Abstract

The reactivated Jungong paleo-landslide (Upper Yellow River) poses dual threats to resident safety and potential disaster chains. This study characterizes the deformation dynamics and spatiotemporal evolution of the Jungong landslide using InSAR and time-series analysis. The results indicate that the landslide is undergoing persistent deformation at rates ranging from −50 to −84 mm/year. The time-series deformation exhibits a linear growth trend, and the area affected by deformation continues to expand. The deformation velocity follows a power-law distribution, indicating a likely increase in future landslide movement rates. The landslide deformation demonstrates distinct seasonal variations, with the magnitude and velocity of deformation during the freeze-thaw cycles period significantly exceeding those observed during the rainy season. Freeze-thaw cycles are the dominant factor driving deformation in this landslide, with rainfall playing a secondary role. This research provides important theoretical insights and valuable references for long-term deformation monitoring of paleo-landslides in high-altitude regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the frequent occurrence of extreme weather and the increased intensity of human engineering activities. The phenomenon of partial or overall resurrection of ancient landslides has been increasing. Resulting in infrastructure damage, casualties, and environmental damage1,2,3,4,5,6. For example, the Pra Bellon landslide in the southern French Alps had undergone 22 resurgent deformations from 1910 to 20117. It seriously threatens the safety of residents’ lives and property. Ancient landslide resurrects in Tibet’s Jiacha Lagang village, the huge resurrection body blocked the channel of the Milin section of the Yarlung Zangbo River and formed a dammed lake8. The ancient Zhama landslide in Batang County, Sichuan Province, has been resurrected locally under the influence of heavy rainfall and the excavation and construction of roads. The revival phenomenon of the landslide occurred in some areas, resulting in the interruption of the national highway G3189. The object of this study, Jungong landslide in Lajia Town, Maqin County, Qinghai Province. It is a giant ancient landslide developed in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River. Due to the long-term erosion of the leading edge of the landslide by the Yellow River and the impact of human engineering activities such as the construction of highways in recent years, the signs of landslide deformation are obvious. The landslide had experienced significant deformation activity in the 1980s, 2011, and 2019. In particular, the leading edge of the northeastern section of this landslide was again unstable in 2019. The road was damaged by 400 m, and 18 households were affected, seriously threatening the safety of life and property of residents in Lajia Town10,11,12,13,14. From the numerous ancient landslide research literature that has been collected. The deformation of ancient landslides has the characteristics of large scale, strong dynamics, multi-stage, multi-region, and large hazards. Therefore, the deformation monitoring of ancient landslides has always been one of the core topics in the field of geological hazard research.

At present, the monitoring methods of ancient landslides mainly include geological analysis, modeling analysis, and remote sensing analysis15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The geological analysis method is based on field surveys and rich expert experience. This method analyzes whether the landslide has the possibility of instability through the topography, landforms, stratum lithology, and other characteristics of the ancient landslide. However, this method is time-consuming and labor-intensive and is not suitable for macroscopic monitoring. The evolving Synthetic Aperture Radar Differential Interferometry (D-InSAR) technology can be used for macroscopic monitoring, which can obtain small deformation information25,26,27,28. This technology has the advantages of all-weather, low cost, wide range, and high accuracy, and is widely used in landslide monitoring29,30,31,32,33,34. Achache uses D-InSAR technology for landslide monitoring in the Alps for the first time35. The monitoring results are consistent with the field measurement results. It is shown that the technique is capable of more accurate remote sensing monitoring of landslides. The SBAS-InSAR technique reduces the effects of spatial incoherence and atmospheric noise and can obtain information about the slow deformation of long-term series36,37,38,39,40,41,42. It is suitable for landslide identification and monitoring in mountainous areas43,44,45,46,47,48. Guo C used SBAS-InSAR technology to obtain the surface deformation information of Xiongba ancient landslide on the west bank of the Jinsha River. It is pointed out that there are two strong deformation regions at the front edge of the landslide, and the erosion of the slope foot aggravates the flood disaster41. The revival of ancient landslides on both sides of the Bailong River in Zhouqu County, Gansu Province, threatens the civil infrastructure downstream. Xu Yuanmao used SBAS-InSAR technology to identify potential landslide hazards and identify potential landslides in Zhouqu County15. The typical landslides were analyzed, and it was believed that rainfall was the inducing factor of ancient landslide deformation. Yan Yiqiu used SBAS-InSAR technology to obtain the surface deformation characteristics and deformation rate of Jiajugu landslide in Danba County, Sichuan Province, and deformation zoning and analyzing deformation mechanism of the ancient landslide. It also shows that the complex geological structure, heavy rainfall, and river erosion of the ancient landslide lead to the acceleration of the creep-slip rate of the landslide and further instability49. Therefore, the use of InSAR technology to monitor the deformation of ancient landslides has certain advantages and applicability. The concealment of geological disasters is high, and there may be a lag in on-site investigation. Therefore, the analysis of the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of landslides is of good significance for similar landslide prevention. Yang Chunyu50 used SBAS-InSAR technology to obtain the surface deformation information of landslides in Zaoling Township, Shanxi Province. According to the time series monitoring results, the standard deviation ellipse algorithm was selected to analyze the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics. The results show that the northwest-southeast deformation gradually intensifies, and the northeast-southwest deformation is moderate. Yang Fang51 used SBAS-InSAR technology to study the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of Ligu landslide. The results show that the deformation center of the landslide spreads in the form of strips to the Jinsha River to the west. Li Zheng52 used Sentinel-1 data and InSAR technology to analyse the characteristics of spatiotemporal deformation and evolution of Muyubao landslide. Compared with GNSS data, it has a high degree of consistency in spatiotemporal evolution.

The object of study in this paper Jungong landslide has also been the subject of a great deal of research done by scholars in the past. For example, in 2020, Cheng Keli conducted field investigations, field seepage experiments, indoor mechanical experiments and numerical simulations of deformation mechanisms to study the deformation mechanisms of the Jungong landslide10,11. It is believed that human engineering activities, ice and snow meltwater and atmospheric rainfall have caused landslide instability and damage. Wang Haifang used InSAR technology to identify the landslide and showed that the landslide was in a creeping-slip state as a whole12. Chen Baolin used SBAS-InSAR technology to study the deformation characteristics and deformation laws of landslide and divided the landslide into region13. It is believed that human engineering activities have a great impact on the stability of landslides, and there is a good response relationship between deformation rate and rainfall. In 2021, Li Chunyang used the transfer coefficient method to carry out stability evaluation, monitoring and early warning of Jungong landslide14. Considering that landslide is stable in their natural state and are unstable and unstable in the event of heavy rainfall and earthquakes. The monitoring and early warning studies show that the landslide is a high early warning, and the prevention and control measures should be followed up in time. The above study analyzed the deformation mechanism, stability evaluation, and deformation characteristics of the Jungong landslide, and used InSAR for deformation monitoring. However, the technical methods used for deformation monitoring are relatively single, and the monitoring period is short. Failure to monitor landslides for deformation over long time series, as well as failure to analyze spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and future deformation trends. Therefore, this paper takes the Jungong landslide as the object of study. D-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR technologies were used to obtain the surface deformation characteristics of the long-term series (2017–2024), and the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and future deformation trends were analyzed. The relationship between precipitation, temperature change, freezing depth and landslide deformation is discussed, and the main controlling factors affecting landslide deformation are found. It provides a certain reference for the deformation monitoring and prevention of the landslide.

Results

D-InSAR technology monitoring results

The D-InSAR technique was used to obtain monthly deformation monitoring results for the study area, and the monthly monitoring results were superimposed to obtain the annual cumulative surface deformation in the study area (Fig. 1). The results show that the landslide continues to creep-slip every year, and the deformation varies from year to year. The maximum annual cumulative deformation of the landslide in the past seven years (2019) was as high as −148.1 mm (Fig. 1e) and the minimum annual cumulative deformation (2017) was −102.5 mm (Fig. 1a). Through the statistics of the annual cumulative deformation pixels in the deformation area, it was found that the deformation was mainly concentrated between −90 and 40 mm, and the uplift phenomenon occurred in some areas of the study area.

a Cumulative deformation in 2017; b Histogram of cumulative deformation in the deformation region in 2017; c Cumulative deformation in 2018; d Histogram of cumulative deformation in the deformation region in 2018; e Cumulative deformation in 2019; f Histogram of cumulative deformation in the deformation region in 2019; g Cumulative deformation in 2020; h Histogram of cumulative deformation in the deformation region in 2020; i Cumulative deformation in 2021; j Histogram of cumulative deformation in the deformation region in 2021; k Cumulative deformation in 2022; l Histogram of cumulative deformation in the deformation region in 2022; m Cumulative deformation in 2023; n Histogram of cumulative deformation in the deformation region in 2023.

The results of the last seven years of monitoring were superimposed and analyzed (Fig. 2). The maximum cumulative settlement was about −601.4 mm, and the maximum cumulative uplift was about 297.2 mm due to the continued deformation of the landslide, which resulted in the uplift of the slope opposite the gully. The maximum cumulative surface subsidence for the last seven years in the study area was counted (Fig. 3), and the subsidence fluctuated. From 2017 to 2019, the cumulative deformation gradually increased every year, and in 2018, due to the heavy rainfall, the cumulative deformation was about −138 mm. In 2019, rainfall induced landslide instability and damage, and the cumulative deformation reached a peak of about −148.1 mm. Based on the information collected, engineering treatments were carried out during the period 2020–2021, and the deformation gradually decreased. However, from 2022 onwards, the treatment effect has gradually weakened, the annual cumulative deformation has gradually increased, and the landslide is still in the continuous creep-slip stage.

SBAS-InSAR technology monitoring results

The results of the average annual deformation rate of the xx landslide from March 2017 to March 2024 were obtained by SBAS-InSAR technology (Fig. 4). The monitoring results indicate that the landslide is in a state of continuous sliding, and the deformation rate varies from year to year, with the maximum deformation rate of −83.7 mm/year (Fig. 4e) and the minimum deformation rate of −50.2 mm/year (Fig. 4i). Due to the dense vegetation cover of the mountain and the angle of satellite photography, incoherence was observed on some of the slopes in the study area. The annual average velocity map was combined with the optical image of the study area to identify and analyze the landslide area. The results show that some areas of the landslide are more deformed, and the deformation area is more concentrated. A histogram of the annual average deformation rate of the surface in the deformation area (Fig. 4) shows that the annual average deformation rate is mainly concentrated in the range of −50–10 mm/year.

a Average annual deformation rate in 2017; b Histogram of average annual deformation rate in deformation region in 2017; c Average annual deformation rate in 2018; d Histogram of average annual deformation rate in deformation region in 2018; e Average annual deformation rate in 2019; f Histogram of average annual deformation rate in deformation region in 2019; g Average annual deformation rate in 2020; h Histogram of average annual deformation rate in deformation region in 2020; i Average annual deformation rate in 2021; j Histogram of average annual deformation rate in deformation region in 2021; k Average annual deformation rate in 2022; l Histogram of average annual deformation rate in deformation region in 2022; m Average annual deformation rate in 2023; n Histogram of average annual deformation rate in deformation region in 2023.

The results of the deformation in the past seven years were overlaid (Fig. 5), and the results showed that most areas of the landslide were continuously deformed. The maximum cumulative settlement in the last 7 years amounted to 383.3 mm, while the maximum cumulative uplift was 327.1 mm due to the continuous sliding of the landslide, which resulted in the uplift of the slope opposite to the gully. The statistical results of the maximum cumulative surface subsidence in the study area in the last 7 years (Fig. 6) show that the landslide deformation is fluctuating, which is consistent with the monitoring results of the D-InSAR technology.

Discussion

InSAR Technology Reliability Analysis. To test the reliability of the monitoring results of the same data source under different technical methods. Reliability analysis was performed using the coherence coefficients of the interferometric pairs resulting from the processing of the 2017 image data. The coherence coefficient of the interference pair is an important index to evaluate the accuracy of the monitoring results53. The coherence coefficient of the interference pair treated by D-InSAR technology is significantly higher than that of SBAS-InSAR (Fig. 7). This is because the D-InSAR technique monitors deformation over a short period of time, and therefore, its coherence factor is less affected by factors such as time variation. The monitoring period of SBAS-InSAR technology is long, and the coherence coefficient may be affected by factors such as surface changes over time span. Histogram of statistical coherence coefficient (Fig. 8). The coherence coefficients of the D-InSAR technique show an approximate normal distribution with a peak value centered at 0.45 and low volatility. In contrast, the SBAS-InSAR technique coherence coefficient clearly shows two high and low peaks. The high coherence area (coherence coefficient greater than 0.8)54 is concentrated in the residential area at the foot of the slope (Fig. 7a). This is because no significant deformation has occurred in the region and the surface is relatively stable and exhibits high coherence. Areas of low coherence are concentrated in areas of landslide deformation. This is because the landslide is undergoing continuous deformation, and the coherence is affected by surface changes, which then results in lower coherence. The coherence coefficients of both InSAR techniques are greater than 0.21 (Table 1), and the mean values are greater than 0.49, both of which satisfy the monitoring requirements55. Both techniques can obtain effective deformation monitoring information, and the monitoring results have high reliability. However, the monitoring results of SBAS-InSAR technology have more obvious discrimination (double peaks) and can effectively extract the deformed and non-deformed regions.

InSAR technology monitoring accuracy analysis. To further verify the accuracy of InSAR monitoring, the measured data of two field monitoring points (A01 and A02) were used to compare and analyze the InSAR monitoring results. The SBAS-InSAR technology monitoring data is closer to the field monitoring values when the difference between the data and the field monitoring data is smaller (Tables 2 and 3). The InSAR monitoring data curves are morphologically consistent with the measured data curves (Fig. 9), and both respond to some extent to the step characteristics of landslide deformation. However, the root-mean-square error and average absolute error between the monitoring data curve and the measured data curve of the SBAS-InSAR technique are lower than those of the D-InSAR technique (Table 4), and the accuracy advantage is more obvious. By comparing the correlations, the linear trend of SBAS-InSAR technology is more consistent with that of field monitoring. In summary, the SBAS-InSAR technique is superior to the D-InSAR technique in both its monitoring accuracy and curve correlation.

InSAR technology applicability analysis. The analysis of reliability and monitoring accuracy shows that the SBAS-InSAR technique is more suitable for the study of long time series deformation monitoring of ancient landslides in this paper. Therefore, the subsequent discussion is dominated by the results of the SBAS-InSAR technical monitoring.

Temporal variation of landslide surface deformation. To investigate the temporal variation rule of landslide surface deformation, and to analyze the variation characteristics of landslide surface deformation with time more intuitively. Feature points were selected for analysis in the front, middle, and back of the slide in the landslide area, and the location distribution of each feature point is shown in Fig. 10.

The temporal deformation of each feature point is shown in Fig. 11. There are obvious differences in the deformation of the slide in different regions, but all of them have the deformation of the feature points in the front of the slide larger than that in the back of the slide, showing a traction deformation damage pattern. The magnitude of the curve change shows that the surface deformation in the east and west regions of the landslide has a significantly increasing trend from 2022 onwards.

The spatial variation of landslide surface deformation. From the time series variation of the total area of landslide deformation area (Fig. 12), the maximum area of deformation area is about 2.1 km2. Using 2017 as the baseline, the area of deformation regions with deformations greater than 50 mm increased steeply in 2018, with an increment of ~0.97 km2. The area of deformation regions with deformations greater than 100 mm in 2019 is significantly larger, with an increment of ~0.47 km2. The incremental area of deformation regions with deformations greater than 150 mm in 2020 is ~0.23 km2. The area of deformation regions with deformations greater than 300 mm increases to 0.12 km2 in 2023. It can be seen from the above that the deformation volume of the landslide deformation region is continuously increasing and the area of the deformation region is also continuously expanding.

Landslide deformation motion characteristics. To understand the landslide deformation motion characteristics, the deformation velocity pixels in the deformation area were counted. The daily deformation velocity and velocity probability distribution of landslide were calculated56,57. The speed can be divided into four categories, specifically small speed (<0.2 mm/d), medium speed (0.2–0.4 mm/d), high speed (0.4–0.6 mm/d) and extreme speed (>0.6 mm/d)58. Although the velocity distribution of landslides varies from year to year, they all show good power-law dependence and conform to the power-law distribution (Fig. 13). Most of the landslide deformation velocity distributions show power-law characteristics. In recent years, landslide deformation velocities have been distributed mainly in the small velocity range. Medium velocities were reached only in some like elements in 2018 and 2019, indicating that the landslide deformation motion is overall slower and, in a creeping-slip state. Although larger deformation velocities occur less frequently, they can still have a large effect on landslide deformation motions. Therefore, focused monitoring of extreme deformation velocities of landslides is also extremely important for predicting the future spatiotemporal characteristics of landslides.

a Velocity probability distribution in 2017; b Velocity probability distribution in 2018; c Velocity probability distribution in 2019; d Velocity probability distribution in 2020; e Velocity probability distribution in 2021; f Velocity probability distribution in 2022; g Velocity probability distribution in 2023.

Landslide deformation trend analysis. The R/S method is a statistical method used to analyze the long-term dependence and fractal characteristics of a long time series. It was proposed by H.E. Hurst in the 1950s when he studied water level fluctuations in the Nile River59. The core of the method is the calculation of the Hurst index, which is used to quantitatively and statistically analyze the persistence or opposite persistence of long time series. When H = 0.5, the long time series exhibit stochasticity, the closer the H value is to 1, the stronger the correlation, and the closer the H value is to 0, the stronger the inverse persistence60.

Using the R/S method to analyze landslides, landslide deformation has a long-term correlation, which can be used to predict the future development trend of landslide deformation. In this study, \(\log \,R/S\) and \(\log (t)\) showed a good linear fit (Fig. 14). The R2 were greater than 0.9, the H-index was greater than 0.5, and the cumulative landslide deformation was positively correlated in the time series. The trend of future development of the landslide is consistent with past trends, and the landslide will continue to be in creep-slip. And the H-indexes are all greater than 0.7, indicating that the future deformation rate of the landslide may increase.

Since the landslide deformation area is large, the feature points of each area are studied separately to illustrate the future deformation trend of each landslide area. For feature point M1 (Fig. 14a), the H-index is 0.86, which has a long-term positive correlation, indicating that the future deformation trend of the area where the feature point is located is consistent with the present. However, the H-index is slightly smaller compared to the other feature points. The H-index of the feature point M2 is 0.88 (Fig. 14b), which has a long-term positive correlation. This area is at the “S” bay of the national highway G227, which is affected by external factors all year round, resulting in the H-index being slightly smaller than the indices of other areas. However, future deformation trends in the region remain consistent with the present. The H-index of the feature point M3 is 0.97 (Fig. 14c), which indicates that the future displacement changes in this area of the landslide are similarly to the current motion trend and may even show deformation acceleration. The H-index of feature point M4 is 0.98 (Fig. 14d), which has a long-term high positive correlation, and the future development trend is highly consistent with the present. The region may also experience an increase in deformation rate due to the large H-index. The above analysis shows that the internal motion of the landslide is not uniform. The movement deformation trend of the regions where the M1 and M2 feature points are more consistent, and the movement deformation trends of the regions where the M3 and M4 feature points are located are similar. And the long-term deformation trend of the landslide has a certain regularity. It can be monitored for a long period of time to calculate the H-index and thus analyze the long-term deformation trend of the landslide.

Relationship between precipitation and landslide deformation. The feature points were selected in the landslide deformation area, and the correlation between the landslide temporal deformation and precipitation was further analyzed. The results show that landslide deformation has a good response relationship (positive correlation) with precipitation and undergoes accelerated deformation to varying degrees during the rainy season each year (Fig. 15). The acceleration phenomenon was the most significant in 2018, and there were no obvious signs of acceleration in 2021 due to engineering management. In 2018, the deformation of feature points had a good response relationship with rainfall (Fig. 16), and the deformation increased with the increase of rainfall. With the arrival of the rainy season, the slope deformation enters an accelerated period from June to October, during which the precipitation gradually reaches its peak. With the increasing rainfall, the slope surface fissures accelerate the liquid water infiltration, the soil body softens, the self-weight of the slope body increases continuously, which reduces the strength of the soil body, and the shear resistance of the slope body decreases61,62,63,64. As a result, there is a significant acceleration of the deformation of the slope, while the landslide gradually returns to stability after the rainy season.

To further analyze the relationship between precipitation and deformation more visually, rainy season precipitation, annual precipitation and deformation were plotted (Fig. 17). Precipitation is positively correlated with deformation, and the deformation increases with the increase of precipitation in the year. Heavy rainfall occurred in 2018, with a rainfall of up to 691.5 mm, which accelerated the deformation of the landslide in that year, with a cumulative annual deformation of the landslide of up to 64.4 mm. In 2019, heavy rainfall induced instability damage, and the annual cumulative deformation reached a peak of about 68.4 mm. After 2021, the rainfall caused the landslide to gradually return to an accelerated creep-slip state. Combined with Figs. 21 and 23, the rainy season precipitation is also positively correlated with the rainy season deformation, and the rainy season deformation has the same trend of deformation as the annual deformation, and both are positively correlated with precipitation. The results show that there is a good positive correlation between precipitation and landslide deformation.

Relationship between temperature (seasonal freezing and thawing) and landslide deformation. The results of the field survey and available geologic information indicate that the study area is a seasonal permafrost area. The seasonal freezing and thawing action in the permafrost region is also an important factor leading to landslides, and the higher the elevation, the stronger the freezing and thawing action65. To analyze the effect of freeze-thaw action on landslide deformation. Focuses on analyzing the relationship be-tween temperature changes and deformation of feature points in the study area. The results show accelerated deformation of the landslide by freeze-thaw action (Fig. 18). Temperatures in the study area were above 0 °C from June to September, with minimum temperatures below 0 °C in all other months. The winter season is long, but the maximum winter temperatures are above 0 °C, providing a better base for the melting of snow and ice into water to infiltrate the soil. With the alternation of seasons and the recurrence of freeze-thaw action, the landslide is undergoing accelerated creep-slip from December to April each year. And in November the landslide was in a steady state with no significant accelerated creep-slip. There is a clear seasonal variation characterized. November is the alternate season between fall and winter, with average temperatures around 0 °C. Precipitation is low during the season and there is no source of water infiltration into the soil. Thus, the landslide was in stable condition during that period. Although overall precipitation is low in winter, localized rainfall or snowmelt can have an impact on slope stability. Especially when the snow melts, infiltration increases the water content of the geotechnical body and reduces its shear strength, thus contributing to creep-slip of the landslide. M1 was more significantly affected by seasonal freeze-thaw action in 2019, with a freeze-thaw seasonal variance of about 27.6 mm in that year. The accelerated deformation of M3 was most significant in the freeze-thaw season of 2020, when the deformation amount was about 43.4 mm and the deformation rate was as high as 86.8 mm/year. All the above indicate that the landslide undergoes accelerated deformation each year by seasonal freeze-thaw action.

Relationship between the depth of freezing and landslide deformation. To further analyze the relationship between seasonal freeze-thaw and landslide deformation. Calculation using Nelson’s method gives the permafrost distribution index. The monthly maximum and minimum air temperatures in the study area were used to calculate the ground temperature based on the heat transfer equation of the soil. Combined with Stefan’s formula to estimate the depth of freezing66,67. There is a positive correlation between freezing depth and freeze-thaw season deformation (Fig. 19). The greater the freezing depth, the more ice crystals are formed during the freezing process. As the temperature rises, the ice crystals gradually melt, thus causing the freeze-thaw seasonal deformation to increase. The freeze-thaw season deformation was most significant in 2019, when the depth of freezing was ~1.092 m. The maximum freeze-thaw seasonal deformation for the year was about 44.6 mm due to the greater depth of freezing and more ice crystals in the soil. The landslide accelerated deformation during this period, which provided key conditions for the instability and damage of the landslide in September 2019.

Seasonal deformation characteristics during the rainy season. To explore the seasonal deformation characteristics of the rainy season. The deformation velocity data of four feature points M1, M2, M3, and M4, were selected for non-rainy and rainy seasons. Compare and contrast the relative changes in the ratio of landslide deformation velocities in the non-rainy and rainy seasons. The velocity ratio is the non-rainy season velocity or rainy season velocity divided by its average velocity. A detailed analysis of the deformation characteristics of landslides in different seasons is carried out by means of their velocity ratios.

Feature point rainy season deformation velocity is mostly higher than its average velocity (velocity ratios >1). The deformation velocities were all lower than their average velocities in the non-rainy season (velocity ratio <1). The annual rainy season velocity ratio was significantly greater than that of the non-rainy season (Fig. 20). The landslide undergoes accelerated deformation to varying degrees during the rainy season, and it is in a normal creep-slip condition during the non-rainy season68,69. It has obvious seasonal deformation characteristics in the rainy season. The ratio of rainfall deformation velocities at the feature point increases gradually from 2017 to 2019. The instability damage velocity ratios peaked in 2019, and the feature point deformation velocity ratios were all greater than 1 in that year. The treatment works were carried out in 2021, which effectively curbed the deformation of the landslide, and the deformation velocity ratios of the feature points were all less than 1 and tended to be 0 in that year. The feature point deformation velocity ratios gradually increased after 2021 and are all progressively >1. In contrast, the non-rainy season velocity ratio was less than 1 in each year of the monitoring cycle. The synthesis indicates that the landslide is characterized by significant seasonal deformation during the rainy season. Prolonged rainfall can lead to accelerated landslide creep-slip and even destabilization damage, while non-rainy season, landslides creep-slip slowly.

Seasonal deformation characteristics during the freeze-thaw season. The feature point freeze-thaw seasonal deformation velocities are all essentially higher than their average velocities (velocity ratios >1). The deformation velocities during the non-freeze-thaw season were all lower than their average velocities (velocity ratios <1). The velocity ratio for each year’s freeze-thaw season was greater than the velocity ratio for that year’s non-freeze-thaw season (Fig. 21). The landslide undergoes significant accelerated deformation during the freeze-thaw season and is in a normal creep-slip condition during the non-freeze-thaw season. In 2019, the velocity ratio reached a peak, and the deformation velocity ratio of the feature points was greater than 1 in that year, and the deformation velocity ratio of some feature points was as high as 2. And the velocity ratios are all less than 1 in the non-freeze-thaw season. The seasonal deformation characteristics of the freezing season were the most significant. The deformation velocity ratio of landslides is larger during the freeze-thaw season and smaller during the non-freeze-thaw season. Freeze-thaw action has a significant effect on landslide deformation. Long-term freeze-thaw action will lead to landslide acceleration, creep-slip, and even instability and failure. Instead, non-freeze-thaw season landslides creep and slide slowly. It has obvious seasonal deformation characteristics in freeze-thaw season.

The main influencing factors of landslide deformation. Based on the above analysis, the deformation of landslides is mainly affected by rainfall and freeze-thaw action. There are obvious seasonal variation characteristics. Therefore, the main influencing factors of landslide deformation are explained by the deformation and deformation velocity ratio of the rainy season and freeze-thaw season. The results show that both the freeze-thaw season deformation and deformation velocity ratio are significantly larger than the rainy season of the year (Figs. 22 and 23). Thus, freezing and thawing have a stronger effect on the landslide. In summary, the Jungong landslide is mainly affected by freeze-thaw and rainfall factors. However, it is more significantly affected by freeze-thaw action each year. Therefore, freeze-thaw has a great influence on landslide deformation, and the rainfall factor had the next highest impact.

In this paper, D-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR techniques are used to obtain surface deformation information. Comparative analysis of the reliability, monitoring accuracy, and applicability of the monitoring results of the two techniques. Based on the long-term time series monitoring results, the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and future deformation trend of the Jungong landslide were analyzed. To explore the relationship between rainfall, temperature change, freezing depth, and landslide deformation, and the main factors affecting landslide deformation. The following main conclusions were reached.

First, for long-term time series deformation monitoring of giant ancient landslides. Both surface deformation monitoring methods, D-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR techniques, have high reliability and accuracy. Comparison with the Jungong landslide site monitoring data shows that the SBAS-InSAR technology has high monitoring accuracy. In general, SBAS-InSAR technology has high applicability.

Second, by analyzing the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics, the Jungong landslide is creeping-slip continuously. The temporal deformation increased linearly, and the maximum cumulative deformation is as high as 383.8 mm. And the landslide is mainly damaged by traction. The area of the deformation region is constantly expanding, and the maximum area is about 2.1 km2. The deformation velocity distribution conforms to a power law distribution. The speed of landslide deformation is basically slow, and the landslide deformation motion is a creep-slip state. The R/S analysis method shows that the cumulative deformation time series of the landslide is positively correlated, and the deformation velocity of the landslide may increase in the future.

Third, both precipitation and temperature changes (seasonal freeze-thaw) showed a good response relationship with landslide deformation, and there was a positive correlation between freezing depth and freeze-thaw seasonal deformation. The Jungong landslide deformation has obvious seasonal deformation characteristics. Both the freeze-thaw season deformation and deformation velocity ratio were significantly larger than those of the rainy season of the year. Therefore, freeze-thaw has a great influence on landslide deformation, and the rainfall factor had the next highest impact.

Methods

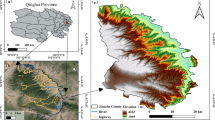

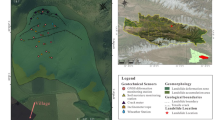

Study area

The landslide is located in Quwajiasa Village, Lajia Town, Maqin County, Guoluo Prefecture, Qinghai Province (Fig. 24). The study area has a typical plateau continental climate, which is affected by the intrusion of humid airflow from the southwest and southeast and has the characteristics of a semi-humid alpine climate. The average precipitation over the years from 420 to 560 mm, and the precipitation is unevenly distributed within the year. It is mainly concentrated from June to September, accounting for more than 80% of the year’s precipitation. The annual average temperature in the study area is −0.1 °C. The study area was warmer from May to September, with an average temperature of 7.9 °C and an extreme maximum temperature of 26.3 °C. And the lowest temperatures are found from October to May, with an average of −4.4 °C and an extreme low of −33.7 °C. The study area is a typical plateau and mountain landform, and the outcropping strata are mainly Cenozoic Neogene and Quaternary strata. Among them, the lithology of the Neogene strata is red-orange-red silty mudstone with gypsum interbedded. The Quaternary strata are Upper Pleistocene and Holocene alluvial deposits.

The landslide area is located on the right bank slope of the Yellow River. The elevation is 3040–3340 m, the relative elevation difference is 185–300 m, and the slope is 25°–36°. The width of the landslide is about 2500 m, the length is 700–900 m, the thickness is about 30–100 m, the square volume is about 1.67 × 108m3, and the main sliding direction is 298°–307°. The lithology of the sliding body is mainly Quaternary silty clay with breccia, block gravel, and pebble gravel (Fig. 25). The sliding bed is a Neogene silty mudstone. The area where the landslide is located is a strong downcutting erosion area of the Yellow River. The concave bank slope is in direct contact with the riverbed and has been subjected to strong erosion cutting for a long time, forming steep slopes and cliffs ranging from tens of meters to hundreds of meters high, which provide favorable conditions for the formation of landslides. In addition, human engineering activities such as the construction of National Highway G227 and the excavation of the foot of the slope for residential buildings have also had an impact on the landslide. The landslide had experienced significant deformation activity in the 1980s, 2011, and 2019. In 2020, the landslide treatment project will be implemented. Use earthwork to counterpress the slope foot. A pile plate wall is provided at the leading edge. Set up reasonable drainage measures. The backfilled area has been planted with grass and trees.

Data source

The InSAR data are based on C-band Sentinel-1A TOPSAR imagery launched by ESA. A total of 206 images of down-orbit single polarization (VV) and interferometric wide-range acquisition (IW) were collected from March 2017 to March 2024. The spatial resolution is 2.3 × 14.1 m. The image coverage (Fig. 26) ranges from 99.134827° to 101.866547°E and 33.445084° to 35.463829°N. The basic information of the SAR data is shown in Table 5.

External data includes the DORIS Precision Orbit Data File (AUX_POEORB) provided by the European Space Agency and the 1 arc second (~30 m resolution) Space Shuttle Radar Terrain Mission (SRTM) DEM data provided by the National Space Administration (NASA). GACOS uses the Tropospheric Iterative Decomposition (ITD) model to separate the stratification and turbulence signals from the total tropospheric delay and generate a total zenith delay map with high spatial resolution. It is used to calibrate InSAR measurements and is available free of charge. Rainfall and temperature data are for the period of March 2017–March 2024 from the meteorological station in Maqin County.

Data processing methods

D-InSAR technology is an extension of InSAR technology, which was first proposed by Gabriel26. Through SAR images from different periods in the same area and combined with external DEM data to eliminate errors due to terrain phasing. Interference processing is performed to obtain information on surface deformation in the study area. D-InSAR technology can be divided into the two-track method, three-track method, and four-track method. Among them, the two-track method is simple and convenient to operate, and it is the most commonly used processing method. Therefore, the two-track approach was adopted in this study. The main principles of this method are as follows:

In Eq. (1), \({\phi }_{{\rm{disp}}}\) is the surface deformation phase, \({\phi }_{{\rm{flat}}}\) is the flat earth phase, \({\phi }_{{\rm{land}}}\) is the topographic phase, \({\phi }_{{\rm{wrap}}}\) is the winding phase, \({\phi }_{{\rm{noise}}}\) is the total noise phase, \({\phi }_{{\rm{air}}}\) is the atmospheric delay phase.

In order to obtain the deformation phase \({\phi }_{{\rm{disp}}}\), the other phases must be removed and the noise phase \({\phi }_{{\rm{noise}}}\) must be minimized. The \({\phi }_{{\rm{wrap}}}\), \({\phi }_{{\rm{noise}}}\), and \({\phi }_{{\rm{air}}}\) in Eq. (1) can be removed by filtering process, phase untangling, and selecting GCP points. \({\phi }_{{\rm{flat}}}\) and \({\phi }_{{\rm{land}}}\) can be eliminated by importing an external DEM, Eq. (2) is:

In Eq. (3), \(h\) is the elevation of the ground point. \(\alpha\) is the angle of incidence of the radar. \(\lambda\) is the wavelength of the radar wave. \(r\) is the distance from mine to the ground point. \({B}_{\perp }\) is the projection of the baseline in the direction perpendicular to the slope.

Finally, the other phase errors in Eq. (1) are removed:

In Eq. (4), \(\varDelta r\) is the displacement from the ground point to the target point in the direction of the radar line of sight in the time interval between the two SAR images. \(\lambda\) is the radar signal wavelength.

The Goldstein filter method is used to reduce the phase and atmospheric noise and improve the coherence of the interferogram70,71,72. The minimum cost workflow algorithm is used for phase unwrapping73,74. The interference phase is unwrapped into a true value to solve the 2π ambiguity problem. The threshold of the unwrapped coherence coefficient is set to 0.15. The specific process is shown in Fig. 27.

The SBAS-InSAR technique composes interference pairs by setting temporal and spatial baseline thresholds36. Differential interferometry is performed on the interferometric pairs to form multiple phase unwrapping datasets. The singular value decomposition method is used to obtain the surface temporal deformation information. The principle is as follows:

Suppose a dataset consisting of \(N\) SAR images are obtained. Arrange all the images in the dataset in chronological order \(({t}_{1},{t}_{2},\mathrm{..}.,{t}_{N})\). Generation of \(M\) interferograms based on spatiotemporal interference baseline threshold conditions. Then the range of \(M\) is:

By interfering with the SAR images acquired at time a and b, arbitrary interferograms can \(j(1 < j < N)\) be obtained. Then the phases of the interferogram \(j\) at the azimuth coordinates \(x\) and the distance coordinates \(r\) can be expressed as follows:

In Eq. (6), \(\lambda\) is the wavelength of the radar signal. \({\varphi }_{j}({t}_{a},x,r)\) and \({\varphi }_{j}({t}_{b},x,r)\) are the position values of the SAR images at time \({t}_{a}\) and \({t}_{b}\). \(d({t}_{a},x,r)\) and \(d({t}_{b},x,r)\) are the cumulative amount of deformation at the \({t}_{a}\) and \({t}_{b}\) moments relative to the initial moment \({t}_{0}\) in the direction of incidence of the radar antenna.

The phase value of a certain time period can be expressed by the product of time \({t}_{k}\) and the meaning of the phase velocity \({v}_{j}\) in that time span. Then the phase value of Eq. (6) can be expressed as follows:

Then the phase value of the j-th interferogram can also be expressed as the integral of \({v}_{j}\) on \([{t}_{a},{t}_{b}]\). It can be expressed as follows:

In Eq. (9), \(A\) is the matrix of \(M\times N\). All the time-series SAR data in the SBAS process form multiple small baseline subsets. Assuming a small baseline subset is formed. If \(L\) small baseline subsets are formed, the rank of \(A\) is\(N-L+1\). The system of equations has infinitely many solutions. In this case, the SVD method is needed to solve the minimum norm meaning solution. After solving for \(v\), the cumulative morphology for each time period can be calculated by simply calculating the integral of \(v\) over each time period.

Due to the long time span of this study, it will cause problems such as spatiotemporal incoherence. Therefore, the monitoring analysis was chosen on an annual basis. The annual monitoring results are superimposed to obtain cumulative deformation. To improve the accuracy of the monitoring results, the maximum time baseline threshold was set to 120 days, and the maximum spatial baseline threshold was set to 5%. The spatiotemporal baselines for 2019 are shown in Fig. 28. In this paper, GACOS data are used to remove the influence of atmospheric noise, so that the interferogram phase is more accurate and reliable75,76,77. In addition, the 30 m SRTM DEM is used to remove the influence of topographic phase and improve the accuracy of interference processing. The Goldstein filter method was used for filtering. At the same time, the clarity of the interference fringes is improved, and the incoherence error caused by the temporal or spatial baseline is reduced. The study area is located in a mountainous area with poor coherence. Select the minimum cost workflow method for unwrapping, and the coherence threshold for unwrapping is set to 0.15. The specific process is shown in Fig. 29.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Code availability

The code for this study is available upon reasonable request from the authors.

References

Dai, Z. et al. A giant historical landslide on the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 2055–2068 (2019).

Rosone, M., Ziccarelli, M., Ferrari, A. & Farulla, C. A. On the reactivation of a large landslide induced by rainfall in highly fissured clays. Eng. Geol. 235, 20–38 (2018).

Guo, C. B. et al. Reactivation of giant Jiangdingya ancient landslide in Zhouqu County, Gansu Province, China. Landslides 17, 179–190 (2020).

Shang, H. et al. Spatial prediction of landslide susceptibility using logistic regression (LR), functional trees (FTs), and random subspace functional trees (RSFTs) for Pengyang County, China. Remote Sens. 15, 4952 (2023).

Li, L., Xu, C., Xu, X., Zhang, Z. & Cheng, J. Inventory and distribution characteristics of large-scale landslides in Baoji City, Shaanxi Province, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 11, 10 (2022).

Cui, Y. L., Deng, J. H. & Xu, C. Volume estimation and stage division of the Mahu landslide in Sichuan Province, China. Nat. Hazards 93, 941–955 (2018).

Lopez Saez, J., Corona, C., Stoffel, M., Schoeneich, P. & Berger, F. Probability maps of landslide reactivation derived from tree-ring records: Pra Bellon landslide, southern French Alps. Geomorphology 138, 189–202 (2012).

Wu, R. A., Zhang, Y. S., Guo, C. B., Yang, Z. H. & Liu, X. Y. Characteristics and formation mechanisms of the Lagangcun Giant Ancient landslide in Jiacha, Tibet. Acta Geol. Sin. 92, 1324–1334 (2018).

Zhang, Y. Y. et al. Development characteristics and reactivation trend of Zhama ancient landslide in Batang, Sichuan. Geol. Bull. China 40, 2002–2014 (2021).

Cheng, K. L., Bai, H. L. & Fang, H. Y. Research on deformation and damage characteristics and mechanism of Jungong landslide in Qinghai Province. Gansu Water Resour. Hydropower Technol. 57, 45–51+65 (2021).

Cheng, K. L. Study on deformation failure mechanism and evolution trend of Jungong Landslide in Lajia Town, Qinghai Province. Chengdu, China: Chengdu University of Technology (2021).

Wang, H. F. Research on landslide monitoring by combining PS-InSAR andSBAS-InSAR technology: taking Maqin country of Qinghai province as an example. Chengdu, China: Chengdu University of Technology (2021).

Chen, B. L. et al. Deformation analysis of Jungong ancient landslide based on SBAS-InSAR technology in the yellow river mainstream. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 49, 1407–1421 (2024).

Li, C. Y., Jia, S. A. & Duan, S. R. Study on stability evaluation and follow-up early warning of giant old landslide in the deep cut area of the Yellow River. J. Northwest Norm. Univ.59, 119–125 (2023).

Xu, Y. M., Wu, Z. & Liu, J. Early identification of potential landslide hazards and precipitation correlation analysis in Zhouqu County Based on SBAS–InSAR technology. Adv. Eng. Sci. 55, 257–271 (2023).

Qi, W., Yang, W., He, X. & Xu, C. Detecting Chamoli landslide precursors in the southern Himalayas using remote sensing data. Landslides 18, 3449–3456 (2021).

Ma, S., Xu, C., Shao, X., Xu, X. & Liu, A. A large old landslide in Sichuan Province, China: surface displacement monitoring and potential instability assessment. Remote Sens. 13, 2552 (2021).

Ma, S. Y. et al. UAV survey and numerical modeling of loess landslides: an example from Zaoling, southern Shanxi Province, China. Nat. Hazards 104, 1125–1140 (2020).

Xu, C. et al. An anthropogenic landslide dammed the Songmai River, a tributary of the Jinsha River in Southwestern China. Nat. Hazards 99, 599–608 (2019).

Ma, S. Y. & Xu, C. Assessment of co-seismic landslide hazard using the Newmark model and statistical analyses: a case study of the 2013 Lushan, China, Mw6.6 earthquake. Nat. Hazards 96, 389–412 (2019).

Xu, C. et al. Landslides triggered by the 2016 Mj 7.3 Kumamoto, Japan, earthquake. Landslides 15, 551–564 (2018).

Xu, C. & Xu, X. W. Statistical analysis of landslides caused by the Mw 6.9 Yushu, China, earthquake of April 14, 2010. Nat. Hazards 72, 871–893 (2014).

Chong, X. et al. Application of an incomplete landslide inventory, logistic regression model and its validation for landslide susceptibility mapping related to the May 12, 2008 Wenchuan earthquake of China. Nat. Hazards 68, 883–900 (2013).

Hernandez, J. A. C., Lazecky, M., Sebesta, J. & Bakon, M. Relation between surface dynamics and remote sensor InSAR results over the Metropolitan Area of San Salvador. Nat. Hazards 103, 3661–3682 (2020).

Massonnet, D. et al. The displacement field of the Landers earthquake mapped by radar interferometry. Nature 364, 138–142 (1993).

Gabriel, A. K., Goldstein, R. M. & Zebker, H. A. Mapping small elevation changes over large areas: differential radar interferometry. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 94, 9183–9191 (1989).

Ma, J. Q. et al. Decision-making fusion of InSAR technology and offset tracking to study the deformation of large gradients in mining areas-Xuemiaotan mine as an example. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 962362 (2022).

Roy, P., Martha, T. R., Kumar, K. V. & Chauhan, P. Coseismic deformation and source characterisation of the 21 June 2022 Afghanistan earthquake using dual-pass DInSAR. Nat. Hazard118, 843–857 (2023).

Fruneau, B., Achache, J. & Delacourt, C. Observation and modelling of the Saint-tienne-de-Tinée landslide using SAR interferometry-sciencedirect. Tectonophysics 265, 181–190 (1996).

Herrera, G. et al. Analysis with C- and X-band satellite SAR data of the Portalet landslide area. Landslides 8, 195–206 (2011).

Schlögel, R., Doubre, C., Malet, J.-P. & Masson, F. Landslide deformation monitoring with ALOS/PALSAR imagery: a D-InSAR geomorphological interpretation method. Geomorphology 231, 314–330 (2015).

Xie, M. W., Huang, J. X., Wang, L. W., Huang, J. H. & Wang, Z. F. Early landslide detection based on D-InSAR technique at the Wudongde hydropower reservoir. Environ. Earth Sci. 75, 1–13 (2016).

Yu, W. et al. Integrated remote sensing investigation of suspected landslides: a case study of the Genie Slope on the Tibetan Plateau, China. Remote Sens. 16, 2412 (2024).

Zhong, J., Li, Q., Zhang, J., Luo, P. & Zhu, W. Risk assessment of geological landslide hazards using D-InSAR and remote sensing. Remote Sens. 16, 345 (2024).

Achache, J., Fruneau, B. & Delacourt, C. Applicability of SAR interferometry for monitoring of landslides. ESA Publ. 383, 165 (1996).

Berardino, P., Fornaro, G., Lanari, R. & Sansosti, E. A new algorithm for surface deformation monitoring based on small baseline differential SAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 40, 2375–2383 (2002).

Zhu, Y. et al. Detecting long-term deformation of a loess landslide from the phase and amplitude of satellite SAR images: a retrospective analysis for the closure of a tunnel event. Remote Sens. 13, 4841 (2021).

Zhao, C., Kang, Y., Zhang, Q., Lu, Z. & Li, B. Landslide identification and monitoring along the Jinsha river catchment (Wudongde Reservoir Area), China, using the InSAR method. Remote Sens. 10, 993 (2018).

Yao, J., Yao, X. & Liu, X. Landslide detection and mapping based on SBAS-InSAR and PS-InSAR: a case study in Gongjue County, Tibet, China. Remote Sens. 14, 4728 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. The post-failure spatiotemporal deformation of certain translational landslides may follow the pre-failure pattern. Remote Sens. 14, 2333 (2022).

Guo, C. et al. Study on the creep-sliding mechanism of the Giant Xiongba ancient landslide based on the SBAS-InSAR method, Tibetan Plateau, China. Remote Sens. 13, 3365 (2021).

Li, S., Yin, C., Li, J. & Sun, T. Landslide susceptibility assessment based on remote sensing interpretation and DBN-MLP model: a case study of Yiyuan County, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 39, 493–508 (2025).

Yang, S. et al. Landslide identification in human-modified Alpine and Canyon area of the Niulan river basin based on SBAS-InSAR and optical images. Remote Sens. 15, 1998 (2023).

Ran, P. L. et al. Early identification and influencing factors analysis of active landslides in mountainous areas of Southwest China Using SBAS-InSAR. Sustainability 15, 4366 (2023).

Cui, J. H. et al. Hydrological influences on landslide dynamics in the three Gorges reservoir area: an SBAS-InSAR study in Yunyang county, Chongqing. Environ. Earth Sci. 83, 1–17 (2024).

Yan, Y. Q., Guo, C. B., Li, C. H., Yuan, H. & Qiu, Z. D. The creep-sliding deformation mechanism of the Jiaju Ancient landslide in the upstream of Dadu River, Tibetan Plateau, China. Remote Sens. 15, 592 (2023).

Ren, S. S. et al. Deformation behavior and reactivation mechanism of the Dandu ancient landslide triggered by seasonal rainfall: a case study from the East Tibetan Plateau, China. Remote Sens. 15, 5538 (2023).

Li, R., Gong, X., Zhang, G. & Chen, Z. Wide-area subsidence monitoring and analysis using time-series InSAR technology: a case study of the Turpan Basin. Remote Sens. 16, 1611 (2024).

Yan, Y. Q., Guo, C. B., Zhong, N., Liu, X. & Li, C. H. Deformation characteristics of Jiaju ancient landslide based on InSAR monitoring method, Sichuan, China. Earth Sci. 47, 4681–4697 (2022).

Yang, C., Wen, Y., Pan, X. & Yuan, D. Monitoring and analysis of landslide deformation based on SBAS-InSAR. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 0, 12–17 (2023).

Yang, F., Ding, R. & Li, Y. Analysis of spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of typical landslides in the Jinsha River Basin based on SBAS-InSAR technology. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 0, 102–107 (2024).

Li, Z. & Zhang, G. Monitoring and analyzing the spatio-temporal deformation characteristics of Muyubao landslide in Three Gorges Reservoir using Sentinel-1. J. China Three Gorges Univ. 46, 50–56 (2024).

Pan, J. P., Zhao, R. Q., Cai, Z. Y., Yuan, Y. L. & Li, P. X. Sentinel-1 decorrelation assessment based on vegetation index. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 05, 32–37+50 (2023).

Yang, Z., Sun, P. C., Xie, Q., Zhang, W. J. & Ye, K. The experiment of making DEM by GF3 Satellite Images. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 45, 53–60 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Surface deformation extraction from small baseline subset synthetic aperture radar interferometry (SBAS-InSAR) using coherence-optimized baseline combinations. GISci. Remote Sens. 59, 295–309 (2022).

Guzzetti, F., Malamud, B. D., Turcotte, D. L. & Reichenbach, P. Power-law correlations of landslide areas in central Italy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 195, 169–183 (2002).

Chen, M., Huang, D. & Jiang, Q. Slope movement classification and new insights into failure prediction based on landslide deformation evolution. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 141, 104733 (2021).

Qiu, H. et al. Do post-failure landslides become stable? Catena 249, 108699 (2025).

Hurst, H. E. Long-term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng.116, 770–799 (1951).

Li, Y. Y., Yin, K. L. & Chen, W. M. Application of R/S method in forecast of landslide deformation trend. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 32, 1291–1296 (2010).

Ma, J. Q. et al. Effects of salinity and moisture content on the strength of loess in Heifangtai, Gansu Province. China Earthq. Eng. J. 45, 819–825+886 (2023).

Ma, J. Q., Zhao, X. J., Li, S. B. & Duan, Z. Effects of High shearing rates on the shear behavior of saturated loess using ring shear tests. Geofluids 2021, 1–12 (2021).

Ma, J. Q. et al. Effects of sample preparation methods on permeability and microstructure of remolded loess. Water 15, 3469 (2023).

Papagiannaki, K., Kotroni, V., Lagouvardos, K., Diakakis, M. & Kyriakou, P. Rainfall patterns and their association with flood fatalities across diverse Euro-Mediterranean regions over 41 years. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 39 (2025).

Tie, Y. B., Jian, B. Y. & Song, Z. Damage types and hazards effects from freezing-thawing process in plateau of Western Sichuan province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 35, 241–245 (2015).

Nelson, F. E. A. Frost index number for spatial prediction of ground frost zones. Arc. Alp. Res. 19, 279–288 (1987).

Guo, D. & Wang, H. CMIP5 permafrost degradation projection: a comparison among different regions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 4499–4517 (2016).

Bontemps et al. Inversion of deformation fields time-series from optical images, and application to the long term kinematics of slow-moving landslides in Peru. Remote Sens. Environ.210, 144–158 (2018).

Lacroix, P., Araujo, G., Hollingsworth, J. & Taipe, E. Self-entrainment motion of a slow-moving landslide inferred from Landsat-8 time series. JGR Earth Surf. 124, 1201–1216 (2019).

Goldstein, R. M., Zebker, H. A. & Werner, C. L. Satellite radar interferometry: two-dimensional phase unwrapping. Radio Sci. 23, 713–720 (1988).

Li, T., Zhang, S. Y. & Zhou, C. X. Comparison among methods of filtering and phase unwrapping for SAR interferogram. J.Geod. Geodyn. 27, 59–64 (2007).

Zhao, W. S., Jiang, M. & He, X. F. Improved adaptive goldstein interferogram filter based on second kind statistics. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 45, 1200–1209 (2016).

Costantini, M. A novel phase unwrapping method based on network programming. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 36, 813–821 (1997).

Liu, F. & Pan, B. A new 3-D minimum cost flow phase unwrapping algorithm based on closure phase. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 58, 1857–1867 (2020).

Chen, Y., Zhenhong, L., Penna, N. T. & Paola, C. Generic atmospheric correction model for interferometric synthetic aperture radar observations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth123, 9202–9222 (2018).

Yu, C., Li, Z. & Penna, N. T. Interferometric synthetic aperture radar atmospheric correction using a GPS-based iterative tropospheric decomposition model. Remote Sens. Environ. 204, 109–121 (2018).

Wang, Q. J., Yu, W. Y., Xu, B. & Wei, G. G. Assessing the use of GACOS products for SBAS-InSAR deformation monitoring: a case in Southern California. Sensors 19, 3894 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Qinghai Provincial Nonferrous First Geological Exploration Institute for providing the survey data and the Maqin County Meteorological Station for providing the meteorological data. This research was funded by 2021 Qinghai Provincial “High-end Innovative Talents” Top-notch Talent Program, grant number Qing Ren Cai [2021] No. 12; and Key Project of The First Geological Exploration Institute of Qinghai Provincial Nonferrous Geology and Mineral Exploration Bureau, grant number QHYSDK-2024-01; and Key Technology Research and Development Program Project of Gansu Province, China, grant number 22YF11GA302.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M., B.L., and S.L.; methodology, Z.Z., H.S., and A.L.; software, Y.A., G.J., C.W., and J.B.; resources, J.M., B.L., G.J., C.W., and J.B.; data curation, J.M., S.L., and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, J.M., B.L., S.L., Z.Z., and H.S.; supervision, Y.A., G.J., C.W., and J.B.; funding acquisition, J.M., B.L., S.L., and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, J., Liang, A., Li, B. et al. Deformation monitoring and spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of Jungong landslide based on InSAR technology. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 76 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00131-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00131-1