Abstract

The timing of reproduction is causally linked to aging and mortality risk patterns in diverse species, but the existence of equivalent effects in humans is contentious. However, previous studies give little or no consideration to oral contraceptives as modifiers of reproductive timing and, therefore, potential disruptors of evolved trade-offs between reproduction and mortality. Here, we test the capacity for oral contraception and reproductive milestones to predict mortality and aging rate diversity. Using a large pre-registered study on 272,000 women from the UK Biobank, we reveal how oral contraceptive timing and reproductive milestones strongly predict mortality across the lifespan. These robust effects are independent of socioeconomic and health risk factors and, for oral contraceptive timing, act independent of other reproductive milestones. This study reveals complex relationships between reproduction and mortality and suggests an exciting potential for oral contraceptives to disrupt evolved trade-offs and lower intrinsic mortality risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organisms must balance energetic resources between maximising reproduction and enhancing survival. This constraint may lead to fundamental trade-offs between reproduction and mortality1,2,3,4,5,6, including a theoretical trade-off between energy allocated to reproduction and somatic investments to prevent aging or senescence5,6,7,8. There are several non-exclusive pathways through which such a trade-off may act, including broad theories on antagonistic pleiotropy that balance increased early-life fitness against lower late-life survival9,10, the reserve-capacity hypothesis where energetic resources are diverted from molecular anti-cancer mechanisms to increase early fitness4, the similar idea that early investment prevents the accumulation of ageing-linked somatic mutations11, and the more general disposable soma hypothesis whereby the prevention or repair of molecular damage (which could lead to accelerated ageing later on) requires taking away energy from reproductive effort12. Independent of the mechanism, however, these hypotheses share a testable premise: that energy allocated to the initiation of early-life reproductive effort trades off with later-life mortality patterns.

Such trade-offs have been supported in observations of wild, captive, and laboratory populations6,8,13,14 and by experiments on model organisms, where modifying the onset of reproduction causally changes the rate and onset of aging8,15. In human populations, however, the existence and scale of any such trade-off remains unresolved5,14,16,17. Interactions between mortality and fertility are unstable over time and across populations, and exhibit marked differences between natural- and controlled-fertility populations17. This complexity makes it difficult to disentangle effects and understand or capture prospective trade-offs.

However, one key requirement of the trade-off theory appears to have been overlooked. Any adaptive balancing of mortality with reproductive timing or effort must be driven by a physical mechanism, one triggered by reproductive milestones such as the first age at reproduction. Oral contraceptives, however, synthetically modify these reproductive pathways and hormonally mimic the early stages of pregnancy18: they both causally modify, and chemically mimic, key biochemical pathways activated during the immediate post-fertilisation stage of reproduction18. Oral contraceptives have, therefore, an unrecognised potential to disrupt any adaptive mechanisms responsible for balancing investments in reproduction and mortality.

This exciting potential to modify survival and aging, through the widespread and safe suite of oral contraceptive drugs, has been overlooked. Some evidence indicates contraceptive-induced disruptions of aging and mortality patterns. Aging rates may respond to oestradiol, a hormone linked to the initiation of reproduction19 and a primary agent in oral contraceptives. Oral contraception also modifies the timing of ageing-linked reproductive milestones such as menopause20,21. Finally, evidence from both clinical and cohort studies shows that oral contraceptive use is associated with substantial long-term protective effects20,22. The largest cohort studies, each involving more than 17,000 women, found that oral contraceptive use is associated with a 12–13% reduction in all-cause mortality20,22. Though these effects remain unexplained, they suggest a role for oral contraception in modifying aging patterns and mortality risk.

Including oral contraceptive use in the study of reproductive milestones therefore represents a considerable opportunity: to better test fundamental life-history theories of aging, and to explore a potential safe, inexpensive, and widespread clinical intervention to modify life-long mortality patterns.

Here, we test for a role of oral contraceptives and reproductive milestones—age at first birth, age at menarche, age at first sex, age at menopause, and total parity—in modifying mortality and aging using data on over 272,000 women, followed for 11 years to February 2020, from the UK Biobank23 (project #52621). In these data, aging rates are measured at the population level using the mortality rate doubling time, and at the individual level using the annual rate of change in key physical markers such as lung capacity. Our study of this population was designed, coded, and pre-registered before receiving the data (Supplementary Information) and reveals the striking capacity of reproductive milestones to predict life-long mortality patterns independent of socioeconomic or other drivers24. In addition, by removing previously hidden confounding by oral contraceptive use, our models highlight a potential yet unresolved role for oral contraceptive timing to persistently lower mortality across the lifespan in women.

Results

Cox proportional hazards models

The age at first oral contraceptive pill, and reproductive milestones of age at menarche, age at first sexual intercourse, age at first birth, age at menopause, and parity (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1), were central predictors of mortality in UK women. These factors had effect sizes comparable to or larger than other major influences on survival such as education and income levels (Table 1) and retained their predictive value for mortality up to five decades after expression.

Scatterplot matrix showing the relationship between the timing of reproductive milestones, and total parity (PAR), including complex interactions and a relatively large degree of orthogonality. The apparent lack of correlation between variables often masks complex interactions: for example, age at first oral contraceptive use (PILL) and age at first birth (AFB) rarely co-occur at the same age (diagonal is unshaded), while oral contraceptive use rarely precedes age at first sex by a wide margin (AFS; shown by rarity of points in top-left of scatterplot), yet age at first sexual intercourse (AFS) often coincides with either AFB or PILL despite these two variables being uncorrelated (p total parity (PAR). >0.05; R2 = 0.01). AAM is age at menarche, and AMEN is age at menopause.

This predictive accuracy was built on the long-term accurate recall of reproductive milestones. Individuals in the UK Biobank reported multiple responses to the same questions, separated by several years, allowing measurement of test-retest accuracy (Fig. 2a, c, d) and recall bias (Fig. 2b). Reproductive milestones were recalled accurately, ranging from the lowest recall accuracy for age at menopause (over-60s at baseline only; 43% identical from wave 1–2; mean absolute error or MAE 1.5 years) and the highest for total parity (99.2% identical from wave 1–2; MAE 0.014; test restricted to over-50s at baseline). There was no substantial indication of recall biases within individuals, with only one significant, but in our opinion not functionally meaningful, relationship between follow-up time and reported age at first oral contraceptive use which increased by 36 days per decade after baseline (Fig. 2b; r = 0.04; p = 0.002; N = 7941 repeat tests; Supplementary Code).

Self-report data, captured in successive waves for reproductive milestones revealed limited evidence for increases in error rates or age-dependent biases. For example, age at first oral contraceptive use (a AFC) was consistently reported within individuals despite an average 4.3-year gap between waves, with 52% of estimates identical across waves 1 and 2 (MAE 0.95 years; N = 7941 repeat measures). Recall accuracy remained approximately constant (b) but there was a small significant increase with age in reported AFC of 36 days per decade (ordinary least squares regression p = 0.002; N = 7941; Supplementary Code). Higher concordance and more accurate recall rates were observed for other variables such as c reported age at first birth (84% identical between wave 1–2; MAE 0.21 years; N = 5875 repeat measures) and d age at menarche (69% identical; MAE 0.38 years; N = 9979 repeat measures; Supplementary Code). Dashed pink lines indicate identical responses between waves.

Some 8116 certified deaths, classified under the International Classification of Disease ICD-10 codes (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42980), provided comprehensive age-specific mortality data across the follow-up period. Cox proportional hazards models were fit as preregistered (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/39U5R) to all deaths not classified as accidental or extrinsic (ICD-10 codes V00-Y99 inclusive; Supplementary Code), returning substantial and significant effects for outcome variables in all preregistered models.

Age at first birth was a significant predictor of post-reproductive mortality risk under the stratified Cox proportional hazards model (z-score −3.4; N = 182,034; p = 0.0007; Table 1 and Fig. 3a) and later ages at first birth predicted lower mortality risks, independent of income, education, the Townsend deprivation index, smoking, and alcohol consumption (Fig. 3a). This effect was independent of oral contraceptive patterns, with age at first birth retaining significance and a similar functional form when correcting for oral contraceptive use and timing (Supplementary Fig. 1). Age at first birth did not, however, retain significance (p > 0.05) when generating a comprehensive model to predict mortality risk for women with nonzero parity, fitting preregistered socioeconomic factors and age at first birth, age at menarche, total parity, age at first sexual intercourse, and age at first oral contraceptive use as fixed effects (N = 131,333; N = 3183 deaths; exploratory analysis; Supplementary Code; Supplementary Information). However, this non-significant result may have arisen from a loss of power when requiring nonzero parity, which halved sample size, and the expanded parameters of the model. Searching for effects in highly stratified models, even in such large samples, is constrained by the number of events25 and often suffers a rapid loss of power as multiplicative effects are added26.

Mortality risk predicted for population with fixed modal (factor) or median (numeric) socioeconomic values and risk factors revealed simple model coefficients, where mortality risk falls with increasing age at first birth (a) (N = 182,034; z-score −3.4; p = 0.0007), rises with later ages at first oral contraception (b) (N = 209,403; z-score 3.7; p = 0.0002), and falls with increasing age at menarche (c) (N = 260,524; z-score −5.0; p = 4.5 × 10−7). These model coefficients, however, appear to poorly approximate the functional form of these relationships. Correcting for social and economic risk factors only, then plotting predicted mortality risk against variation in target variables (x-axes; d–f; exploratory analysis; Supplementary Code) reveals more complex nonlinear interactions: with, for example, age at menarche (f) adopting a U-shaped mortality risk suggestive of stabilising selection. Supplementary x-axes indicate sample sizes, black lines indicate median predicted mortality risk.

Oral contraceptive timing was a major predictor of mortality risk under stratified Cox proportional hazards models (N = 209,403; z-score 3.7; p = 0.0002; Fig. 3b and Table 1). This predictive capacity persisted for decades after use. Models retained significance even after restricting analysis to individuals aged 60 and over at baseline (exploratory analysis; z-score = 2.24; p = 0.025; Supplementary Information), an average 39 years after starting and 30 years after ending oral contraception. After stratifying models for age at study enrollment—the age at baseline—the effect of oral contraceptive timing was the only variable that failed the z-test for proportional hazards at a local scale27 (p = 0.002; Supplementary Information). This shift in model coefficients—standardised to a comparable z-score using the Wald statistic—may reflect changes in dose, safety, or type of oral contraceptives taken in earlier life22,28,29 that could not be differentiated in the provided data, or non-exclusively by a nonlinear change in mortality risk that would be associated with a modification of ageing trade-offs.

Oral contraceptive timing retained predictive value for late-life mortality risk when included in a combined exploratory ‘all-in-one’ comprehensive model of reproductive milestones (z-score 3.2; p = 0.002) that added age at menarche, total parity, and age at first sex to the preregistered model structure (exploratory analysis; Supplementary Information; Table 1). Of these milestones, only age at first sex was not a significant predictor of mortality risk (Table 1). Associations with oral contraceptive timing did not, therefore, seem to act as a proxy for the overall rate of reproductive development: oral contraceptive timing retains predictive value in composite models and has negative model coefficients that contrast with the positive model coefficients reproductive milestones (Supplementary Information).

In contrast, the last age at oral contraceptives use was not a significant predictor of mortality (p = 0.07; N = 188,160; Supplementary Information) despite capturing oral contraceptive use much closer to the study date. Likewise, the estimated maximum lifetime dose of oral contraceptives, approximated using the difference between first and last oral contraceptives use for women with completed fertility schedules, also failed to predict subsequent mortality risk (Cox proportional hazards model; N = 178,995 women aged over age 50 at baseline; p = 0.61; Supplementary Information). These findings support the preregistered hypothesis where the timing of oral contraceptives, rather than the estimated maximum lifetime dose or the most recent dose, are a driver of mortality risk differentials.

As preregistered, age at menarche and age at menopause were both tested as predictors of mortality using Cox proportional hazards models. Both models indicated that later onset of these reproductive milestones was linked to highly significant increases in mortality risk (z-scores of −5.0 and −5.7 respectively; p < 1 × 10−6; Table 1; Supplementary Information): each 1-year increase in the age menarche was associated with an approximately 3.5% increase in all-cause mortality risk, while a single year increase in age at menopause predicted a 1.4% increase in all-cause mortality. These are notable effect sizes in the context of public health: these per-year effect sizes are comparable, for example, to the increased mortality risk of seasonal influenza epidemics30. As with oral contraceptive timing, however, these simple linear coefficients masked nonlinear residuals indicative of more complex interactions (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

Nonlinear functional forms were explored by removing target variables from each preregistered model and plotting mortality risk of these ‘socioeconomic-only’ mortality models against variation in target variables (Fig. 3d–f; exploratory analysis; Supplementary Code). Aligning with the ‘trade-off’ hypothesis, later ages at first birth were associated with lower relative mortality risk (Fig. 3a). More complex nonlinear interactions were evident in other data. The timing of oral contraception approximated the effect of age at first birth but had a more U-shaped effect on predicted mortality risk (Fig. 3b), while early or late ages at menarche were associated with elevations in predicted mortality risk (Fig. 3c): a strongly U-shaped pattern. A similar U-shaped pattern was observed for age at menopause (Supplementary Fig. 2) but this model warranted some caution given the substantially smaller sample sizes, incomplete reporting of menopause at baseline, and less reliable recall accuracy.

Age at menarche had the greatest predictive power for all models that included it as a covariate, independent of later reproductive milestones (Fig. 4d and Table 1; Supplementary Information), with greater predictive power for late-life mortality than age at menopause, age at first birth, oral contraceptive use, and even total parity, which all displayed independent predictive effects when included in the same model (Table 1; Supplementary Information).

After exact matching on age at baseline, and nearest-neighbour matching for control variables, paired cohorts revealed complex differences in mortality patterns. An early (below median or <21 years) versus late age at first oral contraception (a) was not associated with significant age-dependent mortality differences after correcting for multiple testing and interactive effects (uncorrected p = 0.02; Benjamini–Hochberg corrected p > 0.05), or in total mortality (two-sample test for equality of proportions; X-squared = 2.95; p = 0.09). In contrast, the use of oral contraception (b) (two-sample test p = 0.02), an above-median age at first birth (c) (‘early’ cohort is <25 years; two-sample test p = 0.002) and an above-median age at menarche (d) (‘early’ cohort is <14 years; two-sample test p = 0.002) were all associated with lower mortality risk across almost all post-reproductive ages. Sample sizes per matched cohort are shown on top x-axis, odds ratios for mortality (ORs) are shown in pink, and points are labelled with the number of deaths occurring in each cohort and age category.

Propensity matched cohort models

The mortality risk differentials associated with oral contraception use, early births, and differential age at menarche were substantial. However, mortality risk is not a product of aging rate variation—measured by the mortality rate doubling time—alone. Overall mortality patterns are a composite of complex age-dependent and age-independent components—in other words, mortality rates indicate how bad things are, while aging rates and mortality rate doubling times indicate how fast they become worse. It was not clear, therefore, if mortality differentials observed under these models were a result of aging rate differentials, overall age-independent changes in mortality risk, or both.

To explore this possibility, mortality rate doubling times (indicative of actuarial aging rates31,32) were measured using both a preregistered analysis of cross-sectional data (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3), and an additional exploratory analysis to measure longitudinal on-study mortality accelerations during follow-up (Supplementary Fig. 4).

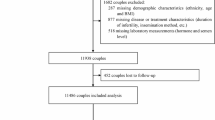

As preregistered, large propensity-matched cohorts were generated which differed only by variation in the target variable: age at first oral contraceptive use (above or below median; N = 50,604 per cohort; and lowest- versus last-three quartiles; N = 49,147 per cohort; Supplementary Table 2), ever- versus never-users of oral contraceptives (N = 50,181 per cohort), age at first birth (above or below median; N = 60,190 per cohort), or age at menarche (above or below median; N = 95,315 per cohort). Each paired cohort was matched exactly by age at baseline and matched by nearest-neighbour joining for education, income, the Townsend deprivation index, smoking rates, and alcohol intakes (logit distance with caliper of 0.05; Supplementary Information) ensuring identical age structure and socioeconomic factors for each paired cohort33.

The mortality rate doubling times of these matched cohorts accelerated at similar rates, when assessed in cross-sectional data, failing to reach significance (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Information) with one marginal exception (Fig. 4d) that disappeared when correcting for multiple testing. When hazard rates were calculated annually, individuals who took oral contraception underwent slower aging than the matched cohort when aging was measured by mortality rate doubling times (F-value 4.47; p = 0.04; Supplementary Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 2). In addition to losing significance under the Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple testing (p > 0.05), this effect also lost significance (p = 0.09) when binning the same data into 5-year categories and re-fitting the model (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 2), highlighting the intended purpose of preregistering both annual and quinquennial bins. This outcome should be considered a non-result.

We made an exploratory attempt to circumvent these issues by comparing the mortality rate doubling times in matched cohorts observed during the extensive 11-year follow-up time in the UK biobank to Jan 2020. These within-study mortality rate doubling times revealed complex outputs and were complicated by ascertainment biases in survival patterns (Supplementary Fig. 4). The observed acceleration of mortality rates with age were unexpectedly low and deviated strongly from a log-linear pattern over the first 2 years of observation (Supplementary Fig. 4a, c, e, g), suggesting substantial ‘healthy volunteer’ ascertainment biases. After removing this bias, by calculating mortality acceleration rates after 2 years on-study (Fig. 4a, c, e, g) or by measuring differences in residual mortality between cohorts (Fig. 4b, d, f, h), the timing of oral contraception (trimmed data p = 0.02; residual regression p = 0.003; Supplementary Fig. 4a, b) and the use of oral contraception (trimmed data p > 0.05; regression of residuals p = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 4c, d) gained marginal significance. These results contrasted with cross-sectional data, which indicated the opposite trends in mortality rate doubling times (Supplementary Fig. 3a), only one of p values survived correction for multiple testing (Supplementary Fig. 4b), and the results were again considered non-informative.

As such, it remains unclear if significant mortality risk differentials, observed for women who reached reproductive thresholds or used oral contraceptives at different ages, are associated with differences in the underlying rate of aging. Observed changes in mortality between cohorts may be due to differential aging, constant advantages in frailty or age-independent mortality rates, or some combination of both effects.

Cohort-based data generally supported the mortality differentials uncovered in greater detail by the Cox proportional hazards models. However, these models were limited in their ability to untangle mortality patterns, as they were restricted to binary comparisons of two cohorts and therefore cannot capture nonlinear trends as observed in Fig. 4. In paired cohorts with identical age distributions, incomes, education, Townsend deprivation indices, smoking rates, and alcohol intake, a simple nonparametric two-sample proportion test34 (exploratory analysis; Supplementary Code) indicated significantly lower mortality risk in oral contraceptive users (X-squared 5.58; p = 0.02), individuals with an above-median age at first birth (median 25 years; X-squared 9.68; p = 0.002) or age at menarche (median 14 years; X-squared 9.37; p = 0.002). No significant difference in mortality for individuals with above/below median ages at first oral contraceptive use were apparent (median 21 years; X-squared 2.95; p = 0.09; Supplementary Table 2) likely as a combined result of the requirement of a binary comparison between cohorts, and the partially U-shaped distribution of mortality risk associated with oral contraceptive timing (Fig. 3b).

Improvements in all-cause mortality overwhelmed any potential mortality costs associated with the established clinical side effects of oral contraception. In our large matched cohorts, oral contraception use was not associated with a significant elevation in mortality risk in thrombosis and pulmonary embolisms28 (18 deaths in users, 16 in non-users), breast cancer28,35,36 (194 deaths in users, 180 in non-users), cervical cancer28,35 (<10 deaths per cohort), or cardiovascular disease deaths (ICD-10 codes I20-I25; 111 deaths in users, 139 in non-users; exploratory analysis; N = 100,362; p > 0.05 in all comparisons; Supplementary Code): diseases with prior evidence for elevated mortality risks during oral contraceptive use. These outcomes should be treated as an absence of evidence, not a strong non-result, as we had low power to detect mortality differentials in matched cohorts and comparisons of matched cohorts are restricted to simple pairwise comparisons and the observation period was usually long after active use of contraceptives. Our results therefore support previous findings that the costs of oral contraceptive use, while forming a clear clinical risk, are more than offset by observed benefits22,28,29.

Again, it was unclear if the observed, highly significant mortality differences between cohorts were driven by fixed age-independent changes in mortality risk across all ages, changes in mortality rate doubling times (indicating differential aging), or both. The most we could say was that there was no evidence to support differential aging rates between matched cohorts, although power to detect such effects was low.

Linear models for proxy measures of physiological aging

This problem was not clarified by our preregistered analysis of physical indicators of aging: forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), average left + right hand grip strength (HGS), and self-reported health (SRH). With the Cox models and matched cohort analyses, preregistered linear models returned overwhelmingly significant results of large effect size. Under our preregistered models (Supplementary Code), oral contraceptive use and timing, and age at first birth were highly significant predictors of FEV1, HGS, and SRH. However, this linear modelling section of the pre-registered study was removed. Surprisingly, our preregistered indicators of physiological aging seemed to have no clear value for informing aging rates in the UK Biobank.

Exogenous indicators of aging should, obviously, share aging as a latent cause, and therefore display some covariance within individuals. Within individuals measured within a single wave, these measures were repeatable and concordant: left and right hand-grip strength were highly correlated (r = 0.80; N = 270,257; p < 2.2 × 10−16), despite variance caused by hand-dominance, as were consecutive tests of FEV1 (r = 0.93; N = 247,857; p < 2.2 × 10−16). When tested across waves, however, none of our putative indicators of aging displayed any meaningful covariance structure (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d; exploratory analysis; Supplementary Code). The rate at which our selected aging indicators decayed with age was either orthogonal or scarcely correlated across measures (Supplementary Fig. 5). While FEV1 and HGS both decayed with age, the rate at which they decayed with age was at best very weakly correlated within individuals (r = 0.1; N = 26,226; Supplementary Fig. 5d). That is, despite these metrics being correlated with each other cross-sectionally (r = 0.36; N = 246,377; p < 2.2 × 10−16), and despite substantial sample sizes and long follow-up periods, the rate at which aerobic capacity and physical strength declined with age was not meaningfully related. One of the selected indicators, SRH, did not even decay longitudinally with age (Supplementary Fig. 5c) and, unsurprisingly, rates of change in SRH were therefore not meaningfully correlated with longitudinal changes in HGS (r = 0.07; N = 30,282; p < 2.2 × 10−16) or FEV1 (r = 0.05; N = 26,327; p = 3 × 10−14). In the few hundred individuals attending all four waves, the rate of decline in HGS and FEV1 measured between waves 1 and 2 was not even correlated with later rates of physical decline, measured between waves 3 and 4, in the same person (p > 0.05; N = 579 and 453 respectively; see Glindmeyer et al. for a related finding37; Supplementary Code).

It was therefore difficult to understand why these physical indicators should be near-orthogonal or uncorrelated within the same individual, if they shared aging as a latent cause of any discernible value. This unexpected result raised fundamental questions on the capacity of these variables to capture latent variation in aging rates in the UK Biobank data, and the preregistered analysis of these indicators was dropped.

Discussion

Oral contraceptive timing and the timing of major life-history events linked to reproduction have a long-term predictive capacity for mortality risk. These findings support our original hypothesis that the timing of widely available and safe hormonal drugs, oral contraceptives, may be lowering all-cause mortality in women: either through the modification mortality risk at all ages (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b) or, possibly, by modifying aging rates and mortality rate doubling times through the synthetic modification of adaptive pathways (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). More broadly, the substantial predictive value of early-life reproductive milestones for late-life survival aligns with the still-contested38 existence of mortality-fertility trade-offs in humans. Later ages at first reproduction are linked to lower mortality risk, an effect that persists for decades24, and which clearly supports hypothesised evolutionary trade-offs between longevity and reproduction14,39.

Prominent and surprising amongst these results, however, is the larger predictive capacity of age at menarche when compared using the Wald statistic z-score (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Code). Age at menarche was highly accurately recalled (Fig. 2) and exhibited larger effect sizes than age at first birth (Supplementary Information; Fig. 3). While the importance of age at menarche for predicting some aspects of aging is known40, the size and persistence of these predictive effects on survival is notable. Inversely, the absence of predictive power for age at first sex, which fell to zero once age at menarche or other reproductive milestones were included in mortality models (Supplementary Information) suggests, but of course does not demonstrate, that this variable is not causal for mortality variation.

A possibility raised here is that observed trade-offs between mortality and reproductive timing occur without changes in the aging rate. This seems counter-intuitive, but a trade-off between reproduction and longevity17 may occur with or without any transient or permanent modification of aging rates (Supplementary Fig. 6). For example, reproductive timing can modify mortality risk by a constant factor at all ages (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), lowering average lifespan and inducing a trade-off between reproduction and longevity17 without affecting the rate of aging or mortality rate doubling times (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). This frailty-risk modification need not involve a long-term accumulation of somatic damage4,17 but may arise through diverse mechanisms, such as a fixed day-to-day reallocation of energetic resources. Alternately, earlier ages at reproduction or menarche may redirect energetic resources away from growth and development, raising lifelong mortality risks without incurring later-life energetic costs41.

Although we had limited power to detect aging rate differentials, pairwise comparisons of matched cohorts with above-below median ages at first birth revealed conflicting but generally non-significant evidence for changes in the ageing rate (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4e). The highly significant gains in survival associated with later reproduction (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1) may be driven by constant proportional changes in mortality risk at all ages, supporting a ‘fixed-cost’ explanation (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), or may involve changes in aging rates that remain difficult to detect with current statistical tools and available data. At present the question remains unresolved.

However, the first recourse for explaining human health should be social rather than evolutionary. Our pre-registered code to navigate the ‘garden of forking paths’, a metaphor for the nested series of analytical choices facing researchers that may affect study outcomes, should increase confidence that these results are not driven by researcher degrees of freedom or researcher choices (https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-statistical-crisis-in-science). Yet confidence in the significance of results, and the validity of observed effects, does not imply an equivalent accuracy when interpretating the cause of such results. Even after our best efforts to correct for socioeconomic predictors, there are a diverse range of possible social or non-adaptive explanations linking higher mortality with earlier reproduction or other reproductive milestones. As such, our results require extraordinary caution and critical thought.

Our own analyses provide one example: a substantial and statistically significant line of inquiry was removed mid-analysis, for reasons that were not initially or intuitively obvious. Ages at first birth and oral contraceptive use predicted cross-sectional variation in physical strength, self-reported health, and respiratory capacity: nominally a strong result supporting an evolutionary hypothesis, with large effect sizes and small p values (Supplementary Information). Yet these variables do not share latent variation (Supplementary Fig. 5d), do not exhibit stable autocorrelation or have stable longitudinal rates of change (Supplementary Fig. 5b), do not consistently degrade over time (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c), and therefore cannot be relied on to inform individual variation in the rate of aging. Taking these results at face value would have constituted a serious mistake.

Additional caveats apply. Our analysis corrects for variables that may occupy socially mediated causal pathways from reproductive patterns to mortality. The potential importance of such social-environmental pathways should not be ignored. For example, it is likely that use of oral contraceptives causally modifies education and income levels42,43, independent of total parity42,44, by allowing greater control over reproductive timing. In turn income and education levels can modify longevity45, forming a socially mediated causal pathway from oral contraception to late-life mortality. Another hypothesis may be that avoiding early reproduction through oral contraceptive use may lower later-life mortality: this seems plausible but is difficult to reconcile with the persistent predictive value of oral contraceptive timing in models that correct for parity and age at first birth. Social and environmental effects linked to reproductive development or contraception20,22 have the potential to dwarf putative effects acting through purely adaptive mechanisms, a possibility that requires careful consideration.

It would be a serious error to use these findings, in isolation, as a guideline for oral contraceptive use or reproductive policy. An obvious shortfall is that biobank data do not allow discrimination between types or doses of oral contraceptive—which have diversified markedly since the ascertained 40–60-year-old cohorts first started oral contraceptives—and do not allow capture of non-oral hormonal contraceptives. When considering social context, however, these results reinforce the strongly positive role for oral contraception in women’s survival20,22 and align with the extraordinary social benefits of early access to contraceptive choices42,43,44. Access to and use of all types of oral contraceptives is associated with life-long survival benefits after correcting a range of core socioeconomic and reproductive variables (Supplementary Table 1). These benefits are not offset by any detectable increase in pulmonary embolism deaths, or any other common complications of oral contraceptive use (Supplementary Information). These results can, therefore, be seen as a reinforcement of the substantial social benefits already linked to oral contraceptive access42,43,44.

The benefits of oral contraception seem to have dual effect: controlling or delaying pregnancy and thereby avoiding the mortality costs of early-life reproduction, and a secondary effect of oral contraceptive access associated with lower all-cause mortality independent of parity and reproductive timing. The net mortality benefit of oral contraceptive use detected here is also independent of major socioeconomic factors (Supplementary Fig. 1), age at first birth, and total parity (Table 1). However, there are more subtle nonlinear trends in the data that may mitigate this net reduction in mortality risk. Early use of oral contraception, before age 16, may have a reduced mortality benefit (Fig. 3a) an effect that may or may not result from the modification of evolved mechanisms that rebalance mortality and survival. This possibility is exciting as it would involve the synthetic modification of evolved pathways, observed in other species8, to modify life-long mortality outcomes.

Once the effects of oral contraception are corrected, strong interactions between age at first birth and late-life mortality emerge. Surprisingly, age at first birth effects may play a smaller role than the timing of other reproductive milestones. The substantial predictive effects of age at menarche, an earlier reproductive milestone of larger effect size than age at first birth (Table 1), highlight the potential of such early-life milestones in shaping late-life mortality, acting as markers or even regulators of later-life aging patterns.

Understanding such potential trade-offs may open the door to simple interventions that lower life-long mortality risk in women and lead to a better understanding of human aging. In particular, the prospect of a carefully timed hormonal intervention that modifies all-cause mortality for four consecutive decades, oral contraception, should be taken seriously. Unlike many other proposed clinical interventions, oral contraceptive interventions have some basis in biological theory14,16 and are already linked to lowered all-cause mortality20,22, reduced ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancer risks28,46,47,48, and diverse other health benefits22 long after the termination of actual drug use.

The associations detected in this study support potential trade-off between reproductive timing and longevity, modified by early access to oral contraception. Whether this trade-off is primarily evolutionarily adaptive in nature, a trade-off for resources dominantly shaped by current social, cultural, or environmental constraints, deserves intensive investigation. Adaptive causal mechanisms, ones that have not been dramatically modified by modern contexts, should remain observable in cross-cultural samples across diverse populations and biobanks. Cross-cultural studies of this association are an obvious primary target for further analysis. In addition, if these effects act through the modification of deeply conserved biochemical pathways1,6, the synthetic modification of evolved adaptive trade-offs using contraceptives would be testable using model organisms in laboratory settings.

Regardless of the cause of lower mortality, however, the positive associations with survival detected here reinforce this general view and point to the widespread life-long benefits of oral contraception access. How these additional benefits act, through biology or social pathways or some mix of both, requires further intensive research.

Methods

Data were analysed as preregistered with no or very limited modifications. Unless otherwise noted all models were preregistered with the open science framework on the 22 May 2019; including writing exact model specifications in R code and before obtaining access to the UK biobank data (OSF study https://osf.io/39u5r; https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/39U5R). A copy of the preregistration is embedded in the supplementary information. The study was in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the UK Biobank review (approved application reference number 52621), and the ANU Human Research Ethics Committee (IRB EC00104). Deviations from the preregistered protocol and methods, and quality controls not pre-registered, are detailed below. All data analysis was performed in R version49 4.0.5 (Supplementary Code).

Data and quality control

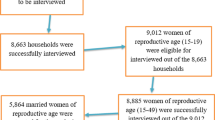

Data for 369 variables across 502,520 individuals were obtained from the UK Biobank23 (accessed 4 Nov 2019). Data were filtered to remove individuals lost to follow-up (N = 1298; 0.26%) and self-reported males (N = 228,521), resulting in a sample of 272,701 people. Of these, 99.5% (N = 271,293) reported either Yes (81% of respondents) or No to ever taking oral contraception at baseline (initial study enrollment), with 96% (N = 211,715) of “Yes” respondents reported an age at first oral contraception at baseline, and 68% of all women (N = 184,189) reported an age at first live birth at baseline. Ages and ICD-10 coded causes of death (N = 20,442 total and N = 8116 female deaths), and ages at first incident cancer diagnosis (N = 89,661 total and N = 51,235 female cases), were continuously updated to February 2018 (Supplementary Table 1). Individuals who had opted out between preregistration and the analysis date were excluded.

Individuals classified as dying from extrinsic causes of death under the tenth International Classification of Disease or ICD-10 codes (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42980) V00-Y99 “External causes of morbidity” (n = 222; 2.7%), including the highest frequency cause of death codes of unspecified falls (W19 codes; 29 deaths) and intentional self-harm by hanging and suffocation (X70 codes; 36 deaths), were removed prior to mortality and survival analyses, as these deaths are nominally independent of intrinsic ageing patterns. Codes for sequelae of extrinsic causes should have been included in preregistration but did not cause any deaths. While a single obstetric-related death was included in analysis (ICD-10 code O300), an outcome causally affected by oral contraceptive use, inclusion or exclusion of this death did not modify any primary or secondary outcome.

Predictor variables in each model were subjected to list-wise deletion50. This method was preregistered as it is less susceptible to biases introduced by data missingness50,51,52 and hidden researcher degrees of freedom53 than multiple imputation. Data loss to list-wise deletion left sizeable samples for statistical inference, typically in excess of 100,000 people (Table 1 and Supplementary Information).

Qualification levels in the UK Biobank were dummy-coded as an ordered factor with an irregular ordering such that responding to education status with “None of the above” was coded as greater than individuals holding a degree, which in turn was greater than individuals with GCSEs. This ordering was modified to reflect the length of time required to attain each level of education, with “None of the above” as the reference in the dummy-coding (Supplementary Information). Likewise, the default dummy-coding for alcohol intake places non-respondents to alcohol above daily drinkers, and all lower-consumption categories, in ordinal rankings. In contrast, factor levels used for smoking place non-respondents below never-smokers. As such, alcohol intake was recoded to match smoking status, with non-respondents as NA values. Smoking and alcohol consumption was re-coded with zero consumption as the reference, then increasing levels of consumption, followed by non-respondents (Supplementary Information).

We trimmed outliers in FEV1, removing the top 0.01% of FEV1 measures (N = 1395 measurements above 5.6 L) and all FEV1 values that fell below 0.2 L (N = 7188; 0.51% of 1,413,288 total FEV1 measurements). Most values outside these cut-offs appeared to be data entry errors rather than genuine FEV1 capacities: for example, individuals falling below a 0.2 L threshold reported more typical FEV1 averages, around 2.2 L, in their next measurement during the same wave.

Linear models

Cross-sectional prediction models were constructed using simple least squares regression in R. As preregistered, nested linear models—in which a core predictive model detailed below is evaluated using an analysis of variance after the addition of a single additional variable fit as a fixed effect—were used to predict variation at baseline in three proxy measures for physiological ageing in the UK biobank cohorts: averaged left- and right-hand grip strength (HGS; UK Biobank variables #46 and #47), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1; best of three performances; variable #3063), and self-reported overall health rating (SRH; variable #2178). These cross-sectional variables were then measured between the first and last reported values in any wave, corrected to annualised (365 day) rates of change by dividing by the time elapsed between measurement waves, and the models re-run to predict these annualised rates of decay or improvement.

All nested linear models were fit with interactive effects between date of birth (pooled by month), to control for cohort effects37 such as the unexplained decline of FEV1 over time in equal-height adults, followed in order by household income (HHI; variable #3063), qualification level (QUAL; variable #3063) and the Townsend Deprivation Index (TDI; variable #3063). Smoking frequency (SMK; variable #3063) and alcohol intake (ALC; variable #3063) were then fit as fixed effects. Each of the predictor variables of interest were then added to this core linear model in a nested model framework: these were respectively age at first oral contraceptive (AFC; variable #3063), ever taken oral contraceptives (ETO; variable #3063), and age at first live birth (AFB; variable #3063). An analysis of variance was performed on each nested model, with the core model as baseline, and corrected residuals examined (see ‘linear model results’; Supplementary Information).

As an initial quality control, covariance between these putative aging rate indicators was measured using Pearson’s correlation coefficient r and plotted in bivariate scatterplots. These exploratory ‘sanity checks’ revealed problematic patterns. There was little or no concordance between metrics and the r values did not exceed 0.1, indicating an extremely limited covariance structure, so we further tested rates of change calculated between waves 1–2 and compared them to rates of change in the same individual between waves 3–4 for all three variables. As these variables were selected on the assumption that they shared aging as a latent cause, and that their longitudinal rate of decay would therefore capture aging rate diversity, this limited covariance raised serious questions and further analysis was dropped. A full preregistered analysis is marked ‘linear model results’ in the Supplementary Information.

Cox proportional hazards models

Cox proportional hazards models54,55 were initially implemented exactly as preregistered using the “survival” package56 version 3.2-10 in R (see Supplementary Information). Right-censored survival models were fit with a shared structure of core predictors: age at baseline (when the first measurements were taken) in 5-year age categories, household income, qualifications (highest attained education; coded as UK rankings or EU equivalents), the Townsend Deprivation Index, smoking status, and alcohol intake were all fit as independent effects. Target variables such as oral contraceptive timing, or combined models that included multiple fixed or interactive effects, were added to this model structure in a nested fashion to evaluate the independent or collective contribution of reproductive milestones and patterns to mortality prediction. However, when evaluating our preregistered models, all models initially failed the Cox z-proportionality test27,57, with age at baseline being the largest contributor to failing the proportionality test in each model27 (Supplementary Information). This accumulation of non-proportional hazards was unsurprising in retrospect, given the extraordinary 2–6-decade gap from reproductive milestones to study enrollment and the 11-year average observation period.

Rather than ignore non-proportionality and publish the results exactly as preregistered, leading to p values below 10−16 but a potentially incorrect model specification, we employed a minor adjustment of stratifying models by age at baseline, instead of treating age at baseline as a fixed effect. This routine change resolved non-proportionality in all models, with the partial exception of the oral contraceptive timing model (Supplementary Information), which failed the proportionality test for the oral contraceptive timing variable (p = 0.002) but passed the omnibus Cox z-test (p = 0.06) and was therefore included in analysis. Non-proportionality in a single variable is common in Cox models and often indicates that the effect of a predictor variable may be changing over time.

Stratifying for age at baseline, rather than treating it as a fixed effect, imparted a very minimal change to model structure and eliminated the global non-proportionality problem in all models (see ‘Model structure and summaries’ in the Supplementary Information).

To test the capacity of the oral contraceptive model to predict mortality effects in later life, especially above the terminal ages at which women no longer give birth or use contraception, we developed models that were structured identically to the preregistered oral contraceptive model but used them to predict mortality occurring exclusively above a given age cut-off (Supplementary Information).

To examine the collective effects of reproductive milestones on mortality, two exploratory Cox proportional hazards models were fit for women with a completed fertility schedule, defined as all women older than age 50 at baseline, including a broad range of reproductive development milestones (Table 1 and Supplementary Information). These models were restricted to adding pre-registered target variables as fixed effects to the pre-registered core model, to avoid inflating potential researcher degrees of freedom. Inclusion of age at first birth in the first ‘all-in-one’ combined model obviously restricted analyses and conclusions to women with nonzero parity (see ‘Exploratory Cox models’ Supplementary Information). This model initially returned anomalous coefficients derived from the 189 individuals who did not report alcohol consumption rates: the model was re-run with these individuals removed, returning near-identical results (Supplementary Information). A second, more comprehensive combined model was trained, with the same baseline structure, on data that excluded age at first birth but retained parity, including zero parity, as a predictor (reported in Table 1; Supplementary Information). A third combined model that included age at menopause was explored but led to a dramatic reduction in sample size and power: the model retained only 28% of the original sample and 30% of observed deaths after list-wise deletion (reported in Supplementary Information).

To further interrogate these models for potential nonlinear effects in the treatment variables, such as age at first birth, Cox proportional hazards models were re-fit to the same data with treatment variables removed and otherwise identical model structures. The distribution of model-corrected residuals from these null models, in the form of predicted mortality risks, were then plotted against variation in the treatment variable to visualise the underlying distribution (Fig. 3d–f and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2b) being approximated by linear coefficients in the Cox models (Fig. 3a–c; Supplementary Fig. 2a; Table 1).

Propensity-matched cohorts

Matched cohorts were constructed using nonparametric neighbour-joining matching algorithm in ‘MatchIt’ version33 4.2.0, fit with a caliper of 0.05, exact matching for year of birth, and nearest-neighbour joining33,58 for all other variables: age at baseline, household income, education level, the Townsend deprivation index, and alcohol and smoking status (Supplementary Information).

Preregistration of methods for propensity matching was, due to human error, insufficiently clear when describing the model structure (preregistration lines 200-205) and implied comparisons that were unachievable using pairwise cohort matching. Fortunately, however, the pre-registered code referring to the same analysis were clear in defining how the pairwise matching would be structured (preregistration lines 205-230) and was followed rigorously.

Life tables were constructed as preregistered using the ‘fmsb’ package59 version 0.7.1 for cross-sectional data, using annual and quinquennial bins. Mortality rate doubling times were then calculated from the coefficients of a weighted log-linear model fit to age-specific mortality rates, with age and cohort membership fit as interactive effects, such that any significant age-by-cohort interaction effect detect differential slope coefficients (indicative of differential rates of mortality acceleration between cohorts) under an analysis of variance. Samples were weighted by the population exposed to mortality risk, from baseline (Supplementary Information). Matching populations with the earliest quartile or decile for age at menarche, age at menopause, or age at first birth did not result in a sufficient number of observed deaths to construct accurate life tables. The quality control threshold for 1000 minimum observed deaths in a cohort was, however, met for pairwise comparisons of ever versus never users of oral contraception; above vs. below median age at first birth, age at menarche, and age at first oral contraception; and first- versus later-quartiles of age at first contraception (Supplementary Information).

As propensity-matched cohorts only captured cross-sectional mortality risks, an exploratory analysis was performed on matched cohorts to compare mortality rate doubling times during the pre-pandemic UK biobank follow-up period (to 31/01/2020). Again, this exploratory analysis was performed using pre-registered models and data to reduce potential researcher degrees of freedom. Exact matching for cohorts on age at baseline meant that, despite having mixed age structures, paired cohorts had identical exposures to mortality risk from baseline (Supplementary Information). As such, we employed an approach of using synthetically matched cohorts60, made to have identical age structures, to compare rates of aging in mixed cohorts.

Age-specific mortality risks were calculated in 30-day months from baseline to 150 months post-enrollment, and initially fit using an identical linear modelling approach to the cross-sectional cohort matching analysis. To avoid clear deformation of mortality risks during the first 2 years on-study, likely caused by healthy recruitment biases, this analysis was first run after trimming data at 24 months (Supplementary Fig. 4a, c, e, g). In addition, we fit a least squares linear regression to the residual gap between mortality rates in both cohorts for the entire 150-month follow-up period under the untested assumption that any ascertainment biases would be equivalent between cohorts and that, therefore, progressive age-dependent changes in relative mortality risks would be the result differences in mortality rate acceleration (Supplementary Fig. 4b, d, f, h).

Data availability

Data in this study are available upon reasonable request and with permission, upon application, from the UK Biobank. All stable, unique variable identifiers of the UK Biobank data used in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and reproducible code. All code is available in the supplementary information, from the github repository http://github.com/SaulNewman/OC_study and on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

All code is available in the Supplementary Information, from the github repository https://github.com/SaulNewman/OC_study and on request from the corresponding author.

References

Blomquist, G. E. Trade-off between age of first reproduction and survival in a female primate. Biol. Lett. 3, 339–342 (2009).

Dudycha, J. L. & Tessier, A. J. Natural genetic variation of life span, reproduction, and juvenile growth in Daphnia. Evolution 53, 1744–1756 (1999).

Abrams, P. Does increased mortality favor the evolution of more rapid senescence?. Evolution 47, 877–887 (1993).

Weinstein, B. S. & Ciszek, D. The reserve-capacity hypothesis: evolutionary origins and modern implications of the trade-off between tumor-suppression and tissue-repair. Exp. Gerontol. 37, 615–627 (2002).

Westendorp, R. G. J. & Kirkwood, T. B. L. Human longevity at the cost of reproductive success. Nature 6713, 743–746 (1998).

Lemaître, J. F. et al. Early-late life trade-offs and the evolution of ageing in the wild. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 282, 1–10 (2015).

Stearns, S. Trade-offs in life-history evolution. Funct. Ecol. 3, 259–268 (1989).

Stearns, S. C., Ackermann, M., Doebeli, M. & Kaiser, M. Experimental evolution of aging, growth, and reproduction in fruitflies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 3309–3313 (2000).

Williams, G. C. Pleiotropy, natural selection and the evolution of senescence. Evolution 11, 398–411 (1957).

Austad, S. N. & Hoffman, J. M. Is antagonistic pleiotropy ubiquitous in aging biology?. Evol. Med. Public Health 2018, 287–294 (2018).

Antonio Rodríguez, J. et al. Antagonistic pleiotropy and mutation accumulation influence human senescence and disease. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 55 (2017).

Abrams, P. A. & Ludwig, D. Optimality theory, Gompertz’ law, and the disposable soma theory of senescence. Evolution 49, 1055 (1995).

Tatar, M. & Carey, J. R. Nutrition mediates reproductive trade-offs with age-specific mortality in the beetle Callosobruchus maculatus. Ecology 76, 2066–2073 (1995).

Thomas, F., Teriokhin, A. T., Renaud, F., De Meeûs, T. & Guégan, J. F. Human longevity at the cost of reproductive success: evidence from global data. J. Evol. Biol 13, 409–414 (2000).

Luckinbill, L., Arking, R., Clare, M., Cirocco, W. & Buck, S. Selection for delayed senescence in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 38, 996–1003 (1984).

Mace, R. Evolutionary ecology of human life history. Anim. Behav. 59, 1–10 (2000).

Le Bourg, É Does reproduction decrease longevity in human beings?. Ageing Res. Rev. 6, 141–149 (2007).

Berg, E. G. The chemistry of the pill. ACS Cent. Sci. 1, 5 (2015).

Whitten, P. L. & Turner, T. R. Endocrine mechanisms of primate life history trade-offs: growth and reproductive maturation in vervet monkeys. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 21, 754–761, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20939 (2009).

Vessey, M., Yeates, D. & Flynn, S. Factors affecting mortality in a large cohort study with special reference to oral contraceptive use. Contraception 82, 221–229 (2010).

Gold, E. B. et al. Factors related to age at natural menopause: Longitudinal analyses from SWAN. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1, 70–83 (2013).

Hannaford, P. C. et al. Mortality among contraceptive pill users: cohort evidence from Royal College of general practitioners’ oral contraception study. BMJ 340, 927 (2010).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 3, e1001779 (2015).

Mills, M. C. et al. Identification of 371 genetic variants for age at first sex and birth linked to externalising behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1717–1730 (2021).

Schoenfeld, D. A. Sample-size formula for the proportional-hazards regression model. Biometrics 39, 499 (1983).

Berrington De González, A. & Cox, D. R. Additive and multiplicative models for the joint effect of two risk factors. Biostatistics 6, 1–9 (2005).

Grambsch, P. M. & Therneau, T. M. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 81, 515–526 (1994).

Bassuk, S. S. & Manson, J. A. E. Oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy: relative and attributable risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health outcomes. Ann. Epidemiol. 25, 193–200 (2015).

Charlton, B. M. et al. Oral contraceptive use and mortality after 36 years of follow-up in the Nurses’ Health Study: prospective cohort study. BMJ 349, g6356 (2014).

Paget, J. et al. Global mortality associated with seasonal influenza epidemics: New burden estimates and predictors from the GLaMOR Project. J. Glob. Health 9, 020421 (2019).

Gurven, M. & Fenelon, A. Has actuarial aging ‘slowed’ over the past 250 years? A comparison of small-scale subsistence populations and european cohorts. Evolution 4, 1017–1035 (2009).

Beltrán-Sánchez, H., Crimmins, E. M. & Finch, C. E. Early cohort mortality predicts the cohort rate of aging: an historical analysis. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 3, 380 (2012).

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G. & Stuart, E. A. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J. Stat. Softw. 42, 1–28 (2011).

Wilson, E. B. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J Am. Stat. Assoc. 22, 209–212 (1927).

Burkman, R., Schlesselman, J. J. & Zieman, M. Safety concerns and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 190, 5–22 (2004).

Calle, E. E. et al. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet 347, 1713–1727 (1996).

Glindmeyer, H. W., Diem, J. E., Jones, R. N. & Weill, H. Noncomparability of longitudinally and cross-sectionally determined annual change in spirometry. Am. Rev. Resp. Dis.125, 544–548 (2015).

Cohen, A. A., Coste, C. F. D., Li, X. Y., Bourg, S. & Pavard, S. Are trade-offs really the key drivers of ageing and life span?. Funct. Ecol. 34, 153–166 (2020).

Bolund, E. The challenge of measuring trade-offs in human life history research. Evol. Hum. Behav. 41, 502–512 (2020).

Ruth, K. S. et al. Events in early life are associated with female reproductive ageing: a UK Biobank Study. Sci. Rep. 20, 24710 (2016).

Benyi, E. et al. Adult height is associated with risk of cancer and mortality in 5.5 million Swedish women and men. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 73, 730–736 (2019).

Stange, K. A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between fertility timing and schooling. Demography 48, 931–956 (2011).

Edlund, L. & Machado, C. How the other half lived: marriage and emancipation in the age of the pill. Eur. Econ. Rev. 80, 295–309 (2015).

Browne, S. P. & Lalumia, S. The effects of contraception on female poverty. J. Policy Anal. Manage. 33, 602–622 (2014).

Hummer, R. A. & Hernandez, E. The effect of educational attainment on adult mortality in the United States. Popul. Bull. 68, 1–16 (2013).

Iversen, L., Sivasubramaniam, S., Lee, A. J., Fielding, S. & Hannaford, P. C. Lifetime cancer risk and combined oral contraceptives: the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 216, e1–580 (2017).

Gierisch, J. M. et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast, cervical, colorectal, and endometrial cancers: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22, 1931–1943 (2013).

Havrilesky, L. J. et al. Oral contraceptive pills as primary prevention for ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol.122, 139–147 (2013).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013).

Pepinsky, T. B. A note on listwise deletion versus multiple imputation. Political Anal. 26, 480–488 (2018).

Dong, Y. & Peng, C.-Y. J. Principled missing data methods for researchers. SpringerPlus 2, 222 (2013).

King, G., Honaker, J., Joseph, A. & Scheve, K. Analyzing incomplete political science data: an alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 95, 49–69 (2001).

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D. & Simonsohn, U. False-positive psychology: undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1359–1366 (2011).

Therneau, T. M. & Grambsch, P. M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model (Springer, 2000).

Andersen, P. K. & Gill, R. D. Cox’s regression model for counting processes: a large sample study. Ann. Statist. 10, 1100–1120 (1982).

Therneau, T. A package for survival analysis in R. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/vignettes/survival.pdf (2022).

Mills, M. C. Introducing Survival and Event History Analysis (SAGE Publications Inc., 2011).

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G. & Stuart, E. A. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Anal.15, 199–236 (2007).

Nakazawa, M. Functions for medical statistics book with some demographic data. CRAN 1–40 http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/fmsb/fmsb.pdf (2015).

Newman, S. J. Early-life physical performance predicts the ageing and death of elite athletes. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf1294 (2023).

Acknowledgements

S.J.N. would like to thank Dr Theresa Neeman and Prof Simon Easteal for their assistance and advice, Prof Melinda Mills for her advice during writing, and Prof Eric Stone for his financial kindness in paying for UK biobank access. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.N. conceived, designed, preregistered, coded, wrote, and edited the manuscript and constructed the figures. H.B. co-wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Newman, S.J., Booth, H. Reproductive milestones and oral contraceptive timing predict late-life mortality. npj Womens Health 3, 26 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-025-00074-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-025-00074-y