Abstract

Posiform planting is a method for constructing QUBO instances with a unique planted solution that can be tailored to arbitrary connectivity graphs. In this study we investigate making posiform planted QUBOs computationally harder by fusing many smaller random Ising models, whose global minimum is computed classically, with posiform planted QUBOs. The unique ground state of the resulting QUBO is the concatenation of (exactly one of) the ground states of each smaller problem. Our method generates QUBO instances that have a unique solution, are native to the hardware graph, and have tunable computational hardness. We use our QUBOs to benchmark three D-Wave quantum annealing processors (with 563–5627 qubits), and compare them against simulated annealing and Gurobi. Surprisingly, we find that the D-Wave ground state sampling success rate is not dependent on the glued random QUBO size, and that some QUBO classes are solved at high success rates at short annealing times on the Zephyr processors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

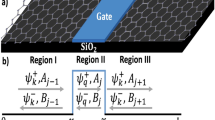

Quantum annealing is a type of analog quantum computation that aims to sample good solutions to combinatorial optimization problems1,2,3,4,5. Programmable quantum annealers containing up to several thousand superconducting qubits have been manufactured by the company D-Wave6,7,8,9,10,11,12, and have demonstrated notable compute-time and quality advantages over alternative methods on a number of different problem classes13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Quantum annealing is based on adiabatic quantum computation, where the system is initialized in the easy-to-prepare ground state of a Hamiltonian (typically the transverse field Hamiltonian) and then the system is slowly transitioned into a second Hamiltonian whose ground state is unknown and hard to compute2,20. In an ideal adiabatic evolution, this physical process can be used to find the ground state of Hamiltonians of interest. According to the adiabatic theorem, if certain conditions are met—such as sufficiently slow evolution—the system will remain in the ground state throughout the process21.

Mathematically, this adiabatic evolution is governed by a time-dependent Hamiltonian H(t) that gradually transforms from an easily prepared initial state Hamiltonian (denoted as Hinitial) to the problem-specific Hamiltonian of interest (denoted as Hising), where

The functions A(t) and B(t) in Eq. (1) define the time-dependent anneal schedules, whereby the initial state is slowly ramped down over the course of the anneal (of time t) given by A(t), and the magnitude of the problem of interest is increased by B(t). For quantum annealing in the transverse field Ising model1, \({H}_{initial}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i}^{n}{\sigma }_{i}^{x}\), where \({\sigma }_{i}^{x}\) is the Pauli matrix acting on each qubit at index i.

Combinatorial optimization problems, such as NP-hard problems, can be formulated as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO)22,23,24 problem (or equivalently an Ising model) which can be written as

for \(n\in {\mathbb{N}}\) binary variables, where \({a}_{i}\in {\mathbb{R}}\) and \({a}_{ij}\in {\mathbb{R}}\) are given by the user and define the optimization problem. The variables xi, for i ∈ {1, …, n}, are the decision variables whose optimal assignment—whether minimizing or maximizing the objective function—is generally unknown a priori. Given the equivalence between spin systems and discrete combinatorial optimization problems, we will use the terms “ground state” and “optimal solution” interchangeably.

In D-Wave quantum annealers, the qubits act as spins, having measured states either +1 or −1, and users can program the linear and quadratic coefficients of the hardware qubits and couplers to represent a classical Hamiltonian that represents a discrete combinatorial optimization problem. For quadratic optimization problems, the variable states can be easily converted from spins (+1 or −1) to binary states (1 or 0). The problems whose decision variables are spins are called Ising models, and the problems whose decision variables are binary are called QUBO models.

A reasonably large number of studies have examined various techniques for formulating and solving combinatorial optimization problems on D-Wave quantum annealers25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. There are a number of practical challenges that limit the capabilities of D-Wave quantum annealers due to system constraints and sources of error, including limited qubit coherence times11,12, having a fixed hardware graph whose connectivity is quite sparse and therefore encoding arbitrarily connected problems requires graph minor embedding34,35,36,37,38, analog control errors39, and spin bath polarization that causes anneal-correlations40. For this reason, several studies have developed methods for benchmarking and mitigating different types of errors in D-Wave computations32,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. One of the central challenges with benchmarking the capabilities of quantum annealers for solving combinatorial optimization problems is verifying the accuracy of the produced solutions (specifically if the global optimal solution could be found), since quantum annealing is a heuristic algorithm. In particular, verifying whether the optimal solution was found requires using classical deterministic exact solvers to find the optimal solution, or to construct a problem such that the optimal solution is known in advance.

There are numerous algorithmic approaches designed to generate combinatorial optimization problems with known solutions, commonly referred to as solution planting. Examples include frustrated loops (meaning Ising models composed of parts containing only a subset of the variables) with tunable hardness48,49, tile-planting50, patch-planting51, or weighted MAX-2-SAT instances52, among others53. However, most methods do not guarantee the uniqueness of the planted solution. Another way to generate instances is by converting sets of linear equations, called equation planting54,55, which can ensure uniqueness at the expense of not being able to generate QUBOs of a general structure. Many methods have already been made available in software implementations, for instance the Chook toolbox56 and the dwig Python implementation57. Benchmarks for emerging computing technologies need to be computationally hard while having known optimal solutions, yet many problem instances are easily solvable using classical algorithms. For example, it has been shown that two of the existing quantum annealing spin glass benchmarks58,59 can be solved in general with a polynomial time classical algorithm because they are a type of planar spin glasses60.

The focus of our study is on the previously proposed Posiform Planting method61, which allows the creation of QUBO models tailored to an arbitrary connectivity graph, with a single unique bitstring as the planted solution. Posiform planting is a very general method in that it allows many choices to be made in regards to what problem coefficients can be used to create a valid instance for a given target bitstring, and the target bitstring can be chosen arbitrarily as well. A computationally more tractable variant of posiform planting has already been proposed62. However, a disadvantage of posiform planted QUBOs is that they are a type of MAX-2-SAT problem, making them very tractable to solve exactly (in linear time) with classical algorithms63. As shown in ref. 61, this also applies to solving posiform planted QUBOs with quantum annealers. The aim of this study is to increase the computational hardness of posiform planted QUBO models by combining them with random QUBO problems, and to use the resulting problem instances to benchmark several types of D-Wave quantum annealers. In this study we design QUBO problems that are tailored to the hardware interaction graphs of several D-Wave QPUs; these graphs are known as Pegasus graphs64,65 and Zephyr graphs66.

We expect that the proposed way of combining of random QUBO problems with posiform QUBOs produces QUBOs that are, in general, NP-hard, specifically because random QUBOs (and random Ising modes) are also in general NP-hard. However, we do not examine this in this study. It could be the case that random spin glasses defined on the sparse graphs of the underlying hardware, such as the class of QUBOs we present in this study, lend themselves to efficient classical simulations due to having a critical temperature of zero, as was shown in particular for the hardware graph of previous generations of D-Wave quantum annealers known as the Chimera graph67,68 and there is some evidence for spin glasses defined on Zephyr and Pegasus graphs possibly also having a zero critical temperature69. However, this potential classical simulatability of hardware compatible spin glasses is not definitely known to be true for the intermediate D-Wave processor sizes currently available, and is unknown in general for other classes of random Ising models defined on these relatively sparse hardware graphs67,68,69.

The ability to control the degeneracy of ground states, which our proposed method allows, can be a valuable characteristic of a solution planting algorithm. In particular, ensuring the uniqueness of the ground state is especially relevant for random discrete-coefficient discrete decision variable optimization problems. Attenuating the degeneracy of the optimal solutions of discrete optimization problems can be a useful property since some quantum algorithms may not uniformly sample the optimal solutions70,71,72,73,74,75,76.

This article is structured as follows. In section “Methods”, we present the proposed improvement of the posiform planting algorithm of ref. 61, and briefly describe simulated annealing of ref. 77 which we use as a benchmark algorithm. Our experimental results are presented in section “Results”, in particular with respect to success rates for optimal solution sampling on D-Wave (section “Success rates of optimal solution sampling on D-Wave quantum annealers”) and simulated annealing (section “Success rates of optimal solution sampling with simulated annealing”), as well as Time-to-solution (TTS) results (section “Time to solution on D-Wave QPUs”). The article concludes with a discussion in section “Discussion”.

Results

This section presents simulation results measuring the accuracy (in terms of ground state probability) and runtime (in the TTS metric) of the instances generated with the algorithm of section “Combining posiform planting with random QUBOs”. In particular, we start by giving details of the simulation setting in section “Simulation setting”. Afterwards, we examine the success rates for optimal solution sampling on D-Wave (section “Success rates of optimal solution sampling on D-wave quantum annealers”) and simulated annealing (section “Success rates of optimal solution sampling with simulated annealing”), as well as TTS results (section “Time to solution on D-Wave QPUs”). We conclude the section with Gurobi results (section “Discussion”).

Simulation setting

The annealing times used to sample the problem instances is varied over {1, 2, 3, 4, …19, 20, 100, 1000, 2000} µs. In the case of Advantage_system4.1 and Advantage2_prototype2.3, an annealing time of 500 ns is also used. The measured sample distributions are computed by executing 100 anneal-readout cycles for each job, which is then repeated multiple times for each parameter configuration so as to build a large sample distribution for each QUBO problem instance. Some characteristics of the three D-Wave systems are given in Table 1. The D-Wave QPUs used in this study typically operate at or near 16 mK.

On the Advantage2_prototype1.1 device, hardware compatible QUBO models (for both lin20 and lin2 cases) are sampled with posiform scaling coefficient 0.01 on the D-Wave hardware using 10000 samples for each of the random 100 QUBO models and annealing times. All other QUBO models are sampled with 1000 samples per parameter combination. The Advantage2_prototype1.1 QUBOs with posiform scaling 0.01 are solved with a larger number of samples because the sampling success rate was found to be especially low (0 for many problem instances), and thus we increased the sample count with the goal of being able to quantify the TTS.

The largest random QUBOs that are exactly solved using CPLEX is limited by the compute time required to solve the models. We limit the compute time to be a maximum of 2 days on a single compute node, using a single thread. For any larger Zephyr graphs, CPLEX reached this compute time limit, as did larger Pegasus graph instances. Therefore, larger random QUBOs could be solved, but would require either using a faster optimization software, or using much more compute time.

Success rates of optimal solution sampling on D-Wave quantum annealers

In this section we investigate the success rate with which the optimal (that is, the planted) solution is being sampled on different D-Wave devices. The devices being considered are Advantage_system4.1, Advantage2_prototype1.1, and Advantage_prototype2.3. To this end, we generate 100 random posiform planted QUBOs which always cover the entire hardware graph of the respective architecture being used, and glue on a varying number of smaller random-coefficient QUBOs having appropriately chosen sizes.

We start with Advantage_system4.1. When gluing on smaller QUBOs to the posiform planted QUBO, we employ a posiform QUBO scaling coefficient of 0.1. Figure 1 reports the success rate for Advantage_system4.1 in finding the unique planted optimal solution. All proportions being reported are with respect to the generated ensemble of 100 posiform planted QUBOs. Figure 1 presents success rates as a function of annealing time. We observe that the optimal solution sampling success rate is generally low, with a maximum of ~0.25. Although the shapes of the plots in the two columns for lin2 and lin20 look similar, the scales on the left are much lower, indicating smaller success probabilities. We observe that smaller annealing times lead to a higher success rate on the Advantage_system4.1, and that especially for coefficients chosen from lin20 (right column), success rates flatten off closer to 0 with longer annealing times.

Columns show QUBOs with coefficients from lin2 (left) and lin20 (right). Rows show results for QUBOs constructed with 128 disjoint random QUBOs of size either 43 or 44 variables (first row), 64 disjoint random QUBOs of size either 87 or 88 variables (second row), 32 disjoint random QUBOs of size either 175 or 176 variables (third row), 16 disjoint random QUBOs of size either 351 or 352 variables (fourth row), and 8 disjoint random QUBOs of size either 703 or 704 variables (fifth row).

We repeat the same experiment on the Advantage2_prototype1.1 device using a posiform QUBO scaling coefficient of 0.1 when combining the posiform planted QUBO with smaller QUBOs to disguise the solution. Similarly to the previous experiment, Fig. 2 again shows the the ground state sampling success rates. We observe in Fig. 2 that in contrast to the previous experiment on Advantage_system4.1, the success probabilities for Advantage2_prototype1.1 are much higher for low annealing times, with many generated QUBOs being solvable with probability 1.0. Moreover, there is a clear decrease to zero in probability as the annealing times increase. This pattern is consistent across the two coefficient choices (left and right columns), as well as the number and sizes of the smaller QUBOs being glued onto the posiform planted QUBO.

This experiment is repeated for Advantage_prototype2.3 in Fig. 3 using a posiform QUBO scaling coefficient of 0.1. The results in Fig. 3 for the Advantage_prototype2.3 device confirm the ones seen for Advantage2_prototype1.1 in that the achieved success probabilities are close to 1 for low annealing times and decrease towards 0 as the annealing times increase. As before, all subplots show a qualitative similar behavior for the different coefficient choices (columns) or the number and sizes of the smaller QUBOs being glued onto the posiform planted QUBO (rows).

Figure 4 shows the quantum annealing ground state sampling success rate for QUBOs tailored to the Advantage2_prototype1.1 hardware graph, but now using a posiform scaling coefficient of 0.01. This shows a clear decrease of ground state sampling success as compared to Fig. 2 with a larger posiform scaling coefficient. We observe that by making the posiform scaling coefficient small and making the random QUBO coefficient discrete in {+1, −1}, we can make these solution planted QUBOs much harder for the D-Wave hardware to solve optimally.

Posiform QUBO scaling coefficient is 0.01. lin2 QUBO instances are shown in the left-hand side column and lin20 QUBO instances are shown in the right-hand side column. Rows show results for QUBOs constructed with maximum random glued QUBO sizes of, in order from top to bottom, 36, 71, 141, and 282 variables.

Figure 5 shows quantum annealing ground state sampling success rates for the QUBOs defined on the Advantage2_prototype2.3 hardware graph, again with a posiform scaling coefficient of 0.01 (as opposed to Fig. 3). Here we see a significant decrease in optimal solution sampling rate, where for the lin2 QUBO instances (left column) the unique optimal is rarely sampled. Thus we again observe that the posiform scaling coefficient attenuates the computational hardness of these planted QUBOs. The overall consistent finding is that smaller posiform QUBO coefficients with respect to the fused random QUBOs make the problems harder for the D-Wave quantum annealers to solve.

Posiform QUBO scaling coefficient is 0.01. lin2 QUBO instances are shown in the left-hand side column and lin20 QUBO instances are shown in the right-hand side column. Rows show results for QUBOs constructed with maximum random glued QUBO sizes of, in order from top to bottom, 39, 77, 153, and 305 variables.

Figures 1, 2, 3 all show a consistent trend of higher ground state sampling rates at smaller annealing times, and lower ground state sampling rates at longer annealing times. This is a very interesting property of quantum annealing and these particular optimization problems—for many other optimization problems solved with quantum annealing in other studies, this trend is exactly reversed; usually better optimal solution sampling occurs at longer annealing times15,16,17,30,58,78,79. The cause of this effect is not known—it seems to occur most clearly on the newer hardware generation Zephyr-chip devices, and we encourage this as a future point of study. We speculate that this finding is related to several different components of the simulation. First, the hardware properties of the quantum annealing processor, because we observe that this property occurs very strongly for the two newer-generation Zephyr devices. Second, this property does not hold true for all of the QUBOs that we tested, suggesting that this property depends on the Ising model encoded on the hardware. Finally, this effect is more strong at very short annealing times, which suggests that this is dependent on open-system effects—however this result is counter-intuitive in terms of open system effects because of the solution quality decrease as annealing time increases; thermalization from open system effects typically results in a plateau in solution quality. Note that while this trend is the opposite of what we would expect due to the adiabatic evolution, at these annealing times the processor is not a fully closed and noiseless system11,12,80, meaning that this intuition would not apply.

Figures 1–5 all show a very consistent trend that the sampling success rate, although it does depend on annealing time, does not change noticeably as a function of the varying random QUBO sizes that were fused to the posiform planted QUBO. This can be seen by looking at the differences between the rows of all of these figures—each row denotes a different random QUBO size threshold. This is a counter-intuitive finding since larger random QUBOs generally require more compute time to solve to optimality, and thereby we would expect to see lower sampling success rates.

For all problem instances generated on Advantage_system4.1 using posiform scale factor of 0.01, the D-Wave hardware never sampled any of the optimal solutions out of the 1000 samples obtained for each individual instance and QUBO setting configuration. For this reason, there are no ground state sampling probability figures for this particular QUBO configuration, as there is for posiform coefficient scaling of 0.1 on the Advantage_system4.1 instances (Fig. 1). However, the natural question arises of how close the D-Wave the hardware was to sampling the planted solution. Figure 6 answers this question by plotting the energy difference between the planted solution energy and the lowest energy sample found on D-Wave hardware. The more negative this quantity is, the further away the quantum annealing hardware sample was from the planted solution, and the closer to 0 this quantity is, the closer the hardware sampling was to the optimal solution.

All of these QUBOs had a posiform scaling factor of 0.01, and were defined on the Advantage_system4.1 hardware graph—the notable property of these QUBOs is that the D-Wave hardware never sampled the unique planted solution. The minimum energy gap for the best solution found using the D-Wave hardware is indicated on the y-axis; values close to 0 denote samples very close to the optimal solution energy. Plot uses jittering on the x-axis for better visualization.

Success rates of optimal solution sampling with simulated annealing

In order to have a base for comparison we repeat the experiments of the previous section and solve the same QUBOs with the classical simulated annealing algorithm77. In particular, we solve the same set of QUBOs as in section “Success rates of optimal solution sampling on D-Wave quantum annealers”.

Figure 7 shows simulation results when solving the same set of QUBOs generated for Fig. 5, that is QUBOs tailored to the Advantage2_prototype2.3 hardware graph. Two observations are noteworthy. First, the displayed plots are qualitatively similar, in that they all show that the success probability increases with the number of Metropolis-Hastings updates, which is expected. In particular, the plots are similar for the QUBOs generated for QUBOs with coefficients from lin2 (left column) and lin20 (right column). Second, we observe that for a low number of Metropolis-Hastings updates, the success probability is (close to) zero, showing that the generated QUBOs are not trivial, and that moreover, more Metropolis-Hastings updates are needed for a non-zero success probability when the coefficients come lin20 (right column).

Columns show QUBOs with coefficients from lin2 (left) and lin20 (right). Posiform scaling coefficient of 0.01. The same QUBOs are solved in Figure 5.

Figure 8 shows qualitatively similar results to Fig. 7, where a small number of spin updates yields low ground state success rate and a larger number of spin updates yeilds ground state success rates closer to 1. However, Fig. 8 with posiform scaling of 0.1 has a much higher ground state success probability compared to Fig. 7 with posiform scaling of 0.01. This shows that the posiform scale factor can attenuate the hardness of these QUBO problems for simulated annealing. This same quality of the larger posiform scaling coefficients being easier was seen in the quantum annealing sampling results.

Advantage2_prototype2.3 hardware compatible QUBO results, where each subfigure shows the optimal solution sampling rate for the 100 different random QUBO instances, as a function of log-scale number of complete sweeps of Metropolis-Hastings updates. Posiform QUBO scaling coefficient is 0.1. lin2 QUBO instances are shown in the left-hand side column and lin20 QUBO instances are shown in the right-hand side column. The same QUBOs are solved in Figure 3.

The supplementary information shows three additional simulated annealing sampling figures. All of the simulated annealing sampling plots show that the optimal solution is able to be reliably sampled for all QUBO configurations if a sufficiently large number of variable spin updates is utilized.

An interesting property of the ground state sampling curves from simulated annealing for the posiform scaling 0.01 and lin2 coefficient distributions (see the left column of Fig. 7) is a slight down-turn of success probability just before 10 Metropolis-Hastings spin updates, before the success probability continues to increase. This non-monotonic behavior seems to be a characteristic of these specific problem instances as it is not seen in the other posiform solution planted QUBO configurations, and the cause is not known. We speculate that the temporary downturn in solution quality observed for simulated annealing might occur during the transition phase from exploration to exploitation, where the algorithm initially accepts worse solutions to escape local minima before refining toward better solutions at lower temperatures.

Time to solution on D-Wave QPUs

In this section we record the TTS metric for solving the previously considered ensembles of QUBOs. The TTS is computed as in section “Measuring the compute time to optimally solve a QUBO: time-to-solution”. Here TTS is computed for each individual hardware tailored QUBO instance using the entirety of the parameter sweep and all samples obtained for each QUBO, the results for which are described in section “Success rates of optimal solution sampling on D-Wave quantum annealers”. In particular, this means that the sample success rate is measured from the entirety of the samples across all annealing times used, and therefore the QPU time per anneal is the average QPU time across different annealing times. This approach to measure TTS was taken because the sampling success rate can vary quite significantly as a function of the annealing time. In particular, for some annealing times the measured optimal solution sampling success rate is 0.

Figure 9 shows TTS measurements for the full ensemble of posiform planted QUBOs with scaling coefficient of 0.1, sampled on the three D-Wave QPUs. Figure 10 shows the same for the scaling coefficient of 0.01 (not including Advantage_system4.1 because the optimal solution sampling rate was always zero). Each subplot shows a scatterplot of the TTS measurements as a function of the maximum random QUBO sizes that were glued to the whole-chip posiform QUBO. As the TTS cannot be measured if the optimal solution is never found, there are missing data points in these TTS measures.

Columns show QUBOs with coefficients from lin2 (left) and lin20 (right). Posiform coefficient scale factor 0.1. Rows show the three different D-Wave devices under consideration, those are Advantage_system4.1 (top), Advantage2_prototype1.1 (middle), Advantage_prototype2.3 (bottom). Plot uses jittering on the x-axis for better visualization. Log scale on the y-axis.

Columns show QUBOs with coefficients from lin2 (left) and lin20 (right). Posiform coefficient scale factor 0.01. Rows show the two different D-Wave devices under consideration, those are Advantage2_prototype1.1 (top) and Advantage_prototype2.3 (bottom). Plot uses jittering on the x-axis for better visualization. Log scale on the y-axis.

Figures 9 and 10 show that the measured TTS largely stays in the same range irrespective of the size (and number) of the QUBOs glued onto the whole-chip posiform QUBO.

Table 2 gives exact TTS quantities, and range of TTS quantities, for each QUBO parameter type.

Gurobi runtime

Figure 11 shows the Gurobi classical compute time required to deterministically find the unique optimal solution of the posiform planted instances, defined on Advantage2_prototype1.1. Figures 12 and 13 show the same Gurobi runtime scaling for the QUBOs defined on the other two D-Wave QPUs. However, in these cases, the cumulative compute time was too large to compute in a reasonable amount of time for the larger random QUBO subproblem sizes, and therefore these two figures are limited to a 200 variable size cutoff.

QUBO configurations are as follows: 0.01 posiform scaling lin2 (top left), 0.01 posiform scaling lin20 (top right), 0.1 posiform scaling lin2 (bottom left), 0.1 posiform scaling lin20 (bottom right). Here, we observe a clear dependence on total CPU runtimes with respect to the random QUBO size. x-axis coordinates have a small amount of noise jitter added for improved visualization.

Four observations are noteworthy. First, for Gurobi there is a clear dependence on the size of the random QUBO instances for the required runtime to find the optimal solution. This is consistent with previous studies that have used integer programming tools such as Gurobi to solve random spin glass instances defined on D-Wave hardware graphs15. In general, these random spin glasses get significantly harder to solve optimally as the problem size increases. This is significant because it shows that despite the gluing of the relatively easy-to-solve posiform planted QUBOs, the random QUBOs do make the overall problem very computationally challenging for state of the art optimization software such as Gurobi. Notably, this characteristic of random QUBO size dependence is not shared by either quantum annealing or simulated annealing ground state sampling results.

Second, we see that the more discrete coefficient problem instances are harder to solve using Gurobi, and the finer coefficient precision problem instances are easier to solve using Gurobi. This property is also seen in the simulated annealing and quantum annealing results.

Third, the QUBOs with posiform scaling coefficient 0.01 and ±1 coefficients are clearly the hardest instances to solve using Gurobi. This scaling property is consistent with both the quantum annealing results and the simulated annealing results.

Fourth, the exact runtimes used to solve each instance vary quite significantly for each random QUBO size. For some instances, the range of solution times spans several orders of magnitude.

Discussion

This study presents methodology to create solution planted QUBOs that are based on the posiform planting technique61, but are computationally harder than the default posiform planted QUBOs. Posiform planting has several useful features, namely that the connectivity of the generated QUBO can be tailored to (essentially) arbitrary graphs, and the planted solution is guaranteed to be unique. These properties of posiform planting are inherited by the QUBO problem generation used in this study. Both posiform planting and our proposed technique of combining random QUBOs with posiform planted QUBOs allows for very general optimization problem design, with a planed solution. This technique could be utilized for classical heuristic benchmarking, arbitrary classical optimization software, or any other emerging quantum computing algorithms. Our proposed method is very general, it can be applied to generate QUBO instances with a planted solution for basically any type of algorithm or device that solves such optimization problems. This includes classical heuristics, quantum optimization software, and hardware devices such as the D-Wave annealers (which might themselves can utilize additional techniques such as reverse quantum annealing).

Our proposed method starts by generating a posiform planted QUBO which is tailored to some architecture of interest, for instance the hardware graph of a D-Wave annealer. To increase the hardness of posiform planted QUBOs, we propose to add smaller QUBOs with a known solution to them, thus changing the coefficients of the whole-chip posiform QUBO. We demonstrate that the success rate of sampling the planted optimal solution for this class of problem instances can be lowered, meaning that the problems are indeed harder, than the posiform planting QUBOs by themselves61. This increase in computational hardness was seen by both quantum annealing and simulated annealing.

Among the two choices of coefficients which we considered for the generated QUBOs, we find that choosing coefficients in {+1, −1} and using a posiform QUBO scaling coefficient of 0.01 produced the most computationally challenging optimization problem instances. A possible cause for this is the presence of a large number of local minima whose energy is very close to the true ground state. This effect can be examined through the structure of the QUBO formulation. For instance, consider the case where the random QUBO, R, for one of the subgraphs has a set L = {l1, …, lk} of k > 1 optimal solutions. By construction, the posiform QUBO P for the same subgraph has one optimal, say l1, and k − 1 suboptimal solutions in L. If δi = P(li) − P(l1) is the suboptimality gap of li in P, then the combined QUBO Q = P + 0.01R satisfies Q(li) − Q(l1) = 0.01δi, meaning the suboptimality gap of li in Q is likely to be small, depending on the magnitude of δi. Moreover, the expected degree of degeneracy grows exponentially with the number of subgraphs, as the total degeneracy is the product of the degeneracy degrees of all subgraphs. Estimating this degree explicitly would require significant computational resources. However, the structural symmetry of Pegasus and Zephyr graphs, combined with binary coefficients, increases the likelihood that certain variable swaps preserve the objective value, increasing the probability of degeneracies.

All three of the D-Wave quantum annealing processors used were able to sample the optimal solutions of the easier of the generated QUBOs, but for many of the small posiform scale factor QUBOs the success rate was low, especially for Advantage_system4.1 with 5627 qubits. This shows that these QUBO problems can be used as a concise benchmark for heuristic algorithms to solve combinatorial optimization problems, and in particular allows us to evaluate the capability of the entire hardware graph of the quantum annealer to solve a combinatorial optimization problem with a significantly large combinatorial search space that has only a single optimal solution. This is a non-trivial benchmarking capability—many existing reported D-Wave benchmarks do not allow for usage of all working components of the hardware graph29,32,43,81,82. These optimization problems are notably quite large in scale, and our results show that D-Wave quantum annealing hardware can correctly find the single, unique, planted solution for an optimization problem that has up to 5627 binary decision variables.

Surprisingly, we found that the size of the smaller QUBOs glued onto the posiform planted QUBO (which is tailored to the whole D-Wave hardware) does not change the hardness, measured via the success rate of finding the ground state for either simulated annealing or quantum annealing. This result is unexpected, as it seems intuitive that larger random QUBOs would increase the difficulty of the overall problem compared to gluing together many smaller instances. On the practical side, this result implies that smaller random QUBO problems can be preferred to larger ones in order to improve the efficiency of the generating algorithm, as smaller problems require less time to solve on exact classical solvers compared to larger ones. Further investigation is needed to understand all factors influencing the computational hardness of these QUBO problems. However, notably the exact Gurobi runtime scaling did strongly depend on the size of the random QUBO problems. It should be noted that this Gurobi runtime scaling is not strictly for finding a solution to the problem, but rather finding and then verifying the optimality of that solution (or, then finding a better solution that is closer to optimality). This means that the overall Gurobi runtime includes the computation-time intensive task of verification, which certainly contributes to its high value.

We also observed that the profiles of the ground state sampling rates are different between the Pegasus chip D-Wave device (Advantage_system4.1) and the two Zephyr chip D-Wave devices (Advantage2_prototype2.3 and Advantage2_prototype1.1). The two Zephyr devices perform best at small annealing times and then the solution quality quickly drops off. The Pegasus hardware graph device shows a similar trend for the finer discretization random QUBOs, but for the coarser discretization random QUBOs the longer annealing times perform similarly to the median annealing times and very short annealing times do not produce good ground state sampling rates.

Methods

This section reviews the idea of posiform planting in section “Review of posiform planting” and describes the proposed improvement of the posiform planting algorithm in section “Combining posiform planting with random QUBOs”. Section “Proof of uniqueness of the planted solution” gives a proof that the newly generated QUBOs preserve the unique planted solution. We also briefly introduce the Time-to-Solution metric (section “Measuring the compute time to optimally solve a QUBO: time-to-solution”) and the simulated annealing algorithm (section “Simulated annealing”) which serves as a benchmark.

Review of posiform planting

Posiform planting of ref. 61 is an algorithm to create a QUBO with a planted solution. Posiform planting guarantees the uniqueness of the planted solution, and it creates QUBOs with a given connectivity structure, as long as the given connectivity structure is not too sparse. As the name suggests, the algorithm works by creating a posiform first, that is a quadratic function with positive coefficients on an extended set of variables \({\mathcal{Z}}=\{{x}_{1},\ldots,{x}_{n}\}\cup \{{\overline{x}}_{1},\ldots,{\overline{x}}_{n}\}\). The set \({\mathcal{Z}}\) includes all variables xi and their complements \({\overline{x}}_{i}=1-{x}_{i}\). Analogously to a QUBO, a posiform is given by

where each \(z\in {\mathcal{Z}}\) and \({z}^{{\prime} }\in {\mathcal{Z}}\) stand for one of the variables xi or its complement \({\overline{x}}_{i}\), i ∈ {1, …, n} and the coefficients bz and \({b}_{z{z}^{{\prime} }}\) are nonnegative. As shown in ref. 83, any QUBO can be written as a posiform.

Posiform planting works by generating a posiform P such that P(x*) = 0 for the solution x* to be planted. Since all coefficients of a posiform are nonnegative, P(x*) = 0 will also be the global minimum. To do this, we first generate a 2-SAT problem with x* as its unique solution. This is easily done as follows. The requirement that P(x*) = 0 implies that all summands in Eq. (3) must be zero. The solution x* therefore has the property that z = 0 for all linear terms in Eq. (3), and \(z{z}^{{\prime} }=0\) for all quadratic terms in Eq. (3), where \(z,{z}^{{\prime} }\in {\mathcal{Z}}\). In order to generate a 2-SAT problem having x* as its unique solution, we employ an exclusion argument, whereby we generate clauses in our 2-SAT problem that exclude any bitstring other than x*.

The creation of an appropriate 2-SAT problem is completed with the following probabilistic procedure. First, we select two random indices i, j ∈ {1, …, n} with i ≠ j. Second, we look at these two bits in the planted solution \({x}_{i}^{* }\) and \({x}_{j}^{* }\) and randomly select one of the three possible binary tuples \(({\hat{x}}_{i},{\hat{x}}_{j})\) satisfying \(({\hat{x}}_{i},{\hat{x}}_{j})\,\ne\, ({x}_{i}^{* },{x}_{j}^{* })\). Third, we add a clause to the current 2-SAT problem that excludes \(({x}_{i},{x}_{j})=({\hat{x}}_{i},{\hat{x}}_{j})\) in the optimal solution. The clause to choose can be given analytically by:

Since 2-SAT can be solved in linear time, it is easy to verify at any stage if the currently constructed 2-SAT instance already has x* as its unique solution. If this is not the case, more clauses are added. By construction, the solution x* to be planted is never excluded from the 2-SAT solution space. Once a 2-SAT instance with x* as its unique solution has been created, we convert each clause \((z\vee {z}^{{\prime} })=\neg (\overline{z}\wedge \overline{z}^{\prime} )\) into the quadratic term \({b}_{z{z}^{{\prime} }}\overline{z}\,\overline{z}^{\prime}\), where \(z,{z}^{{\prime} }\in {\mathcal{Z}}\). Since in the 2-SAT instance, each clause is satisfied (aka 1) for x* but needs to be zero in the posiform representation, a negation is necessary. It is important to note that posiform planting creates a posiform of the type of Eq. (3) with a unique solution x* by selecting appropriate quadratic variables only, the coefficient \({b}_{z{z}^{{\prime} }} > 0\) of each posiform summand is actually freely choosable (as long as it is positive). Converting the resulting posiform back into a QUBO (by multiplying out all terms) as shown in83 results in a QUBO with (typically) both positive and negative QUBO coefficients, and x* as its unique solution.

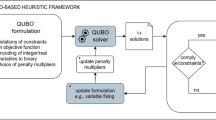

Combining posiform planting with random QUBOs

Roughly, our algorithm generates a set of smaller non-overlapping random QUBOs and one larger posiform planted QUBO that covers the hardware graph. The smaller random QUBOs are then fused with the large posiform planted QUBO covering the hardware graph. The aim of combining the larger (posiform planted) QUBO with smaller QUBOs is to alter the coefficients in such a way that the QUBO becomes harder to solve. At the same time, it is possible to add on the smaller QUBOs to the posiform planted QUBO without changing its optimal solution.

The disjoint graphs corresponding to these QUBOs are generated using the Networkx84 implementation of the Kernighan-Lin bisection algorithm85. Specifically, the hardware graph is recursively bisected into equally sized partitions until a threshold is reached. The total number of partitioned subgraphs is increased starting at a maximum number of variables (for all subgraphs) of 50. This recursive bisection technique ensures that the final partitioned subgraphs will be identically sized, unless there are any odd divisions in which case the number of variables in the partitioned subgraphs will be different from each other by at most 1 variable (this is only true because the number of partitions is always a power of 2).

Note that the construction of these disjoint hardware subgraphs is similar to the tiled embeddings used in parallel quantum annealing29,31,32,86,87, and therefore trends in solution quality as a function of sub-problem size found in this study should be compared against these previous studies (albeit in a slightly different context because these disjoint instances are designed be joined together). Figure 14 in the appendix shows an example of the partitioned Advantage_system4.1 hardware graph and Fig. 15 shows the same for the Advantage2_prototype1.1 device.

The bisection partitioning algorithm is stochastic, and so different runs can produce different partitions. When generating the random QUBO instances, a new different disjoint bisection partition is constructed for every instance.

The steps used to construct the hardware-native QUBO problems are defined as follows:

-

1.

Generate the bisected subgraphs that cover the entire hardware graph applying the Kernighan-Lin bisection algorithm recursively.

-

2.

Choose linear and quadratic random coefficients for all of the edges and nodes within the disjoint induced subgraphs of the hardware graph computed in the previous step. Here, we generate two distinct types of random QUBOs using two different discrete coefficient sets drawn from either {−1, −0.9, …, 0.9, 1} (with 20 different values) in increments of 0.1, or {−1, 1} (with 2 values). We will denote these two different types of QUBOs using the shorthand of lin20 and lin2, respectively.

-

3.

Use an exact classical solver to compute an optimal variable assignment for each of the random subproblems. In our case, we use CPLEX88, which can deterministically find an optimal variable assignment (given sufficient compute time). To this end, the optimization problem is formulated as a binary Mixed Integer Quadratic Program (MIQP).

-

4.

Concatenate together each of the single optimal variable assignments for each random problem found in the previous step (we do this based on some consistent bit-ordering, in this case we used consistent node indexing of the hardware graph). This concatenated bitstring thus gives a single variable state for every qubit (spin) in the hardware graph.

-

5.

Use the posiform planting algorithm introduced in ref. 61 to generate a QUBO whose planted ground state matches exactly the concatenated bitstring computed in the previous step. There are various valid choices for generating this posiform QUBO, although some may affect the coefficient range of the resulting QUBO problem, potentially leading to suboptimal performance when encoded onto current D-Wave quantum annealers. In our case, we use the 2-SAT solver Minisat89 (as in ref. 61). All posiform coefficients corresponding to a 2-SAT clause are chosen as 1. To conserve compute time, we only attempt to solve the 2-SAT instance being generated in batches. This may cause the generated 2-SAT instance to be (slightly) larger than is needed to ensure the uniqueness of the planted solution.

-

6.

"Glue" together all of the random QUBO problems and the posiform planted QUBO, which is done by simply summing all of the terms together. The obtained final QUBO inherits from posiform planting that it has a unique and known optimal solution. The posiform planted QUBO spans the entirety of the chip and connects together the small random QUBOs, making this final QUBO connected (and in particular, it covers a majority of the edges in the hardware graph and all of the nodes in the hardware graph). A parameter that we add into this QUBO combination step is a constant scale factor which we will refer to as the posiform scaling coefficient. This coefficient multiplies all of the terms in the posiform QUBO prior to their addition to the random QUBO problems. We evaluated this coefficient experimentally at 0.1 and 0.01. The reason for this is empirical. We observed in experiments that scaling the posiform QUBO coefficients by a factor prior to combining it with the smaller QUBOs resulted in harder problems for simulated annealing.

Proof of uniqueness of the planted solution

The process outlined in section “Combining posiform planting with random QUBOs”, whereby smaller QUBOs (solved to optimality with CPLEX) are combined with the larger posiform planted QUBO (having a unique solution), preserves the uniqueness of the solution. This section gives a formal proof of this statement.

Although some of the random QUBOs being generated may have multiple solutions (i.e., multiple minima), the combined final QUBO has a unique one. To see that, consider the random QUBOs R1, …, Rk and the posiform QUBO P. Denote the variables of P by X = {x1, …, xn}, and let subi(X) represent the subset of X used as variables in each Ri, for i = 1, …, k. Let \({X}^{* }=\{{x}_{1}^{* },\ldots,{x}_{n}^{* }\}\) be the unique minimum of P. We claim that X* is also a unique minimum of the final QUBO Q = ∑iRi + αP, where α is the posiform coefficients scale factor.

To prove that claim, let \(\hat{X}=\{{\hat{x}}_{1},\ldots,{\hat{x}}_{n}\}\) be a binary assignment of the variables such that \(\hat{X}\,\ne\, {X}^{* }\). Since, by construction, subi(X*) is a minimum of Ri for each i = 1, …, k, it follows that

Furthermore, X* is a unique minimum of P and \(\hat{X}\ne {X}^{* }\). Then

Combining Eq. (5) and Eq. (6), we get

Hence, \(Q({X}^{* }) < Q(\hat{X})\), and since this holds for any \(\hat{X}\,\ne\, {X}^{* }\), X* is a unique minimum of Q.

Measuring the compute time to optimally solve a QUBO: time-to-solution

The compute time required to sample an optimal solution with high confidence, in particular for heuristic probabilistic solvers, is given by the Time-to-solution (TTS) measure90, which is defined as

where Tanneal is the average QPU time used per anneal-readout cycle and p is the proportion of samples that correspond to an optimal solution. Tanneal is measured by dividing the total QPU time (total QPU time is defined as the QPU access time from the D-Wave system, which includes programming time, readout time, and anneal time) by the number of anneals measured in the given dataset. This TTS measure quantifies the expected compute time required to sample an optimal solution at least once, with 99% probability. Note that the only compute time used to measure the TTS is the QPU access time; this does not include local embedding and data processing CPU time.

Simulated annealing

The generated QUBO problems are also solved using simulated annealing77 to compare the performance of quantum annealers against a classical general-purpose solver. Simulated annealing performance is evaluated as a function of the number of Metropolis-Hastings update sweeps, ranging from 1 to 10,000. The comparison uses the Python 3 package dwave-neal91, a C++ implementation with a Python wrapper. The default geometric annealing schedule is used, generating 10,000 samples for each parameter setting and problem instance. In this implementation, a sweep of variable updates is performed in a fixed order for each step of β, where β corresponds to the number of Metropolis-Hastings updates in the simulated annealing schedule. The simulated annealing CPU time is measured as process time.

Gurobi settings

The commercial Gurobi optimization software92 is used to solve the same QUBO instances that are solved using simulated annealing and quantum annealing (up to problem sizes where it is still feasible). Gurobi provides a guarantee of optimality for the found solutions, and can deterministically find an optimal variable assignment of the optimization problem. Importantly, it is possible that Gurobi finds the optimal solution early on in the solution process, but spends most computing time on its verification. However, we do not obtain the two times (for finding the solution and its verification time) separately, and therefore always report the total solve time. This is sensible, since without verification, the Gurobi solution is essentially only a heuristic solution, whereas we require the optimal solution with a guarantee of optimality.

We use Gurobi to solve the QUBO problems as binary Quadratic Programs. Gurobi version 11.0.3 is used for all simulations, and the compute platform is a Red Hat Linux node with Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2695 v4 2.10 GHz. Gurobi settings are all default except the following; a single thread is used, the compute time limit is 4,000,000 s, and the MIP gap is 1e−8. We use Gurobi for the purpose of finding a verified optimal solution of the optimization problem, meaning that the optimality gap has closed to below the MIP gap threshold.

Data availability

Data are available upon request to the authors.

References

Kadowaki, T. & Nishimori, H. Quantum annealing in the transverse ising model. Phys. Rev. E 58, 5355–5363 (1998).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., Gutmann, S. & Sipser, M. Quantum computation by adiabatic evolution. https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0001106 (2000).

Morita, S. & Nishimori, H. Mathematical foundation of quantum annealing. J. Math. Phys. 49, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2995837 (2008).

Das, A. & Chakrabarti, B. K. Colloquium: quantum annealing and analog quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1061 (2008).

Hauke, P., Katzgraber, H. G., Lechner, W., Nishimori, H. & Oliver, W. D. Perspectives of quantum annealing: methods and implementations. Rep. Prog. Phys. 83, 054401 (2020).

Johnson, M. W. et al. Quantum annealing with manufactured spins. Nature 473, 194–198 (2011).

Bunyk, P. I. et al. Architectural considerations in the design of a superconducting quantum annealing processor. IEEE Trans. Appl. Superconductivity 24, 1–10 (2014).

Johnson, M. W. et al. A scalable control system for a superconducting adiabatic quantum optimization processor. Superconductor Sci. Technol. 23, 065004 (2010).

Lanting, T. et al. Entanglement in a quantum annealing processor. Phys. Rev. X 4, 021041 (2014).

Albash, T., Hen, I., Spedalieri, F. M. & Lidar, D. A. Reexamination of the evidence for entanglement in a quantum annealer. Phys. Rev. A 92, 062328 (2015).

King, A. D. et al. Coherent quantum annealing in a programmable 2000-qubit Ising chain. Nat. Phys. 18, 1324–1328 (2022).

King, A. D. et al. Quantum critical dynamics in a 5000-qubit programmable spin glass. Nature 617, 61–66 (2023).

King, A. D. et al. Scaling advantage over path-integral Monte Carlo in quantum simulation of geometrically frustrated magnets. Nat. Commun. 12, 1113 (2021).

King, A. D. et al. Computational supremacy in quantum simulation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.00910 (2024).

Tasseff, B. et al. On the emerging potential of quantum annealing hardware for combinatorial optimization. J Heuristics 30, 325–358 (2022).

Pelofske, E., Bärtschi, A. & Eidenbenz, S. Short-depth QAOA circuits and quantum annealing on higher-order Ising models. npj Quantum Inf. (2024).

Pelofske, E., Bärtschi, A. & Eidenbenz, S. Quantum annealing vs. QAOA: 127 qubit higher-order ising problems on NISQ computers. In Proc. International Conference on High Performance Computing ISC HPC’23, 240–258 (2023).

King, A. D. et al. Quantum annealing simulation of out-of-equilibrium magnetization in a spin-chain compound. PRX Quantum 2, 030317 (2021).

Bauza, H. M. & Lidar, D. A. Scaling advantage in approximate optimization with quantum annealing. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.07184 (2024).

Albash, T. & Lidar, D. A. Adiabatic quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015002 (2018).

Born, M. & Fock, V. Beweis des adiabatensatzes. Z. Phys. 51, 165–180 (1928).

Lucas, A. Ising formulations of many NP problems. Front. Phys. 2, 1–15 (2014).

Boros, E., Hammer, P. & Tavares, G. Preprocessing of unconstrained quadratic binary optimization. Rutcor Res. Rep. RRR 10-2006, 1–58 (2006).

Boros, E., Hammer, P. & Tavares, G. Local search heuristics for Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO). J. Heuristics 13, 99–132 (2007).

Venturelli, D. et al. Quantum optimization of fully connected spin glasses. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031040 (2015).

Pudenz, K. L., Albash, T. & Lidar, D. A. Quantum annealing correction for random ising problems. Phys. Rev. A 91, 042302 (2015).

King, A. D., Hoskinson, E., Lanting, T., Andriyash, E. & Amin, M. H. Degeneracy, degree, and heavy tails in quantum annealing. Phys. Rev. A 93, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.93.052320 (2016).

Mehta, V., Jin, F., De Raedt, H. & Michielsen, K. Quantum annealing for hard 2-satisfiability problems: distribution and scaling of minimum energy gap and success probability. Phys. Rev. A 105, 062406 (2022).

Pelofske, E., Hahn, G. & Djidjev, H. N. Parallel quantum annealing. Sci. Rep. 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08394-8 (2022).

Albash, T. & Lidar, D. A. Demonstration of a scaling advantage for a quantum annealer over simulated annealing. Phys. Rev. X 8, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.8.031016 (2018).

Pelofske, E., Hahn, G. & Djidjev, H. N. Solving larger maximum clique problems using parallel quantum annealing. Quantum Inf. Process. 22, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-023-03962-x (2023).

Pelofske, E., Hahn, G. & Djidjev, H. N. Noise dynamics of quantum annealers: estimating the effective noise using idle qubits. Quantum Sci. Technol. 8, 035005 (2023).

Vyskočil, T., Pakin, S. & Djidjev, H. N. Embedding inequality constraints for quantum annealing optimization. In Proc. First International Workshop on Quantum Technology and Optimization Problems, QTOP 2019, Munich, Germany, March 18, 2019, Proceedings 1, 11–22 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14082-3_2 (Springer, 2019).

Könz, M. S., Lechner, W., Katzgraber, H. G. & Troyer, M. Embedding overhead scaling of optimization problems in quantum annealing. PRX Quantum 2, 040322 (2021).

Cai, J., Macready, W. G. & Roy, A. A practical heuristic for finding graph minors. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1406.2741 (2014).

Lucas, A. Hard combinatorial problems and minor embeddings on lattice graphs. Quantum Inf. Process. 18, 1–38 (2019).

Choi, V. Minor-embedding in adiabatic quantum computation: II. minor-universal graph design. Quantum Inf. Process. 10, 343–353 (2011).

Choi, V. Minor-embedding in adiabatic quantum computation: I. the parameter setting problem. Quantum Inf. Process. 7, 193–209 (2008).

Pearson, A., Mishra, A., Hen, I. & Lidar, D. A. Analog errors in quantum annealing: doom and hope. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 107 (2019).

Lanting, T. et al. Probing environmental spin polarization with superconducting flux qubits. arXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2003.14244 (2020).

Nelson, J., Vuffray, M., Lokhov, A. Y. & Coffrin, C. Single-qubit fidelity assessment of quantum annealing hardware. IEEE Trans. Quantum Eng. 2, 1–10 (2021).

Zaborniak, T. & de Sousa, R. Benchmarking hamiltonian noise in the d-wave quantum annealer. IEEE Trans. Quantum Eng. 2, 1–6 (2021).

Grant, E. & Humble, T. S. Benchmarking embedded chain breaking in quantum annealing. Quantum Sci. Technol. 7, 025029 (2022).

Pelofske, E., Hahn, G. & Djidjev, H. N. Reducing quantum annealing biases for solving the graph partitioning problem. In: Proc. 18th ACM International Conference on Computing Frontiers, CF’21, 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1145/3457388.3458672 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2021).

Vinci, W., Albash, T., Paz-Silva, G., Hen, I. & Lidar, D. A. Quantum annealing correction with minor embedding. Phys. Rev. A 92, 042310 (2015).

Vinci, W., Albash, T. & Lidar, D. A. Nested quantum annealing correction. npj Quantum Inf. 2, 1–6 (2016).

Pudenz, K. L., Albash, T. & Lidar, D. A. Error-corrected quantum annealing with hundreds of qubits. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–10 (2014).

Hen, I. et al. Probing for quantum speedup in spin-glass problems with planted solutions. Phys. Rev. A 92, 042325 (2015).

King, A. D., Lanting, T. & Harris, R. Performance of a quantum annealer on range-limited constraint satisfaction problems. 1502.02098 (2015).

Perera, D., Hamze, F., Raymond, J., Weigel, M. & Katzgraber, H. Computational hardness of spin-glass problems with tile-planted solutions. Phys. Rev. E 101, 023316 (2020).

Wang, W., Mandrà, S. & Katzgraber, H. Patch-planting spin-glass solution for benchmarking. Phys. Rev. E 96, 023312 (2017).

Pei, Y., Manukian, H. & Di Ventra, M. Generating weighted MAX-2-SAT instances with frustrated loops: an RBM case study. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 21, 1–55 (2020).

Hamze, F. et al. From near to eternity: spin-glass planting, tiling puzzles, and constraint-satisfaction problems. Phys. Rev. E 97, 043303 (2018).

Kowalsky, M., Albash, T., Hen, I. & Lidar, D. 3-regular three-XORSAT planted solutions benchmark of classical and quantum heuristic optimizers. Quantum Sci. Technol. 7, 025008 (2022).

Hen, I. Equation planting: a tool for benchmarking ising machines. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 011003 (2019).

Perera, D. et al. Chook—a comprehensive suite for generating binary optimization problems with planted solutions 1–8. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.14344 (2021).

Carleton Coffrin. D-Wave Instance Generator (D-WIG). https://github.com/lanl-ansi/dwig (2022).

King, J. et al. Quantum annealing amid local ruggedness and global frustration. https://arxiv.org/abs/1701.04579 (2017).

Denchev, V. S. et al. What is the computational value of finite-range tunneling? Phys. Rev. X 6, 031015 (2016).

Mandrá, S., Katzgraber, H. G. & Thomas, C. The pitfalls of planar spin-glass benchmarks: raising the bar for quantum annealers (again). Quantum Sci. Technol. 2, 038501 (2017).

Hahn, G., Pelofske, E. & Djidjev, H. N. Posiform planting: generating QUBO instances for benchmarking. Front. Comput. Sci. 5, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2023.1275948 (2023).

Isermann, S. A note on posiform planting (2024).

Aspvall, B., Plass, M. & Tarjan, R. A linear-time algorithm for testing the truth of certain quantified boolean formulas. Inf. Process. Lett. 8, 121–123 (1979).

Dattani, N., Szalay, S. & Chancellor, N. Pegasus:the second connectivity graph for large-scale quantum annealing hardware. https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.07636 (2019).

Boothby, K., Bunyk, P., Raymond, J. & Roy, A. Next-generation topology of d-wave quantum processors. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.00133 (2020).

Boothby, K., King, A. D. & Raymond, J. Zephyr topology of D-Wave quantum processors. https://www.dwavesys.com/media/2uznec4s/14-1056a-a_zephyr_topology_of_d-wave_quantum_processors.pdf (2021).

Katzgraber, H. G., Hamze, F. & Andrist, R. S. Glassy chimeras could be blind to quantum speedup: designing better benchmarks for quantum annealing machines. Phys. Rev. X 4, 021008 (2014).

Weigel, M., Katzgraber, H. G., Machta, J., Hamze, F. & Andrist, R. S. Erratum: glassy chimeras could be blind to quantum speedup: designing better benchmarks for quantum annealing machines [phys. rev. x 4, 021008 (2014)]. Phys. Rev. X 5, 019901 (2015).

Jaumá, G., García-Ripoll, J. J. & Pino, M. Exploring quantum annealing architectures: a spin glass perspective. 2307.13065 (2023).

Matsuda, Y., Nishimori, H. & Katzgraber, H. G. Quantum annealing for problems with ground-state degeneracy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 143, 012003 (2009).

Zhu, Z., Ochoa, A. J. & Katzgraber, H. G. Fair sampling of ground-state configurations of binary optimization problems. Phys. Rev. E 99, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.99.063314 (2019).

Mandrà, S., Zhu, Z. & Katzgraber, H. G. Exponentially biased ground-state sampling of quantum annealing machines with transverse-field driving hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 070502 (2017).

Albash, T., Rønnow, T., Troyer, M. & Lidar, D. Reexamining classical and quantum models for the d-wave one processor: the role of excited states and ground state degeneracy. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 224, 111–129 (2015).

Zhang, B. H., Wagenbreth, G., Martin-Mayor, V. & Hen, I. Advantages of unfair quantum ground-state sampling. Sci. Rep. 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01096-6 (2017).

Boixo, S., Albash, T., Spedalieri, F. M., Chancellor, N. & Lidar, D. A. Experimental signature of programmable quantum annealing. Nat. Commun. 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3067 (2013).

Könz, M. S., Mazzola, G., Ochoa, A. J., Katzgraber, H. G. & Troyer, M. Uncertain fate of fair sampling in quantum annealing. Phys. Rev. A 100, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.100.030303 (2019).

Kirkpatrick, S., Gelatt Jr, C. D. & Vecchi, M. P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 220, 671–680 (1983).

Pelofske, E. Comparing three generations of D-Wave quantum annealers for minor embedded combinatorial optimization problems. Quantum Science and Technology, 10, https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/adb029 (2025).

Willsch, D. et al. Benchmarking advantage and D-Wave 2000Q quantum annealers with exact cover problems. Quantum Inf. Process. 21, 141 (2022).

Morrell, Z. et al. Signatures of open and noisy quantum systems in single-qubit quantum annealing. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 034053 (2023).

Grant, E., Humble, T. S. & Stump, B. Benchmarking quantum annealing controls with portfolio optimization. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 014012 (2021).

Gilbert, V., Rodriguez, J. & Louise, S. Benchmarking quantum annealers with near-optimal minor-embedded instances. https://arxiv.org/html/2405.01378v1 (2024).

Boros, E. & Hammer, P. Pseudo-boolean optimization. Discret. Appl Math. 123, 155–225 (2002).

Hagberg, A. A., Schult, D. A. & Swart, P. J. Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using NetworkX. In: Proc. 7th Python in Science Conference SciPy’08, 11–15. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/960616 (2008).

Kernighan, B. W. & Lin, S. An efficient heuristic procedure for partitioning graphs. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 49, 291–307 (1970).

Pelofske, E., Hahn, G., O’Malley, D., Djidjev, H. N. & Alexandrov, B. S. Quantum annealing algorithms for boolean tensor networks. Sci. Rep. 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12611-9 (2022).

Albash, T., Vinci, W., Mishra, A., Warburton, P. A. & Lidar, D. A. Consistency tests of classical and quantum models for a quantum annealer. Phys. Rev. A 91, 042314 (2015).

IBM ILOG CPLEX. V12.10.0: User’s Manual for CPLEX. 46, 157 (International Business Machines Corporation, 2019).

Eén, N. & Sörensson, N. MiniSat solver. http://minisat.se (2023).

Rønnow, T. F. et al. Defining and detecting quantum speedup. Science 345, 420–424 (2014).

D-Wave Systems. Simulated annealing D-Wave Github. https://github.com/dwavesystems/dwave-neal (2024).

Gurobi Optimization, LLC. Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual. https://www.gurobi.com (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy through the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Los Alamos National Laboratory is operated by Triad National Security, LLC, for the National Nuclear Security Administration of U.S. Department of Energy (Contract No. 89233218CNA000001). This research used resources provided by the Los Alamos National Laboratory Institutional Computing Program, which is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract No. 89233218CNA000001. Research presented in this article was supported by the NNSA’s Advanced Simulation and Computing Beyond Moore’s Law Program at Los Alamos National Laboratory and by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program of Los Alamos National Laboratory under project number 20240032DR. This research used resources provided by the Darwin testbed at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) which is funded by the Computational Systems and Software Environments subprogram of LANL’s Advanced Simulation and Computing program (NNSA/DOE). The work of H.D. was also supported by the Centre of Excellence in Informatics and ICT established under the Grant No BG05M2OP001-1.001-0003, financed by the Science and Education for Smart Growth Operational Program and co-financed by the European Union through the European Structural and Investment funds. LANL report number LA-UR-24-26772.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.P. performed all simulations and optimization problem instance generation. G.H. and E.P. wrote the source code used in the problem instance generation. E.P. wrote the source code for the simulations. G.H. conceived of the core posiform planting algorithm, and its extensions. H.D. and G.H. devised the key algorithm used in this study where posiform planting could be made computationally harder using random QUBOs. E.P. prepared all figures in the manuscript. E.P and G.H. drafted the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the experimental design of the simulations and problem instances used in the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pelofske, E., Hahn, G. & Djidjev, H.N. Increasing the hardness of posiform planting using random QUBOs for programmable quantum annealer benchmarking. npj Unconv. Comput. 2, 17 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44335-025-00032-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44335-025-00032-6