Abstract

Capacitive pressure sensors (CPSs) are increasingly important for wearable and textile-based health monitoring due to their high sensitivity, low power consumption, and structural flexibility. Building on a structured literature review (2015–2025), we conducted a systematic analysis of 34 CPS designs across five categories—microstructuring, foams, ionic liquids/gels/metals, bioinspired architectures, and multisensing/strong bonding—using a newly developed Textile Suitability Score (TSS) that integrates nine performance and integration-relevant attributes. Trade-off analysis revealed that ionic metal-based sensors dominate in raw performance, combining very high sensitivity with broad pressure ranges, but face scalability and textile-compatibility challenges. By contrast, microstructuring offers the closest balance between sensitivity and integration, while multisensing and strong bonding form a consistent cluster with the highest TSS values. Foams and bioinspired designs ranked lower due to reproducibility and stability issues. Together, these results expose clear performance-integration trade-offs and uncover unexplored design pathways, charting a roadmap for next-generation textile-integrated health monitoring systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wearable and textile-integrated sensing systems have emerged as key enablers of continuous, non-invasive health monitoring in clinical, athletic, and daily life settings1,2. Capacitive pressure sensors (CPSs) are among the most promising technologies for these applications, owing to their high sensitivity, low power consumption, structural simplicity, and adaptability to flexible and stretchable substrates3,4,5. Flexible wearable sensors are being actively developed due to their broad application potential6,7,8,9,10. Inspired by human skin—which can detect a variety of stimuli11, with tactile sensing as a primary function12,13,14,15—robust and sensitive pressure sensors have emerged as promising tools for a wide range of applications, including wearable devices16, health monitoring17,18, robotic skins19,20,21, and human-interactive perception22,23,24. To date, great progress has been made based on different sensing mechanisms in designing pressure sensors, including piezoelectric25,26,27, piezo-resistive28,29,30,31, and piezo-capacitive32 sensors among others. Piezoelectric pressure sensors operate on the basis of the piezoelectric effect, generating an electrical signal in response to dynamic mechanical stress33. These sensors are especially suited for dynamic pressure sensing and high-frequency response34. In contrast, piezoresistive sensors are better suited for static pressure detection35,36. Among those types of pressure sensors, CPSs have emerged as a promising alternative due to their high sensitivity, simple structure, and excellent potential for further miniaturization3. CPSs operate by measuring changes in capacitance caused by applied pressure, and while they may exhibit lower sensitivity at higher pressures, they are well-known for their high sensitivity and linearity at low pressures32. To date, researchers have made lots of efforts to improve the comprehensive performance of the capacitive sensors in various aspects, such as high sensitivity in a wide pressure range, stability, short response time and low detection limit. We argue that, with proper material and structural design, capacitive sensors can potentially achieve a wide sensing range and meet the demands of real-time health monitoring applications in wearable applications due to their small size, high sensitivity, low cost, and simple fabrication4,5. However, many crucial parameters need to be taken into account when considering their widespread development such as scalability, bio-compatibility, and fabrication complexity that they are crucial for their scalability and ease of application. Over the past decade, CPS designs have diversified considerably, incorporating microstructured dielectrics, porous foams, ionic liquid-based systems, bioinspired architectures, and multimodal bonded configurations. Each of these design categories offers distinct performance profiles in terms of sensitivity, pressure range, detection limit, stability, and fabrication scalability.

While individual studies have demonstrated outstanding performance in one or more of these metrics, the literature remains fragmented. Critically, there is no standardized framework to compare CPS designs in the context of textile integration—a scenario that imposes additional requirements beyond raw sensing performance, including biocompatibility, safety, scalability, fabrication complexity, and mechanical durability under bending or strain. As a result, CPS selection for wearable applications is often guided by isolated metrics rather than a comprehensive integration-oriented assessment.

To address this gap, we developed a quantitative evaluation framework based on a Textile Suitability Score (TSS) that integrates nine quantitative and qualitative attributes into a single normalized metric. This approach allows multi-criteria benchmarking of CPSs, enabling direct comparison across disparate designs and fabrication strategies. Using a structured literature search, we compiled a dataset of CPS performance parameters reported between 01 January 2015 and 01 January 2025, spanning five main architectural categories: (1) microstructuring of dielectrics and electrodes, (2) foams and air gap engineering, (3) ionic liquids, gels, and metal-based systems, (4) bioinspired designs, and (5) multisensing and strong bonding strategies.

The objectives of this study are to:

-

1.

Establish a reproducible, multi-attribute evaluation framework for CPSs intended for textile integration.

-

2.

Apply this framework to a comprehensive dataset of published CPS designs.

-

3.

Identify CPS architectures that offer optimal trade-offs between sensing performance and integration readiness.

Results

Dataset overview

The final dataset comprised 34 studies published between 2015 and 2025, representing five primary CPS architecture categories: (1) Microstructuring of dielectrics and electrodes, (2) Foams and air gap engineering, (3) Ionic liquids, gels, and metal-based systems, (4) Bioinspired designs, and (5) Multisensing and strong bonding.

The study identification and screening process is summarized in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

PRISMA flowchart showing the identification, screening and inclusion of studies. The diagram outlines the number of records identified through database searching, the number of duplicates removed, the records excluded after screening, and the final number of studies included in the qualitative and quantitative synthesis.

In brief, 63 articles were initially identified (30 from Embase, 17 from PubMed, and 16 from Google Scholar). After removing duplicates (n = 8), 55 records were screened, with one excluded due to lack of access or unsuitable format. Of the 54 full-text articles assessed, 20 were excluded (15 for poor relevance and 5 for insufficient data). This yielded 34 articles that were included in the final analysis.

For each included study, quantitative and qualitative metrics were extracted and processed as described in the Methods section. These values are summarized in category-specific tables (Tables 1–5), and application-specific performance mapping is presented in Table 6.

Across the dataset, reported sensitivities ranged from 0.005 kPa−1 to over 10,000 kPa−1, while pressure ranges spanned from ultra-low (<10 kPa) for fine physiological monitoring to ultra-wide (>1 MPa) for high-load applications. Cyclic stability varied from <500 cycles to >100,000 cycles. Response times ranged from sub-10 ms in high-speed systems to >1 s in some foam-based architectures.

Microstructuring of dielectrics and electrodes for enhanced performance

The concept of creating microstructures that form a dielectric layer between electrodes to increase sensitivity was introduced by Bao’s research group in 201037. Mannsfeld et al. showed that microstructured films significantly exceeded the sensitivity of unstructured elastomeric films of similar thickness. They prove that by adding a small number of micropyramids to a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) dielectric layer increased sensitivity more than 30-fold compared to an unstructured PDMS layer of the same size.

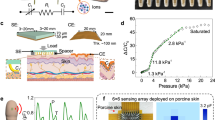

The process used to create the microstructures is schematically illustrated in Fig. 2a. More specifically, the microstructured dielectric provided substantially higher sensitivity in for the same pressure regimes, with short response and relaxation times (less than 1 s) with the values recorded 0.02 kPa−1 (unstructured) and 0.55 kPa−1 (micropyramids) for a pressure range up to 2 kPa. The high definition structuring of thin elastomeric films was subsequently widely adopted by fine-tuning microstructured elastomeric films to achieve a sensitivity of up to 0.76 kPa−1 (slightly higher compared to the previous) for the same pressure range of 0–2 kPa, and then was, as expected, reduced to 0.11 kPa−1 for the range 2–10 kPa38. This led to a new class of highly compressible sensors with short response and relaxation times made entirely from biodegradable materials (Fig. 2b)39. Those studies open the door for high sensitivity pressure monitoring in the low-scale pressures that are suitable for fine-recordings of vital signals such as pulse monitoring, with many subsequent studies following the micro-tuning ideas for specific application scenarios, as unlike traditional stiff dielectrics, the creation of micropyramids created air gaps.

a Schematic process for the fabrication of microstructured PDMS films. Adapted with permission from Nature Materials. Copyright 2010, Nature Communications37. b Schematic design and fabrication of a fully biodegradable and flexible pressure sensor array and its device structure made from poly(glycerol sebacate) PGS films. Adapted with permission from Advanced Materials. John Wiley and Sons, 201538.

Subsequent research expanded on this by observing that single-sized pyramidal microstructures were observed to suffer from a trade-off between sensitivity and hysteresis, and the spacing between adjacent pyramids was identified as the key factor influencing these two parameters. To address this issue, Cheng et al. fabricated a hierarchically structured electrode consisting of pyramids of different sizes to increase sensitivity and reduce interfacial adhesion40. They tested eight spacing configurations to identify the optimal spacing between the pyramids and further enhance performance. Consequently, a hierarchically structured electrode was introduced, consisting of pyramids of different sizes (Fig. 3a). The optimized sensor design showed that significant increase in sensitivity, achieving (3.73 kPa−1), which is about three times higher than the previous studies37,38, and sensing range up to 100 kPa, enabling a simultaneous increase in sensitivity and sensing range. The CPS was also very sensitive under low pressure, having a low detection limit at 0.1 Pa. Moreover, by ensuring that the sharp parts of the microstructure were easy to squish when a small force was applied, they also achieved low hysteresis (~4.42%). However, as the force increased, the material became less flexible, becoming less consistent, leading to nonlinear behavior under higher pressure.

a Hierarchically structured CPS made of pyramids of different sizes. Adapted with permission from IEEE Electron Device Letters40. b Three-dimensional microconformal graphene electrodes with adjustable microstructures and conformal graphene conductive films for innovative applications. Adapted with permission from Applied Materials. © American Chemical Society, 201942. c Gradient microdome architecture with optimized microdome height and arrangement. Adapted with permission from Small. © John Wiley and Sons, 202145. d Schematic diagram of the sensor with the dual dielectric layers, with the composite electrode made from CNTs, MXene, and PDMS. Adapted with permission from ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces. ACS Publications, 202448.

Introducing a novel method for modifying the morphology of the PDMS microstructure to achieve different sensitivities and pressure ranges for different applications41. The CPS with the sharpest microstructure shape achieved the highest sensitivity 1.713 kPa−1, and enabled a broader pressure range. Then by introducing hollow structures into the wrinkles, they further increase the air gap volume and reduce the mechanical modulus, resulting in a sensitivity up to 14.268 kPa−1 for pressure range 0–5 kPa. They demonstrated that higher pressure led to a change in the geometry of the wrinkled microstructure. The top of the microstructured CPS, which had larger air gaps, was more compressible, leading to significant capacitance changes under low pressure. However, as observed in the previously mentioned studies at higher pressures, the structure flattened, reducing compressibility and sensitivity.

Earlier work37,38,40 demonstrated that simple microstructures in the dielectric material improve sensitivity but only over a narrow low-pressure range. More advanced hierarchical micro-pyramids partly overcome this limitation42, expanding the sensing range up to 100 kPa. Herein, to expand the sensing range, they constructed a microstructure directly on the electrodes has been used as a novel and effective approach towards highly sensitive CPSs. The researchers tested the performance of flexible CPSs with three types of flexible graphene electrodes: smooth graphene electrodes (SGrE), nanostructured graphene electrodes (NGrE), and microstructured graphene electrodes (MGrE) as illustrated in Fig. 3b. The result showed that the micropattern of the electrode played a crucial role in the sensitivity of a CPS, and microstructured electrodes could cumulatively enhance sensitivity. More specifically, MGrE exhibits larger deformation under the same external loading compared to SGrE and NGrE. Additionally, they explore the performance of the MGrE towards bending stability (something important when it comes to wearables), showcasing exceptional results even after 600 bending times. Lastly, they develop a double MGR, with double microstructured electrodes used as bottom and top electrodes, with sensitivity obtained 7.68 kPa−1 - compared to 3.17 kPa−1 for the single layer, demonstrating high sensitivity in the low pressure range (0–5 kPa), which can have applications for biological research (such as insect crawling, droplets of water falling) and/or wearable monitoring of human health (e.g., pulse waveform detection). As a result, high sensitivity is required in low-pressure ranges to make accurate measurements. Herein, this 3D conformal microstructure provided a high sensitivity comparable to that of the 3D network electrode study43, resulting in a higher sensitivity compared to traditional microstructures on the dielectric layer37,38. Another study explored the possibility of achieving high sensitivity by fabricating microstructures on the electrode36. A thin dielectric layer was used to achieve a considerably smaller initial electrode distance between the electrodes compared to that achieved with a microstructured dielectric layer. PDMS pyramid arrays with different duty ratios were also fabricated. The result was an ultrasensitive, flexible CPS with a pyramidal microstructured electrode, achieved by adding elastic pyramidal microstructures on one side of the electrode and utilizing a thin layer of dielectric. Finite element analysis (FEA) of hyperelastic materials showed that the microstructures on the electrode played a key role in achieving high sensitivity. The proposed device showed significantly higher sensitivity than a CPS featuring a dielectric layer with microstructures of identical dimensions, with an ultra-high sensitivity of 70.6 kPa−1 in the wide range (0–50 kPa), low detection limit of 1 Pa and low hysteresis behavior.

Using a combination of high-conductive/durable compositing materials, they develop highly durable materials at a wide working range sensor. More specifically, a sensor was manufactured by sandwiching a carbon nanostructure dielectric layer (CNS) between polymer-based electrodes (poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly (styrene sulfonate) PEDOT:PSS, PDMS, offering ultralow pressure detection, high stability over a broad pressure range, reproducibility and scalability making the sensor suitable for practical use in diverse applications44. Poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) (PVDF-TrFE) fiber scaffolds were used to provide mechanical strength, resilience, and consistent thickness, while MXene was added to increase the dielectric constant and soften the polymer nanofibers, thereby reducing the compression modulus and enhancing sensitivity. CPSs with different concentrations of MXene exhibited different responses, with the CPS with a 5 wt% MXene load of 5 pounds showing the highest sensitivity. The sensors show good sensitivity (0.51 kPa−1), minimum detection limit 1.5 Pa and a broad pressure range (0–400 kPa). Unlike previous sensors with limited range, nonlinear stability (after multiple cycles of pressure application), and high signal distortion, this sensor maintained stable, hysteresis-free performance even under high pressure (>167 kPa), making it ideal for durable applications.

A breakthrough in tactile CPSs was made by introducing a novel dielectric layer featuring a CNT/PDMS gradient microdome architecture (GDA) with a high dielectric constant (Fig. 3c)45. Unlike traditional microstructured dielectrics, the GDA design was based on gradient microdome pixels that sequentially engaged the electrodes, enabling customization of dielectric behavior under pressure. By optimizing the arrangement and height of the microdomes, the CPS achieved an acceptable sensitivity, 0.065 kPa−1and an ultra-broad linearity range up to 1700 kPa. Furthermore, the capacitance showed minimal hysteresis during the application and release of pressure up to 7000 cycles. This ensured consistently high resolution across the pressure spectrum, making the CPS highly effective in detecting diverse physiological signals, such as artery pulses, voice vibrations, and joint motions, which are shown to be subsequently promising in applications that need sensitivity both at low (e.g., monitoring artery palse, voice vibrations) and high pressures (motions of joints).

In a related paper, they propose another way to endow high sensitivity without compromising sensitivity with increasing pressure, by the synergistic effect of a high dielectric constant and gradient microdome structures. In this work, they present an ultrasensitive flexible CPSs, based on a spontaneously wrinkled carbon nanotubes (CNT)/polydimethylsiloxane (MMWCNT/PDMS) composite dielectric layer. The combination of these wrinkled microstructures and percolating MWCNT fillers contributes to high sensitivity and linearity. Herein, they present an ultrasensitive flexible CPS, based on a spontaneously wrinkled multi-wall carbon nanotube composite dielectric layer. The combination of these wrinkled microstructures and percolating MWCNT fillers. The sensor exhibits a sensitivity of 1.448 kPa−1, with high linearity (R2 = 0.9982) in the pressure range of 0.005–21 kPa46. The sensor also showed fast response time (123 ms), good durability (5000 cycles), and a low detection limit at 0.2 Pa. The sensor was also integrated into a fully multi-material 3D printed soft pneumatic finger to realize the material hardness. contributes to ultrahigh sensitivity and linearity. Pressure sensors capable of reliable real-time monitoring of arterial pulses are of significant importance in the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease and non-invasive use.

An alternative, accurate, and fast method to prepare CPS was fabricated using laser-induced graphene (LIG) methods. An electrode with a laser-engraved microcone structure was fabricated by secondary laser engraving on wood47. Minimizing the ablative effect increased the amount of LIG produced by pretreating the wood with a flame-retardant to reduce the resistance of LIG, which was then peeled off using thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU). Overall, the fabricated CPS consisted of a LIG/TPU electrode with a microhole array, and a TPU dielectric layer with a microcone array, high sensitivity (0.11 kPa−1), an ultrawide pressure detection range (20 Pa–1.4 MPa), a fast response (300 ms), and good stability (>4000 repeatability cycles at 0–35 kPa).

In a related study, they introduced a flexible CPS with a dual dielectric layer and a multilayer microstructure48. The sensor was manufactured using a combination of template methods and electrospinning techniques to create dielectric layers and electrodes. A thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) network and silver Nanoparticles (AgNP) provided a porous structure for isolation and buffering between microstructures, while AgNP enhanced the constant of the upper dielectric layer (Fig. 3d). A PDMS-made micropillar structure improved the elasticity of the CPS and the variation of the dielectric constant during compression, contributing to 0.091 kPa−1 sensitivity over a wide detection range (1 Pa–2 MPa). Moreover, the developed sensor possesses excellent sensing performance, with a low LOD (1 Pa), fast response times (71 ms). The electrodes were made from a CNT/MXene/PDMS mixture, creating a flexible, environmentally friendly, and stable structure with no need for organic solvents. Micropyramid and microbridge structures on the electrodes improved the CPS’s sensitivity, detection range, and elasticity. The sensing mechanism was divided into three stages—slight, moderate, and significant force—corresponding to the compression of different layers, thereby achieving a high range of response in terms of pressure.

In the study of Huang et al., they present a hollow tripped microstructured dielectric layer engineering to greatly enhance sensor performance49, achieving ultrahigh sensitivity (2217 kPa−1), a wide detection range up to 1800 kPa, a low detection limit (2 Pa), and fast response/recovery times of 5.6 ms and 16.8 ms respectively. The system enables real-time, dynamic interaction, as the pressure sensor was able to identify material properties (e.g., hardness/softness) even in challenging environments such as underwater. Further demonstration in dark aquatic conditions includes Morse code and robotic material recognition, with 98% classification accuracy.

Although the creation of microstructures enhanced the sensitivity, especially in the low pressures (<10 kPa) micro-structuring37,38, hierarchical micro-pyramids has shown to be expand the sensing range up to 100 kPa40. On the other hand, electrode micro-structuring has endowed capacitive sensors with ultrahigh sensitivity36,42, there is a compromise when it comes to the sensitivity with increasing pressure36, as the sensitivity decreases dramatically as the pressure increases. It is highly desirable to develop a pressure sensor with high sensitivity and excellent linearity over a broad pressure range, especially when it comes to specific applications, for example, human motion detection. For that reason microstructure with fillers and multilayered structures has introduced and have been able to achieve ultrahigh pressure sensing, even up to 1700 kPa45. A summary of the key performance metrics (sensitivity, response time, mechanical durability, hysteresis, detection limit) is provided in Table 1.

Foams and air gap engineering

At the same time, significant progress has been made in the research of porous (foamy) microstructures. In these structures, the sensing mechanism differs: each pore behaves like a microcapacitor that deforms noticeably under compression. When pressure is applied, interfacial polarization is enhanced due to the Maxwell-Wagner effect50. This enhanced polarization leads to a substantial increase in permittivity, resulting in a significant rise in capacitance.

Park et al. show that high sensitivity (1.5 kPa−1) was achieved by incorporating a porous dielectric (PDMS) in addition an air gap (Fig. 4a), showing the possibility of fabricating highly sensitive CPSs that can distinguish various mechanical stimuli (compression, tension, bending, and vibration)51. More specifically, they report sensitivity 1.5 kPa−1 for pressures <1 kPa−1, 0.14 kPa−1,in the pressure region (1–5 kPa), the sensitivity dropped further to 0.005 kPa−1, for pressures greater than 5 kPa (became highly compressed). However, that sensor design, as a result of the finite relaxation time for the PDMS to revert to the original state after mechanical stress is released, yields slightly higher capacitance in the backward sweep than in the forward sweep. As they report, upon the release of 1 kPa and 20 kPa of pressure, the device returned to 97% of its original capacitance, which could be problematic when it comes to wearable applications.

a CPS incorporates porous PDMS and air gaps that are capable of deforming and detecting various mechanical stimuli, such as compression, tension, bending vibration, and pressure. Adapted with permission from Advanced Materials51. b Soft CPS and working principle of foam structure under pressure. Adapted with permission from Advanced Materials Technologies52.

A similar observation related to the elastomeric bulking was done by Atalay et al. who also used a foam structure to quickly and easily fabricate a flexible CPS with conductive electrodes made of fabrics and a microstructured silicone dielectric layer for wearable electronic devices (Fig. 4b)52. Specifically, they tested conductive fabrics (knitted vs. woven) and micropores created with sugar granules and salt crystals in a silicone elastomer. The knitted electrode with sugar granules has a relatively low sensitivity of 0.0121 kPa−1 and a quite linear response under ultra-wide pressure range (0–100 kPa), resulting in slightly higher hysteresis compared to previously reported micropore sensors51,53. Other important parameters, such as durability and stability under a large number of cycles, haven’t been fully investigated. A crucial parameter that wasn’t able to accurately control the size and location of the pores, leading to variations between samples owing to the uniformity of arrangement and distribution, and differences between pore-forming grains, with variations between sample to samples. A solution to the aforementioned drawback was made using a flexible fabricated CPS using highly ordered porous microstructures as the dielectric layer, using 3D printing as the core manufacturing process54. The fabrication process enabled consistent fabrication of the porous microstructure, thus ensuring overall device consistency (≤5.47% deviation among different batches of sensors). Additionally, they achieve strong bonding between the porous PDMS dielectric layer and the electrodes through oxygen plasma treatment, bonding pressure, and temperature control, significantly improving the structural robustness. The researchers of this study also tested the tunability of the CPS by varying the height, line width, and interval of its porous dielectric layer while keeping other parameters constant. A higher height or interval enhanced the sensitivity by making the dielectric layer more deformable, while a greater length reduced the sensitivity by making the dielectric layer stiffer. Consistent with simulations, these results demonstrated that performance can be optimized by adjusting the feature parameters/dimensions of the porous microstructured dielectric to meet specific needs, thereby creating a sensor with tunability and adaptability. The developed sensor showed compressibility and dynamic responses (short response and recovery times) within the pressure range (0–2 kPa) with sensitivity up to 0.21 kPa−1 and structure robustness in a broad pressure range (455.2 kPa) due to the strong bonding.

Another study explored a flexible CPS that incorporates a high-permittivity MXene/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) nanocomposite dielectric with a 3D network electrode (3DNE), aiming to achieve high sensitivity and a wide detection range43. Using a stable bulk membrane dielectric and transferring the 3DNE to the flexible electrode, the sensor achieved high stability and ultra-high sensitivity. MXene significantly improved the dielectric properties of TPU, achieving a high dielectric constant with a low loss tangent. The CPS had a sensitivity of up to 10.2 kPa−1 under pressures of up to 8.5 kPa and and still maintains a relatively high sensitivity of 3.65 kPa−1 under higher pressures (8.6–100 kPa), a detection limit of 0.17 Pa, a response time of 41 ms, and durability for over 20,000 cycles. FEA and theoretical calculations validated its mechanism, and wearable electronic applications, including pulse monitoring and pressure mapping, demonstrated its potential.

Adding air into the dielectric layer during deformation increases its dielectric constant and quickly changes the distance between the two electrode layers, and it’s a common method to improve the sensitivity. Moreover, the large number of porous inside the structures gives them sufficient elastic deformation space when an external force is applied. Therefore, a large hole with large deformation has a small compression modulus, resulting in high sensitivity. Solid foams show linear elasticity at low stresses in compression, followed by a long collapse plateau and a regime of densification in which the stress rises steeply. Earlier generations43,51,52,54 of foamy structures enhanced sensitivity but were generally restricted to the very low-pressure regime (<1 kPa). Recent composite designs, such as MXene/TPU foams43, overcome this limitation and achieve high sensitivity across a broad pressure range, up to 100 kP. The foam structure, in contrast with the micropatterned structures of the first section, has the advantage of a simple, low-cost method, whereas the microporous/micro dome method is time-consuming, where a need for micro molding using high-precision techniques to create the mold, such as lithography, additive manufacturing, chemical etching, etc. A summary of the studies of this category with performance metrics (sensitivity, response time, mechanical durability, hysteresis, detection limit) is provided in Table 2.

Ionic liquids, gels, and metal-based systems

Ionic liquids (ILs) have been explored as alternatives to conventional sensing platforms, enabling the use of conductive fluids as active sensing elements. Iontronic sensors, in particular, replace the dielectric layer in capacitive sensors with ionic materials, significantly enhancing sensitivity through the formation of a supercapacitive electric double layer (EDL) at the electrolyte-electrode interface34. In contrast to previously mentioned capacitors that modulate capacitance via changes in the distance between electrodes, iontronic capacitors generate interface capacitance only upon contact between the electrode and the ionic gel. Most flexible pressure sensors adopt a sandwich configuration comprising upper and lower electrodes with an intermediate sensing layer. This contact produces a high initial capacitance due to EDL formation, which consists of surface-bound electrons, a Helmholtz layer, and a diffuse ionic layer.

In such a study, microstructures were randomly distributed on a solid electrolyte and sandwiched between Silver Nanowires (AgNW) electrodes for pressure sensing purposes (Fig. 5a)55. The ILs were encapsulated in the polymer matrix, forming a well-defined gel-like structure through a noncovalent association with the polymer blocks. The device operated as a series of EDL capacitors with bulk resistance modeled using the Gouy-Chapman-Stern approach. Consequently, the interfaces between the AgNW/PDMS electrodes and the iontronic film at the top and bottom layers act as two interfacial layers. The sensing mechanism relied on interfacial capacitance variations caused by changes in the contact area between the interfaces based on the electric double layer (EDL) phenomenon. A microstructured iontronic film placed between two AgNW/PDMS electrodes in a parallel plate configuration deformed elastically under pressure, increasing the interfacial capacitance by enlarging the contact area. The microstructures initially had few contact points, but pressure expanded the contact area by replacing air gaps with membrane material, significantly increasing the capacitance of the EDL. The microstructured film showed greater deformation and capacitance changes than a flat film under the same pressure, resulting in ultrahigh pressure sensitivity of 131.5 kPa−1 at the low sensing range up to 2 kPa, dynamic response 43 ms, high linearity (R2 = 0.97) and a high stability over 7000 cycles.

a Polymeric matrix forming a well-defined gel-like structure with the ionotropic film in between Ag/PDMS electrodes. Adapted with permission from Applied Materials. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society55. b Icicle-shaped liquid metal and elastomer. The array sensor can detect forces on curved surfaces. Adapted with permission from Applied Materials. © American Chemical Society, 202056.

In a related study, by using a novel approach, they developed a highly stretchable and sensitive CPS array with icicle-shaped liquid metal film electrodes56. The device consisted of two stretchable elastomer layers encapsulated in liquid metal films placed orthogonally (Fig. 5b). The top electrode layer that contains an icicle-shaped liquid metal film enhances pressure sensitivity compared to conventional electrode layers. Specifically, external pressure significantly deformed the microstructure, resulting in the deformation of the embedded electrodes and leading to changes in the overlapping area and separation distance. This icicle-shaped electrode/elastomer design enabled the detection of pressures as low as 12 Pa with high sensitivity (39 kPa−1) in the range of 0–1 kPa and with 8.46% hysteresis.

The role of ionic liquids was further investigated, as the sensing element, providing a novel template synthesis method for fabricating a micropillar ionic gel film as the dielectric layer for iontronic CPS57. The micropillar ionic gel film was templated using a track-etch membrane with adjustable size and density. Unlike traditional microfabrication, this templating method is cost-effective and well-suited for large-area production. The fabricated CPS had a low detection limit (0.5 Pa), high sensitivity 14.83 kPa−1 under low pressures (0–5 kPa) and 5.73 kPa−1 under intermediate pressures (5–24 kPa), and linear sensitivity (1.96 kPa−1) over a wide range (24–230 kPa). Furthermore, screen-printed micropillar layers enabled large-area pressure arrays and pressure-mapping insoles suitable for foot diagnostics, rehabilitation training, and wearable sports electronics.

Other work in this area has found an ionic CPS that incorporated composites with microstructures made by mixing a polymer and an ionic liquid (IL), resulting in convex and randomly wrinkled microstructures forming an electrical double layer (EDL) with a thickness of several nanometers58. The sensitivity of the caoacitive oressure sensor was high, even slight variations in the contact area led to a large increase when pressure was applied, and the EDL area increased, resulting in a significant increase in the capacitance. Herein, a simple and cost-effective fabrication process was employed to create microstructures on the IL/polymer composite by stretching and treating a PDMS replica of a low-cost commercial opaque glass template. The sensor exhibited a high linear sensitivity of 56.91 kPa−1 owing to the high interfacial capacitance formed by the electrical double layer of the IL/polymer composite over a relatively wide range (0–80 kPa). FEA was used to investigate the effects of these microstructures on the CPS’s performance. The results showed that the CPS had ultrahigh linear sensitivity across a wide pressure range, overcoming the nonlinearity issues commonly observed in similar CPSs. Due to that high-linear sensitivity in a relatively wide range (0–80 kPa−1), the developed sensor can find applications in a wide and diverse application scenarios such as glove-attached sensor, sensor array, respiration monitoring mask, human pulse, blood pressure measurement, human motion detection, and a wide range of pressure sensing. As they mentioned, the proposed pressure sensor is expected to have sufficient potential for use in wearable devices.

High linearity over a broad sensing range usually comes at a cost of reduced sensitivity. To solve that issue, a programmable fabrication method for microstructures to integrate an ultrathin ionic layer was introduced. The resulting optimized sensor exhibits a sensitivity of 33.7 kPa−1 over a linear range of 1700 kPa, a detection limit of 0.36 Pa59. They create gradient pyramidal microstructures (GPM) for iontronic sensors using a CO2 laser. The use of that programmable fabrication method, create fine features, providing minized initial contact area for the sensor able to detect an ultralow pressure of 0.36 Pa, and a great resolution of 0.00725%.

A milestone was reported when they achieved ultralinearity with ultra-high sensitivity at 1439.8 kPa was achieved by placing a circle of flexible and elastic PDMS spacer around the ionic gel60. In that study, they report a millimeter-scale graded hollow ball arch (GHBA) structure, which, as they mentioned, possesses significant advantages, including significant deformation during compression and major variation in the contact area between the electrode and the ionic gel. That high deformation come due to the ionic gel film microstructure, leading to a delay in the arrival of pressure saturation.

In the same spirit as the study above, Huang et al. were able to accurately detect various motions with broad pressure ranges, using a gradient strategy of material modulus and microstructure inspired by human skin, resulting in distinct characteristics with programmable performance24. Meanwhile, the modulus gradient facilitates concentrated pressures, resulting in a quick response, resulting in superior sensitivity and a wide sensing range, achieving ultra-high sensitivity (37,347.98 kPa−1) over a sensing range of up to 151.6 kPa, making it ideal for monitoring arterial pulses and distinguishing signals from finger presses. In addition, the superior sensing capability enables accurate monitoring of dynamic high-impact motions, including boxing and plantar pressure. Here, skin-inspired gradient strategy realizes the programmable regulation of the working range and sensitivity in iontronic sensors, providing valuable design insights and broad applicability in wearable devices, healthcare, and human-machine interaction.

In summary, several iontronic pressure sensors that has been used in cooperation of microstructure and electrode designs significantly impact the performance of iontronic CPSs. Strategies like random microstructures, icicle-shaped electrodes, micropillar templating and fabrication scalability. Gradient structures outperformed others in achieving both ultrahigh sensitivity and broad sensing ranges58,60. The reviewed studies used Ionic Metals/Gels or Liquids, and their distinct quantitative metrics are summarized in Table 3.

Bioinspired designs

As discussed in the previous paragraphs, researchers have explored various strategies to mimic human skin—particularly its gradient texture—to achieve high sensitivity24. However, human skin is not the only biological structure that has inspired such designs; nature offers a wide range of models that researchers have drawn from to enhance material performance61.

Inspired by the misalignment of the differently sized teeth of a crocodile during biting, researchers wanted to develop such a sensor. As they mentioned, the structure consisted of microcolumns of varying heights, which made the CPS more bendable when compressed62. The grooves present in the substrate of the dielectric layer accommodated the compressed microcolumns, thereby endowing the CPS with high compressibility, making it suitable for pressure sensing. The medium layer consisted of micropillars and fillable pores, enabling the structure to remain even under high pressure (much higher than 100 kPa). Fine-tuning parameters such as microstructure spacing and tilt angle, and combining FEA with experimental optimization, resulted in an ultrawide pressure range of 7 Pa–380 kPa, sensitivity 0.97 kPa−1 in the range of 0–4 kPa, and good repeatability (1000 cycles). They also show short response and recovery times (65 and 85 ms, respectively), and a detection limit at 7 Pa and low hysteresis. In a similar study, they introduced a flexible CPS inspired by the biomechanics of cheetah legs63. The sensor featured an optimized bionic microstructure created by 3D printing a Polylactic Acid (PLA) mold with a cheetah leg pattern, followed by spin-coating PDMS and adding conductive silver glue for flexibility. Fine-tuning parameters such as microstructure spacing and tilt angle were optimized to achieve high sensitivity and stability, offering a promising design for advanced pressure sensing applications. The final sensor recorded high sensitivity 0.75 kPa−1, a wide linear sensing range (0–280 kPa), resulting in a slightly lower sensitivity than the previous, a slightly higher hysteresis (9.3 instead of 5.4%), however, shows greater durability (24,000 cycles).

Among animals, other researchers have been inspired by flowers as they study and explore the structure of the petals of Bamboo Leaves64 and kapok flowers65, respectively. For instance, Sun et al. they fabricate a self-healing CPS. A grating-like microstructure was introduced into the electrode by using a spotted bamboo taro leaf as a template, and a dual microstructure sensor was constructed by combining it with a microporous dielectric layer doped with single-walled carbon nanotubes. The prepared self-healing flexible sensor achieves a sensitivity of 3.6 kPa−1 up to 5 kPa pressure, a minimum detection limit of 5 Pa, a response recovery time of less than 80 ms, and stability over 5000 cycles, which exceeds most previously reported silicone rubber-based capacitive flexible sensors.

In a different study, the petals of the kapok flower exemplify the structural effect of a negative Poisson’s ratio in natural materials. The CPS was fabricated using Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D printing, which ensured high precision in shaping the sensor and endowing it with good overall performance65. Key parameters, such as the composition and structure of the dielectric layer material, were optimized to achieve high sensitivity (2.38 kPa−1 in the range of 0–10 kPa), a wide detection range (up to 734 kPa), a fast response time (23 ms) and outstanding pressure resolution (0.4% at 500 kPa).

A promising field in bio-inspired is sensors that are designed to emulate the function of tactile sensory nerves, combining both sensing and processing capabilities in a single system. Inspired by memristors, utilize CPSs integrated with flexible materials exhibiting synaptic plasticity, an ability that is crucial for the next generation of smart sensors. More specifically, they develop a capacitive sensor that differs from the traditional microstructures, introducing a high-aspect-ratio dielectric layer, similar to the hourglass-shaped surface of a starfish66. As they mentioned, the aspect ratio of the microstructures was a key determinant for precisely detecting minute pressures as low as 2.5 Pa, demonstrating a low detection limit, making it promising for applications requiring delicate signals. The sensor responds effectively to subtle pressures below 1 kPa as well as pressures up to 100 kPa, with peak sensitivity 2.81 kPa−1 and average sensitivity 2.81 kPa−1 in the low-pressure regime (0–0.5 kPa). That sensor opens the door for promising sensing properties of the capacitive tactile receptor, artificial sensory nerves, comprising this sensor, and a flexible memristor with stable short- and long-term plasticity, reliably function as highly energy-efficient near-sensor computing systems.

Considerable effort was devoted to a study to further improve sensitivity and apply it to emerging fields such as structures/materials recognition, human motion monitoring, and human-machine interaction67. Inspired by the arthropod slit sensillum, they present a biosinspired sensor fabricated by uniformly distributing a crack structure providing a stable contact interface, whereas the deformation of cracks introduces additional deformation states under pressure. The final sensor exhibited an ultra-high sensitivity of 1613 kPa−1 up to 50 kPa pressure. Moreover, the response/recovery time of the sensor is less than 130 ms, and it has been shown to detect weak signals of 6.7 Pa, maintaining a stable response up to 13,000 cycles.

In the study of Zhijie et al.68, they develop a novel ion-gel CPS inspired by the microstructure of the toe pad, which they pose concave gradient microscopic hair-like structure. A they mentioned, these microstructures enable the tree frogs to detect and distinguish subtle surface vibrations, such as irregularities or vibrations, which are crucial to precise manipulate objects and perceive the environment. Herein, they fabricate a multilayered microstructured sensor combining multiple electrode layers and materails precisely aligned such as., electrode sheets made of copper, dielectric structures, made out of ionic gel, conductive gradient microstrcutres etc. However, they used a novel method based on a magnetically induced technique. By the application of an external voltage, they form an EDLs, which they are composed of many electron-ion pairs, and subsequently, gradient microstructures are developed increasing the contact area and consequently the capacitance value at the electrode interface. The sensor developed is able to detect pressure changes with a sensitivity of 1.51 −1 over a pressure range of up to 93.5 kPa.

Summarizing, bio-inspired CPS like crocodile- and cheetah- based sensors balance compressibility and durability but trade off between hysteresis and sensitivity62,63. Kapok flower designs achieve high precision and fast response but involve complex fabrication65. Starfish-inspired sensors provide ultra-low detection limits and neuromorphic capabilities, though at the cost of increased structural and material complexity66. Therefore, each design presents trade-offs between sensitivity, range, durability, and fabrication ease and a summary of their distinct quantitative metrics are summarized in Table 4.

Multisensing and strong bonding

A considerable challenge until today, is combining a strain sensor with a pressure sensor to identify compliance, allowing the sensor to categorize and differentiate the two modes. The skin has that physical ability to comply, allowing humans through mechanoreceptors to capture different types of forces such as pressure, strain, and temperature, among other features69,70.

To overcome the difficulty of ensuring no coupling between pressure and strain signals, Wang et al. fabricated a flexible composite sensor with microstructures inspired by lotus leaves that could simultaneously detect pressure and strain with no coupling effect71. Having a wide base and a narrow top, the lotus leaf-inspired microstructure concentrated stress at the tip (Fig. 6a). Then, by introducing microstructure into both the upper and lower electrode layers, allowing double mechanical deformation and further enhance the sensor’s sensitivity and measurement range. The electrode layer of the capacitance sensor was Au-coated PDMS with a lotus leaf-like microstructure, and the resistance strain sensor was independent of the electrode layer of the capacitance sensor. The sensor showed pressure sensitivity up to 0.784 kPa−1 under pressures of less than 100 kPa, with wide pressure range (up to 800 kPa) and strain sensitivity (gauge factor of 4.03 under 0–40% strain) and could identify materials, ensuring simultaneous detection of pressure and deformation (strain). The sensor also shows good response times and exceptional durability, withstanding 10,000 cycles. This study suggests a multifunctional sensor design where the same electrode material is used for both capacitive and resistive sensing, possibly for applications in flexible electronics or bio-sensing. The composite sensor had a tensile strain of up to 150%, which is suitable for detecting various physiological stimuli, such as pulse, vibration of the vocal cord, and finger bend, and to identify the materials of various objects with tactile functions similar to those of the human skin. Such flexible composite sensor designs could also be used in intelligent prostheses for disabled patients.

a Flexible CPS with microstructures inspired by lotus leaves that can simultaneously detect pressure and strain. Adapted with permission from Advanced Healthcare Materials. John Wiley and Sons, 202371. b Hybrid interface consisting of a biocarbon composite and silver-plated nylon inspired by a combination of the characteristics of electronic skin and electronic textiles Adapted with permission from Applied Materials. © American Chemical Society, 201972.

Another study that addresses the challenge of distinguishing between multiple stimuli was conducted by Tolvanen et al. who proposed a structural design inspired by combining the characteristics of electronic skin and electronic textiles into a hybrid interface consisting of a stencil-printed biocarbon composite and silver-plated nylon (Fig. 6b)72. The resulting stretchable CPS was highly sensitive and tolerant to strains induced by stretching and bending. Its relative resistance change was more than 1000 times larger under normal pressure than during tensile or bending stress. The sensor had exceptional performance with The device is capable of providing resistivity switching under compressive stress corresponding to a pressure sensitivity up to 60.8 kPa−1 at 50 kPa pressure with a wide dynamic range (up to 100 kPa). Moreover, the resistivity switching thresholds were controlled by variations in the thickness of the biocarbon film. The device was also capable of accurate strain sensing, suitable for human motion monitoring.

In a recent study, they developed fully 3D printed soft capacitive sensors, with microstructured dielectrics and 3D technologies to improve sensitivity. Herein, they develop a multi-material 3D printed fabricated silicone-based capacitive sensor, with an optimal programmable design capable of effectively resisting delamination and debonding under twisting and compression73. In addition, the structural parameters have been carefully designed and optimized to prevent the top and/or the title thin plates from collapsing. In this study, because the conductive silicone and the dielectric silicone used have a similar Young modulus and the same Poisson ratio, the sensor does not suffer from mechanical mismatch issues. These two factors contribute to the wide detection range of the sensor. Additionally, the sensors demonstrate a broad measurement range from 0.85 to 5000 Pa.

Another feature of the skin, highly desirable in wearable sensors, is the ability to possess a multilayer structure, consisting of epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat layers that grow together to have tough interfaces can survive during manipulation tasks which involve complex mechanical modes, such as stretching, torsion, shear, and compression. By contrast, sensors that are usually composed of two electrodes and soft dielectrics suffer from poor interfacial adhesion and mechanical mismatch. In a recent study, the authors address this issue by using a quasi-homogeneous composition and introducing interlinked and microstructured interfaces74.The PDMS-CNTs electrode (7wt% CNTs) serves as a bimodal sensor for strain and pressure. It shows a constant gauge factor of 2.5 over 0–60% strain and can stretch up to 160%, with high repeatability over 10,000 cycles, indicating low hysteresis. In pressure mode, it exhibits a sensitivity of 0.04 kPa−1, at 450 kPa, with high linearity. In another recent study, they mentioned that most CPSs suffer from slow response-relaxation speed, and thus do not detect dynamic stimuli or high-frequency vibrations. So, by their approach, they further reduce the response and relaxation time of the sensors. By a bonded microstructured interface that effectively diminishes interfacial friction and energy dissipation. As mentioned, sensors are a class of the most widely studied sensing devices that can detect static pressure; however, these devices perform poorly in responding to dynamic stimuli. This limitation seems to be unreconcilable as long as viscoelastic materials are used and interfacial gaps persist75. They present a strategy for downscaling the response-relaxation time of flexible CPSs. By taking into account all the parameters, they conclude that the design can simultaneously achieve low energy dissipation, high sensitivity, and high mechanical stability. Also, as they mentioned previously, the viscoelastic materials are well-known for their energy dissipation. To reduce the viscosity of the dielectric, they employed crosslinked PDMS with a curing agent ratio of CNT filler. The all-soft sensor demonstrates a linear sensitivity of 0.007 kPa−1 with a high correlation coefficient, R2 ≈ 0.984, across a pressure range up to 100 kPa. It features a fast response time of <80 ms and is capable of detecting micro-pressure under loading pressures as low as 50 kPa. The sensor also shows strong repeatability and durability, maintaining stable performance over 10,000 loading cycles at 50 kPa. These characteristics make it well-suited for reliable and responsive pressure sensing applications. Table 5 lists the studies discussed above along with their respective metrics.

Discussion

Multifunctional wearables are emerging as powerful platforms for human motion monitoring, intelligent disease diagnosis, medical treatment, electronic skin technologies, and human-machine interfaces. Despite significant progress, a major challenge remains: achieving both high sensitivity and a broad sensing range to capture the full spectrum of human movements. Many of these applications require ultrahigh sensitivity to detect weak stimuli, such as pulse waves, in the subtle pressure regime of 1 Pa to 1 kPa, as well as sufficient flexibility and conformability to monitor motion at curved joints (e.g., knee bending, muscle activity). Others, such as robotic tactile systems or prosthetic limbs, demand accurate sensing at much higher pressures (>100 kPa). The diverse range of applications and associated pressure requirements are summarized in Table 6.

Wearable sensors capable of real-time motion tracking can also provide feedback to help users maintain correct posture or improve exercise form24,60, in addition to recording daily activities24. Many CPS designs reviewed here have demonstrated the ability to capture cardiovascular information such as pulse waveforms, which are important for assessing cardiovascular health, predicting posture-related risks, and enabling early intervention. Cardiovascular physiological and pathological changes alter the shape and amplitude of pulse wave signals, making the development of high-fidelity pulse sensors a clinical priority. Studies have shown that pulse waveforms can be reliably captured when sensors are positioned at the wrist, elbow, carotid artery, or temporal artery24,36,40,44,46,55,57,58,66,71.

Beyond healthcare, CPSs have been deployed in workplace ergonomics to prevent musculoskeletal disorders by tracking posture in desk-based occupations56,60,62,63. They are also applied in human-machine interfaces, for example, detecting facial expressions such as smiles55, or as part of more complex HMI systems23,24,59,62,63,73. Wearable CPSs have been integrated into gloves42,48,52,58,62,63,65, upper limbs47,62,63,65, lower limbs47,62,63,65, and smart shoes57,62,63,65. In one notable example, a 4 × 4 tactile sensing array integrated into a smart insole enabled plantar pressure mapping for gait pattern analysis, detection of abnormalities such as flatfoot, and rehabilitation monitoring after stroke48. Wireless transmission enabled real-time analysis, supporting applications such as fall prevention.

In surgical and critical care contexts, wearable CPSs can also provide precise intraoperative and postoperative pressure monitoring. For instance, Zhang et al.75 developed a wireless, compact, all-soft sensing system for hemostasis devices, enabling accurate adjustment of radial artery compression to reduce bleeding and complications after catheter-based interventions.

Additionally, in rehabilitation, current clinical tools such as MRI and ultrasound provide only intermittent snapshots of tissue status. Implantable sensors could offer continuous, real-time monitoring of tissue strain during rehabilitation, enabling personalized protocols based on the tissue’s tolerance75. Presently, many rehabilitation programs rely on conservative timelines with large safety margins, which can slow recovery and increase costs. Zhang et al.75 proposed a CPS-based implantable sensor to track tendon healing in real time, enabling adaptive rehabilitation.

Existing implantable sensors often suffer from limited biocompatibility or are designed for laboratory rather than clinical use. Boutry et al.39 addressed this by developing a fully biodegradable pressure and strain sensor that degrades after its functional lifetime, removing the need for secondary surgery.

Compared to piezoelectric34 and piezoresistive76 pressure sensors, CPSs are structurally simpler, inherently stable, less prone to signal drift, and consume less power77. However, CPSs are often non-linear across wide measurement ranges78, limiting their utility in applications requiring consistent sensitivity across different pressures. Multiple strategies have been developed to address this limitation, including microstructured surfaces such as micropyramids37,38,40 and microdomes47,58, as well as gradient and hierarchical designs59 (Fig. 7).

Sensitivity enhancement in pressure sensors can be achieved through multiple approaches. Structural engineering strategies include the introduction of microstructures, such as micro-pyramids37,38, microcones45,46,74, spacers or air gap engineering51 foams43,51,52,54, gradient microstructures59, multilayer designs (such as double layers)42, and bioinspired structures62,63, to increase deformability and enhance pressure sensitivity, among other structural arrangements.

Microstructured designs offer excellent compressibility and high sensitivity at low pressures, although performance can decline at higher pressures when the features deform fully. In contrast, foams can sustain larger deformations but often suffer from variability in pore structure.

For textile applications, an optimal CPS design must balance high sensing performance with integration factors such as scalability, biocompatibility, and fabrication complexity. To assess this balance, we applied the dual axis trade-off analysis introduced in the Methods (Fig. 8), plotting the normalized sensitivity against the pressure range (a), and against the TSS (b).

a Normalized pressure range vs. normalized sensitivity highlights sensors with high raw sensing capabilities. b Textile suitability score vs. normalized sensitivity captures broader integration-relevant factors. The textile suitability score was calculated as the average of nine normalized attributes: sensitivity, pressure range, scale of biocompatibility, safety, scalability, inverse fabrication complexity, inverse response time, cyclic stability, and whether the sensor was tested under both pressure and strain. Qualitative attributes were converted into ordinal values prior to normalization, and inverse normalization was applied to attributes where lower values are preferred. Sensors closest to the top-right “ideal” region in each plot are circled to indicate the most balanced candidates for textile-integrated applications. Note “a.u.” stands for arbitrary units.

The resulting plots (Fig. 8a) show that Ionic Metals dominate in raw performance, achieving both high sensitivity and broad pressure ranges. However, their integration readiness is limited by challenges in scalability and textile compatibility. By contrast, Fig. 8b reveals a more nuanced picture: Microstructuring achieves the closest single-device performance-to-integration balance, while Multisensing and strong bonding demonstrates a strong cluster of candidates with consistently high TSSs. This divergence highlights the difference between technologies that excel at producing exceptional individual devices versus those that, on average, provide more robust integration performance across multiple attributes.

In comparison, Foams and Bioinspired designs rank lower in TSS because of reproducibility challenges, narrower stability windows, and incomplete validation under textile-relevant conditions. Taken together, the analysis indicates that while Ionic Metals remain promising if integration challenges can be addressed, the most immediate pathway for textile deployment lies in Multisensing and strong bonding designs, with Microstructuring also representing a compelling option when sensitivity and geometry tunability are prioritized.

Overall, these results suggest that no single category fully dominates across both axes. Instead, progress will likely come from hybrid strategies that combine structural patterning (e.g., microstructuring) with material-level innovations (e.g., multisensing and strong bonding) to deliver high sensitivity, wide pressure range, durability, and manufacturability in a single platform.

Methods

Literature Search and Inclusion Criteria

The study identification process was conducted in line with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility in how source studies were selected. We searched PubMed and Embase, and performed additional searches in Google Scholar and other sources, including reference lists of included articles, covering publications from 1 January 2015 to 1 January 2025.

PubMed searches combined MeSH terms with relevant keywords:

(capacitive pressure sensor) AND (sensitivity improvement) AND (microstructure) AND (wearable) NOT (piezoelectric)

Embase searches combined Emtree terms and keywords:

(capacitive) AND (sensitivity) AND (microstructure) AND (pressure)

Filters applied: English language, peer-reviewed primary research, and studies involving devices for wearable or bio-health contexts. Review articles, conference abstracts without full text, and studies lacking quantitative performance metrics were excluded.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (M.P. and M.E.), with disagreements resolved by discussion. Eligible studies were then included for quantitative and qualitative data extraction.

Data extraction

For each included study, we extracted quantitative metrics:

-

Sensitivity (kPa−1)

-

Pressure range (kPa)

-

Detection limit (Pa)

-

Response time (ms)

-

Hysteresis (%)

-

Cyclic stability (number of cycles)

and qualitative attributes:

-

Biocompatibility

-

Safety for skin contact

-

Scalability of fabrication

-

Fabrication complexity

-

Whether the device was tested under both pressure and strain

Quantitative data were obtained directly from the text or tables, or extracted from figures using digital measurement tools when not explicitly stated.

Qualitative attribute scoring

Biocompatibility, scalability, and fabrication complexity were evaluated using a five-point ordinal scale: Low (0), Low to Moderate (1), Moderate (2), Moderate to High (3), and High (4).

-

Biocompatibility: Determined from reported material toxicity, encapsulation needs, and compliance with skin-contact or implant-grade standards.

-

Scalability: Based on demonstrated compatibility with industrial-scale fabrication (e.g., roll-to-roll printing, screen printing) and reported production volumes.

-

Fabrication complexity: Inversely scored according to the number of fabrication steps, requirement for specialized equipment, and ease of process reproducibility.

Detailed definitions for each qualitative category are provided in Supplementary Tables S1 to S4.

Data normalization

To enable cross-comparison, all quantitative metrics were normalized to a 0–1 scale using min–max normalization:

For attributes where lower values were preferable (fabrication complexity, response time), inverse normalization was applied:

Textile Suitability Score (TSS) Calculation

The TSS was computed as the unweighted average of nine normalized attributes:

-

1.

Sensitivity

-

2.

Pressure range

-

3.

Biocompatibility score

-

4.

Safety (binary: yes = 1, no = 0)

-

5.

Scalability score

-

6.

Inverse fabrication complexity

-

7.

Inverse response time

-

8.

Cyclic stability

-

9.

Tested under both pressure and strain (binary: yes = 1, no = 0)

The TSS formula is:

where \({\tilde{x}}_{i}\) represents the normalized (and if necessary, inversely normalized) value for each attribute.

Data analysis and visualization

Data analysis and visualization were conducted in Python (v3.10) using numpy, pandas, and matplotlib. Trade-off plots compared (a) normalized sensitivity vs. normalized pressure range, and (b) TSS vs. normalized sensitivity, to reveal differences between raw performance rankings and integration-oriented rankings.

Data availability

This article reports a systematic review and did not generate new primary datasets. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30042259.

Change history

10 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00070-x

References

Duking, P., Hotho, A., Holmberg, H.-C., Fuss, F. K. & Sperlich, B. Comparison of non-invasive individual monitoring of the training and health of athletes with commercially available wearable technologies. Front. Physiol. 7, 71 (2016).

Sun, W. et al. A review of recent advances in vital signals monitoring of sports and health via flexible wearable sensors. Sensors 22, 7784 (2022).

Mishra, R. B., El-Atab, N., Hussain, A. M. & Hussain, M. M. Recent progress on flexible capacitive pressure sensors: From design and materials to applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 2001023 (2021).

Gan, T. Capacitive flexible pressure sensors and their application. E3S Web of Conferences 553, 05038 (2024).

Fang, C., Fu, T. & Shi, Y. Flexible capacitive pressure sensors and their applications in human-machine interactions. In 2023 2nd International Symposium on Sensor Technology and Control (ISSTC), 196–200 (IEEE, 2023).

Chugh, V., Basu, A., Kaushik, A. & Basu, A. K. E–skin–based advanced wearable technology for health management. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 5, 100129 (2023).

Dolbashid, A., Mohktar, M., Muhamad, F. & Ibrahim, F. Potential applications of human artificial skin and electronic skin (e-skin): A review. Bioinspired, Biomim. Nanobiomater. 7, 1–12 (2017).

Pierre Claver, U. & Zhao, G. Recent progress in flexible pressure sensors based electronic skin. Adv. Eng. Mater. 23, 2001187 (2021).

Zhuo, F. et al. Advanced morphological and material engineering for high-performance interfacial iontronic pressure sensors. Adv. Sci. 12, 2413141 (2025).

He, R. et al. Flexible miniaturized sensor technologies for long-term physiological monitoring. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 20 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. Polyelectrolyte elastomer-based ionotronic electro-mechano-optical devices. Small e2502225 https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202502225 (2025).

Li, S. et al. Structural electronic skin for conformal tactile sensing. Adv. Sci. 10, 2304106 (2023).

Lee, B.-Y. et al. Human-inspired tactile perception system for real-time and multimodal detection of tactile stimuli. Soft Robot. 11, 270–281 (2023).

Xu, T. et al. High resolution skin-like sensor capable of sensing and visualizing various sensations and three dimensional shape. Sci. Rep. 5, 12997 (2015).

Lin, W. et al. Skin-inspired piezoelectric tactile sensor array with crosstalk-free row+column electrodes for spatiotemporally distinguishing diverse stimuli. Adv. Sci. 8, 2002817 (2021).

Shyti, R., Nays, P., Vargiolu, R. & Zahouani, H. An innovative wearable device for sensing mechanoreceptor activation during touch. Sci. Rep. 15, 9986 (2025).

Rodgers, M. M., Pai, V. M. & Conroy, R. S. Recent advances in wearable sensors for health monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 15, 3119–3126 (2015).

Meng, K. et al. Wearable pressure sensors for pulse wave monitoring. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109357 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. A skin-inspired tactile sensor for smart prosthetics. Sci. Robot. 3, eaat0429 (2018).

Shih, B. et al. Electronic skins and machine learning for intelligent soft robots. Sci. Robot. 5, eaaz9239 (2020).

Roberts, P., Zadan, M. & Majidi, C. Soft tactile sensing skins for robotics. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2, 343–354 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Skin-inspired high-performance e-skin with interlocked microridges for intelligent perception. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2412065 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Pushing pressure detection sensitivity to new limits by modulus-tunable mechanism. Adv. Sci. 11, 2403779 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Programmable high-sensitivity iontronic pressure sensors support broad human-interactive perception and identification. npj Flex. Electron. 9, 41 (2025).

Luo, J., Zhang, L., Wu, T., Song, H. & Tang, C. Flexible piezoelectric pressure sensor with high sensitivity for electronic skin using near-field electrohydrodynamic direct-writing method. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 48, 101279 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Flexible piezoelectric-induced pressure sensors for static measurements based on nanowires/graphene heterostructures. ACS Nano 11, 4507–4513 (2017).

Min, S. et al. Clinical validation of a wearable piezoelectric blood-pressure sensor for continuous health monitoring. Adv. Mater. 35, 2301627 (2023).

Cao, M. et al. Wearable piezoresistive pressure sensors based on 3d graphene. Chem. Eng. J. 406, 126777 (2021).

Zong, X., Zhang, N., Ma, X., Wang, J. & Zhang, C. Polymer-based flexible piezoresistive pressure sensors based on various micro/nanostructures array. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 190, 108648 (2025).

Ji, F. et al. Flexible piezoresistive pressure sensors based on nanocellulose aerogels for human motion monitoring: a review. Compos. Commun. 35, 101351 (2022).

Alghrairi, M. et al. Advancing healthcare through piezoresistive pressure sensors: a comprehensive review of biomedical applications and performance metrics. J. Phys. Commun. 8, 092001 (2024).

Ha, K.-H., Huh, H., Li, Z. & Lu, N. Soft capacitive pressure sensors: trends, challenges, and perspectives. ACS Nano 16, 3442–3448 (2022).

Tressler, J. F., Alkoy, S. & Newnham, R. E. Piezoelectric sensors and sensor materials. J. Electroceram. 2, 257–272 (1998).

Zhi, C. et al. Recent progress of wearable piezoelectric pressure sensors based on nanofibers, yarns, and their fabrics via electrospinning. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2201161 (2023).

Chen, K.-Y. et al. Recent progress in graphene-based wearable piezoresistive sensors: from 1d to 3d device geometries. Nano Mater. Sci. 5, 247–264 (2023).

Li, M., Liang, J., Wang, X. & Zhang, M. Ultra-sensitive flexible pressure sensor based on microstructured electrode. Sensors 20, 371 (2020).

Mannsfeld, S. et al. Highly sensitive flexible pressure sensors with microstructured rubber dielectric layers. Nat. Mater. 9, 859–64 (2010).

Boutry, C. M. et al. A sensitive and biodegradable pressure sensor array for cardiovascular monitoring. Adv. Mater. 27, 6954–6961 (2015).

Boutry, C. et al. A stretchable and biodegradable strain and pressure sensor for orthopaedic application. Nat. Electron. 1, 314–321 (2018).

Cheng, W. et al. Flexible pressure sensor with high sensitivity and low hysteresis based on a hierarchically microstructured electrode. IEEE Electron Device Lett. PP, 1–1 (2017).

Zeng, X. et al. Tunable, ultrasensitive, and flexible pressure sensors based on wrinkled microstructures for electronic skins. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 21218–21226 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Flexible, tunable and ultrasensitive capacitive pressure sensor with micro-conformal graphene electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 14997–15006 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Highly sensitive capacitive flexible pressure sensor based on a high-permittivity mxene nanocomposite and 3d network electrode for wearable electronics. ACS Sens. 6, 2630–2641 (2021).

Sharma, S., Chhetry, A., Sharifuzzaman, M., Yoon, H. & Park, J.-Y. Wearable capacitive pressure sensor based on mxene composite nanofibrous scaffolds for reliable human physiological signal acquisition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 22212–22224 (2020).

Ji, B. et al. Gradient architecture-enabled capacitive tactile sensor with high sensitivity and ultrabroad linearity range. Small 17, 2103312 (2021).

Lv, C. et al. Ultrasensitive linear capacitive pressure sensor with wrinkled microstructures for tactile perception. Adv. Sci. 10, e2206807 (2023).

Qu, C. et al. Flexible microstructured capacitive pressure sensors using laser engraving and graphitization from natural wood. Molecules 28, 5339 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Capacitive pressure sensor combining dual dielectric layers with integrated composite electrode for wearable healthcare monitoring. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c01042 (2024).

Huang, C., Wang, P., Niu, H., Gong, N. & Li, Y. Integrated intelligent material recognition and information exchange platform based on a highly sensitive flexible pressure sensor and electroluminescent display. ACS Sens. 10, 4336–4347 (2025).

Sikiru, S., Yahya, N., Soleimani, H., Ali, A. M. & Afeez, Y. Impact of ionic-electromagnetic field interaction on maxwell-wagner polarization in porous medium. J. Mol. Liq. 318, 114039 (2020).

Park, S. et al. Stretchable energy-harvesting tactile electronic skin capable of differentiating multiple mechanical stimuli modes. Adv. Mater. 26, 7324–7332 (2014).

Atalay, O., Atalay, A., Gafford, J. & Walsh, C. A highly sensitive capacitive-based soft pressure sensor based on a conductive fabric and a microporous dielectric layer. Adv. Mater. Technol. 3, 1700237 (2018).

Xu, P., Li, X. & Yu, H. Transducers-2015 18th international conference on solid-state sensors, actuators and microsystems (transducers). (IEEE, 2015).

Li, Z. et al. Sensitive, robust, wide-range, and high-consistency capacitive tactile sensors with ordered porous dielectric microstructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 7384–7398 (2024).

Chhetry, A., Kim, J., Yoon, H. & Park, J. Y. Ultrasensitive interfacial capacitive pressure sensor based on a randomly distributed microstructured iontronic film for wearable applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 3438–3449 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Highly stretchable and sensitive pressure sensor array based on icicle-shaped liquid metal film electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 27961–27970 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Wang, T., Zhao, Z. & Wang, Q. Track-etch membranes as tools for template synthesis of highly sensitive pressure sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 1791–1799 (2021).

Cho, C., Kim, D., Lee, C. & Oh, J. Ultrasensitive ionic liquid polymer composites with a convex and wrinkled microstructure and their application as wearable pressure sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 13625–13636 (2023).

Yang, R. et al. Iontronic pressure sensor with high sensitivity over ultra-broad linear range enabled by laser-induced gradient micro-pyramids. Nat. Commun. 14, 2907 (2023).

Ding, Z. et al. Highly sensitive iontronic pressure sensor with side-by-side package based on alveoli and arch structure. Adv. Sci. 11, 2309407 (2024).

Xin, Q. et al. Advanced bio-inspired mechanical sensing technology: Learning from nature but going beyond nature. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2200756 (2023).

Hong, W. et al. Bioinspired engineering of fillable gradient structure into flexible capacitive pressure sensor toward ultra-high sensitivity and wide working range. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 44, 2300420 (2023).

Hong, W. et al. Flexible capacitive pressure sensor with high sensitivity and wide range based on a cheetah leg structure via 3d printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 46347–46356 (2023).

Sun, P. et al. Microstructured self-healing flexible tactile sensors inspired by bamboo leaves. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 60699–60714 (2024).

Jin, Q. et al. 3d printing of capacitive pressure sensors with tuned wide detection range and high sensitivity inspired by bio-inspired kapok structures. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 45, e2300668 (2024).

Cho, J.-Y. et al. Tactile near-sensor computing systems incorporating hourglass-shaped microstructured capacitive sensors for bio-realistic energy efficiency. npj Flex. Electron. 9, 34 (2025).

Wang, D. et al. Capacitive pressure sensors based on bioinspired structured electrode for human-machine interaction applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 271, 117086 (2025).

Zhijie, X. et al. Ion gel pressure sensor with high sensitivity and a wide linear range enabled by magnetically induced gradient microstructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 17, 12720–12730 (2025).

Chortos, A., Liu, J. & Bao, Z. Pursuing prosthetic electronic skin. Nat. Mater. 15, 937–950 (2016).

Macefield, V. G. The roles of mechanoreceptors in muscle and skin in human proprioception. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 21, 48–56 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Composite flexible sensor based on bionic microstructure to simultaneously monitor pressure and strain. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12, e2301005 (2023).

Tolvanen, J., Kilpijärvi, J., Pitkänen, O., Hannu, J. & Jantunen, H. Stretchable sensors with tunability and single stimuli-responsiveness through resistivity switching under compressive stress. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 14433–14442 (2020).

Xiao, F. et al. Fully 3d-printed soft capacitive sensor of high toughness and large measurement range. Adv. Sci. 12, 2410284 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Highly stable flexible pressure sensors with a quasi-homogeneous composition and interlinked interfaces. Nat. Commun. 13, 1317 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Wireless, smart hemostasis device with all-soft sensing system for quantitative and real-time pressure evaluation. Adv. Sci. 10, 2303418 (2023).