Abstract

Cancer-related cognitive impairment is common and distressing. Research has primarily focused on differences in mean-level performance on laboratory cognitive tasks, but recent work has investigated within-person fluctuations, or intraindividual variability (IIV), in performance on laboratory-based tasks. The present study of ambulatory cognitive assessments in daily life evaluated whether cancer survivors differed from a comparison sample in mean-level performance, IIV, and within-group heterogeneity, as well as change in mean performance and IIV across the study. Breast cancer survivors (N = 47, Mage = 52.9) and a comparison sample (N = 105, Mage = 51.8) completed intensive longitudinal design protocols involving smartphone-based cognitive assessments up to 5 times per day for 2 weeks to measure spatial working memory, working memory updating, and processing speed. Participants were female and in the United States. Bayesian mixed-effect location-scale models were conducted. Survivors had better mean-level performance on cognitive tasks, and both groups showed improvements across the study. Survivors showed greater IIV in processing speed and working memory updating, but there was no credible evidence for a difference in spatial working memory. IIV also changed across the study, such that both groups became less consistent in processing speed and working memory updating, and survivors became more consistent in spatial working memory. There was little evidence of group differences in within-group heterogeneity. Our findings indicate that IIV, as a potential marker of instability or sensitivity to contextual factors, may be an important index in the study of cancer-related cognitive impairment. These results highlight opportunities to use intensive longitudinal designs to consider indices beyond individual differences in mean-level performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) refers to impairments in performance-based and self-reported cognitive functioning related to cancer and its treatment1,2,3. Much of the existing work on CRCI has focused on average performance on laboratory-based cognitive tasks. Among people diagnosed with breast cancer, long-term deficits on multiple domains of cognition have been observed4,5,6. Average cognitive performance, however, is often calculated from a series of attempts at the same task within a single laboratory session. Two participants who complete a task may have the same average score, but one may perform quite consistently on each attempt, while the other’s performance may vary quite a bit across attempts. Despite the same average performance, these participants would have different levels of intraindividual variability (IIV), which refers to the degree of consistency in an individual’s performance across time.

The understanding that cognitive performance varies between individuals as well as within individuals has gained increasing attention in research among older adults, both due to concerns around the inadequacy of a single measurement for understanding cognitive performance due to IIV7,8, as well as literature linking IIV to health outcomes such as Mild Cognitive Impairment and dementia9,10,11. Incorporating IIV as an index of functioning makes clear the potential effects of relying on a single or few assessments when drawing conclusions about cognitive performance (e.g., a clinic visit that happens to occur on a “good” day in which the person displays their best performance vs. one that occurs on a “bad” day in which the person displays their worst performance). IIV also presents the opportunity to identify contexts- or moments-of-risk which predict these “good” and “bad” days (i.e., following optimal sleep, in noisy environments, at times a person is stressed or fatigued). In the context of breast cancer and CRCI, previous findings indicate that IIV may be more sensitive than measures of average cognitive performance when attempting to detect group differences between controls and breast cancer patients and survivors, although only a few studies to date have included IIV12,13,14,15,16.

Practice effects, sometimes described as reactivity or learning effects, refer to the understanding that performance on cognitive tasks often improves with repeated exposure to the task. Although practice effects are often conceptualized primarily as a nuisance that should be controlled for when attempting to understand cognitive performance data17,18, they are increasingly recognized as a potential indicator of cognitive ability in their own right19,20,21. For example, prior research has indicated that breast cancer patients’ and survivors’ ability to benefit from practice effects in cognitive tasks may be attenuated in comparison to controls15,22. The existing literature in this area has investigated practice effects within and across laboratory sessions, which points to the importance of understanding not just how participants perform on average, but how quickly and to what degree they benefit from practicing a cognitive task.

Importantly, the prior literature on CRCI mostly relies on laboratory assessments of cognitive performance. Cognitive performance can also be measured in daily life using ambulatory assessments23. In studies that use ambulatory assessment, participants are prompted to complete study tasks at various moments throughout the day, typically through mobile devices such as smartphones. This study design allows for the repeated measurement of performance on cognitive tasks in participants’ natural environment, resulting in multiple observations per day across multiple days for each participant. This approach allows us to index IIV over longer periods of time than previous literature that has examined IIV among breast cancer survivors in laboratory settings, which consists of a much shorter span of time. Measuring cognition in the settings of participants’ daily lives, as opposed to a laboratory or clinic, can enhance the ecological validity of findings24. This may be particularly relevant for cancer survivors, whose cognitive differences are relatively subtle and do not necessarily meet the threshold of cognitive impairment or dementia that the laboratory-based tasks were originally developed to measure25.

In our own work, we have used ambulatory cognitive assessments among breast cancer survivors to understand both individual differences, or between-person differences, as well as within-person processes. With respect to between-person differences, we have found that cancer survivors reported more frequent memory lapses compared to those without a history of cancer, and this was associated with negative affect26. With respect to within-person processes, we have reported that processing speed was slower when women reported greater fatigue than usual27, and that the memory lapses reported by cancer survivors were related to their task-based cognitive performance28. These previous findings draw from the same dataset used in the present study.

The present study examined CRCI by comparing several indices of cognitive performance among breast cancer survivors and a sample of participants without a history of cancer, both in the United States. The models we use allow us to test for five group differences between the survivors and comparison participants, which can address the following research questions:

-

1)

Group differences in mean performance on each of the cognitive tasks: on average, do breast cancer survivors perform better or worse than comparison participants?

-

2)

Group difference in between-person variability on mean performance: on average, do breast cancer survivors perform more similarly or differently to each other, in comparison to how similarly comparison participants perform to other comparison participants?

-

3)

Group differences in IIV on task performance: do breast cancer survivors demonstrate more or less consistency in their performance across observations than comparison participants?

-

4)

Group differences in practice effects on mean performance: on average, does breast cancer survivors’ performance improve more quickly or more slowly than comparison participants'?

-

5)

Group difference in the relation between time and IIV: do breast cancer survivors become more or less consistent over time, and does this differ from comparison participants?

Figure 1 provides a guide to illustrate group differences in mean performance, group differences in between-person variability, and group differences in IIV visually. Each panel presents a simulated time series of data of individuals from two groups, Group 1 (triangles) and Group 2 (circles). Each individual is depicted in a different color, with their respective colored shape representing their cognitive performance (y axis) at a given observation (x axis) across the study.

These two panels present simulated data to illustrate key concepts in this analysis, specifically a difference in grand mean, within group variability, and intraindividual variability in performance on a cognitive task across ten observations. Group 1 is indicated by blue triangles (one participant is light blue, and the other darker blue), and Group 2 is indicated by pink circles (one participant is lighter pink, and the other darker pink). A full description of the figure is in the text.

(1) Group difference in grand mean (Fig. 1a): The bold dashed lines represent the mean for each group; here, we can see a difference in the group means, such that the Group 1 (triangle) mean is greater than the Group 2 (circle) mean. (2) Group difference in between-person variability: The dot-dash lines represent individual participant means within each group; here, there is less between-person variability in Group 1, because the participant means are closer to each other and to the group mean than in Group 2. (3) Group difference in intraindividual variability (IIV): Finally, we can also see that there is greater IIV in Group 2 than in Group 1, because in Group 2, each participant’s individual observations demonstrate greater inconsistency, or greater variability around their own mean. In contrast, the individual observations of participants in Group 1 have less variability around their own means. Please note that IIV may refer to inconsistency both within a single session of cognitive testing as well as inconsistency in performance between sessions12,29. As shown here, we use IIV to refer to inconsistency between sessions or observations.

In Fig. 1b, we observe a different pattern of results. (1) Group difference in grand mean: As in Fig. 1a, we observe that the Group 1 (triangle) mean is greater than the Group 2 (circle) mean. (2) Group difference in between-person variability: In Fig. 1b, Group 2 has less between-person variability, because the participant means are closer to each other and to the group mean than in Group 1. (3) Group difference in intraindividual variability (IIV): In Fig. 1b, Group 1 has greater IIV because the individual observations of each participant have greater variability around the participant mean than in Group 2.

For the final two indices, we reference and expand upon Fig. 1. (4) Practice effects on mean performance: Whereas Fig. 1 shows no practice effects (i.e., the lines representing group and participant means have a slope of 0), we expect that participants in our study will demonstrate improved performance across observations and will therefore have a non-zero slope. (5) Practice effects on IIV over time: whereas Fig. 1 shows consistent IIV over the course of the study, in the present study we ask whether the individual data points will begin to cluster more tightly around the trendline for average performance over the course of the study (decreased IIV over time), or whether these individual observations may become more dispersed (increased IIV over time).

To summarize, this study uses ambulatory cognitive data to investigate several distinct aspects of cognitive performance in cancer survivors and a comparison sample, providing an extensive and ecologically valid investigation of possible indicators of CRCI. We hypothesized that survivors would show worse performance, on average, on each ambulatory cognitive task relative to comparison participants. We further hypothesized that survivors would show greater IIV on each task relative to comparison participants. Our analyses for group differences in between-person variability and practice effects on both mean performance and IIV were exploratory.

Methods

Participants

Breast cancer survivors

Breast cancer survivors were recruited from the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, as part of the Breast Cancer Survivors Study27. Participants were eligible if they (1) were age 18 or older; (2) had not been diagnosed with and showed no apparent neurological disorders such as dementia or psychosis that would interfere with study procedures; (3) spoke and read English; (4) had no history of cancer other than breast cancer or basal cell skin carcinoma; (5) received a minimum of four cycles of chemotherapy for Stage 0, I, or II breast cancer at Moffitt Cancer Center; (6) completed treatment 6–36 months before the start of the study; and (7) had no recurrence of breast cancer. Participants were identified through a review of medical records and appointment schedules in compliance with HIPAA guidelines. Of the 52 breast cancer survivors who expressed interest in the study and provided informed consent, 47 completed EMA procedures and are the focus of the paper here. All participants were identified as female based on their medical records. Study procedures for the breast cancer survivors study were approved by the Moffitt Cancer Center and University of South Florida Institutional Review Boards (IRB).

Comparison Sample

A comparison sample was drawn from a larger study of community-dwelling adults who were recruited from registered voter lists in the Bronx, New York30. This sample consisted of adults who were 25–65 years old, ambulatory, and free of visual impairments that would hinder them from operating the study smartphone. Of the 1007 participants contacted by phone for the larger study, 51% declined, with 80% stating that they were not interested. A full overview of recruitment and enrollment for this study is provided by Scott et al.28. To create the comparison sample for the current study, we identified a subsample of participants who were 40–64 years old and described themselves as female (participants were asked to indicate their sex as male or female). Three participants from this comparison sample reported a history of cancer diagnosis in a self-reported medical history questionnaire and were thus excluded from the comparison sample. One other participant completed only nine ambulatory surveys and was also excluded due to low compliance. Study procedures for the comparison sample study were approved by the Einstein College of Medicine IRB. Data analysis was approved by the Stony Brook University IRB. Previous publications using data from the comparison study are listed on the study’s OSF site. One previous study has used self-report data from this subset of female participants26, but this is the first analysis of this subset’s performance on cognitive tasks as compared to the breast cancer survivors sample. The present analysis was not pre-registered.

Procedure

In both the breast cancer survivor and the comparison sample studies, participants completed an in-person laboratory visit before the start of the ambulatory assessment. In this visit, participants provided informed consent, completed self-report questionnaires including demographic information, and completed a battery of neuropsychological tests. Participants were then trained to use the study-provided smartphones, on which a research app had been installed, which launched the study surveys and ambulatory cognitive measures. Participants practiced using the smartphones during the in-person laboratory visit to acclimate to the user interface of the research app.

Participants of the breast cancer study were instructed to return home and begin the study the following day. For the next 14 days, these participants were prompted 5 times per day to complete brief ambulatory surveys and cognitive assessments. In the comparison sample, participants also completed up to five ambulatory surveys per day. Prompts in both samples were pseudo-random.

There were differences in the procedure, in that breast cancer participants only visited the research offices once for the baseline assessments and smartphone device training, and they returned their study smartphones via prepaid mailers. Comparison participants visited the research offices three times, with baseline assessments spread across a smartphone device training visit, a check-up visit ~2 days later, and a visit after 14 days in order to return the device and complete other in-person assessments. As a result, comparison participants completed more than 14 study days and therefore completed more observations, on average, than survivors. Because practice effects are relevant to the phenomena of interest, we account for the different study lengths by analyzing only the first 70 observations from each comparison participant to harmonize the two datasets.

In both studies, participants’ responsiveness to the prompts was monitored throughout the study period, and study staff completed check-in calls midway through the studies to help ensure that participants were responding to the prompts. Participants were compensated for their participation and received additional bonuses for completing 80% of assessments during the study period. Data for the breast cancer survivors study were collected from August 2015 to October 2016, and data for the comparison sample were collected between July 2012 to August 2015.

Ambulatory assessment session duration

In both studies, participants completed the cognitive tasks following relatively brief self-report survey questions about psychological constructs relevant to the goals of their respective study teams (e.g., affect, stressors; see Small et al.27 for details on the survivor sample; see Scott et al.30 for details on the comparison sample). These psychological constructs are not the focus of the present research. On average, breast cancer survivors spent about 2.74 minutes (SD = 0.71, range = 1.37–4.62) completing self-report survey questions on the smartphone before the cognitive tasks. In the comparison study, which included additional self-report questions, participants spent an average of 3.42 minutes (SD = 1.34, range = 1.50–9.38) completing that study’s self-report survey questions before the cognitive tasks. Participants in both studies were prompted by an audible noise to complete the ambulatory surveys and cognitive tasks at pseudo-random times throughout the day. The timing of assessments in both studies varied from day to day to prevent participants from anticipating the exact timing of assessments. Additionally, during the training session, participants indicated their typical waking time so that assessments could be delivered during waking hours.

Measures

Demographic predictors

Prior to the EMA period, all participants completed demographic questionnaires to provide their age, race (Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, White, Other, or More than One) and ethnicity (Hispanic or not Hispanic), education, menopause status, household income, work status, and marital status. Additionally, for survivors, medical record reviews were conducted to collect cancer-specific information. Supplementary Table 1 provides descriptive information on survivors’ cancer and treatment.

Ambulatory cognitive tasks

Participants in both studies were prompted five times per day to complete ambulatory cognitive tasks designed to measure spatial working memory, working memory updating, and processing speed24.

To account for practice effects across the study, we created a variable to index the session number within the study. This was a within-person variable, with the first session coded as 0 and each subsequent session increasing by one (for a maximum count of 70 sessions).

-

I.

Processing speed: Symbol search task. This task was based on a digit-symbol task and assessed participants’ processing speed. On each trial, participants were presented with three pairs of symbols on the top of the screen and two pairs of symbols on the bottom of the screen. Participants were instructed to touch the symbol pair on the bottom of the screen that matched one of the pairs on the top of the screen, and they responded as quickly as possible. Participants completed 12 trials at each assessment with a 200 msec delay between each trial. The outcome for this task was the number of correct responses per minute. Lower scores indicated worse performance.

-

II.

Working memory updating: flip-back task. This was a card-matching task that assessed working memory updating. The task included a practice phase and a testing phase. In the practice phase, participants were presented with three face-up playing cards and were asked whether the target card in the rightmost position matched the test card in the leftmost position. After participants responded, there was a 500 msec delay before the cards shifted one position to the left such that the test card in the leftmost box disappeared, the middle card shifted to become the new test card (in the leftmost position), the rightmost card shifted to become the middle card, and a new card appeared in the rightmost position to become the new target card. The practice phase lasted for 10 trials, after which participants began the testing phase. In the testing phase, each card was turned face down and shifted one position to the left. The new target card appeared face-up in the rightmost position, and participants indicated whether this card matched the test card in the leftmost box. After the participant’s response, the target card was flipped face down, and all cards shifted one position to the left in an animation. This task, therefore, required participants to remember the identity of each card as it shifted two positions. If participants selected the incorrect option, all cards were flipped face-up to provide feedback and then were flipped back over to a face-down position. The testing phase was 12 trials, and the outcome for this task was proportion correct per minute on a scale of 0-10, such that a score of 10 indicates 100% correct responses. Lower scores indicated worse performance.

-

III.

Spatial working memory: Dot memory task. This task assessed spatial working memory. During the encoding phase, participants were presented with a 5 × 5 grid in which three cells contained a red dot. They viewed this screen for 3 seconds, and they were instructed to remember the locations of the red dots. After this encoding phase of the trial, participants were presented with a distractor task in which an array of Es and Fs appeared on the screen. The distractor task lasted for 8 seconds, and participants were instructed to touch all the Fs on the screen. In the final phase of the trial, participants were presented with an empty 5 × 5 grid and were instructed to touch the three cells that contained the red dots from the encoding phase. Participants completed two trials of this task at each assessment. The outcome for this task was Euclidean error distance summed across trials for each assessment. Higher scores indicated worse performance (i.e., greater error distance).

Statistical approach

Prior to our main analysis, we were interested in determining whether survivors and the comparison sample differed with respect to key demographic variables. We used a t test for comparing mean age, chi-squared tests of independence for categorical demographic variables, and a Wilcoxon rank-sum test to test for a difference in the income categories across groups. For effect size, we report Cohen’s d (t test), phi (chi-squared test), and r (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) as well as the 95% confidence intervals. All tests were two-sided and used an alpha of 0.05 to indicate a significant difference between the groups.

Prior to the analysis reported in the main text of this paper, we conducted initial analyses using the software Mixed Model Analysis With Intensive Longitudinal Data (MixWILD)31. The output of these models can be found in Supplementary Table 3. In this initial analysis, some of our key tests resulted in null effects or had small effect sizes. Additionally, we observed that two of the learning effects across the study would be better captured using an exponential learning curve, as opposed to a linear approach. Given our interests in understanding ways in which survivors may be different from or similar to their age-mates without a cancer history, we shifted to a Bayesian framework presented in the main text to better capture the learning effects and to be able to make more informative statements around what conclusions we could draw from our findings.

Mixed-effects location scale models

For the primary analysis of group differences in indices of cognitive performance, we used Bayesian mixed-effects location scale models (MELS) with random scale to assess group differences between survivors and comparison participants32. For processing speed and working memory updating, we accounted for practice effects using the nonlinear approach described by Williams et al.21. This means that we modeled learning for these variables not as a continuous linear process, but rather as a process of exponential gains in which an initially steep slope decays towards an asymptote, at which point additional improvement over time is minimal. This approach means that we report findings both for the intercept (alphaMu) as well as the asymptote (betaMu) for these two outcome variables.

For spatial working memory, we accounted for linear learning effects in our models using the approach described by Williams et al33. Due to the distribution of the outcome variable, we used a hurdle gamma model, whereas the models for the other outcome variables used a Gaussian distribution (see posterior predictive check in Supplementary Fig. 1). Importantly, the hurdle gamma approach models values of zero as a separate process from non-zeros. This means that we model the correct responses as a different process from the incorrect responses. In the hurdle portion, group differences reflect differences in whether a correct response occurs or not, and group differences in the gamma portion reflect differences in the degree of error among incorrect responses.

Rather than calculating IIV directly from the data using intraindividual standard deviation (iSD) or coefficient of variation (CoV) as has been done in previous literature on this topic16, we directly modeled IIV using the MELS model. The MELS model is the modern approach for modeling IIV because it overcomes several limitations of traditional approaches (iSD, CoV, mean of the squared successive differences (MSSD)), including issues with nested data structures and uncertainty in the estimates32,33. A benefit of the MELS model is that it allows us to more straightforwardly model how IIV changes over time, along with predictors of that change. Additionally, the MELS model allowed for the evaluation of means (location) and IIV (scale) simultaneously. We elected this approach because it better mapped onto the aims of the study, and it is currently considered the state-of-the-art approach in the methodological literature.

For tests of mean performance (fixed effects), the following variables were included as predictors: cancer history (0 = comparison participant; 1 = survivor), education (0 = no college degree; 1 = college degree), and age (continuous and centered on age 52). For exponential models (working memory updating and processing speed), covariates only applied to the asymptote (betaMu). Education and age were included because the association between these characteristics and cognitive performance is well-established. Race was not included in this model because of overlap with the cancer history variable (i.e., most survivors were non-Hispanic white, henceforth white, and most comparison participants were non-white). Cancer history was the only predictor included in the tests of group differences in within-person and between-person variability. All final models included random intercepts and slopes in the mean and within-person models, as well as random intercepts in the between-person model. In the hurdle portion of the hurdle gamma model for spatial working memory, only cancer history and random intercepts were included.

Software and specifications

All models were conducted in R using the brms package34, and visuals were generated using the posterior and ggplot2 packages. Following the primary analysis, the LLM ChatGPT (v. 4.5) was used to assist with editing and generating R code for summarizing and visualizing the posterior distribution. All models used default priors and four chains with either 10,000 iterations (spatial working memory; first 5000 used as burn-in per chain) or 20,000 iterations (processing speed and working memory updating; first 10,000 used as burn-in per chain). This approach provided posterior distributions with 20,000 (spatial working memory) and 40,000 (processing speed and working memory updating) samples for inference. The processing speed and working memory updating models were initially run with 10,000 iterations per chain, but required additional iterations in order to reach the desired convergence. We classify strong evidence as a probability of direction >95% and weak evidence as a probability of direction between 90 and 95%.

To facilitate model convergence, we transformed the index of observation by dividing it by 10. To aid in interpretation, we chose not to back-transform this variable because the estimates for change across individual observations are very small. Therefore, all coefficients associated with time (observations) represent the change in performance for every ten observations. Additionally, the model for working memory updating would not converge when we allowed for correlated random effects for the rate of exponential decay (gammaMu) and the sigma intercept (betaSc), thus we constrained these random effects to be uncorrelated to permit model convergence. Convergence of the Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) algorithm was confirmed for all models by visual inspection of trace plots and ensuring that all rhat values were <1.01. All effective sample sizes were >1000.

Following the analysis with the full sample, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that included only participants with >56 observations (based on a common threshold in EMA research of 80% compliance) to determine whether our results were similar after excluding participants with low compliance. This analysis excluded seven survivors and nine comparison participants, for a total of 16 participants excluded.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Demographic characteristics of survivors and comparison participants are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between survivors and comparison participants in age, education, current work status, and menopausal status. The two groups of participants differed in marital status, income, and race. Relative to the comparison sample, more survivors were married or cohabitating, survivors reported higher income, and survivors were more likely to be white.

Breast cancer survivors completed a mean of 61.89 sessions (SD = 6.54, range = 41–69), and comparison participants completed a mean of 66.97 sessions (SD = 7.53, range = 38–70). This difference was statistically significant (t(101.13) = 4.22, p < 0.001, d = 0.85 [0.81, 0.90]). White participants also completed fewer EMA prompts than non-white participants (t(70.41) = 2.73, p = 0.01, d = 0.50 [0.13, 0.86]). We found no statistically significant evidence that other demographic variables were associated with compliance.

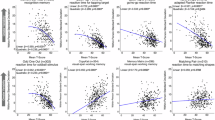

Final results from all models are presented in Table 2. For interpretation of time-related variables, please note that observation was rescaled so that 1 unit change in observation in the model represents 10 observations (i.e., the range of observations in the model is 0–7; the range of observations in the study is 0-70). See Fig. 2 for a visual representation of mean performance and IIV for all outcome variables over the course of the study. An alternate visualization that more readily demonstrates group comparisons can be found in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Predicted values for the mean and IIV, computed from the posterior distribution. Bold lines represent the group, and thinner lines represent random effects. The processing speed model is based on 9358 observations from 152 participants, the working memory updating model is based on 9312 observations from 152 participants, and the spatial working memory model is based on 9332 observations from 152 participants.

Processing speed

A higher score on this task indicates better performance.

1) Group difference in grand mean. We found strong evidence that survivors had better performance than the comparison group both at the intercept (M = 4.44, SE = 0.81, [3.10, 5.77], PD = 100%) and at the asymptote (M = 9.38, SE = 4.29, [3.76, 17.42], PD = 100%). We observed strong evidence for a relation between age and mean performance (M = −0.11, SE = 0.06, [−0.20, −0.01], PD = 97%), such that each additional year of age was associated with worse performance. We also observed strong evidence for a relation between education and mean performance, such that participants with a college degree performed better (M = 1.24, SE = 0.66, [0.15, 2.32], PD = 97%).

2) Group difference in between-person variance. We found weak evidence for a group difference on between-person variability around the group mean at the intercept (M = −0.89, SE = 0.65, [−2.14, 0.43], PD = 91%), such that comparison participants’ individual means were more dispersed around the group mean (i.e., the comparison group demonstrated less homogeneity). We found little credible evidence for a group difference in between-person variance at the asymptote (M = 1.05, SE = 2.18, [−3.27, 5.71], PD = 71%).

3) Group difference in intraindividual variability (IIV). We found strong evidence that IIV in both groups differed from zero (Comparison: M = 1.25, SE = 0.03, [1.20, 1.31], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = 1.42, SE = 0.04, [1.33, 1.51], PD = 100%). We also found strong evidence that survivors had greater IIV than the comparison group (M = 0.17, SE = 0.06, [0.07, 0.26], PD = 100%). Because IIV was modeled linearly, this value represents the group difference at the intercept.

4) Group difference in mean practice effects. We found strong evidence for practice effects, such that both comparison participants and survivors had an initial slope that was greater than zero (Comparison: M = 2.49, SE = 0.43, [1.74, 3.42], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = 2.04, SE = 0.82, [0.90, 4.04], PD = 100%). We observed little credible evidence of a group difference in this initial rate of improvement (M = −0.45, SE = 0.92, [−1.97, 1.66], PD = 72%).

We also assessed a metric of the rate of decay towards the asymptote, where greater values indicate a more rapid decline from the value of the intercept towards the asymptote (Comparison: M = −1.22, SE = 0.22, [−1.60, −0.88], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = −1.91, SE = 0.57, [−3.11, −0.90], PD = 100%). We observed little credible evidence that the groups differed in their rate of decay towards the asymptote (M = −0.69, SE = 0.61, [−1.75, 0.26], PD = 87%). Restated, we found little credible evidence that the groups differed in how quickly they approached their maximum level of performance.

5) Group difference in IIV across observations. We found strong evidence for a relation between time and IIV in both comparison and survivors, such that participants became less consistent as the study progressed (Comparison: M = 0.04, SE = 0.01, [0.03, 0.05], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = 0.03, SE = 0.01, [0.01, 0.04], PD = 100%). We found little credible evidence for an interaction between group and observation with respect to IIV (M = −0.01, SE = 0.01, [−0.03, 0.01], PD = 83%). The relation between time and IIV was modeled linearly.

Working memory updating

A higher score on this task indicates better performance.

1) Group difference in grand mean. We found strong evidence that survivors performed better on the task at the intercept (M = 0.49, SE = 0.28, [0.04, 0.94], PD = 96%) and weak evidence for better performance among survivors at the asymptote (M = 0.99, SE = 0.80, [−0.26, 2.36], PD = 90%). We observed strong evidence for a relation between age and mean performance (M = −0.06, SE = 0.02, [−0.09, −0.03], PD = 100%), such that each additional year of age was associated with worse performance. We also found weak evidence for a relation between education and mean performance, such that participants with a college degree performed better (M = 0.34, SE = 0.25, [−0.07, 0.74], PD = 92%).

2) Group difference in between-person variance. We found little credible evidence for a group difference in between-person variability around the group mean at the intercept (M = −0.06, SE = 0.22, [−0.47, 0.39], PD = 62%) or the asymptote (M = 0.31, SE = 0.47, [−0.56, 1.30], PD = 74%).

3) Group difference in intraindividual variability (IIV). We found strong evidence that IIV in both groups differed from zero (Comparison: M = 0.17, SE = 0.04, [0.11, 0.23], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = 0.32, SE = 0.05, [0.22, 0.43], PD = 100%). We found strong evidence that survivors had greater IIV than the comparison group (M = 0.15, SE = 0.06, [0.05, 0.26], PD = 99%). Because IIV was modeled linearly, this value represents the group difference at the intercept.

4) Group difference in mean practice effects. We found strong evidence for practice effects, such that both comparison participants and survivors had an initial slope that was greater than zero (Comparison: M = 1.45, SE = 0.15, [1.17, 1.78], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = 1.51, SE = 0.17, [1.21, 1.86], PD = 100%). We observed little credible evidence of a group difference in this initial rate of improvement (M = 0.06, SE = 0.23, [−0.38, 0.51], PD = 61%).

We also assessed a metric of the rate of decay towards the asymptote, where greater values indicate a more rapid decline from the value of the intercept towards the asymptote (Comparison: M = −1.41, SE = 0.12, [−1.61, −1.22], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = −1.45, SE = 0.15, [−1.77, −1.18], PD = 100%). We found little credible evidence that the groups differed in their rate of decay towards the asymptote (M = −0.04, SE = 0.19, [−0.36, 0.27], PD = 57%). Restated, we found little credible evidence that the groups differed in how quickly they approached their maximum level of performance.

5) Group difference in IIV across observations. We found strong evidence for a relation between time and IIV in both comparison and survivors, such that participants became less consistent with time (Comparison: M = 0.09, SE = 0.01, [0.08, 0.10], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = 0.09, SE = 0.01, [0.07, 0.11], PD = 100%). We found no credible evidence of an interaction between group and observation with respect to IIV (M = 0.00, SE = 0.01, [−0.02, 0.02], PD = 52%). The relation between time and IIV was modeled linearly.

Spatial working memory

Spatial working memory was modeled linearly, so where we previously reported group differences at the intercept and asymptote, here we report them only at the intercept. Importantly, for spatial working memory, correct responses were modeled separately from incorrect responses; all outcomes except for the group difference in grand mean represent incorrect responses only. A lower score on this task indicates better performance, and a zero represents a correct response.

1) Group difference in grand mean. We found strong evidence that survivors had a higher probability of a correct response than comparison participants (M = 0.08, SE = 0.03, [0.03, 0.14], PD = 100%; see Fig. 3). For incorrect responses, we found weak evidence that survivors performed better than comparison participants (M = −0.07, SE = 0.06, [−0.16, 0.02], PD = 90%). We found weak evidence of a relation between age and mean performance, such that each additional year of age was associated with better performance (M = 0.00, SE = 0.00, [−0.01, 0.00], PD = 93%). We also found weak evidence for a relation between education and mean performance, such that participants with a college degree performed better (M = −0.03, SE = 0.02, [−0.07, 0.01], PD = 92%).

Predicted values for the hurdle estimate, computed from the posterior distribution. Large opaque circles represent the estimate for the group. Error bars represent a 95% credibility interval for the group. Smaller translucent circles represent random effects. The spatial working memory model is based on 9332 observations from 152 participants.

2) Group difference in between-person variance. We found little credible evidence for a group difference in between-person variability around the group mean (M = 0.01, SE = 0.05, [−0.07, 0.11], PD = 61%).

3) Group difference in intraindividual variability (IIV). We found strong evidence that IIV in both groups differed from zero (Comparison: M = 2.20, SE = 0.06, [2.08, 2.32], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = 2.31, SE = 0.11, [2.10, 2.52], PD = 100%). We found little credible evidence for a group difference in IIV (M = 0.10, SE = 0.12, [−0.14, 0.35], PD = 80%).

4) Group difference in mean practice effects. We observed strong evidence for a practice effect in both groups, such that participants improved over the course of the study (Comparison: M = −0.02, SE = 0.00, [−0.03, −0.01], PD = 100%; Survivor: M = −0.04, SE = 0.01, [−0.06, −0.03], PD = 100%). We also observed strong evidence for an interaction between group and observation, such that survivors improved more than the comparison group over the course of the study (M = −0.02, SE = 0.01, [−0.04, −0.01], PD = 98%). For this outcome variable, practice effects were modeled linearly, so this finding indicates that the survivor group had a steeper linear slope than the comparison group.

5) Group difference in IIV across observations. We found little credible evidence for a relation between time and IIV in the comparison sample (M = −0.01, SE = 0.01, [−0.04, 0.02], PD = 71%). We found strong evidence for a relation between time and IIV among survivors, such that survivors became more consistent over the course of the study (M = −0.07, SE = 0.02, [−0.11, −0.02], PD = 100%). Thus, there was strong evidence for an interaction between group and observation (M = −0.06, SE = 0.03, [−0.11, 0.00], PD = 98%). The relation between time and IIV was modeled linearly.

Our sensitivity analyses that excluded participants with fewer than 56 observations broadly replicated our key findings. See Supplementary Table 2 for full model output.

For a visual summary of the overall results, see Fig. 4.

“Strong” and “weak” refer to both the probability of direction (>95% vs. 90–95%) and the convergence of multiple pieces of evidence (e.g., in working memory updating, we saw strong evidence for a grand mean difference at the intercept but weaker evidence at the asymptote, so this is characterized as “weak” evidence).

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed ambulatory cognitive data using Bayesian linear and nonlinear MELS models to characterize five indices of cognitive performance among breast cancer survivors and a group of participants without a cancer history. Our findings point to the benefits of considering both multiple indices and multiple domains of cognitive performance to better understand how CRCI may present in the lives of breast cancer survivors.

Grand mean performance

Contrary to our hypotheses, we found evidence that survivors had better grand mean performance than comparison participants across all three cognitive domains, with the strongest evidence for processing speed. We interpret the better, or at least comparable, performance of the survivors in light of the group demographic differences and cumulative disadvantage theory35; CRCI is relatively subtle and perhaps cannot surmount a lifetime of other differences in relative advantages or disadvantages.

Whereas the comparison sample was drawn from a study that used systematic probability sampling of a socioeconomically, racially, and ethnically diverse area, survivors were recruited from a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. The group differences in both race and ethnicity (which can serve as proxies for exposure to interpersonal and systemic racism), as well as income, suggest that the survivor and comparison groups may have a lifetime of differential access to resources, particularly healthcare. The difference in income between these groups may, in fact, be underestimating their actual material differences, because the relative cost of living is higher in New York City than in the area surrounding Tampa, Florida.

Without a more in-depth understanding of the life histories and current circumstances of the participants in both groups, it is inadvisable to overinterpret the finding of better average performance among survivors. Cancer, however, does not solely affect those who are high SES or white, which means that future studies are needed that include a more representative sample of breast cancer survivors.

Between-person variability in mean performance

We observed little credible evidence for a difference in the dispersion of participant means around the group mean, except for processing speed at the start of the study, where survivors were less dispersed (i.e., more similar to each other) than comparison participants. Thus, despite the more homogeneous demographics among the survivor sample described above, we were unable to conclude whether the groups substantially differed in the levels of heterogeneity among participants.

Average IIV

We found strong evidence for group differences in IIV for processing speed and working memory updating, but there was little credible evidence for a difference between groups for spatial working memory. For processing speed and working memory updating, the survivors had higher IIV as predicted. These findings lend support to the hypothesis that IIV may be more informative than average performance at detecting subtle differences between survivors and comparison participants15.

Mean practice effects

On average, participants improved on each task over repeated observations. We observed strong evidence for a group difference in mean practice effects in spatial working memory, such that survivors showed greater linear improvement with practice than comparison participants.

IIV in relation to time-in-study

We observed a change in IIV over the course of the study in processing speed and working memory updating, such that participants in both samples became slightly less consistent over time. With respect to spatial working memory, we found little credible evidence that IIV changed over the course of the study in comparison participants, whereas there was strong evidence that survivors became more consistent over time. We expected that IIV may decrease across the study period across all groups and tasks, indicating more consistent performance with practice. Our unexpected findings suggest that participants may have been less engaged or attentive as the study went on, at least with respect to the processing speed and working memory updating tasks. These two tasks may be especially sensitive to disengagement because the outcomes involve a time component (the score is dependent on the number and proportion correct per minute, respectively). Given that survivors showed increasing consistency in spatial working memory, however, a disengagement interpretation may not fully explain the data. Although we did not measure participants’ motivation or similar constructs, the finding that IIV changed across the course of the study is a reminder for researchers to check the common modeling assumption that one’s data demonstrate relatively constant variance over the course of a study.

Overall, similar findings emerged for processing speed and working memory updating, indicating that survivors performed better but less consistently on these tasks than the comparison group. On the spatial working memory task, survivors performed better in that they had overall better mean performance and greater improvement over the course of the study, and they also became more consistent with time (please note, the latter two findings are only for incorrect responses, because the correct responses were modeled separately). We therefore did not replicate previous findings that suggest that breast cancer patients and survivors may not benefit from practice effects to the same degree as controls with respect to mean performance15,22.

Our unexpected findings of better mean performance among survivors highlight the importance of selecting a comparison group. Although the demographic and regional differences between these samples complicate the interpretation of our findings and make us less confident in the true source of the observed group differences, they also invite us to consider how CRCI may compare in magnitude to other correlates of cognitive performance in mid-life. A caveat to this interpretation is that because we do not have information on cognitive performance prior to cancer treatment, it is possible that survivors in this study represent a selected subgroup with greater resilience, cognitive reserve, or access to supportive resources. These characteristics may precede their cancer experience and help explain their better average performance. If present, such a survivor bias may obscure CRCI-related deficits when only average performance is examined.

Collectively, these findings lend additional evidence to the hypothesis that IIV may be an important indicator of cognitive performance to consider among breast cancer survivors, because even with the relative advantages these women had on mean performance, their consistency on processing speed and working memory updating was worse than comparison participants. Unlike average cognitive performance, which can be heavily influenced by premorbid cognitive reserve and demographic factors, IIV may offer a less confounded index of cognitive stability or regulatory capacity. In this context, higher IIV among survivors, despite better average performance, may reflect subtle disruptions in attentional control not evident in mean-level scores. Put more concretely, IIV may reflect a sensitivity to distractions – although time-varying covariates were not examined here, it is conceivable that intermittent physical symptoms (e.g., fatigue, pain) common in survivorship may be at play. Indeed, in a prior analysis of data solely from the survivors, we found that individuals performed more slowly on processing speed at times when they reported being more fatigued than their typical level27. It may be the case that survivors’ performance is more vulnerable to less-than-optimal conditions, which may help to explain the disconnect between task-based cognitive performance in the laboratory and survivors’ reports of cognition in their everyday lives28.

Practical Implications

Although they are not often the focus of research on CRCI, both IIV and practice effects have implications for quality of life among breast cancer survivors. In daily life, a high degree of variability in one’s working memory performance, for example, may lead to frustrating and unpredictable outcomes when attempting to recall information, because it may be difficult to know when you can rely on your memory as opposed to when you should engage in cognitive offloading (i.e., taking notes, scheduling appointment reminders), which can reduce performance gaps between individuals with varying levels of working memory capacity36. With respect to practice effects, we regularly encounter new processes and tasks in daily life (e.g., a new route home from work due to construction37, or a new interface on your smartphone after a software update), and people who adapt to these changes more slowly may find themselves challenged and at a disadvantage in comparison to their peers. By understanding how different aspects of cognitive performance may be related to cancer survivorship, we can better connect task-based cognitive performance data, like that in this study, to the lived experiences of cognitive impairment in the daily lives of cancer survivors.

Strengths

The present analysis included five indices of cognitive performance, including average performance (commonly included in studies of CRCI) as well as intraindividual variability, between-person dispersion around the group mean, and the relation between time and average performance/IIV. This comprehensive approach allowed us to understand how several dimensions of cognitive performance may be related to cancer history. Our statistical approach allowed us to include a nonlinear relation between time and mean performance. We were also able to account for the distribution of the spatial working memory data by using a hurdle gamma model. Finally, our use of ambulatory cognitive data allowed us to capture many observations of daily cognitive performance, which is a notable contribution to the study of IIV in breast cancer patients and survivors because prior research on IIV in this area has looked only within and across laboratory sessions. Here, we have a more robust measure of IIV because we followed participants closely over a longer period of time.

Limitations

With respect to the statistical approach, covariates were only included at the asymptote (betaMu) in the processing speed and working memory updating models. Additionally, although the use of the hurdle gamma model allowed us to better fit the spatial working memory model to our data, we were limited in our ability to integrate findings related to both correct and incorrect responses. Although we were able to control for key demographic covariates (age and education), given that the breast cancer and comparison samples were recruited from different populations, which varied in terms of a number of key characteristics, the statistical control of covariates may be somewhat incomplete. Future studies that compare individuals who are recruited at the same time, from roughly the same socioeconomic backgrounds, may allow us to further understand the association between IIV and breast cancer.

The present analyses examined indices of cognitive performance beyond the conventional mean-based approach; future work may identify contexts- or moments-of-risk (i.e., time-varying predictors such as fatigue, stressors, affect) which predict, for example, within-person decreases in performance as well as individual differences in these contexts (i.e., individuals who are more fatigued or have more stressors on average) that are captured in IIV. Additionally, although the intensive longitudinal design of this study allowed for a robust measure of IIV across many observations and days, it is worth keeping in mind that prior lab-based studies have typically calculated IIV across trials within a task. The extent to which these different ways of conceptualizing and assessing IIV represent the same underlying construct, and the same lived experience for cancer survivors, is currently unclear. To assess the hypothesis that executive dyscontrol may be an underlying mechanism of IIV in breast cancer survivors16, we hope to see future research that includes contextual factors such as fatigue and stress, as well as research that investigates IIV as we have operationalized it here.

Finally, task-based (objective) and self-report (subjective) cognitive performance often have weak correlations at the between-person level38. IIV has been put forward as a possible index of cognitive performance that could relate more closely to self-reported cognitive performance among breast cancer patients and survivors, but there is very limited literature in this area16. Although an examination of self-reported cognition is beyond the scope of this paper, we hope to see future literature that will investigate whether different indices of task-based cognitive performance, including IIV, may more closely relate to self-reports than calculations of mean performance.

Conclusion

Intensive longitudinal designs are essential for understanding cognitive performance in daily life, and these data allow us to have a much more robust measure of IIV and practice effects than have been reported in previous research on IIV among breast cancer patients and survivors. This type of study also allows for more ecologically valid data that reflects participants’ cognitive performance in daily life. The statistical approach we used allowed us to model nonlinear practice effects, understand within-group heterogeneity, and model within-person variability to look for group differences in IIV and the relation between time and IIV. IIV may indeed be a sensitive indicator of CRCI, which has implications for quality of life among breast cancer survivors.

Data availability

In accordance with the NIH Data Sharing Policy, deidentified data collected as part of this study and supporting documentation will be made available to other researchers who contact the Principal Investigator directly and complete a material transfer agreement.

Code availability

Code for the main analysis and data visualizations, as well as data for visualizing the posterior distribution, can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/KFPGU.

References

Fleming, B., Edison, P. & Kenny, L. Cognitive impairment after cancer treatment: mechanisms, clinical characterization, and management. BMJ 380, e071726 (2023).

Small, B. J., Scott, S. B., Jim, H. S. L. & Jacobsen, P. B. Is cancer a risk factor for cognitive decline in late life?. Gerontology 61, 561–566 (2015).

Ahles, T. A. & Hurria, A. New challenges in psycho-oncology research IV: cognition and cancer: conceptual and methodological issues and future directions. Psychooncology 27, 3–9 (2018).

Whittaker, A. L., George, R. P. & O’Malley, L. Prevalence of cognitive impairment following chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 12, 2135 (2022).

Dijkshoorn, A. B. C. et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment and change in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Psychooncology 30, 635–648 (2021).

Oliva, G. et al. Cognitive impairment following breast cancer treatments: an umbrella review. Oncologist 29, e848–e863 (2024).

Zdanowski, S., Tieks, A., Jeronimus, B. F. & Zuidersma, M. Intra-individual variability in cognitive performance can befuddle the study of cognitive impairments and decline. J. Alzheimers Dis. 85, 519–525 (2022).

Nesselroade, J. R. & Salthouse, T. A. Methodological and theoretical implications of intraindividual variability in perceptual-motor performance. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 59, P49–P55 (2004).

Haynes, B. I., Bauermeister, S. & Bunce, D. A systematic review of longitudinal associations between reaction time intraindividual variability and age-related cognitive decline or impairment, dementia, and mortality. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 23, 431–445 (2017).

Dixon, R. A. et al. Neurocognitive markers of cognitive impairment: exploring the roles of speed and inconsistency. Neuropsychology 21, 381–399 (2007).

Christensen, H. et al. Within-occasion intraindividual variability and preclinical diagnostic status: is intraindividual variability an indicator of mild cognitive impairment?. Neuropsychology 19, 309–317 (2005).

Bernstein, L. J., Catton, P. A. & Tannock, I. F. Intra-individual variability in women with breast cancer. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 20, 380–390 (2014).

Yao, C. et al. Pretreatment differences in intraindividual variability in reaction time between women diagnosed with breast cancer and healthy controls. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 22, 530–539 (2016).

Yao, C., Rich, J. B., Tirona, K. & Bernstein, L. J. Intraindividual variability in reaction time before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology 26, 2261–2268 (2017).

Collins, B., Widmann, G. & Tasca, G. A. Effectiveness of intraindividual variability in detecting subtle cognitive performance deficits in breast cancer patients. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 24, 724–734 (2018).

Vance, D. E. et al. Cognitive intra-individual variability in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 32, 1346–1360 (2023).

Jones, R. N. Practice and retest effects in longitudinal studies of cognitive functioning. Alzheimers Dement. 1, 101–102 (2015).

Goldberg, T. E., Harvey, P. D., Wesnes, K. A., Snyder, P. J. & Schneider, L. S. Practice effects due to serial cognitive assessment: Implications for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease randomized controlled trials. Alzheimers Dement. 1, 103–111 (2015).

Bartels, C., Wegrzyn, M., Wiedl, A., Ackermann, V. & Ehrenreich, H. Practice effects in healthy adults: a longitudinal study on frequent repetitive cognitive testing. BMC Neurosci. 11, 118 (2010).

Weingartner, H. et al. The effects of repetition on memory performance in cognitively impaired patients. Neuropsychology 7, 385–395 (1993).

Williams, D. R., Zimprich, D. R. & Rast, P. A Bayesian nonlinear mixed-effects location scale model for learning. Behav. Res. Methods 51, 1968–1986 (2019).

Collins, B., Mackenzie, J., Tasca, G. A., Scherling, C. & Smith, A. Persistent cognitive changes in breast cancer patients 1 year following completion of chemotherapy. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 20, 370–379 (2014).

Smyth, J. M. & Stone, A. A. Ecological momentary assessment research in behavioral medicine. J. Happiness Stud. 4, 35–52 (2003).

Sliwinski, M. J. et al. Reliability and validity of ambulatory cognitive assessments. Assessment 25, 14–30 (2018).

Ahles, T. A. & Root, J. C. Cognitive effects of cancer and cancer treatments. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 14, 425–451 (2018).

Scott, S. B., Mogle, J. A., Sliwinski, M. J., Jim, H. S. L. & Small, B. J. Memory lapses in daily life among breast cancer survivors and women without cancer history. Psychooncology 29, 861–868 (2020).

Small, B. J., Jim, H. S. L., Eisel, S. L., Jacobsen, P. B. & Scott, S. B. Cognitive performance of breast cancer survivors in daily life: Role of fatigue and depressed mood. Psychooncology 28, 2174–2180 (2019).

Veal, B. M., Scott, S. B., Jim, H. S. L. & Small, B. J. Subjective cognition and memory lapses in the daily lives of breast cancer survivors: Examining associations with objective cognitive performance, fatigue, and depressed mood. Psychooncology 32, 1298–1305 (2023).

Stuss, D. T., Murphy, K. J., Binns, M. A. & Alexander, M. P. Staying on the job: the frontal lobes control individual performance variability. Brain 126, 2363–2380 (2003).

Scott, S. B. et al. The effects of stress on cognitive aging, physiology and emotion (ESCAPE) project. BMC Psychiatry 15, 146 (2015).

Dzubur, E. et al. MixWILD: a program for examining the effects of variance and slope of time-varying variables in intensive longitudinal data. Behav. Res. Methods 52, 1403–1427 (2020).

Hedeker, D., Mermelstein, R. J. & Demirtas, H. An application of a mixed-effects location scale model for analysis of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data. Biometrics 64, 627–634 (2008).

Williams, D. R., Martin, S. R., Liu, S. & Rast, P. Bayesian multivariate mixed-effects location scale modeling of longitudinal relations among affective traits, states, and physical activity. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 36, 981–997 (2020).

Bürkner, P.-C. Brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1–28 (2017).

Dannefer, D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 58, S327–S337 (2003).

Richmond, L. L. et al. Individual differences in prospective and retrospective memory offloading. J. Mem. Lang. 142, 104617 (2025).

Zavala, D. V. et al. Exploring epigenetic age acceleration and cognitive change in middle adulthood. PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/s2zqx_v1 (2025).

Burmester, B., Leathem, J. & Merrick, P. Subjective cognitive complaints and objective cognitive function in aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent cross-sectional findings. Neuropsychol. Rev. 26, 376–393 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (M.J.S., R01AG039409), (S.B.S., R03AG050798); and the National Cancer Institute (S.B.S. and B.J.S., R03CA191712). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.E.C. analyzed data and led the development of the manuscript and submission. All co-authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript. S.B.S. and B.J.S. designed, secured funding for, and oversaw the breast cancer survivors study; M.J.S. designed, secured funding for, and oversaw the comparison study. M.J.S. and J.A.M. designed the cognitive tasks and advised on their interpretation. G.P. assembled the data and developed the original conceptualization of the research question, assembled the combined dataset, and conducted preliminary analyses. J.M.F. advised on the Bayesian MELS code and interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks David Vance, Pedro Rodrigues for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Yana Fandakova and Jennifer Bellingtier. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Castle, J.E., Pasquini, G., Small, B.J. et al. Ecological momentary assessments of cognitive performance are more variable in breast cancer survivors. Commun Psychol 3, 174 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00349-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00349-9