Abstract

Spin torque nano-oscillators have received continuously increasing attention due to their rich dynamics and potential applications. Here, we propose a spin torque nano-oscillator based on a ferrimagnetic skyrmion lattice, where the weak Magnus forces together with intriguing skyrmion-skyrmion interactions allow current-driven skyrmions to oscillate at terahertz frequencies. Through micromagnetic simulations, we demonstrate that a small current injection area results in identical motion orbits for the oscillating skyrmions, while a large injection area yields distinct or even chaotic trajectories. We analyze the transition between identical and distinct orbits using the Thiele equation, which also explains the parameter dependence of the oscillator frequency. In addition, synchronized oscillation signals emitted from a single oscillator are demonstrated. Our results not only reveal the high-frequency oscillation dynamics of ferrimagnetic skyrmions, but also pave the way for developing skyrmion-based oscillators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spin torque nano-oscillators, capable of generating persistent oscillatory signals through current-induced spin torque fully compensating the system dissipation, have attracted considerable attention due to their intriguing dynamics and important applications in microwave communication and neuromorphic computing1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. To date, various nano-oscillators based on magnetic textures, including uniform magnetizations1,12,13,14,15, vortices4,7,16,17,18, droplets19,20,21,22,23,24, bimerons25 and skyrmions26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, have been proposed. Among these, skyrmion-based nano-oscillators are expected to deliver enhanced output power and reduced linewidth26. However, reported designs typically allow skyrmion oscillations only at moderate frequencies—often below 40 gigahertz (GHz)26,27,28,30,31.

In ferromagnetic skyrmion oscillators, this frequency limitation stems mainly from the difficult-to-balance Magnus force acting on the moving skyrmion. In contrast, antiferromagnetic skyrmion oscillators require an additional strong force to act as the velocity-dependent centripetal force28. Recent theoretical studies have demonstrated that the Magnus force in ferrimagnetic skyrmions is highly tunable37,38, making it a promising mechanism for providing a suitable centripetal force. This finding opens up new possibilities for achieving high-frequency skyrmion oscillations.

In general, the implementation of most proposed skyrmion oscillators requires the generation of a single skyrmion or a given number of skyrmions at a specified location in the nanoscale magnetic layer26,27,28,30,31,37,38,39, which increases fabrication complexity and cost. However, skyrmions in magnetic materials often naturally form lattices, such as triangular lattices40,41,42,43. These skyrmion lattices inherently exhibit skyrmion-skyrmion interactions, making them ideal for supporting rotational motion along well-defined orbits. While temperature-gradient driven rotation of skyrmion lattices has been reported44, the dynamics under localized driving current injection remain unexplored, which greatly motivates the present work.

In this study, we use micromagnetic simulations to investigate the dynamics of ferrimagnetic skyrmion oscillators with a skyrmion lattice as the initial state. We find that such ferrimagnetic skyrmions can oscillate at terahertz (THz) frequencies, exhibiting identical, distinct, or even chaotic motion trajectories, depending on the current injection areas. Theoretical analysis based on the Thiele equation explains the parameter dependence of oscillator frequency and the transition of the skyrmion trajectories. We also show that multiple skyrmions within a single oscillator can produce synchronized oscillation signals, offering a pathway toward high-power THz signal generation.

Results and discussion

Theoretical model

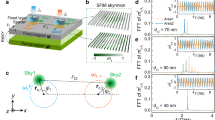

The geometry of our ferrimagnetic skyrmion oscillator is depicted in Fig. 1a, where the magnetic working layer is a ferrimagnet with a regular skyrmion lattice, stabilized by the interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI)45,46 induced by the heavy metal. A circular current injector with diameter Dj, placed on top of the ferrimagnet, drives the skyrmion dynamics through current-induced spin transfer torques47,48, which can also be used to electrically read out the skyrmion oscillations and may influence the properties of the working layer, with limited effects expected49. We use the micromagnetic simulation package MUMAX350 to study the current-induced dynamics. The simulation details and relevant material parameters are provided in the Methods and Supplementary Note 1. The obtained snapshots of the Néel vector n = (m1 − m2)/2 (with the reduced magnetizations m1(2)) and skyrmion trajectories are shown in Fig. 1b,c, respectively. As seen, the skyrmions (labeled S1 and S2) driven directly by the current perform a nearly circular motion, where the boundary of the current injection area is illustrated by a dashed circle in Fig. 1b. From the time evolution of the skyrmion location shown in Fig. 1d, we find that the oscillator’s output frequency f reaches a relatively high value of ~ 49 GHz.

a Schematic of the proposed nano-oscillator comprising a ferrimagnet with a regular skyrmion lattice. The heavy metal underneath the ferrimagnet induces Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction to stabilize the skyrmions, while the circular current injector with diameter Dj is used to excite the skyrmion dynamics. b Snapshots of the skyrmion configurations at two different simulation times. The skyrmions driven directly by the current are labeled as S1-S2, with the edge of the current injector indicated by the green dashed circle. The black (white) areas denote the Néel vector along − z (+ z), and the colors indicate the in-plane orientation. c Skyrmion trajectories and d the x-component of the location (xc) of skyrmions S1 and S2. Skyrmion trajectories are obtained by recording the evolution of the coordinates of the grid points with nz ~ − 1. e Force analysis of the skyrmions. Fjφ and Fjr are the azimuthal and radial current-induced forces, respectively. Fα, Fss, and G × vc denote the frictional force, the skyrmion-skyrmion interaction force, and the Magnus force, respectively.

To understand the mechanisms behind the high-frequency skyrmion oscillation, we employ the Thiele equation38,51,52,53,54 to analyze the forces acting on the skyrmions. According to previous works37,55, the Thiele equation of the ith ferrimagnetic skyrmion reads:

where meff is the effective mass and rc = (xc, yc) is the position coordinate of the skyrmion center, which can be defined by averaging the topological density ρt of the magnetic structure, i.e., rc = ∫rρtdxdy/∫ρtdxdy with ρt = 1/(4π)n ⋅ (∂xn × ∂yn)56. The term \({\bf{G}}\times {\mathop{{\bf{r}}}\limits^{\cdot }}_{{\rm{c}}}\) stands for the Magnus force with the gyrovector G57,58. \({{\bf{F}}}_{\alpha }=-\alpha L{\mathop{{\bf{r}}}\limits^{\cdot }}_{{\rm{c}}}\) is the frictional force with the damping constant α and dissipation coefficient L. Fj = − (jℏP/e)u is the current-induced force with j being the current density, ℏ the reduced Planck constant, P the spin polarization efficiency and e the elementary charge55. \({u}_{i}={\int }_{{\rm{A}}}\left({\bf{n}}\times {\bf{p}}\right)\cdot {\partial }_{i}{\bf{n}}dxdy\) with i = x, y is related to the polarization vector (p) and the current injection area (A). The last term of the Thiele equation Fss is the repulsive force between skyrmions37,59,60. These forces are schematically depicted in Fig. 1e with the subscript φ (r) indicating the azimuthal (radial) component of forces, while more details of them are provided in the Methods.

The radial force balance suggests that the realization of high-frequency oscillation requires a relatively weak Magnus force \({\bf{G}}\times {\mathop{{\bf{r}}}\limits^{\cdot }}_{{\rm{c}}}\) acting on the high-speed skyrmion, as the other radial forces, Fss and Fjr, are not directly related to the skyrmion velocity. The reduction of Magnus force here is achieved using the unique properties of ferrimagnet. Specifically, the opposite and different magnetic moments on the two sublattices of the ferrimagnet give rise to a small value of G ∝ (Ms1/γ1 − Ms2/γ2) with the saturation magnetization Ms1(2) and gyromagnetic ratio γ1(2)38,58.

From the azimuthal force balance, i.e., Fα + Fjφ ≈ 0, we derive the frequency (f) of the skyrmion oscillators

where Nsky = 2 is the number of rotating skyrmions26 and Rc is the orbit radius.

Parameter dependence of skyrmion dynamics

Figure 2a-c compare the frequencies obtained from simulations and Eq. (2) with different values of the current density j, saturation magnetization Ms2, and damping constant α. The results of Eq. (2) with numerical Fjφ and Rc (see Supplementary Fig. 2) agree well with those from the simulations. As shown in Fig. 2a, the frequency exhibits a non-monotonic behavior with increasing current. This is due to the non-monotonic variation of the driving force Fjφ induced by the change in orbit radius Rc (Supplementary Fig. 2). Note that small currents (j < 15 MA cm−2) cannot sustain persistent skyrmion oscillation, while large currents (> 250 MA cm−2) lead to the annihilation of the skyrmions. As the saturation magnetization Ms2 is increased from 670 to 730 kA m−1, we also observe a non-monotonic change in the frequency [see Fig. 2b]. This can be understood from the fact that when increasing Ms2 (with fixed Ms1 = 709 kA m−1), the Magnus force weakens and even reverses at the angular momentum compensation point (G = 0), which results in the skyrmions S1 and S2 moving away from each other hence tracing out a larger orbit. As shown in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 2, the increased orbit radius yields a non-monotonic driving force, explaining the non-monotonic relation between Ms2 and f. In Fig. 2c, one may notice that the oscillation frequency increases as the damping decreases, which is attributed to the improvement in driving efficiency at low magnetic damping, as expected from Eq. (2). More importantly, the calculation results demonstrate that the frequency of our proposed oscillator can reach about 0.2 THz, which is much higher than that of other skyrmion-based oscillators (see Supplementary Note 3 for the details of frequency comparisons)28,30,31,37. When the damping is reduced to 0.001, the skyrmion trajectory becomes irregular [see Fig. 2d] and the orbit radius changes over time [Fig. 2e], corresponding to multi-frequency oscillations, as observed in the frequency spectrum in the inset of Fig. 2d. The formation of such a trajectory originates from the change in skyrmion size during their rotation, as shown in Fig. 2f; details of the skyrmion dynamics are provided in Supplementary Movie 1. Additionally, the influences of the defects, Oersted fields and local anisotropy variations on skyrmion dynamics are discussed in the Supplementary Information.

Dependence of the skyrmion oscillation frequency on a the current density j, b saturation magnetization Ms2 and c damping constant α. Solid circles represent analytical results from the Thiele equation; open circles indicate simulation results. Default parameters: j = 50 MA cm−2, Dj = 40 nm, Ms1 = 709 kA m−1, Ms2 = 705 kA m−1 and α = 0.01. d Trajectories and e x-component of the location (xc) of skyrmions S1 and S2 with α = 0.001. The inset in d shows the Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of xc(t). f A sequence of snapshots of the skyrmions.

a Injector diameters Dj = 45 nm, b 46 nm and c 70 nm. d Azimuthal current-induced forces Fjφ as a function of orbit radius Rc for different injector diameters Dj. Symbols represent numerical results; solid curves are fitted expressions. e Dependence of parameter b on Rc with different values of Dj. f Fast Fourier transform of xc(t) for Dj = 70 nm, showing a broad spectrum characteristic of chaos.

We next examine how the current injector diameter Dj affects the skyrmion dynamics. Figure 3a-c depict the time evolution of the skyrmion trajectories for injector diameters Dj = 45, 46 and 70 nm, respectively. Here, we take the magnetic structure shown in Fig. 1b as the initial state, with the horizontal distance between the centers of adjacent skyrmions being 50 nm. With Dj = 45 nm, skyrmions S1 and S2 move in orbits with the same radius. However, for a slightly larger injector with Dj = 46 nm, their orbits have different radii. To analyze the transition between the two distinct trajectories presented in Fig. 3a,b, we derive the equation for the orbit radii of the skyrmion S1 and S2 (see Supplementary Note 2 for derivation details), described as

where Fssr is the radial component of the skyrmion-skyrmion interaction force. For simplicity, we treat (Fjr + Fssr) in Eq. (3) as a constant, since Fjφ is the dominant term over Fjr and Fssr. Thus, the solution of Eq. (3) requires the acquisition of parameter b, more specifically, specifying the expression of Fjφ with respect to Rc and Dj. In order to obtain Fjφ(Rc), we perform micromagnetic simulations with a ferrimagnetic skyrmion undergoing centrifugal motion driven by the current, following our previous work55. Such a centrifugal motion is achieved by setting a relatively large value of Ms2 = 720 kA m−1. Based on the magnetic structures of skyrmion during centrifugal motion, we compute the driving forces Fjφ with different values of Dj and fit them using the formula \({F}_{j\varphi }={k}_{1}\exp \{-{[{({R}_{{\rm{c}}}-{D}_{j}/2)}^{2}/{k}_{2}]}^{{k}_{3}}\}\) with k1 = 32.78 × 10−13 N, k2 = 37 nm2 and k3 = 0.728, as shown in Fig. 3d. It can be seen that the Fjφ(Rc) curves exhibit a simple horizontal shift as Dj changes. With the above expression of Fjφ and the value of (Fjr + Fssr) ~ 1.48 × 10−13 N at Dj = 45 nm, we plot the parameter b in Fig. 3e with different values of Dj. As seen, once Dj is greater than ~ 46 nm, the parameter b no longer intersects with Rc, resulting in the breakdown of Eq. (3) and therefore the occurrence of a transition in the skyrmion trajectories. As shown in the Supplementary Fig. 5, identical and distinct skyrmion trajectories can be found at certain locations of the injector center. Note that for the case Dj = 40 nm in Fig. 3e, there are two intersection points: one corresponds to a stable orbit and the other to an unstable fixed point38.

More interestingly, at Dj = 70 nm, the number of skyrmions directly driven by current increases from two to three (S1-S3), and the skyrmion trajectories show no regularity at all [see Fig. 3c], suggesting the emergence of chaos. To confirm the chaotic trajectories, we perform a Fast Fourier transform of the skyrmion position [Fig. 3f], revealing a broadband, noise-like frequency spectrum characteristic of chaos55,61. For a more precise validation of chaotic trajectories, we calculate the Lyapunov exponent of xc(t) of skyrmion S1 using the method proposed by Rosenstein et al.62, and indeed find a positive Lyapunov exponent of ~ 2.1 ns−1 as a signature of chaos. Additional details of the skyrmion dynamics in the above three cases with Dj = 45, 46 and 70 nm are provided in Supplementary Movie 2-4, respectively.

Extension to many-skyrmion oscillations

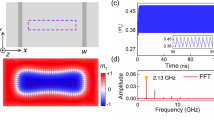

In this section, we further expand the current injection area in micromagnetic simulations to demonstrate many-skyrmion oscillations and provide a promising method to improve the power output of skyrmion oscillators. A rectangular strip-shaped injector (460 × 40 nm2) [see Fig. 4a], smaller than the ferrimagnet’s top surface (500 × 200 nm2), is used to induce multiple well-defined skyrmion trajectories. When the current is applied to the injector, the skyrmions in the middle region of the ferrimagnet rotate counterclockwise around the injection area, as indicated by the green arrows in Fig. 4b. While the detailed dynamics of skyrmions can be seen in Supplementary Movie 5, we plot the skyrmion trajectories in Fig. 4c. The ferrimagnetic skyrmion oscillations can be detected using similar magnetoresistance measurements that have been utilized for ferromagnets49,63,64, thanks to the property of ferrimagnets with two inequivalent sublattices65. The magnetoresistance actually reflects the magnetizations of output regions. Specifically, if the detector and the ferrimagnetic working layer form a magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ), the MTJ resistance can be described as RMTJ = RP + (RAP − RP)(1 − nz)/2 for the magnetizations of the fixed layer of the detector along the z direction, with RP (RAP) being the resistance of parallel (antiparallel) state of the MTJ66. Here we take seven equally spaced regions as output areas [black squares in Fig. 4b, O1-O7] and present the recorded out-of-plane Néel vector nz of these areas in Fig. 4d with different spacings d of output areas. The sum of nz of all output regions is plotted in Fig. 4e with As representing the oscillation amplitude. It can be seen that the total amplitude (As) is much larger than that of a single output area (~ 0.5), thus yielding an improved power output \({P}_{\mathrm{out}}\propto |{A}_{{\rm{s}}}{|}^{2}\)67. Figure 4f summarizes the variation of As with the spacing d. As seen, As reaches a maximum value of about 3.5 at d = 56 nm. Such a spacing actually corresponds to the horizontal distance between the centers of adjacent skyrmions, at which the O1-O7 areas output almost synchronized signals, as shown in Fig. 4d. Note that unlike the common methods that use multiple synchronized oscillators to increase the power output2,6,8,13,14,67,68,69,70,71, our proposal involves only one oscillator with multiple oscillating units (i.e., skyrmions) and detection areas, which offers a potential way to obtain synchronized oscillation signals. It should be emphasized here that while two different oscillators can be synchronized (see Supplementary Fig. 8), our purpose is to use a single oscillator with a common skyrmion lattice to improve the output signal with a relatively high frequency. Although the skyrmion lattice is unstable at room temperature for the parameters used in this work, our proposal can be extended to synthetic ferrimagnetic systems with excellent thermal stability, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. Note that if there are ferromagnetic materials with skyrmion modes at THz frequencies72, exciting these modes may also produce high-frequency oscillating outputs.

a Geometry of the many-skyrmion oscillator using a strip-shaped current injector (460 × 40 nm2) placed on the ferrimagnet (500 × 200 nm2). b Magnetic structure at simulation time t = 4 ns. Seven black squares (labeled O1-O7) with equal spacing d and the same size 5 × 5 nm2 indicate the output areas. The green arrows describe the rotation direction of the skyrmions. c Skyrmion trajectories. d The z-component nz of the Néel vector in the regions O1-O7 and e the sum of nz of all output regions, with different spacings d. f Amplitude As of the sum of nz with different values of d.

In summary, we theoretically investigate a ferrimagnetic spin torque nano-oscillator leveraging a skyrmion lattice as its functional core. The weak Magnus force inherent to ferrimagnets enables oscillation frequencies up to 0.2 THz. Through micromagnetic simulations and analytical modeling via the Thiele equation, we comprehensively study the dependence of the skyrmion dynamics on system parameters. We further demonstrate the emergence of distinct, identical, and chaotic skyrmion trajectories depending on the current injection area and damping. Finally, we propose a many-skyrmion oscillator configuration that significantly enhances the output power through synchronized signal detection. These results not only deepen our understanding of high-frequency skyrmion dynamics but also offer practical guidance for the design of next-generation THz spintronic oscillators.

Methods

Micromagnetic simulations

In this work, we consider a monolayer ferrimagnet whose sublattices have different magnetizations M1 and M2. The simulations of ferrimagnetic skyrmion dynamics are carried out by using micromagnetic software MUMAX350 to numerically solve the equation of motion for the reduced magnetizations (mi = Mi/Msi with the saturation magnetization Msi)

where the subscript i = 1, 2 is used to distinguish the two sublattices of ferrimagnet. \(\mathop{{\bf{m}}}\limits^{\cdot }\) is the derivative of m with respect to time. γ and α denote the gyromagnetic ratio and the magnetic damping, respectively. Heff stands for the effective field, including the exchange field, the DMI field and the anisotropy field. p represents the polarization vector and Hi = jℏP/(2μ0etzMsi) is the strength of dampinglike spin torque. Here j is the current density, ℏ the reduced Planck constant, P the spin polarization efficiency, μ0 the vacuum permeability constant, e the elementary charge, and tz the thickness of ferrimagnetic layer. The parameters used are provided in Supplementary Note 1.

Expression of quantities in Thiele equation

The effective mass meff = μ0tzρ2dxx/(− 4hex) with ρ = Ms1/γ1 + Ms2/γ2, dxx = ∫∂xn ⋅ ∂xndxdy and hex = 2Aex/(μ0Δ2). Here Aex is the exchange coefficient and Δ is the cell size. The gyrovector G = 4πQμ0tz(Ms1/γ1 − Ms2/γ2)ez with the topological charge Q. The frictional force \({{\bf{F}}}_{\alpha }=-\alpha L{\mathop{{\bf{r}}}\limits^{\cdot }}_{{\rm{c}}}=-\alpha ({\mu }_{0}{t}_{z}{d}_{xx}\rho ){\mathop{{\bf{r}}}\limits^{\cdot }}_{{\rm{c}}}\). The skyrmion-skyrmion interaction force, Fss = − ∇ Uss, is given by the interaction potential Uss.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within this article and its Supplementary Information. Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests. The micromagnetic simulation software MUMAX3 used in this work is open-source and can be accessed freely at http://mumax.github.io/.

References

Kaka, S. et al. Mutual phase-locking of microwave spin torque nano-oscillators. Nature 437, 389–392 (2005).

Mancoff, F. B., Rizzo, N. D., Engel, B. N. & Tehrani, S. Phase-locking in double-point-contact spin-transfer devices. Nature 437, 393–395 (2005).

Hamadeh, A. et al. Origin of spectral purity and tuning sensitivity in a spin transfer vortex nano-oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 257201 (2014).

Ruotolo, A. et al. Phase-locking of magnetic vortices mediated by antivortices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 528–532 (2009).

Zeng, Z., Finocchio, G. & Jiang, H. Spin transfer nano-oscillators. Nanoscale 5, 2219 (2013).

Romera, M. et al. Binding events through the mutual synchronization of spintronic nano-neurons. Nat. Commun. 13, 883 (2022).

Romera, M. et al. Vowel recognition with four coupled spin-torque nano-oscillators. Nature 563, 230–234 (2018).

Zahedinejad, M. et al. Two-dimensional mutually synchronized spin Hall nano-oscillator arrays for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 47–52 (2020).

Ross, A. et al. Multilayer spintronic neural networks with radiofrequency connections. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1273–1280 (2023).

Chen, T. et al. Spin-torque and spin-Hall nano-oscillators. Proc. IEEE 104, 1919–1945 (2016).

González, V. H., Litvinenko, A., Kumar, A., Khymyn, R. & Åkerman, J. Spintronic devices as next-generation computation accelerators. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 31, 101173 (2024).

Rippard, W., Pufall, M., Kaka, S., Russek, S. & Silva, T. Direct-current induced dynamics in Co90Fe10/Ni80Fe20 point contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 027201 (2004).

Kumar, A. et al. Robust mutual synchronization in long spin hall nano-oscillator chains. Nano Lett. 23, 6720–6726 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. Spin-wave-mediated mutual synchronization and phase tuning in spin Hall nano-oscillators. Nat. Phys. 21, 245 (2025).

Lisenkov, I., Khymyn, R., Åkerman, J., Sun, N. X. & Ivanov, B. A. Subterahertz ferrimagnetic spin-transfer torque oscillator. Phys. Rev. B 100, 100409(R) (2019).

Dussaux, A. et al. Large microwave generation from current-driven magnetic vortex oscillators in magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Commun. 1, 8 (2010).

Lebrun, R. et al. Mutual synchronization of spin torque nano-oscillators through a long-range and tunable electrical coupling scheme. Nat. Commun. 8, 15825 (2017).

Pribiag, V. S. et al. Magnetic vortex oscillator driven by D.C. spin-polarized current. Nat. Phys. 3, 498–503 (2007).

Mohseni, S. M. et al. Spin torque-generated magnetic droplet solitons. Science 339, 1295–1298 (2013).

Iacocca, E. et al. Confined dissipative droplet solitons in spin-valve nanowires with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 047201 (2014).

Chung, S. et al. Magnetic droplet nucleation boundary in orthogonal spin-torque nano-oscillators. Nat. Commun. 7, 11209 (2016).

Chung, S. et al. Direct observation of Zhang-Li torque expansion of magnetic droplet solitons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 217204 (2018).

Jiang, S. et al. Magnetic droplet soliton pairs. Nat. Commun. 15, 2118 (2024).

Ahlberg, M. et al. Freezing and thawing magnetic droplet solitons. Nat. Commun. 13, 2462 (2022).

Shen, L. et al. Current-induced dynamics and chaos of antiferromagnetic bimerons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 037202 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Current-induced magnetic skyrmions oscillator. N. J. Phys. 17, 023061 (2015).

Garcia-Sanchez, F., Sampaio, J., Reyren, N., Cros, V. & Kim, J.-V. A skyrmion-based spin-torque nano-oscillator. N. J. Phys. 18, 075011 (2016).

Shen, L. et al. Spin torque nano-oscillators based on antiferromagnetic skyrmions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 042402 (2019).

Jin, C. et al. Array of synchronized nano-oscillators based on repulsion between domain wall and skyrmion. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 044007 (2018).

Jin, C. et al. High-frequency spin transfer nano-oscillator based on the motion of skyrmions in an annular groove. N. J. Phys. 22, 033001 (2020).

Gupta, S., Sharma, A., Das, D., Tulapurkar, A. A. & Muralidharan, B. Ultrahigh frequency and multichannel output skyrmion-based nano-oscillator. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 72, 2618 (2025).

Zhou, Y. Magnetic skyrmions: intriguing physics and new spintronic device concepts. Natl. Sci. Rev. 6, 210 (2019).

Fert, A., Reyren, N. & Cros, V. Magnetic skyrmions: advances in physics and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17031 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Skyrmion-electronics: writing, deleting, reading and processing magnetic skyrmions toward spintronic applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 143001 (2020).

Rößler, U. K., Bogdanov, A. N. & Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 442, 797–801 (2006).

Zhou, Y. et al. Dynamically stabilized magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Commun. 6, 8193 (2015).

Shen, L., Qiu, L. & Shen, K. Nonlinear dynamics of directly coupled skyrmions in ferrimagnetic spin torque nano-oscillators. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 48 (2024).

Shen, L., Zhou, Y. & Shen, K. Boundary-free spin torque nano-oscillators based on ferrimagnetic skyrmions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 092403 (2022).

Jiang, W. et al. Dynamics of magnetic skyrmion clusters driven by spin-polarized current with a spatially varied polarization. IEEE Magn. Lett. 9, 1–5 (2018).

Tokura, Y. & Kanazawa, N. Magnetic skyrmion materials. Chem. Rev. 121, 2857–2897 (2021).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 465, 901–904 (2010).

Nakajima, H., Kotani, A., Mochizuki, M., Harada, K. & Mori, S. Formation process of skyrmion lattice domain boundaries: The role of grain boundaries. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 192401 (2017).

Wang, C. et al. Enhanced stability of the magnetic skyrmion lattice phase under a tilted magnetic field in a two-dimensional chiral magnet. Nano Lett. 17, 2921–2927 (2017).

Mochizuki, M. et al. Thermally driven ratchet motion of a skyrmion microcrystal and topological magnon Hall effect. Nat. Mater. 13, 241–246 (2014).

Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 4, 241–255 (1958).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic Superexchange Interaction and Weak Ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91–98 (1960).

Slonczewski, J. C. Current-driven excitation of magnetic multilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 159, L1–L7 (1996).

Finocchio, G., Büttner, F., Tomasello, R., Carpentieri, M. & Kläui, M. Magnetic skyrmions: from fundamental to applications. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 49, 423001 (2016).

Zhao, M. et al. Electrical detection of mobile skyrmions with 100% tunneling magnetoresistance in a racetrack-like device. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 50 (2024).

Vansteenkiste, A. et al. The design and verification of MuMax3. AIP Adv. 4, 107133 (2014).

Thiele, A. A. Steady-state motion of magnetic domains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 30, 230–233 (1973).

Kim, S. K., Lee, K.-J. & Tserkovnyak, Y. Self-focusing skyrmion racetracks in ferrimagnets. Phys. Rev. B 95, 140404(R) (2017).

Barker, J. & Tretiakov, O. A. Static and dynamical properties of antiferromagnetic skyrmions in the presence of applied current and temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 147203 (2016).

Tveten, E. G., Qaiumzadeh, A., Tretiakov, O. A. & Brataas, A. Staggered Dynamics in Antiferromagnets by Collective Coordinates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 127208 (2013).

Shen, L. & Shen, K. Skyrmion-based chaotic oscillator driven by a constant current. Phys. Rev. B 109, 014422 (2024).

Komineas, S. & Papanicolaou, N. Skyrmion dynamics in chiral ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064412 (2015).

Jiang, W. et al. Direct observation of the skyrmion Hall effect. Nat. Phys. 13, 162–169 (2017).

Shen, L. et al. Nonreciprocal dynamics of ferrimagnetic bimerons. Phys. Rev. B 105, 014422 (2022).

Wang, Y., Wang, J., Kitamura, T., Hirakata, H. & Shimada, T. Exponential Temperature Effects on Skyrmion-Skyrmion Interaction. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 044024 (2022).

Brearton, R., van der Laan, G. & Hesjedal, T. Magnetic skyrmion interactions in the micromagnetic framework. Phys. Rev. B 101, 134422 (2020).

Yamaguchi, T. et al. Synchronization and chaos in a spin-torque oscillator with a perpendicularly magnetized free layer. Phys. Rev. B 100, 224422 (2019).

Rosenstein, M. T., Collins, J. J. & De Luca, C. J. A practical method for calculating largest Lyapunov exponents from small data sets. Phys. D. 65, 117–134 (1993).

Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472–2475 (1988).

Kang, W., Huang, Y., Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Zhao, W. Skyrmion-Electronics: An Overview and Outlook. Proc. IEEE 104, 2040–2061 (2016).

Finley, J. & Liu, L. Spintronics with compensated ferrimagnets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 110501 (2020).

Xu, Z. et al. Anomalous switching pattern in the ferrimagnetic memory cell. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 611, 172614 (2024).

Flovik, V., Macià, F. & Wahlström, E. Describing synchronization and topological excitations in arrays of magnetic spin torque oscillators through the Kuramoto model. Sci. Rep. 6, 32528 (2016).

Awad, A. A. et al. Long-range mutual synchronization of spin Hall nano-oscillators. Nat. Phys. 13, 292–299 (2017).

Houshang, A. et al. Spin-wave-beam driven synchronization of nanocontact spin-torque oscillators. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 280–286 (2016).

Sani, S. et al. Mutually synchronized bottom-up multi-nanocontact spin-torque oscillators. Nat. Commun. 4, 2731 (2013).

Zahedinejad, M. et al. Memristive control of mutual spin Hall nano-oscillator synchronization for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Mater. 21, 81–87 (2022).

Desplat, L. & Dupé, B. Eigenmodes of magnetic skyrmion lattices. Phys. Rev. B 107, 144415 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Y.Z. acknowledges the support from the Shenzhen Peacock Group Plan (KQTD20180413181702403), the Shenzhen Fundamental Research Fund (Grant No. JCYJ20210324120213037), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2021B1515120047), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2374123, 11974298). Q.S. acknowledges the support from Hong Kong General Research Fund (No. 16303322 and 16309924). L.S. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12504151).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. coordinated the project. L.S. performed the micromagnetic simulations and the theoretical analysis. L.S. drafted the manuscript and revised it with input from Q.S., J.Å., and Y.Z. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Qiming Shao is an Associate Editor for npj Spintronics, but was not involved in the editorial review of, or the decision to publish this article. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, L., Shao, Q., Åkerman, J. et al. Terahertz spin torque nano-oscillator based on a ferrimagnetic skyrmion lattice. npj Spintronics 4, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00124-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00124-w