Abstract

Trapped-ion quantum computing requires precise optical control for individual qubit manipulation. However, conventional free-space optics face challenges in alignment stability and scalability as the number of qubits increases. Integrated photonics offers a promising alternative, providing miniaturized optical systems on a chip. Here, we propose a design for a multimode photonic circuit integrated with a surface-electrode ion trap capable of targeted and reconfigurable light delivery. Three closely positioned ions can be addressed using a focusing grating coupler that emits multimode light through electrode openings to ions trapped 68 μm above the chip. Simulations show that the couplers achieve a diffraction-limited spot with a 4.3 μm beam waist along the trap axis and 2.2 μm perpendicular to the trap axis. Controlled interference of the TE00 and TE10 modes results in crosstalk of –20 dB to –30 dB at ion separations of 5–8 μm when addressing ions individually, and down to –60 dB when two of the three ions are addressed simultaneously. Additionally, the higher-order TE modes can offer a novel mechanism for driving spin-motion coupling transitions, potentially enabling alternative approaches to quantum gates and simulations. The proposed integrated platform offers a viable path for constructing large-scale trapped-ion systems, leveraging the benefits of nanophotonic design for precise and reliable ion manipulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum computers have the potential to solve computational problems that are beyond the capabilities of classical computers1,2,3,4 and hold transformative potential in cryptography5, complex optimization6, material simulation7, and drug discovery7,8,9. However, a scalable, low-error platform for quantum computing is yet to be established. Trapped ions are among the leading qubit platforms and have been shown to satisfy all of DiVincenzo’s criteria10. Trapped ions offer advantages in long coherence times, high gate fidelity, and all-to-all entanglement mediated by shared motional modes arising from Coulomb interactions11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Despite the promising potential of trapped ions for quantum computing, achieving scalability and portability remains a significant challenge in realizing a fully operational and practical quantum computer18,19.

For decades, free-space optics has been integral to ionization, cooling, state preparation, and the execution of coherent operations in trapped-ion systems20,21. While free-space optical systems have historically played a critical role in enabling coherent operations in trapped-ion systems, microwave-based control techniques have also gained significant traction, particularly for implementing high-fidelity single- and two-qubit gates in scalable architectures22,23. However, scaling these systems becomes increasingly impractical due to the large number of optical components required, as well as the limited optical access and alignment precision17,20,24,25, because the challenges of maintaining stable optical paths and achieving reliable qubit control grow rapidly as the number of ions increases26,27.

Integrated photonics offers a compact and scalable light delivery solution by combining optical waveguides, gratings, and modulators directly on a chip28,29,30,31. The feasibility of using integrated photonic devices to deliver light to ion traps has been shown with minimal alignment requirements14,15,16,32,33. Recent research has shown that higher-order modes such as TE10 can be used to suppress unwanted carrier transitions, which is beneficial for ground-state cooling applications34. These approaches aim to minimize off-resonant carrier coupling during sideband cooling by shaping the light field spatially using standing waves or Hermite–Gaussian profiles. However, engineered beam profiles offer advantages beyond laser cooling and can be beneficial in various other applications.

Efficient coupling of light into and out of thin optical waveguides remains a key challenge due to the moderate index contrast and limited radiation strength. Vertically symmetric gratings are fundamentally constrained to a 3 dB coupling limit, as power is equally split between upward and downward diffraction. The coupling efficiency depends on the grating’s scattering strength (η1), overlap with the fiber mode (η2), and directionality (η3). Apodized gratings can enhance η1 and η2 by spatially tailoring the scattering profile, while achieving high η3 typically requires back-reflectors or structural refinement35,36. These improvements reduce higher-order diffraction and beam divergence, enhancing light delivery to ion qubits35,37. Designing such gratings requires optimization algorithms capable of handling complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces. While traditional methods like parameter sweeps and metaheuristics are computationally intensive38,39,40,41,42,43, gradient-based optimization (GO) offers a scalable alternative. GO efficiently converges to optimal designs using only two simulations per iteration, making it well-suited for inverse design of nanophotonic components44,45,46,47.

In this work, we propose the design of a photonic integrated circuit (PIC) for precise optical addressing of each of the three closely grouped calcium ions. Our design achieves individual ion addressing enabled by the interference of the TE00 and TE10 modes, with a crosstalk of −21.1 dB at a lateral distance of 5 μm from the center ion and −31.5 dB at 8 μm. To address two neighboring ions with the TE10 mode, the crosstalk to the center ion is reduced to −60 dB. The device is designed for a target wavelength of 729 nm, corresponding to the quadrupole transition used for qubit operations in trapped 40Ca+ ions. The compact footprint of the PIC, measuring only 16 × 45 μm2, enhances the scalability of the system. The focusing efficiency is defined as the ratio of optical power collected in a 5 μm × 5 μm monitor region at the ion trapping height (68 μm above the trap electrodes) to the optical power at the input of the grating coupler, just before the first grating tooth. This isolates the performance of the grating element and reflects how effectively it delivers light to the focal spot. We achieve a focusing efficiency (FE) of −3.8 dB, corresponding to the optical power effectively delivered to the trapped ions at the trapping height. The proposed grating coupler, combined with on-chip phase and intensity modulation using integrated optics, provides a powerful platform for the scalable manipulation of trapped ions. In this work, the modes are labeled as TEmn to indicate the number of intensity minima along the lateral (m) and vertical (n) dimensions within the waveguide cross-section. Hence, TE00 corresponds to the fundamental mode, and TE10 corresponds to the first higher-order mode along the lateral direction.

While our work is focused on simulation and theoretical design, practical implementation of multimode photonic circuits has been well developed in recent years. In the infrared wavelength range, silicon photonics platforms have demonstrated high-performance mode-division multiplexers, asymmetric Y junctions, and multimode interferometers operating with insertion losses below 2 dB and crosstalk under −15 dB, making them relevant benchmarks for mode control and routing48,49,50. Analogous work in the visible and near-visible regime has emerged on silicon nitride platforms, with demonstrated mode-division devices and resonators enabling selective TE00/TE10 operation and even nonlinear comb generation via higher-order dispersion control. These advances support the feasibility of selective higher-order mode excitation in our wavelength regime (729 nm). Importantly, silicon nitride waveguides integrated with oxide cladding layers are compatible with existing surface-trap RF electrode architectures, facilitating layered integration of optical routing above the ion trap electrodes without compromising electrical functionality. This establishes a clear experimental path for translating our theoretical grating designs to scalable trapped-ion control systems.

Results

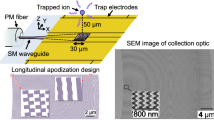

Figure 1a provides a schematic overview of the planar trap electrodes on the surface, with waveguides and beamforming elements located 12 μm beneath the top surface. Among the candidate ions, we selected calcium ions (40Ca+) due to their well-characterized energy levels, efficient laser cooling, and compatibility with accessible laser wavelengths15,32,51,52,53. Figure 1a, top-left, includes an energy-level diagram for the 40Ca+ ion, indicating the 729 nm wavelength used for coherent qubit operations. The ions are trapped 68 μm above the surface in five distinct zones, with each zone containing three ions. To accommodate fabrication tolerances and optimize trapping performance, multiple grating variations have been positioned at different distances from the trap centerline (d1 and d2). The device cross-section in Fig. 1b illustrates forward-emitting diffraction to three 40Ca+ ions trapped along the Y-axis. Single-ion addressing in our architecture relies on the selective excitation of higher-order modes within a multimode waveguide. In our work, the modes are generated through a combination of adiabatic directional couplers (ADCs) and multimode interferometers (MMIs). The ADC gradually transitions a fundamental input mode (TE00) into a higher-order mode (e.g., TE10) by adiabatically varying the waveguide width, providing low-loss mode conversion. The MMI structure then enables coherent multiplexing of two distinct modes onto the same multimode bus waveguide with controlled amplitude and phase. The full sketch is illustrated in Fig. 1c. This configuration ensures that each mode can be launched independently and tuned prior to reaching the grating coupler, where their controlled interference produces tightly focused spots for single-ion targeting. This approach is compatible with both free-space modulation (in the current implementation) and fully integrated on-chip modulators in future iterations54,55,56. The top gold (Au) layer represents trap electrodes that generate the electric field required for ion confinement, and the second Au layer is used as a ground plane to shield against unwanted noise. Oxide layers with thicknesses of 5 μm provide optical confinement. We chose silicon nitride (SiN) as the platform due to its low propagation loss, wide transparency window, and compatibility with complementary metal-oxide semiconductor fabrication processes.

a Conceptual illustration (not to scale) of the designed surface trap with ions, integrated waveguides, and beamforming elements underneath at multiple zones. Ions are trapped at one of the positions marked by the green dots, H = 68 μm above the electrodes, with appropriate potentials applied to the DC and radio-frequency (RF) electrodes. The distances from the grating to the centerline of the trapping region are denoted as d1 = 30 μm and d2 = 100 μm. Top-left shows the energy-level diagram for 40Ca+. b Material stack of final ion trap devices, showing the integrated multimode waveguides and beamforming element beneath the surface-trap electrodes and light diffracting out of the chip by means of an apodized grating. Indium tin oxide (ITO) protects the ions from interface/substrate charging at the cost of reduced out-coupling efficiencies. c Full schematic from input waveguide to the ions’ location, including multimode interferometer (MMI), adiabatic directional coupler (ADC), and grating coupler. The phase of each input source is adjustable using an external acousto-optic modulator.

The effective refractive index (neff) and propagation constant (β) in waveguides are distinct for each mode:

where m and n are the mode indices, λ is the wavelength of the laser beam. For a mode to be confined within the waveguide, it must satisfy the condition for total internal reflection \({k}_{{\rm{0}}}{n}_{{\rm{clad}}} < \beta < {k}_{{\rm{0}}}{n}_{{\rm{core}}}\), where nclad and \({n}_{{\rm{core}}}\) are the refractive indices of the cladding and core materials, respectively. The width of the waveguide is chosen to ensure support for the TE00 and TE10 modes, while cutting off higher-order modes with a free-space wavenumber of \({k}_{{\rm{0}}}=\frac{2\pi }{\lambda }=8.62\)μm−1. Figure 2a shows the effective index of the guided modes, where higher-order modes emerge at larger waveguide widths. Insets depict the mode profiles for a width of w, highlighting the transition from weak confinement for the TE20 to strong confinement for the TE00 and TE10. The dashed line marks the chosen waveguide width, which efficiently supports the propagation of TE00 and TE10 modes. The bottom-right inset illustrates the cross-sectional structure of the waveguide, where a SiN core (refractive index \({n}_{{\rm{core}}}=2.0\)) is embedded in an oxide cladding (refractive index nclad = 1.44) atop the silicon substrate. Figure 2b highlights the relationship between the waveguide width and the mode effective area (MEA), demonstrating how the waveguide dimensions affect the supported modes’ areas and the cutoff for higher-order modes. The dashed line indicates the selected waveguide width that supports the TE00 and TE10 modes, while effectively suppressing higher-order modes due to their sharp transition into radiation modes and reduced confinement within the physical area of the waveguide. The numerical modal analysis of the waveguide, based on the propagation constant βm,n, ensures double-mode operation within the defined width range of w < 0.61 μm. The cross-sectional area of the designed waveguide is 0.22 × 0.6 μm2. The waveguide thickness of 220 nm was selected to match the standard silicon device layer thickness offered by the semiconductor foundry, enabling single-mode operation and compatibility with established fabrication processes.

To enable multi-ion addressing, we designed a beamforming element optimized to suppress crosstalk, maximize focusing efficiency, and minimize the beam spot size. By dynamically mixing two waveguide modes, the grating enabled beam shaping for selective addressing of three ions in reconfigurable spatial configurations. The grating coupler design process began with optimization using the fundamental TE00 mode to establish a baseline geometry capable of high-efficiency focusing at the ion plane. After achieving this result, we applied the same grating structure to higher-order input modes and their coherent superpositions. The grating maintained strong focusing behavior and spatial selectivity across all tested inputs. These results indicate that the grating’s apodization profile is robust to changes in input modal shape, enabling reconfigurable, mode-controlled light delivery for ion addressing. This flexibility is particularly important for implementing dynamic control schemes, such as selective ion targeting or beam steering, without the need for separate gratings for each mode.

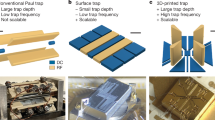

We started by designing a two-dimensional (2D) uniform grating coupler (UGC) as shown in Fig. 3a using a longitudinal approach33 to achieve positive emission angles, focusing on the 2D cross-section along the grating centerline (x–z plane). Emission characteristics, including the emission angle (θ) and grating strength (ξ), are primarily influenced by the grating period (Λ) and the duty cycle (D), which defines the ratio of the SiN-filled region to the total period; see Supplementary Fig. S1c, d. The grating strength ξ quantifies the exponential decay of the guided mode amplitude along the grating, expressed as I(x) = I0 e−ξx. The allowable range for the grating period is governed by the Bragg condition, ensuring efficient out-coupling and providing the desired emission angle. This condition is given by:

where neff is the effective refractive index approximated by a linear interpolation as \({n}_{{\rm{eff}}}\approx D{n}_{{\rm{core}}}+(1-D){n}_{{\rm{clad}}}\), θ is the emission angle, and m = 1 is the diffraction order. We investigated the TE00 mode at λ = 729 nm, suitable for the coherent control of 40Ca+optical qubits, with SiO2 as the cladding material57,58. Note that the emission angle θ in Eq. (2) is defined relative to the cladding index nclad, which is used in the simulation. For practical applications involving emission into air (n ≈ 1), the external emission angle can be determined using Snell’s law: \({n}_{{\rm{clad}}}\sin {\theta }_{{\rm{clad}}}=\sin {\theta }_{{\rm{air}}}\). Fabrication constraints were imposed by a minimum feature size of 200 nm and a minimum spacing of 100 nm, as imposed by foundry fabrication processes. The grating strength demonstrates the impact of substrate and oxide-vacuum interface reflections, heavily influenced by the top and bottom oxide layers with thicknesses of 5 μm.

a The uniform grating coupler (UGC) demonstrates a broad diffraction profile with weak focusing corresponding to a periodicity of 1.2 μm and a duty cycle of 0.25. The target-focused location is labeled with a black star, which is 80 μm above the waveguide layer (68 μm above the trapping electrodes). b The focusing grating coupler (FGC) enables enhanced focusing with a focal spot size of 5.5 μm corresponding to a periodicity of 0.71 μm, duty cycle of 0.6, and a linear apodization factor of 0.001. c Adjoint-based apodized focusing grating coupler (AAFGC) features an emission angle of 34°, a numerical aperture (NA) of 0.18, and focusing to a spot of 2.22 μm; the diffraction-limited spot size is 2 μm. The grating couplers were designed using 2D FDTD simulations for the wavelength of 729 nm, with the fundamental TE00 mode as input, 40 gratings, and full etch depth. d, e Waveguide cross-sections displaying the quasi-TE mode profiles for the TE00 and TE10 modes in the proposed material stack. f Efficiency and loss analysis of the AAFGC. The panel shows end-scattering (ES), back reflection (BR), downward diffraction (DD) losses, coupling efficiency (CE), and focusing efficiency (FE). g–i 3D simulated intensity patterns of AAFGC at the trap height along the X and Y directions for the TE00 and TE10 modes and their combinations with \(\frac{\beta }{\alpha }\) = 2.22 to address Ion B and −2.22 to address Ion C. j, k Intensity distributions calculated using MATLAB by coherently superposing the TE00 and TE10 mode fields from 3D FDTD simulations at the ion height. These plots illustrate how varying the input amplitude ratio causes lateral displacement of the focal lobe due to the modal interference.

To surpass the performance of the UGC, a particle swarm algorithm is employed for the coarse initialization of key design parameters. For a linearly apodized grating, the D is spatially varied along the waveguide as: D(x) = D0 − Rx, where D0 denotes the initial duty cycle, and R is the apodization rate. D0 = 1 corresponds to a fully solid waveguide; we used a reduced value of D0 = 0.95 to mitigate the fabrication challenges associated with subcritical trench dimensions. Figure 3b shows the designed FGC with a beam spot size of 5.5 μm and a focusing efficiency of −4.5 dB. This performance is limited by the coarse optimization capabilities of the particle swarm algorithm, which struggles to effectively explore high-dimensional parameter spaces. Achieving further improvements in beam confinement and efficiency necessitates the use of inverse-design techniques, such as adjoint-based optimization.

To further enhance the performance of the FGC, GO was employed, enabling efficient exploration of the high-dimensional design space47. The optimization process was conducted under realistic fabrication constraints, including fixed etch depth, layer thickness tolerances, and a minimum feature size of 200 nm. The AAFGC exhibits improved beam focusing, reduced side lobes, and enhanced radiation efficiency. The optimization results are shown in Fig. 3c, highlighting the spatial profile of the output field and the effectiveness of the tailored apodization. To optimize multiple performance metrics concurrently, we defined separate figures of merit (FOMs) corresponding to focusing efficiency, side-lobe suppression, coupling efficiency, and downward diffraction. Each FOM was evaluated independently and combined into a single composite objective function according to \({F}_{{\rm{total}}}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{4}{w}_{i}{F}_{i}\), where Fi denotes the value of the ith FOM and wi represents its weighting coefficient. The weighting factors were empirically determined through preliminary optimization runs to balance the trade-offs among the four target metrics. In this work, we used w1 = 3, w2 = 3, w3 = 2, w4 = −1, emphasizing focusing efficiency and side-lobe suppression while maintaining control over coupling efficiency and downward diffraction. This weighting scheme ensured that no single FOM dominated the optimization process and that convergence remained stable across iterations. Additionally, we confirmed that moderate variations in the weights produced consistent final device geometries, indicating robustness of the optimization outcome to small perturbations in the weighting parameters. Extending from the 2D design, we introduced curvatures to the grating lines to achieve three-dimensional (3D) control over the effective refractive index (neff) and phase. The final design, incorporating a mode-expanding taper and a series of curved grating lines with varying periods, duty cycles, and radii of curvature, optimized coupling efficiency and ensured accurate light delivery near the ion location.

Higher-order modes supported by the multimode waveguide (such as TE00 and TE10) propagate with distinct effective indices, leading to differences in their phase velocity and emission characteristics at the grating coupler. In our design, these phase differences are actively compensated using an external phase modulator placed on the TE10 mode path. By tuning this modulator, we align the phase of the TE10 mode relative to the TE00 mode at the input of the grating, ensuring coherent superposition at the emission plane. In addition, the free-space setup uses external polarization control to tailor the beam’s polarization, which is essential for selectively driving specific dipole-allowed transitions in the trapped ion. This approach allows constructive interference and optimal focusing, while avoiding degradation in efficiency or beam quality due to modal dispersion. Future work will explore full on-chip integration of these phase modulators, for example, using thermo-optic SiN modulators, to realize a monolithic multimode control system.

Figure 3f demonstrates the simulated efficiency and losses of the beamforming element, which include coupling efficiency (CE), focusing efficiency (FE), and losses containing end-scattering (ES), downward diffraction (DD), and back-reflection (BR) loss to the input port. DD refers to the fraction of optical power diffracted downward through the chip (opposite to the intended upward emission); CE is the ratio of optical power coupled into the air relative to the power at the input waveguide at 5 μm above the surface of the chip; FE is defined as the optical power collected in a 5 μm × 5 μm region at the ion plane (68 μm above the chip) divided by the power at the grating input; and BR is the ratio of the optical intensity at the input of the grating coupler back reflected to the laser59. Figure 3g–i shows the resulting intensity profiles of the light emitted along the X and Y directions for the four configurations. The optical field profiles were obtained using full 3D FDTD simulations. The monitor used to evaluate beam shape was placed at the ion trapping height, 68 μm above the chip. The field snapshots in Fig. 3g–i correspond to xy-plane intensity distributions at this elevation, capturing the light focused by the grating for various input modes. The focusing region at the ion plane of each coupler for the fundamental mode has an area of 2.22 × 4.25 μm2. To evaluate the effect of ITO losses, we performed additional simulations including a 50 nm ITO layer as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. The focusing efficiency was reduced from −3.8 dB to −4.99 dB, corresponding to a 10% decrease. This reduction is primarily due to absorption and interference introduced by the ITO layer. While this introduces some performance degradation, the overall focusing and addressing remain effective, and future work will focus on optimizing the ITO thickness and placement to mitigate these losses. A comprehensive AAFGC design overview is provided in the Methods section and Supplementary Material.

Consider a scenario where three ions are trapped 68 μm above the photonic chip. We explore four distinct ion addressing configurations to implement targeted light delivery for quantum operations. Configuration 1 involves selectively addressing the center ion (Ion A); configuration 2 targets the two outside ions (Ions B and C) simultaneously; configuration 3 focuses on Ion B, while configuration 4 addresses Ion C. To accomplish this, we manipulate the beam profiles by employing different input modes and combining them as needed. For configuration 1, we use the TE00 mode, which provides a well-centered and focused beam, ensuring exclusive light delivery to the Ion A. In configuration 2, addressing both outside ions simultaneously is achieved using the TE10 mode, minimizing unintended exposure to the center ion. For configurations 3 and 4, we employ a linear combination of the TE00 and TE10 modes. The general form of this combination is expressed as:

where α and β are adjustable coefficients determining the relative contribution of each mode. By tuning the amplitude and phase of these modes, we can generate asymmetric beam profiles that direct the light to the desired ion; see Fig. 3j, k. To study the reconfigurability of the focal position, we extracted the electric field data from 3D FDTD simulations at the ion trapping height and performed coherent superpositions of the TE00 and TE10 mode fields in MATLAB. By varying the input amplitudes of these modes, we calculated the resulting intensity distributions and observed controlled lateral shifts in the focal spot, as shown in Fig. 3j, k. This approach accurately reflects diffraction and angular effects since it is based on full-wave FDTD data rather than analytical approximations. This mode engineering strategy provides a robust and adaptive solution for multi-ion addressing in trapped-ion quantum systems.

Crosstalk suppression is crucial in trapped-ion systems as it directly impacts the fidelity of quantum operations18,19,25,60. The intensity distributions shown in Fig. 4 were calculated using MATLAB-based post-processing of the electric field data obtained from full 3D FDTD simulations. Specifically, we used the field profiles of the TE00 and TE10 modes at the ion trapping height with corresponding amplitudes (α and β) and generated their coherent superpositions by varying their complex amplitudes. The resulting total electric fields were then squared to compute the intensity distributions right at each ion’s location. Additionally, the optical intensity at the positions of three ions as a function of \(\frac{\beta }{\alpha }\). By tuning \(\frac{\beta }{\alpha }\), the optical focus shifts along the ion chain, enabling selective excitation of individual ions while minimizing light delivery to the neighboring sites. The figure demonstrates strong localization with crosstalk suppression, reducing unwanted signal to approximately CBC = CBA = −31.5 dB for non-targeted ions at \(\frac{\beta }{\alpha }=-2.22\), where ion B is selectively addressed. At β = 0, only the fundamental mode is excited, resulting in the focusing on Ion A with crosstalk levels of CAC = CAB = −21.1 dB. As α approaches 0, Ions B and C are addressed, with the intensity at Ion A minimized, leading to crosstalk levels below CBA = CCA = −60 dB. The achieved levels are generally suitable for many quantum information processing tasks61,62,63.

The plot illustrates the capabilities of the chip to minimize crosstalk between the ions, showing the crosstalk coefficients (Cij) for various \(\frac{\beta }{\alpha }\) values. The green arrows indicate optimal positions for addressing ion B, A, and C (left to right), respectively. The results provide insight into the selective light delivery and crosstalk suppression in the system.

In trapped-ion experiments, the Rabi-frequency crosstalk scales with the square root of the laser-intensity crosstalk, so a −30 dB laser-intensity crosstalk corresponds to a −15 dB Rabi-frequency crosstalk. Since the single-qubit gate infidelity scales with the square of the Rabi-frequency crosstalk, this leads to a gate infidelity of roughly −30 dB. Moreover, several crosstalk-mitigation strategies can further reduce this error. For single-qubit gates, dynamic decoupling via composite pulse sequences can efficiently suppress crosstalk errors over a large range of physical error amplitudes64. For two-qubit gates, circuit-level crosstalk-mitigation techniques can suppress first-order crosstalk errors65, thereby relaxing stringent isolation requirements. Finally, we note that an intensity crosstalk level of −30 dB is comparable to the most recent experimental results62,63.

In ion traps, ions are typically confined by oscillating RF fields in two radial directions and static fields in the axial direction66. The equilibrium position is located at the minimum of the combined potential formed by the static field from the DC electrodes and the pseudo-potential generated by the RF field. As a result, any imperfections in the trapping electrodes can affect the ion trap’s performance. Previous studies have demonstrated various types of surface-electrode traps with solid performance67,68, including grating couplers15,69. These couplers, positioned beneath the DC or RF electrodes, can introduce perturbations to the ion confinement potentials.

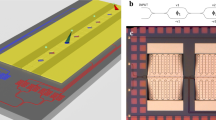

In our design, the grating couplers are positioned beneath the RF electrodes (Fig. 5a), necessitating an opening in the center of the long RF rail to allow light transmission. To evaluate the impact of this opening, we use the boundary element method (BEM; see “Methods” section) to analyze its effect and compare it with regions without grating couplers. Our results, shown in Fig. 5b, indicate that the predicted trapping height remains approximately 68 μm, with a difference of less than 0.5 μm between the two cases, suggesting a negligible perturbation of trapping performance due to the openings.

a A section of the trap’s layout. b The pseudo-potential generated by the RF electrodes at the location of the ion (star in a). X and Z represent directions parallel and perpendicular to the trap surface, respectively. The color gradient illustrates the potential, revealing a minimum near (X, Z) = (0, 68) μm. All dimensions in the figure are in micrometers (μm).

Discussion

This study proposes a design for integrating photonic devices into a surface ion trap, allowing for the delivery of light to each ion in a multiple-ion chain. This capability offers significant advantages for the trapped-ion technology, while the integrated approach enhances stability and reproducibility. Below, we outline some potential applications of our design. Importantly, by increasing the number of coupled waveguide modes TEmn and TMmn, the number of addressable ions can be scaled up accordingly.

Measurement is typically the final step in a quantum circuit, providing the final quantum states of the qubits, which constitute the quantum information. Recent advances have developed strategies for mid-circuit measurements70,71, which are particularly valuable for simulating measurement-induced quantum phase transitions72,73,74 and conducting quantum error corrections75, which require the measurement of ancilla qubits during the execution of the circuit. A recent study70 demonstrated the capability to perform individual measurements on an ancillary ion by tightly focusing the detection laser beam. The study reported minimal interference with the spin state of neighboring data ions during the measurement, thereby highlighting the feasibility of mid-circuit measurements. In contrast to the free-space optics employed in ref. 70, integrated photonic devices offer superior laser stability, as they are co-located on the same chip as the ion trap, thereby sharing common mechanical and thermal fluctuations and providing exceptional laser coherence. Moreover, integrated photonic devices facilitate system scaling to multiple distant zones, where a single high-NA lens would struggle to cover all regions effectively.

Individually implemented gates are particularly crucial for long ion chains, where multiple ions are confined within the same trapping potential and ion shuttling is infrequent76. In such scenarios, individual control of specific ions relies on tightly focused laser beams targeting the desired ions. Various techniques have been developed to achieve individual addressing, including multi-channel acousto-optic modulators77, microelectromechanical systems78, and acousto-optic deflectors52. These methods have demonstrated high-fidelity qubit operations and effective individual control. However, these addressing systems are typically bulky and assembled outside the vacuum chamber. Mechanical fluctuations along the beam path can lead to qubit decoherence. In contrast, our approach offers inherent stability and the potential to enhance qubit coherence times.

The operation of trapped-ion systems is primarily based on laser-ion interactions, specifically the interaction between the electric field of the laser beam and the dipole or quadrupole moment of the ions. Current studies normally utilize Gaussian beams to drive ion transitions, assuming a uniform electric field at the ion’s position under ideal beam alignment. In this scenario, the sideband transition, which is critical for implementing two-qubit gates and motion-related quantum simulations77,79, is generated by the laser interacting with the first order of Taylor expansion of the ion’s position operator. Control over whether the laser couples to the zero-order term (carrier transition) or the first-order term (sideband transition) is achieved by tuning the laser frequency to the corresponding resonance. However, in this case, the unwanted off-resonant coupling to carrier transitions is unavoidable when driving sidebands, introducing errors in quantum operations34. Moreover, the strength of the sideband coupling is suppressed by the Lamb-Dicke parameter80, typically around 0.1. This strength will be further reduced when dealing with higher-order sideband transitions, which are preferred in quantum simulations81 and multi-qubit operations82.

Recent studies have proposed leveraging structured light as an alternative method for coupling the laser field to the motional modes of ions, potentially circumventing the coupling limitations imposed by the Lamb-Dicke parameter with standing wave34 and providing carrier-free sideband operations with Hermite-Gauss mode34,83. Carrier-free two-qubit gates have also been demonstrated with Hermite-Gauss mode excitation84. In this context, the integrated photonics approach proposed here is highly suitable. By configuring MMIs, it becomes possible to switch between the TE00 and TE10 modes, allowing precise control over coupling to carrier transitions and motional sidebands.

Compared to prior multimode grating designs, our adjoint-optimized approach provides significant performance and manufacturability advantages. In ref. 85, for instance, multimode emitters were demonstrated to be designed via parameter sweeps and analytical apodization. The paper reported coupling efficiencies of − 3.2 dB to −2.2 dB and side-lobe suppression near −15 dB under single-mode excitation, with further degradation observed for multimode operation utilizing negative-angle diffraction with a minimum feature size around 50 nm. In contrast, our method achieves focusing efficiency of −3.8 dB and side-lobe suppression better than −25 dB, while simultaneously minimizing downward diffraction and maximizing upward coupling. A critical feature of our workflow is the incorporation of fabrication constraints from the common semiconductor foundry silicon nitride platform, including a limited minimum feature size, which necessitates positive-angle diffraction geometries but ensures compatibility with scalable foundry processes. By directly optimizing multiple figures of merit and compensating for phase and amplitude mismatches between the TE00 and TE10 modes, the adjoint framework enables a level of control and efficiency not attainable with conventional design methods and offers a clear path toward practical integration in trapped-ion quantum processors.

The apodized grating coupler is designed with curved grating teeth to achieve precise lateral focusing and high-efficiency light extraction. The emission angle of the guided modes is determined by the phase-matching condition (Eq. (2)), which represents the local grating period along the curved profile. While the fundamental TE00 and first-order TE10 modes exhibit different effective indices due to their distinct confinement characteristics, the interplay of apodization and curvature ensures that both modes emit at nearly identical far-field angles. The apodized duty cycle gradually modulates the local coupling strength, and the curvature aligns the grating vector toward the target emission direction, effectively averaging out variations arising from mode-dependent confinement. As a result, the TE10 mode, despite its slightly lower effective index, contributes to a collimated far-field beam overlapping with the TE00 emission, while minimizing back-reflections and preserving high coupling efficiency.

Our theoretical results assume near-perfect control of amplitude and phase for the TE00 and TE10 modes, enabling exceptionally high extinction ratios. In real experimental systems, however, control is limited by phase instabilities, amplitude fluctuations, and drift in AOMs, driven by RF source noise, thermal effects, and mechanical jitter. Prior studies report phase noise contributions at offset frequencies ranging from 1 kHz to 100 kHz, resulting in integrated phase errors of a few degrees and relative amplitude noise at the percent or sub-percent level48,86,87,88,89. An extinction ratio analysis was conducted to quantify the influence of a 10% phase shift on crosstalk coefficients. The results reveal that CCA, CBC, and CBA experienced an increase of approximately 5 dB, whereas CAC and CAB exhibited a negligible change of only 0.04 dB.

In summary, we designed and optimized integrated photonic components for selective light delivery to three close 40Ca+ ions, employing phase control for beamforming to generate tailored light patterns at the ion sites. Through adjoint optimization, we developed focusing grating couplers with a focusing efficiency exceeding − 3.8 dB, while maintaining an insertion loss below 2.7 dB across the operational wavelengths. The beamforming achieved diffraction-limited spots, with crosstalk levels ranging from −20 dB to −30 dB when exciting the neighboring ions using the fundamental mode and −60 dB when the two outer ions are addressed simultaneously. The proposed mode-based beamforming approach offers a versatile and reconfigurable solution for precise light delivery in various ion configurations without free-space optics, paving the way for scalable and efficient implementations in trapped-ion quantum technologies.

Methods

Design procedure

The mode properties (mode distribution and effective refractive index) of the guided modes in the SiN waveguides are calculated by using the finite-element method (FEM), and optical simulations were performed using Lumerical FDTD (Ansys Inc.), with GO performed via Ansys Lumerical Python APIs, which provide lumapi automation capabilities, and lumopt module. The design process is broken down into distinct steps:

-

Material Stack and Grating Structure Design: The material stack and grating coupler structure are designed while considering fabrication constraints, including limitations on etch depth, minimum feature size, and layer thicknesses. These factors influence the achievable grating parameters and emission characteristics.

-

Look-Up Table Generation: A comprehensive look-up table is generated by simulating the emission angle, decay constant, and effective index across a broad range of D and grating periods Λ. The objective is to ensure a positive emission angle (θ > 0) within the operational wavelength. Uniform gratings are used for this preliminary analysis, and the results are presented in Fig. S1.

-

Coarse Initialization: A linear apodization profile was applied to the uniform grating coupler (UGC) design, and coarse optimization using a particle swarm algorithm was employed to identify near-optimal initial parameters for subsequent adjoint-based refinement.

-

Adjoint Optimization Initialization: The initial parameters obtained from step 3 serve as the starting point for the apodization of the FGC using adjoint optimization. Proper initialization is critical for the convergence of the optimization process, and poor initialization can lead to prolonged runtime and convergence failures.

-

Figure of Merit (FOM) Definition: Multiple FOMs are established based on the design goals, which include minimizing optical crosstalk, maximizing the focusing efficiency at a specified focal position and height, and reducing the focused beam spot size close to the diffraction limit (λ/2NA). A minimum of three FOMs is applied, each weighted according to its priority to balance the design trade-offs.

-

2D Optimization: To reduce computational overhead, the initial optimization is performed in two dimensions. This enables faster convergence while capturing key design characteristics.

-

3D Optimization: Following the 2D optimization, the design is expanded to 3D. The waveguide width is optimized to ensure support for the two target modes, TE00 and TE10, while suppressing higher-order modes. Additionally, the width of the AAFGC is further refined to achieve optimal focusing along Y based on the desired focal distance and beam spot size. Curved grating teeth are employed to enhance focusing efficiency (FE) by reducing mode mismatch and minimizing back-reflection losses. The optimized opening angle and taper length are presented in Fig. S2.

-

Adiabatic Directional Coupler: A mode converter is employed to transition between a single-mode input and the multimode waveguide supporting TE00 and TE10. The converter is carefully optimized to minimize insertion losses and ensure high overlap with the desired modes, as illustrated in Fig. S3, where the mode-dependent spatial shift is also analyzed.

-

Multimode Interferometer (MMI): A multimode interferometer is integrated to enable coherent power mixing of the TE00 and TE10 modes. The MMI geometry is optimized for the equal-power distribution with minimal phase mismatch, providing robust mode control within the multimode section of the circuit. The simulated mode profile at the output plane confirms successful mode excitation, as shown in Fig. S4.

BEM simulation

The properties of electrodes, including RF potentials and trapping stability, are analyzed using Boundary Element Method (BEM) simulations. The workflow consists of distinct stages:

-

Trap Model Creation (STL Format): The trap geometry is modeled using computer-aided design (CAD) software like Fusion 360, ensuring that it is in accordance with optical coordinate conventions (trap axis along the Y-axis). The electrodes are distinctly colored using a predefined BEM-compatible color scheme to clearly differentiate the individual electrodes. The trap model is exported as a binary STL file with embedded electrode-identification attributes.

-

Mesh Preparation in BEM: The exported STL file is imported into BEM and re-meshed with refined mesh density to accurately resolve electrode features. Mesh integrity is confirmed through 3D visualization to ensure proper representation of electrode boundaries and surface discretization.

-

Electrostatic Simulation: Electrostatic simulations are performed using BEM to calculate the potential distributions generated by each individual electrode. For DC electrodes, unit voltages are applied sequentially to each electrode while grounding the others, enabling precise characterization of their individual contributions to the total trapping potential. For RF electrodes, the time-averaged pseudo-potential is computed to evaluate confinement in the radial directions. Simulations can be executed locally or on a high-performance computing cluster (Berkeley HPC, Savio), depending on computational complexity and desired resolution.

-

Result Analysis: The simulation outputs, including electrode potentials, electric field distributions, and surface charge densities, are visualized and analyzed in 3D. Further detailed multipole analysis and derivative evaluations, essential for trapping performance characterization, are conducted using the PaulTrapAnalysis Python package. This comprehensive evaluation ensures accurate predictions of trap characteristics, stability, and the impacts of photonic integration cut-outs.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Feynman, R. P. Simulating physics with computers. Int. J.Theor. Phys. 21, 467–488 (1982).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2, 79 (2018).

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865–942 (2009).

Shor, P. W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proc. 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Santa Fe, NM, USA 124–134 (IEEE, 1994).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J. & Gutmann, S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/abs/1411.4028 (2014).

Aspuru-Guzik, A., Dutoi, A. D., Love, P. J. & Head-Gordon, M. Simulated quantum computation of molecular energies. Science 309, 1704–1707 (2005).

Biamonte, J. et al. Quantum machine learning. Nature 549, 195–202 (2017).

Montanaro, A. Quantum algorithms: an overview. npj Quantum Inf. 2, 1–8 (2016).

DiVincenzo, D. P. The physical implementation of quantum computation. Fortschr. Phys. Prog. Phys. 48, 771–783 (2000).

Wineland, D. J. et al. Quantum information processing with trapped ions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 361, 1349–1361 (2003).

Chiaverini, J. et al. Surface-electrode architecture for ion-trap quantum information processing. Quantum Inf. Comput. 5, 419–439 (2005).

Mehta, K. K. et al. Ion traps fabricated in a CMOS foundry. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 044103 (2014).

Mehta, K. K. et al. Integrated optical addressing of an ion qubit. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 1066–1070 (2016).

Mehta, K. K. et al. Integrated optical multi-ion quantum logic. Nature 586, 533–537 (2020).

Ivory, M. et al. Integrated optical addressing of a trapped ytterbium ion. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041033 (2021).

Bruzewicz, C. D., Chiaverini, K., McConnell, R. & Sage, J. M. Trapped-ion quantum computing: progress and challenges. Appl. Phys. Rev. 6, 021314 (2019).

Blatt, R. & Wineland, D. Entangled states of trapped atomic ions. Nature 453, 1008–1015 (2008).

Monroe, C. & Kim, J. Scaling the ion trap quantum processor. Science 339, 1164–1169 (2013).

Blatt, R. & Roos, C. F. Quantum simulations with trapped ions. Nat. Phys. 8, 277–284 (2012).

Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Quantum computations with cold trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4091 (1995).

Smith, M., Leu, A., Miyanishi, K., Gely, M. & Lucas, D. Single-qubit gates with errors at the 10-7 level. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 230601 (2025).

Löschnauer, C. et al. Scalable, high-fidelity all-electronic control of trapped-ion qubits. PRX Quantum 6, 040313 (2025).

Kim, J. & Kim, C. Integrated optical approach to trapped ion quantum computation. Quantum Inf. Comput. 9, 181–202 (2009).

Harty, T. et al. High-fidelity preparation, gates, memory, and readout of a trapped-ion quantum bit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 220501 (2014).

Duan, L.-M. & Monroe, C. Colloquium: quantum networks with trapped ions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1209–1224 (2010).

Lekitsch, B. et al. Blueprint for a microwave trapped ion quantum computer. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601540 (2017).

Miller, D. A. Device requirements for optical interconnects to silicon chips. Proc. IEEE 97, 1166–1185 (2009).

Sun, C. et al. Single-chip microprocessor that communicates directly using light. Nature 528, 534–538 (2015).

Shi, Y. et al. Silicon photonics for high-capacity data communications. Photonics Res. 10, A106–A134 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Experimental demonstration of an apodized-imaging chip-fiber grating coupler for Si3N4 waveguides. Opt. Lett. 42, 3566–3569 (2017).

Shirao, M., Klawson, D., Mouradian, S. & Wu, M. C. High efficiency focusing double-etched sin grating coupler for trapped ion qubit manipulation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 61, SK1002 (2022).

Mehta, K. K. & Ram, R. J. Precise and diffraction-limited waveguide-to-free-space focusing gratings. Sci. Rep. 7, 2019 (2017).

Xing, Z. & Mehta, K. K. Trapped-ion laser cooling in structured light fields. Phys. Rev. Appl. 24, 014034 (2025).

Cheng, L., Mao, S., Li, Z., Han, Y. & Fu, H. Grating couplers on silicon photonics: design principles, emerging trends and practical issues. Micromachines 11, 666 (2020).

Chen, X., Li, C., Fung, C. K., Lo, S. M. & Tsang, H. K. Apodized waveguide grating couplers for efficient coupling to optical fibers. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 22, 1156–1158 (2010).

Chen, Y., Halir, R., Molina-Fernández, Í., Cheben, P. & He, J.-J. High-efficiency apodized-imaging chip-fiber grating coupler for silicon nitride waveguides. Opt. Lett. 41, 5059–5062 (2016).

Andkjær, J., Nishiwaki, S., Nomura, T. & Sigmund, O. Topology optimization of grating couplers for the efficient excitation of surface plasmons. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 27, 1828–1832 (2010).

Covey, J. & Chen, R. T. Efficient surface normal multi-stage grating couplers in silicon based waveguides. In 2013 Optical Interconnects Conference, Santa Fe, NM, USA 130–131 (2013).

Zaoui, W. S. et al. Bridging the gap between optical fibers and silicon photonic integrated circuits. Opt. Express 22, 1277–1286 (2014).

Zhong, Q. et al. Focusing-curved subwavelength grating couplers for ultra-broadband silicon photonics optical interfaces. Opt. Express 22, 18224–18231 (2014).

Wohlfeil, B., Zimmermann, L. & Petermann, K. Optimization of fiber grating couplers on SOI using advanced search algorithms. Opt. Lett. 39, 3201–3203 (2014).

Shi, R. et al. High-efficiency grating couplers near 1310 nm fabricated by 248-nm DUV lithography. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 26, 1569–1572 (2014).

Lalau-Keraly, C. M., Bhargava, S., Miller, O. D. & Yablonovitch, E. Adjoint shape optimization applied to electromagnetic design. Opt. Express 21, 21693–21701 (2013).

Lin, Z., Pick, A., Lončar, M. & Rodriguez, A. W. Enhanced spontaneous emission at third-order Dirac exceptional points in inverse-designed photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 107402 (2016).

Su, L., Piggott, A. Y., Sapra, N. V., Petykiewicz, J. & Vuckovic, J. Inverse design and demonstration of a compact on-chip narrowband three-channel wavelength demultiplexer. ACS Photonics 5, 301–305 (2018).

Sun, P., Van Vaerenbergh, T., Hooten, S. & Beausoleil, R. Adjoint optimization of polarization-splitting grating couplers. Opt. Express 31, 4884–4898 (2023).

Mojaver, K. R., Safaee, S. M. R., Morrison, S. S. & Liboiron-Ladouceur, O. Recent advancements in mode division multiplexing for communication and computation in silicon photonics. J. Lightwave Technol. 42, 7860–7870 (2024).

Jiang, W., Miao, J. & Li, T. Compact silicon 10-mode multi/demultiplexer for hybrid mode-and polarisation-division multiplexing system. Sci. Rep. 9, 13223 (2019).

Li, C., Liu, D. & Dai, D. Multimode silicon photonics. Nanophotonics 8, 227–247 (2019).

Blatt, R., Häffner, H., Roos, C. F., Becher, C. & Schmidt-Kaler, F. Ion trap quantum computing with Ca+ ions. Quantum Inf. Process. 3, 61–73 (2004).

Pogorelov, I. et al. Compact ion-trap quantum computing demonstrator. PRX Quantum 2, 020343 (2021).

Ringbauer, M. et al. A universal qudit quantum processor with trapped ions. Nat. Phys. 18, 1053–1057 (2022).

Pradip, R. et al. Fast thermo-optic switching on silicon nitride platform through parity-time symmetry breaking. Opt. Express 33, 36100–36109 (2025).

Chung, S., Nakai, M. & Hashemi, H. Low-power thermo-optic silicon modulator for large-scale photonic integrated systems. Opt. Express 27, 13430–13459 (2019).

Yong, Z. et al. Power-efficient silicon nitride thermo-optic phase shifters for visible light. Opt. Express 30, 7225–7237 (2022).

Fraser, W. et al. High-efficiency metamaterial-engineered grating couplers for silicon nitride photonics. Nanomaterials 14, 581 (2024).

VitalilE, V., Lacava, C., Bucio, T. D., Gardes, F. Y. & Petropoulos, P. Highly efficient dual-level grating couplers for silicon nitride photonics. Sci. Rep. 12, 15436 (2022).

Lomonte, E., Stappers, M., Krämer, L., Pernice, W. H. & Lenzini, F. Scalable and efficient grating couplers on low-index photonic platforms enabled by cryogenic deep silicon etching. Sci. Rep. 14, 4256 (2024).

Figgatt, C. et al. Parallel entangling operations on a universal ion-trap quantum computer. Nature 572, 368–372 (2019).

Kosen, S. et al. Signal crosstalk in a flip-chip quantum processor. PRX Quantum 5, 030350 (2024).

Flannery, J. et al. Physical coherent cancellation of optical addressing crosstalk in a trapped-ion experiment. Quantum Sci. Technol. 10, 015012 (2024).

Sotirova, A. S. et al. Low cross-talk optical addressing of trapped-ion qubits using a novel integrated photonic chip. Light. Sci. Appl. 13, 199 (2024).

Brown, K. R., Harrow, A. W. & Chuang, I. L. Arbitrarily accurate composite pulse sequences. Phys. Rev. A 70, 052318 (2004).

Fang, C., Wang, Y., Huang, S., Brown, K. R. & Kim, J. Crosstalk suppression in individually addressed two-qubit gates in a trapped-ion quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 240504 (2022).

Paul, W. Electromagnetic traps for charged and neutral particles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 531 (1990).

Revelle, M. C. Phoenix and peregrine ion traps. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/abs/2009.02398 (2020).

Noel, C. et al. Electric-field noise from thermally activated fluctuators in a surface ion trap. Phys. Rev. A 99, 063427 (2019).

Niffenegger, R. J. et al. Integrated multi-wavelength control of an ion qubit. Nature 586, 538–542 (2020).

Motlakunta, S. et al. Preserving a qubit during state-destroying operations on an adjacent qubit at a few micrometers distance. Nat. Commun. 15, 6575 (2024).

Pino, J. M. et al. Demonstration of the trapped-ion quantum CCD computer architecture. Nature 592, 209–213 (2021).

Noel, C. et al. Measurement-induced quantum phases realized in a trapped-ion quantum computer. Nat. Phys. 18, 760–764 (2022).

Czischek, S., Torlai, G., Ray, S., Islam, R. & Melko, R. G. Simulating a measurement-induced phase transition for trapped-ion circuits. Phys. Rev. A 104, 062405 (2021).

Lavasani, A., Alavirad, Y. & Barkeshli, M. Measurement-induced topological entanglement transitions in symmetric random quantum circuits. Nat. Phys. 17, 342–347 (2021).

Ryan-Anderson, C. et al. Realization of real-time fault-tolerant quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041058 (2021).

Monroe, C. et al. Programmable quantum simulations of spin systems with trapped ions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025001 (2021).

Debnath, S. et al. Demonstration of a small programmable quantum computer with atomic qubits. Nature 536, 63–66 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. High-fidelity two-qubit gates using a microelectromechanical-system-based beam steering system for individual qubit addressing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 150505 (2020).

Sun, K. et al. Quantum simulation of spin-boson models with structured bath. Nat. Commun. 16, 4042 (2025).

Wineland, D. J. et al. Experimental issues in coherent quantum-state manipulation of trapped atomic ions. J. Res. Natl Inst. Stand. Technol. 103, 259 (1998).

Kang, M. et al. Seeking a quantum advantage with trapped-ion quantum simulations of condensed-phase chemical dynamics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 8, 340–358 (2024).

Katz, O. & Monroe, C. Programmable quantum simulations of bosonic systems with trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 033604 (2023).

West, A. D., Putnam, R., Campbell, W. C. & Hamilton, P. Tunable transverse spin–motion coupling for quantum information processing. Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 024003 (2021).

Mai, X., Zhang, L., Yu, Q., Zhang, J. & Lu, Y. Scalable entangling gates on ion qubits via structured light addressing. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/abs/2506.19535 (2025).

Beck, G. J., Home, J. P. & Mehta, K. K. Grating design methodology for tailored free-space beam-forming. J. Lightwave Technol. 42, 4939–4951 (2024).

Tricot, F., Phung, D., Lours, M., Guérandel, S. & De Clercq, E. Power stabilization of a diode laser with an acousto-optic modulator. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 89, 113112 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Reduction of laser intensity noise over 1 MHz band for single atom trapping. Opt. Express 28, 31209–31215 (2020).

Moro, S., Peric, A., Alic, N., Stossel, B. & Radic, S. Phase noise in fiber-optic parametric amplifiers and converters and its impact on sensing and communication systems. Opt. Express 18, 21449–21460 (2010).

Zhao, P. et al. Thermal analysis of acousto-optic modulators and its influence on ultra-stable lasers. Photonics 11, 1077 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the technical assistance of J. Bocanegra and M. McMorris, and stimulating discussions with A. Jayich, M. Radulaski, and R. Kwapisz. This project was supported by the UC Noyce Initiative 2024 Quantum Information Science program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.S., M.M., and H.H. conceived the idea. M.M. wrote the inverse-design algorithm for optimization, designed the photonic circuit, and performed the simulations. M.M. wrote the initial versions of the main and supplementary texts and prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, and supplementary figures. K.S. designed the ion trap layout and performed the potential simulation. H.H., K.S., Q.W., B.Y., and Y.T. contributed to the writing and preparation of Fig. 5. M.R.S. and H.H. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Momenzadeh, M., Sun, K., Wu, Q. et al. Individual trapped-ion addressing with adjoint-optimized multimode photonic circuits. npj Nanophoton. 3, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00102-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00102-4