Abstract

We show that the initialization of an ensemble of electrons in the same spin state in strained n-InGaAs subject to a perpendicular magnetic field triggers an AC electric current at GHz frequencies. The AC current emerges in the absence of any electric driving force and survives until the coherent precession of the electron spins is lost. The current amplitude increases linearly with both the spin-orbit coupling strength and the external magnetic field. The generation mechanism of the observed oscillatory charge motion can be fruitfully described in terms of the periodic trembling motion of spin-polarized electrons, which is a solid-state analog to the Zitterbewegung of free Dirac electrons. Our results demonstrate that the hidden consequence of relativistic quantum mechanics is realized and can be studied in a rather simple solid-state system at moderate temperatures. Furthermore, the large amplitude of the AC current at high magnetic fields enables ultra-fast spin sensitive electric read-out in solids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The search for efficient and fast techniques to generate, manipulate and detect spin polarized carriers in semiconductors by pure electrical means is at the core of modern solid-state spintronics. It has been shown that these tasks can be fulfilled in III-V semiconductors by the use of spin-orbit interaction (SOI) providing a rich platform to couple the charge and spin degree of freedom1. SOI can convert a charge current into a homogeneous spin polarization (current-induced spin polarization)2,3,4,5,6 or into spin currents transverse to the charge current direction by spin dependent scattering (spin Hall effect)7,8,9,10. SOI can be also used for spin manipulation as it acts as an effective magnetic field where the spin precession can be controlled either by static or pulsed electrical field11,12,13,14,15. For electrical spin detection, spin-polarized electrons can drive a charge current by either the spin-galvanic effect16 or by the inverse spin Hall effect17. While most of these experiments have been extended into the time-domain by combining ultrafast electrical and optical techniques3,10,14,15,18,19, there have not been any studies on spin sensitive ultrafast electrical readout.

We show that electrons in solids can themselves drive an AC electric current if initialized in the same spin state. The effect is demonstrated for semiconductor epilayers subject to an in-plane static magnetic field. The AC current emerges in the absence of any driving force and is maintained until the spin ensemble dephases. The observed phenomenon can be described in a semi-classical way as an electric current caused by the spin precession in structures with spin-orbit coupling20. Alternatively, it can be viewed in a quantum-mechanical picture as a trembling motion of electrons, a phenomenon similar to the Zitterbewegung of Dirac electrons21,22,23,24,25,26. The oscillating contribution to the electron velocity originates from the interference of the spin states separated by the Zeeman gap. The AC electric current is observed together with the spin-galvanic effect contribution and can be distinguished by phase and magnetic field-dependence.

Results

Spin precession driven AC current generation

The experiments were performed on n-type In0.07Ga0.93As (n ~ 8.25 × 1016 cm−3) samples along different crystal axes (see Methods Section and Fig. 1a for the experimental geometry). Circularly polarized ps laser pulses with photon energies of 1.41 eV near the fundamental band edge of InGaAs are used to initiate the electron spin polarization Sz(0) at t = 0 ns pointing along +z and −z directions for σ+ and σ− polarizations, respectively27. The sample is subject to an external static magnetic field B∥x. The generated AC electric current is probed through high frequency contacts by a sampling oscilloscope14,15.

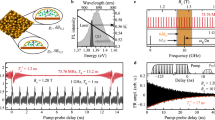

a Sample geometry and pulsed optical spin excitation. The electron spin ensemble is excited along the z direction by circularly polarized ps laser pulses with a pulse repetition time of 12.5 ns. The high-frequency current in InGaAs is detected by a phase-triggered sampling oscilloscope through coplanar waveguides (CPW). Four different crystal directions can be contacted. b Illustration of the spin precession driven trembling electron motion (PDTM). Electron spin precession yields a periodic displacement of the electrons along the x-direction which results in an AC current oscillating at the Larmor frequency. c Time-resolved current traces along the [110] crystal direction recorded after pulsed optical excitation for σ+ and σ− polarizations at Bx = 1 T and T = 50 K and averaged over about 105 measurements. The inset shows a close-up of both current traces. d Time-dependent AC current Ispin = [I(σ+) − I(σ−)]/2 as determined from both traces in panel (c). A fit to Eq. (1) yields a spin dephasing time of \({T}_{2}^{* }=1.8\) ns. e TRFR of electron spin precession under identical experimental conditions. f Illustration of AC current generated by the spin-galvanic effect (SGE), where the largest currents are generated for electron spins pointing along the ±y-directions. g and h show respective AC current and TRFR traces measured along the \([1\overline{1}0]\).

After optical excitation of an unbiased sample by circularly polarized pulses we detect an AC electric current at GHz frequencies. The time-resolved current signal measured at T = 50 K along the B field direction (Bx = 1 T) parallel to the [110] crystal axis is shown in Fig. 1c for σ+ and σ− excitation. For short t, it is dominated by a spin-independent background which decays on the electron-hole recombination time of about 100 ps and is followed by some circuit ringing due to internal reflections in the high frequency transmission line. A spin-polarization-driven AC current is already visible in this data as subtle periodic differences between both curves which is shown in the close-up region in Fig. 1c. We can enhance the visibility of the spin-dependent signal by plotting Ispin = [I(σ+) − I(σ−)]/2 in Fig. 1d. An oscillating current is clearly visible. It extends over several ns after the laser-induced non-equilibrium electron-hole population has recombined indicating that the spin angular momentum has been transferred to the resident electron ensemble. The current oscillations follow the Larmor precession of the electron spins as seen from time-resolved pump-probe Faraday rotation (TRFR) data in Fig. 1e measured under identical experimental conditions. Furthermore, both traces follow the same temporal decay showing that the same spin states are probed by both techniques. While Larmor spin precession of optically generated spin packets has routinely been probed by time-resolved optical techniques28,29,30,31, it has never been measured in the time-domain by electrical means.

The AC current trace in Fig. 1d can be fitted by an exponentially decaying cosine function

to extract the current amplitude I0, the spin dephasing time \({T}_{2}^{* }\) and the respective phase ϕ, with the Larmor frequency ωL = gμBB/ℏ determined by the electron g-factor ∣g∣ = 0.62. We note that the AC current in Fig. 1d is in phase (ϕ = 0°) with the z-component of the spin polarization which is directly probed by TRFR (for comparison of the relative phases see dotted lines in Fig. 1d, e).

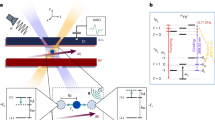

To further explore the dependence of the spin-driven AC current on Bx, we show a series of measurements at selected B fields in Fig. 2a. It is apparent that both the frequency ωL and the amplitude I0 increase with increasing B field strength (see also Fig. 2b). Starting from Bx = 0.05 T, when the oscillations become visible, the current frequency scales linearly with Bx and coincides with the spin precession frequency seen in TRFR measurements. At large Bx = ± 3 T the spin precession frequency reaches f = 26 GHz (see Fig. 2a). Remarkably, the amplitude I0 of the AC current also increases linearly with Bx (deviations at small and at large B fields are discussed further below). This is in contrast to the spin dynamics studied by TRFR, where the signal amplitude is a measure of the total spin density which is independent of B, i.e. the spin precession frequency. When reversing the B field direction, I0 changes sign indicating that the AC current generation depends on the spin precession direction which changes from clockwise to counterclockwise upon B field reversal. The extracted spin dephasing time is 2.9 ns at Bx = 125 mT and reduces to 1 ns at Bx = 3 T. This magnetic field dependent spin dephasing at low temperatures is in line with previous studies28,32.

a Time-resolved current along the [110] direction in InGaAs at various B fields. The data are offset vertically for clarity. Larmor precession frequency and magnitude of AC current increase with increasing B field strength while the sign of the AC current reverses when reversing the B field direction. b Amplitude I0 of AC current vs Bx. The linear increase of I0 with Bx indicates a strong PDTM with a weak SGE visible at small Bx. The red solid line is a fit to Eq. (3). c I0 vs Bx for a sample measured along the \([1\overline{1}0]\) direction. The weak increases of I0 with increasing ∣Bx∣ indicate the dominance of SGE over PDTM.

Periodic trembling motion of electrons

All these findings suggest that the precessing spin polarization drives the AC charge current, i.e. it triggers a periodic trembling motion of the electrons. A direct coupling between the electron spin and velocity is indeed possible in semiconductor structures with k-linear SOI2. Here, we use n-InGaAs epilayers which exhibit both the Dresselhaus SOI due to strain by lattice mismatch to the subjacent Si-GaAs substrate and the Rashba-like SOI due to partial strain relaxation33. Semi-classical theory20 suggests that a pulsed optical excitation by circularly polarized light in an external in-plane magnetic field may lead to spin-related charge current oscillations. The theory is based on the effective electron Hamiltonian

where m* is the effective mass, βxy and βyx are the constants originating from Rashba/Dresselhaus SOI in (001)-oriented structures, σi are the Pauli spin matrices, and x and y are the in-plane axes. The current contains two contributions. The first one emerges due to the spin relaxation of polarized electrons and is governed by the relaxation rate \({\boldsymbol{S}}(t)/{T}_{2}^{* }\). This effect, known as the spin-galvanic effect (SGE), was observed and studied experimentally under steady-state photoexcitation in GaAs-based quantum wells16,34. The second contribution can be referred to as precession driven trembling motion (PDTM). It emerges due to the dynamic precession of the spin polarization vector in a magnetic field and is governed by the vector product ωL × S(t). In (001)-oriented structures, the SGE current is driven by the in-plane spin component, i.e. it changes sign when reversing the in-plane spin direction from the + y to − y orientation (see Fig. 1f) and its amplitude ISGE does not depend on Bx16,34. As the AC charge current in Fig. 1d becomes largest when electron spins are oriented in the out-of-plane direction along the z-axis and its amplitude linearly increases with Bx, it cannot result from the SGE. We note, however, that we also observe the SGE in our time-resolved AC charge current measurements. This is most clearly seen along the \([1\overline{1}0]\) direction where we observe the expected phase difference of (ϕ ~ π/2) between the respective Larmor precessions in the AC charge current in Fig. 1g and the TRFR in Fig. 1h proving the AC charge current is generated by in-plane spins. As expected for the SGE, the respective current amplitudes are roughly independent on ∣Bx∣ and change sign when reversing the magnetic field direction (Fig. 2c).

Because of the π/2 phase difference between the SGE and PDTM currents their amplitudes, ISGE and IPDTM = KPDTMBx, respectively, add quadratically to the AC current amplitude

where KPDTM is the strength of PDTM. This equation describes well the data measured along both crystal directions shown in Fig. 2. While the PDTM dominates over the SGE for the [110] sample Fig. 2b it is the opposite for the \([1\overline{1}0]\) sample in Fig. 2c. The slight deviation from the expected linear behavior at large magnetic fields in Fig. 2b, i.e. at large precession frequencies is due to the limited band-width of our device (3 db point at 13 GHz).

We next explore how KPDTM depends on the SOI. The crystal axis anisotropy of the SOI gives us a set of devices from the same wafer with different βyx (Supplemental Material). For measuring βyx we use the TRFR pump-probe technique and apply an additional DC current I which converts into an internal magnetic field Bint ∝ I12,13. From the change in the spin precession frequency we determine βyx for each device and find both Rashba and Dresselhaus contributions leading to highly anisotropic SO fields. We conducted measurements on seven devices along four crystal directions (see Fig. 1a) and extracted the respective KPDTM and βyx values which are summarized in Fig. 3. Despite a certain device-to-device variation along the same crystal direction, we clearly observe an overall linear dependence of KPDTM on βyx demonstrating that the SO coupling plays the key role for the emergence of the PDTM.

Quantum-mechanical picture

While the AC current dynamically generated by electron spin precession can be understood semiclassically as outlined above, we now present a quantum-mechanical picture as a result of coherent electron Zitterbewegung triggered by optical pulses35 which results in a trembling motion of electrons at the Larmor frequency of the precessing electron spin ensemble. This interpretation originates from the fact that the electron velocity is not a conserved quantity in the presence of the Zeeman gap and spin-orbit interaction. Indeed, besides the first term of spin-independent kinetic energy, the effective Hamiltonian 2 mimics the Dirac Hamiltonian with all essential elements: it comprises the SOI term which provides a k-linear coupling of the states and the Zeeman term which opens a gap at k = 0 and plays a role of the mass term in the Dirac Hamiltonian.

Calculating the electron velocity operator vx = (i/ℏ)[H, x], where [A, B] = AB − BA is the commutator of the operators A and B, and then the acceleration operator \({\dot{v}}_{x}=(i/\hslash )[H,{v}_{x}]\), we obtain to first order in SOI

In our InGaAs samples, the electron transport is diffusive rather than ballistic and we deal with an ensemble of about 108 electrons. To describe the macroscopic motion of the electrons we average Eq. (4) over the electron ensemble. Since Eq. (4) is linear, this leads to the replacement of the operators vx and sz by their average values \({\bar{v}}_{x}\) and \({\bar{s}}_{z}\). Besides, to account for electron scattering by phonons or static defects, which randomizes electron trajectories and slows down the average electron velocity, we add a Drude-like term and obtain

where τp is the momentum scattering time. It is assumed that \({T}_{2}^{* }\gg 1/{\omega }_{L},{\tau }_{p}\) with \({T}_{2}^{* }\) being the spin dephasing time.

The AC charge current density caused by the PDTM of the electrons is given by \({j}_{x}^{(ac)}(t)=e{n}_{e}{\bar{v}}_{x}(t)\), where e is the electron charge and ne is the electron density. For the case ωLτp ≪ 1, which is realized in our experiments, the solution of Eq. (5) yields

As it follows from Eq. (6), the amplitude of the PDTM current which is determined by KPDTM, scales linearly with the SO coupling constant βyx (see Fig. 3). We note that the coupling of the macroscopic current density to the average spin given by Eq. (6) was previously derived by a sophisticated spin-density-matrix approach in ref. 20. Here, we have shown the quantum-mechanical derivation of this result and uncover its relation to the physics of Zitterbewegung explaining our experimental findings.

For illustration, we depict in Fig. 1b the temporal evolution of the spin vector \(\bar{s}(t)\) during spin precession and the predicted AC charge current according to Eq. (6). Spin precession and trembling movement are in phase, i.e., the largest current along the +x direction is obtained when the spin is pointing along +z (red arrow). The current becomes zero at the spin rotation angle π/2 (Sz = 0, see yellow arrow in Fig. 1b), changes the sign for larger angles, and again becomes strongest along the − x direction for the angle π (green arrow). The PDMT current exhibits one distinct frequency which linearly increases with increasing magnetic field strength, despite the randomized electron momenta present in the diffusive transport regime. For B ≠ 0, the spin projection \({\bar{s}}_{z}(t)\) oscillates at the Larmor frequency ωL and so does the electron velocity – which results in the AC charge current – even though no driving electric field is applied. We note that the current amplitude estimated from Eq. (6) for the sample parameters determined independently (τp = 157 fs was determined from measurements of the electron mobility at 50 K; see also Supplemental Material) I0 ~ 0.2 μA is in agreement with the experimental data.

Discussion

We have shown that electrons in III-V semiconductors with spin-orbit coupling experience an inherent trembling motion of quantum-mechanical nature. The trembling motion (Zitterbewegung) of individual electrons can be phase-synchronized by initializing the electrons in the same spin states and detected as an AC current oscillating at the Larmor frequency of several GHz. The use of pulsed optical excitation combined with time-resolved electrical detection in systems with rather small Zeeman splitting provides a promising pathway for exploring trembling motion in other solid state systems. Additionally, the spin-driven AC currents can be utilized as an ultrafast spin sensitive electrical probe of electron spin precession where the detection scheme is solely based on SO interaction free of any additional spin-sensitive magnetic materials. We expect that spin-orbit-driven high frequency currents can also be explored in other materials including topological insulators with inherent Dirac-like spectrum and other 2D materials with strong spin-orbit interaction and short spin lifetimes.

Methods

Sample fabrication

An n-doped In0.07Ga0.93As epilayer was grown via molecular beam epitaxy on a semi-insulating (001) GaAs substrate, with a doping concentration of 8.25 × 1016 cm−2. The epilayer was lithographically patterned into pentagonal structures, and ohmic contacts were formed by depositing Ge/Au/Ni stacks, followed by rapid thermal annealing at 400 °C.

High-frequency measurement setup

For broadband electrical measurements, the samples were mounted on custom-designed printed circuit boards (PCBs) incorporating 50 Ω coplanar waveguides (CPWs). The CPWs were fabricated on RO3210 laminate using UV lithography and wet etching. Electrical coupling between the InGaAs channels and CPWs was achieved using three short Al bonding wires. The CPWs were connected to high-frequency coaxial cables via impedance-matched SMA launchers and linked to a 26 GHz bandwidth amplifier with 35 dB gain.

Optical excitation and detection

Phase-coherent spin ensembles in the InGaAs layer were excited using circularly polarized 3 ps laser pulses generated by a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser (SPECTRA PHYSICS Tsunami) operating at a repetition rate of 80 MHz. The polarization of the pump beam was switched between σ+ and σ− using a liquid crystal variable retarder. For time-resolved electrical detection we recorded the electrical signal by a fast sampling oscilloscope (Tektronix DSA 8200), phase-locked to the laser pulses via a fast photodiode, ensuring precise temporal resolution of the GHz-range oscillatory voltage signals.

For time-resolved Faraday rotation (TRFR), a second, linearly polarized probe beam was used to monitor spin precession. The TRFR signal was detected with a balanced photodiode bridge and demodulated using lock-in amplifiers for enhanced sensitivity. For details of the optical setup see Section 6 of the Supporting Information of ref. 36. All measurements were conducted in a helium bath cryostat (OXFORD, Spectromag) with magnetic fields applied along the in-plane sample axis.

Data availability

The data that support the findings within this paper are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15968129.

References

Awschalom, D. & Samarth, N. Trend: spintronics without magnetism. Physics 2, 50 (2009).

Ivchenko, E.L. & Ganichev, S.D. Spin-Photogalvanics, 281–327 (Springer, 2017).

Kato, Y. K., Myers, R. C., Gossard, A. C. & Awschalom, D. D. Current-induced spin polarization in strained semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 176601 (2004).

Silov, A. Y. et al. Current-induced spin polarization at a single heterojunction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 5929–5931 (2004).

Ganichev, S. D. et al. Electric current-induced spin orientation in quantum well structures. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 300, 127–131 (2006).

Stern, N. P. et al. Current-induced polarization and the spin Hall effect at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 126603 (2006).

Dyakonov, M. I. & Khaetskii, A. V. Spin Hall Effect, 241–280, (Springer, 2017).

Kato, Y. K., Myers, R. C., Gossard, A. C. & Awschalom, D. D. Observation of the spin Hall effect in semiconductors. Science 306, 1910–1913 (2004).

Wunderlich, J., Kaestner, B., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Experimental observation of the spin-Hall effect in a two-dimensional spin-orbit coupled semiconductor system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 047204 (2005).

Stern, N. P., Steuerman, D. W., Mack, S., Gossard, A. C. & Awschalom, D. D. Time-resolved dynamics of the spin Hall effect. Nat. Phys. 4, 843 (2008).

Kalevich, V. K. & Korenev, V. L. Effect of electric field on the optical orientation of 2d electrons. JETP Lett. 52, 230 (1990).

Kato, Y., Myers, R. C., Gossard, A. C. & Awschalom, D. D. Coherent spin manipulation without magnetic fields in strained semiconductors. Nature 427, 50–53 (2004).

Meier, L. et al. Measurement of Rashba and Dresselhaus spin-orbit magnetic fields. Nat. Phys. 3, 650–654 (2007).

Stepanov, I., Kuhlen, S., Ersfeld, M., Lepsa, M. & Beschoten, B. All-electrical time-resolved spin generation and spin manipulation in n-InGaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 062406 (2014).

Kuhlen, S. et al. Electric field-driven coherent spin reorientation of optically generated electron spin packets in InGaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 146603 (2012).

Ganichev, S. D. et al. Spin-galvanic effect. Nature 417, 153–156 (2002).

Werake, L. K., Ruzicka, B. A. & Zhao, H. Observation of intrinsic inverse spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 107205 (2011).

Schmidt, C. B., Priyadarshi, S., Tarasenko, S. A. & Bieler, M. Ultrafast magneto-photocurrents in GaAs: separation of surface and bulk contributions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 142108 (2015).

Schreiber, L. R. et al. Triggering phase-coherent spin packets by pulsed electrical spin injection across an Fe/GaAs Schottky barrier. Phys. Rev. B 104, 195202 (2021).

Ivchenko, E. L., Lyanda-Geller, Y. B. & Pikus, G. E. Current of thermalized spin-oriented photocarriers. Sov. Phys. JETP 71, 550 (1990).

Schrödinger, E. Über die kräftefreie Bewegung in der relativistischen Quantenmechanik. Sitz. Press. Akad. Wiss. Phys. Math. 24, 418–428 (1930).

Zawadzki, W. & Rusin, T. M. Zitterbewegung (trembling motion) of electrons in semiconductors: a review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 143201 (2011).

Schliemann, J., Loss, D. & Westervelt, R. M. Zitterbewegung of electronic wave packets in III-V zinc-blende semiconductor quantum wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 206801 (2005).

Biswas, T. & Ghosh, T. K. Zitterbewegung of electrons in quantum wells and dots in the presence of an in-plane magnetic field. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 24, 185304 (2012).

Winkler, R., Zülicke, U. & Bolte, J. Oscillatory multiband dynamics of free particles: the ubiquity of zitterbewegung effects. Phys. Rev. B 75, 205314 (2007).

Manchon, A., Koo, H. C., Nitta, J., Frolov, S. M. & Duine, R. A. New perspectives for Rashba spin–orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 14, 871 (2015).

Meier, F. & Zakharchenya, B.P. Optical Orientation. Elsevier, Amsterdam https://www.sciencedirect.com/bookseries/modern-problems-in-condensed-matter-sciences/vol/8 (1984).

Kikkawa, J. M. & Awschalom, D. D. Resonant spin amplification in n-type GaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 4313–4316 (1998).

Heberle, A. P., Rühle, W. W. & Ploog, K. Quantum beats of electron Larmor precession in GaAs wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3887–3890 (1994).

Sih, V. et al. Mechanical control of spin-orbit splitting in GaAs and In0.04Ga0.96As epilayers. Phys. Rev. B 73, 241316 (2006).

Greilich, A. et al. Mode locking of electron spin coherences in singly charged quantum dots. Science 313, 341–345 (2006).

Beschoten, B. et al. Spin coherence and dephasing in GaN. Phys. Rev. B 63, 121202 (2001).

Bernevig, B. A. & Zhang, S.-C. Spin splitting and spin current in strained bulk semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 72, 115204 (2005).

Ganichev, S. D. et al. Spin-galvanic effect due to optical spin orientation in n-type GaAs quantum well structures. Phys. Rev. B 68, 081302 (2003).

Tarasenko, S. A. et al. Zitterbewegung of spin split electrons. JETP Lett. 108, 326–328 (2018).

Ersfeld, M. et al. Unveiling valley lifetimes of free charge carriers in monolayer WSe2. Nano Lett. 20, 3147–3154 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Güntherodt and F. Volmer for helpful discussions, S. Pissinger for initial work on time-resolved photo-current measurements, and S. Staacks for help on the figures. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy - Cluster of Excellence Matter and Light for Quantum Computing (ML4Q) EXC 2004/1 – 390534769 and by RSF grant 22-12-00211-Π.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.B. conceived and supervised the project. I.S. and M.E. fabricated the devices and performed all time-resolved measurements. I.S. analyzed the data. A.P., E. I. and S.T. provided the theory. M.L. deposited the n-InGaAs epilayer by MBE. I.S., S.T. and B.B. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stepanov, I., Ersfeld, M., Poshakinskiy, A. et al. Trembling motion of electrons driven by Larmor spin precession. npj Spintronics 3, 52 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00117-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00117-9