Abstract

Understanding the coherent interplay of light with the magnetization in metals has been a long-standing problem in ultrafast magnetism. While it is known that when laser light acts on a metal it can induce magnetization via the process known as the inverse Faraday effect (IFE), the most basic ingredients of this phenomenon are still largely unexplored. In particular, given a strong recent interest in orbital non-equilibrium dynamics and its role in mediating THz emission in transition metals, the exploration of distinct features in spin and orbital IFE is pertinent. Here, we present a first complete study of the spin and orbital IFE in 3d, 4d and 5d transition metals of groups IV–XI from first-principles. By examining the dependence on the light polarization and frequency, we show that the laser-induced spin and orbital moments may vary significantly both in magnitude and sign. We underpin the interplay between the crystal field splitting and spin-orbit interaction as the key factor which determines the magnitude and key differences between the spin and orbital response. Additionally, we highlight the anisotropy of the effect with respect to the ferromagnetic magnetization and to the crystal structure. The here-provided complete map of IFE in transition metals is a key reference point in the field of opto-magnetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The demonstration of ultrafast demagnetization in ferromagnets by the application of femtosecond laser pulses1 gave rise to the field of ultrafast spintronics and set the stage for efficient manipulation of magnetism by light. By now it has been rigorously demonstrated that all-optical helicity-dependent magnetization switching can be achieved in wide classes of magnetic materials2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, thus paving the way to contactless ultrafast magnetic recording. In interpretations of the switching experiments, the inverse Faraday effect (IFE)—i.e., the phenomenon of magnetization induced by a coherent interaction with light acting on a material—has been considered as one of the major underlying mechanisms for the magnetization reversal. Although theoretically predicted and experimentally observed decades ago11,12,13, a consensus in the theoretical understanding of IFE is still lacking14,15,16,17,18,19 – however, several microscopic methods have been recently developed for the calculation of this phenomenon in diverse setups20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28.

Apart from its established role in the magnetization switching of ferromagnets and ferrimagnets, the impact of IFE in the THz regime has also been studied in antiferromagnets like CrPt29 and Mn2Au30. Moreover, it has been shown that the component of IFE which is perpendicular to the magnetization direction behaves differently with respect to the light helicity than the parallel component21, giving rise to helicity-dependent optical torques31,32,33 and THz emission34. The impact of the optical torques has been demonstrated to be significant in antiferromagnetic Mn2Au35 where transverse IFE may be responsible for the THz emission36,37, provide an alternative way to switching the magnetization38 as well as to drive domain wall motion39. Recently it has also been shown that light can induce colossal magnetic moments in altermagnets40. Although IFE is conventionally associated with an excitation by circularly polarized light, it can also be activated by linearly-polarized laser pulses25,30,40,41,42,43.

In solids, two contributions to the magnetization exist: due to spin and orbital moment of electrons. And while the discussion of IFE is normally restricted to the response of spin, since recently, non-equilibrium dynamics of orbital angular momentum started to attract significant attention44,45,46. Namely, the emergence of orbital currents in the context of the orbital Hall effect47,48,49,50, orbital nature of current-induced torques on the magnetization51,52,53, and current-induced orbital accumulation sizeable even in light materials54,55,56,57 have been addressed theoretically and demonstrated experimentally. Notably, in the context of light-induced magnetism, Berritta et al. have predicted that the IFE in selected transition metals can exhibit a sizeable orbital component20, with the generality of this observation reaching even into the realm of altermagnets40. At the same time it is also known that within the context of plasmonic IFE the orbital magnetic moment due to electrons excited by laser pulses in small nanoparticles of noble and simple metals can reach atomic values58,59,60. Despite the fact that very little is known about the interplay of spin and orbital IFE in real materials, it is believed that IFE is a very promising effect in the context of orbitronics—a field which deals with manipulation of the orbital degree of freedom by external perturbations.

Although the importance of IFE in mediating the light-induced magnetism is beyond doubt, a comprehensive in-depth material-specific knowledge acquired from microscopic theoretical analysis of this effect is still missing. While acquiring this knowledge is imperative for the field of ultrafast spintronics, since the initial seminal work by Berritta et al.20, very little effort has been dedicated to the explorations of this phenomenon from first principles. Here, we fill this gap by providing a detailed first-principles study of the light-induced spin and orbital magnetism for the 3d, 4d and 5d transition metals of groups IV–XI. By exploring the dependence on the frequency and the polarization of light, we acquire insights into the origin and differences between spin and orbital flavors of IFE, as well as key features of their behavior. Our work provides a solid foundation for further advances in the field of optical magnetism and interaction of light and matter.

Results

Light-induced magnetism in transition metals

We begin our discussion by exploring the IFE in a series of 3d, 4d and 5d transition metals of groups IV–XI. IFE is a non-linear opto-magnetic effect in which magnetization \(\delta {\mathcal{}}O\propto {\bf{E}}\times {{\bf{E}}}^{* }\) is induced as a second-order response to the electric field E of a laser pulse. We calculate the light-induced spin δS and orbital δL magnetic moments by means of the Keldysh formalism, see the section “Methods”21,40. We focus on light energies ℏω of 0.25 eV and 1.55 eV which have been routinely used before in our studies within the same formalism30,40,61. In all calculations we choose the light to be circularly polarized in the xy or yz planes with a light intensity I of 10 GW/cm2. The energy of 1.55 eV corresponds to a wavelength of 800 nm and together with the 10 GW/cm2 intensity are routinely used in experiments with Ti:sapphire lasers34,62,63,64. The light energy of 0.25 eV is chosen since it is comparable to strength of the spin-orbit interaction and it has been predicted to give rise to significant light-induced moments in altermagnets40. Additionally, we choose a lifetime broadening Γ of 25 meV that corresponds to room temperature in order to account for effects of disorder on the electronic states and to provide realistic estimations of the effect. Lastly, for magnetic materials, ferromagnetic magnetization is considered to be along the z-axis. A schematic picture of the IFE is presented in Fig. 1.

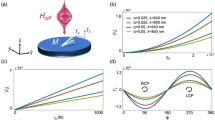

In Fig. 2, we present the calculated light-induced δLz (Fig. 2a, c) and δSz (Fig. 2b, d) moments of the considered transition metals at the Fermi energy. Light is circularly polarized in the xy plane, with energies ℏω of 0.25 eV (Fig. 2a, b) and 1.55 eV (Fig. 2c, d). Regarding the 3d magnetic elements Fe, Co, and Ni, we analyze both right and left handed circular polarizations of light. The exact values of δLz and δSz are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 of the Supplementary Material (SM). Not shown are computed transverse x and y components of the light-induced moments, which we find to be orders of magnitude smaller for the case of xy-polarized light, and which we discuss later.

Light-induced orbital δLz (a, c) and spin δSz (b, d) magnetic moments in 3d (red circles), 4d (green squares) and 5d (blue triangles) transition metals of groups IV–XI. In all calculations light is considered to be circularly polarized in the xy-plane. For the 3d magnetic elements (Fe, Co, and Ni) the moments that arise for left-handedly polarized light are shown with light red crosses. The light frequency is ℏω = 0.25 eV in (a, b) and ℏω = 1.55 eV in (c, d).

At first sight we notice a strong dependence of the magnitude and sign of both δLz and δSz on the light frequency. We point out the case of fcc Rh where an colossal δLz = −56 ⋅ 10−3μB is predicted at ℏω = 0.25 eV and which is drastically reduced at the higher frequency, while the spin component remains suppressed in both cases. For the case of magnetic hcp Co we notice a helicity-dependent change of sign for δLz at ℏω = 0.25 eV which is not present for δSz. In general, δLz varies stronger with the light helicity than δSz. Moreover, δLz is one to two orders of magnitude larger than δSz for the non-magnetic elements, while they are of the same magnitude for the magnetic elemental materials. The last two observations are in agreement with the findings of ref. 20 and indicate how the spontaneous magnetization strongly influences the effect in ferromagnets by the time-reversal symmetry breaking. For comparison, in Table 1 we list the values of the total light-induced moments, defined as the sum of δLz and δSz, for the transitional metals studied in 20 with ℏω = 1.55 eV. Our calculated values are of the same order of magnitude, with the exceptions of Au, and of Co for the case of left-handed polarization, which can be attributed to the difference in the computational methods and calculation parameters, e.g., different lifetime broadening values.

From Fig. 2c, d, we get a clear picture of how the induced moments scale with the strength of spin-orbit coupling (SOC). The effect is overall larger for the heavier 5d elements, both in the orbital δLz and spin δSz channels. However, at the lower frequency of ℏω = 0.25 eV it is more difficult to draw such a conclusion since the corresponding photon energy falls into the range of SOC strength, which promotes the role of electronic transitions among spin-orbit split bands occurring within a narrow range around the Fermi energy and limited regions in k-space. In contrast, the use of a much larger frequency involves transitions among manifestly orbitally-distinct states which take place over larger portions of the reciprocal space with a more uniform impact of the spin-orbit strength on the magnitude of the transition probabilities. From this discussion we have to exclude the ferromagnetic elements since the spontaneous magnetization induces band-splittings on the scale of exchange strength therefore making the effect much more complex.

We study the dependence on the light polarization by performing additional calculations for light circularly polarized in the yz-plane, presenting the results for the z and x components of δL and δS respectively in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 of the SM for ℏω = 0.25 eV and ℏω = 1.55 eV. Our results for δSz and δSx for the magnetic transition metals reproduce exactly the values of ref. 21, computed with the same method. We further present the values of δLz and δLx, where we find the orbital response along the magnetization, δLz, to be by a factor of two larger than the corresponding spin response, when averaged over all magnetic elements. Generally, for the z-component the effect at the magnetic elements is similar in magnitude with the case of polarization in the xy-plane shown in Fig. 2, and even in the light helicity, while it vanishes for the non-magnetic elements. On the other hand, for the x-component the effect at the magnetic elements becomes one-two orders of magnitude smaller and is odd in the light helicity, although for the non-magnetic elements the values are comparable to the case shown in Fig. 2. It is important to note that for light circularly-polarized in the plane containing ferromagnetic magnetization, the light-induced transverse to magnetization induced moments, even though being smaller than the longitudinal ones, are related to light-induced torques that are experimentally demonstrated to lead to helicity-dependent THz emission21,34.

In order to get a better understanding of the impact of the time-reversal symmetry breaking on IFE, we consider the cases of ferromagnetic, non-relativistic (i.e., computed without SOC) ferromagnetic, and antiferromagnetic fcc Ni. In Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 of the SM we present the band filling dependence of the Cartesian components of the light-induced orbital moments δL, for ℏω = 0.25 eV and ℏω = 1.55 eV, respectively. In the non-relativistic case only a δLi parallel to the light propagation axis is induced which is odd in the helicity, and no δSi is induced, exemplifying that the orbital response is the primary non-relativistic one, whereas the spin response is generated through SOC, as was also shown in ref. 20. Similarly, for the antiferromagnetic case, only a component parallel to the light propagation axis is induced which is odd in the helicity and remains unchanged under different polarization flavors. While this is the case also for the induced components δLx and δLy which are transverse to the magnetization in the ferromagnetic case, the situation drastically changes for the induced component δLz parallel to the magnetization, as discussed earlier. We note that a tiny, odd in the helicity, δLx or δLy is additionally induced when light is rotating in a plane containing ferromagnetic magnetization. On the other hand, the induced δLx and δLy, developing normal to the polarization plane, serve as a non-relativistic “background” which is independent of the magnetization, with features due to the crystal structure driving the effect over larger regions in energy. The additional band-splittings induced by SOC result in the IFE exhibiting more features with band filling in the relativistic scenario. Remarkably, while the relativistic antiferromagnetic and non-relativistic ferromagnetic cases in principle have similar to each other behavior in energy, a larger signal arises in the antiferromagnetic case by the virtue of flatter bands (see also the discussion for Hf and Pt below). Lastly, we note that a similar behavior has been observed for the in-plane spin IFE in PT-symmetric Mn2Au, however, in the latter case additional out-of-plane moments arise due to linearly polarized light as a result of broken by the magnetization inversion symmetry30.

Next, we focus on the case of 5d transition metals where in Fig. 3a, b we explore the relation of δLz and δSz, respectively, to the band filling, for light circularly polarized in the xy plane and the frequency of ℏω = 1.55 eV. When going from group IV (hcp Hf) to XI (fcc Au) we observe a smooth variation of δLz from positive to negative values, as well as nicely shaped plateaus, where δLz remains relatively robust in a wide energy region, for hcp Hf, bcc Ta, bcc W, fcc Ir, and fcc Pt. We note that such plateaus are often characteristic of orbital effects, as witnessed for example in orbital Hall insulators65,66,67 and orbital Rashba systems61. On the contrary, δSz exhibits a very erratic behavior with strong variations for each material, at the same time being much smaller in magnitude than δLz. The above observation is a clear manifestation of how differently the orbital and spin degrees of freedom behave under light excitation, with the orbital angular momentum having its origin in intrinsic structural parameters as manifested in the crystal field splitting, whereas the spin angular momentum is more sensitive to finer details of the electronic structure mediated by SOC. Indeed, the light-induced spin and orbital moments exhibit similarly erratic behavior with band filling once the frequency of the light is drastically reduced to reach the range of spin-orbit interaction, see Supplementary Fig. 5 of the SM for ℏω = 0.25 eV.

Anatomy of IFE in k-space

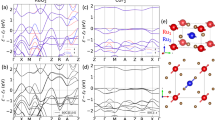

Among the 5d transition metals, hcp Hf and fcc Pt exhibit the largest computed moments at the Fermi energy for ℏω = 1.55 eV, with the corresponding values of δLz = 9.1 ⋅ 10−3μB, δSz = −0.8 ⋅ 10−3μB for Hf, and δLz = −7.4 ⋅ 10−3μB, δSz = −1.1 ⋅ 10−3μB for Pt. Therefore, we select these two materials and explore the behavior of their light-induced moments in reciprocal space. We present the band-resolved δLz and δSz for hcp Hf in Fig. 4a, b, as well as band-resolved δLz and δSz for fcc Pt in Fig. 4e, f. For the case of Hf, transitions along the bands near the A-point are the main source of δLz and δSz. Light-induced δLz consists of hotspot-like positive contributions which lead to a large positive orbital integrated response. On the other hand, δSz in Hf presents a much richer anatomy with both negative and positive contributions at times emerging within the same band in the narrow neighboring regions of the reciprocal space.

Band-resolved light-induced orbital δLz (a, c, e) and spin δSz (b, d, f) magnetic moments in hcp Hf (a–d) and fcc Pt (e, f) at the true Fermi energy level \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}\) (dashed gray line in a, b and e, f) or at the shifted Fermi energy level \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}^{{\prime} }={{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}+0.75\) eV (dashed gray line in c, d). The horizontal dotted red lines at \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}\pm 1.55\) eV correspond to the frequency of the light. Reciprocal space distribution of light-induced orbital (g, i, k) and spin (h, j, l) magnetic moments in hcp Hf (g–j) and fcc Pt (k, l) at the true Fermi energy \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}\) (g, h, k, l) or at the shifted Fermi energy level \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}^{{\prime} }={{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}+0.75\) eV (i, j). In all calculations light is circularly polarized in the xy-plane at the frequency of ℏω = 1.55 eV.

Furthermore, in Fig. 4c, d we present the band-resolved δLz and δSz for hcp Hf at the shifted Fermi energy level \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}^{{\prime} }={{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}+0.75\) eV, which falls right into the robust plateau which is observed in the orbital signal for hcp Hf in Fig. 3a. By comparing with the band-resolved moments at the true Fermi energy level in Fig. 4a, b, we clearly observe an increase in the number of the activated transitions which can be translated into the appearance of the robust plateau in the integrated δLz. At this shifted Fermi energy level, and with the usage of a frequency of ℏω = 1.55 eV, the whole group of Hf 5d-states participates in the effect, thus giving rise to more transitions than it was possible at the true Fermi energy level. This activation of transitions within the group of 5d bands is the mechanism for the appearance of the plateaus in the response of the 5d elements. Similar correspondence between the appearance of a robust plateau in an orbital signal and the number of activated transitions has been observed at the BiAg2 surface where the Bi p-states are subject to the orbital Rashba effect61.

For the case of Pt, δLz and δSz arise from transitions close to X and L high-symmetry points, with both originating in roughly the same regions of \(({\mathcal{E}},k)\)-space, but often having an opposite sign to each other. Note that the bands in Pt are much more dispersive in the considered energy window, which results in an effective reduction of the regions in \(({\mathcal{E}},k)\)-space which contribute to the spin and orbital response alike. This is in contrast to Hf, where much flatter bands reside above and below the Fermi energy within the energy window of the laser pulse, providing significant integrated, albeit very small locally, contributions. Moreover, in fcc Pt the Fermi energy cuts through the band edges of the d-states, where the effect of spin-orbit interaction is the strongest, which explains the emergence of strong hotspot-like contributions with a clear correlation in the magnitude of spin and orbital response and the resultant similar behavior of δLz and δSz with band filling around the Fermi energy.

We further scrutinize the reciprocal space distribution of δLz and δSz, shown for hcp Hf and fcc Pt at the true Fermi energy level \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}\) in Fig. 4g, h and k, l, respectively. For both materials δLz distributions consist of large uniform areas of either positive or negative sign. On the contrary, δSz distributions are much finer and richer in details with more areas of opposite sign, consistent with the picture we drew above from the band-resolved analysis. A similar behavior of the light-induced magnetism in reciprocal space has been recently reported for rutile altermagnets40. We also observe that, as discussed above, while for Hf the contributions are well spread throughout the Brillouin zone, for Pt the spin and orbital contributions are located at the edges of the considered kz − ky plane. Overall, this fact indicates that the microscopic behavior of light-induced magnetism varies strongly among transition metals and crucially depends on the crystal structure and position of the Fermi level with respect to the states split by the crystal field and spin-obit interaction.

Additionally, we compare the reciprocal space distribution of δLz and δSz at the true and at the shifted Fermi energy levels, in Fig. 4g, h and i, j, respectively, by using the same color scale. We notice that δLz at the shifted Fermi level is dominated by a very large positive contribution at the center of the Brillouin zone, while secondary positive and negative contributions exist while moving away from the Γ-point. The situation is drastically different for δLz at the true Fermi level (see Fig. 3c) where the central contribution becomes orders of magnitude smaller and the effect is now dominated by the contributions around the edges of the Brillouin zone. On the contrary, the distribution of δSz exhibits a similarly fine anatomy at both Fermi levels, with the individual details not having a significant impact on the overall magnitude of the response.

Anisotropy of light-induced magnetism

We first address the anisotropy of light-induced magnetism with respect to the magnetization by examining the response of magnetic elements under different flavors of circular polarization. In Fig. 5a, b, we present the computed δLz and δSz in relation to scattering lifetime Γ, for the cases of magnetic bcc Fe and hcp Co under excitation by light which is circularly polarized in the xy or yz planes at ℏω = 1.55 eV. As we have already seen in Fig. 2 for light polarized in the xy-plane, the responses behave differently for right (solid lines) or left (dashed lines) polarization. This difference is more pronounced for δLz, for which we even observe a change of sign for Co. Surprisingly, the situation is drastically different for the case of yz-polarization. In this case, for bcc Fe the response is even in the helicity, while for hcp Co δLz is almost even and δSz is perfectly even in the helicity. Such different behavior with respect to the light helicity between the two magnetic elements can be traced back to the additional anisotropy originating in the crystal structure itself—an effect which we discuss below. Notably, we witness a highly non-linear behavior with respect to Γ, with the response reaching colossal values in the clean limit. For example, δLz and δSz can reach as much as 40 ⋅ 10−3μB and 70 ⋅ 10−3μB in Co, respectively, given the scattering lifetime of 1 meV. Besides the potential tunability of the inverse Faraday effect by the degree of the disorder of the samples, one key message that we extract from our observations is that when comparing the values for laser-induced magnetic moments obtained with different methods, special care has to be taken since the implementations of disorder effects, even within a simple constant broadening model, may differ among various approaches.

Light-induced orbital δLz (a) and spin δSz (b) magnetic moments in relation to the lifetime broadening for ferromagnetic bcc Fe and hcp Co. Light is circularly polarized in the xy-plane (brown curves for bcc Fe and light green curves for hcp Co) or in the yz-plane (light blue curves for bcc Fe and light purple curves for hcp Co). Both right-handed (solid lines) and left-handed (dashed lines) polarizations are displayed. The horizontal red dotted line depicts the lifetime broadening value Γ = 25 meV. The ferromagnetic magnetization is along the z-axis. The light frequency is set at ℏω = 1.55 eV.

Finally, we analyze the anisotropy that the crystal structure induces in the light-induced magnetism. We select the case of hcp Re and present in Fig. 6a, b the x and z components of δL and δS, respectively, in relation to Γ. Due to the inequivalence of x and z axes in the hcp structure, the δLz which originates in light circularly polarized in the xy-plane (light blue line) differs from the δLx for the case of the yz polarization (brown line). The situation is similar for the case of δSz and δSx. On the contrary, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 6 of the SM, in the case of fcc Pt we have a perfect match between δLz and δLx (or δSz and δSx) when changing the plane of circular polarization because the x and z axes are equivalent in the fcc structure. The situation is similar for the y component when light is circularly polarized in the xz-plane. As also expected from the symmetry of the crystal structure, we confirm that the light-induced moments are perfectly odd in the helicity for the nonmagnetic elements, which is not the case for the magnetic elements, see Fig. 6 of the main text and Supplementary Fig. 6 of the SM20.

Light-induced orbital δL (a) and spin δS (b) magnetic moments in relation to the lifetime broadening for nonmagnetic hcp Re. The induced magnetic moments along the x-axis and along the z-axis are shown. Light is considered to be circularly polarized in the xy-plane (brown curves) or in the yz-plane (light blue curves). Both right-handed (solid lines) and left-handed (dashed lines) polarizations are displayed. The horizontal red dotted line depicts the lifetime broadening value Γ = 25 meV. The light frequency is set at ℏω = 1.55 eV.

Discussion

The main goal of our work is to showcase the importance of the orbital component of IFE and its distinct behavior from the spin counterpart. While so far it was mainly the interaction of light with the spin magnetization that was taken into consideration for the interpretation of IFE-related effects, we speculate that the orbital IFE may provide a novel way to coherently induce magnetization and manipulate the magnetic order. For example, in a recent study, different types of optical torques that may arise in ferromagnetic layers were interpreted in terms of the light-induced orbital moment and its interaction with the magnetization through the spin-orbit interaction68. Since it is known that current-induced orbital accumulation and orbital torques exhibit a long-range behavior50,69,70,71 due to a characteristic small orbital decay, a question arises whether similar behavior can be exhibited by optical torques caused by the orbital IFE. The emergence of long-ranged orbital IFE would come as no surprise given the fact that several recent experiments reported that laser excitation can drive long-range ballistic orbital currents resulting in THz emission72,73,74,75.

Although in our treatment the effect of light enters only as a perturbation by the electric field of the original ground state Hamiltonian, it is common to utilize the angular momentum of light in order to understand the interaction with the magnetic order by the means of transfer of angular momentum. The spin of light through the helicity of circularly polarized pulses plays a crucial role in helicity-dependent all-optical switching scenarios. On the other hand, there is a strong recent interest in utilizing the orbital angular momentum of light via irradiation of matter with e.g., vortex beams or twisted light, in order to probe the magnetization76, generate photocurrents77, drive ultrafast demagnetization78, and induce IFE41,79. Therefore, it is imperative to treat both spin and orbital degrees of freedom on equal footing when exploring the light-matter interaction. This will not only trigger further advances in the field of ultrafast magnetism and THz spintronics, but also enable a transition to the novel field of attosecond opto-spintronics80,81.

Methods

First-principles calculations details

In this work we calculate the first-principles electronic structures of 3d, 4d and 5d transition metals by using the full-potential linearized augmented plane wave FLEUR code82. We describe exchange and correlation effects by using the non-relativistic PBE83 functional, while relativistic effects are described by the second-variation scheme84. The parameters of our first-principles calculations, i.e., lattice constants, muffin-tin radii, plane-wave cutoffs, etc. are taken from Table I of ref. 85.

Next, we construct maximally-localized Wannier functions (MLWFs) by employing the Wannier90 code86 and its interface with the FLEUR code87. Similarly to ref. 85, we choose s, p and d orbitals for the initial projections and disentangle 18 MLWFs out of 36 Bloch states within a frozen window of 5.0 eV above the Fermi energy for each atom in the unit cell.

Lastly, at a post-processing step, we calculate the laser-induced orbital and spin magnetizations according to the Keldysh formalism21,40:

where \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{i}\) is the i-th component of either the orbital angular momentum operator Li or of the spin operator Si. Moreover, a0 = 4πϵ0ℏ2/(mee2) is the Bohr’s radius, \(I={\epsilon }_{0}c{E}_{0}^{2}/2\) is the intensity of the pulse, ϵ0 is the vacuum permittivity, me is the electron mass, e is the elementary charge, ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, c is the light velocity, \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{H}={e}^{2}/(4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}{a}_{0})\) is the Hartree energy, and ϵj is the j-th component of the polarization vector of the pulse. For example, we describe right/left-handedly polarized light in the xy-plane as \(\epsilon =(1,\pm i,0)/\sqrt{2}\), respectively, and define its propagation vector to lie along the normal to the polarization plane. A detailed form of the tensor φijk can be seen in Eq. (14) of ref. 21. For the orbital response, the prefactor in Eq. (1) must be multiplied by an additional factor of 2. A 128 × 128 × 128 interpolation k-mesh is sufficient to obtain well-converged results. In all calculations the lifetime broadening Γ was set at 25 meV, the light frequency ℏω at 0.25 eV and 1.55 eV, the intensity of light at 10 GW/cm2, and we covered an energy region of [−2.5, 2.5] eV around the Fermi energy level \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{F}\).

Data availability

The data presented in this work can be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Beaurepaire, E., Merle, J.-C., Daunois, A. & Bigot, J.-Y. Ultrafast spin dynamics in ferromagnetic nickel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4250–4253 (1996).

Kimel, A. V. et al. Ultrafast non-thermal control of magnetization by instantaneous photomagnetic pulses. Nature 435, 655–657 (2005).

Stanciu, C. D. et al. All-optical magnetic recording with circularly polarized light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 047601 (2007).

Vahaplar, K. et al. Ultrafast path for optical magnetization reversal via a strongly nonequilibrium state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 117201 (2009).

Kirilyuk, A., Kimel, A. V. & Rasing, T. Ultrafast optical manipulation of magnetic order. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2731–2784 (2010).

Steil, D., Alebrand, S., Hassdenteufel, A., Cinchetti, M. & Aeschlimann, M. All-optical magnetization recording by tailoring optical excitation parameters. Phys. Rev. B 84, 224408 (2011).

Khorsand, A. R. et al. Role of magnetic circular dichroism in all-optical magnetic recording. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 127205 (2012).

Alebrand, S. et al. Light-induced magnetization reversal of high-anisotropy TbCo alloy films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 162408 (2012).

Mangin, S. et al. Engineered materials for all-optical helicity-dependent magnetic switching. Nat. Mater. 13, 286–292 (2014).

John, R. et al. Magnetisation switching of FePt nanoparticle recording medium by femtosecond laser pulses. Sci. Rep. 7, 4114 (2017).

Pitaevskii, L. Electric forces in a transparent dispersive medium. Sov. Phys. JETP 12, 1008 (1960).

van der Ziel, J. P., Pershan, P. S. & Malmstrom, L. D. Optically-induced magnetization resulting from the inverse Faraday effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15, 190–193 (1965).

Pershan, P. S., van der Ziel, J. P. & Malmstrom, L. D. Theoretical discussion of the inverse Faraday effect, Raman scattering, and related phenomena. Phys. Rev. 143, 574–583 (1966).

Hertel, R. Theory of the inverse Faraday effect in metals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 303, L1–L4 (2006).

Zhang, H.-L., Wang, Y.-Z. & Chen, X.-J. A simple explanation for the inverse Faraday effect in metals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 321, L73–L74 (2009).

Popova, D., Bringer, A. & Blügel, S. Theory of the inverse Faraday effect in view of ultrafast magnetization experiments. Phys. Rev. B 84, 214421 (2011).

Popova, D., Bringer, A. & Blügel, S. Theoretical investigation of the inverse Faraday effect via a stimulated Raman scattering process. Phys. Rev. B 85, 094419 (2012).

Battiato, M., Barbalinardo, G. & Oppeneer, P. M. Quantum theory of the inverse Faraday effect. Phys. Rev. B 89, 014413 (2014).

Hertel, R. & Fähnle, M. Macroscopic drift current in the inverse Faraday effect. Phys. Rev. B 91, 020411 (2015).

Berritta, M., Mondal, R., Carva, K. & Oppeneer, P. M. Ab initio theory of coherent laser-induced magnetization in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 137203 (2016).

Freimuth, F., Blügel, S. & Mokrousov, Y. Laser-induced torques in metallic ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 94, 144432 (2016).

Qaiumzadeh, A. & Titov, M. Theory of light-induced effective magnetic field in Rashba ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 94, 014425 (2016).

Mironov, S. V. et al. Inverse Faraday effect for superconducting condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 137002 (2021).

Banerjee, S., Kumar, U. & Lin, S.-Z. Inverse Faraday effect in Mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B 105, L180414 (2022).

Zhou, J. Photo-magnetization in two-dimensional sliding ferroelectrics. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 15 (2022).

Sharma, P. & Balatsky, A. V. Light-induced orbital magnetism in metals via inverse Faraday effect. Phys. Rev. B 110, 094302 (2024).

Wong, P. J., Khaymovich, I. M., Aeppli, G. & Balatsky, A. V. Large inverse Faraday effect for Rydberg states of free atoms and isolated donors in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 111, 064425 (2025).

Hamamera, H., Souza Mendes Guimarães, F., dos Santos Dias, M. & Lounis, S. Ultrafast light-induced magnetization in non-magnetic films: from orbital and spin Hall phenomena to the inverse Faraday effect. Front. Phys. 12 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physics/articles/10.3389/fphy.2024.1354870 (2024).

Dannegger, T. et al. Ultrafast coherent all-optical switching of an antiferromagnet with the inverse Faraday effect. Phys. Rev. B 104, L060413 (2021).

Merte, M. et al. Photocurrents, inverse Faraday effect, and photospin Hall effect in Mn2Au. APL Mater. 11, 071106 (2023).

Choi, G.-M., Schleife, A. & Cahill, D. G. Optical-helicity-driven magnetization dynamics in metallic ferromagnets. Nat. Commun. 8, 15085 (2017).

Iihama, S., Ishibashi, K. & Mizukami, S. Interface-induced field-like optical spin torque in a ferromagnet/heavy metal heterostructure. Nanophotonics 10, 1169–1176 (2021).

Iihama, S., Ishibashi, K. & Mizukami, S. Photon spin angular momentum driven magnetization dynamics in ferromagnet/heavy metal bilayers. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 023901 (2022).

Huisman, T. J. et al. Femtosecond control of electric currents in metallic ferromagnetic heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 455–458 (2016).

Freimuth, F., Blügel, S. & Mokrousov, Y. Laser-induced torques in metallic antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 103, 174429 (2021).

Behovits, Y. et al. Terahertz Néel spin-orbit torques drive nonlinear magnon dynamics in antiferromagnetic Mn2Au. Nat. Commun. 14, 6038 (2023).

Huang, L. et al. Antiferromagnetic magnonic charge current generation via ultrafast optical excitation. Nat. Commun. 15, 4270 (2024).

Ross, J. L. et al. Ultrafast antiferromagnetic switching of Mn2Au with laser-induced optical torques. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 234 (2024).

Gavriloaea, P.-I. et al. Efficient motion of 90° domain walls in Mn2Au via pure optical torques. npj Spintronics 3, 11 (2025).

Adamantopoulos, T. et al. Spin and orbital magnetism by light in rutile altermagnets. npj Spintronics 2, 46 (2024).

Ali, S., Davies, J. R. & Mendonca, J. T. Inverse Faraday effect with linearly polarized laser pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 035001 (2010).

Gridnev, V. N. Optical spin pumping and magnetization switching in ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 88, 014405 (2013).

Mrudul, M. S. & Oppeneer, P. M. Ab initio investigation of laser-induced ultrafast demagnetization of L10 FePt: intensity dependence and importance of electron coherence. Phys. Rev. B 109, 144418 (2024).

Go, D., Jo, D., Lee, H.-W., Kläui, M. & Mokrousov, Y. Orbitronics: orbital currents in solids. Europhys. Lett. 135, 37001 (2021).

Go, D., Mokrousov, Y. & Kläui, M. Non-equilibrium orbital angular momentum for orbitronics. Europhys. N. 55, 28–31 (2024).

Jo, D., Go, D., Choi, G.-M. & Lee, H.-W. Spintronics meets orbitronics: emergence of orbital angular momentum in solids. npj Spintronics 2, 19 (2024).

Tanaka, T. et al. Intrinsic spin Hall effect and orbital Hall effect in 4d and 5d transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 77, 165117 (2008).

Kontani, H., Tanaka, T., Hirashima, D. S., Yamada, K. & Inoue, J. Giant orbital Hall effect in transition metals: origin of large spin and anomalous Hall effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 016601 (2009).

Go, D., Jo, D., Kim, C. & Lee, H.-W. Intrinsic spin and orbital Hall effects from orbital texture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 086602 (2018).

Choi, Y.-G. et al. Observation of the orbital Hall effect in a light metal Ti. Nature 619, 52–56 (2023).

Go, D. et al. Theory of current-induced angular momentum transfer dynamics in spin-orbit coupled systems. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033401 (2020).

Go, D. & Lee, H.-W. Orbital torque: torque generation by orbital current injection. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013177 (2020).

Lee, D. et al. Orbital torque in magnetic bilayers. Nat. Commun. 12, 6710 (2021).

Go, D. et al. Toward surface orbitronics: giant orbital magnetism from the orbital Rashba effect at the surface of sp-metals. Sci. Rep. 7, 46742 (2017).

Salemi, L., Berritta, M., Nandy, A. K. & Oppeneer, P. M. Orbitally dominated Rashba-Edelstein effect in noncentrosymmetric antiferromagnets. Nat. Commun. 10, 5381 (2019).

Go, D. et al. Orbital Rashba effect in a surface-oxidized Cu film. Phys. Rev. B 103, L121113 (2021).

Lyalin, I., Alikhah, S., Berritta, M., Oppeneer, P. M. & Kawakami, R. K. Magneto-optical detection of the orbital Hall effect in chromium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 156702 (2023).

Hurst, J., Oppeneer, P. M., Manfredi, G. & Hervieux, P.-A. Magnetic moment generation in small gold nanoparticles via the plasmonic inverse Faraday effect. Phys. Rev. B 98, 134439 (2018).

Cheng, O. H.-C., Son, D. H. & Sheldon, M. Light-induced magnetism in plasmonic gold nanoparticles. Nat. Photonics 14, 365–368 (2020).

Lian, D., Yang, Y., Manfredi, G., Hervieux, P.-A. & Sinha-Roy, R. Orbital magnetism through inverse Faraday effect in metal clusters. Nanophotonics 13, 4291–4302 (2024).

Adamantopoulos, T. et al. Orbital Rashba effect as a platform for robust orbital photocurrents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 076901 (2024).

Mikhaylovskiy, R. V. et al. Ultrafast optical modification of exchange interactions in iron oxides. Nat. Commun. 6, 8190 (2015).

Huisman, T. J., Mikhaylovskiy, R. V., Tsukamoto, A., Rasing, T. & Kimel, A. V. Simultaneous measurements of terahertz emission and magneto-optical kerr effect for resolving ultrafast laser-induced demagnetization dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 92, 104419 (2015).

Jungfleisch, M. B. et al. Control of terahertz emission by ultrafast spin-charge current conversion at Rashba interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 207207 (2018).

Canonico, L. M., Cysne, T. P., Molina-Sanchez, A., Muniz, R. B. & Rappoport, T. G. Orbital Hall insulating phase in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 101, 161409 (2020).

Cysne, T. P. et al. Disentangling orbital and valley Hall effects in bilayers of transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 056601 (2021).

Zeer, M. et al. Spin and orbital transport in rare-earth dichalcogenides: the case of EuS2. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 074004 (2022).

Nukui, K. et al. Light-induced torque in ferromagnetic metals via orbital angular momentum generated by photon-helicity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 016701 (2025).

Go, D. et al. Long-range orbital torque by momentum-space hotspots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 246701 (2023).

Bose, A. et al. Detection of long-range orbital-Hall torques. Phys. Rev. B 107, 134423 (2023).

Hayashi, H. et al. Observation of long-range orbital transport and giant orbital torque. Commun. Phys. 6, 32 (2023).

Seifert, T. S. et al. Time-domain observation of ballistic orbital-angular-momentum currents with giant relaxation length in tungsten. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-023-01470-8 (2023).

Wang, P. et al. Inverse orbital Hall effect and orbitronic terahertz emission observed in the materials with weak spin-orbit coupling. npj Quantum Mater. 8, 28 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Orbitronics: light-induced orbital currents in Ni studied by terahertz emission experiments. Nat. Commun. 15, 2043 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Efficient orbitronic terahertz emission based on CoPt alloy. Adv. Mater. 36, 2404174 (2024).

Sirenko, A. A. et al. Terahertz vortex beam as a spectroscopic probe of magnetic excitations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 237401 (2019).

Ji, Z. et al. Photocurrent detection of the orbital angular momentum of light. Science 368, 763–767 (2020).

Prinz, E., Stadtmüller, B. & Aeschlimann, M. Twisted light affects ultrafast demagnetization. https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.07502 (2022).

Karakhanyan, V., Eustache, C., Lefier, Y. & Grosjean, T. Inverse Faraday effect from the orbital angular momentum of light. Phys. Rev. B 105, 045406 (2022).

Siegrist, F. et al. Light-wave dynamic control of magnetism. Nature 571, 240–244 (2019).

Neufeld, O., Tancogne-Dejean, N., De Giovannini, U., Hübener, H. & Rubio, A. Attosecond magnetization dynamics in non-magnetic materials driven by intense femtosecond lasers. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 39 (2023).

Wortmann, D. et al. Fleur. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7891361 (2023).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Li, C., Freeman, A. J., Jansen, H. J. F. & Fu, C. L. Magnetic anisotropy in low-dimensional ferromagnetic systems: Fe monolayers on Ag(001), Au(001), and Pd(001) substrates. Phys. Rev. B 42, 5433–5442 (1990).

Go, D., Lee, H.-W., Oppeneer, P. M., Blügel, S. & Mokrousov, Y. First-principles calculation of orbital Hall effect by Wannier interpolation: role of orbital dependence of the anomalous position. Phys. Rev. B 109, 174435 (2024).

Pizzi, G. et al. Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 165902 (2020).

Freimuth, F., Mokrousov, Y., Wortmann, D., Heinze, S. & Blügel, S. Maximally localized Wannier functions within the FLAPW formalism. Phys. Rev. B 78, 035120 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Frank Freimuth and Maximilian Merte for discussions. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—TRR 173/3—268565370 (project A11) and by the K. and A. Wallenberg Foundation (Grants Nos. 2022.0079 and 2023.0336). We acknowledge support from the EIC Pathfinder OPEN grant 101129641 “OBELIX”. We also gratefully acknowledge the Jülich Supercomputing Centre and RWTH Aachen University for providing computational resources under projects jiff40 and jara0062.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.A. performed numerical calculations and analyzed the results. T.A. and Y.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in discussions of the results and reviewing of the manuscript. Y.M. conceived the idea and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adamantopoulos, T., Go, D., Oppeneer, P.M. et al. Light-induced orbital and spin magnetism in 3d, 4d, and 5d transition metals. npj Spintronics 3, 27 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00089-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00089-w