Abstract

Fairness is a fundamental social norm guiding human decision-making. Yet, much of our empirical understanding of fairness derives from controlled laboratory studies with homogeneous student samples, raising concerns about the ecological validity of experimental findings. Here, we tackle this challenge by introducing a citizen science, lab-in-the-field approach, embedding a classic fairness paradigm, the Ultimatum Game (UG), in a well-visited public space within a community: a museum. Over the course of 13 months, we recorded >18,672 decisions from a heterogeneous sample of volunteer members of the public. Each participant responded to four allocation offers from anonymous proposers (two generous, two selfish), with the option to view proposers’ past behaviour (previously generous vs. selfish), before deciding whether to accept or reject each offer. Results closely replicated classic UG effects, with unfair offers frequently rejected, confirming the presence of inequality aversion beyond the laboratory. Notably, the majority of participants chose to sample proposer-history information, and those who did showed heightened sensitivity to fairness violations. Specifically, selfish offers from a proposer who had previously acted generously to others elicited the strongest rejection rates, demonstrating that judgements of unfairness are shaped by expectations which emerge from voluntary information sampling. Furthermore, the ecologically enriched design helped uncover temporal and demographic patterns, namely an association between time-of-day and information-seeking behaviour, and an increased willingness to accept unfairness across age. Methodologically, by situating a foundational experimental paradigm in a community venue, our approach aims to provide a scalable model for studying decision-making in ecologically enhanced contexts and a framework for research seeking to examine authentic behaviours beyond the laboratory, ultimately helping to deepen our understanding of the crucial norms that shape society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Experimental tasks are essential tools in psychological research, generating crucial insights into the mechanisms underlying human decision-making. An open question, however, is the degree to which the peculiarities of typical experimental task settings (such as university laboratories) and conventional participant samples (usually graduate students) help to explain choices that are made in the wild. Specifically, while experimental designs promote methodological rigour, persistent concerns have been raised regarding the replicability and generalisability of laboratory-based results to real-world behaviour, where decision-making occurs in rich, socially nuanced contexts1,2,3,4. Given the ultimate goal of psychological research, to understand behaviour as it occurs in authentic and consequential situations, efforts to address constraints inherent in traditional experimental approaches, environments and tools remain imperative to advance the field.

Economic games have emerged as a particularly powerful set of experimental tools, leveraging frameworks such as Game Theory to help investigate how social norms, like fairness and reciprocity, guide behaviour in competitive or cooperative decision settings5,6. Among these, the Ultimatum Game (UG), a simple two-player bargaining game in which an individual must choose whether or not to accept a proposed resource division, has become especially influential in understanding how people respond to violations of fairness5,7. Over the past four decades, UG studies have significantly advanced our understanding of humans’ innate sensitivity to inequity, consistently showing that individuals are willing to incur costs, often substantial, in pursuit of the ideal of fairness8. Nonetheless, despite rich theoretical and empirical contributions, UG studies remain predominantly confined to laboratory-based settings with homogeneous, student samples1,2,9, constraining our understanding of fairness-related decision-making outside of carefully controlled and restricted conditions.

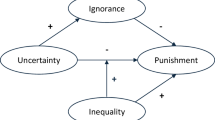

Bridging the aforementioned gap necessitates research approaches which capture decision-making in ecologically realistic settings from diverse participant pools, facilitating both replication of established fairness phenomena and discovery of previously unexplored behavioural patterns. In this regard, a core UG finding is that people frequently reject unfair offers, even at a personal cost, evidencing the widespread presence of inequality aversion8,10. However, acceptance rates are not solely driven by an aversion to inequality. Both behavioural11,12 and neuroimaging studies13,14 have revealed that beyond static payoff considerations, prior expectations of the decision-maker can significantly shape decisions. For example, when an individual anticipates a low, i.e. unfair, offer, they are more likely to accept it than when their expectation was of a higher, fairer offer11. That is, the congruence between a proposer’s past behaviour and current offer has meaningful implications on how a decision-maker responds to unfairness. Intriguingly, as the actual offer itself provides all the information needed for decision-making, such anticipatory beliefs are theoretically redundant. Yet, research has shown that incongruence, or deviations between a player’s expectations and the offer that is actually received, reliably influence responses to selfish offers and thus decisions about what is considered fair13,15,16. How precisely individuals form such expectations through information-seeking, however, remains poorly understood. Critically, this behaviour is difficult to study in conventional laboratory settings, where information presentation is tightly controlled and participants may feel obliged to engage with the task in predefined ways. Probing how people naturally sample information and form expectations thus requires more ecologically valid approaches in less controlled experimental environments in order to understand the processes through which information about others is authentically gathered and used to guide decision-making on unfairness.

The present study addresses these open questions through two primary objectives. First, we aim to test the presence of canonical fairness norms, notably inequality aversion, within a design that significantly enhances ecological validity and broadens participant diversity through a citizen science, lab-in-the-field approach. Second, we explore dimensions of fairness-related decision-making by testing two research questions within the ecologically enriched experimental setup: (1) Do people seek out non-instrumental information about a proposer’s past offers (captured through information sampling), and (2) if so, does the in(congruence) of a game partner’s behaviour impact judgements about unfairness. To achieve these goals, we embedded a modified-UG task within a community space attracting large numbers of the general public, namely a popular museum. This setup enabled the collection of decisions about fairness from a heterogeneous sample of public volunteers over the course of 13 months and across all hours of the working day. Participants opted in on-site and engaged with the paradigm without any experimenter present or extensive instructions, allowing us to capture authentic participant behaviour while testing established inequality aversion findings and examining the influence of voluntarily accessed information on responses to selfish proposals. Consequently, we hypothesised that fairness evaluations are influenced by information-sampling and expectation-driven processes. Beyond advancing empirical knowledge, our citizen science methodological framework aims to demonstrate the potential of utilising public-facing, ecologically enhanced designs. In doing so, it provides a scalable model for research efforts that seek to test and generalise laboratory findings, helping to broaden our understanding of the nature and universality of the fundamental social norms that govern human decision-making.

Methods

Participant inclusion and ethics

We conducted our study on a large and diverse sample of visitors to a local museum (muZIEum, Nijmegen, The Netherlands). Specifically, 11,205 participants engaged with our task through kiosks strategically placed in the waiting hall of a museum. Visitors could freely approach (and leave) the experiment at any time. Due to the placement of the kiosks in the museum waiting hall, the task was specifically designed to take less than 5 minutes to complete. Some participants thus exited the experiment prematurely when called to begin their museum tour. After applying pre-specified exclusion criteria, our final sample for analysis consisted of n = 4668 participants. Full details regarding participant inclusion and exclusion are provided in the ‘Analyses’ section below. The data were collected between 14 January 2022 and 1 March 2023. All participants gave consent for their data being used for scientific research. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Radboud University (ECSW-2021-076). The study and analysis plan were not pre-registered. Raw and processed data files (including R scripts with pre-processing steps) are available in the OSF repository: https://osf.io/m86uw/?view_only=2747290d0a2040eea058941719a1b96a.

Procedure and stimuli

The experiment was conducted without any experimenter present, using one of three 32-inch touchscreen kiosks (1920 × 1080 pixels) positioned in the waiting hall at ‘muZIEum’, a museum in the Netherlands dedicated to raising awareness about visual impairments. Museum visitors were invited to participate voluntarily as part of the ‘Donders Citylab’ project, a public science outreach programme (see Fig. 1B). To ensure visibility and comprehension of the study’s purpose, unsupervised kiosks were accompanied by printed advertising material that broadly introduced the task and encouraged participation from all museum guests. The experiment interface was programmed using Qualtrics and presented in either English or Dutch, based on participant selection.

A Overview of the task interface, displaying the pixelated image of a proposer (the ‘Game Partner’) along with five boxes (Sampling Screen). Participants could click on these boxes to view any of the previous five offers made by that proposer. This was followed by an Offer Screen containing a proposed division of coins, with radio buttons for accepting or rejecting the offer. B Physical layout of the experimental environment conducted at a well-visited museum, showing three unsupervised, touchscreen kiosks used for data collection.

This experiment utilised a within-subjects design, with all participants completing four trials. Given that our study was situated in the waiting area of a museum, the task (including instructions) was deliberately designed to be brief, anonymous, and hypothetical to maximise large-scale public participation that could be completed by participants within a short (i.e. less than five minutes) window.

On the start screen, participants encountered a welcome message that displayed an estimated experiment duration time of five minutes, along with a button to initiate the task. Once initiated, participants indicated whether they wished to proceed in English or Dutch. After choosing a language, participants were informed that they would be taking part in a brief decision-making task and were asked to provide informed consent. Participants were then prompted to report their age using a slider (continuous, ranging from 0 to 100, with default start position at 50) and to indicate their gender (categorical, ‘Man’, ‘Woman’, ‘Other’ or ‘Prefer not to say’).

Thereafter, participants proceeded to the UG task which commenced with the following instructions: “You will play a game in which you have to make decisions. You will participate as either Player A or Player B”. The roles were defined as follows: “If you are Player A, you’ll receive 100 coins and make other players an offer to distribute the coins. For example, you can offer to divide it equally, or to keep 60 yourself and give 40 away. If you are Player B, you’ll receive an offer. You can accept or reject it. If you do not accept the offer, you both get nothing.”. The use of the term “coins” was not linked to any specific currency.

Participants were informed they would complete four rounds, each involving a different counterpart. They then learned whether they were Player A or B. All participants in this study were assigned to the role of Player B, that is, they acted in the role of UG responder and received offers from four different game partners (i.e. Player As, also referred to in this manuscript as ‘Game Partners’), with the option to accept or reject each offer. Before receiving an offer, participants viewed a pixelated image of the Game Partner and were informed that they had the option to view that partner’s previous offers by choosing to open boxes that revealed past amounts offered (see Fig. 1A, ‘Sampling Screen’). Each Game Partner was associated with five boxes containing their prior offers, allowing participants to sample up to 20 items of information across all four Game Partners. Participants could sample any number of the five boxes per partner, providing flexibility in their information-gathering process. If sampled, this information revealed that Game Partners 1 and 3 had previously offered only generous offers (~20% of the coins kept for themselves; 80% offer to Player B), while Game Partners 2 and 4 previously offered only selfish offers (~80% of the coins kept for themselves; 20% to player B).

Following the Sampling Screen, participants advanced to an offer screen where they were informed of the actual offer from that Game Partner. Generous offers were received from Game Partners 1 and 4, respectively, with both proposing an allocation of 80% of the coins for the participant, and selfish offers were received from Game Partners 2 and 3, respectively, with both proposing less then 20% of the coins for the participant. Participants viewed trials in a Partner-by-Partner sequence. That is, each trial began with the choice to sample past offers of Game Partner 1, followed by Game Partner 1’s offer, then the choice to sample past offers of Game Partner 2, followed by Game Partner 2’s offer, and so on. This structure yielded both two congruent trials (i.e. when the partner’s current offer matched their prior behaviour as in Game Partners 1 and 2) and two incongruent trials (i.e. when the current offer deviated from prior behaviour as in Game Partners 3 and 4).

For each offer, participants could accept or reject the proposal by clicking on one of two radio buttons (see Fig. 1A, ‘Offer Screen’). After seeing offers from all four Game Partners, the experiment concluded with an educational debriefing. In addition, participants had the option to access a more comprehensive debriefing by scanning a QR code that linked to an outreach article on emotions and decision-making, available in both Dutch and English (English: https://blog.donders.ru.nl/?p=9075&lang=en; Dutch: https://blog.donders.ru.nl/?p=9070). Full experimental task instructions, with visuals of the trial sequence, are provided in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Note 1).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Analyses

Participant inclusions and exclusions

We excluded participants who completed less than 90% of the experiment (thus participants who completed all four trials, but chose not to read the full educational debriefing at the end were included in the analyses). We also included only those who self-reported their age as between 16–85 years old (n = 4668; Mage = 36.73; SD ± 15.62) (see Fig. S1 for age distribution of sample). Note: the slider was set to a default age of ‘50’, however, as only 58 responses were recorded at this default point (1.24% of total sample), we did not exclude participants whose chosen age reflected the default response). In the final sample included in this manuscript, 2744 self-identified as ‘Female’ (58.78%), 1750 identified as ‘Male’ (37.50%), 109 chose ‘Prefer not to say’ (2.34%), and 65 selected ‘Other’ (1.39%). The mean completion time for the task was 3 minutes and 23 seconds (±SD = 1 minutes, 22 seconds). Further highlighting the diversity of the sample, we provide information about the museum’s clientele in general in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Note 2).

Offer acceptance

Offers presented to the participant (current offer) were each categorised into ‘generous’ (from Game Partners 1 and 4) or ‘selfish’ (from Game Partners 2 and 3). Mean acceptance rates for both generous versus both selfish offers were computed as the proportion of acceptances (Accept vs. Reject) and statistically compared using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Sampling behaviour

To examine participants’ sampling behaviour, we recorded each unique decision to reveal historical information about a Game Partner’s prior offer on the Sampling Screen (Fig. 1A), where up to five boxes could be opened for each partner. Each box displayed an example offer consistent with the partner’s distributional profile, that is either consistently generous in the past (offering ~80% of the coins; Game Partners 1 and 3) or consistently selfish in the past (offering ~20% of the coins; Game Partners 2 and 4). Accordingly, Game Partners 1 and 2 represent congruent trials where their offer to the participant aligns with past behaviour, whereas Game Partners 3 and 4 represent incongruent trials where there is a deviation from prior behaviour, for example, when a proposer previously was shown to have made generous offers but now presents a selfish one to the participant, as in Game Partner 3. For each Game Partner, we aggregated the five sampling opportunities into a binary variable indicating whether the participant chose to sample at least one past offer (0 = Did not sample; 1 = Sampled (one or more boxes)).

Influence of sampling behaviour on offer acceptance

The influence of sampling behaviour (Did not sample vs. Sampled) on participants’ decisions to accept or reject offers was examined using a combination of descriptive and inferential statistical approaches. First, Chi-square tests of independence were performed to evaluate the association between sampling behaviour (Did not sample vs. Sampled) and decision-making (Accept vs. Reject) for each of the four offers. The direction of effects was assessed by comparing acceptance rates between sampling categories, and phi (φ) (Cramér’s V for 2 × 2 table) (with 95% CI) was calculated to quantify the strength of the observed association. Then, to model the relationship between sampling decision, offer, and acceptance decisions, a single mixed-effects logistic regression model was fit. Sampling behaviour (Did not sample vs. Sample) and Game Partner (as categorical variable, Game Partner 1–4) were included as interaction effects, with random intercepts for participants to account for repeated measures. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were further conducted to explore the nature of interactions. Finally, for the two selfish offers (Offers 2 and 3, respectively), iterative downsampling was performed with the goal of balancing group sizes between participants who chose to sample and those who did not, for each offer. This choice ensured we accounted for any possible fatigue or time-on-task effects which may have impacted the frequency of sampling across trials. For each iteration, a random sample of 690 participants was drawn from the larger group (‘Sampled’) to match the size of the smaller group (‘Did not sample’). This process was repeated over 1000 iterations for each of the offers. A fixed random seed was employed to ensure reproducibility. Logistic regression models were then fit for each iteration to predict acceptance decisions (Accept vs. Reject) based on sampling behaviour (Did not sample vs. Sampled) for each selfish offer. Median and mean odds ratios (ORs) (with 95% CI), mean p-value and proportion of iterations yielding p < 0.05 were calculated to assess the strength and stability of the sampling effect on acceptance rates. A complementary analysis estimated the mean difference in acceptance rates between participants who did and did not sample for each offer across all iterations. These differences were compared between Offers 2 and 3 using a Welch’s two-sample t-test, with effect size expressed as Cohen’s d (unpooled standard deviation (SD), 95% CI). Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested.

Demographic characteristics and temporal factors

To investigate the influence of demographic characteristics on sampling and acceptance decisions, we conducted two mixed-effects logistic regression analyses focusing on age (standardized) and gender (Man, Woman, Other, Prefer not to say). The first model examined how age, gender, and Game Partner (including an interaction between Game Partner and age) influenced participants’ decisions to sample partners. The second model assessed how age, gender, Game Partner, and prior sampling behaviour (including the interaction between sampling status and Game Partner) affected acceptance decisions. Both models included participant-level random intercepts to account for repeated measures.

To evaluate how time of day influenced behaviour, we fit separate generalized additive mixed models for sampling and acceptance decisions using the ‘mgcv::bam()’ function in R. Each model included a smooth term for time of day (measured in minutes since midnight) and a participant-level random intercept. These models were restricted to trials that occurred between the typical working hours of the museum, 09:00 and 17:00 (i.e. 540 to 1020 minutes since midnight). Sampling and acceptance were treated as binary outcomes and modelled using a binomial distribution with a logit link. Models were estimated using fast REML (method = “fREML”). Finally, to test for broader time-of-day effects across the full testing window, we conducted separate chi-square tests assessing whether sampling and acceptance decisions differed between trials that occurred before 12:00 (morning) and 12:00 or later (afternoon). All analyses were two-sided and conducted using R version 4.4.117.

Results

Inequality aversion is evident in an ecologically enhanced UG lab-in-the-field setting

The mean acceptance rate for the two generous offers (Offers 1 and 4) was high (92.31%). In contrast, the two selfish offers (Offers 2 and 3) had a substantially lower mean acceptance rate (34.24%) (see Fig. 2A). Acceptance rates differed significantly between the generous and selfish offers (Wilcoxon signed-rank test: V = 6,074,148, p < 0.001, rank-biserial r = 0.96 [95% CI 0.96–0.96]), indicating a higher acceptance rate for generous compared to selfish offers (see also Fig. S2A–C for within-subject consistency in rejection behaviour across offers).

A Proportion of accept and reject responses per offer type (n = 4668 participants). Blue bars represent mean acceptance rates; red bars indicate mean rejection rates for generous and selfish offers, respectively. B Proportion of accept and reject responses by sampling behaviour for each selfish offer (n = 4668 participants). Blue bars represent the proportion of participants who accepted the offer; red bars indicate the proportion who rejected it. C Odds ratios across 1000 iterations estimating the effect of sampling on offer acceptance. Coloured vertical lines show odds ratios from individual downsampling iterations (n = 690 per sampling group per iteration); smooth red lines and shaded areas reflect LOESS-estimated trends with confidence intervals. Odds ratios below 1 indicate reduced acceptance likelihood among participants who sampled. A discontinuity marker is shown on the y-axis, as no values fall below 0.5. D Difference in acceptance rates between sampling conditions. Density distributions of the difference in acceptance rates (‘Did not sample’ minus ‘Sampled’) across 1000 iterations for Offers 2 and 3 respectively. Vertical dashed lines indicate the mean difference per offer. Positive values reflect lower acceptance rates among participants who sampled.

Individuals choose to sample prior offers

Sampling patterns revealed a consistent tendency among participants to seek information about past offers. For Game Partner 1, 510 participants (10.93%) did not sample past offers at all, while the majority (89.07%), sampled between 1 and 5 boxes. Similarly, for Game Partner 2, 690 participants (14.78%) did not sample, with 85.22% of participants engaging in sampling prior offers. Game Partner 3 showed a similar pattern, with 837 participants (17.93%) choosing not to sample, and 82.07% of participants sampling between 1 and 5 boxes. Finally, for Game Partner 4, 976 participants (20.91%) did not sample, and 79.09% of participants choosing to sample. These results demonstrate a clear tendency towards choosing to sample past offers (See Table S1 for raw sampling counts per Game Partner, and Fig. S3 for sampling behaviour across Game Partners).

Decision to sample is associated with decision to accept selfish offers

The relationship between sampling behaviour (Did not sample vs. Sampled) and participants’ decisions (Accept vs. Reject) was first analysed for each of the Game Partners.

In respect of Game Partner 1 (congruency – consistent generosity), no significant association was observed between sampling and decisions for Offer 1 (X2(1) = 0.02, p = 0.88, φ = 0.002, 95% CI [0.00, 1.00]), that is, the likelihood of accepting the offer was nearly identical between participants who sampled (92.9%) and those who did not sample (92.8%). Similarly, for Game Partner 4 (incongruency – unexpected generosity), a non-significant association was found (X2(1) = 2.16, p = 0.14, φ = 0.022, 95% CI [0.00, 1.00]). Sampling increased acceptance rates minimally from 90.6% (Did not sample) to 92.0% (Sampled).

For Game Partner 2 (congruency – consistent selfishness), the association between sampling and decisions approached significance for Offer 2 (X2(1) = 3.50, p = 0.06, φ = 0.027, 95% CI [0.00, 1.00]). Participants who sampled were slightly less likely to accept this offer (31.5%) compared to those who did not sample (35.1%). For Game Partner 3 (incongruency – unexpected selfishness), the strongest association was observed (X2(1) = 23.87, p < 0.001, φ = 0.072, 95% CI [0.05, 1.00]). Sampling reduced acceptance rates from 43.8% (Did not sample) to 34.9% (Sampled), indicating that participants who sampled were more likely to recognise this game partner’s shift from generous past offers to selfish current behaviour, leading to increased rejection rates.

Across all Game Partners, a significant association, with largest effect, was observed only for Game Partner 3 whose profile captures unexpected selfishness. The proportion of accept and reject decisions, as a function of choices to sample past offers for selfish offers, are depicted in Fig. 2B.

Sampling information reduces acceptances rates for selfish offers

A single mixed-effects logistic regression model was fit to examine interaction effects of sampling behaviour (Did not sample vs Sampled) and offer (Game Partner 1–4), which also accounts for choice order, on the likelihood of accepting offers. The model included Participant IDs as random intercepts to account for repeated measurements across offers. Full regression outputs and post hoc comparisons are reported in the Supplementary Information (see Tables S2 and S3).

Overall, sampling did not significantly affect the odds of acceptance (β = 0.05, SE = 0.20, z = 0.23, p = 0.82, OR = 1.05 [95% CI 0.71–1.56]). However, acceptance odds differed substantially by Game Partner: compared to Game Partner 1, participants had significantly lower odds of accepting offers from Game Partner 2 (β = −4.01, SE = 0.22, z = −18.56, p < 0.001, OR = 0.02 [95% CI 0.01–0.03]) and Game Partner 3 (β = −3.52, SE = 0.21, z = −16.80, p < 0.001, OR = 0.03 [95% CI 0.02–0.04]), while odds for Game Partner 4 (compared to Game Partner 1) did not differ significantly (β = −0.28, SE = 0.22, z = −1.27, p = 0.20, OR = 0.80 [95% CI 0.5–1.17]). A significant interaction between sampling and Game Partner 3 emerged (β = −0.59, SE = 0.22, z = −2.69, p = 0.007, OR = 1.14 [95% CI 0.36–0.81]).

Furthermore, post hoc pairwise comparisons clarified the nature of the interaction within Game Partners 2 and 3, where participants who chose not to sample had significantly higher odds of accepting the selfish offers. Specifically, for Game Partner 2, not sampling increased acceptance odds by ~31% (OR = 1.31, 95% CI [1.05, 1.64], p = 0.017), and for Game Partner 3, not sampling increased acceptance odds by ~73% (OR = 1.73, 95% CI [1.41, 2.12], p < 0.0001). In contrast, sampling had no significant effect on acceptance odds for Game Partner 1 (OR = 0.96, 95% CI [0.64, 1.42], p = 0.82) or Partner 4 (OR = 0.84, 95% CI [0.63, 1.11], p = 0.21). The results thus indicate that in cases of a selfish offer, sampling reduced acceptance rates, with the strongest rejection rate occurring for instances of incongruent (i.e. unexpected) selfishness.

Selfish offers are less likely to be accepted when sampling reveals incongruent behaviour

To examine whether sampling differentially impacted acceptance for Offer 2 and Offer 3, iterative downsampling was performed separately for each of the selfish offers (n = 690). For Offer 2, sampling had a weak and non-significant effect on acceptance rates. Across 1000 iterations, mean OR was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.745–0.987, p = 0.23, proportion of iterations with p < 0.05 = 0.197, median OR = 0.85), indicating that participants who sampled were ~18% less likely to accept the offer compared to those who did not sample. This aligns with the expectation that participants anticipated consistent selfishness from Game Partner 2, with sampling providing little additional information to influence decisions. For Offer 3, sampling significantly reduced acceptance rates. The mean OR across 1000 iterations was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.599–0.789, p = 0.003, proportion of iterations with p < 0.05 = 0.99, median OR = 0.68), indicating that participants who sampled were ~45% less likely to accept the offer compared to those who did not sample. This stronger effect reflects participants’ sensitivity to the shift from generosity (past) to selfishness (current), with sampling reinforcing their decision to reject the offer (see Fig. 2C).

To further examine these effects, we analysed the absolute drop in acceptance for sampled versus non-sampled groups across the 1000 iterations for each selfish offer. For Offer 2, the mean drop in acceptance was 0.036 [95% CI 0.003–0.064]. In contrast, for Offer 3, the mean drop in acceptance was larger at 0.090 [95% CI 0.058–0.124]. A Welch’s two-sample t-test confirmed this difference, with significantly larger drops for Offer 3 compared to Offer 2 (t(1992) = −74.18, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.055, −0.052], Cohen’s d = 3.32 [3.18–3.45]; see Fig. 2D).

Accordingly, participants were more likely to reject a selfish offer when sampling revealed an incongruency between generous past behaviour and selfish current offer. In contrast, where selfishness aligned with prior expectations, sampling resulted in a weaker and non-significant effect on acceptance rates. These findings highlight how sampling amplifies participants’ reactions to incongruent behaviour of a game partner, when there is shift from past generosity to current selfishness.

Amount of sampling does not influence subsequent offer acceptance

An additional analysis treating sampling as a continuous variable (1–5 boxes opened per Game Partner) was conducted to assess whether the extent of sampling influenced subsequent offer acceptance. Compared to trials where participants sampled only one box, sampling two boxes (β = –0.31, SE = 0.64, p = 0.63, OR = 0.74 [95% CI 0.21–2.59]), three boxes (β = 0.33, SE = 0.69, p = 0.63, OR = 1.39 [95% CI 0.36–5.41]), or four boxes (β = –0.11, SE = 0.56, p = 0.85, OR = 0.90 [95% CI 0.30–2.67]) had no significant effect on acceptance rates. Moreover, interactions between sampling level and Game Partner were also largely non-significant at these intermediate levels. For example, for Game Partner 2 the interaction at three boxes opened was non-significant (β = 0.01, SE = 0.80, p = 0.99, OR = 1.01 [95% CI 0.21–4.88]); for Game Partner 3, the interaction at four boxes opened was similarly non-significant (β = –0.02, SE = 0.67, p = 0.98, OR = 0.98 [95% CI 0.27–3.62]), and for Game Partner 4, the interaction at two boxes opened showed no effect (β = 1.33, SE = 0.89, p = 0.14, OR = 3.77 [95% CI 0.66–21.6]). These findings suggest that increasing the number of sampled boxes did not systematically enhance or diminish the likelihood of accepting an offer, and thus that the decision to sample (Did not sample vs. Sampled) was more consequential than the quantity of information gathered.

Age and time of day differentially influence social-decision-making

To explore the impact of demographic variables, we analysed the effect of age and gender on sampling choices and decisions to accept offers through mixed-effects logistic regression with participants’ age and gender as fixed effects. Both age (β = 0.03, SE = 0.10, z = 0.26, p = 0.80, OR = 0.05 [95% CI 0.04–0.07]) and gender (reference ‘man’; woman (β = 0.13, SE = 0.20, z = 0.64, p = 0.52, OR = 1.14 [95% CI 0.77–1.69]); other (β = 0.02, SE = 0.83, z = 0.03, p = 0.98, OR = 1.02 [95% CI 0.20–5.19]) and prefer not to say (β = −0.69, SE = 0.61, z = −1.13, p = 0.26, OR = 0.50 [95% CI 0.15–1.66])) showed no significant effects on decisions to sample across offers. For decisions to accept or reject offers, age showed a significant positive effect, with older participants demonstrating higher acceptance rates overall (β = 0.09, SE = 0.03, z = 2.98, p = 0.003, OR = 1.09 [95% CI 1.03–1.16]) (see Fig. 3A), while gender did not significantly affect acceptance likelihood (reference ‘man’; woman (β = −0.05, SE = 0.06, z = −0.88, p = 0.37, OR = 0.95 [95% CI 0.84–1.07]); other (β = −0.18, SE = 0.25, z = −0.71, p = 0.48, OR = 0.84 [95% CI 0.51–1.37]) and prefer not to say (β = −0.12, SE = 0.20, z = −0.59, p = 0.56, OR = 0.89 [95% CI 0.61–1.31])).

A Acceptance probability as a function of age, shown separately for each UG offer. Lines reflect estimates from a mixed-effects logistic regression model with (shaded) 95% confidence intervals. B Sampling rates between 09:00 and 17:00, plotted by UG offer. Lines represent generalised additive model fits with (shaded) 95% confidence intervals. Raw participant counts (n) are displayed per hour bin along the x-axis (with total n = 4634, 34 participants falling outside 17:00 time window). A discontinuity marker is shown on the y-axis, as line values do not fall below 76%.

To examine how behaviour varied across time of day, we fit separate generalised additive mixed models for sampling and acceptance decisions. The model assessing sampling behaviour revealed a significant non-linear effect of time of day on the likelihood of sampling, s(time_minutes): edf = 4.86, χ² = 31.382, p < 0.001, indicating that participants’ tendency to sample varied over the course of the day (see Fig. 3B). To test whether sampling behaviour varied across the day while controlling for age, a further generalized additive mixed model was fit with a smooth term for time of day (in minutes since midnight), a participant-level random intercept, and age entered as a linear covariate. The smooth term for time of day was significant (edf = 4.86, χ² = 31.33, p < 0.001), indicating a non-linear time-of-day effect on sampling. Age did not predict sampling (β = 0.01, SE = 0.02, p = 0.80), suggesting that the observed time-of-day variation was not attributable to age differences among participants. In contrast, the model predicting acceptance decisions showed no statistically significant evidence for a time-of-day effect, s(time_minutes): edf < 0.001, χ² ≈ 0, p = 0.94.

These results were further supported by association tests. For sampling, the chi-square test revealed a significant association between time period (before or after midday) and sampling choices (χ² = 6.25, df = 1, p = 0.01), with greater sampling observed later in the day. Since our analyses identified a significant effect of time of day on sampling behaviour, we further examined whether age and time of day were related. While a Pearson correlation test showed a statistically significant correlation due to the large sample size (p = 0.04, 95% CI [0.0004, 0.029]), the effect size was trivial (r = 0.01), indicating no meaningful relationship between age and time of day. In contrast, analyses of acceptance decisions revealed no significant association with time of day (χ² = 0.15, df = 1, p = 0.70).

Discussion

Fairness-related decisions, particularly those assessed through classic economic tasks, such as the Ultimatum Game (UG), have predominantly been studied in carefully controlled laboratory environments with homogeneous student samples. This reliance has drawn strong critique regarding the external validity of experimentally derived decisions, specifically due to artificially constrained contexts, limited statistical power, and restricted sample diversity2,3,4. In response, efforts to enhance the ecological validity of experimental findings have included, for example, studies employing high-stakes scenarios18,19, as well as research engaging non-student populations and volunteers9,20. Nonetheless, methodological approaches which can help replicate and generalise laboratory findings outside of tightly controlled and restricted experimental setups are still required. Tackling this concern, we situated the foundational UG paradigm in an open and public space, namely within a popular museum. This citizen science, lab-in-the-field approach enabled data collection over the course of 13 months from a large-scale volunteer, community sample. With >18,672 decisions recorded, our study thus represents one of the largest single-study examinations of the UG conducted outside of the laboratory to date.

Our UG paradigm specifically sought to examine decision-making responses to both generous and selfish monetary proposals from (anonymous) game partners, where the participant must choose to either accept or reject these offers. Further, we gave participants the opportunity to explore how their game partners had behaved in the past, prior to making their decision. With this design, we aimed to test whether people seek out such non-instrumental information about a proposer and if so, whether the revealed (in)congruence of a game partner’s behaviour impacts judgements about unfairness. Importantly, as the task was embedded in a museum setting, visitors could engage with it voluntarily as they went about their day. Without any experimenter oversight or extensive tutorials, participants interacted with the paradigm in a self-guided manner. This structure enabled us to test canonical UG effects (notably inequality aversion) in an ecologically enhanced context, while also investigating previously unexplored dynamics of authentic information-seeking and its influence on social decision-making in a setup devoid of conventional experimental demands (e.g. quiet cubicles or controlled experimenter supervision).

The results closely replicate patterns of decision-making documented in controlled laboratory settings6,21. Unfair offers (~20% of the endowment) were rejected at significantly higher rates than generous offers, indicating widespread inequality aversion. Rejection rates closely align with those found in incentivised lab-studies, supporting evidence that fairness behaviours which emerge under traditional UG task conditions generalise to a more natural, real-world decision environment1. This result thus importantly highlights that established fairness norms are quintessentially present, even in a dynamic experimental setup.

Beyond classic inequity aversion effects, a key finding was that participants voluntarily sampled information about proposers’ past offers, and those who did, exhibited heightened sensitivity to fairness violations. Crucially, the sampling screen preceded the offer, allowing participants to access a game partner’s historical offer information before seeing their actual proposal. As the offer itself contains all necessary information for the decision, this information is strictly redundant. That a significant majority of participants nonetheless chose to sample information highlights the endogenous nature of information-seeking, emphasising its intrinsic utility, even when it holds non-instrumental value22. Importantly, participants who engaged with this information responded distinctly to fairness incongruency, showing elevated rejection rates to selfish offers when a game partner had previously been shown to be generous to others. This suggests that voluntarily acquired information helped form expectations about the game partner’s behaviour, which then shaped the evaluative process underlying fairness judgements. Our findings thereby extend previous work on expectation-sensitive norm violations12,13, showing that even in the absence of explicit instruction or instrumental benefit, individuals actively seek and strategically incorporate historical information about game partners to calibrate normative judgements in response to unfairness. These findings hold potential implications in settings where, for example, perceived behavioural consistency of others or reputational sensitivity may influence decision-making.

Through our diverse dataset, we further reveal both demographic and temporal influences on decision-making. The wide age range, spanning adolescents to senior citizens, helped uncover a clear pattern: age positively predicted decisions to accept proposals. This finding aligns with prior work suggesting that prosocial tendencies increase across the lifespan23,24,25. Several frameworks have been proposed to explain such a trend, including resource-based perspectives which suggest that as older adults often possess greater financial stability, the subjective cost of money sharing is reduced26. In addition, it has been suggested that motivational priorities shift with age towards helping others and society, which may similarly underlie the observed pattern25,27. Strikingly, while acceptance rates remained stable across the day, decisions to sample information varied across time, aligning with proposed diurnal patterns in exploratory behaviour and social curiosity28. In this regard, studies have shown that information-seeking, including in social contexts, tends to rise from morning to evening, potentially shaped by circadian rhythms in arousal and dopamine-driven motivation28,29,30. Furthermore, biological and cognitive rhythms affecting alertness and focus throughout the day have similarly been suggested to explain differences in information-seeking patterns29. Importantly, however, the impact of time-of-day on social decision-making has been largely unexamined, including in relation to paradigms on inequality and fairness more broadly. This gap is likely due to the logistical challenges and financial constraints of measuring fine-grained temporal patterns within the rigid constraints of conventional laboratory settings, where time is often uncontrolled rather than treated as a variable of interest. Our museum-based, naturalistic approach made it feasible to capture these temporal fluctuations, highlighting the stability of fairness norms over the course of the day, and a potentially underappreciated association between time-of-day and how individuals seek out information. Building upon this foundation, the causal mechanisms by which diurnal factors shape social decision-making represent an important open direction for future research. Such findings may hold implications for interventions or policies in contexts where decision-making is time-sensitive.

Notably, our methodological approach responds to calls highlighting the need for experimental approaches that preserve rigour while also enhancing ecological realism and scalability across diverse settings and populations31. In particular, our study contributes to growing efforts to embed behavioural paradigms in the wild, enabling scalable assessment of decision-making in environments that more closely reflect the contexts in which behaviour naturally occurs9,32. Unlike laboratory or online studies, our experiment was conducted in an unsupervised public space, without monetary incentives, researcher presence, or detailed instructions. While this brings certain limitations (discussed below), it also reduces demand effects and artificiality, as participants voluntarily engaged with the task as they went about their day and were thus not primed by typical experimental expectations or mindset. As such, the approach offers a scalable model for research that seeks to replicate and generalise laboratory-based findings in more naturalistic contexts. More particularly, the value of this design is threefold.

First, classic UG effects (including fairness sensitivity and context-dependent rejection) emerged robustly despite the relaxed constraints of our setup, aligning closely with prior lab-based results. Similarly, in order to balance ecological validity with practical feasibility, our design relied on hypothetical rather than incentivised choices, contributing to literature showing the convergence between hypothetical and incentivised behaviours33. In this way, the methodology not only allows for testing of previously established effects, but also serves to complement findings from more controlled designs34. Second, our naturalistic setup enabled the collection of continuous, large-scale data that revealed endogenous information-seeking, as well as demographic-temporal dynamics in decision-making. These represent phenomena often inaccessible or difficult to capture in typical laboratory setups, but which are nonetheless critical for understanding choice behaviour. Accordingly, the approach allows for both hypothesis testing and hypothesis generation regarding important aspects of decision-making and behaviour, including those that are challenging to probe in laboratory settings. Third, by embedding our paradigm within a citizen science framework, we engaged a broad public audience which diverges from typical university samples (particularly in age and educational background), providing richer population diversity and fostering voluntary community participation in scientific research. In doing so, the approach achieves dual benefits of research and outreach. To maximise this engagement, the task was kept brief, anonymous, and presented through a user-friendly interface with an educational debriefing that made participation both accessible and enjoyable.

Taken together, our methodology occupies an intermediate space between traditional, controlled experiment and large-scale observational study32, aiming to engage longstanding concerns regarding the ecological validity and generalisability of laboratory-based decision research2. Importantly, the approach can be seen as complementary to, for example, high-stakes, representative-sample, or supervised experiments by broadening the scope of settings in which economic and social decision-making can be observed. Public venues, such as museums, thus represent valuable and currently underutilised venues for behavioural experimentation which can help achieve rich data collection and meaningful community engagement. By answering the call for more ecologically grounded research through a cost-effective, controlled yet publicly accessible research design, this study offers a model for future research seeking to test established findings on decision-making processes and extend them into ecologically grounded contexts.

Limitations

Several important limitations of our approach and design should, nonetheless, be acknowledged. The museum-based context may introduce particular selection biases, as participation was voluntary and individuals could choose to disengage from the experiment at any point. This potential self-selection at the venue may have influenced the composition of the sample, and future research should examine the extent to which these findings generalise to additional decision settings or contexts. Moreover, while the environment of the museum setting introduced more dynamic, real-world decision-making conditions than are typical of laboratory studies, the uncontrolled nature of the experimental setup (including how busy or distracting the venue was on the day) might have affected participant behaviour in ways not fully accounted for in our analyses, for example, resulting in individuals participating multiple times or answering collectively. In respect of the design, our binary accept or reject format in response to highly generous and selfish offers constrains the granularity with which we can infer participants’ minimum acceptable offers (MAO). Further research could shed light on this by directly estimating MAO distributions, together with reaction times, to provide further detail on acceptance behaviour in such a lab-in-the-field setting. Similarly, the binary classification of sampling behaviour, while informative for addressing the present goals of this study, may underrepresent the complexity of information-seeking strategies. Although our results show that the amount of sampling did not materially impact choices, additional investigation into the gradations of sampling behaviour (including partial versus exhaustive patterns) could provide further insights into individual differences in information-seeking tendencies and their role in shaping expectations and decision-making.

Conclusion

The findings from this ecologically enhanced study highlight the robustness of fairness norms, extending prior laboratory findings to a non-standard and dynamic experimental context. Moreover, we highlight the role of authentic information-seeking in shaping expectations and fairness judgements, while emphasising the impact of demographic-temporal factors on such behaviours. Methodologically, our citizen science, lab-in-the-field approach underscores the potential of this framework as both a rigorous data collection tool and a means of engaging communities in experimental processes, achieving the dual benefits of research and outreach. Embedding research in public spaces can thus enrich psychological science, advancing scientific understanding and societal appreciation of the crucial social norms, including fairness, that ultimately shape society.

Data availability

Data is available at: https://osf.io/m86uw/?view_only=2747290d0a2040eea058941719a1b96a.

Code availability

Analysis scripts are available at: https://osf.io/m86uw/?view_only=2747290d0a2040eea058941719a1b96a.

References

Benz, M. & Meier, S. Do people behave in experiments as in the field?—Evidence from donations. Exp. Econ. 11, 268–281 (2008).

Camerer, C. F. et al. Evaluating replicability of laboratory experiments in economics. Science 351, 1433–1436 (2016).

Levitt, S. D. & List, J. A. What do laboratory experiments measuring social preferences reveal about the real world?. J. Econ. Perspect. 21, 153–174 (2007).

Open Science Collaboration Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349, aac4716 (2015).

Camerer, C. F. & Fehr, E. Measuring social norms and preferences using experimental games: a guide for social scientists. Found. Hum. Sociality Econ. Exp. Ethnogr. Evid. Fifteen Small-Scale Soc. 97, 55–95 (2004).

Sanfey, A. G. Social decision-making: insights from game theory and neuroscience. Science 318, 598–602 (2007).

Güth, W., Schmittberger, R. & Schwarze, B. An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 3, 367–388 (1982).

Güth, W. & Kocher, M. G. More than thirty years of ultimatum bargaining experiments: motives, variations, and a survey of the recent literature. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 108, 396–409 (2014).

Exadaktylos, F., Espín, A. M. & Branas-Garza, P. Experimental subjects are not different. Sci. Rep. 3, 1213 (2013).

Fehr, E. & Schmidt, K. M. A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 114, 817–868 (1999).

Sanfey, A. G. Expectations and social decision-making: biasing effects of prior knowledge on Ultimatum responses. Mind Soc. 8, 93–107 (2009).

Vavra, P., Chang, L. J. & Sanfey, A. G. Expectations in the Ultimatum Game: distinct effects of mean and variance of expected offers. Front. Psychol. 9, 992 (2018).

Chang, L. J. & Sanfey, A. G. Great expectations: neural computations underlying the use of social norms in decision-making. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 8, 277–284 (2013).

Xiang, T., Lohrenz, T. & Montague, P. R. Computational substrates of norms and their violations during social exchange. J. Neurosci. 33, 1099–1108 (2013).

Bogdan, P. C. et al. Social expectations are primarily rooted in reciprocity: an investigation of fairness, cooperation, and trustworthiness. Cogn. Sci. 47, e13326 (2023).

Civai, C. & Sanfey, A. In The Neural Basis of Mentalizing 503–516 (Springer, 2021).

Team, R. S. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. No Title (2021).

Andersen, S., Ertaç, S., Gneezy, U., Hoffman, M. & List, J. A. Stakes matter in ultimatum games. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 3427–3439 (2011).

Slonim, R. & Roth, A. E. Learning in high stakes ultimatum games: an experiment in the Slovak Republic. Econometrica 569–596 (1998).

Falk, A., Meier, S. & Zehnder, C. Do lab experiments misrepresent social preferences? The case of self-selected student samples. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 11, 839–852 (2013).

Camerer, C. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction (Russell Sage Foundation, 2003).

Mishra, J., Allen, D. & Pearman, A. Information seeking, use, and decision making. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 66, 662–673 (2015).

Fernandes, C. et al. Age-related changes in social decision-making: an electrophysiological analysis of unfairness evaluation in the Ultimatum Game. Neurosci. Lett. 692, 122–126 (2019).

Matsumoto, Y., Yamagishi, T., Li, Y. & Kiyonari, T. Prosocial behavior increases with age across five economic games. PLoS ONE 11, e0158671 (2016).

Pollerhoff, L., Reindel, D. F., Kanske, P., Li, S.-C. & Reiter, A. M. Age differences in prosociality across the adult lifespan: a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 165, 105843 (2024).

Li, D., Cao, Y., Hui, B. P. & Shum, D. H. Are older adults more prosocial than younger adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist 64, gnae082 (2024).

Midlarsky, E., Kahana, E. & Belser, A. Prosocial Behavior in Late Life (2014).

Gullo, K., Berger, J., Etkin, J. & Bollinger, B. Does time of day affect variety-seeking?. J. Consum. Res. 46, 20–35 (2019).

Piccardi, T., Gerlach, M. & West, R. Curious rhythms: temporal regularities of Wikipedia consumption. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media Vol. 18, 1249–1261 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Circadian rhythms in socializing propensity. PLoS ONE 10, e0136325 (2015).

Allen, K. et al. Using games to understand the mind. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1035–1043 (2024).

Vicens, J., Perelló, J. & Duch, J. Citizen Social Lab: a digital platform for human behavior experimentation within a citizen science framework. PLoS ONE 13, e0207219 (2018).

Brañas-Garza, P., Espín, A. & Jorrat, D. Paying £1 or nothing in dictator games: unexpected differences. Available SSRN 4723871 (2024).

Prissé, B. & Jorrat, D. Lab vs online experiments: no differences. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 100, 101910 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported through funding received from a Dutch Science Foundation (NWO) Grant 406.21.GO.015 to A.G.S. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The authors wish to thank the dedicated staff and volunteers at the muZIEum, as well as the members of the Donders Citylab initiative, including Yvonne Kuiper, for support and assistance throughout this project. We also wish to acknowledge and thank Dr. Stefan Prekovic who provided thoughtful discussions and constructive feedback on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.V.: Conceptualisation, study design, data processing and analysis, interpretation, writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. A.G.S.: Conceptualisation, funding acquisition, study design, interpretation, supervision, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks Damon Tomlin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Yafeng Pan and Jennifer Bellingtier. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vahed, S., Sanfey, A.G. Large-scale community study reveals information sampling drives fairness decisions. Commun Psychol 3, 178 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00354-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00354-y