Abstract

This work presents a hardware-algorithm co-designed framework for neuromorphic computing, enabling efficient supervised learning in spike-based neural architectures. First, synaptic updates are reformulated as low-rank outer products of forward spike vectors and backward error gradients via singular value decomposition (SVD), enabling direct parallelization on 1T1R arrays. Second, a stochastic computing scheme replaces conventional sequential updates with probabilistic pulse-driven modulation, achieving one-step full-matrix synaptic updates. Third, gradient stabilization techniques mitigate training instability in deep SNNs by addressing silent neuron and gradient explosion issues. Evaluated on the ASL-DVS dynamic gesture recognition task, the framework maintains 84.7% accuracy with hardware-realistic 1T1R characteristics, while drastically reducing hardware update steps. This demonstrates a synergistic hardware-algorithm co-design where SVD-based approximation enables parallelization, stochastic computing achieves one-step updates, and gradient stabilization ensures trainability, advancing practical neuromorphic intelligence for edge sensing systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuromorphic computing, inspired by the brain’s architecture and computational principles, offers a paradigm shift for processing sensory data streams. Its core tenets include event-driven, sparse computation and inherent parallelism, enabling efficient handling of spatiotemporal information prevalent in the real world, such as the asynchronous event streams generated by Dynamic Vision Sensors (DVS). Unlike conventional frame-based data, DVS asynchronously captures brightness changes with microsecond resolution, producing highly sparse spatiotemporal event streams. Among various neuromorphic models, spiking neural networks (SNNs), which communicate through temporal spike events, stand out due to their direct compatibility with event-driven neuromorphic hardware architectures1. The sparse nature of spikes significantly reduces redundant computations, crucial for low-power real-time processing, while neuronal dynamics directly model temporal correlations within event streams, providing efficient solutions for dynamic tasks like gesture recognition2,3,4. Critically, the parallelism and efficiency of weight update strategies within these neuromorphic architectures directly determine the energy efficiency and latency of hardware systems5.

Training algorithms with spikes primarily fall into two categories: indirect and direct training. Indirect training converts pre-trained artificial neural networks (ANNs) into SNNs, leveraging mature ANN frameworks6,7. However, this paradigm fundamentally operates as static mapping of offline data8, which exhibits inherent incompatibility with the spatiotemporal nature of DVS event streams. Specifically, indirect training fails to capture temporal information in event data and often loses dynamic features of spike events during conversion, leading to compromised recognition performance. In contrast, unsupervised direct training methods like Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP) have been widely explored for their hardware-friendly local synaptic rules9,10. Nevertheless, the absence of a global credit assignment mechanism in STDP limits its scalability for complex tasks11. Therefore, developing supervised training methods that combine temporal sensitivity, learning efficacy, and hardware efficiency is imperative for DVS-driven applications.

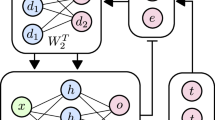

Spike-based Backpropagation (spikeBP), integrating backpropagation’s credit assignment with spike timing coding, offers a promising solution(Fig. 1a). Its strengths lie in two aspects: first, the well-established gradient framework ensures training stability in deep SNNs; second, spike-driven sparse computation substantially reduces hardware overhead for synaptic updates12,13,14,15. However, when deploying spikeBP on neuromorphic hardware, two critical bottlenecks emerge: (1) silent-neuron-induced gradient loss and critical-slope-induced gradient explosion hinder training efficiency in deep networks16,17, and (2) element-wise synaptic updates are incompatible with the highly parallel architecture of memristor crossbars(Fig. 1b). Notably, in traditional deep neural networks (DNNs), memristor crossbars achieve parallel weight updates through outer products of forward signal vectors and backward error vectors—deterministic or stochastic encoding of these vectors enables natural analog multiplication via memristor conductance modulation18,19,20. However, spikeBP’s synaptic updates involve nonlinear interactions between presynaptic and postsynaptic spike timings, preventing direct mapping to vector outer products and forming a core obstacle for hardware optimization(Fig. 1c).

a ASL-DVS event processing pipeline: Dynamic hand gesture (left) is encoded into spatiotemporal spikes and processed by SNN (middle). Layers (blue/red neurons) encode update pulse trains to a memristor crossbar (right), enabling parallel hardware updates. b Limitations of conventional DNN frameworks: Analog activations with off-chip outer product computation and row/column-wise weight updates. c Proposed SNN parallel framework: Spike train inputs (LIF neurons) with one-step in-memory crossbar updates via voltage pulses, fusing outer product computation with synaptic modulation.

In this work, we propose a hardware-algorithm co-design approach to address these challenges, modifying the spikeBP algorithm for compatibility with parallel neuromorphic hardware based on one-transistor one-memristor (1T1R) arrays. First, singular value decomposition (SVD) is employed to approximate synaptic weight matrices as outer products of forward spike vectors and backward error vectors, enabling direct mapping to parallel multiply-accumulate operations. Second, stochastic computing techniques transform outer product operations into probabilistic pulse superposition, achieving one-step full-matrix updates with reduced hardware latency. Additionally, gradient clipping and forced firing mechanisms are designed to mitigate silent neuron and surge issues in large-scale network training. Crucially, we validate the proposed modifications through both algorithmic evaluation and 1T1R memristor device characterization integrated into the stochastic update scheme. Experiments demonstrate that our co-design achieves 92% accuracy under ideal simulation and 84.7% accuracy with hardware-realistic 1T1R characteristics on the ASL-DVS dynamic gesture recognition task, validating both algorithmic efficacy in event-driven scenarios and practical feasibility for parallel neuromorphic implementation.

Results

Neural dynamics and learning challenge

The core challenge in neuromorphic hardware implementation stems from the fundamental mismatch between spike-based neural dynamics and parallel computing architectures. We adopt the Spike Response Model (SRM)12 for its analytical tractability while maintaining equivalence to Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neurons under rectangular postsynaptic potentials. This ensures compatibility with standard neuromorphic hardware implementations9.

The membrane potential dynamics follow:

where uj is the membrane potential, wij synaptic weights, ε the presynaptic potential kernel.

The spike timing-dependent weight update in traditional spikeBP follows:

where ti, tj are pre- and postsynaptic spike times, and δj the backpropagated error.

This element-wise update presents two hardware bottlenecks: (1) ε(tj − ti) couples pre- and postsynaptic events (Fig. 2a, b) and prevents explicit decomposition into separable vectors. (2) It inherently suffers from the learning challenges noted in the “Introduction” section: silent-neuron-induced gradient loss and critical-slope-induced gradient explosion. Our key insight recognizes that while exact decoupling is impossible, the low-rank structure of spike timing matrices enables efficient approximation. As visualized in Fig. 2c, rectified timing differences \({\boldsymbol{T}}={[({t}_{j}-{t}_{i})\vee 0]}_{i\times j}\) exhibit: (1) Linear manifolds along presynaptic dimensions. (2) Shift invariance relative to postsynaptic baselines. This geometric regularity motivates rank-1 approximation via SVD, while the gradient stability challenges are addressed through our Ensemble Surrogate Gradients (Section “Ensemble of Surrogate Gradients”).

a SRM neuron dynamics: Presynaptic spikes x1, x2, x3 are weighted by synapses w1, w2, w3, integrated as dendritic potential u = ∑xiwi, and transformed to somatic output f(u). The inset illustrates spike generation when membrane potential crosses threshold θ. b Temporal encoding of PSP amplitudes: Postsynaptic spike timing tj samples amplitudes from presynaptic traces (rows 1–3) at tj, forming the matrix ε(tj − ti). c Low-rank geometric structure: Left: Presynaptic timings ti form a linear manifold in j-dimensional space. Right: Rectified timing differences ti − tj shift rows along axes while preserving linearity. d SVD validation: Data points (blue) of different inputs cluster along the principal singular vectors (purple line) with rank-1 decomposition.

Approximate synaptic update matrix as outer product of forward and backward vectors

To enable hardware-friendly parallel synaptic updates, we first reformulate the weight update matrix in spikeBP into an outer product form compatible with memristor crossbars. In analog neural networks, synaptic updates are expressed as the outer product of forward activations x and backward errors δ21:

enabling parallel updates by applying x and δ as row/column voltage pulses (Fig. 1c). First, two vectors of write voltages proportional to xi and δj are generated separately, and then they are imposed to the line and column ends of the memristor crossbar, respectively. Owing to the multiplication effect, the memristor element Gij in the crossbar would receive a programming voltage proportional to xiδj and then the conductance change ΔGij would be proportional to xiδj too according to the physical properties of memristor conductance tuning. In this way, the whole synaptic weight matrix would be updated in a one-step manner, harvesting the ultrahigh limit of parallel computing22,23.

However, spikeBP introduces a critical divergence: updates depend on the nonlinear coupling of spike timing differences ε(tj − ti) (Fig. 2a), defined as24:

where ε(tj − ti) encodes both the temporal interaction (tj − ti) and its alpha-shaped postsynaptic potential (PSP). As shown in Fig. 2b, ε(tj − ti) forms a non-factorizable matrix where each element depends on presynaptic (ti) and postsynaptic (tj) spike times, preventing direct vector outer product decomposition.

To resolve this, we decompose ε(tj − ti) into separable components. First, the alpha function’s exponential structure allows splitting into presynaptic- and postsynaptic-dependent terms:

Here, ε(tj − ti) combines rectified timing differences (tj − ti) ∨ 0 and exponential decay terms. While the exponential components naturally decouple into pre- and postsynaptic vectors, the rectified matrix \({\boldsymbol{T}}={[({t}_{j}-{t}_{i})\vee 0]}_{i\times j}\) requires dimensionality reduction to align with hardware parallelism.

The geometric intuition behind this reduction is illustrated in Fig. 2c. Each row of T corresponds to a presynaptic neuron’s timing differences across postsynaptic neurons. In the absence of postsynaptic shifts (tj = 0), T reduces to \({[-{t}_{i}]}_{i\times j}\), forming a linear manifold in the j-dimensional space (left panel). Introducing postsynaptic timings tj shifts each row by − ti along respective axes (right panel), yet preserves an approximately linear structure due to the dominance of presynaptic timing ti. This near-linearity justifies approximating T via rank-1 SVD:

where p (scaled left singular vector) and q (right singular vector) capture the principal variance, and qb accounts for residual biases.

Combining SVD with exponential terms, the synaptic update rule becomes:

with the presynaptic spike vector x, backpropagated error vector δ, presynaptic bias vector xb, and error bias vector δb defined as:

Here, the bias vectors xb and δb compensate for the approximations inherent in the rank-1 SVD, ensuring the fidelity of the decomposed update rule.

As visualized in Fig. 2d, the rectified timing differences T cluster tightly around the principal axis, confirming that the rank-1 approximation captures the main variance (eigenvalue ratio). This ensures minimal accuracy loss while enabling outer product-based updates. By applying x and δ as voltage pulses to 1T1R arrays, the entire synaptic matrix is updated in one step, achieving parallelism comparable to DNNs.

The average relative reconstruction error of this approximation across the dataset is ~4.3%, which justifies the trade-off between the accuracy and hardware efficiency, as evidenced by the minimal accuracy drop in network performance (Fig. 5).

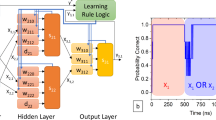

One-step implementation via stochastic computing

Building upon the SVD-based outer product approximation of synaptic updates, we further propose a stochastic computing scheme to enable one-step parallel updates on 1T1R arrays. The core challenge lies in mapping the multiplicative relationship ΔGij ∝ xiδj to the physical superposition of voltage pulses. Traditional deterministic pulse schemes require designing 64 distinct pulse patterns for 6-bit precision, which imposes prohibitive hardware overheads18. To address this, our method comprises three stages: SVD decomposition, probabilization, and stochastic encoding (Fig. 3a–c), leveraging statistical properties of random pulses to approximate outer-product operations.

a SVD-based decomposition: Synaptic update matrix approximated as outer product of forward spike vectors x and backward error vectors δ. b Probabilization: Normalization and truncation of x and δ to [−1, 1] and [0, 1], with heatmaps d illustrating truncation effects. c Stochastic encoding in 1T1R crossbar: Independent random pulse trains with probabilities proportional to \({x}_{i}^{prob}\) (word lines) and \({\delta }_{j}^{prob}\) (bit lines). Overlapping pulses (purple) trigger updates. e Example pulse sequences representing probabilities. f Update conditions: Only simultaneous gate and drain pulses induce conductance change. g Ideal simulation: Theoretical weight updates (red) versus stochastic coding results (blue) under linear memristor assumption.

Probabilization with variable cutting

Given the unbounded dynamic range of SVD-derived vectors in Eqs. (7) and (8), we normalize them to probability-compatible ranges:

where scaling factors sx, sδ, sδb, sxb are determined from layer-wise statistics. This preserves gradient distributions while constraining values to [−1, 1] for signed terms and [0, 1] for xb. The truncation effect for xb is explicitly visualized in Fig. 3d (bottom heatmap).

1T1R stochastic encoding

The normalized \({x}_{i}^{prob}\) and \({\delta }_{j}^{prob}\) are encoded as independent stochastic bitstreams (Fig. 3e). Gate pulses are applied to rows with the probability \({x}_{i}^{prob}\), while drain pulses are applied to columns with the probability \({\delta }_{j}^{prob}\). Crucially, conductance changes occur exclusively during simultaneous gate and drain pulses (Vg&Vd state in Fig. 3f). Bipolar updates are implemented through a differential pair architecture: Each synaptic weight wij is physically represented as \({G}_{ij}^{+}-{G}_{ij}^{-}\), with positive updates applying SET pulses to \({G}_{ij}^{+}\) and negative updates (\({x}_{i}^{prob} < 0\)) to \({G}_{ij}^{-}\).

Ideal simulation validation

Figure 3g validates the stochastic encoding scheme under ideal memristor assumptions, where each coincident pulse induces fixed conductance change ΔG0 and the length of bitstreams is 50. The theoretical update surface (red) follows ΔG ∝ P(x) ⋅ P(δ), while stochastic simulation (blue) shows close alignment with minor discretization errors at low probabilities. Crucially, the ensemble average preserves the multiplicative relationship \({\mathbb{E}}[\Delta G]\propto P(x)\cdot P(\delta )\). Remarkably, even with minimal pulse sequences (sequence length = 1), statistical averaging across training epochs maintains learning efficacy.

This temporal accumulation effect allows ultra-short programming cycles without compromising convergence, a key advantage for event-driven systems. The physical realization and experimental validation of this scheme will be detailed in the next section.

1T1R memristor array characterization

To physically validate the proposed stochastic update scheme, we fabricated and characterized a 1-kb (32 × 32) 1T1R memristor array with TiN/TaOx/HfO2/TiN heterostructure devices. A micrograph of the fabricated array is shown in Fig. 4a, where word lines (WL) and source lines connect to transistor gates and sources, respectively, and bit lines (BL) connect to memristor top electrodes. The 1T1R configuration provides essential selection capability for parallel programming while suppressing sneak currents. (For full characterization data, including LTD behavior and endurance tests, see Supplementary Fig. 1)

a Micrograph of 1-kb (32 × 32) 1T1R array. b Conductance modulation: LTP induced by 50 “11” pulses (10 μs) and conductance stability under non-update conditions (“00”, “01”, “10”) at three conductance levels. c Stochastic update implementation: Crossbar rows receive gate pulses (Vg = 1.2 V) with probability P(x), columns receive drain pulses (Vd = 0.8 V) with probability P(δ). Update occurs only during coincident “11” pulses. d Measured conductance trajectory under stochastic programming. e Theoretical (red) vs. measured (blue) conductance changes across probability space.

Controlled conductance modulation

Figure 4b demonstrates reliable conductance modulation under various pulse conditions. Long-term potentiation (LTP) was achieved using 50 consecutive “11” pulses (10 μs width), where gate voltage (Vg = 1.2 V) activates the transistor and drain voltage (Vd = 0.8 V) induces SET switching. Crucially, we verified immunity to unintended updates: At three representative conductance levels (8 kΩ, 12 kΩ, and 20 kΩ), non-update pulse patterns (“01”: drain-only pulse, “10”: gate-only pulse, “00”: no pulses) produced negligible conductance changes, confirming selective update only during coincident “11” events.

Stochastic update implementation

The physical implementation of our probabilistic update scheme, based on the characterized properties of our 1T1R array, is illustrated in Fig. 4c. The schematic corresponds to the array architecture shown in the micrograph (Fig. 4a), where: 1, Rows receive gate pulses (Vg = 1.2 V) on the G1-Gn lines (blue, corresponding to word lines, WL) with occurrence probability \(P({x}_{i}^{prob})\). 2, Columns receive drain pulses (Vd = 0.8 V) on the D1-Dn lines (red, corresponding to bit lines, BL) with occurrence probability \(P({\delta }_{j}^{prob})\). Memristor conductance changes occur exclusively when both row and column pulses coincide (“11” state), implementing the multiplicative relationship \(\Delta {G}_{ij}\propto P({x}_{i}^{prob})\cdot P({{\delta }_{j}}^{prob})\).

Stochastic update validation

Figure 4d shows a representative conductance trajectory under stochastic encoding (P(x) = 0.4, P(δ) = 0.7). The stepwise increases correspond to “11” pulse occurrences, demonstrating the cumulative nature of probabilistic updates. Statistical characterization across the probability space (Fig. 4e) reveals close agreement between theoretical expectations (red surface) and statistical measured conductance changes (blue surface). Despite inherent device variability, the ensemble behavior preserves the multiplicative relationship essential for outer product approximation, with \({\mathbb{E}}[\Delta G]\propto P(x)\cdot P(\delta )\).

ASL-DVS gesture recognition

Evaluated on ASL-DVS with a VGG16 SNN, the original SpikeBP achieves 97.1% accuracy. SVD approximation introduces marginal degradation (96.8%), while probabilization and stochastic encoding reduce accuracy to 92% (Fig. 5).When incorporating measured 1T1R device characteristics, the accuracy stabilizes at 84.7%. This trade-off enables one-step full-matrix updates, reducing synaptic update latency while preserving event-driven processing capabilities.

Test accuracy of a VGG16 SNN under progressive hardware-compatible modifications. Light-colored bands around each curve represent ±1 standard deviation across 5 training trials, reflecting training stability. While SVD introduces minimal accuracy loss, probabilization and stochastic encoding trade marginal degradation for parallel updates, critical for event-driven hardware deployment, with the complete system achieving 84.7% accuracy under device constraints.

Discussion

Our work establishes a hardware-algorithm co-design framework that reconciles the temporal sensitivity of SNNs with the parallelism constraints of neuromorphic hardware. By integrating SVD and stochastic computing, the proposed spikeBP variant achieves one-step synaptic updates on 1T1R arrays, reducing latency while maintaining functionality. This contrasts with conventional ANN-based approaches that discard temporal spike correlations or STDP methods lacking global optimization. The SVD approximation, which introduces an ~4.3% temporal reconstruction error, results in only a minor network accuracy drop (96.8% vs. 97.1%). This effective trade-off enables direct mapping to analog in-memory computing architectures, which is critical for energy-efficient event processing.

The stochastic encoding scheme bridges algorithmic gradients to device physics. It translates gradients into probabilistic pulse coincidence, circumventing the precision bottlenecks of deterministic pulse designs. This scheme achieves 84.7% accuracy on the ASL-DVS task when incorporating measured device characteristics. We conducted a controlled analysis to dissect the sources of this accuracy degradation. Our analysis shows that deterministic nonlinearity in conductance modulation is a primary bottleneck. This nonlinearity, which we fitted from device data (Supplementary Fig. 2), reduces accuracy to 87.0%. Device-level variability account for the remaining decrease to 84.7%.

This result underscores that the performance gap stems primarily from the non-ideal characteristics of the 1T1R devices. While our stochastic computing scheme averages out some of the stochastic noise over multiple pulses and updates, the inherent device-to-device variability and non-linearity ultimately limit the precision of the synaptic weights. We anticipate that future advancements in memristor technology, focusing on improved linearity and uniformity, will close this accuracy gap.

This trade-off balances computational fidelity with hardware feasibility, a necessity for large-scale SNN deployment. Notably, our method preserves temporal coding capabilities essential for DVS applications, unlike ANN-SNN conversions that statically map frame-based features. Physical validation through 1T1R device characterization confirms the feasibility of the proposed parallel update mechanism. Our framework demonstrates that SNN training can be both temporally precise and hardware-efficient, advancing toward real-world event-driven intelligence.

Method

Dataset

We evaluate our model on the ASL-DVS dataset25, a large scale event-based dataset for American Sign Language recognition. It comprises 24 classes (letters A-Y, excluding J). In our work, we utilize a version of the dataset containing a total of 113,645 samples, which we split into 96,899 samples for training and 16,746 for testing. The data was recorded using a DAVIS240c event camera, with each sample representing a spatiotemporal event stream ~100 ms in duration, generated from dynamic hand gestures. This dataset presents a challenging task for event-based classifiers due to the subtle differences between certain gestures, making it a suitable benchmark for evaluating the temporal processing capabilities of our proposed SNN.

Ensemble of Surrogate Gradients (ESG)

This work implements forward propagation based on the SRM, where presynaptic voltage pulses are weighted by the kernel function x and integrated into the postsynaptic neuron’s dendritic potential uj = ∑wijxi. When uj exceeds the threshold θ, the neuron emits a spike via the non-differentiable function f(u). To align with hardware implementation requirements, the SRM adopts an integral form equivalent to the LIF neuron model26, utilizing existing LIF neuron circuit architectures to achieve event-driven low-power computation (as shown in Fig. 2a).

The error function is defined as the squared difference between the output spike timings tj and target timings \({t}_{j}^{a}\): \(E={\sum }_{j}{({t}_{j}-{t}_{j}^{a})}^{2}\). Following gradient descent, the synaptic weight update rule is:

where the backpropagated error δi is computed as:

Here, \(\frac{\partial {t}_{j}}{\partial {u}_{j}\,({t}_{j})}\) quantifies the sensitivity of spike timing to membrane potential and is critical for gradient stability. In the traditional SpikeProp algorithm, this term is approximated as the instantaneous rate of membrane potential change at the threshold crossing:

where the negative sign arises from the physical mechanism where membrane potential increase (Δuj > 0) accelerates spike timing (Δtj < 0). However, this approximation introduces two hardware deployment challenges:

1. Silent Neuron Problem: When uj fails to reach θ, \(\frac{\partial {t}_{j}}{\partial {u}_{j}({t}_{j})}\) becomes undefined, causing gradient loss. 2. Gradient Surge Problem: If uj barely crosses θ (\({\frac{\partial {u}_{j}(t)}{\partial t}| }_{t={t}_{j}}\approx 0\)), \(\frac{\partial {t}_{j}}{\partial {u}_{j}({t}_{j})}\) diverges to infinity, triggering gradient explosion.

Existing methods mitigate these issues through weight constraints16, adaptive learning rates27, or rectified postsynaptic potential functions15, but they struggle to balance training stability in large-scale networks with hardware compatibility. For example, regularization techniques28 require computing first-order derivatives of membrane potential, increasing hardware timing control complexity, while neuron model modifications29 rely on non-standard circuits, limiting generalizability.

To address these challenges, we propose the Ensemble of Surrogate Gradients (ESG), which employs piecewise approximations to reconcile hardware constraints with temporal event processing:

Forced Firing operates as follows: For silent neurons, the required membrane potential rise rate \(\frac{\theta -{u}_{j}^{\max }}{T-{t}_{j}^{\max }}\) within the remaining time window \(T-{t}_{j}^{\max }\) can be estimated using the peak potential \({u}_{j}^{\max }\) and its timing \({t}_{j}^{\max }\). However, real-time monitoring of \({u}_{j}^{\max }\) and \({t}_{j}^{\max }\) is impractical in hardware. ESG simplifies this to a statistical ensemble average \(\frac{\theta }{T}\), assuming a linear rise from zero to θ within a fixed window T. This simplification avoids real-time tracking while covering diverse neuron dynamics through an “ensemble” averaging concept.

Surge Suppression sets a lower bound k (determined from ASL-DVS dataset statistics) to cap gradient magnitudes when \({\frac{\partial {u}_{j}(t)}{\partial t}| }_{t={t}_{j}} < k\), preventing explosions.

For the ASL-DVS dynamic gesture recognition task, a VGG16-based SNN adopts a hybrid training strategy: Fixed front layers extract features from event streams, while the last two layers are fine-tuned via ESG and stochastic updating. ESG’s hardware-friendliness is reflected in the determination of k and T through statistical and predefined methods, eliminating the need for real-time monitoring of membrane potential change rates and peak values.

The efficacy of ESG is evidenced by the 97.1% baseline accuracy (Fig. 5, “Original”), which provides a stable foundation for subsequent SVD approximation and stochastic encoding optimizations.

The necessity of the ESG mechanism is empirically validated through an ablation study (Supplementary Fig. 3). Under hardware-realistic conditions with device non-idealities, disabling ESG leads to severe training failure and a significant drop in final accuracy. This result confirms that hardware imperfections exacerbate gradient instability issues, and that the ESG mechanism is essential for achieving stable convergence in a parallel hardware implementation.

The 1T1R array fabrication and measurement

The 1T1R memristor array was fabricated using standard 130 nm CMOS technology, comprising 1024 (32 × 32) devices with integrated control circuits30. The memristor heterostructure consists of TiN/TaOx/HfO2/TiN, deposited in sequence: TiN bottom electrode, HfO2 switching layer, TaOx interface layer, and TiN top electrode. Device patterning defined 0.5 μm × 0.5 μm cells through lithography, followed by SiO2 dielectric deposition and CMP planarization. Final interconnects were formed via aluminum metallization and etch processes.

Electrical characterization employed a Keysight B1530 test system. Gate pulses (20 μs) were applied to WL, while drain pulses (10 μs) were applied to BL. Pulse synchronization ensured simultaneous “11” state application for reliable SET switching during coincidence events. This configuration directly implements the stochastic update scheme described in the “One-step implementation via Stochastic Computing” section.

Data availability

The ASL-DVS dataset analyzed during the current study is publicly available from the original authors' repository: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1tK5OY3pkjppYwAnLF8bnxGdaFbYEA8iY?usp=sharing.

References

Schuman, C. D. et al. Opportunities for neuromorphic computing algorithms and applications. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 10–19 (2022).

Gallego, G. et al. Event-based vision: a survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 154–180 (2020).

Izhikevich, E. M. Simple model of spiking neurons. IEEE Trans. neural Netw. 14, 1569–1572 (2003).

Neftci, E. O., Mostafa, H. & Zenke, F. Surrogate gradient learning in spiking neural networks: bringing the power of gradient-based optimization to spiking neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 36, 51–63 (2019).

Sebastian, A., Le Gallo, M., Khaddam-Aljameh, R. & Eleftheriou, E. Memory devices and applications for in-memory computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 529–544 (2020).

Pérez-Carrasco, J. A. et al. Mapping from frame-driven to frame-free event-driven vision systems by low-rate rate coding and coincidence processing–application to feedforward convnets. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35, 2706–2719 (2013).

Stöckl, C. & Maass, W. Optimized spiking neurons can classify images with high accuracy through temporal coding with two spikes. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 230–238 (2021).

Diehl, P. U., Zarrella, G., Cassidy, A., Pedroni, B. U. & Neftci, E. Conversion of artificial recurrent neural networks to spiking neural networks for low-power neuromorphic hardware. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Rebooting Computing (ICRC) 1–8 (IEEE, 2016).

Davies, M. et al. Loihi: a neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning. IEEE Micro 38, 82–99 (2018).

Schemmel, J. et al. A wafer-scale neuromorphic hardware system for large-scale neural modeling. In Proc. IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) 1947–1950 (IEEE, 2010).

Bengio, Y., Lee, D.-H., Bornschein, J., Mesnard, T. & Lin, Z. Towards biologically plausible deep learning. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1502.04156 (2015).

Bohte, S. M., Kok, J. N. & La Poutre, H. Error-backpropagation in temporally encoded networks of spiking neurons. Neurocomputing 48, 17–37 (2002).

Taherkhani, A. et al. A review of learning in biologically plausible spiking neural networks. Neural Netw. 122, 253–272 (2020).

Zenke, F. & Ganguli, S. Superspike: supervised learning in multilayer spiking neural networks. Neural Comput. 30, 1514–1541 (2018).

Zhang, M. et al. Rectified linear postsynaptic potential function for backpropagation in deep spiking neural networks. IEEE Trans. neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33, 1947–1958 (2021).

Takase, H. et al. Obstacle to training spikeprop networks-cause of surges in training process-. In Proc. International Joint Conference on Neural Networks 3062–3066 (IEEE, 2009).

Shrestha, S. B. & Song, Q. Robustness to training disturbances in spikeprop learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 29, 3126–3139 (2017).

Burr, G. W. et al. Experimental demonstration and tolerancing of a large-scale neural network (165 000 synapses) using phase-change memory as the synaptic weight element. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 62, 3498–3507 (2015).

Xu, Z. et al. Parallel programming of resistive cross-point array for synaptic plasticity. Procedia Comput. Sci. 41, 126–133 (2014).

Gokmen, T., Onen, M. & Haensch, W. Training deep convolutional neural networks with resistive cross-point devices. Front. Neurosci. 11, 538 (2017).

LeCun, Y., Touresky, D., Hinton, G. & Sejnowski, T. A theoretical framework for back-propagation. In Proc. 1988 Connectionist Models Summer School, Vol. 1, 21–28 (Morgan Kaufmann, San Mateo, CA, USA, 1988).

Gokmen, T. & Vlasov, Y. Acceleration of deep neural network training with resistive cross-point devices: design considerations. Front. Neurosci. 10, 333 (2016).

Agarwal, S. et al. Achieving ideal accuracies in analog neuromorphic computing using periodic carry. In Proc. Symposium on VLSI Technology, T174–T175 (IEEE, 2017).

Comsa, I. M. et al. Temporal coding in spiking neural networks with alpha synaptic function. In ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 8529–8533 (IEEE, 2020).

Bi, Y. et al. Graph-based object classification for neuromorphic vision sensing. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (IEEE, 2019).

Burkitt, A. N. A review of the integrate-and-fire neuron model: I. homogeneous synaptic input. Biol. Cybern. 95, 1–19 (2006).

McKennoch, S., Liu, D. & Bushnell, L. G. Fast modifications of the spikeprop algorithm. In The 2006 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Network Proceedings, 3970–3977 (IEEE, 2006).

Lee, J. H., Delbruck, T. & Pfeiffer, M. Training deep spiking neural networks using backpropagation. Front. Neurosci. 10, 508 (2016).

Hong, C. et al. Training spiking neural networks for cognitive tasks: a versatile framework compatible with various temporal codes. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 31, 1285–1296 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Memristive floating-point fourier neural operator network for efficient scientific modeling. Sci. Adv. 11, eadv4446 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U24A20303, 92164204, and 62374063) and the Science and Technology Major Project of Hubei Province (No. 2022AEA001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z. and Y.H. conceived the research idea and supervised the project. D.Z. designed the methodology, implemented the algorithms, performed simulations, analyzed results, and wrote the original manuscript. Y.X. and Y.L. designed and conducted the memristor device characterization experiments. J.F. prepared Figures 2 and 3. Y.Z., B.G., Z.Y., and X.M. provided critical insights on neuromorphic system design and applications. V.Z., Z.Y., and H.T. contributed to technical discussions and results validation. Y.H. and X.M. acquired funding and supervised the research direction. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, D., Zhou, Y., Zhao, V. et al. Modified spike backpropagation design towards highly parallelable hardware implementation. npj Unconv. Comput. 3, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44335-025-00046-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44335-025-00046-0