Abstract

In order to solve the pollution of Cr3+ and toxic dyes cause by traditional tanning technology, this study developed chromium-free tanning agents (COS-Dyes-Al) that incorporate high-performance dyeing functions by using oligo-chitosan (COS) as a matrix and chemically modifying it with three types of dyes, reactive Blue R19, tartrazine, and eosin B, and then coordination with Al (III). COS-Dyes-Al exhibit excellent tanning properties, raising the shrinkage temperature of leather to 98.6 °C, with tensile and tear strengths reaching 17.4 MPa and 70.1 N/mm, respectively, along with superior durability against rubbing and washing. Moreover, COS-Dyes-Al reduced the environmental burden by effectively integrate tanning and regulable color dyeing functionality into the leather. The COS-Dyes-Al tanning system can save 60–80% of water, 30% of electric energy, and 50–70% of thermal energy. Therefore, the tanning system helps to reduce the carbon footprint in leather production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leather manufacturing plays a vital role in the high-value utilization of waste animal skins1. In recent years, leather products have attracted wide attention due to their fashionable appearance and long service life. However, with growing environmental awareness, the leather industry has faced significant challenges2. Tanning is the most crucial step in the traditional leather manufacturing process, as it transforms raw hides into leather. At present, chrome tanning agents are widely used in leather tanning3,4. However, the wastewater and residues generated by chrome tanning, which contain significant amounts of chromium, have become a major obstacle to the ecological advancement of the leather industry5,6,7. These challenges impede the sustainable growth of the leather industry. Therefore, the development of chrome-free tanning is the key to realize the ecological transformation of leather industry.

Currently, there are two primary types of commercial chrome-free tanning agents: non-chrome metal-based and organic agents8,9,10. Non-chromium metal tanning agents primarily consist of aluminum and zirconium-based agents. Organic chrome-free agents, such as TWS (an amphoteric tanning agent with aldehyde groups), F-90 (containing active chlorine), and vegetable tannins like tannic acid, offer advantages over other chrome-free agents due to their customizable molecular structures and diverse functions11. However, these agents primarily cross-link with the –NH2 groups of collagen fibers during tanning, which lowers the isoelectric point (pI) of the leather to around 5.012. This negatively impacts subsequent wet finishing processes, as anionic fat liquors and dyes do not firmly bond with the leather13,14, contributing to water pollution and increased chemical oxygen demand (COD) in the wastewater15,16.

Bio-based materials have the advantages of non-toxicity, abundant content, renewable, degradable, and good biocompatibility. Chitosan has been widely used in leather as a kind of biomass polysaccharide material. For example, Liang et al.17 used glyceryl ether (GTE) and oligo-chitosan (COS) to obtain a non-tanning agent COS-GTE. Leather tanned with COS-GTE exhibits exceptional mechanical and physical properties, along with excellent antibacterial performance. In another example, to address the issues of poor physical and mechanical properties and the lack of positive charge in crust leather tanned with single dialdehyde carboxymethyl cellulose (DCMC), Ding et al.18 modified chitosan with H2O2 to produce low molecular weight chitosan (LMC) with a lower positive charge, thereby improving the tanning effect.

Therefore, guided by the principles of environmental sustainability, the development of multi-functional integrated materials offers a promising solution to simplify leather making process of chromium-free tanning technologies. Previous studies have explored multifunctional additives to streamline tanning processes. For example, Ding et al.6 prepared an integrated tanning and dyeing bi-functional material, which not only ensured the tanning effect, but also had excellent dyeing properties for billet leather. Liang et al.19 developed the chromium-free tanning agent OCS-R19-ECH, which integrates both tanning and dyeing functions, using oligosaccharide (OCS), reactive blue R19, and epichlorohydrin (ECH) as key components. Leather treated with OCS-R19-ECH exhibits superior physical and mechanical properties, along with excellent resistance to wet and dry abrasion. Similarly, Li et al.20 extracted MFA (mineral sourced fulvic acid) rich in carboxyl, hydroxyl and quinone functional groups from weathered coal. Then a series of chromium-free tanning agents containing aluminum were obtained by using different amounts of aluminum sulfate in coordination with MFA. The leather tanned with this tanning agent has a shrinkage temperature exceeding 90°C. Due to the different aluminum content of the coordination with MFA, a range of different colors of leather from brown to black can be prepared according to demand. But the simple color does not meet the market demand, and limits its use value.

In addition, with the deepening of the country’s “dual carbon” strategy, it is imperative to guide the leather industry in carrying out related work and establish a carbon emission and carbon footprint accounting and evaluation system for the industry. At the same time, carbon emission accounting can provide strong data support for promoting the environmental friendliness of natural leather, especially in response to the impact of substitute materials. The “dual carbon” work is an inevitable path for the leather industry to establish itself21,22.

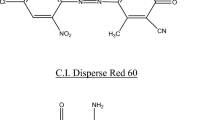

In this study, three chrome-free tanning agents, COS-E-Al (red powder), COS-T-Al (yellow powder), and COS-R-Al (blue powder), were prepared using chitosan, Eosin B, Tartrazine, Reactive Blue R19, and Al2(SO4)3⋅18H2O as raw materials. Proof by LCA accounting, the development of COS-Dyes-Al tanning-dyeing integrated materials effectively solves the traditional tanning process chemical dosage, processing time is long, wastewater discharge pollution, and other issues, for the leather industry towards low-carbon, low pollution, sustainable development is of great significance.

Results

Structural analysis of COS-E, COS-T, COS-R, and COS-Dyes-Al

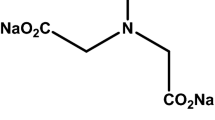

COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R powders were synthesized via amination reaction and Michael addition reaction using COS, eosin B, tartrazine, and reactive blue R19 (Supplementary data). Then COS-Dyes-Al was obtained by a coordinated reaction of Al2(SO4)3⋅18H2O with COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R (Fig. 1(a)).

As shown in Fig. 1(b), for eosin B and tartrazine molecules, the stretching vibration peak of C = O appears at 1750 cm−1, and at 3400 cm−1, there is a broad absorption band, which is the stretching vibration peak of O-H. This indicates the presence of -COOH in the eosin B and tartrazine molecules23. The absorption peak at 1640 cm−1 is attributed the C = C of reactive blue R19. The absorption peaks at 3400 cm−`1 and 2900 cm−1 are O–H and C–H bonds9, respectively. The peaks appearing at 1242 cm−1, 1261 cm−1 and 1257 cm−1 are the C-N bond in reactive blue R19, tartrazine, and eosin B molecules, respectively. The –COOH vibration absorption peaks of COS-E and COS-T and the C = C absorption peak of COS-R disappeared after the reaction of COS with each other. In addition, the COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R molecular structures retain the basic backbone of COS and dye molecules (eosin B, tartrazine, and reactive blue R19 molecule). This indicates that COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R were synthesized.

The active functional groups of eosin B and tartrazine are Ph–COOH and –CH2–COOH, respectively. The chemical shifts of protons were 9.9 ppm and 9.7 ppm24, respectively. It can be observed from the 1H-NMR spectra of COS-E (Fig. 1(c)) and CT (Fig. 1(d)) that there are no peaks above 9 ppm, and no amino peaks (at 1.6 ppm) are present. This indicates that the –COOH and –NH2 groups have reacted. The peak position of the H proton in “–CH = CH–“ is about 6.5 ppm, while there is no peak at 6–7 ppm in the 1H-NMR spectrum (Fig. 1(e)), indicating that there is no peak of H proton in double bond. Thus, it can be speculated that for the 1H-NMR spectrum of CR, the peak appearing at 1.6 ppm is the peak of the amino group in R19. At the same time, the amide proton peak at ppm = 8.0–8.5 appeared in COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R. In addition, characteristic peaks of COS and its corresponding dyes (eosin B, citric yellow and reactive blue R19) appeared in the 1H-NMR spectrum of COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R, which further indicated that COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R were synthesized successfully.

In order to demonstrate the coordination of Al(III) with CE, CT, and COS-R, the C1S and O1S orbitals of COS-Dyes-Al were investigated by XPS. In COS-Dyes-Al, the binding energy of C–O and C = O increase to 288.7 eV and 535.3 eV25 (Fig. 1(f)–(i)). This is due to the formation of coordination bonds between –OH and Al(III) in COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R, which results in the change of electron cloud density26. In addition, two orbitals with binding energies of 75.1 and 76.3 eV can be fitted to the Al2p orbital in COS-Dyes-Al (Fig. 1(j)). They correspond to Al2p3/2 and Al2p1/2, respectively. This indicates that the–OH in COS-E, COS-T and COS-R form an Al-O bond27.

Tanning performances of COS-Dyes-Al

It can be seen from Fig. 2(a), leather is a typical amphoteric material, and the pI of pickled skin is about 5.5 (Fig. S1(a)). After TWS tanning, the pI of the crust leather was reduced to 5.111 (Fig. S1(b)). Because the active functional group of TWS is aldehyde group, which mainly reacts with the –NH2 of collagens, thus enhancing the electronegative property of the collagen fiber. In contrast, the metal tanning agent primarily interacts with the –COOH groups in the collagen of the leather, so the pI of Al2(SO4)3⋅18H2O tanned leather can reach 8.4 (Fig. S1(c)). For COS-Dyes-Al, the active functional groups in their molecular structure mainly react with the carboxyl group of collagens, so the pI of the billet leather after tanning by COS-Dyes-Al is about 6 (Fig. S1(d)–(f)). In the fatliquoring process after tanning, the fatliquors are often anionic (e.g., LQ-5)16. Therefore, higher pI can improve the absorption rate of fatliquors. The function of fatliquor is to reduce the relative sliding resistance between the fibers and improve its mobility, so the better the absorption of fatliquors (Fig. 2(b)), the better the softness of the leather after fatliquoring28 (Fig. 2(c)).

a Cross-linking mechanism of TWS and Al (III) with leather collagen and isoelectric point of leather. b Softness, (c) Absorptivity of fatliquor, and (d) water washing resistance. e–g Distribution of Al in different positions of the leather cross-section. h–j are the shrinkage temperature, tensile strength, and tear strength of crust leather, respectively.

Physical and mechanical characteristics of crust leather are closely related the penetration and distribution of tanning agents in the collagen. As illustrated in Fig. 2(h), the TS of pickled skin is the lowest, which results from the damage to the fiber structure during pretreatment. Furthermore, the TS of leather tanned with Al (III) is lower than that of leather tanned with TWS. As can be seen from Fig. 3(d), the water-wash fastness of the leather tanned with Al (III) is the poorest. This is because Al, after forming the Al³⁺, loses three outer electrons, and its electron configuration becomes [Ne] 3 s² 3p¹. The electron configuration of Al³⁺ is 3s03p03 d0. When it forms a coordination complex with a ligand containing lone pair electrons (such as –COOH), it utilizes the empty 3d orbitals in the outer shell, leading to the formation of an unstable outer orbital complex29. Additionally, the distribution of Al (III) is highly uneven across the leather cross-section (Fig. S2). As a result, the TS of Al (III)-tanned leather is lower than that of TWS-tanned leather30,31. The Ts of leather tanned with COS-Dyes-Al is greater than that of the other two tanning agents, as COS-Dyes-Al is uniformly distributed throughout the leather’s cross-section (Fig. 2(e)–(g)). And COS-Dyes-Al molecules contain a variety of active functional groups which can form multi-crosslinks with the leather collagen32. The Al (III) can form a coordination bond with the –COOH of skin collagen. And the –COOH in COS-Dyes-Al can further form hydrogen bonds with the –NH2, –COOH and other active functional groups of collagen. As shown in Fig. 2(i), (j), COS-R-Al tanned leather showed the best performance, with tensile strength (17.4 MPa) and tear strength (71.4 N/mm) higher than other tanned leather33. This is due to the difference in the amount of coordinated Al (III) in COS-Dyes-Al molecules. It is important to note that the tensile and tear strength of COS-E-Al and COS-T-Al tanned leather meet the standards for garment leather. (6.5 MPa and 20 N/mm)34,35. The physical and mechanical properties of leather tanned by different combinations of COS-E-Al, COS-T-Al, and COS-R-Al are shown in Table S5.

Analysis of micro-structure

Leather is a multi-layered fiber network material, composed of collagen molecules (Φ = 1.4 nm), fibril (Φ = 50–200 nm), base fibers (Φ = 2–10 μm), and fiber bundles (Φ = 20–200 μm). When different levels are assembled, a multistage pore structure consisting of micropores, mesoporous pores, and macropores is formed36 (Fig. 3(a)). The pore structure of leather can reflect the dispersion degree of collagen fibers. The pore size of PS is mainly distributed between 100–10,000 nm (Fig. S3(a)), while the pore size of the crust leather is mainly concentrated between 1000–100,000 nm (Figs. S3(b)–(f)). Therefore, it can be assumed that the tanning agent molecules don’t enter the collagen fibril. In addition, the porosity, average pore size, and the proportion of large holes of the crust leather increased significantly. In particular, the pore sizes smaller than 100 nm of leather tanned with COS-Dyes-Al almost disappeared, accounting for 1.4%, 1.5%, and 0.7%, respectively37 (Figs. S3(g)–(l)). This is because COS-Dyes-Al plays the role of filling, binding, and coating in the collagen fiber network. The gap between the base fiber and the fibril is blocked, and most of the molecules are between the base fiber and the fiber bundle, so that the tanning agent can produce cross-linked filling effect to achieve the tanning effect38,39.

The dispersion of collagen fibers can provide further evidence of the tanning properties of tanning agents. A better tanning effect results in a higher degree of dispersion of the collagen fibers17. The cross-section SEM images of the leather tanned with different tanning agents are shown in Fig. 3(b). As illustrated by the data, the collagen fibers of the pickled skin are tightly bonded together, and can’t observe the fine fiber. After TWS and Al (III) tanning, the collagen fibers were dispersed to a certain extent, but there are still the binding fiber bundles. However, the degree of dispersion of collagen fibers after tanning with COS-Dyes-Al is considerably greater than that of leather tanned with other two agents. The D-periodic (65 nm) of the crust leather treated with different tanning agents was consistent with that of the pickled skin. This indicates that tanning agents do not enter the triple helix layer of collagen fibers40. The excellent dispersion of collagen fibers makes the grain pores on the surface clear and orderly41(Fig. 3(c)).

Dyeing performances of COS-Dyes-Al

COS-E-Al (red), COS-T-Al (yellow), and COS-R-Al (blue) can be mixed in different proportions to obtain colorful leather, and its preparation principle is shown in Fig. 4(a). The digital photos of the colored leather are shown in Fig. 4(b). The color change of different leather can be clearly seen from the CIE coordinates (Fig. 4(c)). Figures 4(d)–(g) illustrate the differences in color fastness and depth of COS-Dyes-Al tanned leather and leather dyed with conventional anionic dyes. As shown in Fig. 4(d), (e), the resistance to dry and wet rubbing of TWS-tanned leather colored with conventional anionic dyes is significantly inferior to that of leather dyed with COS-Dyes-Al. In particular, COS-Dyes-Al tanned leather exhibits excellent washing properties (Fig. 4(f)). This difference is mainly caused by the different cross-linking mechanisms between COS-Dyes-Al and conventional dyes and leather. COS-Dyes-Al forms chemical cross-links (ligand bonds) with collagen, whereas conventional anionic dyes are mainly physically adsorbed (electrostatic interaction) with collagen. In addition, the leather tanned by TWS has a low pI, which makes the leather fibrils carry a large amount of negative charge, thus preventing the binding between the leather collagen fibers and the dye. This is also one of the main reasons for the uneven dyeing of billets after TWS tanning (Fig. 4(f)).

a The principle of COS-Dyes-Al toning. b Digital photograph of leather obtained after tanning using different proportions of COS-E-Al, COS-T-Al, and COS-R-Al (c) different leather sample’s CIE coordinates. d, e The dry and wet rubbing resistance and (f) color fastness to washing. g K/S value and (h) uniformity of color in leather dyed with COS-Dyes-Al.

Analysis of tanning mechanism

The structure of collagen was examined before and after tanning with various tanning agents using FT-IR spectroscopy. As illustrated in Fig. 5(a), amide A band and amide B band are the two main absorption bands in the infrared spectrum of amide bonds. The amide A band is the strongest absorption band in the amide bond, approximately located in 3300 cm−1, and is mainly generated by N-H stretching vibrations. However, the amide B band is approximately located in 2900 cm−1 and is mainly related to the stretching of C–N and –CH2. The peak at 1700 cm−1 is the amide I band peak, which is associated with the C = O stretching vibration to be associated with. And the peak at 1500 cm−1 is the amido II band, which is associated with C–N stretching vibration42. After COS-Dyes-Al tanning, the amide A band of collagen was shifted, and the peak gradually became stronger and wider, which indicated that the interaction between collagen and tanning agent molecules occurred. It can also be seen from the XPS image (Fig. 5(b), (c)) that after COS-Dyes-Al tanning, the content of O = C–O and C–O–C increases, because COS-Dyes-Al molecules contain a large number of O = C-O and C-O-C bonds. In addition, it can also be seen from the XPS image (Fig. 5(b), (c)) that after COS-Dyes-Al tanning, the content of O = C–O and C–O–C increases, because COS-Dyes-Al molecule contains a large number of O = C–O and C–O–C bonds, and after cross-linking with collagen, the content of O = C-O and C-O-C bonds in collagen was increased.

Tanning mechanism of COS-Dyes-Al. a Infrared spectrum of leather treated with different tanning agents, b, c XPS of PS, and XPS of COS-Dyes-Al (the ratio of COS-E-Al: COS-T-Al: COS-R-Al= 1:1:1). d–h FT-IR curve-fitting between wavenumber of 1700–1600 cm−1 of different leather samples, and (i) the ratio of α-helix, β-sheet, β-turn, and random coil of different samples.

The composition of collagen secondary structures was further explored by infrared peak fitting analysis in the amide I region (1700–1600 cm−1)38,42 (Fig. 5(d)–(h)). The proportions of various secondary structures, including α-helix, β-sheet, β-turn, and random coil, are calculated by peak area (Tables S7, S8). As shown in Fig. 5(i), both α-helix and β-sheet structures in skin collagen increased after tanning with various agents compared to PS. Notably, random coil structures were absent in collagen tanned with COS-Dyes-Al, unlike those tanned with the other agents. This suggests that the introduction of O-Al bonds contributes to a more organized collagen structure. Additionally, the α-helix, being the most stable secondary structure in proteins, enhances collagen fiber stability with its increased proportion. In addition, increasing the amount of β-sheet, which is the looser part of the secondary structure, allows the active functional groups of tanning agent molecules to react better with the active functional groups of collagens. Consequently, the physical and mechanical characteristics of leathers tanned with COS-Dyes-Al were better than those tanned with the other two agents, aligning with earlier experimental findings.

The application of fluorescence (COS-T-Al) leather

The penetration and distribution of tanning agents across the entire leather cross-section during the tanning process are crucial factors influencing the properties of the crust leather. The fluorescence tracer technique is an effective and reliable analytical method to characterize the penetration process of tanning agents in leather. Figure 6(I) shows the penetration process of fluorescent dye (COS-T-Al) in leather. It can be seen from Fig. 6(II) that the COS-T-Al molecules mainly penetrate from the flesh and grain of leather, but because the collagen fibers of the flesh are loosely organized and the fiber gap is larger, it is easier to penetrate than the grain surface43. 30–180 min after tanning, COS-T-Al molecules slowly permeate into the skin from both sides evenly. With the increase of tanning time (360 min), a uniform fluorescence signal was detected on the entire longitudinal section of the leather44,45. In general, the use of materials with fluorescent signals to visualize tanning additives during the leather penetration process can help tanners optimize tanning time, thus achieving the purpose of energy conservation.

(I) Penetration process of COS-Dyes-Al in leather. (II) Fluorescent images of different penetration times (30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 240 and 360 min) of COS-Dyes-Al in leather. (III) (a) Methods for preparing anti-counterfeiting patterns, (b), (c), application of COS-Dyes-Al in leather anti-counterfeiting.

In addition, the use of leather additives with fluorescent properties can also help in the anti-counterfeiting design of leather products. In this study, a multi-response leather anti-counterfeiting pattern was designed by a simple surface brush coating method (Fig. 6(III) (a)). As shown in Fig. 6(III)(c), a “heart” pattern can be a constructed on the leather surface by using materials that respond in different ways (temperature response and light response). According to the demand, in the natural state, the “heart” pattern on the surface of the leather can be in the state of appearance or invisibility. When the external conditions change, the surface temperature is greater than 37°C or the leather samples exposed to ultraviolet light (365 nm), the pattern color will change. Moreover, barcodes and QR codes, which are widely used as modern information transmission tools, have also been incorporated into leather products (Fig.6(III)(b)). By altering external conditions, the encryption of the codes can be modified, allowing information to be read via mobile phone scanning. This method is more effective than traditional methods (relying on touch) in identifying the authenticity of leather.

Analysis of environmental impact

The ecological effects of leather manufacturing significantly hinder the industry’s ability to develop sustainably. COS-Dyes-Al tanning process as shown in Table S1. Compared with other traditional tanning processes (Tables S2, S3), the COS-Dyes-Al tanning process is significantly simplified, reducing the use of tanning chemicals and additives. Thereby, the BOD and COD of the wastewater are reduced (Table 1). Furthermore, the electro-positivity of the leather after tanning by TWS is insufficient, resulting in a low binding rate of anionic materials and collagen in the subsequent processing stages. The unreacted additives persist in the tannery wastewater, leading to higher levels of COD and BOD in the water. The BOD/COD ratio of wastewater generated from conventional tanning methods is below 0.3, suggesting that biodegradation is challenging46,47.

To further illustrate the advantages of COS-Dyes-Al in tanning, LCA was used to compare the environmental effects of COS-Dyes-Al with two other chromium-free tanning agents (MFAA-8 and DCST-EDGE). The LCA outcomes for the three chromium-free tanning systems are presented in Fig. 7 and are elaborated in Tables S4–S9. As illustrated in the diagram, compared with the DCST-EGDE system, COS-Dyes-Al can save 80% of water, 80% of thermal energy, and 30% of electrical energy. In addition, compared with other tanning-dyeing integrated systems (MFAA-8 system), the COS-Dyes-Al system can save 70% of water and 50% of thermal energy. It is worth noting that the COS-Dyes-Al system also exhibits low human toxicity (HTC and HTNC: COS-Dyes-Al < MFAA-8 < DCST-EGDE). And it can also make a huge contribution to reducing the greenhouse effect (GWP: COS-Dyes-Al < MFAA-8 < DCST-EGDE) (Fig. 7). In summary, the COS-Dyes-Al tanning system minimizes the carbon footprint associated with production and lessens the environmental effects of several harmful substances. As a result, this tanning technique serves as a benchmark for the eco-friendly and sustainable advancement of the tanning industry.

Discussion

In this study, a high-efficiency tanning-dyeing system was developed with simple, energy-efficient, and regulable color-dyeing, to simplify the leather process and reduce the carbon footprint. The leather treated with COS-Dyes-Al demonstrated excellent physical and mechanical properties, with shrinkage temperature reaching up to 98 °C, tensile strength and tear strength exceed 17 MPa and 70 N/mm, respectively. Furthermore, COS-Dyes-Al dyed leather exhibited superior resistance to rubbing and washing, linked to the creation of coordination bonds. And the fluorescent properties of COS-Dyes-Al enabled the visualization of mass transfer processes within the leather, and their combination with photosensitive/thermosensitive dyes allows for their application in anti-counterfeiting. Remarkably, the COS-Dyes-Al tanning system can save 50–70% of water, 30% of electric energy, and 50–70% of thermal energy. Moreover, this system reduced greenhouse and human health impacts by approximately 50% and 75%, respectively. Therefore, this strategy is of great significance for the sustainable development of the leather industry.

Methods

Materials

COS was prepared by our experiment (Mw = 1014 g/mol). Reactive Blue R19 (C22H16N2Na2O11S3, intensity:100%), tartrazine (C16H9N4Na3O9S2, >95% (HPLC)), eosin B (C20H6N2O9Br2Na2, biological stain), Al2(SO4)3⋅18H2O (99% metals basis), anhydrous ethanol (AR), anhydrous methanol (AR), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl aminopropyl) carbodiimide (AR), formic acid (for HPLC, ≥ 99%), sodium bicarbonate (for HPLC, ≥ 99.0%), N-hydroxy succinimide (98%), and sodium carbonate (for HPLC, ≥ 99.0%) were obtained from Shanghai Maclin Biochemical Technology Co., LTD. All chemicals are used directly without purification. Pickled sheepskins (PS) were supplied by Longfeng (Hebei, China) Leather Co., Ltd. TWS is a commercially available, chromium-free tanning agent produced by Sichuan Tingjiang New Materials Co., Ltd. It is an amphoteric organic tanning agent that contains an aldehyde group.

Synthesis of COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R

Firstly, 4 g of Eosin B was dissolved in 10 mL of deionized water and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 5. Then 2.45 g of EDC (12.8 mmol), 0.74 g of NHS (6.4 mmol) were added to the solution with slow stirring for 30 min to activate the reaction system. The, 1.03 g COS was introduced, and reaction mixture was heated to 60 °C for 24 h. After the reaction was finished, the solid was precipitated with anhydrous ethanol and washed repeatedly until the waste solution appeared colorless. Finally, the solid was dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 24 h to obtain a red powder named COS-E. The yellow powder (COS-T) was prepared in the same way as described above, except for the dosages of COS, EDC, and NHS. The amount of COS (1.2 g), EDC was 2.88 g (15 mmol), and NHS was 0.86 g (7.5 mmol).

5 g of COS and 4 g of reactive blue R19 were dissolved in 20 mL of deionized water, and then the pH of the solution was adjusted to 8. The above solution was placed in an oil bath at 50 °C with stirring and reacted for 2 h. At the end of the reaction, after the solution was cooled down to room temperature, the solids were precipitated with anhydrous ethanol and washed repeatedly until the waste solution was colorless. Finally, the solid was dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 24 h to obtain a blue powder named COS-R.

Synthesis of COS-Dyes-Al

COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R (15 g each) were dissolved in deionized water (50 mL), and the pH was adjusted to 2.5–3 with formic acid. Then, Al2(SO4)3·18H2O (1.5 g) was incorporated, and the mixture was reacted at 45 °C for 2 h. The product was freeze-dried to obtain a solid powder, which was washed several times with anhydrous methanol to remove unreacted Al3+. Afterward, the powder was dried at 60 °C in a vacuum oven for 24 h, yielding chromium-free tanning agents in red, yellow, and blue colors, named COS-E-Al, COS-T-Al, and COS-R-Al, respectively, collectively referred to as COS-Dyes-Al.

Characteristics of COS-Dyes-Al

COS-Dyes-Al was analyzed be the Fourier infrared spectrometer (Bruker VECTOR-22) with the potassium bromide (KBr) pellet method, set at a 4 cm-1 resolution and a wavenumber range between 500 and 4000 cm−1.COS-E, COS-T, and COS-R were dissolved in D₂O to prepare 20 mg/mL solutions to analyze 1HNMR by using the spectrometer (Bruker AVANCE III 600 MHz). The elemental composition and chemical structure of COS-Dyes-Al were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (Thermos ESCALAB 250XI).

Determination of the coordination rate of Al (III)

COS-Dyes-Al solutions into 50 ml corked conical bottle and add 20 ml anhydrous methanol to the conical bottle. At room temperature, shake the mixture for 3 h. Then centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 15 min. Free Al (III) content was quantified using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS, PerkinElmer NexION 300X, USA). The coordination rate of Al (III) was then calculated based on the formula (1)48:

Where, C0 (mg/L) is the initial concentration of Al (III), and C1 (mg/L) is the concentration of Al (III) free aluminum.

Tanning process

Five different tanning agents, Al2(SO4)3⋅18H2O, TWS, and COS-Dyes-Al, were used in the tanning experiment. Different tanning agents correspond to different tanning methods. Specific tanning methods are presented in the Tables S1–S3. Tanning agents with different colors can be prepared based on the principle of three primary colors. In addition, COS-E-Al, COS-T-Al, and COS-R-Al can be mixed in different proportions to produce different leather colors. Specific programmers are in the Table S4.

Physical and mechanical properties test

The shrinkage temperature (Ts) of pickled leather treated with Al2(SO4)3⋅18H2O, TWS, and COS-Dyes-Al was recorded by the MSW-YD4, China. To test the washable resistance of various samples, the leather sample was cut into 3 × 3 cm and added into a conical bottle with 100 ml of distilled water. Next, place the conical bottle inside the temperature and humidity control chamber, adjust the temperature to 25 °C, and shake it for a specified duration. Samples were collected at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 h, and the Ts were recorded. The leather’s softness (mm) was assessed with a softness testing device. (303-D, China). The mechanical and physical characteristics of the sample can be tested with a universal tensile machine (TH-8203 S, Chian). The speed of the tensile testing machine was 100 ± 20 mm/min. The penetration process of COS-E-Al of the leather by using a laser confocal microscope.

Before the test, all samples were first dried and then air-conditioned (humidity 65% ± 2%, temperature 20 °C ± 2%, time 24 h). Every sample underwent three tests, and the results were averaged.

The microstructure of crust leather

The dispersion of fibers in the leather section was observed using scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi JSM-7800F). The grain flatness of the leather samples was examined using a super depth of field microscope (KEYENCE VHX-7000).

Analysis of dyeing test

The desktop spectrophotometer (ci7800, X-Rite, USA) is utilized to assess the L, a, and b, refers to lightness red-green axis and red-blue axis, respectively, and color shades (K/S) of leather after dyeing. The total color difference was calculated using the formula (2)9:

Where, ΔE, ΔL, Δa, and Δb refer to the total color difference, brightness variation, and differences in the red-green and yellow-blue axes, respectively.

A smaller ΔE indicates better friction resistance of the leather surface color. In addition, the color fastness to washing was measured by an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Cary 5000, Agilent, America).

Isoelectric point (pI) of the leather

The pickled skin and leather tanned with various agents were dried and ground into a fine powder. A 5 g of powder was placed in a 100 mL conical flask, and 50 mL of distilled water was added. The flask was incubated in a temperature-controlled shaking chamber at 30 °C for 30 min. The pH of the solution was adjusted to between 1 and 10 using HCl or NaOH (0.1 mol/L). The supernatant was then collected, and the pH of the samples was measured using a nanoparticle-size analyzer (Nano-ZS90, Malvern, US).

Analysis of tannery wastewater

The TOC was determined by TOC analyzer, which was employed to assess the absorption rate of fatliquor. The chemical oxygen demand (CODCr) of the wastewater was tested with the amount of potassium dichromate consumed in the redox reaction, and the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) was determined by iodometry.

Life cycle assessment

The life cycle assessment (LCA) analysis was conducted by OpenLCA 2.2.0 to assess the environmental impact of COS-Dyes-Al49. The functional units were set up to produce 1 ton of sheep pickled hide. The system boundary includes some necessary tanning processes. In this study, some impact categories were selected in CML v4.8 2016 and EF v3.1 for environmental impact assessment. The detailed process of LCA is shown in Figs. S1–S6.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [Xugang Dang: xg.dang@sust.edu.cn], upon reasonable request.

References

Ding, W., Remón, J. & Jiang, Z. Biomass-derived aldehyde tanning agents with in situ dyeing properties: a ‘Two Birds with One Stone’ strategy for engineering chrome-free and dye-free colored leather. Green. Chem. 24, 3750–3758 (2022).

Hansen, É., de Aquim, P. M., Gutterres, M. Environmental assessment of water, chemicals and effluents in leather post-tanning process: a review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 89, 106597 (2021).

Qiang, T., Chen, L., Zhang, Q. & Liu, X. A sustainable and cleaner speedy tanning system based on condensed tannins catalyzed by laccase. J. Clean. Prod. 197, 1117–1123 (2018).

Madhu, V., Mayakrishnan, S., Muthu, J., Sekar, K. & Madurai, S. Win–win approach toward chrome-free and chrome-less tanning with waterborne epoxy polymers: a sustainable way to curb the use of chrome. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 6082–6092 (2024).

Yi, Y. et al. Formaldehyde formation during the preparation of dialdehyde carboxymethyl cellulose tanning agent. Carbohydr. Polym. 239, 116217 (2020).

Ding, W. et al. Providing natural organic pigments with excellent tanning capabilities: a novel “one-pot” tanning–dyeing integration strategy for sustainable leather manufacturing. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 17346–17354 (2022).

J, K. Panda, R. C. M, V. K. Trends and advancements in sustainable leather processing: Future directions and challenges—a review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 104379 (2020).

Liu, X., Wang, Y., Wang, X. & Jiang, H. Development of hyperbranched poly-(amine-ester) based aldehyde/chrome-free tanning agents for sustainable leather resource recycling. Green. Chem. 23, 5924–5935 (2021).

Wang, X. Su, R. Hao, D. Dang, X. Sustainable utilization of corn starch resources: a novel soluble starch-based functional chrome-free tanning agent for the eco-leather production. Ind. Crop. Prod. 187, 115534 (2022).

Gao, D. et al. An eco-friendly approach for leather manufacture based on P(POSS-MAA)-aluminum tanning agent combination tannage. Journal of Cleaner Production 257 2020.

Hao, D. et al. Sustainable leather making - An amphoteric organic chrome-free tanning agents based on recycling waste leather. Sci. Total Environ. 867, 161531 (2023).

Wei, C. Wang, X. Wang, W. Sun, S. Liu, X. Bifunctional amphoteric polymer-based ecological integrated retanning/fatliquoring agents for leather manufacturing: simplifying processes and reducing pollution. J. Clean. Prod. 369, 133229 (2022).

Krishna Priya, G. et al. Next generation greener leather dyeing process through recombinant green fluorescent protein. J. Clean. Prod. 126, 698–706 (2016).

Hao, D. et al. A novel eco-friendly imidazole ionic liquids based amphoteric polymers for high performance fatliquoring in chromium-free tanned leather production. J. Hazard Mater. 399, 123048 (2020).

Liang, S. et al. Polysaccharides for sustainable leather production: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 22, 2553–2572 (2024).

Sun, S. et al. Synthesis of an amphiphilic amphoteric peptide-based polymer for organic chrome-free ecological tanning. J. Clean. Prod. 330, 129880 (2022).

Liang, S., Wang, X., Hao, D., Yang, J. & Dang, X. Facile synthesis of a new eco-friendly epoxy-modified oligomeric chitosan-based chrome-free tanning agent towards sustainable processing of functional leather. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 172, 753–763 (2023).

Ding, W. et al. Constructing a robust chrome-free leather tanned by biomass-derived polyaldehyde via crosslinking with chitosan derivatives. J. Hazard Mater. 396, 122771 (2020).

Liang, S., Wang, X., Xie, L., Liu, X. & Dang, X. Discarded enoki mushroom root-derived multifunctional chrome-free chitosan-based tanning agent for eco-leathers manufacturing: Tanning-dyeing, non-acid soaking, and non-basifying. Int J. Biol. Macromol. 275, 133394 (2024).

Li, R. et al. Construction of fulvic acid-based chrome-free tanning agent with on-demand regulation and wastewater recycling: a novel tanning-dyeing integrated strategy. Chem. Eng. J. 482, 148892 (2024).

Tasca, A. L. & Puccini, M. Leather tanning: life cycle assessment of retanning, fatliquoring and dyeing. J. Clean. Prod. 226, 720–729 (2019).

Marrucci, L., Corcelli, F., Daddi, T., Iraldo, F. Using a life cycle assessment to identify the risk of “circular washing” in the leather industry. Res. Conserv. Recycl. 185, 106466 (2022).

Shen, Y. et al. One-step synthesis of starch-based composite chrome-free tanning agents via in situ catalysis using hydrotalcites. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 11342–11352 (2023).

Shen, Y., Ma, J., Fan, Q., Gao, D. & Yao, H. Strategical development of chrome-free tanning agent by integrating layered double hydroxide with starch derivatives. Carbohydr. Polym. 304, 120511 (2023).

Yu, T. et al. Novel reusable sulfate-type zirconium alginate ion-exchanger for fluoride removal. Chin. Chem. Lett. 32, 3410–3415 (2021).

Tan, X., Fang, M., Li, J., Lu, Y. & Wang, X. Adsorption of Eu(III) onto TiO2: effect of pH, concentration, ionic strength and soil fulvic acid. J. Hazard Mater. 168, 458–465 (2009).

Tang, T., Zhang, M., Mujumdar, A. S., Li, C. 3D printed curcumin-based composite film for monitoring fish freshness. Food Packag. Shelf Life 43, 101289 (2024).

Liu, X., Wang, W., Wang, X., Sun, S., Wei, C. A “Taiji-Bagua” inspired multi-functional amphoteric polymer for ecological chromium-free organic tanned leather production: Integration of retanning and fatliquoring. J. Clean. Prod. 319, 128658 (2021).

Liang, S. et al. Remediation and resource utilization of Cr(III), Al(III) and Zr(IV)-containing tannery effluent based on chitosan-carboxymethyl cellulose aerogel. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 10, 77–91 (2025).

Dang, X. et al. β-cyclodextrin-based chrome-free tanning agent results in the sustainable and cleaner production of eco-leather. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 3715–3725 (2024).

Shen, Y., Ma, J., Fan, Q., Yao, H., Zhang, W. A novel engineering bridging complexation strategy based on biomass-derived oligosaccharides hydrotalcite silicon aluminum composites for high-quality green leather manufacturing. Ind. Crop. Prod. 210, 118133 (2024).

Jiang, Z. et al. On the development of chrome-free tanning agents: an advanced Trojan horse strategy using ‘Al–Zr-oligosaccharides’ produced by the depolymerization and oxidation of biomass. Green. Chem. 23, 2640–2651 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Preparation and application of tremella polysaccharide based chrome free tanning agent for sheepskin processing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 241, 124493 (2023).

Ding, W. et al. A step-change toward a sustainable and chrome-free leather production: Using a biomass-based, aldehyde tanning agent combined with a pioneering terminal aluminum tanning treatment (BAT-TAT). J. Clean. Prod. 333, 130201 (2022).

Gao, M., Remon, J., Ding, W., Jiang, Z. & Shi, B. Green and sustainable ‘Al-Zr-oligosaccharides’ tanning agents from the simultaneous depolymerization and oxidation of waste paper. Sci. Total Environ. 837, 155570 (2022).

He, X. et al. Tanning agent free leather making enabled by the dispersity of collagen fibers combined with superhydrophobic coating. Green. Chem. 23, 3581–3587 (2021).

Yu, Y. et al. Biomass-derived polycarboxylate–aluminum–zirconium complex tanning system: a sustainable and practical approach for chrome-free eco-leather manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 452, 142261 (2024).

Pellegrini, D. et al. Study of the interaction between collagen and naturalized and commercial dyes by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis. Dyes Pigments 116, 65–73 (2015).

Pradeep, S., Sathish, M., Sreeram, K. J. & Rao, J. R. Melamine-based polymeric crosslinker for cleaner leather production. ACS Omega 6, 12965–12976 (2021).

Sizeland, K. H. et al. The influence of water, lanolin, urea, proline, paraffin and fatliquor on collagen D-spacing in leather. RSC Adv. 7, 40658–40663 (2017).

Chen, J., Ma, J., Fan, Q., Zhang, W., Guo, R. A sustainable chrome-free tanning approach based on Zr-MOFs functionalized with different metals through post-synthetic modification. Chem. Eng. J. 474, 145453 (2023).

Muhoza, B., Xia, S., Zhang, X. Gelatin and high methyl pectin coacervates crosslinked with tannic acid: the characterization, rheological properties, and application for peppermint oil microencapsulation. Food Hydrocoll. 97, 105174 (2019).

Wen, H., Wang, Y., Zhu, H., Jin, L., Zhang, F. A fluorescent tracer based on castor oil for monitoring the mass transfer of fatliquoring agent in leather. Materials 15, (2022).

Wei, C. et al. “One-for-all” on-demand multifunctional fluorescent amphoteric polymers achieving breakthrough leather eco-manufacturing evolution. Green. Chem. 27, 498–516 (2025).

Wei, C. et al. A “three-in-one” strategy based on an on-demand multifunctional fluorescent amphoteric polymer for ecological leather manufacturing: a disruptive wet-finishing technique. Green. Chem. 25, 5956–5967 (2023).

Hao, D. et al. A “wrench-like” green amphoteric organic chrome-free tanning agent provides long-term and effective antibacterial protection for leather. J. Clean. Prod. 404, (2023).

Yu, L. et al. Preparation of a syntan containing active chlorine groups for chrome-free tanned leather. J. Clean. Prod. 270, 122351 (2020).

Guan, X. et al. Remediation and resource utilization of chromium(III)-containing tannery effluent based on chitosan-sodium alginate hydrogel. Carbohydr. Polym. 284, 119179 (2022).

Yu, Y. et al. Life cycle assessment for chrome tanning, chrome-free metal tanning, and metal-free tanning systems. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 6720–6731 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support of Science and Technology Project of Quanzhou City (2024G03), National Natural Science Foundation of China (22478235), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (22078183, 22108165).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT authorship contribution statement. Shuang Liang: Methodology, Data curation, writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Xuechuan Wang: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Chao Wei: software and methodology. Long Xie: Validation. Xugang Dang: Conceptualization, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, S., Wang, X., Wei, C. et al. Chitosan based chromium free tanning system for reducing the carbon footprint to leather production process. npj Mater. Sustain. 3, 19 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44296-025-00062-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44296-025-00062-y