Abstract

The impact of various environmental factors on SARS-CoV-2 transmission remains debated, partly due to limited physical experiments with infectious virus that closely replicate real-world conditions. Using a novel, self-contained containment level 3 chamber, we aerosolized the virus in different environmental conditions then collected droplets on nasal tissue, cell lines, or different materials to measure the transmission of infectious SARS-CoV-2. We found that SARS-CoV-2 survival was much shorter than previously reported for the potential of fomite transmission. Temperature, relative humidity and the presence of incinerated tobacco, cannabis, or vape products had no discernible impact on SARS-CoV-2 transmission through aerosolized droplets, but affected the survival of VSV, a non-respiratory enveloped virus. When compared to USA-WA1/2020 and the Omicron variant, Delta SARS-CoV-2 had the greatest survival during aerosolization. These findings suggest that respiratory enveloped viruses like SARS-CoV-2 may have and may be continuing to evolve higher transmission fitness through droplets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to be a highly transmissible pathogen1,2,3, perpetuating a global challenge that demands real-world experimental studies to develop complex models of transmission. Expiratory activities, such as sneezing or coughing by infected individuals, generate various sizes of liquid “particles” carrying infectious virus “particles” (virions), contributing to the virus transmission3. There has been an inconsistency in the nomenclature of these “particles” in the medical and physics research fields. As describe herein, we adhere to the physics concept, labeling the diverse sizes of all liquid “particles” as “droplets” and dried forms as “dried particles” avoiding the conventional division into aerosols/droplet nuclei and droplets based on size4. A continuous spectrum of “particles” of varying sizes likely permeates the air during transmission, dynamically evolving due to processes such as evaporation and supersaturation5,6.

Central to the understanding of SARS-CoV-2 transmission is the behavior of virus-laden droplets, with their size playing a pivotal role. Larger droplets, characterized by diameters exceeding 100 µm, follow a nearly ballistic trajectory when generated by a cough or sneeze, due to their size and gravitational impact, settling quickly on surfaces in close proximity to the source (can reach to 2 m or more for coughing) before evaporation7,8,9. These large droplets can deposit on mucous membranes (such as eyes, nose, and mouth) of potential hosts who stand close to the infected individual, leading to droplet transmission. Furthermore, droplets may settle on indoor surfaces, such as doorknobs and table surfaces, and can be picked up by potential hosts and transferred to mucous membranes, causing fomite transmission. Smaller droplets, with diameters usually below 100 µm can stay suspended in the air, contributing to airborne transmission10. Numerous studies, including air sampling, animal models, simulations and epidemiological studies have shown that airborne transmission can happen over both short (<2 m) and long distances and could be the dominant transmission mode of SARS-CoV-211,12,13,14,15.

From the moment of aerosolization to the initiation of infection (e.g., in lungs), multiple environmental factors, including temperature, relative humidity (RH), fine particles, and surface materials, exert profound influences on the infectious fate of released virus-laden droplets, thereby shaping the transmission dynamics of the virus. Epidemiological studies suggest strong but controversial effects of temperature and RH on SARS-CoV-2 transmission 16,17,18,19. Mathematical models suggest a role of high RH and low temperature in evaporation, droplet stability, and size-dependent dynamics5,6,20, but these simulations only demonstrate the physical change of droplets in the transmission and imply an impact on virus infectivity, often based on non-enveloped bacterial phage studies21. The impact of these environmental factors on any enveloped virus is not well understood21,22,23,24,25, let alone the specific impact on different SARS-CoV-2 variants in air-suspended droplets.

Another intriguing, yet elusive, environmental factor that could affect SARS-CoV-2 transmission is the presence of fine particles in the air, such as PM from e.g., air pollution, surgical smoke26, or smoke particles. Epidemiological studies worldwide suggest an enhancement effect on SARS-CoV-2 transmission and COVID-19 mortality when air pollutants levels are high (e.g., >PM2.5)27,28,29 but there are conflicting results on the effects of “smoking” of tobacco, cannabis, or e-cigarettes (vaping)30,31,32,33. Fine particles, beyond their impact on the immune system and human behavior, may serve as potential vectors for virus transmission, particularly in poorly ventilated indoor environments34. There is little evidence implying whether fine particles from tobacco, including nicotine, glycol and heavy metals35, facilitate or impede the virus transmission36. The particles might change the physical properties of the droplets or interact with virions to elongate or shorten the lifespan of droplets and the viruses. Well-controlled conditions with comprehensive design are needed to establish effects of fine particles on virus transmission.

The effect of various material surfaces on SARS-CoV-2 was heavily investigated at the beginning of the pandemic but mostly with experiments involving the mechanical deposition of virus-laden droplets. Pipetting even the smallest volume would exceed that of most droplets settling on surfaces, impacting the survival of SARS-CoV-2 on different materials37,38,39. Furthermore, the microenvironment and physical characteristics of droplets may undergo changes during their airborne travel40.

To address the limitations mentioned above, an aerosolization chamber was designed and constructed in which the environmental conditions can be accurately controlled to investigate the transmission and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in droplets. Unlike previous studies focusing on specific droplet sizes, our approach examined the full spectrum of droplets generated by aerosolization, offering a comprehensive understanding of how temperature, RH, tobacco and cannabis particles affect multiple transmission modes through both small droplets lingering in the air and large droplets depositing on different surfaces. Using a combination of RT-qPCR for virus particle detection and limiting dilution infectivity assays, we observed faster growth of SARS-CoV-2 USA-WA1/2020 than the Delta and Omicron variants when aerosolized and collected on the Vero E6 cell line. Additionally, we incorporated a differentiated nasal tissue model with an air-liquid interface to closely mimic the actual conditions. When controlling for virus outgrowth kinetics, the Delta variant of concern had significantly greater airborne or fomite transmission following aerosolization. Our study not only advances our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 transmission but also lays the groundwork for evaluating other respiratory pathogens in the future.

Results

An aerosolization chamber generating various sizes of droplets was designed for studying SARS-CoV-2 transmission

To assess SARS-CoV-2 transmission, we devised a highly secure, safe, and easily decontaminated stainless steel aerosolization chamber (40 × 40 × 95 cm) tailored to fit within biosafety cabinets (BSC). Virus can be aerosolized at the nozzle (outside diameter = 0.25 in, inside diameter = 0.18 in, 25 cm above the bottom of the chamber, perpendicular to the endplate) on the left-hand side and droplets can be collected on sample collection trays (9 × 4 cm). These trays (also referred to as top and bottom trays) are sealed within the chamber and positioned adjacent to the top and bottom of the right-hand endplate (Fig. 1a–c). The nearest collection site for droplets on both trays is 86 cm from the nozzle. Equipped with 4 valves on the side, the chamber connects to external equipment outside the BSC, enabling adjustments to temperature and RH by pushing conditioned air through Whatman filters into the containment chamber from a heat gun/dryer, refrigeration unit, humidifier, or dehumdifier. Real-time temperature and RH readings are provided by a probe located at the center (Fig. 1a, b). Constant temperatures were maintained through external insulation of the chamber and/or a heating belt. Detailed pictures of the spray system are shown in Fig. 1f, g. There are 2 valves for loading material into the spray system and another eight valves designed for a burst of pressurized air flow with safety values to prevent backflow through the system. The location of the valves and the workstream are described in Fig. 1e.

a Isometric opaque view, b Isometric transparent view, and c Right-hand endplate CAD drawing of the aerosolization chamber. d Experimental setup within a containment level 3 biosafety cabinet (BSC). Viruses were loaded and aerosolized inside the BSC and samples were collected at right-hand side of the chamber. The air compressor and aerosolization control valves were located outside the BSC. The environmental control equipment was connected to the chamber through valves on the side of the chamber. e Engineering diagram of the aerosolization experiment setup. Valves 1 to 4 are connected to environmental controls, such as a humidifier, with 0.2 µm filters at the inlet and outlet for safety. A heating belt was wrapped around the chamber to provide heating. A temperature and relative humidity (RH) indicator were installed in the center of the chamber to monitor the real-time environmental conditions. Viruses were loaded into the system via a disposable syringe connected to valve 5. Valve 6 controlled the airflow direction and safety, while valves 7–9 managed the air charge and aerosolization. Smoke particulate matter was introduced via a disposable syringe connected to valve 10. Aerosolized droplets were collected on the top and bottom trays on the right-hand side of the chamber. The arrows show the airflow directions. f Photo of the virus loading area. g Photo of the air charge, aerosolization control, and smoke loading area. h, i Visualization of the spray pattern at the back of the chamber when aerosolizing 250 µL and 1 mL of bromophenol blue/phosphate buffered saline solution (PBS) at a gauge pressure of 35 psi. The red letters in the figure represent: a, b sample collection trays, c valve 1, d valve 2, e aerosolization nozzle, f temperature and RH indicator, g virus loading syringe, h humidifier, i dehumidifier, and j air compressor.

To determine the optimal aerosolization pressure, different volumes of bromophenol blue/phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) solution were loaded into the system from position/valve 5 and then sprayed into the chamber by releasing an air burst at 20, 35, and 50 psi gauge pressure from a compressor at valve 9. We then compared the spray patterns near the chamber endplate and on the sample collection trays by attaching vertical sheets of cellulose paper with polyethylene backing (referred to as cellulose paper) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The splaying of droplets on impact, coupled with the paper absorbance and the resolution of the scanner, limited the detection and quantification of the droplets to those greater than 0.2 mm in diameter. Video recording and analysis from the side during the aerosolization was employed to validate the observed spray patterns (Supplementary Movies 1–3). Aerosolizing with air burst of 20 and 35 psi gauge pressure, we observed scattered and various sizes of droplets. When establishing this system, we were testing multiple gauge pressures (ranging from 15 to 50 psi) to identify the pressure that produced scattered droplets of various sizes on the end plate (as well as on our collection trays, see below). Our goal was to determine the lowest gauge pressure that generated a spray pattern resembling human respiratory activities as closely as possible. While 15 psi produced a suitable spray pattern, the amount of infectious virus we could collect was near the limit of detection, making it difficult to observe meaningful differences. In contrast, 35 psi yielded both an optimal spray pattern and a measurable amount of infectious virus (see below).

A spray at 35 psi gauge pressure with 250 μL loading volume yielded droplets with diverse sizes that deposited on cellulose paper at the end plate (Fig. 1h). However, aerosolization of 1 mL of liquid with the same spray pressure resulted in much larger droplets that splattered near the bottom of the cellulose paper (Fig. 1i). These droplet sizes were significantly larger than those previous reports from a cough or sneeze and thus, we did not employ the spray of 1 mL in future experiments41. Droplets were collected on glass slides placed on the upper and lower trays to measure droplet sizes, volumes, and numbers. Glass slides were collected, imaged with light microscopy, with droplet sizes and numbers being determined using ImageJ (Fig. 2a–d). The total number of droplets (approximately 200–800, representing the 25 and 75th percentiles) per cm2 and droplet sizes (approximately 10–1000 µm in diameter) collected did not differ on glass slides placed on the top or bottom tray immediately after the spray (Fig. 2a, c). Based on micropippetting of defined volumes onto glass slides (Supplementary Fig. 2), we determined a regression model for cell culture medium droplet diameter to volume which was used for crude estimate of droplet volumes (approximately 10−10 to 10−8 µL, representing the 25 and 75th percentiles) (Fig. 2b) and total collected volume on the top and bottom slides (approximately 10−6 to 10−3 µL/cm2, representing the 25 and 75th percentiles) from 12 replicate sprays (Fig. 2d). The total estimated volumes of the spray onto entire material/cell cultures in the top and bottom tray are described in each figure legend. Please note that we were unable to determine the diversity of droplet volume or size during the time-of-flight, as we have previously described using Integrated Droplet Imaging System on droplets from a cough41. In future studies, diversity of virus-laden droplet dynamics (size, volume, velocity) will be more accurately analyzed in containment level 3 in a new 2.5 m3 chamber (under construction) and equipped with the LaVision Integrated Droplet Imaging System. Droplet sizes from a cough41 were similar to the diversity of droplets settling on the slide following the mechanical spray in the current chamber. This study was focused on the survival of SARS-CoV-2 survival following a spray/time-of-flight under different real world atmospheric, environmental, and man-induced conditions of transmission from a cough or light sneeze.

250 µL cell culture medium was aerosolized at 35 psi, under 18 °C–25 °C and 40–60% RH. Droplets were collected with microscope cover glasses (2.4 × 5 cm) 1 min after the aerosolization and visualized using a widefield microscope. The diameter of individual droplets was measured by ImageJ (a). The estimated volume of individual droplets (b) and the number of droplets per cm2 was quantified and calculated using ImageJ (c). The estimated total volume of droplets per cm2 (d) were calculated based on a non-linear regression model generated by pipetting known volumes of cell culture medium onto cover glasses (see Fig. S2). e, f Representative images of aerosolized droplets collected from cover glasses placed on the top and bottom trays. The red arrows indicate droplets. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. In (a, b), data represent all individual droplets pooled from independent aerosolizations: n = 10 for the top tray, n = 12 for the bottom tray. Geometric mean±geometric SD is shown in (a). Tukey-style box plot is shown in (b–d), with whiskers extending to 1.5 × IQR; outliers are shown as individual points.

Next, we aerosolized 106 infectious unit (IU) of vesicular stomatitis virus (Indiana strain) expressing green fluorescent protein (VSV-GFP), which is designated a containment level 2/biosafety level 2 virus in Canada and the US, respectively. VSV is “bullet shaped” at ~70 × 200 nm while SARS-CoV-2 is more spherical in shape at 100 nm in diameter42,43. Rice paper is comprised of rice starch, gelatin and a small amount of lecithin, which are materials previous shown to stabilize most enveloped and non-enveloped virus particles. To determine the amount of infectious virus collected, three 2 x 2 cm rice paper squares were placed on the top and bottom trays and were removed 1 min after aerosolization at room temperature. This waiting time allowed aerosolized droplets to settle onto the rice paper while reducing exposure risk. The rice paper squares were then soaked in the cell culture medium for 20 min allowing rice paper to dissolve. Infectious virus titer was then determined by standard 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay using serially diluted virus/rice paper solution (Fig. 3a). A greater amount of infectious VSV-GFP was recovered on rice paper placed on both the top and bottom trays after a spray at 35 psi versus 15 psi at room temperature (18 °C–25 °C) (P = 0.0238 for the top tray and P = 0.0079 for the bottom tray) (Fig. 3b, c). The amount of infectious VSV-GFP collected following aerosolization at 15 psi was near the limit of detection, making it difficult to detect meaningful differences. Therefore, all subsequent experiments in this study were conducted at 35 psi.

a Schematic representation (created with BioRender.com) of the aerosolization experiments. 3 pieces of rice paper or other collection materials (different surfaces, Vero E6, or nasal tissue) were placed on the top and bottom trays (both trays, identical in size, were placed adjacent to the right-hand endplate), and the virus was aerosolized at 35 psi. 1 min after the aerosolization, collection material squares were retrieved from the chamber and soaked in 3 mL cell culture medium for 20 min, allowing the virus to dissolve. The dissolved solution was titrated by 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay on Vero E6 with GFP used for VSV-GFP and nucleocapsid antibody staining for SARS-CoV-2 to measure infectious virus recovery. VSV-GFP was aerosolized under both 15 and 35 psi to decide the optimal aerosolization pressure, and droplets were collected on rice paper and titrated from the top (b) and bottom (c) trays. 104 infectious units (IUs), 105 IUs and 106 IUs of VSV-GFP were aerosolized to determine the optimal aerosolization amount, and droplets were collected and titrated from the top (d) and bottom (e) trays. f Schematic representation of time points for aerosolization experiments. Aerosolization of 106 IUs of VSV-GFP with droplets collected at different time intervals from the top (g) and bottom (h) trays. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test (b, c) and the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (d, e, g, h). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. The dotted line indicates the lower limit of detection (6.61 TCID50/mL). Each data point was from one aerosolization. Geometric mean is shown.

We also determined the amount of VSV-GFP virus that needed to be sprayed for optimal infectious virus recovery from aerosolized droplets. A significantly higher infectious virus yield was consistently collected from the top and bottom trays when aerosolizing 106 IUs of VSV-GFP when compared to sprays of 105 and 104 IUs (Fig. 3d, e). Thus, the following studies with SARS-CoV-2 (at containment level 3) employed aerosolization at 35 psi loading 106 IUs virus.

Prior to use of SARS-CoV-2 under highly stringent and safety-regulated conditions, we validated that our spray system could generate a diversity of virus-laden droplets consistent with a cough or sneeze. (Fig. 3f)7,8,10. Using a spray at 35 psi, with volume of 250 μL, and 106 IUs of VSV-GFP at room temperature, we collected the droplets settled on rice paper on the top and bottom trays at defined time intervals. The first collection was performed 5 s post-spray by removing the rice paper. Fresh rice paper was immediately placed on the trays, and additional collections were conducted at 2.5, 5, and 15 min post-spray by replacing the rice paper at each interval. This sequential collection approach allowed us to capture droplets settling during distinct time intervals, with the cumulative collection representing the total droplets settled by 15 min post-spray. The majority of sprayed infectious virus was collected within the first 5 s but with more depositing into the bottom tray than collected in the top tray, suggesting larger droplets immediately falling with gravity. Between 5 s and 2.5 min, as much infectious virus was found from the top and bottom tray. Infectious virus was still collected from the top tray at 5–15 mins post spray but no infectious virus was detected after 5 min in the bottom tray (Fig. 3g, h). By 15 min, we discovered that the droplets in both trays had evaporated to the extent that the virus was no longer viable. However, in two of five sprays, the top tray retained residual infectious VSV-GFP after 15 min whereas bottom trays lacked any infectious virus from the five repeat sprays. This difference was not significant. The upper tray was more in line with the nozzle and the trajectory of the spray as compared to the lower tray. Thus, the upper tray largely collected droplets directly from the initial spray or suspended droplets that remained in the air following the spray. The lower tray received a fraction of the initial sprayed droplets (based on spread of the spray) but a large proportion was from those droplets settling at the end of the chamber into this lower tray over 5 s following the spray (Fig. 3h).

Effect of temperature and relative humidity on survival of SARS-CoV-2 in aerosolized droplets

Based on past outbreaks of respiratory viruses, assumptions were made that SARS-CoV-2 would follow past trends with outbreaks mostly coinciding with “shoulder” seasons22. In real-world epidemiological studies, there appears to be minimal seasonal effects and impact of temperature and RH on SARS-CoV-2 transmission but this has been difficult to confirm experimentally. VSV-GFP was first aerosolized under a range of experimental temperatures (4 °C–36 °C) and RH (30–90%) in the chamber to determine the effects of virus infectivity. There was no significant impact of temperature on VSV-GFP survival upon aerosolization but there was a trend for higher levels of infectious virus recovery from sprays at 25 °C as compared to 4 °C and 36 °C in the chamber (Fig. 4a–f). With VSV-GFP, there was, however, a direct correlation between the RH levels and infectivity of droplets collected from the bottom tray, not observed with droplets collected from the top tray (Fig. 5c, d). These results suggest that survival of VSV-GFP in droplets with aerosolization is influenced by both temperature and RH.

106 IUs of VSV-GFP was aerosolized at various temperatures (4 °C, 25 °C and 36 °C) and relative humidity (RH) (30, 60, and 90%). Droplets were collected on rice paper from the top and bottom trays. Under 18–25 °C and 40% < RH < 60%, the estimated volume collected was 7.9 × 10-4 μL for the top tray and 3.8 × 10-4 μL for the bottom tray. a–f Quantification of infectious virus recovered from rice paper when VSV-GFP was aerosolized at various temperatures with 30, 60, and 90% RH (n = 5). Statistical significance was determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The dotted line indicates the lower limit of detection (6.61 TCID50/mL). Each data point was from one aerosolization. Geometric mean is shown.

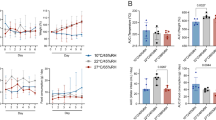

106 IUs of VSV-GFP or SARS-CoV-2, including USA-WA1/2020, Delta, and Omicron, were aerosolized at 18 °C–25 °C at different relative humidity (RH) ranges. Droplets were collected on rice paper from the top and bottom trays. Under 18 °C–25 °C and 40% < RH < 60%, the estimated volume collected was 7.9 × 10-4 μL for the top tray and 3.8 × 10-4 μL for the bottom tray. a, b Quantification of infectious USA-WA1/2020 recovered from rice paper. c, d Quantification of infectious VSV-GFP recovered from rice paper when aerosolized at 25 °C with varying RH levels. e, f Comparison of virus recovery from rice paper when SARS-CoV-2 or VSV was aerosolized under extreme environmental conditions (cold at 4 °C, or hot at 36 °C and dry RH < 50% or humid RH > 70%). g, h Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 strains recovered from rice paper when aerosolized under 60% < RH < 70%. Statistical significance in (a–d, g, h) was determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test or the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test (e and f). Two-tailed Pearson correlation analysis was performed in (c, d) to evaluate the relationship between the quantity of recovered infectious virus (TCID50/mL) and RH. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. The dotted line indicates the lower limit of detection (6.61 TCID50/mL). Each data point was from one aerosolization. Geometric mean is shown.

Unlike VSV-GFP, when 106 IUs of SARS-CoV-2 USA-WA1/2020 (Wuhan strain) was sprayed at 35 psi at room temperature, infectivity was not RH-dependent (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3). When aerosolizing different strains, SARS-CoV-2 Delta consistently exhibited significantly higher infectivity than USA-WA1/2020 and Omicron BA.1 at 60–70% RH at room temperature and RH < 70% (Fig. 5g, h). We then compared aerosolizing Delta and VSV-GFP under extreme conditions (cold at 4 °C or hot at 36 °C, and dry RH < 50% or humid RH > 70%). Consistent with Fig. 4, more infectious VSV-GFP was recovered in humid versus dry conditions, especially at cold temperatures (Fig. 5e, f). In contrast, the amount of infectious SARS-CoV-2 Delta collected droplets was similar in all extreme conditions of humidity and temperature (Fig. 5e, f). As discussed later, these finding suggest that SARS-CoV-2 may be more “resistant” to differential atmospheric conditions than VSV-GFP. Thus, VSV may not have evolved to maintain higher efficiency aerosolized transmission.

Aerosolization of SARS-CoV-2 on Vero E6 cells and nasal tissue

As described above, we adopted a collection on rice paper from droplets collected from the top and bottom trays for VSV-GFP and SARS-CoV-2 and then TCID50 determinations to measure the infectious titer, which established the methodologies and conditions for virus aerosolization and a comparison between two enveloped viral species, one adapted to transmission through bodily fluids and the other to respiratory transmission, respectively. To closely emulate real-world conditions for SARS-CoV-2 transmission, we aerosolized in the chamber and determined infectious potential directly on Vero E6 cells or on human nasal tissue placed in the top and bottom trays. The aerosolization process spanned various conditions, including cold and dry, cold and humid or room temperature and humid conditions. With these analyzes, we analyzed the level of inoculating virus at the time of tray removal (Fig. 6a, b) and the level of virus growth kinetics in spray-exposed Vero E6 cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 over 48 h. The growth rate curves in fold change and virus copy numbers decided by RT-qPCR are shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 respectively. For comparison, we determined the area-under-the-curve (AUC) (Fig. 6c, d).

104 IUs of SARS-CoV-2 were aerosolized at cold & dry, cold & humid and room temperature & humid conditions (cold at 4 °C, or room temperature at 18 °C-25 °C, and dry RH < 50% or humid RH > 70%). Droplets were collected on Vero E6 cells (2 × 105 cells in 10 cm2 area) from the top and bottom trays. Under 18–25 °C and 40% < RH < 60%, the estimated volume collected was 6.6 × 10-4 μL for cells on the top tray and 3.2 × 10-4 μL for cells on the bottom tray. The supernatant from Vero E6 cell cultures was collected at 0, 24, 32, 36, 44, and 48 h post-aerosolization. RNA was extracted from the supernatant for RT-qPCR analysis targeting the SARS-CoV-2 N gene, allowing for the monitoring of viral growth. a, b The quantification of SARS-CoV-2 deposited on Vero E6 cells was compared using the RT-qPCR results from the supernatant collected immediately after aerosolization (n = 7). Geometric mean is shown. c, d The areas under the curves were calculated from the viral growth curves in fold change characterized by RT-qPCR (n = 4). Geometric mean is shown. e An example of SARS-CoV-2 virus growth curves in fold change after aerosolization, from suspended droplets aerosolized under cold and dry condition (n = 4). Mean and standard error of the mean are shown. f A 1 mL solution containing 400 IU/mL of SARS-CoV-2 was inoculated on Vero E6 cells without aerosolization and the supernatant was collected at different time points for RT-qPCR to characterize growth curves. Mean and standard error of the mean are shown. Statistical significance was determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (a–d). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. AUC area under the curve.

Supernatant collection from the Vero E6 cultures in the tray, immediately following the spray (1 min), provided insights of virus particle counts (based on RT-qPCR) falling onto Vero E6. Following aerosolization, there were significantly lower amounts of USA-WA1/2020 virus particles collected in the cell cultures on the top and bottom trays compared to those for Delta and Omicron (Fig. 6a, b). This observation is consistent with collection of higher quantities of infectious Delta over USA-WA1/2020 from droplets on the top and bottom trays on the rice paper (Fig. 5a, b, g, h). However, with aerosolization of these SARS-CoV-2 strains, the smaller droplet inoculum of USA-WA1/2020 resulted in greater outgrowth on Vero E6 over 48 h than observed with Delta or Omicron SARS-CoV-2, despite higher deposition of these viruses by the droplet inoculum from the spray (Fig. 6c, d). To test for possible differences in replication kinetics, we directly added the same amount of IUs of USA-WA1/2020, Delta, and Omicron to Vero E6 and monitored virus outgrowth for the same time period. USA-WA1/2020 replicated faster than Delta and Omicron consistent with the results observed in Vero E6 cell following spray inoculation (Fig. 6f, and Supplementary Fig. 6). These findings suggest that when spraying the same amounts of USA-WA1/2020, Delta, and Omicron in the different atmospheric conditions, Delta has a higher survival in droplets during the time-of-flight than USA-WA1/2020 or Omicron. In our studies and many others, inaccurate values of survival upon aerosolization could be provided if the infectivity was scored based on subsequent growth rates of the virus strains as opposed to the actual infectivity scored by limiting dilution/infectivity assay. This is simply because despite Delta have higher survival rates upon aerosolization, it has slower replication rates than USA-WA1/2020 (or Omicron) during virus propagation. Limiting dilution addition of SARS-CoV-2 (e.g., collected from dissolved rice paper) to a 96-well plate containing Vero E6 cells provides an accurate tool to determine quantity of infectious viral units (via standardized TCID50 assays). However, Vero E6 cells is a cell line (derivative of African green monkey kidney epithelial cell) and not an actual cell that would be infected in the human respiratory tract or would contribute to subsequent pathogenesis.

Based on the limitations described above, SARS-CoV-2 was aerosolized in the chamber and collected in trays containing differentiated human nasal epithelial cells. The nasal epithelium, the primary site for SARS-CoV-2 entry, expresses high levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the virus’s cellular receptor, making it ideal for testing infection and transmissibility44,45. We have established a nasal organotypic model with an air-liquid interface46 which recapitulates multiple physiological features of the nasal mucosa, including a ciliated mucosal apical surface. Using our chamber, Delta and Omicron (106 IUs) were aerosolized under humid conditions at either 4 °C or room temperature. The nasal tissue place in the top and bottom trays was exposed to aerosolized droplets for collection and analysis. Using reconstituted human nasal tissue derived from donors, we could not quantify the inoculating spray dose on the tissue in the top or bottom trays as we were able to when using the rice paper or the Vero E6 cells. This could relate to the ciliated, mucus layer on the apical surface of this tissue reducing virus detection. At 48 h post-spray, RNA was extracted from the lysed tissue for RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 7a). There was no difference in virus infectivity by Delta and Omicron within droplets collected from the top and bottom trays when the spray was conducted at room temperature and high humidity. In the cold and humid condition, Delta appeared to have higher transmission to nasal tissue through aerosolization compared to Omicron. The higher transmission fitness of Delta was most notable with a virus spray and then measurement of the virus survival/infection on human nasal tissue (Fig. 7b–e).

106 IUs of SARS-CoV-2, was aerosolized under cold & humid and room temperature & humid conditions (cold at 4 °C, or room temperature at 18 °C −25 °C, and humid RH > 70%). Droplets were collected on human nasal tissue in transwells (0.33 cm2 per well) on the top and bottom trays. Under 18 °C–25 °C and 40% < RH < 60%, the estimated volume collected was 2.2 × 10-5 μL for tissue on the top tray and 1.0 × 10-5 μL for tissue on the bottom tray. Tissue RNA was extracted for RT-qPCR targeting RPLP0 and the SARS-CoV-2 N gene 48 h after aerosolization. a Schematic representation (created with BioRender.com) of the aerosolization on nasal tissue experiments. b–e RT-qPCR results. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann-Whitney test. Data were from one donor. Each data point was from one aerosolization. Geometric mean is shown.

Effect of smoke on SARS-CoV-2 transmission

In poorly ventilated indoor space, fine particles from tobacco or cannabis raise concerns as potential vectors for virus transmission34. Despite the controversial findings on the relationship between smoking and COVID-1930,31,32,33, the impact of smoke particulate matter (SPM) on virus transmission remains unknown. Thus, we assessed the influence of particulate matter (PM) from incinerated tobacco, cannabis, and nicotine-containing solution in E-cigarettes/vape pens on SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The studies described below examined a model for transmission from a smoker where the inhaled smoke PM would combine SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs or nasal passage during exhalation. First, the impact of SPM on viral infectivity was analyzed. Smoke was inhaled from a tobacco cigarette, cannabis cigarette (“joint”), or vape pen containing a nicotine solution and then exhaled onto pre-wetted 40 µm filter paper (see Methods). The PM from this smoke were washed off with a 3 mL cell culture media containing 103 IU/mL VSV-GFP (or SARS-CoV-2). The smoke/VSV-GFP solutions were serially diluted and used to infect Vero E6 cells for a TCID50 measurement (Fig. 8a). No significant difference in VSV-GFP infectivity was observed when mixed with the SPM from incinerated cannabis, tobacco, or the nicotine-containing vape solution (Fig. 8b). The same observations were made when mixing smoke with USA-WA1/2020 but performed only in duplicate (data not shown). Next, to simulate exhalation from a SARS-CoV-2 infected individual at the time of smoking these materials, the smoke of incinerated vape solution, cannabis, or tobacco was aerosolized along with SARS-CoV-2 (USA-WA1/2020, Delta, and Omicron) or VSV-GFP at room temperature and humid conditions. Please note that for this experiment, the smoke was drawn up through a 50 ml syringe secured to the end of the incineration device containing one of the three products, representing the exhaled long volume of one long “drag”, e.g., 20% of the material (e.g., tobacco) in a cigarette. The subsequent steps of virus loading, aerosolization, and sample collection were conducted according to the previously described procedures (Figs. 1, 3). To simulate exhalation, the smoke in the 50 mL syringe was then loaded into the aerosolization pipeline by opening valve 10 and pressing down the plunger filling the tubing between valves 6 and valves 7/8 (Fig. 1e). Valve 8 being the pressure release valve accommodating the smoke volume. The virus was then mixed into same pipeline containing the smoke by opening valve 5 and plunging the in the media containing virus for approximately 2 min prior to spray (Fig. 1e). The spray was then performed as described above. Analysis revealed no significant differences in the amount of infectious virus collected (any SARS-CoV-2 strains or VSV) in droplets collected from the top and bottom trays following aerosolization of any of the virus strains with any of the smoke types (Fig. 8c, d, and Supplementary Fig. 7). However, there was trend for increased infectivity upon aerosolization with smoke, most notable with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron.

Particulate matter from the smoke from nicotine-containing vape solution, cannabis and tobacco exhalation from both the mouth and lungs were collected on pieces of filter paper. The filter papers were washed by 103 IU/mL VSV-GFP solution to ensure interaction between VSV-GFP and the smoke particulate matter. The virus solution after wash was then titrated to assess the impact of smoke particulate matter on virus infectivity. a Schematic representation (created with BioRender.com) of the smoke particulate matter collection experiment. b Quantification of infectious VSV-GFP after interacting with smoke particulate matter without aerosolization (n = 5). 106 IUs of VSV-GFP or SARS-CoV-2 were aerosolized with different smoke fine particles at room temperature (18 °C –25 °C). Droplets were collected on rice paper from the top and bottom trays. Under 18–25 °C and 40% < RH < 60%, the estimated volume collected was 7.9 × 10-4 μL for the top tray and 3.8 × 10-4 μL for the bottom tray. c, d Recovered infectious Omicron in suspended and settled droplets deposited on rice paper (n = 8). Statistical significance was determined using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. The dotted line indicates the lower limit of detection (6.61 TCID50/mL). Geometric mean is shown. Schematics created with BioRender.com. Each data point was from one aerosolization.

SARS-CoV-2 viability on different surfaces after aerosolization

Understanding the survival of viruses on different materials is key to assessing fomite transmission efficiency and its implications for public health. Prior studies have extensively examined the lifespan of SARS-CoV-2 on different surfaces by pipetting a small volume (no less than 1 µL) of virus solution37,38,39. However, the properties of droplets generated by aerosolization versus pipetting will likely be different, the most obvious being the smaller size and larger number of aerosolized droplets that can settle onto a surface and that can be accessed by a single finger or by hand touch. Furthermore, the physicochemical properties acting on virus-containing droplets is governed in part by droplet composition, volume, and contact area upon settling on the surface following aerosolization40. The electrostatic interactions, the surface structures, and the chemical composition of the material can impact the evaporation rate and the absorbance can impact the virus survival in the droplets. Finally, there may also be direct viricidal activity of the material.

To address survival of the virus upon droplet deposition onto surfaces from aerosolization, 106 IUs VSV-GFP was sprayed in the chamber at room temperature and 30% RH with the droplets collected on common household materials placed on the bottom tray, still microscopic and a least one to two orders of magnitude smaller in volume than a pipetted droplet. After spray and collection, the materials were either immediately washed with cell culture medium (~1 min in expended time) or left exposed to air for 20 or 60 min at room temperature (Fig. 9a). Supplementary Fig. 8 shows the morphological changes of droplets immediately after aerosolization and during the desiccation on the materials over time. The droplets left behind crystalline material upon desiccation occurring on a microscope cover glass and not observed on other materials. Absorbent organic materials, like rice paper, slices of beef, and 1.2 mm corrugated fiberboard, result in varying rates of droplet absorption, which was not observed in the non-absorbent materials: steel, copper, and microscope cover glass, or synthetic polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. When accessing virus infectivity on these materials after aerosolization, the control VSV-GFP virus in droplets collected from the bottom tray appeared to have a longer lifespan on stainless steel, microscope cover glass, and PVC plastic, when compared with absorbent, organic materials. Following aerosolization in the chamber, SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron survived longer and had higher amounts of infectious virus when the droplets settled on stainless steel and PVC plastic than even on the rice paper (Fig. 9c–e). Aligning with previous findings37, copper demonstrated exceptional antiviral properties, rapidly inactivating the virus in the aerosolized upon contact with the surface (Fig. 9b–d), even greater and more rapid inactivation than observed with the virus-containing droplet pipetted onto the same copper surface (i.e., larger volume).

106 IUs of VSV-GFP or SARS-CoV-2 were aerosolized at room temperature (18 °C–25 °C) with 30% relative humidity (RH) for VSV-GFP and 60% RH for SARS-CoV-2. Droplets were collected on rice paper, beef slice, galvanized steel, stainless steel, copper, microscope cover glass, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic and 1.2 mm corrugated fiberboard from the bottom tray. Collection materials were retrieved from the chamber 1 min after aerosolization and washed with cell culture medium immediately or left to air-dry for 20 or 60 min. a Schematic representation (created with BioRender.com) of the surface collection experiments after aerosolization. b Quantification of infectious VSV-GFP recovered from various surfaces at different times after aerosolization (n = 5). Geometric mean and standard deviation are shown. c Quantification of infectious Delta and Omicron recovered from various surfaces 1 min post-aerosolization (n = 6). Geometric mean is shown. d Quantification of infectious SARS-CoV-2 (Delta and Omicron combined) recovered from various surfaces 1 min post-aerosolization. Geometric mean is shown. e Quantification of infectious Delta recovered from rice paper and PVC plastic 1 min post-aerosolization or after 60 min of air-drying (n = 6). Geometric mean and standard deviation are shown. Statistical significance was determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (B-D) and the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test (e). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. The dotted line indicates the lower limit of detection (6.61 TCID50/mL). Each data point was from one aerosolization.

Discussion

In our investigation, we tested the effects of various environmental conditions, including temperature, RH, presence of smoke, and fomites, on their potential impact on virus survival during aerosolization/spray and time-of-flight while also examining transmission to susceptible cell lines or nasal tissue. We developed a system capable of generating aerosolized droplets of heterogeneous sizes, thereby simulating the proximal transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Distinguishing itself from other research that often focuses on a single transmission route, our chamber allows for flexible adjustment of the aerosolization’s initiation (virus loading and aerosolization conditions), duration/time-of-flight (environmental conditions), and termination (contacting surfaces and time). With this system, we have a comprehensive model that is ideal for studying pathogen transmission via sprayed droplets. In testing the viability of SARS-CoV-2 in “cough” droplets that might be inhaled or touch transferred from a surface, our current studies are collecting ~10-3 μL on the upper and/or lower tray representing 0.0004% of what was sprayed. In our experience, droplets are more rapidly desiccated when collecting suspended droplets by suction only cellulose-based materials through air sampler, reducing the viability of collected viruses. Following a spray, virus infectivity is better retained in droplets collected on cellulose-based materials on trays under the specific environmental conditions when immediately transferred/diluted into media/cell culture to assess infectivity (within 5 s of the spray). Droplet collected in the top tray represents those droplets falling on the upper tray from the downward trajectory of the spray, those falling with gravity over the upper tray, and those suspended in the air. This would be somewhat similar to inhalation of droplets within the path of someone who may have coughed or sneezed.

In contrast to previous studies on other airborne-transmitted viruses, our findings showed limited effects of temperature and humidity of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by sprays/aerosolizations47,48,49,50. Multiple epidemiological studies and mathematical transmission models focusing on SARS-CoV-2 suggest that environmental conditions would play an important role on transmission6,16,17,18,19,20. However, these models are often based on SARS-CoV-2 spread in the human population and, thus, are misleading in terms of the dynamics and efficiency of aerosolized transmission. With spread in the human population, the extremes of environmental conditions, high and low humidity and/or temperatures often result in people spending more time indoors with more moderate temperatures/humidities but reduced air flow and often with limited air filtration51,52. Indoor transmission can be 2-fold higher than outdoor transmission rates53,54. In this study, we observed that survival of aerosolized/sprayed SARS-CoV-2, especially the Delta variant, was unaffected by the extreme temperatures and humidity of a temperate climate zone (e.g., North America and northern Europe). In contrast to the relative stability of SARS-CoV-2, increasing survival of sprayed VSV in the same chamber correlated with increasing temperatures and humidities, i.e. with the highest survival observed at temperatures and conditions for optimal replication within most mammals (e.g. ~36-40 °C and 100% RH). VSV is similar in size to SARS-CoV-2, with a lipid bilayer membrane surrounding a protein core housing the RNA genome. Unlike SARS-CoV-2, VSV is primarily transmitted through touch transfer (direct contact between fluids of infected animals or through fomites), infecting skin, the oral and nasal cavities, and hooves/paws of mammals55 but rarely disseminates to the respiratory tract.

More studies on the biophysical properties of the SARS-CoV-2 (versus e.g., VSV as the comparator) are needed. For example, does membrane composition help to stabilize and retain the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 under various environmental conditions during time-of-flight in droplets. As an example, coldwater fish viruses can avoid freeze/thaw conditions by incorporating cellular antifreeze glycoproteins with their associated lipids and cholesterol into the virus membrane during virus assembly thereby inheriting an antifreeze phenotype56,57. Long term survival (months) at freezing temperatures in fresh and sea water has been demonstrated with Siniperca chuatsi Rhabdovirus (SCRV), a significant fish pathogen58. With the respiratory, airborne influenza A virus, cholesterol content and specific lipid composition in the viral membrane, which enhance stability and prevents dehydration59,60. For example, the influenza virus particles have mostly phosphatidylethanolamine in their membranes, whereas phosphatidylcholine is predominant in the cell membranes that produce this virus61. Very little is known about the lipid composition of SARS-CoV-2, let alone the differences among variants. One study did suggest that acylation of the spike protein’s cytosolic domain in the Golgi results in an ordered cholesterol and sphingolipid-rich rafts surrounding the spike, which are thought to be carried through to the viral membrane of the budding SARS-CoV-2 particles62. Impact of these lipids and cholesterol on SARS-CoV-2 stability under various environmental conditions and aerosolization should be an important focus of future studies.

Epidemiological studies suggest that pollution/PM (e.g., SPM) were associated with the rapid rise of COVID-19 cases early in the pandemic29,63,64. Exposure to smoke and other fine particles can upregulate ACE2 expression in the respiratory tract (mainly in the lung) and, therefore, increase host susceptibility to the virus65,66,67. There is the other possibility that SPM could act as a vector to carry and possibly “protect” virus during airborne transmission68,69,70,71. Within droplets, SPM could stabilize virus through enhanced adsorption and aggregation72 or alternatively, result in reduced survival due to loss of viral membrane integrity or lyses73. None of these population-based or biophysical studies have identified how virus mixed with smoke survives during the time-of-flight from a spray. Our studies provide a system to mimic exhalation of cannabis, tobacco, and nicotine vapor from a “smokers” lungs, infected with SARS-CoV-2, then examining the potential effects on virus infectivity during its passage through the air, i.e. before it hits a recipients’ respiratory tract. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the effects of SPM on SARS-CoV-2 survival during a spray. Our results suggest that the SPM of tobacco, cannabis, and vaporized nicotine have a very minor effect to increase SARS-CoV-2 survival upon aerosolization/spray but we did not observed any subsequent effects on the infectivity of ACE2-expressing cells. In future studies, we will be repeating these studies using human nasal tissue as receptacle of transmission and varying conditions for spray/aerosolized with SPM. We will focus on the cumulative effects of aerosolized SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of smoke and measure droplet suspension times in the chamber. This would provide a potential model of transmission from a SARS-CoV-2-infected individual smoking a cigarette in close proximity to an uninfected individual.

Previous studies suggested that SARS-CoV-2 could remain infectious for hours to days on different surfaces, with a half-life on plastic estimated at 6–8 h37. However, our findings indicate a significant drop in infectious SARS-CoV-2 (or control VSV) titers during the first hour of droplets settling of PVC plastic and stainless steel following a spray. This discrepancy may be attributed to the finer droplets generated during aerosolization, which distribute more evenly over a surface compared to a small volume of virus solution applied by pipetting in most studies. The total volume of a settled droplet versus a pipetted droplet is between 10 to >10,000 fold smaller. Faster evaporation rates, increases in salt concentrations, and shorter time to desiccation of settled droplets versus pipetted droplets were observed. Almost immediate inactivation of infectious SARS-CoV-2 was observed with settled droplets on copper surfaces following sprays. The anti-microbial property of copper is well described74,75 and is based on the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon water contact76. ROS will diffuse within a droplet to inactivate an enveloped virus like SARS-CoV-2, primarily by lipid peroxidation or oxidation of various amino acids to modify the surface protein structures/function, e.g., oxidation of cysteines to sulfenic acid77,78. Thus, ROS will require longer times to diffuse from a copper surface through a larger, versus a smaller, droplet to inactivate the virus. These results underscore the shorter survival time of SARS-CoV-2 in aerosolized droplets settled on different material surfaces compared to previous findings using the direct deposition of larger droplets with pipetting37, highlighting the need to employ the same biophysical conditions related to aerosolized droplet deposition when evaluating potential fomite transmission.

Methods

Ethics statement

Use of human nasal tissues was approved by the Western University Research Ethics Board (protocol 119682).

Virus propagation and quantification

VSV-GFP (Indiana serotype) was kindly provided by Dr. Byram Bridle from Guelph University79. It was propagated in Vero E6 cells (ATCC, USA) with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Wisent Inc, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS [Wisent Inc, USA]) and 100 units/mL Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S [Gibco, USA]) (DMEM complete medium). Virus was subsequently titrated by TCID50 assay using the green fluorescence signal. TCID50 titer calculation was performed using the Spearman–Kärber method80. TCID50/mL was converted to IU/mL by TCID50/mL × 0.7, which represents the actual number of infectious virus particles.

USA-WA1/2020 (hCoV-19/USA-WA1/2020 [NR-52281]) and Delta (hCoV-19/USA/PHC658/2021 [NR-55611]) were obtained from Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository (BEI Resources). Omicron (BA.1) was obtained from the BC Center for Disease Control (BCCDC) Public Health Laboratory. All stains were propagated in Vero E6 cells using DMEM complete medium and titrated via TCID50, staining nucleocapsid protein with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated monoclonal antibody (Cat # bsm-41411M-HRP, Bioss, USA)81. Titer calculation was performed using the Spearman–Kärber method80.

SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid staining for titration

Within a containment level 3 (CL3) biosafety cabinet (BSC), the medium was removed from the 96-well TCID50 plate. 200 μL of 10% formaldehyde was added in each well to inactivate the virus and the plate was incubated at 4 °C for 24 h. The procedure continued in a CL2 + BSC. The formaldehyde was removed and each well was washed with 200 μL of PBS. 150 μL per well fresh permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton/PBS) was added and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The plate was then washed a second time with PBS. 100 μL per well blocking solution (3% non-fat milk/PBS) was added to block the plate at room temperature for 1 h. Following removal of the blocking solution, 50 μL per well SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (1C7) HRP conjugated monoclonal antibody ([1 μg/mL] bsm-41411M-HRP, Bioss, USA) in 1% non-fat milk/PBS was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The plate was then washed with PBS twice and dried on paper towels. 100 μL per well SIGMAFAST™ OPD (Sigma-Aldrich, Canada) water solution was added and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 10–12 min to develop. The reaction was stopped by 50 μL per well of 3 M hydrochloric acid and the optical density was measure at 490 nanometers81.

Chamber environmental conditions adjustment

To lower the temperature of the air inside the chamber, a system was constructed whereby air was circulated through a container filled with dry ice and subsequently pumped into the chamber through a filter. To increase the internal temperature, a barrel heat belt (YSJWAER, Canada) was wrapped around the chamber and secured using aluminum foil tape (Fig. 1). The air temperature was monitored in conjunction with humidity utilizing a disposable electronic temperature and RH probe (Zoo Med, Canada) sealed into the center of the chamber. The relative humidity (RH) in the chamber was adjusted between 30% and 90% by circulating humidified or dehumidified air through a house-grade humidifier or de-humidifier fitted with a sealed air circulation loop (Fig. 1). Once the temperature and RH inside the chamber were adjusted to their test values, the chamber was sealed and the aerosolization experiments proceeded immediately. This protocol was repeated between each replicate to ensure that the air temperature was maintained.

Virus loading and aerosolization

For all experimentation, the chamber was housed in a B2 vented laminar flow hood within a containment level 3 (CL3) negative pressure facility, certified by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). The instrumentation and procedures were then approved by the Biosafety Committee at the University of Western Ontario, regulated by PHAC. A volume of 250 μL of 106 IU virus (or an adjusted volume for a lower titer) in DMEM complete medium was loaded in the barrel of a 5 mL syringe connected with the aerosolization nozzle, and the virus solution was slowly depressed into the stainless-steel line connecting the air compressor to the chamber. The medium was aerosolized by 35 psi gauge pressure air generated by an air compressor. To ensure unidirectional air flow and avoid possible contamination, valves were placed between all the input devices for a one-direction spray. Following every ten aerosolization experiments, a “medium alone” calibration aerosolization was performed to ensure an even distribution of droplets at the collection area to prevent possible “clogging” events. All the experiments involving SARS-CoV-2 were conducted in a CL3 lab, and those involving VSV-GFP were conducted in a CL2+ lab.

Sample collection and evaluation

Before aerosolization, three 4 \({{cm}}^{2}\) squares of rice paper or other collection materials (beef slices, galvanized steel, stainless steel, copper, microscope cover glass, PVC plastic and 1.2 mm corrugated fiberboard) were placed on sample collection trays (9 × 4 cm). Two chamber mounting trays, positioned 5 and 23 cm above the chamber floor, were attached to the top and bottom of the right-hand endplate. These chamber mounting trays can be slid in and out of the chamber, serving as the base for holding sample collection trays. The sample collection trays (also referred to as the top and bottom trays) were placed on the chamber mounting trays adjacent to the right-hand endplate and sealed within the chamber. The sample collection area and horizontal distance to the nozzle were identical for both top and bottom trays. Aerosolization of the virus was performed, and the virus was then incubated and allowed to settle onto the materials for 1 min. Following this, the trays were pulled out of the chamber. Squares of materials were removed and immediately soaked in 3 mL DMEM complete medium for 20 min to recover viable virus. The solution was subsequently serially diluted 1:10, added to 96 well plates containing VeroE6 cells. The cells was then incubated for 7 days at 37 °C. Infection in each well was determined using the green fluorescence signal for VSV-GFP or by probing SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein using chemiluminescent antibody staining as previously described. The titer was calculated by the Spearman–Kärber method80 to determine TCID50.

Aerosolization with PM from smoke

To assess the influence of PM from smoke on virus infectivity, smoke was collected from nicotine-containing vape solution (20 mg/mL nicotine, VICE, Canada), tobacco (Pall Mall, Smooth), and cannabis (0.35 g Fuego Night Rider Pre-rolls, 4.34 mg/g THC, <0.1 mg/g CBD) exhalations on 40 µm filter paper (28313-104, VWR, Canada) pre-wetted with DMEM complete medium. SPM was then washed off by 3 mL of 103 IU/mL VSV-GFP in DMEM complete medium to create a virus solution followed by TCID50 on Vero E6.

For aerosolization with tobacco and cannabis smoke, a “vaporizer” (ARIZER Solo II, ARIZER, Canada) was preheated to 200 °C and was filled with disassembled cannabis and tobacco leaves according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The apparatus was incubated for 5 min before connecting to a 50 mL syringe. For aerosolization with vape solution, the vape pen was directly connected to a 50 mL syringe. The smoke was collected in the syringe by gently pulling the plunger to mimic the human inhalation process. To simulate exhalation, the smoke was then loaded into the aerosolization pipeline by pressing down the plunger of the syringe. The subsequent steps of virus loading, aerosolization, and sample collection were conducted according to the previously described procedures (Fig. 1).

Droplet collection on Vero E6 cell line or human nasal tissue

Instead of collection materials, 2-well chamber slides (80286, ibidi, USA) seeded with 105 Vero E6 per well (volume of 1 mL with a 5 cm2 surface area) were employed to collect aerosolized droplets. The 1 ml of medium was removed before the chamber slides were placed on trays. 250 μL of 104 IU/mL virus was aerosolized as previously described above. 1 min following aerosolization, chamber slides were removed, and 1 mL DMEM complete medium was immediately added to each well. Cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 48 h. Supernatant from each chamber slide was collected 0, 24, 32, 36, 44 and 48 h post-aerosolization. 48 h after the aerosolization, RNA was extracted from collected supernatant using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Canada) and from cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Canada) and PureLink™ RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, Canada). RT-qPCR targeting SARS-CoV-2 N was performed to quantify the virus in the supernatant as described82. For experiments employing human nasal tissue, 6.5 mm transwell inserts (38024, Costar, USA) containing differentiated nasal tissues were placed on the trays in the chamber and the aerosolization process was followed as described for the Vero E6 cells. At 1 min following aerosolized droplet collection, the nasal tissue inserts were placed back into transwell plates containing tissue culture medium (PneumaCult™-ALI Medium, STEMCELL, Canada). RNA was extracted from the nasal tissue using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Canada) and PureLink™ RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, Canada) after 48 h incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Multiplex RT-qPCR targeting both human RPLP0 and SARS-CoV-2 N was performed to quantify relative infectivity in tissues. The use of nasal tissue received research ethics approval from the Western University Research Ethics Board, Project Name “The Effect of the Nasal Microbiome on Susceptibility to Bacterial and Viral Pathogens”, No. 119682.

RT-qPCR

All reactions were performed on the QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Canada) using Luna® Probe One-Step RT-qPCR 4X Mix with UDG (New England BioLabs, Canada). A final reaction volume of 10 μL containing 2.5 μL of template was used. Cycling conditions included a cDNA synthesis step (50 °C /5 min), an enzyme activation step (95 °C /20 s), and 45 cycles of denaturation (95 °C /15 sec) and annealing/elongation (60 °C /40 s). The primer pairs and probes are listed in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9. The Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, was performed for aerosolization data under different environmental conditions. The two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests were performed on the recovery of VSV-GFP aerosolized under different pressures, the viability of SARS-CoV-2 Delta on surfaces after aerosolization, and the recovery of VSV-GFP or SARS-CoV-2 Delta aerosolized under extreme conditions. The one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was applied to SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR data without aerosolization. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, or have been deposited on Figshare (https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Size_and_volume_of_aerosolized_droplets_on_the_coverslip/29252078/).

References

Baker, R. E. et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 193–205 (2021).

Hu, B., Guo, H., Zhou, P. & Shi, Z. L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.19, 141–154 (2020).

Cascella, M., Rajnik, M., Cuomo, A., Dulebohn, S. C. & Di Napoli, R. Features, evaluation, and treatment of coronavirus (COVID-19). (StatPearls, 2023).

Pöhlker, M. L. et al. Respiratory aerosols and droplets in the transmission of infectious diseases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 045001 (2021).

Chong, K. L. et al. Extended lifetime of respiratory droplets in a turbulent vapor puff and its implications on airborne disease transmission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 034502 (2021).

Ng, C. S. et al. Growth of respiratory droplets in cold and humid air. Phys. Rev. Fluids 6, 054303 (2021).

Parienta, D. et al. Theoretical analysis of the motion and evaporation of exhaled respiratory droplets of mixed composition. J. Aerosol Sci. 42, 1–10 (2011).

Xie, X., Li, Y., Chwang, A. T. Y., Ho, P. L. & Seto, W. H. How far droplets can move in indoor environments – revisiting the Wells evaporation–falling curve. Indoor Air 17, 211–225 (2007).

Cheng, C. H., Chow, C. L. & Chow, W. K. Trajectories of large respiratory droplets in indoor environment: a simplified approach. Build Environ. 183, 107196 (2020).

Wang, C. C. et al. Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses. Science 373, 6558 (2021).

Kutter, J. S. et al. SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are transmitted through the air between ferrets over more than one meter distance. Nat. Commun.12, 1–8 (2021).

Katelaris, A. L. et al. Epidemiologic evidence for airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during church singing, Australia, 2020 - Volume 27, Number 6—June 2021 - emerging infectious diseases journal - CDC. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 1677–1680 (2021).

Azimi, P., Keshavarz, Z., Cedeno Laurent, J. G., Stephens, B. & Allen, J. G. Mechanistic transmission modeling of COVID-19 on the Diamond Princess cruise ship demonstrates the importance of aerosol transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2015482118 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Probable airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a poorly ventilated restaurant. Build Environ. 196, 107788 (2021).

Santarpia, J. L. et al. Aerosol and surface contamination of SARS-CoV-2 observed in quarantine and isolation care. Sci.Rep. 10, 12732 (2020).

Raines, K. S., Doniach, S. & Bhanot, G. The transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is likely comodulated by temperature and by relative humidity. PLoS One 16, e0255212 (2021).

Ma, Y., Pei, S., Shaman, J., Dubrow, R. & Chen, K. Role of meteorological factors in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States. Nat Commun 12, 3602 (2021).

Ward, M. P., Xiao, S. & Zhang, Z. Humidity is a consistent climatic factor contributing to SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 67, 3069–3074 (2020).

Arifur Rahman, M., Golzar Hossain, M., Singha, A. C., Sayeedul Islam, M. & Ariful Islam, M. A retrospective analysis of influence of environmental/ air temperature and relative humidity on SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. J. Pure Appl Microbiol 14, 1705–1714 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Short-range exposure to airborne virus transmission and current guidelines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2105279118 (2021).

Lin, K., Schulte, C. R. & Marr, L. C. Survival of MS2 and Φ6 viruses in droplets as a function of relative humidity, pH, and salt, protein, and surfactant concentrations. PLoS One 15, e0243505 (2020).

Weber, T. P. & Stilianakis, N. I. Inactivation of influenza A viruses in the environment and modes of transmission: a critical review. J. Infect. 57, 361–373 (2008).

Pica, N. & Bouvier, N. M. Environmental factors affecting the transmission of respiratory viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 90–95 (2012).

Aboubakr, H. A., Sharafeldin, T. A. & Goyal, S. M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses in the environment and on common touch surfaces and the influence of climatic conditions: a review. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 68, 296–312 (2021).

Yang, W., Elankumaran, S. & Marr, L. C. Relationship between humidity and influenza A viability in droplets and implications for influenza’s seasonality. PLoS One 7, e46789 (2012).

Bogani, G. et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in surgical smoke during laparoscopy: a prospective, proof-of-concept study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 28, 1519–1525 (2021).

Setti, L. et al. Original research: potential role of particulate matter in the spreading of COVID-19 in Northern Italy: first observational study based on initial epidemic diffusion. BMJ Open 10, e039338 (2020).

Xu, R. et al. Weather, air pollution, and SARS-CoV-2 transmission: a global analysis. Lancet Planet Health 5, e671–e680 (2021).

Wu, X., Nethery, R. C., Sabath, M. B., Braun, D. & Dominici, F. Air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States: strengths and limitations of an ecological regression analysis. Sci Adv 6, eabd4049 (2020).

Engin, A. B., Engin, E. D. & Engin, A. Two important controversial risk factors in SARS-CoV-2 infection: obesity and smoking. Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 78, 103411 (2020).

Tomchaney, M. et al. Paradoxical effects of cigarette smoke and COPD on SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease. BMC Pulm. Med 21, 1–14 (2021).

Simons, D., Shahab, L., Brown, J. & Perski, O. The association of smoking status with SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19: a living rapid evidence review with Bayesian meta-analyses (version 7). Addiction 116, 1319–1368 (2021).

Grundy, E. J., Suddek, T., Filippidis, F. T., Majeed, A. & Coronini-Cronberg, S. Smoking, SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a review of reviews considering implications for public health policy and practice. Tob Induc Dis 18, 18332 (2020).

Barakat, T., Muylkens, B. & Su, B. L. Is Particulate matter of air pollution a vector of Covid-19 pandemic? Matter 3, 977 (2020).

Shihadeh, A. et al. Toxicant content, physical properties and biological activity of waterpipe tobacco smoke and its tobacco-free alternatives. Tob Control 24, 22–30 (2015).

Benowitz, N. L. et al. Tobacco product use and the risks of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19: current understanding and recommendations for future research. Lancet Respir. Med. 10, 900–915 (2022).

van Doremalen, N. et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1564–1567 (2020).

Chin, A. W. H. et al. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microbe 1, e10 (2020).

Ronca, S. E., Sturdivant, R. X., Barr, K. L. & Harris, D. SARS-CoV-2 viability on 16 common indoor surface finish materials. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 14, 49–64 (2021).

Oswin, H. P. et al. The dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity with changes in aerosol microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2200109119 (2022).

Dudalski, N. et al. Experimental investigation of far field human cough airflows from healthy and influenza-infected subjects. Indoor Air 30, 966–977 (2020).

Laue, M. et al. Morphometry of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 particles in ultrathin plastic sections of infected Vero cell cultures. Sci. Rep.11, 1–11 (2021).

Cureton, D. K., Massol, R. H., Whelan, S. P. J. & Kirchhausen, T. The length of vesicular stomatitis virus particles dictates a need for actin assembly during clathrin-dependent endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001127 (2010).

Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 3–20 (2022).

Sungnak, W., Huang, N., Bécavin, C., Berg, M. & Lung, H. C. A. Biological network. SARS-CoV-2 entry genes are most highly expressed in nasal goblet and ciliated cells within human airways. ArXiv 26, 681–687 (2020).

Victor H. K. Lam. Characterizing and Applying a Nasal Organotypic Model to Investigate the Effects of Immune Profile Types on SARS-CoV-2 Susceptibility. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository (Western University, 2024).

Ijaz, M. K., Brunner, A. H., Sattar, S. A., Nair, R. C. & Johnson-Lussenburg, C. M. Survival characteristics of airborne human coronavirus 229E. J. Gen. Virol. 66, 2743–2748 (1985).

van Doremalen, N., Bushmaker, T. & Munster, V. J. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Eurosurveillance 18, 20590 (2013).

Chan, K. H. et al. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv. Virol. 2011, 734690 (2011).

Lowen, A. C., Mubareka, S., Steel, J. & Palese, P. Influenza virus transmission is dependent on relative humidity and temperature. PLoS Pathog. 3, e151 (2007).

Nazaroff, W. W. Indoor aerosol science aspects of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Indoor Air 32, e12970 (2022).

Azuma, K. et al. Environmental factors involved in SARS-CoV-2 transmission: effect and role of indoor environmental quality in the strategy for COVID-19 infection control. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 25, 1–16 (2020).

Dinoi, A. et al. A review on measurements of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material in air in outdoor and indoor environments: implication for airborne transmission. Sci. Total Environ. 809, 151137 (2022).

Qian, H. et al. Indoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Indoor Air 31, 639–645 (2021).

Rozo-Lopez, P., Drolet, B. S. & Londoño-Renteria, B. Vesicular stomatitis virus transmission: a comparison of incriminated vectors. Insects 9, 190 (2018).

Berthelot, C. et al. Adaptation of proteins to the cold in Antarctic fish: a role for methionine? Genome Biol. Evol. 11, 220–231 (2019).

Hays, L. M. et al. Fish antifreeze glycoproteins protect cellular membranes during lipid-phase transitions. Physiology 12, 189–194 (1997).

Xu, Z. et al. Thermal and environmental stability of Siniperca chuatsi Rhabdovirus. Aquaculture 568, 739308 (2023).

Bajimaya, S., Frankl, T., Hayashi, T. & Takimoto, T. Cholesterol is required for stability and infectivity of influenza A and respiratory syncytial viruses. Virology 510, 234–241 (2017).

Iriarte-Alonso, M. A., Bittner, A. M. & Chiantia, S. Influenza A virus hemagglutinin prevents extensive membrane damage upon dehydration. BBA Adv. 2, 100048 (2022).

Ivanova, P. T. et al. Lipid composition of the viral envelope of three strains of influenza virus - not all viruses are created equal. ACS Infect. Dis. 1, 435–442 (2016).

Mesquita, F. S. et al. S-acylation controls SARS-CoV-2 membrane lipid organization and enhances infectivity. Dev. Cell 56, 2790–2807 (2021).

Fattorini, D. & Regoli, F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the Covid-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 264, 114732 (2020).

Zhu, Y., Xie, J., Huang, F. & Cao, L. Association between short-term exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 infection: evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 727, 138704 (2020).

Miyashita, L., Foley, G. & Grigg, J. Exposure to particulate matter increases expression of the angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptor. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 149, AB30 (2022).

Lin, C. I. et al. Instillation of particulate matter 2.5 induced acute lung injury and attenuated the injury recovery in ACE2 knockout mice. Int J. Biol. Sci. 14, 253 (2018).

Aztatzi-Aguilar, O. G., Uribe-Ramírez, M., Arias-Montaño, J. A., Barbier, O. & De Vizcaya-Ruiz, A. Acute and subchronic exposure to air particulate matter induces expression of angiotensin and bradykinin-related genes in the lungs and heart: angiotensin-II type-I receptor as a molecular target of particulate matter exposure. Part Fibre Toxicol. 12, 1–18 (2015).

Cao, C. et al. Inhalable microorganisms in Beijing’s PM2.5 and PM10 pollutants during a severe smog event. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1499–1507 (2014).

Borisova, T. & Komisarenko, S. Air pollution particulate matter as a potential carrier of SARS-CoV-2 to the nervous system and/or neurological symptom enhancer: arguments in favor. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 40371–40377 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Airborne transmission may have played a role in the spread of 2015 highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks in the United States. Sci. Rep.9, 1–10 (2019).

Jonges, M. et al. Wind-mediated spread of low-pathogenic avian influenza virus into the environment during outbreaks at commercial poultry farms. PLoS One 10, e0125401 (2015).

Farhangrazi, Z. S., Sancini, G., Hunter, A. C. & Moghimi, S. M. Airborne particulate matter and SARS-CoV-2 partnership: virus hitchhiking, stabilization and immune cell targeting — a hypothesis. Front. Immunol. 11, 579352 (2020).

Thelestam, M., Curvall, M. & Enzell, C. R. Effect of tobacco smoke compounds on the plasma membrane of cultured human lung fibroblasts. Toxicology 15, 203–217 (1980).

Warnes, S. L., Little, Z. R. & Keevil, C. W. Human coronavirus 229E remains infectious on common touch surface materials. mBio 6, e01697 (2015).

Minoshima, M. et al. Comparison of the antiviral effect of solid-state copper and silver compounds. J. Hazard Mater. 312, 1–7 (2016).

Govind, V. et al. Antiviral properties of copper and its alloys to inactivate covid-19 virus: a review. BioMetals 34, 1217–1235 (2021).

Su, L. J. et al. Reactive oxygen species-induced lipid peroxidation in apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Oxid. Med Cell Longev. 2019, 5080843 (2019).

Paulsen, C. E. & Carroll, K. S. Cysteine-mediated redox signaling: chemistry, biology, and tools for discovery. Chem. Rev. 113, 4633–4679 (2013).

Stegelmeier, A. A. et al. Characterization of the impact of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus on the trafficking, phenotype, and antigen presentation potential of neutrophils and their ability to acquire a non-structural viral protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 6347 (2020).

Kärber, G. Beitrag zur kollektiven Behandlung pharmakologischer Reihenversuche. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 162, 480–483 (1931).

Amanat, F. et al. An in vitro microneutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2 serology and drug screening. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 58, e108 (2020).

Corporate Authors(s): National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (U.S.). Division of Viral Diseases. 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) real-time rRT-PCR panel primers and probes. Series: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (2020).

McGregor, B. L., Rozo-Lopez, P., Davis, T. M. & Drolet, B. S. Detection of vesicular stomatitis virus indiana from insects collected during the 2020 outbreak in Kansas, USA. Pathogens 10, 1126 (2021).

Nakayama, T. et al. Assessment of suitable reference genes for RT-qPCR studies in chronic rhinosinusitis. Sci Rep 8, 1568 (2018).

Acknowledgements