Abstract

Psychopathy is a personality construct characterized by boldness, disinhibition, insensitivity to others’ suffering or distress, and persistent engagement in behaviors that harm others. These combined features suggest that highly psychopathic people may place much less subjective weight on others’ outcomes relative to their own. We therefore assessed social discounting, which indexes how the subjective value of others’ outcomes declines as a function of social distance, in a demographically diverse community sample of very-high psychopathy adults (above the 95th percentile of TriPM scorers; n = 288), as well as a sample of demographically similar controls (n = 427), who also reported antisocial and criminal behavior. Results show robust increases in social discounting as psychopathy increases (p < 0.001), and that reduced subjective valuation of others’ outcomes partially mediates the group differences in antisocial behavior (p = 0.018). These insights emphasize the importance of understanding how psychopathic traits manifest in the community and underscore how diminished valuation of others’ outcomes represents an important mechanism driving maladaptive behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychopathy is among the strongest dispositional predictors of antisocial behaviors that cause others distress, suffering, or harm, ranging from lying, theft, and manipulativeness to violence and criminal offending1,2,3. Psychopathy is particularly closely linked to instrumental aggression, or intentionally harming others for personal gain4,5,6,7. Core affective features of psychopathy include callousness and uncaring, which reflect relative insensitivity to others’ suffering or distress2,8. That causing instrumental harm and insensitivity to others’ suffering are core features of psychopathy suggests psychopathy may be characterized by reduced subjective valuation of others’ welfare. That is, highly psychopathic people may harm others and fail to care if they suffer because they place little subjective weight on others’ outcomes relative to their own. But no prior study has quantified the relationship between psychopathy and the subjective valuation of others’ welfare, or whether this variable can account for affective and behavioral features of clinically significant psychopathy.

Psychopathy is generally agreed to vary along a spectrum in forensic, clinical, and community samples9,10,11. Features of psychopathy include callousness, boldness, and impulsivity7,12, with 1-5% of the population exhibiting clinically significant levels of these traits4,7,13,14,15. People with psychopathic traits consistently exhibit higher levels of antisocial and criminal behavior7. Previous research has suggested a variety of factors that may drive antisociality in psychopathy. One is deficits in learning from punishment or threat16,17, for example, impaired response reversal and passive avoidance learning in response to aversive stimuli18,19. These patterns may in part reflect low fear responding in psychopathy20,21,22,23,24,25, which may result from atypical patterns of neurodevelopment that render punishments less effective as deterrents26,27,28,29. Antisociality in psychopathy and other disorders may also, in part, reflect deficits in executive functions like cognitive control2,30,31,32, as well as social deficits, such as reduced empathic and perspective-taking abilities7,33,34,35,36,37, and decreased affiliative motivation38,39. Accordingly, psychopathy has been linked to reduced prosocial behavior using tasks such as the dictator game and donation paradigms40,41,42,43. However, little research has considered whether these features reflect people with psychopathy assigning less subjective value to others’ outcomes.

The social discounting task was developed to quantify the subjective valuation of others’ welfare. The task is modeled on temporal discounting tasks, which index decreases in the subjective value of rewards as a function of delay. The social discounting task instead indexes decreases in the subjective value of rewards as a function of the social distance of the person the reward is shared with. In this task, respondents make choices to keep resources or share them with real people of increasing social distance44,45,46, allowing the subjective value of outcomes for the self (N = 0) versus others at varying social distances (N = 1–100) to be calculated. Declines in the subjective value of a reward follow a hyperbolic function across increasing social distances 46. Advantages of this task over other paradigms involving resource allocation, such as the dictator game and donation games, include the use of multiple trials per recipient, as well as decisions for multiple real recipients who vary in social closeness (rather than a single anonymous stranger or abstract organization). This structure enables the calculation of a reliable value that can be interpreted as representing the subjective valuation of actual others’ welfare.

Because the majority of actual prosocial behavior is aimed at benefiting close others rather than strangers47,48,49, this task also benefits from increased ecological validity relative to other commonly-used paradigms such as the dictator game and social value orientation task (SVO) that focus on generosity toward a single anonymous stranger and which were created to assess other constructs (for example, individualistic versus competitive, altruistic, or cooperative outcomes in the case of the SVO). As a result of these task features, the social discounting task has higher predictive validity than other prosocial tasks, including the SVO and dictator game50 or self-report measures51,52. Furthermore, neuroimaging and behavioral research support the conclusion that choices during the task reflect variation in the subjective valuation of others’ welfare rather than effortful suppression of selfish responses52.

Thus, the current study used the social discounting task to assess how the subjective valuation of others’ welfare varies as a function of psychopathy. Three prior studies using undergraduate samples have altered features of the social discounting task to assess, respectively, communion53,54 and generosity for single versus multiple people55 in psychopathy. These studies found mixed results, with two studies finding decreased generosity was associated with psychopathy53,55 and the third finding no relationship between psychopathy and discounting54. Antisocial behaviors more broadly, including self-reported texting while driving56 and adolescent externalizing symptoms57 have been linked to increased social discounting. None of these studies, however, has found a link between psychopathy and social discounting using the standard version of the social discounting task that aims to quantify subjective valuation of others’ welfare, or assessed social discounting in a sample with clinically significant psychopathic traits.

Sampling is a persistent challenge in studying neurocognitive features of psychopathy. High-psychopathy samples are often recruited from forensic or psychiatric institutions, carrying challenges related to constrained recruitment and testing opportunities, non-representative samples, and difficulties determining whether neurocognitive impairments are core features of psychopathy or the result of institutionalization58. Disagreement persists about whether research in university students and other community samples with low average levels of psychopathy can be extrapolated to understanding clinically significant psychopathy59,60. And studies of so-called “successful psychopathy” that recruit from industrial settings or unemployment agencies tend to have small sample sizes61,62,63,64. Thus, little research to date has been conducted in well-powered non-institutionalized high-psychopathy samples recruited from the community.

We assessed social discounting in very high-psychopathy adults (above the 95th percentile of TriPM scorers) recruited from the community and demographically similar controls. Following prior work linking reduced social discounting to highly prosocial phenotypes52, we predicted psychopathy would be associated with increased social discounting. We also predicted that the association between psychopathy and antisociality would be partly mediated by reductions in the subjective valuation of others’ welfare as psychopathy increases. We also considered potential effects of age, gender, socio-economic status (household income), and cognitive intelligence, given prior evidence that increases in these variables are reliably associated with increased generosity50,65,66,67,68,69. Additionally, in light of disagreements about whether findings in high-psychopathy samples can be generalized to the general population, we conducted both group-based analyses comparing high psychopathy and control groups, continuous analyses across the full sample, and, where relevant, separate analyses within the high-psychopathy and general-population samples.

Methods

This study was approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board (ID#: 0000193). All participants provided informed written consent before the commencement of testing and were informed that the confidentiality of their responses was protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health. The study was not pre-registered. However, the authors completed and presented results utilizing a multiverse approach by using two common methods of analyzing discounting tasks (logk and AUC) while also examining group differences along with psychopathy continuously. Primary analyses examining the relationship between psychopathy and logk, and whether logk moderates or mediates the relationship between psychopathy and antisocial behavior, are presented in the main manuscript. In the Supplementary Information file, we report parallel analyses using AUC, an alternative discounting metric (Tables S18-26). All data and analysis code are publicly available70.

Participants

A total of 727 participants took part in this study, a sample size determined using the effect size generated from a recent meta-analysis71, that found this sample would yield >80% power to identify group differences in social discounting at a statistical threshold of p < 0.05. Participants included a unique community sample of 366 very high-psychopathy participants recruited through the 501(c)(3) non-profit organization Psychopathy Is (now The Society for the Prevention of Disorders of Aggression, https://www.disordersofaggression.org), which provides information and resources for individuals and families affected by psychopathy and related disorders. Visitors can complete screening tests on the website, including the Triarchic Psychopathy Measure (TriPM)12, a 58-item self-report measure that assesses three psychopathy subscales: boldness, meanness, and disinhibition (to protect visitors’ privacy, no data are collected about participants or their scores on this measure by the website). Participants who receive TriPM scores in the top 5% of American adults of their gender4 receive information about diagnostic and treatment options, as well as a link to take part in research upon providing their contact information, age, gender, and country of residence. We invited the 1242 respondents who had provided this information as of 11/13/23, were 18 or older, and indicated they reside in the United States to complete the study. Of these, 464 confirmed interest in participating in this study. We continued online recruitment until we achieved our intended sample of high-psychopathy participants. In addition, 361 control participants were recruited through CloudResearch. These participants completed identical measures. Controls were recruited to approximately match the high-psychopathy participants in terms of gender, age range, and race/ethnicity. Upon completion of the online Qualtrics survey, participants were compensated $15.

Prior to conducting group-based analyses, 78 participants whose TriPM scores fell below the estimated 95th percentile for their gender (Male=105; F or O = 91) were removed from the high-psychopathy group and reassigned to the control group. Cutoffs were derived from percentiles calculated using scores from a quasi-representative sample of U.S. adults who completed the TriPM4. In addition, 10 controls who scored above the cutoff scores for their gender were reassigned to the high psychopathy group (results were consistent when data were re-analyzed after dropping all reassigned participants; see Supplementary Information; Table S27-S48). Finally, 12 participants who failed two or more of four attention checks (n = 10 high-psychopathy and 2 controls) were excluded. Thus, our final sample of 715 included 288 high-psychopathy participants and 427 controls who were between 18-79 years old (M = 36.7 years; gender and race/ethnicity reported in Table 1).

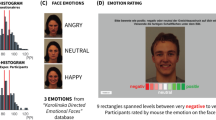

Psychopathy was confirmed in our high-psychopathy group via follow-up screening using the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL-SV)72, which was administered to 15% of 288 high-psychopathy participants (n = 44). The PCL-SV is a semi-structured interview-based assessment considered to be a reliable and valid measure of psychopathy, resulting in a total score that is further broken into a Factor 1 and Factor 2 score73,74. Adapted from the Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R), the PCL:SV can be used in forensic and non-forensic settings. Although psychopathy is now agreed to be continuously distributed, scores ≥ 18 have been previously used as clinical cutoffs 73, although scores ≥ 8 optimize specificity and sensitivity for predicting outcomes such as community violence in civil psychiatric samples75. The TriPM is moderately correlated with the Psychopathy Checklist Revised76,77. However, the PCL-SV captures features of psychopathy not assessed by the TriPM, namely a greater focus on antisociality and criminal behavior. In the current study, PCL-SV was administered via the web conferencing tool Zoom by 2–4 trained interviewers. This 45–60 minute interview asks questions regarding early life experiences, work and relationship history, behaviors, and criminal offenses. Participants who completed the PCL-SV were compensated an additional $20.

Procedure

All participants completed identical screening and survey measures presented in a randomized order before the social discounting task. In addition to the TriPM12, antisocial behavior and attitudes were assessed using the Subtypes of Antisocial Behavior questionnaire (STAB)78. This is a 32-item self-report measure that assesses rule-breaking behavior, physical aggression, and social aggression in the past year. Fluid intelligence was assessed with a measure drawn from UK Biobank79, which includes 13 logic and reasoning questions that participants have up to two minutes to answer. Participants also self-reported their lifetime criminal history, including offenses committed, criminal charges, and convictions, along with their incarceration history. Lastly, participants provided demographic information, including age, gender, and household income.

Participants also completed the social discounting task as a part of the online Qualtrics survey (Fig. S1). Following established procedures46,47,51,52, participants were asked to imagine a list of 100 people, with 1 being their closest other and 100 being a stranger. They were instructed to provide the names of real people they know who represent seven specific social distances (N = 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100). Participants then made nine dichotomous choices for each N (Fig. S1). Therefore, there were seven blocks with nine trials (i.e., dichotomous choices) per block. In each trial, the selfish choice entailed choosing to keep an amount of money (the value ranged from $155-$75, decreasing in increments of $10 across trials), while the generous choice remained the same (splitting the money with that N, so both would receive $75). Thus, for example, in one trial, a participant might decide to keep $155 or to split $150 with their closest social other (N = 1). Participants who choose the generous option would thus choose to sacrifice $80 to benefit that person. This format permits an “indifference point” which we estimated for each social other (N) as the trial in which the participant switched from selfish choices to sharing with the other person.

If the participant chose the selfish option for all the trials in a given block, the indifference point was assumed at $75. If the participant chose the generous option for all trials in the block, the indifference point was assumed at $155. Amounts willing to forgo (v) were calculated by subtracting $75 from the indifference point for each block for each participant, resulting in seven “amount willing to forgo” (v) observations corresponding to one of seven social others (N) for each participant (i).

Statistical analysis

We compared social discounting between groups by calculating the indifference point, which represents the maximum amount participants were willing to forgo for each social distance (N). To determine the best-fitting model for the data, we assessed the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values across hyperbolic, exponential, and linear models. The hyperbolic model yielded the lowest AIC value (46142.77), indicating a superior fit compared to the exponential (AIC: 49021.74) and linear (AIC: 48269.92) models. ∆AIC values also confirmed the hyperbolic model was a stronger fit than the exponential model (3,127.15) or linear model (2,127.15) (∆AIC > 10 indicates strong evidence for the model with the lower AIC value having a superior fit80. Finally, model weights (AICcWt) calculated using the AICcmodavg package81 in R indicated that the hyperbolic model had an Akaike weight of 1.00, indicating it was overwhelmingly the most likely model given these data. A hyperbolic discounting curve was thus modeled to estimate discounting rates for each participant. This curve follows the function46,47:

where V0 is the value of the reward which stays constant, k is the degree of discounting, N is the social distance, and v is the discounted value of the reward as a function of discounting rate and social distance. Participants’ social discounting rates calculated from the hyperbolic model are represented using k/logk. Logk represents the rate of decay in the amount a participant is willing to forgo changes as social distance increases.

We conducted secondary analyses using the pracma package82 in R to calculate the area under the curve (AUC), which is a model-agnostic assessment of discounting. AUC is calculated using a trapezoidal function that sums the average amount a participant is willing to forgo for each social distance and converts this value to a proportion between 0 and 1, with higher AUC scores reflecting more overall generosity. AUC and logk thus provide unique insights, as AUC captures overall generosity and logk highlights the rate of change. All models also included age, gender (with female/other as the reference), household income, and fluid intelligence as covariates. Results regarding AUC values are found in the Supplementary Information file (Tables S18–26) and are similar to results using logk.

Multiple regression models were used to examine the relationship between psychopathy and social discounting (dichotomously and continuously), and whether social discounting moderated group differences in antisocial behavior. Mediation analyses were completed using the mediation package83 in R to investigate if social discounting explained group differences in antisocial behavior. Lastly, multiple regression models were used to investigate if age moderated the relationship between psychopathy and social discounting. All analyses were conducted using two-tailed tests. All models were checked for standard statistical assumptions, and assumptions were generally met across models. To examine the robustness of our primary results, we conducted two robustness checks using 10-fold cross-validation and running models following propensity score matching. Results of these analyses were consistent with those presented below and are reported in the Supplementary Information file (cross-validation: Table S2; propensity score matching: Tables S3, S4).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Summed total psychopathy scores for each participant were calculated along with subscale scores. The mean total psychopathy score for participants in the high-psychopathy group was 122.25 (SD = 16.92, overall range = 91-165; Female/Other = 91-163, Male = 105-165). This places all high psychopathy participants above the 95th percentile of TriPM scores according to their gender, with their mean score being above the 99th percentile4. Controls’ mean score was 55.86 (SD = 19.90, overall range = 19–104, Female/Other = 19–90, Male = 23–104; t(675.83) = −47.90, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −3.78, 95% CI [−3.78, −3.30]), placing controls between the 1st and 94th percentile with mean score being at the 39th percentile for females and 28th percentile for males4 (Table S5). Groups did not differ in gender composition or race/ethnicity (Table 1). Because only age ranges can be pre-specified in CloudResearch the control group was older, t(700.63) = 11.33, p < 0.001, d = 0.82, 95% CI [0.66, 0.98], Table 1, as well as more educated, t(590.42) = 6.90, p < 0.001, d = 0.53, 95% CI [0.38, 0.68], Table 1, and higher in fluid intelligence, t(643.03) = 2.66, p = 0.01, d = 0.20, 95% CI [0.05, 0.35], Table S5, than the high psychopathy group.

Given group differences and prior evidence linking these variables to prosociality and antisociality50,67,84,85, age and fluid intelligence were included as covariates in all models. Income and gender were also included as covariates, given consistent evidence linking them to prosociality50,62,78. (19 participants who reported not knowing their household income were re-coded as being in the mean income bracket of the full sample.) Group differences in TriPM scores persisted when controlling for age, gender, income, and fluid intelligence (B = 0.83, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.79, 0.87], F(5,709) = 473.9). Across the full sample, high internal consistency of total psychopathy scores (Cronbach’s a ɑ = 0.97), Boldness (ɑ = 0.90), Meanness (ɑ = 0.96), and Disinhibition (ɑ = 0.94) subscale scores was observed. To further assess the reliability of responses, we conducted Cronbach’s alpha reliability analyses for the TriPM total score and subscales with each recruitment source separately. We also compared responses across groups to the pre-survey commitment request (see Supplementary Information). Results indicated high reliability of responses for both groups and comparable responses to the commitment request.

Forty-four participants in the high psychopathy group completed a PCL:SV interview. Ratings were determined from the semi-structured interview. All interviewers received formal training in administering and scoring PCL instruments. Following each interview, each interviewer independently scored the participant before the raters met to discuss and decide on final scores for each of the 12 items. The average PCL:SV final score was 14.32 (SD = 5.18), with scores ranging from 3–23. 38/44 (86%) of screened participants received scores >= 8. Total PCL:SV and TriPM scores were moderately correlated, r(42) = 0.49, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.23, 0.69], and within the range found in prior work (rs = 0.20–0.62)76,86. Interrater reliability of Total, Factor 1, and Factor 2 scores was estimated using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) using the psych R package87 based on a single rater, absolute, one-way random-effects model. ICCs were 0.81 (p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.73, 0.88]) for total scores, 0.72 (p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.62, 0.82]) for Factor 1, and 0.76 (p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.67, 0.85]) for Factor 288.

We also found high internal consistency for total antisociality (STAB) scores across the sample (ɑ = 0.96) and within each group (see Supplementary Information) and thus calculated each participant’s summed antisocial behavior. Consistent with their psychopathy scores, high-psychopathy participants reported significantly more antisocial behavior (M = 95.27, SD = 18.67, range = 44–155) than controls (M = 58.81, SD = 18.07, range = 32–138), t(602.27) = –25.94, p < 0.001, d = −1.99, 95% CI [−2.17, −1.81] (Table 1, Table S5). Group differences persisted when controlling for age, gender, income, and fluid intelligence, B = 0.68, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.63, 0.74], (Table S6). High-psychopathy participants also reported committing, being charged with, and being convicted of criminal offenses at much higher rates than controls. High-psychopathy participants were 1199% more likely to have committed at least one crime, 287% more likely to have been charged with at least one crime, and 209% more likely to have been convicted of at least one crime (again, controlling for covariates; committed: OR = 12.99, 95% CI [8.48, 20.39], p <0.001; charged: OR = 3.87, 95% CI [2.61, 5.80], p < 0.001; convicted: OR = 3.09, 95% CI [2.06, 4.67], p < 0.001; Tables S7-S9). Associations between group and criminal involvement remained statistically significant following Bonferroni correction to α = 0.017 across the three group comparisons. The most frequently reported criminal behaviors committed by respondents in the high-psychopathy group were drug possession (64%), driving under the influence (61%), reckless driving (59%), vandalism (56%), larceny (53%), and assault (42%) (Table 2).

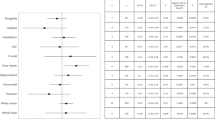

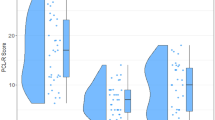

After modeling the group differences in the social discounting curve using a hyperbolic model (Table S10), individual logk values were calculated for each participant. A bivariate association between psychopathy group and logk was observed, t(614.49) = −11.97, p < 0.001, d = −0.91, 95% CI [−1.07, −0.76], which persisted after controlling for age, gender, income, and fluid intelligence, B = 0.38, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.31, 0.45]; Table 3, Fig. 1), indicating that high-psychopathy participants show a significantly steeper hyperbolic decay in generosity as social distance increases relative to controls. Results were replicated when utilizing 10-fold cross-validation and propensity score matching, reported in the Supplementary Information file (cross-validation: Table S2; propensity score matching: Tables S3–4). No statistically significant main effects of gender or income were observed. However, a main effect of age was observed, such that social discounting decreased as age increased, B = −0.13, p = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.20, −0.05], and a main effect of fluid intelligence was observed, such that social discounting increased as intelligence increased, B = 0.10, p = 0.005, 95% CI [0.03, 0.16]. Similar results were observed when the relationship between discounting (logk) and psychopathy was assessed as a continuous measure across all participants, with social discounting again increasing as psychopathy increased, B = 0.40, p < .001, 95% CI [0.33, 0.47] (Table 4, Fig. S2), with the bivariate association also being significant, r(713) = 0.43, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.36, 0.48]. Associations between psychopathy and logk remained statistically significant following Bonferroni-correction to α = 0.025 to account for conducting both dichotomous and continuous tests.

Social discounting curves with standard error for the current study (control and high psychopathy group, N = 715) and Vekaria et al (2017) (controls, N = 26). The high psychopathy group had higher discounting than both control groups, with control groups overlapping. The shaded region represents the standard error around the mean.

To identify whether one or more subscales of psychopathy were driving this association between psychopathy and logk, we conducted a multiple linear regression including meanness, disinhibition, and boldness subscale scores as predictors of logk, with age, gender, income, and fluid intelligence included as covariates. Meanness was the only subscale that predicted logk, B = .41, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.29, 0.54], (Table S11). The bivariate correlation between meanness and logk was r = 0.45 (df = 713, p < 0.001). Results were replicated when utilizing 10-fold cross-validation and propensity score matching, reported in the Supplementary Information file (cross-validation: Table S2; propensity score matching: Tables S3, 4).

Do differences in social discounting mediate differences in antisocial behavior?

We also found a bivariate association between logk and antisocial behavior across the full sample (r(713) = 0.35, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.29, 0.42]), which remained statistically significant after controlling for age, gender, income, and fluid intelligence, B = 0.30, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.23, 0.37], F(5,709) = 33.38. Mediation analysis found that social discounting (logk) partially mediated group differences in antisocial behavior (total effect: p < 0.001, direct effect: p < 0.001, indirect effect: p = 0.018; proportion mediated: b = 0.04, p = 0.018, 95% CI [0.006, 0.08]; Table S12). This indicated that increased antisocial behavior in the high psychopathy group is partly explained by increased discounting rates. The mediating effect was not significant when considering psychopathy as a continuous variable across the full sample (total effect: p < 0.001, direct effect: p < 0.001, indirect effect: p = 0.67; proportion mediated: b = 0.006, p = 0.67, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.03]; Table S13). Associations between psychopathy and logk remained statistically significant following Bonferroni-correction to α = 0.025 to account for conducting both dichotomous and continuous tests of mediation.

We also observed a significant interaction between discounting and group in predicting antisocial behavior, B = 0.09, p = 0.002, 95% CI [0.03, 0.15] (Table S14; Fig. 2), such that as social discounting (logk) increases, antisocial behavior increases at a higher rate in the high-psychopathy group relative to controls. However, there was not a significant interaction when examining whether social discounting moderated the relationship between psychopathic traits (measured continuously) and antisocial behavior across the full sample, B = 0.0, p = 0.85, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.05] (Table S15). Bonferroni-correction was applied (ɑ = 0.025), and the group-based interactions remained significant under this threshold.

Does age moderate the relationship between psychopathic traits and social discounting?

Prosociality has been observed to increase with increasing age67 and antisocial behavior in psychopathy declines with age1,89,90. In addition to observing a negative relationship between age and social discounting, we also replicated the negative association between antisocial behavior and age across the full sample (B = −0.31, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.38, −0.24], F(4,710) = 21.72). However, when examining if age moderated group differences, the high psychopathy group exhibited a positive association between age and antisocial behavior, whereas the opposite association was observed in controls when controlling for gender, income, and fluid intelligence, Age x Group B = 0.12, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.06, 0.18], F(6,708) = 123.1. We therefore conducted a multiple regression analysis to determine whether age moderates the relationship between psychopathic traits and social discounting. We did not find evidence that age moderated the relationship between psychopathy (treated either dichotomously or continuously) and discounting indexed by logk, dichotomous: B = 0.04, p = 0.31, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.12], (Table S16); continuous: B = 0.03, p = .39, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.10], (Table S17). Thus, although age and antisocial behavior are positively correlated in the high psychopathy group, and the reverse association was observed in controls, age did not significantly moderate the relationship between psychopathy and discounting. However, moderation models involving age showed slight evidence of heteroscedasticity, so findings should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

We report the results of a study involving a large community-recruited sample of very-high psychopathy adults and demographically similar controls, which found that psychopathy was associated with robust, hyperbolic increases in social discounting (logk) and reduced overall generosity (AUC). These associations were mainly driven by the Meanness subscale scores, and social discounting partially mediated group differences in antisocial behavior. These findings indicate that adults with high levels of psychopathy subjectively devalue the welfare of others relative to controls, and link social discounting to increased antisocial behavior in this population.

Our sample is among the largest reported studies of adults in the community with very high psychopathy scores (n = 288), with mean psychopathy scores above the top 1% for their gender4. These participants reported significantly more antisocial behavior than typical adults, and our results indicate a robust relationship between psychopathy and antisocial behavior even among these community-recruited participants. Building on previous findings of reduced prosociality in psychopathy40,41,42,43, our findings extend this work by demonstrating that people high in psychopathy—particularly those scoring high on Meanness—place lower subjective value on others’ welfare, and this association statistically accounts for their increased antisocial behavior.

These results also potentially speak to the question of whether antisocial behaviors, including criminal behaviors, are an intrinsic feature versus a downstream correlate of psychopathy. Psychopathy is a personality construct that reflects several sub-components that vary continuously across the population4,11 and that include traits like meanness and narcissism that indicate devaluation of others’ welfare and are robust predictors of antisocial behavior4,91,92. Our results suggest that antisocial behaviors that reduce others’ welfare may be intrinsically potentiated by very low subjective valuation of others’ welfare in high-psychopathy adults, even when psychopathy is assessed using triarchic measures like the TriPM that de-emphasize criminal and antisocial behavior relative to PCL-based assessments12,93. This may reflect the close association between devaluation of others’ welfare and the meanness subscale, which is a core feature of all major psychopathy measures.

Our recruitment approach enabled both continuous and group-based analyses using a multiverse framework. The convergence of results across continuous and group-based analyses, as well as across two different indices of social discounting (logk and AUC), supports the robustness of our findings. Results indicated some non-linear effects across our sample. Social discounting moderated the relationship between psychopathy group and antisocial behavior, predicting antisocial behavior in the high psychopathy group to a greater degree than in the control group. We also found that antisocial behavior decreased with age in typical adults but increased with age in high-psychopathy adults. These findings support prior work indicating that the association between psychopathy and relevant outcome variables is not always linear20,94 such that typical community samples may not reveal patterns observed in high-psychopathy samples.

Our recruitment approach yielded a sample diverse in gender, age, and other variables, unlike many institutional samples or undergraduate samples95, enabling us to test effects that are difficult to detect in more homogeneous or lower-variance samples. We could thus consider effects of income and gender in our analyses; however, we did not observe significant associations despite prior research linking these variables to generosity96,97,98,99. This is consistent with prior research52, which has suggested that the social discounting task is not simply a donation task, but more generally indexes the subjective valuation of others’ outcomes relative to one’s own outcomes. We did find that social discounting declined with age, consistent with prior findings67, but we did not find statistical evidence that age moderated the relationship between psychopathy and social discounting.

These findings contrast with prior studies of psychopathy and social discounting, which have found small or null effects (rs = 0 to −0.19)40,100. Features of our sample and task may partly explain the divergent findings. Two prior studies of social discounting in psychopathy in undergraduates did not assess choices about targets who varied linearly in social distance as the standard task does, but about people categorized as close, neither close nor distant, distant, and very distant, finding null or small effects (rs = −0.06 to .19)53,54. However, by using specific increments of social distance, the standard task enables precise estimation of discounting curves and more direct interpretation of subjective value. Our larger effect sizes (total psychopathy: r = 0.35; meanness: r = 0.40) are therefore unlikely to be the result of chance fluctuation due to our larger sample size. They more likely reflect our wider range of psychopathy scores, including very high scores, and a standard task modeled on prior social and temporal discounting paradigms, allowing us to interpret our findings as indicating decreased subjective valuation of others’ welfare as psychopathy increases.

Our findings have implications for psychopathy research conducted in student samples, as undergraduate participants score lower on psychopathy dimensions and exhibit restricted variance. As a result, effects observed in clinical samples—in this case, the strong relationship between social discounting and antisocial behavior—may be attenuated in student samples101. More explicit efforts by researchers to identify similarities and differences between observed patterns in clinical and subclinical psychopathy may be valuable.

Limitations

This study’s results should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, like many clinical research studies and other studies recruiting special populations102, this study employed a cross-sectional, correlational design using a purposive sample. We thus refrain from drawing causal conclusions about the origin of the observed effects. Because most of our high-psychopathy participants were recruited after seeking information about psychopathy online, they were in part, self-selected. Self-selection is a pervasive consideration in psychological research, as research participation is voluntary even in institutional and clinical settings, such that research participants represent a small fraction of potentially eligible adults and may generally be biased toward populations that are disproportionately female, wealthy, and/or prosocial103,104,105. A meta-analysis of psychopathy as assessed by the TriPM101 observed that the specific sample studied (e.g., undergraduates, imprisoned samples) moderates the nature of the observed associations. Lending some support to the generalizability of our results, we observed similar results whether including or excluding high-psychopathy CloudResearch panel participants. We also observed high and consistent self-reported commitment and response reliability across participant groups. However, our sample may nonetheless be non-representative of high-psychopathy adults in the community. We evaluated the potential role of covariates such as age, gender, household income, and fluid intelligence in social discounting, but other potentially relevant factors not measured here could include housing status, early-life adversity, or childhood household income. Lastly, when completing the social discounting task, our participants allocated hypothetical resources rather than real money. This approach is supported by previous studies46,51, but may affect choice patterns106. Although some studies suggest that using actual rewards may reduce discounting magnitude107, the results of a recent meta-analysis indicate that the use of hypothetical rewards does not affect discounting patterns71, and we are aware of no evidence that this would affect higher psychopathy participants differently.

Conclusion

The antisocial behaviors associated with psychopathy (including financial, legal, and medical expenses) are estimated to yield societal costs of over $460 billion annually108. It is thus crucial to understand factors influencing antisocial behavior in high-psychopathy populations. This research indicates that psychopathy may be characterized by placing a very low subjective value on others’ welfare, increasing high-psychopathy individuals’ risk for engaging in behaviors that are harmful to others. Identifying the origins of this feature of psychopathy and treatments that may ameliorate it are important goals for future research.

Data availability

Data and materials, including raw data and processed data, are publicly available70 at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8DF4N.

Code availability

Analysis was completed using R version 4.4.1. Analysis code can be publicly accessed70 at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8DF4N.

References

Moffitt, T. E. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol. Rev. 100, 674–701 (1993).

Patrick, C. J. Psychopathy: Current knowledge and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 18, 387–415 (2022).

Reidy, D. E. et al. Why psychopathy matters: Implications for public health and violence prevention. Aggress. Violent Behav. 24, 214–225 (2015).

Berluti, K. et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Psychopathy in the General Population. J. Pers. Disord. 39, 1–21 (2025).

Blair, R. J. R. Traits of empathy and anger: Implications for psychopathy and other disorders associated with aggression. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 373, 20170155 (2018).

Blais, J., Solodukhin, E. & Forth, A. E. A meta-analysis exploring the relationship between psychopathy and instrumental versus reactive violence. Crim. Justice Behav. 41, 797–821 (2014).

De Brito, S. A. et al. Psychopathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 7, 1–21 (2021).

Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol., 217–246.

Neumann, C. S. & Hare, R. D. Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: Links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 76, 893–899 (2008).

Seara-Cardoso, A., Neumann, C., Roiser, J., McCrory, E. & Viding, E. Investigating associations between empathy, morality and psychopathic personality traits in the general population. Pers. Individ. Differ. 52, 67–71 (2012).

Sellbom, M. & Drislane, L. E. The classification of psychopathy. Aggress. Violent Behav. 59, 101473 (2021).

Patrick, C. J., Fowles, D. C. & Krueger, R. F. Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness. Dev. Psychopathol. 21, 913–938 (2009).

Coid, J., Yang, M., Ullrich, S., Roberts, A. & Hare, R. D. Prevalence and correlates of psychopathic traits in the household population of Great Britain. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 32, 65–73 (2009).

Sanz-García, A., Gesteira, C., Sanz, J. & García-Vera, M. P. Prevalence of psychopathy in the general adult population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 12, 661044 (2021).

Werner, K. B., Few, L. R. & Bucholz, K. K. Epidemiology, comorbidity, and behavioral genetics of antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy. Psychiatr. Ann. 45, 195–199 (2015).

Blair, K. S., Morton, J., Leonard, A. & Blair, R. J. R. Impaired decision-making on the basis of both reward and punishment information in individuals with psychopathy. Pers. Individ. Differ. 41, 155–165 (2006).

Brazil, I. A., Mathys, C. D., Popma, A., Hoppenbrouwers, S. S. & Cohn, M. D. Representational Uncertainty in the Brain During Threat Conditioning and the Link With Psychopathic Traits. Biol. Psychiatry: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2, 689–695 (2017).

Blair, R. J. R. et al. Passive avoidance learning in individuals with psychopathy: Modulation by reward but not by punishment. Pers. Individ. Differ. 37, 1179–1192 (2004).

Budhani, S., Richell, R. A. & Blair, R. J. R. Impaired reversal but intact acquisition: Probabilistic response reversal deficits in adult individuals with psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 115, 552–558 (2006).

Cardinale, E. M., Ryan, R. M. & Marsh, A. A. Maladaptive fearlessness: An examination of the association between subjective fear experience and antisocial behaviors linked with callous unemotional traits. J. Pers. Disord. 35, 39–56 (2021).

Fanti, K. A., Mavrommatis, I., Colins, O. & Andershed, H. Fearlessness as an underlying mechanism leading to conduct problems: Testing the intermediate effects of parenting, anxiety, and callous-unemotional traits. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 51, 1115–1128 (2023).

Hofmann, M. J., Mokros, A. & Schneider, S. The joy of being frightened: Fear experience in psychopathy. J. Pers. 92, 321–341 (2024).

Hoppenbrouwers, S. S., Bulten, B. H. & Brazil, I. A. Parsing fear: A reassessment of the evidence for fear deficits in psychopathy. Psychol. Bull. 142, 573–600 (2016).

López, R., Poy, R., Patrick, C. J. & Moltó, J. Deficient fear conditioning and self-reported psychopathy: The role of fearless dominance. Psychophysiology 50, 210–218 (2013).

Lykken, D. T. The antisocial personalities. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. (1995).

Cardinale, E. M. et al. Callous and uncaring traits are associated with reductions in amygdala volume among youths with varying levels of conduct problems. Psychol. Med. 49, 1449–1458 (2019).

Lozier, L. M., Cardinale, E. M., VanMeter, J. W. & Marsh, A. A. Mediation of the relationship between callous-unemotional traits and proactive aggression by amygdala response to fear among children with conduct problems. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 627 (2014).

Pauli, R. & Lockwood, P. L. The computational psychiatry of antisocial behaviour and psychopathy. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 145, 104995 (2023).

Viding, E., Fontaine, N. M. & McCrory, E. J. Antisocial behaviour in children with and without callous-unemotional traits. J. R. Soc. Med. 105, 195–200 (2012).

Baskin-Sommers, A. & Brazil, I. A. The importance of an exaggerated attention bottleneck for understanding psychopathy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26, 325–336 (2022).

Burghart, M., Schmidt, S. & Mier, D. Executive functions in psychopathy: a meta-analysis of inhibition, planning, shifting, and working memory performance. Psychol. Med. 54, 2823–2837 (2024).

Winters, D. E. et al. Cognitive control difficulties differentiate callous-unemotional traits from conduct problems: a pre-registered double-blind randomized controlled trial analysis. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-025-01869-5 (2025).

Drayton, L. A., Santos, L. R. & Baskin-Sommers, A. Psychopaths fail to automatically take the perspective of others. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 3302–3307 (2018).

Marsh, A. A. The caring continuum: Evolved hormonal and proximal mechanisms explain prosocial and antisocial extremes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 347–371 (2019).

Marsh, A. A. & Cardinale, E. M. When psychopathy impairs moral judgments: Neural responses during judgments about causing fear. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9, 3–11 (2014).

Viding, E., McCrory, E., Baskin-Sommers, A., De Brito, S. & Frick, P. An ‘embedded brain’ approach to understanding antisocial behaviour. Trends Cogn. Sci. 28, 159–171 (2023).

Winters, D. E. & Sakai, J. T. Affective theory of mind impairments underlying callous-unemotional traits and the role of cognitive control. Cognit. Emot. 37, 696–713 (2023).

Waller, R. et al. Reduced sensitivity to affiliation and psychopathic traits. Pers. Disord.: Theory, Res., Treat. 12, 437–447 (2021).

Viding, E. & McCrory, E. Towards understanding atypical social affiliation in psychopathy. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 437–444 (2019).

Gunschera, L. J., Brazil, I. A. & Driessen, J. M. A. Social economic decision-making and psychopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 143, 104966 (2022).

Koenigs, M., Kruepke, M. & Newman, J. P. Economic decision-making in psychopathy: A comparison with ventromedial prefrontal lesion patients. Neuropsychologia 48, 2198–2204 (2010).

Lopez, J. I., Shimotsukasa, T. & Oshio, A. I really am more important than you: The relationship between the Dark Triad, cognitive ability, and social value orientations in a sample of Japanese adults. Soc. Sci. Hum. Open 8, 100716 (2023).

Sakai, J. T., Raymond, K. M., McWilliams, S. K. & Mikulich-Gilbertson, S. K. Testing helping behavior and its relationship to antisocial personality and psychopathic traits. Psychiatry Res. 274, 98–104 (2019).

Jones, B. A. A review of social discounting: The impact of social distance on altruism. Psychol. Rec. 72, 511–515 (2022).

Jones, B. A. & Rachlin, H. Delay, probability, and social discounting in a public goods game. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 91, 61–73 (2009).

Jones, B. & Rachlin, H. Social Discounting. Psychol. Sci. 17, 283–286 (2006).

Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S. L., Lewis, B. P., Luce, C. & Neuberg, S. L. Reinterpreting the empathy–altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73, 481–494 (1997).

Curry, O., Roberts, S. G. B. & Dunbar, R. I. M. Altruism in social networks: Evidence for a ‘kinship premium. Br. J. Psychol. 104, 283–295 (2013).

Stewart-Williams, S. Altruism among kin vs. nonkin: Effects of cost of help and reciprocal exchange. Evol. Hum. Behav. 28, 193–198 (2007).

Böckler, A., Tusche, A. & Singer, T. The structure of human prosociality: Differentiating altruistically motivated, norm motivated, strategically motivated, and self-reported prosocial behavior. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 7, 530–541 (2016).

Vekaria, K. M., Brethel-Haurwitz, K. M., Cardinale, E. M., Stoycos, S. A. & Marsh, A. A. Social discounting and distance perceptions in costly altruism. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 0100 (2017).

Rhoads, S. A. et al. Neural responses underlying extraordinary altruists’ generosity for socially distant others. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad199 (2023).

Sherman, E. D. & Lynam, D. R. Psychopathy and low communion: An overlooked and underappreciated core feature. Pers. Disord.: Theory, Res., Treat. 8, 309–318 (2017).

Spantidaki Kyriazi, F. et al. A multi-method investigation of motive dispositions: Affiliative and antagonistic dispositions in psychopathy. J. Crim. Psychol. 14, 99–119 (2024).

Malesza, M. & Kalinowski, K. Willingness to share, impulsivity and the Dark Triad traits. Curr. Psychol. 40, 3888–3896 (2021).

Romanowich, P., Igaki, T., Yamagishi, N. & Norman, T. Differential associations between Risky cell-phone behaviors and discounting types. Psychol. Rec. 71, 199–209 (2021).

Sharp, C. et al. Social discounting and externalizing behavior problems in boys. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 25, 239–247 (2012).

Lanciano, T., de Leonardis, L. & Curci, A. The psychological effects of imprisonment: The role of cognitive, psychopathic and affective traits. Eur. J. Psychol. 18, 262–278 (2022).

Forth, A. E., Brown, S. L., Hart, S. D. & Hare, R. D. The assessment of psychopathy in male and female noncriminals: Reliability and validity. Pers. Individ. Differ. 20, 531–543 (1996).

Lilienfeld, S. O. Methodological advances and developments in the assessment of psychopathy. Behav. Res. Ther. 36, 99–125 (1998).

Benning, S. D., Venables, N. C., & Hall, J. R. Successful psychopathy. In Handbook of Psychopathy, 2nd edn (pp. 585–608). The Guilford Press. (2018).

Gao, Y. & Raine, A. Successful and unsuccessful psychopaths: A neurobiological model. Behav. Sci. Law 28, 194–210 (2010).

Ishikawa, S. S., Raine, A., Lencz, T., Bihrle, S. & Lacasse, L. Autonomic stress reactivity and executive functions in successful and unsuccessful criminal psychopaths from the community. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 110, 423–432 (2001).

Lilienfeld, S. O., Watts, A. L. & Smith, S. F. Successful psychopathy: A scientific status report. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 24, 298–303 (2015).

Kushlev, K., Radosic, N. & Diener, E. Subjective well-being and prosociality around the globe: Happy people give more of their time and money to others. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 13, 849–861 (2022).

Liebe, U., Schwitter, N. & Tutić, A. Individuals of high socioeconomic status are altruistic in sharing money but egoistic in sharing time. Sci. Rep. 12, 10831 (2022).

Lockwood, P. L. et al. Aging increases prosocial motivation for effort. Psychol. Sci. 32, 668–681 (2021).

Vanags, P., Cutler, J., Kosse, F. & Lockwood, P. L. Greater income and financial well-being are associated with higher prosocial preferences and behaviors across 76 countries. PNAS Nexus 4, pgae582 (2025).

Wu, J. et al. Social class and prosociality: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 151, 285–321 (2025).

Nero, N. et al. Severity of psychopathy in a community-recruited sample is indexed by increased social discounting [Code and data]. OSF. (2025).

Amormino, P. et al. Social discounting and anti-/pro-sociality: A meta-analysis and (short-form) replication. Pers. Individ. Differ. 247, 113447 (2025).

Hart, S. D., Cox, D. N., & Hare, R. D. Manual for the Hare psychopathy checklist: Screening version. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems (1995).

Cooke, D., Michie, C., Hart, S. D. & Hare, R. D. Evaluating the Screening Version of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist—Revised (PCL:SV): An item response theory analysis. Psychol. Assess. 11, 3–13 (1999).

Guy, L. S. & Douglas, K. S. Examining the utility of the PCL:SV as a screening measure using competing factor models of psychopathy. Psychol. Assess. 18, 225–230 (2006).

Skeem, J. L. & Mulvey, E. P. Psychopathy and community violence among civil psychiatric patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 69, 358–374 (2001).

Patrick, C. J. Operationalizing the triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Preliminary description of brief scales for assessment of boldness, meanness, and disinhibition. Unpublished test manual, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, 1110-1131 (2010).

Venables, N. C., Hall, J. R. & Patrick, C. J. Differentiating psychopathy from antisocial personality disorder: A triarchic model perspective. Psychol. Med. 44, 1005–1013 (2014).

Burt, S. A. & Donnellan, M. B. Development and validation of the Subtypes of Antisocial Behavior Questionnaire. Aggress. Behav. 35, 376–398 (2009).

Lyall, D. M. et al. Cognitive test scores in UK Biobank: Data reduction in 480,416 participants and longitudinal stability in 20,346 participants. PLOS ONE 11, e0154222 (2016).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Multimodel Inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in Model Selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 33, 261–304 (2004).

Mazerolle, M. J. _AICcmodavg: Model selection and multimodel inference based on (Q)AIC(c)_. R package version 2.3.3, https://cran.r-project.org/package=AICcmodavg (2023).

Borchers, H. pracma: Practical Numerical Math Functions_. R package version 2.4.4, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pracma (2023).

Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L. & Imai, K. mediation: R Package for Causal Mediation Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 59, 1–38 (2014).

Cutler, J., Nitschke, J. P., Lamm, C. & Lockwood, P. L. Older adults across the globe exhibit increased prosocial behavior but also greater in-group preferences. Nat. Aging 1, 880–888 (2021).

Thomson, N. D. et al. Fluid intelligence moderates the link between psychopathy and aggression differently for men and women. J. Interpers. Violence 37, NP3400–NP3426 (2022).

Pauli, M., Ölund Alonso, H., Liljeberg, J., Gustavsson, P., & Howner, K. Investigating the validity evidence of the swedish TriPM in high security prisoners using the PCL-R and NEO-FFI. Front. Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.704516 (2021).

Revelle, W. (2024). _psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research_. Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. R package version 2.4.6 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (2024).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163 (2016).

Laub, J. H. & Sampson, R. J. Understanding desistance from crime. Crime. Justice 28, 1–69 (2001).

Moffitt, T. E. Male antisocial behaviour in adolescence and beyond. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 177–186 (2018).

Bergstrøm, H. & Farrington, D. P. Psychopathic personality and criminal violence across the life-course in a prospective longitudinal study: Does psychopathic personality predict violence when controlling for other risk factors? J. Crim. Justice 80, 101817 (2022).

Virtanen, S. et al. Do psychopathic personality traits in childhood predict subsequent criminality and psychiatric outcomes over and above childhood behavioral problems? J. Crim. Justice 80, 101761 (2022).

Hare, R. D. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist— Revised 2nd edn. (Toronto: Multi-Health Systems, 2003).

Markowitz, A. J., Ryan, R. M. & Marsh, A. A. Neighborhood income and the expression of callous–unemotional traits. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 24, 1103–1118 (2015).

Dickinson, E. R., Adelson, J. L. & Owen, J. Gender balance, representativeness, and statistical power in sexuality research using undergraduate student samples. Arch. Sex. Behav. 41, 325–327 (2012).

Côté, S. & Willer, R. Replications provide mixed evidence that inequality moderates the association between income and generosity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 8696 (2020).

Doñate-Buendía, A., García-Gallego, A. & Petrović, M. Gender and other moderators of giving in the dictator game: A meta-analysis. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 198, 280–301 (2022).

Engel, C. Dictator games: A meta study. Exp. Econ. 14, 583–610 (2011).

Guo, Q., Sun, P., Cai, M., Zhang, X. & Song, K. Why are smarter individuals more prosocial? A study on the mediating roles of empathy and moral identity. Intelligence 75, 1–8 (2019).

Thielmann, I., Spadaro, G. & Balliet, D. Personality and prosocial behavior: A theoretical framework and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 146, 30–90 (2020).

Sleep, C. E., Weiss, B., Lynam, D. R. & Miller, J. D. An examination of the Triarchic Model of psychopathy’s nomological network: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 71, 1–26 (2019).

Andrade, C. The Inconvenient Truth About Convenience and Purposive Samples. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 43, 86–88 (2021).

van Lange, P. A. M., Schippers, M. & Balliet, D. Who volunteers in psychology experiments? An empirical review of prosocial motivation in volunteering. Pers. Individ. Differ. 51, 279–284 (2011).

Kaźmierczak, I., Zajenkowska, A., Rogoza, R., Jonason, P. K. & Ścigała, D. Self-selection biases in psychological studies: Personality and affective disorders are prevalent among participants. PLOS ONE 18, e0281046 (2023).

Stone, A. A. et al. A population-based investigation of participation rate and self-selection bias in momentary data capture and survey studies. Curr. Psychol. 43, 2074–2090 (2024).

Madden, G. J. et al. Delay discounting of potentially real and hypothetical rewards: II. Between- and within-subject comparisons. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 12, 251–261 (2004).

Coller, M. & Williams, M. B. Eliciting individual discount rates. Exp. Econ. 2, 107–127 (1999).

Kiehl, K. A. & Hoffman, M. B. The criminal psychopath: History, neuroscience, treatment, and economics. Jurimetrics 51, 355–397 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants who contributed their time and energy to this work. A.A.M. discloses support for the research of this work from the Lisa Heidi Michael Gift Fund and the National Science Foundation (NSF; grant # 2139925). N.N. discloses support for the research of this work from the Georgetown Patrick Healy Fellowship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization by N.N., M.D., P.F., and A.A.M.; Methodology by N.N., M.D., P.A., P.F., and A.A.M.; Formal Analysis by N.N., P.A., M.D., and A.A.M.; Investigation by N.N., M.D., P.F., M.S., L.P., K.D., V.A.T, and A.A.M.; Writing – original draft by N.N. and A.A.M.; Writing – review and editing by N.N., M.D., P.A., P.F., M.S., L.P., K.D., V.A.T., and A.A.M.; Funding Acquisition by N.N. and A.A.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks Drew Winters, Matthias Burghart, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review was single-anonymous OR Peer review was double-anonymous. Primary Handling Editors: Inti Brazil and Troby Ka-Yan Lui. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nero, N., Dressel, M., Amormino, P. et al. Adults with more severe psychopathy in the community show increased social discounting. Commun Psychol 3, 175 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00353-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00353-z