Abstract

Given the enormous output and pace of development of artificial intelligence (AI) methods in medical imaging, it can be challenging to identify the true success stories to determine the state-of-the-art of the field. This report seeks to provide the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) community with an initial guide into the major areas in which the methods of AI are contributing to MRI in oncology. After a general introduction to artificial intelligence, we proceed to discuss the successes and current limitations of AI in MRI when used for image acquisition, reconstruction, registration, and segmentation, as well as its utility for assisting in diagnostic and prognostic settings. Within each section, we attempt to present a balanced summary by first presenting common techniques, state of readiness, current clinical needs, and barriers to practical deployment in the clinical setting. We conclude by presenting areas in which new advances must be realized to address questions regarding generalizability, quality assurance and control, and uncertainty quantification when applying MRI to cancer to maintain patient safety and practical utility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

We seek to provide a critical assessment of the opportunities and limitations of artificial intelligence (AI) in the context of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of cancer and provide the reader with guidance on where to go for further information. Indeed, there have been many excellent publications on various aspects of AI in MRI (see, for example, references1,2,3,4). However, given the explosion of publications on the topic, it can be challenging to separate the hype from the actual successes and identify the current state-of-the-art of the field. In particular, it is difficult to identify what is currently available—and what the practical limitations are—for the application of AI in the MRI of cancer. In this contribution, we seek to respectfully provide a more balanced presentation of the utility and limitations of AI for MRI within clinical oncology. To address this problem, we begin by describing the key components of AI that are frequently employed in medical imaging, in general, and MRI, in particular. In Section 3, MRI acquisition and reconstruction is presented as a regression task that involves estimating the voxel values of an image from raw scanner measurements. In Section 4, we discuss the classification task of image segmentation, which entails categorizing every voxel as (for example) tumor or healthy tissue, and registration, which entails spatially aligning images to a common space. Sections 5 and 6 concern the classification tasks of making a diagnosis and prognosis from the MRI data, respectively, which require accounting for global characteristics (e.g., the location and size of tumors) to make a prediction.

Key AI concepts for medical imaging

What is artificial intelligence?

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the theory and development of computer systems that can perform tasks normally thought to require human intelligence including language, visual perception, and reasoning5. We focus on a branch of AI called machine learning (ML), which refers to training a statistical model on relevant data to perform a task. Deep learning is a sub-branch of ML that concerns the development of neural networks (NN), a special class of models that have demonstrated practical utility in medical imaging6,7,8.

Common ML techniques for medical imaging

A key design consideration when developing ML models is the type(s) of data available for training, which can be split into supervised and unsupervised settings. Supervised datasets contain matched {sample, label} pairs; for example, MRI images annotated as containing or not containing a tumor. In this setting, the model learns to predict the label for each sample. However, annotation can be time-consuming and expensive as domain experts (e.g., radiologists) must label each individual data point9. In contrast, unsupervised datasets contain only samples, without any labels. For example, given a set of MR training images obtained with low spatial resolution, one may train a model to learn to increase the resolution (called super-resolution10,11) without access to any high-resolution examples. After training, the model can be applied to enhance the quality of new images acquired at lower resolution, thus reducing the need for acquiring high-resolution data. While the unsupervised setting eases the burden of annotating data, the ability to generate useful labels is intimately connected to the ability to collect high-quality data that are relevant to the intended application. For example, if only images of knees are available to train a super-resolution model, the model is likely to perform poorly when used to enhance images of brains12.

The reader may find it helpful to refer to Table 1 as they consider the rest of the paper.

AI-based image acquisition and reconstruction of MRI data

Image acquisition and reconstruction are inextricably linked in MRI. Image acquisition consists of both signal and spatial encoding through user-controllable radiofrequency and gradient waveforms. By modifying the different components of the acquisition process (pulse time delay, signal frequency, signal strength, signal phase, etc.), the speed of acquisition as well as the sensitivity of a given image to a particular tissue property is changed. The resulting image contrast can be described by:

where x ∈ Cn is the (vectorized) image (containing n voxels) generated based on a spatiotemporal function f of both acquisition-controlled signal encoding parameters, θ, and biophysical tissue parameters, q13. The acquired measurements (called k-space) are related to the image through the linear operator

where Aϕ ∈ Cm×n represents a (possibly multi-coil) sampled Fourier transform, η ∈ Cm is additive complex-valued Gaussian noise, and m is the number of acquired measurements with locations determined by the spatial encoding parameters ϕ.

The measured raw signals (i.e., y) are not immediately ready for visualization as they represent Fourier components of the image. Therefore, optimization algorithms are used to reconstruct the image. The reconstruction algorithm can be represented by a function g(y) which either inverts the linear measurement process in Eq. (2) to estimate the image x, or inverts the non-linear measurement process in Eq. (1) to estimate the tissue parameters, q. These tasks are often challenging as the data are corrupted by additive noise and often subsampled (m << n) to reduce scan time, thereby leading to an ill-posed inverse problem.

Common machine learning techniques in image acquisition and reconstruction

Training machine learning models to assist in both acquisition and reconstruction procedures is often framed as an optimization problem in which we train a parameterized function \({f}_{w}(\cdot )\), often in the form of a deep neural network, to complete a specific task. In the supervised case, the function is optimized with respect to a training set of images (or scan parameters, or tissue parameters) given input k-space. This often takes the form of minimizing some loss function \(D\left(\cdot ,\cdot \right)\) via large-scale optimization solvers in the following way:

where xi and yi represent the i’th training sample and N is the size of the training set. In unsupervised learning, the same task is solved but with a minimization that only depends on the inputs yi.

Image acquisition

The selection of signal encoding parameters θ and spatial encoding parameters ϕ can influence both the contrast of the resulting image (Eq. (1)) and acquisition time (Eq. (2)). As image sensitivity to pathology is affected by acquisition parameters, it makes sense to optimize the image acquisition pipeline to increase sensitivity to relevant tissue contrast. This means finding the optimal radiofrequency flip angles, phases, timings, etc. for a desired contrast. Supervised learning has been used to find these acquisition strategies for optimizing contrast sensitivity14,15 as well as optimizing the k-space measurements16,17,18,19. Here w in Eq. (3) is replaced by either or both of contrast (θ) and k-space locations (ϕ). For example, k-space trajectory optimization can be used to accelerate imaging by reducing the number of acquired k-space measurements for a given target spatial resolution. In this case, the loss function will take the form

where yi(ϕ) represents a particular sampling trajectory in k-space (for example, specific phase encode lines) for the ith training sample, and \({f}_{w}\left({y}_{i}\left(\phi \right)\right)\) represents a reconstruction algorithm that takes the subsampled k-space and outputs an image. When the reconstruction network and the sampling trajectory are both differentiable, this is straightforward to implement; however, for Cartesian sampling, this problem is combinatorial in nature. Therefore, greedy approaches or smooth approximations become necessary16,17,18,19). A similar approach can be used to update other scan parameters that influence image contrast15.

After Eq. (4) is solved, an optimized acquisition scheme can be represented as a new measurement model Aϕ and can be implemented on the scanner. When this sequence is used for acquisition, the image reconstruction problem can then be solved given the acquired measurements and the measurement model (i.e., Eq. (2)).

Image reconstruction

Classical image reconstruction relies on hand-crafted priors like L1-wavelet regularization20. More recently, deep neural networks have contributed promising techniques for image reconstruction. AI-based techniques can be separated into several categories: end-to-end supervised, end-to-end unsupervised, and generative modeling. In the end-to-end supervised setting, the function fw in Eq. (3) is trained with pairs of subsampled k-space data and images obtained from fully sampled data, (yi, xi), and D(・, ・) can represent any valid metric of distance (e.g., mean squared error). End-to-end unsupervised methods also train an NN except with access only to subsampled measurements, yi, and no accompanying reference image, xi. This is important in scenarios where it is only possible to collect large amounts of subsampled data (e.g., in dynamic imaging). End-to-end NNs for supervised and unsupervised reconstruction can take many forms, but unrolled optimization networks, which alternate between classical optimization steps (e.g., conjugate gradient descent) and forward passes through a NN, are quite common21,22.

Although end-to-end methods are powerful, performance can degrade with changes in how the measurements are taken at training versus at test time, which is referred to as a “test-time distribution shift”. Recently, the use of generative models for inverse problems has been shown to improve robustness to variations in acquisition schemes. These methods train a Bayesian prior on the distribution of fully sampled images, p(x), and are therefore agnostic to distribution shifts in the likelihood, p(y|x), which can change across scans and imaging protocols (i.e., the signal and spatial encoding parameters). Perhaps the most popular method for including generative priors in inverse problems is by way of score-based, or diffusion probabilistic models23,24.

Despite the distinction between supervised and unsupervised training, it is important to note that AI models are trained on data derived from raw sensors (i.e., the raw k-space measurements), which are typically acquired via multi-coil arrays and are often subsampled. Even when the data are fully sampled, they are noisy and must be first reconstructed into images. Therefore, there is no real notion of “ground-truth” images. New training methods that account for the acquisition process have been proposed, both for end-to-end methods that are trained to take in acquired measurements and output reconstructed images, as well as for generative models (where the AI model is used as a statistical image prior to an iterative reconstruction).

It is also possible to jointly train the acquisition parameters together with the reconstruction method, which may consist of deep neural networks14,15,16,17. For example, Aggarwal et al., formulate the optimization problem as

In other words, they jointly solve for the phase encode lines given by ϕ and the neural network reconstruction given by fw.

Current clinical needs for AI-based image acquisition and reconstruction

AI has shown the ability to maintain high image quality using fewer measurements than conventional reconstruction techniques, and can even produce diagnostic images for use in specific downstream clinical tasks25. For example, AI for the reconstruction of prospectively accelerated abdominal imaging produced non-inferior images compared to conventional reconstruction methods26. AI for image reconstruction has made its way into products for several scanner manufacturers. Two recent examples are GE’s AIRTM reconstruction protocol and Siemen’s Deep ResolveTM product line. However, it is important to emphasize that many of these products are for specialized cases (e.g., specific anatomy/contrast) and are not currently deployed for many specific use cases. An ability to generalize across imaging protocols is critical for widespread adoption.

An additional concern for many longer scan sessions is patient motion, especially for pediatric populations. In general, this includes developing robust reconstruction methods that can handle dynamic imaging scenarios (e.g., contrast-enhanced imaging27) where it is often infeasible to collect the desired measurements from a single imaging volume. As many forms of pathology exhibit only subtle contrast changes, there is also a need for acquisition/reconstruction methods capable of resolving subtle variations in tissue properties, and thus reducing the use and dose of exogenous contrast agents containing Gadolinium28. Finally, as many new methods often train and measure performance based only on image quality metrics, the need for better quantifying the link between image quality and downstream diagnostic metrics (e.g., tumor classification) must be better understood and optimized for when designing new AI-based techniques.

Barriers to practical deployment in the clinical setting

Although AI has displayed marked improvements over classical reconstruction and acquisition techniques17,21,22,23, there are still many issues that must be addressed before clinical adoption can be pursued. For example, AI techniques need to be robust to variations in how data are collected due to differences in vendor, field strength, field inhomogeneity, and patient motion. Models must be trained on representative data for each of the variations in hardware and imaging protocols; if the scan protocol changes (or if the scan parameters change to accommodate a specific patient such as a larger field of view, different resolution, different echo time, larger fat saturation bands, etc.), then this “new” protocol could be out of the distribution that was included in the training set, and the subsequent performance will degrade as seen in Jalal et al.23. This can quickly devolve into a “model soup.” For example, the winning team in the FastMRI 2020 reconstruction challenge trained eight independent models, to account for field strength, scan anatomy, etc1. The interpretability must also be improved through uncertainty quantification. To demonstrate these points, Fig. 1 shows two example deep learning reconstructions (reproduced from the FastMRI 2020 reconstruction challenge29) where fully sampled scans were retrospectively subsampled to simulate faster scanning. In the first case, the DL reconstruction results in a faithful, and diagnostic image; however, in the second case, the DL reconstruction falsely hallucinates a blood vessel, likely due to the unseen artifact caused by surgical staples. This demonstrates the enormous challenge, and potentially clinically confounding problems, of deploying these models in clinical settings30.

The fully sampled images (A, C) were retrospectively subsampled to simulate 8× (top) and 4× (bottom) faster scans. In the top case, the DL reconstruction (B) is able to reproduce with high fidelity the lesion in the post-contrast T1-weighted image, though with some blurring. In the bottom case, the DL reconstruction (D) hallucinated a false vessel (red arrow), perhaps due to the surgical staple artifact not being well-represented in the training set.

A potential avenue to addressing these problems is in the use of generative models for reconstruction: generative models have been shown to be less sensitive to changes in scan protocols and anatomy, largely due to the decoupling between the physical forward model and the statistical image prior. In other words, generative models are trained to learn the distribution of MR images independent of the physical imaging system parameters that produced those images. This means that the generative model can be used to reconstruct images from MR data acquired with other imaging schemes, so long as the images follow the model’s learned distribution and the imaging parameters are known. Learning optimal sampling patterns for generative models could also be helpful as this would allow the acquisition to be more tailored to the specific imaging protocol, while still benefiting from the robustness offered by generative model-based reconstruction.

Registering and segmenting MRI data via AI

Common AI techniques in segmentation and registration

Tumor and tissue segmentation

Tumor and tissue segmentations are often used for surgical planning, radiotherapy design, and assessing treatment response31,32. Currently, manual or semi-automated segmentations often suffer from being resource-intensive and exhibiting unacceptable inter-observer variability31,33. While automated segmentation approaches enabled by AI may reduce both of these concerns, they require extensive training sets with expert-defined segmentations, and (due to its black-box nature) may fail without warning31,34. Given these limitations, AI-based approaches require human oversight to review and, if necessary, edit31,35. Many AI-automated approaches are based on voxel-based features and typically employ convolutional neural networks (CNN; such as U-Nets) to identify healthy tissue (e.g., organs-at-risk for radiotherapy planning), cancer, and intra-tumoral sub-regions (e.g., necrosis, edema, enhancing lesions)32. Pal et al. introduced a method combining fuzzy c-means clustering and random forest algorithms and showed 99% accuracy for segmenting spine tumors36. Kundal et al. evaluated four CNN-Based methods for brain tumor segmentation. (CaPTk, 2DVNet, EnsembleUNets and ResNet50) EnsembleUNets achieved Dice scores of 0.93 and 0.85 and Hausdorff Distances of 18 and 17.5 for testing and validation, respectively37. While current approaches do not eliminate the need for human refinement, they can often provide an acceptable segmentation of organs at risk that can be manually refined when greater precision and accuracy are required38.

Image registration

Classical image registration methods consist of estimating the optimal transformation that maximizes the similarity between a set of images and the “target” image. Multiple combinations of transformations (rigid or deformable) and cost functions (sum square differences, normalized cross-correlation, or mutual information) exist. Osman et al. introduced a deformable CNN-based registration of 3D MRI scans for glioma patients called ConvUNet-DIR39 that outperformed the Voxelmorph method with a mean dice score of 0.975 and similarity index of 0.908 compared to 0.969 and 0.893. However, each method has specific drawbacks such as being sensitive to artifacts or being limited in capturing local differences40. Learning-based methods, both supervised and unsupervised, attempt to overcome these difficulties. Supervised learning models such as BIRNet41 and DeepFLASH42 are trained using paired images (i.e., registered and un-registered images) with their corresponding transformation. Even though such methods can achieve accurate registration performance, finding the necessary training data (which includes before/after registered images and the associated transformations) is difficult. Thus, unsupervised deep learning-based approaches are preferred43,44, traditionally focusing on optimizing similarity metrics and model architectures using gradient-based optimizers like stochastic gradient descent.

Current clinical needs for AI-based image segmentation and registration

We assign a moderate state of readiness for DL-based registration of MRIs of brain cancer. In particular, locally registering voxels at the tumor boundary is challenging. Estienne et al.45 introduced a joint 3D-CNN method for brain registration and tumor segmentation. The model was trained using the BraTS 2018 dataset46 and then tested on over 200 pairs from the same dataset. The registration method was evaluated by computing the average distance between two ratios: (1) original to deformed tumor mask area, and (2) between brain volumes of the paired images. The method outperformed a previously established approach using whole tumor masks (part of the VoxelMorph package47) that employed an unsupervised learning-based inference algorithm that was initially applied to healthy brain MRIs48.

There are several areas where DL-based segmentation can meet clinical needs. First, segmenting a tumor from surrounding healthy tissues is central to radiotherapy planning. In fact, the time-intensive nature of manual segmentation has limited the widespread implementation of adaptive radiotherapy49. To address this challenge, AI tools employing CNNs to perform semi-automated and automated segmentation have been developed. Such tools often have reduced performance after treatment (i.e., surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy), an increased focus should be placed on training these methods with post-treatment data50 to enable accurate longitudinal segmentation of tumors. Clinical deployment of these automated segmentation tools seeks to accelerate the segmentation task within the workflow of adaptive radiotherapy. However, these algorithms have had mixed success due to their limited generalizability when applied to data they did not see during training, therefore limiting their widespread adoption. There are numerous potential reasons for the lack of success of AI-based segmentation algorithms including variability in the scan acquisition, patient-specific presentation of normal tissue and tumors, and the segmentation goals of the treating clinical team.

Tumor segmentation and registration are also necessary steps for quantitatively describing imaging features that represent the underlying biology (Fig. 2). The inconsistencies in MRI segmentation can arise from various factors including inter-rater variability among segmentations done by different readers and intra-rater variability among segmentations done by the same reader multiple times. Additional sources of inconsistency include variation in input data quality and resolution due to acquisition protocols, algorithmic bias across different segmentation methods and/or parameter settings, temporal changes in anatomical structure, or intensity contrast of segmentation targets due to disease progress or intervention effects51,52,53,54. These inconsistencies introduce bias in the measurement of volume, morphology, and contrast of segmented regions, and influence the accurate and reproducible extraction of (for example) radiomic features55,56,57,58, which then restricts the reliability and generalizability of radiomics’ clinical application in diagnosis and prognosis59,60. Therefore, it is critical to develop approaches to improve the consistency of segmentation to advance quantitative imaging.

Beginning with image acquisition (A), variability and uncertainty is propagated through each step and can affect the accuracy in assessing lesion response and/or anticipated clinical outcome (H). Image processing routines (B) are then used to quantify image features prior to image registration (C), however, image registration may also occur prior to post-processing. Once the images are co-registered, automatic or manual segmentation (D) identifies the tissue of interest. At this stage, the clinical response can be assessed by determining lesion response (E). Alternatively, the features (F) from imaging and -omics (G) can be identified to predict clinical outcome (H) or lesion response (E). Error at any of these steps can compound and result in a false classification of patient outcomes.

Shortcomings of current registration and segmentation approaches

A fundamental shortcoming of current AI-based segmentation and registration approaches is limitations in the available data itself for training and validating these approaches. These limitations include scarcity of data in the target setting, variations in data quality, standardization of imaging protocols, or deviation of imaging protocols from those used to train previously validated approaches. For example in the setting of brain cancer, while there have historically been significant efforts to segment pre-operative tumors, a recent literature review of 180 articles observed only three papers that included post-operative imaging31.The lack of trained models or expert-segmented or curated data limits61 the transferability of registration and segmentation approaches to new applications where treatment may alter image contrast or introduce large deformations and alterations in the anatomy. Another pitfall is the phenomena of data drift where changes in imaging protocols or other factors may lead to input data that falls outside of the distribution used for training62 resulting in reduced accuracy of segmentations and registration.

AI for diagnosis from MRI data

Common AI techniques for diagnosis via MRI

While computer-aided detection systems (CADe) leverage AI to identify the position of the tumor within an image, computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) systems exploit imaging features to characterize it quantitatively (see Fig. 3). These technologies have been constructed using AI approaches based on radiomics, ML32,63,64,65 (e.g., random forests, support vector machines), and DL32,63,64,65. In particular, CNNs are the most common choice of architecture for DL-based CADe and CADx. For example, Chakrabarty et al.66 trained a CNN with post-contrast, T1-weighted data to perform differential diagnosis of six brain tumor types and healthy tissue, achieving AUCs over 0.95 in internal and external validation. Additionally, Saha et al.67 achieved AUCs over 0.86 with a CNN-based CADe/CADx system for clinically significant prostate cancer that was informed by T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted MRI (DW-MRI), apparent diffusion coefficient maps (ADC), and an anatomic prior of zonal cancer prevalence. While CNN training requires vast labeled datasets and computational resources, pre-trained CNNs (e.g., AlexNet, GoogLeNet) can also be used in new datasets for cancer detection and diagnosis tasks (i.e., transfer learning)32,65,68,69. For instance, Antropova et al.70 achieved an AUC of 0.89 in the diagnosis of malignant breast lesions on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) data with a CADx system that combined radiomics with CNN-based features, for which they used the pre-trained VGG19 model.

The figure illustrates the global process whereby MRI sequences (i.e., T2-weighted (T2W), DW-MRI, and DCE-MRI) are processed with a CNN to identify whether there is a tumor present, its localization, and the differential diagnosis (e.g., tumor class, tumor subtype, clinical risk). Several CNN architectures have been used to construct CADe and CADx systems for this type of MRI analysis66,67,69,91,94. This figure shows the use of a U-net due to its successful use for automatic tumor detection and segmentation, as well as in the context of cancer diagnosis.

Current clinical needs

There are ongoing efforts to leverage AI to analyze standard-of-care MRI data for cancer detection and diagnosis to reduce inter-reader variability, while also streamlining time-intensive diagnostic processes32,63,64,65,69. These methods attempt to enable timely and reliable assistance for MRI-informed clinical decision-making for diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment. For example, CADe/CADx systems can assist in determining an appropriate clinical management strategy for the identification of clinically-significant prostate cancer64,69 on multiparametric MRI data. A fundamental challenge in neuro-oncology is the differential diagnosis of primary central nervous system tumor subtypes and brain metastases, which necessitate different treatments32,66. Current clinical needs in breast cancer diagnosis include early detection of high-risk disease, improvement of screening for intermediate-risk and dense breast populations, the differentiation between benign and malignant lesions, and the identification of specific subtypes63,65,70,71. These are all tasks that could potentially be assisted by leveraging AI methods, although there are several challenges to their development (see Section 5.3). Additionally, more recent efforts are tackling the integration of multimodal data (e.g., imaging, histopathology, biomarkers, omics) using AI to better inform cancer management.

Barriers to practical deployment in the clinical setting

In Medicine, as opposed to many other fields of application of AI, understanding why a decision is made (e.g., a diagnosis) is as important as the decision itself. Thus, establishing model interpretability is a fundamental barrier in the clinical translation of AI-based techniques for decision-making in clinical oncology63,64,72,73. Beyond explaining the biophysical causes underlying AI-driven cancer detection and diagnosis, model interpretability is also required to extrapolate and interrogate model outcomes63,64, which would contribute to more informed clinical decisions. The medical AI community has proposed several approaches to address the lack of interpretability in MRI-informed AI models for cancer detection and diagnosis74,75,76, such as class activation methods66,67, knowledge-driven priors67,74, and integration of multimodal multiscale data77,78. Furthermore, recent approaches in the field of scientific machine learning have shown promise in improving the interpretability of AI models79 and could therefore be developed for the detection and diagnosis of cancer on MRI data. For example, mechanistic feature engineering can identify biophysically-relevant inputs that characterize tumor biology80,81, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs)82,83 include a (bio)physical model in the loss function, and biology-informed neural networks (BINNs) adapt the model architecture according to prior biological knowledge84,85.

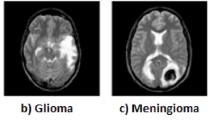

Despite the progress in the development of MRI-informed AI methods for cancer detection and diagnosis, these technologies need to address potentially critical pitfalls in their performance in tumor-specific scenarios. For example, the detection of malignant breast lesions using MRI-informed AI models can be affected by complex tumor geometries (e.g., non-mass tumors), the architectural and radiological features of surrounding healthy tissue (e.g., tissue density, background parenchymal enhancement), as well as signal distortion and movement of the tumor during DCE acquisition65,71,86,87. Additionally, the performance of CADe/CADx methods for prostate cancer can be affected by several well-established MRI confounders64,67,88,89,90, such as prostatitis and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Similarly, the different types of tumors that may develop in the brain can produce similar MRI signals that complicate their differential diagnosis32,66. To address these issues, future studies require (i) training and validation databases that balance the amount and diversity of confounding features and comorbidities (e.g., breasts with mass-like and non-mass geometries; prostates with cancer alone and combined with other prostatic pathologies; and diverse brain tumor cases), and (ii) training AI models to recognize confounding patterns (e.g., standard textural and deep learning features) to boost the performance of CADe/CADx technologies for cancer32,64,65,66,67,71,86,87,88.

Several validation, implementation, ethical, and data issues have also hindered the clinical translation of AI models for cancer detection and diagnosis. Firstly, the diagnostic performance of CADe/CADx systems still needs to be externally validated in large prospective clinical trials including diverse imaging acquisition methods, patient demographics, and reader expertise32,63,64,65,69,91,92. Additionally, two key obstacles to their practical clinical deployment are the lack of local data science support and the high computational cost, particularly during the training of DL models. The need for high-performance hardware and efficient algorithms demands a considerable financial investment, hindering widespread adoption in resource-constrained healthcare settings. As noted in Section 5.1, transfer learning is a promising strategy to address these computational limitations by leveraging pre-trained DL models32,65,68,69. Another fundamental issue is the limited availability of rigorously curated data for AI model development, which may require specific labels and non-standard preprocessing that can be costly and time-consuming63. Furthermore, biases in data collection processes and unrecognized biases in clinical practices from which the training data is gathered can lead to distorted outcomes, even perpetuating societal inequalities93. Data inaccessibility due to confidentiality concerns, potential breaches compromising patient confidentiality, and strict data privacy regulations limiting collaboration also constitute important challenges63,93. To address limitations in data transfer for multicenter collaborations, federated learning94 is a potential strategy that relies on sharing model parameter updates rather than datasets.

AI for predicting response from MRI data

Common AI techniques for predicting response

AI can be used to link imaging data to outcomes such as pathological response, time to recurrence, and overall survival. Commonly used machine learning methods for predicting response include support vector machine (SVM)95,96,97, regression98,99, random survival forest (RSF)100, clustering101,102, and CNNs99,103,104. Recently, more DL models105 are established based on the transformer architecture or incorporating the attention mechanism106. Panels A and B of Fig. 4 demonstrate how SVM and CNN, respectively, can be used in prediction of response.

In Panel A, features related to histograms of relative cerebral blood volume97 or peak height of a perfusion signal107 are extracted from the imaging data. Clinical information such as patient age and genetic data can also be included as features. The goal of the SVM is to take N features and determine the (N-1)-dimensional hyperplanes that maximally separate (for example) patients into short, medium, or long survival, or complete response as determined by pathology. Panel B shows potential inputs to a CNN – either the whole image domain, imaging-derived features, or a patch of the domain. Extracting patches from a domain can be used to increase the amount of training data, or to reduce computational burden when working with large images. These are then input to a CNN, here represented with convolution and down sampling layers feeding into a fully connected architecture. In general, multiple sets of convolution and down-sampling layers are used. The network output accomplishes the same goal as the SVM in Panel A; namely, separating inputs into classes such as responders and non-responders, or survival at a particular time.

In brain cancer, combining clinical data with AI methods has been shown to be more effective in predicting survival outcomes than clinical methods alone107,108. SVM, for instance, has been used to predict treatment outcomes for gliomas96 by employing both clinical and functional features96. An SVM trained by Emblem et al. found whole tumor relative cerebral blood volume was the optimal predictor of overall survival97. CNNs have been used for the assessment and prediction of outcomes. For example, Jang et al.104 distinguished between pseudo-progression and progression in patients with GBM using CNNs with long short-term memory (LSTM)109,110, an ML algorithm used to train recurrent NNs. They compare two options for the CNN input data: (1) MRI (post-contrast T1-weighted images) and clinical parameters, and (2) MRI data alone. The model trained on MRI and clinical data outperformed the MRI-only model, as the AUC for predicting progression versus pseudo-progression had values of 0.83 and 0.69, respectively. This demonstrates that the combination of AI, MRI, and clinical features might help in post-treatment decision-making for patients with GBM104.

In prostate cancer, MRI-based AI has enabled the prediction of recurrence after surgery and radiotherapy111. For example, Lee et al.99 developed a DL model trained on preoperative multiparametric MRI data (T2-weighted, DW-MRI, and DCE-MRI) to predict long-term post-surgery recurrence-free survival. Using Cox models and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, the features obtained from multiparametric MRI data via their DL model outperformed clinical and radiomics features, while the combination of clinical and DL features yielded the best predictive performance. Additionally, in breast cancer, prognostic CNN models trained on MRI data have also enabled the prediction of pathological complete response for neoadjuvant chemotherapy112.

Current clinical needs

Common clinical challenges in oncology include the stratification of patients by treatment response, risk of relapse, and overall survival113,114. Identification of patient outcomes before treatment begins (or early during treatment) could help select, escalate, or de-escalate prescribed treatments, as well as tailor personalized follow-up schedules. It is important to note that analyses (AI-based and otherwise) leveraging multi-parametric MRI as compared to biopsy-based stratification also enable longitudinal whole-tumor coverage addressing the sampling bias limitations of biopsy113. Furthermore, many of these AI-based approaches leveraging imaging data achieve greater performance over standard clinical information (e.g., age, sex, extent of surgery) alone113,114.

Barriers to practical deployment in the clinical setting

Although AI-based approaches have demonstrated greater performance over standard clinical information in some settings, these studies are typically done in specific cohorts with limited external validation and therefore have limited generalizability115. The variability in MR acquisition techniques between manufacturers, scanner types, protocols, and institutions can lead to substantial bias in training image-guided AIs without proper data harmonization116, such as that completed by Marzi et al.117, who were able to reduce site effects after data harmonization in a study of T1-weighted MRI data from 1740 healthy subjects at 36 sites using a harmonizer transformer as part of the preprocessing steps for a machine learning pipeline. Moreover, restrictions on inter-institution sharing of patient data118 (due to concerns such as privacy) may restrict the verification of model generalizability. These limitations, alongside uncertainty in the AI models themselves, create substantial barriers to the widespread clinical adoption of AI models for response prediction. Federated learning could be a realistic strategy to bypass the complexity of inter-institutional data sharing. Instead of requiring assembling data from different institutions into a centralized large-scale dataset, federated learning enables training of the AI model on decentralized, private datasets in multiple sites independently, then only the trained parameters (instead of original data) will be shared between training sites to generate the globally tuned model119,120

Efforts to construct large, publicly available MRI datasets for brain tumors are ongoing. However, careful considerations need to be made while using them in training, testing or validating AI-based model121. One significant issue is the potential for overlaps between different datasets (i.e., multiple datasets containing the same patient), which can reduce the number of uniquely available data. More specifically, the IvyGAP Radiomics dataset contains the pre-operative MRIs of the IvyGap dataset with additional segmentations and derived radionics parameters. Moreover, the BraTS 2021 dataset contains data that was available in the previous BraTS challenges and other public datasets such as the TCGA-LGG (65 patients), TCGA GBM (102 patients), and Ivy Gap (30 patients). This may lead to redundancy and diminish the overall diversity of the training data121. Furthermore, these datasets have been published for more than a decade and some of them have undergone updates, adding a higher variability in protocols, scans quality, and evolving WHO classification. We identify similar issues in prostate cancer122, particularly when it comes to the age of the publicly available datasets (many being 10+ years old) and overlap between datasets (which may or may not be known between sets). Dataset sizes are also often small, especially once missing or low-quality data is removed.

Efforts for breast cancer data standardization are also in progress. For instance, Kilintzis et al.123 attempted to produce a harmonized dataset from 5 publicly available datasets from the TCIA platform, including 2035 patients. More generally, Kosvyra et al.124 propose a new methodology for assessing the data quality of cancer imaging repositories by incorporating a three-step procedure that includes a data integration quality check tool to ensure compliance with quality requirements.

Federated learning could be a practical strategy to overcome the complexity of inter-institutional data sharing. Instead of assembling data from different institutions into a centralized large-scale dataset, federated learning enables the training of the AI model on decentralized, private datasets in multiple sites independently, then only the trained parameters (instead of original data) are shared between training sites to generate the globally tuned model. We discuss these points via the results presented in Rauniyar et al.119 and Guan et al.120.

Beyond data variation, the cancer population itself is heterogeneous (as categorized by the cancer subtypes, staging, patient demographics, etc.), which leads to differences in therapy response between patients125. Moreover, novel therapies can be introduced into clinical care, the therapeutic regimens vary between institutions, and treatments can be refined, leading to significant differences in datasets collected at different times126. Overall, the trade-off between the sample size and homogeneity of accessible datasets to train AI models is a major barrier to the robust application of AI for response prediction. One method that could help combat generalizability issues with small datasets is pretraining. For example, Yuan et al.127 and Han et al.128 pretrain convolutional neural networks using the ImageNet129 dataset to successfully classify risk in prostate tumors and differentiate between long- and short-term glioma survivors, respectively. As an alternative to pretraining on ImageNet, Wen et al.130 explore the possible benefits of pretraining using medical images. While their study ultimately found that ImageNet pretraining provided more accurate results, medical pretraining showed potential. As such, it could be useful to construct a large medical image database like ImageNet to further explore pretraining for medical problems using medical images. Zhang et al.131 explore another possible workflow for fine-tuning a network designed to classify breast cancer molecular subtypes from DCE-MRI data. Rather than relying on a separate, large dataset for pre-training, they separate their data into a training set and two testing sets – A and B. They then compare (1) testing the network with both A and B, (2) fine-tuning with B and testing with A, and (3) fine-tuning with A and testing with B. They conclude that finetuning with this method increases accuracy. Thus, in a situation where the dataset of interest is very small, initial network training could be completed on large, publicly available datasets, then fine-tuning and testing could be completed using the dataset of interest.

Many AI-based algorithms lack interpretability, thereby also limiting their clinical adoption. Furthermore, most AI-based approaches for outcome prediction are deployed with set parameters that govern their sensitivity and specificity. The patient-specific use of these models may require their optimization to fit the specific wishes of the patient, their family, and their clinical team. This patient-specific optimization creates an additional barrier to clinical deployment. The integration of AI-based prediction algorithms into the clinical workflow faces additional challenges as it has not been well established and currently generates additional work for the clinical team. This limits their adoption to clinics that have a robust computational infrastructure, clinicians who are willing to spend extra time generating the data, and ready access to the necessary data for the algorithm.

Discussion

AI-based methods have established some measure of success in several areas of MRI including image acquisition, reconstruction, registration, and segmentation, as well as assisting in diagnosis and prognosis. Some registration and segmentation techniques have even been approved by the FDA for clinical application69,91,92,132. However, while the application of AI techniques for MRI in cancer clearly has tremendous potential, three major challenges persist: (1) model generalizability, (2) model interpretability, and (3) establishing confidence in the output of an AI model. Indeed, these problems are common to many applications of AI in medicine.

The limited progress in being able to transport an AI method from one institute to another, and from one disease setting to another (i.e., generalizability), is heavily influenced by both the data and the devices employed to capture the data133. The wide variety of the available scanners (both from different manufacturers and then different models with a manufacturer), as well as the protocols they run, can further hamper generalizability as the data employed for training may not adequately sample all the acquisition scenarios encountered in the testing data set133,134. The lack of standardization in quality assurance and control (QA/QC) adds additional complexities135. Even when an AI method has had success in one clinical setting, it does not guarantee it will be successful when applied in another disease setting due to variations in patient characteristics and previously received treatments136. Thus, retraining the AI model is required and this can introduce nontrivial changes to the AI architecture or method of implementation. This is especially true in cancer, where the differences between diseases and the site of origin can introduce tremendous anatomical and physiological heterogeneities that may confound a previously trained AI model. It is increasingly recognized that each model should be evaluated with local data in the disease setting for which it is intended to be used137.

A fundamental issue with the majority of AI-based analysis is their limited “interpretability” in the sense of only providing a limited understanding of the relationships between model input and model output; that is, there is limited insight into how the AI model gets from cause to effect. This is an active area of investigation72,138,139 and is now well-recognized for being extremely important in domains that have high-consequence decisions like oncology140,141. For example, lack of interpretability generates problems when trying to identify optimal interventions for a particular patient where it is critical to understand why an AI model selects a particular therapeutic regimen over another. In particular, for an AI model built on population-based MRI data, does the training data set adequately capture the unique characteristics of the features in the individual’s MRI data? One attractive way forward is to link mechanism-based modeling with AI methods and scientific machine learning in which known/established biological and physical laws can be explicitly incorporated in the AI algorithm142,143,144. This can have the additional benefit of increasing confidence in the method.

The challenge in establishing confidence is not only related to the lack of model generalizability and interpretability, but also concern over the ethical issues associated with applying AI techniques to healthcare data as well as maintaining patient privacy and data security. This is particularly true with medical imaging data in which detailed anatomical features can be rendered in 3D. Importantly, once introduced in the clinical workflow, the performance of the AI tool must be continuously monitored as the data inputs are adjusted with new imaging hardware, software, and methods of image acquisition and subsequent analysis. More generally, the Office of Science and Technology Policy has published a white paper entitled, “A Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights”145 designed to guide the safe, effective, and unbiased development and application of AI.

Beyond the issues related to generalizability, interpretability, and confidence enumerated above, there may be fundamental limitations to what AI can contribute to cancer imaging. For example, it is important to note that every AI-based method requires a training set and since cancer is notoriously heterogeneous across both space and time, there are fundamental limits to what a population-based method can achieve. Indeed, this problem manifests itself in everything from image reconstruction to predicting response if the specific details of the pathology under investigation are not well-characterized in the training set. For a disease as heterogeneous as cancer, and an imaging modality as flexible as MRI, this seems to be a difficult problem to overcome with an AI-only approach.

Conclusion

AI has shown promise in accelerating image acquisition and reconstruction methods to maintain high spatial resolution in a fraction of the time typically required to obtain such an image. It has also been a useful tool for improving image segmentation and registration, as well as offering valuable results in both diagnostic and prognostic settings. However, questions remain about the interpretability and generalizability of these techniques, especially when a method is ported from one disease setting to another or, even, from one institution to another institution. The dearth of robust QA/QC and ethics-ensuring methods means that much work is left to be done to maintain patient safety given the current status of AI techniques in cancer imaging and healthcare. Finally, questions concerning fundamental limitations for any method that requires a large training dataset remain.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Chen, Y. et al. AI-based reconstruction for Fast MRI—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Proc. IEEE 110, 224–245 (2022).

Shimron, E. & Perlman, O. AI in MRI: Computational frameworks for a faster, optimized, and automated imaging workflow. Bioengineering 10, 492 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. Artificial intelligence powered advancements in upper extremity joint MRI: A review. Heliyon 10, e28731 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Artificial intelligence in multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging: A review. Med. Phys. 49, https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15936 (2022).

McCarthy, J., Minsky, M. L., Rochester, N. & Shannon, C. E. A proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, August 31, 1955. AI Mag. 27, 12 (2006).

Ongie, G. et al. Deep learning techniques for inverse problems in imaging. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Inf. Theory 1, 39–56 (2020).

Shen, D., Wu, G. & Suk, H. I. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 19, 221–248 (2017).

Lundervold, A. S. & Lundervold, A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Z. F. ür. Med Phys. 29, 102–127 (2019).

Karimi, D., Dou, H., Warfield, S. K. & Gholipour, A. Deep learning with noisy labels: Exploring techniques and remedies in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 65, 101759 (2020).

Iglesias, J. E. et al. SynthSR: A public AI tool to turn heterogeneous clinical brain scans into high-resolution T1-weighted images for 3D morphometry. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd3607 (2023).

De Leeuw Den Bouter, M. L. et al. Deep learning-based single image super-resolution for low-field MR brain images. Sci. Rep. 12, 6362 (2022).

Guan, H. & Liu, M. Domain adaptation for medical image analysis: a survey. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 1173–1185 (2022).

Tamir, J. I. et al. Computational MRI with physics-based constraints: application to multicontrast and quantitative imaging. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 37, 94–104 (2020).

Dang, H. N. et al. MR‐zero meets RARE MRI: Joint optimization of refocusing flip angles and neural networks to minimize T 2 ‐induced blurring in spin echo sequences. Magn. Reson Med 90, 1345–1362 (2023).

Loktyushin, A. et al. MRzero - Automated discovery of MRI sequences using supervised learning. Magn. Reson Med 86, 709–724 (2021).

Aggarwal, H. K. & Jacob, M. J-MoDL: Joint model-based deep learning for optimized sampling and reconstruction. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process 14, 1151–1162 (2020).

Bahadir C. D., Dalca A. V. & Sabuncu M. R. Learning-Based Optimization of the Under-Sampling Pattern in MRI. In: Chung A. C. S., Gee J. C., Yushkevich P. A., Bao S., eds. Information Processing in Medical Imaging. Vol 11492. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer International Publishing; 780–792. (2019).

Ravula S., Levac B., Jalal A., Tamir J. I. & Dimakis A. G. Optimizing Sampling Patterns for Compressed Sensing MRI with Diffusion Generative Models. Published online. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2306.03284 (2023).

Wang, G., Luo, T., Nielsen, J. F., Noll, D. C. & Fessler, J. A. B-spline parameterized joint optimization of reconstruction and K-Space Trajectories (BJORK) for accelerated 2D MRI. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 2318–2330 (2022).

Lustig, M., Donoho, D. & Pauly, J. M. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 58, 1182–1195 (2007).

Aggarwal, H. K., Mani, M. P. & Jacob, M. MoDL: Model-based deep learning architecture for inverse problems. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 394–405 (2019).

Hammernik, K. et al. Learning a variational network for reconstruction of accelerated MRI data. Magn. Reson. Med. 79, 3055–3071 (2018).

Jalal A. et al. Robust Compressed Sensing MRI with Deep Generative Priors. In: Ranzato M., Beygelzimer A., Dauphin Y., Liang P. S., Vaughan J. W., eds. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Vol 34. Curran Associates, Inc.;14938–14954. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2021/file/7d6044e95a16761171b130dcb476a43e-Paper.pdf. (2021).

Luo, G., Blumenthal, M., Heide, M. & Uecker, M. Bayesian MRI reconstruction with joint uncertainty estimation using diffusion models. Magn. Reson. Med. 90, 295–311 (2023).

Johnson, P. M. et al. Deep learning reconstruction enables prospectively accelerated clinical knee MRI. Radiology 307, e220425 (2023).

Chen, F. et al. Variable-density single-shot fast spin-echo MRI with deep learning reconstruction by using variational networks. Radiology 289, 366–373 (2018).

Yankeelov, T. & Gore, J. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in oncology: theory, data acquisition, analysis, and examples. Curr. Med. Imaging Rev. 3, 91–107 (2007).

Gong, E., Pauly, J. M., Wintermark, M. & Zaharchuk, G. Deep learning enables reduced gadolinium dose for contrast‐enhanced brain MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 48, 330–340 (2018).

Muckley, M. J. et al. Results of the 2020 fastMRI challenge for machine learning MR image reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 40, 2306–2317 (2021).

Daye, D. et al. Implementation of clinical artificial intelligence in radiology: who decides and how? Radiology 305, 555–563 (2022).

Hoebel, K. V. et al. Expert-centered evaluation of deep learning algorithms for brain tumor segmentation. Radio. Artif. Intell. 6, e220231 (2024).

Cè, M. et al. Artificial Intelligence in brain tumor imaging: a step toward personalized medicine. Curr. Oncol. 30, 2673–2701 (2023).

Egger, J. et al. GBM Volumetry using the 3D Slicer Medical Image Computing Platform. Sci. Rep. 3, 1364 (2013).

Lambert, S. I. et al. An integrative review on the acceptance of artificial intelligence among healthcare professionals in hospitals. Npj Digit. Med. 6, 111 (2023).

Baroudi, H. et al. Automated contouring and planning in radiation therapy: what is ‘Clinically Acceptable’? Diagnostics 13, 667 (2023).

Pal, R. et al. Lumbar Spine Tumor Segmentation and Localization in T2 MRI Images Using AI. Published online. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2405.04023 (2024).

Kundal, K., Rao, K. V., Majumdar, A., Kumar, N. & Kumar, R. Comprehensive benchmarking of CNN-based tumor segmentation methods using multimodal MRI data. Comput. Biol. Med. 178, 108799 (2024).

Eppenhof, K. A. J. & Pluim, J. P. W. Pulmonary CT registration through supervised learning with convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 1097–1105 (2019).

Osman, A. F. I., Al-Mugren, K. S., Tamam, N. M. & Shahine, B. Deformable registration of magnetic resonance images using unsupervised deep learning in neuro-/radiation oncology. Radiat. Oncol. 19, 61 (2024).

Rudie, J. D. et al. Longitudinal assessment of posttreatment diffuse glioma tissue volumes with three-dimensional convolutional neural networks. Radio. Artif. Intell. 4, e210243 (2022).

Teuwen, J., Gouw, Z. A. R. & Sonke, J. J. Artificial intelligence for image registration in radiation oncology. Semin Radiat. Oncol. 32, 330–342 (2022).

Simonovsky M., Gutiérrez-Becker B., Mateus D., Navab N. & Komodakis N. A Deep Metric for Multimodal Registration. In: Ourselin S., Joskowicz L., Sabuncu M. R., Unal G., Wells W., eds. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2016. Vol 9902. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer International Publishing 10–18 (2016).

Haskins, G. et al. Learning deep similarity metric for 3D MR–TRUS image registration. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radio. Surg. 14, 417–425 (2019).

Mohseni Salehi, S. S., Khan, S., Erdogmus, D. & Gholipour, A. Real-time deep pose estimation with geodesic loss for image-to-template rigid registration. IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 38, 470–481 (2019).

Estienne, T. et al. Deep learning-based concurrent brain registration and tumor segmentation. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 14, 17 (2020).

Bakas S. et al. Identifying the Best Machine Learning Algorithms for Brain Tumor Segmentation, Progression Assessment, and Overall Survival Prediction in the BRATS Challenge. Published online November 5. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.38755 (2018).

Balakrishnan, G., Zhao, A., Sabuncu, M. R., Guttag, J. & Dalca, A. V. VoxelMorph: A Learning Framework for Deformable Medical Image Registration. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 1788–1800 (2019).

Dalca, A. V., Balakrishnan, G., Guttag, J. & Sabuncu, M. R. Unsupervised learning of probabilistic diffeomorphic registration for images and surfaces. Med. Image Anal. 57, 226–236 (2019).

Pellicer-Valero, O. J. et al. Deep learning for fully automatic detection, segmentation, and Gleason grade estimation of prostate cancer in multiparametric magnetic resonance images. Sci. Rep. 12, 2975 (2022).

Cardenas, C. E., Yang, J., Anderson, B. M., Court, L. E. & Brock, K. B. Advances in auto-segmentation. Semin Radiat. Oncol. 29, 185–197 (2019).

Warfield, S. K., Zou, K. H. & Wells, W. M. Validation of image segmentation by estimating rater bias and variance. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 366, 2361–2375 (2008).

Ramesh, K. K. D., Kumar, G. K., Swapna, K., Datta, D. & Rajest, S. S. A Review of Medical Image Segmentation Algorithms. EAI Endorsed Trans. Pervasive Health Technol. 7, e6 (2021).

Jungo A. et al. On the Effect of Inter-observer Variability for a Reliable Estimation of Uncertainty of Medical Image Segmentation. In: Frangi A. F., Schnabel J. A., Davatzikos C., Alberola-López C., Fichtinger G., eds. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018. Vol 11070. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer International Publishing; 682–690. (2018).

Renard, F., Guedria, S., Palma, N. D. & Vuillerme, N. Variability and reproducibility in deep learning for medical image segmentation. Sci. Rep. 10, 13724 (2020).

Tixier, F., Um, H., Young, R. J. & Veeraraghavan, H. Reliability of tumor segmentation in glioblastoma: Impact on the robustness of MRI‐radiomic features. Med. Phys. 46, 3582–3591 (2019).

Poirot, M. G. et al. Robustness of radiomics to variations in segmentation methods in multimodal brain MRI. Sci. Rep. 12, 16712 (2022).

Koçak, B. Key concepts, common pitfalls, and best practices in artificial intelligence and machine learning: focus on radiomics. Diagn. Inter. Radio. 28, 450–462 (2022).

Kocak, B., Durmaz, E. S., Ates, E. & Kilickesmez, O. Radiomics with artificial intelligence: a practical guide for beginners. Diagn. Inter. Radio. 25, 485–495 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. What matters in radiological image segmentation? Effect of segmentation errors on the diagnostic related features. J. Digit Imaging 36, 2088–2099 (2023).

Horvat, N., Papanikolaou, N. & Koh, D. M. Radiomics beyond the hype: a critical evaluation toward oncologic clinical use. Radio. Artif. Intell. 6, e230437 (2024).

Fu, Y. et al. Deep learning in medical image registration: a review. Phys. Med. Biol. 65, 20TR01 (2020).

Mårtensson, G. et al. The reliability of a deep learning model in clinical out-of-distribution MRI data: A multicohort study. Med. Image Anal. 66, 101714 (2020).

Bi, W. L. et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: Clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69, 127–157 (2019).

Wildeboer, R. R., Van Sloun, R. J. G., Wijkstra, H. & Mischi, M. Artificial intelligence in multiparametric prostate cancer imaging with focus on deep-learning methods. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 189, 105316 (2020).

Jones, M. A., Islam, W., Faiz, R., Chen, X. & Zheng, B. Applying artificial intelligence technology to assist with breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis prediction. Front. Oncol. 12, 980793 (2022).

Chakrabarty, S. et al. MRI-based identification and classification of major intracranial tumor types by using a 3D Convolutional Neural Network: A retrospective multi-institutional analysis. Radio. Artif. Intell. 3, e200301 (2021).

Saha, A., Hosseinzadeh, M. & Huisman, H. End-to-end prostate cancer detection in bpMRI via 3D CNNs: Effects of attention mechanisms, clinical priori and decoupled false positive reduction. Med. Image Anal. 73, 102155 (2021).

Giger, M. L. Machine learning in medical imaging. J. Am. Coll. Radio. 15, 512–520 (2018).

Twilt, J. J., Van Leeuwen, K. G., Huisman, H. J., Fütterer, J. J. & De Rooij, M. Artificial intelligence based algorithms for prostate cancer classification and detection on magnetic resonance imaging: a narrative review. Diagnostics 11, 959 (2021).

Antropova, N., Huynh, B. Q. & Giger, M. L. A deep feature fusion methodology for breast cancer diagnosis demonstrated on three imaging modality datasets. Med. Phys. 44, 5162–5171 (2017).

Sardanelli, F. et al. The paradox of MRI for breast cancer screening: high-risk and dense breasts—available evidence and current practice. Insights Imaging 15, 96 (2024).

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 206–215 (2019).

Hatherley, J., Sparrow, R. & Howard, M. The virtues of interpretable medical AI. Camb. Q Health Ethics 33, 323–332 (2024).

Salahuddin, Z., Woodruff, H. C., Chatterjee, A. & Lambin, P. Transparency of deep neural networks for medical image analysis: A review of interpretability methods. Comput. Biol. Med. 140, 105111 (2022).

Band, S. et al. Application of explainable artificial intelligence in medical health: A systematic review of interpretability methods. Inf. Med. Unlocked 40, 101286 (2023).

Champendal, M., Müller, H., Prior, J. O. & Dos Reis, C. S. A scoping review of interpretability and explainability concerning artificial intelligence methods in medical imaging. Eur. J. Radio. 169, 111159 (2023).

Lipkova, J. et al. Artificial intelligence for multimodal data integration in oncology. Cancer Cell 40, 1095–1110 (2022).

Paverd, H., Zormpas-Petridis, K., Clayton, H., Burge, S. & Crispin-Ortuzar, M. Radiology and multi-scale data integration for precision oncology. Npj Precis. Oncol. 8, 158 (2024).

Metzcar, J., Jutzeler, C. R., Macklin, P., Köhn-Luque, A. & Brüningk, S. C. A review of mechanistic learning in mathematical oncology. Front. Immunol. 15, 1363144 (2024).

Lorenzo, G. et al. Patient-specific, mechanistic models of tumor growth incorporating artificial intelligence and big data. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 26, 529–560 (2024).

Bosque, J. J. et al. Metabolic activity grows in human cancers pushed by phenotypic variability. iScience 26, 106118 (2023).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Zhang, R. Z. et al. Personalized predictions of Glioblastoma infiltration: Mathematical models, Physics-Informed Neural Networks and multimodal scans. Med. Image Anal. 101, 103423 (2025).

Elmarakeby, H. A. et al. Biologically informed deep neural network for prostate cancer discovery. Nature 598, 348–352 (2021).

Lagergren, J. H., Nardini, J. T., Baker, R. E., Simpson, M. J. & Flores, K. B. Biologically-informed neural networks guide mechanistic modeling from sparse experimental data. PLOS Comput. Biol. 16, e1008462 (2020).

Witowski, J. et al. Improving breast cancer diagnostics with deep learning for MRI. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabo4802 (2022).

Meyer‐Base, A. et al. AI-enhanced diagnosis of challenging lesions in breast MRI: a methodology and application primer. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 54, 686–702 (2021).

Rosenkrantz, A. B. & Taneja, S. S. Radiologist, be aware: ten pitfalls that confound the interpretation of multiparametric prostate MRI. Am. J. Roentgenol. 202, 109–120 (2014).

Cao, R. et al. Joint prostate cancer detection and Gleason score prediction in mp-MRI via FocalNet. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 2496–2506 (2019).

Bashkanov, O. et al. Automatic detection of prostate cancer grades and chronic prostatitis in biparametric MRI. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 239, 107624 (2023).

Wang, J. Y. et al. Stratified assessment of an FDA-cleared deep learning algorithm for automated detection and contouring of metastatic brain tumors in stereotactic radiosurgery. Radiat. Oncol. 18, 61 (2023).

Jiang, Y., Edwards, A. V. & Newstead, G. M. Artificial Intelligence applied to breast MRI for improved diagnosis. Radiology 298, 38–46 (2021).

Khan, B. et al. Drawbacks of artificial intelligence and their potential solutions in the healthcare sector. Biomed. Mater. Devices 1, 731–738 (2023).

Pati, S. et al. Federated learning enables big data for rare cancer boundary detection. Nat. Commun. 13, 7346 (2022).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Gutman, D. A. et al. MR imaging predictors of molecular profile and survival: multi-institutional study of the TCGA Glioblastoma data set. Radiology 267, 560–569 (2013).

Emblem, K. E. et al. A generic support vector machine model for Preoperative Glioma Survival Associations. Radiology 275, 228–234 (2015).

Cox, D. R. Regression models and life-tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 34, 187–202 (1972).

Lee, H. W. et al. Novel multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-based deep learning and clinical parameter integration for the prediction of long-term biochemical recurrence-free survival in prostate cancer after Radical Prostatectomy. Cancers 15, 3416 (2023).

Ishwaran H., Kogalur U. B., Blackstone E. H. & Lauer M. S. Random survival forests. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2, https://doi.org/10.1214/08-AOAS169 (2008).

Xu, R. & Wunsch, D. C. Clustering algorithms in biomedical research: a review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 3, 120–154 (2010).

Andersen, E. K. F., Kristensen, G. B., Lyng, H. & Malinen, E. Pharmacokinetic analysis and k-means clustering of DCEMR images for radiotherapy outcome prediction of advanced cervical cancers. Acta Oncol. 50, 859–865 (2011).

Anwar, S. M. et al. Medical image analysis using convolutional neural networks: a review. J. Med. Syst. 42, 226 (2018).

Jang, B. S., Jeon, S. H., Kim, I. H. & Kim, I. A. Prediction of Pseudoprogression versus progression using machine learning algorithm in Glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 8, 12516 (2018).

Zhou, X. et al. Attention mechanism based multi-sequence MRI fusion improves prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Radiat. Oncol. 18, 175 (2023).

Vaswani A., et al. Attention is All you Need. In: Guyon I., Luxburg U. V., Bengio S., et al., eds. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Vol 30. Curran Associates, Inc.; https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Paper.pdf. (2017).

Macyszyn, L. et al. Imaging patterns predict patient survival and molecular subtype in glioblastoma via machine learning techniques. Neuro-Oncol. 18, 417–425 (2016).

Kickingereder, P. et al. Radiomic profiling of Glioblastoma: Identifying an imaging predictor of patient survival with improved performance over established clinical and radiologic risk models. Radiology 280, 880–889 (2016).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Van Houdt, G., Mosquera, C. & Nápoles, G. A review on the long short-term memory model. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 5929–5955 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Machine learning in prostate MRI for prostate cancer: current status and future opportunities. Diagnostics 12, 289 (2022).

Khan, N., Adam, R., Huang, P., Maldjian, T. & Duong, T. Q. Deep learning prediction of pathologic complete response in breast cancer using MRI and other clinical data: a systematic review. Tomography 8, 2784–2795 (2022).

Cè M., et al. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer imaging: risk stratification, lesion detection and classification, treatment planning and prognosis—a narrative review. Explor Target Anti-Tumor Ther. Published online December 27, 795–816. (2022)

Zhu, M. et al. Artificial intelligence in the radiomic analysis of glioblastomas: A review, taxonomy, and perspective. Front Oncol. 12, 924245 (2022).

Zhang, B., Shi, H. & Wang, H. Machine learning and AI in cancer prognosis, prediction, and treatment selection: a critical approach. J. Multidiscip. Health 16, 1779–1791 (2023).

Papadimitroulas, P. et al. Artificial intelligence: Deep learning in oncological radiomics and challenges of interpretability and data harmonization. Phys. Med. 83, 108–121 (2021).

Marzi, C. et al. Efficacy of MRI data harmonization in the age of machine learning: a multicenter study across 36 datasets. Sci. Data 11, 115 (2024).

Basu, K., Sinha, R., Ong, A. & Basu, T. Artificial intelligence: How is it changing medical sciences and its future? Indian J. Dermatol 65, 365 (2020).

Rauniyar, A. et al. Federated learning for medical applications: a taxonomy, current trends, challenges, and future research directions. IEEE Internet Things J. 11, 7374–7398 (2024).

Guan, H., Yap, P. T., Bozoki, A. & Liu, M. Federated learning for medical image analysis: A survey. Pattern Recognit. 151, 110424 (2024).

Andaloussi M. A., Maser R., Hertel F., Lamoline F. & Husch A. D. Exploring Adult Glioma through MRI: A Review of Publicly Available Datasets to Guide Efficient Image Analysis. Published online. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2409.00109 (2024).

Sunoqrot, M. R. S., Saha, A., Hosseinzadeh, M., Elschot, M. & Huisman, H. Artificial intelligence for prostate MRI: open datasets, available applications, and grand challenges. Eur. Radio. Exp. 6, 35 (2022).

Kilintzis, V. et al. Public data homogenization for AI model development in breast cancer. Eur. Radio. Exp. 8, 42 (2024).

Kosvyra, A., Filos, D. T., Fotopoulos, D. T. H., Tsave, O. & Chouvarda, I. Toward ensuring data quality in multi-site cancer imaging repositories. Information 15, 533 (2024).

Bedard, P. L., Hansen, A. R., Ratain, M. J. & Siu, L. L. Tumour heterogeneity in the clinic. Nature 501, 355–364 (2013).

Booth, C. M., Karim, S. & Mackillop, W. J. Real-world data: towards achieving the achievable in cancer care. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16, 312–325 (2019).

Yuan, Y. et al. Prostate cancer classification with multiparametric MRI transfer learning model. Med. Phys. 46, 756–765 (2019).

Han, W. et al. Deep transfer learning and radiomics feature prediction of survival of patients with high-grade Gliomas. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 41, 40–48 (2020).

Deng J., et al. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In: 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE; 248–255 (2009).

Wen, Y., Chen, L., Deng, Y. & Zhou, C. Rethinking pre-training on medical imaging. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 78, 103145 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Prediction of breast cancer molecular subtypes on DCE-MRI using convolutional neural network with transfer learning between two centers. Eur. Radio. 31, 2559–2567 (2021).

US Food and Drug Administration. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Medical Devices. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-aiml-enabled-medical-devices. (2024).

Eche, T., Schwartz, L. H., Mokrane, F. Z. & Dercle, L. Toward generalizability in the deployment of artificial intelligence in radiology: role of computation stress testing to overcome underspecification. Radio. Artif. Intell. 3, e210097 (2021).

Futoma, J., Simons, M., Panch, T., Doshi-Velez, F. & Celi, L. A. The myth of generalisability in clinical research and machine learning in health care. Lancet Digit Health 2, e489–e492 (2020).

Adjeiwaah, M., Garpebring, A. & Nyholm, T. Sensitivity analysis of different quality assurance methods for magnetic resonance imaging in radiotherapy. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 13, 21–27 (2020).

Yang Y., Zhang H., Gichoya J. W., Katabi D. & Ghassemi, M. The limits of fair medical imaging AI in real-world generalization. Nat. Med. Published online June 28, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03113-4 (2024).

Albahri, A. S. et al. A systematic review of trustworthy and explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: Assessment of quality, bias risk, and data fusion. Inf. Fusion 96, 156–191 (2023).

Linardatos, P., Papastefanopoulos, V. & Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: A review of machine learning interpretability methods. Entropy 23, 18 (2020).

Murdoch, W. J., Singh, C., Kumbier, K., Abbasi-Asl, R. & Yu, B. Definitions, methods, and applications in interpretable machine learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 22071–22080 (2019).

Banegas-Luna, A. J. et al. Towards the interpretability of machine learning predictions for medical applications targeting personalised therapies: a cancer case survey. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4394 (2021).

Kuenzi, B. M. et al. Predicting drug response and synergy using a deep learning model of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 38, 672–684.e6 (2020).

Wysocka, M., Wysocki, O., Zufferey, M., Landers, D. & Freitas, A. A systematic review of biologically-informed deep learning models for cancer: fundamental trends for encoding and interpreting oncology data. BMC Bioinforma. 24, 198 (2023).

Cuomo, S. et al. Scientific machine learning through physics–informed neural networks: where we are and what’s next. J. Sci. Comput 92, 88 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Biology-guided deep learning predicts prognosis and cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Commun. 14, 5135 (2023).

White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights/ (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Cancer Institute for funding through 1R01CA260003, U24CA226110, U01CA253540, and P30CA016672. We thank the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas for funding through RP220225. We thank the National Science Foundation for funding through CCF-2239687 (CAREER), IFML 2019844, AF 1901292. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DE2137420. This project was supported by the Resources of the Image Guided Cancer Therapy Research Program at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center as well as the Joint Center for Computational Oncology (a collaboration between the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Texas Advanced Computing Center). The project was also supported by the Tumor Measurement Initiative at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. We acknowledge the support from “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434), fellowship code is LCF/BQ/PI23/11970033.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions