Abstract

While printed electronic sensors present significant opportunities for the Internet of Things (IoT), industrial-scale production of these devices also raises numerous environmental concerns, including electronic waste generation and critical mineral depletion. Here, we circumvent these issues by demonstrating high-performance biodegradable printed electronic sensors based exclusively on agripaper substrates and graphene inks sourced from biomass. The agripaper substrate is produced from miscanthus and hemp, which are hardy, drought-tolerant agricultural crops. Meanwhile, the sensing layer is composed of cellulose nanocrystals derived from miscanthus, and graphene nanoplatelets derived from hardwood biochar. These plant-based printing materials are renewable, biodegradable, and readily processable at scale. The resulting printed electronic sensors exhibit superlative humidity sensitivity, showing a relative resistance change of 2.6 over a humidity range of 35–85% RH with response and recovery times of ~1 second and ~4 seconds, respectively. These sensors also perform well under humidity cycling and possess minimal confounding temperature dependence, outperforming traditional devices based on plastic substrates and metallic inks. By utilizing biomass for all raw materials, this additive manufacturing methodology is sustainable, minimizes supply chain risks, and provides an enabling step towards a circular bioeconomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Printed electronics offer vast opportunities in a variety of industries, including the Internet of Things (IoT)1, environmental monitoring in agriculture2, point-of-care sensing in healthcare3,4, smart packaging for sensitive goods5, and RFID tags for logistical tracking6. Simultaneously, advances in additive manufacturing have resulted in dramatic increases in production throughput, thereby driving down the cost of printed electronic devices through economies of scale7. However, mass-produced electronics present environmental concerns at every stage of their life cycle—from the environmental burden of critical mineral extraction to high energy consumption during production to vast electronic waste generation in landfills and oceans. In a future where sensor networks are projected to become increasingly ubiquitous, these negative outcomes will be further exacerbated8,9. Since sustainability and recyclability are not typically included in the design criteria of electronics10, few options currently exist for fully biodegradable printed electronic materials and devices11,12,13.

Biomass-derived materials have the potential to replace all components of highly functional printed electronic devices. From the perspective of sustainability, plant-based materials are renewable, biodegradable, and can enable a circular bioeconomy14,15. Toward these ends, here we produce high-performance printed electronic sensors from two types of repurposed biomass: (1) agricultural fibers including crop residues; (2) hardwood biochar from the biofuel industry (Fig. 1). These materials can be sourced from local waste streams to produce sustainable substrates and printable inks, achieving comparable or better printed electronic sensing performance compared to their non-plant-based counterparts. Specifically, we employ an agripaper substrate produced from minimally processed, local agricultural fibers. The electronic sensing layer is printed from a composite ink that utilizes conductive graphene nanoplatelets and cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), both derived from biorenewable plant-based raw materials. Not only is cellulose the most abundant biopolymer on earth16, it is also highly sensitive to humidity because of its abundant hydrophilic hydroxyl groups17,18. Hence, our electronic sensing layer is particularly well-suited for humidity detection, requiring only a thin trace of the graphene-CNC composite that is deposited by aerosol jet printing (AJP) on agripaper substrates with no further heat treatments or post-processing.

AJP has emerged as a versatile technique for the deposition of 2D materials, including graphene and related nanomaterials, enabling the fabrication of high-resolution electronic devices on a variety of substrates. For example, prior studies have demonstrated the successful use of AJP for patterning graphene-based immunosensors and electrochemical sensors, achieving fine feature sizes and robust device performance3,5. AJP was chosen as the fabrication method for this work because of its ability to deposit precise amounts of material on diverse substrates and its compatibility with a large range of ink viscosities19.

Humidity sensors are valuable in many industries, including indoor climate control, transportation and storage of goods, agriculture, healthcare monitoring, and manufacturing process control20. These applications benefit from widespread distribution of sensors that provide high-resolution spatial data of the moisture content throughout an area, population, or process. For example, precision agriculture and hydroponics require dense sensor networks distributed over a wide space to monitor the moisture and conditions of growth media. In turn, the resulting data can guide automated precision irrigation systems and enable powerful artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) analysis tools for growth optimization21,22. The field of smart packaging can also benefit from widely deployed humidity sensors to monitor sensitive goods in storage or during shipment. Paper-based substrates further allow seamless integration into packaging and offer a low-impact, benign, and disposable sensor platform23,24.

Our sensors are highly responsive to humidity changes due to significant swelling of the hydrophilic, CNC-containing films upon water absorption (Fig. 2). At low humidity, the as-printed dense graphene nanoplatelet film provides a highly percolating conductive network that possesses a relatively low measured resistance. As the CNC-graphene film swells upon water absorption25, electronic percolation through the graphene nanoplatelet network is perturbed, resulting in increases in the measured resistance. The net effect is that the humidity sensors in this work show comparable or better performance to previously reported sensors based on non-bioderived carbon/polymer composites26,27,28. Moreover, our humidity sensors derived entirely from biomass exceed the performance of analogous sensors utilizing plastics, silver nanoparticles, and other non-plant-based materials. Ultimately, we achieve superlative sensing performance by tuning the agripaper substrate roughness, surface hydrophobicity, and ink composition to attain optimal print morphology and humidity sensitivity.

At low humidity, the as-printed dense graphene nanoplatelet film forms a highly percolating conductive network with relatively low measured resistance. As the CNC-graphene film swells upon water absorption, the conductive pathways through the percolating network are hindered, resulting in increased measured resistance.

Conventional materials for printed electronics, such as glossy papers, plastics, and silver-based inks, are often chosen because of their advantageous properties and wide availability. Indeed, all previously published printed humidity sensors use one or more of these non-recyclable components despite their negative implications for electronic waste as the printed electronics field grows9. Since our plant-based sensors are sourced from regenerative biomass and are compostable at end-of-life, they produce virtually no waste and complete a circular economy framework. Moreover, value-added products that repurpose conventional waste materials further accelerate the adoption of a bioeconomy infrastructure by providing economic incentives to manufacturers to divert waste from landfills16,29,30,31,32,33. These plant-based devices can also be sourced and manufactured locally, supporting distributed manufacturing and eliminating supply chain risks. Overall, this work produces highly functional printed electronic sensors entirely from biomass in a manner that maximizes sustainability, scalable manufacturing, and humidity detection performance.

Results

Agripaper substrate

Due to the rapid turnover rate of consumer electronics, the identification of sustainable materials for printed devices is an active research area11,15,34,35. While electronic inks are often the target of these studies, the substrate is also critical as it constitutes the majority of the mass and volume of a printed device and can thus play a dominant role in determining end-of-life outcomes36,37. While plastics are durable and inexpensive, they are non-biodegradable, petroleum-based products that are a significant source of pollution38,39. Therefore, substantial incentives exist to move the printed electronics field towards sustainable, paper-based substrates40,41. Towards this end, we use local agricultural fibers to produce agripaper substrates that are subsequently treated with a thin cellulose-based coating to yield a smooth, printable surface.

Miscanthus (Miscanthus x giganteus) and hemp (Cannabis sativa) fibers are used to produce our agripaper because they are hardy, fast-growing crops that do not require irrigation42,43. In particular, miscanthus is a perennial grass that can grow up to 12 feet tall in only 2 years. It is typically farmed as a biofuel feedstock and boasts a significantly higher biomass yield per acre than both pine and switchgrass44,45. It also contributes to building soil carbon stores46. Meanwhile, hemp is one of the strongest natural fibers with an exceptionally high cellulose yield that is typically ready to harvest within three months of seeding47,48. To produce our agripaper, miscanthus and hemp fibers were chipped, cooked in a mild sodium carbonate solution, beaten to form a pulp, and then pressed into sheets of paper with tunable thickness49.

The basic steps of agripaper production are akin to industrial papermaking, but with a few key differences. When producing pulp from hardwood trees via the Kraft process, harsher chemicals (e.g., NaOH and Na2S) are required to break down and de-lignify the fibers, a bleaching step is performed to brighten the pulp to consumer standards, and chemical sizing and fillers are added to enhance paper properties and appearance50. As a result, industrial hardwood paper mills generate massive quantities of toxic wastewater that contains the byproducts of delignification and bleaching51,52. In contrast, non-wood fibers like miscanthus and hemp contain less lignin and require significantly milder chemicals to process47,53,54. While it is more difficult to produce bright papers using agricultural fibers due to their resistance to bleaching55,56, this limitation is largely irrelevant for printed electronics where aesthetic considerations do not affect functional performance.

Despite their sustainable production advantages, agripapers are rarely used in printed electronics due to challenges associated with printing on untreated paper. For example, the rough surface, porous matrix, and liquid absorption propensity of agripapers compromise print quality23,57. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of both our raw agripaper (Fig. 3a) and commercial printer paper (Fig. S1) reveal significant surface roughness resulting from the constituent fibers. Since cellulose is also naturally hydrophilic, chemical sizings such as alkyl-ketene dimer (AKD) are typically added to industrial pulps to make paper surfaces more hydrophobic and amenable to printing58. Nevertheless, since achieving high-quality prints on traditional paper remains challenging, previously published paper-based printed electronics almost exclusively use “photographic glossy paper,” which contains multiple coatings to improve ink interactions and print resolution28,59. These high-quality glossy papers first contain a polyethylene encapsulation layer, which prevents the ink from seeping into the fiber matrix. In addition, glossy papers include a porous nanoparticle top coating that accelerates ink drying and prevents spreading (Fig. S2). While these additional layers can improve print resolution, they prevent glossy paper from being biodegradable or recyclable60.

a SEM of raw agripaper. b SEM of treated agripaper following EC coating and calendering. c Cross-sectional SEM of raw and treated agripapers. d Roughness profiles of treated agripaper, raw agripaper, and commercial printer paper. Each profile is offset by 20 µm in the y-axis for clarity. e Stress-strain curves of treated agripaper, raw agripaper, and commercial printer paper. f Images of water droplets placed on treated agripaper, raw agripaper, and commercial printer paper in addition to a plot of the water contact angle as a function of time for the treated agripaper and commercial printer paper.

To make our agripaper more amenable to high-resolution printing while maintaining its biodegradability, we introduced a cellulose coating followed by calendering. Specifically, ethyl cellulose (EC) is a hydrophobic derivative of cellulose that is already commonly used in pharmaceuticals due to its biocompatibility, water resistance, and favorable film-forming properties61. In our case, an EC coating serves to both replace the chemical sizing agent and smooth the agripaper surface to improve print morphology. Importantly for scalable manufacturing, the EC coating is easily applied by dipping the agripaper in a 50 mg mL−1 solution of EC in ethanol. The subsequent calendering step is similarly compatible with scalable manufacturing, as it is a standard industrial papermaking process where sheets are densified by pressing them between heavy-duty rollers. Following EC coating, our agripaper is calendered by ~40% to a final thickness of ~180 µm. Figure 3b illustrates the significant morphological changes to the surface of the agripaper after the EC coating and calendering treatments, with Fig. 3c also revealing substantial densification of the agripaper. Laser confocal microscopy profiles further confirm the changes to the agripaper surface following EC coating and calendering (Fig. 3d). Quantitatively, the average surface roughness of the treated agripaper decreased by 73% from 7.25 µm to 1.98 µm, which is also significantly smoother than printer paper (3.63 µm). Figure 3e compares the tensile strength of the treated agripaper to its raw counterpart, again with printer paper as a control. The EC coating and calendering treatments stiffen the agripaper and increase its ultimate tensile strength from 19 MPa to 33 MPa, surpassing that of printer paper (23 MPa). The EC coating and calendering treatments also form a barrier to ink absorption, enabling higher quality and thicker prints. Figure 3f shows images of surface water droplets, allowing quantification of the water contact angle as a function of time. This study confirms that the hydrophobic EC coating results in significant delays in water absorption for the treated agripaper (additional images of the water contact angle analysis are provided in Figure S3). Overall, the optimized agripaper is a minimally processed, sustainable substrate for high-resolution printed electronics.

Biomass-derived graphene-CNC ink

Printed electronics are low-waste, inexpensive, flexible alternatives to silicon-based electronics19,62. As a result of these advantages, printed electronics are viewed to be ideal for large-scale manufacturing of disposable sensors, smart packaging, and other mass-produced devices20. Silver nanoparticle inks are the most common type of electrically conductive printable ink; however, they are also recognized as the most problematic component of printed electronics regarding sustainability. Not only does silver nanoparticle production have the largest carbon footprint among printed electronic materials, silver leachate also causes ecotoxicological problems63,64.

Carbon materials are the most common alternative to silver for printable conductive inks65,66,67,68, primarily due to their abundance, low cost, and environmental friendliness26,69. Therefore, we pursued graphene nanoplatelets exfoliated from graphite as the conductive component of our inks. While graphite is already relatively inexpensive and more sustainable compared to silver, concerns remain over its sourcing since graphite mining leads to environmental damage and dust emissions, which will grow as graphite demand for lithium-ion batteries increases70,71. Furthermore, the feedstock of raw graphite is not uniformly distributed worldwide, which leads to supply chain risks72. Indeed, multiple governments globally have recently classified natural graphite as a critical mineral with high supply risk due to persistent challenges in domestic production73. To combat these issues, we utilized graphite derived from renewable hardwood biochar, which is a byproduct of biodiesel production. The creation of value-added products from waste also provides economic incentives to biofuel producers and supports the bioeconomy.

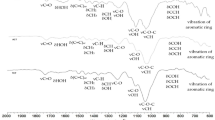

We first converted hardwood biochar into graphite by pyrolysis in the presence of an iron catalyst as described in our previous work74. This highly crystalline graphite product is then directly exfoliated in water using carboxyl-functionalized cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) as a surfactant (Fig. 4a). CNCs are biorenewably extracted from miscanthus and stabilize graphene in aqueous solution by adsorption onto the graphene basal plane, resulting in a suppression of reaggregation due to electrostatic repulsion from the negatively charged surface carboxyl groups75. Following exfoliation via ultrasonication and purification via centrifugation, a graphene-CNC composite powder is isolated and dried by rotary evaporation. Note that in this work, the CNCs simultaneously act as a stabilizer for the graphene nanoplatelets during exfoliation as well as the water-sensitive component of the humidity detection mechanism introduced previously (Fig. 2).

a Photo of the raw materials used for exfoliation of the graphene-CNC ink: CNCs derived from miscanthus, and graphite derived from hardwood biochar. b Photograph of an aerosol jet printed array of six devices. c Optical micrograph of a printed graphene-CNC feature. d Humidity sensitivity of devices with varying amounts of CNCs. e Thermogravimetric analysis of the optimized graphene-CNC composite; inset: photograph of the graphene-CNC AJP ink. f SEM of a printed graphene-CNC feature.

An aerosol jet printable ink is then formulated by dispersing the graphene-CNC powder in water at a concentration of 15 mg ml−1 with the addition of 5 vol% Cyrene, a plant derived solvent. Cyrene has a favorably high boiling point76 that prevents the aerosolized ink from drying as it is carried by the sheath gas, thereby reducing overspray during printing77. In addition, Cyrene promotes favorable interactions with the agripaper surface upon deposition, significantly improving print morphology. In contrast, Fig. S4 shows images of the deposited ink that did not contain the Cyrene co-solvent. In this case, significant beading occurs as the hydrophobic EC coating repels the water-only ink. Ultimately, Cyrene helps lower the surface energy of the ink, which improves wetting to the agripaper substrate78.

Humidity sensors were fabricated by depositing a thin trace of the graphene-CNC ink onto the agripaper substrate via AJP. Figure 4b shows an image of six printed sensors, and Fig. 4c shows an optical micrograph of the print, depicting a highly uniform printing edge. The humidity response of these sensors was found to depend on the ratio of CNCs to graphene nanoplatelets in the deposited trace. Since the modulation in sensor resistance relies on the swelling of the composite when exposed to humidity, increasing the fraction of hydrophilic CNCs leads to a higher change in resistance (R/R0) (Fig. 4d). Please note that R refers to the measured resistance, and R0 refers to the resistance value at the baseline humidity of 35% RH. The figure shows that an increased amount of CNCs in the printable ink creates a film that is richer in hydrophilic carboxyl and hydroxyl groups. This change is reflected in the C1s XPS spectra of the films, where increasing the CNC fraction in the composite film from 20% to 56% leads to a direct increase of the C-O and C = O features (~286 eV and ~288 eV, respectively) (Fig. S5). The increased amount of hydrophilic groups enables a higher degree of moisture absorption and swelling, which correlates with a higher change in resistance for greater sensitivity. However, increasing the CNC fraction further was found to create a film that was too resistive for accurate measurement. Sensor performance will be further explored in more detail below.

Figure 4e shows thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the deposited aerosol stream, indicating a CNC fraction of ~56%, which closely matches the solids loading in the ink. Figure 4f is an SEM image of the optimized printed film, which shows the graphene nanoplatelets encased in the CNC matrix. The difference in film morphology with varying amounts of CNCs is also evident in SEM, where the film appears more uniform and polymer-rich with a higher fraction of CNCs (Fig. S6).

Humidity sensor performance

Printed humidity sensors typically employ one of the following two sensing mechanisms: changes in capacitance or resistance79. Capacitive sensors rely on the change in the dielectric constant of a material when exposed to moisture80,81. While effective, capacitance sensing adds complexity to fabrication because precise device geometries with small gap sizes are required for high sensitivity81, which can also lead to a less robust sensor that is susceptible to failure during fabrication or usage. On the other hand, in a resistive humidity sensor, as employed in this work, charge transport is directly modulated by moisture. Resistive sensing is considered the simplest sensor mechanism for facile circuit integration28,82.

Figure 5 summarizes the performance of our resistive humidity sensor in a variety of scenarios. During testing, a small voltage of 0.1 V is applied to the device, and current is measured as a function of time. This small operational voltage contributes to low power consumption and enhanced safety in IoT applications82. Figure 5a shows the sensor response to humidity changes, indicated by the relative resistance change (R/R0) increasing as the humidity incrementally changes from 35% to 85% RH. The sensing curve shows excellent agreement with the actual chamber humidity, which was measured independently with a commercial humidity meter (Fig. S7). It is also notable that the hydrophobic EC coating on the agripaper substrate was key to achieving reliable performance at high humidity. Figure S8 shows the performance of the sensor printed on calendered agripaper without the EC coating. While sensor performance is comparable at low humidity, it begins to degrade at high humidity as the paper itself begins absorbing water, which disrupts desorption from the graphene-CNC composite film leading to delayed sensor recovery.

a Relative resistance change (R/R0) for humidity variations from 35% RH to 85% RH; inset: photograph of the humidity sensor. b Humidity sensitivity curve averaged from six independently printed sensors (error bars represent standard deviation). c Response and recovery time analysis based on sensor response to an exhaled breath. d R/R0 for continuous 20-min humidity cycles between 35% RH and 65% RH. e R/R0 of the sensor (black) as the temperature is varied between 10 °C and 40 °C (orange). Chamber humidity was held constant at 50% RH, but fluctuated upon each temperature change as independently monitored with a commercial humidity meter (teal). f Breathing detection for fast and slow breathing rates.

Figure 5b quantifies the sensitivity of the sensor, which shows an R/R0 of 2.6 over a humidity range of 35% RH to 85% RH. These results are comparable or better than the leading carbon-based, printed humidity sensors in the literature (Table S1). The standard deviation of responses among 6 independently printed sensors was ~5%, highlighting the reproducibility of the additive manufacturing process. The sensor exhibited an exceptional ~1 sec response time and ~4 sec recovery time (Fig. 5c), defined as the time to reach 95% of the resistance value at its final state80,82. However, it is worth noting that standards for reporting response and recovery times are not well-established, as the reported value is highly dependent on the humidity sensing range and the speed at which the chamber humidity itself can be altered80. Due to limitations with the ability of the testing chamber to quickly reach a stable humidity, response time was measured by exposing the sensor to a burst of exhaled breath. This approach created a rapid, local humidity increase that could more accurately represent the responsiveness of the sensor. Figure S9 shows an alternative analysis of response and recovery times recorded in an environmental chamber, which includes the ramp time of the chamber to reach the target humidity.

Figure 5d shows the high degree of consistency of the sensor during relatively short humidity exposure cycles from 35% to 65% RH for 20 min each. Figure 5e shows that the sensing mechanism is virtually independent from temperature variations, as the sensor output almost perfectly follows the actual humidity even as temperature is varied stepwise between 10 °C and 40 °C. Figure 5f is a demonstration of the sensor for monitoring breathing, highlighting its performance even in rapid humidity change scenarios.

Not only do these sensors show excellent performance, but they are also the only printed humidity sensors made entirely from plant-based materials. Previously published printed humidity sensors use some combination of metallic inks, plastics, or glossy papers. For instance, even previously reported printed humidity sensors based on entirely carbon-based inks still employ a plastic substrate, making them non-recyclable26. By optimizing the substrate-ink interactions and the ink composition itself, we achieve highly competitive performance metrics while utilizing entirely biorenewable and compostable materials in a manner compatible with scalable additive manufacturing.

Discussion

In this work, fully printed humidity sensors were produced from raw materials derived entirely from biomass. The agripaper substrate was produced from hemp and miscanthus, which are hardy, drought-tolerant agricultural crops. Meanwhile, the sensing layer was composed of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) derived from miscanthus and graphene nanoplatelets derived from hardwood biochar, a byproduct of the biofuel industry. These plant-based sensors have exceptionally high sensitivity and exceed the performance metrics of printed humidity sensors fabricated using plastic substrates, silver inks, and other non-plant-based materials. Moreover, these sensors are fabricated using scalable additive manufacturing with exceptionally low environmental impact over their entire life cycle—from sourcing the raw materials to production to disposal. By expanding the potential value-added applications of biomass, we align environmental benefits with economic incentives, thereby encouraging the growth of a circular bioeconomy.

Methods

Agricultural fiber papers (agripapers)

The agripaper substrates were produced at Fresh Press Studio located on the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) campus. The miscanthus (Miscanthus x giganteus) fibers were collected as pesticide-free agricultural residue from the University of Illinois Sustainable Student Farm, after which they were dried naturally and chipped. The hemp (Cannabis sativa) fibers were supplied by Carriage House Paper. In this case, 2 lbs of fibers were cooked in water with 175 g Na2CO3 for 3 hours. Subsequently, 4 oz each of miscanthus and hemp were beaten (Hollander Beater) for 30 min, pulled using a mould and deckle (Chester Creek Press), pressed (Reina Press), and dried. A range of paper thicknesses were produced, but a relatively thick paper of ~300 µm was chosen for the sensors to maintain robustness during clipping and handling. Thinner agripaper sheets are also available when more flexibility is desired.

An ethyl cellulose (EC, Millipore Sigma, 4cp) coating was applied by dipping the agripaper sample in a 50 mg mL−1 EC-ethanol solution, forming a coating that was ~10% of the substrate by mass. Finally, the paper was calendered (MTI Corp, MSK-HRP MR100DC) at decreasing gap sizes until a final paper thickness of 180 µm was achieved. Commercial white paper (Boise X-9) and glossy paper (Epson Premium Glossy Paper) were used as control substrates.

Imaging was performed using optical microscopy (Olympus, BX51M) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi, SU8030). Roughness measurements were carried out using a 3D laser confocal microscope (Olympus, LEXT OLS5000). Contact angle measurements were performed using a goniometer (Kruss DSA100 Drop Shape Analyzer). Tensile testing was performed on a dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA, TA Instruments, RSA G2). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed on a thermal analysis system (Mettler Toledo, TGA/DSC 3 + ).

Cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs)

Miscanthus (Miscanthus x giganteus) stalks were donated by Prof. DoKyoung Lee at UIUC. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), acetic acid, and sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution (available chlorine 10-15%) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium chlorite (NaClO2), 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine 1-oxyl (TEMPO), and sodium bromide (NaBr) were purchased from MilliporeSigma.

Carboxyl-functionalized CNCs (MxG-CNC-COOH) were isolated from miscanthus stalks according to a method previously published with a few modifications44. In particular, 100 g of ground miscanthus stems were soaked in 1.0 L of deionized water for 4 days. After filtration, two base washes were performed by soaking the stems in 1.6 L of 2.3% NaOH solution at 95 °C for 24 hours. The fibers were filtered and washed with deionized water after each base wash. The resulting fibers were soaked in 2.5 L of 2 wt% sodium chlorite solution with 4 mL of acetic acid at 70 °C for 2 hours. The resulting suspension was filtered and washed with deionized water, after which a white pulp was obtained. To obtain MxG-CNC-OH, the white pulp was hydrolyzed with 2.0 L 1 M HCl at 70 °C for 15 hours. After washing with deionized water, the MxG-CNC-OH was added to a solution of 2.0 g TEMPO and 24 g of NaBr in 1.6 L deionized water, in which 400 mL of NaOCl solution was then added. The pH of the mixture was maintained between 10-11 for 4.5 hours. After the reaction finished, NaCl (30 g) was then added to the mixture and stirred for 10 min. Subsequently, 1 M HCl was added to the reaction to adjust the pH to 6. MxG-CNC-COOH was obtained by centrifuging the mixture, followed by dialysis against deionized water for 3 days, and then freeze-drying. This process ultimately yielded 31 g (31%) of white fluffy MxG-CNC-COOH.

Biographite synthesis

Ethanol (Decon Labs, 200 proof) was purchased from Fisher Scientific. Concentrated sulfuric acid and iron powder (<10 μm) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Pyrolyzed hardwood char (preheated at 1100 °C, N2 protected) was generously provided by American GreenFuels Rockwood (Tennessee), LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Kolmar Americas, Inc.

A mixture of 30.0 g biochar and 60.0 g iron powder was added to the ball mill (Tencan powder technology, QM-5). The ball mill was set at a rate of 120 rpm and run for 3 h. The resulting powder was passed through a 100 Mesh sieve and placed in a tube furnace. Nitrogen gas was flowed through the tube (100-200 sccm), before the furnace was heated to 1200 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, maintained at a constant temperature for 1 h, cooled to 600 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, and then naturally cooled to room temperature. A mixture of 70 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid, 500 mL of deionized water, and 50 mL of ethanol were added to a beaker and mixed well. Then, the powder obtained from graphitization was slowly added to the beaker under magnetic stirring, after which stirring continued overnight at room temperature. Biographite was extracted by filtration of the mixture and then washed with deionized water until the filtrate pH was above 6. The powder was then vacuum oven-dried at 120 °C overnight, resulting in 20.7 g (69%) of black biographite powder.

Exfoliation of biographite-CNCs and aerosol jet printing ink formulation

Exfoliation of biographite using CNCs was performed based on a previously developed procedure75. Briefly, CNCs were dispersed in deionized water (2 mg mL−1) using 5 min of probe sonication (Qsonica Sonic Dismembrator Model 750, 13 mm Branson tip) in a stainless-steel beaker. Then, the synthesized biographite (50 mg mL−1) was added to the solution and probe sonicated for 10 hours in a water bath held at 4 °C using a recirculating chiller. The sonication program was set at 6 sec on, 2 sec off to prevent overheating. The exfoliated suspension was centrifuged (Beckman Coulter Avanti J-26 XPI) at 4500 rpm (~3700 g) for 30 min, and the resulting supernatant was powderized using a rotary evaporator (Buchi R-300 Rotavapor). The graphene-CNC composite powder and any additional CNC was then dispersed in water and bath sonicated overnight. A small amount of Cyrene was added to the solution (5%) to improve printing performance, and the mixture was filtered with a 1.6 µm glass microfiber syringe filter prior to aerosol jet printing.

Sensor fabrication

The ink was deposited via aerosol jet printing (Optomec, Aerosol Jet 200). The total sensor area was 7 mm × 9 mm with an arm width of 1.25 mm. The AJP settings were as follows: bath temperature of 30 °C, stage temperature of 60 °C, nozzle diameter of 300 µm, printing speed of 2 mm s−1, atomizing current of 0.51 mA, atomizer flow between 30-35 ccm, and sheath flow of 35 ccm. Following printing, no heat treatment or other post-processing was performed. The sensors were then placed in the environmental chamber (ESPEC, BTX-475) at 20 °C and cycled 2-3 times from 35% RH to 85% RH until the sensors showed a consistent baseline before testing.

Sensor testing

During humidity testing, resistance was measured using a sourcemeter (Tektronix Keithley 2400). Alligator clips were attached directly to the printed graphene-CNC contact pads. The current was recorded while applying a constant voltage of 0.1 V. The samples were tested in an environmental chamber, where pre-programmed humidity profiles were executed. The temperature was held constant at 20 °C unless otherwise indicated. A commercial humidity meter (Extech, RH520B) was placed inside the chamber alongside the printed sensors as an independent measure of the chamber humidity.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Zikria, Y., Bin, Ali, R., Afzal, M. K. & Kim, S. W. Next-Generation Internet of Things (IoT): Opportunities, Challenges, and Solutions. Sensors 21, 1174 (2021).

Khan, Y. et al. A New Frontier of Printed Electronics: Flexible Hybrid Electronics. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905279 (2020).

Parate, K. et al. Aerosol-Jet-Printed Graphene Immunosensor for Label-Free Cytokine Monitoring in Serum. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 8603 (2020).

Sui, X., Downing, J. R., Hersam, M. C. & Chen, J. Additive Manufacturing and Applications of Nanomaterial-Based Sensors. Mater. Today 48, 135 (2021).

Parate, K. et al. Aerosol-Jet-Printed Graphene Electrochemical Histamine Sensors for Food Safety Monitoring. 2D Mater 7, 034002 (2020).

Fathi, P., Shrestha, S., Yerramilli, R., Karmakar, N. & Bhattacharya, S. Screen Printed Chipless RFID Tags on Packaging Substrates. Flex. Print. Electron. 6, 025009 (2021).

Ostfeld, A. E., Deckman, I., Gaikwad, A. M., Lochner, C. M. & Arias, A. C. Screen Printed Passive Components for Flexible Power Electronics. Sci. Rep. 5, 15959 (2015).

Li, W. et al. Biodegradable Materials and Green Processing for Green Electronics. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001591 (2020).

Wiklund, J. et al. A Review on Printed Electronics: Fabrication Methods, Inks, Substrates, Applications and Environmental Impacts. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 5, 89 (2021).

Prenzel, T. M., Gehring, F., Fuhs, F. & Albrecht, S. Influence of Design Properties of Printed Electronics on Their Environmental Profile. Matériaux Tech 109, 506 (2021).

Kwon, J. et al. Conductive Ink with Circular Life Cycle for Printed Electronics. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202177 (2022).

Gehring, F., Prenzel, T. M., Graf, R. & Albrecht, S. Sustainability Screening in the Context of Advanced Material Development for Printed Electronics. Matériaux Tech 109, 505 (2021).

Blumenthal, J. & Diamond, M. L. Sustainability of the Internet of Things Requires Understanding of Mineral Demands and Supplies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9835 (2022).

Lv, C. et al. Recent Advances in Graphene-Based Humidity Sensors. Nanomaterials 9, 422 (2019).

Su, Z. et al. Designed Biomass Materials for “Green” Electronics: A Review of Materials, Fabrications, Devices, and Perspectives. Prog. Mater. Sci. 125, 100917 (2022).

Mianehrow, H., Sabury, S., Bazargan, A. M., Sharif, F. & Mazinani, S. A Flexible Electrode Based on Recycled Paper Pulp and Reduced Graphene Oxide Composite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 28, 4990 (2017).

Li, Z. et al. Green and Sustainable Cellulose-Derived Humidity Sensors: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 270, 118385 (2021).

Koval, V. et al. Application of Nanocellulose in Humidity Sensors for Biodegradable Electronics. 2020 IEEE 10th International Conference Nanomaterials: Applications & Properties (NAP) 02NS01-1-02NS01-5 (IEEE, https://doi.org/10.1109/NAP51477.2020.9309598 2020).

Gupta, A. A., Bolduc, A., Cloutier, S. G. & Izquierdo, R. Aerosol Jet Printing for Printed Electronics Rapid Prototyping. 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) 2016-July, 866–869 (IEEE, 2016).

Korotcenkov, G., Simonenko, N., Simonenko, E., Sysoev, V. & Brinzari, V. Paper-Based Humidity Sensors as Promising Flexible Devices, State of the Art, Part 2: Humidity-Sensor Performances. Nanomaterials 13, 1381 (2023).

Nikolidakis, S. A., Kandris, D., Vergados, D. D. & Douligeris, C. Energy Efficient Automated Control of Irrigation in Agriculture by Using Wireless Sensor Networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 113, 154 (2015).

Aliac, C. J. G. & Maravillas, E. IOT Hydroponics Management System. 2018 IEEE 10th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology,Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM) 1–5 (IEEE, https://doi.org/10.1109/HNICEM.2018.8666372.2018).

Grau, G., Kitsomboonloha, R., Swisher, S. L., Kang, H. & Subramanian, V. Printed Transistors on Paper: Towards Smart Consumer Product Packaging. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 5067 (2014).

Barmpakos, D., Segkos, A., Tsamis, C. & Kaltsas, G. A Disposable Inkjet-Printed Humidity and Temperature Sensor Fabricated on Paper. Proceedings 977 (MDPI, https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2130977 2018).

Dagnon, K. L. et al. Controlling the Rate of Water-Induced Switching in Mechanically Dynamic Cellulose Nanocrystal Composites. Macromolecules 46, 8203 (2013).

Yoshida, A. et al. Printed, All-Carbon-Based Flexible Humidity Sensor Using a Cellulose Nanofiber/Graphene Nanoplatelet Composite. Carbon Trends 7, 100166 (2022).

Tachibana, S. et al. A Printed Flexible Humidity Sensor with High Sensitivity and Fast Response Using a Cellulose Nanofiber/Carbon Black Composite. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 5721 (2022).

Barras, R. et al. Printable Cellulose-Based Electroconductive Composites for Sensing Elements in Paper Electronics. Flex. Print. Electron. 2, 014006 (2017).

Nagaraju, G. et al. An Agriculture-Inspired Nanostrategy towards Flexible and Highly Efficient Hybrid Supercapacitors Using Ubiquitous Substrates. Nano Energy 66, 104054 (2019).

Moro, G. et al. Disposable Electrodes from Waste Materials and Renewable Sources for (Bio)Electroanalytical Applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 146, 111758 (2019).

Tao, J. et al. Super-Clear Nanopaper from Agro-Industrial Waste for Green Electronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 3, 1600539 (2017).

Pandey, A., Soccol, C. R., Nigam, P. & Soccol, V. T. Biotechnological Potential of Agro-Industrial Residues. I: Sugarcane Bagasse. Bioresour. Technol. 74, 69 (2000).

Zhang, S. et al. Sustainable Production of Value-Added Carbon Nanomaterials from Biomass Pyrolysis. Nat. Sustain. 3, 753 (2020).

Sanchez-Rexach, E., Johnston, T. G., Jehanno, C., Sardon, H. & Nelson, A. Sustainable Materials and Chemical Processes for Additive Manufacturing. Chem. Mater. 32, 7105 (2020).

Nassajfar, M. N., Deviatkin, I., Leminen, V. & Horttanainen, M. Alternative Materials for Printed Circuit Board Production: An Environmental Perspective. Sustainability 13, 12126 (2021).

Hakola, L. & Jansson, E. Sustainable Substrate for Printed Electronics. Print. Fabr. 2019 132 (2019).

Fang, Z. et al. Versatile Wood Cellulose for Biodegradable Electronics. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 13 (2021).

Jambeck, J. R. et al. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 347, 768 (2015).

Algozeeb, W. A. et al. Flash Graphene from Plastic Waste. ACS Nano 14, 15595 (2020).

Foroughi, F., Ghomi, E. R., Dehaghi, F. M., Borayek, R. & Ramakrishna, S. A Review on the Life Cycle Assessment of Cellulose: From Properties to the Potential of Making It a Low Carbon Material. Materials 14, 714 (2021).

Duan, Z. et al. Facile, Flexible, Cost-Saving, and Environment-Friendly Paper-Based Humidity Sensor for Multifunctional Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 21840 (2019).

González-García, S., Hospido, A., Feijoo, G. & Moreira, M. T. Life Cycle Assessment of Raw Materials for Non-wood Pulp Mills: Hemp and Flax. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 54, 923 (2010).

Favero, A., Thomas, V. M. & Luettgen, C. Life cycle and market review of the major alternative fibers for paper production. (2017).

Cudjoe, E. et al. Miscanthus Giganteus: A Commercially Viable Sustainable Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. 155, 230 (2017).

Yan, Y. et al. Miscanthus as a Carbon Precursor for Graphene Oxide: A Possibility Influenced by Pyrolysis Temperature. Bioresour. Technol. 331, 124934 (2021).

Qin, Z., Dunn, J. B., Kwon, H., Mueller, S. & Wander, M. M. Soil Carbon Sequestration and Land Use Change Associated with Biofuel Production: Empirical Evidence. GCB Bioenergy 8, 66 (2016).

Edyta, M., Piotr, P., Marcin, D. & Kamila, B. Comparison of Papermaking Potential of Wood and Hemp Cellulose Pulps 137, 134 (2015).

Manaia, J. P., Manaia, A. T. & Rodriges, L. Industrial Hemp Fibers: An Overview. Fibers 7, 106 (2019).

Benson, E., Ferris, Q. M., Teper, J. H., Vetter, A. & Nw, S. A Case for a New Case Paper: From Farm to Table to Desk to Bench. B. Pap. Gr. Annu. 38, 90 (2019).

Man, Y., Han, Y., Li, J. & Hong, M. Review of Energy Consumption research for Papermaking Industry Based on Life Cycle Analysis. Chinese J. Chem. Eng. 27, 1543 (2019).

Mehmood, K. et al. Treatment of Pulp and Paper Industrial Effluent Using Physicochemical Process for Recycling. Water 11, 2393 (2019).

Matchavariani, L. Environmentally Friendly Alternative Pulp and Paper Technologies. in Developments in Science and Engineering 327, 337 (2016).

Chandra, M. Use of Nonwood Plant Fibers for Pulp and Paper Industry in Asia: Potential in China. (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 1998).

Madakadze, I. C., Radiotis, T., Li, J., Goel, K. & Smith, D. L. Kraft Pulping Characteristics and Pulp Properties of Warm Season Grasses. Bioresour. Technol. 69, 75 (1999).

Sigoillot, C. et al. Comparison of Different Fungal Enzymes for Bleaching High-Quality Paper Pulps. J. Biotechnol. 115, 333 (2005).

Camarero, S. et al. Efficient Bleaching of Non-Wood High-Quality Paper Pulp Using Laccase-Mediator System. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 35, 113 (2004).

Tobjörk, D. & Österbacka, R. Paper Electronics. Adv. Mater. 23, 1935 (2011).

Huang, S. et al. Water and Oil-Grease Barrier Properties of PVA/CNF/MBP/AKD Composite Coating on Paper. Sci. Rep. 13, 12292 (2023).

Forsberg, V. Liquid Exfoliation of Molybdenum Disulfide for Inkjet Printing. (Mid Sweden University, 2016).

Irimia-Vladu, M. ‘Green’ Electronics: Biodegradable and Biocompatible Materials and Devices for Sustainable Future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 588 (2014).

Larsson, M., Hjärtstam, J., Berndtsson, J., Stading, M. & Larsson, A. Effect of Ethanol on the Water Permeability of Controlled Release Films Composed of Ethyl Cellulose and Hydroxypropyl Cellulose. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 76, 428 (2010).

Perelaer, J. et al. Printed Electronics: The Challenges Involved in Printing Devices, Interconnects, and Contacts Based on Inorganic Materials. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 8446 (2010).

Naji Nassajfar, M. et al. The Effect of Conductive Ink Alternation on the sustainability and Functioning of Printed Electronics. Flex. Print. Electron. 8, 025015 (2023).

Sanchez-Duenas, L. et al. A Review on Sustainable Inks for Printed Electronics: Materials for Conductive, Dielectric and Piezoelectric Sustainable Inks. Materials 16, 3940 (2023).

Liu, L., Shen, Z., Zhang, X. & Ma, H. Highly Conductive Graphene/Carbon Black Screen Printing Inks for Flexible Electronics. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 582, 12 (2021).

Chaney, L. E. et al. Bayesian Optimization of Environmentally Sustainable Graphene Inks Produced by Wet Jet Milling. Small 20, 2309579 (2024).

Chen, F. et al. Interface-Exfoliated Graphene-Based Conductive Screen-Printing Inks: Low-Loading, Low-Cost, and Additive-Free. Sci. Rep. 10, 18047 (2020).

Secor, E. B., Prabhumirashi, P. L., Puntambekar, K., Geier, M. L. & Hersam, M. C. Inkjet Printing of High Conductivity, Flexible Graphene Patterns. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1347 (2013).

Williams, N. X., Bullard, G., Brooke, N., Therien, M. J. & Franklin, A. D. Printable and Recyclable Carbon Electronics Using Crystalline Nanocellulose Dielectrics. Nat. Electron. 4, 261 (2021).

Surovtseva, D., Crossin, E., Pell, R. & Stamford, L. Toward a Life Cycle Inventory for Graphite Production. J. Ind. Ecol. 26, 964 (2022).

Engels, P. et al. Life Cycle Assessment of Natural Graphite Production for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes Based on Industrial Primary Data. J. Clean. Prod. 336, 130474 (2022).

Zhang, J., Liang, C. & Dunn, J. B. Graphite Flows in the U.S. Insights into a Key Ingredient of Energy Transition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 3402 (2023).

Bauer, D. J., Nguyen, R. T. & Smith, B. J. Critical Materials Assessment. (2023).

You, H. et al. Sustainable Production of Biomass-Derived Graphite and Graphene Conductive Inks from Biochar. Small 20, 2406669 (2024).

Hui, J. et al. Biorenewable Exfoliation of Electronic-Grade Printable Graphene Using Carboxylated Cellulose Nanocrystals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 57534 (2024).

Stini, N. A., Gkizis, P. L. & Kokotos, C. G. Cyrene: A Bio-Based Novel and Sustainable Solvent for Organic Synthesis. Green Chem. 24, 6435 (2022).

Guyll, B. I., Sanford, B. L., Pint, C. L. & Secor, E. B. Controlling Droplet Evaporation in Aerosol Jet Printing to Understand and Mitigate Overspray. Small Sci 5, 2500069 (2025).

Abdolhosseinzadeh, S., Jiang, X., Zhang, H., Qiu, J. & Zhang, C. John). Perspectives on Solution Processing of Two-Dimensional MXenes. Mater. Today 48, 214 (2021).

Chen, Z. & Lu, C. Humidity Sensors: A Review of Materials and Mechanisms. Sens. Lett. 3, 274 (2005).

Wawrzynek, E., Baumbauer, C. & Arias, A. C. Characterization and Comparison of Biodegradable Printed Capacitive Humidity Sensors. Sensors 21, 6557 (2021).

Gaspar, C., Olkkonen, J., Passoja, S. & Smolander, M. Paper as Active Layer in Inkjet-Printed Capacitive Humidity Sensors. Sensors 17, 1464 (2017).

Han, J.-W., Kim, B., Li, J. & Meyyappan, M. Carbon Nanotube Based Humidity Sensor on Cellulose Paper. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 22094 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was primarily supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through the MADE-PUBLIC Future Manufacturing Research Program (NSF Award Number CMMI-2037026). This work utilized the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, which is supported by the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), the Northwestern University Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) program (NSF DMR-2308691), and the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN). This work also used the MatCI Facility at Northwestern University, which is supported by the Northwestern University MRSEC (NSF DMR-2308691). L.E.C. additionally thanks Lidia Kuo for her help in developing the agripaper coating, and Ting-Ching Chu for providing the Python script used to record sensor measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.E.C. and J.H. contributed equally to this work, with L.E.C. leading the treatment of the agripapers and sensor performance, and J.H. leading the development of inks, printing of the sensors, and materials characterization. H.Y. and S.J.R. provided cellulose nanocrystals and biographite. J.R.D. and W.Y.C. contributed graphene characterization and aerosol jet printing. Y.Z. and J.B.D. contributed to the design and choice of raw materials. E.B. produced the raw agripapers. M.C.H. oversaw the project and directly supervised L.E.C., J.H., J.R.D., and W.Y.C. L.E.C., J.H., and M.C.H. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chaney, L.E., Hui, J., You, H. et al. Fully biodegradable printed electronic sensors based on biomass-derived graphene inks and agripapers. npj Adv. Manuf. 3, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44334-025-00063-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44334-025-00063-8