Abstract

Fabry disease (FD, OMIM #301500) is a lysosomal disease caused by the inappropriate accumulation of globotriaosylceramide in tissues due to a functional deficiency in the enzyme α-galactosidase A. Fabry cardiomyopathy is now the most common cause of mortality in patients with FD. Large-scale metabolic and genetic screening studies have revealed FD to be more prevalent than previously thought and the later-onset variant form of FD represents an unrecognized health burden. Genetic testing is critical for the diagnosis of FD and echocardiography with strain imaging and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging using late-enhancement and T1 mapping are important imaging tools. Current therapies for FD are enzyme replacement therapy and, in patients with an amenable GLA pathogenic variant, pharmacological chaperone therapy, which can prevent FD progression, while gene therapy and the use of substrate reduction therapy represent promising novel therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1898 Johannes Fabry and William Anderson both independently described Fabry disease (FD) after observing patients with ‘angiokeratoma corporis diffusum’—the red-purple maculopapular skin lesions that are now recognised as a characteristic feature of the disorder1,2,3. It was not until 1925 that the cardiac and hereditary nature of the disease were reported and it is these cardiac manifestations, characterised by structural, vascular, valvular, rhythm and conduction abnormalities and heart failure, that alongside kidney involvement and cerebrovascular disease, drive impaired quality of life and premature mortality in patients with FD4.

For most of its history, FD has languished as a neglected rare genetic disease. At the turn of the millennium, groundbreaking developments in the diagnosis of genetic diseases and the emergence of disease-modifying treatments have both considerably elevated interest in FD. Next-generation sequencing, leveraging the genetic information from the human genome project, has significantly enhanced our diagnostic capabilities5, revealing a higher burden of disease than previously thought by facilitating differentiation of FD, in particular in its later-onset form, from other causes of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and other phenocopies of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) can prevent or slow down disease progression and irreversible organ damage6,7,8,9 and has sparked interest in screening for FD with the aim of early recognition and initiation of treatment. Migalastat, an oral pharmacologic chaperone and pegunigalsidase alfa, a pegylated recombinant alpha-galactosidase, were more recently approved10,11 and investigational therapies including gene therapy, other modified enzymes and substrate reduction therapy are on the horizon12,13,14,15. More recent advances in multimodality imaging, namely echocardiography with strain imaging and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) using late-enhancement, T1 and T2 mapping, have also emerged as important imaging tools.

This paper will review these recent advances whilst also discussing expert management recommendations, which emphasise timely treatment, individualised care and multi-disciplinary input.

Pathophysiology

FD (OMIM 301500) results from pathogenic variants in the human GLA gene located on the long arm of chromosome X at Xq22.1 and coding for the lysosomal enzyme α-galactosidase A (α-Gal A)16,17. Over 1000 GLA gene variants are reported18, categorising the disease into an early-onset, classic form associated with dramatically decreased (<3%) or absent α-Gal A activity or a later-onset (‘variant’) form in which residual α-Gal A activity (<25% in males) is present19,20. Due to skewed (non-random) X-chromosome inactivation, resulting in a higher proportion of X-chromosomes expressing the pathogenic variant, some heterozygous females are also at risk of manifesting any or all of the signs and symptoms of FD and of progressing to advanced disease, while random X-chromosome inactivation usually leads to an attenuated and delayed phenotype. The lack of α-Gal A activity leads to the accumulation of the enzyme’s glycosphingolipid substrate globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and the latter’s deacylated derivative globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) in lysosomes and in body fluids (notably the blood).

The accumulation of Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 in lysosomes leads to lysosomal dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and cell death. In turn, the latter phenomena leads to fibrosis (mainly affecting the heart and the kidneys), small vessel damage and tissue ischaemia21. Inflammatory and cardiac remodelling biomarkers are elevated in patients with FD consistent with heart disease leading to heart failure (usually with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 50%)22.

In FD patients, histological and pathological features of the cardiovascular system include cardiomyocyte vacuolisation, concentric LVH, mid-wall fibrosis in the left ventricle, myocardial scarring, diffuse wall thickening in the coronary arteries and heart valve thickening23,24,25,26.

Gb3 accumulates in all cardiac cells, including cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts in the cardiac valves, the heart’s conduction system and endothelial cells27. The resulting endomyocardial and endothelial cell dysfunction28 precedes the cardiovascular signs and symptoms typical of FD (Fig. 1), making diagnosis challenging29. The main clinical consequence of lyso-Gb3 accumulation (rather than Gb3 accumulation) appears to be an increase in intima-media thickness30,31 and HCM20. Structural and functional changes to intramural vessels lead to myocardial ischaemia and electrical abnormalities32,33. Although catalytic deficiency of mutated α-Gal A is central to the pathogenesis of FD, certain GLA missense mutations may result in alternative pathogenic mechanisms, particularly in variant FD, including endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response, although external confirmation of these processes is warranted34.

Epidemiology of Fabry disease

Prevalence in the general population

While historical estimates of FD incidence were as low as 1 in 40,000 males35, neonatal dried bloodspot screening for α-Gal A activity deficiency in separate populations of Japanese, Austrian, Chinese-Taiwanese and Italian neonates suggest that the prevalence of FD might be higher than previously reported36,37,38,39. Indeed, of 21,170 Japanese neonates, 1 in 3024 were test positive; of 34,736 Austrian neonates, 1 in 3859 were test positive; of 110,027 Chinese-Taiwanese neonates, 1 in 1642 were test-positive; and of 37,104 Italian neonates, 1 in 3100 were test positive. These results suggested a hitherto unrecognised burden of FD. However, genetic testing subsequent to the dried blood spot screening programs revealed varying proportions of confirmed GLA pathogenic variants in newborns with α-Gal A deficiency. In the aforementioned studies, the majority of the confirmed GLA mutations were associated with variant phenotypes and occasionally variants of unknown significance and even (likely) benign variants. The penetrance of some GLA variants may be affected by the presence of systemic comorbidities, which are likely to develop later in life, such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes and smoking. It is therefore difficult to ascertain the risk posed to neonates who are diagnosed with GLA variants associated with non-classical disease, and long-term follow-up studies are clearly required. In any case, newborns bearing a benign or likely benign variant of GLA should not be diagnosed with FD40.

Prevalence in cohorts with cardiomyopathies

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies evaluating the prevalence of FD in patients with LVH/HCM and a recognised GLA variant identified 10,080 screened patients across 26 studies. Using recommendations from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), the gold standard for pathogenicity assignment, 8 variants were downgraded from pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) to variant of uncertain significance (VUS) or benign/likely benign (B/LB) (affecting 24 patients) and 4 were upgraded from VUS/B/LB to P/LP (affecting 10 patients), resulting in a pooled prevalence of FD in patients with LVH/HCM of 1.2%41. These results are also consistent with a cohort-based screening study in Edmonton and Hong Kong, where the prevalence of FD in patients with concentric LVH was 2%42.

Screening studies have also revealed that variant FD might contribute significantly to the prevalence of unexplained or idiopathic cardiovascular disorders. In small screening studies for late-onset HCM in Japanese and UK males, FD was detected in 3% and 6.3% of patients, respectively43,44. Furthermore in a large consecutive cohort of 1386 European patients with unexplained LVH, 0.5% had GLA mutations associated with FD45. All together, these data suggest that the prevalence of variant FD is higher than previously predicted.

However, some degree of caution must be exercised as the penetrance of mutations associated with variant FD can vary considerably. A recent review by van der Tol et al. suggests that new diagnostic algorithms are necessary to ensure that patients with FD are appropriately recognised including ruling out FD in ambiguous cases of low α-Gal A activity46. Moreover, whilst Fabry cardiomyopathy can be clinically indistinguishable from other genetic hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, suggesting that systematic mutation screening is necessary to better define FD patients47, it is important to remember that several GLA variants have been reclassified over the last decades from P/LP to VUS or B/LB and that there is significant discrepancy in the assignment of pathogenicity between ACMG and ClinVar, a public database commonly used in clinical practice41. Furthermore, the ACMG criteria has occasionally been challenged by genetic experts in the GLA gene30.

Clinical manifestations

Cardiac involvement is highly prevalent and affects >80% of patients with FD; it includes progressive LVH, heart failure (HF), atrial fibrillation (AF), angina, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia and other arrhythmias, syncope and chronotropic incompetence (see Fig. 1)48,49. There is, however, considerable variation in the clinical spectrum of FD, which is dependent on gender, pathogenic variant and degree of lyonization (in females) and ranges from severe early-onset disease in males (classic FD) to asymptomatic females bearing a GLA variant associated with the later-onset phenotype – and a variety of presentations in between50,51.

Classic Fabry disease

This is the most severe clinical phenotype of FD and typically affects males, although some heterozygous females can manifest full classic expression of the disease due to unfavourable lyonization. Patients with classic FD typically develop early-onset symptoms from 4 to 8 years old. These patients have very low or absent α-Gal A activity, resulting in non-specific signs and symptoms that are often mistakenly attributed to alternative disorders, leading to missed or delayed diagnoses, by which time end-organ damage may be irreversible52,53. Life expectancy is usually reduced, with a mean age at death of ~41 years.

The major manifestations of classical FD are cardiac, renal and neurological and these can be partially attributed to vascular endothelial dysfunction53,54. More than 80% of classic FD patients will develop cardiac manifestations, which usually present between 20 and 40 years of age, although heterozygous females typically present 10 years or later compared to males55. Cerebrovascular manifestations include early stroke and transient ischaemic attacks, which can lead to significant neurological deterioration and death56. Renal involvement may progress to the point of requiring dialysis or renal transplantation57,58.

According to the organs involved, a number of additional symptoms and signs can be found, including pain and neuropathy in the distal limbs (acroparesthesias); gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, such as diarrhoea, abdominal pain and early satiety; benign cutaneous lesions of small blood vessels (angiokeratomas); and corneal opacities (so-called cornea verticillata)59,60,61,62. Peripheral neurological manifestations often present earliest, but these symptoms are not definitive due to their transient and variable nature4,52.

Late-onset (variant) Fabry disease

Those with variant FD typically manifest symptoms from the 4th to the 7th decades and age at death is typically >60 years old63. Variant FD is usually dominated by cardiac involvement, and typically lacks the systemic disease manifestations that characterise classical FD. These patients are usually diagnosed following evaluation for cardiomegaly, stroke, or proteinuria and may not have a known family history of FD44,48,52,64.

Cardiovascular complications of Fabry disease

Although unexplained LVH is the well-recognised imaging hallmark of cardiac FD65 the clinical sequelae of FD remains under-recognised and is an important cause of HF with an LVEF ≥ 50% and ventricular arrhythmias in men aged >40 years old and women aged >50 years old66. Indeed, diastolic dysfunction can precede LVH and occur early in the FD disease course67,68, although HF with an LVEF ≥ 50% in FD patients should not be labelled as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (‘HFpEF’), given that its pathophysiology, natural history and treatments differ to typical HFpEF patients69. In a FD registry of 2869 patients, HF was the most common first cardiovascular event. Overall, 5.8% of males and 3.7% of females at mean ages of 45 and 54 years, respectively, experienced cardiovascular events, which also included myocardial infarction and cardiac death70.

Ventricular hypertrophy

In a screen of FD patients, left ventricular mass index inversely correlated to α-Gal A activity, which suggests that the extent of Gb3 accumulation determines the relative extent of pathogenesis in FD71. Unlike male patients, myocardial functional decline and fibrosis do not always coincide with LVH in female patients with FD72,73,74. There is a strong correlation between age and the severity of LVH and all female FD carriers older than 45 years have LVH75.

Myocyte involvement results in progressive LVH and fibrosis, diastolic dysfunction and elevated filling pressures, leading to HF. In a minority of cases—usually advanced FD—patients may present with reduced ejection fraction. In adults, ECG signs of LVH are present in up to 61% of men and 18% of women76. In addition, the high prevalence of obesity and hypertension as a pan-ethnic health burden, coupled with presently long average life expectancy, can further exacerbate variant forms of FD, thereby contributing significantly to the incidence of HF77,78.

Concentric LVH is the most common pattern of hypertrophy observed, although asymmetric and eccentric remodelling may also occur79. Up to 5% of FD patients may develop asymmetric septal hypertrophy and although patients may also develop reduced LV cavity sizes and papillary muscle hypertrophy, which can lead to exercise intolerance, dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) appears to be rare, affecting <1% of patients43,80. More than one third of FD patients have right ventricular involvement, although this rarely complicates the disease course81.

Arteriopathy

The accumulation of GB3 in the walls of the arterial tree results in abnormally increased intima-medial thickness, resulting from hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the vascular smooth muscle cells30,31,82,83,84,85, which occurs independently of hypertension, intramural inflammation and atherosclerosis86.

Angina is a frequent symptom in FD patients, affecting women and men roughly equally (22% vs 23%, respectively) in an international FD outcome survey48. Although epicardial coronary artery disease can occur, microvascular dysfunction is typically the central underlying mechanism and replacement myocardial fibrosis is often found at areas of severe small vessel disease87. Vessel dilation is also commonly seen, particularly in the basilar trunk and ascending aorta and previous studies have demonstrated ascending aortic dilation in ~30–56% of males and 21% of females76,88,89,90. Aortic root dilation is usually not severe enough to require valve or root replacement.

Conduction disorders and arrhythmias

Both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias occur in FD91. Myocardial fibrosis is associated with malignant ventricular arrhythmias (annual incidence 27%) and sudden cardiac death (annual incidence 5%) in FD patients, whilst patients without late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) did not experience malignant ventricular arrhythmias68. AF is common in FD, affecting males more commonly than females91. In younger patients, the PR interval may be shorter due to accelerated atrioventricular conduction (Fig. 2), whereas older patients may develop PR prolongation and bundle branch block (left anterior fascicular block and right bundle branch block)92. Complete heart block is observed in 12.7% of males and 1.6% of females in variant FD with cardiac involvement92.

This ECG shows a shortened PR interval, LVH by Sololow-Lyon criteria and LV strain pattern. Reproduced with permission from Linhart A81. ECG electrocardiogram, LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, LV left ventricular hyertrophy.

Valvulopathy

The left-sided heart valves are predominantly affected in FD, even though the pathological accumulation of Gb3 is present in both sides of the heart. This could be explained by the increased pressure in the left heart leading to a more rapid deterioration of the mitral and aortic valves81,93. Mitral leaflet thickening, with corresponding moderate or severe mitral regurgitation, is typically present in more than 50% of patients, while minor aortic valve thickening is found in nearly 50% of patients, which can progress to moderate or severe regurgitation (Fig. 3A, B)26,71,76.

A Echocardiogram showing marked interventricular sepal thickening (2.15 cm) and thickening of the MV (white arrows); B Echocardiogram with colour Doppler showing mild-moderate MR. Reproduced with permission from Linhart81. MV mitral valve, MR mitral regurgitation, LA left atrium, RA right atrium.

Diagnosis

Cardiac manifestations are the presenting symptoms in only 10–13% of patients with FD and usually only present from the third decade onwards70,94,95, whilst patients younger than 20 years are unlikely to manifest severe LVH (>15 mm)49. The non-specific signs, symptoms and complex multi-organ nature of the disease make it difficult to clinically suspect the disease without prior known family history. However, given that newer therapies may favourably alter the disease course, early diagnosis remains a vital goal.

Once a patient with suspected FD is identified, diagnosis is established after careful evaluation of FD red flags, assessment of α-Gal A activity and lyso-Gb3 measurement (in male patients), GLA genetic testing (all female patients and male patients with reduced enzymatic activity), and advanced cardiac imaging, as summarised in Fig. 496 and discussed in the following sections.

aSee Table 1. bGenetic analysis must include the study of possible large deletions or a copy number variation not detected by the Sanger technique. cThe finding of increased plasma and/or urinary Gb3, or plasma lyso Gb3 and its analogues in the evaluation of male or female patients with a VUS and normal (in female patients) or lowered α-Gal A activity provides additional diagnostic information, but the role of biomarkers in such patients still requires validation. dLow native T1 values reinforce or generate suspicion of Fabry disease. Normal native T1 values do not exclude Fabry disease, as they are rarely observed in untreated patients with mild LVH (mostly females), or in advanced disease due to pseudonormalization. eAn endomyocardial biopsy is recommended, but could be done in other affected organs such as the kidneys and skin. It should be evaluated by expert pathologists and always include electron microscopy studies to detect lamellar bodies and intracellular inclusions. Of note, some drugs may produce drug-induced phospholipidosis with an intracellular accumulation of phospholipids in different organs that can mimic zebra bodies on electron microscopy. α-Gal A alpha-galactosidase A, AFD Anderson–Fabry disease, CMR cardiac magnetic resonance, Gb3 globotriaosylceramide, HCM hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, lyso Gb3 globotriaosylsphingosine, P/LP pathogenic/likely pathogenic, VUS variant of unknown significance. Reproduced with permission from Arbelo et al.96.

When to suspect cardiac Fabry disease

FD should be suspected in any patient with LVH or cardiomyopathy, particularly HCM and restrictive cardiomyopathy, even in the presence of comorbidities such as hypertension or aortic stenosis because FD can co-exist with these conditions97. Moreover, FD accounts for ~0.3–5% of patients previously labelled as HCM, therefore it is vital to maintain a high index of suspicion and exclude FD in all HCM cases43,98,99. In addition to LVH, presence of unexplained HF with an LVEF ≥ 50%, ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac and extracardiac red flags (Table 1)96, with variable sensitivity and specificity, may further increase the suspicion for FD.

Diagnostic and genetic testing: importance of gender

The challenge of elucidating whether uncharacterised genetic variants are responsible for clinical manifestations of illness underscores the need for more rigorous diagnostic criteria for FD46,100,101. De novo mutations are rare and thus most affected males have mothers who are carriers. Traditionally, FD was diagnosed in males by markedly deficient or absent α-Gal A activity in plasma or peripheral leucocytes; however, evidence of α-Gal A pseudodeficiency suggests that confirmation of FD should be made using genetic testing when α-Gal A activity assay is ambiguous102.

Clinical manifestations in heterozygous female carriers range from asymptomatic to severe disease, although symptoms may initially appear mild. In a FD registry of 1077 enroled females, 69.4% had symptoms and signs of FD55 and the majority of female FD patients developed clinically significant disease. Carrier detection by enzyme analysis is not reliable in females, since α-Gal A activities range from very low to normal in heterozygotes and any female patient being evaluated for FD must undergo genetic testing47.

Imaging evaluation of Fabry cardiomyopathy

Assessment of cardiac structural and functional abnormalities in FD can be obtained by a number of imaging modalities, including echocardiography (LVH, wall thickness, diastolic filling, valvular abnormalities) and CMR. Echocardiography has been used as a standard non-invasive screening test for Fabry cardiomyopathy for many years. However, only ~40% of patients have LVH at the time of FD diagnosis, which makes recognising cardiac involvement difficult using conventional echocardiography76. In addition, changes in LV diastolic function, as assessed by conventional Doppler echocardiography, have also been variable103,104. The challenge to conventionally diagnose FD is the significant overlap with other cardiovascular pathologies in terms of structural and functional alterations. More specificity might be achieved by way of novel approaches that exploit unique elements of the FD phenotype.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography can be used to assess LV remodelling and hypertrophy, estimating LV mass and assessing valvular function. New methods of strain and strain rate (SR) echocardiography have had satisfactory results for the detection of subclinical stages of impaired myocardial contractility and diastolic dysfunction in FD105. Tissue Doppler-derived strain and SR have been previously shown to be useful for detecting subclinical stages of impaired regional longitudinal and radial function in FD patients with otherwise normal ejection fraction103. In addition, peak systolic strain and SR improve with ERT, indicating that SR imaging may be a useful tool in monitoring the efficacy of treatment6,8.

Recent evidence shows that strain and SR analyses derived from two-dimensional speckle-tracking techniques can identify FD, independent of concentric remodelling and hypertrophy, with more sensitivity and specificity than conventional tissue Doppler echocardiography67. After correcting for LVH, SR during isovolumic relaxation (SRIVR) and transmitral E-wave velocity to SRIVR ratio, remained predictors of FD by ROC analysis. Longitudinal systolic strain was also significantly lowered in FD patients compared to healthy controls67. Speckle-tracking imaging can provide evidence of subclinical myocardial dysfunction associated with reduced contractile reserve and diastolic dysfunction in patients with FD106.

Cardiac MRI

CMR plays a critical role in evaluating the differential diagnosis of cardiomyopathies and to characterise the structural function of the heart in patients with FD. CMR can reliably detect hypertrophy, hypokinesia and areas of delayed enhancement in patients with FD23,107 and is also a suitable tool for evaluating the beneficial effects of ERT on LV mass in FD patients108 and to delineate gender differences in LV remodelling74,105,109. Furthermore, CMR is sensitive to the way in which intracellular accumulation of Gb3 in FD alters the biochemical environment of the heart. It is important to note however that CMR with T1 mapping requires careful calibration and expertise, often requiring collaboration with specialised cardiac imaging centres. Collaboration with other reference centres also helps circumvent shortfalls in the availability of CMR techniques, which are not accessible in many centres. Care also needs to be made when interpreting and comparing results across different machines.

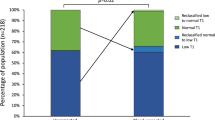

T1 mapping reveals differences in tissue pathophysiology and can elucidate biochemical differences that might not be structurally apparent, such as in idiopathic versus Fabry cardiomyopathy110. While FD-induced hypertrophy is structurally indistinguishable from other types of HCM, our group and Sado et al. have shown that non-contrast T1 mapping can distinguish FD from other etiologies of concentric remodelling and hypertrophy, whereby septal T1 times are significantly lower in FD patients than control or concentric remodelling patients (Fig. 5A, B and Supplementary Video 1)74,111. Structural analyses revealed that FD and concentric hypertrophy did not differ in terms of cardiac mass, LV chamber volume, mass to LV chamber volume ratio, or wall thickness74. Likewise, LVH was a common finding in diverse patient groups, including FD, hypertension and cardiac amyloidosis111. In both studies, T1 relaxation time was significantly lower in FD, which is likely to be a consequence of increased lipid content in the intracellular compartment of cardiomyocytes in FD74. Furthermore, these studies established that T1 cutoff values could be derived that separated FD from other conditions with LVH with high sensitivity and specificity111.

Artificial intelligence

Formative studies evaluating the potential application of artificial intelligence (AI) in the diagnosis of FD have been encouraging, including those using medical history data alone (signs and symptoms, laboratory data, medication history, procedures and medical diagnoses)112, ECG analysis (with algorithms that can distinguish patients with clinical from those with subclinical cardiac involvement)113 and CMR analysis (distinguishing between HCM and FD)114.

One particularly effective AI application to echocardiography may be to help circumvent the well-known challenges of reproducing accurate measurements of LV wall thickness115, which clearly has significant implications for the diagnosis and treatment of FD. A machine-learning algorithm was more accurate and reproducible when measuring maximum wall thickness on a test-retest basis (patients were scanned twice on the same day) compared to 11 human experts in a large multicentre study of 60 patients with HCM (a difference of 0.7 mm vs 1.1–3.7 mm, respectively)116.

Medical management

FD patients should be followed regularly, regardless of disease status, by a multidisciplinary team that will be able to handle the heterogeneity and variability of FD. Although signs and symptoms will dictate the frequency and extent of follow up, comprehensive medical evaluation at least once a year is recommended in all males with FD as well as females with classic phenotypes. Once a diagnosis of FD is confirmed, all individuals should have a detailed medical and family history taken. All signs and symptoms should be carefully documented at baseline and then at least annually or more often, as the clinical situation dictates. Even in the absence of symptoms, all known heterozygous females should be considered at risk for developing disease manifestations and should have a complete baseline examination. Symptomatic heterozygotes should be followed annually with tests focused on their disease manifestations, while asymptomatic females can be re-evaluated every 2 years. A summary of the approach to the initiation of disease-specific therapies is summarised in Fig. 6.

Enzyme replacement therapy

ERT, first introduced in 2001, was the first disease-modifying therapy available for FD117,118 and in the decades since its establishment, clinical evidence has shown that either agalsidase-α (Replagal®, Takeda) or agalsidase-β (Fabrazyme®, Sanofi) slows, but does not reverse, the progression of cardiovascular disease in FD, with a decrease in LV mass, improved systolic and diastolic functions and a reduction in adverse cardiovascular events such as sudden cardiac death. Furthermore, ERT improves pain scores and quality of life assessments in FD patients119.

There is a growing body of evidence that ERT may be most beneficial in patients who have not yet developed substantial myocardial fibrosis at the time of initiation of therapy8,120. Indeed, among the typical features of Fabry cardiomyopathy is the development of replacement fibrosis in the basal postero-lateral segments. The fibrotic process starts in the mid-myocardial layers and spreads with disease progression towards transmural fibrosis. Thus, end-stage Fabry cardiomyopathy is characterised by the co-existence LVH and myocardial thinning.

The observed decrease in left ventricular mass among older untreated men could reflect an even more advanced stage of myocardial fibrosis. In the late stages of transmural fibrosis associated with LVH, cardiomyocyte death can induce scar tissue and thinning of the left-ventricular posterolateral wall121 that may be misinterpreted as a therapeutic response to enzyme replacement or chaperone therapy73.

The 5-year follow-up data on 181 adults (126 men) in the Fabry Outcome Survey showed that ERT with agalsidase-α was associated with (i) a significant reduction in LV mass and a significant increase in midwall fractional shortening in patients with cardiac hypertrophy at baseline, and (ii) stable values for these variables in patients without cardiac hypertrophy at baseline122,123. However, myocardial Gb3 content did not significantly decrease on endomyocardial biopsies taken at 6 months of treatment with agalsidase alfa124.

In a longitudinal analysis of data from the Fabry Registry, male patients with FD treated with agalsidase-β (1 mg/kg/2 weeks) for at least 2 years were compared with untreated men with FD73. When considering individuals in whom ERT was initiated between the ages of 18 and 30 (n = 31), the mean change in LV mass was −3.6 g/year (i.e. a reduction); this contrasted with a mean gain (a change of +9.5 g/year) in untreated men in the same age group. Initiation of ERT at later ages was still associated with annual gains in LV mass but these were smaller than in untreated men of the same age73.

In a Cochrane review of 77 cohort studies involving 15,305 participants, the pooled proportions were as follows for cardiovascular complications: agalsidase alfa 28% [95% CI 0.07, 0.55; I2 = 96.7%, p < 0.0001]; agalsidase beta 7% [95% CI 0.05, 0.08; I2 = not applicable]; and untreated patients 26.2% [95% CI 0.149, 0.394; I2 = 98.8%, p < 0.0001]. Effect differences favoured agalsidase beta compared to untreated patients125. Data on cardiac outcomes and benefits for the newly approved pegunigalsidase alfa enzyme, which exhibits improved pharmacokinetics parameters, are still scarce11.

Although ERT has cardiac benefits in both sexes, the heterogeneity of disease severity in women means that the data are less robust in these patients55. The evaluation of ERT efficacy in the later-onset forms of the disease with predominant cardiac involvement has been limited to a few studies in the IVS4 + 919 G > A pathogenic variant, highly prevalent in several Asian countries. In those individuals, a significant negative correlation has been published between ERT duration and Gb3 storage in cardiomyocytes and cardiomyocyte size.

Initiation of ERT should follow a multi-modality assessment. However, the potential inadequacy of ERT in some FD patients, whereby disease progression is not appreciably arrested coupled with the high annual cost of ERT (~$200,000 USD) creates a need for novel alternatives to ERT or possible adjuvant therapies for the existing ERT regimen126,127. Moreover, inadequate distribution of administered enzyme to various organs and tissues due to inequities in flow dynamics and receptor distribution in various tissues may limit ERT effectiveness128. Finally, in vitro evidence has shown that ERT-induced Gb3 clearance may not fully abolish dysregulated autophagy and fibrosis in podocytes, suggesting that Gb3-independent pathways may be implicated in FD pathophysiology129, and although this hypothesis that has been supported by others130, further research is warranted.

New directions: chaperone therapy and gene therapy

Competitive α-Gal A inhibitors, or pharmacological chaperones, represent a paradoxical target for new therapies, whereby inhibitor molecules interact with and allow proper folding of otherwise misfolded, unstable α-Gal A variants131,132.

Migalastat is a first-in-class, orally administered chaperone that has been authorised by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of FD in individuals aged 12 and over with an eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and an amenable GLA pathogenic variant133. In a controlled trial of 67 previously ERT-(pseudo)naïve patients who started on migalastat, the mean LV mass index fell over the following 18 or 24 months of treatment (giving a mean [95% confidence interval] decrease of 7.7 [−15.4 to −0.01] g/m2)10. Migalastat was also effective on cardiac geometry (LV mass index and the interventricular septum thickness) in ERT-experienced patients who switch to migalastat134,135. Improvements in the LV mass and other variables (notably LGE on CMR, and blood troponin and NT-proBNP levels) have been suggested in various case series, observational studies and clinical trials136,137,138,139,140,141. Substrate reduction therapies142 and gene therapies are currently in development for the treatment of FD.

Risk factor management and supportive care

Cardiovascular risk factor modification and treatment of HF, angina, arrhythmias and conduction disorders generally follow standard guideline recommendations, with a few important caveats that are summarised in Table 2.

Conclusion

FD is an important metabolic disorder that can cause severe, variable disease manifestations in affected individuals. Large-scale metabolic and genetic screening studies have revealed FD to be more prevalent than historically thought in populations of diverse ethnic origins. Fabry cardiomyopathy, which is characterised by structural, valvular, vascular and conduction abnormalities, is now the most common cause of mortality in patients with FD. Since FD is an X-linked condition, women typically have a milder but still significant burden of Fabry cardiomyopathy. Genetic testing is widely available and plays a critical role in the diagnosis of patients with FD. With the advent of effective ERT and the continued advancement in diagnostic and evaluative methods and therapeutic agents, one should increasingly be able to provide an early diagnosis in the disease course and initiate treatment before organ damage becomes irreversible.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Fabry, J. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Purpura haemorrhagica nodularis (Purpura papulosa haemorrhagica Hebrae). Arch. Dermatol. Syph. 43, 187–200 (1898).

Anderson, W. A case of “angeiokeratoma”. Br. J. Dermatol. 10, 113–117 (1898).

Fabry, H. An historical overview of Fabry disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 24(Suppl 2), 3–7 (2001).

Mehta, A. et al. Natural course of Fabry disease: changing pattern of causes of death in FOS - Fabry outcome survey. J. Med. Genet. 46, 548–552 (2009).

Hwu, W. L. Deciphering the diagnostic dilemma: a comprehensive review of the Taiwanese cardiac variant in Fabry disease. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 123, 738–743 (2024).

Weidemann, F. et al. Improvement of cardiac function during enzyme replacement therapy in patients with Fabry disease: a prospective strain rate imaging study. Circulation 108, 1299–1301 (2003).

Hongo, K. et al. The beneficial effects of long-term enzyme replacement therapy on cardiac involvement in Japanese Fabry patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. 124, 143–151 (2018).

Weidemann, F. et al. Long-term effects of enzyme replacement therapy on Fabry cardiomyopathy: evidence for a better outcome with early treatment. Circulation 119, 524–529 (2009).

Germain, D. P. et al. Ten-year outcome of enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase beta in patients with Fabry disease. J. Med. Genet. 52, 353–358 (2015).

Germain, D. P. et al. Treatment of Fabry’s disease with the pharmacologic chaperone migalastat. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 545–555 (2016).

Germain, D. P. & Linhart, A. Pegunigalsidase alfa: a novel, pegylated recombinant alpha-galactosidase enzyme for the treatment of Fabry disease. Front. Genet. 15, 1395287 (2024).

Ashe, K. M. et al. Efficacy of enzyme and substrate reduction therapy with a novel antagonist of glucosylceramide synthase for Fabry disease. Mol. Med. 21, 389–399 (2015).

Simonetta, I. et al. Genetics and gene therapy of Anderson-Fabry disease. Curr. Gene Ther. 18, 96–106 (2018).

Lee, C. J., Fan, X., Guo, X. & Medin, J. A. Promoter-specific lentivectors for long-term, cardiac-directed therapy of Fabry disease. J. Cardiol. 57, 115–122 (2011).

Shen, J. S. et al. Mannose receptor-mediated delivery of moss-made alpha-galactosidase A efficiently corrects enzyme deficiency in Fabry mice. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 39, 293–303 (2016).

Gal, A., Beck, M., Hoppner, W. & Germain, D. P. Clinical utility gene card for: Fabry disease—update 2016. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25, e1–e3 (2017).

Germain, D. et al. Fluorescence-assisted mismatch analysis (FAMA) for exhaustive screening of the alpha-galactosidase A gene and detection of carriers in Fabry disease. Hum. Genet. 98, 719–726 (1996).

Tuttolomondo, A. et al. Inter-familial and intra-familial phenotypic variability in three Sicilian families with Anderson-Fabry disease. Oncotarget 8, 61415–61424 (2017).

Elleder, M. et al. Cardiocyte storage and hypertrophy as a sole manifestation of Fabry’s disease. Report on a case simulating hypertrophic non-obstructive cardiomyopathy. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 417, 449–455 (1990).

Germain, D. P. et al. Phenotypic characteristics of the p.Asn215Ser (p.N215S) GLA mutation in male and female patients with Fabry disease: a multicenter Fabry Registry study. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 6, 492–503 (2018).

Rozenfeld, P. & Feriozzi, S. Contribution of inflammatory pathways to Fabry disease pathogenesis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 122, 19–27 (2017).

Yogasundaram, H. et al. Elevated inflammatory plasma biomarkers in patients with Fabry disease: a critical link to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e009098 (2018).

Moon, J. C. et al. Gadolinium enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in Anderson-Fabry disease. Evidence for a disease specific abnormality of the myocardial interstitium. Eur. Heart J. 24, 2151–2155 (2003).

Putko, B. N. et al. Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy: prevalence, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Heart Fail. Rev. 20, 179–191 (2015).

Sheppard, M. N. et al. A detailed pathologic examination of heart tissue from three older patients with Anderson-Fabry disease on enzyme replacement therapy. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 19, 293–301 (2010).

Yogasundaram, H. et al. Burden of valvular heart disease in patients with Fabry disease. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 35, 236–238 (2022).

Nair, V., Belanger, E. C. & Veinot, J. P. Lysosomal storage disorders affecting the heart: a review. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 39, 12–24 (2019).

Demuth, K. & Germain, D. P. Endothelial markers and homocysteine in patients with classic Fabry disease. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 91, 57–61 (2002).

Hsu, M. J. et al. Identification of lysosomal and extralysosomal globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) accumulations before the occurrence of typical pathological changes in the endomyocardial biopsies of Fabry disease patients. Genet. Med. 21, 224–232 (2019).

Boutouyrie, P. et al. Non-invasive evaluation of arterial involvement in patients affected with Fabry disease. J. Med. Genet. 38, 629–631 (2001).

Boutouyrie, P. et al. Arterial remodelling in Fabry disease. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 91, 62–66 (2002).

Knott, K. D. et al. Quantitative myocardial perfusion in Fabry disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 12, e008872 (2019).

Namdar, M. Electrocardiographic changes and arrhythmia in Fabry disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 3, 7 (2016).

Zivna, M. et al. Misprocessing of alpha-galactosidase A, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and the unfolded protein response. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.0000000535 (2024).

Scriver, C. R. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease 7th edn (McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division, 1995).

Inoue, T. et al. Newborn screening for Fabry disease in Japan: prevalence and genotypes of Fabry disease in a pilot study. J. Hum. Genet. 58, 548–552 (2013).

Mechtler, T. P. et al. Neonatal screening for lysosomal storage disorders: feasibility and incidence from a nationwide study in Austria. Lancet 379, 335–341 (2012).

Spada, M. et al. High incidence of later-onset Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79, 31–40 (2006).

Lin, H. Y. et al. High incidence of the cardiac variant of Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening in the Taiwan Chinese population. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2, 450–456 (2009).

Gragnaniello, V. et al. Newborn screening for Fabry disease in Northeastern Italy: results of five years of experience. Biomolecules 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11070951 (2021).

Monda, E. et al. Impact of GLA variant classification on the estimated prevalence of Fabry disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of screening studies. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 16, e004252 (2023).

Sadasivan, C. et al. Screening for Fabry disease in patients with unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy. PLoS ONE 15, e0239675 (2020).

Sachdev, B. et al. Prevalence of Anderson-Fabry disease in male patients with late onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 105, 1407–1411 (2002).

Nakao, S. et al. An atypical variant of Fabry’s disease in men with left ventricular hypertrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 333, 288–293 (1995).

Elliott, P. et al. Prevalence of Anderson-Fabry disease in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the European Anderson-Fabry disease survey. Heart 97, 1957–1960 (2011).

van der Tol, L. et al. A systematic review on screening for Fabry disease: prevalence of individuals with genetic variants of unknown significance. J. Med. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101857 (2013).

Havndrup, O. et al. Fabry disease mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genetic screening needed for establishing the diagnosis in women. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 12, 535–540 (2010).

Linhart, A. et al. Cardiac manifestations of Anderson-Fabry disease: results from the international Fabry outcome survey. Eur. Heart J. 28, 1228–1235 (2007).

Pieroni, M. et al. Cardiac involvement in Fabry disease: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 922–936 (2021).

Ashton-Prolla, P. et al. Fabry disease: twenty-two novel mutations in the alpha-galactosidase A gene and genotype/phenotype correlations in severely and mildly affected hemizygotes and heterozygotes. J. Investig. Med.48, 227–235 (2000).

Germain, D. P. A new phenotype of Fabry disease with intermediate severity between the classical form and the cardiac variant. Contrib. Nephrol. 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1159/000060194 (2001).

Clarke, J. T. Narrative review: Fabry disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 146, 425–433 (2007).

Rao, D. A., Lakdawala, N. K., Miller, A. L. & Loscalzo, J. Clinical problem-solving. In the thick of it. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1732–1738 (2013).

Arbustini, E. et al. The MOGE(S) classification for a phenotype-genotype nomenclature of cardiomyopathy: endorsed by the World Heart Federation. Glob. Heart 8, 355–382 (2013).

Wilcox, W. R. et al. Females with Fabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol. Genet. Metab. 93, 112–128 (2008).

Tuttolomondo, A. et al. Neurological complications of Anderson-Fabry disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 6014–6030 (2013).

Grunfeld, J. P., Lidove, O., Joly, D. & Barbey, F. Renal disease in Fabry patients. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 24(Suppl 2), 71–74 (2001).

Branton, M., Schiffmann, R. & Kopp, J. B. Natural history and treatment of renal involvement in Fabry disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13(Suppl 2), S139–S143 (2002).

Hoffmann, B. et al. Nature and prevalence of pain in Fabry disease and its response to enzyme replacement therapy-a retrospective analysis from the Fabry Outcome Survey. Clin. J. Pain. 23, 535–542 (2007).

Keshav, S. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Fabry disease. In Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS (eds Mehta, A., Beck, M., & Sunder-Plassmann, G.) (2006)..

Orteu, C. H. et al. Fabry disease and the skin: data from FOS, the Fabry outcome survey. Br. J. Dermatol. 157, 331–337 (2007).

Samiy, N. Ocular features of Fabry disease: diagnosis of a treatable life-threatening disorder. Surv. Ophthalmol. 53, 416–423 (2008).

Arends, M. et al. Characterization of classical and nonclassical Fabry disease: a multicenter study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 1631–1641 (2017).

Mignani, R. et al. Dialysis and transplantation in Fabry disease: indications for enzyme replacement therapy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 5, 379–385 (2010).

Hagege, A. et al. Fabry disease in cardiology practice: literature review and expert point of view. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 112, 278–287 (2019).

Linhart, A. et al. An expert consensus document on the management of cardiovascular manifestations of Fabry disease. Eur. J. Heart Fail 22, 1076–1096 (2020).

Shanks, M. et al. Systolic and diastolic function assessment in fabry disease patients using speckle-tracking imaging and comparison with conventional echocardiographic measurements. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 26, 1407–1414 (2013).

Kramer, J. et al. Relation of burden of myocardial fibrosis to malignant ventricular arrhythmias and outcomes in Fabry disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 114, 895–900 (2014).

Borlaug, B. A., Sharma, K., Shah, S. J. & Ho, J. E. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: JACC scientific statement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 81, 1810–1834 (2023).

Patel, M. R. et al. Cardiovascular events in patients with fabry disease natural history data from the fabry registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57, 1093–1099 (2011).

Wu, J. C. et al. Cardiovascular manifestations of Fabry disease: relationships between left ventricular hypertrophy, disease severity, and alpha-galactosidase A activity. Eur. Heart J. 31, 1088–1097 (2010).

Chimenti, C. et al. Prevalence of Fabry disease in female patients with late-onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 110, 1047–1053 (2004).

Germain, D. P. et al. Analysis of left ventricular mass in untreated men and in men treated with agalsidase-beta: data from the Fabry Registry. Genet. Med. 15, 958–965 (2013).

Thompson, R. B. et al. T(1) mapping with cardiovascular MRI is highly sensitive for Fabry disease independent of hypertrophy and sex. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 6, 637–645 (2013).

Kampmann, C. et al. Cardiac manifestations of Anderson-Fabry disease in heterozygous females. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 40, 1668–1674 (2002).

Linhart, A. et al. New insights in cardiac structural changes in patients with Fabry’s disease. Am. Heart J. 139, 1101–1108 (2000).

Flegal, K. M., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K. & Ogden, C. L. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA 307, 491–497 (2012).

Chow, C. K. et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA 310, 959–968 (2013).

Kampmann, C. et al. Onset and progression of the Anderson-Fabry disease related cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 130, 367–373 (2008).

Linhart, A. & Elliott, P. M. The heart in Anderson-Fabry disease and other lysosomal storage disorders. Heart 93, 528–535 (2007).

Linhart, A. The heart in Fabry disease. In Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS (eds Mehta, A., Beck, M. & Sunder-Plassmann, G.) (Oxford PharmaGenesis, 2006).

Aerts, J. M. et al. Elevated globotriaosylsphingosine is a hallmark of Fabry disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2812–2817 (2008).

Thurberg, B. L. et al. Cardiac microvascular pathology in Fabry disease: evaluation of endomyocardial biopsies before and after enzyme replacement therapy. Circulation 119, 2561–2567 (2009).

Chimenti, C. et al. Cardiac and skeletal myopathy in Fabry disease: a clinicopathologic correlative study. Hum. Pathol. 43, 1444–1452 (2012).

Rombach, S. M. et al. Vascular aspects of Fabry disease in relation to clinical manifestations and elevations in plasma globotriaosylsphingosine. Hypertension 60, 998–1005 (2012).

Dormond, O. & Barbey, F. Thoracic aortic dilation/aneurysm in Fabry disease. Am. J. Med. 126, e23 (2013).

Chimenti, C. et al. Angina in fabry disease reflects coronary small vessel disease. Circ. Heart Fail. 1, 161–169 (2008).

Goldman, M. E., Cantor, R., Schwartz, M. F., Baker, M. & Desnick, R. J. Echocardiographic abnormalities and disease severity in Fabry’s disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 7, 1157–1161 (1986).

Bass, J. L., Shrivastava, S., Grabowski, G. A., Desnick, R. J. & Moller, J. H. The M-mode echocardiogram in Fabry’s disease. Am. Heart J. 100, 807–812 (1980).

Barbey, F. et al. Aortic remodelling in Fabry disease. Eur. Heart J. 31, 347–353 (2010).

Shah, J. S. et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of cardiac arrhythmia in Anderson-Fabry disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 96, 842–846 (2005).

Azevedo, O. et al. Natural history of the late-onset phenotype of Fabry disease due to the p.F113L mutation. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 22, 100565 (2020).

Linhart, A. et al. Cardiac manifestations in Fabry disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 24, 75–83 (2001).

Eng, C. M. et al. Fabry disease: baseline medical characteristics of a cohort of 1765 males and females in the Fabry Registry. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 30, 184–192 (2007).

Umer, M., Motwani, M., Jefferies, J. L., Nagueh, S. F. & Kalra, D. K. Cardiac involvement in Fabry disease and the role of multimodality imaging in diagnosis and disease monitoring. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 48, 101439 (2023).

Arbelo, E. et al. [2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies]. G Ital. Cardiol.24, e1–e127 (2023).

Leung, S. P. et al. The Asian Fabry Cardiomyopathy High-Risk Screening Study 2 (ASIAN-FAME-2): Prevalence of Fabry Disease in Patients with Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. J. Clin. Med. 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133896 (2024).

Morita, H. et al. Single-gene mutations and increased left ventricular wall thickness in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 113, 2697–2705 (2006).

Maron, M. S. et al. Identification of Fabry disease in a tertiary referral cohort of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Med. 131, 200 e201–200 e208 (2018).

Germain, D. P. et al. Challenging the traditional approach for interpreting genetic variants: Lessons from Fabry disease. Clin. Genet. 101, 390–402 (2022).

Houge, G., Langeveld, M. & Oliveira, J. P. GLA insufficiency should not be called Fabry disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01657-0 (2024).

Yasuda, M. et al. Fabry disease: characterization of alpha-galactosidase A double mutations and the D313Y plasma enzyme pseudodeficiency allele. Hum. Mutat. 22, 486–492 (2003).

Pieroni, M. et al. Early detection of Fabry cardiomyopathy by tissue Doppler imaging. Circulation 107, 1978–1984 (2003).

Toro, R. et al. Clinical usefulness of tissue Doppler imaging in predicting preclinical Fabry cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 132, 38–44 (2009).

Weidemann, F. et al. The variation of morphological and functional cardiac manifestation in Fabry disease: potential implications for the time course of the disease. Eur. Heart J. 26, 1221–1227 (2005).

Soullier, C. et al. Exercise response in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: blunted left ventricular deformational and twisting reserve with altered systolic-diastolic coupling. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 5, 324–332 (2012).

Koeppe, S. et al. MR-based analysis of regional cardiac function in relation to cellular integrity in Fabry disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 160, 53–58 (2012).

Messalli, G. et al. Role of cardiac MRI in evaluating patients with Anderson-Fabry disease: assessing cardiac effects of long-term enzyme replacement therapy. Radio. Med. 117, 19–28 (2012).

Niemann, M. et al. Differences in Fabry cardiomyopathy between female and male patients. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 4, 592–601 (2011).

Mewton, N., Liu, C. Y., Croisille, P., Bluemke, D. & Lima, J. A. Assessment of myocardial fibrosis with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57, 891–903 (2011).

Sado, D. M. et al. Identification and assessment of Anderson-Fabry disease by cardiovascular magnetic resonance noncontrast myocardial T1 mapping. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 6, 392–398 (2013).

Jefferies, J. L. et al. A new approach to identifying patients with elevated risk for Fabry disease using a machine learning algorithm. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 16, 518 (2021).

Abbasi, M. A. et al. Artificial intelligence electrocardiography for the evaluation of cardiac involvement in Fabry disease. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 50, 102877 (2025).

Chen, W. W. et al. A deep learning approach to classify Fabry cardiomyopathy from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using cine imaging on cardiac magnetic resonance. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2024, 6114826 (2024).

Hindieh, W. et al. Discrepant measurements of maximal left ventricular wall thickness between cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 10, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.006309 (2017).

Augusto, J. B. et al. Diagnosis and risk stratification in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using machine learning wall thickness measurement: a comparison with human test-retest performance. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e20–e28 (2021).

Eng, C. M. et al. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human alpha-galactosidase A replacement therapy in Fabry’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 9–16 (2001).

Schiffmann, R. et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 285, 2743–2749 (2001).

Alfadhel, M. & Sirrs, S. Enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease: some answers but more questions. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 7, 69–82 (2011).

Beer, M. et al. Impact of enzyme replacement therapy on cardiac morphology and function and late enhancement in Fabry’s cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 97, 1515–1518 (2006).

Hasegawa, H. et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Transition from left ventricular hypertrophy to massive fibrosis in the cardiac variant of Fabry disease. Circulation 113, e720–e721 (2006).

Mehta, A. et al. Enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase alfa in patients with Fabry’s disease: an analysis of registry data. Lancet 374, 1986–1996 (2009).

Feriozzi, S., Chimenti, C. & Reisin, R. C. Updated evaluation of agalsidase alfa enzyme replacement therapy for patients with Fabry disease: insights from real-world data. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 18, 1083–1101 (2024).

Hughes, D. A. et al. Effects of enzyme replacement therapy on the cardiomyopathy of Anderson-Fabry disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of agalsidase alfa. Heart 94, 153–158 (2008).

El Dib, R. et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for Anderson-Fabry disease: a complementary overview of a Cochrane publication through a linear regression and a pooled analysis of proportions from cohort studies. PLoS ONE 12, e0173358 (2017).

Pieroni, M. et al. Progression of Fabry cardiomyopathy despite enzyme replacement therapy. Circulation 128, 1687–1688 (2013).

Hersher, R. Small biotechs raring to cash in on the orphan disease market. Nat. Med. 18, 330–331 (2012).

Murray, G. J., Anver, M. R., Kennedy, M. A., Quirk, J. M. & Schiffmann, R. Cellular and tissue distribution of intravenously administered agalsidase alfa. Mol. Genet. Metab. 90, 307–312 (2007).

Braun, F. et al. Enzyme replacement therapy clears Gb3 deposits from a podocyte cell culture model of Fabry disease but fails to restore altered cellular signaling. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 52, 1139–1150 (2019).

Elsaid, H. O. A. et al. Gene expression analysis in gla-mutant zebrafish reveals enhanced Ca(2+) signaling similar to Fabry disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010358 (2022).

Guce, A. I., Clark, N. E., Rogich, J. J. & Garman, S. C. The molecular basis of pharmacological chaperoning in human alpha-galactosidase. Chem. Biol. 18, 1521–1526 (2011).

Suzuki, Y. Chaperone therapy update: Fabry disease, GM1-gangliosidosis and Gaucher disease. Brain Dev. 35, 515–523 (2013).

SPC. Available online: European Medicines Agency. Migalastat. Summary of product characteristics (accessed on 30 September 2024), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/galafold-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

Hughes, D. A. et al. Oral pharmacological chaperone migalastat compared with enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: 18-month results from the randomised phase III ATTRACT study. J. Med. Genet. 54, 288–296 (2017).

Feldt-Rasmussen, U. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of migalastat treatment in Fabry disease: 30-month results from the open-label extension of the randomized, phase 3 ATTRACT study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 131, 219–228 (2020).

Lenders, M. et al. Treatment of Fabry disease management with migalastat-outcome from a prospective 24 months observational multicenter study (FAMOUS). Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 8, 272–281 (2022).

Lenders, M. et al. Treatment of Fabry’s disease with migalastat: outcome from a prospective observational multicenter study (FAMOUS). Clin. Pharm. Ther. 108, 326–337 (2020).

Muntze, J. et al. Oral chaperone therapy migalastat for treating fabry disease: enzymatic response and serum biomarker changes after 1 year. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 105, 1224–1233 (2019).

Muntze, J. et al. Patient reported quality of life and medication adherence in Fabry disease patients treated with migalastat: a prospective, multicenter study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 138, 106981 (2023).

Muntze, J., Salinger, T., Gensler, D., Wanner, C. & Nordbeck, P. Treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by cardiospecific variants of Fabry disease with chaperone therapy. Eur. Heart J. 39, 1861–1862 (2018).

Riccio, E. et al. Switch from enzyme replacement therapy to oral chaperone migalastat for treating fabry disease: real-life data. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 28, 1662–1668 (2020).

Deegan, P. B. et al. Venglustat, an orally administered glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor: assessment over 3 years in adult males with classic Fabry disease in an open-label phase 2 study and its extension study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 138, 106963 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to writing the manuscript and reviewing it during subsequent iterations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dougherty, S., Germain, D.P., Oudit, G.Y. et al. Cardiac manifestations of Fabry disease. npj Cardiovasc Health 2, 40 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-025-00058-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-025-00058-6