Abstract

Computerized features derived from medical imaging have shown great potential in building machine learning models for predicting and prognosticating disease outcomes. However, the performance of such models depends on the robustness of extracted features to institutional and acquisition variability inherent in clinical imaging. To address this challenge, we propose Variability Regularized Feature Selection (VaRFS), a framework that integrates feature variability as a regularization term to identify features that are both discriminable between outcome groups and generalizable across imaging differences. VaRFS employs a novel sparse regularization strategy within the within the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) framework, for which we analytically confirm convergence guarantees as well as present an accelerated proximal variant for computational efficiency. We evaluated VaRFS across five clinical applications using over 700 multi-institutional imaging datasets, including disease detection, treatment response characterization, and risk stratification. Compared to three conventional feature selection methods, VaRFS yielded consistently higher classifier AUCs in hold-out validation; balancing reproducibility, sparsity, and discriminability in medical imaging feature selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances in computerized analysis of medical images include deriving computational features toward building machine learning models which can accurately predict or prognosticate disease outcomes1,2. However, variations in image acquisition parameters, scanner types, and institutional practices can significantly affect the appearance of medical images3,4,5, as a result of which the same tissue region may be represented differently in clinically acquired scans. As a result, even minor differences in scanner hardware, reconstruction algorithms, acquisition protocols, or patient positioning can substantially alter feature values across sites or sessions, independent of underlying biology.6,7 Similar instability can arise from differences in annotations or identification of regions of interest (ROI), additionally impacting reproducibility of extracted features.8,9 The resulting fluctuations in computationally extracted medical image features are largely unrelated to the underlying disease conditions, and result in classifier models that do not accurately generalize between medical institutions simply due to slight variations in scanner calibration and acquisition protocols. It has thus become increasingly crucial to determine the variability10 of computerized features from medical images, both within and between institutions, across different acquisition protocols11,12, as well as in test-retest settings7. The key challenge is thus to identify medical image features that are simultaneously reproducible13 to cross-domain variability as well as discriminable in order to ensure the generalizability14 and clinical utility of associated classifier models, especially when evaluated in the context of new, unseen medical imaging cohorts.

The most popularly used feature selection methods in medical imaging studies include minimum redundancy maximum relevance (mRMR)15, Wilcoxon rank-sum testing (WLCX)16, and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)17.By surveying over 50 recent studies (summarized in Supplementary Table 2), more than 80% were found to utilize one or more of these three specific techniques as illustrated in Fig. 1(a). Notably, these methods primarily focus on identifying a minimal set of discriminable features, potentially overlooking the reproducibility or variability of these features. Figure 1(b) highlights that only about 30% of medical imaging studies have explicitly incorporated variability-based screening (e.g., hard thresholds), while over 70% did not assess feature variability at all.

Distribution of (a) feature selection methods, (b) and feature screening strategies employed. c Lack of consensus across medical imaging studies for “screening” features based on variability (using IS, ICC, or CV measures) or discriminability (based on AUC), illustrated via distribution of widely varying thresholds used.

Multiple approaches have been proposed for quantifying feature variability in the context of medical imaging. Statistical measures including intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC)18, instability score (IS)19, or the coefficient of variation (CV)20 have been utilized as feature reproducibility measures. Correspondingly, measures such as classifier AUC have been used to quantify feature discriminability21,22. These measures are used to “screen” features by determining a cut-off threshold at which features are considered discriminable or reproducible23. However, threshold criteria for both reproducibility and discriminability measures are often empirically determined for a given study and indeed, can often vary significantly between studies. Figure 1(c) illustrates the distribution of threshold values reported across 40 recent studies which have utilized different variability measures (IS, ICC, and CV) and a discriminability measure (AUC). It can be observed that a wide spectrum of threshold values have been utilized, with no clear consensus on the optimal thresholds to define a discriminable and reproducible feature set.

Utilizing empirically determined thresholds to screen medical image features may be further complicated when attempting to optimize for multiple sources of variability. For instance, different variability measures are often used to quantify batch effects (such as IS19) vs quantifying differences due to annotation sources (such as ICC24,25). The interplay between multiple sources of variability is likely not appropriately accounted for if each measure is independently used to filter out medical image features. Similarly, if feature discriminability and reproducibility are evaluated independently of each other, features that have only marginal variability but may still be highly discriminable could be filtered out.

To illustrate this relationship between discriminability and variability, Fig. 2 presents 2D scatter plots of feature discriminability (Y-axis) vs two different measures of feature variability (X-axes), where each point corresponds to a computerized image feature. Identifying features that are both highly discriminatory and highly reproducible would involve determining which features meet pre-defined thresholds (TH1, …, TH8, horizontal and vertical dash lines) for each measure being considered. This would then yield the optimal feature sets highlighted via the blue boxes on each plot. Notably this set of optimal features can be seen to comprise different feature families in each plot (primarily F5 in Fig. 2(a) but primarily F4 in Fig. 2(b)), due to differences in feature trends between the two variability measures. There are also differences in the sub-optimal feature sets identified in each plot (low in discriminability and reproducibility), highlighted via red boxes. This suggests a significant challenge in optimally determining a trade-off between discriminability and reproducibility for computerized features, in terms of not only identifying the appropriate variability measure (which depends on how many imaging modalities, scanners, imaging protocols, or institutions are being considered) as well as determining the best threshold value toward identifying the most discriminatory and reproducible feature set for disease characterization.

In this work, we present a novel Variability Regularized Feature Selection (VaRFS) approach, which simultaneously attempts to ensure feature discriminability while also optimizing for feature variability across institutions, scanners, or acquisition settings; in the context of medical imaging data. An initial limited implementation of VaRFS was discussed in26, beyond which the current work incorporates multiple sources of variability, analytical evaluation of the convergence properties, as well a comprehensive comparison across larger multi-institutional data cohorts. Our novel optimization framework directly integrates feature reproducibility into the selection process through a variability-based soft penalty term. Unlike traditional methods that apply reproducibility screening as a hard pre-filter (e.g., removing features with variability “score” which does not meet a pre-specified threshold), our approach maintains a unified formulation that jointly accounts for variability and predictive power. This not only allows for finer control over feature variability but also minimizes the chance of prematurely excluding of marginally variable but highly informative features. The specific novel contributions of our current work are as follows:

-

1.

VaRFS integrates feature variability screening and feature selection into a single optimization function; overcoming the need for empirical selection of an appropriate threshold value per variability measure or cohort. VaRFS is also designed to ensure a better tradeoff between the three essential properties of a computerized medical image feature set: discriminability, sparsity, and reproducibility. By comparison, separating feature variability screening and feature selection could result in sub-optimal features being identified due to the elimination of highly discriminatory features that do not meet empirically determined variability threshold criteria. As VaRFS integrates these two processes into a single optimization function, the feature selection process can be made more efficient, reliable, and flexible.

-

2.

The objective function of VaRFS aims to maximize the discriminability of the selected features, with additional regularization terms to impose constraints on sparsity and variability to ensure that the selected features are also sparse and reproducible. Towards this, VaRFS leverages the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) framework17, as it can easily assimilate supplementary regularization conditions27,28. As this extension may result in slow convergence due to large-valued regularization parameters, as well as careful tuning of the step size29,30, popular approaches such as coordinate descent31 and iterative shrinkage-thresholding algorithm32 may be sub-optimal. To address these limitations, we present a comprehensive analytical framework that leverages a novel class of proximal algorithms33 which are computationally efficient, easy to implement, and can handle non-smooth objective functions34. We analytically demonstrate how the incorporation of proximal algorithms into our unique extension of the LASSO framework can further be accelerated35 for faster convergence, which represents a significant advancement in the field of optimization.

-

3.

VaRFS provides a significant contribution to enabling clinical usage of machine learning models, specifically in addressing the challenging issue of optimally accounting for variability and reproducibility of computerized radiology image (or radiomic36) features. Toward this, VaRFS will be comprehensively compared against three routinely utilized feature selection approaches across five multi-institutional radiographic imaging cohorts involving challenging clinical problems including differentiating healthy and diseased samples, characterizing response to treatment, and as well as risk stratification; in both oncological (prostate, rectal cancer) and non-oncological (Crohn’s disease) settings.

Results

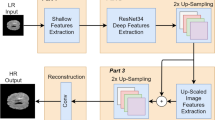

Experimental evaluation of VaRFS and alternative feature selection (FS) strategies were conducted using five different, multi-institutional, retrospectively accrued cohorts which were segregated into independent discovery and validation sets (see Table 1). The overall experimental workflow is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Experiment 1: comparing VaRFS against variability-screened feature selection methods

VaRFS was found to result in statistically significantly higher AUC values in all five cohorts for both discovery and hold-out validation, compared to any alternative FS approach. This suggests the integration of feature variability directly into the selection scheme can improve overall model performance, including multi-institutional validation. This is summarized via Table 2 in terms of the classifier performance for top-ranked radiomic features identified via each FS scheme (VaRFS, variability-screened mRMR, LASSO, and WLCX); for all five cohorts. Note these results are based on considering a single measure of variability at a time, e.g., results are presented for each of ICCdose, ISbatch, and ICCannot for C5. Supplementary Table 3 presents averaged performance across all cross-validation runs for each FS method, which further confirms the superior performance trends of VaRFS compared to other FS methods. This can also be noted when utilizing an LDA model to evaluate VaRFS against alternative FS methods, as summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

The results presented in Table 3 similarly summarize classifier performance for different FS strategies for all five cohorts, but when considering multiple measures of variability simultaneously. Radiomic features identified via VaRFS yielded statistically significant improvements in AUC values in all five cohorts (both in the discovery and hold-out validation sets) compared to any alternative FS strategy. Notably, accounting for multiple sources of variability via VaRFS can be seen to yield a further improvement in classifier AUC beyond using individual variability measures (compare Table 2 vs Table 3); corresponding to an overall 8–10% improvement for VaRFS over variability-screened FS approaches.

Figure 4 illustrates the chord diagram of the five top-ranked radiomic features selected via VaRFS as well as each of variability-screened mRMR, LASSO, and WLCX, together with their respective ranks, feature family (indicated via colors), and feature importance in terms of SHAP values (indicated via size). Chord connections highlight instances where a feature is common to two or more different methods, based on which the VaRFS feature set can be seen to include a majority of reproducible features (some of which had also been identified by other FS methods). Typically, VaRFS can be seen to have the most features in common with LASSO; which aligns with the commonality in their objective functions. The top-ranked VaRFS features identified here can be seen to correspond to radiomic descriptors from Laws, Gradient, and Haralick feature families. This resonates with previous findings from our group37,38,39,40 as well as others41,42 where these patterns have shown associations with specific disease biology or physiological characteristics (additional details in the Supplementary Materials).

Numeric labels (1–5) indicate the rank of each feature as determined by the corresponding feature selection method, colors correspond to feature family, while the size of each section represents the feature importance based on its SHAP value. Chord connections highlight instances where a feature is common to two or more different methods, while distinct symbols inside the chord sections indicate whether a feature is variable based on defined thresholds. The indices of these selected features are summarized in the Supplementary Table 1, which can be cross-referenced against Supplementary Data1.

Figure 5 depicts PCPs of discriminability/variability trends in these five top-ranked radiomic features selected via VaRFS within each cohort, each of which corresponds to a polyline that connects vertices between different parallel axes (representing the specific discriminability or variability value of that feature). It can be observed that many of the marginally variable features selected via VaRFS are not only highly discriminatory but also located in close proximity to the threshold (indicated via horizontal dashed lines). This suggests that a slight adjustment to this cutoff value would include or exclude critically useful features from consideration by different FS strategies (due to not meeting ad hoc variability criteria). The overall improved classifier performance achieved by incorporating these marginally variable features suggests they significantly augment the overall discriminability of the VaRFS model while not compromising on its generalizability to unseen data (consistently improved performance across discovery and validation).

Polylines correspond to individual features f1, …, f5 selected per cohort (colors indicate feature family, identical to Fig. 4), which in turn are composed of unbroken line segments that connect vertices between different parallel axes (representing the specific discriminability or variability value of that feature). Horizontal dashed lines indicate the threshold cutoff value for specific variability measures.

Figure 6 depicts an UpSet-style error decomposition for each cohort (C1-C5). For each of the 5 FS strategies evaluated by partitioning false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) into error sets, revealing both shared and method-specific failure modes. Both VaRFS variants can be seen to consistently produce fewer unique errors, with most misclassifications overlapping with those made by other methods. Across all cohorts, comparator FS methods (mRMR, WLCX) also demonstrate a markedly higher error rate compared to both VaRFS approaches, with the the smallest proportion of FPs/FNs associatd with VaRFS when considering multiple sources of variability. This pattern demonstrates that VaRFS does not appear to introduce new or unstable error modes compared other FS schemes; instead, it reduces method-specific errors while preserving discriminability.

Experiment 2: evaluating parameter sensitivity of VaRFS

Optimal classifier performance for VaRFS (highlighted in pink) in all five cohorts is observed when equally weighting β (variability) and λ (sparsity), though stable performance can be noted across a broad range of regularization parameters (see Supplementary Materials for a more detailed description). This can be seen in Fig. 7 via a 3D barplot of AUC values for the VaRFS feature set selected for each parameter combination of β and λ, when the corresponding RF model is evaluated in hold-out validation. The best overall AUC value in three cohorts corresponds to β = λ = 0.5 (and is very close to these values for the remaining two cohorts). Intuitively, classifier performance is seen to decline markedly for extreme parameter combinations (β < < λ or β > > λ) which indicates that both sparsity and variability terms are equally critical in the VaRFS cost function. This allows for more intelligent and reliable identification of feature sets which are simultaneously discriminable, sparse, and reproducible, thus reducing the chance of model overfitting while improving its generalizability.

Experiment 3: comparing regular vs accelerated versions of VaRFS

Accelerated VaRFS was found to converge at a faster rate as well as yield a lower minimization of the objective function compared to the regular implementation; in all five cohorts. Figure 8 presents optimization trends for the objective function J(θ) in (3), as computed by each of the regular (red lines) and accelerated versions (blue lines) of VaRFS over 100 iterations. When considering multiple measures of variability, the initialization of J(θ) is intuitively higher as compared to the single variability measure across all five cohorts. The visualization of C5 with three different sources of variability emphasizes this point, as the initialization of the J(θ) here has the highest value across all cohorts. VaRFS was also found to be more computationally efficient (average runtime of 124 seconds for regular, 79 seconds for accelerated) in comparison to both mRMR (614 secs runtime) and WLCX (412 secs runtime), while performing only marginally worse than LASSO (132 secs runtime) in all five cohorts. These results suggest that the use of proximal algorithms, rather than primal-dual methods43 or projection onto the convex sets44, are an appropriate choice for VaRFS as it includes alternating direction method of multipliers45 which has been shown an efficient and computationally cheaper approach.

Building on these advantages, the accelerated proximal algorithm for optimizing the VaRFS objective function allows for more efficient solving of a convex but non-smooth optimization problem via the use of a momentum term that helps it converge faster46. These results are also inline with previous studies47,48,49; demonstrated here for the first time in the context of radiomics and medical image analysis.

Discussion

In this study, we presented a novel radiomic feature selection scheme, Variability Regularized Feature Selection (VaRFS) which represents a first effort at integrating feature variability as a generalizable regularization term directly into the optimization function used to select a sparse and discriminable set of features. Radiomic features selected via VaRFS achieved significantly higher classification performance compared to three routinely utilized feature selection approaches across five multi-institutional radiographic imaging cohorts involving challenging clinical problems including differentiating healthy and diseased samples, characterizing response to treatment, and as well as risk stratification. We were additionally able to demonstrate the computational efficiency of the VaRFS approach as well as examine how exploiting the trade-offs in feature discriminability and variability can ensure improved model performance.

To enhance the robustness and generalizability of machine learning models in medical image analysis, there has been increasing recognition of the need to consider the reproducibility of radiomic features given their sensitivity to acquisition parameters11 and batch effects9,50. Neglecting feature reproducibility can lead to an increased risk of false positive associations and type I errors7. Recent efforts in this regard have largely adopted an independent feature screening approach prior to feature selection21,23,51. These approaches typically utilize thresholding of variability measures to omit any features which do not meet prespecified criteria. This is because popular feature selection approaches (LASSO, mRMR, and WLCX) have not been explicitly designed to account for variability, but rather only for sparsity and discriminability. Feature screening can be also seen to suffer similar issues to dichotomizing continuous variables52, such as loss of information, reduced statistical power, and increased risk of false positives. It is also worth noting that blindly removing unstable features (without regard to their discriminability) or simply retaining all features (without regard to their reproducibility) based on pre-specified thresholds may not result in an optimal, generalizable feature set.

In order to account for these issues, VaRFS simultaneously optimizes for feature contributions in terms of discriminability, sparsity, and reproducibility. Unlike traditional methods which rely on threshold-based variability screening, VaRFS directly optimizes for feature variability together with sparsity and discriminability, offering a more principled alternative to exhaustive threshold parameter tuning. Furthermore, the features selected by VaRFS can be seen to represent an optimal trade-off between different variability measures, while not compromising on its ability to identify a complementary suite of features and patterns in the data. This is borne out in our experimental results, where radiomic features selected via VaRFS yielded significantly higher classification performance compared to features selected after variability screening; suggesting the significant advantages enabled by developing an approach which can simultaneously optimize for sparsity, discriminability, and reproducibility rather than considering each of these factors independently. VaRFS thus offers a more efficient and effective method for feature selection which could ultimately improve the clinical translation and practical utility of radiomics-based models.

We do acknowledge some limitations to our study. While considering five multi-institutional cohorts totaling over 700 patient datasets from 12 different institutions, we primarily considered binary classification problems in specific disease use-cases using MRI or CT scans. These results will require further confirmation in other diseases, when analyzing other radiomic feature families, as well as when considering other imaging modalities (e.g., PET, digital pathology). Our experiments did not incorporate any prior knowledge about feature variability, which was instead empirically determined on the fly within our specific cohorts. This was done primarily to ensure an even playing field when comparing VaRFS with alternative feature selection and screening approaches. Our selection of comparators in the current study was based on their wide usage in the medical imaging and radiomics literature, wherein WLCX, LASSO, and mRMR remain the most widely utilized for feature selection. Additional comparator FS techniques which could have been considered by us include tree-based importance measures53, ensemble-based strategies54, or ElasticNet55; which will be a subject for future work. Prior studies23,25 have linked robust radiomic features to clinical and biological endpoints. Understanding the relationship between biological interpretability and the variability characteristics of radiomic features will be a key direction for future research, building on the methodological development of VaRFS undertaken in the current study.

In the future, we plan to extend the VaRFS framework in order to incorporate the concept of reproducibility into deep learning approaches. We will also examine how to incorporate priors in terms of which feature families to utilize, as well as extend VaRFS for use in multi-class and continuous regression problems.

Methods

Overview of VaRFS

All the data are assumed to be real-valued. Vectors and matrices are marked by boldface lower-case letters and upper-case bold, respectively. Additional notation used in this work is summarized in Table 4.

Consider S data sources (e.g. institutions, batches, scanners), each of which are associated with the feature matrix \({{\bf{X}}}_{i}=[{{\bf{x}}}_{i}^{1}\ldots {{\bf{x}}}_{i}^{j}\ldots {{\bf{x}}}_{i}^{m}]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{n}_{i}\times m}\), where \({{\bf{x}}}_{i}^{j}\) is the feature vector for the ith data source and the jth feature. m represents the total number of features (assumed to be the same for all S data sources) while ni corresponds to the number of samples from the ith source, respectively. Let \({{\bf{y}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{n}_{i}\times 1}\) be the corresponding label vector for ni samples. Accumulated feature values over all samples and all cohorts can be denoted via \({\bf{X}}={[{{\bf{X}}}_{1}\ldots {{\bf{X}}}_{S}]}^{T}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{n\times m}\) where \(n=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{S}{n}_{i}\).

Problem statement for feature selection via LASSO

Finding a user-specified number of discriminative features (denoted via the level of sparsity, c) can be cast as a constrained optimization problem as follows56:

where \({\boldsymbol{\theta }}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m}\) is the coefficient vector reflecting the contribution of each feature. This non-smooth combinatorial optimization problem is NP-hard57. A common alternative for (1) is to consider the convex relaxation based on the ℓ1 norm, which corresponds to the LASSO equation17, written as:

where λ is the regularization parameter.

Development of VaRFS

Radiomic features are known to vary between data sources due to intra-site, inter-site, or test/retest differences including changes in the device, modality, sequence, compartment, patient, or laboratory settings36. This variability is typically quantified via different statistical measures (e.g. IS, ICC, CV).

Based on the types of variability being considered, denoted via v ∈ {1, …, V} (e.g., batch effects, annotation differences), we define the feature variability vector as \({{\bf{u}}}_{v}={\left[{u}_{v}^{1}\ldots {u}_{v}^{j}\ldots {u}_{v}^{m}\right]}^{T}\), based on computing a measure of variability on a per-feature basis via statistical comparisons of bootstrapped subsets generated from the original feature space. In matrix form, this is represented via the feature variability matrix, \({\bf{P}}=[{{\bf{u}}}_{1}\ldots {{\bf{u}}}_{V}]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times V}\).

We incorporate feature variability into the LASSO formulation, by adding an additional penalty term to the objective function J(θ) in (2). Note that this penalty term is in the quadratic form to ensure that it is convex and a key element of the optimization approach described below.

This represents the objective function for VaRFS, written as:

where β is the regularization parameter, used to differentially weight variability measures (and thus, different sources of variability). Note that R is the symmetric form of the feature variability matrix \({\bf{R}}\triangleq {\bf{P}}{{\bf{P}}}^{T}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{v = 1}^{V}{{\bf{u}}}_{v}{{\bf{u}}}_{v}^{T}\).

Optimization of VaRFS

While f + g is a convex objective function in (3), it is still non-smooth (due to the sparsity term g(θ)) and thus cannot be solved by regular optimization methods such as gradient descent. Rather than computationally expensive and complex alternatives such as the alternating direction method of multipliers58, we utilize proximal algorithms59 as they work under extremely general conditions, are much faster for challenging optimization problems, as well as being scalable and amenable to distributed optimization46. Based on Lemma 1 (see Supplementary Information Section A), in order to minimize f + g in our convex optimization problem, we can replace the non-smooth function f with its upper-bound (denoted \(\bar{f}\)) which results in the following iterative solution algorithm for (3),

where, for the kth iteration,

This in turn is equivalent to

where, \({\bar{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}_{k}={{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k}-\gamma \nabla f({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k})\) and proxγg is the proximal operator of the convex function γg (See Definition 3 in Section A of the Supplementary Information). This base mapping of the proximal algorithm is a standard tool for solving non-smooth optimization problems60. Proof that f in (3) is a Lipschitz continuous gradient function is presented as Lemma 2 in Section B of the Supplementary Information, based on which our problem can be seen to meet the requirements for using general proximal algorithms59. The final Algorithm 1 summarizes the overall approach to solve (6) within VaRFS.

Algorithm 1

Proximal Algorithm for VaRFS

Input: y, X, P, β, λ, K (number of inner-loop iterations), γ (step-size)

initialization : \({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{0}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m}\), R = PPT

1: for k = 1, 2, ⋯ , K do

2: \(f({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k})=\frac{1}{2}{\left\Vert {\bf{y}}-{\bf{X}}{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k}\right\Vert }_{2}^{2}+\beta {{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k}^{T}{\bf{R}}{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k}\)

3: \(g({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k})=\lambda {\left\Vert {{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k}\right\Vert }_{1}\)

4: \({\bar{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}_{k}={{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k}-\gamma \nabla f({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k})\)

5: \({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k+1}={{\rm{prox}}}_{\gamma g}({\bar{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}_{k})\)

6: end for

Output: θ = θk+1

Remark 1

Since in (5), \(\bar{f}({\boldsymbol{\theta }},{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k})\ge f({\boldsymbol{\theta }})\), \(\bar{f}({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k},{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k})=f({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k})\), \(\bar{f}({\boldsymbol{\theta }},{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k})\) is so-called majorization function of f(θ)61. Therefore, our algorithm is a type of majorization-minimization algorithm62.

Convergence analysis of VaRFS

We examine the restrictions on the learning rate parameter γ to assure convergence of the iterations as outlined in (6), in Theorem 1.

Theorem 1

The sequence {θk} in (6), converges to a stationary point of f + g. To guarantee convergence, parameter γ must adhere to

in which,

The proof may be found in Supplementary Information Section B.

Theorem 2

Let Q in (8) is a positive-definite (PD) matrix with singular values sorted as \({\sigma }_{\min }\le \ldots \le {\sigma }_{\max }\). Given that the Algorithm 1 reaches the optimal solution θ* with a generic learning rate γ, the iterations of this algorithm demonstrate a linear convergence rate. Moreover, we have

where \(z(\gamma )=\max \left\{\left\vert 1-\gamma {\sigma }_{\min }\right\vert ,\left\vert 1-\gamma {\sigma }_{\max }\right\vert \right\}\) is the convergence rate.

The proof is provided in Section B of the Supplementary Information.

Figure 9 depicts the convergence rate of the VaRFS regular proximal algorithm for some different learning rate γ. The convergence rate is illustrated based on the condition number (\(\kappa \triangleq \frac{{\sigma }_{\max }}{{\sigma }_{\min }}\)) of the matrix Q. According to (7), as we expected the well-conditioned matrices with κ(Q) > > 1 are faster to converge rather than the ill-conditioned ones with κ(Q) ≈ 1. As can be seen, the higher step size in the convergence interval (\(0 < \gamma \le \frac{1}{{\left\Vert {\bf{Q}}\right\Vert }_{2}}=\frac{1}{{\sigma }_{\max }}\)) correspond to the faster rate.

Acceleration of VaRFS

Following30,63, the basic proximal gradient algorithm can be further accelerated through the use of weighted combinations of current and previous gradient directions via an extrapolation step; thus ensuring each iteration does not require more than one gradient evaluation. This is implemented by incorporating a new sequence, \({\{{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}_{k}\}}_{k = 0}^{\infty }\), which is initialized as η0 = θ0. Recursively updating {ηk} and thus {θk} at each iteration k ∈ {0, 1, …, K} allows for a significantly faster convergence. Algorithm 2 summarizes this accelerated approach to solving (6) within VaRFS.

Algorithm 2

Accelerated Proximal Algorithm for VaRFS

Input: y, X, P, β, λ, K (number of inner-loop iterations), γ (step-size)

initialization : \({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{0}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m}\), η0 = θ0, R = PPT

1: for k = 1, 2, ⋯ , K do

2: \(f({{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}_{k})=\frac{1}{2}{\left\Vert {\bf{y}}-{\bf{X}}{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}_{k}\right\Vert }_{2}^{2}+\beta {{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}_{k}^{T}{\bf{R}}{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}_{k}\)

3: \(g({{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}_{k})=\lambda {\left\Vert {{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}_{k}\right\Vert }_{1}\)

4: ηk = ηk − γ ∇ f(ηk)

5: θk+1 = proxγg(ηk)

6: \({{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}_{k+1}={{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k+1}+w\left({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k+1}-{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{k}\right)\)

7: end for

Output: θ = θk+1

Remark 2

Parameter w must be chosen in specific ways to achieve convergence acceleration. One simple choice takes \(w=\frac{k}{k+3}\)46.

The Section C of the Supplementary Information provides a detailed computational complexity analysis of both Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2, highlighting the convergence rates of \({\mathcal{O}}(1/k)\) and \({\mathcal{O}}(1/{k}^{2})\) for the regular and accelerated versions of VaRFS, respectively.

Data description

C1 (Prostate Cancer MRI) comprised 147 diagnostic T2-weighted (T2w) prostate MRIs from 4 institutions, with the goal of distinguishing benign from malignant lesions in the peripheral zone (discovery: 3 sites, validation: 1 site). More details of this dataset are available in64,65.

C2 (Rectal Cancer MRI, pre-CRT) comprised 197 pre-treatment T2w rectal MRIs from 3 institutions, from patients who later underwent standard-of-care chemoradiation (nCRT) and surgery. Histopathologic tumor regression grade (TRG) assessment of the excised surgical specimen was used to define pathologic complete response (pCR) to nCRT. The goal was to distinguish patients who will achieve pCR (i.e., ypTRG0 or 0% viable tumor cells remaining) from those who will not, based on annotated tumor regions on pre-nCRT MRI. For more dataset details refer to38.

C3 (Rectal Cancer MRI, post-CRT) comprised 119 T2w post-treatment rectal MRI scans from 3 institutions, from patients after they had undergone standard-of-care nCRT but prior to undergoing surgery. Histopathologic tumor stage (ypT) assessment of the excised surgical specimen was used to define the pathologic response to nCRT. The goal was to distinguish patients who achieved tumor regression (i.e., ypT0-2 or tumor that has regressed to within the rectal wall) from those who did not, based on annotated rectal wall regions on post-nCRT MRI. Additional details are in37.

C4 (Crohn’s Disease MRE) comprised 73 T2w bowel MR enterography (MRE) scans from patients who had been endoscopically confirmed with Crohn’s disease. The goal was to distinguish high-risk patients who needed surgery within one year of MRI and initiation of aggressive immunosuppressive therapy, from low-risk patients (stable for up to 5 years in follow-up); using annotated terminal ileum regions on baseline MRIs. This single institutional cohort was harboring large batch effects as a result of adjustments to acquisition parameters including scanner type and magnetic resonance strength. More details of this dataset are available in66.

C5 (Crohn’s Disease CTE) comprised 165 CT enterography (CTE) scans from patients being screened for Crohn’s disease with endoscopic confirmation of disease presence. The goal was to distinguish between healthy and diseased terminal ileum regions within this single institutional cohort harboring significant batch effects67, as well as dose/reconstruction changes.

Radiomic feature extraction

As summarized in Fig. 3, after data acquisition, pre-processing included linear resampling of all scans to an isotropic resolution of 1 × 1 × 1 mm to ensure consistent resolution within each cohort. Additionally, N4ITK bias field correction68 in 3D Slicer was used to correct inhomogeneity artifacts in MRI scans in C1-4. 405 3D radiomic features were then extracted on a voxel-wise basis from all scans. A complete list of all extracted features is provided in Supplementary Data1 in the Supplementary Materials. These features included 20 Histogram, 152 Laws69, 13 Gradient70, 160 Gabor71, and 60 Haralick72 responses. The mean value of each feature was then computed within specified regions-of-interest (ROIs), and feature normalization was applied on a cohort basis to ensure each feature had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Based on the sources of variability present (summarized in Table 5), corresponding variability measures were computed on a per-feature basis for each of the five cohorts C1-5.

VaRFS implementation and sensitivity analysis

VaRFS was implemented as Algorithm 1 (regular) and Algorithm 2 (accelerated), with K = 100 (number of iterations) and \(\gamma =\frac{1}{2{\sigma }_{\max }({\bf{Q}})}\) (mid-point of convergence interval, see Fig. 9). Analysis of convergence differences for J(θ) in (3) between both algorithms was conducted for all five cohorts. To evaluate the effect of the regularization parameters in VaRFS, these were varied as β, λ ∈ {0, 0.1, …, 1} corresponding to variability and sparsity, respectively. These 100 possible β − λ parameter combinations were evaluated for each of C1-5, resulting in a total of 500 possible parameter variations of VaRFS being evaluated. Since each cohort had at least two sources of variability considered, VaRFS was evaluated for considering each individual measure as well as for the combination of multiple variability measures (e.g. P = [u1u2u3] for C5).

Comparative evaluation of common FS approaches

As an alternative strategy, conventional feature selection (FS) approaches including maximum relevance minimum redundancy (mRMR)15, Wilcoxon rank-sum testing (WLCX)16, and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)17 were implemented. All three FS methods were utilized in conjunction with feature variability screening, where radiomic features that did not meet a pre-defined threshold for their feature variability measure were not utilized in downstream analysis. Threshold values for different variability measures were selected based on the literature; specifically radiomic features with IS > 0.2525, CV > 0.565, or ICC < 0.8573 were excluded prior to FS. When considering multiple sources of variability, a sequential elimination process was employed where only those radiomic features were retained that met all relevant thresholds for corresponding variability measures.

Experimental evaluation

All five cohorts were partitioned into discovery and validation sets, as summarized in Table 1. The evaluation of feature sets, selected via each of VaRFS, mRMR, LASSO, and WLCX, was carried out by building a Random Forests classifier (RF) for the binary classification tasks in each cohort. The RF classifier was chosen due to its well-documented proficiency in handling high-dimensional, potentially correlated features, and its robustness against overfitting74. Moreover, RF can estimate the importance of features, which provides additional insight into the data75. In this study, the RF classifier was configured with 50 trees, a maximum depth of 50, and 100 leaf samples.

In all experiments, the RF classifier was first trained and optimized on the discovery cohort using 100 runs of nested 10-fold cross-validation. All model selection and thresholding steps were confined to the training set, within which the average classifier performance was estimated. Based on their formulation, distinct methodologies were employed to determine the top-ranked features and construct a final optimized RF model for hold-out validation when considering statistical FS (mRMR and WLCX) vs optimization-based FS (LASSO and VaRFS). For mRMR and WLCX, the most frequently selected features were identified based on their average rank value across all cross-validation runs. This top-ranked feature set was then utilized to construct a single RF classifier that was evaluated in a holdout fashion on the validation cohort. For LASSO and VaRFS, the best-performing RF model (and a corresponding set of selected features) was identified across all cross-validation runs. This model was then directly evaluated in a holdout fashion on the validation cohort. While these strategies aligned with the operational design of each FS method, an averaging-based approach across all cross-validation runs for each method was additionally implemented to confirm performance trends. Additionally, experimental evaluation was repeated using a Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) classifier76 for evaluating performance differences between VaRFS and comparator methods. All experiments were conducted in MATLAB 9.9 on a 64-bit Windows 10 PC with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7 CPU 930 (3.60 GHz) and 32 GB RAM.

In all cases, the area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AUC) was used as a measure of classifier performance. Statistical comparisons were conducted to assess differences in AUC values between VaRFS and baseline methods. For the training set, a two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test (significance level p < 0.005) was employed using repeated cross-validation results, consistent with prior studies. For the validation set, the DeLong test77 was applied to evaluate statistical differences in ROC curves via VaRFS and baseline methods (since no cross-validation was involved).

A color-coded chord diagram was generated to visualize relationships and connections between top-selected features identified via different FS schemes. Additionally, feature importance was computed via their Shapley (SHAP) values78 rather than feature rank (in mRMR or WLCX) or feature coefficient (in LASSO or VaRFS). The Shapley value is the average marginal contribution of a feature over all possible coalitions79, providing a natural way to compute how much each feature contributes to predictive performance. A parallel coordinate plot (PCP) was constructed80 to analyze trends of the top-ranked VaRFS features in terms of multiple variability measures as well as their discriminability. Finally, a model-level error analysis was conducted to quantify trends in false-positive and false-negative instances across mRMR, WLCX, LASSO, and the two VaRFS variants (single and multiple variability measures), to identify which errors were unique and which were in common between different approaches. This analysis was used to generate an UpSet-style visualization81, enabling direct comparison of error rates as well as distinctiveness in erroneous samples between approaches.

Ethics approval and informed consent

All datasets used in this study comprised de-identified imaging data with appropriate institutional approvals. For the C1 cohort, data and expert annotations of tumor extent were provided under the Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol #02-13-42C, approved by the University Hospitals of Cleveland IRB. For the C2 and C3 cohort, this HIPAA-compliant, retrospective study was approved by IRBs at three institutions: University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (UHCMC, #07-16-40), Cleveland Clinic Foundation (CCF, #18-427), and Case Western Reserve University (STUDY20240128). A waiver for the requirement of informed consent was granted, as only de-identified patient data were utilized. For the C4 and C5 cohort, approval was obtained from the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center IRB under protocol #11-15-24.

Data availability

The imaging datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code for VaRFS, along with documentation and sample data, is openly available at: https://github.com/viswanath-lab/VaRFS.

References

Bera, K., Schalper, K. A., Rimm, D. L., Velcheti, V. & Madabhushi, A. Artificial intelligence in digital pathology—new tools for diagnosis and precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16, 703–715 (2019).

Bera, K., Braman, N., Gupta, A., Velcheti, V. & Madabhushi, A. Predicting cancer outcomes with radiomics and artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 132–146 (2022).

Bankhead, P. Developing image analysis methods for digital pathology. J. Pathol. 257, 391–402 (2022).

Van Timmeren, J. E., Cester, D., Tanadini-Lang, S., Alkadhi, H. & Baessler, B. Radiomics in medical imaging—"how-to” guide and critical reflection. Insights Imaging 11, 91 (2020).

Zhao, B. Understanding sources of variation to improve the reproducibility of radiomics. Front. Oncol. 11, 633176 (2021).

Zwanenburg, A. et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology 295, 328–338 (2020).

Traverso, A., Wee, L., Dekker, A. & Gillies, R. Repeatability and reproducibility of radiomic features: a systematic review. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol.* Biol.* Phys. 102, 1143–1158 (2018).

Mackin, D. et al. Harmonizing the pixel size in retrospective computed tomography radiomics studies. PloS ONE 12, e0178524 (2017).

Berenguer, R. et al. Radiomics of CT features may be nonreproducible and redundant: influence of CT acquisition parameters. Radiology 288, 407–415 (2018).

Hagiwara, A., Fujita, S., Ohno, Y. & Aoki, S. Variability and standardization of quantitative imaging: monoparametric to multiparametric quantification, radiomics, and artificial intelligence. Investig. Radiol. 55, 601–616 (2020).

Eck, B. et al. Prospective evaluation of repeatability and robustness of radiomic descriptors in healthy brain tissue regions in vivo across systematic variations in T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging acquisition parameters. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 54, 1009–1021 (2021).

Steiner, D. F., Chen, P.-H. C. & Mermel, C. H. Closing the translation gap: AI applications in digital pathology. Biochim. et. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 1875, 188452 (2021).

Demircioğlu, A. Reproducibility and interpretability in radiomics: a critical assessment. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 31, 321 (2025).

Keenan, K. E. et al. Challenges in ensuring the generalizability of image quantitation methods for MRI. Med. Phys. 49, 2820–2835 (2022).

Peng, H., Long, F. & Ding, C. Feature selection based on mutual information criteria of max-dependency, max-relevance, and min-redundancy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 27, 1226–1238 (2005).

Wilcoxon, F., Katti, S. & Wilcox, R. A.Critical Values and Probability Levels for the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test and the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, Vol. 1 (American Cyanamid Pearl River (NY), 1963).

Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso: a retrospective. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 73, 273–282 (2011).

Jha, A. et al. Repeatability and reproducibility study of radiomic features on a phantom and human cohort. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–12 (2021).

Verma, R. et al. Stable and discriminatory radiomic features from the tumor and its habitat associated with progression-free survival in glioblastoma: a multi-institutional study. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 43, 1115–1123 (2022).

Edalat-Javid, M. et al. Cardiac SPECT radiomic features repeatability and reproducibility: a multi-scanner phantom study. J. Nuclear Cardiol. 27, 1–15 (2020).

Shi, L. et al. Radiomics for response and outcome assessment for non-small cell lung cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 17, 1533033818782788 (2018).

Huang, Y.-q. et al. Development and validation of a radiomics nomogram for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 2157–2164 (2016).

Khorrami, M. et al. Stable and discriminating radiomic predictor of recurrence in early stage non-small cell lung cancer: multi-site study. Lung Cancer 142, 90–97 (2020).

Pati, S. et al. Reproducibility analysis of multi-institutional paired expert annotations and radiomic features of the Ivy Glioblastoma Atlas Project (Ivy GAP) dataset. Med. Phys. 47, 6039–6052 (2020).

Leo, P. et al. Stable and discriminating features are predictive of cancer presence and Gleason grade in radical prostatectomy specimens: a multi-site study. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–13 (2018).

Sadri, A. R. et al. Sparta: sn integrated stability, discriminability, and sparsity based radiomic feature selection approach. in Proc. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 445–455 (Springer, 2021).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 67, 301–320 (2005).

Simon, N., Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. A sparse-group lasso. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 22, 231–245 (2013).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1 (2010).

Beck, A. & Teboulle, M. A fast iterative shrinkage-thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2, 183–202 (2009).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T., Höfling, H. & Tibshirani, R. Pathwise coordinate optimization. Ann. Appl. Stat. 1, 302–332 (2007).

Daubechies, I., Defrise, M. & De Mol, C. An iterative thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems with a sparsity constraint. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. A J. Issued Courant Inst. Math. Sci. 57, 1413–1457 (2004).

Combettes, P. L. & Pesquet, J.-C. Proximal splitting methods in signal processing. in Fixed-point Algorithms for Inverse Problems in Science and Engineering, 185–212 (SpringerFixed, 2011).

Yao, Y., Deng, B., Xu, W. & Zhang, J. Fast and robust non-rigid registration using accelerated majorization-minimization. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 1–18 (IEEE, 2023).

Chun, I. Y., Huang, Z., Lim, H. & Fessler, J. A. Momentum-net: Fast and convergent iterative neural network for inverse problems. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 4915–4931 (2023).

Gillies, R. J., Kinahan, P. E. & Hricak, H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology 278, 563–577 (2016).

Alvarez-Jimenez, C. et al. Radiomic texture and shape descriptors of the rectal environment on post-chemoradiation T2-weighted MRI are associated with pathologic tumor stage regression in rectal cancers: a retrospective, multi-institution study. Cancers 12, 2027 (2020).

Antunes, J. T. et al. Radiomic features of primary rectal cancers on baseline T2-weighted MRI are associated with pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation: a multisite study. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 52, 1531–1541 (2020).

Alvarez-Jimenez, C. et al. A novel structural modeling magnitude and orientation radiomic descriptor for evaluating response to neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancers via MRI. npj Precis. Oncol. 9, 215 (2025).

Chirra, P. et al. Radiomics to detect inflammation and fibrosis on magnetic resonance enterography in stricturing Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn’s. Colitis 18, 1660–1671 (2024).

Khorrami, M. et al. Distinguishing granulomas from adenocarcinomas by integrating stable and discriminating radiomic features on non-contrast computed tomography scans. Eur. J. Cancer 148, 146–158 (2021).

Midya, A. et al. Population-specific radiomics from biparametric magnetic resonance imaging improves prostate cancer risk stratification in African American men. JU Open 3, e00068 (2025).

Komodakis, N. & Pesquet, J.-C. Playing with duality: an overview of recent primal? Dual approaches for solving large-scale optimization problems. IEEE Signal. Process. Mag. 32, 31–54 (2015).

Samsonov, A. A., Kholmovski, E. G., Parker, D. L. & Johnson, C. R. Pocsense: Pocs-based reconstruction for sensitivity encoded magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. Off. J. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 1397–1406 (2004).

Boyd, S. et al. Distributed optimization and statistical learning via the alternating direction method of multipliers. Found. Trends® Mach. Learn. 3, 1–122 (2011).

Parikh, N. & Boyd, S. Proximal algorithms. Found. Trends Optim. 1, 127–239 (2014).

Atkins, S., Einarsson, G., Clemmensen, L. & Ames, B. Proximal methods for sparse optimal scoring and discriminant analysis. Adv. Data Anal. Classification 16, 1–54 (2022).

Sghaier, M., Chouzenoux, E., Pesquet, J.-C. & Muller, S. A novel task-based reconstruction approach for digital breast tomosynthesis. Med. Image Anal. 77, 102341 (2022).

Chung, H. & Ye, J. C. Score-based diffusion models for accelerated MRI. Med. Image Anal. 80, 102479 (2022).

Da-Ano, R., Visvikis, D. & Hatt, M. Harmonization strategies for multicenter radiomics investigations. Phys. Med. Biol. 65, 24TR02 (2020).

Lee, J. et al. Radiomics feature robustness as measured using an MRI phantom. Sci. Rep. 11, 3973 (2021).

Altman, D. G. & Royston, P. The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. Bmj 332, 1080 (2006).

Decoux, A. et al. Comparative performances of machine learning algorithms in radiomics and impacting factors. Sci. Rep. 13, 14069 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. Ensemble learning-based radiomics with multi-sequence magnetic resonance imaging for benign and malignant soft tissue tumor differentiation. PLoS One 18, e0286417 (2023).

Özdemir, E. Y. & Özyurt, F. Elasticnet-based vision transformers for early detection of parkinson’s disease. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 101, 107198 (2025).

Elad, M.Sparse and Redundant Representations: From Theory to Applications in Signal and Image Processing (Springer, 2010).

Sadeghi, M. & Babaie-Zadeh, M. Iterative sparsification-projection: Fast and robust sparse signal approximation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 64, 5536–5548 (2016).

Hong, M. & Luo, Z.-Q. On the linear convergence of the alternating direction method of multipliers. Math. Program. 162, 165–199 (2017).

Bolte, J., Sabach, S. & Teboulle, M. Proximal alternating linearized minimization for nonconvex and nonsmooth problems. Math. Program. 146, 459–494 (2014).

Bejar, B., Dokmanic, I. & Vidal, R. The fastest L1, oo prox in the west. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 1–1 (IEEE, 2021).

Sun, Y., Babu, P. & Palomar, D. P. Majorization-minimization algorithms in signal processing, communications, and machine learning. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 65, 794–816 (2016).

Sohrab, H. H.Basic Real Analysis (Birkhauser, 2014).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Wainwright, M.Statistical Learning with Sparsity: the Lasso and Generalizations (CHCRC, 2019).

Chirra, P. et al. Empirical evaluation of cross-site reproducibility in radiomic features for characterizing prostate MRI. in Proc. Medical Imaging 2018: Computer-Aided Diagnosis, Vol. 10575, 105750B (ISOP, 2018).

Chirra, P. et al. Multisite evaluation of radiomic feature reproducibility and discriminability for identifying peripheral zone prostate tumors on MRI. J. Med. Imaging 6, 024502 (2019).

Chirra, P. et al. Integrating radiomics with clinicoradiological scoring can predict high-risk patients who need surgery in Crohn’s disease: a pilot study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 29, 349–358 (2022).

Leek, J. T. et al. Tackling the widespread and critical impact of batch effects in high-throughput data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 733–739 (2010).

Tustison, N. J. et al. N4itk: improved n3 bias correction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29, 1310–1320 (2010).

Laws, K. I. Textured Image Segmentation. University of Southern California, Image Processing Institute (1980).

Ma, C., Gao, W., Yang, L. & Liu, Z. An improved Sobel algorithm based on median filter. in Proc. 2nd International Conference on Mechanical and Electronics Engineering, Vol. 1, V1–88 (IEEE, 2010).

Bovik, A. C., Clark, M. & Geisler, W. S. Multichannel texture analysis using localized spatial filters. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 12, 55–73 (1990).

Haralick, R. M. Statistical and structural approaches to texture. Proc. IEEE 67, 786–804 (1979).

Parmar, C. et al. Robust radiomics feature quantification using semiautomatic volumetric segmentation. PloS one 9, e102107 (2014).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Louppe, G., Wehenkel, L., Sutera, A. & Geurts, P. Understanding variable importances in forests of randomized trees. Adv. Neural Inform. Proc. Syst. 26, 431–439 (2013).

Kline, A. et al. Multimodal machine learning in precision health: a scoping review. npj Digit. Med. 5, 171 (2022).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 43, 837–845 (1988).

Pérez, E., Reyes, O. & Ventura, S. Convolutional neural networks for the automatic diagnosis of melanoma: an extensive experimental study. Med. Image Anal. 67, 101858 (2021).

Shapley, L. S. A value for n-person games. Contrib. Theory Games 2, 307–317 (1953).

Edsall, R. M. The parallel coordinate plot in action: design and use for geographic visualization. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 43, 605–619 (2003).

Lex, A., Gehlenborg, N., Strobelt, H., Vuillemot, R. & Pfister, H. Upset: visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 20, 1983–1992 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA280981-01A1, 1U01CA294415-01A1, 1F31CA291057-01A1, 1U01CA248226-01, T32CA094186), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (1R01HL165218-01A1), the National Institute of Nursing Research (1R01NR019585-01A1), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (1R01EB037526-01), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1F31DK130587-01A1), the National Science Foundation (Award # 2320952), the NIH AIM-AHEAD program (1OT2OD032581-01), the VA Merit Review Award from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service (1I01BX006439-01), the CWRU Interdisciplinary Biomedical Imaging Training Program Fellowship (2T32EB007509-16), the DOD Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-21-1-0725, W81XWH-21-1-0345, W81XWH 19-1-0668), the CWRU Translational Fellows Program, the JobsOhio program, the Ohio Third Frontier Technology Validation Fund, and the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation Program in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Case Western Reserve University. This work made use of the High Performance Computing Resource in the Core Facility for Advanced Research Computing at Case Western Reserve University. The authors would like to thank Kenneth Friedman, Joseph Willis, Sharon Stein, Conor P. Delaney, Rajmohan Paspulati, Justin T Brady, Katie Bingmer, Andrei Purysko, David Liska, Matthew Kalady, Maneesh Dave, Namita Gandhi, Mark Baker, B Nicolas Bloch, Mark Rosen, Art Rastinehad, H. Matthew Cohn, and Anamay Sharma for access to anonymized radiograpic imaging scans and pathologic/clinical variables utilized in this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R.S. conceived the study, developed the VaRFS framework, and performed experiments. S.A., P.C., and S.S. assisted with data curation and feature extraction. T.D. contributed to statistical analyses. A.M. provided domain expertise and critical feedback. S.E.V. supervised the study, guided experimental design and interpretation of results, and served as the corresponding author. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.M. has had technology licensed to and is an equity holder in Picture Health, Elucid Bioimaging, and Inspirata Inc. Currently he serves on the advisory board of Picture Health and SimBioSys. He currently consults for Takeda Inc. He also has sponsored research agreements with AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers-Squibb. He is also a member of the Frederick National Laboratory Advisory Committee. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sadri, A.R., Azarianpour, S., Chirra, P. et al. Variability Regularized Feature Selection (VaRFS) for optimal identification of robust and discriminable features from medical imaging. npj Imaging 4, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44303-025-00136-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44303-025-00136-5