Abstract

Hypothetical scenarios provide an extremely useful alternative to field experiments for scholars interested in nudging behavior change, comprising a substantial proportion of the literature. Yet the extent to which hypotheticals accurately estimate real-world treatment effects is not well understood. To investigate, we identified five recent field studies of real-world nudges in distinct domains and designed four styles of hypothetical scenarios to approximate each one. This setup allows for clear comparison of old field data with new hypothetical data. Across our 20 experiments (N = 16,114), hypothetical scenarios nearly always estimated the correct direction of treatment effects. However, they varied widely in estimating magnitudes, making them unreliable inputs to real-world policy applications such as cost-benefit analyses. Our findings underscore the promising value of hypotheticals, but also the need for greater investigation into strategies to calibrate their estimates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Policymakers, managers, and marketers alike seek reliable, science-driven techniques to change behavior. Nudges—psychologically informed changes to the environment surrounding a behavior—hold particular promise1. Yet limited budgets and logistical complexities often preclude studying these interventions in the wild, with real contexts and consequences. In such cases, researchers frequently turn to hypothetical scenarios, asking participants to imagine what they would choose or how they would behave.

A substantial slice of the nudge literature is built on hypothetical scenarios. In a review of 156 such studies published between 2008 and 2016, 32% of studies were hypothetical and 20% of papers relied exclusively on hypothetical results2. Similar statistics describe an even broader review spanning 1982–20213. This reliance on hypotheticals has only increased: Of 193 nudge experiments in 121 papers published in 2022, 48% were hypothetical and 41% of papers contained only hypothetical results (SI Section 2a–c).

Hypothetical evaluations of nudges serve many important purposes. They provide existence proofs that a nudge might work, unpack mechanisms, and inform actionable policies—especially when field data are costly to collect or recommendations are urgently needed (see SI Section 2d). However, it remains unclear how well hypothetical treatment estimates reflect their real-world counterparts—a gap that will be the focus of the present research.

The published literature mostly includes concordant examples, where researchers pair a field study with a hypothetical study to investigate mechanisms and the results are similar (for an example, see ref. 4). But exceptions of non-concordance exist—such as in the context of nudging COVID-19 vaccinations5. Publication bias may also mask greater heterogeneity, assuming it is easier to publish studies with concordant hypothetical-real results and consistent narratives6. Understanding the conditions under which hypotheticals do and do not approximate real-world effects—or at least directionally align—is critical to helping researchers make the best use of this low-cost tool.

There is much interdisciplinary evidence that hypotheticals exaggerate absolute outcomes—meaning, people are likely to overestimate their behavioral intentions, regardless of whether they are in a control or treatment group. For example, economists have repeatedly shown that hypothetical incentives increase willingness-to-pay, boost demand for consumer products, reduce risk aversion, and exaggerate prosociality—although the hypothetical-real gap is not always large7,8,9,10. Likewise, psychologists have shown that hypothetical moral scenarios can mislead, eliciting less selfish and utilitarian choices than their real-world counterparts11,12. Beyond general respondent uncertainty13, candidate mechanisms driving such “hypothetical bias” include social desirability—people overreport engaging in hypothetical behaviors in order to “look good”14,15—and the intention-action gap—people fail to follow through on intentions16,17. Given the vast majority of behaviors being “nudged” are pro-social, good-for-you, or socially required behaviors18—such as donating, exercising more, or paying taxes—it would be surprising if these same mechanisms didn’t also exaggerate absolute outcomes in hypothetical studies of nudges.

Yet absolute outcomes are rarely the primary focus of researchers using hypothetical scenarios to study the effects of nudges. Rather, relative outcomes—i.e., treatment effects—matter as much if not more. Whether hypotheticals provide calibrated estimates of treatment effects is a question about which little is known beyond one-off examples. Observationally, there appears to be little difference between the average effects collected from hypothetical studies versus real studies when looking across 251 binary treatment effects in a recent review (MHyp Lift = 0.137, MReal Lift = 0.129, Diff = 0.008, 95% CI [-0.084, 0.099], z = 0.155 p = .877)3 (see SI Table S3 for analysis, which includes only their binary data in order to be commensurable with the binary data from the studies in this paper). However, this difference has a wide confidence interval, and the comparison doesn’t pit hypothetical and real studies of the same behavioral situation against each other.

We do so in this paper, identifying five recent field experiments from distinct behavioral domains where participants were nudged to take up a target behavior, and then constructing hypothetical scenarios to estimate each of their results (see Table 1). In each, participants were randomized into control and treatment groups and asked if they would hypothetically engage in the given behavior, or not.

How well should we expect hypotheticals to fare? For example, hypotheticals may provide calibrated estimates of treatment effects even if they overestimate outcomes, as long as they do so for treatment and control conditions equally. Alternatively, they may asymmetrically inflate one or the other, interacting with some feature of the stimuli—especially given the artificially focused environment inherent to surveys. Figure 1 illustrates these possibilities.

The violin plots illustrate made-up data, comparing field results (leftmost facet in gray) with three possible hypothetical results (remaining facets in white). The black dot shows the mean takeup rate, and the colored dots show the made-up raw data. Y-axis Behavioral Choice: 0 = Did not takeup behavior, 1 = Did takeup behavior. Figure legend: Gold = Control, Purple = Treatment.

We examine how these possibilities play out in practice, with particular attention to whether it depends on features of the hypothetical scenario itself. Features of the target field setting—such as the population, desired behavior, and nudges—are largely fixed by field partners, often a company or government. But features of hypothetical scenarios are easily controlled by researchers and—as evidenced by studies with crowdsourced designs19,20—likely matter. We selected two that prior literature recommends to enhance scenario realism and participant accuracy: complexity—e.g., multiple steps and personalization—and specificity—e.g., using actual stimuli and names from the target field study.

There is good reason to believe that more complex and specific hypothetical scenarios might yield more calibrated results. Best practices in psychological vignette design advocate for contextually rich scenarios—e.g., images, personalization, and detailed descriptions—that use specific information from the target field setting—e.g., names of locations, brands, or organizations21,22,23,24,25,26,27. MRI studies likewise argue that more versus less realistic stimuli mimic neuroscientific differences in brain activity when making real versus hypothetical choices28,29,30. Theoretically, the more realistic the scenario, the more realistic the participants’ responses—and the more accurate hypothetical estimates of treatment effects will be. Yet empirically, it is unclear whether these best practices hold up, given that most of the hypothetical studies in the aforementioned reviews2,3 employed simple, non-customized setups (SI Section 2b, c). Best practices are not popular.

In this paper, we investigate how well hypothetical evaluations of nudges reflect real treatment effects from prior field studies and whether it depends on the complexity and specificity of scenarios. We compare best practices with popular practices by systematically varying these two features, constructing hypotheticals for multiple target field studies for robustness. Specifically, we report the results of 20 pre-registered experiments (N = 16,114) covering four styles of hypothetical scenarios—simple-generic, complex-generic, simple-specific, and complex-specific—and five field studies from distinct behavioral domains—consumer choice, finance, health, sustainability, and transportation. To evaluate accuracy, we draw inspiration from practical applications of hypotheticals: existence proofs (asking whether the nudge treatment shifts behavior in the target direction), policy guidance (asking whether the results warrant rollout), and sample estimates (asking how much sample to collect in a corresponding field study). Given the greater evidence for the first two applications (see SI Section 2d), we focus on the first two in the main text and the third in the supplement (SI Section 6b). Although we did not pre-register any directional hypothesis ex ante—given conflicting best practices and common practices, as well as the absence of prior literature about hypothetical effects overall—our analyses operationally take accurate estimation, or equivalence, as the null hypothesis.

Methods

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations and received approval from the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (ID: 853845). Each participant provided informed consent at the start of their designated study. All pre-registrations, study materials, and primary data are publicly available at the following link: https://researchbox.org/1992

Selecting field studies

We selected five target real-world experiments from the recent nudge and choice architecture literature. Each represented distinct domains where the use of hypotheticals was prevalent, as shown in Table 1: consumer choice, finance, health, sustainability, and transportation. (See SI Section 3a for more detail on our selection process.) Notably, the consumer choice field experiment contained two behavioral variables—stopping for a donut and price paid per donut. We focus on the first binary variable in the main text, for comparability across the 20 experiments, and report the continuous variable in SI Sections 4–5.

Constructing hypotheticals

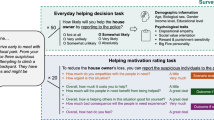

Next, we constructed hypothetical scenarios for each of our five field studies. To explore the impact of scenario design, we systematically varied the complexity of the setup (e.g., length, personalization, images) and the specificity of the descriptors (e.g., proper nouns naming relevant locations or brands) in a 2 × 2 factorial design. A simple hypothetical setup included barebones context on a single screen. A complex setup included personalization, images, and enriched details across a sequence of multiple screens. Generic descriptors stripped out proper nouns that might identify the particular context (e.g., the location or organizations involved in the target experiment), while specific descriptors included those nouns. See SI Fig. S3 for a schematic.

Figure 2 provides an example modeled on a field study in which individuals walking through a university yard were nudged to stop at a stand for a donut and, if they stopped, pay for it (our “consumer choice” study)4. First, we varied the complexity of the hypothetical setup, presenting either a “simple” scenario on a single screen or a “complex” scenario that flowed across multiple screens and employed personalization (e.g., imagining what they would be doing, with whom, on a typical weekday morning). Second, we varied specificity, presenting either a “generic” descriptor that used an abstract representation of proper nouns situating the study (“[at] a nearby university campus”) or a “specific” one that used the actual name (“[at] the campus of the University of California, San Diego”). (See SI Figs. S4–S7 for our broader set of designs.)

The figure illustrates the four hypothetical studies paralleling the real field experiment on consumer choice4, where passersby on a university campus (UCSD) were nudged to stop for a donut. The control message was “pay what you want” while the treatment was “pay what you can”. The four treatment combinations varied the complexity of setup (simple/complex, shown in the central/right panels) and specificity of descriptors (specific/generic, shown as green/purple font) systematically across four hypothetical designs. The field design (real setup with specific descriptors) is shown to the left. Each hypothetical scenario ended by eliciting the target behavior, prompting participants to explain their choice, and asking them to rate the imaginability of the scenario on a five-point Likert scale (“How easy was it to imagine yourself in this scenario?”)

Altogether, we ran four parallel hypothetical experiments to contrast with each of our five field studies, yielding a total of 20 experiments.

Sampling and recruitment

Prior to the experiments, we conducted power analyses in order to have sufficient power to detect the original effect size of each experiment. To illustrate, for the sustainability study, our power analysis indicated needing n = 223 per condition to detect the original effect with 80% probability (and an alpha of 0.05). We rounded up to collect n = 300 or N = 2400 total across the two conditions and four hypothetical designs.

Where the small size of the field estimate required a larger sample than reasonably available (e.g., thousands per condition), we aimed to collect enough participants to detect six times the original estimate. This admittedly rough multiplier is just a proxy, and comes from a recent review31 that estimated that academic study results are approximately six times the size of practitioner studies of the same nudge technique (see SI Section 3c for details). We ultimately collected at least n = 200 per cell, i.e., for every condition × hypothetical design × field domain (min n = 217, max n = 890; the latter is for the transportation study which pools three treatments). In total, we collected data from N = 17,573 participants; after following our pre-registered rules for dropping incompletes, failed attention checks, and duplicate IP addresses, data from 16,114 participants remained for analysis. Only N = 196 dropped out of our surveys due to a failed attention check or closing the survey prior to completion. (See SI Table S8 for all summary statistics).

We recruited participants from Prolific (an online platform), screening for sub-populations to better match the original field populations without impractically limiting our available pool. For example, given our sustainability study was run with university students in the United States, we used pre-set filters to screen for participants from that country who had higher education experience and who explicitly noted whether or not they were currently a student. Recruitment language is in SI Section 3d.

We pre-registered our studies on June 12, 2023 and July 11, 2023, and ran them shortly thereafter—between June 13 and July 21, 2023 (always after their respective re-registration). The updated sustainability study was pre-registered on December 22, 2024 and run on December 23, 2024. Participants were allocated to only one domain x hypothetical design × condition, and then excluded from participating in any other study in the present work, to ensure independence. Within a given domain, participants were evenly allocated to conditions with the exception for the finance study, where randomization occurred in blocks by birthday month (following the design of the original field study).

For supplementary demographics, we asked participants to report their gender, phrased as “With which gender do you most identify?” Options included: Male, Female, Non-binary, Not listed or prefer not to say. Similarly, we asked participants to report their ethnicity, phrased as “With which ethnicity do you most identify?” Options included: American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, White/Caucasian, Other (please specify), Prefer not to say. Finally, we asked participants to report their age phrased as “How old are you?” Options were inclusive of 18–99 years old. We did not use these variables in our analyses nor did we pre-register doing so. All were optional and were collected with consent.

Table 2 and Table 3 show the distribution of responses to the gender identification and ethnicity identification questions, respectively, by experiment.

All participants earned $0.54 for completing our three-minute surveys.

Outcome variables

Our focal measure was whether or not a participant hypothetically engaged in the target behavior (1) or not (0). We summarized the percentage of participants engaging in the behavior for each condition of each experiment. Then, we calculated treatment effects in three ways: as a difference (percent engaging in the behavior in the treatment group minus the percent engaging in the behavior in the control group), as a risk ratio (percent engaging in the behavior in the treatment group divided by the percent engaging in the behavior in the control group), and as an odds ratio (percent engaging in the behavior in the treatment group divided by the percent not engaging in the behavior in the treatment group, divided by the same ratio—the odds of success—in the control group). We present the first in the main text and the latter two in the supplement (SI Section 6a).

For example, in the simple and generic hypothetical design of our consumer choice study, 84.3% of participants in the control group and 78.0% in the treatment group said they would stop for a donut. As a difference, the treatment effect is 78.0–84.3% = -6.3%. As a risk ratio it is 78.0%/84.3% = 0.925. And as an odds ratio, it is (78.0%/22.0%)/(84.3%/15.7%) = 0.660.

Comparing design features

We compared results across our four hypothetical designs using a series of regressions. Specifically, we regressed condition, setup (simple/complex), descriptors (generic/specific), and their two-way interactions on the outcome variable of each study (take up of the target behavior or not). This allows identification of potential significant differences across our two design features, their interactions with each other, and their interactions with condition type (control, treatment). We applied the Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment for multiple comparisons to the p-values of each regression, with an alpha level of p = 0.05. Given our focus on binary outcomes (which do not typically meet the assumptions of normality and homoskedasticity) and our field’s prevalent use of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, we run both OLS and logistic regressions for robustness32.

Comparing sign

When hypotheticals are used as existence proofs, researchers look for the sign of the effect to be in the target direction (e.g., positive, if the nudge is meant to increase a target behavior). We used a two-sided binomial test (with an alpha level of p = 0.05) to statistically evaluate whether the sign on treatment effects (absolute lift) differed between our hypothetical experiments and their corresponding field studies, more than chance (50%).

Comparing magnitude

Hypotheticals may also be used for general policy guidance, if they yield large enough effects to make the cost of implementation worthwhile. Although “large enough” is necessarily subjective, we can, at least, assess whether a hypothetical effect is larger or smaller than actually measured in the field context—and therefore how they anchor policy expectations. We conducted a simple two-sided binomial test (with alpha level of p = .05) to statistically evaluate how often hypotheticals underestimated (versus overestimated) treatment effects, first when calculated as the absolute value of the difference (absolute value of treatment minus control) and second when calculated as an odds ratio (treatment odds divided by control odds). We use the absolute value for the former given the consumer choice study yielded uniformly negative lift values, and our focus in this test is on magnitudes.

Following our pre-registration, we also ran a series of two-sided tests of equivalence to statistically evaluate how closely each hypothetical estimate of nudge treatment effects came to the estimate from the corresponding field study—or, more simply, whether it could be considered a “replication”. Our null hypothesis was that they were equivalent and our alternative hypothesis was that the difference was beyond some minimal bounds, i.e., a minimal effects hypothesis33. As pre-registered, we set these bounds to plus or minus two standard errors from the original effect size. For robustness, we re-ran these analyses varying the bounds from 0 to 0.2 standardized units. We also applied the Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment for multiple comparisons to the set of four hypothesis tests within a given domain; we did not apply it when using the pooled estimate. We used an alpha cutoff level of p = .05. Pooled results are reported in the main text; results by hypothetical design are reported in SI Section 6c.

Each series of two-sided tests of equivalence are run three times, using difference, the log odds ratio, and Cohen’s d as measures of effect size. Canonical examples of the MET test take Cohen’s d as the standardized mean difference metric. Conversion of our binary data to Cohen’s d using the log odds ratio approach yields the same MET results as merely inputting the log odds ratio itself, given Cohen’s d is calculated as the log odds ratio times a constant (standard method: π/sqrt(3) or Cox method: 1.65). Therefore, we report only the first two specifications in the main text; our R code contains the third.

Notably, the informativeness of the equivalence test analysis, even with bounds set to zero, is necessarily limited by the precision of each real and hypothetical effect (i.e., lower precision of treatment effect estimates increases the probability of overlapping estimates and, accordingly, the probability of being labeled a replication).

Comparing sample size

Hypotheticals may also be used as inputs to power calculations, where researchers can use them to help estimate the necessary sample to detect an effect in a subsequent real-world study. To estimate this, we used a two-sided z-test of two independent proportions, set power to 80%, and set alpha to 0.05. We then examined whether each calculation provided a sample size that would have been large enough to detect the effect that actually occurred in the real-world field study. Further, we ran a two-sided binomial test to statistically evaluate whether the rate at which hypotheticals underestimated (versus overestimated) treatment effects differed from chance (with an alpha level of p = 0.05). The detailed results of this analysis and additional specifications are in SI Section 6b.

Deviations from pre-registered analyses

We adhered to our pre-registered data collection plans in all but one set of experiments, collecting an additional set of participants in the four finance experiments due to a miscalculation in our original power analysis. After helpful feedback on early drafts, we deviated from our pre-registered analyses in three ways. First, we decided to focus on only binary outcomes for simpler cross-domain comparison; this required us to re-run the sustainability study to enable sensible conversion of its continuous outcome to a binary interpretation. Second, we added higher-level versions of our pre-registered regression, pooling across hypothetical styles and conditions for clearer contrasts. (Notably, these were pre-registered when we re-ran the sustainability study.) Third, since each of our pre-registrations was specific to a single field study and its corresponding set of hypothetical experiments, we never pre-registered our cross-domain analyses, namely our binomial tests comparing results to chance. See SI Table S1 for a detailed explanation of each deviation from the original set of five pre-registrations. All pre-registrations can be accessed at: https://researchbox.org/1992.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Hypotheticals overestimated behavioral outcomes across conditions

Consistent with prior literature in adjacent fields (e.g., willingness-to-pay studies), hypotheticals exaggerated the levels of all behavioral outcomes—i.e., participants said they would engage in each given behavior far more than actually occurred in the previously run studies in real-world contexts. In terms of the main outcome of each domain (averaged across control and treatment groups), participants in our studies were more likely to say that they would turn their thermostats to 68 degrees Fahrenheit or lower (88.3% vs. 42.6%, BHyp = .457, 95% CI [0.416, 0.498], t(2798) = 22.223, p < 0.001), choose a healthy snack (58.6% vs. 45.5%, BHyp = .131, 95% CI [0.058, 0.204], t(1948) = 3.565, p < 0.001), opt in to carpooling (76.7% vs. 0.10%, BHyp = .766, 95% CI [0.762, 0.770], t(595630 = 412.156, p < 0.001), choose the delayed savings option (17.8% vs. 3.2%, BHyp = 0.146, 95% CI [0.134, 0.158], t(8279) = 23.124, p < 0.001), or stop for a donut (72.1% vs. 9.4%, BHyp = .627, 95% CI [0.603, 0.651], t(5397) = 53.661, p < 0.001), than participants did in the corresponding field settings. (See SI Table S9 for corresponding regression output.)

As shown in Fig. 3, hypotheticals inflated summary proportions across conditions and experiments—but to widely varying and sometimes dramatic degrees across study contexts. Across all hypothetical scenarios, for example, participants in the transportation study were several hundred times more likely to say they would opt into a company carpool program than participants in the original field study. Likewise, in the consumer choice and finance studies, our participants were 4.5 to 8.5 times more likely to say they would take the relevant action (stopping for a donut and saving in a future month) than field participants did, and between 1.5 and 3.5 times more likely in the sustainability study (turning the thermostat to 68 or lower).

The violin plots compare field results (leftmost facet) with hypothetical results from four styles of hypotheticals (Simple & Generic, Simple & Specific, Complex & Generic, Complex & Specific). The colored dots show the raw data, the black dot shows the mean takeup rate by condition, and the black bars represent ±2 standard errors. Y-axis Behavioral Choice: 0 = Did not takeup behavior, 1 = Did takeup behavior. Figure legend: Gold = Control, Purple = Treatment. Sample for Consumer Choice studies: Field nC = 882, nT = 898; Simple & Generic nC = 453, nT = 450; Simple & Specific nC = 457, nT = 452; Complex & Generic nC = 454, nT = 455; Complex & Specific nC = 448, nT = 450 Sample for Finance studies: Field nC = 2595, nT = 2100; Simple & Generic nC = 606, nT = 295; Simple & Specific nC = 575, nT = 316; Complex & Generic nC = 587, nT = 312; Complex & Specific nC = 594, nT = 301. Sample for Health studies: Field nC = 100, nT = 100; Simple & Generic nC = 217, nT = 218; Simple & Specific nC = 220, nT = 219; Complex & Generic nC = 221, nT = 216; Complex & Specific nC = 220, nT = 219. Sample for Sustainability studies: Field nC = 159, nT = 160; Simple & Generic nC = 310, nT = 308; Simple & Specific nC = 310, nT = 314; Complex & Generic nC = 308, nT = 312; Complex & Specific nC = 309, nT = 310. Sample for Transportation studies: Field nC = 39900, nT = 14987; Simple & Generic nC = 289, nT = 872; Simple & Specific nC = 282, nT = 879; Complex & Generic nC = 297, nT = 878; Complex & Specific nC = 291, nT = 890.

The notable deviation from this pattern of overwhelming exaggeration is the treatment group of the health study. In that comparison, the real-world outcome is slightly higher than those of its four hypothetical proxies. A possible explanation for this exceptional result is that the curiosity nudge originally employed in this field study was implemented in conversation with a research assistant, and its effects may have been particularly effective in-person versus digitally. In contrast, the primary component of all other nudges in our hypothetical studies was written communication: signs, emails, and letters.

Unlike the large differences in the exaggeration of behavioral outcomes across domains, exaggeration does not appear to vary significantly across the four hypothetical designs within three out of the five contexts. Moreover, in domains where variation occurs (consumer choice and transportation), the differences are inconsistent across domains. In consumer choice, the hypothetical designs with complex setups (multiple screens, personalization) yielded lower donut takeup rates than their simpler counterparts (BComplex = -0.207, SE = 0.025, 95% CI [−0.158, −0.256], t(3612)= −8.192, adjusted p < .001, SI Table S11; see SI Tables S12–14 for additional specifications). In transportation, the hypothetical designs with specific descriptors (naming the city and the employer) yielded higher carpool program takeup rates than in their generic counterparts (BSpecific = 0.119, SE = 0.028, 95% CI [0.064, 0.174], t(4671) = 4.311, adjusted p < .001, SI Table S11).

Fully unpacking the various factors (e.g., measurement artifacts vs. substantive domain-specific influences) driving the observed heterogeneity in how much hypotheticals inflated results, and grounding these factors in theory-based explanations, would require a much larger and more comprehensive investigation than we have attempted here. For example, perhaps participants are systematically worse at imagining what they would do in a professional context (as in our transportation study) versus an educational context (as in our sustainability study); disentangling this effect from numerous other differences across these cases would require multiple studies from each context as well as more variation across unit types and operationalizations. For our purpose, it is sufficient to note that whatever the reasons for the variability in magnitude, the consistency of the upward bias across studies is striking and reflects the bias found in prior research.

Hypotheticals consistently predicted the sign of treatment effects, but not the magnitudes

Although the wide variation in exaggeration across domains is notable and raises interesting questions about the generative mechanisms, it does not necessarily invalidate hypothetical studies as inexpensive and convenient proxies for field experiments. As already noted, researchers running hypothetical studies to test the efficacy of nudges are often more interested in whether or not the nudge works compared to the control—and by how much—than the exact levels within each condition. In other words, as long as the hypothetical behavioral outcome is exaggerated consistently (vis-a-vis the “real” outcome) across treatment and control conditions, then the direction and potentially even the magnitude of the treatment effect could accurately predict what would happen in a field setting, and hence serve as a useful proxy. Conversely, if hypothetical outcomes across treatment and control conditions are exaggerated to different extents, then the hypothetical treatment effect could be a substantially different magnitude than the real effect or even in a different direction altogether. In the latter case, a hypothetical study would be a strictly worse guide to reality than no study at all, but even in the former case it could be misleading depending on the difference in magnitude.

Figure 4 visualizes treatment effects across all experiments, organized by the underlying field study (e.g., consumer choice) and the hypothetical scenario (e.g., simple and generic). Treatment effects are calculated as the simple difference between treatment and control conditions (see SI Figure S8 for the same data presented as odds ratios and risk ratios). The dashed line indicates the effect from the real field study. Wherever the sign matches for the real and hypothetical data, hypothetical scenarios yielded at least directionally correct results.

The colored dots show the estimated difference between the treatment takeup rate and the control takeup rate (i.e., the lift); the error bars represent ±2 standard errors around this estimate; the gray line extends the estimate for the field study across facets for comparison with estimates from the four hypothetical studies. Y-axis Difference between Treatment takeup rate and Control takeup rate: 0 = No difference. Figure legend: Gray = The field study which serves as a reference, Purple = Sign of difference is the same for the field study and the hypothetical study, Gold= Sign of difference is the opposite for the field study and the hypothetical study. The sample n for all studies is the same as listed beneath Fig. 3. The consumer choice study yielded all negative differences, such that a more extreme negative difference represents overestimating the effect magnitude. (See SI Figure S8 for the same data presented as a risk ratio and as an odds ratio).

Figure 4 shows two main results. First, hypotheticals identify the correct direction of real nudge treatment effects in all but one experiment—a rate far exceeding chance (95% success rate, X = 19, n = 20, 95% CI [0.751, 0.999], p < 0.001). The instance in which they deviate is the complex and specific hypothetical scenario for the transportation study, where more participants said they would engage in the target behavior (taking up carpool) in the control condition than in the treatment condition. This case may have been driven by reactance to getting “nudged” by the particular employer in the study, which was named in both that design and in the simple and specific scenario design—where the resulting effect is the next closest to reversing in sign. Further research would be required to verify this idiosyncrasy.

Second, hypothetical effect sizes generally differ in magnitude from real effects and range widely in relative size. We found no statistically significant evidence of systematic under- or over-estimation (underestimation rate of absolute lift 45%, X = 9, n = 20, 95% CI [0.231, 0.685], p = 0.824; see SI Section 6a for other specifications).

The degree to which the hypothetical effect size over- or underestimates the real effect appears to depend on the hypothetical design, but not in a consistent way across domains. For example, the complex-specific design (the right-most bars in Fig. 4) is the closest to the real effect in two domains (consumer choice and finance) but farthest in one (sustainability) and suggesting the wrong direction in another (transportation). Our corresponding regression analyses find no statistically significant evidence. (See interaction terms between condition and hypothetical designs in SI Table S11. The p-values after adjusting for multiple comparisons are. Treatment*Complex: Consumer: p = 0.219, Finance p = 0.640, Health p = 0.259, Sustainability p = 0.702, Transportation p = 0.367. Treatment*Specific: Consumer: p = 0.829, Finance p = 0.701, Health p = 0.553, Sustainability p = 0.702, Transportation p = 0.097.)

Are these varied differences in magnitude large enough to render hypothetical studies unreliable proxies? One way to answer this question is to ask whether or not hypothetical estimates come close enough to real estimates to be considered “replications,” using a series of two-sided tests. Each replication test sets bounds around the real-world estimate of effects (e.g., ±1pp.) and asks whether we can reject the null hypothesis that the hypothetical estimate falls within those bounds, i.e., serves as an effective replication. Given our focus on binary outcomes—i.e., an already standardized unit—we run this analysis with two standardized metrics for robustness: lift and log odds ratios.

By this measure, we reject the null of replication for only the very largest real-world effect: health. Table 4 shows that all other domains fail to reject equivalence in either one or both specifications, at least within our pre-registered bounds of plus or minus two standard errors. This was not always due to large standard errors in the real-world studies: the large samples of the transportation and finance studies drove very small bounds, within which the hypothetical study results collectively fell. However, when we measure treatment effects as a log odds ratio, this specification magnifies the difference between the hypothetical and real effects—especially where base rates are near-null—flipping the test conclusions for the transportation study from insignificant to significant. Table 4 shows results from comparing the real, field study effect estimate to the hypothetical estimate pooled across designs. Results are substantively similar when broken out by design (SI Table S17) or when using different test bound specifications (see SI Section 6c).

Another way to answer the “does it matter” question is through sample size calculations. If a researcher in one of our field studies had planned their sample size based on the hypothetical effects estimated here, would they have been under-powered to detect the real-world effect? We find this to be the case in the consumer choice, finance, and transportation studies (see SI Section 6b). Hypothetical effects did not statistically differ (in the aforementioned two-sided tests) but were large enough that they would have led to insufficient samples. How often researchers use hypotheticals as proxies for sample size calculations, however, is unclear and challenging to accurately measure (see SI Section 2d).

Discussion

Hypothetical scenarios are an important low-cost tool for estimating the potential impact of nudges on behavior change. Researchers rely on them for pilot-testing interventions, estimating research or rollout costs, and guiding policy. Yet limited evidence evaluates whether nudging hypothetical behaviors accurately approximates nudging real-world behaviors, or on which features accuracy depends.

In this paper, we investigated features that are generally within researchers’ control: the design of the hypothetical scenario. Across five behavioral experiments we designed four styles of hypotheticals—simple-generic, complex-generic, simple-specific, and complex-specific—and examined their ability to estimate the absolute outcomes and treatment effects of each real-world study.

Estimates of outcomes

First, we found that hypotheticals exaggerated behavioral outcomes, concordant with prior literature in other fields (such as economics and moral judgment). The margin by which outcomes were inflated varied widely, less due to hypothetical designs and more due to contextual and measurement particularities (e.g. adjusting the temperature on a thermostat versus opting into a company carpool program).

This variability alone carries practical implications. At the very least, researchers and practitioners would likely be led astray if they used hypothetical outcomes like ours as an input to planning. For example, if using the data from our finance or transportation studies to invest in real-world corporate benefits for employees, they would wildly overestimate program uptake by a factor of 5.54 in the former and 794.75 in the latter. Even in the less consequential case of planning the operations of an actual donut stand on campus, relying on the hypothetical result would cause one to overstock donuts and overestimate total expected revenue (see willingness-to-pay results in SI Table S8), reducing profits. If the amount of hypothetical exaggeration were consistent across domains, an easy solution would be to simply adjust hypothetical outcomes downward by some factor. Unfortunately, the large variance we observed across domains means this solution is practically impossible; the factor would be guesswork, leading just as easily to over- or under- adjustments.

Estimates of treatment effects

Second, in all but one of the 20 experiments, hypotheticals identified the correct valence of real nudge treatment effects. This consistency suggests they may serve as an effective low-cost tool for existence proofs or to detect nudges that are likely to backfire when rolled out in the field—although extending this work to additional field studies with strong, negative effects would be necessary to fully validate the latter. In contrast, hypotheticals varied widely in how well they approximated magnitudes and, correspondingly, served as inputs to policy decisions. No gold standard hypothetical design emerged across our four styles—that is, none reliably provided more accurate estimates of treatment effects across the five sets of experiments.

What actionable conclusions would we make if we had run these hypothetical studies in order to make inferences about future, corresponding field studies? The choice architecture interventions in our health and sustainability studies would have been given a green light to roll out, yielding surprisingly large results in the field. Our consumer choice intervention would likely have been shelved or reworked, considering the treatment decreased the rate of (hypothetically) stopping for a donut. And those in our finance and transportation studies may or may not have been rolled out, depending on the hypothetical design that happened to be run (e.g., the complex and specific scenario yielded a near-null effect and backfired, respectively), whether the estimated sample was unfeasibly large, and broader cost-benefit tradeoffs (e.g., sending variations of mailers may have no incremental cost). Further, if rolled out with a large enough sample to have detected the real effects (i.e, estimates previously observed in the field settings), stakeholders would have been vindicated in the former but disappointed in the latter.

Potential mechanisms

From a practical perspective, these results collectively suggest that hypothetical estimates of the treatment effects in our five field contexts would have provided little consistent signal on whether each study was worth running or not. Which hypothetical style was used mattered little. If anything, the base rate of takeup in the real-world context appeared most informative for calibrating expectations. When the behavior was incredibly unpopular—e.g., a 10% or smaller takeup rate in the real-world control group, in our five field contexts—it was also hard to nudge, and hypotheticals often overestimated effects. Above that threshold, hypotheticals underestimated effects. Although research is needed to validate the generalizability of this pattern and identify potential mechanisms, we offer two speculations for future research.

First, regression to the mean offers the simplest explanation. Hypotheticals underestimated the effects for field contexts with very large treatment effects, and tended towards overestimation for those where treatment effects were considerably small. (See SI Fig. S11 for a visualization.) The line between small and large effects is, of course, difficult to define34, and more research is needed to check if repeated measures in those contexts regress as well.

Second, attentional mechanisms in hypothetical and real-world contexts may be at play. Very small and very large effects are possible in real-world contexts where everyday distractions can pull attention away from stimuli and target behaviors. Specifically, very small treatment effects may emerge in settings with overall low attention, while very large treatment effects can emerge when attention is asymmetrically lower in the control group. These phenomena are less likely in hypothetical studies, given participants’ attention is often artificially and equally drawn to the stimuli of each condition, as well as to the elicited target behavior.

To illustrate, consider our field studies with smaller effects. In the real-world context of the consumer choice study, students and visitors walking through campus might be hurrying to class, checking their phones, or chatting with a friend. They could easily overlook a donut stand with either the control or treatment sign—or they could notice the sign, but not notice the operative difference, which was in this case a single word. Likewise, employees opening their mail might be reflecting on the workday, talking with family, or preparing dinner. They might merely skim over one-time letters about optional corporate benefits (retirement savings in the finance study, carpooling in the transportation study) and not notice the operative text or images of the treatment. Or they might even throw the letters in the junk pile, unopened—something nearly impossible to do in an online environment with limited distractions.

Next consider our field studies with larger effects—health and sustainability. Individuals approached by a researcher in a library likely had little choice but to pay attention to and notice the differences in the cookies offered to them. But they were especially likely to do so when told (in the treatment group) that one cookie will reveal something the researcher “knows about you”. Similarly, the salient milestone of winter break likely made lowering the thermostat top-of-mind for some students, but did so especially for those (in the treatment group) who had received an official university email about it three times in the last week. In these two studies, attention to the target behavior was asymmetrically lower in the control condition—which is often challenging to authentically create in online, hypothetical scenarios.

If robust, these contrasts may be a natural consequence of how researchers rely on controlled settings such as hypothetical scenarios. In lab studies more broadly, we often aim to create a sensory “cocoon” that protects participants from supposedly irrelevant influences or distractions that might shift the spotlight away from the x-y relationship of interest35. As a result, compliance in hypothetical scenarios can often be inescapably and artificially high across conditions, while compliance in real-world contexts can be extremely low and even asymmetric between conditions. Further investigation into these mechanisms would be valuable in order to design hypothetical scenarios that imitate not only the psychological but also the attentional influences of the real-world contexts they aim to approximate.

Implications

While our collective findings do not definitively highlight a “best” hypothetical design, they do suggest rules of thumb—each of which presents a hypothesis for future, confirmatory study.

-

1.

If sign is all that matters, keep it simple: In our sample, at least, hypotheticals effectively predicted the sign of treatment effects. For researchers focused only on directionality of effects, simple and generic designs—the easiest to create and the shortest for participants—may be best.

-

2.

If magnitude is critical, use hypotheticals for field settings where compliance is symmetric across conditions and high: In hypothetical contexts, participants tend to pay more attention to experimental stimuli and target behaviors than in real-world situations. They more easily notice operative elements of treatment stimuli, and they cannot easily overlook the target behavior—even in a control condition with no stimulus—as it is often directly elicited (“would you do…?”). Accordingly, hypotheticals may perform better when estimating effects from real-world contexts where attention—and compliance—is naturally as high and symmetric across conditions as in controlled research settings.

-

3.

Use caution if using hypotheticals in power calculations: We are skeptical of using hypothetical estimates as inputs to sample size calculations for field studies, particularly when the base rate of compliance in the field setting is low. In many of our cases, studies would have been under- or overpowered by an order of magnitude (or more).

-

4.

Pre-test proper nouns and brand names: We found that naming the employer in the transportation study exaggerated uptake significantly. This wasn’t true for naming Krispy Kreme as the donut in our consumer choice study, or naming universities across our finance, health, or sustainability studies. Researchers may want to pre-test whether the research population they plan to sample reacts differently to a genericized or specific name, and/or they may want to run their hypothetical scenarios both ways.

-

5.

When in doubt, average across multiple designs: Without a clearly dominant hypothetical design—simple or complex, generic or specific—researchers may be best off trying several designs at once, and then triangulating results across them.

Collectively, our results add cautious, qualified optimism to a broader literature in social science that warns against leaning too heavily on easily measured proxies to estimate real behaviors. Hypotheticals appear quite useful in targeted cases, particularly to test the sign of treatment effects (albeit only one effect was negative in our sample). Further, we add to the psychological vignette design literature, by empirically comparing best practices with popular practices and finding—surprisingly—neither consistently dominated. In this way, our work also responds to recent calls for researchers to identify which features matter when generalizing from one context to another36,37, underscoring the need to gather evidence across features and samples at scale.

Limitations

It’s possible that our results were driven by the online population we sourced. Although we focused our recruiting on Prolific workers who shared traits with the participants in the real-world studies, their income and gender composition likely differed, along with other unobservable traits38. Relatedly, participants may not have fully understood our scenarios, although their uniformly high imaginability ratings suggest otherwise (see SI Section 7). Notably, these risks are shared by most hypothetical studies; overcoming them would have rendered our studies less representative of the practices we set out to examine.

Another possible limitation is that the features we decided to vary, or the field studies we selected to turn into hypotheticals, were not representative of the broader nudge literature. We welcome larger-scale research expanding both and note that, in the present research, we intentionally tied our hands in terms of which studies to select by following strict inclusion restrictions (SI Section 3a). For example, a broader examination across positive and negative effects would help disentangle whether hypotheticals truly detect the direction of nudge effects, or if our results were merely an artifact of treatments generally working in hypothetical scenarios. Similarly, extending our analysis to a set of studies with a wide range of effects—from very small to very large—and where participant attention to stimuli and target behaviors is low or high—would help test our theory around hypotheticals generally tempering more extreme effects.

Yet another fruitful extension to the present work would be to expand from our four variants to additional techniques such as cheap talk scripts (i.e., asking participants to avoid exaggerating), certainty questions (“How certain are you that you would actually do [behavior]?”), or honesty priming (e.g., unscrambling a sentence about honesty) as used in the field of economics39,40. Video and virtual reality might similarly enable more lifelike and ultimately predictive hypothetical behaviors. The large literature on contingent valuation (measuring value of non-market goods, typically environmental states) also provides some inspiration. The latter uses extensive details and pictures to make the nature of choices realistically vivid41. However, despite enormous resources and effort, methods for getting realistic estimates of contingent valuations remain quite contentious (such as in42,43,44). Given how essential hypotheticals are to behavioral science, further research into features that researchers can directly control—as well as real-world contexts better suited to the use of hypotheticals—will be critical for our field to build better proxies for real-world behavior change. The findings in this paper offer strong starting points for such investigations.

Conclusions

Many recent studies have documented that social science studies often fail to replicate—i.e., the same study run twice under ideally matched conditions yields substantively different results45,46,47. We should expect failures to generalize across studies to be even more frequent, especially when moving from a real to a hypothetical context, with necessarily different participants, incentives, and procedures. Discoveries that yield even modest improvements in our ability to reliably generalize from hypothetical to real contexts will represent a major contribution.

We conclude that hypothetical designs require thoughtful application by academics and practitioners interested in evaluating nudges. Our results suggest that hypotheticals—even the most simple, generic designs—may be a highly valuable tool for simple existence proofs. However, the magnitude of their estimates appear too noisy for more nuanced use in cost-benefit analyses, operational plans, or precise policy recommendations. More work is needed to identify when this tool can serve as a cost-effective alternative, and when researchers would be better off investing in real-world designs.

Data availability

All pre-registrations, study materials, and primary data are publicly available at the following link: https://researchbox.org/1992.

Code availability

All analysis scripts are publicly available at the following link: https://researchbox.org/1992.

References

Thaler, R. H. & Sunstein, C. R. Nudge: The Final Edition (Yale University Press, 2021).

Szaszi, B., Palinkas, A., Palfi, B., Szollosi, A. & Aczel, B. A systematic scoping review of the choice architecture movement: Toward understanding when and why nudges work. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 31, 355–366 (2018).

Mertens, S., Herberz, M., Hahnel, U. J. & Brosch, T. The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2107346118 (2022).

Saccardo, S., Li, C. X., Samek, A. & Gneezy, A. Nudging generosity in consumer elective pricing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 163, 91–104 (2021).

Dai, H. et al. Behavioural nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature 597, 404–409 (2021).

Giner-Sorolla, R. Science or art? How aesthetic standards grease the way through the publication bottleneck but undermine science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7, 562–571 (2012).

Camerer, C. F. & Hogarth, R. M. The effects of financial incentives in experiments: a review and capital-labor-production framework. J. Risk Uncertain. 19, 7–42 (1999).

Murphy, J. J., Allen, P. G., Stevens, T. H. & Weatherhead, D. A meta-analysis of hypothetical bias in stated preference valuation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 30, 313–325 (2005).

Schmidt, J. & Bijmolt, T. H. Accurately measuring willingness to pay for consumer goods: a meta-analysis of the hypothetical bias. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 48, 499–518 (2020).

Imai, T., Kang, M. J. & Camerer, C. F. When the eyes say buy: visual fixations during hypothetical consumer choice improve prediction of actual purchases. J. Economic Sci. Assoc. 5, 112–122 (2019).

FeldmanHall, O. et al. What we say and what we do: the relationship between real and hypothetical moral choices. Cognition 123, 434–441 (2012).

Gold, N., Colman, A. M. & Pulford, B. D. Cultural differences in responses to real-life and hypothetical trolley problems. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 9, 65–76 (2014).

Loomis, J. What’s to know about hypothetical bias in stated preference valuation studies?. J. Economic Surv. 25, 363–370 (2011).

Johansson-Stenman, O. & Svedsäter, H. Self-image and valuation of moral goods: Stated versus actual willingness to pay. J. Economic Behav. Organ. 84, 879–891 (2012).

Larson, R. B. Controlling social desirability bias. Int. J. Mark. Res. 61, 534–547 (2019).

Sheeran, P. & Webb, T. L. The intention–behavior gap. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 10, 503–518 (2016).

Conner, M. & Norman, P. Understanding the intention-behavior gap: the role of intention strength. Front. Psychol. 13, 923464 (2022).

Luo, Y., Li, A., Soman, D. & Zhao, J. A meta-analytic cognitive framework of nudge and sludge. R. Soc. Open Sci. 10, 230053 (2023).

Landy, J. F. et al. Crowdsourcing hypothesis tests: Making transparent how design choices shape research results. Psychol. Bull. 146, 451 (2020).

Huber, C. et al. Competition and moral behavior: a meta-analysis of forty-five crowd-sourced experimental designs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2215572120 (2023).

Aguinis, H. & Bradley, K. J. Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organ. Res. Methods 17, 351–371 (2014).

Eckerd, S., DuHadway, S., Bendoly, E., Carter, C. R. & Kaufmann, L. On making experimental design choices: discussions on the use and challenges of demand effects, incentives, deception, samples, and vignettes. J. Oper. Manag. 67, 261–275 (2021).

Freedman, G., Seidman, M., Flanagan, M., Green, M. C. & Kaufman, G. Updating a classic: a new generation of vignette experiments involving iterative decision making. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 1, 43–59 (2018).

Green, M. C. & Jenkins, K. M. Interactive narratives: processes and outcomes in user-directed stories. J. Commun. 64, 479–500 (2014).

Morales, A. C., Amir, O. & Lee, L. Keeping it real in experimental research—Understanding when, where, and how to enhance realism and measure consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 44, 465–476 (2017).

Rungtusanatham, M., Wallin, C. & Eckerd, S. The vignette in a scenario-based role-playing experiment. J. Supply Chain Manag. 47, 9–16 (2011).

Wason, K. D., Polonsky, M. J. & Hyman, M. R. Designing vignette studies in marketing. Australas. Mark. J. ((AMJ)) 10, 41–58 (2002).

Camerer, C. F. & Mobbs, D. Differences in behavior and brain activity during hypothetical and real choices. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 46–56 (2017).

Kang, M. J., Rangel, A., Camus, M. & Camerer, C. F. Hypothetical and real choice differentially activate common valuation areas. J. Neurosci. 31, 461–468 (2011).

Kang, M. J. & Camerer, C. F. fMRI evidence of a hot-cold empathy gap in hypothetical and real aversive choices. Front. Neurosci. 7, 104 (2013).

DellaVigna, S. & Linos, E. RCTs to scale: comprehensive evidence from two nudge units. Econometrica 90, 81–116 (2022).

Gomila, R. Logistic or linear? Estimating causal effects of experimental treatments on binary outcomes using regression analysis. J. Exp. Psychol.: Gen. 150, 700 (2021).

Lakens, D., Scheel, A. M. & Isager, P. M. Equivalence testing for psychological research: a tutorial. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 1, 259–269 (2018).

Funder, D. C. & Ozer, D. J. Evaluating effect size in psychological research: sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2, 156–168 (2019).

Gandhi, L., Manning, B. S. & Duckworth, A. L. Effect size magnification: no variable is as important as the one you’re thinking about—while you’re thinking about it. Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 09637214241268222. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214241268222 (2024).

Bryan, C. J., Tipton, E. & Yeager, D. S. Behavioural science is unlikely to change the world without a heterogeneity revolution. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 980–989 (2021).

Szaszi, B., Goldstein, D. G., Soman, D. & Michie, S. Generalizability of choice architecture interventions. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-025-00471-9 (2025).

Douglas, B. D., Ewell, P. J. & Brauer, M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 18, e0279720 (2023).

Champ, P. A., Moore, R. & Bishop, R. C. A comparison of approaches to mitigate hypothetical bias. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 38, 166–180 (2009).

De-Magistris, T., Gracia, A. & Nayga, R. M. Jr On the use of honesty priming tasks to mitigate hypothetical bias in choice experiments. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 95, 1136–1154 (2013).

Mitchell, R. C. & Carson, R. T. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: the Contingent Valuation Method (McGraw-Hill, 1989).

McFadden, D., Train, K. Contingent Valuation of Environmental Goods: A Comprehensive Critique. Edward Elgar: UK, 2017.

Whitehead, J. Review of Contingent Valuation of Environmental Goods: A Comprehensive Critique. Edited by Daniel McFadden and Kenneth Train (2017): An Update. Working Papers 24-17, Department of Economics, Appalachian State University (2024). https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:apl:wpaper:24-17.

Ann-Chyi, T. & Sheau-Ting, L. Methodological influences on ecosystem valuation: a systematic review of contingent valuation studies. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 13, 449–467 (2024).

Open Science Collaboration. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349, aac4716 (2015).

Camerer, C. F. et al. Evaluating replicability of laboratory experiments in economics. Science 351, 1433–1436 (2016).

Camerer, C. F. et al. Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 637–644 (2018).

Beshears, J., Dai, H., Milkman, K. L. & Benartzi, S. Using fresh starts to nudge increased retirement savings. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 167, 72–87 (2021).

Polman, E., Ruttan, R. L. & Peck, J. Using curiosity to incentivize the choice of “should” options. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 173, 104192 (2022).

Myers, E. & Souza, M. Social comparison nudges without monetary incentives: Evidence from home energy reports. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 101, 102315 (2020).

Kristal, A. S. & Whillans, A. V. What we can learn from five naturalistic field experiments that failed to shift commuter behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 169–176 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Aaron Caldwell for consulting with us on minimal effects and replication testing; Angela Duckworth, Katherine Milkman, and Richard Thaler for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript; and Nicole Frankel, Nicole Grabel, and Iman McPherson for user testing our hypothetical survey designs. We thank Wharton AI Analytics and the Wharton Behavioral Lab for funding support. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors collaborated on the conceptualization, methodology, and editing of the paper. L.G. and A.K. jointly developed the study materials and collected data. L.G. secured funding, managed the project, conducted the formal analysis, and drafted the initial paper. A.K. validated all analyses. C.C.C. and D.J.W. jointly supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks Laurens C. van Gestel and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Troby Ka-Yan Lui. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gandhi, L., Kiyawat, A., Camerer, C. et al. Hypothetical nudges provide directional but noisy estimates of real behavior change. Commun Psychol 3, 158 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00339-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00339-x