Abstract

Urban parks are important for public health, but the role of specific spaces, such as playgrounds or lakes, and elements, such as benches or sports equipment, in supporting well-being is not well understood. Here, based on expert input and a review of the literature, we defined six types of health-related activity: physical, mindfulness, nature appreciation, environmental, social and cultural. We built a lexicon that links each activity to specific elements and spaces within parks present in OpenStreetMap. Using these data, we scored 23,477 parks across 35 cities worldwide on the basis of their ability to support these activities. We found clear patterns: parks in North America focus more on physical activity, while those in Europe offer more chances to enjoy nature. Parks near city centers support health-promoting activities better than those farther out. Suburban parks in many cities lack the spaces and equipment needed for nature-based, social and cultural activities. We also found large gaps in park quality between cities. Tokyo and Paris provide more equal access, while Copenhagen and Rio de Janeiro show sharp contrasts. These results can help cities create fairer parks that better support public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

As the world’s population continues to gravitate toward urban areas, cities are faced with the immense task of creating and maintaining green spaces to foster public health1,2. Urban parks are especially beneficial to vulnerable population groups such as socioeconomically deprived3 and older people4,5. Yet, the provision of amenities and facilities that support health-promoting activities has not been systematically analyzed at scale.

Urban green spaces can support health in five main ways. First, they help people stay active, which can reduce obesity and heart diseases6,7. Second, they give people a calm space to rest, reduce stress and improve focus6,8,9,10. Third, they bring people together and support social ties11. Fourth, they clean the air, block noise and cool the city6,12. Last, some green areas expose people to biodiverse forms of life, which may improve the immune system13,14.

Park planners have often focused on practical ways to boost public health, such as adding sports fields, paths or playgrounds15,16,17,18. Despite groving evidence of positive effects, spaces that allowed a diverse range of people to relax or enjoy beauty were often neglected in the past19. Parks also have the power to build stronger communities20, and many planners now recognize that parks offer clear environmental gains such as cleaner air and lower noise levels12. During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, cities saw how vital parks are for public well-being. This led to stronger calls for fair and flexible park design21.

Most past studies have treated parks as simple green zones, based on size or distance from homes22,23. Fewer have studied how the park layout and equipment affect how people use them. For instance, SOPARC is a tool that tracks how people move through parks and what spaces they use24. Other tools look at what makes parks good for activity, such as access, safety or looks25. Still others focus on blue spaces such as rivers or lakes26. These tools work well but are time-consuming to implement and hard to scale, and most focus only on physical activity27,28. We still lack a clear understanding of the net benefits of parks, especially when weighing their positive aspects, such as providing spaces for recreation and supporting urban health3,29, with potential downsides, including reinforcing disparities30,31,32 or contributing to gentrification33,34.

For many cities, there is no easy way to list what parks contain or link these parts to health uses. In this study, we score parks in 35 cities on the basis of how well they support six types of health-related activity. The project page is available at https://social-dynamics.net/healthy-parks. We then ask how these scores relate to fair access to well equipped parks. Our work answers three questions. First, which health-related activities do different park spaces support? Second, how can we measure parks around the world based on this support? Third, where are the biggest gaps in what parks provide?

Results

We began by creating a lexicon that linked park spaces and elements to health-related activities using OpenStreetMap (OSM) data. We then scored parks in 35 major cities, which we selected for their geographic diversity and reliable OSM coverage. After validating these scores through statistical comparison and expert review, we analyzed differences in park offerings within and between cities.

Lexicon of health-related park features

Defining activities in parks (step 1)

An expert panel of three researchers with expertise in urban computing, Earth observation and computational social science, identified common park activities and organized them into six categories:

-

Physical activities: movement and sport such as walking, biking, swimming and group exercise;

-

Mindfulness activities: practices such as yoga, meditation and tai chi;

-

Nature appreciation: observing and enjoying the natural environment, including bird watching and picnicking;

-

Environmental activities: community involvement such as gardening and conservation;

-

Social activities: gatherings and group events such as festivals and volunteering;

-

Cultural activities: heritage and arts programs, including performances and exhibitions.

While our six categories occasionally overlapped, they captured park activities at a more useful granular level than the typical recreational and physical division. Some overlap is inevitable because certain activities such as football (with social and physical aspects) are inherently multifaceted.

Linking facilities to activities (step 2)

We used OSM to collect elements and spaces located within parks in the 35 cities. These included defined areas such as forests and ponds as well as features such as benches and sports courts. Each item was described with a tag, which we used to assign the item to an activity category. To scale this process, we trained a classifier based on a large language model (LLM) and validated it with an expert-coded dataset. The full lexicon included 1,441 OSM tags. The ten most frequent tags for each category are listed in Extended Data Table 1. No OSM tags matched the mindfulness category, so we did not include it in our scoring. Future research may incorporate behavioral data to address this gap.

Scoring parks for health support

We scored each park based on the number of activity-related elements and spaces it contained, normalized by park area. Each park received a score for every activity category. Figure 1 presents an example of these scores for London. In total, we scored 23,477 parks across 35 cities on 5 continents (Table 1). Each score reflects how well a park supports a specific activity compared with other parks of similar size in the same city. Figure 2 visualizes the methodology to estimate the ‘average park line’.

a,b, Scores for nature appreciation (a) and physical activities (b) in London parks. Some parks score low on nature appreciation but high on physical activity (A), whereas imperial-era parks, such as Green Park and St. James’s Park near the royal palace, score high on nature appreciation but low on physical activity (B). Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, purpose-built for the 2012 Games, scores high across all dimensions (C). A visualization for all cities can be viewed at https://social-dynamics.net/healthy-parks. Map data from OpenStreetMap under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL).

a,b, The linear regression models for determining the park health scores for the park elements (a) and park spaces (b) in London, UK. The horizontal axis denotes the park’s area (log2), while the vertical axis represents the count of park elements (log2) and the area occupied by health-promoting park spaces (log2). The modest R2 values are anticipated, highlighting the variety among parks.

Validation with Flickr data

We validated our park scores using geotagged Flickr images taken within park boundaries. These images included both user-generated and machine-generated tags. We used sentence embeddings to match these tags to our activity taxonomy, allowing us to estimate activity scores for each park based on photo content.

We compared these Flickr-based activity scores with our OSM-derived scores using the Pearson correlation coefficent (PCC). Across the 35 cities, the average correlation was 0.39 with a standard deviation of 0.07, indicating moderate but consistent agreement between the two sources. The highest mean (μ) agreement appeared in the cultural (μ = 0.53), social (μ = 0.39) and environmental (μ = 0.39) categories. These types of activity often involve distinctive and photogenic features such as festivals, artworks or gardens, which are likely to be photographed and tagged.

By contrast, the physical (μ = 0.30) and nature appreciation (μ = 0.33) categories showed weaker correlations. We believe this may be because users often photograph people or scenery without tagging specific sports or nature-related elements, making it harder to detect those activities in the data.

At the city level, Washington, DC (μ = 0.52) and Perth (μ = 0.50) had the strongest correlations. These cities are in English-speaking countries where Flickr and OSM usage is more common, which probably led to higher data quality and tag relevance. Cities with lower correlations, including Amsterdam, Hong Kong and Vienna (each μ ≈ 0.3), may have had fewer geotagged images, lower tag accuracy or less alignment with our English-based taxonomy.

These findings support the use of OSM data to assess park infrastructure for health-promoting activities, especially in categories and regions where online content about park use is widely available.

Validation with Wikipedia

We also validated our activity scores using Wikipedia pages. We identified the top-scoring parks globally for each health-related activity based on our scoring system. For each park, we examined the Wikipedia page to confirm whether the park was known for the corresponding activity type.

In the physical category, we found that parks such as Centennial Parklands in Australia and Bois de Boulogne in Paris were known for extensive sports infrastructure, including fields for tennis, soccer and polo. For nature appreciation, top parks such as La Dehesa de la Villa in Madrid and Guandu Nature Park in Taipei stood out in their cities with large green areas and wildlife. In the environmental category, Washington Park Arboretum in Seattle and Kita-no-maru Park in Tokyo included botanical gardens and conservation efforts. Social activity leaders such as Inspiration Lake in Hong Kong and Toronto Island Park in Canada were cited for hosting gatherings and public amenities. In the cultural category, Ueno Park in Tokyo featured museums and historic landmarks, while Seattle Center included concert halls and art venues.

To further verify our assignments, we conducted structured search queries, such as ‘Tokyo parks for cultural activities’ and found that the top-ranked parks by our method consistently appeared in online recommendations and guides. A complete list of these parks, organized by city and activity category, is available in Extended Data Table 2.

Cities differ in health-related activity support

Our analysis revealed systematic variations in how urban parks support health-promoting activities, with differences occurring both between cities and within individual urban areas. These variations reflect distinct urban planning priorities, geographic influences and equity considerations that shape park design and resource allocation.

Estimating park offerings through 8-hectare model parks

To compare park features systematically across cities, we constructed statistical models of typical 8-hectare parks: a size representing neighborhood parks and matching our dataset’s average. Figure 3 (top) shows the expected number of elements and area dedicated to each activity type in a statistically average 8-hectare park for each city. We computed these values using parameters from linear regression models developed for each city (equation (1)). While we fit separate models per city, making raw health scores not directly comparable between cities, the models enabled comparison of hypothetical average parks across urban contexts.

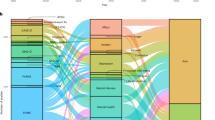

a, Area of park spaces (horizontal axis) and count of elements (vertical axis) in a typical 8-hectare park by activity and city. Nature and physical activity spaces are the most frequent. Nature-related elements are also the most common across cities. Cultural spaces and elements appear least often. Axes are scaled for clarity. b, Average space in 8-hectare parks dedicated to nature and physical activities in North America (n = 24) and Europe (n = 22). North American parks support physical activity more, while European parks provide more space for nature appreciation. Standard box plot with Q1, median, Q3; whiskers at 1.5× interquartile range.

European nature focus versus North American physical activity in regional priorities

The most notable regional contrast lies in emphasis on physical activity versus nature appreciation, as shown in Fig. 3 (bottom). Parks in European cities tended to provide more space for nature appreciation, while North American cities allocated more area to physical activities. These differences reflect broader urban planning patterns and suggest that parks serve different roles depending on regional goals and cultural expectations.

Universally limited support for cultural features

Across all regions, cultural features appeared least frequently in parks. In terms of elements, nature appreciation appeared most often, followed by social and environmental activities. Cultural features were the least common. This pattern suggests that, while nature and movement receive widespread support, cultural health-promoting activities are deprioritized globally in urban park design.

Park offerings are unequally distributed within cities

We examined how park scores vary within cities by grouping parks into quartiles based on distance from city centers, from the innermost 25% (Q1) to the outermost 25% (Q4). This approach allowed us to systematically assess whether proximity to urban centers influences park offerings. Extended Data Fig. 1 visualizes the negative correlations between between park health scores and the distance to the city centers.

Inner-city parks consistently outperform peripheral ones

Across all activity types, parks in central areas scored higher. Figure 4a demonstrates that park scores dropped steadily with each quartile further from the center. This pattern held across most cities on all continents, with exceptions in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro, where geography and coastal form influence green space layout.

a, Park health scores by quartiles of the distance to the city center. Q1 includes parks closest to the city center; Q4 includes those farthest away. Scores decline steadily with distance, especially for nature appreciation. Environmental features show the least decline. Standard box plot with Q1, median, Q3; whiskers at 1.5× interquartile range. n = 5,869 parks per quartile. b,c, Inequality in park health scores activity category (b, n = 35 cities) and continent (c, n = cities per continent; Table 1). While total disparity ranges are similar across regions, some activities, such as social and cultural, show much higher inequality than others. White × indicates mean value. Standard box plot with Q1, median, Q3; whiskers at 1.5× interquartile range.

Nature appreciation shows strongest distance-related decline

The trend was most pronounced for nature appreciation. This finding challenges assumptions that outer areas naturally support greener, more restorative environments and echo Montgomery’s concept of the ‘Savannah Trap’35, where suburban areas include empty, open land that does not support social or ecological use.

We systematially verified that the trends in Fig. 4a are statistically significant, as shown in Extended Data Table 3.

Cities vary in ensuring equitable park access

We assessed equity in park offerings within cities using a disparity index (equation (3)) ranging from 0 (complete equality) to 1 (maximum inequality). Box plots in Fig. 4b,c show average disparities by activity and region, with detailed values in Table 2. Extended Data Fig. 2 visualizes the disparitiy scores subdivided by city.

Activity-specific disparity patterns

Disparities varied by activity type: physical activities showed the most even distribution (μ = 0.135; σ = 0.039), while social activities exhibited the highest disparity (μ = 0.222, σ = 0.073), indicating that some parks offer rich social features while others lack them entirely. Nature appreciation had moderate average disparity (μ = 0.157) but low variation (σ = 0.032), suggesting consistent global trends. Overall disparities averaged 0.165, and were similar across continents (0.15–0.19), suggesting that inequality in park design is not limited to one region.

Cities achieving balanced activity support

Tokyo, Paris, Auckland, Buenos Aires and Hong Kong demonstrated the most equitable park offerings across activities. Tokyo and Paris particularly excelled, with four or more activity categories showing disparities below one standard deviation from the mean. These results may reflect centralized park governance, strong public policy and active community involvement in cities such as Paris36 and Tokyo37.

Cities with concentrated park resources

By contrast, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Stockholm, Rio de Janeiro and Copenhagen showed high disparities in park offerings across categories. Stockholm exhibited the highest single-category disparity in cultural features (0.514), suggesting cultural resources were concentrated in a few parks. Copenhagen showed high disparity in both cultural and social categories, potentially reflecting gentrification38. Rio de Janeiro displayed widespread disparities across social, environmental and cultural categories, aligning with prior findings on spatial health inequality39.

These findings demonstrate that, while park inequality exists globally, specific cities have successfully implemented more equitable approaches to supporting diverse health-promoting activities through their urban park systems.

Discussion

Urban parks offer health benefits that go beyond the usual physical and mental well-being. However, our global analysis reveals that urban parks require strategic improvement focused on geographic equity and activity diversity to maximize their health benefits.

Main findings

By identifying six types of activity people do in parks, we created a detailed taxonomy of park activities and used this to evaluate parks worldwide based on their support for five of the six activity categories (data to evaluate the mindfulness category were not available on OSM). By giving individual scores for each activity, we identified three critical areas that demand attention from landscape architects, urban designers and policymakers.

Geographic inequities demand immediate action

Our findings show a clear and concerning geographic trend: parks in city centers are better equipped for health-promoting activities than those on the outskirts. This pattern holds across all types of activity, including those that might be expected to be more common in less populated areas, such as nature appreciation or environmental activities. This geographic disparity contradicts basic expectations and creates notable barriers to equitable health access.

This finding aligns with previous research. Wolch et al. found that park distribution often favors more wealthy communities31. Other studies have shown that recent urban development policies have led to substantial greening in city centers, while suburban areas have received less investment40. Our results expand on these works by showing not only reduced access to parks in suburban areas31,40, but also a lack of amenities and spaces for health-promoting activities.

This evidence creates a clear call to action for urban planners to shift their focus to improving suburban parks, as well as parks outside urban centers, where notable and often overlooked recreation gaps are often found41. However, creating high-quality urban green spaces can be a balancing act, with potential downsides such as gentrification31,34. Designers must think carefully about the urban context when improving parks in ways that may change their role34.

Activity-type inequities show mixed but encouraging patterns

We also examined disparities in the health potential of parks among cities by activity type. The findings are generally encouraging: overall disparity scores were low and did not show pronounced global variation, in contrast to earlier studies42,43. While previous work has shown high inequality in absolute access to greenery, our results suggest that relative inequality in access to health-promoting park activities is less severe.

The distribution patterns vary considerably by activity type, revealing both strengths and critical gaps. Physical activity infrastructure was the most evenly distributed, probably reflecting its prominence in public health discourse and urban policy18. This aligns with the medical literature’s emphasis on physical activity benefits. By contrast, facilities for social activities were the most unequally distributed, revealing a key area for improvement44.

The global nature of this challenge is evident from our data: the five cities with the greatest disparities in park offerings span four continents, indicating that uneven provision of well-equipped parks is not a concentrated issue. This suggests that urban planning is not only a matter of financial resources but also of municipal priorities and community engagement36,45. A positive trend can be observed in the Asian countries of our study and Oceania, which have the most fair provision of park facilities.

Our findings provide actionable insights for the design of well-equipped parks

To understand the relevance of our work for urban planning, we conducted 30-min semi-structured interviews with three domain experts. We reached out to practitioners with 12–30 years of professional experience from diverse backgrounds: a lecturer and urban designer (E1, male), an urban designer and master planner (E2, female) and a municipal park development manager (E3, male). The experts confirmed that our quantitative approach offers significant practical value for urban design decisions. They identified several ways our findings could support urban design: reducing reliance on subjective park assessments (E1), serving as a quantitative baseline for master planning (E1 and E2) and providing an evidence-based alternative to institutional knowledge and practice-specific heuristics (E1). The urban designers emphasized that the visualization of park scores is already useful to "identify the gaps regarding what is present in terms of offerings in a district (E1)”, especially when aiming to ensure fair access to parks. This was echoed by the park manager, who stated they would use the park scoring to guide development priorities, and as supporting evidence to gain leadership backing or external funding. When shown the taxonomy of activities, they noted that most of their projects addressed physical and nature-appreciation activities, and "[the activity taxonomy] helps us think about what it is we’re doing and how and how some categories have been neglected (E3)”.

The experts also highlighted the importance of the way our scores are normalized to the specific context of each city. Our park scores are normalized to reflect the unique context of each city, making direct comparisons between cities hard. While this limits intercity comparisons, it avoids drawing misleading conclusions across culturally, geographically, and climatically diverse settings. For example, E1 cited culturally different approaches to park provision in the form of ‘three-dimensional parks’ in high-density environments such as Hong Kong, while E2 brought up the challenges in adopting urban transformation manuals from Western cities in regions with extreme climates such as the Middle East.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the well-known benefits of parks, lack of fair access to urban green spaces remains a common theme in academic literature2,31,40,42,46. We focused only on urban parks, excluding other types of urban green space such as gardens, street trees and green roofs, which also contribute to urban health. Parks were selected because they support a wider range of activities than more specialized spaces, are generally publicly accessible and are typically maintained by municipal administrations, making any identified shortcomings more actionable for policy and planning.

Relying on map data limits our analysis to activities that can be linked to specific elements and spaces within parks. While some studies explored the relationship between open spaces and their use47, we avoided making assumptions about the usage of informal spaces to reduce the risk of cultural bias in our park evaluations. As a result, we excluded mindfulness activities from our main analysis, as they often do not require designated areas in city parks. Likewise, our data do not account for temporary cultural events, such as music festivals held in parks.

Park offerings were scored under the assumption that the presence of facilities and spaces enabling certain activities is a necessary condition for realizing specific health benefits. However, their presence alone may not be enough to deliver these benefits in practice. Furthermore, not all activities are directly tied to specific infrastructure, and OSM cartographic data alone cannot capture the intensity of use. We did not distinguish between the quality of maintenance or design of individual elements, such as benches being equipped with backrests, or the size, layout and species of trees and other plants.

Like all urban spaces, parks are in constant flux, which raises the question of how parks have evolved over time2. This became clear during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many cities had to rethink their strategies, possibly leading to big changes in park facilities with major social justice effects48. Looking at historical data from OSM is challenging, as it is difficult to distinguish between actual changes in park facilities and the increasing completeness of the OSM database.

A key direction for future research is to examine how park offerings directly influence health outcomes. While collecting global medical data to evaluate the health impact of individual parks is impractical, more targeted investigations may be feasible in specific contexts. For instance, prescription data available in some countries could be used to estimate the prevalence of certain medical conditions49, and to explore potential causal links between changes in park infrastructure and improvements in public health over time.

We showed that the OSM park scores are closely linked to activities captured in Flickr photos, but other data could also be used to approximate park usage. For instance, detailed mobile traffic data could offer interesting insights into how parks are used30,50,51. This could also help to reduce biases inherent in social media data sources such as Flickr and OSM, which rely on actively submitted contributions from tech-savvy users, and sometimes out-of-city visitors rather than passive observations of citizen behavior.

Finally, by focusing on health-promoting activities, our work introduces avenues for health-related behavioral change20,52. For instance, our activity-based approach could support context-aware recommendations53, such as identifying the most suitable times to engage in specific park activities when conditions such as temperature, air quality or crowdedness are most favorable.

Methods

Data

OSM is a globally encompassing geographic information database based on crowdsourced contributions. While accessible through a map interface at https://openstreetmap.org, its primary value lies in being an indispensable source for open mapping data in both commercial and scientific applications54,55,56. Thanks to its permissive licensing, OSM has fostered a large ecosystem of individual and professional contributors. As a result, the project has achieved comprehensive worldwide coverage, with near-perfect mapping quality across the Western world56, while retaining remarkable detail in the global south55. In this study, we utilized OSM data from fall 2023.

OSM uses a tagging system with key–value pairs to categorize and describe all these map objects. Each map object is typically associated with multiple tags that describe its purpose, but may also include additional information, such as opening hours, or data source references. To avoid the complexities of the OSM data model, for our tasks, it was sufficient to focus on two key map objects related to parks: park elements and park spaces. Park elements are zero-dimensional points representing objects such as benches, individual trees and statues. Park spaces refer to areas within the parks, such as meadows, lakes and forests.

Flickr (https://flickr.com) has established itself as one of the most prominent platforms for sharing photography. Since its inception in 2004, the platform has gained considerable popularity, accumulating billions of images. Notably, many of these images have been precisely geolocated, thanks to the utilization of the (phone) camera’s GPS module.

We utilized a substantial dataset comprising geolocated images posted between 2004 and 2015. This extensive dataset offered us a valuable secondary perspective on activities taking place within the parks of the world. By intersecting these images with the park outlines from OSM, we identified 10,788,686 pictures captured within the boundaries of parks in our study cities. To extract the depicted content from these images, we used user-assigned tags in conjunction with automatically generated computer vision labels57,58.

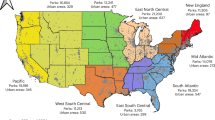

Study area

Our research focused on 35 cities listed in Table 1, which we selected using three criteria to make our analysis broad yet robust.

First, we selected major cities worldwide with populations of at least 650,000. This threshold includes many of the largest urban areas, such as major European capitals and other densely populated regions where parks play a vital role in public well-being. To improve representation in Oceania, however, we made an exception for Christchurch, New Zealand, which has a smaller population. This first criterion allowed us to examine parks in cities from various parts of the world, each affected by its own climate, history and cultural background.

Second, we only considered cities in countries where at least 80% of the population has Internet access59. This ensured we had enough online data (such as tags on OSM or photos on Flickr) for our study. As there are no detailed global data on Internet use in cities specifically, we used the country’s overall access to the Internet as our guide. We decided on this threshold upon our preliminary analyses, finding that, in many cities in Africa and South America, there was not enough digital information for our approach, which relies on social media and collaborative mapping data.

Third, we selected cities where, on average, at least one-eighth of park areas are annotated with health-related tags on OSM. As our analysis relied heavily on OSM data, this criterion ensured a minimum level of information on the platform for our study. We settled on this one-eighth threshold after observing that, below this level, the lack of contributor-added tags limited our ability to extract meaningful information. This primarily excluded cities where most tagging was done predominantly automatically through Earth observation that was not accompanied by manual tagging of OSM contributors. This was mainly the case in China, where nongovernmental mapping is restricted60.

Identifying health-promoting activities in urban greenery

We identified and categorized park-based activities using input from an expert panel consisting of three co-authors of this study. We compiled a comprehensive list of activities commonly undertaken in urban parks. To collect relevant papers, we used two specific queries of Google Scholar: ‘(urban) AND (parks OR greenery) AND usage’ and ‘(activities in urban) AND (parks OR greenery)’. From this process, we retrieved the top 50 scholarly articles for each search phrase, resulting in a total of 91 unique papers. We reviewed each article and collected all activities, resulting in a diverse set of activity descriptions varying in granularity. For example, the literature included both broad terms such as ‘leisure activities’ or ‘recreation’, as well as more specific categories such as ‘physical’ and ‘social’ activities. We also noted plenty of individual activities such as ‘walking’, ‘performing street theater’, ‘fishing’ and ‘playing all kinds of different sports’. Subsequently, we convened to categorize the identified activities, with a particular focus on their potentially different impact on health and on ensuring a consistent level of specificity across categories. Broad terms such as recreation were deemed too general to be analytically useful, whereas distinctions like physical versus social activities were considered meaningful. This process ultimately yielded six distinct categories: physical, mindfulness, nature appreciation, environmental, social and cultural activities.

Annotating park OSM tags with activities using LLM classifiers

To associate different park elements and spaces with health-promoting activities, we annotated OSM tags describing those elements and spaces with activities. This turned out to be a challenging task. OSM is a collaborative platform with some governance and guidelines (https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Map_features) for tagging, but the flexible tagging system offers the crowdsourcing contributors substantial freedom. As a result, the data can be inconsistent and fragmented, necessitating thorough cleaning. Each map object, such as park elements and spaces, can be tagged with an unlimited number of tags, offering in-depth descriptions. As a result, we encountered over 30,000 unique key–value pairs associated with park elements and spaces. As our primary focus is on the core functional aspects of these elements, we conducted a data cleaning step (detailed in the Supplementary Information) to remove irrelevant metadata associated with the map objects. This filtering allowed us to focus exclusively on tags relevant to activity-related features, thereby making the annotation process more pertinent to our study.

Using LLMs for annotation

Even for domain experts, linking these tags unequivocally to health-related activities was difficult. For instance, a bench might relate to socializing, enjoying nature or resting after physical activity. Choosing one activity over another often depended on personal experience, as many tags could plausibly refer to multiple activities. Given the large number of items and the specialized nature of the task, we chose an LLM classifier as an alternative to expert annotation or crowdsourcing.

Using LLMs as classifiers offers several advantages as they provide a more objective and consistent approach to annotation, can handle large volumes of data quickly and do so at relatively low cost. In some cases, LLM classifiers have even outperformed crowdworkers61, who may themselves rely on machine learning tools to complete tasks62. Research also suggests that LLM-based annotations can match the quality of those made by domain experts63. Given these benefits, we established a benchmark in our domain to evaluate the feasibility of using LLMs to map OSM tags to health-promoting activities. Three experts manually annotated the 100 most frequent tags, and final labels were selected by majority vote. We then used this expert-labeled dataset to assess the accuracy of the labels generated by different LLM classifiers. The details of the LLM annotation benchmark can be found in the Supplementary Information. The outcome indicated that GPT-4, set at a temperature of 0.9, yielded the best annotation performance of an F1 score of 0.77.

Operationalization of the taxonomy

Using the taxonomy with six categories of health-promoting activities, and GPT-4 as the best-performing annotation model, we ran the annotation of OSM tags describing park elements and park spaces. These tags were then labeled with one of the health-promoting activities, or ‘none’ if they did not support a particular activity. In doing so, we established a lexicon of park elements and spaces linked to health-promoting activities (Extended Data Table 1). We had to exclude the mindfulness activities category at this stage, as none of the OSM tags found in parks was primarily associated with it.

Computing park health scores by aggregating OSM tags

The core method to characterize parks in terms of their potential for health-promoting activities is based on counting the respective park elements and spaces. These counts are then combined to give each park an overall score for each health-related category. This score represents the potential health benefits of each park.

Counting health-promoting elements and spaces in parks

In our process of assigning health-promoting activity scores to each park, we first gathered park elements and spaces within each park using the osmium library. We then assigned health-promoting activities to these elements and spaces based on the lexicon created in the previous step (Extended Data Table 1). We discarded any elements or spaces whose tags did not match an activity category. In a few instances, park elements or spaces could fall into more than one health-promoting activity category. For example, apple trees are annotated in OSM with the tags [natural=tree, produce=apple]. In our lexicon of park elements and spaces, we map natural=tree to the nature appreciation and produce=apple to the environmental category. To account for this overlap, we proportionally assign the element as 50% nature appreciation and 50% environmental. More generally, when multiple tags are matched to different categories, we proportionally count the resource based on the number of matched tags, ensuring that its contributions are accurately accounted for, thus avoiding underestimating secondary activities of multipurpose facilities.

Transforming counts into health scores

After tallying up the park elements and spaces within the park, we measured the overall effect of the park in promoting healthy activities within a city. This score should account for the park’s size and the range of facilities it offers for different activities. Our proposed scoring method is based on the following considerations.

-

(1)

Amount of health-promoting elements and spaces: The number and area of health-promoting facilities determine how much offering there is for each activity.

-

(2)

Area of the park: The character of a park depends on the concentration of health-promoting facilities. Larger parks must offer more to obtain a high score.

-

(3)

Diminishing returns with increased count: We posit that, as the count of these elements and spaces increases, the associated benefits exhibit diminishing returns.

-

(4)

City-specific normalization of park health scores: The value of a park’s facilities for a certain activity is relative to similar facilities in other parks throughout the city.

To reflect these assumptions into our scoring, we proposed a linear regression model to compute the park health scores shown in equation (1). We used the idea of an ‘average park’ in each city to compute a baseline and used the distance of each park to the average park line, that is, the residual, as a score. The average park baseline was determined by computing separate linear regression models for park elements and spaces in each city, estimating the expected amount of facilities relative to the park area.

where i and s represent the intercept and slope of the regression lines, respectively. To obtain regression models for each activity category and both park elements and park spaces, we utilized the binary logarithm to account for the diminishing returns of an increase in park size. For each city, separate regression models were calculated for each activity category, as well as for park elements and park spaces, which is further detailed in the Supplementary Information.

By analyzing the residuals, we identified parks that exceeded expectations (positive residuals) and those that fell short (negative residuals) in providing health-promoting resources for a given activity. We made the linear model dependent on park area so that the resulting scores for health-promoting elements and spaces reflected their density. To reduce the influence of extremely large parks with high amounts of facilities, we applied the binary logarithm. We calculated these scores separately for each city, rather than using a single global model, to ensure that the results reflected each city’s local context. To illustrate this method, we plotted the linear models and the individual park scores in the log–log space for London, UK (Fig. 2). The regression lines denote expected health scores based on park size. The modest R2 values showed that the number of health-promoting facilities could not be explained by park size but instead reflected different design priorities and the needs of local citizens. Park scores for park elements and spaces are residuals from this average park line in the model, adjusting for park size when determining health scores.

Combining scores from park elements and spaces

The regression models gave us individual scores for park elements and park spaces for each activity. To verify the impact of combining these scores into one combined health score, we examined the co-occurrences of park elements and spaces and found that they represent orthogonal concepts in practice, as shown in Extended Data Table 4. Based on this finding, we computed a combined score by first normalizing the scores of park elements and spaces using the z-score transformation, considering all parks in a city. This normalization allowed us to standardize the scores, making them comparable despite being on different scales. Then, we linearly combined these z scores by averaging them together to create the overall score for the park according to equation (2).

where P denotes an individual park, Act is one of the activity categories, the residual scores for elements and spaces stem from equation (1), and z() indicates the z-score transformation.

The combined and normalized scores of park elements and spaces represent a comprehensive and unified measure of the park’s health-promoting amenities and facilities, accounting for both individual elements and cultivated areas. The combination process accounted for the relative importance of each aspect, leading to a more meaningful overall score that represents how well a park is equipped to support performing health-promoting activities. Because the scores are based on z-score-normalized residuals, a value around 0 indicates average support for a given activity, while a score of ±1 means the park is 1 standard deviation above or below the city-wide average.

Quantifying disparities of park scores

One goal of our study was to quantify disparities in health benefits offered by different parks within a city. To measure the disparities in the presence of amenities and facilities associated with health-promoting activities within a city, we propose the following disparity index. The metric essentially quantifies the inequality of the park health scores, as, generally, one could expect that good park management would provide for a similar amount of features and facilities in all parks of a city. As the park health scores could be negative, we cannot directly use a standard inequality metric, such as the Gini index, but had to min–max normalize the park score before computing the Gini index (equation (3)).

where XAct is the score of activity category Act ∈ [physical, cultural and so on] of a park P in city C, and

and the Gini index was computed in a standard way:

where A is the area between the Lorenz curve and the line of perfect equality and B is the area beyond the Lorenz curve64.

Semantic matching of Flickr labels and OSM tags

In our validation, we leveraged a global dataset of 10.7 million geotagged Flickr images taken within parks across 35 cities. Each image came with user-generated tags, partially annotated by computer vision algorithms. To semantically match these Flickr labels to OSM tags, we used text embeddings, treating the task as an asymmetric semantic search problem. To overcome language diversity in the Flickr labels, we detected the top three non-English languages per city and translated the labels into English using machine translation models. To further improve embedding quality, we enriched OSM tags with concise definitions from the OSM mapping guidelines. The embeddings were generated using the all-mpnet-base-v2 S-BERT model, and matching was done based on cosine similarity, with a threshold of 0.7 to ensure quality. The methodological details are described in the Supplementary Information.

This process yielded 2,171 Flickr-to-OSM matches, with 1,432 corresponding to health-promoting features. To assess accuracy, three experts reviewed the 20 most frequent label–tag matches for London. We aggregated their responses using majority voting. The experts’ annotation agreed with 82% of the matchings, which is highly accurate considering they are based solely on individual tags.

Having assured that the matchings are accurate, we proceeded to profile the parks based on the activities associated with the matched OSM tags, following the same scoring approach as what we used for the OSM park elements and spaces (equation (1)). In our validation, we chose a minimum of 250 images from each park and at least 15 parks in each city. This criterion was established to secure a robust number of images for each park, thus ensuring the accuracy of our analysis. This was a mitigation against potential biases that could have been introduced by individual photographers if a park had only a few images.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The replication package contains tables of the park health scores in the cities available at https://social-dynamics.net/healthy-parks/replication. The original OpenStreetMap data used for scoring the parks are publicly available and can be best obtained from one of the third-party download servers, for example from https://download.geofabrik.de. The Flickr dataset for the validation cannot be shared due to the terms of conditions of this dataset.

Code availability

The Python and R code to compute park health scores is available at https://social-dynamics.net/healthy-parks/replication.

References

Kadakia, K. T. & Galea, S. Urbanization and the future of population health. Milbank Quart. 101, 153–175 (2023).

Wu, S., Chen, B., Webster, C., Xu, B. & Gong, P. Improved human greenspace exposure equality during 21st century urbanization. Nat. Commun. 14, 6460 (2023).

Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P., de Vries, S. & Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 60, 587–592 (2006).

Dzhambov, A. M. & Dimitrova, D. D. Elderly visitors of an urban park, health anxiety and individual awareness of nature experiences. Urban For. Urban Green. 13, 806–813 (2014).

Takano, T., Nakamura, K. & Watanabe, M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: the importance of walkable green spaces. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 56, 913–918 (2002).

Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., de Vries, S. & Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 35, 207–228 (2014).

Twohig-Bennett, C. & Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 166, 628–637 (2018).

Ulrich, R. S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 224, 420–421 (1984).

Ulrich, R. S. in Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations (eds Cooper, M. C. & Barnes, M.) 27–86 (John Wiley & Sons, 1999).

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J. & Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 19, 1207–1212 (2008).

Jennings, V. & Bamkole, O. The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space: an avenue for health promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 452 (2019).

Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Khreis, H., Triguero-Mas, M., Gascon, M. & Dadvand, P. Fifty shades of green: pathway to healthy urban living. Epidemiology 28, 63–71 (2017).

Rook, G. A. W. Regulation of the immune system by biodiversity from the natural environment: an ecosystem service essential to health. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18360–18367 (2013).

Hanski, I. et al. Environmental biodiversity, human microbiota, and allergy are interrelated. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8334–8339 (2012).

Barton, H., Thompson, S., Burgess, S. & Grant, M. The Routledge Handbook of Planning for Health and Well-being: Shaping a Sustainable and Healthy Future (Routledge, 2015).

Gall, A. R. L., Lemaire, N. & Jabot, F. Lessons learned from co-constructing a guide on healthy urban planning and on integrating health issues into environmental impact assessments conducted on french urban development projects. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal 36, 68–80 (2018).

Kaczynski, A. T., Potwarka, L. R. & Saelens, B. E. Association of park size, distance, and features with physical activity in neighborhood parks. Am. J. Public Health 98, 1451–1456 (2008).

Pietilä, M. et al. Relationships between exposure to urban green spaces, physical activity and self-rated health. J. Outdoor Recreation Tourism 10, 44–54 (2015).

Campbell, K. Rethinking Open Space, Open Space Provision and Management: A Way Forward (Scottish Executive Central Research Unit, 2001).

Campbell, L. K., Svendsen, E. S., Sonti, N. F. & Johnson, M. L. A social assessment of urban parkland: analyzing park use and meaning to inform management and resilience planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 62, 34–44 (2016).

Patwary, M. M. et al. Nature exposure and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a navigation guide systematic review with meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 356, 124284 (2024).

Brown, G. A theory of urban park geography. J. Leisure Res. 40, 589–607 (2008).

Tu, X., Huang, G., Wu, J. & Guo, X. How do travel distance and park size influence urban park visits? Urban For. Urban Green. 52, 126689 (2020).

McKenzie, T. L., Cohen, D. A., Sehgal, A., Williamson, S. & Golinelli, D. System for observing play and recreation in communities (SOPARC): reliability and feasibility measures. J. Phys. Activity Health 3, S208–S222 (2006).

Bedimo-Rung, A. L., Gustat, J., Tompkins, B. J., Rice, J. & Thomson, J. L. Development of a direct observation instrument to measure environmental characteristics of parks for physical activity. J. Phys. Activity Health 3, S176–S189 (2006).

Mishra, H. S. et al. The development of a tool for assessing the environmental qualities of urban blue spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 49, 126575 (2020).

Floyd, M. F., Spengler, J. O., Maddock, J. E., Gobster, P. H. & Suau, L. J. Park-based physical activity in diverse communities of two U.S. cities: an observational study. Am. J. Prevent. Med. 34, 299–305 (2008).

Kaczynski, A. T., Stanis, S. A. & Besenyi, G. M. Are park proximity and park features related to park use and park-based physical activity among adults? Variations by multiple socio-demographic characteristics. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Activity 11, 146 (2014).

Jimenez, M. P. et al. Associations between nature exposure and health: a review of the evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 4790 (2021).

Xiao, Y., Wang, D. & Fang, J. Exploring the disparities in park access through mobile phone data: evidence from Shanghai, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 181, 80–91 (2019).

Wolch, J. R., Byrne, J. & Newell, J. P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: the challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 125, 234–244 (2014).

Bolte, A.-M., Kistemann, T., Dehbi, Y. & Kötter, T. (Un)just distribution of visible green spaces? A socio-economic window view analysis on residential buildings: the City of Cologne as case study. J. Geovis. Spatial Anal. 9, 17 (2025).

Anguelovski, I. et al. Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nat. Commun. 13, 3816 (2022).

Rigolon, A. & Németh, J. Green gentrification or ‘just green enough’: do park location, size and function affect whether a place gentrifies or not? Urban Stud. 57, 402–420 (2020).

Montgomery, C. Happy City (Penguin, 2015).

Jolé, M. The public of parks: in between observation and action. the example of Paris. Urbani Izziv 19, 169–173 (2008).

Fujita, K. & Hill, R. C. Residential Income Inequality in Tokyo and Why it Does Not Translate into Class-based Segregation. in Residential Segregation in Comparative Perspective (eds Fujita, K & Maloutas, T.) 37–68 (Routledge, 2016).

Post, H. C. Best in the world. Hans Chr. Post https://www.hcpost.dk/portfolio-item/best-in-the-world (accessed 11 June 2025).

Bortz, M. et al. Disaggregating health inequalities within Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2002–2010, by applying an urban health inequality index. Cadernos Saude Publ. 31, 107–119 (2015).

Sun, L., Chen, J., Li, Q. & Huang, D. Dramatic uneven urbanization of large cities throughout the world in recent decades. Nat. Commun. 11, 5366 (2020).

Klein-Hewett, H. Classifying rural parks: a case study in Iowa. J. Park Recreation Admin. 42, 1–18 (2024).

Chen, B. et al. Contrasting inequality in human exposure to greenspace between cities of global north and global south. Nat. Commun. 13, 4636 (2022).

Long, X., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y. & Zhou, Q. Visualizing green space accessibility for more than 4,000 cities across the globe. Environ. Plan. B 49, 1578–1581 (2022).

Zhang, R., Peng, S., Sun, F., Deng, L. & Che, Y. Assessing the social equity of urban parks: an improved index integrating multiple quality dimensions and service accessibility. Cities 129, 103839 (2022).

Jones, R. Enticement: the role of community involvement in the management of urban parks. Manag. Leisure 7, 18–32 (2002).

Kleinschroth, F. et al. Global disparities in urban green space use during the COVID-19 pandemic from a systematic review. Nat. Cities 1, 136–149 (2024).

Goličnik, B. & Ward Thompson, C. Emerging relationships between design and use of urban park spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 94, 38–53 (2010).

Larson, L. R. et al. Urban park use during the COVID-19 pandemic: are socially vulnerable communities disproportionately impacted? Front. Sustain. Cities 3, 710243 (2021).

Šćepanović, S. et al. MedSat: a public health dataset for England featuring medical prescriptions and satellite imagery. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 77810–77851 (2024).

Heikinheimo, V. et al. Understanding the use of urban green spaces from user-generated geographic information. Landsc. Urban Plan. 201, 103845 (2020).

Zanella, A. F. et al. The digital life of Parisian parks: multifunctionality and urban context uncovered by mobile application traffic. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.15516 (2025).

Zhang, L., Tan, P. Y. & Diehl, J. A. A conceptual framework for studying urban green spaces effects on health. J. Urban Ecol. 3, jux015 (2017).

Dietz, L. W., Šćepanović, S., Zhou, K. & Quercia, D. Exploratory analysis of recommending urban parks for health-promoting activities. In 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems 1131–1135 (ACM, 2024); https://doi.org/10.1145/3640457.3691712

Li, J., Qin, H., Wang, J. & Li, J. OpenStreetMap-based autonomous navigation for the four wheel-legged robot via 3D-Lidar and CCD camera. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 69, 2708–2717 (2022).

Herfort, B., Lautenbach, S., de Albuquerque, J. P., Anderson, J. & Zipf, A. The evolution of humanitarian mapping within the OpenStreetMap community. Sci. Rep. 11, 3037 (2021).

Jacobs, K. T. & Mitchell, S. W. OpenStreetMap quality assessment using unsupervised machine learning methods. Trans. GIS 24, 1280–1298 (2020).

Li, L.-J., Socher, R. & Fei-Fei, L. Towards total scene understanding: Classification, annotation and segmentation in an automatic framework. In Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2036–2043 (IEEE, 2009); https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2009.5206718

Thomee, B. et al. YFCC100M: the new data in multimedia research. Commun. ACM 59, 64–73 (2016).

Individuals Using the Internet (% of population). (World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database, International Telecommunication Union, accessed 9 November 2023); https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS

Lin, W. Volunteered geographic information constructions in a contested terrain: a case of openstreetmap in china. Geoforum 89, 73–82 (2018).

Gilardi, F., Alizadeh, M. & Kubli, M. ChatGPT outperforms crowd workers for text-annotation tasks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, 30 (2023).

Veselovsky, V. et al. Prevalence and prevention of large language model use in crowd work. Commun. ACM 68, 3 (2025).

Ziems, C. et al. Can large language models transform computational social science? Comput. Linguist. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 50, 1 (2024).

Barrow, M. Statistics for Economics, Accounting and Business Studies (Pearson, 2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Firth, S. Law and O. Hayes for their valuable expert input. L.W.D. acknowledges support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 869764 (GoGreenRoutes).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W.D. conceived and conducted the experiments and codrafted the paper with S.Š. K.Z., A.F.Z. and D.Q. conceived the experiments and edited the paper. All authors analyzed the results and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cities thanks Lincoln Larson, Catharine Ward Thompson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Pearson correlations between park health scores and the distance to the city center by city show mostly low to moderate negative correlations.

This figure complements the findings regarding geographic influences on park health scores, subdivided by continents. Using a correlation analysis between the distance to the city center (discounted using the binary logarithm) and the park health scores, we aimed to provide an additional quantification of the decay in park scores moving away from the city center.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Inequality of park scores in the cities.

Overall, nature-appreciation activities show the lowest disparities, whereas the largest differences can be observed in the social activities category. This figure visualizes the data in Table 2.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Literature survey on health benefits of park activities, online and expert surveys, and supplementary methodological details and visualizations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dietz, L.W., Šćepanović, S., Zhou, K. et al. Understanding the potential of urban parks to promote well-being. Nat Cities 2, 1205–1216 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00345-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00345-4