Abstract

Accelerating global sea-level rise (SLR) is fundamentally restructuring coastal flood regimes, particularly in complex estuarine systems where fluvial-tidal interactions govern hydrological extremes. In this study, we reveal a significant increasing trend in compound flooding probability across 20 strategically selected basins spanning tropical mega-deltas to high-latitude systems, where extreme fluvial flooding coincides with high-tide flooding. CMIP6-driven ensemble modeling reveals disparate growth rates between flood drivers, specifically a 273.6% (p < 0.01) increase in high-tide flooding frequency contrasted with a 10.6% fluvial flooding frequency increase, highlighting their markedly divergent responses to climatic forcing. With high-resolution fluvial flooding and high-tide flooding coupling hydrodynamic simulation, SLR-driven compound flooding will affect upstream regions farther from the estuary due to the backwater effect, amplifying inundation extent by 23–54% compared to single-flood scenarios under 99th percentile compound extremes. Our findings emphasize that SLR fundamentally reshapes fluvial flood dynamics through estuarine-tributary coupling, a key mechanism for interpreting shifting flood impacts under a changing climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The escalating frequency of extreme precipitation events under global warming has substantially increased fluvial flooding (FF) risks, while concurrent sea-level rise (SLR) has emerged as a critical planetary boundary challenge1,2,3. Crucially, hydrodynamic coupling between upstream flood waves and estuarine tidal anomalies amplifies compound flooding (CF) through nonlinear stage-discharge interactions4,5. Emerging evidence from European coastal systems6, North American watersheds7, and major Asian deltas8 demonstrates a consistent and substantial increase in CF occurrence probability since the pre-industrial era9, with particularly pronounced intensification in urbanized deltaic regions10. These cascading hydrological-marine forcings disproportionately threaten socioeconomically vulnerable communities in low-lying coastal zones, potentially doubling economic exposure by 2050 under SSP2-4.5 scenarios11,12. Consequently, the impacts of extreme CF events demand urgent attention under climate change13.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) projections on SLR have garnered widespread attention and recognition worldwide, forecasting an increase of 40–48 cm under the 1.5 °C pathway over the coming century14,15,16. This anticipated rise, coupled with coastal land subsidence17, intensification of tropical storm surges due to global warming5, and fluvial floods caused by extreme rainfall18,19,20, is poised to exacerbate CF disasters in coastal regions globally21,22. An unequivocal trend indicates an increase in floods within small-to-medium-sized basins23. However, due to the complexity of numerical model simulations and limited data, the augmentation and intensification of floods in large basins24,25, as well as the high-resolution representation of flood inundation in downstream estuarine regions, remain constrained26,27. Moreover, given that these disasters are influenced by both high-tide flooding (HTF) and FF, and considering the complexity of their underlying mechanisms, it is challenging to differentiate and analyze fluvial flooding from high-tidal floods within the same compound event28. Consequently, identifying whether floodwater or tidal levelshas a greater impact on these disaster events remains difficult, and quantifying the contribution rates of fluvial flooding or storm surges to the overall disaster is equally challenging29,30,31. These limitations pose significant hurdles for comprehensive disaster prevention strategies in coastal cities32. Thus, a notable gap in existing research highlights the lack of quantitative analysis on the coincidence of HTF and FF in global basins, as well as the unexamined amplification effect of high tides on FF, despite extensive focus on SLR-induced flood risks in coastal cities33,34.

To bridge these gaps, we strategically selected 20 well-known river-estuary systems spanning all Köppen-Geiger climate zones from tropical rainforest climate to tundra climate35. Using Projections under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways 5 (SSP5) with Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) 8.5 scenario, the annual exceedance frequency analyses of FF and HTF were conducted using 99th percentile thresholds. A probabilistic framework to quantify the compound occurrence likelihood of FF and HTF was developed, integrating both temporal dependence via copula models and spatial overlap analysis across deltaic floodplains. Our ensemble analysis demonstrates significant intensification of compound flood hazards during 1950-2015, which reveals accelerated intensification through 2050, showing higher compound event frequency compared to the historical baseline. A coupled hydrodynamic modeling framework was developed, integrating a 1D kinematic wave model for upstream flood routing, a 1D dynamic model for tide-forced simulation in estuarine reaches, and a 2D inundation model for floodplain dynamics. It is important to note that this framework specifically isolates the impacts of climate-driven variability (i.e., extreme precipitation and eustatic sea-level rise); consequently, localized land subsidence is not explicitly incorporated into the modeling simulations to maintain a focus on the inherent hydrological sensitivity to climate forcing. By comparing the inundation intensity and extent caused by FF, HTF, and their compound events, we conducted a detailed analysis of the increase in flood-affected areas due to CF compared to single hazards. Our findings serve as a crucial warning about the potentially severe flooding impacts of CF in the context of future scenarios of rising sea tide levels and frequent extreme rainfall, with significant implications for disaster prevention and mitigation strategies.

Results

High-tide flood occurrence and severity

This study analyzes trends in annual maximum water levels across global estuary regions using a reanalysis of the total sea water level (SWL) dataset spanning 1950–2024. The dataset incorporates pure tidal signals, storm surges, and changes in annual mean sea level. Results reveal a mean increasing trend of 0.85 mm yr⁻¹ across 817 major estuaries worldwide, with the highest rate reaching 10.79 mm yr⁻¹ (Fig. 1a). Among 20 major river basins examined, 19 exhibited statistically significant upward trends (p < 0.05, Fig. 1b). The rate of increase varied substantially spatially, ranging from the lowest in the Murray-Darling Basin (Australia; 0.91 mm yr⁻¹, p = 0.0293) to the highest in the Lena Basin (Russia; 5.01 mm yr⁻¹, p < 0.0001). Notably, the Mackenzie Basin (Canada) showed a significant rise of 3.04 mm yr⁻¹ (p < 0.0001), while the Yukon Basin (USA/Canada) exhibited a significant increase (1.50 mm yr⁻¹, p = 0.0061), albeit with a wide confidence interval (−10.40 to 13.40 mm yr⁻¹). Major river basins including the Mississippi (USA; 2.41 mm yr⁻¹, p < 0.0001), Nile (Egypt; 1.42 mm yr⁻¹, p < 0.0001), Ganges (India/Bangladesh; 1.38 mm yr⁻¹, p < 0.0001), and Amazon (Brazil/Peru; 1.30 mm yr⁻¹, p < 0.0001) all displayed significant upward trends. The St. Lawrence Basin (Canada) was the sole exception, showing a non-significant declining trend (-0.12 mm yr⁻¹, p = 0.6404). The exceptionally large confidence interval (approximately ±1.3×10³ mm yr⁻¹) associated with this estimate underscores the high uncertainty in this region. The explanatory power (R²) of the linear regression models for annual maximum water level changes differed markedly among basins, ranging from 0.003 (St. Lawrence) to 0.590 (Orinoco Basin, Venezuela).

a Spatial distribution of sea-level rise trends (mm/year) across global coastal stations. The inset histogram displays the probability density of the trend distribution. The 20 major river-estuary systems (marked with their respective names and IDs 1–20) were selected based on the ranking of highest annual runoff volume and drainage basin area. The specific estuarine locations were defined by identifying the terminal grid point of the river flow and matching it to the nearest coastal grid point with valid sea-level data. b Historical time series of annual mean sea levels for the 20 selected major estuaries from 1950 to 2024. The red dashed line represents the linear trend. Note: The numbering corresponds to the basin IDs (1–20). The statistical significance of the trends is indicated in the top-left corner of each panel: an upward arrow followed by an asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant increasing trend (\(p\)<0.05), whereas “ns” denotes a non-significant trend (\(p\)>0.05).

A comprehensive analysis of HTF trends (defined here as the annual count of days exceeding the 99th percentile threshold of historical sea surface levels36,37,38) across 20 major global river basins reveals a clear and concerning picture of how extreme sea level event frequencies are evolving across different timeframes (historical period, reanalysis data, and the high-emission scenario SSP5-8.5; Fig. 2). The CMIP6 model data used are listed in Table S1, while historical and future thresholds for the 99th percentiles are provided in Table S2. The analysis not only demonstrates a widespread intensification of these events but also highlights significant disparities in risk exposure across different geographical regions and climate zones. An examination of historical and reanalysis data indicates a pattern of moderate yet pervasive increase in HTF frequency across the vast majority of basins. The trend values are predominantly clustered around 1.0 day per year, with relatively narrow uncertainty ranges. This suggests a subtle but detectable rise in extreme water level days in the past observational record, providing initial evidence of the impacts of climate change. For instance, tropical basins such as the Amazon, Congo, and Nile, as well as temperate basins like the Danube, Ganges, and Yangtze, all exhibited historical trends fluctuating slightly around this baseline frequency. Reanalysis data largely corroborate this pattern of a gradual ascent, although data for certain basins (e.g., Nile, Orinoco) show higher trend values and greater uncertainties, hinting at an earlier emergence of a stronger warming signal or higher data variability in these regions39.

a Map showing the spatial distribution and drainage areas (km²) of the 20 major river basins analyzed. River mouths are marked with orange icons. b Time series of annual high-tide flooding (HTF) frequency (%) for each basin from 1950 to 2050. Black lines indicate historical simulations (1950–2014), and purple dashed lines represent reanalysis data (1950–2024). Red lines depict future projections under the SSP5-8.5 scenario (2015–2050). Shaded areas denote the uncertainty range (standard deviation). The HTF threshold is defined as the >99th percentile of the 1950–2014 historical baseline for SSP5-8.5 projections, and the >99th percentile of the self-consistent 1950–2024 baseline for reanalysis data.

In stark contrast, projections under the high-emission SSP5-8.5 scenario depict a dramatically different and far more severe outlook40,41. The increasing trend in HTF frequency is projected to accelerate explosively, with disparities between basins becoming vastly more pronounced. The analysis reveals a distinct geographical pattern in extreme risk. Tropical basins emerge as global hotspots of heightened sensitivity to warming. The Amazon (20.3 days/year), Congo (20.9 days/year), and Niger (22.5 days/year) basins all exhibit trends exceeding 20 days per year, while the Nile (32.7 days/year) and Orinoco (44.3 days/year) basins show staggering increases of over 30 days per year. This implies that in these regions, the frequency of such events is transitioning from episodic to a near-permanent state. Such a shift poses a devastating threat to ecosystems, agricultural productivity, and public health.

This scenario stands in sharp relief against the projected trends for high-latitude and some mid-latitude basins, where the rate of increase, while present, is substantially lower. Basins near the Arctic Circle, such as the Lena, Mackenzie, and Yukon, show trends of only 2.7 to 3.2 days per year. Similarly, basins including the Murray-Darling, Rhine, and Yellow River are generally projected to experience increases of less than 3.0 days per year, indicating a comparatively lower sensitivity to rising HTF frequency. A middle tier of basins, including the Mekong (4.6 days/year), Mississippi (5.9 days/year), Salween (8.8 days/year), Danube (11.1 days/year), and Pearl River (12.1 days/year), demonstrates a moderate yet still substantial increase. The absolute increments in these populous and economically critical regions already signify a future of escalating hydro-climatic stress. Furthermore, the uncertainty ranges associated with the trend values provide critical context. Under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, basins with the highest trend values, such as the Orinoco (±26.8 days/year), typically also exhibit larger uncertainty ranges. This reflects greater divergence among climate models in simulating the feedback mechanisms for the most vulnerable regions under extreme forcing. Crucially, however, all basins without exception show a strong positive trend, indicating with high confidence that the increase in HTF frequency is an unequivocal global phenomenon. It is also noteworthy that for some basins, like the Ganges (trend: 3.0 days/year; uncertainty: ±1.7 days/year), the uncertainty range is proportionally large relative to the trend itself, warranting cautious interpretation of the precise rate of change.

In summary, the HTF trends across these 20 basins collectively outline a clear trajectory of escalating global extreme sea level risk. The transition from a faint signal in the historical record to a projected dramatic intensification under a high-emission future, particularly the extreme climatic fate facing tropical regions, underscores the critical urgency of implementing robust global mitigation efforts aligned with the Paris Agreement goals42. Simultaneously, the stark heterogeneity in regional responses demands the development of tailored adaptation strategies to enhance resilience against HTF in the most vulnerable areas, thereby mitigating the potentially catastrophic impacts on human societies and natural systems.

Trends in fluvial flood intensity-frequency

Employing a kinematic wave hydrodynamic model forced by ERA5 reanalysis total runoff data43, we generate global-scale daily river discharge simulations at 0.1° resolution to quantify estuarine basin FF intensity changes. This is achieved through grid-scale flood simulations establishing basin-averaged areal rainfall as a primary driver, via correlation analyses with simulated flood characteristics (peak discharge, frequency, duration). The daily model performance was evaluated using the Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) metric44, which compares simulated streamflow discharge with observed data from hydrological stations (Fig. 3). Observed hydrological station data were obtained from Global Runoff Data Centre (GRDC)45, United States Geological Survey (USGS)46, and Chinese local hydrologic stations. A total of 11,495 stations exhibited a KGE index above 0, with 6392 stations surpassing 0.2, and 3123 stations reaching above 0.4, 783 stations hitting above 0.6, and 49 stations achieving a KGE index greater than 0.8.

The map illustrates the spatial distribution of model performance across global hydrological stations using the Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) metric. The color and size of the dots correspond to the KGE score, where darker red and larger dots indicate higher agreement (KGE > 0.6) between simulated and observed discharge, while lighter yellow dots represent lower performance. The blue lines depict the global river network.

To rigorously evaluate the model’s hydrological performance, we focused our analysis on the 20 major global estuarine basins previously identified (Fig. 2). For locations within these basins, we further analyzed simulations at stations demonstrating optimal basin area matching closest to estuaries (Fig. 3, Table 1, Fig. S1). The results across these 20 major estuarine basins reveal strong discharge replication capability, with a median KGE of 0.743 and a mean correlation coefficient (CC) of 0.813. The Mekong Basin achieves optimal performance (KGE = 0.904, CC = 0.939), followed by the Saint Lawrence (KGE = 0.833, CC = 0.852) and Yukon (KGE = 0.818, CC = 0.849). Notably, 19 basins (95%) exceed KGE > 0.45, while 13 basins (65%) maintain KGE > 0.70, confirming robust discharge pattern capture.

To transparently communicate the reliability of our projections, we stratified these basins into three distinct confidence levels based on KGE thresholds: High Confidence (KGE > 0.7), Moderate Confidence (0.45 < KGE ≤ 0.7), and Low Confidence (KGE ≤ 0.45) (Table 1). While high historical performance increases the credibility of projections, capturing trend directions is a vital indicator of a model’s sensitivity to future climate forcing, even when absolute performance is moderate. Performance differentiation emerges in sediment-dominated or heavily regulated systems; for instance, the Yellow River basin exhibits the lowest metrics (KGE = 0.339). However, the Correlation Coefficient (CC) for the Yellow River reaches 0.764 (Table 1), significantly higher than its KGE. This discrepancy indicates that while the model successfully captures the temporal variability and climatic timing of flood pulses (reflected in high CC), the absolute discharge volume is heavily dampened by anthropogenic regulation, such as reservoir impoundment and irrigation withdrawals (affecting KGE). In such “Low Confidence” basins, our simulations emphasize the naturalized hydrological response to climate forcing, providing a baseline of potential climate impacts isolated from intense anthropogenic interventions.

This study employs high-resolution (0.1°) gridded diagnostics to unravel complex spatiotemporal shifts in extreme flood regimes (annual maximum streamflow) across 20 major global river basins, analyzing 450,000 valid grid cells over the 1955–2024 period. To strictly control for false discovery rates inherent in spatial data, we applied the Field Significance testing procedure47, replacing the standard local threshold with a dynamically adjusted critical value (\({p}_{{critical}}\)=0.000948).

Figure 4 visualizes the global heterogeneity of annual maximum streamflow changes between the historical baseline (1955–1989) and recent decades (1990–2024). While raw intensity changes reveal broad spatial patterns, our rigorous field significance analysis (Figure S2) confirms that robust hydrological shifts are highly localized. Approximately 1.91% of global grids exhibit field-significant increasing trends (\(p\)<\({p}_{{critical}}\)), a signal that is physically distinguishable from internal climate variability. As detailed in Table S3, these robust intensification signals are predominantly clustered in specific hotspot basins, most notably the Orinoco (where 15.0% of grids show significant increases), Niger (5.4%), Amazon (4.5%), and Mississippi (4.1%). In these regions, the pronounced intensification is driven by synoptic-scale atmospheric circulation shifts and land-cover feedbacks, which work in tandem to amplify flood hazards48,49. Such a shift represents a critical transition in hydrological regimes, particularly threatening the densely populated floodplains within these basins. Conversely, statistically significant decreasing trends were negligible at the global scale, suggesting that widespread declines identified in raw trend analyses may largely be artifacts of statistical noise. Critically, the application of FDR confirms that climate change impacts manifest through intensely regionalized, statistically robust hydrological signatures rather than uniform global responses. The identified hotspots in low-latitude estuaries represent areas where flood intensification poses acute threats to densely populated floodplains.

a Global distribution of the percentage change in mean annual maximum discharge, calculated as the relative difference between the recent period (1990–2024) and the historical baseline (1955–1990). Red shading indicates an increasing trend in flood peak magnitude (wetting), while blue shading denotes a decreasing trend (drying). The map highlights the spatial heterogeneity of hydrological shifts at the global scale. b Detailed spatial patterns of streamflow changes across 20 major river basins. The visualization reveals intra-basin variability in flood-generating processes. Yellow stars mark the locations of river estuaries, serving as the interface for the upstream-downstream coupling analysis.

We further observe that within the identified hotspots, flood intensification is not randomly distributed but physically concentrated along major hydrological conveyances. As shown in the basin-scale diagnostics (Fig. 4b), the Orinoco and Mississippi basins display alarming amplification in their central arteries, directly implicating enhanced flood risks for riverside communities. In contrast, basins previously thought to be waning, such as the Yellow River, exhibit no field-significant trends under the rigorous FDR framework, suggesting that perceived desiccation may be statistically indistinguishable from natural variability. Consequently, adaptation strategies must be highly targeted: prioritizing strategic flood-proofing for amplifying systems (e.g., reinforced levees in the Orinoco), while avoiding over-engineering in basins where clear climate change signals have not yet emerged.

This study employs 15 models from the CMIP6 to analyze trends in basin-averaged precipitation, with detailed descriptions of the models provided in Table S4. Based on prior research, the seven-day cumulative basin-averaged areal rainfall (Rx7day) was selected to characterize the intensity of synoptic-scale meteorological forcing that drives flood hazards50,51,52,53,54. While hydraulic response times vary across basin scales, this standardized metric effectively captures the climatic flood potential driven by atmospheric intensification55,56,57,58,59. Its robustness as a hazard proxy was further validated against physically routed runoff simulations (see Figs. S9, S10), which confirmed consistent trends across the majority of basins. We defined FF days as those with 7-day cumulative areal precipitation exceeding the 99th percentile from 1950 to 2015. A global 0.1° gridded analysis of changes in flood intensity at the 99th percentile, derived from ERA5 runoff data, indicates that flood intensity increased over 37% of the global land area, while it decreased across 59.6% of the grid cells. Pronounced increases are observed in the Mississippi River Basin in North America, as well as in the Amazon and Orinoco River Basins in South America. In contrast, regions across Africa and Asia generally exhibited a decrease in 99th flood intensity. Further comparison of flood intensity changes between the latter period (1990–2024) and the earlier period (1955–1989) (Fig. S3), and an assessment of changes at the estuaries of 20 major river basins, reveal that tropical basins (such as the Amazon, Orinoco, Congo, Mekong, and Niger) experienced significant increases in flood intensity. In mid- to high-latitude regions, however, the trends were more heterogeneous: for example, the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers showed less evident upward trends, while the Mississippi River exhibited a substantial increase in intensity. These findings highlight the pronounced spatial heterogeneity in global flood intensity changes and underscore the necessity to account for regional variability when assessing compound flood risks under changing climatic conditions. Stratifying analysis by basin size (Small, Medium-Small, Medium-Large, Large; Figure S4) reveals pronounced upward trends in extreme flood events across minor basins from 1950–2024, with 99th percentile floods exhibiting the most significant intensification in small catchments—contrasting with negligible trends in large basins. Critically, lower-reach sections of the 819 studied basins demonstrate accelerating flood frequencies, culminating in a 2024 extremum event that necessitates heightened vigilance toward evolving lower-basin hydrological hazards. Furthermore, our analysis of downstream sections across all basins, stratified by multiple percentile thresholds (from the 80th to the 99.99th percentile; Fig. S5), reveals a consistent increase in flood frequency from 1950 to 2024. This indicates a pervasive and growing flood risk in downstream basins globally, which urgently demands enhanced monitoring and proactive adaptation strategies to mitigate escalating impacts on vulnerable communities and infrastructure.

Analysis of the annual trend in maximum 7-day accumulative areal precipitation (Rx7day) values based on the SSP5-8.5 scenarios (Fig. S6) reveals an upward trend in the multi-model ensemble (MME) of Rx7day for nearly all basins, implying an increase in the intensity of FF in the future. Among them, the Chao Phraya, Ganges, Mekong, Pearl, and Salween River basins exhibit the most pronounced growth trends, with linear \(k\) slopes of increase reaching 94.55%, 68.23%, 54.33%, 85.25%, and 86.62%, respectively, under the SSP585 scenario. The disasters caused by FF may reach unprecedented severity, necessitating vigilance against the occurrence of large-scale floods in these basins. The extended analysis of historical and projected Rx7day evolution under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios (1950–2050) is shown in Fig. S6, which supports intensifying fluvial flood risks in future projections.

To further analyze the trends in flood occurrence frequency across the 20 river basins, we use the 99th percentile of the Rx7day statistical indicator from the historical period of 1950–2014 as the flood threshold. This threshold is then used to analyze the number of flood days on a daily basis from 1950 to 2050, with a primary focus on the trends under the SSP585 scenario. Examining the trend in the number of flood days per basin from 1950 to 2050 (Fig. 5), we can see that there is an increasing trend in historical flood days for almost all basins between 1950 and 2015, except for the Yangtze and Murray Darling basins60. The Niger basin has exhibited the highest increase in flood days, with a linear trend coefficient (\(k\)) of 8.23%. Looking at the future period from 2015 to 2050, based on the MME analysis under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, all basins are projected to experience a significant increase in the number of flood days annually. The Niger basin remains the most severely affected, with a \(k\) of 24.66%, and its estuary region is projected to face the threat of FF for more than 10 days annually in the future, highlighting the urgency of addressing this hazard. The Congo River basin is projected to experience the highest number of flood days, demonstrating a \(k\) value of 31.95% in the future. By 2050, it is anticipated that the Congo River basin will face approximately 20 days of FF annually, which is twice the historical average.

Time series display the annual frequency of FF days simulated by 15 CMIP6 models under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. FF days are defined as days where the 7-day accumulated areal precipitation exceeds the historical (1950–2014) 99th percentile threshold. The solid lines represent the Multi-Model Ensemble (MME) mean for the historical period (1950–2014, black) and the future period (2015–2050, red). The shaded regions (gray for historical, pink for future) indicate the uncertainty range (model spread). The dashed vertical line marks the transition year (2015) between historical simulations and future projections. Inset numbers denote the linear trends for the respective periods, with asterisks (*) indicating statistical significance (\(p\) < 0.01).

Compound flood risk driven by SLR

A granular analysis of the 20 river basins (Fig. 6) revealed an unexpected temporal shift in flood dominance: the frequency of HTF is projected to exceed that of FF post-2050. For example, the Orinoco, the Nile, and the Mississippi are particularly exposed to HTF. Across the study basins, the average growth rate of HTF frequency is 273.6%, while FF only increases by an average of 10.6%. As the number of days with HTF is projected to rise, the risk of compound disasters, where FF and HTF events occur together, will also increase, posing significant challenges for coastal resilience and adaptation strategies.

The map illustrates the linear increasing trends in flood frequency across 20 major global river basins. Blue shading represents the trend magnitude of FF within each basin, with darker shades indicating a more rapid increase. Pink/Purple circles at river mouths denote the trend magnitude of HTF, where circle size and color intensity are proportional to the rate of increase. Numerical annotations adjacent to each basin display the specific trend values, formatted as “FF trend / HTF trend”. The comparison highlights a global pattern where HTF intensification rates generally exceed those of FF, particularly in tropical and sub-tropical estuaries (e.g., Orinoco, Mississippi).

Assessing compound flood hazards requires identifying temporal overlaps between FF and HTF. In our study, we initially treat FF and HTF as two separate events. The probability of these events occurring at the same time can be calculated by multiplying the individual occurrence probabilities of both events (Fig. 7). To empirically validate this independence assumption, we conducted a lag correlation analysis (0–7 days) using Kendall’s \(\tau\) rank correlation coefficient across all 20 basins (Table S5, Fig. S7). The results verify that for the majority of basins (e.g., Mississippi, Rhine, Yellow), the dependence between drivers is either statistically insignificant or negligible (|\(\tau\)| < 0.05), confirming the validity of the independence assumption. For basins exhibiting weak negative correlations (e.g., Mekong, \(\tau\)=-0.10), this approach yields a conservative estimate of joint risk. In the few basins with moderate positive correlations (e.g., Ganges, \(\tau\)= 0.29), the independence assumption represents a conservative lower bound for compound flood probability.

Where: \(p\left({cf}\right)=p\left({ff}\right)\times p\left({htf}\right)\). \(p\left({cf}\right)\): daily joint probability of concurrent FF and HTF events. \(p\left({ff}\right)\): daily FF probability (FF days/365). \(p\left({htf}\right)\): daily HTF probability (HTF days/365). The numbers in black and red denote the multi-model ensemble (MME) mean \(p\left({cf}\right)\) for the historical and future periods, respectively. The asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant trend (e.g., \(p\) < 0.05).

From 1950 to 2015, the probability of CF was relatively low in all 20 basins, never exceeding one in a thousand. However, during the future period from 2015 to 2050, our analysis identifies that all these basins exhibit significantly increased annual CF frequencies, with tropical and subtropical systems particularly vulnerable. Seven major river basins (the Amazon, Orinoco, Congo, Niger, Nile, Danube, and Mississippi) have exhibited daily joint probabilities \(p\left({cf}\right)\) exceeding 1% under future scenarios, which is double than historical period. According to the SSP585 scenario, these basins will experience at least 150 high-tidal days in 2050, significantly increasing the likelihood of concurrent basin-scale and high-tidal floods. Projected CF probabilities exhibit a positive acceleration in trend magnitude (Δk̄ = 2.068% yr⁻¹, p < 0.01) during 2015–2050 compared to historical baselines (Δk̄ = 0.035% yr⁻¹, 1950–2015), suggesting nonlinear intensification of flood synchronization mechanisms. The impact of CF cannot be underestimated, and our findings emphasize the urgent need for comprehensive flood risk management strategies that consider the interconnected nature of flood hazards and the evolving threat posed by climate change.

High-resolution mechanistic modeling of compound flooding

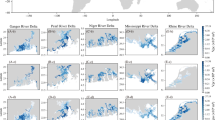

The preceding sections have delineated the increasing likelihood of CF across 20 global river basins. This section delves deeper into the hydrological impacts associated with compound events where FF and HTF coexist. To quantitatively compare the impacts of CF across various estuary regions, this study employs the 99th percentile thresholds for both HTF and FF within each estuary as benchmarks. We delineated the estuarine zones within the 20 basins (Fig. S8a) for inundation mapping, with the Pearl River basin selected as the representative case for mechanistic analysis. By utilizing the 99th percentile SWL at estuary grid points and the validated 99th percentile FF data from hydrological stations (depicted in Fig. S8b), we simulate the different scenarios within the Pearl River basin’s estuary. Our findings reveal that, under the 99th percentile disaster scenario, the inclusion of each additional factor in the model results in significant increases in both the flood inundation area and depth.

The combined effects of fluvial-tidal interactions significantly amplify flood hazards. Isolated FF induces substantial inundation (Fig. 8a), while incorporating the 99th percentile downstream SWL elevates flood extent by 24.6% due to the backwater effect. Estuarine tidal forcing further exacerbates upstream water stage fluctuations, extending hydrodynamic impacts along river corridors, which causes HTF in coastal regions (Fig. 8b). Under CF scenarios, the inundated area expands by 54% compared to FF-only events (Fig. 8c), demonstrating the imperative of coupled FF-HTF modeling for hazard assessment. Considering the inherent uncertainty in hydraulic parameters (e.g., Manning’s roughness), sensitivity analysis suggests an inundation extent variation of approximately ±15% for this deltaic region, confirming the robustness of the amplification trend. Therefore, when simulating complex flood disasters, it is crucial to comprehensively consider both FF and HTF, as well as their internal interaction mechanisms, in order to accurately predict future flood hazards. Neglecting any of these factors can significantly underestimate the severity of the disaster.

a–c High-resolution inundation maps of the Pearl River Estuary (representative deltaic system) under 99th percentile extreme scenarios. The panels illustrate inundation patterns driven by: a Fluvial Flooding (FF) only; b High-tide Flooding (HTF) only; and c Compound Flooding (CF), where fluvial and tidal forces interact. The blue color gradient indicates inundation depth (mm). d Global comparison of flood exposure across 20 major river basins. The bar chart quantifies the percentage of inundated estuarine grid cells under isolated (FF, HTF) versus compound (CF) scenarios. Light blue, medium blue, and pink bars represent FF, HTF, and CF, respectively. Error bars indicate the uncertainty range associated with hydraulic roughness sensitivity, varying from 5% to 18% based on specific basin topography.

To better understand the impact of CF compared to single FF or single HTF, we used numerical simulation to create a flood inundation map with a spatial resolution of 0.1° and 90 meters worldwide. Utilizing the aforementioned methodology applied to the Pearl River basin, we calculated the inundation extents for individual FF, individual HTF, and their combined CF scenarios for each designated area (Fig. 8d). In general, CF exacerbates the intensity of fluvial flooding, resulting in greater inundation extents and depths along river channels, thereby intensifying the severity of associated disasters. Across the twenty basins, an average increase of 28.6% was simulated in the CF scenario. To account for hydrodynamic uncertainties, we applied topography-dependent error margins ranging from 5% in bedrock-confined channels (e.g., Salween) to 18% in flat deltaic regions (e.g., Amazon), as depicted by the error bars in Fig. 8d. Although FF typically results in more extensive inundation areas than HTF, the frequency of HTF events is projected to surpass that of FF in the future. Given the substantial impact of HTF on amplifying FF, continued emphasis should be placed on monitoring and understanding the evolving coastal flood risks associated with SLR.

Discussion

Previous studies on flood disasters caused by SLR have mainly focused on simulating coastal flooding scenarios and assessing risks associated with a single HTF61. These studies have consistently found that the probability of future HTF events will continue to increase, resulting in more severe impacts. However, these studies have lacked comprehensive evaluations and rigorous analytical frameworks for examining extreme compound disasters10. Additionally, the influence of tidal backwater on fluvial flooding has not been adequately integrated into hydrodynamic simulations of CF disasters30,31. Our findings, consistent with prior research, clearly demonstrate that excluding the inherent amplification mechanism of estuarine tides on fluvial flooding in compound flood assessments leads to a considerable underestimation of flood severity. To provide deeper insights, we conducted an extensive study across the 20 river-estuary regions. Our results show that in areas experiencing significant SLR and an increased frequency of consecutive high-tide days at mid-to-low latitudes (such as the Orinoco, Niger, Mississippi, and other estuarine regions), the likelihood of compound major flood disasters will continue to escalate in the future. Specifically, our findings reveal that the amplification effect of high sea level on FF has increased from the historical average at the 99th percentile. Furthermore, upstream regions situated farther from the estuary will also be adversely affected by fluvial flooding exacerbated by the backwater effect resulting from SLR. These findings highlight the urgent need for comprehensive risk assessments and the development of effective mitigation strategies to address the imminent threats posed by CF.

Notably, our analysis reveals divergent fluvial flood trajectories across basin scales. While large basins show minimal FF intensification (83.9% of global grids exhibited no significant trend), small catchments display alarming acceleration in 99th percentile floods—particularly vulnerable tropical systems like the Niger (flood days +8.23% historically, projected +24.66% under SSP5-8.5). This scale-dependent response is compounded by pronounced downstream amplification: lower-basin flood frequency escalation culminated in 2024’s record extremum. These findings highlight the critical vulnerability of small-to-medium coastal basins, where SLR synergizes with intensified runoff to generate catastrophic compound impacts62,63. Global estuaries face accelerating coastal flood exposure due to synergistic amplification of sea-level rise (SLR) and tidal dynamics, with 95% (19/20) of major systems exhibiting statistically significant increases in annual maximum water levels (1950–2024), ranging from polar amplification-driven surges (Lena Basin: 5.01 mm/yr) to moderate tropical rises (Amazon: 1.30 mm/yr). Under SSP5-8.5, HTF frequency intensifies nonlinearly against SLR: 25% of studied estuaries will exceed 150 annual flood days by 2050, led by the Orinoco (300 days) and Mississippi (250 days), where shallow bathymetry and dense populations compound risks. Concurrently, extreme water levels escalate disproportionately, with the 99.99th percentile SWL rising 24.3% globally (2015–2050 vs. 1950–2015), confirming the heightened severity of CF events. Spatial heterogeneity—from Arctic SLR hotspots to low-predictability systems like the St. Lawrence (R² = 0.003)—underscores region-specific vulnerabilities demanding urgent adaptive interventions.

In summary, CF events in the estuarine areas of river basins involve the combined effects of upstream FF and downstream HTF. To better understand the trends of these compound events and predict their frequency and impacts under future climate change, there is a need to further strengthen the quantitative and detailed description of the interactions between these disasters64. This study analyzed the occurrence frequency and intensity of FF and HTF over a century from 1950 to 2050, revealing the increasing probability of CF. Moreover, due to the continuous SLR, the frequency of HTF events is expected to increase in the future65. Ultimately, in low- and middle-latitude basins where SLR is pronounced, HTF may become the dominant cause of future flood disasters, leading to persistent and continuous flood events in coastal regions. This, in turn, will increase the likelihood of CF occurrences.

High-resolution numerical simulations were used to enhance the quantitative description of the amplification effect of HTF on FF in CF, while also distinguishing the impact ranges of both types of floods on estuarine areas of river basins. This paper emphasizes that understanding the internal influence mechanism between FF and HTF is essential for model establishment and future flood prediction, providing important methodological support for risk assessment and flood control strategy formulation in estuarine areas of river basins under climate change. Global SLR exacerbates the likelihood of the simultaneous occurrence of river floods and coastal HTF66. When such floods do occur, they can cause unprecedented disaster losses. In future coastal flood control and disaster mitigation projects, it is necessary to further consider the multiple and complex impacts brought about by HTF.

While this study provides a comprehensive global assessment, several methodological constraints warrant interpretation. First, regarding the statistical framework, we assumed occurrence independence between drivers. Although our verification (Fig. S1) supports this for most basins, the independence-based approach likely provides a conservative lower-bound estimate for regions with positive dependence (e.g., Ganges, Yangtze). Second, regarding the hydrological definition, we transitioned to direct runoff simulations (CMIP6) to capture land-surface processes. However, this characterizes the naturalized response to climate forcing. By fixing flood thresholds to a historical baseline, we isolate the climate signal but do not account for non-stationarity driven by anthropogenic interference (e.g., dam regulation, land-use change). Therefore, our results represent the relative intensification of climate-driven flood potential rather than managed flow conditions. Third, global-scale hydrodynamic modeling necessitates spatiotemporal simplifications. The use of a daily temporal resolution and the omission of certain near-shore processes (e.g., wave setup) may underestimate the intensity of short-lived, transient compound events, although the physical backwater effect remains explicitly resolved. Finally, our projections assume a static estuarine morphology. We acknowledge that sediment transport, anthropogenic sand mining, and land subsidence can significantly alter channel bathymetry and inundation depth. However, given the high uncertainty in predicting future human sediment management globally, adopting a static DEM serves as a necessary first-order approximation to attribute trends to clear climatic signals (sea-level rise and runoff intensification) rather than speculative geomorphic scenarios. Future research should prioritize high-resolution coupling of dynamic morphology and sub-daily forcing to refine local adaptation strategies.

To rigorously evaluate the representativeness of the precipitation-based flood proxy (Rx7day) used in our global screening, we performed a comparative analysis using physically routed discharge simulations from 13 CMIP6 models (Fig. S9 for flood frequency and Figure S10 for flood intensity). The results reveal a strong consistency across the majority of high-latitude and monsoon-dominated basins, such as the Yukon, Ganges, and Mississippi. In these regions, the intensification of meteorological precipitation translates linearly into increased flood discharge, confirming that Rx7day serves as a robust indicator of climatic flood potential. However, a significant hydrological divergence is observed in the Amazon basin. While meteorological indices suggest an intensification of wet extremes, our hydrodynamic ensemble projects a distinct decrease in flood intensity (−8.21% under SSP5-8.5) and a substantial reduction in flood frequency (−92.04% under SSP5-8.5). Similar attenuation patterns are also visible in the Orinoco (flood frequency −26.61%) and Danube (flood frequency −24.71%) basins. This discrepancy highlights the nonlinear modulation of catchment hydrology: in massive tropical and evaporation-sensitive basins, the enhanced evaporative demand driven by warming temperatures can offset precipitation gains, leading to a “drying” hydrological response despite “wetter” atmospheric forcing. Therefore, while Rx7day effectively characterizes the meteorological drivers of compound hazards, our integration of hydrodynamic modeling provides a critical correction that captures the hydrological attenuation in evaporation-dominated basins, ensuring a more comprehensive assessment of future risks.

Methods

Historical flood simulations

The reliability of our flood modeling hinges on multi-scale hydrological integration. At the continental scale, MERIT-HYDRO datasets67 provide foundational terrain parameters (Digital Elevation Model, DEM) with 90 m resolution, while the (Dominant River Tracing-Routing) DRT upscaling algorithm synthesizes these with river morphology data to generate 0.1° hydrological grids68. River network topology follows the Strahler Order classification. Hydrological forcing data were derived from ERA5-Land reanalysis (1950-2024), with hourly runoff fields temporally upscaled to daily frequencies for simulation purposes. The global-scale flood model employs a kinematic wave approximation to solve the coupled continuity-momentum equations69,70,71,72, ultimately yielding global flood maps at a daily temporal scale and a spatial resolution of 0.1°. These synoptic-scale outputs provide essential boundary conditions for nested high-resolution estuarine models. In the estuary coastal zones, high-resolution estuarine flood modeling employs MERIT-HYDRO’s 90 m topographic data as the hydrodynamic baseline, with river centerlines automatically extracted through a width-threshold algorithm. Spatial matching and coupling between scales are critical for model initialization. To perform the precise spatial matching, we explicitly align the main channel grid points of the 90 m estuarine domain with the corresponding main channel grid points of the upstream 0.1° network. We extract the simulated discharge time series from these specific 0.1° main channel grids and impose it as the upstream inflow boundary condition (\({Q}_{{inflow}}\)) for the 90 m hydrodynamic model. Whereas the downstream boundary conditions utilize tidal level data. Within the 90 m domain, a one-dimensional dynamic wave method derived from the Saint-Venant equations is adopted to reconstruct the flood process in the main river segments with high resolution. This approach explicitly accounts for both the upstream basin-wide flood dynamics and the downstream backwater effects induced by high SWL. Furthermore, a 2D inundation model is incorporated to simulate the inundation diffusion of river grids subjected to elevated water levels73, ultimately producing the final inundation process of the estuary river channels with a spatial resolution of 90 meters.

During the simulation, we used the total runoff from the ERA5-Land reanalysis as the input for surface runoff generation. Through the kinematic wave model, we simulated the flood distribution with a global resolution of 0.1°. The Saint-Venant equations are formulated as follows:

where \(Q\) (m3/s) is the streamflow flow discharge; \(A\) (m2) is the area of flow section; \(q\)(m2/s) is the lateral inflow. \({S}_{f}\) is the friction slope; \(g\) (m/s2) is the gravitational acceleration; and \(H\) (m) is the water depth. Kinematic wave method is used following assumption:

The following equation is derived from the momentum and continuity principles embedded in Eqs. (3)-(6):

where lateral inflow \({q}_{m}^{t}\) and \({q}_{m}^{t-1}\) is input from ERA5-Land total runoff data. \({Q}_{m-1}^{t}\) means the inflow discharge from upstream grids at \(t\) time step.

The one-dimensional dynamic wave approach is implemented to simulate tidal-river interactions at basin outlets, solving the Saint-Venant equations (Eqs. (1) and (2): continuity and momentum conservation) through a tridiagonal matrix system using the Thomas algorithm. This numerical scheme computes concurrent water depth and discharge profiles along the channel network, requiring: (1) initialized discharge-water depth relationships; (2) upstream boundary conditions: Time-varying inflow hydrographs; (3) downstream boundary conditions: Sea water level from tidal stage. Both initial discharges and upstream inflows are derived from 0.1°-resolution gridded runoff products, spatially aggregated to river network nodes through inverse-distance weighting (see Data Availability Statement).

The two-dimensional surface inundation algorithm incorporates the flooding algorithm introduced by Chen et al. (2022) for the redistribution of surface water depths, employing the seeded region growing technique. The initialization of the water depth field for the two-dimensional river network is achieved through the assignment of river network depths with a resolution of 0.1 degrees. Meanwhile, the water depths in tidal river sections are determined through dynamic wave calculations and then assigned accordingly.

The downscaling method: (1) The spatial matching between the global 0.1° grid and the local 90 m hydrodynamic domain is implemented through a unidirectional hydrological-hydrodynamic coupling (Fig. 9). At the 0.1° scale, the model focuses on broad-scale runoff generation and routing across the entire basin. For this, we employ a kinematic wave approximation, which simplifies the St. Venant equations by assuming the friction slope (\({s}_{f}\)) is equal to the bed slope (\({s}_{0}\)).

Left: At the 0.1° scale, basin-wide runoff is routed using the Kinematic Wave approximation based on ERA5 forcing and the DRT river network, driven primarily by gravity. Center: A spatial matching procedure explicitly aligns the 0.1° main channel with the 90 m domain inlet, transferring the simulated discharge \(Q\left(t\right)\) as the upstream boundary condition. Right: At the 90 m scale, the model transitions to the full Dynamic Wave (Shallow Water Equations) formulation. This allows for the explicit resolution of complex water level gradients and tidal backwater effects (Tidal Interactions) using high-resolution topography, which are neglected in the kinematic wave approximation.

(2) To perform the precise spatial matching, we explicitly align the main channel grid points of the 90 m estuarine domain with the corresponding main channel grid points of the upstream 0.1° network. We extract the simulated discharge time series from these specific 0.1° main channel grids and impose it as the upstream inflow boundary condition (\({Q}_{{inflow}}\)) for the 90 m hydrodynamic model. Within the 90 m domain, we transition from the kinematic wave to a full Dynamic Wave (or diffusive wave) formulation to resolve the complex water level gradients. The model solves the shallow water equations:

This ensures that the upstream flow is accurately handed over to the high-resolution main river stem, allowing the model to physically capture the non-linear interactions between fluvial discharge and tidal boundaries (\({H}_{{tide}}\)).

(3) Regarding the mitigation of parametric uncertainty amplification, our justification rests on the disparity in data availability across scales. While high-resolution topographic data (DEM) from MERIT Hydro is highly reliable at 90 m, hydrological parameters such as soil hydraulic conductivity are generally only validated at coarser resolutions (~10 km). Attempting to run a fully distributed hydrological model at 90 m would necessitate interpolating these sparse parameters, leading to massive equifinality. By maintaining runoff generation at the 0.1° scale (where land-surface data is robust) and reserving the 90 m scale strictly for hydrodynamic routing (where topography is the dominant driver), we leverage the accuracy of the DEM without introducing unconstrained parameter uncertainty.

The hydrological station data employed in this study for historical validation include sources such as the Global Runoff Data Centre (GRDC), the United States Geological Survey (USGS), runoff data from Hunan Province’s Hydrological Public Service Map, stations provided by the Hubei Hydrology and Water Resources Center, and publicly accessible station data from the Pearl River Water Resources Bureau. The dataset comprises a total of 33,793 stations, with 26,762 stations possessing time series spanning more than a year. These station data were matched with model results based on latitude and longitude for assessment and comparison. The KGE index served as the metric to evaluate the fidelity of the model simulations. We assumed an error tolerance confined within one grid point, and a nine-grid validation framework was implemented, where each station’s host grid and its eight contiguous neighbors underwent KGE evaluation. The optimal KGE value from this 3 × 3 grid matrix was assigned to the station through spatial optimization, yielding a spatially optimized validation dataset. The statistical metrics were computed as:

Pearson correlation coefficient:

Kling-Gupta Efficiency:

where \({x}_{i}\) is observed runoff at time step \(i\) (mm/day)\({y}_{i}\): Simulated runoff at time step \(i\) (mm/day). \(\bar{x}\) and \(\bar{y}\) mean values of observed and simulated series. \({\sigma }_{s}\) and \({\sigma }_{o}\) mean standard deviations of simulated and observed data.

Future flood simulation and assessment

The assessment of future fluvial floods primarily relies on daily precipitation data as the foundational input. This involves calculating the average areal rainfall for each basin and utilizing Rx7day as an indicator to evaluate the occurrence of basin-wide floods. We adopted SSP5-8.5 as benchmarks to assess future flood occurrences. The 15 precipitation datasets from CMIP6 include ACCESS-CM2, CESM2, CMCC-CM2-SR5, CMCC-ESM2, EC-Earth3-CC, EC-Earth3-Veg-LR, FGOALS-g3, GFDL-ESM4, INM-CM4-8, INM-CM5-0, and IPSL-CM6A-LR (see Table S4 for detailed information). Due to variations in resolution, these models were uniformly resampled to a spatial resolution of 1° using bilinear interpolation. To rigorously assess hydrological responses beyond meteorological proxies, we additionally utilized daily total runoff outputs from a subset of 13 CMIP6 models (detailed in Table S6) to simulate physical river discharge. Using the kinematic wave routing scheme, we generated daily streamflow series and extracted discharge data specifically at the river mouths (estuaries) of the 20 basins to quantify future trends in runoff magnitude under both SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

The historical analysis utilizes two primary baseline datasets with specific temporal constraints: the ERA5-Land reanalysis provides a continuous historical record from 1950 to 2024, facilitating long-term trend assessment. In contrast, for climate-driven projections, the CMIP6 historical baseline is standardized to 1950–2014, as the historical experimental protocol officially transitions to future SSP scenarios in 2015. This slight variation in timeframes is necessary to leverage the most recent reanalysis observations while maintaining alignment with standardized CMIP6 modeling protocols.

The SWL data along coastal regions primarily generated from Deltares Global Tide and Surge Model (GTSM) version 3.0, using CMIP6 model results under SSP5-8.5, encompassing five models: CMCC-CM2-VHR4, EC-Earth3P-HR, GFDL-CM4C192-SST, HadGEM3-GC31-HM, and HadGEM3-GC31-HM-SST74. These models simulate the uplift effect of tides on river channels based on hourly water level data and consider high-resolution HTF scenarios. Similar to the hydrological datasets, the temporal coverage of SWL data varies by source: the CMIP6-driven GTSM historical simulations are constrained to the 1950–2014 window, while the ERA5 reanalysis for SWL extends to 2024 to provide a more comprehensive historical record of coastal extremes. All baseline comparisons and frequency analyses have been adjusted to ensure temporal consistency within their respective modeling chains.

Assumptions of the CF simulation

The analysis and numerical simulations conducted in this study are based on the following assumptions:

(1) Fluvial floods are operationally defined by areal precipitation exceeding the 99th percentile threshold derived from 1950–2015 basin observations.

(2) High-tide flooding onset corresponds to estuarine water levels surpassing the 99th percentile of 1950–2015 tidal records.

(3) Vertical datum alignment ensures consistency between the tidal reference plane and DEM baseline elevations.

(4) Hydraulic connectivity couples each river mouth to its nearest oceanic tidal node, with the latter’s stage defining the downstream hydraulic boundary.

(5) The 2D inundation algorithm assumes daily temporal resolution is sufficient to propagate channel floods to the maximum hydraulically connected extent.

Simulation of FF, HTF, and CF

In this study, floods are primarily classified into three categories based on their causes:

-

(1)

FF, which primarily describes floods resulting from intense rainfall within a river basin. These floods are driven by the accumulation of precipitation in upstream areas, leading to overflow and subsequent inundation downstream.

-

(2)

HTF, which mainly pertains to the coastal flooding caused by the rise in sea levels at river mouths. This type of flooding occurs when ocean tides reach exceptionally high levels, causing water to spill over into adjacent low-lying areas and coastal regions.

-

(3)

CF, which represents a complex interaction between the above two types of flooding in river mouth regions. In compound flooding scenarios, river-fluvial floods are exacerbated by the presence of high tides. The combined effects of riverine runoff and tidal surge can result in more extensive and severe inundation than would occur from either factor alone.

The simulation methods for these three types of floods vary slightly. For pure FF simulations, the kinematic wave approach is predominantly used globally, without considering downstream backwater effects or tidal backwater influence. The MERIT-HYDRO hydrological dataset, upscaled using the DRT method to a spatial resolution of 0.1°, along with ERA5 runoff and daily runoff data from CMIP6, are used to simulate river routing flow in the kinematic wave form, yielding global FF results at a spatial resolution of 0.1°. In HTF simulations, the MERIT-HYDRO DEM data with a spatial resolution of 90 meters is used as the baseline, and sea level data from ERA5 and CMIP6 at estuaries are used as input. The coastline and sea level grid points are matched and assigned values, and the inertia wave method is employed to simulate high-resolution coastal inundation scenarios. For CF simulations, the DEM with a resolution of 90 meters is also used as the baseline. The upstream boundary condition is the kinematic wave runoff at a resolution of 0.1°, serving as the state input. The downstream boundary condition is the sea level grid point, serving as the input. The dynamic wave backwater effect is simulated for major river segments.

Dependence analysis of drivers

To empirically verify the independence assumption between FF and HTF, we conducted a lag correlation analysis across all 20 study basins using the reanalysis dataset (1950–2024). We employed Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient (\(\tau\)) to assess the temporal dependence between daily river discharge and daily sea level75,76,77. Considering the hydrological response time of large basins, we tested time lags ranging from 0 to 7 days and identified the maximum correlation for each basin. The analysis reveals that for the majority of basins (e.g., Mississippi, Rhine, Yellow), the dependence is statistically insignificant (\(p\) > 0.05) or negligible (\(\tau\) < 0.05), validating the independence assumption. In basins exhibiting weak negative correlations (e.g., Mekong), the independence assumption yields a conservative estimate of joint probability. For the few basins with moderate positive correlations (e.g., Ganges, Yangtze), the independence assumption represents a conservative lower bound of the compound risk. Detailed statistical results are provided in Table S5 and Fig. S7.

It is critical to distinguish between occurrence independence and impact independence in our modeling framework. The probability calculation \(p\left({cf}\right)=p\left({ff}\right)\times p\left({htf}\right)\) assumes occurrence independence, which refers to the statistical likelihood of extreme discharge and high sea levels coinciding in time. While we simplify this statistical coupling (verified as valid or conservative for most basins), our methodology explicitly accounts for impact dependence through hydrodynamic modeling. By dynamically coupling river boundaries with tidal-surge boundaries, our hydrodynamic model (integrating kinematic and dynamic wave solvers) captures the physical interactions—specifically the backwater effect—where high sea levels impede river drainage and non-linearly amplify flood levels.

Multi-scale flood simulation

We initiated global 0.1°-resolution kinematic wave runoff simulations validated against basin-scale observational discharge. Subsequently, we established spatial topological connectivity between 0.1° and 90-m resolution river networks, dynamically downscaling hydrologically verified 0.1° discharges to 90-m mainstem grids through drainage-area weighting to eliminate redundant upstream computations. For estuarine zones, full 90-m resolution topological networks spanning headwaters to river mouths were extracted for local flood modeling, while mainstem channels retained 0.1° resolution where appropriate - an approach that optimizes computational efficiency while preserving basin integrity. This multi-resolution strategy intentionally mitigates parametric uncertainty amplification inherent in hyper-resolution large-basin modeling where subsurface characteristics are poorly constrained, while simultaneously meeting high-precision requirements for vulnerable coastal regions. During 90-m model construction, Strahler stream orders were derived from MERIT hydrography flow-direction data. Basin completeness was verified via upstream tracing from each estuary cell: systems reaching source grids (Strahler order = 1) within the domain were classified as complete, while truncated basins incorporated boundary inflows scaled from 0.1° discharge data using catchment-area matching. ERA5-Land total runoff (0.1° resolution) provided hydrological forcing, downscaled to 90-m grids via nearest-neighbor sampling. Estuarine inundation was simulated using dynamic wave routing incorporating tidal backwater effects, with sea-level boundaries at river mouths derived from CMIP6 scenarios.

Statistical analysis and trend quantification

To quantify the changes in flood frequency, we calculated the percentage increase (\(R\)) using the formula\(R\) = (\({\bar{F}}_{{future}}-{\bar{F}}_{{base}{line}})/{\bar{F}}_{{base}{line}}\), where \(\bar{F}\) denotes the multi-year average frequency for the baseline (1950–2014) and future (2015–2050) periods. The aggregate percentage increases reported (e.g., for HTF and FF) represent the arithmetic mean of the individual percentage changes across the 20 study basins. For the multi-model ensemble, we applied an equal-weight approach to the 5CMIP6 models. Statistical significance of the projected changes was assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (\(p\) < 0.01), while historical trend significance was evaluated using the Modified Mann-Kendall test to account for temporal autocorrelation in the hydrological time series.

Data availability

The hourly CMIP6 sea water level dataset, ERA5-Land dataset are available on the Climate Data Store: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/. The CMIP6 precipitation and runoff datasets are available at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. The observed records of global stream flow are obtained from GRDC (http://www.bafg.de/GRDC), USGS (https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/), Hunan Province’s Hydrological Public Service Map (http://yzt.hnswkcj.com:9090/#/), Yangtze River Hydrological Website (http://www.cjh.com.cn/sqindex.html), and Water Information Website of the Hydrology Bureau of the Pearl River Water Resources Commission (https://zjhy.mot.gov.cn/zhuhangsj/shuiqingxx/). The MERIT Hydro datasets can be downloaded from the website: http://hydro.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~yamadai/MERIT_Hydro/. The code used as the basis for this study is available at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18264563.

References

Schaeffer, M., Hare, W., Rahmstorf, S. & Vermeer, M. Long-term sea-level rise implied by 1.5 C and 2 C warming levels. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 867–870 (2012).

Kopp, R. E. et al. Communicating future sea-level rise uncertainty and ambiguity to assessment users. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 648–660 (2023).

Hermans, T. H. et al. The timing of decreasing coastal flood protection due to sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 359–366 (2023).

Fang, J. et al. Benefits of subsidence control for coastal flooding in China. Nat. Commun. 13, 6946 (2022).

Gori, A., Lin, N., Xi, D. & Emanuel, K. Tropical cyclone climatology change greatly exacerbates US extreme rainfall–surge hazard. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 171–178 (2022).

Ganguli, P. & Merz, B. Extreme coastal water levels exacerbate fluvial flood hazards in Northwestern Europe. Sci. Rep. -UK 9, 13165 (2019).

Blanchet, C. L. et al. Climatic pacing of extreme Nile floods during the North African Humid Period. Nat. Geosci. 17, 638–644 (2024).

Shan, X. et al. Dynamic flood adaptation pathways for Shanghai under deep uncertainty. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 21 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Compound coastal flooding in San Francisco Bay under climate change. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 3 (2025).

Dahm, R. Flood resilience a must for delta cities. Nature 516, 329–329 (2014).

Talke, S. A. How tidal properties influence the future duration of coastal flooding. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 36 (2025).

Ali, J. et al. Multivariate compound events drive historical floods and associated losses along the US East and Gulf coasts. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 19 (2025).

Banfi, F. & De Michele, C. Compound flood hazard at Lake Como, Italy, is driven by temporal clustering of rainfall events. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 234 (2022).

Qiu, J., Liu, B., Yang, F., Wang, X. & He, X. Quantitative stress test of compound coastal-fluvial floods in China’s Pearl River Delta. Earth’s. Future 10, e2021EF002638 (2022).

Wu, W., Westra, S. & Leonard, M. Estimating the probability of compound floods in estuarine regions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 2821–2841 (2021).

Lai, Y., Li, J., Gu, X., Liu, C. & Chen, Y. D. Global compound floods from precipitation and storm surge: Hazards and the roles of cyclones. J. Clim. 34, 8319–8339 (2021).

Edmonds, D. A., Caldwell, R. L., Brondizio, E. S. & Siani, S. M. Coastal flooding will disproportionately impact people on river deltas. Nat. Commun. 11, 4741 (2020).

Adshead, D. et al. Climate threats to coastal infrastructure and sustainable development outcomes. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 344–352 (2024).

Try, S. et al. Comparison of CMIP5 and CMIP6 GCM performance for flood projections in the Mekong River Basin. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 40, 101035 (2022).

Alaminie, A. A. et al. Nested hydrological modeling for flood prediction using CMIP6 inputs around Lake Tana, Ethiopia. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 46, 101343 (2023).

Fischer, S. & Schumann, A. Multivariate flood frequency analysis in large river basins considering tributary impacts and flood types. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR029029 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Reconciling disagreement on global river flood changes in a warming climate. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1160–1167 (2022).

Blöschl, G. Three hypotheses on changing river flood hazards. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 5015–5033 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. Rising rainfall intensity induces spatially divergent hydrological changes within a large river basin. Nat. Commun. 15, 823 (2024).

Sangsefidi, Y., Bagheri, K., Davani, H. & Merrifield, M. Data analysis and integrated modeling of compound flooding impacts on coastal drainage infrastructure under a changing climate. J. Hydrol. 616, 128823 (2023).

Zhong, M. et al. A study on compound flood prediction and inundation simulation under future scenarios in a coastal city. J. Hydrol. 628, 130475 (2024).

Salam, A., Mohamed, M. & Hezam, I. M. Inundations and climatic fluctuations: prospects, difficulties, and recommendations. Clim. Change Rep. 1, 30–47 (2024).

Grimley, L. E., Hollinger Beatty, K. E., Sebastian, A., Bunya, S. & Lackmann, G. M. Climate change exacerbates compound flooding from recent tropical cyclones. npj Nat. Hazards 1, 45 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Exploring the driving factors of compound flood severity in coastal cities: a comprehensive analytical approach. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2024, 1–34 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. Characterizing future changes in compound flood risk by capturing the dependence between rainfall and river flow: An application to the Yangtze River Basin, China. J. Hydrol. 635, 131175 (2024).

Sarhadi, A. et al. Climate change contributions to increasing compound flooding risk in New York City. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 105, E337–E356 (2024).

Wu, G., Liu, Q., Xu, H. & Wang, J. Modelling the combined impact of sea level rise, land subsidence, and tropical cyclones in compound flooding of coastal cities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 252, 107107 (2024).

Hague, B. S. & Talke, S. A. The influence of future changes in tidal range, storm surge, and mean sea level on the emergence of chronic flooding. Earth’s. Future 12, e2023EF003993 (2024).

Jiang, S., Tarasova, L., Yu, G. & Zscheischler, J. Compounding effects in flood drivers challenge estimates of extreme river floods. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl4005 (2024).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 5, 180214 (2018).

Thompson, P. R. et al. Rapid increases and extreme months in projections of United States high-tide flooding. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 584–590 (2021).

Yin, J. et al. Large increase in global storm runoff extremes driven by climate and anthropogenic changes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4389 (2018).

Yin, J. et al. Does the hook structure constrain future flood intensification under anthropogenic climate warming? Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR028491 (2021).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Riahi, K. et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Development policy affects coastal flood exposure in China more than sea-level rise.Nat Clim. Change 15, 1071–1077 (2025).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Gupta, H. V., Kling, H., Yilmaz, K. K. & Martinez, G. F. Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: Implications for improving hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 377, 80–91 (2009).

GRDC (Global Runoff Data Centre): GRDC. The Global Runoff Data Centre, 56068 Koblenz, Germany. https://www.bafg.de/GRDC/ (2023).

USGS (United States Geological Survey): USGS. National Water Information System data available on the World Wide Web (USGS Water Data for the Nation). https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis (2023).

Wilks, D. The stippling shows statistically significant grid points: how research results are routinely overstated and overinterpreted, and what to do about it. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 2263–2273 (2016).

Sorribas, M. V. et al. Projections of climate change effects on discharge of the Amazon River at the outlet. J. Hydrol. 538, 143–158 (2016).

Wang, S. Y. S. et al. The 2013 floods in the Central U.S. through the lens of changing atmospheric ridges. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–14 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Indices for monitoring changes in extremes based on daily temperature and precipitation data. WIREs Clim. Change 2, 851–870 (2011).

Donat, M. G. et al. More extreme precipitation in the world’s dry and wet regions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 508–513 (2016).

Risser, M. D. & Wehner, M. F. Attributable human-induced changes in the likelihood and magnitude of the observed extreme precipitation during Hurricane Harvey. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 12,457–12,464 (2017).

Zscheischler, J. et al. Future projection of compound precipitation and wind speed extremes in Europe. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 3173–3189 (2021).

Boansi, D., Tambo, J. A. & Müller, M. Intra-seasonal risk of agriculturally-relevant weather extremes in West African Sudan Savanna. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 135, 355–373 (2019).

Westra, S., Alexander, L. V. & Zwiers, F. W. Global increasing trends in annual maximum daily precipitation. J. Clim. 26, 3904–3918 (2013).

Asadieh, B. & Krakauer, N. Y. Global trends in extreme precipitation: climate models versus observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 877–891 (2015).

Nanding, N. et al. Anthropogenic influences on 2019 July precipitation extremes over the mid–lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Front. Environ. Sci. 8, 603061 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Spatio-temporal changes in daily extreme precipitation for the Lancang–Mekong River Basin. Nat. Hazards 119, 1–21 (2023).

Chaparinia, F. et al. Evaluation of climate indices related to water resources in Iran over the past 3 decades. Sci. Rep. 15, 1 (2025).

Zheng, H. et al. Projections of future streamflow for Australia informed by CMIP6 and previous generations of global climate models. J. Hydrol. 636, 131286 (2024).

Bosserelle, A. L., Morgan, L. K. & Hughes, M. W. Groundwater rise and associated flooding in coastal settlements due to sea-level rise: a review of processes and methods. Earth’s. Future 10, e2021EF002580 (2022).

Yin, J. et al. Flash floods: why are more of them devastating the world’s driest regions? Nature 615, 212–215 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Education can improve response to flash floods. Science 377, 1391–1392 (2022).

Long, Z.-Y. & Duan, H.-F. Human mobility amplifies compound flood risks in coastal urban areas under climate change. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 413 (2025).

Mahmoudi, S., Moftakhari, H., Muñoz, D. F., Sweet, W. & Moradkhani, H. Establishing flood thresholds for sea level rise impact communication. Nat. Commun. 15, 4251 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Synchronization of global peak river discharge since the 1980s. Clim. Change 15, 1084–1090 (2025).

Yamazaki, D. et al. MERIT Hydro: A high-resolution global hydrography map based on latest topography dataset. Water Resour. Res. 55, 5053–5073 (2019).

Wu, H., Kimball, J. S., Mantua, N. & Stanford, J. Automated upscaling of river networks for macroscale hydrological modeling. Water Resour. Res. 47, W03517 (2011).

Veitzer, S. A. & Gupta, V. K. Statistical self-similarity of width function maxima with implications to floods. Adv. Water Resour. 24, 955–965 (2001).

Horritt, M. & Bates, P. Predicting floodplain inundation: raster-based modelling versus the finite-element approach. Hydrol. Process. 15, 825–842 (2001).

Bates, P. D. et al. Combined modeling of US fluvial, pluvial, and coastal flood hazard under current and future climates. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR028673 (2021).

Wu, H. et al. Real-time global flood estimation using satellite-based precipitation and a coupled land surface and routing model. Water Resour. Res. 50, 2693–2717 (2014).

Chen, W. et al. A coupled river basin-urban hydrological model (DRIVE-Urban) for real-time urban flood modeling. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR031709 (2022).

Copernicus Climate Change Service. Global sea level change time series from 1950 to 2050 derived from reanalysis and high resolution CMIP6 climate projections. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) (2022).

Wahl, T., Jain, S., Bender, J., Meyers, S. D. & Luther, M. E. Increasing risk of compound flooding from storm surge and rainfall for major US cities. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1093–1097 (2015).

Moftakhari, H. R., Salvadori, G., AghaKouchak, A., Sanders, B. F. & Matthew, R. A. Compounding effects of sea level rise and fluvial flooding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 9785–9790 (2017).

Bevacqua, E., Maraun, D., Hobæk Haff, I., Widmann, M. & Vrac, M. Multivariate statistical modelling of compound events via pair-copula constructions: analysis of floods in Ravenna (Italy). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 2701–2723 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the publicly available data from MERIT-Hydro, HydroSHEDS, and the Climate Data Store that enabled the flood simulations, and we thank the CMIP6 modeling groups, ESGF, and their funding agencies for the climate data. Funding: This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Basic Public Welfare Project (Grant no. LZJWZ24E090001), the Open Fund of the Key Laboratory of Cities’ Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change in Shanghai (2025) (Grant no. CMACCOF202513), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant no. 2025M783323).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.C. conceived the study, conducted data computation and analysis, created visualizations, and wrote the primary manuscript. Y.Zheng assisted in data analysis and manuscript review. Y.Zhou and T.Z. contributed to the core research concept and provided a critical review of the manuscript. Y.Zhang, D.Z.Z., and X.Zhou offered critical revisions and substantive feedback. L.Z. collected the precipitation data. X. Zhang analyzed the data. Z.H. provided the geographic information dataset. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author