Abstract

Cities generate wealth from interactions, but citizens often experience segregation in their daily urban movements. Here, using GPS location data, we identify patterns of this experienced segregation across US cities, differentiating between neighborhoods that are sources and sinks—exporters and importers—of diversity. By clustering areas with similar mobility signatures, capturing both the diversity of visitors and the exposure of neighborhoods to diversity, we uncover a generic mesoscopic structure: rings of isolation around cities and internal pockets of segregation. Using a decision tree, we identify the key predictors of isolation and segregation: race, wealth and geographic centrality. We show that these patterns are persistent across time and prevalent across all US cities, with a trend toward larger rings and stronger pockets after the pandemic. These findings offer insights into the dynamics that contribute to inequality between neighborhoods, so that targeted interventions promoting economic opportunity can be developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The free flow of people, goods and ideas drives urban agglomeration. Cities enable ‘sharing, learning and matching’ to generate efficient and innovative economies1: shared infrastructure, shared ideas and pooled workers drive the dominance of urban systems in the economy today. By extension, cities that fail to integrate communities or struggle to connect residents may sacrifice growth2 or exacerbate poverty3,4. A large body of literature documents housing segregation by race and class, and recent developments, including mobile phone location data, enable us to investigate segregation in daily life as people move around the city5,6, revealing bias in who interacts with whom. Because urban innovation and prosperity hinge on diverse interactions7,8, understanding the nature, extent and limitations of how groups interact is essential to understanding and building inclusive economies.

Cities in the USA exhibit ‘hypersegregation’, the separation and concentration of nonwhite populations in contiguous zones, typically near the urban core9—often a result of discriminatory institutions10. While hypersegregation implicitly involves isolation across multiple dimensions, Global Positioning System (GPS) mobility data reveal that ‘experienced segregation’—where people are more likely to share spaces with others of the same race5 and class6—is a key component, affecting crime rates and economic opportunities11. Yet, recent work emphasizes that nearby venues can have distinct visitor profiles6,12, suggesting that sorting occurs beyond residential confines. Studies also indicate that amenity location can mediate interactions between groups13,14. Mixing across strata often involves lower-class individuals visiting higher-class areas15—a pattern consistent with hypersegregation and ‘compelled mobility’16, which involves disinvestment and consequent travel for basic services.

This matters because generating connections between groups and across communities may create wealth and reduce inequality. Early work on segregation implicates the lack of ‘exposure’ between different groups in creating economic inequalities17. While work on experienced segregation measures exposure, not necessarily interaction, mobility links to social ties and their social and economic consequences. Activity spaces—the bounds of our routines in space—influence social connections18,19, with particular consequences for ‘weak ties’20 that generate social and economic mobility. Employment opportunities within an individual’s activity space predict job attainment21. Housing segregation correlates with low social capital and social mobility22,23, but recent work finds that areas with venues that encourage mixing also tend to have greater social capital and social mobility24. Neighborhood connectivity—including who visits and where residents go—predicts homicide rates, with the most disadvantaged communities being those defined by both residential and experienced segregation11.

Although the literature on experienced segregation is growing25, recent research tends to focus on human behaviors6,15,19,24,26,27 or urban comparisons5,13,28,29. These microscopic and macroscopic views often neglect the mesoscopic clusters of neighborhoods within and around cities that drive mixing or isolation, and the forces that generate these zones. Yet, the mesoscopic level is where phenomena such as hypersegregation9 operate—creating not just isolated neighborhoods but interconnected systems of disadvantage. Limited connections to the broader economy create ‘truly disadvantaged’ communities30, but new connections ameliorate some of these problems31,32,33. The location and concentration of experienced segregation reveals not just who is isolated but also who is surrounded by isolation, hindering new connections.

Here, we seek to identify the broader zones of mixing and isolation that define cities. How residents interact with the broader city reveals inequalities between groups, as certain groups or places may make uneven contributions to aggregate urban mixing. This work investigates the mesoscale of mixing in US cities with a spatially and temporally expansive sample of cell phone GPS records covering the continental USA over 4 years. We focus on visits to amenities as they represent both primary attractions where populations purposefully interact13,24 and structured environments where social connection occurs34. We present two key measures: amenity segregation, representing the degree to which visitors to an amenity are diverse, and neighborhood isolation, indicating the degree to which travelers from a neighborhood experience diversity in their day-to-day activities. Combined, these related measures reveal distinct patterns, including neighborhoods—and clusters of neighborhoods—that export diversity to the broader city without importing it. Our approach allows us to empirically identify clustering as a dimension of experienced segregation, revealing spatial structures that would be obscure at the scale of either the city or neighborhood.

Results

Data and methods

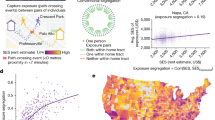

To assess experienced segregation across multiple dimensions, we construct measures for diversity and exposure in terms of socioeconomic class. We process data from a location data provider35 to create origin–destination flows from neighborhoods (census block groups) to points of interest (POIs; for example, restaurants, shops, museums and hospitals) over a period from January 2019 through December 2022. We combine these data with Census estimates of median income36 to infer the socioeconomic strata of visitors from each area by attributing to each visitor the median income of the block group where they live. We compute the ‘diversity’ of visitors to amenities and the ‘exposure’ of neighborhood residents to diversity. Borrowing from prior work6, our measures represent distance from a counterfactual scenario where interactions draw equally from each socioeconomic stratum in a given city. We examine amenity segregation (low level of diversity of visitors to an amenity) and neighborhood isolation (low level of exposure of residents to diversity in the amenities they visit), considering an amenity highly segregated if it attracts visitors from just one income bracket, and residents highly isolated if they only visit such amenities. Both measures range from 0 to 1, where 0 is perfect diversity or exposure and 1 is perfect segregation or isolation. Detailed in the Methods, we illustrate our process in Fig. 1.

Residents from neighborhoods with different median incomes visit amenities. Amenities are segregated if they attract visitors from a similar income bracket; neighborhoods are isolated if their residents visit segregated amenities during their daily activities throughout the city. Icons adapted from OpenStreetMap Carto under a Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 2.0 (ref. 56).

Segregation and isolation

We can think of a neighborhood as isolated (I) and an amenity, or POI, as segregated (S). These are illustrated in Fig. 2 for a sample of ten large cities. While previous work6 emphasizes variability between nearby amenities, showing that a pair of adjacent amenities may have opposite diversity signatures, Fig. 2a shows that these form distinct clusters of both segregation and diversity. Our sample includes cities with different spatial structures, from sprawling ‘sunbelt’ cities like Houston and Dallas to dense ‘rustbelt’ cities like Chicago and Philadelphia. The latter tend to have pockets of segregation, such as North and West Philadelphia, the south side of Chicago and the South Bronx in New York. By contrast, Houston and Dallas are more integrated. Cutting against this distinction, Los Angeles has a large pocket of segregation in South Los Angeles—a historically disadvantaged neighborhood. Prior work has shown that hypersegregated populations have historically been located near downtowns, confined to contiguous areas9,17, much as we observe here.

Each city map is centered on downtown. a, Amenity segregation, where each point represents an amenity, shows that downtown businesses tend to see a diverse collection of visitors (and thus have low amenity segregation) but that businesses in surrounding neighborhoods often do not (and have high amenity segregation). Many of the wealthiest parts of the city, shown in black, also have fewer POIs, which limits visitation and thus the diversity. b, Neighborhood isolation is strong in those same wealthy areas with fewer amenities and also in areas with segregated amenities.

One channel by which segregation is determined is in the mix and number of amenities in a cluster: fewer reasons to visit will limit visitors. Many wealthy areas—shown in black—simply have fewer amenities, and less variety of them. Showing this correlation in Supplementary Table 4, we see examples of this in Dallas, Phoenix, Washington and Los Angeles—corresponding with Bel-Air and other wealthy enclaves in Fig. 2a.

To understand the relationship between segregation and isolation, we bin each by quantile and construct a 3 × 3 matrix that classifies each neighborhood by its performance on both measures. A neighborhood that is completely integrated, with diverse amenities and with residents visiting diverse amenities, will be in the first quantile along both dimensions, segregation and isolation. Vice versa, homogeneous amenities and residents visiting homogeneous amenities will be in the third quantile for both. Residents may also find exposure to diversity away from home, and neighborhoods with them will be in a low quantile for isolation and a high quantile for segregation. Furthermore, because we capture segregation at the level of the amenity, we capture sorting into amenities with a given demographic profile even as the neighborhood around them receives a different selection of visitors.

In Fig. 3a, we find that many cities are surrounded by rings with high segregation and high isolation. In the Boston–Washington megalopolis, many of these rings merge into large intercity zones. Looking within cities, we see that there are areas where visitors are diverse but exposure is low (Fig. 3b, aqua-colored areas): residents sort into amenities that allow them to avoid ambient diversity. These neighborhoods are ‘heterophobic’, and they are typically central and affluent. The opposite also occurs, often in the same cities (Fig. 3b, pink-colored areas): ‘heterophilic’ neighborhoods in Chicago and New York have residents that experience diversity despite living in a neighborhood that sees little of it. We again see that historically deprived neighborhoods, such as the South Bronx or South Los Angeles, are often both segregated and isolated. To understand these neighborhoods, we plot distributions of selected variables by class in Fig. 3c (expanded to include amenity distributions in Fig. 3): neighborhoods that export diversity without importing it tend to exist at a certain distance from downtown, with characteristic socioeconomic attributes—high nonwhite populations and low incomes. They also tend to have fewer amenities, while areas with residents who appear to avoid diversity have more—possibly enabling sorting.

a, Mapping diversity and exposure nationally, we see that integrated urban areas are often surrounded by rings of isolated suburban areas. b, Locally, we see urban pockets of segregation with a range of low to high isolation, often near or surrounded by integrated urban areas. c, Distributions of selected variables by class show that segregated areas are often close to the center, poorer than average and nonwhite.

Many of the urban pockets we see have been victims of federal, state or local policies to produce segregation—or at the very least a policy failure to remedy segregation10. In Supplementary Fig. 4, we show that areas that were given poor grades—usually due to prejudice against nonwhite residents—by the Home Owners Loan Corporation in the 1930s still exhibit higher levels of segregation today, and areas that were not graded at all—because cities had not sprawled out into the suburbs until later in the century—exhibit higher levels of isolation. These ungraded areas are likely to be the very places that excluded nonwhite families. This suggests that some of what we see in the data is the result of policy. We document structural developments that may have influenced certain pockets in Supplementary Note 5.

We include sensitivity analyses and robustness checks in Supplementary Notes 6–9 in which we show that neither home nor work location are unlikely to be the cause of these patterns, suggesting at least some degree of sorting on preference or on price (Supplementary Fig. 11).

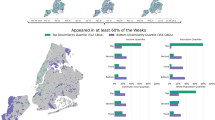

Zones of segregation and isolation

To understand how these measures of interaction manifest in the structure of cities, we use tests for spatial autocorrelation to identify contiguous zones of amenity segregation or neighborhood isolation. These tests show that at both local and regional scales there are large areas where high values cluster. Segregation and isolation exist at characteristic scales, with the latter clustering in suburban rings (Fig. 4a) and the former clustering in certain urban pockets (Fig. 4c). We take the top 100 cities and subtract the central business district (CBD) coordinates from each so they stack on top of each other (Methods). In Fig. 4b, we show the composite pattern by counting the number of isolated clusters from all cities at each location relative to their centers. This reveals the relationship between centrality and isolation, showing that these rings form at similar relative distances across different cities regardless of geography. Compared with clusters of isolation, which tend to be suburban, segregation tends to be urban and the clusters tend to exist at a smaller, more fragmented scale. Figure 4c shows that large cities—New York, Los Angeles and Chicago—also tend to have larger concentrations of segregation, compared with small cities such as Atlanta and Boston.

a, Isolation autocorrelation manifests at the national scale, delineating rings around cities. b, Centering and layering the cities, we count the number of times isolated zones occur in the same relative area: there is a clear prevalence of these zones in a ring surrounding each urban core. c, Segregation autocorrelation manifests locally, with pockets appearing in large cities—less so in smaller cities such as Atlanta or Boston. d, We also see tight scaling relationships between city size and isolation/segregated population, with a linear relationship between city population and the population in isolated zones, along with a superlinear relationship for city population and its segregated zones.

Isolated populations in these zones scale predictably with city size, shown in Fig. 4d. For isolated clusters, the relationship is superlinear (β = 1.27); larger cities present larger concentrations of isolation. The population in segregated clusters scales superlinearly (β = 1.37) with the population of the city. As cities become larger, separated areas with limited visitation become larger at a faster rate. Large areas visible in big cities (New York and Chicago) and less so in smaller cities (Atlanta and Boston) in Fig. 4c.

Trends and drivers

We use a decision tree, shown in Fig. 5a, to understand what defines each class of our 3 × 3 scheme. We append attributes to each neighborhood using data from the Census to serve as predictors, shown in Table 1. We also measure the distance to the CBD, identified earlier. These become predictors in our model, which provides us with an intuitive, step-by-step way to see which variables predict which class in order of importance. Points of decision include richer or poorer, densely or sparsely populated, predominantly white or nonwhite, and centrally or peripherally located. For example, we can ask what is the most common class of a neighborhood that is near the center, predominantly nonwhite, relatively dense and relatively poor.

a, Decision tree showing the defining characteristics of different classes, pruned for ease of viewing. Shown with dashed boxes, note that top segregated and isolated classes are the wealthiest cut, but also urban nonwhite—as indicated by density. The areas that have high segregation but low isolation tend to be urban, nonwhite and moderately dense. b,c, Partial dependence plots for segregation (b) and isolation (c) showing the joint relationship between distance to the CBD (Dist. CBD) and key variables, with dashed boxes highlighting rings of isolation conditional on white/wealthy and pockets of segregation conditional on nonwhite/poor.

Our complete tree, shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, achieves an accuracy of 30%, a threefold improvement across what would be expected if assigning classifications from the 3 × 3 matrix to neighborhoods at random. Supplementary Fig. 17 shows the importance of each feature in the tree, using a permutation technique that shuffles each column and computes the resulting reduction in predictive ability. Income, along with measures of urban structure such as density and distance from center, are the most important predictors. This ranking suggests that, along with income, urban form and function, including the distribution of amenities, may be important determinants of segregation and isolation. Proximate branches in the pruned tree in Fig. 5a indicate that both the wealthiest neighborhoods and dense, nonwhite neighborhoods are the most segregated. The populations most likely to have high segregation and low isolation are nonwhite. In less affluent and less white communities, the presence of amenities is associated with a greater diversity of visitors.

The data suggest that employment is not important. Insofar as a job represents a connection to the broader urban economy, we might expect the size of the working population to predict isolation above and beyond income. Instead, the best model uses income and race, along with spatial structure, to estimate isolation and segregation. This aligns with the weak correlation between commutes and mixing: where you work does little to increase exposure if you sort into venues with audiences similar to yourself.

The decision tree allows us to explore the relationship between key variables conditioning on all other predictors37, modeling the interactions in the data. Figure 5b,c show the model’s estimated values for segregation and isolation, respectively, given certain conditions; it asks, given these values for demographic, economic or geographic features, what do we expect the segregation and isolation to be?

The patterns are clear: if a neighborhood is close to its downtown, its amenities are more integrated, unless it is majority nonwhite; if a neighborhood is far from its downtown, it is more isolated, unless it is majority nonwhite. The relationship between location and demographic composition creates quadrants that correspond to higher or lower segregation. The tree indicates that race is the most important driver of amenity segregation: the highest modeled estimates for amenity segregation come in neighborhoods with large nonwhite populations—regardless of how central they are. Wealthy neighborhoods also have more segregated amenities, but only if they are majority white. The rings around each city are also evident in these distributions, with segregated suburbs becoming comparably less segregated exurbs—which are also less expensive—at the farthest extents of the city.

Given the potential consequences for segregation and isolation, we link these measures of spatial mobility to social mobility—the likelihood that a child will earn more than her parents—in Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14. In brief, higher segregation and isolation correspond with better outcomes, suggesting strong selection effects—except for areas with more than 75% nonwhite residents, where the effects go negative. This indicates that connections to the broader city are important for some groups but not others.

Temporal variations

Across time, the bivariate class composed of the most segregated and isolated areas, flowing across the top of Fig. 6a, became larger during the pandemic but has since returned to its 2019 fraction of the total. The class composed of the least segregated amenities, flowing across the bottom, has not recovered—an indication that downtowns are less places of mixing than before. Despite this churn, transition probabilities are low at the extremes, which we show in Supplementary Fig. 15: most and least integrated areas typically remain so. Confirming previous work26, experienced segregation peaked during the pandemic; we extend this work through 2022, showing that levels of segregation and isolation have returned to 2019 in many cities. Computing the average values for I and S per city in Fig. 6b shows that, aside from San Francisco and Boston, the distribution has largely returned to its index value.

a, Trends for classes of segregation showing that segregation peaked in April of 2020, but shows little change today. b, We compute city averages for I and S and see that levels changed in many cities during the pandemic but have returned to normal in most—notably not San Francisco. c, Changes to dependencies over years, following the same logic as above with distance to the CBD on the vertical axis and variables of interest on the horizontal axes (nonwhite population and income): relative to the 2019, lower values for nonwhite population and median income generate high expected segregation near the center; more distance bands generate high expected isolated even at higher values for nonwhite population and lower values for median income. Dashed boxes show that central areas have higher expected segregation at all income levels and peripheral areas have higher expected isolation at all nonwhite levels.

To understand how this change manifests in the structure of cities, we track how the partial dependencies have shifted over time in Fig. 6c. Most predictions, either for segregation or isolation, shift to higher values throughout the study period. A notable change occurs in the band representing wealthy neighborhoods close to the urban core, which become more segregated in 2021 and 2022 despite proximity to downtown amenities that facilitated mixing in 2019. Our 2019 model expects urban areas with 90% nonwhite populations showed high amenity segregation prepandemic. In the 2022 model, this dropped to 80%. Urban areas 5–10 km from city centers with US$200,000 median incomes saw segregation indices rise from S = 0.4 in 2019 to S = 0.5 in 2022—a 20% increase. The rings that we see around cities above also extend out: predictions for isolation become higher beyond 75 km, where the highest predictions ended in our 2019 baseline. In these exurban areas or satellite cities greater than 75 km from the city center, the average estimated isolation rises from I = 0.25 to I = 0.35 where neighborhoods are majority white.

We also see little change in the rank importance of features over the period analyzed here (Supplementary Fig. 17). Although it maintains its rank importance, the level of importance of distance to the CBD does drop in 2021 and 2022, suggesting that we may be seeing changes to the spatial structure of segregation and isolation.

Discussion

While prior work highlights subtle variations between adjacent venues6,12, here we show that cities often have a structure that minimizes mixing in some areas while maximizing it in others. Our analysis reveals that cities are composed of spatially contiguous zones of isolation and segregation, where residents primarily interact with socioeconomically similar others. External rings can often stretch for great distances, encompassing large populations. Internal pockets, those exhibiting high segregation and either high or moderate isolation, resonate with concepts of the ‘ghetto’38, a spatial arrangement that allows economic participation while maintaining social separation. The mesoscopic view then advances our understanding of experienced segregation by documenting the twin experienced concentration of affluence and poverty, opportunity and disadvantage, building on earlier work on socioeconomic extremes in cities39.

Studies documenting experienced segregation often fail to distinguish areas where diverse encounters happen from areas where residents must travel to encounter diversity5,6,13. Recent work highlights the ‘compelled mobility’ of nonwhite residents who often travel outside segregated home neighborhoods to access resources16. Our findings align with this, showing some segregated areas (for example, South Chicago) whose residents experience diversity elsewhere, yet also identifying isolated pockets (for example, South Los Angeles) where both residential and experiential segregation coincide indicating disadvantage11. The other side of this are isolated areas (for example, most suburbs) where residents avoid diversity. While exposure offers social benefits22,24,31,33, travel for amenities may disadvantage businesses in isolated and segregated communities.

A key limitation of our study is its focus on the USA, but our findings have broad implications for policy in US cities. Research shows that ‘disadvantaged’ communities30 often have limited connections to the surrounding labor market40. Long ties in particular allow individuals to reach beyond their immediate communities, and these ties are grounded in activity spaces18,41,42. We identify disconnected neighborhoods that are in turn clustered with disconnected neighborhoods; individuals living in these areas are less likely to interact with the surrounding city and less likely to interact with someone who is connected to that broader economy, because the entire community in which they exist is disconnected. Constructing long ties will require connections between rich and poor communities—both the rings and the pockets in our study. Interventions should leverage zoning and land use to develop amenity clusters in accessible locations between zones13, while investing in downtowns to restore them as places of mixing.

Although our topic intersects with racial segregation in the USA, our mobility data do not include information on race/ethnicity. To avoid ecological misclassification, we do not impute race/ethnicity from neighborhood composition and restrict our primary segregation metrics to income. Future work that links mobility to validated individual demographics is needed to assess racial/ethnic patterns and inform policy.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and remote work are rewiring urban interaction networks43,44. Research documents pandemic changes in mobility generally45 and experienced segregation specifically26, finding that COVID-19 resulted in considerable changes to daily routine and to socioeconomic mixing. The office46 and the commute47 are key determinants of ‘third places’48—shops, restaurants and cafes—we visit throughout the day. Furthermore, a postpandemic ‘introvert economy’49, with fewer nights out, has developed. Our results indicate that urban interaction patterns continue to evolve.

Changing work and leisure dynamics may have important consequences for social mobility, social capital and the relative economic advantage and disadvantage of neighorhoods. These dynamics may reinforce both concentrated advantage (‘rings’) and concentrated disadvantage (‘pockets’), making connections between these extremes even harder to establish—potentially exacerbating the ‘age of extremes’, marked by concentrated poverty and affluence39. Understanding these shifts is critical for creating opportunity, as interventions need to adapt to new mobility and interaction realities.

Methods

With the goal of assessing experienced segregation along multiple dimensions, we construct measures for diversity and exposure for both socioeconomic class and race. To achieve this, we use data from SafeGraph35, a location services provider, to construct origin–destination flows from neighborhoods (Census block groups) to POIs. SafeGraph gathers GPS locations from mobile phones by aggregating data from applications who have obtained user consent to passively monitor location, creating a sample of users comprising ~10% of the population. Their process assigns visits to POIs by clustering GPS pings and joining these clusters to adjacent building polygons, using relative distances and time of day to manage conflicts35. The data have been used in a variety of academic contexts50,51, and we validate the data in Supplementary Note 1 to show that the number of devices in a block group shows a strong correlation with population and no detectable correlation with income or race, which would indicate systematic bias. The result is a rectangular matrix consisting of 220,000 origin home block groups (a Census aggregation with a population of ~1,000) and 7 million destination POIs such as restaurants, museums, cafes, car dealers or grocery stores. To each origin, we append Census estimates from the American Community Survey36 of median income and nonwhite population to infer socioeconomic strata and demography of the visitors from that area. With these we can compute the ‘diversity’ of (visitors to) POIs and the ‘exposure’ of (residents in) neighborhoods to diversity.

Measuring intergroup interaction

We look at amenity segregation and neighborhood isolation. The first asks, how diverse are visitors to this place? The second asks, how much diversity are residents from this neighborhood exposed to in daily routine? Segregation captures the patrons at a given amenity, or POI, which we can then use to compute isolation at the level of the neighborhood by taking the weighted average of segregation at POIs visited by the residents of a given neighborhood. The measures we construct represent deviations from a counterfactual scenario where visitors to an amenity draw equally from each socioeconomic stratum in a given city. If a restaurant attracts visitors from just one income bracket, calibrated within that metropolitan area, we consider that amenity to be highly segregated; if residents from a neighborhood go only to restaurants like that one, we consider them to be highly isolated. Diversity and exposure are the inverse of segregation and isolation. We illustrate this process in Fig. 1.

Conceptually, segregation is inversely related to the diversity of visitors at an amenity (low segregation S means high visitor diversity), while isolation is inversely related to residents’ exposure to diversity during their activities (low isolation I means high exposure to diverse amenities). While mathematically related through the calculation of isolation from segregation, they capture distinct aspects of urban mixing: the nature of individual places versus the aggregated experience of neighborhood residents.

Following earlier work6, we consider the segregation S of an amenity α to be a distance from an ideal scenario where people from all socioeconomic classes visit in equal proportions. This is defined as follows:

where q represents an income quintile and ν represents the portion of visitors from that quintile. We scale that by \(\frac{5}{8}\) so that each value spans 0 to 1, with 0 being perfect integration (equal proportions from all classes) and 1 being perfect segregation (visitors from a single class). Each quintile is calibrated to the metropolitan area, rather than the nation as a whole. As a robustness check, we also compute quintiles based on the nonwhite population, differentiating between neighborhoods based on the proportion of nonwhite residents.

An inherent limitation of this study is that we are assigning these classes according to area, rather than individual attributes. This leaves the possibility for misclassification, which we address through sensitivity analyses in Supplementary Note 6, where we consider how our results would change if devices were drawn from different parts of the income distribution of each block group, but we cannot be certain about the quality of our imputation. Because income is ordinal and equally partitioned while race/ethnicity is nominal with unequal base rates, our mixing measure fits income better; for race/ethnicity, ecological assignment and category collapse make the measure both noisier and more fragile in interpretation, so we treat those results as complementary rather than primary.

Neighborhood isolation I is obtained by aggregating S as follows. We compute the average diversity S for all amenities α visited by residents of a given neighborhood γ, weighted by the number of trips T between neighborhood γ and amenity α, leading to the following definition:

We then use Local Indicators of Spatial Autocorrelation (LISA)52 to show the existence of larger zones of segregation and isolation, which allows us to understand how cities are structured. Spatial autocorrelation refers to the degree to which similar values cluster together in space, and this test lets us identify the clusters of contiguous zones where residents have limited exposure to diversity. LISA measures the correlation between an areal unit and its neighbors along some dimension; if values of segregation or isolation co-occur in space, we will see clustering. We use permutations, shuffling the values of our variables of interest and recomputing autocorrelation, to test the significance of each local I value, keeping only the values for which P < 0.05. The results can be used not only to detect clusters of similar values—defined as ‘high–high’ when the index cell and its neighbors fall in the top third of segregation or isolation, and ‘low–low’ for the opposite—but also to identify the remaining combinations of high and low mixes.

To understand how regular and predictable these clusters are across cities, we then perform a transformation to align cities. We identify the ‘downtown’ by finding the largest cluster of amenities within 250 m of each other using DBSCAN53, which groups points on the basis of spatial density. We calculate the centroid of this downtown cluster by averaging all amenity coordinates, weighted by visit frequency. With this urban centroid identified, we subtract this X,Y value from all geometries of all block groups in a city. This has the effect of moving all cities to a common centroid around 0,0—stacking them on top of each other. From there, we simply count the number of high–high clusters of isolation in each part of the city using a gridded mesh to standardize the block groups. The resulting heatmap reveals the spatial distribution of isolated zones relative to city centers across our entire sample.

Dimensionality reduction

Our data span 4 years, from 2019 through 2022, which gives us the ability to assess the stability of these measures over time. To understand this, we follow the raw trends and examine the relationships among a set of variables that predict diversity and exposure. We first build a time series of segregation and isolation for each neighborhood in our data, 48 observations (months) across 220,0000 neighborhoods (all Census block groups). Monitoring every time series presents a challenge, so we divide our data into nine classes—combining three quantiles of segregation with three quantiles of isolation—at 2019 January t0, and then assign classes according to the original breaks for each month ti thereafter, tracking the size of each class throughout our sample. We also compute average segregation and isolation for each metropolitan area and track those levels as well. Because our data represent a space-time cube, where each location in space has 48 values, we explore other forms of dimensionality reduction in Supplementary Note 15.

To understand the factors associated with these trends, we construct decision trees to predict segregation and isolation at each interval. We choose this modeling strategy because the patterns in our data involve symmetries and nonlinearities, with high and low extremes of a given variable giving similar predictions, and because variables appear to interact. A decision tree manages these challenges in a manner that preserves interpretability, as we can explore the tree to see how variables are stacked to generate predictions54. The key tools we use to interpret our data are the tree itself and partial dependence plots, which show the best prediction given the values of two variables while controlling for all others37.

Our decision tree uses the following predictors, all at the level of the block group, from the Census Bureau (Table 1): median income, nonwhite population share, college educated share of adults, household size (Census Bureau), rental vacancy rate, share of rent burdened households, share under 16 years old, share unemployed and population density. We then use data from SafeGraph to construct the following metrics, also at the level of the block group: amenity count, which is the number of POIs in the block group, amenity entropy (H), which is the diversity of those POIs according to the six-digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) industry classification (for example, Restaurants and Other Eating Places). We compute it as Shannon entropy55 H = − Σp(x)logp(x) for all x where p(x) is the proportion of firms in each industry classification. We also use DBSCAN53 to identify each city’s centroid in the following way: we sort clusters of POIs within 50 m of each other by the number of POIs in them and assume that the largest cluster is the CBD; we then take the visit-weighted average latitude and longitude over those POIs and assume that that point is the city center. We then measure the distance of each block group in each city to that point, refer to it as the distance to the CBD and use it as a predictor.

We perform all analyses in the R programming language.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The processed data to reproduce to these findings, including measures of segregation and isolation, are available at https://asrenninger.github.io/diversity/.

Code availability

Code is available at https://asrenninger.github.io/diversity/.

References

Duranton, G. & Puga, D. in Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics Vol. 4 (eds Donaldson, D. & Redding, S.) 2063–2117 (Elsevier, 2004).

Harari, M. Cities in bad shape: urban geometry in india. Am. Econ. Rev. 110, 2377–2421 (2020).

Ananat, E. O. The wrong side(s) of the tracks: the causal effects of racial segregation on urban poverty and inequality. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 3, 34–66 (2011).

Cutler, D. M. & Glaeser, E. L. Are ghettos good or bad? Quart. J. Econ. 112, 827–872 (1997).

Athey, S., Ferguson, B., Gentzkow, M. & Schmidt, T. Estimating experienced racial segregation in us cities using large-scale gps data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2026160118 (2021).

Moro, E., Calacci, D., Dong, X. & Pentland, A. Mobility patterns are associated with experienced income segregation in large US cities. Nat. Commun. 12, 4633 (2021).

Ribeiro, F. L. & Rybski, D. Mathematical models to explain the origin of urban scaling laws. Phys. Rep. 1012, 1–39 (2023).

Bettencourt, L. M. The origins of scaling in cities. Science 340, 1438–1441 (2013).

Massey, D. S. & Denton, N. A. Hypersegregation in US metropolitan areas: Black and Hispanic segregation along five dimensions. Demography 26, 373–391 (1989).

Rothstein, R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (Liveright Publishing, 2017).

Levy, B. L., Phillips, N. E. & Sampson, R. J. Triple disadvantage: neighborhood networks of everyday urban mobility and violence in us cities. Am. Sociol. Rev. 85, 925–956 (2020).

Davis, D. R., Dingel, J. I., Monras, J. & Morales, E. How segregated is urban consumption? J. Polit. Econ. 127, 1684–1738 (2019).

Nilforoshan, H. et al. Human mobility networks reveal increased segregation in large cities. Nature 624, 586–592 (2023).

Noulas, A., Scellato, S., Lambiotte, R., Pontil, M. & Mascolo, C. A tale of many cities: universal patterns in human urban mobility. PLoS ONE 7, e37027 (2012).

Hilman, R. M., Iñiguez, G. & Karsai, M. Socioeconomic biases in urban mixing patterns of US metropolitan areas. EPJ Data Sci. 11, 32 (2022).

Browning, C. R., Tarrence, J., Calder, C. A., Pinchak, N. P. & Boettner, B. Geographic isolation, compelled mobility, and everyday exposure to neighborhood racial composition among urban youth. Am. J. Sociol. 128, 914–961 (2022).

Massey, D. S. & Denton, N. A. in Social Stratification, Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective 2nd edn (ed. Grusky, D.) 660–670 (Routledge, 2019).

Kovács, Á. J., Juhász, S., Bokányi, E. & Lengyel, B. Income-related spatial concentration of individual social capital in cities. Environ. Plan. B 50, 1072–1086 (2023).

Bokányi, E., Juhász, S., Karsai, M. & Lengyel, B. Universal patterns of long-distance commuting and social assortativity in cities. Sci. Rep. 11, 20829 (2021).

Granovetter, M. S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78, 1360–1380 (1973).

Cagney, K. A., York Cornwell, E., Goldman, A. W. & Cai, L. Urban mobility and activity space. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 46, 623–648 (2020).

Chetty, R. et al. Social capital I: measurement and associations with economic mobility. Nature 608, 108–121 (2022).

Chetty, R. et al. Social capital II: determinants of economic connectedness. Nature 608, 122–134 (2022).

Massenkoff, M. & Wilmers, N. Rubbing shoulders: class segregation in daily activities. J. Public Econ. 244, 105335 (2025).

Liao, Y., Gil, J., Yeh, S., Pereira, R. H. M. & Alessandretti, L. Socio-spatial segregation and human mobility: a review of empirical evidence. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 117, 102250 (2025).

Yabe, T., Bueno, B. G. B., Dong, X., Pentland, A. & Moro, E. Behavioral changes during the COVID-19 pandemic decreased income diversity of urban encounters. Nat. Commun. 14, 2310 (2023).

Cook, C., Currier, L. & Glaeser, E. Urban mobility and the experienced isolation of students. Nat. Cities 1, 73–82 (2024).

Tóth, G. et al. Inequality is rising where social network segregation interacts with urban topology. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–9 (2021).

Abbiasov, T. et al. The 15-Minute City Quantified Using Mobility Data (National Bureau of Economic Research 2022).

Wilson, W. J. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy (Univ. Chicago Press, 2012).

Chetty, R., Hendren, N. & Katz, L. F. The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 106, 855–902 (2016).

Chetty, R. & Hendren, N. The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility: childhood exposure effects. Quart. J. Econ. 133, 1107–1162 (2018).

Chyn, E. & Katz, L. F. Neighborhoods matter: assessing the evidence for place effects. J. Econ. Perspect. 35, 197–222 (2021).

Small, M. L. Unanticipated Gains: Origins of Network Inequality in Everyday Life (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009).

Determining points of interest visits from location data: A technical guide to visit attribution. SafeGraph https://www.safegraph.com/guides/visit-attribution-white-paper (2025).

American Community Survey. US Census Bureau https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/ (2024).

Goldstein, A., Kapelner, A., Bleich, J. & Pitkin, E. Peeking inside the black box: visualizing statistical learning with plots of individual conditional expectation. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 24, 44–65 (2015).

Duneier, M. Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the History of an Idea (Macmillan, 2016).

Massey, D. S. The age of extremes: concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography 33, 395–412 (1996).

Chetty, R., Dobbie, W., Goldman, B., Porter, S. R. & Yang, C. S. Changing opportunity: Sociological Mechanisms Underlying Growing Class Gaps and Shrinking Race Gaps in Economic Mobility no. w32697 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2024).

Jahani, E., Fraiberger, S. P., Bailey, M. & Eckles, D. Long ties, disruptive life events, and economic prosperity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2211062120 (2023).

Small, M. L. & Adler, L. The role of space in the formation of social ties. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 45, 111–132 (2019).

Ramani, A. & Bloom, N. The Donut Effect of COVID-19 on Cities (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021).

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. J. The Evolution of Work from Home (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023).

Santana, C. et al. COVID-19 is linked to changes in the time–space dimension of human mobility. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1729–1739 (2023).

Yabe, T., Bueno, B. G. B., Frank, M., Pentland, A. & Moro, E. Behavior-based dependency networks between places shape urban economic resilience. Nat. Hum. Behav. 9, 496–506 (2023).

Miyauchi, Y., Nakajima, K. & Redding, S. J. The Economics of Spatial Mobility: Theory and Evidence Using Smartphone Data (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021).

Oldenburg, R. in The Urban Design Reader (eds Carmona, M. & Tiesdell, S.) 285–295 (Routledge, 2013).

Schrager, A. The introverts have taken over the US economy. Bloomberg (22 January 2024).

Chen, M. K. & Rohla, R. The effect of partisanship and political advertising on close family ties. Science 360, 1020–1024 (2018).

Chang, S. et al. Mobility network models of COVID-19 explain inequities and inform reopening. Nature 589, 82–87 (2021).

Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 27, 93–115 (1995).

Hahsler, M., Piekenbrock, M. & Doran, D. dbscan: fast density-based clustering with R. J. Stat. Softw. 91, 1–30 (2019).

Breiman, L. Classification and Regression Trees (Routledge, 2017).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Techn. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

OpenStreetMap Carto/Symbols. OpenStreetMap Wiki https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/OpenStreetMap_Carto/Symbols (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our research group who contributed comments throughout the process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing, reviewing and editing; N.O.C and E.A.: supervision, reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cities thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–16.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Renninger, A., O’Clery, N. & Arcaute, E. US cities are defined by rings and pockets with limited socioeconomic mixing. Nat Cities 2, 1172–1182 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00350-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00350-7