Abstract

Changes to convective storm motion over urban areas may have important implications on rainfall accumulation and flood risk. Here, we investigate speed changes in storms passing over cities using weather radar data and convection-permitting numerical simulations. The observational analysis consists of tracking individual rain cells across eight cities and comparing movement speeds near the cities relative to a control upwind region. Second, we simulate ten heavy rainfall events crossing Indianapolis, Indiana, and compare cloud-layer horizontal wind speeds from two scenarios: one with and one without the city. We find that the speed of the observed rain cells decreases over and downwind of five urban areas, and seven simulations reveal dampened cloud-layer wind speeds over Indianapolis. Stronger updrafts induce horizontal wind slowing, driven by the warm urban surface. We conclude that rainfall intensification is the primary driver of enhanced urban rainfall accumulation, yet storm slowing contributes to more frequent and stronger enhancements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With more than half of the world’s population living in cities, and urban expansion and population growth projected to increase1,2, exposure to urban floods is becoming increasingly widespread3. Flood risk increases in urban areas due to a combination of factors. Changes in land surface decrease surface permeability4,5, and short-duration rainfall extremes, which are frequently linked to flash floods, have often been shown to be intensified by both global warming and urbanization6,7,8,9,10. Urban rainfall modification tends to result from three main mechanisms: first, changes to the surface energy balance frequently lead to temperature gradients between cities and their surroundings, causing the well-known Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect11, which usually enhances convection and intensifies rainfall12,13,14,15. Second, changes in surface roughness can dynamically change surface winds and convergence patterns near a city, affecting the intensity and spatial patterns of precipitation16,17,18. Lastly, increased atmospheric aerosol concentrations over cities can alter microphysical cloud properties, either enhancing or suppressing rainfall19,20,21.

Aside from modifying heavy rainfall properties, such as its amount, intensity, structure, and occurrence [e.g., refs. 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], there is also evidence suggesting that urban areas can impact the temporal structure of rainfall, i.e., by altering its timing and duration30,31,32,33. A suggested mechanism for these observed changes is that a dry urban surface may inhibit the transportation of moisture and slow down the precipitation development process34. Another hypothesis is that an urban cluster can slow down or block the movement of precipitation through a building-barrier effect resulting from increased surface roughness32,33,34,35. Similarly, urban areas have also been found to influence storm movement and dynamics by modifying airflow patterns. For example, convective precipitation can bifurcate around a city30,35,36,37 or its movement can be deviated toward it38.

Urban effects on canopy-layer winds, especially near-surface winds, have been extensively studied. Most studies find that near-surface winds are reduced over urban areas, and that this is due to the frictional drag effect from the increased surface roughness of urbanized areas39,40,41,42. Aside from this dynamic process, the thermodynamics of urban settings have also been shown to impact urban canopy wind speeds. This tends to occur when the background wind speeds are weak, and the UHI effect is strong, resulting in low-level wind acceleration toward and convergence over the thermal disturbance43,44,45,46,47. However, airflow modifications above the lower atmospheric layers, where cloud advection mostly occurs, remain less understood. Some evidence suggests that urbanization can influence wind patterns beyond the near-surface. For example, Loose and Bornstein48 found that synoptic-scale frontal movement was slowed over an urban area, or across its upwind side in the case of a strong UHI. Few studies have also shown that urban boundary layer wind patterns may be slowed down due to increased atmospheric instability and vertical mixing47,49. It is therefore important to further our understanding of urban boundary layer airflow changes because airflow directly influences the movement of precipitation fields.

The changes in the speed of convective storms over urban areas can have important implications on flood risk; for example, the slowing down of a precipitation system may lengthen heavy rainfall duration, and lead to increases in accumulated rainfall and pluvial-flood risk50,51,52,53,54,55,56. Changes in the speed of future mesoscale convective systems as a result of global warming are foreseen, with regional variations9,50. Namely, in Europe, heavy rainstorms that are more intense have a reduced storm speed and longer duration, and are predicted to become more frequent under climate change57. Here, we hypothesize that urban areas may affect heavy precipitation motion due to thermodynamic and dynamic processes that result from the modified land surface.

We aim to determine whether and how the speed of convective storms is altered over cities. We investigate how urban areas affect the speed of heavy rainfall systems by using: (i) 7 years of weather radar observations (2015–2021), and (ii) high space-time resolution simulations from a convection-permitting model. First, we identify heavy rainfall events that passed near eight urban areas located in different climates and characterized by varying forms, and track their trajectories with a storm-tracking algorithm. We then compare changes in the distributions of rain cell speeds upwind, over, and downwind of each city, relative to an upwind control area that is further away from and assumed to be unaffected by the city. Second, we focus on one study area, the city of Indianapolis (Indiana, U.S.), and evaluate changes in horizontal wind speeds over the urban area where the rain-producing clouds are embedded. We do this by comparing an “urban” simulation (with the land cover of Indianapolis) to a “no-urban” simulation (where the area of Indianapolis is replaced with the most common surrounding land cover) for 10 rainfall events. Third, we explore mechanisms that are likely responsible for the observed storm motion changes. Finally, we assess the contribution of these speed changes to rainfall accumulation over the city. Our findings reveal decreases in storm speed across multiple urban areas and their potential to enhance rainfall accumulation over cities.

Results

Rural–urban rain cells’ speed changes from radar observations

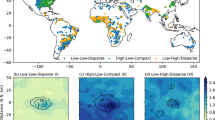

The changes in median rain cell speed and mean rainfall intensity from a control region located at the city’s surroundings (assumed to be unaffected by the urban area) to three urban locations (upwind, over, and downwind of the urban center) were quantified for the study cities (see land cover and urban structure maps in Fig. S1 and illustration of bins in Fig. S2). Figure 1a reveals that five out of the eight cities (Birmingham, London, Indianapolis, Charlotte, and Atlanta) showed statistically significant negative changes in rain cell speed at least over one urban location; usually on the downwind side and/or over the cities. The median rain cell speeds decreased by 12.2, 6.4, 10.2, 13.7, and 3.1%, respectively. In addition, statistically significant increases in rain cell mean rainfall intensity occurred for the five cities, either over the urban area or on its downwind side (Figs. 1a and S3), with median increases in mean intensity ranging from 4 to 7%. Generally, the largest cities showed the greatest and most statistically significant changes in both rain cell properties.

a Change in median object speed from the control to the three urban bins, plotted against city size. The color of the points refers to the urban bin, and the error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals of the median differences. Square (round) symbols refer to (not) significant change (p < 0.05). Purple crosses mark the median change in object mean rainfall intensity from the control to the central urban bin. Opaque crosses indicate statistically significant changes, while transparent crosses indicate non-significant changes. Cities are labeled by their two-letter acronyms: Mi (Milan), Bi (Birmingham), Be (Berlin), Lo (London), In (Indianapolis), Ch (Charlotte), Ph (Phoenix), and At (Atlanta). b Composite of mean rainfall object speed over Indianapolis, expressed as the deviation from the mean. Each rainfall object is rotated around a fixed center located at Indianapolis’s city center, based on the corresponding track’s mean direction of motion. For all tracks, the downwind direction is to the east, and the upwind direction is to the west. The black circle indicates the average radius of the city, and the city center is marked with a cross. The black, blue, green, and red dashed lines indicate the edges of the urban, upwind, downwind, and control bins, respectively.

The composite map of mean rain cell speed differences over Indianapolis is presented in Fig. 1b. Rainfall objects were rotated so that rainfall motion is from west to east. We observe that speed decreases occurred generally over the urban core and extended further downwind of it up to 60 km. The largest magnitude of these speed decreases was approximately 2 m s−1. Composite maps of the speed differences for the other study cities are provided in Figs. S4 and S5. As in Fig. 1a, Birmingham, London, Charlotte, and Atlanta displayed slower rainfall motion either above their centers, downwind of them, or both. In Birmingham, speed decreases were observed over the urban core and on the downwind side of the city, extending up to 20 km from its center. In Charlotte, the strongest decreases occurred within the city, particularly on the downwind side, reaching up to 35 km from the center. In London and Atlanta, decreases were concentrated downwind of the urban centers, extending up to 40 km and 60 km, respectively. In both cities, the upwind region (up to 40 km) showed increases in rain cell speeds (Figs. 1a, S4, and S5). We note that the speed anomalies were fairly heterogeneous across the studied domains, showing considerable spatial variability. Nevertheless, the consistent pattern of negative anomalies over the five cities suggests a consistent slowing-down urban signal, in addition to the statistically significant changes reported in Fig. 1a.

Rural-urban changes in cloud-layer wind speeds from numerical simulations

After exploring climatological rainfall speed changes across multiple cities using weather radar data, we focus on Indianapolis and explore the driving processes affecting urban-induced rainfall speed changes by simulating several convective rainfall events with an atmospheric numerical model. Median cloud-layer horizontal wind speeds (Ucloud) over the urban area were extracted from the convection-permitting numerical simulation outputs for Indianapolis and compared between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations (section “Methods”). The “urban” to “no-urban” differences were quantified as the “urban” minus “no-urban” case. The model domain setup and land use/land cover maps are shown in Fig. S6. Figure 2a displays that, out of the 10 simulated rainfall events, seven showed reduced Ucloud values over the urban area compared to the “no-urban” case, and the remaining three displayed Ucloud increases. Ucloud decreases ranged from 1.5 to 6.2% and increases from 0.5 to 7.3%. Ucloud decreases occurred along with an increase in accumulated rainfall (enhancement of 9–32%) in the “urban” case for six events (B, C, D, E, F, and G). Conversely, increases in Ucloud were also sometimes accompanied by more accumulated rainfall (events A and H) in the “urban” case. We did not find a relationship between differences in Ucloud and total rainfall accumulation between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations (Fig. 2a).

Scatter plots of (a) the difference in accumulated rainfall (ΔAcc. rain) plotted against the median difference in Ucloud, and b the median difference in Ucloud versus the difference in median wpos. All differences are between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations and are expressed as percentages relative to the “no-urban” case. The events that showed decreases in Ucloud are outlined in black.

We next explored potential mechanisms that explain the Ucloud differences. We found a significant negative linear relationship between the change in Ucloud and positive vertical wind speeds (wpos) over the urban area (p = 0.029, R2 = −0.69; Fig. 2b). We particularly note that the five events showing increased accumulated rainfall and the largest decreases in Ucloud over the city, all exhibited positive increases in wpos (B, C, D, E, and G). Potential links between Ucloud differences and other convection-related variables were also explored, such as surface and boundary layer UHI, background wind speed, and peak rainfall time; however, no clear relationships to Ucloud were found. A general trend was observed in which events with longer residence times showed stronger slowing effects, although the correlation was weak (Table S1).

Figure 3 provides an example of a vertical cross-section for a rainfall event (E) where rainfall accumulation increased, and rainfall advection speed was reduced by the urban area. This example represents the general processes seen across the other slowing events. The cross-section was taken following the mean direction of the winds at 500 hPa and averaged across an area extending 5 km from the city center (see position in Fig. S7). During this event, high values of cloud water mixing ratio (Qcloud), indicating the presence of clouds, were observed between an altitude of 2–5 km (Fig. 3d). Figure 3c shows that there was a moderate UHI (mean temperature difference at 2-m was 1 °C) that developed over the urban area, particularly on its upwind side, and that extended downwind and up to a height of 1 km. We also observed low-level air convergence (Con) close to the urban center and low-level airflow directed toward it (Fig. 3a, e). Between the center and the downwind side of the city, there was an area of strong horizontal wind (U) reduction and increased wpos near the surface (Fig. 3a, b). This upward motion extended vertically until the cloud layer (2–5 km), especially on the downwind side of the city, which also displayed clear U decreases between 3 and 5 km (Fig. 3a, b). Qcloud also increased above and downwind of the city (Fig. 3f).

Changes are presented for (a) U, b wpos, c T, e Con, and (f) Qcloud. d Cloud water mixing ratio (Qcloud,u) from the “urban” simulation, with magenta contours indicating values of 0.05 g kg−1. In (d), vector arrows represent the wind field, with the vertical component indicating vertical motion and the horizontal component representing wind speeds along the cross-section line. In (a, e), vector arrows show the difference in the wind field between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations. Note that vertical vectors are scaled by a factor of 10 relative to the horizontal direction. The dashed black lines indicate the extent of the urban area. Distances from the urban center are negative when upwind and positive when downwind.

As for the other simulations that showed reduced cloud-layer winds, a UHI effect was also visible between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations (events B, C, D, F, G, and I; Figs. S8–S13). In some cases (e.g., in C, D, and I), there was also low-level air convergence and enhanced uplift over the urban area, starting at low levels and extending upward to higher atmospheric layers containing the clouds. The hotspots of horizontal wind decrease coincided with areas of increased uplift. In simulations B, F, and G, the urban area did not show strong low-level convergence over the city compared to the other slowing events (Figs. S8, S11, and S12). Increases in vertical motion were also not as strong near the surface and occurred most strongly in higher levels of the atmosphere, around 3–5 km. In these simulations, U often decreased in areas experiencing the greatest increases in uplift strength. This indicates that, although the warm surface initiated atmospheric instability and some upward motion, uplift at the cloud layer was enhanced by another process. Figures S8c, S11c, and S12c display warmer cloud temperatures above the city, showing that convective lifting was strengthened due to the warmer and more buoyant air. We note that simulations B, F, and G showed weaker slowing effects compared to the other rainfall events (Fig. 2), indicating that the cloud’s decelerating effect was generally the strongest when there was strong low-level convergence and strong uplift over the city.

The negative relationship between ΔUcloud and Δwpos (Fig. 2b) is also apparent across the different vertical cross-sections (Figs. 3 and S8–S13). When comparing the cross-sections, areas where U decreased generally corresponded to areas where wpos increased. Notably, during the slowing events F and I, the median change in wpos over the city was small and negative (Fig. 2b). However, both cases exhibited strong localized increases in wpos within pockets of the urban area, which also coincided with locations of U decreases (Figs. S11 and S13).

Two events, H and J, showed increases in Ucloud over the city. These two events showed decreases in uplift strength over the urban area, compared to the other events (Figs. 3b, S14 and S15). This indicates that the same mechanism as for the other events drove the wind speed changes, but in the other direction; weaker uplift over the urban area, compared to the “no-urban” simulation, resulted in faster-moving clouds. During event J, rainfall and convection were suppressed by the urban area, shown by the weaker uplift and decreased rainfall accumulation over the city (Figs. 2 and S7). During event H, although convection was weaker directly over the city, it was enhanced downwind of the city, as shown by the increases in vertical motion (Fig. S14b) and increased rainfall accumulation in that region (Fig. S7). This downwind region also displayed enhanced convergence at the cloud layer (Fig. S14e). Therefore, the increases in Ucloud over the city most likely occurred due to the downwind convergence zone, which caused air to accelerate toward it. This downwind area of enhanced uplift also correlated with an area of U decrease, indicating that the slowing of rainfall advection occurred downwind (Fig. S14a, b).

Event A displayed markedly larger changes in Ucloud with negligible changes in uplift over the city compared with the other events, and it does not follow the Ucloud-wpos relationship observed for the others (Fig. 2b). The cross-sections in Fig. S16 reveal that there was a strong convergence zone downwind of the city at an altitude of 1–4 km (Fig. S16e), which was likely caused by the increase in air temperature in that location due to the UHI signal being transported downwind of the urban area (Fig. S16c). This strong area of convergence caused air to accelerate toward it, consequently accelerating cloud-layer wind speeds over the city. In this simulation, two convective systems merged over the city, and the faster advection despite stronger uplift may reflect complex interactions between urban advection and convective-system merging.

Link between rainfall advection speed and accumulated rainfall from numerical simulations

We conceptually separated two factors that are strongly associated with the initiation of flash floods: changes in high rainfall rates (ΔRainp95) and in rainfall advection speed (ΔUcloud)51. The former was defined as the difference in the 95th percentile of accumulated rainfall over the urban grid points from the “urban” to the “no-urban” simulations. Figures 4 and S17 display the changes in both these properties and in the mean rainfall accumulation over the urban grid points (ΔRain) at each output time. Overall, 63% of the data points showed increased rainfall accumulations (ΔRain > 0), and the magnitude of the change was generally higher compared to the decreasing changes (Fig. S17), with median changes of 47% and −27%, respectively. This means that, across all rainfall events and output times, increased rainfall accumulation over the city occurred more frequently than suppression, and on average, the enhancement effect was stronger.

The color of the points indicates the change in the mean accumulated rainfall (ΔRain). All changes are computed as percent differences between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations at each 15-min output time. The symbol’s shape denotes the rainfall event. Only data points where ΔRain is positive are displayed. “Acc.” (“Dec.”) refers to an increase (decrease) in Ucloud, and “int.” (“sup.”) refers to an increase (decrease) in Rainp95. The quantity N is the percent of points falling in each quadrant and ΔMed indicates the median ΔRain value in each quadrant.

Figures 4 and S17 show a strong and positive relationship between ΔRain and ΔRainp95. Among the cases of rainfall increase (ΔRain > 0; Fig. 4), the largest proportion (59%, with a median increase of 55%) exhibited rainfall intensification effects (ΔRainp95 > 0) with a reduction in advection speed (ΔUcloud < 0). An additional 26% (with a median increase of 51%) of the rainfall increase cases featured patterns of intensification and speed increases, 9% with patterns of suppression and slowing, and the remaining 6% showed patterns of suppression and speed increases. These results indicate that the urban-induced intensification of rainfall is the main driver of the increases in rainfall accumulation over the city; however, when intensification occurred together with advection slowing, the rainfall enhancement was more frequent and its magnitude was larger.

Discussion

We have investigated the changes in the speed of convective rainfall events using radar observations across eight urban areas and numerical simulations of 10 events over Indianapolis. The analysis of weather radar data revealed that the motion of convective rain cells decelerated over five cities (Birmingham, London, Indianapolis, Charlotte, and Atlanta); these were among the largest (ranging from 625 to 6340 km2), and the effect was the strongest over and downwind of the cities (Fig. 1a). It is worth noting that three cities (Milan, Berlin, and Phoenix) did not show significant changes in rain cell speeds. Differences in the geographical setting, background climate, as well as the strength and extent of the dynamic and thermodynamic effects of the urban area on the local climate may explain the observed differences. For example, in the case of Phoenix, although the urban area is generally flat, it has some topography in its surroundings. In this city, wind flow patterns may be controlled by topographic circulations or their interaction with the urban influence58. Further research is needed to better understand inter-city differences in storm speed changes and the associated mechanisms.

Ten heavy rainfall events were then simulated and analyzed for Indianapolis, where an urban-induced slowed advection is observed, using a convection-permitting model. Six of the simulations revealed a reduction in the advection speed of rainfall by showing decreased horizontal wind speeds at the cloud layer over the cities (Fig. 2a). Although some studies have indicated that the drag effect from increased surface roughness may affect both surface and planetary boundary layer wind patterns, as well as rainfall motion36, here we did not find evidence that roughness effects extended to the cloud layer and therefore decelerated the cloud-layer winds. In many of the simulations, we observed that deceleration effects due to the rough urban surface extended from the surface upward until 1 or 2 km, but not reaching the cloud layer (visible from the cross-sections; Figs. 3, S10, S12, S14, S15 and S16). Since in our simulations Indianapolis was mostly represented by openly spaced, low-rise buildings (LCZ 6) with an average height of 6.5 m, stronger building-barrier effects may be expected in cities with taller or denser urban structures.

Rather than being driven by the dynamical roughness effects of the city, the cloud-layer wind speed changes were instead linked to thermodynamic effects induced by the urban area; specifically, to changes in (upward) vertical wind speeds over the urban area compared to the “no-urban” simulations (Fig. 2b). Rising motion over an urban area may occur due to convective lifting from the thermal gradient between an urban area and its surroundings59, low-level horizontal convergence resulting from the UHI circulation60, or due to mechanical uplift effects arising from increased aerodynamic roughness61. We found that these first two mechanisms explained the observed changes in horizontal cloud motion. Four of the simulated events (C, D, E, and I) presented a well-developed UHI near the surface, along with low-level horizontal convergence over the city and increased uplift above it. This uplift then extended upward to the atmospheric layers containing the cloud, where a general decrease in speed at the cloud layer was observed. For the three other slowing events (B, F, and G), which also occurred with a UHI present, low-level wind convergence and uplift in the lower atmosphere were not as pronounced. Instead, areas of maximum vertical motion were confined to higher levels of the atmosphere, around 3–5 km, where the clouds were located. In these layers, strong uplift was driven by surface instability, which was weaker but still present. Increased uplift over the city then resulted in enhanced cloud-layer humidity (Qcloud, Figs. S8f, S11f and S12f), leading to latent heat release, warmer cloud temperatures, and enhanced convective lifting within the cloud, as also observed in Li et al.24. Figure 5 provides a summary of these mechanisms. Overall, our results are in agreement with other studies that have suggested that increased atmospheric instability and vertical mixing from a warm surface can potentially decrease horizontal wind speeds within the urban boundary layer47,49. We anticipate that the increased vertical motion from the stronger updrafts results in the vertical transport of horizontal momentum, thereby reducing horizontal winds. This type of convective momentum transport has been observed in mesoscale convective systems, where horizontal wind speeds decrease in regions of strong convection62,63.

In all rainfall events that showed a slowing effect in the “urban” compared to the “no-urban” simulations, the urban surface was consistently warmer. In several of these cases, this enhanced surface heating led to strong vertical motion above the urban area that extended to the cloud layer. This occurred for events C, D, E and I, and is illustrated as process 1. In other simulations, low-level uplift was present but weaker, and convective lifting at the cloud layer was triggered by increased humidity at the cloud layer, which through latent heat release lead to increased buoyancy. This occurred for events B, F, and G, and is illustrated as process 2. In both cases, the cloud-layer convective lifting transported horizontal momentum vertically, reducing the horizontal advection speed of rainfall.

Next, we discuss the potential contribution of the slowing of convective storms to the urban flood hazard. Intensification of the heaviest fraction of the rainfall was found to be the primary driver of increased rainfall over the city (Figs. 4 and S17). We noticed more and stronger cases of increased rainfall accumulation when rainfall intensification occurred at the same time as advection speed decreases. While the tendency of cities to intensify rainfall and consequently increase flood hazards has been examined and discussed10,18,64, our results suggest that urban-induced slowing of rainfall advection over cities likely contributes to further increasing this hazard, and that urban rainfall enhancement and slowing down are primarily coupled processes (Fig. 4). Our findings imply that both the intensification and slowing down of rainfall may arise from the same underlying mechanism, specifically the increased uplift induced by the urban area.

One factor not accounted for in our radar data analysis is the potential influence of urban areas on storm life cycles and their effect on rain cell movement speed. Urban areas are known to increase the frequency of storm initiations over them27,65 or affecting processes such as storm merging and splitting25,26. Consequently, this may also be influencing the climatological speed patterns. However, the numerical simulation analysis has demonstrated that urban areas can dynamically slow down rainfall advection, suggesting that the effects are not solely due to these life cycle changes. While numerical experiments that compare rainfall simulations over urban and non-urban areas are widely used to study urban rainfall signatures [e.g., refs. 6,10,29], this approach has some limitations. For example, model outputs may be sensitive to initial atmospheric conditions and the physical parameterization schemes used66,67,68,69, which can introduce uncertainty in the quantification of the urban effect70. Therefore, addressing such uncertainty with ensemble modeling approaches provides opportunities to determine more robust urban signals [e.g., refs. 34,71,72]. Furthermore, our findings suggest that a better understanding of the conditions driving rainfall slowing is needed. For example, we found that longer rainfall residence times may be associated with stronger urban influences on rainfall. This association could arise because slower-moving rainfall systems or larger cities prolong the time rainfall spends over an urban area, increasing the potential for urban-induced perturbations73.

To summarize, we have explored how urban areas impact the advection speed of heavy rainfall, which is a key rainfall property for flood hazard50,51,52,53,54,55,56, and remains largely unexplored. Our results have shown that storm speed is often reduced over cities, mostly because of thermodynamic factors. The effect is more pronounced in large cities and frequently occurs alongside heavy rainfall intensification. This indicates that there is a potential for heavy rainfall duration to be lengthened over cities, ultimately increasing storm rainfall volumes. Although our results also displayed cases of rainfall movement acceleration over some cities or simulations, this does not contradict the broader implication that urbanization can contribute to increasing flood hazards. The intensification and slowing of even a subset of rainfall events, rather than all events, can still lead to a significant increase in flood risk, especially given that the events studied were rainfall extremes. As urban areas are expected to become more populated in the future2, we must deepen our understanding of the components and mechanisms that affect the intensification and slowing down of urban heavy rainfall to better forecast its impact on future cities.

Methods

Study cities

The studied urban areas are located in Europe (Milan, Italy; Berlin, Germany; and London and Birmingham, United Kingdom) and the United States (Phoenix, Arizona; Charlotte, North Carolina; Atlanta, Georgia; and Indianapolis, Indiana). These cities were selected because they had good-quality radar data available and were located in areas that are generally less affected by other rainfall-influencing factors, such as large bodies of water, mountainous terrain, or proximity to other large urbanized areas, or where the impact of these factors is expected to be small. Additionally, the cities were located in different geographical regions and represented a variety of urban forms, based on their Local Climate Zones (LCZ)74. These eight urban areas have also been shown to modify heavy rainfall properties, mainly by intensifying it and changing its spatial structure27. Maps of their LCZs, produced with data from Demuzere et al.75,76,77,78, are shown in Fig. S1. The boundaries of the urban areas were defined following urban area classifications from regional agencies79,80.

Weather radar data and analysis

The radar data analysis was performed with data from 7 years (2015–2021) for the summertime months only (May to September), when the studied cities experience heavy rainfall. We used composite weather radar data products of rainfall rate, which were quality-controlled and provided by the data agencies listed below. For the U.S. cities, we used data at 1 km and 4 min resolution, obtained from the Multi-Radar Multi-Sensor Surface Precipitation Rate product from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction81. These data are from a network of S-band radars and are corrected with numerical weather prediction model data. For the European cities, the data used was at 1 km and 5 min resolution and was from networks of C-band weather radars. We used the fourth-generation weather radar system of MeteoSwiss82 for Milan, the Radar Climatology (RADKLIM) data set83 from the German Weather Service (DWD) for Berlin, and the Met Office’s NIMROD product84 for the UK cities. The weather radar data obtained in this study were identical to those used in Torelló-Sentelles et al.27.

We followed the methodology of Torelló-Sentelles et al.27 to track heavy rainfall events and extract different rainfall properties. The Iterative Rain Cell Tracking algorithm (IRT, Moseley et al.85) was used to track heavy rainfall events. A threshold of 10 mm h−1 for intensity and 9 km2 for area was used to identify rainfall objects. The IRT then linked these objects to different convective precipitation tracks. A threshold of 15 min was applied to filter out unrealistic tracks with a short lifetime. The position of each object relative to the city centers was determined by extracting the distance from the city center to each object’s weighted center of mass, and establishing if it was upwind or downwind of the city center by considering each track’s mean direction of motion. All rainfall objects were included in our analysis, regardless of whethertheir tracks passed over the city. Rain cell movement speed was computed by the IRT algorithm at each time step by calculating the distance between the weighted center-of-mass positions of the rain cell at two consecutive time steps.

Three urban bins (urban, upwind, and downwind) and an upwind control bin were created for each urban area. The footprints of the bins were relative to the size of each city and were rotated according to each track’s mean direction of motion. The urban bin extended up to 0.5 times the average city radius (R). The upwind and downwind extended from 0.5 to 1.5 R, and the control from 1.5 to 2 R. Figure S2 illustrates the binning setup for one rainfall track. Changes in median rain cell speed and mean rainfall intensity (Figs. 1 and S3) were computed at each bin, relative to the control bin. The control bin was assumed to be sufficiently distant from the city to remain unaffected by it, but placed not far enough away from the city for rainfall characteristics to be altered by regional effects, such as differences in land cover, land use, or topography. A non-parametric permutation test was used to test for statistical significance of the median changes86, and the confidence intervals were computed using bootstrap resampling. We tested different distance thresholds for the bins and found that, although the bin positioning sometimes affected the magnitude of rainfall property changes, the overall patterns across cities remained consistent.

A composite map of mean object speed was created by: (i) obtaining each rainfall object’s estimated movement speed from the storm-tracking algorithm, (ii) assigning this speed value to each grid point pertaining to that object, (iii) rotating each rainfall object around the city center based on its track’s mean direction of motion, and (iv) computing the composite mean of all the rotated objects. Objects with speed values over 30 m s−1 were removed from this analysis to remove rain cells with unrealistic speeds. Figure 1b shows the deviation from the composite mean across all grid points for Indianapolis and the maps for the other cities are presented in Figs. S4 and S5. The object rotation was performed to assess the changes relative to the city’s upwind and downwind regions. In this rotated frame, the eastern and western regions correspond to the downwind and upwind areas, respectively. Regions north and south of the city center may include objects that did not cross the city but moved laterally past it, as well as contributions from large rain cells that partly overlapped the urban area.

We note that our radar data analysis is subject to some limitations. For example, storm motion may also be influenced by factors other than the urban area, such as potential radar artifacts, heterogeneities of the land use/land cover in some urban surroundings, or, in the cases of Milan and Phoenix, their relative proximity to areas of higher elevation, especially in the control bins. In addition, uncertainties may stem from the rainfall tracking algorithm when identifying and tracking rainfall objects throughout their lifetime, and during classification of merging and splitting events. Inaccuracies in rain cell velocities may also arise because rain cell intensity fields are often heterogeneous and irregularly shaped, which can complicate the determination of their boundaries and center point, and consequently, their movement. However, such uncertainties are not expected to have a major influence on our analysis, as potential misclassifications should occur randomly across the study domain, thus not introducing systematic biases between urban and rural areas.

WRF simulations

The convection-permitting simulations were for the city of Indianapolis (Figs. S1 and S6). This city was selected for our analysis because it displayed both storm intensification and deceleration within the city in the weather radar data analysis (section “Results”), and relative to all the study cities, it has a strongly homogeneous surrounding land cover (dominated by croplands), the terrain is flat, and is not near other large urban clusters.

We numerically simulated 10 convective summer rainfall events that crossed the city using the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model (version 4.3.3)87. These events were chosen because of their weak synoptic forcing, which was estimated by using the convective adjustment time scale88,89,90, and as WRF simulates them well91. The numerical simulations were set up as the ones performed for the city of Indianapolis in ref. 91, who evaluated changes in rainfall intensity as a result of the urban area’s presence. Figure S6a shows the model domain setup. The outer and inner domains had a horizontal grid spacing of 9-, 3-, and 1-km, respectively. The RRTMG shortwave and longwave schemes92, the single-moment 6-class microphysics scheme (WSM6)93, the revised MM5 scheme94, the Noah-MP land surface model95,96, the Kain-Fritsch scheme (for the 9-km domain only)97, and the Building Environment Parameterization98 were used. The urban land use and cover were represented using WUDAPT-derived LCZ maps, which provide information on typical urban morphological characteristics99. Boundary and initial conditions, with a horizontal grid spacing of 0.25°, were acquired from the hourly ERA5 climate reanalysis product100. The model output frequency was set to 15 min and the data used for the analysis was from the inner 1-km domain. The simulations were evaluated against rainfall data obtained from weather radars that were bias-corrected using ground gauges81 and are reported in ref. 91.

Relevant information about the simulated rainfall events is summarized in Table S1. Each rainfall event was simulated under two scenarios: an “urban” case using the current land use/land cover of Indianapolis (Fig. S6c), and a “no-urban” case where the city’s land use was replaced with the dominant surrounding land cover (Fig. S6b), with this being the only modification in the model. The “no-urban” land use/land cover maps were created using the WUDAPT-to-WRF (W2W) package99. Time series of accumulated rainfall within the urban area for both scenarios are displayed in Fig. S18.

To quantify the storm speed from the simulations, we computed the mean horizontal wind speed averaged over: all vertical levels, urban grid points, output times where the mean accumulated rainfall over the urban area was above 0.025 mm per 15 min, and grid points (in both the horizontal and vertical directions) where the cloud water mixing ratio (Qcloud) was above 0.05 g kg−1. The mean accumulated rainfall threshold was imposed so that output times without substantial rain over the city were excluded. This computed variable, hereafter named Ucloud, served as a proxy for rain-producing cloud movement speed. Here, we assumed that advection controlled the movement of convective cells since the mean winds in the tropospheric layer in which clouds are situated tend to be strongly related to convective cell movement51,101. Cloud-layer wind speeds were used as an alternative to rain cell tracking in the simulation analysis because, at the coarser 15-min temporal resolution (compared with 4 or 5 min for the radar), rainfall could not be tracked satisfactorily, and estimates of individual storm movement were often noisy.

We computed the differences in accumulated rainfall and the medians of Ucloud between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations over the urban area for all rainfall events. Both variables are plotted in Fig. 2a. Next, to explore whether enhanced vertical motion over the urban area was related to changes in horizontal cloud-layer wind speeds, we computed the positive vertical wind speeds (wpos) over the urban area, also considering values across all vertical levels and output times where the mean accumulated rainfall over the urban area was above 0.025 mm per 15 min. In Fig. 2b, we plotted the difference in the medians of Ucloud and wpos, also between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations. A simple linear regression analysis was performed to quantify the relationship between changes in Ucloud and wpos. We also explored links between Ucloud differences and other model variables, including boundary layer temperature differences, background wind speed, peak rainfall time, and rainfall residence time over the city. Data for the latter two variables are displayed in Table S1. Peak rainfall time was defined as the time at which the rainfall, averaged over the urban area in the “urban” simulation, reached its maximum. Residence time was computed as the total period of time during which the mean accumulated rainfall over the urban area exceeded 0.025 mm, in the “urban” simulation.

The mechanisms related to Ucloud changes were further explored by analyzing area-averaged cross-sections of different convection-related variables. Eleven vertical cross-sections, oriented to match the mean direction of the horizontal winds at 500 hPa from the “urban” simulation over the inner 1-km domain, were taken within an area extending 5 km from the city center in each direction perpendicular to the cross-section’s direction. The dashed lines in Fig. S7 display the positions of the cross-section lines for each rainfall event. An average of these multiple cross-sections was then taken per rainfall event. We explored the cross-sections of: Qcloud and the change, defined as the difference between the “urban” and “no-urban” case in, horizontal wind speeds (ΔU), positive vertical wind speed (Δwpos), temperature (ΔT), convergence of winds (ΔCon), and the wind field difference. All the cross-sections were averaged over the simulation output times during which the mean accumulated rainfall over the urban area exceeded 0.025 mm per 15 min in both the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations.

Last, we examined the potential effects of rainfall intensification and reduced advection speed on accumulated rainfall over the urban area. Rainfall intensification was defined as the change in the 95th percentile of accumulated rainfall at each 15-min output time between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations (ΔRainp95). This variable quantified the changes to the high rainfall rates. In Fig. 4 we display ΔRainp95, the changes in mean Ucloud (ΔUcloud), and the changes in mean accumulated rainfall over the urban area (ΔRain), for all output times and rainfall events. All of these variables were computed per simulation output time (every 15 min) and output times where the mean accumulated rainfall over the urban area was below 0.025 mm per 15 min were excluded from this analysis as well.

There are some limitations in the WRF modeling framework, including uncertainties in how the model parameterizes the urban environment and urban-related atmospheric processes. Yet, WRF is a common tool to simulate urban rainfall [e.g., refs. 7,10,24,31,34,61,91]. For example, although we ran the simulations at relatively high resolution (1 km horizontal grid spacing), the grid spacing is still too coarse to fully resolve individual updrafts and downdrafts, introducing some uncertainty in the representation of convective processes. In addition, although we used maps of LCZs at 1 km resolution to represent the urban land use and land cover, this representation is still more homogeneous than the actual urban fabric. Cities exhibit considerable sub-kilometer heterogeneity in building morphology, land cover, and surface properties, therefore, some local-scale processes may not be fully represented in the model. We note that our analysis focused on rainfall and convection-related variable changes throughout the entire rainfall event and across the urban area, which may have overlooked localized processes occurring at smaller spatial and temporal scales. Furthermore, our quantification of rainfall slowing, based on differences between the “urban” and “no-urban” simulations above the city, may partly reflect changes in rainfall patterns unrelated to deceleration, such as shifts in the spatial location of rainfall. In addition, since our study concentrated on the urban area, the effects occurring in the city peripheries, such as the lateral sides of the city or downwind regions where airflow convergence has been reported in some studies37,102, were not quantified.

Data availability

The following weather radar data sets were used in the radar data analysis: the fourth-generation weather radar system of MeteoSwiss82; the RADKLIM quasi gauge-adjusted 5-min precipitation rate from the Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD)83; the 1 km Resolution UK Composite Rainfall Data from the Met Office Nimrod System84 via the NCAS British Atmospheric Data Centre103; and the Multi-RADAR Multi-Sensor (MRMS) Archiving81 via the Iowa Environmental Mesonet104. We obtained the following urban boundary data sets: the administrative boundary data sets for European study areas for 2020 from Eurostat80, and the 2020 U.S. urban area delineations from the Census Bureau79. The rainfall data product “GaugeCorrQPE01H,” which was used to validate the WRF simulations, is available from the Multi-Radar Multi-Sensor (MRMS) archive81 at the Iowa Environmental Mesonet from Iowa State University (https://mtarchive.geol.iastate.edu/).

References

Seto, K. C., Sánchez-Rodríguez, R. & Fragkias, M. The new geography of contemporary urbanization and the environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 35, 167–194 (2010).

UN-DESA. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs https://doi.org/10.18356/b9e995fe-en (2018).

Swain, D. L. et al. Increased flood exposure due to climate change and population growth in the United States. Earth’s Future 8, e2020EF001778 (2020).

Feng, B., Zhang, Y. & Bourke, R. Urbanization impacts on flood risks based on urban growth data and coupled flood models. Nat. Hazards 106, 613–627 (2021).

Prosdocimi, I., Kjeldsen, T. R. & Miller, J. D. Detection and attribution of urbanization effect on flood extremes using nonstationary flood-frequency models. Water Resour. Res. 51, 4244–4262 (2015).

Deng, Z., Villarini, G. & Wang, Z. Climate change dominates over urbanization in tropical cyclone rainfall patterns. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 54 (2025).

Deng, Z. et al. Stronger exacerbation of extreme rainfall at the hourly than daily scale by urbanization in a warming climate. J. Hydrol. 633, 131025 (2024).

Peleg, N., Koukoula, M. & Marra, F. A 2 °C warming can double the frequency of extreme summer downpours in the Alps. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 216 (2025).

Prein, A. F. et al. Increased rainfall volume from future convective storms in the US. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 880–884 (2017).

Zhang, W., Villarini, G., Vecchi, G. A. & Smith, J. A. Urbanization exacerbated the rainfall and flooding caused by Hurricane Harvey in Houston. Nature 563, 384–388 (2018).

Oke, T. The energetic basis of urban heat island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 108, 1–24 (1982).

Ganeshan, M., Murtugudde, R. & Imhoff, M. L. A multi-city analysis of the UHI-influence on warm season rainfall. Urban Clim. 6, 1–23 (2013).

Han, J.-Y. & Baik, J.-J. A theoretical and numerical study of urban heat island-induced circulation and convection. J. Atmos. Sci. 65, 1859–1877 (2008).

Olfe, D. B. & Lee, R. L. Linearized calculations of urban heat island convection effects. J. Atmos. Sci. 28, 1374–1388 (1971).

Shepherd, J. M. & Burian, S. J. Detection of urban-induced rainfall anomalies in a major coastal city. Earth Interact. 7, 1–17 (2003).

Liu, J. & Niyogi, D. Meta-analysis of urbanization impact on rainfall modification. Sci. Rep. 9, 7301 (2019).

Thielen, J., Wobrock, W., Gadian, A., Mestayer, P. G. & Creutin, J. D. The possible influence of urban surfaces on rainfall development: a sensitivity study in 2D in the meso-γ-scale. Atmos. Res. 54, 15–39 (2000).

Yang, L., Smith, J. & Niyogi, D. Urban impacts on extreme monsoon rainfall and flooding in complex terrain. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5918–5927 (2019).

Carrió, G. G. & Cotton, W. R. Urban growth and aerosol effects on convection over Houston. Part II: dependence of aerosol effects on instability. Atmos. Res. 102, 167–174 (2011).

Diem, J. E. & Brown, D. P. Anthropogenic impacts on summer precipitation in Central Arizona, U.S.A. Prof. Geogr. 55, 343–355 (2003).

van den Heever, S. C. & Cotton, W. R. Urban aerosol impacts on downwind convective storms. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 46, 828–850 (2007).

Huang, J., Fatichi, S., Mascaro, G., Manoli, G. & Peleg, N. Intensification of sub-daily rainfall extremes in a low-rise urban area. Urban Clim. 42, 101124 (2022).

Kingfield, D. M., Calhoun, K. M., de Beurs, K. M. & Henebry, G. M. Effects of city size on thunderstorm evolution revealed through a multiradar climatology of the Central United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 57, 295–317 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Strong intensification of hourly rainfall extremes by urbanization. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088758 (2020).

Lorenz, J. M., Kronenberg, R., Bernhofer, C. & Niyogi, D. Urban rainfall modification: observational climatology over Berlin, Germany. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 731–746 (2019).

Niyogi, D. et al. Urban modification of thunderstorms: an observational storm climatology and model case study for the Indianapolis urban region. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 50, 1129–1144 (2011).

Torelló-Sentelles, H., Marra, F., Koukoula, M., Villarini, G. & Peleg, N. Intensification and changing spatial extent of heavy rainfall in urban areas. Earth’s Future 12, e2024EF004505 (2024).

Yang, P., Ren, G. & Yan, P. Evidence for a strong association of short-duration intense rainfall with urbanization in the Beijing urban area. J. Clim. 30, 5851–5870 (2017).

Zhuang, Q. et al. Contradictory influences of urbanization on intense convective rainfall in a subtropical city. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 104020 (2024).

Guo, X., Fu, D. & Wang, J. Mesoscale convective precipitation system modified by urbanization in Beijing city. Atmos. Res. 82, 112–126 (2006).

Niyogi, D., Osuri, K. K., Busireddy, N. K. R. & Nadimpalli, R. Timing of rainfall occurrence altered by urban sprawl. Urban Clim. 33, 100643 (2020).

Yu, M. & Liu, Y. The possible impact of urbanization on a heavy rainfall event in Beijing. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 8132–8143 (2015).

Zhu, X. et al. Impact of urbanization on hourly precipitation in Beijing, China: spatiotemporal patterns and causes. Glob. Planet. Change 172, 307–324 (2019).

Wan, H. & Zhong, Z. Ensemble simulations to investigate the impact of large-scale urbanization on precipitation in the lower reaches of Yangtze River Valley, China. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 140, 258–266 (2014).

Bornstein, R. & Lin, Q. Urban heat islands and summertime convective thunderstorms in Atlanta: three case studies. Atmos. Environ. 34, 507–516 (2000).

Dou, J., Bornstein, R., Miao, S., Sun, J. & Zhang, Y. Observation and simulation of a bifurcating thunderstorm over Beijing. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 59, 2129–2148 (2020).

Dou, J., Bornstein, R., Sun, J. & Miao, S. Impacts of urban heat island intensities on a bifurcating thunderstorm over Beijing. Urban Clim. 55, 101955 (2024).

Lin, Y. et al. Urbanization-induced land and aerosol impacts on storm propagation and hail characteristics. J. Atmos. Sci. 78, 925–947 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Observed surface wind speed declining induced by urbanization in east China. Clim. Dyn. 50, 735–749 (2018).

Liu, J., Gao, Z., Wang, L., Li, Y. & Gao, C. Y. The impact of urbanization on wind speed and surface aerodynamic characteristics in Beijing during 1991-2011. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 130, 311–324 (2018).

Zhang, N., Gao, Z., Wang, X. & Chen, Y. Modeling the impact of urbanization on the local and regional climate in Yangtze River Delta, China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 102, 331–342 (2010).

Zhang, Z. & Wang, K. Quantifying and adjusting the impact of urbanization on the observed surface wind speed over China from 1985 to 2017. Fundam. Res. 1, 785–791 (2021).

Bornstein, R. D. & Johnson, D. S. Urban-rural wind velocity differences. Atmos. Environ. (1967) 11, 597–604 (1977).

Fortuniak, K., Kłysik, K. & Wibig, J. Urban-rural contrasts of meteorological parameters in Łódź. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 84, 91–101 (2006).

Lee, D. O. The influence of atmospheric stability and the urban heat island on urban-rural wind speed differences. Atmos. Environ. (1967) 13, 1175–1180 (1979).

Sun, Y., Zhang, N., Ao, X. & Gao, Y. Numerical studies on the influence of building morphology on urban canopy wind speed. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 16, e2023MS003881 (2024).

Wong, K. K. & Dirks, R. A. Mesoscale perturbations on airflow in the urban mixing layer. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 17, 677–688 (1978).

Loose, T. & Bornstein, R. D. Observations of mesoscale effects on frontal movement through an urban area. Mon. Weather Rev. 105, 563–571 (1977).

Zhang, N., Wang, X., Chen, Y., Dai, W. & Wang, X. Numerical simulations on influence of urban land cover expansion and anthropogenic heat release on urban meteorological environment in Pearl River Delta. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 126, 469–479 (2016).

Chan, S. C. et al. Large-scale dynamics moderate impact-relevant changes to organised convective storms. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 8 (2023).

Doswell, C. A., Brooks, H. E. & Maddox, R. A. Flash flood forecasting: an ingredients-based methodology. Weather Forecast. 11, 560–581 (1996).

Hu, H., Feng, Z. & Leung, L.-Y. R. Linking flood frequency with mesoscale convective systems in the US. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL092546 (2021).

Meyer, J., Neuper, M., Mathias, L., Zehe, E. & Pfister, L. Atmospheric conditions favouring extreme precipitation and flash floods in temperate regions of Europe. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 6163–6183 (2022).

Morin, E. & Yakir, H. Hydrological impact and potential flooding of convective rain cells in a semi-arid environment. Hydrol. Sci. J. 59, 1353–1362 (2014).

Paschalis, A., Fatichi, S., Molnar, P., Rimkus, S. & Burlando, P. On the effects of small scale space-time variability of rainfall on basin flood response. J. Hydrol. 514, 313–327 (2014).

Yakir, H. & Morin, E. Hydrologic response of a semi-arid watershed to spatial and temporal characteristics of convective rain cells. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 393–404 (2011).

Kahraman, A., Kendon, E. J., Chan, S. C. & Fowler, H. J. Quasi-stationary intense rainstorms spread across Europe under climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL092361 (2021).

Brandi, A., Martilli, A., Salamanca, F. & Georgescu, M. Urban boundary-layer flows in complex terrain: dynamic interactions during a hot and dry summer season in Phoenix, Arizona. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 3099–3116 (2024).

Chiu, C. T. et al. An analytical approximation of urban heat and dry islands and their impact on convection triggering. Urban Clim. 46, 101346 (2022).

Findlay, B. F. & Hirt, M. S. An urban-induced meso-circulation. Atmos. Environ. (1967) 3, 537–542 (1969).

Rajeswari, J. R., Srinivas, C. V., Yesubabu, V., Hari Prasad, D. & Venkatraman, B. Impacts of urbanization, aerodynamic roughness, and land surface processes on the extreme heavy rainfall over Chennai, India. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD034017 (2021).

Badlan, R. L., Lane, T. P., Moncrieff, M. W. & Jakob, C. Insights into convective momentum transport and its parametrization from idealized simulations of organized convection. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 143, 2687–2702 (2017).

Wu, X. & Yanai, M. Effects of vertical wind shear on the cumulus transport of momentum: observations and parameterization. J. Atmos. Sci. 51, 1640–1660 (1994).

Peleg, N. et al. Mapping storm spatial profiles for flood impact assessments. Adv. Water Resour. 166, 104258 (2022).

Haberlie, A. M., Ashley, W. S. & Pingel, T. J. The effect of urbanisation on the climatology of thunderstorm initiation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 141, 663–675 (2015).

Ancell, B. C., Bogusz, A., Lauridsen, M. J. & Nauert, C. J. Seeding chaos: the dire consequences of numerical noise in NWP perturbation experiments. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 615–628 (2018).

Bolgiani, P. et al. Numerical simulation of a heavy precipitation event in the vicinity of Madrid-Barajas International Airport: sensitivity to initial conditions, domain resolution, and microphysics parameterizations. Atmosphere 9, 329 (2018).

Jee, J.-B. & Kim, S. Sensitivity study on high-resolution WRF precipitation forecast for a heavy rainfall event. Atmosphere 8, 96 (2017).

Tewari, M. et al. Understanding the sensitivity of WRF hindcast of Beijing extreme rainfall of 21 July 2012 to microphysics and model initial time. Atmos. Res. 271, 106085 (2022).

Yu, M., Miao, S. & Zhang, H. Uncertainties in the impact of urbanization on heavy rainfall: case study of a rainfall event in Beijing on 7 August 2015. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 6005–6021 (2018).

Forster, A., Augros, C. & Masson, V. Urban influence on convective precipitation in the Paris region: Hectometric ensemble simulations in a case study. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 3028–3051 (2024).

Zhong, S. & Yang, X.-Q. Ensemble simulations of the urban effect on a summer rainfall event in the Great Beijing Metropolitan Area. Atmos. Res. 153, 318–334 (2015).

Schmid, P. E. & Niyogi, D. Impact of city size on precipitation-modifying potential. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5263–5267 (2013).

Stewart, I. D. & Oke, T. R. Local climate zones for urban temperature studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 1879–1900 (2012).

Demuzere, M., Bechtel, B., Middel, A. & Mills, G. Mapping Europe into local climate zones. PLoS ONE 14, e0214474 (2019).

Demuzere, M., Bechtel, B., Middel, A. & Mills, G. European LCZ map. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13322450.v1 (2020).

Demuzere, M. et al. Combining expert and crowd-sourced training data to map urban form and functions for the continental US. Sci. Data 7, 264 (2020).

Demuzere, M. et al. Conus-wide LCZ map and training areas. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11416950 (2021).

Census Bureau. 2020 census qualifying urban areas and final criteria clarifications. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/12/29/2022-28286/2020-census-qualifying-urban-areas-and-final-criteria-clarifications (2022).

Eurostat. Urban audit 2020—area management—dataset. https://gisco-services.ec.europa.eu/distribution/v2/urau/ (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Multi-radar multi-sensor (MRMS) quantitative precipitation estimation: initial operating capabilities. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 621–638 (2016).

Germann, U., Boscacci, M., Gabella, M. & Sartori, M. Peak performance: radar design for prediction in the Swiss Alps. Meteorol. Technol. Int. 4, 42–45 (2015).

Winterrath, T. et al. Radklim version 2017.002: reprocessed quasi gauge-adjusted radar data, 5-minute precipitation sums (YW). Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) https://doi.org/10.5676/DWD/RADKLIM_YW_V2017.002 (2018).

Golding, B. W. Nimrod: a system for generating automated very short range forecasts. Meteorol. Appl. 5, 1–16 (1998).

Moseley, C., Henneberg, O. & Haerter, J. O. A statistical model for isolated convective precipitation events. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 360–375 (2019).

Ernst, M. D. Permutation methods: a basis for exact inference. Stat. Sci. 19, 676–685 (2004).

Skamarock, W. C. & Klemp, J. B. A time-split nonhydrostatic atmospheric model for weather research and forecasting applications. J. Comput. Phys. 227, 3465–3485 (2008).

Done, J. M., Craig, G. C., Gray, S. L., Clark, P. A. & Gray, M. E. B. Mesoscale simulations of organized convection: importance of convective equilibrium. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 132, 737–756 (2006).

Koukoula, M., Schwartz, C. S., Nikolopoulos, E. I. & Anagnostou, E. N. Understanding the impact of soil moisture on precipitation under different climate and meteorological conditions: a numerical sensitivity study over the conus. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2021JD035096 (2021).

Zimmer, M., Craig, G. C., Keil, C. & Wernli, H. Classification of precipitation events with a convective response timescale and their forecasting characteristics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L05802 (2011).

Torelló-Sentelles, H., Villarini, G., Koukoula, M. & Peleg, N. Impacts of urban dynamics and thermodynamics on convective rainfall across different urban forms. Urban Clim. 62, 102499 (2025).

Iacono, M. J. et al. Radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases: calculations with the AER radiative transfer models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D13103 (2008).

Hong, S. & Lim, J.-O. J. The WRF single-moment 6-class microphysics scheme (WSM6). Asia Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 42, 129–151 (2006).

Jiménez, P. A. et al. A revised scheme for the WRF surface layer formulation. Mon. Weather Rev. 140, 898–918 (2012).

Niu, G.-Y. et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 1. Model description and evaluation with local-scale measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D12109 (2011).

Yang, Z.-L. et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 2. Evaluation over global river basins. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D12110 (2011).

Kain, J. S. The Kain-Fritsch convective parameterization: an update. J. Appl. Meteorol. 43, 170–181 (2004).

Martilli, A., Clappier, A. & Rotach, M. W. An urban surface exchange parameterisation for mesoscale models. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 104, 261–304 (2002).

Demuzere, M., Argüeso, D., Zonato, A. & Kittner, J. W2W: a Python package that injects WUDAPT’s local climate zone information in WRF. J. Open Source Softw. 7, 4432 (2022).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Chappell, C. F. Quasi-stationary convective events in mesoscale meteorology and forecasting (ed. Ray, P. S.) 289–310 (American Meteorological Society, 1986).

Dou, J., Wang, Y., Bornstein, R. & Miao, S. Observed spatial characteristics of Beijing urban climate impacts on summer thunderstorms. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 54, 94–105 (2015).

Met Office. 1 km resolution UK composite rainfall data from the Met Office Nimrod system. NCAS British Atmospheric Data Centre https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/27dd6ffba67f667a18c62de5c3456350 (2003).

NOAA. Multi-radar multi-sensor (MRMS) archiving. Iowa Environmental Mesonet https://mtarchive.geol.iastate.edu/ (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), Grant 194649 (“Rainfall and floods in future cities”). The authors thank three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped improve the clarity and quality of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T.S. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and visualization. M.K. contributed to methodology, software, and writing—review and editing. G.V. contributed to methodology, writing—review and editing, and supervision. F.M. contributed to methodology, and writing—review and editing. N.P. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the co-author, G.V., is an Editorial Board Member of npj Natural Hazards. They had no role in the peer review or decision-making process of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Torelló-Sentelles, H., Koukoula, M., Villarini, G. et al. When storms slow down: urban effects on rainfall accumulation and flood hazard. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 106 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00158-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00158-4