Abstract

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) comprise a family of 17 enzymes were initially identified for their essential roles in DNA damage repair and maintenance of genomic stability. Emerging evidence has unveiled their critical involvement in various liver diseases, including viral hepatitis, metabolic disorders, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. This review summarizes PARPs’ roles in liver diseases and the evidence supporting PARP inhibitor therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver disease represents a significant global health challenge, contributing to substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide1. It encompasses a broad spectrum of etiologies and pathogenic mechanisms, including viral hepatitis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), alcoholic liver disease (ALD), drug-induced liver injury, autoimmune liver diseases (AILD), liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Chronic liver diseases are estimated to affect hundreds of millions of individuals globally, with viral hepatitis, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC ranking among the leading causes of liver-related deaths. The pathogenesis of these diseases involves a complex interplay of factors, such as viral infections, metabolic dysregulation, oxidative stress, immune dysfunction, and genetic predisposition1. Despite advancements in diagnostic methods and therapeutic strategies, many liver diseases remain difficult to manage, particularly in advanced stages. For instance, liver fibrosis and HCC are associated with poor prognosis, owing to limited treatment options, late diagnosis, and high rates of disease recurrence. Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms driving liver diseases and identifying novel therapeutic targets are essential for improving clinical outcomes1,2.

The liver is the largest internal organ in the body and plays a central role in maintaining systemic homeostasis. It is involved in a wide array of physiological processes, including nutrient metabolism, detoxification, protein synthesis, and immune regulation. Structurally, the liver comprises several cell types, each contributing to its overall function. The hepatic lobule, which serves as the liver’s fundamental functional unit, is composed of a central vein, hepatic plates (cords of hepatocytes), and sinusoids that facilitate the exchange of nutrients and waste products between hepatocytes and the bloodstream3 (Fig. 1). Hepatic sinusoids contain sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells (liver-resident macrophages), and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), each of which plays a unique role in liver physiology and pathology. Hepatocytes, the primary parenchymal cells of the liver, perform essential metabolic functions such as glucose and lipid metabolism, detoxification of harmful substances, and bile production1,3. Other cell types, including cholangiocytes (bile duct cells), Kupffer cells, and HSCs, play essential roles in immune responses, fibrogenesis, and tissue repair. This cellular diversity and structural complexity enable the liver to perform its multifaceted functions, but also render it susceptible to injury and disease.

Structure of the hepatic lobule (created in BioRender, Tang, X. (2025) https://BioRender.com/mu7629l and BioGDP.com121).

PARPs are a family of enzymes that modulate diverse cellular processes through poly-ADP-ribosylation (PARylation). The PARP family comprises 17 members (PARP1-PARP16, including TNKS and TNKS2), each possessing distinct structural domains and functional roles in cellular physiology4. PARPs participate in critical pathways, such as DNA repair, regulation of gene expression, inflammation, metabolism, and cell death, thereby serving as essential regulators of cellular homeostasis and stress responses4. In recent years, the involvement of PARPs in liver disease has attracted growing interest. Multiple PARP family members have been implicated in the pathogenesis of viral hepatitis, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC, underscoring their potential as therapeutic targets5,6,7. These findings indicate that targeting PARPs may offer novel strategies for treating liver diseases. This review comprehensively summarizes the molecular and biological functions of PARPs in the liver, examines their roles in various liver pathologies, and explores their potential utility as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for hepatic disorders. By elucidating the mechanisms through which PARPs contribute to liver disease pathogenesis (Fig. 2), this review aims to provide new insights for the development of targeted therapies and improve clinical outcomes for patients with liver disorders.

An overview of the PARP-mediated liver diseases (created with biogdp.com121).

Domains and functions of PARPs

The PARP family comprises 17 members, each characterized by distinct structural domains that dictate their biological functions. The key domains and functions of the PARP family members are summarized in Table 1.

PARP1

PARP1 is the most extensively studied member of the PARP family. It possesses multiple functional domains, including three zinc finger domains (ZnF1, ZnF2, ZnF3), a BRCT domain, a WGR domain, an α-helical domain, and a catalytic domain. These domains mediate the recognition of DNA damage, such as single-strand breaks (SSBs), and catalyze ADP-ribosylation reactions, thereby facilitating the recruitment of DNA repair proteins (e.g., XRCC1 and DNA polymerase β) to damage sites. PARP1 plays a central role in base excision repair (BER) and the maintenance of genomic stability, and its dysregulation has been implicated in various diseases, including cancer, inflammatory disorders, and liver diseases8,9. Additionally, PARP1 influences mitochondrial metabolism through modulation of SIRT1 activity and contributes to telomere maintenance via PARylation of TRF1 and recruitment of helicases10. PARP1 is also involved in regulating apoptosis, inflammatory responses, and energy metabolism8, highlighting its multifunctional nature in cellular homeostasis.

PARP2

PARP2 shares significant structural homology with PARP1, possessing a WGR domain, a PARP alpha-helical domain, and a catalytic domain. It functions synergistically with PARP1 in DNA repair mechanisms, particularly in SSB repair8. Additionally, PARP2 helps maintain telomere integrity under replication stress by promoting break-induced replication (BIR)-mediated telomere repair11, underscoring its essential role in preserving genomic stability under genotoxic conditions.

PARP3

PARP3 is characterized structurally by a WGR domain, an α-helical domain, and a catalytic domain. It plays a critical role in DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair pathways. PARP3 detects DNA damage and promotes repair through ADP-ribosylation of histone H2B within nucleosomes12. Beyond DNA repair, PARP3 is involved in cellular signaling processes, including modulation of the Rictor/mTORC2 pathway, which contributes to metabolic regulation13.

PARP4

PARP4 contains multiple domains, including BRCT, PARP α-helical, catalytic, VIT, and VWFA domains. It contributes to DSB repair by facilitating non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) through mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation of Ku8014. It also regulates RNA splicing via interactions with hnRNPM15 and is implicated in the assembly and function of vault particles16,17, reflecting its diverse roles in cellular maintenance and RNA processing.

PARP5A and PARP5B

PARP5A and PARP5B (also known as Tankyrase-1 and Tankyrase-2) constitute a subfamily of PARPs, both containing multiple SAM domains and a C-terminal PARP catalytic domain. These enzymes play essential roles in telomere maintenance and the regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. By promoting the degradation of Axin, Tankyrases facilitate Wnt/β-catenin signaling, thereby influencing processes, such as cell proliferation and differentiation18, underscoring their significance in development and disease.

PARP6

PARP6 contains a PARP catalytic domain and is involved in regulating microtubule stability, centrosome integrity, and cell cycle progression. It functions as a negative regulator of cell proliferation in certain contexts19,20. Inhibition of PARP6 has been shown to induce multipolar spindle formation19,20,21, indicating its importance in ensuring accurate chromosome segregation during mitosis.

PARP7

PARP7 features a WWE domain, a PARP catalytic domain, and a C3H1-type zinc finger domain. It modulates immune and inflammatory responses primarily through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling pathway22. PARP7 activity contributes to the regulation of immune cell function and inflammatory processes, suggesting a role in linking environmental signals to immune homeostasis23.

PARP8

PARP8 contains a PARP catalytic domain, and current evidence has implicated it in the regulation of cell proliferation. However, its precise molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood24, highlighting a critical direction for future investigation.

PARP9

PARP9 (also referred to as BAL1) possesses Macro 1, Macro 2, and PARP catalytic domains. It plays important roles in immune regulation and DNA damage response. PARP9 enhances interferon signaling by facilitating the degradation of host histone H2BJ and viral proteins through its association with the DTX3L ubiquitin ligase complex25. Additionally, it is involved in cellular stress responses, including apoptosis and inflammation26, and participates directly in DNA repair pathways27.

PARP10

PARP10 is characterized by a PARP catalytic domain. It promotes RAD18-mediated translesion synthesis to address gaps in nascent DNA strands and mitigates replication stress during cell proliferation28,29,30, underscoring its contribution to DNA damage tolerance and genome maintenance.

PARP11

PARP11 contains a WWE domain, a PARP catalytic domain, and a C3H1-type domain. It contributes to immune regulation and nuclear envelope integrity. PARP11 also regulates DRP1-dependent mitophagy, suggesting a function in quality control and organelle homeostasis31,32.

PARP12

PARP12 features two WWE domains, a PARP catalytic domain, and multiple C3H1-type domains. It serves a key role in antiviral defense by inhibiting viral replication through the degradation of viral proteins such as NS1 and NS333. Furthermore, PARP12 is involved in mitophagy, maintenance of cell polarity and cell–cell junctions, and regulation of epithelial–mesenchymal transition34,35,36, reflecting its multifunctional nature in cellular physiology.

PARP13

PARP13 exists in two major isoforms, ZAP-L and ZAP-S, and contains a WWE domain, a PARP catalytic domain, and multiple C3H1-type domains. It serves as a critical mediator of antiviral immunity by specifically binding viral RNA and inhibiting viral replication37. It also regulates apoptosis by modulating the stability of TRAILR4 transcripts38 and influences stress granule maturation through interactions with poly(ADP-ribose)39, demonstrating its role in cellular stress responses.

PARP14

PARP14 is characterized by the presence of three macrodomains, a WWE domain, and a PARP catalytic domain. It plays pivotal roles in immune regulation, genomic stability, mitophagy, cell motility, and energy metabolism. Equipped with both ADP-ribosyltransferase and hydrolase activities, PARP14 participates in diverse cellular signaling pathways40,41,42,43,44, establishing it as a key modulator of cellular homeostasis.

PARP15

PARP15 contains Macro 1, Macro 2, and a PARP catalytic domain. It is primarily implicated in the maintenance of cellular barrier function, and its dysregulation has been closely linked to Clarkson disease (monoclonal gammopathy-associated systemic capillary leak syndrome)45, highlighting its critical role in vascular integrity.

PARP16

PARP16 features an α-helical domain and a PARP catalytic domain. It is essential for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress responses, cellular senescence, and apoptosis. PARP16 regulates the unfolded protein response (UPR) and influences senescence-associated pathways, thereby contributing to cell fate decisions46,47. Inhibition of PARP16 has been shown to exacerbate ER stress-induced cellular responses48, suggesting its importance in cellular stress adaptation.

PARPs in liver diseases

PARPs and viral hepatitis

PARPs in HBV

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major global public health issue, affecting hundreds of millions of individuals worldwide. HBV is a hepatotropic virus transmitted primarily through contact with infected blood or bodily fluids. It specifically targets hepatocytes, the principal functional cells of the liver, and establishes persistent chronic infections by evading host immune defenses49. Chronic HBV infection is a major risk factor for severe liver diseases, including liver cirrhosis, HCC, and other life-threatening complications50. The persistence of HBV in hepatocytes is partially facilitated by its capacity to integrate into the host genome, which can induce genomic instability and promote carcinogenesis. Studies have demonstrated that inhibition of PARP1 activity increases the frequency of HBV DNA integration, suggesting that PARP1 plays a crucial role in restraining HBV-induced genomic damage51.

Among the PARP family members, PARP13 serves a pivotal role in antiviral defense. As an Interferon-stimulated gene (ISG), PARP13 inhibits viral replication by specifically binding to and degrading viral RNA. In HBV-infected patients, PARP13 is upregulated in the liver during immune activation51. During this process, it directly binds to HBV pregenomic RNA (pgRNA) via its N-terminal zinc finger domain, thereby promoting RNA degradation and suppressing viral replication. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting PARP13 in the management of HBV infection.

PARPs in HCV

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major cause of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis worldwide. HCV is a bloodborne pathogen that primarily infects hepatocytes, leading to persistent liver inflammation, fibrosis, and in some cases, HCC52. The innate immune system constitutes the first line of defense against viral infections, and its ability to control viral replication is essential for preventing the establishment of chronic HCV infection. Nevertheless, HCV has evolved sophisticated mechanisms to evade host immune responses. These include genomic modifications that enable the virus to escape detection by antiviral proteins.

In RNA viruses, significant depletion of CpG dinucleotides (CpG suppression) is recognized as an evolutionary strategy to avoid host innate immune recognition. Over time, the HCV genome has lost many CpG islands53. This phenomenon is proposed to result from the virus’s selective evasion of PARP13 binding, which in turn helps it circumvent ZAP-mediated antiviral restriction53. However, CpG motifs within the HCV core gene remain relatively abundant, suggesting that their retention may not be attributable solely to PARP13-mediated selective pressure. This observation further implies that HCV may employ additional mechanisms to counteract PARP13’s antiviral activity, highlighting the complex interplay between host antiviral defenses and viral evasion strategies.

PARPs and MASLD/MASH

PARPs in MASLD

MASLD, formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), has emerged as a predominant cause of chronic liver disease worldwide. This rise is fueled by the increasing prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome. MASLD is characterized by excessive hepatic lipid accumulation, which can advance to inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis if unmanaged. The pathogenesis of MASLD involves a complex interplay of factors, including insulin resistance, dysregulated lipid metabolism, and genetic predisposition4,54. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD⁺) exerts protective and therapeutic effects against MASLD by suppressing hepatic lipid accumulation, mitigating liver fibrosis, and modulating the expression of lipogenic genes6. However, under pathological conditions, hyperactivation of PARP1—a major NAD⁺-consuming enzyme—depletes cellular NAD⁺ pools. This depletion, in turn, disrupts NAD⁺-dependent metabolic regulation in the liver, ultimately exacerbating lipid accumulation and fibrotic progression6.

Clinical data from normal human liver samples indicate that PARP1 transcripts are negatively correlated with nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) and nicotinamide riboside kinase 1 (NRK1)55. These two enzymes are key regulators of NAD⁺ biosynthesis. This suggests that PARP1 overactivation disrupts NAD⁺ homeostasis, contributing to the metabolic dysregulation observed in MASLD. In animal models of MASLD induced by a high-fat high-sucrose (HFHS) diet, PARP-mediated PARylation was found to increase, correlating with reduced NAD⁺ levels, decreased mitochondrial function, and elevated hepatic lipid content6. Olaparib predominantly inhibits PARP1 and PARP2, with weaker activity on PARP3, but does not significantly affect other family members56,57. Treatment with the PARP inhibitor olaparib significantly restored NAD⁺ levels, enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis and β-oxidation, and reversed MASLD progression by reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress6.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) is another key player in MASLD. It reduces hepatic lipid accumulation by enhancing fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in hepatocytes, and PPARα agonists have shown promising results in clinical trials for both MASLD and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatosis. Moreover, PARP1 acts as a transcriptional repressor of PPARα in human hepatocytes, suppressing hepatitis58,59,60. Studies have demonstrated that PARP1 mediates the PARylation of PPARα61. This modification inhibits the binding of PPARα to target gene promoters and attenuates its interaction with SIRT1, which is a key regulator of PPARα signaling61 ligand-induced PPARα activation and the expression of its target genes61. These findings indicate that PARP1 inhibition enhances PPARα activity and improves lipid metabolism in MASLD.

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a critical inflammatory mediator, has also been implicated in MASLD. HMGB1 exacerbates inflammation and promotes the progression of various liver diseases62. Recent studies have shown that PARP1 knockdown in HepG2 cells significantly reduces the expression of HMGB1 mRNA levels, underscoring the role of PARP1 in regulating inflammation63. This suggests that targeting PARP1 may alleviate inflammation and slow the progression of MASLD.

PARP2, a close homolog of PARP1, also contributes to the development of MASLD. Studies have revealed that PARP2 knockout mice exhibit significantly lower liver weight compared to wild-type mice when fed a high-fat diet (HFD)54. Furthermore, research in HepG2 cells and mice has demonstrated that PARP2 suppresses the promoter activity of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1). Specifically, PARP2 knockdown was found to enhance SREBP-1 expression, leading to increased hepatic cholesterol content, thereby highlighting the role of PARP2 in maintaining hepatic lipid homeostasis64.

PARPs in MASH

MASLD can progress to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), a severe form of liver disease characterized by persistent oxidative stress, inflammation, and hepatocyte injury. If left untreated, MASH may lead to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even HCC. Oxidative stress represents a core mechanism in the pathogenesis of MASH, driving excessive ROS production, triggering inflammatory responses, and inducing hepatocyte damage65.

In liver tissues from MASH patients, PARP1 transcripts were significantly increased and strongly correlated with fibrotic genes6. By contrast, antioxidant genes were negatively correlated with both PARP1 transcripts and fibrotic genes. These observations suggest that PARP1 activation contributes to oxidative stress and fibrosis in MASH. In animal models of MASH induced by a methionine and choline-deficient (MCD) diet, treatment with the PARP inhibitor olaparib significantly attenuates liver injury, disorders of fatty acid metabolism, steatosis, and hepatic inflammation66. These findings highlight the potential of PARP inhibitors as therapeutic agents for treating MASH.

PARPs and ALD

ALD represents a significant and growing global health burden67. Its progression is closely linked to the toxicity of alcohol metabolites. ALD encompasses a spectrum of hepatic disorders, ranging from simple steatosis to alcoholic hepatitis (AH) and cirrhosis. The pathogenesis of ALD is primarily driven by the direct toxic effects of alcohol and its metabolites, such as acetaldehyde, on the liver. These effects include hepatocyte death, steatosis, and activation of Kupffer cells, which release pro-inflammatory cytokines and exacerbate liver injury67.

The PARP inhibitor PJ34 predominantly targets PARP1 and PARP268,69. In chronic ethanol-fed ALD mice, PJ34 has been reported to attenuate hepatic steatosis and apoptosis, primarily by inhibiting Kupffer cell activation, thereby ameliorating liver injury and lipid accumulation70. Although simple steatosis may be reversible upon alcohol abstinence, approximately 35% of heavy drinkers progress to more severe alcoholic hepatitis. AH is characterized by prominent inflammatory infiltration and hepatocyte ballooning, involving excessive production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), lipid peroxidation, and oxidative DNA damage, ultimately leading to hepatocyte injury and death67,68,71,72. Clinical data have shown elevated PARP transcript levels in patients with AH6. In dietary models of alcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatic PARP activity is increased, while NAD⁺ levels and SIRT1 activity are decreased, accompanied by enhanced oxidative/nitrosative stress and cell death (including both necrosis and apoptosis). 5-Aminoisoquinoline (5-AIQ), an active PARP1 inhibitor that also serves as a key functional group in various pharmaceuticals73, along with other PARP inhibitors such as PJ34 or genetic deletion of PARP1, has been shown to significantly reduce alcohol-induced hepatocyte death, oxidative/nitrosative stress, steatosis, and metabolic dysregulation in the liver66. These findings indicate that PARP inhibition represents a promising therapeutic strategy for ALD71,72.

PARPs and liver fibrosis/cirrhosis

Liver fibrosis represents a critical pathological stage in the progression of chronic liver disease74. It is characterized by excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), along with hepatocyte injury, distortion of hepatic lobules, and alterations in vascular structure. Fibrosis results from persistent liver injury and inflammation75. These stimuli activate HSCs and promote their transdifferentiation into myofibroblasts, which in turn secrete large quantities of collagen and other ECM components. Various etiologies, including alcohol consumption, viral hepatitis, and MASLD, can trigger fibrosis by inducing hepatocyte injury, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses.

PARP1 plays a significant role in the development of liver fibrosis. In carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄)-induced liver fibrosis models, either PARP1 knockout or treatment with PARP1 inhibitors (e.g., PJ34 and AIQ) significantly reduced hepatocyte death, inflammation, and fibrotic changes. Similarly, PARP inhibitors demonstrated antifibrotic effects in bile duct ligation (BDL)-induced fibrosis models76. In HFHS diet-induced MASLD models, PJ34 alleviated MASLD-associated fibrosis77, while in MCD diet-induced models, the PARP inhibitor olaparib exhibited comparable antifibrotic effects6. These findings suggest that inhibition of PARP1 represents a promising therapeutic strategy for liver fibrosis.

Without timely intervention, liver fibrosis can progress to cirrhosis and eventually to HCC78. Analysis of liver tissues from patients with cirrhosis induced by alcohol or viral hepatitis showed significantly elevated PARP activity compared to controls. This indicates that PARP activation directly contributes to the progression of cirrhosis, and targeting PARP may help slow disease progression66,71,72.

PARPs and HCC

PARPs in HCC

HCC accounts for approximately 80% of all primary liver malignancies and represents the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide79,80. Although surgical resection and liver transplantation remain the only potentially curative treatments, the majority of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages and are no longer candidates for radical surgery81. Multi-kinase inhibitors such as sorafenib and lenvatinib offer additional therapeutic options for advanced HCC82,83. However, they only extend median overall survival by 2-3 months. Hepatocarcinogenesis is a multistep, multigenic process involving the accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations. These alterations, in turn, lead to the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes and activation of oncogenes, ultimately resulting in dysregulated cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and metastasis79,80,81.

PARP1 is frequently overexpressed in patients with HCC and is closely associated with poor prognosis84,85,86. In cell line-derived xenograft (CDX) models, reactivation of PARP1 was observed in residual HCC tumors following sorafenib treatment, suggesting its involvement in cancer stem cell pluripotency and sorafenib resistance85. HCC recurrence after liver transplantation remains a major clinical challenge87. Notably, liver ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury upregulates PARP1 expression, which in turn enhances susceptibility to HCC recurrence by modulating neutrophil recruitment and phenotypic switching. DPQ, a selective PARP1 inhibitor88,89, has been shown to significantly reduce tumor volume in xenograft models of HCC90. PJ34 significantly suppresses HepG2 cell growth in a dose-dependent manner and inhibits HepG2 cell-derived tumor growth in nude mice91. PARP1 attenuates the PARylation of Sp1. This reduction increases the expression of Sp1 target genes and induces G0/G1 phase arrest, ultimately inhibiting HCC cell proliferation. Other studies have shown that suppression of WIP1 synergizes with PARP inhibition to enhance DNA damage in HCC cells92.

PARP2 is highly expressed in HCC tissues, and its expression level is negatively correlated with patient survival86. In xenograft models of HCC, shRNA-mediated knockdown of PARP2 inhibited tumor growth93,94.

PARP4 mutations are found in over 10% of clinical HBV-related HCC patients, as shown by whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data from the European Genome-Phenome Archive94.

PARP5 is highly expressed in HCC95. In HCC cells, it enhances β-catenin activity by promoting the degradation of AXIN (axis inhibition proteins), thereby facilitating tumor proliferation. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a key role in HCC pathogenesis by regulating tumor cell proliferation, metabolism, invasion, and immune evasion. XAV939 was identified as the first highly potent inhibitor of PARP5, demonstrating 10- to 500-fold selectivity for tankyrases over PARP1 and PARP296,97. A nitro-substituted derivative of XAV939, WXL-8, also acts as an effective inhibitor of PARP595. Both TNKS/2 knockdown and treatment with tankyrase inhibitors (e.g., XAV939 and WXL-8) inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling, stabilize AXIN1/2, reduce β-catenin levels, and suppress HCC cell proliferation, colony formation, metastasis, and EMT97,98.

PARP6 is expressed at low levels in HCC cells and shows a negative correlation with the degree of tumor differentiation99. Silencing of PARP6 enhanced HCC cell proliferation, invasion, and migration, whereas its overexpression suppressed these malignant phenotypes. Mechanistically, PARP6 inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling by facilitating HDM2-mediated degradation of XRCC6, thereby suppressing HCC progression. These findings suggest that PARP6 could serve as a potential biomarker for HCC prognosis and monitoring99.

PARP10 is significantly downregulated in intrahepatic metastatic HCC tissues compared to primary HCC lesions and adjacent non-tumor tissues100. Studies have demonstrated that PARP10 inhibits Aurora A kinase activity through mono-ADP-ribosylation, thereby regulating downstream signaling pathways and suppressing tumor metastasis100. Additionally, PARP10 is involved in the PLK1/PARP10/NF-κB signaling axis. PLK1-mediated phosphorylation of PARP10 at threonine 601 weakens its interaction with NEMO101. This weakening leads to enhanced NF-κB transcriptional activity, which in turn promotes HCC development. Conversely, NF-κB activation suppresses PARP10 promoter activity, forming a negative feedback loop that further reduces PARP10 expression.

PARP12 exerts tumor-suppressive effects on HCC metastasis by regulating FHL2 stability and TGF-β1 expression36.

PARP14 is highly expressed in primary HCC tumors and is associated with poor prognosis. It inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) and promotes pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) phosphorylation, thereby regulating the Warburg effect and linking apoptosis and metabolism. Targeting PARP14 directly enhances HCC cell sensitivity to anticancer drugs102.

PARP inhibitors in HCC

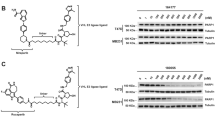

PARP inhibitors have achieved significant success in cancer therapy, particularly in cancers with defects in homologous recombination repair (HRR), such as BRCA-mutated breast and ovarian cancers. However, their efficacy in HCC remains limited, restricting their broader clinical application103,104. Recent studies have explored various strategies to enhance the sensitivity of HCC cells to PARP inhibitors (Fig. 3), offering new directions for targeted therapy of this challenging malignancy.

The combination therapy strategy of PARP Inhibitors in HCC (created with biogdp.com121).

One promising approach involves the use of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models to evaluate HCC responses to PARP inhibition. Studies have demonstrated that the PARP inhibitor olaparib can suppress tumor growth in these models. Notably, deficiency in NRDE2, a newly identified HCC susceptibility gene, significantly enhanced the sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma to PARP inhibitors105. This finding suggests that NRDE2 status may serve as a predictive biomarker for PARP inhibitor efficacy in HCC105.

Another key factor in DNA damage repair is histone H4K20 trimethyltransferase (KMT5C), which plays a crucial role in the maintenance of genomic stability. Inhibition of KMT5C, whether through pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., A196) or genetic knockout, increases the sensitivity of HCC cells to olaparib106. Given KMT5C’s role in maintaining genomic stability, this suggests that targeting KMT5C could be a viable strategy to overcome PARP inhibitor resistance in HCC106.

The spliceosome component SmD2 has also been implicated in the regulation of DNA damage responses in HCC. SmD2 affects the splicing of key DNA repair genes such as BRCA1 and FANC, and its deficiency sensitizes HCC cells to PARP inhibitors. This highlights the potential of targeting spliceosome components to enhance PARP inhibitor efficacy in HCC107.

Wild-type p53-induced protein phosphatase 1 (WIP1), a member of the PP2C family, plays a critical role in DNA damage response. WIP1 knockdown in HCC cells increases sensitivity to PARP inhibitors, and the combination of the WIP1 inhibitor GSK2830371 and PARP inhibitors has been shown to significantly delay tumor growth in HCC cell-derived xenograft models. This suggests that WIP1 inhibition could be a promising strategy to enhance PARP inhibitor efficacy in HCC92.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (MET) pathways have also been implicated in PARP inhibitor resistance. Rucaparib (AG014699) is a potent small-molecule inhibitor of PARP proteins, including PARP1, PARP2 and PARP3108. Inhibition of both EGFR and MET sensitizes HCC cells to the PARP inhibitor AG01469104. The underlying mechanism involves the interaction between EGFR–MET heterodimers and nuclear PARP1 at tyrosine 907 (Y907): this interaction induces PARP1 phosphorylation, which may otherwise promote resistance to PARP inhibition104.

In BRCA1-low HCC cells, the combination of olaparib with androgen receptor (AR) inhibitors (e.g., enzalutamide) or AR-shRNA synergistically suppresses tumor growth109. This synergistic effect is likely mediated by the downregulation of BRCA1 and other DNA damage response (DDR) genes, suggesting that AR inhibition could enhance the efficacy of PARP inhibitors in HCC109.

Additionally, niraparib, a selective inhibitor of PARP1 and PARP2, has been shown to induce cytotoxicity in HCC cells, accompanied by increased autophagy110. The combination of niraparib with the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (CQ) synergistically enhanced cell death in HCC cell lines such as Huh7 and HepG2, indicating that autophagy inhibition may serve as a beneficial adjunct to PARP inhibitor therapy in HCC111.

Beyond conventional chemotherapy, studies have explored the combination of olaparib with radiotherapy in HCC. These studies demonstrate that olaparib enhances radiosensitivity by promoting DSBs and activating the cGAS-STING pathway, thereby triggering immunogenic cell death112. These findings suggest that PARP inhibitors could be utilized to improve the efficacy of radiotherapy in HCC.

In the context of HCC immunotherapy, the combination of olaparib with PD-1 antibodies has been demonstrated to enhance antitumor immunity. This combination regimen not only leads to superior tumor control but also promotes a robust antitumor immune response, representing a promising combinatorial strategy for incorporating PARP inhibitors into immunotherapeutic protocols for HCC113.

Collectively, these studies provide valuable mechanistic and translational insights to inform precision therapy for HCC. By targeting specific molecular pathways and integrating PARP inhibitors with other treatment modalities, it may be feasible to overcome the current limitations of PARP inhibitor monotherapy and ultimately improve clinical outcomes in HCC patients.

Research and prospect

In summary, the role of the PARP family in liver diseases has increasingly become a focus of research, with substantial advances made in understanding its implications in viral hepatitis, MASLD, ALD, and HCC. PARP family members contribute to the pathogenesis, progression, and treatment response of liver diseases through the regulation of diverse biological processes—such as DNA repair, cellular metabolism, inflammatory responses, and immune modulation, thereby highlighting their broad biological functions and therapeutic potential.

Research findings

Viral hepatitis

To date, research primarily focuses on PARP13, which exerts antiviral functions through the recognition, binding, and degradation of viral RNA. However, other PARP family members, such as PARP12, PARP7, and PARP14, also contain RNA-binding domains and are likely to play important roles in viral hepatitis. For instance, studies have demonstrated that PARP12 exhibits antiviral activity during Zika virus infection by mediating the ADP-ribosylation of the viral NS3 protein, thereby promoting its proteasomal degradation33,34. The NS3 protein is critical for HCV replication, assembly, and immune evasion33,34,114. Given this, the specific mechanisms through which PARP12 acts in HCV infection, particularly its potential interaction with the NS3 protein, warrant further investigation.

MASLD/MASH

Although multiple PARP transcripts are significantly upregulated in the liver tissues of patients with MASLD/MASH, current research has predominantly focused on PARP1, with mechanistic studies largely centered on hepatocytes. However, non-parenchymal liver cells, such as Kupffer cells, also play a crucial role in the progression of MASLD/MASH. For instance, the M1/M2 polarization of Kupffer cells is closely associated with MASH progression114,115. Moreover, PARP9 and PARP14 have been shown to cross-regulate macrophage activation25,26,42,116, suggesting that their potential roles in the development of MASH deserve further investigation.

ALD/AH

Existing research has predominantly focused on PARP1. However, other PARP family members, including PARP2, PARP7, PARP9, and PARP14, are increasingly recognized to participate in the progression of disease through diverse mechanisms, such as DNA repair, inflammation regulation, metabolic modulation, and stress response. For instance, PARP7 acts as a negative regulator of the AhR signaling pathway, suggesting it may mediate alcohol-induced liver injury22,23,116,117. This hypothesis is supported by studies indicating that AhR agonists can ameliorate alcohol-induced liver damage through activation of the AhR pathway. However, the specific mechanisms through which PARP7 regulates alcohol-induced liver injury in this context remain to be elucidated.

Liver fibrosis/cirrhosis

Research on liver fibrosis and cirrhosis remains predominantly focused on PARP176,77,78. Additionally, most of these studies are conducted in animal models, with relatively few investigating the role of PARP1 (or other PARP members) at the cellular level. The sustained activation of HSCs represents a pivotal driver of liver fibrosis. Given the multifaceted roles of PARP family members in processes such as DNA repair, inflammation regulation, and metabolic modulation, they may directly or indirectly influence HSC activation and the progression of fibrotic processes77,78.

HCC

Multiple PARP family members contribute to tumor progression by modulating DNA repair and signaling pathways, such as Wnt/β-catenin. PARP1 and PARP2 play critical roles in DNA damage repair. In hepatitis and hepatitis-induced HCC, the accumulation of DNA damage may lead to overactivation of PARP1. Future studies should further investigate the involvement of PARP1 in hepatocyte DNA repair and its dual role in HCC pathogenesis. Additionally, PARP inhibitors have demonstrated promising efficacy in combination therapies. However, a deeper understanding of the specific mechanisms of individual PARP proteins in HCC is essential to develop highly selective targeted inhibitors or activators, thereby providing more precise treatment strategies for patients111,112,113.

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and AILD

Currently, no studies have reported on the roles of PARP proteins in drug-induced liver injury or AILD. Drugs such as acetaminophen (APAP) can induce the production of ROS, leading to DNA damage118,119, which may subsequently activate PARP1 and facilitate DNA repair. However, overactivation of PARP1 may result in depletion of NAD⁺ and ATP, ultimately causing cellular energy exhaustion. Thus, PARP1 may exert a dual role in the context of DILI. In AILD, the pathogenesis centers on aberrant immune attacks targeting hepatic tissue, driven by a combination of genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, immune dysregulation, and molecular mimicry. Given that PARP7 and other PARP family members are known to regulate immune responses, their potential roles in AILD warrants further investigation120.

Research methods

Whole-gene knockout, cell line knockdown, and inhibitors are commonly used to investigate the relationship between PARP proteins and liver diseases. However, these approaches have limitations that may affect the accuracy and practical applicability of research findings. First, while whole-gene knockout can completely eliminate the function of a specific PARP protein, it may trigger developmental compensation effects. Specifically, other PARP family members may be compensatorily expressed, which in turn masks the true function of the target protein. Additionally, whole-gene knockout lacks tissue specificity, making it impossible to distinguish the specific functions of PARP proteins in different liver cell types (e.g., hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and HSCs), limiting our understanding of their cell-specific mechanisms in liver diseases. Second, cell line knockdown techniques (e.g., RNA interference) can partially simulate the loss of PARP protein function. However, cell lines fail to fully replicate the complex in vivo microenvironment and intercellular interactions, which may lead to discrepancies between experimental findings and actual physiological conditions. Moreover, RNA interference may have off-target effects, compromising the reliability of experimental results. Finally, inhibitors offer the advantage of rapidly and reversibly inhibiting PARP protein activity. Nevertheless, many PARP inhibitors lack sufficient specificity. They target multiple PARP family members, making it difficult to clarify the function of a single PARP protein. Further, differences between in vitro experiments and in vivo drug metabolism may limit the reproducibility and clinical translatability of experimental results.

To overcome these limitations, future research can adopt the following strategies: First, develop tissue-specific knockout models, such as using the Cre-loxP system to construct hepatocyte-, Kupffer cell-, or hepatic stellate cell-specific knockout models, enabling more precise investigation of PARP protein functions in specific cell types. Second, multi-omics technologies (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) are used to comprehensively analyze the regulatory networks of PARP proteins in liver diseases, revealing their multifaceted roles in DNA repair, inflammatory responses, and metabolic regulation. Furthermore, highly selective PARP inhibitors targeting specific PARP family members should be designed, with their efficacy and safety validated in preclinical and clinical studies. Finally, liver organoids or 3D culture models should be utilized to simulate the in vivo microenvironment, better reflecting the physiological functions of PARP proteins in liver diseases and enhancing the physiological relevance of the experimental results.

Conclusion

In summary, the PARP protein family plays a critical role in liver diseases. Specifically, it is closely linked to the pathogenesis and progression of multiple hepatic disorders, including hepatitis, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC. Although considerable progress has been made in understanding the contributions of PARP family members in hepatic pathologies, their precise mechanisms of action remain to be fully elucidated. Future research should focus on clarifying the molecular mechanisms through which PARPs influence liver diseases, developing targeted therapeutic strategies such as PARP inhibitors or activators, and assessing their potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Additionally, further attention should be directed toward the context-dependent roles of PARPs, which can be either protective or pathogenic, by integrating preclinical and clinical studies. Such efforts will help advance the development of personalized treatment strategies and offer novel therapeutic targets and approaches for liver diseases.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Devarbhavi, H. et al. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 79, 516–537 (2023).

Taru, V. et al. Inflammasomes in chronic liver disease: hepatic injury, fibrosis progression and systemic inflammation. J. Hepatol. 81, 895–910 (2024).

Kietzmann, T. Metabolic zonation of the liver: the oxygen gradient revisited. Redox Biol. 11, 622–630 (2017).

Szántó, M. et al. PARPs in lipid metabolism and related diseases. Prog. Lipid Res. 84, 101117 (2021).

Paturel, A. et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition as a promising approach for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Cancers (Basel) 15, 3806 (2022).

Gariani, K. et al. Inhibiting poly ADP-ribosylation increases fatty acid oxidation and protects against fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 66, 132–141 (2017).

Gerossier, L. et al. PARP inhibitors and radiation potentiate liver cell death in vitro. Do hepatocellular carcinomas have an Achilles’ heel?. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 45, 101553 (2021).

Gibson, B. A. & Kraus, W. L. New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly(ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 411–424 (2012).

Bai, P. & Virág, L. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases in the regulation of inflammatory processes. FEBS Lett. 586, 3771–3777 (2012).

Maresca, C. et al. PARP1 allows proper telomere replication through TRF1 poly (ADP-ribosyl)ation and helicase recruitment. Commun. Biol. 6, 234 (2023).

Muoio, D. et al. PARP2 promotes break induced replication-mediated telomere fragility in response to replication stress. Nat. Commun. 15, 2857 (2024).

Grundy, G. J. et al. PARP3 is a sensor of nicked nucleosomes and monoribosylates histone H2B(Glu2). Nat. Commun. 7, 12404 (2016).

Beck, C. et al. PARP3, a new therapeutic target to alter Rictor/mTORC2 signaling and tumor progression in BRCA1-associated cancers. Cell Death Differ. 9, 1615–1630 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. PARP4 deficiency enhances sensitivity to ATM inhibitor by impairing DNA damage repair in melanoma. Cell Death Discov. 11, 35 (2025).

Lee, Y. F. et al. PARP4 interacts with hnRNPM to regulate splicing during lung cancer progression. Genome Med. 16, 91 (2024).

Vyas, S. et al. Family-wide analysis of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity. Nat. Commun. 5, 4426 (2014).

Kickhoefer, V. A. et al. The 193-kD vault protein, VPARP, is a novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J. Cell Biol. 5, 917–945 (1999).

Riffell, J. L. et al. Tankyrase-targeted therapeutics: expanding opportunities in the PARP family. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 923–959 (2012).

Vermehren-Schmaedick, A. et al. Characterization of PARP6 function in knockout mice and patients with developmental delay. Cells 10, 1289 (2021).

Tuncel, H. et al. PARP6, a mono(ADP-ribosyl) transferase and a negative regulator of cell proliferation, is involved in colorectal cancer development. Int. J. Oncol. 41, 2079–2086 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of PARP6 triggers multipolar spindle formation and elicits therapeutic effects in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 78, 6691–6702 (2018).

Ahmed, S. et al. Loss of the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase, Tiparp, increases sensitivity to dioxin-induced steatohepatitis and lethality. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 16824–16864 (2015).

Gozgit, J. M. et al. PARP7 negatively regulates the type I interferon response in cancer cells and its inhibition triggers antitumor immunity. Cancer Cell 39, 1214–1226 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Identification and validation of immunogenic cell death-related score in uveal melanoma to improve prediction of prognosis and response to immunotherapy. Aging (Albany, NY) 15, 3442–3464 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. PARP9-DTX3L ubiquitin ligase targets host histone H2BJ and viral 3C protease to enhance interferon signaling and control viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 16, 1215–1242 (2015).

Liao, M. et al. PARP9 exacerbates apoptosis and neuroinflammation via the PI3K pathway in the thalamus and hippocampus and cognitive decline after cortical infarction. J. Neuroinflamm. 22, 43 (2025).

Yan, Q. et al. BAL1 and its partner E3 ligase, BBAP, link Poly(ADP-ribose) activation, ubiquitylation, and double-strand DNA repair independent of ATM, MDC1, and RNF8. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 845–900 (2013).

Schleicher, E. M. et al. Nicolae CM. PARP10 promotes cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis by alleviating replication stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 8908–8916 (2018).

Venkannagari, H. et al. Small-molecule chemical probe rescues cells from Mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase ARTD10/PARP10-induced apoptosis and sensitizes cancer cells to DNA damage. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 1251–1260 (2016).

Khatib, J. B. et al. PARP10 promotes the repair of nascent strand DNA gaps through RAD18 mediated translesion synthesis. Nat. Commun. 15, 6197 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Targeting PARP11 to avert immunosuppression and improve CAR T therapy in solid tumors. Nat. Cancer 3, 808–820 (2022).

Meyer-Ficca, M. L. et al. Spermatid head elongation with normal nuclear shaping requires ADP-ribosyltransferase PARP11 (ARTD11) in mice. Biol. Reprod. 92, 80 (2015).

Li, L. et al. PARP12 suppresses Zika virus infection through PARP-dependent degradation of NS1 and NS3 viral proteins. Sci. Signal. 11, eaas9332 (2018).

Deng, Z. et al. IRF1-mediated upregulation of PARP12 promotes cartilage degradation by inhibiting PINK1/Parkin dependent mitophagy through ISG15 attenuating ubiquitylation and SUMOylation of MFN1/2. Bone Res. 12, 63 (2024).

Grimaldi, G. et al. PKD-dependent PARP12-catalyzed mono-ADP-ribosylation of Golgin-97 is required for E-cadherin transport from Golgi to plasma membrane. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2026494119 (2022).

Shao, C. et al. PARP12 (ARTD12) suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through interacting with FHL2 and regulating its stability. Cell Death Dis. 9, 856 (2018).

Schwerk, J. et al. RNA-binding protein isoforms ZAP-S and ZAP-L have distinct antiviral and immune resolution functions. Nat. Immunol. 20, 1610–1620 (2019).

Todorova, T., Bock, F. J. & Chang, P. PARP13 regulates cellular mRNA post-transcriptionally and functions as a pro-apoptotic factor by destabilizing TRAILR4 transcript. Nat. Commun. 5, 5362 (2014).

Cheng, S. J. et al. Regulation of stress granule maturation and dynamics by poly(ADP-ribose) interaction with PARP13. Nat. Commun. 16, 621 (2025).

Đukić, N. et al. PARP14 is a PARP with both ADP-ribosyl transferase and hydrolase activities. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi2687 (2023).

Dhoonmoon, A., Nicolae, C. M. & Moldovan, G. L. The KU-PARP14 axis differentially regulates DNA resection at stalled replication forks by MRE11 and EXO1. Nat. Commun. 13, 5063 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Targeting PARP14 with lomitapide suppresses drug resistance through the activation of DRP1-induced mitophagy in multiple myeloma. Cancer Lett. 588, 216802 (2024).

Vyas, S. et al. A systematic analysis of the PARP protein family identifies new functions critical for cell physiology. Nat. Commun. 4, 2240 (2013).

Cho, S. H. et al. Glycolytic rate and lymphomagenesis depend on PARP14, an ADP ribosyltransferase of the B aggressive lymphoma (BAL) family. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15972–15979 (2011).

Chan, E. C. et al. PARP15 is a susceptibility locus for Clarkson disease (monoclonal gammopathy-associated systemic capillary leak syndrome). Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 44, 2628–2646 (2024).

Jwa, M. & Chang, P. PARP16 is a tail-anchored endoplasmic reticulum protein required for the PERK- and IRE1α-mediated unfolded protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1223–1253 (2012).

Yang, D. et al. Smyd3–PARP16 axis accelerates unfolded protein response and vascular aging. Aging (Albany, NY) 12, 21423–21445 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances ER stress-induced cancer cell apoptosis by directly targeting PARP16 activity. Cell Death Discov. 3, 17034 (2017).

Yuen, M. F. et al. Hepatitis B virus infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 4, 18035 (2018).

Liang, T. J. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology 49, S13–S21 (2009).

Dandri, M. et al. Increase in de novo HBV DNA integrations in response to oxidative DNA damage or inhibition of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Hepatology 35, 217–240 (2002).

Haga, Y. et al. Hepatitis C virus chronicity and oncogenic potential: Vaccine development progress. Mol. Aspects Med. 99, 101305 (2024).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Selective depletion of ZAP-binding CpG motifs in HCV evolution. Pathogens 12, 43 (2022).

Steinberg, G. R. et al. Integrative metabolism in MASLD and MASH: Pathophysiology and emerging mechanisms. J. Hepatol. 83, 584–595 (2025).

Gariani, K. et al. Eliciting the mitochondrial unfolded protein response by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide repletion reverses fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology 63, 1190–1394 (2016).

Murai, J. et al. Stereospecific PARP trapping by BMN 673 and comparison with olaparib and rucaparib. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13, 433–476 (2014).

Sharif-Askari, B. et al. PARP3 inhibitors ME0328 and olaparib potentiate vinorelbine sensitization in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 172, 23–32 (2018).

Pawlak, M., Lefebvre, P. & Staels, B. Molecular mechanism of PPARα action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 62, 720–753 (2015).

Fernández-Miranda, C. et al. A pilot trial of fenofibrate for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 40, 200–205 (2008).

Keating, G. M. Fenofibrate: a review of its lipid-modifying effects in dyslipidemia and its vascular effects in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 11, 227–274 (2011).

Huang, K. et al. PARP1-mediated PPARαpoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation suppresses fatty acid oxidation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 66, 962–977 (2017).

Personnaz, J. et al. Nuclear HMGB1 protects from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through negative regulation of liver X receptor. Sci. Adv. 8, eabg9055 (2022).

Ai, S. et al. OTUB1 mediates PARP1 deubiquitination to alleviate NAFLD by regulating HMGB1. Exp. Cell Res. 445, 114425 (2025).

Szántó, M. et al. Deletion of PARP-2 induces hepatic cholesterol accumulation and decrease in HDL levels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 594–602 (2014).

Chen, Z. et al. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 152, 116–141 (2020).

Mukhopadhyay, P. et al. PARP inhibition protects against alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 66, 589–600 (2017).

Mackowiak, B. et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease. J. Clin Invest. 134, e176345 (2024).

Zha, S. et al. PARP1 inhibitor (PJ34) improves the function of aging-induced endothelial progenitor cells by preserving intracellular NAD+ levels and increasing SIRT1 activity. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 9, 224 (2018).

Haddad, M. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of PJ34, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, in transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Br. J. Pharm. 149, 23–30 (2006).

Zhang, Y. et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 protects chronic alcoholic liver injury. Am. J. Pathol. 186, 3117–3130 (2016).

Nagy, L. E. et al. Linking pathogenic mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease with clinical phenotypes. Gastroenterology 150, 1756–1768 (2016).

Louvet, A. & Mathurin, P. Alcoholic liver disease: mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 231–242 (2015).

Vinod, K. R. et al. Evaluation of 5-aminoisoquinoline (5-AIQ), a novel PARP-1 inhibitor for genotoxicity potential in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 20, 90–95 (2010).

Friedman, S. L. Evolving challenges in hepatic fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 425–436 (2010).

Friedman, S. L. et al. Hepatic fibrosis 2022: unmet needs and a blueprint for the future. Hepatology 75, 473–488 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Puerarin protects against high-fat high-sucrose diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by modulating PARP-1/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and facilitating mitochondrial homeostasis. Phytother. Res. 33, 2347–2359 (2019).

Mukhopadhyay, P. et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 is a key mediator of liver inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology 59, 1998–2009 (2014).

Gong, L. et al. Hepatic fibrosis: targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha from mechanism to medicines. Hepatology 78, 1625–1653 (2023).

Islami, F. et al. Disparities in liver cancer occurrence in the United States by race/ethnicity and state. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 273–289 (2017).

Villanueva, A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1450–1462 (2019).

Schwartz, M. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2, 16018 (2016).

Bruix, J. et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389, 56–66 (2017).

Kudo, M. et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 391, 1163–1173 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Expression of cluster of differentiation-95 and relevant signaling molecules in liver cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 11, 3375–3381 (2015).

Yang, X. D. et al. PARP inhibitor Olaparib overcomes Sorafenib resistance through reshaping the pluripotent transcriptome in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 20, 20 (2021).

Lin, L. et al. The clinicopathological significance of miR-149 and PARP-2 in hepatocellular carcinoma and their roles in chemo/radiotherapy. Tumour Biol. 37, 12339–12346 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. PARP-1 promotes tumor recurrence after warm ischemic liver graft transplantation via neutrophil recruitment and polarization. Oncotarget 8, 88918–88933 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. PARP-1 inhibitor, DPQ, attenuates LPS-induced acute lung injury through inhibiting NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response. PLoS ONE 8, e79757 (2013).

Scalia, M. et al. PARP-1 inhibitors DPQ and PJ-34 negatively modulate proinflammatory commitment of human glioblastoma cells. Neurochem. Res. 38, 50–58 (2013).

Quiles-Perez, R. et al. Inhibition of poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase decreases hepatocellular carcinoma growth by modulation of tumor-related gene expression. Hepatology 51, 255–266 (2010).

Huang, S. H. et al. PJ34, an inhibitor of PARP-1, suppresses cell growth and enhances the suppressive effects of cisplatin in liver cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 20, 567–572 (2008).

Chen, M. et al. Co-targeting WIP1 and PARP induces synthetic lethality in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Commun. Signal. 20, 39 (2022).

Dai, L. et al. A novel prognostic model of hepatocellular carcinoma per two NAD+ metabolic synthesis-associated genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 10362 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Exome capture sequencing reveals new insights into hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma at the early stage of tumorigenesis. Oncol. Rep. 30, 1906–1912 (2013).

Ma, L. et al. Tankyrase inhibitors attenuate WNT/β-catenin signaling and inhibit growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget 6, 25390–25401 (2015).

Huang, S. M. et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature 461, 614–620 (2009).

Mashimo, M. et al. Tankyrase regulates neurite outgrowth through poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation-dependent activation of β-catenin signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2834 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Tankyrases/β-catenin signaling pathway as an anti-proliferation and anti-metastatic target in hepatocarcinoma cell lines. J. Cancer 11, 432–440 (2020).

Tang, B. et al. PARP6 suppresses the proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by degrading XRCC6 to regulate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Am. J. Cancer Res. 10, 2100–2113 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. PARP10 suppresses tumor metastasis through regulation of Aurora A activity. Oncogene 37, 2921–2935 (2018).

Tian, L. et al. PLK1/NF-κB feedforward circuit antagonizes the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of PARP10 and facilitates HCC progression. Oncogene 39, 3145–3162 (2020).

Iansante, V. et al. PARP14 promotes the Warburg effect in hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting JNK1-dependent PKM2 phosphorylation and activation. Nat. Commun. 6, 7882 (2015).

Gabrielson, A. et al. Phase II study of temozolomide and veliparib combination therapy for sorafenib-refractory advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharm. 76, 1073–1079 (2015).

Dong, Q. et al. EGFR and c-MET cooperate to enhance resistance to PARP inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 79, 819–829 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. NRDE2 deficiency impairs homologous recombination repair and sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to PARP inhibitors. Cell Genom. 4, 100550 (2024).

Tong, Y. et al. Histone methyltransferase KMT5C drives liver cancer progression and directs therapeutic response to PARP inhibitors. Hepatology 80, 38–54 (2024).

Sun, L. et al. Acetylation-dependent regulation of core spliceosome modulates hepatocellular carcinoma cassette exons and sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 15, 5209 (2024).

Colombo, I. et al. Rucaparib: a novel PARP inhibitor for BRCA advanced ovarian cancer. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 12, 605–617 (2018).

Zhao, J. et al. Olaparib and enzalutamide synergistically suppress HCC progression via the AR-mediated miR-146a-5p/BRCA1 signaling. FASEB J. 34, 5877–5891 (2020).

Mirza, M. R. et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 2154–2164 (2016).

Zai, W. et al. Targeting PARP and autophagy evoked synergistic lethality in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 41, 345–357 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Olaparib enhances radiation-induced systemic anti-tumor effects via activating STING-chemokine signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 582, 216507 (2024).

Sun, G. et al. Inhibition of PARP potentiates immune checkpoint therapy through miR-513/PD-L1 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Oncol. 2022, 6988923 (2022).

Han, Y. H. et al. RORα Induces KLF4-mediated M2 polarization in the liver macrophages that protect against nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Rep. 20, 124–135 (2017).

Iwata, H. et al. PARP9 and PARP14 cross-regulate macrophage activation via STAT1 ADP-ribosylation. Nat. Commun. 7, 12849 (2016).

Wrzosek, L. et al. Microbiota tryptophan metabolism induces aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation and improves alcohol-induced liver injury. Gut 70, 1299–1308 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. 3-Hydroxypropionaldehyde modulates tryptophan metabolism to activate AhR signaling and alleviate ethanol-induced liver injury. Phytomedicine 139, 156445 (2025).

Yan, M. et al. Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced liver injury and its implications for therapeutic interventions. Redox Biol. 17, 274–283 (2018).

Deng, X. et al. Paeoniflorin protects hepatocytes from APAP-induced damage through launching autophagy via the MAPK/mTOR signaling pathway. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 29, 119 (2024).

Jeltema, D. et al. PARP7 inhibits type I interferon signaling to prevent autoimmunity and lung disease. J. Exp. Med. 222, e20241184 (2025).

Jiang, S. et al. Generic Diagramming Platform (GDP): a comprehensive database of high-quality biomedical graphics. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, 1670–1676 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 82404728). The figures have been created using BioRender.com and BioGDP.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X. conceptualized this manuscript. J.X. and X.T. conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. X.T. designed the figures. Q.Z. and Y.X. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, J., Tang, X., Zhu, Q. et al. PARPs in liver diseases. npj Gut Liver 2, 33 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44355-025-00043-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44355-025-00043-x