Abstract

Despite cardiovascular disease risk reduction with intensive lifestyle modification, durable healthy behavior change remains elusive. An evidence-based framework for optimizing artificial intelligence (AI) augmented pro-health behavior change interventions features AI, behavioral, and medical expert collaboration in (1) use-case development, (2) real-time risk-benefit oversight, (3) modeling bias mitigation, and (4) personalizing disease management. User safety perquisites include 1) autonomy, (2) data transparency, (3) explainable model trust-building, and (4) risk-reward neuromodulation avoidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medical and societal imperatives exist to modify unhealthy behaviors that contribute to the growing burden of chronic diseases and excess wastage of human lives1. However, the paucity of successful behavioral intervention level-sets plus the dynamism of individual behavior change thresholds, has perpetuated a paradox – the dissociation between recognized healthy behaviors that could collectively augment the human condition, and the daily poor personal health decisions that negatively impact human health.

Healthcare providers struggle to influence, and patients frequently fail to effect salutary health behavior changes. The burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) attributable to modifiable bad habits – smoking, unhealthy diet, obesity, inactivity, medication non-compliance – remains the main contributor to deaths before age 752,3. Refractoriness to lifestyle change finds unhealthy behaviors contributing to ~50% of premature deaths from heart disease, stroke, and cancer4.

While intensive interventions targeting harmful behaviors can improve health outcomes5, their benefits are difficult to sustain. Behavioral science has identified “malleable targets” at the social, contextual, behavioral, psychological, neurobiological, and genetic levels3. But it remains unclear to behavioral experts how some successful pro-health interventions have worked6. Mechanisms of greatest interest are those that initiate and maintain behavior changes, including adherence to healthy lifestyles and/or biomedical regimens7. Regardless of these scientifically robust mechanistic frameworks, the innate human incapacity to pursue healthier behaviors derails medical and societal efforts to prolong life.

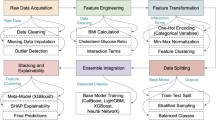

One solution to such behavioral ambiguity and real-world unpredictability could be the purposeful union of behavioral health expertise with advanced artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. For healthy decisions to occur and to stick, domain experts and intelligent machines must understand the shared information flows and data contexts underpinning both human cognition and AI insights. This Perspective provides an evidence-based framework (see Table 1.) in support of developing and safely applying AI interventions for durable pro-health behavior change. In this context, measures for active human involvement in risk-benefit monitoring of existing and emerging AI technologies are proposed.

Humans and machines: processing in parallel

The processes by which human brains or human-built AI turn information (data, text, images, etc.) into knowledge, then understanding, and hopefully wisdom, is subject to many confounding influences. Neither humans nor machines have perfect knowledge and unlimited computational ability. Despite these limitations, humans and machines can perceive their environments and make decisions to take autonomous actions that achieve specific goals (the objective function). Machines can be trained to perform a plan-of-action that exceeds the most basic human need to maximize pleasure and comfort. Advanced deep learning (DL) technologies8,9,10,11 have actionable goals and can do reinforcement learning (the reward function), creating human-like “sensations” that are shaped by sequential time steps during DL model optimization (the fitness function).

Similarities and differences exist in goal-directed elements of human cognition and AI modeling in support of decision-making (see Fig. 1). Despite such apparent human-machine parallelism, neither the behavioral nor AI expert camps have bridged the interdisciplinary divide to fully share knowledge and explore technological synergies that could achieve healthier human behaviors and outcomes.

Depiction of the similarities and differences between human cognition development and artificial intelligence (AI) model training to create the necessary understanding/insights for initiating and sustaining pro-health behavior change. Some of the many opportunities for expert collaborations are shown (i.e., domain expertise improves AI modeling, bidirectional information flows in shared data environments, AI model explainability to build trust among users). Not shown is the imperative for human oversight of the AI-augmented behavioral change interventions to assure user safety.

Informed decision-support

Decision-making behaviors are complex cognitive processes influenced by biases, heuristics, and contextual factors. The complexities of human-machine interfaces and countervailing risk-reward neuro-modulatory pathways also present daunting challenges. The first step towards augmenting pro-health behaviors is to understand the information flows that inform decision-making, in the context of existing human knowledge gaps and embedded AI model biases.

Shared environments

Human behaviors are accessed and adopted via complex networks, influenced by social structures and societal norms, and contextualized within diverse settings (perceived reality, virtual reality, etc.). Decision-making requires information flows in shared environments, producing human understanding that can transfer the knowledge necessary for behavioral-changing decisions. The resulting human decisions are not always rational (i.e., not designed to maximize the utility function), and are routinely influenced by heuristic shortcuts and human biases.

Whether scraping data sources or being fed facts by humans, AI decision support requires machines to understand the salience of complex information flows within shared contexts. Real-world human environments often feature dynamic data flows and/or low signal-to-noise sensor inputs that contribute to AI modeling uncertainties, negatively impacting intelligent machines’ efficiency and accuracy. Sensorimotor trial & error reinforcement during AI modeling can emulate human risk-reward behaviors12,13.

Learned behaviors

Human behaviors are developed through learned experiences and/or communication modes (written, verbal, etc.). Neuro-modulatory pathways influence hypersocial behaviors, including decision-making towards pleasurable and/or addictive experiences14. The factors employed by AI (in social media, search algorithms, etc.) to grow customer engagement often cause unhealthy neuromodulation15, disrupting healthy self-regulation by triggering immediate gratification responses16,17,18. Unpredictable self-regulation of risk-reward behaviors (i.e., neuro-economics of delayed discounting) explains individual impulsivity and over-confidence3,19,20. While self-control behaviors remain largely unchanged from childhood, a lifetime of learned behaviors is interspersed with acute bursts of situational decision-making (i.e., positive or negative planned actions).

Decisions to adopt, modulate, and/or sustain newly learned behaviors (i.e., identity formation) are influenced by information flows, framed with cues & nudges, and subject to disinformation21 and adverse life experiences (i.e., losses, illnesses)22. As such, it is not surprising that health behavior changes are difficult for individuals to initiate23 and hard for at-risk populations to sustain24. Pro-health decisions can be derailed by personal stressors (i.e., family, career), lack of willpower (i.e., self-discipline, altered sensorium), and poorly understood disease mechanisms25.

Some AI models provide the why behind their predictions (i.e., are “explainable”), while others do not (i.e., are “black boxes”)26. Both explainable and black box AI models can make correct and incorrect predictions that could improve decision-making27,28. Some psychologists consider human cognition to also be a black box, as opaque as any AI neural network29.

Behavior change theories

Established behavioral change theories acknowledge the complex relationships between the brain’s receipt of information and resulting behaviors (see Table 2). Behavioral scientists offer diverse explanations for behavior changes. While largely developed before advanced AI technologies23,24,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, some behavior change theories could be refreshed or reframed to inform pro-health AI use-cases. One salient candidate behavior change theory is the Nudge Theory37. Nudge Theory is rooted in behavioral economics psychology, and challenges notions of rationality in decision-making by proposing that subtle interventions – “nudges” – can significantly impact human behaviors without restricting freedom of choice. Nudges leverage how quick, habitual choices are presented and structured. The resulting choice architecture exploits cognitive biases & heuristics by altering decision contexts, leveraging the social & cultural norms that influence behaviors.

Nudge interventions are effective for promoting positive behavior changes (increasing physical activity levels, improving dietary choices) and for promoting medication adherence in individuals and populations38,43. However, nudges may erode trust through unethical exploitation, manipulation and/or reinforcement of existing biases. Experts advocate for policies to prevent the covert collection and use of sensitive personal information for nudging purposes44.

AI augmented nudges

Nudging by advanced algorithms has emerged as a method for influencing human behaviors across healthcare, energy, and finance sectors. Tailored AI nudging interventions using personalized and context-aware models can positively impact behaviors. AI nudging through wearable devices produces significantly increased participant physical activity levels45. By providing personalized feedback and social accountability, AI nudge interventions effectively motivate individuals to engage in healthier behaviors.

Unfortunately, there is a scarcity of longitudinal studies to support the long-term outcomes (i.e., sustainability) of AI nudging. Controversy also exists about the efficacy of AI augmented nudging versus AI boosting strategies, with the latter designed to enhance individuals’ cognition and/or motivation. Boosting advocates argue that providing skills and tools for making better decisions empowers users rather than merely steering their choices46. Boosting may build competence and promote more autonomous long-term decision-making.

Generative AI anthropomorphology

Natural languages are uniquely human among information flows, being primarily used during face-to-face communication47. Generative AI (Gen AI) transformers also process natural languages, detecting linguistic nuances and parsing lexical ambiguities. Gen AI deftly imitates human knowledge transfer by learning from one task to solve a wide array of downstream tasks48,49,50,51. An array of Gen AI large language models (LLM) has been deployed (see Table 3), with remarkable anthropomorphic language fluency52.

LLM produces text-based conversational content (i.e., chat), enabling goal-driven, personalized, and responsive interactions through real-time dialog with consumers. Gen AI virtual assistants offer contextual reasoning and can rapidly generate tailored responses to user queries. Medical LLM provide high-quality, reliable information, highlighting their potential as supplementary tools to enhance patient education and potentially improve clinical outcomes53,54. For example, ChatGPT (OpenAI, Nov. 2022) generated 84% accurate responses to CV disease prevention questions55.

Another study showed that physicians using ChatGPT Plus (OpenAI, Feb. 2023) did not exhibit improved diagnostic decision-making over those using conventional resources (76% vs 74% accuracy)56. And while cogent-sounding LLM prose could potentially inform healthy behavior change decisions, they are neither personal health information (PHI) privacy policy-compliant nor approved by federal regulators for direct patient care.

Gen AI nudging

Integration of Gen AI nudging into the consumer choice architecture is altering decision-making paradigms by emphasizing consumer-specific benefits and simplifying choice complexity57. Narrow Gen AI nudges are specific prompts supporting immediate targeted actions (consumer satisfaction, repurchase intentions). Broad Gen AI nudges offer expansive responses that encourage deeper personal engagement. Both approaches, if collaboratively developed and closely monitored for user safety, could prompt and sustain pro-health behavior changes.

AI for disease self-management

Prevention programs recognize the critical role of glycemic control and weight reduction for reducing CV death and disability in diabetes mellitus (DM). In an era before advanced deep learning and Gen AI, the NIH Diabetes Prevention Program demonstrated that intensive lifestyle modification (of diet and exercise) coupled with behavior change reinforcement improved DM type-2 outcomes compared to an oral hypoglycemic drug5. Other behavior modification studies show that patients lacking personal motivation are prone to DM progression58.

Early mobile phone apps for disease self-management did not consider health behavior theories and did not apply AI technologies59,60. A newer AI augmented platform for DM type-2 self-management was designed by computer scientists with clinician and patient input. It uses a mobile app for macronutrient detection and meal recognition (by multimodal image analysis) and AI nudge-inspired meal logging61. Future prototypes will increase food data diversity beyond current models skewed to North American diets, with the potential for predicting individual glycemic control62.

Caveats and collaboration

Can sophisticated AI technologies safely augment pro-health decision-making? Health IT experts remain wary about AI insertion into systems of care. Abiding ethical issues demand greater scrutiny of LLM fairness and robustness before new product release53, and require continuing education of patients54, policymakers63, and providers64.

Legitimate concerns persist about non-health AI adversely impacting risk-reward neuro-modulatory conditioning and triggering human misbehaviors. AI-augmented health behavior changes that are potentially hardwired to dopaminergic pathways could render individuals and society less healthy. While overlaying powerful algorithms onto developed world data to generate models promoting health sounds promising, AI model variant morphing during scaling could widen existing population health gaps into chasms. Model optimization biases and mercurial human behavior change thresholds represent enduring challenges.

Given these caveats, AI champions and watchdogs alike must collaborate to seek ground truths and mitigate risks. This requires their purposeful engagement with domain experts including (1) behavioral scientists (i.e., psychologists, sociologists) to help AI engineers query complex datasets and do data diversity audits, (2) medical decision-makers (i.e., physicians, extenders) to understand CVD variability and explain model limitations for high-risk patient care decisions, and (3) privacy stewards (i.e., policymakers, regulators) to promote PHI security while transparently assuring individuals’ data rights. Together, these experts could comprise independent technology monitoring advisory boards for real-world oversight of AI-augmented behavior change interventions.

Conclusions

Because durable pro-health behavior changes are so hard to initiate and sustain, poor CV health and excess CVD mortality persist. This proposed framework, based on existing evidence and reasonable extrapolation, is intended to stimulate an interdisciplinary dialog (and related expert collaborations) about factors critical to the design, insertion, and surveillance of AI-augmented interventions to safely effect durable pro-health behavior changes. Humans with deep domain expertise and machines with powerful predictive modeling capabilities, when collaborating across decision boundaries in shared data environments, are poised to do the hardest thing – engineer smart AI interventions to safely nudge healthy choices and promote durable pro-health habits.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Heueveline, P. Global and National Declines in Life Expectancy: An End-of-2021 Assessment. Popul. Dev. Rev. 48, 31–50 (2022).

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html (2022).

Nielson, L. et al. The NIH Science of Behavior Change Program: Transforming the science through a focus on mechanisms of change. Behavioral Research and Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.07.002

Mather, M. & Scommegna, P. Up to Half of U.S. Premature Deaths are Preventable; Behavioral Factors Key. Population Reference Bureau. https://www.prb.org/resources/up-to-half-of-u-s-premature-deaths-are-preventable-behavioral-factors-key

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group The DPP Description of Lifestyle Intervention. Diab. Care 25, 2165–2171 (2002).

Davidson, K. W. & Scholz, U. Understanding and Predicting Health Behaviour Change: A Contemporary View through the Lens of Meta-review. Health Psych. Rev. 14, 1–5 (2020).

McGlashan, J. et al. Comparing complex perspectives on obesity drivers: action-driven communities and evidence-oriented experts. Obes., Sci. Pract. 4, 575–581 (2018).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Sejnowski, T. J. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Deep Learning in Artificial Intelligence. PNAS 117, 30033–30038 (2020).

Feng, D. et al. Deep Multi-modal Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation for Autonomous Driving: Datasets, Methods and Challenges. arXiv:1902.07830v3[cs.RO] (2019).

Shugang Z. et al. A Review on Human Activity Recognition (HAR) using Vision-based Method. J. Healthcare Engineering, pp. 1–31, (2017).

Silver, D., Singh, S., Precup, D. & Sutton, R. S. Reward is not enough. Artificial Intell. 299 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2021.103535.

Pentland, A. & Lui, A. Modeling and Prediction of Human Behavior. Neural Comput. 11, 229–241 (1999).

Elsinger, P. J. et al. The neuroscience of social feelings: mechanisms of adaptive social functioning. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 128, 592–620 (2021).

Subrahmanian, V. S. & Kumar, S. Predicting Human Behavior: The Next Frontiers. Science 355, 2017 https://www.science.org.

Korte, M. The impact of the digital revolution on human brain and behavior: where do we stand? 22: 101-111, (2022).

Lembke, A. Dopamine Nation – Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence. Penguin Random House LLC - Dutton, New York, (2021).

Qui, T. A. Psychiatrist’s Perspective on Social Media Algorithms and Mental Health. https://hai.stanford.edu/news/psychiatrists-perspective-social-media-algorithms-and-mental-health.

Croote, D. E. et al. Delay discounting decisions are linked to temporal distance representations of world events across cultures. Nature Sci. Rep. 10 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-69700-w.

Ahn, W.-Y. et al. Rapid, precise, and reliable measurement of delay discounting using a Bayesian learning algorithm. Nat. Sci. Rep. 10, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-68587-x.

Berriche, M. & Altay, S. Internet Users Engage More with Phatic Posts than with Health Misinformation on Facebook (Health related misinformation, cultural attraction theory). Palgrave Commun. (Hum. Soc. Sci., Bus. 6, 71 (2020). .

Sattari, S. et al. Modes of information flow in collective cohesion. Sci. Adv. 8, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj1720 (2022).

Albarracin, D. Action and Inaction in a Social World. Chapter 5. The impact of past experience and past behavior on attitudes and behavior. Cambridge University Press, https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/F359EC09F1FEDCFE5CDBAB9FDD407C9F.

Dobson, A. D. M., de Lange, E., Keane, A., Ibbett, H. & Milner-Gulland, E. J. Integrating Models of Human Behaviour Between the Individual and Population Levels to Inform Conservation Interventions. Phil. Trans. R Soc. B 374, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0053.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Science of Behavioral Change (SOBC) Measures Repository https://commonfund.nih.gov/behaviorchange.

Rudin, C. Stop Explaining Black Box Machine Learning Models for High Stakes Decisions and Use Interpretable Models Instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 206–215 (2019).

Miller, T. Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artif. Intell. 267, 1–38 (2019).

Adadi, A. & Berrada, M. Peeking inside the black box: A survey on explainable artificial intelligence XAI). IEEE Access 6, 52138–52160 (2018). .

Bonezzi, A., Ostinelli, M. & Melzner, J. The human black-box: the illusion of understanding humans better than algorithmic decision-making. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 151, 2250–2262 (2022).

Prochaska, J. O. & DiClemente, C. C. Transtheoretical therapy: Towards a more integrative model of change. Psychol.: Theory, Res. Pract. 19, 276–288 (1982).

Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall Inc. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1985-98423-000.

Rutter, D. R. & Bruce, D. The theory of reasoned action of Fishbein and Ajzen. A test of Towriss's amended procedure for measuring beliefs. Br. Pysch J. 28, 39–46 (1989).

Madden, T. J., Ellen, P. S. & Ajzen, I. A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 18, 3–9 (1992).

Sharma, M. Theory of reasoned action & theory of planned behavior in alcohol and drug education. J. Alc Drug Ed. 51, 3–7 (2007).

Gollwitzer, P. M. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. Am. Psychol. 54, 493–503 (1999).

Webb, T. L. & Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 132, 249–268 (2006).

Thaler, R. H., Sunstein, C. R. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, (2008).

Thaler, R. H., Sunstein, C. R. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. Penguin Books, New York, NY, (2009).

Davis, R., Campbell, R., Hildon, Z., Hobbs, L. & Michie, S. Theories of behavior and behavior change across the social and behavioral sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol. Rev. 9, 323–344 (2015).

Verplanken, B. & Roy, D. Empowering interventions to promote sustainable lifestyles: Testing the habit discontinuity hypothesis in a field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 45, 127–134 (2016).

Bro-Jorgensen, J., Franks, D. W. & Meise, K. Linking behavior to dynamics of populations and communities: application of novel approaches in behavioral ecology to conservation. 10 https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2019.0008.

Sattari, S. et al. Modes of information flow in collective cohesion. Sci. Adv. 8, (2022). http://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj1720 Pagel, M. Q&A: What is human language, when did it evolve and why should we care? BMC Biol. 15(1):64 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj1720.

Hollands, G. J. et al. Altering micro-environments to change population health behaviour: towards an evidence base for choice architecture interventions. BMC Public Health 13, 1218 (2013).

Sunstein, C. R. Nudging: A very short guide. J. Consum. Policy 37, 583–588 (2014).

Munson, S. A., Consolvo, S. & Pratt, W. Effects of public commitments and accountability in a technology-supported physical activity intervention. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1135–1144). Association for Computing Machinery, (2015).

Grune-Yanoff, T. & Hertwig, R. Nudge versus boost: How coherent are policy and theory? Minds Mach. 26, 149–183 (2016).

Chakraborty, M. et al. Core and Shell Song Systems Unique to the Parrot Brain. PLOS One 10, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118496.

Bommasani, R. et al. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models (BERT, DALL-E, GPT-3). arXiv:2108.07258v2 [cs.LG] https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258v2.

Aditya, R. et al. Zero-shot Text-to-image Generation (DALL-E). arXiv:2102.12092v2 [cs.CV](2021).

Ramesh, A. et al. DALL-E generative modeler for images from captions. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2102.12092.pdf.

PaLM Beats LaMDA Google Blog 2022 http://ai.googleblog.com/2022/04/pathways-language-model-palm-scaling-to.html.

Li, R., Kumar, A. & Chen, J. H. How Chatbots and Large Language Model Artificial Intelligence Systems Will Reshape Modern Medicine: Fountain of Creativity or Pandora’s Box? JAMA Intern Med 183, 596–597 (2023).

Shah, N. H., Entwistle, D. & Pfeffer, M. A. Creation and Adoption of Large Language Models in Medicine. JAMA 330, 866–869 (2023).

Blumenthal, D. & Goldberg, C. Managing Patient Use of Generative Health AI. NEJM AI 2, https://doi.org/10.1056/AIpc2400927 (2024).

Sarraju, A. et al. Appropriateness of Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Recommendations Obtained from a Popular Online Chat-Based Artificial Intelligence Model. JAMA 329, 842–844 (2023).

Goh, E. et al. Large Language Model Influence on Diagnostic Reasoning: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2440969 (2024).

Richarde, A. P. M., Pinto, D. C., Dalmoro, M. & Prado, P. H. M. The power of Generative AI Nudges: How Generative AI Shapes Consumer Empowerment and Goal Desirability. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 85, 102995 (2025).

Crandall, J. P. et al. The Diabetes Prevention Program and Its Outcomes Study: NIDDK’s Journey into the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes and Its Public Health Impact. Diab. Care 48, 1101–1111 (2025).

Chavez, S. et al. Mobile Apps for the Management of Diabetes. Diab. Care 40, e145–e146 (2017).

Adu, M. D., Malabu, U. H., Callander, E. J., Malau-Aduli, A. E. & Malau-Aduli, B. S. Considerations for the Development of Mobile Phone Apps to Support Diabetes Self-Management: Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 6, e10115 (2018).

Joachim, S., Forkan, A. M., Jayaraman, P. P., Morshed, A. & Wickramasinghe, N. A Nudge-Inspired AI-Driven Health Platform for Self-Management of Diabetes. Sensors 22, 4620 (2022).

Google A. I. Y., Vision. “Food_V1.” Google AIY, TenserflowHub. https://tfhub.dev/google/aiy/vision/classifier/food_V1/1.

Blumenthal, D. & Marellapudi, A. More Fragmented, More Complex: State Regulation of AI in Health Care. NEJM AI, May 5, https://doi.org/10.1056/AIpc2500163 (2025).

Miller, D. D., Kamath, M., Albers, J. & Hess, D. C. Leveraging Medical Licensure for Safer Artificial Intelligence Use in Health Care. Am. J. Med 138, 1319–1321 (2025).

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. D. Miller conceived, analyzed the data, and wrote this manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, D.D. Can AI help with the hardest thing: pro health behavior change. npj Cardiovasc Health 3, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-025-00101-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-025-00101-6