Abstract

Lithium niobate on insulator (LNOI), with its excellent electro-optic properties, high transparency, and stability, has been widely used in high-speed photonic integrated circuits (PICs). Waveguide crossings are one of the most fundamental and critical interconnect structures in PICs. They enable efficient, low-loss, and low-crosstalk transmission of optical signals at waveguide intersections, thereby facilitating complex optical routing in two-dimensional planes. We demonstrate an improved broadband, low-loss, compact LNOI waveguide crossing covering portions of the S-band and fully spanning the C, L, and U bands. Using the adjoint algorithm, the design achieves <0.12 dB insertion loss and < −40 dB crosstalk over 180 nm bandwidth, with best-case values of 0.05 dB and −50 dB. Its 16 × 16 μm2 footprint is smaller than comparable designs. This work demonstrates the viability of high-performance, compact inverse-designed devices on the LNOI platform, advancing possibilities for high-density photonic applications in data centers and quantum photonics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium niobate on insulator (LNOI) has emerged as a leading integrated photonic platform, driven by recent breakthroughs in high-quality thin-film fabrication1. It uniquely combines ultra-low propagation loss2,3,4,5,6, a strong Pockels effect for high-speed modulator7,8,9, high nonlinear coefficients10, and ultra-broadband transparency from the visible to the mid-infrared (400–5000 nm). These characteristics distinguish LNOI from established platforms such as silicon-on-insulator (SOI) and silicon nitride (SiN). Thus, LNOI offers a versatile and high-performance photonics platform that addresses key gaps in electro-optic and nonlinear functionality faced by conventional material systems. The rapid growth of artificial intelligence (AI), data centers, and quantum communications is driving increased demand for broadband, high-density, and large-scale LNOI photonic integrated circuits (PICs)11. These advanced PICs are essential for expanding bandwidth capacity, enhancing data center performance, and optimizing power consumption. In LNOI PICs, waveguide crossings are essential for minimizing loss and crosstalk while maximizing spatial efficiency and routing flexibility.

Silicon photonic platforms have successfully implemented various waveguide crossing designs-including multimode interference (MMI)12, shaped taper13, subwavelength grating14, and holey subwavelength grating15. MMI-based structures typically exhibit large footprints and narrow bandwidths; shaped taper configurations show high sensitivity to fabrication tolerances; while subwavelength grating implementations present both challenging fabrication requirements and polarization-dependent behavior. These approaches were initially developed on SOI platforms before being adapted to LNOI16,17. In contrast, inverse design techniques using genetic algorithms have enabled superior performance in Si and SiN platforms, achieving low insertion loss, minimal crosstalk, and compact footprints18,19,20,21. Although inverse-designed LNOI devices have been reported, their performance has not surpassed that of conventional designs, making them less suitable for practical applications. Achieving a similar inverse-designed device on the LNOI platform has proven challenging due to fabrication limitations. The exceptional chemical stability of lithium niobate (LN) makes reactive ion etching particularly challenging, resulting in relatively large feature sizes and significant sidewall angles. While inverse-designed photonic devices have been demonstrated on mature platforms and even emerging optical materials like silicon carbide22 and diamond23, LNOI-based inverse-designed devices remain rare. Dry-etched LNOI waveguides typically exhibit substantial sidewall angles, complicating the precise determination of waveguide effective and affecting simulation accuracy. Furthermore, LNOI waveguides are commonly ridge waveguides with a residual layer, which reduces the refractive index contrast and introduces additional challenges to the inverse design due to the thickness variations. Additionally, traditional inverse design methods, which are optimized for single-wavelength operation, often struggle to account for varying effective index across different wavelengths. To overcome these challenges in design and fabrication, we have refined simulation parameters for LNOI waveguides in our inverse design model, incorporating experimental parameters to enhance both accuracy and overall performance.

In this work, we advance the state-of-the-art by experimentally demonstrating a broadband, low-loss, and compact LNOI waveguide crossing based on a refined inverse-design model. Our devices achieve an insertion loss of less than 0.12 dB and a crosstalk of less than −40 dB across the portions of the S and fully C+L+U wavelength bands, with best performance as low as 0.05 dB insertion loss and −50 dB crosstalk. To the best of our knowledge, our work significantly extends the operational bandwidth and reduces losses, surpassing traditional platforms such as Si and SiN. The fabrication process is straightforward and simple, requiring only one etching step on LNOI wafer. Furthermore, the device features an exceptionally small footprint of just 16 × 16 μm2, significantly smaller than other reported LNOI crossings with comparable performance. By leveraging a refined inverse design model and high fabrication tolerance, our broadband, highly efficient, and compact inverse-designed crossing paves the way for advanced LNOI photonic applications. This advancement greatly enhances the feasibility of high-density, large-scale implementations in telecommunications and integrated quantum photonics based on the LNOI platform.

Results

Device design

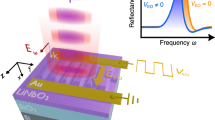

We employed the adjoint algorithm24 to optimize the shape of the LNOI waveguide crossing. The adjoint algorithm is a powerful gradient-based optimization technique that leverages the fundamental physics of Maxwell’s equations to efficiently optimize electromagnetic performance metrics such as transmission across different wavelengths, modes, and polarization states. The method’s computational efficiency stems from requiring only two simulations per iteration: a forward simulation to evaluate the system response and an adjoint simulation that simultaneously calculates the gradient of the objective function with respect to all design parameters. This approach enables comprehensive computation of shape derivatives across the entire design space without resorting to parameter-by-parameter perturbations. In contrast to traditional stochastic methods like particle swarm optimization (PSO), which rely on extensive random sampling and lack gradient information, the adjoint method offers significantly reduced computational costs while maintaining superior optimization performance. The initial and optimized geometries are depicted in Fig. 1a and b. The device is designed using X-cut LN core layer with a 400 nm-thick top LNOI layer (htotal) and 3 μm-thick silica layer on a silicon substrate. To address fabrication challenges associated with the dry-etching process, a slab waveguide was employed to reduce the sidewall angle and minimize waveguide loss. To ensure single-mode transverse electric (TE) polarization transmission and compatibility with the fabrication process, the height and width of the slab waveguide is 250 nm (h) and 1 μm (Wtop), respectively. The dry etching process results in waveguide sidewalls with an angle of 70∘, as provided by the commercial foundry, which is used to refine our simulation model.

Our design methodology combines adjoint algorithms with the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method, facilitating efficient design of broadband, compact multiparameter photonic devices. This combination allows for the optimization of device performance across a wide spectral range, reducing computational costs and time relative to traditional methods. Conventional waveguide crossing design approaches such as beam diffraction theory, self-imaging theory, and sub-wavelength gratings have been widely used. Some approaches such as pinhole diffraction and self-imaging, require large footprints, while sub-wavelength gratings introduce additional taper losses and higher fabrication requirements. Inverse design of waveguide crossings has been shown to be the most effective approach for achieving both compact footprints and high performance. By leveraging optimization algorithms, this method enables the realization of waveguide crossing geometries that maximize functionality while minimizing size, addressing the trade-offs between performance, footprint efficiency, and manufacturability. The common inverse-design approach is PSO to optimize structural geometry25,26,27,28. While the PSO approach typically requires many iterations to converge, especially when a large number of design parameters is involved. This results in slower convergence rates and a higher likelihood of becoming trapped in local minima, limiting the efficiency of the optimization process. Furthermore, the PSO approach is primarily suited for single-wavelength optimization, which restricts its application in broadband photonic designs where the performance must be optimized over a range of wavelengths.

The figure of merit (FOM) for the waveguide crossing is defined as FOM = \({\left\vert E({x}_{0})\right\vert }^{2}\), representing the squared magnitude of the electric field at the output port position x0. This quantity directly corresponds to the optical transmittance at the output port. Through a single forward simulation and an adjoint simulation, we can determine how geometric variations of the structure influence the FOM, enabling optimization of the waveguide geometry to maximize transmittance. To account for broadband operation across 1500–1680 nm, we compute the FOM as an average over 19 equally sampled wavelengths within this range (10 nm spacing). This approach ensures balanced performance optimization across the entire target spectrum rather than at a single wavelength. Based on reference24, a forward simulation and an adjoint simulation are sufficient to obtain the variation of the FOM, ΔFOM, over the entire optimization region. The relationship between ΔFOM and the variation in the dielectric constant Δεr is given by the following equation:

where Eadj(x) and E forward(x) are the field profiles of the forward simulation and the adjoint simulation. On the left-hand side of the equation is the derivative of the FOM with respect to the εr. The derivative in the equation can be used to modify the geometry of the waveguide crossing. Since the refractive index of the LN core layer is higher than that of the SiO2 cladding, the geometry expands outward when the derivative is positive, and contracts inward when the derivative is negative. As shown in Fig. 2a, (xi, yi) represents the geometric structure of the waveguide crossing, where xi remains fixed and equidistant. The derivative at the (xi, yi) points determines whether yi increases or decreases. Instead of performing simple interpolation between the points (xi, yi), we use a level-set method29 to represent the boundary of the structure. The level-set method allows for flexible and accurate descriptions of complex shapes and boundaries, incorporating shape derivatives, which enhances the ability to effectively explore the design space. This iterative process ensures that the design evolves toward the optimal configuration for improving the performance of the waveguide crossing.

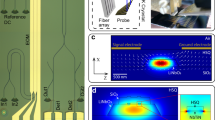

a Width parameters in the inverse design. b Simulated electric field profile within the waveguide crossing at 1550 nm, with white lines indicating the outline of the waveguide crossing. c Simulation results showing the insertion loss and crosstalk of inverse-designed device. d Process for inverse design. To achieve rapid convergence, iterations 1-41th use a 90° sidewall, and an approximate solution is obtained using varDTD. Starting from the 42th iteration, a 70° sidewall is introduced.

To maintain practical manufacturability, constraints are imposed on the maximum and minimum values of yi during the optimization process. These constraints ensure that the minimum feature size of the design meets current manufacturing capabilities, thereby preventing the optimization from producing geometries that are difficult or impossible to fabricate. Since the optimization is performed over a broad spectral range, and both LN and SiO2 are dispersive materials, the transmission at different wavelengths varies. Therefore, the FOM corresponding to each wavelength is also different. To enable the device to operate across a wide spectral range, we integrate and normalize the simulation results of the transmission spectra within the 1500–1680 nm range as the FOM to be optimized.

Unlike silicon and silicon nitride materials, LN is an anisotropic material, with different dielectric constants in different directions, which can be represented by a 3 × 3 diagonal matrix:

Although the dielectric constant of LN varies with direction, it does not affect the sign of the derivative in equation (1). The anisotropy of LN has a significant impact on the design of modulators and nonlinear devices, directly determining whether the maximum electro-optic coefficient or the nonlinear coefficient of LN can be utilized. In the design of waveguide crossings, the propagation mode and polarization state of light undergo no significant changes, remaining primarily TE-polarized, making it difficult to perceive the anisotropy of LN. The difference between the ordinary refractive index (no) and the extraordinary refractive index (ne) of LN is only about 0.07, which has minimal influence on the design of waveguide crossings. Therefore, in this work, the anisotropy of LN is neglected in the inverse design process.

In comparison, the adjoint algorithm method offers significant advantages over heuristic algorithms such as the PSO method. By calculating the gradient of the objective function with respect to the design variables, the adjoint method requires only two simulations per iteration to compute the shape derivatives at all points in the optimization region. This contrasts sharply with the multiple evaluations required by heuristic algorithms, making the adjoint method more computationally efficient. Overall, this hybrid approach, combining adjoint optimization with FDTD simulations, and using the level-set method for geometric representation, provides a powerful and efficient framework for designing complex inverse-designed photonic devices. It enables broadband optimization, ensures manufacturability, and can be extended to handle multi-parameter designs, making it particularly well-suited for the development of advanced photonic circuits.

The four arms of the crossing are identical and symmetric, with the optimized points distributed equidistantly, as shown in Fig. 2a. The widths are defined from W1 to W13, with W1 and W13 = 1 μm, connecting to the ridge waveguide. W13 remains fixed and unchanged, which results in one arm overlapping with the others. During the inverse design process, the waveguide boundaries must be continuously updated through gradient-based optimization. If a non-overlapping geometry is enforced from the outset, a more complex mathematical framework is required to maintain separation between all arms throughout the optimization iterations. This added complexity would significantly hinder convergence and computational efficiency. In contrast, our chosen configuration-where one waveguide arm overlaps with others at the center-allows us to define the entire crossing structure based on the coordinates of a single waveguide arm. This approach ensures mathematical simplicity and symmetry, promoting more efficient and stable optimization. The TE0 transmittance at waveguide crossing serves as the figure of merit for optimization, while W2 to W12 are the variables to be optimized, initially set to 1 μm for the first iteration. Through numerical investigations, we observed that the number of width parameters impacts both device performance and manufacturability. An insufficient number of parameters limits the device’s performance potential, while excessive parameters not only introduce impractical structural complexities for fabrication but also increase computational overhead. After systematic evaluation, we determined that 13 width parameters provide an optimal balance between optical performance, structural feasibility, and computational efficiency. The optimal values obtained after several iterations are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2b illustrates the contour plot of the electric field intensity at the wavelength of 1550 nm, with white lines indicating the outline of the waveguide crossing. A key design goal is to focus the light beam at the crossing point to minimize optical scattering, thereby reducing insertion loss and crosstalk. As shown in Fig. 2b, light initially transitions from the TE0 mode to multi-mode, subsequently refocusing into the TE0 mode at the crossing point due to the self-imaging phenomena caused by multimode interference. The waveguide crossing length L represents a critical design parameter that requires careful optimization. Our analysis reveals that insufficient length leads to incomplete mode conversion and poor light confinement at the intersection, resulting in significant scattering losses. As demonstrated in Ref. 18, a 6 μm SOI waveguide crossing achieves 0.18 dB loss at 1550 nm. Conversely, excessive length provides diminishing returns in optical performance while substantially increasing device footprint. Ref. 30 reports an 80 μm crossing with 0.015 dB loss, which offers only marginal improvement over the 0.028 dB loss of a 9 μm design as demonstrated in Ref. 20, despite the 18 times length increase. Based on the performance characteristics of the aforementioned Si waveguide crossings and accounting for the refractive index contrast between Si and LN, we deduced that the optimal length for LN waveguide crossings would likely fall within the 14–20 μm range. Through optimization across this interval (L = [14, 20] μm), we ultimately determined 16 μm to be the ideal length, achieving an optimal balance between compact device footprint and minimal insertion loss. Figure 2c shows the simulated insertion loss (red curve) and crosstalk (black curve) of the device. The simulation results show extremely low loss and crosstalk in the range of 1500–1680 nm, with a relatively flat curve, being below 0.1 dB and −50 dB, respectively, which indicates the inverse-design device’s capability for wide spectral operation. Figure 2d outlines the two-stage optimization methodology employed in this study. In the initial phase, we utilize Lumerical’s varFDTD solver to perform efficient quasi-3D simulations. This solver combines computational efficiency approaching that of 2D modeling with the capability to handle 3D structures, albeit with the constraint of requiring uniform device width along the z-axis (i.e., limited to 90∘ sidewall configurations). The optimization process was considered converged when the variation in transmittance remained below 0.001 for five consecutive iterations. The optimization process achieved convergence after 41 iterations, serving as an effective preliminary step to establish approximate solutions while minimizing computational overhead. Subsequently, we implement full 3D optimization using the FDTD solver, incorporating a projection function to accurately model the 70∘ sidewall profile across different vertical heights. This refined optimization stage converged within 14 iterations. The proposed hybrid approach demonstrates significant advantages in terms of computational efficiency while maintaining rigorous accuracy, as confirmed by subsequent experimental validation. This methodology effectively balances computational resource utilization with precision requirements in photonic device optimization. The adjoint algorithm is a gradient-based optimization method that predicts the trend of FOM variations, enabling convergence within significantly fewer iterations compared to heuristic approaches such as PSO.

Experimental measurements

The device was positioned in the yz plane, with the x-axis oriented perpendicular to the LN film. Figure 3a displays a microscope image of the fabricated sample. To evaluate the performance of fabricated inverse-design device, we conducted transmission spectrum measurement using the experimental setup depicted in Fig. 3c. The measurements were taken using a single PD to sequentially receive signals from each of the three output ports. The device under test (DUT) comprised 50 cascaded crossings, enabling accurate evaluation of insertion loss. Additionally, a straight waveguide was incorporated to measure the coupling loss between the lensed fiber and the chip. To ensure efficient mode matching and minimize transmission losses, inverse tapers were placed at both ends of the DUT. The inverse taper has a length of 400 μm, with a width of 0.15 μm at one end to align the mode field of the lensed fiber, and a width of 1 μm at the other end to connect with the waveguide. Light from the tunable laser source (EXFO T500S) was first passed through a fiber polarization controller to ensure that it entered the waveguide as TE0 polarized light, before being coupled into the chip via lensed fibers, which is the desired mode for optimal transmission in this configuration. At the output, output light from DUT was similarly collected by another similar lensed fibers and detected by photodetector (EXFO CTP10) for transmission spectrum characterization. This setup allowed for precise characterization of the transmission spectrum over a wide range of wavelengths. The transmission spectrum at Output 1 includes the cumulative insertion loss from the 50 cascaded waveguide crossings as well as the coupling loss from the fiber to the chip. The spectrum at Output 2, on the other hand, captures not only the coupling loss but also the crosstalk arising from the interaction between adjacent waveguide crossings. Output 3 reflects only the coupling loss, providing a baseline for comparison. By subtracting the coupling loss from both Output 1 and Output 2 and normalizing the results, we were able to accurately isolate and quantify the insertion loss and crosstalk associated with the waveguide crossings themselves.

Figure 4a presents the transmittance of the 50 cascaded waveguide crossings, along with that of the reference straight waveguide. It is apparent that the coupling from the fiber to the chip introduces an insertion loss of approximately 4 dB per facet. The oscillations observed in the spectrum can be attributed to a Fabry-Perot resonator, which is formed between the lensed fiber and the edge of the chip. Notably, despite the light traversing 50 waveguide crossings, the overall shape of the spectrum remains largely undistorted. This indicates that, while higher-order modes are excited within the crossings, the output predominantly retains the TE0 mode. This observation confirms the high quality of our designed and fabricated waveguide crossings, which are advantageous for interconnecting large-scale integrated devices. Figure 4b shows the experimental results for the insertion loss of a single waveguide crossing. The insertion loss (in dB) per crossing is obtained by taking the difference in logarithmic power values between output1 (50 crossings) and output3 (reference), then dividing by 50: IL = (Output1–Output3)/50. The minimum insertion loss reached as low as 0.05 dB, and the insertion loss is less than 0.12 dB over the 1500–1680 nm range, showing a very flat transmission spectrum. This flatness in the spectrum highlights the effectiveness of the waveguide crossing design in minimizing wavelength-dependent losses and ensuring stable performance across a broad spectral range from 1500 nm to 1680 nm.

Figure 5a and b illustrate the transmittance of output 2 and the experimental results for the crosstalk of LNOI waveguide crossing, respectively. The curve in Fig. 5b represents difference (output2–output3), which isolates the crosstalk contribution. The minimum crosstalk reached as low as −50 dB, and the crosstalk remained below − 40 dB across the wavelength range of 1500–1680 nm. These results indicate that the device effectively suppresses unwanted cross-talk between the waveguide crossings. Importantly, the experimental data for both insertion loss and crosstalk closely match the simulation results, validating the accuracy and reliability of our inverse design model and fabrication process. Our device demonstrates excellent performance with low insertion loss and crosstalk over the S, C, L, U band, all while maintaining a compact footprint of approximately 16 × 16 μm2. This combination of low loss, minimal crosstalk, and small size positions our waveguide crossing design as a promising candidate for integration into high-density photonic circuits, where efficiency and scalability are critical.

Discussion

Table 2 presents the experimental results of reported waveguide crossings from literature and the measured results of the demonstrated crossing fabricated from various materials, highlighting key metrics such as insertion loss, crosstalk, wavelength range, wavelength span, and footprint.

Among the materials listed in Table 2, Si demonstrated the lowest insertion loss, achieving an impressive value of 0.043 dB over the narrow wavelength range of 1550−1560 nm with a compact size of 14.3 × 14.3 μm2. This exceptional performance can be attributed to silicon’s high refractive index of 3.48, which enables stronger field confinement and thus minimizes waveguide loss. However, while Si offers excellent low-loss performance, it is less suitable for broadband operation, as its narrow spectral range limits its utility in applications requiring broader wavelength coverage. In contrast, LNOI and SiN devices exhibit a broader range of insertion loss values, from 0.07 dB to 0.6 dB, depending on the specific design and the wavelength span considered. Our LNOI inverse-design device shows a competitive insertion loss of 0.12 dB over an extended wavelength range of 1500−1680 nm, with a compact footprint of 16 × 16 μm2, makes it one of the most favorable lithium niobate waveguide crossings reported to date.

Crosstalk is a critical parameter for evaluating the performance of waveguide crossings, as it reflects the level of undesired coupling between adjacent waveguides. For Si, SiN, LNOI, they can exhibit exceptional crosstalk suppression. The crosstalk values ranged from −31 dB to −50 dB, which depends on the device design and operational conditions. The device presented in this work also achieved a commendable crosstalk suppression of −40 dB, indicating its suitability for high-performance photonic applications.

Wavelength range and footprint are two key parameters for evaluating the spectral flexibility of waveguide crossing devices, as it determines the operational bandwidth for broadband applications. SiN devices in Table 2, demonstrated the broadest wavelength span, covering from 1520 nm to 1640 nm (120 nm). But, this comes at the cost of a larger device size (33.3 × 33.3 μm2) and relatively higher insertion loss (0.6 dB). LNOI devices exhibit a more moderate wavelength span, ranging from 40 nm to 100 nm, depending on the specific design parameters. SiN, with a refractive index of about 1.99, is comparable to that of lithium niobate film, allowing for the fabrication of devices with a similar size and performance. The device presented in this work strikes an optimal balance between wavelength coverage and compactness, offering a wavelength span of 180 nm (1500 nm to 1680 nm) while maintaining a compact footprint of 16 × 16 μm2. The combination of a relatively wide wavelength range and small footprint makes our inverse-design LNOI device a promising candidate for broadband, high-performance photonic systems.

Device size is a critical parameter for integrating waveguide crossings into high-density photonic circuits, where minimizing footprint is essential for scalability. Si device achieves the smallest size (14.3 × 14.3 μm2), coupled with a very low insertion loss of 0.043 dB, making it highly advantageous for applications that require compact integration with minimal optical loss. This makes silicon an ideal choice for dense photonic circuits, particularly where area efficiency is paramount. In contrast, SiN and LNOI devices, while exhibiting slightly larger footprints (e.g., 39 × 32 μm2 in Ref. 17 and 49.2 × 49.2 μm2 in Ref. 16), offer significant benefits in broader wavelength spans. Despite these larger sizes, LNOI and SiN can support wider spectral operation. The device presented in this work, with a footprint of 16 × 16 μm2, balances size with performance, offering competitive insertion loss and crosstalk suppression while maintaining a compact footprint.

Although there have been reports of inverse-designed devices in recent years, these efforts have primarily focused on compact footprints and performance improvements. In this work, we demonstrate that broadband operation, a compact footprint, and excellent performance can be simultaneously achieved through inverse design. Realizing broadband operation via inverse design is challenging due to strong wavelength-dependent refractive index variations. Considering this combination of attributes, our inverse-designed device offers a novel contribution to the approach for broadband operation. Furthermore, since LNOI is a promising platform for quantum communications and high-speed photonics, our devices showcase the potential of inverse design to tailor components for broadband operation, which is essential for practical and scalable integrated photonics. Our LNOI waveguide crossing design demonstrates competitive balanced performance compared to conventional Si and SiN platform counterparts, achieving optimal trade-offs among bandwidth, insertion loss, crosstalk, and device footprint.

In summary, the inverse-design device developed in this work, fabricated from LNOI, achieves an optimal balance between key performance metrics, including low insertion loss (0.12 dB), excellent crosstalk suppression (−40 dB), a wide wavelength span (180 nm, covering portions of the S and fully C + L + U bands), and a compact footprint (16 × 16 μm2). These attributes position our device as a promising candidate for high-performance, compact, and broadband LNOI photonic circuits. Importantly, our device not only meets but surpasses the performance of many existing waveguide crossing devices in terms of both size and spectral flexibility. This outstanding performance provides significant advantages for scalable LNOI photonic integration, particularly in applications such as optical interconnects, telecommunications, and integrated sensing systems, paving the way for efficient, large-scale integration in next-generation photonic technologies.

By adopting inverse design in conjunction with adjoint algorithms and incorporating practical experimental parameters for LNOI waveguides, we have effectively addressed key challenges associated with both fabrication and broadband inverse design. The simulation predictions from our inverse-design model align closely with experimental results, confirming the accuracy and reliability of this approach. This methodology demonstrates significant potential for advancing a range of photonic devices, including grating couplers, switches, and optical combs, by optimizing device footprint and enhancing performance. Moreover, the versatility of this inverse-design approach extends across various photonic platforms, such as LNOI, silicon carbide, and diamond, making it a powerful tool for designing compact, high-performance devices in diverse photonic technologies.

To further enhance the inverse design methodology, AI-based approaches-such as variational autoencoders (VAEs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and diffusion models-can be explored. These techniques offer promising pathways toward more comprehensive, diverse, and scalable photonic design strategies. Our broadband, low-loss, and compact waveguide crossing is particularly well-suited for integration into reconfigurable photonic architectures. These include mesh-based programmable circuits for optical signal processing and quantum photonic processors, where efficient and dense routing is crucial. Moreover, since the LNOI platform supports active electro-optic modulation, our design can potentially be co-integrated with modulators, switches, and other tunable elements to form high-speed, reconfigurable photonic systems.

Methods

Device fabrication

First, the surface of the LNOI wafer was cleaned and treated to become hydrophobic, ensuring better adhesion of the photoresist to the wafer surface. Then, a layer of photoresist was spin-coated onto the wafer, and the pattern for the waveguide crossing was printed using electron beam lithography. After development and hard-baking, a photoresist mask was obtained. The mask pattern was then transferred onto the lithium niobate thin film using inductively coupled plasma dry etching. Finally, the residual photoresist was cleaned off, and a layer of silicon dioxide is deposited using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition.

Numerical simulation

Simulations were carried out using the Lumerical (Ansys) FDTD simulation package. The refractive indices of silicon and silicon dioxide are taken from Palik31. The dispersion characteristics of LN are described by the Sellmeier equation32:

The Sellmeier equation parameters for lithium niobate at room temperature are as follows: for the ordinary refractive index (no), A = 4.913, B1 = 0.1173, C1 = 0.0448, B2 = 0.2125, C2 = 0.1336, B3 = 0.0496, C3 = 662.55; for the extraordinary refractive index (ne), A = 4.5567, B1 = 0.0970, C1 = 0.0444, B2 = 0.2091, C2 = 0.1174, B3 = 0.0489, C3 = 662.08, with an applicable wavelength range of 0.4 μm to 5 μm (visible to near-infrared).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Poberaj, G., Hu, H., Sohler, W. & Guenter, P. Lithium niobate on insulator (LNOI) for micro-photonic devices. Laser photonics Rev. 6, 488–503 (2012).

Geng, W. et al. Nonlinear photonics on integrated platforms. Nanophotonics 13, 3253–3278 (2024).

Thomaschewski, M. & Bozhevolnyi, S. Pockels modulation in integrated nanophotonics. Appl. Phys. Rev. 9 (2022).

Vazimali, M. G. & Fathpour, S. Applications of thin-film lithium niobate in nonlinear integrated photonics. Adv. Photonics 4, 034001–034001 (2022).

Wang, Z., Wang, C. & Yu, H. Advances in nonlinear photonic devices based on lithium niobate waveguides. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 56, 083001 (2023).

Weis, R. & Gaylord, T. Lithium niobate: Summary of physical properties and crystal structure. Appl. Phys. A 37, 191–203 (1985).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101–104 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. High-performance coherent optical modulators based on thin-film lithium niobate platform. Nat. Commun. 11, 3911 (2020).

Feng, H. et al. Ultra-high-linearity integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators. Photonics Res. 10, 2366–2373 (2022).

Dutt, A., Mohanty, A., Gaeta, A. L. & Lipson, M. Nonlinear and quantum photonics using integrated optical materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1–26 (2024).

Han, H., Ruan, S. & Xiang, B. Heterogeneously integrated photonics based on thin film lithium niobate platform. Laser Photonics Rev. 2400649 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Hosseini, A., Xu, X., Kwong, D. & Chen, R. T. Multimode interference based ultra-low loss silicon waveguide crossing. In 2014 Optical Interconnects Conference, 137–138 (IEEE, 2014).

Han, L., Ruan, X., Tang, W. & Chu, T. Ultralow-loss waveguide crossing for photonic integrated circuits by using inverted tapers. Opt. Express 30, 6738–6745 (2022).

Bock, P. J. et al. Subwavelength grating crossings for silicon wire waveguides. Opt. express 18, 16146–16155 (2010).

Han, H.-L. et al. High performance ultra-compact SOI waveguide crossing. Opt. Express 26, 25602–25610 (2018).

Chen, G. et al. Compact 100 Gbaud driverless thin-film lithium niobate modulator on a silicon substrate. Opt. Express 30, 25308–25317 (2022).

Chen, Y., Zhang, K., Feng, H., Sun, W. & Wang, C. Design and resonator-assisted characterization of high-performance lithium niobate waveguide crossings. Opt. Lett. 48, 2218–2221 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. A CMOS-compatible, low-loss, and low-crosstalk silicon waveguide crossing. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 25, 422–425 (2013).

Yu, Z., Feng, A., Xi, X. & Sun, X. Inverse-designed low-loss and wideband polarization-insensitive silicon waveguide crossing. Opt. Lett. 44, 77–80 (2018).

Ma, Y. et al. Ultralow loss single layer submicron silicon waveguide crossing for SOI optical interconnect. Opt. express 21, 29374–29382 (2013).

Ning, N. et al. Inverse design of high extinction ration narrow-band filters based on silicon nitride multimode waveguide Bragg gratings. In AOPC 2023: AI in Optics and Photonics, vol. 12966, 491–494 (SPIE, 2023).

Yang, J., Yang, K. Y., Guidry, M. A., Lukin, D. M. & Vuckovic, J. Inverse-designed silicon carbide nanoresonators. In 2022 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO), 1–2 (IEEE, 2022).

Dory, C. et al. Inverse-designed diamond photonics. Nat. Commun. 10, 3309 (2019).

Lalau-Keraly, C. M., Bhargava, S., Miller, O. D. & Yablonovitch, E. Adjoint shape optimization applied to electromagnetic design. Opt. express 21, 21693–21701 (2013).

França-Vieira, L., Rodríguez-Esquerre, V. & Rubio-Mercedes, C. Waveguide crossing design using particle optimization algorithm. In Nanoengineering: Fabrication, Properties, Optics, Thin Films, and Devices XVII, vol. 11467, 188–191 (SPIE, 2020).

Goudarzi, K. & Lee, M. Inverse design of a binary waveguide crossing by the particle swarm optimization algorithm. Results Phys. 34, 105268 (2022).

Yuan, X., Yang, Y., Yan, X., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, X. Ultra-compact multichannel optical waveguide crossings designed by a particle swarm optimized method. Opt. Commun. 503, 127458 (2022).

Zhang, J., Li, W., Wei, Z. & Plant, D. V. Enhanced broadband silicon waveguide crossing based on pso-processed swg cladding. In 2024 IEEE Silicon Photonics Conference (SiPhotonics), 1–2 (IEEE, 2024).

Osher, S. & Sethian, J. A. Fronts propagating with curvature-dependent speed: Algorithms based on hamilton-jacobi formulations. J. Comput. Phys. 79, 12–49 (1988).

Chen, L. & Chen, Y.-k Compact, low-loss and low-power 8 × 8 broadband silicon optical switch. Opt. Express 20, 18977–18985 (2012).

Palik, E. D.Handbook of optical constants of solids, vol. 3 (Academic Press, 1998).

Gayer, O., Sacks, Z., Galun, E. & Arie, A. Temperature and wavelength dependent refractive index equations for mgo-doped congruent and stoichiometric linbo 3. Appl. Phys. B 91, 343–348 (2008).

Johnson, M., Thompson, M. G. & Sahin, D. Low-loss, low-crosstalk waveguide crossing for scalable integrated silicon photonics applications. Opt. Express 28, 12498–12507 (2020).

Sanchis, P. et al. Highly efficient crossing structure for silicon-on-insulator waveguides. Opt. Lett. 34, 2760–2762 (2009).

Lu, Z., Li, J., Chen, H., Yang, S. & Chen, M. Low-loss waveguide crossing for complicated on-chip microwave photonic processor. IEEE Photonics J. 16, 1–5 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. A broadband, low-crosstalk and low polarization-dependent silicon nitride waveguide crossing based on the multimode-interference. Opt. Commun. 450, 28–33 (2019).

Shang, C. et al. Inverse-designed lithium niobate nanophotonics. ACS Photonics 10, 1019–1026 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contribution: F.G., F.Y.Y. and X.Y.Z. designed and fabricated the device. L.Y.H. and H.L.J. conducted the experimental measurements and data analysis and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, L., Ji, H., Yue, F. et al. Broadband, high-efficient and compact inverse-designed crossing on thin-film lithium niobate platform. npj Nanophoton. 2, 43 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00094-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00094-1