ABSTRACT

Chronic sleep insufficiency is prevalent in modern society and has been associated with age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Sleep loss accelerates neurodegeneration in animal models. Here, we study whether chronic sleep curtailment leads to brain aging in wild-type mice without a genetic predisposition. We simulated modern-day conditions of restricted sleep and compared the brain (cortex) proteome of young sleep-restricted animals with different aged control groups. We report the alteration of 145 proteins related to sleep and 1275 related to age, with 71 proteins common between them. Through pathway analysis of proteins common to sleep restriction and aging, we discovered that the complement and coagulation cascade pathways were enriched by alterations of complement component 3 (C3), fibrinogen alpha and beta chain (FGA and FGB). This is the first study indicating the possible role of the complement and coagulation pathways in brain aging by chronic sleep restriction (CSR) in mice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The quality and average duration of sleep have decreased in modern society. Insufficient sleep is associated with long-term health consequences that include physiological and cognitive ailments, and this may lead to a shorter life expectancy1. Sleep disruption exacerbates age-related neurodegenerative pathologies such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease2, and evidence emerging from epidemiological studies highlights that sleep disturbance is often present years before the symptomatic stage of neurodegenerative disease and worsens during its progression3,4. Interestingly, Harrison and Rothwell showed that sleep-deprived young adults exhibit similar prefrontal neuropsychological dysfunction as alert people aged ~60 years5. Together, these important pieces of evidence point to the hypothesis that sleep loss accelerates aging or aging-like phenotypes. This hypothesis is supported by findings suggesting that sleep facilitates metabolite clearance, whereas aging reduces waste clearance within the brain6,7.

A general decline in sleep efficiency and cognitive function is a hallmark of physiological aging8. It is well established that age-associated changes are caused mainly by the loss of neuronal cells, reduced neuronal networks, and shortening of dendrites9,10,11. Proteomic analyzes of aging brain tissue from both humans and mice reveal coordinated molecular changes across key cellular pathways. These alterations manifest in proteins governing mitochondrial function, synaptic transmission, neuroinflammation, DNA repair, myelination, and apoptosis— creating a distinct molecular signature of neural aging12,13. Chronic sleep restriction (CSR) has emerged as a critical factor in cognitive decline, particularly through its detrimental effects on memory function. Prior work revealed that CSR triggers brain inflammation and synapse deterioration14,15—neurological disruptions that strikingly parallel the hallmarks of aging. This connection between sleep insufficiency and brain aging has gained further support from recent neuroimaging evidence, which demonstrates that inadequate sleep accelerates age-related changes in brain structure and function16. Despite these compelling observations linking sleep deprivation to accelerated brain aging, the underlying molecular mechanisms driving this relationship remain largely unexplored.

To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the emerging link between sleep deprivation and accelerated brain aging, we conducted a comprehensive proteomic analysis comparing CSR and age-related changes in the mouse brain. Our study examined the cerebral cortex proteome of young mice subjected to sleep restriction, middle-aged (MID) mice with normal sleep patterns, and aged mice with normal sleep patterns. Through comparative analysis of differentially abundant proteins, we uncovered distinct molecular signatures. CSR predominantly altered the expression of proteins involved in cytoplasmic translation, vesicle-mediated transport, and nitric oxide-mediated signal transduction. In contrast, aging specifically affected proteins associated with neuronal projections, regulation of synapse structure or activity, mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation, amino acid metabolic processes, and neutrophil degranulation. Remarkably, our pathway analyzes revealed that both CSR and aging converged on common molecular pathways—the complement and coagulation cascades. This novel finding represents the first proteomic evidence highlighting the significance of these pathways in both CSR and aging-related brain changes. These shared molecular signatures provide a promising foundation for understanding how chronic sleep debt may accelerate brain aging, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Results

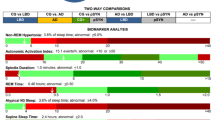

Experimental design and proteome coverage

We investigated proteome changes using young C57BL/6J mice (3–4 months old) subjected to different sleep protocols, alongside age-related controls. Our sleep restriction paradigm consisted of five experimental groups: sleep-deprived young mice (SD) underwent forced locomotion for 20 h (ZT4-ZT24) with 4 h of sleep permitted for 5 days; recovery sleep mice (RS) were similarly sleep-deprived allowed them to recover for the 6th and 7th day, and on the 8th day they experienced 10 h of forced locomotion during their active period (ZT14-24) with 14 h of sleep allowed; like normal sleep controls (NS). We also included two age-related control groups: MID and old-aged (OLD) mice with normal sleep patterns (Fig. 1A).

A Animals from SD group were subjected to sleep restriction for 20 h (ZT4-ZT24) by FA for 5 d (Day 1–Day 5) (middle), same age NS, MID, and OLD age control groups (left) were subjected to FA for 10 h (ZT14-ZT24) at double speed and RS group was subjected to sleep restriction like SD group and allowed to recover for two days (Day 6–Day 7) and on Day 8 subjected to FA like controls (right). White and black bars represent light and dark periods and orange lines represent FA timelines. Arrow at ZT4 indicates termination of experiment followed by sacrifice and isolation of cerebral cortex. B Workflow for 16plex-TMT quantitative proteomics from cortex, from microdissection to bioinformatics analysis. Black color mice, sizes small to large: NS, MID, and OLD. Orange and light orange color: SD and RS group. C Overview of proteome coverage obtained in TMT-based quantitative analysis. D PCA plot showing segregations of all five groups, color-coded. NS normal sleep, SD sleep deprived, RS recovery sleep, MID mid-age, OLD old age, FA forced ambulation.

To analyze proteomic changes, we harvested the cerebral cortex at ZT4, 4 h after the final treatment period. We employed quantitative proteomics using 16-plex tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling coupled with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (Fig. 1B). This approach allowed simultaneous analysis of all experimental groups within a single mass spectrometry run, eliminating inter-run variability. With this approach, we identified 72,356 peptide spectrum matches (PSMs) and 47,151 unique peptides, corresponding to 5774 distinct proteins (Fig. 1C). We further filtered the total number of proteins by excluding entries with zeros in all reporter-ion intensities in an experimental group. This approach was adopted to enable cross-group comparisons between any of the groups since a protein has to be quantified in all groups for such comparisons. This filtering eventually resulted in 5723 proteins that were used for subsequent analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed clear segregation among all five experimental groups (NS, SD, RS, MID, and OLD), indicating distinct proteomic signatures for each condition (Fig. 1D).

CSR contributes to proteomic alteration in the cortex of young mice

We investigated how CSR shapes protein dynamics in the cerebral cortex by examining protein expression in the young mice group, which were exposed to varying sleep conditions (Fig. 2A–C). We reported sleep-related alteration by comparing proteomic abundance across NS, SD and RS. Our proteomic analysis revealed that CSR significantly modifies 145 unique proteins (78 upregulated and 67 downregulated) (2.5% of 5723 proteins; q < 0.2) (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, we found that CSR exerts more subtle effects on cortical protein expression than acute sleep deprivation, aligning with previous findings on sleep-dependent gene regulation17,18,19.

Volcano plots showing changes in global proteomes of SD/NS (A), SD/RS (B), and (C) RS/NS comparisons. Unpaired t-tests followed by false discovery rate (FDR) analysis were used to compare groups. Significantly upregulated and downregulated protein expression is color coded with red and blue, respectively (adjusted p-value < 0.2). Proteins in grey are not significantly changed after sleep deprivation. Bar plots showing significantly enriched top upregulated (D, E) and downregulated (F, G) GOBP and RGS, respectively. GOBP gene ontology biological process, RGS reactome gene sets. NS normal sleep, SD sleep deprived, RS recovery sleep, IGF insulin-like growth factor, IGFBPs insulin-like growth factor binding proteins.

To decipher the functional implications of these protein alterations, we conducted gene ontology (GO) analyzes of biological processes (GOBP) and reactome gene sets (RGS) from the upregulated and downregulated proteins. These analyzes uncovered that CSR enhances key cellular pathways, including nitric oxide-mediated signaling, vesicle-mediated transport, platelet activation, signaling, and aggregation, and MAPK and ERK cascades (Fig. 2D, E), whereas it reduces cytoplasmic translation, regulation of axonogenesis, cellular component size, and rRNA processing in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 2F, G). These findings reveal how sleep restriction orchestrates precise molecular changes in cortical function, suggesting a complex interplay between sleep patterns and protein regulation in the brain.

Aging changes the abundance of cortical proteomes

Next, we explored the molecular and cellular cascades that drive brain aging by conducting comparative proteomic analyzes across young (NS), MID, and old (OLD) mice (Fig. 3A–C). Our investigation revealed striking alterations in 1275 unique proteins throughout the aging trajectory (22.2% of 5723 proteins; q < 0.2) (Supplementary Table 1). We found that by mid-age (12–14 months), 572 proteins (383 upregulated and 189 downregulated) showed significant changes (~10% of 5723; q < 0.2), while this number dramatically increased to 1,138 proteins (~20% of 5737; q < 0.2) by 24 months (Fig. 3A, B). We reported it as age-related alterations. We also compared our mid-age data with a similar previously published study12 and identified 20 overlapping proteins, primarily associated with synaptic and mitochondrial functions (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Volcano plots showing changes in global proteomes of OLD/NS (A), MID/NS (B), and (C) RS/NS comparisons. Unpaired t-tests followed by false discovery rate (FDR) analysis were used to compare groups. Significantly upregulated and downregulated protein expression is color coded with red and blue, respectively (adjusted p-value < 0.2). Proteins in grey are not significantly changed after sleep deprivation. Bar plots showing significantly enriched top upregulated (D, E) and downregulated (F, G) GOBP and RGS, respectively. GOBP gene ontology biological process, RGS reactome gene sets. NS normal sleep, MID mid-age, OLD old age.

To determine the functional significance of these age-dependent protein modifications, we again performed GO and RGS analyzes on the upregulated and downregulated proteins. GOBP analysis unveiled significant age-related upregulation in critical neural processes, including the amino acid metabolic processes, fatty acid beta-oxidation, and actin filament organization, and downregulation of neuron projection development, cytoplasmic translation, and regulation of synapse structure or activity (Fig. 3D, F). RGS demonstrated enhanced enrichment in proteins regulating hemostasis and neutrophil degranulation. In contrast, we found reduced signaling of proteins governing translation and rRNA processing in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 3E, G). Together, these results illuminate the molecular landscape of brain aging, revealing systematic alterations in protein networks that orchestrate neural function and plasticity across the lifespan.

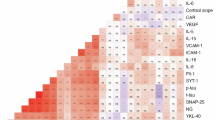

Common proteomic signatures between CSR and aging

To explore potential mechanistic links between CSR and aging, we investigated overlapping proteomic signatures across these conditions. Through comparative analysis, we identified 71 proteins exhibiting concordant alterations in both sleep-restricted and aging brains (p < 0.0001). Out of 71, 55 proteins were upregulated and 16 downregulated (Fig. 4A, E). We then employed a multi-layered analytical approach—combining gene ontology (GO), pathway analysis, and molecular complex detection (MCODE)—to decode the functional implications of these shared protein modifications.

Venn diagrams represent the overlaps between sleep restriction and age-related upregulated (A) and downregulated (E) alterations. Bar plots showing significantly enriched top functional annotations of upregulated (B–D) and downregulated (F–H) overlapped proteins: (B, F) biological processes, (C, G) reactome, and (D, H) KEEG pathways. MCODE components (enrichment P-value < 0.001) from upregulated (I) and downregulated (J) overlapped proteins. GOBP gene ontology biological process, RGS reactome gene sets, MCODE molecular complex detection.

GO analysis with upregulated proteins revealed fascinating enrichment patterns in heterotypic cell-cell adhesion regulation, vesicle-mediated transport, and humoral immune response (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, cytoplasmic translation, regulation of axonogenesis and cellular component size were enriched with downregulated proteins (Fig. 4F). Reactome analysis further illuminated enhanced enrichment in platelet degranulation, response to elevated platelet cytosolic Ca+2, and MAPK family signaling cascade, and reduced signaling of SRP-dependent co-translational protein targeting to the membrane, formation of a pool of free 40S subunit, and GTP hydrolysis and joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit (Fig. 4C, G).

Intriguingly, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis20 on the upregulated proteins revealed significant enrichment in systems linked to platelet activation, coronavirus disease (COVID-19), complement and coagulation cascades, and neutrophil extracellular trap formation (Fig. 4D). These findings suggest that both sleep restriction and aging may enhance vulnerability to COVID-19 infection while perturbing complement and coagulation cascades—a mechanism recently implicated in α-synuclein-mediated neurodegeneration and neuronal loss21. The ribosome and coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pathways were also affected by sleep loss and aging (Figure H).

We further dissected the complement and coagulation cascade pathways, mapping proteins modified by both CSR and aging (Fig. 5). This revealed alterations in key components, including complement component 3 (C3), and fibrinogen alpha and beta chains (FGA and FGB). Through protein-protein interaction MCODE analysis, we discovered significant involvement of metabolism of RNA and SRP-dependent co-translational protein targeting to membrane in both CSR and aging (enrichment p-value < 0.001) (Fig. 4E), suggesting shared molecular mechanisms underlying these conditions.

To enhance the clarity and interpretability of our mass spectrometry data, we also prepared representative box plots displaying the quantified values from the 15 samples from the proteins list (5 groups, N = 3), showing variability across replicates (Supplementary Fig. 2, and Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics technologies have been widely used to unravel the molecular correlates of certain behaviors and disease conditions22,23,24,25. Using this powerful technology, we uncovered crucial molecular links between chronic sleep loss and accelerated brain aging. Our comprehensive analysis identified a significant overlap between proteins altered by CSR and aging in the mouse cerebral cortex. The most striking discovery was the shared activation of complement and coagulation cascades in both conditions, suggesting a common molecular pathway through which sleep loss might accelerate brain aging.

In recent years, attempts have been made to elucidate the proteome of sleep-deprived brains, but these studies were mainly aimed at studying the effect of acute sleep deprivation18,23,26,27,28. In this study, we attempted to mimic real-world conditions of restricted sleep by allowing the mice to sleep only 4 h for 5 consecutive days and mapped the proteomics alterations in the cerebral cortex. Our differential protein abundance analysis shows that chronic sleep treatments alter only 2.5% of identified proteins. Of note, we recently reported a shift of 22% in neuronal proteome under acute sleep restrictions, although the changes in protein expression in astrocytes were limited to 3%18. These results reveal the variable response of acute and chronic sleep deprivation on protein expression in the brain. Interestingly, this trend is consistent at the level of mRNA expression17,19,29,30. We and others have reported that synapse organization and activity, macromolecule biosynthesis, and energy homeostasis are the prime functional implications of acute sleep disruptions17,18,28,31. On the other hand, sustained sleep loss triggers inflammation and cellular stress17. Here, we showed that chronic sleep treatments alter cytoplasmic translation, response to nitric oxide-mediated signaling, MAPK/ERK cascades, platelet activation, and RNA metabolism. These molecular signatures suggest that CSR particularly impacts non-neuronal cells like astrocytes and microglia, which traditionally serve as support cells in the brain. This finding challenges our traditional neuron-centric view of sleep’s effects on the brain.

Aging is a complex biological process. The speed and trajectory of aging vary from person to person. We furthered our investigation to understand the multifactorial process of brain aging by comparing the proteomics landscape of the cerebral cortex of young, MID, and old-age mice. Age-related proteomic changes were extensive, affecting 20% of identified proteins. These alterations occurred in pathways governing cytoplasmic translation, neuron projection development, synapse structure and activity, vesicular transport, and mitochondrial function. Such widespread changes reflect the complex nature of brain aging, where multiple cellular processes gradually decline over time. We also compared our results with a previously published dataset and identified common alterations in pathways related to synaptic and mitochondrial function, highlighting these as shared features of brain aging12. Our findings align with previous studies on the molecular mechanisms of brain aging12,32,33, confirming that aging affects fundamental cellular processes throughout the brain.

The complement cascade emerged as a key mediator linking sleep loss to accelerated aging. This pathway, part of the innate immune system, normally protects the brain from injury and infection. Both CSR and aging increased the expression of complement component C3, the central molecule in complement activation. C3 drives synapse elimination in the aging central nervous system34, essentially pruning neural connections. Its increased expression appears in age-related disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease21, suggesting it may contribute to cognitive decline.

Coagulation pathway activation provides another mechanistic link between CSR and aging. We saw the altered expression of fibrinogen chains (FGA, FGB) and proteins associated with platelet activation in both conditions. These proteins normally regulate blood clotting, but in the brain, they can have detrimental effects. Their increased presence contributes to blood-brain barrier disruption and neuroinflammation in aging brains35. Platelet activation could be the pathophysiological mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease36, marking it as a potential early indicator of brain aging.

The complement and coagulation systems typically maintain brain homeostasis through protective functions, acting to maintain and defend the brain. However, chronic activation of these pathways can trigger neuroinflammation and disrupt synaptic transmission37, much like an overactive immune response causing collateral damage. Our findings suggest that CSR could potentially accelerate brain aging by chronically activating these cascades, essentially wearing down the brain’s protective systems through overuse. This newfound mechanism offers potential therapeutic targets for mitigating the effects of sleep loss and slowing brain aging.

While our study provides novel insight into the molecular programs through which CSR may accelerate brain aging, the use of only male animals represents a limitation that may affect the generalizability of our findings. Including female mice in future studies will be important to uncover potential sex-specific responses to CSR and aging in the brain proteome.

Overall, our study reveals how chronic sleep loss may prematurely age the brain through specific molecular pathways shared between sleep deprivation and aging. Understanding these mechanisms opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention, potentially allowing us to protect the brain from the harmful effects of insufficient sleep. Future research should focus on developing targeted treatments that modulate complement and coagulation cascades to promote healthy brain aging, even in the face of sleep challenges common to modern life.

Methods

Animals

All animal studies were carried out in concordance with an approved protocol from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Wild-type, male C57BL/6J mice (RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and acclimatized in the animal unit for at least 2 weeks before experiments. Mice were selected such that they were aged between 3 and 4 months (NS, SD, and RS), 12 and 14 months (MID), and 24 months (OLD) at the time of experiments. Before the CSR protocol began, mice were housed for a week in the sleep cage (Campden/Lafayette Instruments Model 80391) for habituation with ad libitum access to food and water under standard humidity and temperature (21 ± 10 °C) on a 12-h light: 12-h dark cycle.

Sleep deprivation procedures

Sleep deprivation procedures were adapted from the previously described study38. Briefly, sleep deprivation was produced by applying tactile stimulus with a horizontal bar sweeping just above the cage floor (bedding) from one side to the other side of the cage. A 5-day procedure of sleep deprivation was performed from ZT4 to ZT24 (20 h) with 4 h of opportunity to sleep and different aged controls were subjected to the same tactile stimulus with a horizontal bar sweeping, but twice the speed of the sleep-deprived (SD) group in their active period from ZT14 to ZT24 (10 h). This ensured that total activity per day was the same across all studied groups. The recovery (RS) group was allowed to recover following SD for 2 days. Mice had ad libitum access to food and water throughout the experiment. Different-aged controls and SD groups were sacrificed on the 6th day and the RS group on the 9th day at ZT4 (Fig. 1A). The RS group is intended to provide insight into the potential reversibility or persistence of proteomic changes following CSR. We used three replicates per group, i.e., NS (n = 3) and SD (n = 3), RS (n = 3), MID (n = 3), OLD (n = 3). Following sacrifice by cervical dislocation, whole brains were isolated, cortices quickly dissected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

TMT-based quantitative proteomics

The mouse cerebral cortex samples were homogenized in 300 μL lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 0.5% NP-40, protease, and phosphatase inhibitors) using a pellet pestle (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 min on ice. Then, mild sonication was applied for 15 min (30 s on, 30 s off; medium power) using a Bioruptor Standard (Diagenode) instrument and lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were carefully separated and transferred into new microcentrifuge tubes. Protein precipitation was performed with 1:6 volume of pre-chilled (−20 °C) acetone overnight at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation of lysates at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were discarded without disturbing pellets, and pellets were air-dried for 2–3 min to remove residual acetone. Pellets were dissolved in 300 µL 100 mM TEAB buffer. Sample processing for TMT-based quantitative proteomics was performed following the same protocol as described previously18. Briefly, each sample’s protein concentration was determined using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23225). 100 µg protein per condition was transferred into new microcentrifuge tubes, and 5 µL of the 200 mM TCEP was added to reduce the cysteine residues and the samples were then incubated at 55 °C for 1-h. Subsequently, the reduced proteins were alkylated with 375 mM iodoacetamide (freshly prepared in 100 mM TEAB) for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Then, trypsin (Trypsin Gold, Mass Spectrometry Grade; Promega, V5280) was added at a 1:40 (trypsin: protein) ratio and samples were incubated at 37 °C for 12-h for proteolytic digestion. After in-solution digestion, peptide samples were labeled with 16-plex TMT Isobaric Label Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A44521) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The reactions were quenched using 5 µL of 5% hydroxylamine for 30 min. Protein from all five experimental conditions, i.e., NS, SD, RS, MID, and OLD (n = 3 biological replicates for each), were labeled with the 15 of the TMT labels within the 16-plex reagent set, while the final mass tag was used for labeling an internal pool containing an equal amount of proteins from each sample. The application of multiplexed TMT reagents allowed the comparison of NS, SD, RS, MID, and OLD samples within the same MS run, eliminating the possibility of run-to-run (or batch) variations.

TMT-labeled samples were resuspended in 5% formic acid and then desalted using a SepPak cartridge according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA). Eluate from the SepPak cartridge was evaporated to dryness and resuspended in buffer A (20 mM ammonium hydroxide, pH 10) prior to fractionation by high pH reverse-phase (RP) chromatography using an Ultimate 3000 liquid chromatography system (Thermo Scientific). In brief, the sample was loaded onto an XBridge BEH C18 Column (130 Å, 3.5 µm, 2.1 mm × 150 mm, Waters, UK) in buffer A and peptides eluted with an increasing gradient of buffer B (20 mM Ammonium Hydroxide in acetonitrile, pH 10) from 0 to 95% over 60 min. The resulting fractions (20 fractions per sample) were evaporated to dryness and resuspended in 1% formic acid prior to analysis by nano-LC MSMS using an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific).

Nano-LC mass spectrometry

High pH RP fractions were further fractionated using an Ultimate 3000 nano-LC system in line with an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). In brief, peptides in 1% (vol/vol) formic acid were injected into an Acclaim PepMap C18 nano-trap column (Thermo Scientific). After washing with 0.5% (vol/vol) acetonitrile 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid peptides were resolved on a 250 mm × 75 μm Acclaim PepMap C18 reverse phase analytical column (Thermo Scientific) over a 150 min organic gradient, using 7 gradient segments (1–6% solvent B over 1 min, 6–15% B over 58 min, 15–32% B over 58 min, 32–40% B over 5 min, 40–90% B over 1 min, held at 90% B for 6 min and then reduced to 1% B over 1 min) with a flow rate of 300nL min−1. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid, and Solvent B was aqueous 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid. Peptides were ionized by nano-electrospray ionization at 2.0 kV using a stainless-steel emitter with an internal diameter of 30 μm (Thermo Scientific) and a capillary temperature of 275 °C. All spectra were acquired using an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer controlled by Xcalibur 4.1 software (Thermo Scientific) and operated in data-dependent acquisition mode using an SPS-MS3 workflow. FTMS1 spectra were collected at a resolution of 120,000, with an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 200,000 and a max injection time of 50 ms. Precursors were filtered with an intensity threshold of 5000, according to charge state (to include charge states 2–7) and with monoisotopic peak determination set to Peptide. Previously interrogated precursors were excluded using a dynamic window (60 s ±10ppm). For FTMS3 analysis, the Orbitrap was operated at 50,000 resolutions with an AGC target of 50,000 and a max injection time of 105 ms. Precursors were fragmented by high-energy collision dissociation at a normalized collision energy of 60% to ensure maximal TMT reporter ion yield. Synchronous Precursor Selection (SPS) was enabled to include up to 5 MS2 fragment ions in the FTMS3 scan.

Database search and statistical analysis of quantitative proteomics data

Quantitative proteomics raw data files were analyzed using the MaxQuant (version 2.1.3.0)39. MS2/MS3 spectra were searched against UniProt database specifying Mus musculus (Mouse) taxonomy (Proteome ID: UP000000589; Organism ID: 10090). All searches were performed using “Reporter ion MS3” with “16-plex TMT” as isobaric labels with a static modification for cysteine alkylation (carbamidomethylation), and oxidation of methionine (M) and protein N-terminal acetylation as the variable modifications. Trypsin digestion with a maximum of two missed cleavages, minimum peptide length of seven amino acids, precursor ion mass tolerance of 5 ppm, and fragment mass tolerance of 0.02 Da were specified in all analyzes. The false discovery rate (FDR) was specified at 0.01 for PSMs, protein, and site decoy fraction. TMT signals were corrected for isotope impurities based on the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequent processing and statistical analysis of quantitative proteomics datasets were performed using Perseus (version 2.0.6.0)40 and DEseq241. During data processing, reverse and contaminant database hits and candidates identified only by site were filtered out. Finally, unpaired t-tests followed by multiple-testing adjustment (Benjamini–Hochberg method) were performed to compare sleep and aged control groups.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis

Significantly and differentially abundant proteins across sleep treatments (NS vs. SD, SD vs. RS, NS vs. RS) and different age groups (NS vs. OLD, NS vs. MID, MID vs. OLD) were subjected to GO analysis42. Significantly enriched GO terms (p < 0.01) were visualized as bar plots for GOBP and RGS. Protein-protein interactions network analysis was performed with MCODE. We visualized the enriched KEGG pathway20 by using clusterProfiler and pathview43,44.

Statistical methods

All experimental subjects are biological replicates. R or GraphPad Prism 8 software was used to perform statistical tests and plots. Unpaired t-tests were performed to compare sleep treatments and aged control groups. For this analysis, we used multiple-testing adjusted (Benjamini–Hochberg) q-values < 0.2, unless indicated otherwise. Detailed sample sizes, statistical tests, and results are reported in the figure legends.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data described in this article are deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD060735.

References

Mahowald, M. W. Review sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem by the Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. Engl. J. Med. 356, 199–200 (2007).

Shi, L. et al. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 40, 4–16 (2018).

Guarnieri, B. et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in mild cognitive impairment and dementing disorders: a multicenter italian clinical cross-sectional study on 431 patients. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 33, 50–58 (2012).

Irwin, M. R. & Vitiello, M. V. Implications of sleep disturbance and inflammation for Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Lancet Neurol. 18, 296–306 (2019).

Harrison, Y., Horne, J. A. & Rothwell, A. Prefrontal neuropsychological effects of sleep deprivation in young adults-a model for healthy aging? Sleep 23, 1067–73 (2000).

Mendelsohn, A. R. & Larrick, J. W. Sleep facilitates clearance of metabolites from the brain: glymphatic function in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Rejuvenation Res. 16, 518–523 (2013).

Fyfe, I. Brain waste clearance reduced by ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 16, 128–128 (2020).

Varga, A. W. et al. Effects of aging on slow-wave sleep dynamics and human spatial navigational memory consolidation. Neurobiol. Aging 42, 142–149 (2016).

Morterá, P. & Herculano-Houzel, S. Age-related neuronal loss in the rat brain starts at the end of adolescence. Front. Neuroanat. 6, 45 (2012).

Watanabe, H. et al. Characteristics of neural network changes in normal aging and early dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 747359 (2021).

Nakamura, S., Akiguchi, I., Kameyama, M. & Mizuno, N. Age-related changes of pyramidal cell basal dendrites in layers III and V of human motor cortex: a quantitative Golgi study. Acta Neuropathol. 65, 281–284 (1985).

Li, Y. et al. Proteomic profile of mouse brain aging contributions to mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA oxidative damage, loss of neurotrophic factor, and synaptic and ribosomal proteins. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 5408452 (2020).

Wingo, A. P. et al. Large-scale proteomic analysis of human brain identifies proteins associated with cognitive trajectory in advanced age. Nat. Commun. 10, 1619 (2019).

Zielinski, M. R. et al. Chronic sleep restriction elevates brain interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha and attenuates brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression. Neurosci. Lett. 580, 27–31 (2014).

Kincheski, G. C. et al. Chronic sleep restriction promotes brain inflammation and synapse loss, and potentiates memory impairment induced by amyloid-β oligomers in mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 64, 140–151 (2017).

Ramduny, J., Bastiani, M., Huedepohl, R., Sotiropoulos, S. N. & Chechlacz, M. The association between inadequate sleep and accelerated brain ageing. Neurobiol. Aging 114, 1–14 (2022).

Cirelli, C., Faraguna, U. & Tononi, G. Changes in brain gene expression after long-term sleep deprivation. J. Neurochem. 98, 1632–1645 (2006).

Jha, P. K., Valekunja, U. K., Ray, S., Nollet, M. & Reddy, A. B. Single-cell transcriptomics and cell-specific proteomics reveals molecular signatures of sleep. Commun. Biol. 5, 846 (2022).

Diessler, S. et al. A systems genetics resource and analysis of sleep regulation in the mouse. PLoS Biol. 16, e2005750 (2018).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Ma, S.-X. et al. Complement and coagulation cascades are potentially involved in dopaminergic neurodegeneration in α-synuclein-based mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. J. Proteome Res. 20, 3428–3443 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. A proteomics landscape of circadian clock in mouse liver. Nat. Commun. 9, 1553 (2018).

Gulyássy, P. et al. The effect of sleep deprivation and subsequent recovery period on the synaptic proteome of rat cerebral cortex. Mol. Neurobiol. 59, 1301–1319 (2022).

Lin, X. et al. Proteomic profiling in MPTP monkey model for early Parkinson disease biomarker discovery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1854, 779–787 (2015).

Bai, B. et al. Proteomic landscape of Alzheimer’s Disease: novel insights into pathogenesis and biomarker discovery. Mol. Neurodegener. 16, 55 (2021).

Ren, J. et al. Quantitative proteomics of sleep-deprived mouse brains reveals global changes in mitochondrial proteins. PLoS ONE 11, e0163500 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of the molecular substrates of sleep need. Nature 558, 435–439 (2018).

Noya, S. B. et al. The forebrain synaptic transcriptome is organized by clocks but its proteome is driven by sleep. Science 366, eaav2642 (2019).

Gerstner, J. R. et al. Removal of unwanted variation reveals novel patterns of gene expression linked to sleep homeostasis in murine cortex. BMC Genom. 17, 727 (2016).

Scarpa, J. R. et al. Cross-species systems analysis identifies gene networks differentially altered by sleep loss and depression. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat1294 (2018).

Mackiewicz, M. et al. Macromolecule biosynthesis: a key function of sleep. Physiol. Genom. 31, 441–457 (2007).

Duda, P., Wójcicka, O., Wiśniewski, J. R. & Rakus, D. Global quantitative TPA-based proteomics of mouse brain structures reveals significant alterations in expression of proteins involved in neuronal plasticity during aging. Aging 10, 1682–1697 (2018).

Drulis-Fajdasz, D., Gostomska-Pampuch, K., Duda, P., Wiśniewski, J. R. & Rakus, D. Quantitative proteomics reveals significant differences between mouse brain formations in expression of proteins involved in neuronal plasticity during aging. Cells 10, 2021 (2021).

Stevens, B. et al. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell 131, 1164–1178 (2007).

Senatorov, V. V. et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in aging induces hyperactivation of TGFβ signaling and chronic yet reversible neural dysfunction.Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaaw8283 (2019).

Carbone, M. G., Pagni, G., Tagliarini, C., Imbimbo, B. P. & Pomara, N. Can platelet activation result in increased plasma Aβ levels and contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease? Ageing Res. Rev. 71, 101420 (2021).

Berkowitz, S. et al. Complement and coagulation system crosstalk in synaptic and neural conduction in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Biomedicines 9, 1950 (2021).

Kim, B., Hwang, E., Strecker, R. E., Choi, J. H. & Kim, Y. Differential modulation of NREM sleep regulation and EEG topography by chronic sleep restriction in mice. Sci. Rep. 10, 18 (2020).

Cox, J. & Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 (2008).

Tyanova, S. et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 13, 731–740 (2016).

Langley, S. R. & Mayr, M. Comparative analysis of statistical methods used for detecting differential expression in label-free mass spectrometry proteomics. J. Proteom. 129, 83–92 (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 10, 1523 (2019).

Yu, G. Using meshes for MeSH term enrichment and semantic analyses. Bioinformatics 34, 3766–3767 (2018).

Luo, W. & Brouwer, C. Pathview: an R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics 29, 1830–1831 (2013).

Acknowledgements

A.B.R. acknowledges funding from the Perelman School of Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (ITMAT) at the University of Pennsylvania. This work was supported also by NIH DP1DK126167 and R01GM139211 (A.B.R.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K.J. and A.B.R. conceived and designed the experiments. P.K.J. performed mouse sleep deprivation experiments, tissue dissections, and sample processing. P.K.J. and U.K.V. analyzed proteomics data. A.B.R. supervised the entire study and secured funding. The manuscript was written by P.K.J. and A.B.R. with input from U.K.V. All authors agreed on the interpretation of data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jha, P.K., Valekunja, U.K. & Reddy, A.B. Chronic sleep restriction activates complement and coagulation cascades: a molecular link to accelerated brain aging. npj Biol Timing Sleep 3, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00066-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00066-w