Abstract

With the emergence of super-resolution lenses such as superlenses and hyperlenses, the diffraction limit of approximately half wavelength is no longer unbreakable. However, superlenses are easily affected by weak intrinsic losses and hyperlenses fail to achieve perfect imaging, significantly constraining their practical utility. To address these challenges, here we propose a perfect hyperlens inspired by the metric of de Sitter spacetime in cosmology. Notably, perfect hyperlens is capable of self-focusing in geometrical optics while supporting propagating waves with exceptionally large wavenumbers, granting it key advantages such as ultra-high resolution, no aberration and strong robustness. Furthermore, we numerically demonstrate the hyperbolic focusing performance and mimic the de Sitter spacetime in naturally in-plane hyperbolic polaritons of α–MoO3 films, which can be achieved via a gradient thickness profile. Our work provides cosmological insights into the field regulation in hyperbolic materials and greatly innovates the design principles of traditional imaging lenses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Einstein’s general relativity1 well predicted gravitational waves2 and recently observed black holes3, which has sparked great interest in exploring and simulating celestial phenomena in various physical systems. Transformation optics (TO)4,5,6 was widely used in the analogy of general relativity, due to its convenience and flexibility on manipulating electromagnetic waves. TO simulates various models of spacetime by controlling electromagnetic parameters of materials and visualizes the effects by evolution of electromagnetic fields7. The effects of some well-known spacetime models, such as the Schwarzschild black hole8, the Minkowski spacetime9, the cosmic string10, and spatial wormholes11 have been mimicked by optical materials. Other fantastic topics, such as time travel12, the Milne universe13, the big crunch14, the expanding universe15, were also explored. Remarkably, most analogies of astronomical phenomena require complicated electromagnetic parameters that are challenging to reach with conventional materials and structures.

To address this issue, metamaterials16—functional microstructures developed to realize various extraordinary properties and manipulate wave-propagating behaviors—have been extensively utilized to mimic astronomical phenomena in optical systems. Moreover, metamaterials have aroused considerable research interests across various fields, such as photonics time crystals17, bound states in the continuum18,19, silicon nanoresonators20, among others. Their applications extend beyond optics to other types of waves, including but not limited to acoustic metamaterials21, hydrodynamic metamaterials22, and thermal metamaterials23. Interestingly, the concept of metamaterials originated from the theoretical study of negative refractive index by Veselago in 196824 and was late reported by Pendry in 200025. Notably, negative refraction is regarded as the key enabler for creating a perfect lens, capable of overcoming the conventional diffraction limit of imaging. Initiated by perfect lens, superlens26,27,28,29 gained widespread attention owing to their advantages, such as light weight, small size, and easy integration, and has been realized in different structures. However, while superlens excels at magnifying evanescent waves and facilitating precise geometric imaging, its performance is highly sensitive to even minimal material loss30. Simultaneously, the hyperlens31,32,33,34 was introduced as a kind of far-field super-resolution lens, capable of converting near-field evanescent waves into far-filed propagating waves and generating a preenlarged image of the input distribution on the output plane. Compared to the superlens, the hyperlens mitigates the effect of material loss on revolution by ensuring that all rays from the input plane travel equal path lengths through hyperbolic metamaterials. However, the hyperlens cannot achieve geometrically perfect imaging, often resulting in severe caustics30. Additionally, while the perfect imaging lens with positive refraction35 proposed by Leonhardt overcomes the limitations of both superlens and hyperlens, it relies on the assistance of active drain, meaning that super-resolution imaging is no longer an intrinsic property of the lens itself. Consequently, designing a geometrically perfect lens without aberration based on hyperbolic system remains a crucial goal for the advancement of optical imaging lenses.

Notably, many Lorentzian manifolds36,37 in Minkowski spacetime offer novel insights and a deeper understanding for key characteristics in hyperbolic systems. These insights hold great potential for various optoelectronic applications, particularly in imaging. In this paper, we introduce a perfect hyperlens (PHL) inspired by the de Sitter spacetime38 in cosmology, which can convert evanescent waves to propagating waves and achieve geometrically perfect imaging. Our analysis encompasses the hyperbolic self-focusing and verifies the super-resolution performance of PHL from both geometric optics and wave perspectives. Moreover, we demonstrate our results based on the hyperbolic polaritons by controlling the thickness of α–MoO3 films. Through transformation optics, we establish a new PHL system, providing innovative guidelines for the future design and optimization of hyperlens.

Results

Derivation of PHL’s metric

We start from a general static metric with

where t, r and Ω represent time, radial coordinate and isolid angle coordinate, respectively. When we set f (r) = 1 − r2/a2 (r ≤ a, the horizon), the metric is for de Sitter space. In mathematical physics, de Sitter space is a maximally symmetric Lorentzian manifold with constant positive scalar curvature. Moreover, it can be defined as a submanifold of generalized Minkowski space in one higher dimension

By introducing different slicing method, various specialized metrics can be obtained36. Here we consider the closed slicing, where the metric of the de Sitter space is given by

Then, replacing t and Ω with the polar angle u and azimuth angle φ respectively, we obtain a new metric that represents the de sitter spacetime of Lorentz signature37

In Minkowski spacetime, the metric can be sketched as a hyperboloid manifold (see Fig. 1b). Interestingly, we can get the spherical metric by set u = iθ (see Fig. 1a)

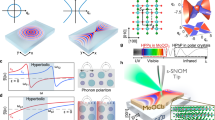

The “spacetime travel” on the (a) spherical surface of Euclidean signature and (b) the de Sitter spacetime of Lorentz signature. The polar angle θ varies along the surface of the sphere within a finite range of values [-π/2, +π/2], while u varies along the de Sitter hyperboloid within an infinite range of values [-∞, +∞]. After a Mercator Projection for (a, b), we obtain the (c) ML profile and PHL profile. The stars are the excitation sources (x0, y0) and the circles are images. In (c, d), the red, blue and green curves represent the rays with incident direction \({\left|\frac{dy}{dx}\right|}_{initial}\) =0.5/1/2 respectively.

Compared with Eq. (5), Eq. (4) avoids the zeros of cos θ and become asymptotic to de Sitter space in the far past and future. In cosmology, the transformation from θ to u describes the creation from nothing of a closed universe that then expands exponentially fast. To mimic this case in optics, we consider the Mercator Projection \(z=i{\rm{In}}\left(\frac{X+iY}{1-Z}\right)\)39 for both the sphere and de sitter hyperboloid. This approach allows us to derive the following metrics in the Cartesian coordinate system

Here ds2 also represents the optical path once we treat n(y)/n(y’) as the refractive index profile, where a = l/2π is the lens width across which the on-axis index n0 decrease 1.54 times/increase 1.85 times. l is the path period along the waveguide axis. Equation (6a) describes the generalized metric of the two-dimensional (2D) Mikaelian lens (ML) profile40, which possesses a very interesting property that41, all rays from a source (x0, y0) within the ML will produce images along y = ±y0 with a periodicity of aπ (see Fig.1c). However, the ML profile cannot deal with evanescent waves, leading to scattered images.

The hyperbolic metric derived from the Mercator Projection of the de sitter hyperboloid Eq. (6b) is the focus of our discussion, and is referred to as perfect hyperlens (PHL) profile in this paper. Notably, PHL profile can also be obtained through conjugate transformations y = iy’ applied to ML profiles. Crucially, the hyperbolic manifold of de Sitter space induces the hyperbolic dispersion and transform the refractive index from a monotone function to a periodic function. However, ML and PHL profiles remain conformally equivalent, ensuring perfect geometric imaging while preserving the same Gaussian curvature 1 (see Note S2). Furthermore, in addition to Mercator Projection, we also consider the vertical projection for Eq. (4) and obtain additional PHL profiles (see Note S5). By employing various slicing methods and mapping methods, we may take more inspiration from cosmological metrics in the future.

Self-focusing and imaging analysis of PHL

We analyze the geometric rays of the ML profile and the PHL profile with different incident directions \({|\frac{dy}{dx}|}_{initial}\)>1, \({|\frac{dy}{dx}|}_{initial}\) =1, \({|\frac{dy}{dx}|}_{initial}\) <1 (Fig. 1c, d, Fig. S1). Unlike the ML profile, the energy of the PHL system E depends on the incident directions (see Note S1). Rays with E > 0 focus perfectly with a period of aπ while rays with E < 0 diverge in the y axis. It’s worth noting that, some special rays with E = 0 propagate along a 45-degree trajectory. From a cosmological perspective, if we regard the central lines of PHL profiles y = jl/2 (correspond to n = n0) as the center of the universe, then the focusing and diverging rays resemble the motions of the particles moving around the center of the universe under the force of gravity and the particles escaping the center of the universe. Unlike the monotonic profiles of ML, PHL profiles is periodic with the boundaries at y = jl/2+l/4 (correspond to n = ∞). Consequently, when the incident position is shifted off-axis, there exist exclusive propagation orbits within each refractive index period (see Fig. S1b). As a result, the rays with E > 0 originating from the source (j-1/2)l/2 < y0 < (j + 1/2)l/2 will generate images along y = jl-y0 with a period of aπ, where j is an arbitrary integer.

To extend Eq. (6b) into wave systems, we drop the prime of y for aesthetic reasons and introduce a z-axis as the additional spatial coordinate, and rewrite the line element dl2 and metric gij as follow:

Based on transformation optics, the relative permittivity and relative permeability of the PHL profile can be expressed as39

Since we consider the 2D transverse electric (TE) polarization in our study, where the electric field is polarized along the z-axis (Ez), only the parameters µx, µy and εz are required. Thus, the dominant parameters (µxp, µyp, εzp) can be written as either (−1, 1, n02/cos(y/a)) or (-n02/cos(y/a), n02/cos(y/a), 1) to remain nx2= µypεzp and ny2= µxpεz. Then we stimulated the field using a line source along the z direction, positioned at the center. Among them, the parameters n0 = 1, a = 1 and λ = 0.9695 (k = 7) (arbitary unit). As is well known in the propagation of hyperbolic waves42, the values of μx and μy determine the open angle and direction of hyperbolic waves. When μx > 0 and μy < 0, the hyperbolic wave will propagate along the y-axis within the open angle 2arctan (|μy /μx | ). In our case, the energy will spread out along y-axis (see Fig. 2a, b). Conversely, when μx < 0 and μy > 0, the hyperbolic wave propagates and forms periodic images along the x-axis (see Fig. 2c, d). Notably, the wave simulation exhibits a high similarity to the ray results. Differently, we can selectively filter the imaging waves with E > 0 by simply adjusting the appropriate parameters, leveraging the high confinement of the hyperbolic waves. Interestingly, the field pattern of PHL profiles closely resembles to the Penrose diagram43, which is commonly used in cosmology to depict causal relationships between different points in spacetime.

Numerical simulations of the electric field and the corresponding intensity distributions based on the PHL (n0 = 1, a = 1) with (a, b) μx = 1, μy = −1 and (c, d) μx = −1, μy = 1. Analytical calculations of the electric field and the corresponding intensity distributions based on the PHL with (e, f) μx = −1, μy = 1. Here, the stars and red curves in each figure represent the excitation sources at (0,0) and the corresponding FWHM. The wavelength λ is set as 0.9695 (arbitary unit).

To theoretically validate the simulation results theoretically, we solve Maxwell’s equations and obtain the electric field solution in Note S3 as

where the coefficient cm is given by

where Ez (0, y) represents the input electric field at the plane of x = 0. For consistency, the input field is set as a line current source along z direction here. Notably, the analytical electric field and intensity closely match the simulation results (see Fig. 2e, f), with only minor discrepancies due to computational capacity. Our PHL profile shows the exceptional focusing effect with ultra-low FWHM about 0.05λ–0.08λ (see Fig. 2d, f). In our opinion, it is because that PHL combines the perfect geometric focusing of the ML with hyperbolic anisotropy that can transfers evanescent wave into propagating wave to support propagating waves with very large wavenumbers31,32.

To further verify this, we calculate and analyze the corresponding isofrequency contours (IFCs) in Fig. S2. In this analysis, we discretize the spaces of ML and PHL as infinite interfaces with continuously varying out-of-plane permittivities εz along y-axis. For 2D TE modes, the dispersion relation for ML and PHL (n0 = a = 1) can be obtained by

where kx, ky and k0 are the wave vectors in the x and y directions and vacuum wavenumber respectively. Propagating waves refract at the interfaces where the in-plane wave vectors discontinue and such refractions follow the phase-matching conditions (\({k}_{i}^{\parallel }={k}_{t}^{\parallel }\))44. Then we could sketch the incident and refracted wave vectors and determine the propagation path accordingly. In traditional hyperlens32, all the input wave distributions with arbitrary wave vectors are transferred to the output plane through a set of rays parallel to the stratification axis. Differently, arbitrary input beam with wave vector kin = (kx, ±ky) in PHL undergoes continuous refractions at interfaces with different permittivity εz and ultimately reaching the image with kout = (kx, ∓ky) (red and black isometric arrows in Fig. S2a). Comparing the isofrequency contours of ML and PHL, we observe that PHL profile support the propagation and focusing of waves with very large wavenumbers, whereas ML does not. This fundamental difference leads to a significant resolution advantage in PHL. Notably, the beams with higher wave vector can reach higher interfaces at larger incident angles.

To further explore the imaging properties, here we consider a PHL under the air background (see Fig. 3a), whose electromagnetic parameters vary along the y direction as follows:

a The gradient profiles \(\sqrt{{\varepsilon }_{Z}}\) and light ray trajectories of the PHL. Calculated electric field intensity patterns and the corresponding FWHMs in the (b) ML and (c) PHL (d = 132 mm). The red curves represent the normalized electric field intensity along the y-axis at the imaging points (red dotted line). The relative FWHMs of the imaging point are marked. Imaging performance of the (d) ML and (e) PHL where two point sources with a spacing of 0.13λ are placed at the edge of the lens. The ML fails to resolve the two point sources but PHL can resolve clearly. The simulation frequency is f = 11 GHz.

It perfectly focuses light rays emitted from a point source to another image point, though some rays experience reflection near the imaging point due to impedance mismatching. In this sense, PHL is similar to the solid immersion lens45. Considering flexibility of the sample design in the microwave range, we choose an optimized PHL with parameters d = l/2 = 132 mm and n0 = 1, as an example. In order to mitigate the effect of singularity εz = ∞ at the boundary y = ±l/4, we added a loss factor of 0.001i to the permeability of PHL. For comparison, we also simulate an ML under the same conditions. We put a point source in air near the lens (x0 = −66.05 mm) and numerically calculate the electric field intensity patterns and the corresponding FWHMs at the frequency of f = 11 GHz (see Fig. 3b, c). The red curves show the electric field intensity and the FWHM of the imaging point is marked on the curve. Comparing with ML, the images in PHL are of higher quality with much smaller spots and lower FWHM. Moreover, there are continuous total internal reflection at the boundary of PHL, which causes an energy increasing near the image point. To further confirm the super-resolution imaging of ML and the PHL, a pair of identical point sources with a spacing of 0.13λ are placed on the edge of lens. It is clearly seen that the two identical point sources in PHL are distinguishable (see Fig. 3e). In comparison, ML fails to identify two identical point sources, as shown in Fig. 3d. Therefore, the super-resolution imaging of PHL is demonstrated. In Note S4, we further investigate the effects of material losses on the performance of PHL in details. The results indicate that the super-resolution capabilities of PHL are tolerable for minor material losses. More importantly, by employing coordinate transformation or coordinate substitution, we can design other types of PHLs that still retain the characteristics of super-resolution imaging (Fig. S4).

Design of the PHL profile based on hyperbolic van der Waals polaritons

Building on the numerical examples discussed, we now explore possible experimental demonstrations of PHL. In order to generate an in-plane hyperbolic response, here we consider two-dimensional hyperbolic van der Waals materials α–MoO3. Phonon polaritons in α-MoO342,46,47 exhibit in-plane hyperbolic dispersion within most frequencies of the Reststrahlen band (RB) I from 545 to 851 cm−1 and Reststrahlen band II from 816 to 972 cm−1 (Fig. S3). These highly confined hyperbolic polaritons also exhibit high sensitivity to the thickness of α–MoO3 flakes, making them ideal for our study. Hence, here we consider the waveguide model composed of three layers: air (z ≥ d), α–MoO3 slab with finite thickness (0 ≤ z ≤ d), and SiO2 substrate (z ≤ 0) as shown in Fig. 4a. Assuming the in-plane PhPs propagate along the [100] direction, i.e., the x axis, the electric and magnetic fields can be expressed as\(\overrightarrow{E}(x,z,t)=\overrightarrow{e}E(z)\exp (iqx-i\omega t)\) and\(\overrightarrow{H}(x,z,t)=\overrightarrow{h}H(z)\exp (iqx-i\omega t)\). Among them, the in-plane propagation constant is q=neffk0, where neff is the effective refractive index and k0 is the vacuum wave vector. By solving Maxwell equations for the transverse magnetic (TM) modes (with only field components of (Ey, Hx, and Ez)) and matching the continuous boundary conditions, we derive the dispersion relation,

where \({k}_{z}=\sqrt{{k}_{0}^{2}{\varepsilon }_{x}-\frac{{\varepsilon }_{x}{q}^{2}}{{\varepsilon }_{z}}}\) and \({\alpha }_{1,3}=\sqrt{{q}^{2}-{k}_{0}^{2}{\varepsilon }_{1,3}}\) are z components of photon momenta in α–MoO3, air, and SiO2, respectively. d denotes the thickness of the α–MoO3 slab. m = 0, 1, 2… are the orders of the TM modes. Taking practical experiments into account, the first order m = 0 is only considered because the higher modes are usually inhibited by imperfections of the sample edges and the current signal/noise ratio limitation. We use refractive index profile of the PHL [Eq. (6b)] as the approximation of the effective refractive index neff of the biaxial slab in the 3D model, which can be obtained by

a Schematic of the three-dimensional α–MoO3 waveguide model with gradient thickness. b The relation between the thickness of α–MoO3 and the coordinate y. c, d are polaritonic wave patterns Ez on the top surface of α–MoO3, which are excited by the electric dipoles (stars) of the frequencies 673.5 cm−1 and 934.7 cm−1, respectively. Among them, the red dotted lines represent the expected images position x=jl/2.

For simplicity, we set a = 5/π (l/2 = 5μm). Here, the frequencies 673.5 cm−1 with {εx(001), εy(100), εz(010)} = {−8.98–0.24i, 8.98–0.06i, 2.87–0.001i} and 935.7 cm−1 with {εx(100), εy(001), εz(010)} = {−1.36–0.1i, 1.36–0.02i, 7.52–0.22i} are adopted to excite the hyperbolic polaritons along the x axis, ensuring a nearly 90° opening angle with |Re(εx)|≈ |Re(εy)|. Considering the realistic thickness of the α–MoO3 flake, we set n0/√|εx| of the frequencies 673.5 cm−1 and 935.7 cm−1 as 6.5 and 12 respectively. Substitute q = neffk0 into Eq. (13), we can figure out the relationship between the thickness distribution and the plane coordinates (see Fig.4b). From previous results, we can find that the wave is strictly limited in single period region -l/4 < y < l/4 because of the singularity at |y | = l/4. Hence, we only need to consider and prepare the structure in this region. To simulate the tip-launched polaritons, we introduced a dipole located 200 nm above the top of the α–MoO3 flake, polarized perpendicular to the surface. Consistent with the rays (Fig.1d) and two-dimensional wave patterns (Fig. 2c) of PHL profiles, the z component of electric fields [Re(Ez)] on the surface of α–MoO3 films demonstrates the self-focusing responses [Minor scatterings in Fig. 4c, d arise from the limited computational domain and computer capacity but remain tolerable]. Notably, the focusing period in frequency 935.7 cm−1 is less than the estimated value l/2 = 5 µm while that in frequency 673.5 cm−1 is equal to the estimated value. This discrepancy likely results from the high-order effects48. Nevertheless, the propagation wavefronts and focusing phenomena are still clear. It is worth mentioning that the result can be applied to the construction of hyperbolic multimode waveguide and verification the Talbot Effect in hyperbolic optics41,49. More intriguingly, when interpreting the y-axis as a time coordinate, the observed light propagation on the films could be seen as an analogy to time travel12. In addition, by precisely preparing the films with a gradient thickness profile and the corresponding focusing width, it will be also helpful for infrared super-resolution imaging.

Discussion

In this paper, we theoretically introduce a perfect hyperlens, which is related to the de Sitter spacetime in cosmology. Through theoretical analyses and numerical simulations, we validate the excellent super-resolution properties of PHL. It is worth noting that the potential computational errors mentioned in the above discussion stem from insufficient mesh density and mismatch of perfect matching layer (PML). The former arises because the continuous gradient refractive index or thickness distributions of PHL necessitate an extremely high mesh density for accurate simulations. Otherwise, slight deviations (~0.01λ) of FWHM or imaging position may occur. The latter issue results from the fact that conventional PML in 2D simulations cannot effectively absorb the hyperbolic wave beyond the simulation boundaries, leading to significant scatterings. To mitigate these errors, we have introduced weak losses46 or special hyperbolic PML50 in simulations. Overall, these computational errors remain tolerable and can be effectively minimized by parameter optimization in practical implementations.

For convenience, here we primarily focus on the simplest 2D case, where |μx | = |μy | . In essence, the distinction between the space |μx | = |μy| and space |μx | ≠ |μy| lies in the transformation Y = |μx/μy | y, rendering both spaces conformal. This transformation implies that, in the lossless case, the ratio |μx/μy| affects only the imaging position rather than the overall imaging performance. For 3D experimental implementation, the theoretical deduction remains valid but is not entirely precise, as the hyperbolic dispersions of α–MoO3 films introduces additional complexities beyond simple variations of permittivity ratio |εx/εy | . Moreover, alternative materials, such as Si, Au, and others can also serve as the substrates of α–MoO3 films, further expanding the possibilities for realizing the PHL profile. In general, these properties are able to provide considerable flexibility in selecting suitable materials and operating frequencies for practical implementations. Compared to traditional hyperlens, PHL exhibits more intricate electromagnetic parameter distributions, necessitating higher fabrication precision for metamaterials or 2D materials. Experimentally, such a structure with spatially varying thickness can be fabricated using focused ion-beam (FIB) etching. By carefully monitoring the etching thickness of α–MoO3 via scanning electron microscope and optical microscope, and setting reasonable heating temperatures to fully anneal, the curved surface can be shaped to match the desired profile with high accuracy. In addition to self-focusing application in infrared band, the proposed lens can also be prepared by means of split-ring resonators, enabling its application in various super-resolution near field imaging systems operating in the microwave band51,52.

While our focus lies in optical imaging, the fundamental principle underlying our approach can be extended to other wave phenomena, including acoustic waves53 and elastic waves54, as well as the researches of the sensors, antennas, wavefront shaping, encoder and so on. Most importantly, our research suggests that some intriguing curved spacetimes, such as de sitter space, anti-de Sitter space, and Schwarzschild black hole could inspire new directions in of hyperbolic photonics, paving the way for novel optoelectronics applications in the future.

Data Availability

The data supporting our study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Einstein, A. Approximative integration of the field equations of gravitation. Sitzungsber. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 1, 688 (1916).

Abbott, B. P. et al. Observation of gravitational waves from a binary black hole merger. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 061102 (2016).

Akiyama, K. The event horizon telescope collaboration et al. First M87 event horizon telescope results. I. The shadow of the supermassive black hole. Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L1 (2019).

Pendry, J. B., Schurig, D. & Smith, D. R. Controlling electromagnetic fields. Science 312, 1780 (2006).

Xu, L. & Chen, H. Conformal transformation optics. Nat. Photonics 9, 15–23 (2015).

Xu, L. & Chen, H. Transformation metamaterials. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005489 (2021).

Chen, H., Tao, S., Bělín, J., Courtial, J. & Miao, R.-X. Transformation cosmology. Phys. Rev. A 102, 023528 (2020).

Chen, H., Miao, R.-X. & Li, M. Transformation optics that mimics the system outside a Schwarzschild black hole. Opt. Express 18, 15183–15188 (2010).

Smolyaninov, I. I. & Narimanov, E. E. Metric signature transitions in optical metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 067402 (2010).

Sheng, C., Liu, H., Chen, H. & Zhu, S. Definite photon deflections of topological defects in metasurfaces and symmetry-breaking phase transitions with material loss. Nat. Commun. 9, 4271 (2018).

Greenleaf, A., Kurylev, Y., Lassas, M. & Uhlmann, G. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 183901 (2007).

Boston, S. R. Time travel in transformation optics: Metamaterials with closed null geodesics. Phys. Rev. D 91, 124035 (2015).

Figueiredo, D., Moraes, F., Fumeron, S. & Berche, B. Cosmology in the laboratory: an analogy between hyperbolic metamaterials and the Milne universe. Phys. Rev. D 96, 105012 (2017).

Smolyaninov, I. I. & Hung, Y. J. Big Crunch-based omnidirectional light concentrators. J. Optics 16, 125103 (2014).

She, J., Tao, S., Liu, T. & Chen, H. Simulation of the expanding universe in hyperbolic metamaterials. Opt. Express 31, 33312–33319 (2023).

Chen, H. Y. Advances and frontiers in metamaterials. Front. Mater. 8, 685025 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Stationary charge radiation in anisotropic photonic time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 093803 (2023).

Chai, R. et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 183801 (2024).

Gromyko, D., Loh, J. S., Feng, J., Qiu, C.-W. & Wu, L. Enabling all-to-circular polarization upconversion by nonlinear chiral metasurfaces with rotational symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 023804 (2025).

Staude, I. & Schilling, J. Metamaterial-inspired silicon nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 11, 274–284 (2017).

Cummer, S. A., Christensen, J. & Alù, A. Controlling sound with acoustic metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16001 (2016).

Park, J., Youn, J. R. & Song, Y. S. Hydrodynamic metamaterial cloak for drag-free flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 074502 (2019).

Han, T. et al. Experimental demonstration of a bilayer thermal cloak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 054302 (2014).

Veselago, V. G. The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of ε and µ. Sov. Phys. 10, 509 (1968).

Pendry, J. B. Negative refraction makes a perfect lens. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3966–3969 (2000).

Fang, N., Lee, H., Sun, C. & Zhang, X. Sub-diffraction Limited optical imaging with a silver superlens. Science 308, 534 (2005).

Taubner, T., Korobkin, D., Urzhumov, Y., Shvets, G. & Hillenbrand, R. Near-Field microscopy through a Sic superlens. Science 313, 1595 (2006).

Xiong, Y., Liu, Z., Sun, C. & Xiang, X. Two-dimensional imaging by far-field superlens at visible wavelengths. Nano Lett. 7, 3360–3365 (2007).

Zhang, X. & Liu, Z. Superlenses to overcome the diffraction limit. Nat. Mater. 7, 435–441 (2008).

Smith, D. R. et al. Limitations on subdiffraction imaging with a negative refractive index slab. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 1506–1508 (2003).

Jacob, Z., Alekseyev, L. V. & Narimanov, E. Optical hyperlens: far-field imaging beyond the diffraction limit. Opt. Express 14, 8247–8256 (2006).

Salandrino, A. & Engheta, N. Far-field subdiffraction optical microscopy using metamaterial crystals: theory and simulations. Phys. Rev. B 74, 075103 (2006).

Li, J., Fok, L., Yin, X., Bartal, G. & Zhang, X. Experimental demonstration of an acoustic magnifying hyperlens. Nat. Mater. 8, 931–934 (2009).

Rho, J. et al. Spherical hyperlens for two-dimensional sub-diffractional imaging at visible frequencies. Nat. Commun. 1, 143 (2010).

Leonhardt, U. & Philbin, T. G. Perfect imaging with positive refraction in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. A 81, 011804 (2010).

de Sitter, W. On the curvature of space. Proc. Kon. Ned. Acad. Wet. 20, 229–243 (1917).

Witten, E. A note on complex spacetime metrics. Frank Wilczek: 50 years of theoretical physics. 245-280 (2022).

de Sitter, W. On the relativity of inertia: Remarks concerning Einstein’s latest hypothesis. Proc. Kon. Ned. Acad. Wet. 19, 1217–1225

Leonhardt, U. & Philbin, T. Geometry and light: the science of invisibility (Courier Corporation, 2012).

Mikaelian, A. & Prokhorov, A. V self-focusing media with variable index of refraction. Prog. Opt. 17, 279–345 (1980).

Wang, X. et al. Self-focusing and the Talbot effect in conformal transformation optics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 033902 (2017).

Hu, G. et al. Topological polaritons and photonic magic angles in twisted α-MoO3 bilayers. Nature 582, 209–213 (2020).

Ellis, G. F. R. & Hawking, S. W. The large scale structure of space-time (Cambridge university press, 1973).

Kong, J. A. Electromagnetic Wave Theory. (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1990).

Zhou, Y., Hao, Z., Zhao, P. & Chen, H. Solid immersion maxwell’s fish-eye lens Without drain. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 034039 (2022).

Ma, W. et al. In-plane anisotropic and ultra-low loss polaritons in a natural van der Waals crystal. Nature 562, 557–562 (2018).

Zheng, Z. et al. A mid-infrared biaxial hyperbolic van der Waals crystal. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav8690 (2019).

Álvarez-Pérez, G., Voronin, K. V., Volkov, V. S., Alonso-González, P. & Nikitin, A. Y. Analytical approximations for the dispersion of electromagnetic modes in slabs of biaxial crystals. Phys. Rev. B 100, 235408 (2019).

Li, S. et al. Universal multimode waveguide crossing based on transformation optics. Optica 5, 1549–1556 (2018).

Ge, Z., Tao, S. & Chen, H. Perfectly matched layer for biaxial hyperbolic materials. Opt. Express 31, 6965–6973 (2023).

Schurig, D. et al. Metamaterial electromagnetic cloak at microwave frequencies. Science 314, 977–980 (2006).

Ma, Y. G., Ong, C. K., Tyc, T. & Leonhardt, U. An omnidirectional retroreflector based on the transmutation of dielectric singularities. Nat. Mater. 8, 639–642 (2009).

Quan, L. & Alù, A. Hyperbolic sound propagation over nonlocal acoustic metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 244303 (2019).

Lee, D. et al. Singular lenses for flexural waves on elastic thin curved plates. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 034039 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Cheng-Wei Qiu for helpful discussion. This research was funded by the following: National Key Research and Development Program of China grant 2023YFA1407100 and 2020YFA0710100 (to H.Y.C.); National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 12361161667 (to H.Y.C.); Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation grant 20224ACB201005 (to H.Y.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. wrote the main manuscript text and H.Y.C. supervised this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, T., Xiao, W. & Chen, H. Cosmology analogy for perfect hyperlens. npj Nanophoton. 2, 16 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00063-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00063-8

This article is cited by

-

A lithography-free approach to polaritonic Luneburg lenses

Nature Communications (2025)