Abstract

Acute stress triggers a cascade of physiological and psychological changes, including heightened perspiration, cortisol levels, and anxiety. Currently, little is known about the effects of acute stress on the quality of higher-order decision-making, with existing studies unable to disentangle decision-making capacity from subjective preferences. To address this gap, we conducted a within-participants laboratory experiment in which university students (n = 42) made objective decisions of varying complexity (computational hardness) under both acutely stressful and control conditions. We find that higher cortisol levels, induced via the Trier Social Stress Test, leads to lower decision quality and a higher incidence of experienced time pressure. Among cortisol responders, the deterioration in decision quality was independent of the level of computational hardness, whilst among the full sample it was concentrated among trials with higher levels of computational hardness. Post-hoc, we find that the most substantial deficits in decision quality occurred when acute stress was accompanied by time pressure, with gaze-tracking analyses offering tentative evidence that changes in attention allocation may be one mechanism for this effect. Our results demonstrate that acute stress impairs the capacity to decide correctly, and highlights the importance of computational hardness and time pressure as potential moderators of this effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many critical decisions in life are complex and made when under high levels of acute stress. Examples include whether to evacuate during a natural disaster, whether to obtain a loan in a financial emergency, and whether to proceed with a risky medical treatment in a medical emergency. At present, little is known about how acute stress affects complex decisions.

Stress is a ubiquitous experience occurring when a situation’s behavioural or physiological demands exceed an organism’s regulatory capacity1. Acute, or ‘in the moment’, stress triggers substantial physiological and psychological changes2. Physiologically, the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) axis activates the fight-or-flight response, heart rate and perspiration increasing within seconds of stress onset and returning to baseline within minutes post-stressor3. In parallel, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis instigates a slower stress response, releasing glucocorticoids, such as cortisol, to mobilise energy stores and inhibit non-essential functions such as digestion4. Cortisol levels increase within minutes of stress onset and remain elevated for 40–60 min post-stressor3.

Several brain regions show significant changes in activation under stress, leading to changes in behaviour which are adaptive in circumstances of fight-or-flight, but whose effects are less obvious in other decision-making contexts. Three brain regions particularly affected by acute stress include the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex5. The prefrontal cortex has been implicated in impaired performance under stress on tasks requiring complex and flexible thinking6. However, other studies have found shifts from serial-to-parallel processing7 or a reallocation of cognitive resources that leads to performance at least as good8, or better9, than that without stress. Thus, it appears that, depending on the task and the decision context, acute stress can lead to either impairments in functioning or a more efficient use of cognitive resources that preserves good performance10.

Psychologically, acute stress can be accompanied by states such as heightened alertness, fear or anxiety11,12. There is a growing consensus that acute stress impairs working memory13,14, cognitive flexibility, and planning15; while enhancing inhibition14, and learning from negative feedback or stress-relevant contexts16,17. However, moderators are critical, with results varying with, for example, levels of chronic stress18, stressor perception and timing19,20, or the type of flexibility or inhibition being measured21,22. Furthermore, acute stress’ effect tends to be impairing in probabilistic settings such as risky23, two-stage choice24, and explore/exploit tasks25. Yet, there seem to be little or mixed effects with regard to choice consistency26 and hypothetical real-world scenarios23. This makes it difficult to generalise from these studies to decision-making, particularly to situations of higher complexity.

Here, we investigate the effect of acute stress on decision time and the quality of decisions of varying levels of complexity. Participants completed the knapsack decision task (KDT; see Fig. 1 for details), a combinatorial computational problem based on the decision variant of the 0–1 knapsack problem27. It is closely related to the optimisation variant of the problem, where the objective is to determine the set of items that maximise value without exceeding the capacity constraint, and to the standard consumer choice problem in decision theory28. It approximates complex decision-making by recruiting several cognitive processes, including working memory, attention, cognitive control, and cognitive flexibility, and can be used to model any decision scenario involving costs and benefits: from grocery shopping to investment management29. Furthermore, the KDT is an objective task where we are free of potentially confounding subjective factors, such as individual preferences, and where random search is particularly ineffective.

Trial: A set of 8 items is shown, each with a value and a weight. A capacity constraint, target profit, and timer are shown at the screen’s centre. The goal is to decide whether there exists a subset of items for which (1) the sum of weights is lower or equal to the capacity constraint; and (2) the sum of values is at least the target profit. Nothing on the screen could be moved, selected or highlighted. Response: Participants selected Yes or No as their answer. Perceived difficulty: After each trial, participants rated its difficulty. Perceived stress: After every ninth trial, participants rated their perceived level of stress.

It has been shown that individual instances of such computational problems have mathematical properties which quantify their computational resource requirements (computational hardness)30,31. These properties predict human decision time and quality, both in the KDT and in other computational problems requiring abilities as diverse as spatial navigation and propositional logic32. Thus, our use of computational problems does not simply apply stress research to a different setting. Rather, it is an altogether more appropriate setting, relative to alternatives such as perceptual, executive functioning, or probabilistic tasks, for behavioural scientists interested in measuring and manipulating a decision’s complexity in a generalisable, theoretically sound, and empirically validated way.

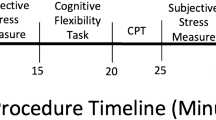

Each participant (n = 42) completed two sessions. In one, they underwent the trier social stress test (TSST; stress session) and in the other the placebo-TSST (control session)33. We collected salivary cortisol, skin conductance level (SCL), self-reported stress measures, and gaze tracking data in addition to 72 decisions in the KDT (see Fig. 2 for session outline). Our design allows us to quantify and manipulate both decision-makers’ stress levels, via the TSST, and the computational hardness of a decision. Our main hypothesis was that acute stress would reduce decision quality, and particularly so on harder instances of the task.

Five salivary cortisol samples and five iterations of the positive affect negative affect schedule (PANAS) were collected. Skin conductance level (SCL) was analysed for the rest period and the stress intervention, which was either the TSST (stress session) or placebo TSST (control session). Gaze tracking was recorded during the knapsack task. All timings, except where noted, were identical across all participants and sessions. ^Self-paced with a fixed start time. *Self-paced with a fixed end time. Icons for Fig. 2 made by Freepik from www.flaticon.com.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 42 participants (21 female, 21 male, 0 intersex, mean age 21.5 with SD = 3.6), predominantly university students, for an in-person laboratory experiment. Sex was self-reported from three possible options and data on ethnicity was not collected. Female participants were instructed to book experimental days that fell within the same phase of their menstrual cycle. 16 reported to be in the luteal phase, 3 in the follicular phase, and 2 in the menstrual phase. Both sessions took place in the same menstrual phase for all. To avoid anticipatory stress responses, the study was described as assessing “physiological and emotional responses to performance and decision-making tasks”34.

Each participant satisfied the following standard inclusion criteria22: aged 18–35 years, a body mass index of between 19 and 26, not diagnosed with a (acute or chronic) disease (psychiatric or somatic), not currently going through a period of stress, not on any medication, not in psychotherapy treatment, not taking oral contraceptives or with an irregular menstrual cycle, not pregnant, no history of substance abuse, not working night shifts, not to have slept in the two hours prior to a session, and not to have exercised, eaten, smoked, brushed their teeth, or drunk anything other than water within one hour of a session starting (no participants reported doing these within two hours of the session). Participants were paid a A$10 show-up fee for each session and were incentivised to give accurate answers with a A$0.7 payment for each correct response in the KDT. The average total payment was A$98.8 per participant. The experimental protocol was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (Ethics ID 23412).

Materials

Physiological and psychological measurements

We collected data on several stress measures, namely five salivary cortisol samples (HPA axis response), five samples of the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; subjective response)35, and SCL sampled at 64 Hz (SAM response). Additionally, every 9 trials, the participants rated how they were feeling on a scale of 0 (relaxed) to 5 (stressed), which we denote perceived stress (subjective response). Saliva samples were collected with salivettes and stored at −20 °C until analysis. SCL data were recorded using a Shimmer3 GSR+ and electrodes strapped around the base of the digit and middle fingers of their non-dominant hand.

Eye-tracking data were collected using a TobiiPro eye tracker with a sampling rate of 300 Hz, and Tobii Pro Lab software version 1.116.1. There were no head restrictions, participants were seated 60 cm from the screen, and the eye tracker was calibrated using a 9-point calibration. Eye positions were recorded for both eyes, and both horizontal and vertical gaze positions were recorded, where (0,0) was the top left corner of the screen and (1,1) was the bottom right corner. The task was done in a room with luminosity set to 40% and no natural light, at a 23.5-inch monitor at 1920 × 1080 resolution.

Experimental task: the 0–1 knapsack decision task

The KDT is based on the decision variant of the 0–1 knapsack problem27. On each trial, participants were presented with a set of items of different values and weights, a capacity constraint, and a target profit (see Fig. 1). Participants had to indicate whether there exists a combination of items whose combined value is at least the target profit and whose combined weight is at most the capacity constraint. Participants were instructed to solve the task as accurately as possible. An instance in which there exists a combination of items that satisfies both constraints is referred to as “satisfiable”; otherwise, it is called “unsatisfiable”.

Formally, an instance of this problem consists of a set of items I = {1, …, N} with weights {w1, …, wN} and values {v1, …, vN}, and two positive numbers c and p denoting the capacity and target profit (of the knapsack). The problem is to decide, yes or no, whether there exists a set S ⊆ I (a witness) such that \({\sum}_{i\in S}{w}_{i}\le c\) and \({\sum}_{i\in S}{v}_{i}\ge p\) (see Fig. 1 for more details). An instance for which a witness exists (does not exist) is satisfiable (unsatisfiable). All weights, values, capacities, and target profits used were integers.

In each session, participants completed 72 unique trials of the knapsack decision task (Fig. 1). Trials were self-paced, with participants having up to 40 s, determined with pilot testing, to proceed to the response screen. The response screen required them to select either Yes or No as their answer, with a maximum time limit of 3 s. The order of instances, the locations of items in an instance, and the sides of the Yes/No buttons on the response screen were randomised for each participant.

Each trial had two measures of performance: accuracy and time on task, operationalised as the proportion of the maximum available time used. Following each answer, participants rated the trial’s difficulty on a discrete scale from 0 (very easy) to 5 (very hard). Following every ninth trial participants rated their perceived stress on a discrete scale from 0 (Relaxed) to 5 (Stressed). There were no time limits on these ratings. Once a trial was completed, participants were shown a fixation cross for 10–13 s.

Instance sampling

Instances were evenly sampled from a 2 × 2 grid built from two variables: satisfiability and instance complexity (IC), our measure of computational hardness, as defined by Franco and colleagues31. Intuitively, IC measures the amount of computational resources an effective algorithm requires to solve an instance, where harder instances require more computational resources to solve. Formally, IC is the normalised distance between the target profit, p, and the maximum attainable profit, p*:

IC was used to measure computational hardness for three reasons. Firstly, IC is highly correlated with typical case complexity (TCC), a theoretically grounded, task-independent measure of computational hardness36, which has been shown to theoretically30 and empirically affect behaviour in the KDT and other computationally hard problems32. Secondly, IC is a more precise measure for the computational hardness of an individual instance. Whereas TCC is defined on average in relation to a random ensemble of instances, IC is defined precisely for an individual instance31. Thirdly, IC predicts performance equally well on satisfiable and unsatisfiable instances.

The value of IC is inversely proportional to the difficulty of the instance, and we randomly sampled 36 hard instances, IC ∈ [∣0.0268∣, ∣0.0321∣], and 36 easy instances, IC ∈ [∣0.0971∣, ∣0.105∣]. These parameters were chosen following pilot testing to target an average accuracy of 90% for easy instances and 70% for hard instances. For both easy and hard instances, half of the instances were satisfiable (unsatisfiable). Within the randomised order of instances, we divided the 72 instances into 6 blocks of 12, where each block had exactly 3 instances from each possible combination of hardness and satisfiability. This ensured that participants were exposed to a range of instances throughout the entire task. The task was programmed in Unity3d (version 2020.3.28f1) and administered on a desktop computer.

Procedure

Participants completed a stress and a control session on separate days, on average 4 days apart (SD = 5, range = [1, 23]), but at the same time of day. Sessions began either at 1 p.m. or 4 p.m., as natural cortisol levels are relatively stable in the afternoon37. The location, experimenter, equipment, procedure, and tasks were identical across sessions, except for the stress manipulation. In the stress session, participants underwent the TSST38, which has been shown to be a highly effective and reliable way to induce acute stress39. In the control session, participants underwent the placebo TSST33. Session order was counterbalanced across participants and sex.

The timeline of a typical session is detailed in Fig. 2. Firstly, participants gave informed consent and read through an outline of the experiment. Participants were informed that the ‘performance task’ (the stress intervention) would involve preparing a speech and speaking it aloud, and that this task would be observed by two ‘experts’ (confederates) in one of their two sessions. Secondly, they were introduced to the physiological measurements. This included a video explaining the saliva sampling procedure, eye tracker calibration, and being fitted with SCL sensors. Thirdly, participants went through instructions for the KDT, followed by eight practice trials. Fourthly, they completed a 15 min standing rest period to establish baseline SCL measurements. To improve salivary cortisol data reliability, participants were administered with 30 g of dextrose powder dissolved in 200 ml of water immediately prior to the rest period40. Once consumed, participants were administered with 100 ml of plain water. Fifthly, they went through the 15 min TSST or placebo intervention. Whilst participants were blind to session order, following the first session’s intervention, it was possible for them to deduce whether the following session’s intervention would be observed. Finally, they solved 72 instances of the KDT, which took ~60 min. The KDT was paused in between trials at three time points to allow for saliva and PANAS sampling (see Fig. 2). These pauses were typically 2–3 min long, and the eye-tracker was recalibrated prior to resuming the task. After the second session, participants were debriefed by the experimenter, including a pre-recorded video where the confederates in their stress session explained the purpose of the TSST.

Stress manipulation

The TSST procedure was primarily adapted from the canonical version41, as well as from a recent guide40. The anticipatory, speech, and arithmetic phases each lasted 5 min. The speech topic was “imagine you are applying for your dream job, persuade the hiring panel to hire you". The arithmetic task involved counting down from 2047 in steps of 17. The speech topic for the placebo TSST was “What are your hobbies?” and the arithmetic task involved counting from 0 in steps of 15.

Data analysis pipeline

Salivary cortisol

Salivary cortisol was analysed by Royal Melbourne Hospital Pathology using a Roche Cobas instrument and the Cobas e411 analyser42,43. We used the mean of the two pre-intervention saliva samples as the baseline for two reasons: firstly, to help reduce measurement error; and secondly, to account for both participants who arrived with abnormally high cortisol levels (t = 1) and those who may have become stressed from aspects of the experiment which preceded the stress intervention (t = 2).

Participants were excluded from analysis if their baseline salivary cortisol levels were more than 3 SD from the mean44. Participants were classed as cortisol responders if their cortisol level exceeded baseline by at least 1.5 nmol/L43,45, and both their peak and average cortisol levels were higher in the stress session than the control session.

Our primary stress measure was the area under the cortisol curve with respect to increase (AUCi), which was computed with the standard trapezoidal method and then z-scored46.

Skin conductance

An 8-minute window from the middle of the rest and stress intervention periods was used to compute SCL. The windows were identical for each participant, namely from T−10 to T−2 minutes, where T is the end of the period. Analysis was based on Taylor and colleagues47 and the code they made available on GitHub. The raw signal was passed through a 1 Hz, fifth-order, low-pass Butterworth filter, and then down-sampled to 5.22 Hz. This frequency was chosen to match the, on average, 11.5 s time window over which pupil diameter was computed. The median SCL for the rest period was treated as a baseline and subtracted from each point in the intervention period. Upon visual inspection of the data, 13 participants’ SCL data needed to be discarded: 12 due to recording quality problems and one for abnormally high readings during the stress intervention (more than 3 SD from the mean). This left 29 participants for analysis, of whom 21 were cortisol responders.

Eye tracking

Participants were instructed at time-of-recruitment that wearing glasses would render them ineligible, but that contact lenses were permissible. No participants wore glasses, and information on contact lenses, myopia, or astigmatism was not collected.

Gaze position data were down-sampled to 60 Hz. Each sample was then allocated to the nearest area of interest (AOI), either one of the eight items or the constraints of the knapsack. Samples automatically flagged as invalid, for example, due to blinks, were removed. Trials with data loss of at least 30% were discarded from further eye tracking analysis48. Samples were classified as a visit or a saccade based on the I-VT velocity algorithm49 used by Tobii Pro Lab, and here implemented using the CatEyes Python package (version 0.0.3)50. Saccades with an amplitude less than 1° were deleted, followed by visits of <100 ms48. Resulting visits were merged if they were <100 ms apart48. Precision was computed as the sample-to-sample root mean squared distance of the gaze data, averaged across participants. Precision was 0.20∘ and did not differ between conditions.

Following these standard methods, we applied two additional pre-processing steps. Firstly, we only retained trials where the cumulative time spent visiting AOIs was either at least 10 s or 60% of the time on task. This was done to ensure that participants were engaging with the task. Second, we only retained participants with a similar number of trials across easy vs. hard, satisfiable vs. unsatisfiable, and stress vs. control instances. Similarity was defined as having at least 6 surviving trials in each group, and the smaller group having at least 70% the number of surviving trials as the larger group. In total, 3.0% of trials were missing, 16.7% were omitted due to data loss, 4.8% were omitted due to a lack of visit time, and 9.4% were omitted due to imbalanced data. This left 3910 trials (66.2%) of trials across 30 participants for eye tracking analysis, of whom 21 were cortisol responders (71.9% of trials survived among responders).

To compute the average pupil diameter for a trial, we took the median pupil diameter of the following inter-trial-interval to avoid the confounding effects of the task on pupil diameter. We computed two pupil measures: the average pupil diameter across all trials and across only the first 12 trials. We expected the effect of the stress intervention on pupil diameter to be most pronounced at the beginning of the task and to return to baseline quite quickly. We used the first 12 trials as our cut-off for the beginning, as this is the earliest time point at which each participant would have completed an equal number of trials for every possible combination of easy, hard, satisfiable, and unsatisfiable instances.

Four main gaze tracking measures were analysed: the proportion of time spent visiting items, the number of items visited, the mean dwell time per visit, and the number of visits per second (visit rate). We computed these measures at the inter-trial level.

Main analysis

To account for individual differences in cortisol levels and task performance, we used hierarchical modelling with random effects on the intercept for each participant. We used three classes of regression models. Linear, logistic, and one-inflated beta regressions were used to predict unbounded continuous variables, binary variables, and bounded continuous variables, respectively. For the beta regressions, two participants were excluded as they took the maximum available time on more than 99% of trials.

Effect sizes were measured as Cohen’s d (d) for t-tests, odds ratios (OR) for logistic regressions, and standardised coefficients (β*) for linear regressions. For key analyses, effect sizes were additionally estimated as average marginal effects (AME), via the marginaleffects R package (version 0.24.0). Where relevant, we tested for interaction effects in nonlinear models via the second difference in marginal effects51.

If multiple models were considered, the AIC was used for model selection. The main focus of the analysis was cortisol responders, but the full sample (excluding cortisol outliers) was analysed in parallel and is reported in the Supplementary Information (SI; Section 1). All behavioural analyses included IC and satisfiability as binary variables, with 0 denoting easy instances and unsatisfiable instances, respectively, and 1 denoting hard instances and satisfiable instances, respectively. Furthermore, common control variables included sex (binary variable with males coded as 1s), session number (binary variable with the second session coded as 1s), and z-scored trial number. The independent variable used to assess stress was AUCi. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested.

To verify the robustness of our results, we repeated our main analysis with two alternative measures of stress: log cort Δ and the binary stress condition variables. The results of these analyses are reported in Sections 3 and 4 of the SI, respectively.

After removing one cortisol outlier, we had 41 participants, of whom 27 were classed as cortisol responders. SCL and eye-tracking pre-processing were performed in Python (version 3.9.12), and all statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.1.2) using RStudio. The study was not pre-registered.

The analysis proceeded as follows. First, we verified whether the stress manipulation was successful by comparing stress measures across the stress and control sessions. Second, we investigated the effect of stress on decision time, decision quality, and on the nature of participant responses. In doing so, we noticed a potential relationship between stress, whether participants ‘timed-out’ and used the maximum amount of time available to them in a trial, and decision quality. This was investigated as an exploratory analysis. Third, we performed an exploratory analysis on the effect of stress on participant gaze and attention allocation. Finally, we examined whether gaze affected the earlier analyses on decision quality and participant responses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Efficacy of acute stress manipulation

To verify that the acute stress manipulation was successful, we performed two-sided t-tests on each of the stress measures collected. Nearly all stress measures were higher in the stress condition (Table S1), both for the full sample and among cortisol responders.

To verify that AUCi, our primary stress measure, was representative of a broader stress response, we correlated it with our other stress measures. There were significant correlations between AUCi and the binary stress condition variable (t(52) = 5.86, ρ = 0.63, CI95 = [0.44, 0.77], p < 0.001), area under the cortisol curve with respect to ground (AUCg; t(52) = 10.25, ρ = 0.82, CI95 = [0.70, 0.89], p < 0.001), and perceived stress (t(484) = 2.32, ρ = 0.11, CI95 = [0.02, 0.19], p = 0.021). There were no significant correlations with negative affect (NA; t(52) = 0.58, ρ = 0.08, CI95 = [−0.19, 0.34], p = 0.564), pupil diameter (t(48) = 0.92, ρ = 0.13, CI95 = [−0.15, 0.40], p = 0.361), or SCL (t(40) = −0.36, ρ = −0.06, CI95 = [−0.36, 0.25], p = 0.718).

To verify that changes in cortisol, NA, and SCL occurred after the stress intervention, we plotted their time courses for the full sample. Cortisol and NA levels were not significantly different across the two conditions at baseline (Fig. 3A and B, Table S2). Both increased significantly after the stress intervention in the stress, but not the control, session. For cortisol levels, this group difference persisted for the remainder of the session, while for NA, the difference only persisted for the first two samples post-intervention. Further, pupil diameter was significantly higher for the stress session during the first block of trials (Fig. 3C, Table S2), those nearest the stress intervention, before dropping to a similar level for the remainder of the session. The difference between SCL in the stress intervention and the baseline rest period did not differ significantly between stress conditions (Fig. 3D, Table S2). Taken together, these results suggest the stress intervention drove the observed changes in cortisol, NA, and pupil diameter.

Data are from the full sample of participants. A Cortisol levels over time for the stress and control sessions (ns = np = 41), where ns and np are the number of samples and the number of participants at each time point, respectively. B Negative affect levels over time for the stress and control sessions. One observation is not shown for visualisation purposes† (ns = np = 41). C Pupil diameter by block for the stress and control sessions. Each point shows the median pupil diameter for a trial (ns ≈ 900, np = 38). Each block of the KDT had 12 trials, with 3 of each possible combination of {satisfiable vs. unsatisfiable} and {low vs high computational hardness}. One participant is excluded for missing at least half of the trials in a block. D Skin conductance levels for the stress and control sessions. Each point shows the median SCL for an 11.5 s bin (ns ≈ 2, 500, np = 29). The counterfactual samples the increase between rest and intervention for the control condition with replacement, and adds this to the stress SCL at rest. Centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, at most 1.5× interquartile range; points, individual observations; error bars, standard error of the mean. P-values are from two-sided t-tests with full statistics reported in Table S2. ∧p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS p > 0.1. †Stress condition, 80 min since intervention started, NA = 45.

Next, we sought to confirm that the changes in cortisol persisted throughout the session. We estimated a linear mixed-effects model regressing cortisol levels onto cortisol sample number, session number, session start time, sex, stress condition, a stress condition × cortisol sample number interaction, and a random intercept for each participant. Among cortisol responders (AIC: 1269.1, df: 239), we found a significant and positive stress condition × sample number interaction (β = 0.80, CI95 = [0.41, 1.18], β* = 0.19, p < 0.001), whilst the remaining variables, including the main stress (β = −0.65, CI95 = [−1.93, 0.62], β* = 0.30, p = 0.314) and time (β = −0.10, CI95 = [−0.37, 0.17], β* = 0.15, p = 0.477) variables, all failed to reach significance. Thus, cortisol levels increased over time in the stress session, over and above any corresponding changes in the control session.

The remainder of the results focus on cortisol responders, with the corresponding results for the full sample reported in the SI (Section 1).

Effect of higher cortisol levels on behaviour

KDT summary statistics

All but one participant completed all 144 trials of the KDT, instead completing 143 trials. Averaged across sessions, the mean accuracy was 79.5% (standard deviation (SD) = 6.7%) for all trials, 89.7% (SD = 7.0%) for easy trials, 69.4% for hard trials (SD = 9.9%), 77.2% for satisfiable trials (SD = 8.6%), and 81.8% for unsatisfiable trials (SD = 9.4%). The mean time on task was 32.1 s (SD = 4.4) for all trials, 30.3 s (SD = 4.8) for easy trials, 33.9 s (SD = 4.3) for hard trials, 30.9 s (SD = 4.8) for satisfiable trials, and 34.4 s (SD = 4.6) for unsatisfiable trials. As a benchmark, random performance would achieve an expected accuracy of 50%, whilst the maximum available time on task was 40 s.

Effect of higher cortisol levels on decision time in the KDT

To examine the effect of acute stress on decision time, we estimated a mixed-effects one-inflated beta regression, regressing time on task (measured as a proportion of the maximum available time) onto AUCi, IC, an AUCi × IC interaction, satisfiability, sex, session number, and z-scored trial number (AIC: 1549.1, df: 3,580). There was no significant effect of the interaction term (pcond. = 0.999, pinfl. = 0.554) or sex (pcond. = 0.221, pinfl. = 0.424), and the AIC improved when these variables were removed (AIC: 1543.5, df: 3,584). In the beta regression we observed significant and positive effects of IC (β = 0.35, CI95 = [0.28, 0.42], p < 0.001), and significant and negative effects of satisfiability (β = −0.27, CI95 = [−0.34, −0.20], p < 0.001) and trial number (β = −0.05, CI95 = [−0.08, −0.01], p = 0.007). There was no significant effect of AUCi (β = 0.02, CI95 = [−0.02, 0.05], p = 0.329) or session number (β = 0.01, CI95 = [−0.06, 0.08], p = 0.747). In the one-inflated logistic regression we found significant negative effects of trial number (β = −0.34, CI95 = [−0.42, −0.25], p < 0.001), session number (β = −0.45, CI95 = [−0.62, −0.28], p < 0.001), and satisfiability (β = −0.60, CI95 = [−0.77, −0.43], p < 0.001). There were significant positive effects of AUCi (β = 0.11, CI95 = [0.01, 0.21], p = 0.032) and IC (β = 1.00, CI95 = [0.83, 1.17], p < 0.001). Thus, higher cortisol levels were associated with the log-odds of ‘timing out’ and using the maximum 40 s available more often.

The marginal effect of a one SD increase in AUCi was a 1.7 percentage point increase (AME = 1.7%, CI95 = [0.2%, 3.3%], p = 0.031) in the probability of timing out. However, conditional on not timing out, higher cortisol levels had no significant effect on decision time (AME = 0.4%, CI95 = [−0.4%, 1.1%], p = 0.329, see also Fig. 4). In total, participants timed out on over a third of trials (1404 trials, 36.1% of the total).

Coefficients for the best-fitting models for predicting accuracy and time on task. The time on task model is a one-inflated beta regression with two component parts visualised separately, namely the conditional model (beta regression) and the one-inflation model (logistic regression). nt and np are the number of trials and participants included in the model, respectively. The best-fitting model for accuracy did not include trial number as a regressor. The coefficients for the interaction between computational hardness and AUCi are taken from separate models, as the interaction term was excluded from the best-fitting models. Error bars represent standard errors. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS p > 0.1.

Effect of higher cortisol levels on decision quality in the KDT

To test the effect of acute stress on decision quality, we estimated a logistic mixed-effects model regressing accuracy onto AUCi, IC, an AUCi × IC interaction, satisfiability, sex, trial number, and session number (AIC: 3649.1, df: 3,878). Time on task was omitted due to confounds with the IC and stress measures. There was no significant effect of the interaction term (p = 0.911), trial number (p = 0.482) or sex (p = 0.169), and the AIC improved when these variables were removed (AIC: 3645.5, df: 3,881). We observed a significant positive effect of session number (β = 0.18, CI95 = [0.02, 0.34], OR = 1.20, p = 0.031) and negative effects of IC (β = −1.37, CI95 = [−1.55, −1.20], OR = 0.25, p < 0.001), AUCi (β = −0.11, CI95 = [−0.21, −0.02], OR = 0.90, p = 0.015), and satisfiability (β = −0.31, CI95 = [−0.47, −0.14], OR = 0.73, p < 0.001) (see Fig. 4). This result implies a marginal effect whereby a one SD increase in AUCi is associated with a 1.7 percentage point (AME = −1.7%, CI95 = [−3.1%, −0.3%], p = 0.015) reduction in accuracy.

Next, we examined accuracy separately for trials in which participants timed out, as these were trials where participants were maximally time-constrained. Thus, they may represent trials where stress’ impairing effect is largest, and in a post-hoc analysis, we explored whether there was an interaction effect of acute stress and time pressure on accuracy.

Exploratory analysis of trials that timed out

As a starting point, we estimated a series of unpaired t-tests. Firstly, we compared accuracy on trials that timed out with those that did not and found that accuracy was significantly lower on trials that timed out (t(2, 471.6) = −8.38, μdiff = −11.80%, CI95 = [−14.56%, −9.04%], d = −0.30, p < 0.001). Secondly, we compared accuracy among trials that timed out across stress conditions and found significantly lower accuracy under stress (t(1, 400.1) = −2.38, μdiff = −5.69%, CI95 = [−10.39%, −1.00%], d = −0.13, p = 0.017). Thirdly, we compared accuracy among trials that did not time-out across stress conditions and found no significant difference (t(2, 476.7) = −0.71, μdiff = −1.05%, CI95 = [−3.95%, 1.85%], d = −0.03, p = 0.477). Fourthly, we found that the effect of time-out and stress was related to the satisfiability of the trial (Fig. 5 and Table S2). Specifically, the impairing effect of stress was largest for satisfiable trials that timed out. Finally, we compared whether the type of trial participants timed out on differed between stress conditions. For each possible combination of computational hardness and satisfiability, namely hard and satisfiable (t(485) = 1.79, μdiff = 4.32%, CI95 = [−0.44%, 9.08%], d = 0.09, p = 0.075), easy and satisfiable (t(968.85) = −0.36, μdiff = −0.98%, CI95 = [−6.32%, 4.35%], d = −0.02, p = 0.718), hard and unsatisfiable (t(485) = −0.24, μdiff = −0.62%, CI95 = [−5.62%, 4.39%], d = −0.01, p = 0.809), and easy and unsatisfiable (t(485) = 0.43, μdiff = 1.03%, CI95 = [−3.67%, 5.73%], d = 0.02, p = 0.667); we found no significant difference in time-outs between the stress and control conditions (see Table S6 in the SI for the full tests).

For visualisation purposes, points in panels A and B show the mean accuracy per participant, as all individual trials are at 0 or 1. However, the box plot is made from all relevant trials, not participant means. A Accuracy on satisfiable trials (solution is Yes), split by time-out status (nt,N ≈ 650, nt,Y ≈ 300, np = 26) and stress condition, where nt,Y and nt,N is the number of trials that did and did not time out in each condition, respectively, and np is the number of participants. B Accuracy on unsatisfiable trials (solution is No), split by time-out status (nt,N ≈ 600, nt,Y ≈ 400, np ∈ [25, 27]) and stress condition. C Mean dwell time on an area of interest, split by time-out status (nt,N ≈ 900, nt,Y ≈ 500, np ∈ [19, 20]) and stress condition. 7 outlier observations (values 500–1250 ms) are not shown for visualisation purposes. They do not influence the results, and their values are reported in the SI (Table S5). D Mean visit rate (visits to areas of interest per second), split by time-out status (nt,N ≈ 900, nt,Y ≈ 500, np ∈ [19, 20]) and stress condition. Each point in panels C and D is a trial. Centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, at most 1.5× interquartile range; error bars, standard error of the mean. P-values are from two-sided t-tests with full statistics reported in Table S2. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, NS p > 0.1.

To verify the effects apparent in Fig. 5A and B, we estimated a mixed-effects logistic regression. We regressed accuracy onto AUCi, time-out status, IC, satisfiability, session number, an AUCi × satisfiability interaction, a time-out status × satisfiability interaction, an AUCi × satisfiability × time-out status interaction, and an AUCi × time-out status interaction (AIC: 3572.2, df: 3,876). The model fit improved when the AUCi × time-out status interaction was removed (p = 0.261; AIC: 3571.5, df: 3,877). We found significant negative effects of time-out status (β = −0.65, CI95 = [−0.92, −0.37], OR = 0.52, p < 0.001), AUCi (β = −0.14, CI95 = [−0.27, −0.01], OR = 0.87, p = 0.031), IC (β = −1.27, CI95 = [−1.46, −1.10], OR = 0.28, p < 0.001), satisfiability (β = −0.26, CI95 = [−0.50, −0.02], OR = 0.77, p = 0.033), and the AUCi × satisfiability × time-out status interaction (β = −0.36, CI95 = [−0.63, −0.10], OR = 0.70, p = 0.008). The effects of the AUCi × satisfiability interaction (β = 0.16, CI95 = [−0.03, 0.35], OR = 1.17, p = 0.102), the time-out status × satisfiability interaction (β = −0.28, CI95 = [−0.63, 0.07], OR = 0.76, p = 0.115), and session number (β = 0.15, CI95 = [−0.02, 0.31], OR = 1.16, p = 0.084) were not significant.

The marginal effect of timing out was a 13.6 percentage point reduction (AME = −13.6%, CI95 = [−17.0, −10.2], p < 0.001) in accuracy. The marginal effect of a one SD increase in AUCi was a 0.7 percentage point reduction (AME = −0.7%, CI95 = [−2.0, 0.7], p = 0.317) in accuracy on trials that did not time out, and a 4.5 percentage point reduction (AME = −4.5%, CI95 = [−6.9, −2.0], p < 0.001) in accuracy on those that did. The difference between these effects was itself significant (AME = −3.8%, CI95 = [−6.1, −1.4], p = 0.002), suggesting that AUCi was only associated with lower accuracy on trials that timed out.

Having established that the effect of cortisol on accuracy differed between trials that timed out and those that did not, we next examined whether a similar interaction affected whether participants selected Yes or No as their solution.

Effect of higher cortisol levels and time-out status on response type

To test whether the nature of responding changed when stress and time-out status interacted, we regressed the submitted solution (Yes was coded as 1s) onto AUCi, IC, satisfiability, trial number, session number, time-out status, and a time-out status × AUCi interaction (AIC: 3866.5, df: 3,871). We found a significant negative main effect of time-out status (β = −0.42, CI95 = [−0.64, −0.21], OR = 0.66, p < 0.001), the time-out status × AUCi interaction (β = −0.26, CI95 = [−0.45, −0.06], OR = 0.77, p = 0.010), trial number (β = −0.11, CI95 = [−0.19, −0.03], OR = 0.90, p = 0.009), and session number (β = −0.19, CI95 = [−0.34, −0.03], OR = 0.83, p = 0.023). There was a positive effect of satisfiability (β = 2.79, CI95 = [2.63, 2.95], OR = 16.28, p < 0.001). There was no significant main effect of AUCi (β = 0.07, CI95 = [−0.03, 0.17], OR = 1.07, p = 0.176) or IC (β = −0.14, CI95 = [−0.31, 0.02], OR = 0.87, p = 0.078). These results indicate that, on trials that did not time out, higher AUCi was not significantly associated with the log-odds of submitting Yes as the solution. However, on trials that timed out, AUCi was associated with a relative decrease in the log-odds of responding Yes.

Having established the effects of cortisol on decision time, decision quality, and response type, we next investigated whether cortisol affected participants’ gaze and attention allocation.

Exploratory analysis of cortisol’s effects on gaze and attention

First, we investigated whether there were significant differences in gaze tracking measures between stress sessions. Via a series of unpaired t-tests, we found that participants attended to significantly more items (t(2, 531.8) = 3.47, μdiff = 0.1, CI95 = [0.04, 0.16], d = 0.13, p = 0.001) and had a significantly shorter dwell time per visit (t(2, 588.3) = −2.25, μdiff = −4.44, CI95 = [−8.30, −0.57], d = −0.09, p = 0.025) in the stress session (Table S8 of the SI). However, there were no significant differences in the amount of time spent visiting items (t(2, 793.9) = −0.99, μdiff = −0.34%, CI95 = [−1.01%, 0.33%], d = −0.04, p = 0.321) or in the number of items visited per second (visit rate; t(2, 775.9) = 0.86, μdiff = 0.01, CI95 = [−0.01, 0.03], d = 0.03, p = 0.392) between conditions.

Following our exploratory result that acute stress and time-out status interacted to affect decision quality, we tested for such an interaction effect on gaze and attention. Specifically, we tested whether our four gaze tracking measures remained significantly different between stress and control sessions among timed-out trials. In a series of unpaired t-tests, we observed that the gaze tracking measures only significantly differed between conditions among timed-out trials (Table S9 of the SI). In particular, under stress, participants spent less time visiting items, attended to more items, and dwelled on items for less time per visit (see also Fig. 5C and D).

To determine whether cortisol was driving these differences in eye movements, we next correlated items attended to, dwell time per visit, and visit rate with AUCi. AUCi was significantly correlated with items attended to (t(2, 794) = 4.57, ρ = 0.09, CI05 = [0.05, 0.12], p < 0.001) and visit rate (t(2, 794) = −4.81, ρ = −0.09, CI05 = [−0.13, −0.05], p < 0.001). Finally, we estimated a mixed-effects linear regression for each eye tracking measure, regressing it onto AUCi, IC, satisfiability, trial number, session number, and time on task. The best-fitting model for items attended to omitted trial (p = 0.432) and session (p = 0.263) number (initial AIC = 7235.1, df: 2,769). The best-fitting models for visit rate (initial AIC = 6159.4, df: 2,769) omitted IC (p = 0.172), satisfiability (p = 0.101), trial number (p = 0.127), and session number (p = 0.410), and for dwell time (initial AIC = 6966.7, df: 2,769) omitted IC (p = 0.167) and satisfiability (p = 0.854).

The regression analysis showed a significant positive effect of AUCi on items attended to (β = 0.05, CI95 = [0.02, 0.09], β* = 0.05, p = 0.004, AIC = 7221.7, df: 2, 771), but no significant effect on visit rate (β = 0.00, CI95 = [−0.03, 0.03], β* = 0.00, p = 0.849, AIC = 6135.8, df: 2, 773) or dwell time (β = −0.02, CI95 = [−0.06, 0.01], β = −0.02, p = 0.216, AIC = 6954.5, df: 2, 771). Thus, the mixed-effects models could only corroborate the significant t-test results for items attended to, but not for dwell time.

Turning to the role of decision time on gaze, the same regression analyses showed a significant positive effect of time on task on items attended to (β = 1.14, CI95 = [0.95, 1.33], β* = 0.23, p < 0.001) and dwell time (β = 0.26, CI95 = [0.08, 0.43], β* = 0.05, p = 0.004), but a significant negative effect on visit rate (β = −0.70, CI95 = [−0.85, −0.55], β* = −0.14, p < 0.001). Thus, spending more time on a trial was associated with attending to more items, dwelling on each item for longer, and switching between items less frequently.

Having investigated the determinants of gaze behaviour, we next looked to explore whether differences in gaze could predict differences in behaviour.

Incorporating gaze tracking measures into the analysis of decision quality

To test whether differences in gaze tracking measures could explain accuracy, in an exploratory analysis we estimated the best-fitting model from the initial accuracy analysis a further three times. Each new model included either items attended to, visit rate, or dwell time as a new regressor. Additionally, we included an interaction term between satisfiability and the relevant gaze tracking measures. This is because the pattern of search may differ when participants are searching for a combination of items that does meet the constraints (a witness), which exists only in satisfiable trials, as opposed to having to verify that no such witness exists, which is the case for unsatisfiable trials.

For items attended to (AIC: 2602.3, df: 2,788), we found a significant negative effect of satisfiability (β = −0.28, CI95 = [−0.48, −0.09], OR = 0.76, p = 0.004) and the interaction between items attended to and satisfiability (β = −0.55, CI95 = [−0.83, −0.29], OR = 0.58, p < 0.001). There was no significant main effect of items attended to (β = 0.14, CI95 = [−0.03, 0.30], OR = 1.15, p = 0.097).

For dwell time (AIC: 2606.8, df: 2,788), we found a significant negative effect of satisfiability (β = −0.30, CI95 = [−0.50, −0.11], OR = 0.74, p = 0.002) and dwell time (β = −0.17, CI95 = [−0.30, −0.05], OR = 0.84, p = 0.004), and a significant positive effect of the interaction between dwell time and satisfiability (β = 0.44, CI95 = [0.24, 0.66], OR = 1.55, p < 0.001).

For visit rate (AIC: 2,606.8, df: 2,788), we found a significant negative effect of satisfiability (β = −0.30, CI95 = [−0.50, −0.11], OR = 0.74, p = 0.002) and the interaction between visit rate and satisfiability (β = −0.43, CI95 = [−0.63, − 0.23], OR = 0.65, p < 0.001), and a significant positive effect of visit rate (β = 0.18, CI95 = [0.02, 0.33], OR = 1.20, p = 0.024).

For all three regressions, there was no qualitative change in the remaining fixed effects. These results indicate that the log-odds of accuracy on satisfiable trials were positively associated with attending to fewer items, dwelling longer on each item, and visiting fewer items per second. On unsatisfiable trials, the log-odds of accuracy was positively associated with dwelling shorter on each item and visiting more items per second. Having established the role of gaze tracking measures in predicting decision quality, we next examined whether they could also predict the type of solution submitted.

Incorporating gaze tracking measures into the analysis of response type

To verify whether our gaze tracking measures influenced the solutions submitted, in an exploratory analysis we re-estimated the earlier mixed-effects logistic regressions for solution submitted. For each regression, we added two additional regressors: the gaze tracking measure of interest and a three-way interaction between the gaze tracking measure, time-out status, and AUCi.

For items attended to (AIC: 2714.7, df: 2,780), the model fit improved when the trial number was omitted (p = 0.531; AIC: 2713.1, df: 2,781). We found significant negative effects of time-out status (β = −0.30, CI95 = [−0.55, −0.04], OR = 0.74, p = 0.022), the interaction between time-out status and AUCi (β = −0.23, CI95 = [−0.44, −0.01], OR = 0.79, p = 0.040), items attended to (β = −0.33, CI95 = [−0.46, −0.22], OR = 0.72, p < 0.001), and the interaction between time-out status, AUCi, and items attended to (β = −0.27, CI95 = [−0.54, −0.03], OR = 0.76, p = 0.035). There was no significant main effect of AUCi (β = 0.10, CI95 = [−0.01, 0.22], OR = 1.11, p = 0.088) and session number was no longer significant (β = −0.17, CI95 = [−0.36, 0.02], OR = 0.84, p = 0.088).

For dwell time (AIC: 2735.2, df: 2780) and visit rate (AIC: 2732.8, df: 2780), trial number (pdwell = 0.496, pvisit = 0.574) and the three-way interaction term (pdwell = 0.551, pvisit = 0.179) were not significant, and the model fit improved when these were removed. For dwell time, we found a significant positive effect of dwell time (β = 0.20, CI95 = [0.09, 0.32], OR = 1.22, p = 0.001, AIC = 2732, df: 2, 782). Session number was no longer significant (β = −0.18, CI95 = [ −0.37, 0.01], OR = 0.84, p = 0.066); however, IC became significant (β = −0.22, CI95 = [−0.41, − 0.03], OR = 0.80, p = 0.026).

For visit rate, we found a significant negative effect of visit rate (β = −0.22, CI95 = [−0.33, −0.11], OR = 0.80, p < 0.001, AIC = 2730.9, df: 2782). Session number was no longer significant (β = −0.16, CI95 = [−0.35, 0.03], OR = 0.85, p = 0.092); however, IC became significant (β = −0.23, CI95 = [−0.42, −0.04], OR = 0.79, p = 0.019). Unless otherwise specified, there were no qualitative changes among the other fixed effects for each of these models. This suggests that the log-odds of submitting Yes as the solution were positively associated with attending to fewer items, dwelling on an item for longer, and visiting fewer items per second.

Summary of differences in results between cortisol responders and the full sample

Only one key result was qualitatively different between analyses run on the full sample of participants and those run only on cortisol responders. Among the full sample, we observed a significant interaction effect between cortisol and computational hardness on accuracy. Specifically, higher cortisol levels only predicted significantly lower accuracy on harder trials. In contrast, among cortisol responders, the effect of higher cortisol on accuracy did not significantly differ between levels of computational hardness. Other minor differences were observed and are reported in Section 1 of the SI.

Robustness checks

We conducted three series of robustness checks for our results, for both cortisol responders and the full sample, which we report in the SI. In the section “Using log cort Δ rather than AUCi”, we repeated the analysis pipeline using another common measure of cortisol change, log cort Δ, as our primary stress measure24,25,52. Similarly, in section “Using the binary stress condition variable instead of AUCi”, we repeated the analysis pipeline using stress condition as our primary stress variable, rather than a cortisol-based measure. The majority of results were consistent across all three stress measures, though some were measure-dependent. For instance, the negative interaction effect between stress and IC on accuracy among the full sample only occurred with AUCi, but not with log cort Δ or stress condition.

Finally, in the section “Order effects”, we repeated the analysis pipeline whilst looking to control for session order effects. Key results, such as the behavioural effects of stress, were largely robust to the inclusion of order effects, though in some cases the results became more nuanced. However, some of the more exploratory results, particularly those that involved gaze tracking, appeared sensitive to session order.

Other exploratory analyses

We additionally conducted three post-hoc analyses, which we report in the SI. In the section “Using a trial-level cortisol measure”, we experiment with a trial-level estimate of cortisol levels, with mixed results. In the section “Comparing above- and below-the-median participant performance”, we find tentative evidence that the impairing effects of stress are concentrated among participants who performed above the median in the control session. Finally, in the section “Perceived difficulty and performance”, we find that perceived task difficulty is weakly related to computational hardness and that it is associated with higher decision time and lower decision quality.

Discussion

We used a controlled laboratory experiment to investigate the effect of acute stress on decision-making in the knapsack decision task, an objective task which models many everyday complex decisions29. Further, we measured within-task complexity as instance complexity, a measure of computational hardness inspired by computational complexity theory and capable of precisely characterising the hardness of individual decisions31. Our design allowed us to modulate both the computational resource requirements of the decision environment, via instance complexity, and decision-makers’ stress levels, via the TSST. We expected acute stress to have a detrimental effect on decision quality, and particularly so at higher levels of computational hardness, that is, in situations in which the computational resource constraints are more binding.

We find that, in response to an acute psychosocial stressor, higher levels of cortisol impaired performance in the KDT. Among cortisol responders, this effect was independent of the level of computational hardness. Among the full sample of participants, this impairment was concentrated among computationally harder trials, but only when stress was operationalised as the increase in area under the cortisol curve.

While others have argued that acute stress has an increasingly impairing effect on performance as the complexity of a decision or cognitive task increases6,12,53, these arguments have been limited in three ways. Firstly, prior studies tend to have a narrow focus on tasks that either isolate specific cognitive functions (e.g., executive functioning tasks) or can be difficult to disentangle from preferences (e.g., risk and uncertainty tasks). Secondly, these studies lack a formal framework with which to measure within-task complexity in a task-independent manner, making their complexity measures appear ad hoc. Thirdly, there is mixed evidence even among the tasks considered54,55. Having addressed those issues in our study, we offer evidence that higher cortisol impairs decision quality, even at low levels of computational hardness. Higher cortisol was also associated with an increased incidence of experienced time pressure, here defined as participants requiring the maximum time available to them in a trial, and post-hoc analyses showed the observed differences in decision quality and gaze occurred predominantly on trials with experienced time pressure.

Decision-making research across different disciplines has increasingly used a framework of ‘cognitive resources’ to describe the cognitive demands on decision-makers56,57. In these frameworks, constructs like energy, memory, and attention are cast as resources that are deployed in order to solve a problem or make a decision, with good decisions coming when the available cognitive resources meet or exceed those required by the task at hand. Along similar lines, the lens of a decision-maker engaging in information processing or computation has become widely adopted in cognitive science58,59. To the extent that stress can be considered a tax on cognitive resources60, our task provides an ideal way to investigate how reduced cognitive resources—by stress—affect decision-making at different levels of computational resource requirements.

Our ability to use precise, theory-driven, and widely generalisable metrics of complexity at the trial level left us uniquely placed to test for an interaction effect between acute stress and complexity on performance. To our surprise, we found no conclusive evidence for such an interaction among cortisol responders. Put differently, we cannot conclude that the performance decrement associated with higher cortisol levels differed between trials with high and low computational resource requirements. While we cannot rule out that a more precise measure of complexity would have captured an interaction effect, it would be surprising if our measure of instance complexity could near perfectly capture the expected effect of complexity, but not the dimension of complexity relevant to acute stress. What is more plausible is that stress affects a cognitive resource that is required independently of the computational resource requirements of an individual decision, e.g., cognitive control57. Among the full sample we do find the expected interaction effect, with the deficit in performance concentrated among trials with higher computational hardness. Thus, an alternative explanation is that the smaller sample size of cortisol responders and the relatively modest effect sizes we observed left us underpowered to detect an interaction effect among the smaller group.

Post-hoc exploratory analyses revealed a significant interaction between elevated cortisol, experienced time pressure, and satisfiability on performance. Under time pressure, higher levels of cortisol were associated with responding No more frequently. This more pessimistic pattern of responding is consistent with recent evidence that acute stress may lead to more pessimistic beliefs61 and a computational model where time pressure biases behaviour towards simpler response policies62, such as always responding No when a witness has not been found. As Fig. 5 makes clear, benchmarked against performance without time pressure, relative to the control session, this pessimistic behaviour led to a 7 percentage point increase in accuracy on unsatisfiable trials and an 18 percentage point decline in accuracy on satisfiable trials among cortisol responders. In absolute terms, accuracy fell by 25 percentage points on satisfiable trials, reducing performance to near-chance levels. It was performance on these trials that overwhelmingly drove the aggregate reduction in performance under acute stress.

We show that higher levels of cortisol affect performance on a non-deterministic polynomial time complete (NP-complete) decision-making task. For our purposes, NP-complete problems have four key features: they are ubiquitous, computationally hard at the problem level, their computational hardness varies considerably at the individual instance level, and NP-complete problems are mathematically related to each other, which suggests that findings in relation to one such problem are likely to generalise to all other NP-complete problems63. Indeed, empirically, measures such as instance complexity have been found to predict human performance beyond the KDT, to a diverse set of NP-complete problems requiring skills as varied as spatial navigation or propositional logic to solve32. Examples of other NP-complete settings include scheduling, budgeting, route planning, and event planning. Thus, the implications of understanding how stress affects such complex cognitive processes are vast, and further work is needed to test whether the effects observed here can generalise to other NP-complete problems.

We deployed gaze tracking analyses to investigate the potential cognitive mechanisms underpinning our results. We found tentative evidence that, among cortisol responders, the stress condition was associated with differences in attention allocation. Specifically, t-tests suggested that participants attended to more items and spent less time dwelling on each item under the joint effect of stress and experienced time pressure. However, these results could only be corroborated with mixed models for items attended to, but not dwell time, and were weaker for the full sample. Furthermore, a number of participants and trials were excluded during pre-processing, limiting our sample size and generalisability. Tentative as they may be, our data hint at a shallower attentional deployment under stress and time pressure, in contrast to prior work suggesting that the acute stress response can enhance attention, particularly selective attention10,22. If our data are supported by future, confirmatory work, this may be indicative of divided attention being more vulnerable to the effects of elevated cortisol levels64, given that the KDT requires the integration of two equally important attributes (weight and value). It would also be consistent with acute stress exacerbating time pressure’s purported effects of increased search across alternatives and less depth among alternatives65.

The gaze tracking analysis could also predict behaviour in the KDT. Specifically, we find that attending to more items, higher dwell times, and lower visit rates were associated with a higher likelihood of submitting Yes as a solution. Further, we find clear differences in how search affects performance across different levels of satisfiability. For satisfiable trials, where participants are searching for a witness, attending to fewer items, dwelling on items for longer, and switching between items less frequently were associated with higher accuracy. This is consistent with participants excelling when they could find a candidate witness quickly, and adopt a more targeted and focused search strategy. Conversely, on unsatisfiable trials, where participants are looking to prove that no witness exists, higher accuracy was associated with the inverse: attending to more items, dwelling on items for less time, and switching between items more frequently. This is consistent with a shallower and broader search strategy as participants try to rule out different combinations of items.

Our findings are consistent with a pharmacological study that administered dopamine agonists, namely methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine, to healthy participants solving the optimisation variant of the knapsack problem66. Whilst both drugs primarily increase dopamine levels, like acute stress, they also increase cortisol and noradrenaline levels67,68. The study found that participants took more time to solve instances of the task, showed lower performance, and more scattered search under drug66, consistent with our findings and neurobiological evidence that excess noradrenaline leads to less systematic search69,70.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Data recording issues with the skin conductance and eye tracking data limited our effective sample sizes for those analyses. Furthermore, despite a counterbalanced sample, we did observe notable order effects in the gaze tracking analyses. Consequently, we may be underpowered to detect relevant effects with those measures and any observed effects may be less likely to generalise. For this reason, we view those results as tentative in the absence of corroborating evidence from future confirmatory work. Similarly, the largest behavioural effects were observed in an exploratory analysis investigating the effects of timing out. Thus, whilst experienced time pressure appears to be a key moderator of behaviour in our task, the experiment was not designed to isolate and test for such an effect.

While cortisol levels were correlated in the expected direction with our other stress measures, many of these correlations did not reach statistical significance. While this is not uncommon in the literature71,72, it limits our interpretation of the results largely to changes in behaviour related to an increase in cortisol levels, rather than the acute stress response more broadly. This is particularly for results pertaining to the full sample, as these were more dependent on a cortisol-based measure of stress rather than stress condition. Similarly, while our behavioural data are consistent with more diverse samples that have solved the KDT29, we cannot be sure that our stress-related results generalise beyond our primarily university student sample.

Future work could test the generality of our findings with extensions employing a between-subjects design, more refined computational complexity measures, a more diverse participant pool, and other computationally hard tasks, such as the travelling salesperson problem. More broadly, the framework employed here could be applied to other settings which may affect the cognitive resources available to a decision-maker, such as chronic stress, mental illness, and ageing. Our exploratory finding that under the combined effects of elevated cortisol levels and time pressure participants exhibit a more pessimistic pattern of responding, and that performance is most impaired in this setting, should be directly tested in a future confirmatory study.

In conclusion, our study looked at the intersection of two crucial areas of decision-making research. Firstly, acute stress is highly prevalent in our everyday lives and significantly affects performance on a variety of decision-making tasks. However, the direction and size of these effects depends upon numerous moderating factors. Secondly, many decisions we make, including important decisions, are computationally hard and often have severe impacts on our well-being in areas such as finance and health. It is thus critical to understand how acute stress affects decision-making, not only in easy cognitive tasks, but also in computationally hard decisions. Our study addressed these gaps, providing empirical evidence that higher cortisol levels impaired decision performance in the knapsack decision task. For the full sample, this impairment only occurred on computationally harder decisions, whilst for cortisol responders, performance was reduced for both levels of hardness. An exploratory result showed that decision quality was most impaired when stress was accompanied by time pressure, with the magnitude of this effect warranting further study. Finally, our gaze tracking analysis tentatively suggests that differences in attention may be one possible mechanism for this effect, as attention appeared more scattered when jointly under stress and time pressure in some analyses, but not others. While there is much work to be done to understand the generality of this result and the cognitive processes underpinning it, our study provides a step towards a better understanding of how stress affects decision-making at varying levels of complexity.

Data availability

All the data reported in this study are publicly available on OSF.

Code availability

All the analysis scripts for this study are publicly available on OSF.

References

Koolhaas, J. et al. Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 1291–1301 (2011).

Sapolsky, R. M., Romero, L. M. & Munck, A. U. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr. Rev. 21, 35 (2000).

Starcke, K. & Brand, M. Decision making under stress: a selective review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1228–1248 (2012).

Rodrigues, S. M., LeDoux, J. E. & Sapolsky, R. M. The influence of stress hormones on fear circuitry. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 289–313 (2009).

Lupien, S. J., Juster, R.-P., Raymond, C. & Marin, M.-F. The effects of chronic stress on the human brain: from neurotoxicity, to vulnerability, to opportunity. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 49, 91–105 (2018).

Arnsten, A. F. T. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 13 (2009).

Gathmann, B. et al. Stress and decision making: neural correlates of the interaction between stress, executive functions, and decision making under risk. Exp. Brain Res. 232, 957–973 (2014).

Qin, S., Hermans, E. J., van Marle, H. J., Luo, J. & Fernández, G. Acute psychological stress reduces working memory-related activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 25–32 (2009).

Dierolf, A. M., Fechtner, J., Böhnke, R., Wolf, O. T. & Naumann, E. Influence of acute stress on response inhibition in healthy men: an ERP study. Psychophysiology 54, 684–695 (2017).

Plieger, T. et al. The impact of acute stress on cognitive functioning: a matter of cognitive demands? Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 22, 69–82 (2017).

Grace, C. et al. Concordance in salivary cortisol and subjective anxiety to the trier social stress test in social anxiety disorder. Biol. Psychol. 175, 108444 (2022).

Sandi, C. Stress and cognition. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 4, 245–261 (2013).

Schoofs, D., Preuß, D. & Wolf, O. T. Psychosocial stress induces working memory impairments in an n-back paradigm. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33, 643–653 (2008).

Shields, G. S., Bonner, J. C. & Moons, W. G. Does cortisol influence core executive functions? A meta-analysis of acute cortisol administration effects on working memory, inhibition, and set-shifting. Psychoneuroendocrinology 58, 91–103 (2015).

Johnson, S. B., Dariotis, J. K. & Wang, C. Adolescent risk taking under stressed and nonstressed conditions: conservative, calculating, and impulsive types. J. Adolesc. Health 51, S34–S40 (2012).

Schwabe, L., Wolf, O. T. & Oitzl, M. S. Memory formation under stress: quantity and quality. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 34, 584–591 (2010).

Yu, R. Stress potentiates decision biases: a stress induced deliberation-to-intuition (SIDI) model. Neurobiol. Stress 3, 83–95 (2016).

Knauft, K., Waldron, A., Mathur, M. & Kalia, V. Perceived chronic stress influences the effect of acute stress on cognitive flexibility. Sci. Rep. 11, 23629 (2021).

Gabrys, R. L., Howell, J. W., Cebulski, S. F., Anisman, H. & Matheson, K. Acute stressor effects on cognitive flexibility: mediating role of stressor appraisals and cortisol. Stress 22, 182–189 (2019).

Geißler, C. F., Friehs, M. A., Frings, C. & Domes, G. Time-dependent effects of acute stress on working memory performance: a systematic review and hypothesis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 148, 105998 (2023).

Goldfarb, E. V., Froböse, M. I., Cools, R. & Phelps, E. A. Stress and cognitive flexibility: cortisol increases are associated with enhanced updating but impaired switching. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 14–24 (2017).

Shields, G. S., Trainor, B. C., Lam, J. C. W. & Yonelinas, A. P. Acute stress impairs cognitive flexibility in men, not women. Stress 19, 542–546 (2016).

Duque, A., Cano-López, I. & Puig-Pérez, S. Effects of psychological stress and cortisol on decision making and modulating factors: a systematic review. Eur. J. Neurosci. 56, 3889–3920 (2022).

Otto, A. R., Raio, C. M., Chiang, A., Phelps, E. A. & Daw, N. D. Working-memory capacity protects model-based learning from stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20941–20946 (2013).

Lenow, J. K., Constantino, S. M., Daw, N. D. & Phelps, E. A. Chronic and acute stress promote overexploitation in serial decision making. J. Neurosci. 37, 5681–5689 (2017).

Nitsch, F. J., Sellitto, M. & Kalenscher, T. The effects of acute and chronic stress on choice consistency. Psychoneuroendocrinology 131, 105289 (2021).

Kellerer, H., Pferschy, U. & Pisinger, D. Knapsack Problems (Springer, 2004).

Gilboa, I., Postlewaite, A. & Schmeidler, D. The complexity of the consumer problem. Res. Econ. 75, 96–103 (2021).

Murawski, C. & Bossaerts, P. How humans solve complex problems: the case of the knapsack problem. Sci. Rep. 6, 34851 (2016).

Yadav, N., Murawski, C., Sardina, S. & Bossaerts, P. Is hardness inherent in computational problems? Performance of human and electronic computers on random instances of the 0–1 knapsack problem. In 24th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence—ECAI 2020 (eds. De Giacomo, G. et al.) (IOS Press, 2020).

Franco, J. P., Yadav, N., Bossaerts, P. & Murawski, C. Generic properties of a computational task predict human effort and performance. J. Math. Psychol. 104, 102592 (2021).

Franco, J. P., Doroc, K., Yadav, N., Bossaerts, P. & Murawski, C. Task-independent metrics of computational hardness predict human cognitive performance. Sci. Rep. 12, 12914 (2022).

Het, S., Rohleder, N., Schoofs, D., Kirschbaum, C. & Wolf, O. Neuroendocrine and psychometric evaluation of a placebo version of the ‘Trier Social Stress Test’. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34, 1075–1086 (2009).

Wemm, S. E. & Wulfert, E. Effects of acute stress on decision making. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 42, 1–12 (2017).

Watson, D., Anna, L. & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070 (1988).

Cheeseman, P. C., Kanefsky, B. & Taylor, W. M. Where the Really Hard Problems Are. In IJCAI'91: Proceedings of the 12th international joint conference on Artificial intelligence (eds. Mylopoulos, J. & Reiter, R.) (Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., 1991).

Allen, A. P., Kennedy, P. J., Cryan, J. F., Dinan, T. G. & Clarke, G. Biological and psychological markers of stress in humans: focus on the Trier Social Stress Test. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 38, 94–124 (2014).

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K.-M. & Hellhammer, D. The ‘trier social stress test’—a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28, 76–81 (1993).

Bali, A. & Jaggi, A. S. Clinical experimental stress studies: methods and assessment. Rev. Neurosci. 26, 555–579 (2015).

Labuschagne, I., Grace, C., Rendell, P., Terrett, G. & Heinrichs, M. An introductory guide to conducting the trier social stress test. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 107, 686–695 (2019).

Kudielka, B. M., Wüst, S., Kirschbaum, C. & Hellhammer, D. H. Trier social stress test. In Encyclopedia of Stress, 2nd edn, Vol. 3, 776–781 (2007).

Chiu, S. K., Collier, C. P., Clark, A. F. & Wynn-Edwards, K. E. Salivary cortisol on ROCHE Elecsys immunoassay system: pilot biological variation studies. Clin. Biochem. 36, 211–214 (2003).

Vogeser, M. et al. Multicenter performance evaluation of a second generation cortisol assay. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 55, 826–835 (2017).

Sandner, M., Zeier, P., Lois, G. & Wessa, M. Cognitive emotion regulation withstands the stress test: an fMRI study on the effect of acute stress on distraction and reappraisal. Neuropsychologia 157, 107876 (2021).

Miller, R., Plessow, F., Kirschbaum, C. & Stalder, T. Classification criteria for distinguishing cortisol responders from nonresponders to psychosocial stress: evaluation of salivary cortisol pulse detection in panel designs. Psychosom. Med. 75, 832–840 (2013).

Pruessner, J. C., Kirschbaum, C., Meinlschmid, G. & Hellhammer, D. H. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology 28, 916–931 (2003).

Taylor, S. et al. Automatic identification of artifacts in electrodermal activity data. In 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 1934–1937 (IEEE, Milan, 2015).

Hooge, I. T. C., Niehorster, D. C., Nyström, M., Andersson, R. & Hessels, R. S. Fixation classification: how to merge and select fixation candidates. Behav. Res. Methods 54, 2765–2776 (2022).

Salvucci, D. D. & Goldberg, J. H. Identifying fixations and saccades in eye-tracking protocols. In Proc. of the Symposium on Eye Tracking Research & Applications—ETRA ’00, 71–78 (ACM Press, 2000).

Gütlin, D. CatEyes v0.0.3 (GitHub, 2021). https://github.com/DiGyt/cateyes.

Mize, T. Best practices for estimating, interpreting, and presenting nonlinear interaction effects. Sociol. Sci. 6, 81–117 (2019).

Lighthall, N. R., Gorlick, M. A., Schoeke, A., Frank, M. J. & Mather, M. Stress modulates reinforcement learning in younger and older adults. Psychol. Aging 28, 35–46 (2013).

Plieger, T. & Reuter, M. Stress & executive functioning: a review considering moderating factors. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 173, 107254 (2020).

Lai, G.-J., Yeh, Y.-c, Lin, C.-W., Hsu, W.-C. & Wu, J. The interactive influences of stress, modality of stimuli, and task difficulty on verbal versus visual working memory capacity. Learn. Individ. Differ. 56, 119–127 (2017).

Long, G. M. & Mo, S. S. Interaction of arousal and task difficulty upon perceptual restriction. Percept. Mot. Skills 32, 259–264 (1971).

Lieder, F. & Griffiths, T. L. Resource-rational analysis: understanding human cognition as the optimal use of limited computational resources. Behav. Brain Sci. 43, e1 (2020).

Shenhav, A. et al. Toward a rational and mechanistic account of mental effort. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 40, 99–124 (2017).

Piccinini, G. & Scarantino, A. Computation vs. information processing: why their difference matters to cognitive science. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part A 41, 237–246 (2010).

Richards, B. A. & Lillicrap, T. P. The brain–computer metaphor debate is useless: a matter of semantics. Front. Comput. Sci. 4, 810358 (2022).

Vecchio, R. P. Theoretical and empirical examination of cognitive resource theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 75, 141–147 (1990).