Abstract

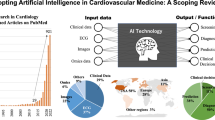

Traditional cardiovascular care relies on episodic, resource-intensive evaluations. Consumer wearable and portable devices, combined with artificial intelligence (AI), offer a scalable, low-cost alternative. These devices can enhance care with high-fidelity cardiovascular data captured outside traditional care settings, with AI further increasing their value. This review explores how AI-enhanced digital health tools can transform cardiovascular care, improving early detection, personalized risk assessment, and proactive management, particularly in resource-constrained settings, while bridging gaps in traditional care models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional cardiovascular care pathways have relied on episodic, resource-intensive evaluations led by expert clinicians in healthcare settings1. While advances in cardiovascular diagnostics have enabled improved detection and prognostication of disease in such care settings, this strategy has low accessibility and limited ability to scale to communities2,3,4. Such challenges are compounded in resource-constrained settings where routine screening and diagnosis are broadly limited by access to traditional preventive care5. However, AI-enabled digital health tools are set to transform cardiovascular care pathways through scalable, low-cost strategies that can improve the timely detection, prevention, and management of cardiovascular disorders directly in the communities6,7. Two synergistic developments have the potential to substantially alter the landscape of cardiovascular care.

First, a broad range of low-cost and highly scalable digital health tools now have sensors that enable high-fidelity and high-quality cardiovascular data to be captured directly in the communities on compact and mobile devices (portable) and devices that are worn by individuals (wearable)8,9,10,11. For instance, while previously electrocardiograms (ECG) and cardiac imaging were largely restricted to healthcare settings, ECGs can now be obtained on handheld and wrist-worn devices12,13,14. Similarly, the heart can be visualized by a point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) plugged directly into a smartphone15,16. Therefore, these technologies have the potential to enable accurate, scalable, and accessible cardiovascular screening.

Second, while the acquisition of health data in the communities can broaden access, the reliance on the limited number of experts to interpret these studies restricts their potential scalability17. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) can infer disease patterns from a range of cardiovascular diagnostic modalities1,18. However, most of these applications have been limited to testing in clinical settings. The development of AI tools specifically designed to expand inference from portable and wearable devices can bring a digital health-enabled revolution in community cardiovascular care9,19.

In this review we have addressed a broad range of novel methods, including machine learning, deep learning, and large language models (LLMs), along with their applications to signal and imaging processing. We explore the literature on the transformative potential of AI-enhanced digital health devices in cardiovascular screening, prediction, and monitoring in communities across care settings. The review contrasts traditional and AI-enabled care pathways and highlights how these advances can drive equitable access to preventive care, improve health outcomes, and reduce the global burden of cardiovascular diseases.

Traditional approaches to cardiovascular care

Community-based cardiovascular care currently relies on reactive, episodic models of healthcare delivery, driven by healthcare encounters primarily initiated by the patients during scheduled routine visits or when symptoms appear20. In this section, we describe the current approach for screening, diagnosing, and monitoring these diseases in the community.

Currently, the screening for cardiovascular diseases primarily focuses on the collection of clinical and behavioral data to estimate the longer-term individual risk for major cardiovascular events21,22,23. Screening often includes a review of family history and assessment of risk factors to determine high-risk populations that may require advanced evaluations for a better assessment of an individual’s cardiovascular health24,25. Sporadic community-based screening programs with large-scale data collection complement these efforts and provide the opportunity to identify individuals at elevated risk who may benefit from early intervention25. While effective for identifying high-risk individuals and recommending lifestyle modifications, the current approach for cardiovascular screening often misses the opportunity to capture individuals in the early stages of disease or those with subclinical disease26.

After identifying those at risk, the actual diagnostic workflow depends on advanced laboratory and imaging studies to further evaluate cardiac structure and function26. Diagnosis is often guided by standardized clinical protocols that depend on collecting a series of healthcare parameters for a systematic evaluation of patient symptoms and risk factors25,27, which are particularly challenging in low-resource settings28. Additionally, conventional diagnosis strategies often depend on laboratory testing and expert interpretation of test results, which require infrastructure and skilled personnel, making them less accessible29.

In the context of cardiovascular disease monitoring, traditional models often heavily rely on the patient to track their symptoms, maintain the recommended changes in lifestyle, and comply with risk-reducing medications. It is also the individual’s responsibility to seek medical attention when necessary, with most patients limited by resources, an awareness of their health status, or even motivation to allow such an approach to be broadly successful30,31.

In the following sections, we present an overview of emerging data modalities being collected from consumer-facing devices and explore how AI can enable these data streams to advance cardiovascular care. Figure 1 contrasts the traditional and the AI-enabled paradigms of community cardiovascular care.

AI-enhanced approaches to cardiovascular care

The rapid proliferation of wearable and portable health devices has led to an unprecedented increase in health-related data generated outside traditional healthcare settings8,9. Devices that are worn by individuals, such as smartwatches, rings, wristbands, shirts, and eyeglasses (wearables), and others that capture health information by being in the vicinity of individuals, such as smartphones, smart-scales, and others (nearables) (Fig. 2) can continuously collect physiological and behavioral data from individuals in the communities32,33.

Emerging data sources from consumer devices

Advances in sensor technology integrated into several consumer-facing devices have enabled the collection of vast amounts of data with significant potential for applications in cardiovascular care8,9. These data sources are largely continuously collected without requiring user interaction, but there are also new actively collected data streams that provide targeted in-depth snapshots of health status at specific time points. A summary of the sensors available in consumer-facing devices is presented in Fig. 27,34.

Even among the continuously collected data from these sensors, there is a vast range of data elements that capture different aspects of cardiovascular health. For example, in most smartwatches and fitness trackers, optical sensors using light-based technologies, like photoplethysmography (PPG), continuously measure blood volume changes, enabling the estimation of heart rate, heart rate variability, and blood oxygen saturation (SpO2)35,36. Accelerometers and gyroscopes detect motion, posture, and physical activity. They are widely used to monitor step count, activity and its intensity, and critical events, such as falls. Thermal sensors can monitor changes in skin temperature. Galvanic skin response sensors, also known as electrodermal activity sensors, measure changes in skin conductivity, which are influenced by sweat gland activity and, indirectly, by autonomic nervous system activity37,38. Pressure sensor-based ballistocardiography (BCG) can measure the mechanical activity of the heart by detecting the body’s subtle movements resulting from the cardiac ejection of blood39,40. In wearable devices, BCG sensors capture these micro-movements in wrist-worn devices41. Many devices also have a barometer that measures atmospheric pressure and altitude. In wearable devices, barometers can track changes in elevation and pressure, providing insights into the intensity of physical activity, such as climbing stairs or hiking, as well as environmental conditions like altitude and pressure41,42.

Consumer-facing devices are now increasingly equipped with other dedicated sensors for specific data streams that require active user engagement43. These sensors provide high-value snapshots of cardiovascular health at specific time points. For example, the cardiac electrical sensor, available on most advanced smartwatches, provides a clinical grade 1-lead ECG on the wrist44,45. Wearable cuffs and cuffless devices can also combine data from optical and mechanical sensors to estimate blood pressure on demand32. While episodic, these measurements provide valuable insights into the users’ health.

Cardiovascular applications of new wearable-derived data

These new data modalities provide opportunities for many cardiovascular applications. For example, the combination of data from different sensors, like accelerometer data combined with PPG and temperature sensors, can provide estimates of sleep duration, stages, and quality46,47. Along with heart rate and SpO2 data extracted from PPG sensors, these devices can inform care for conditions like heart failure (HF) and sleep apnea9,46. BCG sensors can further enhance sleep monitoring by detecting subtle vibrations in the chest and abdomen caused by cardiac and respiratory activities. This enables continuous sleep monitoring while extracting a range of key physiological information to better assess sleep quality39. Irregular sleep patterns, identified through these data, have been associated with cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension and a range of atrial arrhythmias47.

Accelerometer and gyroscope data enable monitoring patterns of physical activity, which provide an additional axis for cardiovascular health. Combined with barometer information on altitude and pressure, these can additionally provide insights into the intensity of physical activity as well as be useful in tracking physiological responses to changes in altitude48, symptoms such as chest pain or shortness of breath during exertion, and a decrease in exercise tolerance11. Thermal and electrodermal sensors contribute to understanding stress-induced cardiovascular responses, such as transient elevations in heart rate and blood pressure, by providing data on stress-related autonomic nervous system activation49,50.

These applications broaden the more commonly recognized cardiovascular applications of dedicated cardiac sensors available on wearable devices. The most prominent example is the single-lead ECGs that identify irregular heart rhythms like atrial fibrillation (AF)13,51. These wearable-collected ECGs have been shown to facilitate long-term monitoring of cardiac rhythms outside clinical settings, capturing transient or asymptomatic events that might be missed during brief in-office assessments. AI applications to these data allow for screening and diagnosis of various cardiovascular conditions, including AF, stroke, cardiac arrest, HF, and even subclinical cardiomyopathies52,53,54, which are discussed in further detail in the following sections. Beyond traditional wearable devices, wearable cuff-based and cuffless devices that measure blood pressure and emerging optical sensor technologies that measure blood glucose non-invasively show promise in managing major cardiovascular risk factors55,56.

While these sensors generate high-quality health-related data, AI can further enhance their value and can enable a new frontier of cardiovascular care in the community. Combining diverse sensor data with AI can allow early detection of several unique cardiovascular risk markers, facilitate personalization of care, and further allow low-touch monitoring directly in the communities. Some recent clinical trials have explored how AI-enabled wearables can support therapy monitoring and clinical decision-making in real-world populations57,58,59. For example, RATE-AF was a randomized clinical trial (RCT) that used a consumer-grade wrist-worn wearable device in older adults with AF and HF to monitor over 140 million heart rate data points and over 23 million physical activity data points over a 20-week period. By processing the wearable-derived data with a deep learning model, the authors demonstrated that the functional status (defined by the New York Heart Association class) could be predicted with a performance equivalent to standard clinical assessments such as ECG and the 6-min walk test60. In another RCT conducted under both in-clinic and community conditions with patients with type 2 diabetes, an automated insulin delivery system enhanced by an AI-based predictive control algorithm that continuously integrated heart rate and accelerometry data from a smartwatch, reduced glucose variability and minimized hypoglycemic events without requiring user input during physical activity. The findings underscore how consumer-grade wearable devices, coupled with AI, can support personalized and adaptive care delivery beyond traditional healthcare settings59.

AI-enabled utilization of wearable/portable device data in cardiovascular care

While new health data that can be acquired on wearable and portable devices offers novel avenues for cardiovascular care, achieving the full potential of these innovations requires their effective integration into healthcare systems61,62. AI applications can address challenges with managing the volume and quality of these data by enabling their optimization into usable metrics, filling gaps in incomplete datasets, and identifying critical patterns within these data62. The sections below explore specific AI use cases, including strategies for enabling data interoperability and integration into clinical workflows.

AI-assisted interoperability of wearables with EHR

Interoperability refers to the ability of different systems, devices, and software to communicate and exchange information. In the context of wearable devices, diverse systems need to exchange and use the data available from these devices effectively63,64. A key barrier to interoperability in these data is the challenge of achieving both syntactic and semantic compatibility65. Syntactic interoperability ensures that data can be exchanged in standardized formats, while semantic interoperability ensures that the meaning of the data is preserved across different systems. Creating standardized approaches for these two key components ensures consistency in how data are captured, stored, and interpreted57. The growing number of proprietary wearable devices in clinical and consumer settings has introduced considerable variation in how physiological signals are captured and reported. A major challenge lies in the inconsistency of measurement definitions and the lack of calibration standards across manufacturers, which limits the interoperability of data. Without a uniform approach to how metrics like heart rate or activity are measured, comparing outputs across platforms or integrating them into unified datasets remains problematic. Differences in the timing and frequency of data collection pose an additional barrier. Devices may sample at irregular intervals or use context-dependent triggers, making temporal alignment across sources difficult, particularly in longitudinal monitoring or real-time clinical decision-making. The American Heart Association (AHA) and other professional organizations have called for coordinated efforts to develop validation frameworks and common data standards that can serve as the basis for scalable clinical integration. In the absence of achieving standardization at source, there is a potential role for AI to simplify the complex task of integrating data from multiple sources by identifying relationships between disparate datasets and merging them into a unified, consistent format57.

Semantic compatibility ensures that the meaning of data is preserved and understood uniformly across systems66. This concept is pivotal in enabling seamless integration of wearable device data into clinical workflows. For example, semantic interoperability requires the inference from these data to be mapped to clinically meaningful categories, which could be further standardized via vocabularies and terminologies to ensure that data captured by wearables can be interpreted consistently, regardless of the system or application using the data67,68. Achieving semantic compatibility involves not only aligning terminologies but also structuring data so that its clinical relevance is preserved during transmission and use61.

Concrete strategies to support syntactic and semantic interoperability include the adoption of standardized data formats such as HL7 Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), which provide structured frameworks for exchanging health data across diverse systems69. Moreover, other innovations in natural language processing, especially the emergence of large language models, can enable the alignment of ontologies and can help map heterogeneous data elements into unified, clinically meaningful representations70.

AI-assisted integration of wearable data into clinical workflows

Integrating wearable-derived data into clinical workflows is essential for their effective application in healthcare71,72. Clinicians across the world operate under significant constraints on their time, and the addition of new data streams risks overwhelming them with additional tasks, reducing efficiency, and potentially diverting attention from direct patient care. To be clinically valuable, wearable-derived data must be seamlessly incorporated into existing workflows without introducing new steps or requiring additional effort73.

Integrating these new data streams into existing workflows requires first synthesizing these large-volume, continuously collected data into interpretable summaries74. AI-driven data summarization can occur at two levels: within the healthcare system or through edge computing directly on the device75. Edge computing enables data analysis to be performed locally, reducing the need to transmit sensitive health information outside encrypted devices. This approach enhances data privacy, while also enabling more immediate feedback for critical scenarios76. By alleviating network congestion and reducing latency, edge computing also improves the responsiveness and reliability of AI-driven healthcare systems. Novel AI tools can streamline data integration into clinical workflows by automating repetitive tasks, such as data entry and report generation64. For example, AI tools can be applied to create clinically meaningful synthesis across multiple metrics77. A clinical scenario that conceptualizes such a setting is presented in Fig. 3. Meaningful integration must go beyond technical capability. To avoid overwhelming clinicians, AI systems should incorporate prioritization algorithms that triage information and surface only the most clinically relevant findings. Additionally, clinician-centered dashboards designed with input from end users can help translate raw data into intuitive, actionable insights that fit into existing decision-making processes.

Despite promising technological advances, several real-world considerations can limit the implementation of AI-enabled wearable solutions to improve cardiovascular care. A major challenge is the sustained use of these devices by patients, especially those that require daily engagement or manual data input78. Moreover, there are financial considerations that would limit adoption. Reimbursement pathways for both devices and AI algorithms are still evolving and often lack clarity, particularly in settings outside traditional fee-for-service models8. Additionally, integrating continuous data streams into clinical workflows can risk overwhelming providers unless thoughtfully managed through prioritization algorithms and an actionable interface. To support adoption, user-centered design principles rooted in human-factors engineering are essential. Wearable devices must be comfortable, unobtrusive, and intuitive while minimizing cognitive load for both users and clinicians79.

Considerations for deploying AI-enabled devices in cardiovascular care

Advances in AI have recently been applied to data generated by community health devices to improve many facets of cardiovascular care1,10. However, the translation of their outputs into clinical practice requires addressing a number of foundational challenges. In this section, we examine the key technical, clinical, and regulatory considerations involved in the development and deployment of AI-enabled cardiovascular solutions (Fig. 4). We discuss the key considerations for developing and leveraging these technologies in care, the major cardiovascular AI applications for these devices on the horizon, and provide a framework for novel care pathways that leverage these tools effectively.

Technical considerations for developing clinical AI solutions for wearable devices

The development of AI for these digital health devices requires addressing six critical challenges.

Lack of large wearable repositories for model development

While 1.1 billion individuals reportedly use a wearable device worldwide80, generating 28 petabytes of data each year81, the data are largely fragmented and unavailable for disease discovery and optimizing care. Only a few studies have incorporated wearable device data into their frameworks. Among large discovery cohort studies, the UK Biobank, has accelerometer data from approximately 50,000 participants82,83. These represented two weeks of data from participants wearing these devices relatively continuously. However, this differs from the real world, where data collection spans more extended periods but with lower day-to-day use of the devices. Hence, the available data consist of more extended periods of sparse data, posing challenges for direct translation of inference on healthcare outcomes. Another cohort, the All of Us Research Program (AoURP) includes wearable device data from 13,000 participants, all sourced from a single device type (Fitbit)84. AoURP wearable data are not provided in a granular format but are instead aggregated into summary metrics such as daily step counts and sleep estimates. While the data have been used for examining outcome associations of wearable-derived metrics47,85, the lack of detailed, continuous data limits the potential for in-depth analysis and algorithm development.

Clinical correlates for wearable device data are often limited

A related but independent consideration for the development of AI from wearable devices is how well device-derived data are paired with validated markers of cardiovascular disorders and associated clinical outcomes. The distinct consideration for this element is essential because establishing participant-driven networks to create large repositories of wearable data is useful only if these data can be paired with corresponding clinical information for these patients. This contrasts the AI and cardiovascular innovations developed directly for healthcare data streams, where the vast available clinical correlates data have spurred across several domains1,7,86,87. Therefore, while data in health system EHRs contain the requisite clinical information on a vast number of patients, the lack of integration of data from their patients who use wearable devices precludes the effective use of these data. Certain emerging studies are addressing these challenges by systematically collecting wearable data88,89.

Quality of available data relative to traditional clinical data streams

The quality of data derived from wearable and portable devices differs significantly from traditional clinical data streams. These differences, influenced by the type of device, patterns of use, and quality of acquisition, have important implications for using such device-derived data in clinical care. Consumer devices vary in the accuracy of their sensors, how data are structured, and how they are outputted to the user. In that context, data sparsity is a common challenge arising from a combination of users inconsistently wearing these devices and their disengagement from continued use. For example, users may wear fitness trackers sporadically or remove smartwatches for swimming, charging, or sleeping, leading to gaps in continuous monitoring. In addition to data sparsity, wearable data are often affected by unwanted or irrelevant variations captured by the sensors that interfere with the accurate measurement of the intended signal90. Wearable ECG data is particularly prone to noise, resulting from poor electrode-skin contact, movement artifacts, muscle contractions during recording, and external electrical interference91,92. The challenges of data quality extend to other important handheld devices for community cardiovascular diagnosis, such as POCUS. While these devices broaden access to cardiac imaging, the quality of data they acquire is determined by the skill and experience of operators acquiring these images. Therefore, those without adequate training may acquire images of low quality, introducing variability to the data. However, many of the gaps in data quality can be directly addressed by certain key safeguards, such as broader engagement with patients and encouraging optimal use, especially for those whom the wearable and portable devices are used for health monitoring93,94. Moreover, for ECG and POCUS acquisitions, novel AI innovations, described in the following section, are designed to improve both the quality of acquisition and the reliability of inference from these noisy data.

Epidemiological considerations for deployment in real-world settings

The deployment of AI-based diagnostic tools in real-world settings must account for the challenges posed by the low prevalence of diseases among healthier populations in the community95,96,97. In such scenarios, even fairly accurate models can yield a significant number of false positive results, potentially leading to unnecessary additional testing that diminishes their clinical utility, especially when used in low-resource settings98. For example, a hypothetical model with 95% sensitivity and 90% specificity is applied to a population with disease prevalences of 1%, 5%, and 10%. At 1% prevalence, fewer than 1 in 10 individuals identified as positive by the model actually have the disease, but with prevalences of 5% and 10%, this represents a third and half of the tested individuals, respectively. This example highlights how the clinical value of a model is context-dependent: in high-prevalence or diagnostic settings, PPV improves, and sensitivity may take precedence to avoid missed diagnoses, whereas in low-prevalence, population-level screening, NPV is high, but maximizing specificity becomes important to reduce false positives and unnecessary follow-up. This issue underscores the need for AI models with tailored thresholds that optimize both sensitivity and specificity. In public health programs where resource constraints are present, high specificity may be prioritized to limit false positives and downstream testing burden, while in diagnostic settings, particularly when the cost of missed disease is high, greater sensitivity may be preferred. Moreover, there is a role for sequentially deployed low-cost screening strategies to minimize false positives in low-prevalence settings99. One effective approach could involve integrating multimodal data for case enrichment and implementing sequential screening to detect a range of cardiac abnormalities using AI tools100. This structured approach not only reduces the impact of false positives but also prevents unnecessary strain on healthcare systems.

Integration into healthcare workflows

Wearable and portable health devices often operate within proprietary ecosystems, which can limit interoperability. Tools from different manufacturers typically use distinct software to process and analyze data, thereby creating data silos that are challenging to aggregate into a unified platform. This lack of interoperability limits the linkage of AI inferences across devices. For instance, an AI model trained to analyze ECG data from one wearable device may not be compatible with data from another device, even if the underlying physiological information is similar. Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are pivotal in enabling communication across devices, and their integration into healthcare data ecosystems. Moreover, they allow the deployment of AI models across devices by allowing sandboxes that aggregate data across devices. While API-based data access does not address all interoperability issues, it enables interfaces that facilitate real-time data exchange and inference that can be deployed across devices. Such an approach also allows healthcare organizations to integrate new technologies without significant system changes.

Regulatory and ethical strategies before deployment

The deployment of AI-powered diagnostic tools in healthcare requires consideration of evolving regulatory and ethical elements. The key questions include the reliability of these systems, their transparency and fairness, and the implemented processes to align with their actual use and how they are designed. Regulators typically consider wearable devices and consumer health technologies under their medical device framework. These regulations aim to ensure that devices marketed with claims of health monitoring or diagnostics meet specific safety and efficacy standards. Wearable devices that provide general wellness information may not fall under the same rigorous oversight unless intended for clinical use. Additionally, the FDA evaluates devices on their risk classification, considering factors such as the intended use and potential impact on patient safety. As AI-enabled wearables evolve toward continuous learning systems, regulatory frameworks must also adapt to this emerging framework. The FDA’s Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) guidelines, including its proposed Predetermined Change Control Plan, represent an essential step in allowing adaptive algorithms while ensuring safety and accountability. Another critical consideration is ensuring the appropriate use of the data generated by these new technologies. For instance, repurposing ECG outputs from consumer devices for off-label metrics beyond their approved indication may constitute a new intended use, which can subject the application to regulatory scrutiny under existing FDA pathways101.

These regulatory requirements set the stage for addressing ethical considerations such as ensuring patient autonomy, safeguarding data privacy, and promoting equitable use of AI-driven health applications. Variability in sensor performance across skin tones and disparities in digital literacy pose risks to equity and trust102. A critical question is whether these novel insights from patients’ devices should be shared directly with them so they can process and seek care based on their preferences. The alternative is that when information is derived from these emerging sources, which have built-in uncertainty, these are shared with clinicians who can ensure that these inferences are placed in the context of the overall clinical presentation, minimizing the risk of misinterpretation of information and psychological distress. This can be further compounded by the false positive results, which can cause distress without any potential beneficial effect for patients. However, to ensure the autonomy of the patients can be balanced with the safety of the application, the regulation of these health applications should be closely tied to their strategy for clinical use. Incorporating guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO) AI ethics and governance and other regional regulations can help mitigate these challenges through principles of transparency, inclusiveness, and algorithmic accountability103.

AI for enabling cardiovascular health insights from wearable and portable devices

The potential of deep learning to derive clinical insights from wearable and portable devices has manifested in a range of early applications. There are 3 domains that have observed the most sustained development.

AI applications for PPG-sensor-derived data

A range of statistical, machine learning, and deep learning algorithms have enabled valuable insights from beat-to-beat data acquired by PPG sensors. Early applications used combinations of input features like inter-beat intervals and heart rate variability in linear models to examine association with a series of cardiovascular diseases, offering interpretable insights from these data104. More advanced machine learning models have enhanced the inference from these data by detecting complex features and their interactions, with more robust assessment of disease associations. More recently, deep learning models, such as those leveraging convolutional neural networks, long short-term memory networks and transformer models, have provided further automation in parsing wearable data and identifying hierarchical representations of PPG data and their disease associations105,106.

For example, a model using heart rate data continuously collected with PPG sensors was useful for AF monitoring107. Another investigation used deep learning methods on raw PPG waveforms to distinguish AF from sinus rhythm. This approach, validated in patients undergoing cardioversion, outperformed conventional heart rate variability metrics and models based on heart rate alone108. The study underscores PPG’s utility in AF management, not only for screening large populations but also for tracking AF episodes and guiding rate control. While challenges like signal artifacts persist, the validation of PPG applications in real-world conditions highlights their role in advancing accessible, scalable cardiovascular monitoring solutions109.

AI for ECGs acquired on wearable and portable devices

A major application of AI is wearable and portable device-acquired ECGs110. This is built on the foundation of developments in deep learning for ECGs that initially leveraged the 12-lead ECG data captured in clinical settings to detect signatures of structural and functional cardiovascular disorders. For example, neural networks applied to 12-lead ECGs demonstrated the ability to identify subtle signatures of range of structural heart diseases with high accuracy111,112.

Wearable and portable ECG devices have expanded the accessibility of AI-ECG-based cardiac screening. Our group developed a noise-adapted AI model on augmented single-lead ECGs that demonstrated resilience to real-world signal artifacts, identifying LV systolic dysfunction with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.87 on noisy 1-lead ECG measurable on wearable devices52. Another study adopted a 12-lead model and achieved an AUROC of 0.88 for the same endpoint on Apple Watch ECGs. The study also highlighted the scalability of AI-enabled wearables by enrolling over 2400 participants remotely across multiple states, demonstrating high engagement and feasibility for population-level cardiac diagnostics113.

Beyond detecting systolic dysfunction, AI-ECG models have been applied to various other cardiovascular applications, including the detection of occult arrhythmias, predicting sleep apnea events, and screening for a broad range of structural heart disorders, such as functional, valvular, and infiltrative cardiomyopathies.

AI for handheld devices available in the community

POCUS is an accessible imaging modality increasingly integrated into clinical practice114. While it doesn’t necessitate extensive resources or advanced technology, acquiring high-quality ultrasound images requires training and experience115. AI-guided acquisition systems address this challenge by providing real-time feedback to users during scanning115,116. These systems analyze live images and offer guidance on probe positioning and movement, ensuring clinicians with limited ultrasound experience can capture images that can be more116. Beyond acquisition, AI tools have been developed to interpret POCUS images through advanced models capable of identifying clinical features typically inferred by experts reviewing high-quality imaging data117. Recent deep learning frameworks have demonstrated the ability to infer a full range of conditions from cardiac ultrasound even with limited imaging protocols, making it particularly valuable in resource-constrained and point-of-care acquisitions118. Recent work has also enabled the detection of a range of hidden signatures of disease from simple cardiac ultrasound16, detecting several underdiagnosed cardiomyopathies opportunistically, such as amyloid and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, by being able to diagnose these conditions directly on real-world POCUS studies done in emergency departments, despite the low quality of these images16. The approach that integrated synthetic data augmentation to overcome the inherent variability of POCUS imaging highlights the role of carefully designed deep learning-enabled algorithms in reducing the burden of expert review in triaging care and inferring clinical information from this high-fidelity portable technology.

Novel care paradigms powered by AI-enabled digital health devices

The current and emerging applications of AI to wearable and portable devices can enable broad changes to clinical care paradigms. Herein, we propose the applications.

Novel disease detection

The presence of low-cost wearable and portable devices directly in the communities unlocks the potential of scalability and accessibility for CVD screening. Most of these would represent the applications of AI to PPG and/or ECG as a first-level screen. However, given the low prevalence of many cardiovascular conditions in the community, the degree of false positives would overwhelm confirmatory testing systems. To address this, innovative detection systems tailored to low-prevalence settings are essential. These systems must incorporate strategic approaches within community-based disease detection programs. First, the technologies used must demonstrate consistent performance across broad demographic populations and those at risk for disease. Second, the deployment would have to be among a selected population with a certain threshold of prevalence. Third, whenever possible, a second-order screen would be done directly in the community, thereby reducing the number of referrals for confirmatory testing. An example of such an approach is the NIH-funded DETECT-AS study that is leveraging these three elements together in a multicenter randomized clinical trial119. It is a novel AS screen strategy that is deploying 1-lead portable ECG among older adults who have a higher prevalence of AS, with the model explicitly adapted to noisy acquisition on a portable device119. However, with an expected prevalence of 11% even among this selected population, 29% would be false positives. To address that, the study proposes to sequentially deploy an AI-assisted assessment of a novice-acquired cardiac POCUS to further enrich the screen, with the number of false positives expected to be 5%. While the performance of such tools in real-world practice remains to be established, the role of AI-assisted disease detection requires thoughtful design and explicit evaluation.

Cardiovascular risk prediction

AI-driven models are also increasingly being applied to wearable and point-of-care data to enhance cardiovascular risk prediction and personalized risk stratification. Unlike traditional risk scores, which often rely on a narrow set of variables, use static data points, and are typically validated only for specific populations with defined characteristics, AI-driven risk prediction models can leverage diverse and complex data sources, including real-time inputs from wearables, to stratify risk for a broader range of conditions. For instance, while traditional risk scores have focused on broad categories of conditions such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and HF22,23, emerging AI-driven models can provide risk assessment on a range of individual structural, functional, and arrhythmic cardiac disorders. These models can also dynamically adjust to the unique risk profiles of individuals, enabling more inclusive and accurate predictions across diverse demographic and clinical populations.

For example, AI algorithms applied to wearable ECGs have proven effective in predicting the risk of new-onset HF. Positively screened individuals were found to have a 3- to 7-fold higher risk of HF hospitalization across diverse cohorts in the United States, United Kingdom, and Brazil120. These AI-based models significantly outperformed traditional risk scores. Additionally, AI-ECG applications for wearable data have been successfully used to predict SHDs, with up to a six-fold increased risk observed in individuals likely to develop SHDs54. Therefore, these community-centered and precise risk assessments can enable more targeted and efficient decision-making but without burdening systems with extensive evaluations.

Therapeutic monitoring

AI-powered applications for wearable data are transforming therapeutic monitoring, offering innovative tools to evaluate treatment response and track disease progression in cardiovascular care. In contrast to traditional monitoring approaches, which depend on periodic clinic visits and place a significant burden on the patient to engage with their care, AI-driven solutions enable continuous, real-time monitoring that can be delivered remotely directly in the community. These systems integrate data from multiple sensors and metrics combining these parameters to reduce the reliance on proactive patient involvement while delivering high-quality insights. For example, for HF monitoring, changes in activity and sleep can serve as early warning signs of a decompensation event7,19. The timely availability of this data empowers clinicians to deliver timely interventions, potentially improving the overall management of these patients. One additional example is wearable-collected ECGs to monitor real-world outcomes of therapies. A recent series of studies demonstrated AI-ECG can also be used to evaluate responses to therapies for diseases with complex underlying pathophysiological processes, such as HCM, identifying those with response to therapy with mavacamten, a targeted therapy compared with surgical management that focuses only on resecting the septum87. Therefore, as more disease-specific AI models are developed, it is likely that many unique biomarkers of treatment and recovery will emerge and potentially meaningfully change how we deliver care, especially through their extension to widely available portable and wearable devices.

Triaging of care for limited healthcare resources

Another key application that does not flow as an extension of the clinical use of these models is how they would enable the efficient allocation of limited public healthcare resources. Among individuals referred for advanced cardiac imaging, patients with the disease might experience significant delays in confirmatory testing and treatment, while others without the disease are demonstrated to have normal results. While this is expected on any diagnostic test, when a timely diagnosis can change disease trajectory, prioritization based on expected results can enable fairer resource allocation. In this context, AI applications leveraging wearable-collected data present a promising solution by facilitating risk-based prioritization of advanced diagnostics and care by a test that can be provided in the community. For example, AI-ECG-based risk predictions help prioritize patients for advanced imaging by predicting the likelihood of a series of cardiomyopathies54,121. Similarly, where clinical imaging is challenging to obtain but advanced phenotyping is needed beyond what is offered by AI-ECG, a community-facing POCUS device that is interpreted with automated tools16,118, can further offer an even stronger clinical rationale for triaging testing.

Future directions

While wearable and portable devices powered by AI tools hold immense potential to transform community-based cardiovascular care, there are key proximate priorities: data standardization, equitable access with a participant-focused design, and robust ethical frameworks to regulate these technologies. To ensure scalability and equity, broader efforts are needed to address the digital divide that may limit access to AI-enabled wearables. Without these investments, there is a risk that such technologies may primarily benefit higher-income or tech-savvy populations, rather than closing the care gap they aim to address. The landscape of community and participant-powered networks is likely to mature and evolve with both opportunities for growth and additional challenges. It is imperative that these networks are nurtured with purposeful design, given their potential impact on resource-efficient and broadly accessible cardiovascular care. Future progress also depends on generating high-quality evidence through well-designed RCTs and prospective observational studies that demonstrate clinical utility and safety. In parallel, translating this evidence into practice will require sustainable reimbursement frameworks to support adoption within care models that prioritize value-based care. Moreover, to ensure these innovations are implemented responsibly and equitably across borders, global collaboration will be essential to advance international standards for data sharing, validation, and oversight, representing the foundation for trustworthy, accessible, and scalable cardiovascular care powered by AI-enabled community-based digital health devices. Table 1 summarizes the key challenges of incorporating AI-enabled consumer devices in cardiovascular care and potential solutions.

Conclusion

AI-enhanced wearable and portable devices represent a transformative force in cardiovascular care by enabling efficient, equitable, and accessible care directly in the communities. This paradigm represents a shift from reliance on resource-intensive, expert-driven processes toward scalable, technology-driven solutions that improve the cardiovascular health and outcomes of our communities without overwhelming our limited healthcare resources. However, this utopic future of community-focused cardiovascular care requires the purposeful design and robust evaluation of novel care pathways that leverage these tools with a specific focus on accurate, equitable, and accessible care.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Khera, R. et al. Transforming cardiovascular care with artificial intelligence: from discovery to practice. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 84, 97–114 (2024).

Alzaabi, M. A. et al. Evaluating biomarkers as tools for early detection and prognosis of heart failure: a comprehensive review. Card. Fail. Rev. 10, e06 (2024).

Moreno-Sánchez, P. A. et al. ECG-based data-driven solutions for diagnosis and prognosis of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. Comput. Biol. Med. 172, 108235 (2024).

Neumann, J. T. et al. Prognostic value of cardiovascular biomarkers in the population. JAMA 331, 1898–1909 (2024).

Peiris, D. et al. Cardiovascular disease risk profile and management practices in 45 low-income and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative individual-level survey data. PLoS Med. 18, e1003485 (2021).

Elias, P. et al. Artificial intelligence for cardiovascular care—Part 1: advances. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 2472–2486 (2024).

Oikonomou, E. K. & Khera, R. Artificial intelligence-enhanced patient evaluation: bridging art and science. Eur. Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae415 (2024).

Hughes, A., Shandhi, M. M. H., Master, H., Dunn, J. & Brittain, E. Wearable devices in cardiovascular medicine. Circ. Res. 132, 652–670 (2023).

Williams, G. J. et al. Wearable technology and the cardiovascular system: the future of patient assessment. Lancet Digit. Health 5, e467–e476 (2023).

Aminorroaya, A. et al. Use of smart devices to track cardiovascular health goals in the United States. JACC Adv. 2, 100544 (2023).

Dhingra, L. S. et al. Use of wearable devices in individuals with or at risk for cardiovascular disease in the US, 2019 to 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2316634 (2023).

Haq, K. T., Howell, S. J. & Tereshchenko, L. G. Applying artificial intelligence to ECG analysis: promise of a better future. Circ: Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 13, e009111 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening for atrial fibrillation using wearable devices. JAMA Health Forum 3, e222419–e222419 (2022).

Rajakariar, K. et al. Accuracy of a smartwatch based single-lead electrocardiogram device in detection of atrial fibrillation. Heart 106, 665–670 (2020).

Kim, S. et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) applications for point of care ultrasound (POCUS) in low-resource settings: a scoping review. Diagnostics (Basel)14, 1669 (2024).

Oikonomou, E. K. et al. Artificial intelligence-guided detection of under-recognised cardiomyopathies on point-of-care cardiac ultrasonography: a multicentre study. Lancet Digit. Health 7, e113–e123 (2025).

Ahmed, S. F. et al. Insights into Internet of Medical Things (IoMT): data fusion, security issues and potential solutions. Inf. Fusion 102, 102060 (2024).

Hanneman, K. et al. Value creation through artificial intelligence and cardiovascular imaging: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 149, e296–e311 (2024).

Krittanawong, C. et al. Integration of novel monitoring devices with machine learning technology for scalable cardiovascular management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 75–91 (2021).

Rossi, L. P. et al. Person-centered models for cardiovascular care: a review of the evidence: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 148, 512–542 (2023).

Visseren, F. L. et al. ESC Guidelines on CVD Prevention in Clinical Practice: Key Points (American College of Cardiology, 2021) https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/ten-points-to-remember/2021/08/30/17/25/2021-ESC-Guidelines-on-Prevention-ESC-2021.

Virani, S. S. et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline for the management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 148, e9–e119 (2023).

Pedroso Camargos, A. et al. Performance of contemporary cardiovascular risk stratification scores in Brazil: an evaluation in the ELSA-Brasil study. Open Heart 11, e002762 (2024).

Lindholt, J. S. & Søgaard, R. Why and when to screen for cardiovascular disease in healthy individuals. Heart 107, 1010–1017 (2021).

Ferket, B. S. et al. Systematic review of guidelines on cardiovascular risk assessment: which recommendations should clinicians follow for a cardiovascular health check?. Arch. Intern. Med. 170, 27–40 (2010).

Verma, K. P. et al. New cardiovascular risk assessment techniques for primary prevention: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 373–387 (2022).

Madamanchi, C., Di Carli, M. F. & Blankstein, R. What is multimodality cardiovascular imaging and how can it be delivered?. Heart 107, 503–508 (2020).

McGuire, H. & Weigl, B. H. Medical devices and diagnostics for cardiovascular diseases in low-resource settings. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 7, 737–748 (2014).

Tenorio-Mucha, J. et al. Facilitators and barriers of the implementation of point-of-care devices for cardiometabolic diseases: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 412 (2023).

Yang, Z., Zheng, X., Gao, Y., Zhang, C. & Wang, A. Strategies for enhancing home-based cardiac rehabilitation self-management for patients with coronary heart disease: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 24, 27 (2025).

Goevaerts, W. F. et al. Adherence to a lifestyle monitoring system in patients with heart disease: protocol for the care-on prospective observational trial. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23, 196 (2023).

Masoumian Hosseini, M., Masoumian Hosseini, S. T., Qayumi, K., Hosseinzadeh, S. & Sajadi Tabar, S. S. Smartwatches in healthcare medicine: assistance and monitoring; a scoping review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 23, 248 (2023).

Huhn, S. et al. The impact of wearable technologies in health research: scoping review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 10, e34384 (2022).

Marvasti, T. B. et al. Unlocking tomorrow’s health care: expanding the clinical scope of wearables by applying artificial intelligence. Can. J. Cardiol. 40, 1934–1945 (2024).

Castaneda, D., Esparza, A., Ghamari, M., Soltanpur, C. & Nazeran, H. A review on wearable photoplethysmography sensors and their potential future applications in health care. Int. J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 4, 195–202 (2018).

Dcosta, J. V., Ochoa, D. & Sanaur, S. Recent progress in flexible and wearable all organic photoplethysmography sensors for SpO2 monitoring. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 10, e2302752 (2023).

Sharma, M., Kacker, S. & Sharma, M. A brief introduction and review on galvanic skin response. J. Med. Res. 2, (2016).

Panigrahy, S. K., Jena, S. K. & Turuk, A. K. Study and analysis of human stress detection using galvanic skin response (GSR) sensor in wired and wireless environments. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 10, 545–550 (2017).

Vehkaoja, A., Peltokangas, M., Verho, J. & Lekkala, J. Combining unobtrusive electrocardiography and ballistography for more accurate monitoring of sleep. Int. J. Monit. Surv. Tech. Res. 1, 52–67 (2013).

Zhang, S. et al. Feasibility of nocturnal remote monitoring in patients with hfref. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 81, 451 (2023).

Pierleoni, P. et al. A wearable fall detector for elderly people based on AHRS and barometric sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 16, 6733–6744 (2016).

Fikry, M. et al. Improving complex nurse care activity recognition using barometric pressure sensors. In Human Activity and Behavior Analysis 261–283 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2024).

Di Costanzo, A., Spaccarotella, C. A. M., Esposito, G. & Indolfi, C. An artificial intelligence analysis of electrocardiograms for the clinical diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases: a narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 13, 1033 (2024).

Wang, R., Veera, S. C. M., Asan, O. & Liao, T. A systematic review on the use of consumer-based ECG wearables on cardiac health monitoring. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 28, 6525–6537 (2024).

Attia, Z. I., Harmon, D. M., Behr, E. R. & Friedman, P. A. Application of artificial intelligence to the electrocardiogram. Eur. Heart J. 42, 4717–4730 (2021).

Iwasaki, A. et al. Screening of sleep apnea based on heart rate variability and long short-term memory. Sleep. Breath. 25, 1821–1829 (2021).

Zheng, N. S. et al. Sleep patterns and risk of chronic disease as measured by long-term monitoring with commercial wearable devices in the All of Us Research Program. Nat. Med. 30, 2648–2656 (2024).

Gaona, G. A., Kassamali, A. A., Isakadze, N. & Martin, S. S. Harnessing wearables and digital technologies to decode the cardiovascular exposome. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc. J. 20, 59–70 (2024).

Vaccarino, V. & Bremner, J. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-024-01024-y (2024).

Rosman, L. et al. Wearable devices, health care use, and psychological well-being in patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e033750 (2024).

Gladstone, D. J. et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation in the older population: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 558–567 (2021).

Khunte, A. et al. Detection of left ventricular systolic dysfunction from single-lead electrocardiography adapted for portable and wearable devices. npj Digit. Med. 6, 1–10 (2023).

Aminorroaya, A. et al. Deep learning-enabled detection of aortic stenosis from noisy single lead electrocardiograms. medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.29.23296310 (2023).

Aminorroaya, A. et al. Development and multinational validation of an ensemble deep learning algorithm for detecting and predicting structural heart disease using noisy single-lead electrocardiograms. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health ztaf034 (2025).

Wu, J., Liu, Y., Yin, H. & Guo, M. A new generation of sensors for non-invasive blood glucose monitoring. Am. J. Transl. Res. 15, 3825–3837 (2023).

Zeynali, M., Alipour, K., Tarvirdizadeh, B. & Ghamari, M. Non-invasive blood glucose monitoring using PPG signals with various deep learning models and implementation using TinyML. Sci. Rep. 15, 581 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Wearable devices as tools for better hypertension management in elderly patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 31, e946079 (2025).

Lu, T. et al. Wearable equipment-based telemedical management via multiparameter monitoring on cardiovascular outcomes in elderly patients with chronic coronary heart disease: an open-labelled, randomised, controlled trial. BMJ Health Care Inf. 31, e101135 (2024).

Jacobs, P. G. et al. Integrating metabolic expenditure information from wearable fitness sensors into an AI-augmented automated insulin delivery system: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Digit. Health 5, e607–e617 (2023).

Gill, S. K. et al. Consumer wearable devices for evaluation of heart rate control using digoxin versus beta-blockers: the RATE-AF randomized trial. Nat. Med. 30, 2030–2036 (2024).

Azodo, I., Williams, R., Sheikh, A. & Cresswell, K. Opportunities and challenges surrounding the use of data from wearable sensor devices in health care: qualitative interview study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e19542 (2020).

Ortiz, B. L. et al. Data preprocessing techniques for AI and machine learning readiness: Scoping review of wearable sensor data in cancer care. JMIR MHealth UHealth 12, e59587 (2024).

Torab-Miandoab, A., Samad-Soltani, T., Jodati, A. & Rezaei-Hachesu, P. Interoperability of heterogeneous health information systems: a systematic literature review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 23, 18 (2023).

Armoundas, A. A. et al. Data interoperability for ambulatory monitoring of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 17, e000095 (2024).

Hosseini M, Dixon BE. Syntactic interoperability and the role of syntactic standards in health information exchange. In Health Information Exchange. 123–136 (2016).

Palojoki, S., Lehtonen, L. & Vuokko, R. Semantic interoperability of electronic health records: Systematic review of alternative approaches for enhancing patient information availability. JMIR Med. Inform. 12, e53535 (2024).

Guo, H., Scriney, M. & Liu, K. An ostensive information architecture to enhance semantic interoperability for healthcare information systems. Inf. Syst. Front. 1–24 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-023-10379-5 (2023).

Rigas, E. S. et al. Semantic interoperability for an AI-based applications platform for smart hospitals using HL7 FHIR. J. Syst. Softw. 215, 112093 (2024).

Ayaz, M., Pasha, M. F., Alzahrani, M. Y., Budiarto, R. & Stiawan, D. The Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard: systematic literature review of implementations, applications, challenges and opportunities. JMIR Med. Inform. 9, e21929 (2021).

Shankar, S. V. et al. Automated transformation of unstructured cardiovascular diagnostic reports into structured datasets using sequentially deployed large language models. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health ztaf030 (2025).

Malathi, K. et al. Medical data integration and interoperability through remote monitoring of healthcare devices. J. Wirel. Mob. Netw. Ubiquitous Comput. Dependable Appl.15, 60–72 (2024).

Jan, M. A., Zhang, W., Khan, F., Abbas, S. & Khan, R. Lightweight and smart data fusion approaches for wearable devices of the Internet of Medical Things. Inf. Fusion 103, 102076 (2024).

Ostrer, I. & Aronson, L. The perils of artificial intelligence in a clinical landscape. JAMA Intern. Med. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.7962 (2024).

Abbasi, J. & Hswen, Y. Tapping AI’s strengths-from operating room safety to wearable device interpretation. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.0802 (2024).

Wang, Y. & Sun, L. Energy-efficient dynamic sensor time series classification for edge health devices. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 254, 108268 (2024).

Marengo, A., Pagano, A. & Santamato, V. An efficient cardiovascular disease prediction model through AI-driven IoT technology. Comput. Biol. Med. 183, 109330 (2024).

Flores, H. AI sensors and dashboards. Computer (Long Beach, CA) 57, 55–64 (2024).

Bayoumy, K. et al. Smart wearable devices in cardiovascular care: where we are and how to move forward. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 581–599 (2021).

Varma, N. et al. Promises and perils of consumer mobile technologies in cardiovascular care: JACC scientific statement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 611–631 (2024).

TaheriNejad, N., Perego, P. & Rahmani, A. M. Mobile health technology: from daily care and pandemics to their energy consumption and environmental impact. Mob. Netw. Appl. 27, 652–656 (2022).

Andre, L. 53 Important Statistics About How Much Data is Created Every Day in 2024 https://financesonline.com/how-much-data-is-created-every-day/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (2021).

Strain, T. et al. Wearable-device-measured physical activity and future health risk. Nat. Med. 26, 1385–1391 (2020).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

All of Us Research Program Investigators et al. The “All of Us” Research Program. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 668–676 (2019).

Master, H. et al. Association of step counts over time with the risk of chronic disease in the All of Us Research Program. Nat. Med. 28, 2301–2308 (2022).

Thangaraj, P. M., Benson, S. H., Oikonomou, E. K., Asselbergs, F. W. & Khera, R. Cardiovascular care with digital twin technology in the era of generative artificial intelligence. Eur. Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae619 (2024).

Dhingra, L. S. et al. A multicenter evaluation of the impact of therapies on deep learning-based electrocardiographic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy markers. Am. J. Cardiol. 237, 35–40 (2024).

Hirten, R. P. et al. Physiological data collected from wearable devices identify and predict inflammatory bowel disease flares. Gastroenterology https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2024.12.024 (2025).

Burq, M. et al. Virtual exam for Parkinson’s disease enables frequent and reliable remote measurements of motor function. NPJ Digit. Med. 5, 65 (2022).

Kang, S., Paul, A. & Jeon, G. Reduction of mixed noise from wearable sensors in human-motion estimation. Comput. Electr. Eng. 61, 287–296 (2017).

Satija, U., Ramkumar, B. & Manikandan, M. S. A new automated signal quality-aware ECG beat classification method for unsupervised ECG diagnosis environments. IEEE Sens. J. 19, 277–286 (2019).

Satija, U., Ramkumar, B. & Manikandan, M. S. A review of signal processing techniques for electrocardiogram signal quality assessment. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 11, 36–52 (2018).

Bove, L. A. Increasing patient engagement through the use of wearable technology. J. Nurse Pract. 15, 535–539 (2019).

Kang, H. S. & Exworthy, M. Wearing the future-wearables to empower users to take greater responsibility for their health and care: scoping review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 10, e35684 (2022).

Ulloa-Cerna, A. E. et al. RECHOmmend: an ECG-based machine learning approach for identifying patients at increased risk of undiagnosed structural heart disease detectable by echocardiography. Circulation 146, 36–47 (2022).

Kelly, C. J., Karthikesalingam, A., Suleyman, M., Corrado, G. & King, D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 17, 195 (2019).

Dhingra, L. S. et al. Ensemble Deep Learning Algorithm for Structural Heart Disease Screening Using Electrocardiographic Images: PRESENT SHD. J Am Coll Cardiol. 85, 1302–1313 (2025).

Holtman, G. A. et al. Development of practical recommendations for diagnostic accuracy studies in low-prevalence situations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 114, 38–48 (2019).

Blom, M. et al. Second tier testing to reduce the number of non-actionable secondary findings and false-positive referrals in newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency. J. Clin. Immunol. 41, 1762–1773 (2021).

Croon, P. M., Pedroso, A. F. & Khera, R. The emerging role of AI in transforming cardiovascular care. Future Cardiol. 21, 547–550 (2025).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Predetermined Change Control Plans for Machine Learning-enabled Medical Devices: Guiding Principles (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2024) https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/predetermined-change-control-plans-machine-learning-enabled-medical-devices-guiding-principles.

Zinzuwadia, A. & Singh, J. P. Wearable devices-addressing bias and inequity. Lancet Digit. Health 4, e856–e857 (2022).

WHO Health Ethics & Governance. Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029200 (2017).

Ding, C., Xiao, R., Wang, W., Holdsworth, E. & Hu, X. Photoplethysmography based atrial fibrillation detection: a continually growing field. Physiol. Meas. 45, 04TR01 (2024).

Nie, G. et al. A review of deep learning methods for photoplethysmography data. arXiv:2401.12783 [cs.AI] (2024).

Almarshad, M. A., Islam, M. S., Al-Ahmadi, S. & BaHammam, A. S. Diagnostic features and potential applications of PPG signal in healthcare: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel)10, 547 (2022).

Avram, R. et al. Validation of an algorithm for continuous monitoring of atrial fibrillation using a consumer smartwatch. Heart Rhythm 18, 1482–1490 (2021).

Aschbacher, K. et al. Atrial fibrillation detection from raw photoplethysmography waveforms: a deep learning application. Heart Rhythm O2 1, 3–9 (2020)..

Alam, J. et al. A systematic approach focused on machine learning models for exploring the landscape of physiological measurement and estimation using photoplethysmography (PPG). J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 17, 669–684 (2024).

Sangha, V. et al. Automated multilabel diagnosis on electrocardiographic images and signals. Nat. Commun. 13, 1583 (2022).

Sangha, V. et al. Detection of left ventricular systolic dysfunction from electrocardiographic images. Circulation 148, 765–777 (2023).

Yao, X. et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiograms for identification of patients with low ejection fraction: a pragmatic, randomized clinical trial. Nat. Med. 27, 815–819 (2021).

Attia, Z. I. et al. Prospective evaluation of smartwatch-enabled detection of left ventricular dysfunction. Nat Med. 28, 2497–2503 (2022).

Chamsi-Pasha, M. A., Sengupta, P. P. & Zoghbi, W. A. Handheld echocardiography: current state and future perspectives. Circulation 136, 2178–2188 (2017).

Peck, D. et al. The use of artificial intelligence guidance for rheumatic heart disease screening by novices. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 36, 724–732 (2023).

Narang, A. et al. Utility of a deep-learning algorithm to guide novices to acquire echocardiograms for limited diagnostic use. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 624–632 (2021).

Holste, G. et al. Severe aortic stenosis detection by deep learning applied to echocardiography. Eur. Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad456 (2023).

Holste, G., Oikonomou, E.K., Wang, Z. & Khera, R. PanEcho: complete AI-enabled echocardiography interpretation with multi-task deep learning. JAMA in print https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.8731 (2025).

Khera, R. et al. Deep Learning Enhanced Detection and Personalized Monitoring of Aortic Stenosis—The DETECT-AS Study. Clinicaltrials.gov (2025) https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06749145.

Dhingra, L. S. et al. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Prediction of Heart Failure Risk From Single-Lead Electrocardiograms. JAMA Cardiol. 10, 574–584 (2025).

Dhingra, L. S. et al. Heart failure risk stratification using artificial intelligence applied to electrocardiogram images: a multinational study. Eur. Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae914 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Khera was supported by the National Institutes of Health (under awards R01AG089981, R01HL167858, and K23HL153775) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (under award 2022060). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F.P. and R.K. contributed equally to the development and writing of this review article. A.F.P. conceptualized the structure of the manuscript, conducted an extensive literature search, and drafted the initial sections. R.K. contributed to refining the article's focus, provided critical analysis of the selected literature, and wrote key sections of the manuscript. Both authors collaborated closely to edit, revise, and finalize the content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Khera is an Associate Editor of JAMA. He receives support from the National Institutes of Health (under awards R01AG089981, R01HL167858, and K23HL153775) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (under award 2022060). He also receives research support, through Yale, from Bristol-Myers Squibb, BridgeBio, and Novo Nordisk. In addition, Dr. Khera is a coinventor of U.S. Pending Patent Applications WO2023230345A1, US20220336048A1, 63/484,426, 63/508,315, 63/580,137, 63/606,203, 63/619,241, 63/562,335, and 63/346,610. Dr. Khera is also a co-founder of Ensight-AI and Evidence2Health, precision health platforms to improve evidence-based cardiovascular care.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pedroso, A.F., Khera, R. Leveraging AI-enhanced digital health with consumer devices for scalable cardiovascular screening, prediction, and monitoring. npj Cardiovasc Health 2, 34 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-025-00071-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-025-00071-9

This article is cited by

-

AI in Adipose Imaging: Revolutionizing Visceral Adipose Tissue, Ectopic Fat, and Cardiovascular Risk Assessment

Current Atherosclerosis Reports (2025)