Abstract

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an arrhythmic hereditary disorder affecting mainly males, aged 30–50 years. Type D personality has a prevalence of 32.7% among BrS patients and 15% of these patients have an history of psychiatric disorders. One out of six BrS patients could develop anxiety/depression after BrS diagnosis or after the implantation of a defibrillator. This review evaluates the psychological profile of BrS patients, the impact of its diagnosis, and potential tools to evaluate these features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is a hereditary disorder, with autosomal dominant transmission and incomplete penetrance, manifesting mainly in males aged 30–50 years with resting syncope, nocturnal agonal breathing, major ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death1. The diagnosis of BrS has significant implications for clinical management and genetic counseling. BrS patients often face crucial decisions, including the choice to accept drug therapies or procedural interventions, as well as genetic implications for family members2,3.

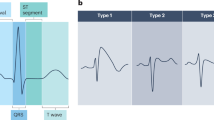

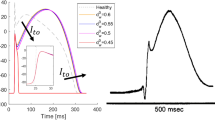

The diagnosis of BrS can be made by ECG findings of a type 1 BrS pattern and other clinical features, such as documented polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PVT)/Ventricular fibrillation (VF), arrhythmic syncope, or family history of BrS1. BrS Type 1 ECG pattern consists of a J point elevation of >2 mV with coved ST elevation and T wave inversion in at least one right precordial ECG lead, V1 or V2, located at the second, third, or fourth intercostal spaces1. This pattern may be found spontaneously or could be induced during fever or due to sodium channel blocking drugs exposure. If such a pattern is found, it is necessary to exclude other underlying conditions1.

Other BrS ECG patterns are type 2 (saddle-back pattern) and type 3 that are less well defined (right precordial ST elevation < 1 mm saddle-back, coved type, or both). These patterns are not diagnostic “per se” but in selected cases could be evaluated with sodium channel blocking drugs test.

The diagnostic-therapeutic course following a diagnosis of BrS is complex and involves taking measures such as educating the patient to avoid states of hyperpyrexia or excessive alcohol intake, as well as a list of sodium channel blocking drugs and substances to avoid4. In-depth diagnostics such as testing with sodium-channel blocking drugs may be necessary, up to the possibility of an electrophysiological study with programmed electrical stimulation or the implantation of a loop-recorder5,6.

Proband genetic diagnostic tests and screening of family members become necessary once the diagnosis of BrS is made. This is often difficult and generates concern in patients and their family. The first therapeutic approach will be guided by the presentation setting. Generally, there is an acute pharmacological treatment only in case of arrhythmic storm, that requires therapy with endo-venous Isoproterenol7.

In BrS patients at highest risk of sudden cardiac death, the long-term therapy that has shown the best efficacy is ICD implantation7.

Many variables can affect illness perceptions of patients diagnosed with inherited cardiac diseases. First, the type of disease and its implications in terms of prognosis and treatment8. Secondly, patient-related factors, including his or her psycho-aptitude profile, the family, socio-economic and cultural context, comorbidities (often involving polypharmacotherapy), and the availability of a caregiver9.

These factors may thereby influence crucial aspects of BrS management10 as well as patients’ quality of life.

Focusing on these aspects may help in a mindful framing of these patients. This may lead to a more complete follow-up, admitting the possibility of psychological evaluation and counseling from the earliest stages of diagnosis. Aim of the review is to evaluate current literature on psychological profile of BrS patients, the impact of its diagnosis and potential tools to evaluate these features.

Methods

We identified relevant English-language publications through a PubMed search using the keywords “Brugada Syndrome”, in March 2024 in different combinations with: anxiety, depression, psychological impact, psychological disorders. We completed this search by cross-referencing published articles and also performed a hand search of major journals. We have restricted the citations to the most relevant and informative publications.

One hundred and twenty studies were identified through database search and 36 duplicates were removed. Seventy-five unique records were screened and 44 of them were excluded. Thirty-one full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and four full articles were selected for this review (Table 1).

Diagnosis of Brugada syndrome and potential psychological consequences

When evaluating the quality of life of patients diagnosed with BrS, one must consider the setting where the diagnosis occurs. Sometimes, BrS diagnosis is made during genetic screening after an acute event often occurred to a first-degree relative, such as a resuscitated cardiac arrest or sudden death9. In most instances the diagnosis is incidental during a routine ECG recorded for different reasons in subjects considering themselves definitely healthy. Obviously, these settings generate acute distress10,11,12,13 whose duration and intensity are higher in patients who experienced the unexpected death of a relative14.

Mental distress, anxiety and doubts about the need for medical treatment are well known factors associated with reduced drug adherence15, as well as with higher morbidity and mortality16,17. In a single center study from Taiwan including 29 highly symptomatic BrS patients there were increased levels of anxiety and depression. As a matter of fact, there was a prevalence of 17.2% and 13.9% of anxiety or depression, respectively18. In a recent Danish study19, it was found that approximately one out of six (16%) BrS patients developed anxiety/depression after diagnosis. Moreover, when only symptomatic patients were considered at diagnosis (resuscitated arrest; occurrence of ventricular tachycardia; syncope), the incidence of new-onset depression/anxiety was higher19 (Table 1).

Which tools can be used to evaluate the level of well-being of BrS patients?

Various efforts have been made over the years to have a uniform yardstick for judging the quality of life of patients with cardiovascular diseases20, with special emphasis on the brevity of questionnaire completion and self-reported perceptions21,22,23,24.

Regarding the assessment of quality of life (QoL), the health-Related QoL questionnaire has proven to be valid and easy to administer in patients with ischemic heart disease and heart failure20. This assesses two different pathways on how the patient copes his disease, the physical one and the emotional one25.

Other questionnaires with known psychometric validity and widely used for the assessment of the QoL are the Mc-New Heart Disease Health-related Quality of Life questionnaire and the Short form Health Survey 36 (a generic health survey with 36 questions including physical component and mental component)18.

About mental and behavioral disorders screening, the GHQ-12 (General Health Questionnaire) is widely validated for the assessment of psychological disorders in primary health care23. For the assessment of possible emotional instability26,27, it may be used the Ten item personality inventory28 which assesses the five major dimensions of personality (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, openness to experiences).

For the assessment of coping styles, which impact on patients’ mental outcomes12, the Brief-cope22 may be helpful, a self-reported questionnaire to measure effective and ineffective ways of responding to a stressful life event.

For the assessment of anxiety, an important predictor of QoL18, and depression, we have the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, a questionnaire with 14 items with four response options for each.

The Oslo Social Support Scale (OSSS-3)24 considers the sense of concern perceived by others about the patient’s condition and the type and number of social relationships he or she can rely on. The list of tests evaluated among BrS patients and results comparing BrS patients and controls are provided in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Diagnosis of BrS in patients with mental diseases and use of psychiatric drugs

The impact of BrS diagnosis is heterogenous. Some patients cannot manage well the diagnosis and symptoms of a hereditary heart disease, others may manage better especially if their family members are asymptomatic and do not carry the risk gene29.

Jespersen et al. 19 found in a cohort of 263 consecutive patients with BrS diagnosed between 2006 and 2018 from a national registry in Denmark, that before BrS diagnosis about 15% of patients had an history of psychiatric disorders.

Patients with BrS and history of psychiatric disorders (40 out of 263) were taking antidepressants (42.5%), anxiolytics (27.5%), and antipsychotics (17.5%).

On the other side, 35 out of 223 patients (15%) developed anxiety or depression following BrS diagnosis. Some of these patients started therapy with antidepressants (7.2%) or anxiolytics drugs (12.1%) (Fig. 2, Table 3). In the same Danish registry, authors found that several BrS patients were treated with psychiatric drugs not recommended. This tendency was higher among patients with BrS who developed new-onset depression or anxiety (n = 18/35, 51.4%)19. This finding is line with several studies that have correlated ion channel disease with psychiatric disorders30,31.

Many psychiatric drugs are contraindicated in Brugada syndrome (tricyclic antidepressants, mood stabilizers and antipsychotics)32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Lithium, a well-known drug used for mood disorders, may act as a blocker of the cardiac sodium channels even at concentrations below those achieved in therapy and could unmask BrS32. Tricyclic antidepressants, as desipramine and amitriptyline, have been reported to unmask BrS33,34. Moreover, also antipsychotics as quetiapine and clozapine may unmask this feature37,38,39.

It is therefore of paramount importance a shared pharmacological evaluation between cardiologist and mental health physicians, in selected cases.

Potential psychological impact of ICD implant

The implantation of ICDs is a crucial aspect in the history of this syndrome. Despite the undeniable medical benefits of ICD treatment, living with an ICD and underlying heart disease can lead to psychological distress, with 20–30% of patients experiencing significant levels of anxiety and depression40,41,42. Prevalence of anxiety and depression is similar among patients suffering of different inherited channelopathies40. However, in a large European survey including 1644 patients with ICD about 75% of the patients had an improved quality of life after device implantation, but nearly 40% had some worries about their device41. Van der Broek et al found that, in a longitudinal study evaluating 343 patients and partners following ICD implantation, partners experienced more anxiety and patients more depression42.

Probst et al. evaluated a cohort of 190 BrS patients8. Authors found that half of the BrS symptomatic implanted patients and a quarter of the asymptomatic implanted were anxious of the potential side effects of the ICD.

Additionally, there was a strong relationship between age and negative impact related to the ICD. Indeed, younger patients referred that ICD had a worst impact on quality of life43.

The experience of shock delivered by ICD was also associated with a quality-of-life deterioration: 76% of patients who received at least one shock considered that the ICD was responsible for deterioration in their quality of life, compared with 53% of patients who never received a shock. Moreover, patients who experienced an ICD shock were more frequently concerned about potential complications (58%) than those who never received a shock (32%)8.

Which predisposing factors for new-onset psychological disorders should be considered?

The psychological impact and repercussions of this diagnosis are linked to several patient-related variables, possible comorbidities and coping behaviors, varying widely between patients. In this regard, screening BrS patients for previous psychiatric illnesses is important for a proper follow over time.

Personality plays a significant role in determining chronic stress levels21. Two overarching personality traits, negative affectivity (NA) and social inhibition (SI), are particularly relevant in this context. NA refers to a tendency to experience negative emotions consistently across various situations, leading to feelings of dysphoria, anxiety, and irritability. SI, on the other hand, involves inhibiting the expression of emotions or behaviors in social settings to avoid disapproval from others. Individuals with NA and SI are classified as having a distressed or Type D personality due to their susceptibility to chronic distress21.

Type D personality is more common in patients with BrS than in the general population. Six et al. in a cohort of 165 BrS patients found a prevalence of type D personality of 37.2%3 (Fig. 1). Moreover, Symptomatic disease presentation and older age are significantly associated with new-onset depression or anxiety19.

However, the information about potential psychological disorders is a dynamic element and requires serial evaluation43,44,45,46,47.

What is the psychological impact of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in BrS?

BrS patients are at higher risk of cardiac arrest, as outlined before7. Therefore, some of these patients may experience out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), usually before the time of BrS diagnosis. However, it is well demonstrated that a not negligible percentage of patients after OHCA may experience psychological distress, such as the development of depression and anxiety, cognitive impairment, and fatigue, which negatively affect the quality of life of both patients and their relatives47,48. Moreover, the incidence of depression in this population is higher in younger patients (<50 years old). This is not to be underestimated as having a longer life expectancy than older people it is essential to act by improving their quality of life49. The recognition of varying levels of psychological distress over time holds significance as it may impact cardiac outcomes differently among patient groups. Indeed, distinct subtypes of depression may influence behaviors related to secondary prevention rather than directly affecting cardiac outcomes21. Furthermore, depression could be one of several factors potentially responsible for the increased mortality of post-arrest patients compared to the healthy reference population50. This psychological issue is often underestimated and not sufficiently investigated and managed in the months following cardiac arrest and this is even more striking in BrS patients, considering both the fact that they are often young patients and that they are already at greater risk of psychological distress as outlined before. For this reason, as suggested by the European guidelines on the treatment of OHCA patients, a systematic follow-up of all cardiac arrest survivors, including BrS patients, after hospital discharge is needed51.

Future perspectives and potential intervention

Many patients with hereditary heart disease report levels of psychological distress that suggest the need for clinical intervention and report a reduced health-related quality of life compared to the general population52,53,54,55.

Psychological interventions can optimize patients’ treatment expectations, leading to improvements in mental quality of life56. Psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy can effectively modify personality traits, with effects persisting over time. The optimal duration of such interventions appears to be between 4 and 8 weeks, with no additional benefits observed beyond 8 weeks.

For this reason, screening BrS patients at diagnosis for the above-mentioned conditions by administering questionnaires could be useful to tailor any psychological/psychiatric follow-up to the individual’s needs, as well as to optimize therapy compliance.

In the management of Brugada syndrome, it is crucial to adopt a multidisciplinary approach addressing both psychological and pharmacological aspects. Additionally, patients with BrS who develop new-onset anxiety or depression are often prescribed medications that should be avoided in their condition19. Targeted psychological interventions for patients and their families, such as counseling, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and peer support groups, can play a crucial role in promoting the emotional well-being and psychological resilience of patients with this complex cardiac condition.

Psychological/psychiatric counseling should not stop at the stage of diagnosis but continue as needed. This should aim not only at alleviating psychological distress, but also at developing or consolidating coping-responses the patient may benefit from12.

Limitations

BrS is a rare disease, therefore few data are available in literature and it is not possible to provide strong recommendations on the attitude to take towards this category of patients. Moreover, there is a lack of information in the pediatric population.

This review does not deal in detail with the psychological and attitudinal therapies to be employed for each patient category, as they are beyond the scope of this text.

Summary of evidence

-

Previous history of psychiatric disorders before BrS diagnosis was found in 15% of patients in a registry of 263 BrS patients19;

-

Prevalence of Type D personality is 32.7% in a registry of 162 BrS patients3;

-

After BrS diagnosis, patients can develop anxiety or depression, the incidence is higher among symptomatic patients (19.3% vs 13%)19;

-

Anxiety on health status is common in BrS patients about 49% can develop it (41% moderate, 8% severe)8.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of Brugada syndrome can lead to psychological and mental health repercussions in several ways. Screening newly diagnosed BrS patients with self-reported and brief questionnaires could help identify those who may require referral, to a mental health specialist. A multidisciplinary approach including cardiologists and psychiatrists in order to establish the most suitable psychopharmacological treatment should be considered.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Zeppenfeld, K. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur. Heart J. 43, 3997–4126 (2022).

Van der Werf, C. et al. The psychological impact of receiving a Brugada syndrome diagnosis. Europace 25, euad293 (2023).

Six, S. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures on mental health and psychosocial factors in patients with Brugada syndrome. Europace 25, euad205 (2023).

Postema, P. G. et al. Drugs and Brugada syndrome patients: review of the literature, recommendations, and an up-to-date website (www.brugadadrugs.org). Heart Rhythm 6, 1335–1341 (2009).

Giustetto, C. et al. Etiological diagnosis, prognostic significance and role of electrophysiological study in patients with Brugada ECG and syncope. Int J. Cardiol. 241, 188–193 (2017).

Bergonti, M. et al. Implantable loop recorders in patients with Brugada syndrome: the BruLoop study. Eur. Heart J. 45, 1255–1265 (2024).

Conte, G. et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in Brugada syndrome: a 20-year single-center experience. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 879–888 (2015).

Probst, V. et al. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: results from the FINGER Brugada syndrome registry. Circulation 121, 635–643 (2010).

O’Donovan, C. et al. How patient perceptions shape responses and outcomes in inherited cardiac conditions. Heart Lung Circ. 29, 641–652 (2020).

Conte, G. et al. Diagnosis, family screening, and treatment of inherited arrhythmogenic diseases in Europe: results of the European Heart Rhythm Association Survey. Europace 22, 1904–1910 (2020).

Attard, A., Stanniland, C., Attard, S., Iles, A. & Rajappan, K. Brugada syndrome: should we be screening patients before prescribing psychotropic medication? Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 12, 20451253211067017 (2022).

Hagger, M. S. et al. The common sense model of self-regulation: meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychol. Bull. 143, 1117 (2017).

Hendriks, K. S. et al. High distress in parents whose children undergo predictive testing for long QT syndrome. Community Genet. 8, 103–113 (2005).

Ingles, J. et al. Posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief after the sudden cardiac death of a young relative. JAMA Intern. Med. 176, 402–405 (2016).

O’Donovan, C. E. et al. Predictors of b-blocker adherence in cardiac inherited disease. Open Heart 5, e000877 (2018).

Grenard, J. L. et al. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26, 1175–1182 (2011).

Gehi, A. et al. Depression and medication adherence in outpatients with coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 165, 2508–2513 (2005).

Sutjaporn, B. et al. Quality of life and related factors of patients with Brugada syndrome type 1 at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Chulalongkorn Med. J. 66, 5 (2022).

Jespersen, C. H. B. et al. Severity of Brugada syndrome disease manifestation and risk of new-onset depression or anxiety: a Danish nationwide study. Europace 25, euad112 (2023).

Oldridge, N. et al. The HeartQoL: part II. Validation of a new core health-related quality of life questionnaire for patients with ischemic heart disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 21, 98–106 (2014).

Pedersen, S. S. et al. Relation of symptomatic heart failure and psychological status to persistent depression in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Am. J. Cardiol. 108, 69–74 (2011).

Carver, C. S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J. Behav. Med. 4, 92–100 (1997).

Goldberg, D. P. et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol. Med. 27, 191–197 (1997).

Kocalevent, R. D. et al. Social support in the general population: standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3). BMC Psychol. 6, 31 (2018).

Isbister, J. C. et al. Brugada syndrome: clinical care amidst pathophysiological uncertainty. Heart Lung Circ. 29, 538–546 (2020).

Williams, L. et al. Health behaviour mediates the relationship between Type D personality and subjective health in the general population. J. Health Psychol. 21, 2148–2155 (2016).

Mols, F. et al. Type D personality in the general population: a systematic review of health status, mechanisms of disease, and work-related problems. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 8, 9 (2010).

Gosling, S. D. et al. A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. J. Res. Pers. 37, 504–528 (2003).

Hendriks, K. et al. Familial disease with a risk of sudden death: a longitudinal study of the psychological consequences of predictive testing for long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 5, 719–724 (2008).

Balaraman, Y. et al. Variants in ion channel genes link phenotypic features of bipolar illness to specific neurobiological process domains. Mol. Neuropsychiatry 1, 23–35 (2015).

Kalcev, G. et al. Insight into susceptibility genes associated with bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 25, 5701–5724 (2021).

Darbar, D., Yang, T., Churchwell, K., Wilde, A. A. & Roden, D. M. Unmasking of Brugada syndrome by lithium. Circulation 112, 1527–1531 (2005).

Akhtar, M. et al. Brugada electrocardiographic pattern due to tricyclic antidepressant overdose. J. Electrocardiol. 39, 336–339 (2006).

Palaniswamy, C. et al. Brugada electrocardiographic pattern induced by amitriptyline overdose. Am. J. Ther. 17, 529–532 (2010).

Santoro, F. et al. Fever following Covid-19 vaccination in subjects with Brugada syndrome: incidence and management. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 33, 1874–1879 (2022).

Rodrigues, R. et al. Brugada pattern in a patient medicated with lamotrigine. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 32, 807–810 (2013).

Brunetti, N. D. et al. Inferior ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction or an inferior-lead Brugada-like electrocardiogram pattern associated with the use of pregabalin and quetiapine? Am. J. Ther. 23, e1057–e1059 (2016).

Blom, M. T. et al. Brugada syndrome ECG is highly prevalent in schizophrenia. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 7, 384–391 (2014).

Sawyer, M. et al. Brugada pattern associated with clozapine initiation in a man with schizophrenia. Intern Med J. 47, 831–833 (2017).

Singh, S. M. et al. Anxiety and depression in inherited channelopathy patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Heart Rhythm O2 2, 388–393 (2021).

Haugaa, K. H. et al. Patients’ knowledge and attitudes regarding living with implantable electronic devices: results of a multicentre, multinational patient survey conducted by the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 20, 386–391 (2018).

Van Den Broek, K. C. et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator and their partners: a longitudinal study. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 36, 362–371 (2013).

Reitan, R. M. & Wolfson, D. The use of serial testing in evaluating the need for comprehensive neuropsychological testing of adults. Appl. Neuropsychol. 15, 21–32 (2008).

Leventhal, H. et al. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J. Behav. Med. 39, 935–946 (2016).

DeDios-Stern, S. et al. Clinical utility and psychometric properties of the Brief: coping with problems experienced with caregivers. Rehabil. Psychol. 62, 609–610 (2017).

Wilski, M. et al. Health locus of control and mental health in patients with multiple sclerosis: mediating effect of coping strategies. Res. Nurs. Health 42, 296–305 (2019).

Lilja, G. et al. Anxiety and depression among out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation 97, 68–75 (2015).

Baldi, E. et al. Depression after a cardiac arrest: an unpredictable issue to always investigate for. Resuscitation 127, e10–e11 (2018).

Grand, J. et al. Sex differences in symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and cognitive function among survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 12, 765–773 (2023).

Baldi, E. et al. Long-term outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: an utstein-based analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 764043 (2021).

Nolan, J. P. et al. European resuscitation council and European society of intensive care medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 47, 369–421 (2021).

Steptoe, A. et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 5797–5801 (2013).

Holt-Lunstad, J. et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for CVD: implications for evidence-based patient care and scientific inquiry. Heart 102, 987–989 (2016).

Rottmann et al. Psychological distress in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator and their partners. J. Psychosom. Res. 113, 16–21 (2018).

Ingles, J. et al. Health status of cardiac genetic disease patients and their at-risk relatives. Int. J. Cardiol. 165, 448–453 (2013).

Rief, W. et al. Preoperative optimization of patient expectations improves long-term outcome in heart surgery patients: results of the randomized controlled PSY-HEART trial. BMC Med. 15, 4 (2017).

Acknowledgements

No funding was provided for data collection, data analysis, manuscript review, writing, preparation, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

F.S., A.M., E.B., I.L. conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, visualization. F.S. prepared figures and tables. L.D.B., A.C., M.T., I.R., M.A., G.N., M.A., A.B., N.D.B., A.R. writing—review & editing. A.R. and N.D.B. conceptualization, supervision, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santoro, F., Di Biase, L., Curcio, A. et al. Psychological profile of patients with Brugada syndrome and the impact of its diagnosis and management. npj Cardiovasc Health 2, 3 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-024-00042-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-024-00042-6