 (1986).

Heckhausen, J. & Schulz, R. A life-span theory of control. Psychol. Rev. 102, 284–304 (1995).

Brandtstädter, J. & Rothermund, K. The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: a two-process framework. Dev. Rev. 22, 117–150 (2002).

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M. & Charles, S. T. Taking time seriously: a theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 54, 165–181 (1999).

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C. & Schulz, R. A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol. Rev. 117, 32–60 (2010).

Wrosch, C. & Scheier, M. F. Adaptive self-regulation, subjective well-being, and physical health: The importance of goal adjustment capacities. in Advances in Motivation Science vol. 7 199–238 (Elsevier, 2020).

Kunzmann, U., Kappes, C. & Wrosch, C. Emotional aging: a discrete emotions perspective. Front. Psychol. 5, (2014).

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Nathan DeWall, C. & Zhang, L. How emotion shapes behavior: feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11, 167–203 (2007).

Carver, C. S. & Scheier, M. F. Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: a control-process view. Psychol. Rev. 97, 19–35 (1990).

Clore, G. L. & Huntsinger, J. R. How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 393–399 (2007).

Shaffer, C., Westlin, C., Quigley, K. S., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Barrett, L. F. Allostasis, action, and affect in depression: insights from the theory of constructed emotion. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 18, 553–580 (2022).

Carver, C. S. & Scheier, M. F. Control theory: a useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychol. Bull. 92, 111–135 (1982).

Tamir, M. Effortful emotion regulation as a unique form of cybernetic control. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 16, 94–117 (2021).

Tsai, J. L. Ideal affect in daily life: implications for affective experience, health, and social behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 17, 118–128 (2017).

Taquet, M., Quoidbach, J., de Montjoye, Y.-A., Desseilles, M. & Gross, J. J. Hedonism and the choice of everyday activities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9769–9773 (2016).

Riediger, M., Schmiedek, F., Wagner, G. G. & Lindenberger, U. Seeking pleasure and seeking pain: differences in prohedonic and contra-hedonic motivation from adolescence to old age. Psychol. Sci. 20, 1529–1535 (2009).

Riediger, M. & Freund, A. M. Me against myself: motivational conflicts and emotional development in adulthood. Psychol. Aging 23, 479–494 (2008).

Mather, M. & Carstensen, L. L. Aging and motivated cognition: the positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 496–502 (2005).

Barlow, M. A. et al. Discrete negative emotions and goal disengagement in older adulthood: Context effects and associations with emotional well-being. Emotion 22, 1583–1594 (2022).

Markus, H. & Nurius, P. Possible selves. Am. Psychol. 41, 954–969 (1986).

Hooker, K. Possible selves and perceived health in older adults and college students. J. Gerontol. 47, P85–P95 (1992).

Smith, J. & Freund, A. M. The dynamics of possible selves in old age. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 57, P492–P500 (2002).

Cross, S. & Markus, H. Possible selves across the life span. Hum. Dev. 34, 230–255 (1991).

Hoppmann, C. A., Gerstorf, D., Smith, J. & Klumb, P. L. Linking possible selves and behavior: do domain-specific hopes and fears translate into daily activities in very old age? J. Gerontology: Ser. B 62, P104–P111 (2007).

Higgins, E. T. Promotion and prevention: regulatory focus as a motivational principle. in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology vol. 30 1–46 (Elsevier, 1998).

Aspinwall, L. G. & Taylor, S. E. A stitch in time: self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychol. Bull. 121, 417–436 (1997).

Heine, S. J. et al. Divergent consequences of success and failure in Japan and North America: an investigation of self-improving motivations and malleable selves. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 599–615 (2001).

Tamir, M. & Ford, B. Q. Choosing to be afraid: preferences for fear as a function of goal pursuit. Emotion 9, 488–497 (2009).

Ashe, M. C. et al. Linked lives: exploring gender and sedentary behaviors in older adult couples. J. Appl. Gerontol. 39, 1106–1114 (2020).

Lüscher, J. et al. Having a good time together: the role of companionship in older couples’ everyday life. Gerontology 1–12 (2022).

Michalowski, V. I. et al. Intraindividual variability and empathic accuracy for happiness in older couples. GeroPsych 33, 139–154 (2020).

Michalowski, V. I. et al. Time-varying associations between everyday affect and cortisol in older couples. Health Psychol. 40, 597–605 (2021).

Pauly, T. et al. Positive and negative affect are associated with salivary cortisol in the everyday life of older adults: A quantitative synthesis of four aging studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology 133, 105403 (2021).

Pauly, T., Gerstorf, D., Ashe, M. C., Madden, K. M. & Hoppmann, C. A. You’re under my skin: long-term relationship and health correlates of cortisol synchrony in older couples. J. Fam. Psychol. 35, 69–79 (2021).

Pauly, T. et al. Moving in sync: hourly physical activity and sedentary behavior are synchronized in couples. Ann. Behav. Med. 54, 10–21 (2020).

Pauly, T. et al. Cortisol synchrony in older couples: daily socioemotional correlates and interpersonal differences. Psychosom. Med 82, 669–677 (2020).

Pauly, T. et al. Everyday associations between older adults’ physical activity, negative affect, and cortisol. Health Psychol. 38, 494–501 (2019).

Ungar, N. et al. Joint goals in older couples: associations with goal progress, allostatic load, and relationship satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 12, 623037 (2021).

Yoneda, T. et al. What’s yours is mine”: partners’ everyday emotional experiences and cortisol in older adult couples. Psychoneuroendocrinology 167, 107118 (2024).

Zambrano, E. et al. Partner contributions to goal pursuit: findings from repeated daily life assessments with older couples. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 77, 29–38 (2022).

Baltes, M. M., Wahl, H.-W. & Schmid-Furstoss, U. The daily life of elderly germans: activity patterns, personal control, and functional health. J. Gerontol. 45, P173–P179 (1990).

Locke, E. A. & Latham, G. P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 57, 705–717 (2002).

Hoppmann, C. A. & Klumb, P. L. Daily goal pursuits predict cortisol secretion and mood states in employed parents with preschool children. Psychosom. Med. 68, 887 (2006).

Cesari, M. et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people—results from the health, aging and body composition study. J. Am. Geriatrics Soc. 53, 1675–1680 (2005).

Beauchet, O. et al. Timed up and go test and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 15, 933–938 (2011).

Ensrud, K. E. et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch. Intern. Med. 168, 382–389 (2008).

Schmidt, C., Collette, F., Cajochen, C. & Peigneux, P. A time to think: circadian rhythms in human cognition. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 24, 755–789 (2007).

Suk, H. W., Choi, E., Na, J., Choi, J. & Choi, I. Within-person day-of-week effects on affective and evaluative/cognitive well-being among Koreans. Emotion 21, 1114–1118 (2021).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Soft. 67, (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Soft. 82, (2017).

Lüdecke, D. sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science. 2.8.17 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.sjPlot (2024).

Long, J. A. Interactions: comprehensive, user-friendly toolkit for probing interactions. 1.2.0 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.interactions (2019).

Choi, Y. et al. Replication analytic code for everyday emotion–goal pursuit associations in older adults and the moderation of goal representations. Borealis https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/LLQGA4 (2025).

Fredrickson, B. L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226 (2001).

Wrosch, C., Miller, G. E., Scheier, M. F. & de Pontet, S. B. Giving up on unattainable goals: benefits for health? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 251–265 (2007).

Charles, S. T. Strength and vulnerability integration: a model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychol. Bull. 136, 1068–1091 (2010).

Tamir, M. What do people want to feel and why? Pleasure and utility in emotion regulation. Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 18, 101–105 (2009).

Emmons, R. A. The Personal Striving Approach to Personality. in Goal Concepts in Personality and Social Psychology (ed. Pervin, L. A.) (Psychology Press, 1989).

Personal Project Pursuit: Goals, Action, and Human Flourishing. (Lawrence Erlbaum Associations, Mahwah, N.J, 2007).

Usami, S., Murayama, K. & Hamaker, E. L. A unified framework of longitudinal models to examine reciprocal relations. Psychol. Methods 24, 637–657 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-123501 to C. A. Hoppmann, M. C. Ashe, D. Gerstorf, S. Heine). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Theresa Pauly gratefully acknowledges support from the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) Program. Yoonseok Choi and Elizabeth Zambrano Garza gratefully acknowledge support from their Four Year Doctoral Fellowship from the University of British Columbia (UBC). We also thank the study participants who generously contributed their time, and research assistants in the Health and Adult Development lab at UBC, and community partners for their support in participants recruitment and data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. conceptualized the study hypotheses, designed analytical models, conducted data analysis, and took the lead on writing the manuscript. E.Z.G. provided feedback on data analysis and manuscript. T.P. contributed to data processing and edited the manuscript. M.C.A. contributed to funding acquisition, project design, and implementation, and she provided feedback on the manuscript. K.M.M. contributed to funding acquisition, project design, and implementation, and he provided feedback on the manuscript. D.G. contributed to funding acquisition, project design, and implementation, and he edited the manuscript. C.A.H. is principal investigator of this project, she provided feedback on the manuscript, and she mentored the first author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jennifer Bellingtier. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, Y., Zambrano Garza, E., Pauly, T. et al. Everyday emotion–goal pursuit associations in older adults are moderated by goal representations. Commun Psychol 3, 49 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00213-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00213-w