Abstract

Cities are designed primarily for the benefit of humans but also provide habitat for other species. However, understanding how different components of urban vegetation and other features of urban spaces enable different species or species groups to live in the city remains limited. Here we show that, for the City of Munich, designed features of public urban squares strongly determine the occurrence of different species groups. While taxon richness and abundance increased with increasing ‘greenness’ of the square, different taxa responded to different square features, such as the proportion of lawn, the volume of shrubs and the density of trees, as well as the number of people or pets on these squares. Our results highlight that urban design for human needs affects other species that may cohabit these spaces. Consequently, planning strategies for biodiverse cities that aim to enhance human–nature interactions need to be multifaceted, considering the needs of humans and other taxa to create diverse living cities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

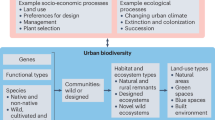

The number of people who live and work in an urban environment is expected to increase further, exceeding 65% of the global population in the coming decades1. Even though the biodiversity in cities is generally lower than in the natural habitats replaced by the urban environment, a surprisingly high number of species can occur in cities2,3,4,5, providing an important habitat even for threatened species, particularly in biodiversity hotspots6. In addition, urban nature is the nature that city dwellers can experience in their day-to-day life7,8 with multiple positive effects on urban inhabitants9,10. Therefore, there is widespread agreement today on the need to safeguard and increase biodiversity in cities11,12,13, which requires a better understanding of what drives biodiversity in the urban environment3,14.

Detailed assessments of plants and animals in the urban environment started only in the 1980s3,15,16, often using transects from outside a city to the city center or comparing species compositions between urban and nonurban areas7,17,18. These comparisons have shown that urban communities differ from those outside the cities so that certain traits and taxa are overrepresented19, for example, the Fringillidae (finches) and Columbidae (pigeons) among birds20. More recently, studies have begun comparing sites within cities and have found that urban communities are not homogeneous but that properties of the particular site in the urban environment determine what species can occur there14,21. In a large meta-analysis, the size of the green area within a city, the presence of corridors, that is, the surroundings of a site, and vegetation structure were important to explain local species richness for several taxa22. Importantly, taxa can differ in their responses to the features of urban sites23 and investigating the effects of individual site features in addition to the effect of overall green cover or greenness24 may allow a more detailed understanding of why certain taxa are common on certain sites.

Urban green spaces comprise a wide range of different forms and not only include large remnants of natural habitats and parks but also smaller vegetated areas such as backyards, gardens, neighborhood common areas, vacant lots and streets with trees, which have been shown to be important habitats for a variety of species25,26. Yet public green spaces in built-up areas are less intensively studied, so their contribution to urban biodiversity and which of their features affect different taxa remains to be investigated. This is an important knowledge gap because, in the built-up area of the city, that is, the area that is developed primarily for the needs of humans, biodiversity conservation competes with other priorities of city planning, such as economic growth, transport infrastructure and housing development27.

Here, we investigate how different features of urban squares affect the diversity of different taxa living on the squares. We focus on public squares (open spaces in a city without housing that are publicly accessible28) as a core element of cities that serve as important public spaces where city dwellers have gathered since ancient times29. Urban squares are characteristic of European cities established while these cities grew. However, urban squares also occur in cities on other continents, for example, in South America where they were established under European influence, in New Zealand and the United States, but also in Asia in countries such as China. Particularly in North America, where many cities were planned as a grid, urban squares are rare as public spaces such as town squares mostly consist of entire grid cells and often, but not always, have a park-like appearance. However, analogs to urban squares studied here occur frequently, for example, publicly accessible spaces in front of buildings or even shopping malls, that are not called a square but resemble the squares studied here in their features.

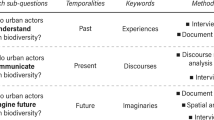

For our study, we selected 103 squares in Munich, Germany, differing in both the total amount and composition of urban vegetation, in particular trees, shrubs, grass and flower beds (Fig. 1, Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1). We characterized squares by a number of different features, including both vegetation-related variables and ‘gray’ characteristics relating to square design, including artificial light at night (ALAN) (Table 1 and Methods). Human usage of squares and the presence of domestic animals were quantified by counting humans on several days and times of the days using photographs. Because connectivity and habitat availability in the surrounding area have been shown to be important for biodiversity in urban environments22, we also calculated the percentage of green area in a buffer of 1,000 m around the border of each square. The squares investigated ranged from very ‘gray’, that is, being completely sealed, to very ‘green’, park-like squares, with different composition of urban vegetation, all a consequence of human design (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). In addition, squares differed widely in their attributes such the number of people.

Each stacked bar represents 1 of 103 public squares. Squares that are sorted by their total species richness and composed of six taxa are shown in individual colors (left, y axis). The blue and green lines are LOESS (locally estimated scatterplot smoothing) curves for multidiversity (summed, scaled richness of all taxonomic groups; right, y axis) and the proportion of green (right, y axis) with its 95% confidence interval (light-shaded areas). Images of squares highlight the variability in square features. Images of squares, from left to right, include Marienplatz, Hans-Mielich-Platz, Schäringerplatz, Johannisplatz and Pfrontener Platz, and highlight the variability in square features. Square images were taken by Antonia Haberer, 2024.

In a second step, we quantified the abundance and richness of birds (separately considering the feral pigeon), pollinators and other arthropods, the richness and activity of bats, the activity of small mammals, pest small mammal species (mice and rats), the richness of bryophytes (including mosses and liverworts) and spontaneous herbaceous vegetation on each square, using taxon-specific sampling methods (Methods). As a measure of overall diversity, we calculated a multidiversity index, summing the scaled richness of all taxonomic groups (Methods).

Squares differed greatly in biodiversity and the taxon richness of the most diverse square was almost eight times the richness of the biodiversity-poorest square (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Some species occurred on all or almost all squares, such as the flowering plants Plantago major and Taraxacum officinale (all squares), the silver bryophyte Bryum argenteum (93 squares) and the bird species carrion crow Corvus corone (92 squares) and great tit Parus major (94 squares). However, the vast majority of taxa occurred on a subset of squares, including species that are considered to be ‘urban species’. For example, among birds, the feral pigeon, Columba livia f. domestica, and the house sparrow, Passer domesticus, occurred only on 54 and 10 squares, respectively. Given the good coverage of the sampled communities (Supplementary Information 4), the observed variations in taxa distribution across the sampled areas suggest distinct ecological preferences.

As a first test for drivers of the biodiversity of squares, we fit linear models for the effect of greenness (proportion of green cover; Methods). Greenness on the squares positively affected both diversity and abundance/activity of all taxa, except for the abundance of feral pigeons, bat activity and richness, and pest mammal activity (Fig. 2). For taxa where both abundance (or activity) and richness were measured, the relationship to richness was stronger (Extended Data Table 1). Multidiversity was most strongly affected by greenness (F1,101 = 79.01 and P < 0.001; Fig. 2). These results emphasize the important role of planted vegetation for urban diversity, despite the fact that this urban vegetation was created predominately with human use in mind. Thus, the greening of cities benefits not only humans through better provisioning of ecosystem services30, but also other organisms, which in turn will enhance human–nature interactions31,32. Both the scatter around the regression lines and the differences in slopes between greenness and abundance/diversity of individual taxa suggest, however, that greenness is a coarse measure of the suitability of squares for organisms and that individual square features may offer better explanations as to where certain taxa occur. In addition to multidiversity, we also investigated the community composition of squares, based on all taxa studied (Methods), we found that while community composition changed along the green-to-gray gradient, there was ample additional variability in the occurrence of taxa, both among the greener squares as well as among the grayer squares (Extended Data Fig. 2). This also confirms the need to investigate the effects of individual features.

Each dot represents 1 of 103 public squares sampled between 2017 and 2018. The green graphs indicate a significant (P ≤ 0.05) relationship between how green a square is and the biodiversity measure. The gray graphs indicate no significant relationships. The lines represent the predicted values from linear models and the shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals (Extended Data Table 1). For effects of not-shown covariates, refer to Extended Data Table 1.

To test the effects of individual square features on urban biodiversity, we fit separate random forest models for multidiversity and each taxon’s richness and abundance/activity (Methods and Extended Data Table 2). These models, which excluded overall greenness, explained, on average, almost twice as much variance in the response variables compared with models with greenness only (greenness models: r2 = 0.239, Extended Data Table 1; random forest models: r2 = 0.433, Extended Data Table 2). Additionally, random forest models predicted the observed diversity well (Supplementary Figs. 3–16), confirming the hypothesis that the individual components of urban vegetation explain biodiversity better than overall greenness. Our analysis found that each taxon was affected by several square features (Fig. 3). To rank variables by the strength of their effects on biodiversity, we calculated importance scores (percentage increase in mean square error (m.s.e.); Methods) for each square feature. The proportion of green in the 1,000 m buffer around the squares positively affected only some of the taxa, including bat richness. For most taxa, however, local square features were more important for their abundance and diversity. This shows that the design of an urban square is pivotal for the biodiversity that can be found there. The proportion of lawn, shrub volume and tree density affected most biodiversity variables and were the strongest drivers of a square’s overall greenness (Fig. 3).

The rows represent the square features. The columns are the biodiversity measurements for eight taxa, multidiversity and greenness. The variable importance scores, percentage increase m.s.e. from the random forest models (Extended Data Table 2) are binned to six categories. Light gray represents NA values. Arrows represent the direction of the relationship. NA, not available. Icons reproduced from PhyloPic under a Creative Commons license CC0 1.0.

The proportion of lawn on a square affected most taxa positively and was the most important explanatory variable for multidiversity, bryophyte richness, arthropod abundance, arthropod richness and bird richness (Fig. 3). Lawns in the city are generally highly managed and therefore only occasionally allow taller plants to flower or set seeds; hence, they do not allow insect species that feed on shoots, flowers and flowerheads to complete their life cycles. However, they do provide habitat for soil-dwelling organisms and species living close to the surface, and hence also provide food for arthropod-feeding guilds, including birds, predatory arthropods, mammals such as the hedgehog33 and some bats, for example, Pipistrellus kuhlii and Pipistrellus pipistrellus34, both common in our study. We found lawns to have the highest abundance and second-highest richness of arthropods and the highest richness of spontaneous vegetation.

Several tree-related variables positively affected the biodiversity of the squares, in particular, tree richness and tree density (Fig. 3), both of which were also significant drivers of change in community composition as indicated by significant correlations among these environmental variables and the position of the square in the ordination of the biotic communities (Extended Data Fig. 2). Trees offer the highest vegetation biomass in cities and tree species differ in the resources they provide to different organisms. In our study, there were up to 25 species of trees on a square, whereby Norway maple (Acer platanoides; n = 1,179) and small-leaved linden (Tilia cordata; n = 1,044) were the most abundant. Interestingly, the proportion of old trees was not an important variable, despite old trees being disproportionally important for biodiversity worldwide35. There are a several potential reasons for this. First, our definition of old trees (diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 60 cm) includes trees that are <100 years old, that is, they are still relatively young; among all squares, there were only 17 trees with a DBH >100 cm. Second, the management of old trees in highly accessible urban areas dictates the premature removal of the tree or management of deadwood for public safety36, and this deadwood is one of the most important features of old trees for many species37.

Shrubs were the third most important feature on a square predictive for overall greenness and affecting biodiversity. Strong effects were found for the abundance and richness of birds and small mammals. Like trees, shrubs offer biomass, structure, resources and habitats in a city38. These can result from the shrubs themselves (for example, nesting sites in the shrub, flowers and berries) or from shielding areas inside or below the shrubs from disturbance or management (for example, for spontaneous herbaceous vegetation).

Features not related to the overall greenness of a square also affected several taxa. Square size, that is, total area, influenced the richness of spontaneous vegetation and bryophytes and the density of birds and small mammals, supporting the importance of urban patch size as found in previous studies22. Larger areas generally provide more and more diverse local habitats (that is, the species–area hypothesis39) and this may also hold for squares. Distance from the city center negatively affected pollinator abundance, pest mammal and bat activity, and positively affected bryophyte, small mammals and bat richness. Bryophytes, for example, are sensitive to the effects of urbanization, such as the heat island effect40 and air pollution41,42, both of which increase closer to city centers. In contrast, pest mammals are positively associated with the built-up areas of cities43. ALAN had negative effects on small mammal activity, bat activity and bat richness, that is, nocturnal taxa. While under certain circumstances, some bat and small mammal species may be able to exploit opportunities created by ALAN44,45, ALAN is agreed to negatively impact biodiversity46.

The number of humans visiting a square negatively affected a number of taxa and positively affected only feral pigeon abundance and pest mammal activity. The presence of humans has been shown to have negative effects even on highly urbanized species47,48, while some species, such as the pest mammals in our study, rely almost entirely on the resources created by humans. Community composition on squares was also significantly affected by ALAN and the number of people (Extended Data Fig. 2). While squares with the highest human disturbance were mostly completely sealed, we find that at intermediate greenness, squares characterized by high human disturbance, had different communities than squares with intermediate green but a smaller number of people active on the square (Extended Data Fig. 2). Water sources were rare on the squares (n = 18 squares) and the presence of water was not selected as important for any of the taxa.

Our results demonstrate that important features differ markedly between taxa and that there is not a single set of features that are optimal for all urban biodiversity. Some taxa, in particular birds and small mammals, were affected by a larger number of square features, while others, such as the richness of spontaneous vegetation and arthropods, only by a few variables (Fig. 3). While several taxa were strongly affected by variables related to shrubs, trees and lawns, birds were most influenced by several other green features. In contrast, small mammals were the least affected by the greenness variables of a square but were negatively influenced by the number of people on squares and ALAN, both indicative of disturbances. Similarly, bats showed a limited, negative effect of the greenness variables with the strongest influence being from disturbance variables. This suggests that for some taxa, either local green is not a factor, or some additional feature is more important, for example, connectivity (demonstrated to be important for common urban bats, for example, P. pipistrellus49).

While our study shows the potential of designing for both humans and biodiversity, there are also trade-offs and limits resulting from the different associations between features and taxa. For example, only some species benefit from increased tree density, and if high tree density implies a low proportion of open grassy areas, other species will be less likely to occur (Fig. 3). Further, lighting (ALAN) required to make people feel comfortable and safe during the night will negatively impact light-sensitive species such as small mammals and bats. As both the human use of squares and ALAN are related (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), implementing smart or wildlife-friendly lighting systems could provide people with the safety they need while reducing the impact on wildlife50. There are also limits to the simultaneous use of squares by both wildlife and humans, as indicated by the negative effect of human presence on the community composition and the abundance and richness of several taxa.

Conclusion

Our findings add to the growing body of evidence that urban vegetation benefits biodiversity in general. Thus, the replacement of sealed surfaces with grass or other vegetation by urban planners will result in immediate biodiversity benefits51. Extending beyond the general ‘green in cities begets biodiversity’, we showed that differences in square design and the type and amount of vegetation planted affected what organisms could live on the squares, ranging from bryophytes and flowering plants to arthropods, birds and small mammals. This is important, as in the discussion of creating a green infrastructure for cities, ‘green’ is often not qualified, suggesting that it does not matter what is grown. Although we often used coarse categories (trees, shrubs, lawns and flower beds), our study found striking differences in the effect of these different components on the biodiversity of the square. It is likely that describing the urban form in more detail, in particular the planted vegetation, but also other structures such as nesting possibilities for animals in buildings, will unravel further relationships between the design of a particular site in the city and the associated biodiversity. As our study was restricted to Munich, we recommend that comparable studies be carried out in other regions to determine how local biodiversity responds to the urban form.

Our study emphasizes that in the city, plants and wildlife not only occur in remnants of natural habitats or large parks but also in the built-up area of the city12,25. Our analysis showed that the way humans design a public urban square, a structure made for human use and central to urban life, strongly influences the biodiversity inhabiting these squares. Importantly, our findings are not limited to the biodiversity on public squares in Europe but are expected to be valid in other regions of the world where forms of public squares also exist, and they are likely to apply also to other categories of public and potentially private spaces. The square features included in our study were planned and implemented by humans for humans; all other organisms, including spontaneous vegetation, assembled on the square as a consequence of this design. The strong effects we found of this design on the biodiversity of urban squares emphasize that urban planners and landscape architects have an important role to play in creating biodiverse cities where human–nature interactions are possible. Embracing different greens in urban planning and design by creating diverse and heterogeneous sites will benefit various taxa, thus contributing to maintaining and increasing city-wide biodiversity.

Methods

Square selection

We calculated the size of 354 public squares (‘Platz’ in German) in the City of Munich, Germany (48.1372, 11.5761) using Google Earth and ArcGIS. As size was log-normally distributed, we conducted a stratified random sampling using five equally sized classes (Supplementary Information 1), resulting in 95 squares. Characterization of the squares using Google Earth and ArcGIS showed that they had good distribution in their distance to the city center (Marienplatz) and the presence of trees. As squares without tree cover were underrepresented, an additional eight were manually selected, resulting in 103 squares (Extended Data Fig. 1).

Square characterization

Squares were characterized by their features used as explanatory variables for the analysis of biodiversity on the squares (Extended Data Table 1). First, we delineated the borders of each square (far edges of roads, private property boundaries, walls and adjacent buildings) using aerial images and land register maps (Supplementary Information 1). We then calculated the size of each square (0.086–6.71 ha) using ArcGIS. Distance from center was calculated as the direct line distance from Marienplatz to the center of each square. Using the aerial images, we calculated the normalized difference vegetation index for each 20 cm pixel and determined the area and proportion of greenness of each square (normalized difference vegetation index with a threshold ≥0.2). To understand whether there was an influence of green in the surroundings of each square, we calculated a buffer of 1 km from the edge of each square. We used the same method above to determine the surrounding greenness (proportion of green).

Using aerial images, land register maps and Google Earth, we determined the proportions and areas of different surface cover types. We calculated the area and proportion of lawns (grass), area of shrubs, proportion of flowers (flowering plants), gravel and sand. The total unsealed surface area was calculated by adding the different surface cover types and the sealed surface area by subtracting the unsealed surface area from the total area (Supplementary Information 1).

Vegetation was further characterized by measuring on-site shrub volume (m3), tree (species) richness and abundance. We also calculated tree density per 100 m2 (tree abundance × 100/area (m2))52. Each tree’s DBH was measured to derive the median DBH and variability of DBH (coefficient of variation) (Supplementary Information 1). We determined old trees to be those with a DBH greater than 60 cm and then calculated the old tree abundance and old tree proportion (proportion of all trees with a DBH greater than 60 cm) for each square.

To assess human disturbance and impact on each square, we measured the number of people on each square, the number of streets associated with a square and ALAN. To assess the number of people, we took four photos from the center of each square, one in each cardinal direction. Photographing was repeated on three different days, each covering a different time (morning, midday and afternoon). The number of people in each photo was then summed and the mean total for all days was calculated. Using Google Earth, we counted the number of streets touching the boundaries of each square. Finally, we calculated the ALAN as the average gray value per square using Luojia-1 satellite images (Supplementary Information 1).

While reviewing the satellite imagery and visiting the squares, it was additionally noted whether a square contained a water source as the presence of water (for example, fountains).

Biodiversity assessment

Multidiversity

We calculated a multidiversity index53 for all the richness variables (arthropods, bats, birds, bryophytes, pollinators and vegetation) as the average proportional species richness across taxonomic groups. To ensure equal weight for all taxonomic groups, we standardized the species richness values by scaling them to the highest observed value across all squares. The scaling ensures that undue weight is not given to taxonomic groups with higher species richness. The average by square is then calculated as multidiversity.

Arthropod abundance and richness

We collected arthropods between May and July 2017 on five habitats per square: sealed surfaces (paved or tarmac), grassy areas, flower beds (not planters or raised beds), shrubs and trees. All habitats on a square were sampled once at a single point on the same day between 09:00 and 19:00 (Supplementary Information 2). Surface habitats were sampled by suction sampling54,55 using a battery-operated leaf blower outfitted with a gauze filter using a cage covering an area of 0.25 m2 (Supplementary Fig. 2.1). Trees and shrubs were sampled using knockdown sampling and collecting the arthropods in a funnel attached to a sample jar. In the laboratory, all individuals were sorted to order level (Supplementary Table 2.1)56. We then calculated the taxonomic group richness per square and the abundance per square as the total number of arthropods for each taxonomic group collected across all sampled habitats.

Bat activity and richness

We undertook bat sampling on single nights, from 1 h before sunset to 1 h after sunrise, between June and October 2017. All squares were sampled four times in clusters of 2–15 squares using ultrasonic recorders (ecoObs Batcorder 3.1 (quality of 20, threshold of −36 dB, post trigger of 800 ms and critical frequency of 14 kHz (ref. 57))). Clusters were chosen so there was a minimum of 500 m between squares and formed a gradient from the city center to the edge. Recordings were automatically identified using the software suite from ecoObs (bcAdmin (version 3.9), bcAnalyze (version 3.0) and batIdent (version 1.0)) and manually checked by an expert (K.J.) (Supplementary Information 2). Bats were identified to species level where possible or recorded in a species group (Supplementary Table 2.2). Species richness was calculated as the total number of species or species groups identified across all rounds. To be conservative, if a species group and a species from that group were identified in the same recording period, this was only considered one species. Activity was determined by calculating the total, across all rounds, number of minutes per sampling period in which a call of that species was recorded.

Bird abundance and richness

Birds were recorded visually and aurally along transects, sampled three times in spring (April to July) 2017, once in fall (October) and three times in winter (December 2017 to February 2018)52. The sampling order of the squares was randomized. In ArcGIS, we manually created transects (ranging from 1.5 m to 1,279.35 m) to cover the whole area of each square with a 25 m radius around the route58. Survey time per square was standardized to 20 min as it allowed each square to be fully surveyed but was short enough that all squares could be surveyed within 2 weeks. All species detected within a 25 m radius around the observer were recorded. Each individual’s location and movement direction was recorded to reduce double counting. Feral pigeon (Columba livia f. domestica) abundance was determined as the total of observations across all rounds. Bird abundance was determined as the total of all observations across all rounds, minus pigeons. Bird species richness was calculated as the total number of species detected per square across all rounds, minus feral pigeons (Supplementary Information 2).

Bryophyte richness

We collected mosses and liverworts between October 2017 and January 2018 on three different substrate types on all squares: wood, soil and stone (Supplementary Information 2). Species on vertical structures such as walls or trees were collected up to 2 m above ground level. We sampled each square for a maximum of 60 min (20 min for each substrate type). When moving between patches of a substrate, the timing was paused. If a substrate type was missing, it was skipped, and the sampling time was reduced by 20 min. We stopped sampling a habitat once no new species were found for several minutes. Samples were dried overnight at 50 °C before identification. Species were identified as species, species groups or morphospecies using relevant guidebooks and comparison with herbarium specimens based on macro- and microscopical characteristics (Supplementary Information 2 and Supplementary Table 2.3). Bryophyte richness was calculated as the total number of species, morphospecies or species groups identified per square. If a species group and a species contained in the group were both identified on a square, then this was only counted as one species.

Pollinator abundance and richness

Pollinators were sampled on each square three times between May and July 2018, using five annual ornamental plants as phytometers (standardized plants used to measure ecosystem traits; Supplementary Information 2). We changed the time of day a square was sampled each round so that squares were sampled once in the morning, at midday and once in the afternoon (between 08:30 and 16:30). The phytometers were placed 25 cm apart in a random order as close as possible to the center of the square, ensuring they were in an open, sunny spot. Observations began 30 min after placing the phytometers and continued for 30 min (a total of 90 min during the three sampling periods per square). Any pollinators that interacted with the reproductive parts of the phytometers were recorded. Multiple visits of the same individual to different flowers on one phytometer were counted as one visit. If a pollinator flew to another phytometer and interacted, it was counted as a new visit. Additionally, the abundance, number of racemes, spikes and umbels, and richness of flowers in a 3 m radius around the phytometers were recorded51.

Pollinators were identified in the field. If immediate identification was not possible, the insect was captured with an aspirator and stored in a jar for later identification in the laboratory. Sampled (observed or captured) pollinators were classified into functional groups representing bees (Apoidea), which were grouped into three body size classes: honeybees (Apis mellifera, containing the classical European honeybee but also other similarly sized and easily confused bees), bumblebees (Bombus sp. and individuals from the family Megachilidae) and small bees (other Apoidea) (Supplementary Table 2.4). We calculated the functional group richness and the total abundance (total number of observations per functional group) across all rounds for each square.

Pest and small mammal activity

We sampled pest and small mammals using footprint tunnels59 baited with cat food (Supplementary Information 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2.2) over 9 weeks between June and September 2017. Sampling was done on five consecutive nights (one sampling session) per square. A maximum of 12 squares, forming a transect from the city center to the edge, were sampled simultaneously each week. We placed five tunnels per square at five locations on combinations of surface type (sealed or gravel and grass) and linear structures (hedge and wall). Four tunnels (two on grass and two on sealed surface) were placed in the middle of, adjacent and parallel to the linear structures (two along walls and two along hedges) to avoid disturbances of traffic or pedestrians and encourage target species that were moving along the structures to enter the tunnel. A fifth tunnel was placed in the center of the largest grassy, open area away from linear structures (Supplementary Fig. 2.3). Where all five surface and structure types were not present on a square, we reduced the number of tunnels accordingly.

We checked the tunnels daily; bait and ink were replaced if necessary and the tracking sheets were collected and replaced. Each sheet represents 24 h of activity. After collection, the track sheets were photographed. Tracks were then identified to species level or allocated to a species group (Supplementary Table 2.5) based on the size, shape, length and width of the print and the number of toes, in addition to the arrangement of tracks60. Identified species and groups were then categorized as either ‘pest mammals’ (predominately rats (8.8%) and mice (83.4%)) or ‘small mammals’ (predominately hedgehogs (98.8%) and shrews (1%); Supplementary Table 2.5). Pest and wild mammal activity were calculated as the proportion of valid track sheets (between 7 and 50 per square) of which a pest or wild small mammal was detected.

Vegetation richness

In June and July of 2020, we recorded the spontaneous vegetation (all apparently unplanned or unplanted vegetation) diversity on eight different surfaces (frequently mown grass (<15 cm), infrequently mown grass (>15 cm), tree plates, woody structures other than trees, planting beds, planters, pavement cracks, unsealed surfaces and additional furnishings, for example, benches) of each square (Supplementary Information 2). Each surface, structure or furnishing type was observed for 15 min per square until all types of surfaces were observed. All observed plants were identified to the species. If a species was unidentifiable, we recorded it as such, and these were later removed for analysis. We combined all observations across surfaces, structures and furnishings and calculated the total species richness per square (Supplementary Information 2).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in R (version R-4.1.1)61 using R-Studio (version 2021.09.0)62.

Effects of greenness on abundance and diversity

To test the effect of greenness on each taxa’s abundance and richness, we fit linear regression models for each taxon and the proportion of green on each square. For birds and pollinators, where additional covariates were collected in conjunction with the biodiversity observations (domestic animals for birds and flower richness and abundance for pollinators), these were included and fit first in the model.

Importance of individual square features on abundance and diversity

To characterize individual square features’ effects on each taxa’s abundance and richness, we calculated variable importance scores. This was done using the random forest method from the caret package63 by growing forests with 1,001 trees for each taxon. To improve model interpretability and reduce bias in importance scores64, we removed highly colinear predictors (tree abundance, unsealed surface area, area of green and shrub area; variance inflation factor ≤5, vifstep in the package usdm65), resulting in a final list of 14 predictors (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1.1). We conducted a principal component analysis using prcomp of the final 14 predictors to illustrate the relationships of the square features (Supplementary Figs. 1.2–1.6). Final models were created using tenfold cross-validation with three repeats66 and by tuning mtry using the tuneRf function from the RandomForest package67. Variable importance was calculated using the varImp function in caret, which calculates the percentage increase in mean squared error (m.s.e.). The percentage increase in m.s.e. score for a variable is the difference between the final model m.s.e. and the m.s.e. after permuting the order of the values of that predictor. Variables with higher values of percentage increase in m.s.e. have a larger effect on the predictive performance of a model. The variable importance was then scaled, ranging from 0 to 100. Finally, the direction of the effect (positive or negative) was determined by inspection of the partial plots (Supplementary Figs. 3.1–3.14).

Community composition of squares

We conducted a nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis to further investigate the different species occurring on the squares using the metaMDS function in the vegan package68. To illustrate how the communities vary with the square features, we fit them using the envfit function of the vegan package.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The square features and biodiversity data are publicly available via Dryad at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.bcc2fqznq (ref. 69).

References

World Urbanization Prospects 2018: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/421) (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2019).

Sweet, F. S. T., Apfelbeck, B., Hanusch, M., Garland Monteagudo, C. & Weisser, W. W. Data from public and governmental databases show that a large proportion of the regional animal species pool occur in cities in Germany. J. Urban Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1093/jue/juac002 (2022).

Rega-Brodsky, C. C. et al. Urban biodiversity: state of the science and future directions. Urban Ecosyst. 25, 1083–1096 (2022).

Theodorou, P. et al. Urban areas as hotspots for bees and pollination but not a panacea for all insects. Nat. Commun. 11, 576 (2020).

Uhler, J. et al. Relationship of insect biomass and richness with land use along a climate gradient. Nat. Commun. 12, 5946 (2021).

Ives, C. D. et al. Cities are hotspots for threatened species. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 25, 117–126 (2016).

McKinney, M. L. Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation. Bioscience 52, 883–890 (2002).

Cities and Biodiversity Outlook (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2012).

Marselle, M. R., Lindley, S. J., Cook, P. A. & Bonn, A. Biodiversity and health in the urban environment. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 8, 146–156 (2021).

Peccia, J. & Kwan, S. E. Buildings, beneficial microbes, and health. Trends Microbiol. 24, 595–597 (2016).

Elmqvist, T. et al. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2, 267–273 (2019).

Mata, L. et al. Bringing nature back into cities. People Nat. 2, 350–368 (2020).

Grabowski, Z. et al. Cosmopolitan conservation: the multi-scalar contributions of urban green infrastructure to biodiversity protection. Biodivers. Conserv. 32, 3595–3606 (2023).

Fournier, B., Frey, D. & Moretti, M. The origin of urban communities: from the regional species pool to community assemblages in city. J. Biogeogr. 47, 615–629 (2020).

Bornkamm, R., Lee, J. A. & Seaward, M. R. D. (eds) Urban Ecology: 2nd European Ecological Symposium (Blackwell Scientific, 1982).

Wittig, R Ökologie Der Großstadtflora. Flora Und Vegetation Der Städte Des Nord‐westlichen Mitteleuropas.(Gustav Fischer Verlag: 1991).

Evans, K. L., Chamberlain, D. E., Hatchwell, B. J., Gregory, R. D. & Gaston, K. J. What makes an urban bird? Glob. Change Biol. 17, 32–44 (2011).

Knapp, S. et al. Urbanization causes shifts in species’ trait state frequencies. Preslia 80, 375–388 (2008).

Hahs, A. K. et al. Urbanisation generates multiple trait syndromes for terrestrial animal taxa worldwide. Nat. Commun. 14, 4751 (2023).

Sol, D., Bartomeus, I., Gonzalez-Lagos, C. & Pavoine, S. Urbanisation and the loss of phylogenetic diversity in birds. Ecol. Lett. 20, 721–729 (2017).

Nilon, C. H., Warren, P. S. & Wolf, J. Baltimore birdscape study: identifying habitat and land-cover variables for an urban bird-monitoring project. Urban Habitats 6, 1 (2011).

Beninde, J., Veith, M. & Hochkirch, A. Biodiversity in cities needs space: a meta-analysis of factors determining intra-urban biodiversity variation. Ecol. Lett. 18, 581–592 (2015).

Melliger, R. L., Rusterholz, H.-P. & Baur, B. Habitat- and matrix-related differences in species diversity and trait richness of vascular plants, Orthoptera and Lepidoptera in an urban landscape. Urban Ecosyst. 20, 1095–1107 (2017).

Brunbjerg, A. K. et al. Can patterns of urban biodiversity be predicted using simple measures of green infrastructure? Urban For. Urban Green 32, 143–153 (2018).

Rega-Brodsky, C., Nilon, C. & Warren, P. Balancing urban biodiversity needs and resident preferences for vacant lot management. Sustainability 10, 1–21 (2018).

Snep, R. P. H. Biodiversity Conservation at Business Sites: Options and Opportunities. PhD thesis, Wageningen Univ. (2009).

Wilkinson, C., Sendstad, M., Parnell, S., Schewenius, M. et al. in Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities: A Global Assessment (eds Elmqvist, T. et al.) 539–587 (Springer, 2013).

Aminde, H.-J. Plätze in Der Stadt (Hatje, 1994).

Memluk, M. in Advances in Landscape Architecture (ed Ozyavuz, M.) (InTech, 2013).

Haase, D. et al. A quantitative review of urban ecosystem service assessments: concepts, models, and implementation. Biodivers. Conserv. 43, 413–433 (2014).

Methorst, J. et al. The importance of species diversity for human well-being in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 181, 106917 (2021).

Hatty, M. A., Mavondo, F. T., Goodwin, D. & Smith, L. D. G. Nurturing connection with nature: the role of spending time in different types of nature. Ecosyst. People 18, 630–642 (2022).

Hof, A. R. & Bright, P. W. The value of green-spaces in built-up areas for western hedgehogs. Lutra 52, 69–82 (2009).

Russo, D. & Ancillotto, L. Sensitivity of bats to urbanization: a review. Mamm. Biol. 80, 205–212 (2015).

Lindenmayer, D. B. & Laurance, W. F. The ecology, distribution, conservation and management of large old trees. Biol. Rev 92, 1434–1458 (2017).

Le Roux, D. S., Ikin, K., Lindenmayer, D. B., Manning, A. D. & Gibbons, P. The future of large old trees in urban landscapes. PLoS ONE 9, e99403 (2014).

Lindenmayer, D. B. et al. New policies for old trees: averting a global crisis in a keystone ecological structure. Conserv. Lett. 7, 61–69 (2014).

Threlfall, C. G., Williams, N. S. G., Hahs, A. K. & Livesley, S. J. Approaches to urban vegetation management and the impacts on urban bird and bat assemblages. Landsc. Urban Plan. 153, 28–39 (2016).

Connor, E. & McCoy, E. In Reference Module in Life Sciences (ed. Roitberg, B. D.) (Elsevier, 2017).

Żołnierz, L., Fudali, E. & Szymanowski, M. Epiphytic bryophytes in an urban landscape: which factors determine their distribution, species richness, and diversity? A case study in Wroclaw, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 6274 (2022).

Richter, S., Schuütze, P. & Bruelheide, H. Modelling epiphytic bryophyte vegetation in an urban landscape. J. Bryol. 31, 159–168 (2009).

Gerdol, R., Marchesini, R., Iacumin, P. & Brancaleoni, L. Monitoring temporal trends of air pollution in an urban area using mosses and lichens as biomonitors. Chemosphere 108, 388–395 (2014).

Buzan, E. Changes in rodent communities as consequence of urbanization and inappropriate waste management. Appl. Ecol. Env. Res. 15, 573–588 (2017).

Mathews, F. et al. Barriers and benefits: implications of artificial night-lighting for the distribution of common bats in Britain and Ireland. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20140124 (2015).

Finch, D. et al. Effects of artificial light at night (ALAN) on European hedgehog activity at supplementary feeding stations. Animals 10, 768 (2020).

Koen, E. L., Minnaar, C., Roever, C. L. & Boyles, J. G. Emerging threat of the 21st century lightscape to global biodiversity. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 2315–2324 (2018).

Fernández-Juricic, E. & Tellería, J. L. Effects of human disturbance on spatial and temporal feeding patterns of blackbird Turdus merula in urban parks in Madrid, Spain. Bird Study 47, 13–21 (2000).

Bateman, P. W. & Fleming, P. A. Does human pedestrian behaviour influence risk assessment in a successful mammal urban adapter? J. Zool. 294, 93–98 (2014).

Mimet, A., Kerbiriou, C., Simon, L., Julien, J.-F. & Raymond, R. Contribution of private gardens to habitat availability, connectivity and conservation of the common pipistrelle in Paris. Landsc. Urban Plan. 193, 103671 (2020).

Falcón, J. et al. Exposure to artificial light at night and the consequences for flora, fauna, and ecosystems. Front. Neurosci. 14, 602796 (2020).

Berthon, K. et al. Small-scale habitat conditions are more important than site context for influencing pollinator visitation. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 703311 (2021).

Mühlbauer, M., Weisser, W. W., Müller, N. & Meyer, S. T. A green design of city squares increases abundance and diversity of birds. Basic Appl. Ecol. 56, 446–459 (2021).

Allan, E. et al. Interannual variation in land-use intensity enhances grassland multidiversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 308–313 (2014).

Kyrö, K. et al. Vegetated roofs in boreal climate support mobile open habitat arthropods, with differentiation between meadow and succulent roofs. Urban Ecosyst. 23, 1239–1252 (2020).

Stewart, A. J. A. & Wright, A. F. A new inexpensive suction apparatus for sampling arthropods in grassland. Ecol. Entomol. 20, 98–102 (1995).

Seibold, S. et al. Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature 574, 671–674 (2019).

Leidinger, J. et al. Formerly managed forest reserves complement integrative management for biodiversity conservation in temperate European forests. Biol. Conserv. 242, 108437 (2020).

Chamberlain, D., Kibuule, M., Skeen, R. Q. & Pomeroy, D. Urban bird trends in a rapidly growing tropical city. Ostrich 89, 275–280 (2018).

National Hedgehog Survey Volunteer Handbook. 28 (2014); https://www.igelzentrum.ch/images/Doc/National-hedgehog-survey-volunteer-handbook.pdf

Marchesi, P., Blant, M. & Capt, S. Fauna Helvetica - Säugetiere Bestimmung (CSCF and SGW, 2008).

R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Core Team https://www.R-project.org/ (2021).

RStudio: integrated development environment for R. R Studio Team http://www.rstudio.com/ (2021).

Kuhn, M. Caret: classification and regression training. R Core Team https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=caret (2021).

Strobl, C., Boulesteix, A.-L., Kneib, T., Augustin, T. & Zeileis, A. Conditional variable importance for random forests. BMC Bioinform. 9, 307 (2008).

Naimi, B., Hamm, N. A. S., Groen, T. A., Skidmore, A. K. & Toxopeus, A. G. Where is positional uncertainty a problem for species distribution modelling. Ecography 37, 191–203 (2014).

Fox, E. W. et al. Assessing the accuracy and stability of variable selection methods for random forest modeling in ecology. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189, 316 (2017).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2, 18–22 (2002).

Oksanen, J. et al. Vegan: community ecology package. R Core Team https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2020).

Data from: biodiversity and local features of 103 public urban squares in Munich, Germany. Dryad https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.bcc2fqznq (2024).

Acknowledgements

Parts of this research were funded by the Technical University of Munich. Parts of this work were also funded by the Research Training Group 2679—Urban Green Infrastructure (German Research Foundation GRK2679, W.W.W.). This work was further supported by the TUM International Graduate School of Science and Engineering (IGSSE, PROTOHAB P2104, W.W.W.). We thank the City of Munich for their cooperation and for making the work on urban squares possible. Additionally, we thank M. Erhardt for assisting with the bat identification and A. Haberer for providing the photos of the squares. We also thank H. Schäfer, S. Barath and our colleagues at the Technical University of Munich for their critical comments on the manuscript. We thank all the project students and student helpers who assisted with the data collection. Finally, we thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for commenting on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Technische Universität München.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally: A.J.F. and S.T.M. S.T.M., M.M., W.W.W. and A.J.F. developed the research goal and aims. Field data were collected and processed by B.A., K.J., M.M., K.B., A.F., L.G., J.J., K.K., N.M., C.O., M.U., J.W., J.M., P.D. and S.T.M. A.J.F. and S.T.M. analyzed the data. The manuscript was written by A.J.F., S.T.M. and W.W.W., with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cities thanks Michael McKinney, Nicholas Williams, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Location of public squares in Munich and their greenness.

The circles represent the location of 103 public squares in the city of Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Colour represents the percentage of green cover on each square based on the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index with a threshold of 0.2. Percent greenness is continuous and binned for display purposes. Map tiles by Stamen Design, under a Creative Commons license CC BY 3.0. Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors under a CC BY-SA 2.0.

Extended Data Fig. 2 NMDS biplot indicating the community composition of public urban squares in Munich.

Each circle represents one of the 103 public squares in the city of Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Colour represents the percent of green cover on each square based on the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index with a threshold of 0.2. Percent greenness is continuous and binned for display purposes. Shown vectors are the square features with significant relationship to the ordination (p <= 0.5). Inset shows how very grey squares have very different communities to greener squares.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information 1–4 containing extended methods and additional analyses, including 24 figures and 7 tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fairbairn, A.J., Meyer, S.T., Mühlbauer, M. et al. Urban biodiversity is affected by human-designed features of public squares. Nat Cities 1, 706–715 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-024-00126-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-024-00126-5

This article is cited by

-

Biodiversity in the city: effects of local and landscape characteristics on ant community in urban squares of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Urban Ecosystems (2026)

-

Promoting urban biodiversity for the benefit of people and nature

Nature Reviews Biodiversity (2025)

-

Urban bird diversity and ecosystem services are shaped by fine-scale habitat features

npj Urban Sustainability (2025)

-

Countries need ambitious urban biodiversity targets under the EU Nature Restoration Law

npj Urban Sustainability (2025)

-

NDVI and vegetation volume as predictors of urban bird diversity

Scientific Reports (2025)