Abstract

There has been a growing interest in non-Hermitian quantum mechanics. The key concepts of quantum mechanics are quantum fluctuations. Quantum fluctuations of quantum fields confined in a finite-size system induce the zero-point energy shift. This quantum phenomenon, the Casimir effect, is one of the most striking phenomena of quantum mechanics in the sense that there are no classical analogs and has been attracting much attention beyond the hierarchy of energy scales, ranging from elementary particle physics to condensed matter physics, together with photonics. However, the non-Hermitian extension of the Casimir effect and the application to spintronics have not yet been investigated enough, although exploring energy sources and developing energy-efficient nanodevices are its central issues. Here we fill this gap. By developing a magnonic analog of the Casimir effect into non-Hermitian systems, we show that this non-Hermitian Casimir effect of magnons is enhanced as the Gilbert damping constant (i.e., the energy dissipation rate) increases. When the damping constant exceeds a critical value, the non-Hermitian Casimir effect of magnons exhibits an oscillating behavior, including a beating one, as a function of the film thickness and is characterized by the exceptional point. Our result suggests that energy dissipation serves as a key ingredient of Casimir engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, non-Hermitian quantum mechanics has been drawing considerable attention1. The important concepts of quantum mechanics are quantum fluctuations. Quantum fluctuations of quantum fields under spatial boundary conditions realize a zero-point energy shift. This quantum effect which arises from the zero-point energy, the Casimir effect2,3,4,5, is one of the most striking phenomena of quantum mechanics in the sense that there are no classical analogs. Although the original platform for the Casimir effect2,3,4,5 is the photon field (See ref. 6, as an example, for an oscillating behavior of the Casimir effect of photons as a function of distance between two uncharged plates, where chiral material inserted between the two parallel plates plays a key role.), the concept can be extended to various fields such as scalar, tensor, and spinor fields7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Thanks to this universal property, the Casimir effects have been investigated in various research areas (As an example, see refs. 16,17,18,19,20,21,22 for Casimir effects in magnets and ref. 23 for a magnonic analog of the thermal Casimir effect in a Hermitian system. For details of the distinction between the thermal Casimir effect and the Casimir effect, refer to Supplemental Material. See also ref. 24 for an analog of the dynamical Casimir effect with magnon excitations in a spinor Bose–Einstein condensate.) beyond the hierarchy of energy scales7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, ranging from elementary particle physics to condensed matter physics, together with photonics. However, the non-Hermitian extension of the Casimir effect and the application to spintronics remain missing ingredients, although exploring energy sources and developing the potential for energy-efficient nanodevices are the central issues of spintronics25,26,27,28,29.

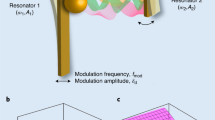

Here we fill this gap. The Casimir effects are characterized by the energy dispersion relation. We therefore incorporate the effect of energy dissipation on spins into the energy dispersion relation of magnons through the Gilbert damping constant30 and thus develop a magnonic analog of the Casimir effect31, called the magnonic Casimir effect (see Fig. 1) (In ref. 31, we investigated the Casimir effect induced by quantum fields for magnons (i.e., a magnonic analog of the Casimir effect) and referred to it as the magnonic Casimir effect. See ref. 31 for details of the magnonic Casimir effect in dissipationless systems.), into non-Hermitian systems. We then show that this non-Hermitian extension of the magnonic Casimir effect, which we call the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect, is enhanced as the Gilbert damping constant increases. When the damping constant exceeds a critical value, the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect exhibits an oscillating behavior as a function of the film thickness and is characterized by the exceptional point32 (EP). We refer to this behavior as the magnonic EP-induced Casimir oscillation. We emphasize that this magnonic EP-induced Casimir oscillation is absent in the dissipationless system of magnons. The magnonic EP-induced Casimir oscillation exhibits a beating behavior in the antiferromagnets (AFMs) where the degeneracy between two kinds of magnons is lifted. Our result suggests that energy dissipation serves as a new handle on Casimir engineering33 to control and manipulate the Casimir effect of magnons. Thus, we pave the way for magnonic Casimir engineering through the utilization of energy dissipation.

Results

System

We consider the insulating AFMs of two-sublattice systems in three dimensions described by the Hamiltonian,

where \({{{{\bf{S}}}}}_{i}=({S}_{i}^{x},{S}_{i}^{y},{S}_{i}^{z})\) is the spin operator at the site i, J > 0 parametrizes the antiferromagnetic exchange interaction between the nearest-neighbor spins 〈i, j〉, Kh > 0 is the hard-axis anisotropy, and Ke > 0 is the easy-axis anisotropy. These are generally Kh/J ≪ 1 and Ke/J ≪ 1. The AFMs have the Néel magnetic order and there exists the zero-point energy34,35. Throughout this study, we work under the assumption that the Néel phase remains stable in the presence of energy dissipation. Elementary magnetic excitations are two kinds of magnons σ = ±, acoustic mode for σ = + and optical mode for σ = −.

By incorporating the effect of energy dissipation on spins into the energy dispersion relation of magnons through the two-coupled Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation where the value of the Gilbert damping constant α > 0 for each sublattice is identical to each other, we study the low-energy magnon dynamics36 described by the energy dispersion relation \({\epsilon }_{\sigma ,{{{\bf{k}}}},\alpha }\in {\mathbb{C}}\) of Re(ϵσ,k,α) ≥ 0 and the wavenumber \({{{\bf{k}}}}=({k}_{x},{k}_{y},{k}_{z})\in {\mathbb{R}}\) (As an example, ref. 37 assumes \({\epsilon }_{\sigma ,{{{\bf{k}}}},\alpha }\in {\mathbb{R}}\) and \({{{\bf{k}}}}\in {\mathbb{C}}\), which describes a spatially-decaying solution38.) in the long wavelength limit as37

and

where k ≔ ∣k∣, the length of a magnetic unit cell is a, the spin moment in a magnetic unit cell is S, and the others are material-dependent parameters which are independent of the wavenumber, \(0 \,<\, {A}_{\sigma ,\alpha }\in {\mathbb{R}}\), \(0\, < \,{\delta }_{\sigma }\in {\mathbb{R}}\), \(0 \,< \,{{{{\mathcal{D}}}}}_{\sigma }\in {\mathbb{R}}\), and \(0 \,<\, C\in {\mathbb{R}}\): The parameters are given as37

In the absence of the hard-axis anisotropy Kh = 0, two kinds of magnons σ = ± are in degenerate states, whereas the degeneracy is lifted by Kh > 0. Note that, in general, the effect of dipolar interactions is negligibly small in AFMs, and we neglect it throughout this study.

The Gilbert damping constant α is a dimensionless constant, and the energy dissipation rate increases as the Gilbert damping constant grows. In the dissipationless system31, the Gilbert damping constant is zero α = 0. The dissipative system of α > 0 described by Eq. (2) can be regarded as a non-Hermitian system for magnons in the sense that the energy dispersion takes a complex value. Note that the constant term in Eq. (2), −iαC, is independent of the wavenumber and just shifts the purely imaginary part of the magnon energy dispersion ϵσ,k,α. For this reason [also see Eq. (10a)], the constant term, −iαC, is not relevant to the magnonic Casimir effect. We then define the magnon energy gap of Eq. (2) as Δσ,α ≔ Re(ϵσ,k=0,α), i.e.,

Magnonic exceptional point

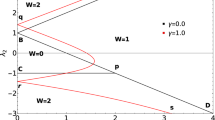

When the damping constant α is small and \({({E}_{\sigma ,k = 0,\alpha })}^{2}\, > \,0\), Eσ,k=0,α takes a real value and decreases as α increases. This results in

Thus, the magnon energy gap decreases as the damping constant increases39 [compare the solid line with the dashed one in the left panel of Fig. 2(i)]. When the damping constant is large enough, the magnon energy gap vanishes Δσ,α = 0 at \(\alpha ={\alpha }_{\sigma }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\),

where there exists the gapless magnon mode which behaves like a relativistic particle with the linear energy dispersion. From the property of Eq. (6), we call (i) \(\alpha \le {\alpha }_{\sigma }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\) the gap-melting regime.

When the damping constant exceeds the critical value \({\alpha }_{\sigma }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), i.e., \(\alpha \,> \,{\alpha }_{\sigma }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), Eσ,k=0,α takes a purely imaginary value as \({({E}_{\sigma ,k = 0,\alpha })}^{2}\, < \,0\). In this regime, the real part of the magnon energy dispersion remains zero Re(ϵσ,k,α) = 0 for the region \(0\le k\le {k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\),

whereas Re(ϵσ,k,α) > 0 for \(k \,> \,{k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\) [see the highlighted in yellow in the left panel of Fig. 2(ii) and (iii)]. The critical point \({k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\) can be regarded as the EP39 for the wavenumber k, and we refer to it as the magnonic EP. As the value of the damping constant becomes larger, that of the EP increases

At the EP \(k={k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), the group velocity vσ,k,α ≔ Re[∂ϵσ,k,α/(∂ℏk)] becomes discontinuous [see the solid lines in the left panel of Fig. 2(ii) and (iii)]. In the vicinity of the EP, the group velocity becomes much larger than usual such as in the gap-melting regime (i) [compare the solid lines in the left panel of Fig. 2(ii) and (iii) with the one of Fig. 2(i)].

Assuming \({\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\, < \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), the non-Hermitian system for magnons described by Eq. (2) of α > 0 can be divided into three regimes (i)-(iii) in terms of the magnonic EPs as follows [see the left panel of Fig. 2(i), (ii), and (iii)]:

-

(i)

\(\alpha \le {\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\, < \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\). No magnonic EPs.

-

(ii)

\({\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \,< \,\alpha\, < \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\). One EP, \({k}_{\sigma = +,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\).

-

(iii)

\({\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\, < \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\le \alpha\). Two EPs, \({k}_{\sigma = +,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\) and \({k}_{\sigma = -,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\).

Magnonic Casimir energy

The magnonic analog of the Casimir energy, called the magnonic Casimir energy31, is characterized by the energy dispersion relation of magnons. Therefore, by incorporating the effect of energy dissipation on spins into the energy dispersion relation of magnons through the Gilbert damping constant [Eq. (2)], a non-Hermitian extension of the magnonic Casimir effect can be developed. We remark that the Casimir energy induced by quantum fields on the lattice, such as the magnonic Casimir energy31, can be defined by using the lattice regularization40,41,42,43,44,45,46. In this study, we focus on thin films confined in the z direction (Fig. 1). In the two-sublattice systems, the wavenumber on the lattice is replaced as \({(a{k}_{j})}^{2}\to 2[1-\cos (a{k}_{j})]\) along the j axis for j = x, y, z. Here by taking into account the Brillouin zone (BZ), we set the boundary condition for the z direction in wavenumber space so that it is discretized as kz → πn/Lz, i.e., akz → πn/Nz, where Lz ≔ aNz is the film thickness, \({N}_{j}\in {\mathbb{N}}\) is the number of magnetic unit cells along the j axis, and n = 1, 2, . . . , 2Nz. Thus, the magnonic Casimir energy ECas31 per the number of magnetic unit cells on the surface for Nz is defined as the difference between the zero-point energy \({E}_{0}^{{{{\rm{sum}}}}}\) for the discrete energy ϵσ,k,α,n due to discrete kz [Eq. (10b)] and the one \({E}_{0}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}\) for the continuous energy ϵσ,k,α [Eqs. (10c) and (2)] as follows40,41,42,43,44,45,46:

where \({k}_{\perp }:= \sqrt{{{k}_{x}}^{2}+{{k}_{y}}^{2}}\), d2(ak⊥) = d(akx)d(aky), the integral is over the first BZ, and the factor 1/2 in Eqs. (10b) and (10c) arises from the zero-point energy of the scalar field.

We remark that36 assuming thin films of Nz ≪ Nx, Ny (Fig. 1), the zero-point energy in the thin film of the thickness Nz is \({E}_{0}^{{{{\rm{sum}}}}}({N}_{z}){N}_{x}{N}_{y}\) and consists of two parts as \({E}_{0}^{{{{\rm{sum}}}}}({N}_{z})={E}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}({N}_{z})+{E}_{0}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}({N}_{z})\) [Eq. (10a)], where \({E}_{0}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}({N}_{z})\) exhibits the behavior of \({E}_{0}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}({N}_{z})\propto {N}_{z}\) [Eq. (10c)]. Then, to see the film thickness dependence of ECas(Nz), we introduce the rescaled Casimir energy \({C}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}^{[b]}\) in terms of \({{N}_{z}}^{b}\) for \(b\in {\mathbb{R}}\) as

and call \({C}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}^{[b]}\) the magnonic Casimir coefficient in the sense that \({E}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}={C}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}^{[b]}{{N}_{z}}^{-b}\).

Note that the zero-point energy arises from quantum fluctuations and does exist even at zero temperature. The zero-point energy defined at zero temperature does not depend on the Bose-distribution function [Eqs. (10b) and (10c)]. Throughout this work, we focus on zero temperature36.

Magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect

Finally, we investigate the magnonic Casimir effect in the non-Hermitian system α > 0, which we call the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect, for each regime (i)–(iii). As an example, we consider NiO, an insulating AFM. From refs. 37,47,48, we roughly estimate the model parameter values for NiO as follows [Eq. (2)]: J = 47.1 meV, Kh = 0.039 5 meV, Ke = 0.001 72 meV, S = 1.21, and a = 0.417 nm. NiO is a biaxial AFM of Kh > 0 and Ke > 0. Due to the hard-axis anisotropy Kh > 0, the degeneracy between two kinds of magnons σ = ± is lifted in NiO. These parameters provide \({\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \sim 0.008\,54 \,< \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \sim 0.041\,9\). Figure 2 shows the magnon energy dispersion [Eq. (2)] and the magnonic Casimir energy [Eq. (10a)] with its Casimir coefficient [Eq. (11)] for each regime (i)-(iii).

Gap-melting regime

(i) Gap-melting regime \(\alpha \le {\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \,< \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\). The magnonic Casimir energy takes a real value as shown in the middle and right panels of Fig. 2(i), see also Eq. (11), and there are no magnonic EPs [see the left panel of Fig. 2(i)].

When \(\alpha\, < \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), the magnon energy gap for both σ = ± is nonzero Δσ=±,α > 0 and both magnons σ = ± are the gapped modes. For each gapped mode, the absolute value of the magnonic Casimir coefficient \({C}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}^{[3]}\) decreases and approaches asymptotically to zero as the film thickness increases. We emphasize that the magnon energy gap decreases as the damping constant α increases [Eq. (6)]. Then, the magnitude of the magnonic Casimir energy and its coefficient increase as the value of the damping constant becomes larger and approaches to the critical value \(\alpha \to {\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\) [see the middle panel of Fig. 2(i)].

When \(\alpha ={\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), the magnon σ = − remains the gapped mode, whereas the magnon energy gap for σ = + vanishes Δσ=+,α = 0 and the magnon σ = + becomes the gapless mode which behaves like a relativistic particle with the linear energy dispersion. In the gapless mode, the magnonic Casimir coefficient \({C}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}^{[3]}\) approaches asymptotically to a nonzero constant as the film thickness increases. The behavior of the gapless magnon mode is analogous to the conventional Casimir effect of a massless scalar field in continuous space49 except for a-dependent lattice effects, whereas that of the gapped magnon modes is similar to the Casimir effect known for massive degrees of freedom49,50.

Oscillating regime

(ii) Oscillating regime \({\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\, < \,\alpha\, < \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\). The magnonic Casimir energy takes a complex value as shown in the middle and right panels of Fig. 2(ii), see also Eq. (11). There is one EP, e.g., \(a{k}_{\sigma = +,\alpha = 0.04}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \sim 0.039\,1\) for α = 0.04 [see the left panel of Fig. 2(ii)]. Then, the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect exhibits an oscillating behavior as a function of Nz for the film thickness Lz ≔ aNz.

An intuitive explanation for the oscillation of the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect and its relation to the EP is given as follows: Through the lattice regularization, the magnonic Casimir energy is defined as the difference [Eq. (10a)] between the zero-point energy with the discrete wavenumber kz [Eq. (10b)] and the one with the continuous wavenumber [Eq. (10c)]. On the lattice, the wavenumber kz under the boundary condition is discretized in units of π/aNz as kz → (π/aNz)n. As the film thickness Nz increases, the unit becomes smaller, and finally, it matches the EP as \(\pi /a{N}_{z}={k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), i.e., \({N}_{z}=\pi /a{k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), where the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect is enhanced due to the EP. Then, the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect is periodically enhanced where the film thickness Nz is multiples of \(\pi /a{k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\). Thus, the oscillating behavior of the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect stems from the EP, \({k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), and the oscillation is characterized in units of \(\pi /a{k}_{\sigma ,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\). We refer to this oscillating behavior as the magnonic EP-induced Casimir oscillation. The period of this Casimir oscillation is

As an example, the period is \({\Lambda }_{\sigma = +,\alpha = 0.04}^{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}} \sim 80.4\) for α = 0.04. This agrees with the numerical result in the middle and right panels of Fig. 2(ii), see the highlighted in red. We call (ii) \({\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \,<\, \alpha \,< \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\) the oscillating regime. The middle and right panels of Fig. 2(ii) show that the magnonic EP-induced Casimir oscillation is characterized by its Casimir coefficient \({C}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}^{[b]}\) of b = 1.5.

Beating regime

(iii) Beating regime \({\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\, < \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\le \alpha\). The magnonic Casimir energy takes a complex value as shown in the middle and right panels of Fig. 2(iii), see also Eq. (11). There are two EPs, \({k}_{\sigma = +,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\) and \({k}_{\sigma = -,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\), which induce two types of the Casimir oscillations characterized by \({\Lambda }_{\sigma = +,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}\) and \({\Lambda }_{\sigma = -,\alpha }^{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}\), respectively. As an example, \(a{k}_{\sigma = +,\alpha = 0.05}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \sim 0.049\,2\) and \(a{k}_{\sigma = -,\alpha = 0.05}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \sim 0.027\,3\) provide \({\Lambda }_{\sigma = +,\alpha = 0.05}^{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}} \sim 63.8\) and \({\Lambda }_{\sigma = -,\alpha = 0.05}^{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}} \sim 115\), respectively, for α = 0.05 [see the left panel of Fig. 2(iii)]. Due to the interference between the two Casimir oscillations, the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect exhibits a beating behavior as a function of Nz for the film thickness Lz ≔ aNz with a period of

As an example, the period is \(| 1/{\Lambda }_{\sigma = +,\alpha = 0.05}^{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}-1/{\Lambda }_{\sigma = -,\alpha = 0.05}^{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}{| }^{-1} \sim 143\) for α = 0.05. This agrees with the numerical result in the middle and right panels of Fig. 2(iii), see the highlighted in blue. We call (iii) \({\alpha }_{\sigma = +}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}} \,< \,{\alpha }_{\sigma = -}^{{{{\rm{cri}}}}}\le \alpha\) the beating regime. The middle and right panels of Fig. 2(iii) show that the beating behavior of the magnonic EP-induced Casimir oscillation is characterized by its Casimir coefficient \({C}_{{{{\rm{Cas}}}}}^{[b]}\) of b = 1.5. We remark that the beating behavior is absent in the uniaxial AFMs of Kh = 0 and Ke > 0 where two kinds of magnons σ = ± are in degenerate states36.

Imaginary part of the Casimir energy

Here, we discuss the meaning of the imaginary part of the Casimir energy. The (complex) Casimir energy is defined by the zero-point energy, which is the sum of all the possible (complex) eigenvalues. The real part of the zero-point energy originates from the sum of the real parts of the eigenvalues, whereas the imaginary part of the zero-point energy is defined as the sum of imaginary parts of eigenvalues. Since the imaginary parts of eigenvalues are formally regarded as the decay width (or the inverse of a lifetime) of an unstable particle, the imaginary part of the zero-point energy is the sum of all the possible decay widths. Hence, if the decay width of an unstable particle depends on the wavenumber, and the width in the thin film and that in the bulk are different from each other, then the imaginary part of the Casimir energy can be nonzero. In this work, since we focus on magnons in the geometry of Fig. 1, the imaginary part of magnonic Casimir energy represents the Lz-dependence of the sum of magnon decay widths.

Discussion

Magnonic Casimir engineering

The Gilbert damping can be enhanced and controlled by the established experimental techniques of spintronics such as spin pumping36. In addition, microfabrication technology can control the film thickness and manipulate the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect. The Casimir pressure of magnons, which stems from the real part of its Casimir energy, contributes to the internal pressure of thin films. We find from the middle panel of Fig. 2(ii) and (iii) that depending on the film thickness, the sign of the real part of the magnonic Casimir coefficient changes. This means that by tuning the film thickness, we can control and manipulate the direction of the magnonic Casimir pressure as well as the magnitude thanks to the EP-induced Casimir oscillation. Thus, our study utilizing energy dissipation, the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect, provides the new principles of nanoscale devices, such as highly sensitive pressure sensors and magnon transistors51, and paves the way for magnonic Casimir engineering.

Conclusion

We have shown that as the Gilbert damping constant increases, the non-Hermitian Casimir effect of magnons in antiferromagnets is enhanced and exhibits the oscillating behavior which stems from the exceptional point. This exceptional point-induced Casimir oscillation also exhibits the beating behavior when the degeneracy between two kinds of magnons is lifted. These magnonic Casimir oscillations are absent in the dissipationless system of magnons. Thus, we have shown that energy dissipation serves as a new handle on Casimir engineering.

Outlook

In this paper, following ref. 37, the effect of dissipation is incorporated into the energy dispersion relation of magnons through the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation. It will be intriguing to find the quantum effect of dissipation on the magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect, beyond the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation, by using quantum master equation29,52,53,54. We also remark that dipolar interactions contribute to the form of the dispersion relation55 and play a crucial role in the magnonic Casimir effect in ferrimagnets31. Hence, taking dipolar interactions into account, it will be interesting to develop this study, magnonic non-Hermitian Casimir effect in antiferromagnets, into ferrimagnets. We leave these advanced studies for future works.

Methods

Numerical calculation was performed by using the software Wolfram Mathematica.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Ashida, Y., Gong, Z. & Ueda, M. Non-Hermitian physics. Adv. Phys. 69, 249–435 (2020).

Casimir, H. B. G. On the attraction between two perfectly conducting plates. Proc. Kon. Ned. Akad. Wetensch. 51, 793 (1948).

Lamoreaux, S. K. Demonstration of the Casimir force in the 0.6 to 6μm range. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 5–8 (1997).

Lamoreaux, S. K. Erratum: demonstration of the Casimir force in the 0.6 to 6 μm range. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5475 (1998).

Bressi, G., Carugno, G., Onofrio, R. & Ruoso, G. Measurement of the Casimir force between parallel metallic surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 041804 (2002).

Jiang, Q.-D. & Wilczek, F. Chiral Casimir forces: Repulsive, enhanced, tunable. Phys. Rev. B 99, 125403 (2019).

Milton, K. A. The Casimir effect: recent controversies and progress. J. Phys. A 37, R209–R277 (2004).

Plunien, G., Müller, B. & Greiner, W. The Casimir effect. Phys. Rep. 134, 87–193 (1986).

Mostepanenko, V. M. & Trunov, N. The Casimir effect and its applications. Phys. Uspekhi 31, 965 (1988).

Bordag, M., Mohideen, U. & Mostepanenko, V. M. New developments in the Casimir effect. Phys. Rep. 353, 1–205 (2001).

Klimchitskaya, G. L., Mohideen, U. & Mostepanenko, V. M. The Casimir force between real materials: Experiment and theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1827–1885 (2009).

Rodriguez, A. W., Capasso, F. & Johnson, S. G. The Casimir effect in microstructured geometries. Nat. Photonics 5, 211–221 (2011).

Chernodub, M. N., Goy, V. A., Molochkov, A. V. & Nguyen, H. H. Casimir effect in Yang-Mills theory in D = 2 + 1. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 191601 (2018).

Chernodub, M. N., Goy, V. A. & Molochkov, A. V. Phase structure of lattice Yang-Mills theory on \({{\mathbb{T}}}^{2}\times {{\mathbb{R}}}^{2}\). Phys. Rev. D 99, 074021 (2019).

Kitazawa, M., Mogliacci, S., Kolbé, I. & Horowitz, W. A. Anisotropic pressure induced by finite-size effects in SU(3) Yang-Mills theory. Phys. Rev. D 99, 094507 (2019).

Neuberger, H. & Ziman, T. Finite-size effects in Heisenberg antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 39, 2608–2618 (1989).

Hasenfratz, P. & Niedermayer, F. Finite size and temperature effects in the AF Heisenberg model. Z. Phys. B 92, 91–112 (1992).

Pryadko, L. P., Kivelson, S. & Hone, D. W. Instability of charge ordered states in doped antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5651–5654 (1998).

Du, Z. Z., Liu, H. M., Xie, Y. L., Wang, Q. H. & Liu, J.-M. Spin Casimir effect in noncollinear quantum antiferromagnets: Torque equilibrium spin wave approach. Phys. Rev. B 92, 214409 (2015).

Kolomeisky, E. B., Zaidi, H., Langsjoen, L. & Straley, J. P. Weyl problem and Casimir effects in spherical shell geometry. Phys. Rev. A 87, 042519 (2013).

Roldán-Molina, A., Santander, M. J., Nunez, A. S. & Fernández-Rossier, J. Quantum fluctuations stabilize skyrmion textures. Phys. Rev. B 92, 245436 (2015).

Ivanov, B. A., Sheka, D. D., Kryvonos, V. V. & Mertens, F. G. Quantum effects for the two-dimensional soliton in isotropic ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 75, 132401 (2007).

Cheng, R., Xiao, D. & Zhu, J.-G. Interlayer couplings mediated by antiferromagnetic magnons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 207202 (2018).

Saito, H. & Hyuga, H. Dynamical Casimir effect for magnons in a spinor Bose-Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. A 78, 033605 (2008).

Tserkovnyak, Y., Brataas, A., Bauer, G. E. W. & Halperin, B. I. Nonlocal magnetization dynamics in ferromagnetic heterostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 1375–1421 (2005).

Chumak, A. V., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnon spintronics. Nat. Phys. 11, 453 (2015).

Yuan, H., Cao, Y., Kamra, A., Duine, R. A. & Yan, P. Quantum magnonics: when magnon spintronics meets quantum information science. Phys. Rep. 965, 1–74 (2022).

Hurst, H. M. & Flebus, B. Non-Hermitian physics in magnetic systems. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 220902 (2022).

Yu, T., Zou, J., Zeng, B., Rao, J. & Xia, K. Non-Hermitian topological magnonics. Phys. Rep. 1062, 1–86 (2024).

Gilbert, T. L. A Lagrangian formulation of the gyromagnetic equation of the magnetization field. Phys. Rev. 100, 1243 (1955).

Nakata, K. & Suzuki, K. Magnonic Casimir effect in ferrimagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 096702 (2023).

Kato, T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators (Springer, 1966).

Gong, T., Corrado, M. R., Mahbub, A. R., Shelden, C. & Munday, J. N. Recent progress in engineering the Casimir effect - applications to nanophotonics, nanomechanics, and chemistry. Nanophotonics 10, 523–536 (2021).

Anderson, P. W. An approximate quantum theory of the antiferromagnetic ground state. Phys. Rev. 86, 694–701 (1952).

Majlis, N. The Quantum Theory of Magnetism 2nd ed. (World Scientific Publishing, 2007).

See Supplemental Material for more details: We add an explanation about the Casimir energy induced by quantum fields on the lattice and provide some details about the magnonic Casimir effect in the absence of the hard-axis anisotropy. We also add remarks on, in order, observation of the magnonic Casimir effect in the AFMs, Casimir effects from other origins, thermal effects, higher energy bands, edge or surface magnon modes, and the effect of the edge condition.

Lee, K. et al. Superluminal-like magnon propagation in antiferromagnetic NiO at nanoscale distances. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1337–1341 (2021).

Dehmollaian, M. & Caloz, C. General mapping between complex spatial and temporal frequencies by analytical continuation. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 69, 6531–6545 (2021).

Tserkovnyak, Y. Exceptional points in dissipatively coupled spin dynamics. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013031 (2020).

Actor, A., Bender, I. & Reingruber, J. Casimir effect on a finite lattice. Fortschr. Phys. 48, 303–359 (2000).

Pawellek, M. Finite-sites corrections to the Casimir energy on a periodic lattice. Preprint at arXiv:1303.4708 (2013).

Ishikawa, T., Nakayama, K. & Suzuki, K. Casimir effect for lattice fermions. Phys. Lett. B 809, 135713 (2020).

Ishikawa, T., Nakayama, K. & Suzuki, K. Lattice-fermionic Casimir effect and topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 023201 (2021).

Nakayama, K. & Suzuki, K. Remnants of the nonrelativistic Casimir effect on the lattice. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, L022054 (2023).

Mandlecha, Y. V. & Gavai, R. V. Lattice fermionic Casimir effect in a slab bag and universality. Phys. Lett. B 835, 137558 (2022).

Nakayama, K. & Suzuki, K. Dirac/Weyl-node-induced oscillating Casimir effect. Phys. Lett. B 843, 138017 (2023).

Cheetham, A. K. & Hope, D. A. O. Magnetic ordering and exchange effects in the antiferromagnetic solid solutions MnxNi1−xO. Phys. Rev. B 27, 6964–6967 (1983).

Chen, Y. et al. Lattice distortion and electronic structure of magnesium-doped nickel oxide epitaxial thin films. Phys. Rev. B 95, 245301 (2017).

Ambjorn, J. & Wolfram, S. Properties of the vacuum. I. Mechanical and thermodynamic. Ann. Phys 147, 1–32 (1983).

Hays, P. Vacuum fluctuations of a confined massive field in two dimensions. Ann. Phys. 121, 32–46 (1979).

Chumak, A. V., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnon transistor for all-magnon data processing. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–8 (2014).

Zou, J., Zhang, S. & Tserkovnyak, Y. Bell-state generation for spin qubits via dissipative coupling. Phys. Rev. B 106, L180406 (2022).

Yuan, H. Y., Sterk, W. P., Kamra, A. & Duine, R. A. Pure dephasing of magnonic quantum states. Phys. Rev. B 106, L100403 (2022).

Zou, J., Bosco, S., Thingstad, E., Klinovaja, J. & Loss, D. Dissipative spin-wave diode and nonreciprocal magnonic amplifier. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036701 (2024).

Tupitsyn, I. S., Stamp, P. C. E. & Burin, A. L. Stability of Bose-Einstein condensates of hot magnons in yttrium iron garnet films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 257202 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ryo Hanai, Hosho Katsura, Norio Kawakami, Se Kwon Kim, Katsumasa Nakayama, Masatoshi Sato, Kenji Shimomura, Ken Shiozaki, Keisuke Totsuka, Shun Uchino, and Hikaru Watanabe for helpful comments and discussions. We acknowledge support by JSPS KAKENHI Grants No. JP20K14420 (K.N.), No. JP22K03519 (K.N.), No. JP17K14277 (K.S.), and No. JP20K14476 (K.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The two authors (K.N. and K.S.) contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakata, K., Suzuki, K. Non-Hermitian Casimir effect of magnons. npj Spintronics 2, 11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-024-00017-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-024-00017-4