Abstract

Plug-in electric vehicles (EVs) are reshaping the transportation energy landscape, providing a practical alternative to petroleum fuels for a growing number of applications. EV sales grew 55× in the past decade (2014–2024) and 6× since 2020, driven by technological progress enabled by policies to reduce transportation emissions as well as industrial plans motivated by strategic value of EVs for global competitiveness, jobs and geopolitics. In 2024, 22% of passenger cars sold globally were EVs and opportunities for EVs beyond on-road applications are growing, including solutions to electrify off-road vehicles, maritime and aviation. This Review updates and expands our 2020 assessment of the scientific literature and describes the current status and future projections of EV markets, charging infrastructures, vehicle–grid integration and supply chains in the USA. EV is the lowest-emission motorized on-road transportation option, with life-cycle emissions decreasing as electricity emissions continue to decrease. Charging infrastructure grew in line with EV adoption but providing ubiquitous reliable and convenient charging remains a challenge. EVs are reducing electricity costs in several US markets and coordinated EV charging can improve grid resilience and reduce electricity costs for all consumers. The current trajectory of technology improvement and industrial investments points to continued acceleration of EVs.

Key points

-

Plug-in electric vehicles (EVs) continue to set global sales records (capturing 22% of sales during 2024) and expand beyond passenger cars, but adoption varies considerably among regions and between different consumers and applications.

-

EVs are the lowest-emission option for passenger automobiles, with life-cycle emissions of criteria pollutants and greenhouse gases decreasing as electricity becomes cleaner. The remaining emissions are attributable largely to vehicle and component manufacturing.

-

Early adopters of EVs show very high satisfaction and indicate high likelihood of driving EVs in the future but access to and convenience of charging, policy uncertainty and concerns around supply chain for battery materials make other potential EV owners sceptical.

-

A wide range of policies have been implemented to support EV adoption and domestic manufacturing, citing goals related to greenhouse gas emissions, air quality, energy security and industrial competitiveness.

-

As charging infrastructure expands, challenges remain in providing convenient access for drivers without dedicated private charging (garage orphans) and in establishing reliable, interoperable fast-charging corridors for long-distance travel.

-

The current trajectory of technology improvements, policy support and industrial investments points to continued acceleration of EVs for on-road vehicles and growing global adoption of EVs for numerous non-road applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the past 10 years, plug-in electric vehicles (EVs) have grown from a niche technology to a mass-market option, accounting for 22% of passenger cars sold globally during 2024. About 1 in 10 new light-duty vehicles sold in the USA during 2024 was an EV1. EVs are also finding new applications beyond light-duty passenger cars to include commercial vehicles, with early market adoption of electric buses, vans and trucks, and growing interests in electrification of larger vehicles2,3,4,5. However, adoption rates continue to vary considerably within the USA and between different consumer demographics, with adoption concentrated in some areas and for specific commercial applications (Fig. 1).

Electric vehicle (EV) adoption trends show not only major growth in the USA during the 2021–2024 period but also substantial heterogeneity in EV adoption across the country, with some counties at almost 50% EV sales share in 2024 but large areas of the country with adoption below 5%. Data include light-duty battery electric and plug-in hybrid EVs. Data from refs. 300,301. LDV, light-duty vehicle. Data available in the Supplementary information.

Although EVs are not disrupting mobility per se (for example, a mobility paradigm shift would involve a shift away from driving and towards other travel modes such as bicycles or public transit), they are poised to transform fundamentally the transportation–energy nexus and the automotive industrial sector6,7. For the first time in more than a century, EVs are offering a viable supplement or alternative to petroleum, which today accounts for more than 90% of US transportation energy use (US Energy Information Administration total energy). In addition, EVs can reduce greatly pollutant emissions and have the potential to greatly reduce life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions by leveraging clean electricity8. The rapid uptake of EVs, driven by technology improvements — especially in batteries — and policy actions, has turned into a unique industrial opportunity with major geopolitical, employment-related and trade-related consequences that is attracting industry investments of more than US$750 billion per year9.

In this Review, we provide an overview of EV markets, technologies and future projections updating insights from a 2021 review10 (see Supplementary Table 1 for a comparison of how key messages from 2021 have evolved). Until the early 2020s, literature was largely focused on EV technologies and components as well as on electricity-system integration modelling and analysis. Given the rapid uptake in EVs, focus in the literature has shifted during the past few years with more studies on charging infrastructure scale-up, electricity-system integration of larger EV loads and considerations around EV-related manufacturing and supply chains. Moreover, the improvements of EVs for on-road applications and the progress in batteries and EV technologies have spurred interest in electrification of non-road, rail, maritime and aviation. We focus on US markets and applications but provide global context and comparisons with other regions of the world to contextualize insights and provide readers with useful comparison points.

Status and future of on-road EV markets

Several factors have enabled growing market share of EVs, including high levels of technology satisfaction from drivers, continued cost reductions and technical improvements in battery technologies, policy instruments that support EVs and charging infrastructure or address domestic EV and component manufacturing, private-sector commitments and investments (leading to increased EV manufacturing capacity and greater availability of EV makes and models as well as market pull for EV adoption), and regulations and standards that support energy efficiency and reduced emissions. Although early adopters of EVs show very high satisfaction and indicate high likelihood to purchase EVs in the future11,12,13,14,15, factors such as access to and convenience of charging, especially for ‘garage orphans’16, high policy uncertainty17, and concerns around sourcing and supply chain for battery and motor materials and components18 make other potential EV owners sceptical and hinder investments in EVs. Therefore, the future share of EVs in the US market will depend on the balance of many factors. This section discusses the status of US EV markets, technology and policy drivers of adoption, challenges to EV adoption and future projections, with examples from other regions for comparison.

Current EV adoption

EV sales continue to increase year over year and represented 22% of the global light-duty vehicles (LDVs) market with total sales of 17.5 million EVs during 2024, which was about six times the EV sales during 2020 (3 million), and an over 55-fold increase during a decade (2014–2024) compared with ~300,000 EVs being sold during 2014 (ref. 1). During 2024, 1.6 million EVs were sold in the USA, which represent about 10% of total sales of new LDVs and about five times the number of EVs sold in the USA during 2020 (refs. 1,19). Despite rapid growth, EV market share varies geographically and across consumer segments, remaining concentrated in some areas (Fig. 1). For instance, during 2024, EVs reached 43% sales share and 12% vehicle stock share in Santa Clara County20, CA, USA. These figures are aligned with adoption levels observed in China and some European regions1,21. In the entire state of California, EV sales shares reached 26% during 2024, whereas EVs accounted for only 1.8% of sales across the state of North Dakota during the same year19.

As markets expand, EVs are becoming available in increasingly larger vehicle segments, with many electric sport utility vehicles pickup trucks and delivery vans now being available22. In the USA, electric buses represent about 3% of total bus sales, with almost 6,000 units being sold during 2023 (10% sales growth compared with 2022)3. Recent investments are expected to accelerate electric-bus adoption; for example, US Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean School Bus Program, which was established during 2021, provides US$5 billion to replace existing school buses with zero-emission and clean school buses23. For comparison, new sales shares for electric city buses have been above 50% for 8 consecutive years in China, with sales ranging between 40,000 and 90,000 units per year1,24. During 2023, Europe experienced a surge in EV city bus sales, reaching more than 40% of the market share1.

Global electric truck market share remains below 5% as of 2024 (ref. 1), with deployment concentrated in China. However, technology offerings and interest have grown substantially since 2020, and sales of electric trucks grew more than 80% year over year1. US market for electric medium-duty and heavy-duty vehicles (MHDVs) is at an early stage, accounting for 1.4% of sales during 2024 for classes 3–6 and 0.8% for classes 7 and 8 (ref. 1), trailing the electric LDV market and the global electric truck market by several years. However, traditional truck manufacturers and new technology providers have brought many new truck variants to the market, and fleet customers continue to lock-in large preorders years before their expected delivery dates25. For example, Amazon has reportedly deployed 20,000 electric delivery vans, 140 yard tractors and 50 class 8 trucks as of 2024 (refs. 26,27), and Tesla has reportedly delivered a few hundred of its class 8 semi-trucks28,29. MHDV markets and operations that are particularly amenable to electrification include vehicles that can charge at home bases; have fixed, predictable and/or short routes or rely on off-shift charging; have intensive usage that drives high fuel savings and rapid payback and have disproportionate air-quality impacts30,31. During 2023, North American Council for Freight Efficiency ran a demonstration campaign that showed that it is possible to scale from 1 or 2 trucks at a fleet depot to 30 or more in the following four market segments: terminal tractors, heavy-duty tractors in regional haul, delivery vans and step vans, and medium-duty box trucks32.

EV technology

EV technology has continued to improve, especially for batteries. Global average lithium-ion battery-pack prices reached US$115 kWh−1 during 2024, with a sharp 30% decline since 2020 and a staggering cost reduction of more than 90% in the past 15 years33. Battery-pack prices for battery EVs in the USA fell to around US$130 kWh−1 in 2024 (ref. 33), on average, approaching the US$80–100 kWh−1 range that is generally considered the point at which EVs are at purchase price parity with gasoline vehicles34,35,36,37. In China, 2024 battery prices were reported to be US$75 kWh−1, owing to a sharp fall in raw material prices coupled with manufacturing overcapacity38. As a result, two-thirds of EVs available in China are already cheaper to purchase (based on manufacturer’s suggested retail price) than their internal combustion engine (ICE) equivalents39.

At today’s battery prices in the USA, many LDV and MHDV segments and applications are already at levelized cost parity, with most vehicles expected to reach cost parity by 2035 — or by 2030 with inclusion of US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provisions31. Further cost cuts have come from new cell-to-pack architectures, especially for batteries that rely on lithium iron phosphate (LFP) chemistries manufactured in China40,41. In addition to economies of production scale and manufacturing improvements, there has been a resurgence in using LFP, especially in China, and in general to transition to chemistries with lower cobalt content to manage the risks associated with cobalt supply and to increase energy density42,43. Further innovative chemistries and improved battery-sensing technologies are expected to contribute to improved safety, range and charging speeds and enable a wider range of electrified vehicles to meet the full range of mobility needs44,45,46,47.

Policy landscape

Substantial US policy support for EVs has emerged during the past few years6. This support includes a range of instruments aiming to stimulate demand and support domestic EVs and battery manufacturing, the rollout of technical standards and regulations, the adoption of ambitious public-procurement programmes, the provision of economic incentives to stimulate purchases and promote industrial investments, and the rollout of regulatory frameworks (recently some of these policies have been scrutinized and are being re-assessed)48.

EV-supporting policies are at the federal, state and local level and range from major commitments for EV adoption to EV-procurement programmes49, US$7.5 billion EV-charging investments from the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), incentives and programmes for EV buyers and manufacturers specified in the 2022 US IRA50,51, hundreds of billions of dollars invested in industrial transformation and the 2024 US Environmental Protection Agency final rules on greenhouse gas emissions from LDVs and MHDVs. National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program in IIJA and EV charger tax credits specified in IRA are intended to drive substantial growth in deployment of charging infrastructures and supporting EV adoption. Notably, the US IRA has many EV-related provisions, including tax credits for consumers and manufacturers of electric LDVs, used EVs, electric MHDVs and EV chargers; grants for EV-related research and demonstrations; public-procurement programmes, such as for US Postal Service, transit and school-bus electrification; and public investments in domestic supply chains and manufacturing.

In California, the US state with highest EV adoption (with the exception of few months over the past several years), Advanced Clean Cars II rule was finalized during 2021, which established a tradeable-credit system requiring LDV manufacturers to achieve 35% EV sales share before 2026 and 100% before 2035 (this policy is undergoing legal challenge at the time of writing)52. As of December 2024, 12 other states, representing 40% of the US LDV market, have officially opted into California’s standards53. These targets are comparable to the stringency of other leading jurisdictions around the globe, such as the European Union, the UK and Canada, which have enacted 100% EV sales targets for new vehicles54,55.

For MHDVs, California’s Advanced Clean Trucks rule, which was enacted during 2021 and currently joined in by 11 other states, represents 25% of the US MHDV market. This rule requires zero-emission vehicles to reach 10–75% of the market share between 2025 and 2035. The Advanced Clean Fleets rule was finalized during 2023, adds a 100%-sales requirement in 2036 and specifies requirements for both truck manufacturers and buyers, requiring certain types and fleets of MHDVs to buy electric-only immediately (2024) and to achieve full in-stock fleet electrification by 2035–2045 (advanced clean trucks). We note that Advanced Clean Trucks rule is undergoing legal uncertainty, and Advanced Clean Fleets rule currently is not being enforced due to legal issues, but both remain in state law56. Globally, since 2021, 38 nations have signed onto a global memorandum of understanding targeting 30% new vehicle sales by 2030, 100% sales by 2040 and full market adoption (that is, 100% stock) by 2050 (ref. 57), and some have enacted legislation and regulations to meet or surpass these targets.

The most common stated rationale by governments for these policies includes multiple objectives: reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving air quality, energy security, consumer savings and industrial competitiveness. Most notably, recent US policies including IIJA and IRA complemented support for EV adoption driven by the environmental objectives with clear industrial-policy plans that aimed to overhaul the entire US automotive manufacturing landscape to support global competitiveness58. In conjunction, automakers have made massive investments in the industrial supply chain and in their consumer-facing product offerings1. Established and new automakers are offering a wide range of vehicle technologies within different consumer price points. Since 2020, many automakers have established electrification targets and full ICE phase-out dates for certain brands and regions1 and have invested heavily in the EV and battery industrial sectors38.

Future EV adoption projections

EV adoption has grown substantially in the past 10 years, and most studies expect market share to continue to grow rapidly (Fig. 2), with current projections being more optimistic compared with a few years ago. For LDVs, key global markets have shown more rapid adoption compared with USA, with 95% sales in 2024 in Norway, 50% in China and more than 20% in European Union (aligned with adoption levels in California)1. The progress in these regions demonstrates the potential for near-term rapid increases in US EV sales. Most goals and projections produced before 2020 did not reach 100% EV sales, and many flattened out (that is, EV sales shares stop growing) before 2050, reflecting uncertainty in full electrification10. Most recent projections from the past 5 years have exceeded many past forecasts and some show trajectories towards full transition to EV sales before 2050 (Fig. 2). In the past few years, the MHDV electrification projections have also been showing higher expected deployment with an even more marked growth compared with projections from a few years ago. Many studies show that incentives, total cost of ownership and regulatory requirements can yield MHDV adoption to ramp up more quickly than was predicted during 2021 (ref. 59). These revised projections are based primarily on finance-driven adoption and EVs becoming cost-effective for many applications rapidly, especially based on depot charging30. For many medium-duty vehicles and applications, rapid and full electrification is now expected, with more uncertainty in the largest and heaviest-duty trucks used for long-haul operations in which EVs could struggle to meet operational requirements31.

a, Light-duty vehicle (LDV) trends and projections. b, Medium-duty and heavy-duty vehicle (MHDV) trends and projections. Historical electric vehicle (EV) adoption data show rapid growth over the past 5 years, but substantial differences across regions. Future US projections also show major variability, with some studies projecting continued rapid growth reaching 100% EV sales shares for LDV before 2050 and other studies projecting a gradual growth eventually reaching a stable and more limited market share. As EV adoption continued to grow, more recent studies (circa 2025) consistently project faster ramp-up in EV adoption, as well as higher long-term (2050) sales share levels, compared with older studies (circa 2019). Policy goals in recent years have also substantially increased in ambition relative to past goals and projections. See Supplementary information for data and a complete list of sources included in this figure. EU, European Union; EPA, US Environmental Protection Agency.

The future evolution of EV adoption is governed ultimately by market availability and consumer decisions, which are shaped by far more factors than cost-effectiveness alone60. Vehicle choice involves many factors including social identity61, brand reputation and loyalty62, infrastructure readiness63,64 as well as vehicle performance65. Early adoption research has shown that initial EV buyers tend to be wealthier and more environmentally motivated66,67. Survey and panel data among current EV owners consistently indicate high satisfaction11,12,13,14 and a strong unwillingness to return to ICE vehicles68,69. By contrast, mainstream consumers exhibit lower familiarity with EVs and often report high confidence in their understanding of EV technology, despite holding inaccurate beliefs70. Positive experience with EVs could support EV sales growth through mechanisms such as social influence and neighbourhood diffusion71,72. However, persistent resistance among certain consumer segments, often aligned with political identity in the USA73, coupled with factors such as lack of access to convenient charging, high policy uncertainty and concerns around sourcing and supply chain for battery and motor materials and components, could remain a major barrier to widespread EV adoption. Thus, the long-run trajectory of EV uptake will hinge on the evolving interaction of generational shifts in attitude, peer effects, infrastructure, technology and automotive-marketing evolution and the inherent inertia of vehicle-turnover cycles.

Moving beyond on-road vehicles

Currently, EV deployment is almost entirely limited to on-road applications, but rapid technological progress and increase in manufacturing capacity are spurring interests in leveraging EV technologies to electrify rail, aviation, maritime and off-road vehicles (off-road vehicles encompass a diverse set of off-highway vehicles used in applications such as construction, agriculture, lawn and garden, cargo handling and other activities).

There have been several examples of non-road-vehicle electrification during the recent years. In the maritime sector, cold ironing — in which onboard loads are powered with electricity from the grid while at port (shore power) — is already being used at several ports74. Since 2014, California has required progressively larger shares of cargo fleets calling at all California’s ports to shut down their auxiliary engines and plug into shore power75. Electrified options are also available for recreational boats for both outboard and inboard motors76. Following state mandates, Washington State Ferries has committed to converting its ferry system, the largest in the country, to hybrid electric power by 2040 (ref. 77).

In the rail sector, battery-electric switcher locomotives have been deployed in small numbers78, and multiple studies have shown promising opportunities for rail electrification, including for broader use in short-line and line-haul operations79,80. Owing to the long distances that are traversed by locomotives in North America (with routes spanning thousands of miles), additional electrification options, such as discontinuous overhead catenary lines or intermittent electrification, have also been proposed81,82.

Today, the greatest US adoption of electrified equipment has been in select off-road equipment types such as forklifts and small off-road engines, which have already achieved substantial market penetration83,84. Terminal tractors, which are off-highway vehicles that move trailers and equipment within locations such as warehouses and ports, have also seen some adoption of EVs owing to favourable total cost of ownership, favourable duty cycles for EVs and regulatory pressures in states such as California85. As of January 2025, ~1,500 terminal tractors have been deployed in the USA, with orders rapidly accelerating86.

Future opportunities include electrification of off-road vehicles and equipment, such as construction and mining equipment, with greater power and energy-storage demands. These demands suggest a need for innovative solutions for charging infrastructure87,88,89,90,91, vehicle design, power electronics, electric machines and electric traction-drive systems92,93,94,95, to meet economic and durability requirements. In aviation, fixed-wing and vertical-takeoff-and-landing aircraft have shown electrification potential, with multiple prototypes announced from manufacturers96,97,98,99. The low energy density of batteries (compared with liquid hydrocarbon fuels) makes electrification of long-haul commercial aviation infeasible with today’s technology. However, pathways to electrifying short-haul aviation are being considered100. Container ships have also been proposed as an option for electrification in interregional applications at prices below US$100 kWh−1 and distances below 1,500 km (ref. 101). During 2024, a 50,000-kWh electric container ship was deployed in China to serve a corridor between Shanghai and Nanjing102.

Finally, data limitations remain a challenge for researchers studying several modes of transportation, including data collection and duty-cycle analysis for maritime and off-road posing a challenge for researchers and industry to identify additional opportunities for electrification of non-road modes103,104.

Charging infrastructure

During the past few years, there has been a growing number of scientific studies focusing on charging infrastructure to ensure that as EV markets continue to evolve all consumers can access reliable, affordable and convenient charging. Home charging (or depot charging for commercial vehicles) remains the primary form of EV charging today105, with private chargers outnumbering public 10:1 worldwide1. In the USA, 83% of EV charging occurs at home1, a figure that has remained stable since 2019 (ref. 10). However, the share of drivers with home charging access is expected to decline as more consumers consider EVs, and use of EVs for long-distance travel is increasing, which will increase reliance on public networks106.

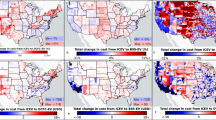

The global network of public EV-charging infrastructure grew 5× (44% year over year) between 2019 and 2024. This included expansion across all regions of the world, and with the growth of DC fast chargers107 outpacing slow chargers1. The growth in the USA was slower, at 20% year-over-year growth. In general, public EV-charging networks grew at a slower pace compared with EV markets (Fig. 3a), as charger utilizations grew.

a, Average annual growth rates between 2019 and 2024 of public electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure (top numbers) and light-duty EV stock (bottom numbers) globally and in select countries1. Generally, the number of EVs has grown faster over the past 5 years than the number of public charging stations, reflecting greater station utilization as charging networks and EV markets matured. These values refer to public charging only and do not include private chargers that represent most charging solutions today. b, Average annual growth rates (between 2019 and 2024) of fast (DC fast charging, DCFC) public EV-charging infrastructure (top numbers) and slow (level 2) public EV-charging infrastructure (bottom numbers) globally and in select countries1. Over the past 5 years, public fast charging networks have generally grown faster compared with public slow charging networks. The values presented refer to public charging infrastructure only, and do not include private charging infrastructure that represents most charging solutions today. Data included in Supplementary Table 2.

As of December 2024, there are 194,216 public charging ports located at 69,145 public charging stations in the USA108. For reference, there are ~145,000 gasoline fuelling stations in the USA109. Of these, 75% are AC level 2 ports (144,692) and 25% are DC fast charging (DCFC) ports (49,524). Recently, there has been a shift towards higher-power public DCFC ports (32% year-over-year growth since 2019) to accommodate larger, longer-range EVs (Fig. 3b). Currently, more than 95% of people in the USA live in a county with at least one public charging station, and 6 in 10 people in the USA live within 2 miles of a public charger110. However, there is substantial geographic variability in access, with 60% of urban residents living within 1 mile of public charging, compared with 41% in suburbs and 17% in rural areas110. Despite this growth, surveys indicate that charging infrastructure remains a primary concern for potential EV buyers, particularly in the USA111,112,113. McKinsey reports that many buyers are unwilling to consider an EV until public charging is as ubiquitous as gas stations113. Another survey found that public perception of US charging infrastructure is declining over time111.

Looking at future expansions, two major phases of EV chargers (that is, electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE)) network development have been described114. First, achieving basic geographic coverage builds consumer confidence and enables interregional travel. In the second phase, the network expands to accommodate growing location-specific charging demands. As a result, the marginal infrastructure need per additional EV is expected to decline as the EV market matures. The number of EVs supported by a public EV-charging station, on average, tends to increase as EV market share grows, as shown in Fig. 4 across multiple regions despite substantial variation owing to region-specific factors.

Public charging-network density (measured as the average number of electric vehicles (EVs) per public charging port) versus light-duty EVs stock share for selected states, countries and the global average in 2024. Bubble sizes are proportional to the number of EV public ports available in that region. In general, the number of EVs supported by each public charger, on average, tends to increase less than proportionally with EV market share, reflecting diminishing marginal infrastructure needs as adoption, and station utilization, grows. However, regional variation remains substantial owing to differences in mobility needs, private charging availability, urban form and other factors impacting need and preference for public charging. Data included in Supplementary Table 4 (Supplementary Table 3 reports 2019 data for comparison).

Future EV-charging needs and solutions

Thirty-eight countries have announced targets and/or legally binding commitments for the deployment of EV-charging infrastructure1. The International Energy Agency projects that the global EV-charging network must grow to approximately three times its current (2024) size by 2030, adding 11.7 million new charging ports (21% year-over-year growth)1. However, infrastructure projections are region-specific and affected by uncertainty. Multiple studies have forecasted 2030 light-duty EVSE network requirements in the USA (Supplementary Table 5), showing different results depending on assumptions for EV fleet size and composition, home charging access and EVSE utilization, among other factors1,115,116,117,118,119,120. Overall, the projected 2030 electric LDV stock ranges from 26 million to 57 million vehicles (median 38 million EVs), and port requirements vary from 9.5 million to 28.5 million (median 26.3 million) for home ports, 110,000 to 460,000 (median 180,000) for public DCFC ports and 240,000 to 3.2 million (median 1.6 million) for public and/or work level 2 ports.

With growing charging networks and more diverse consumers and vehicles using them, the reliability of public chargers has become a key area of focus across the industry. In a 2023 study, only 72% of San Francisco Bay Area EVSE ports were found to be operational121. J.D. Power and Associates reported similar findings in a survey, claiming that 20% of the US EV drivers had recently visited a public charger and been unable to charge122. Multiple programmes are working to improve reliability, such as US National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program’s minimum uptime requirements and US National Charging Experience Consortium, and are showing signs of progress123.

Efforts to ensure interoperability of EV charging are also making progress. In North America, automakers are converging around the SAE J3400 standard (Tesla Connector) for LDV124. Globally, standardized communication protocols such as ISO 15118, Open Charge Point Protocol and Open Charge Point Interface are increasingly adopted, enhancing convenience, reducing costs and improving reliability for drivers125. Beyond LDVs, global standards for megawatt-scale charging of electric MHDVs have been developed, including the Megawatt Charging System (SAE J3271), rated for up to 3.75 MW (ref. 126).

Outside leading countries for EV adoption, such as China and Norway, the penetration of electric MHDVs and associated charging infrastructure is limited to date1 (Fig. 2). Early deployments primarily consisted of privately owned installations at a vehicle depot, and for easy-to-electrify vehicle segments, such as buses and delivery vans25. Private companies have had a substantial role in these initial efforts — for example, Amazon has installed more than 17,000 chargers at 120 warehouses across the USA, making them the largest reported operator of private EVSE in the country127. Extended lead times for MHDV charging deployments — potentially up to 4 years if utility upgrades are required30 — are a major barrier to fleet electrification and must be streamlined going forward. With increasing global ambition around transportation decarbonization, there is an emerging emphasis on long-term planning for commercial electric MHDVs. The USA released its National Zero-Emission Freight Corridor Strategy, outlining a phased approach to electrifying over-the-road freight128. National planning documents for EVSE for MHDVs have also been produced for European Union129 and Canada130.

Mobile charging stations are also emerging as a potential solution to tackle peaks in charging demand (such as during holiday travel or large events), provide charging during emergencies and in general provide charging where installing fixed infrastructure is challenging. In China, mobile charging stations have been deployed to address the growing demand for EV charging131. These stations offer flexible charging solutions, enhancing the convenience and accessibility of EV-charging services. Although research on this topic is limited, a 2022 study found that mobile charging stations can be more economical than fixed charging stations in some cases132.

Plug-in conductive charging systems continue to be the primary form of EV charging globally1 and is expected to remain so during the foreseeable future. However, several alternatives are gaining interest133. Stationary wireless charging uses inductive power transfer to transmit electricity between a ground-based transmitter coil and a receiver coil mounted to the base of the vehicle, enabling EVs to charge without a physical connection. During 2024, researchers at US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory successfully demonstrated the first 270-kW wireless power transfer to an LDV134. Power transfer rates up to 100 kW with efficiencies comparable to traditional plug-in systems have been achieved135,136. Pilot projects have demonstrated the potential of wireless charging; for instance, the city of Mannheim, Germany, has implemented stationary wireless charging for electric buses, allowing them to extend their range by charging at stops without manual intervention137. Despite these developments, widespread EV adoption faces challenges such as high infrastructure costs, inconsistent efficiency and the lack of standardization across vehicle manufacturers. Their most promising application might be in providing a charging solution for autonomous EVs, enabling seamless and unattended operation, although the timeline for widespread deployment remains uncertain.

Battery swapping is also becoming increasingly popular: in 2023, there were more than 3,500 battery swapping stations in China, with a target to exceed 16,000 battery swap stations in the country during 2025 (refs. 138,139). These stations are primarily for two-wheelers and LDVs. However, the shift to heavier applications is underway, with nearly half of the electric heavy-duty trucks sold in China in 2022 capable of swapping140.

Another alternative is electric roadways, where electricity is supplied to EVs either conductively (via catenary or ground-based systems) or inductively (dynamic wireless power transfer) while the vehicle is in motion. Demonstrations have been conducted in Germany, Sweden, Italy, Israel and USA141,142. However, there have been considerable challenges to scaling these technologies to date, including high development costs, limited vehicle compatibility and the standardization of routes and vehicles necessary to maximize effectiveness.

As these different charging technologies and solutions continue to evolve and are being deployed, it is possible that a mix of solutions including slow and fast charging stations, mobile charging solutions, wireless charging, battery swapping and more will be deployed to meet diverse and rapidly evolving consumer and commercial needs and expectations. Overall, finding convenient, reliable and affordable charging solutions for garage orphans (EV users or potential users who lack reliable access to dedicated private charging, for example, at home or a depot where the vehicle is consistently parked) and for long-distance travel remains critical for long-term EV success.

Vehicle–grid integration

Although EVs used less than 0.2% of total US electricity consumption during 2023 (ref. 143), with the EV stocks increasing, the electricity demand to charge them will increase progressively. Studies project electricity demand for EV charging possibly to reach 20–50% of total 2023 electricity demand by 2050 (refs. 144,145,146). This electricity-demand growth, following about two decades of stagnation147, is likely to require investments in electricity-generation, electricity-transmission and electricity-distribution systems147,148,149,150,151,152. Indeed, transportation electrification is likely to occur as other sources of demand are added to electricity systems, such as data centres, electrification of residential end uses and heating and electrification of industrial processes144,153,154. In addition, EV-charging demand is expected to be spatially concentrated within electricity-distribution networks owing to spatial clustering in EV adoption155,156 and high-power demand from large public charging stations, especially for commercial vehicles157,158,159,160,161.

Electricity-demand growth to charge EVs has not been a burden to electricity systems but rather a resource that can reduce costs and increase reliability162. Several studies suggest that, when managed effectively, EVs can reduce system costs and support electricity-system reliability. Research indicates that EVs offer opportunities to improve asset utilization as the cost of the additional infrastructure is spread across more units of electricity sold, exerting downward pressure on retail rates (that is, EVs have reduced the cost of electricity for consumers)151,152,163,164,165,166,167,168,169. For example, Natural Resources Defense Council found that between 2011 and 2021, EV drivers across the USA contributed approximately US$2.4 billion in revenue for utilities net of their associated costs — including utility expenditures for EV programmes — putting downward pressure on electricity rates for all customers169.

Coordinated EV charging

Coordinating (or managing) EV charging offers several benefits, demonstrated through research and real-world applications, including enhancing electricity-system resilience and reducing EV charging and electricity costs. EVs can support electricity systems along multiple value streams (for an overview of the benefits that EVs can provide, see Fig. 6 from ref. 170). However, the trade-offs among the various services that managed charging could provide (for example, reshaping EV charging to minimize the needs for generation vis-a-vis distribution capacity expansion) and the cost of implementing different strategies to realize coordinated charging remain to be explored149,170. The benefits of coordinated EV charging arise from inherent flexibility in EV charging because vehicle usage and driving patterns result in passenger vehicles being parked typically 96% of the time170,171,172. Commercial vehicles also offer major opportunities for charging flexibility173,174. Moreover, most EV trips do not require the vehicle to charge continuously while parked to have sufficient energy available for its next trip. Consequently, most EVs have a window of time within which they can be charged during each parking event and do not necessarily need to charge every day to meet all of their mobility needs30,170.

Studies and demonstration programme demonstrate that coordinating EV charging with operation of the electricity system to which the vehicle is connected (that is, changing the timing and power level of EV charging) has the potential to provide various benefits, including more efficient, less costly and lower-emissions electricity-system operations170,175,176,177,178,179,180; alleviating electricity-system capacity constraints181,182,183,184,185; managing real-time imbalances between electricity supply and demand (such as voltage and frequency stability)186,187,188; and facilitating the integration of weather-dependent renewable energy sources into electricity systems189,190. A review of hundreds of modelling studies concluded that managed EV charging could provide thousands of dollars of value annually per each EV170, and that even consumers who do not own an EV and do not participate to these programmes could benefit from electric-bill savings166.

Vehicle-to-grid and beyond

In addition to the benefits from coordinated EV charging, the ability to discharge EVs’ batteries to power other loads (vehicle-to-everything (V2X)) or inject electricity to the electricity system (vehicle-to-grid (V2G)) transforms EVs into active grid assets that offer additional value.

V2X can serve as a reliable backup power source for critical load restoration in the event of a power outage191, with many instances in the USA wherein EVs powered residential loads and other critical buildings in their community during natural disasters that caused outages162. Quantifying the cost of outages to consumers and their willingness to pay for reducing lost load is complex. Nonetheless, there is consensus that consumers value backup power, particularly in areas with frequent power outages or in locations with vulnerable grids to extreme weather events such as hurricanes or tornadoes192. Survey data show that 84% of survey participants from the USA are concerned about growing power outages and 15% of US homeowners have a backup power generator193, and Global Market Insights reports that consumers in the USA spent almost US$4 billion in portable generators in 2024 (ref. 194). As a result, automakers are increasingly including the capability to discharge EV batteries and provide backup power195.

V2G services provide value to electricity systems by discharging stored energy from EV batteries and injecting it into the grid, in addition to managing EV charging. V2G further enhances the benefits of coordinated charging, including lower cost196,197,198, lower emissions197,199,200,201,202 and further improvements to electricity-supply reliability and resilience203,204,205,206, especially during extreme or emergency events191,207,208,209. The bidirectional capability mitigates infrastructure stress by enabling EVs to store excess power and distribute it during demand peaks or supply shortages, substantially enhancing grid stability and facilitating integration of variable renewable sources178,210,211,212,213. V2G also enables supporting other loads and increasing resilience by providing distributed energy storage for non-EV consumption. Although two-way V2G services that allow discharging electricity from EVs back into the grid have been piloted214,215,216 and shown to provide more value than one-way vehicle charge scheduling in recent analyses170, most utility EV programmes available currently focus on one-directional charge management217.

Enabling synergistic improvement of the efficiency and economics of EVs and electricity systems via managed charging depends upon addressing two significant and interrelated barriers: providing EVs with information that is needed to determine their charging and discharging and market reforms to enable full EV participation in electricity markets and avoid agency problems. Electricity-system conditions and operating needs change rapidly. As such, implementing effective EV-managed charging is practical only if vehicle charging and discharging are automated, which require standardized and reliable real-time electricity-system data (and vehicle data for more advanced controls)218,219. During the past four decades, electricity systems have evolved away from a centralized command-and-control architecture towards the use of price-based signals for the provision of electricity services220. Thus, price-based signals are likely to have an outsized role in the provision of charging coordination and V2G services221,222,223. The electricity, charging infrastructure and automobile industries are taking important steps to develop communication standards (such as SAE 2954 and J3072) that can manage and coordinate EV charging and discharging with suitable levels of security and reliability224.

Barriers, challenges and opportunities

Agency problems arise from misaligned incentives between the electricity system and EV owners. One type of agency problem stems from the inability of EV owners to monetize the value that coordinated vehicle charging or V2G services provide to the electricity system223,225,226,227. The use of price-based signals in determining vehicle charging and discharging could mitigate this type of agency problem, but only if prices include all possible services that EVs provide and are designed to avoid unintended consequences. Non-convexities, uncertainties and other system characteristics and market failures can complicate the design of suitable pricing schemes and resultant EV-charging and EV-discharging patterns228,229,230. For example, widespread EV charging responding to simple time-of-use electricity price structures has been shown to create rebound peaks that can be more problematic than the original uncoordinated EV charging demand peaks231,232.

Another agency problem stems from potential accelerated ageing of EV batteries, especially if they are discharged to provide V2X or V2G services233,234,235. Battery ageing or degradation is complex and empirical data on impact of V2X on long-term battery degradation are difficult to document and require long experimental campaigns. Some studies report that the main drivers of battery ageing are cell chemistry and the ambient temperature where the car is operated, while battery usage and charging patterns have a lesser role236. Other studies show that although most battery degradation is driven by calendar degradation (85–90%), using EV batteries to provide services could substantially accelerate cyclic degradation, depending on how batteries are operated237. At the same time, dynamic discharge has been shown to enhance battery lifetime substantially236,238. Similarly, empirical studies are reporting lower degradation than expected from fast charging of EV batteries239. Overall, the impact of V2X on battery life remain an active area of research.

Developing strong policy and regulatory frameworks, including possible market reforms and retail tariff design to monetize and compensate consumers for the full value of demand-side flexibility, is critical to optimize grid efficiency and resilience, protect consumer interests, reduce costs and encourage investment in infrastructure while addressing challenges related to interoperability and cybersecurity. Moreover, programmes could suffer from misperceptions on the part of EV owners who do not understand the benefits of coordinated charging or V2G services240. As such, the design of educational, informational and messaging programmes about EV charging and V2G services might be as important as (if not more important than) the design of wholesale and retail pricing structures.

The success of smart charging and V2G systems depends not only on technological and market advancements but also on the willingness and ability of EV users to engage with these programmes. Behavioural factors influence whether EV owners opt into managed charging or V2G services, as well as how consistently they participate241. Participation rates can be affected by perceived complexity, mistrust in technology or third-party operators and the level of direct financial benefits offered242. Moreover, preferences for autonomy and convenience often compete with the potential benefits of adopting managed charging practices243. Educational and informational campaigns have a pivotal role in addressing these challenges, as they can help to dispel myths, clarify potential benefits and reduce perceived risks. Some behavioural-economics research indicates that simplifying participation through default enrolment or opt-out mechanisms could substantially increase uptake rates for managed charging and V2G programmes244. Additionally, consumer trust is critical and can be fostered through transparent communication about data privacy, battery-health impacts and the reliability of smart-charging systems. Finally, some studies show that designing behavioural nudges, such as gamification or real-time feedback on cost savings and environmental benefits, could further enhance participation and satisfaction245,246,247.

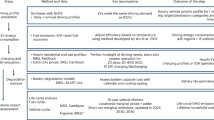

Projecting the charging requirements of EVs, the ability of EVs to participate in charging coordination or provide V2X services and related electricity-system-infrastructure needs are the first key steps to explore the impact of and opportunities that arise from integrating EVs into electricity systems. Accordingly, a vast array of modelling tools have been developed to study these interactions between EVs and electricity systems at various degrees of spatial, temporal and modelling resolution30,145,248,249,250,251,252,253,254. Greater fidelity and resolution of EV charging needs are needed to explore more complex ways for EVs to support electricity systems, with commensurate increase in model complexity (Fig. 5).

Several models and tools have been developed to explore the electric vehicle (EV)–grid nexus, with different modelling approaches and resolutions targeting different applications. Low-fidelity models (left) are focused on estimating aggregate EV load evolutions over years for long-term planning and techno-economic analysis. Mid-fidelity models (middle) try to estimate hourly EV charging loads balancing detail and efficiency for system-performance studies over operational timescales. High-fidelity models (right) attempt to capture real-time vehicle behaviour to provide detailed insights that are needed to realize the full potential of EV–grid integration.

Supply chains, manufacturing and competitiveness

The growing global shift to EVs and increasing value of batteries as electricity system and behind-the-metre storage have increased further the strategic attention to battery manufacturing and supply chains255,256,257,258. Additionally, the automobile industry — both final vehicle assembly and parts manufacturing — is a major US employer and a keystone economic driver in many communities, which has led to policy commitments to reinvest in this sector259. The global shift to EVs has led to a series of efforts from federal and state policymakers to increase the investment in US EV manufacturing, reflecting a greater awareness about the value of EVs as a strategic opportunity for industrial competitiveness, employment and global geopolitics58,259,260,261.

Critical materials in batteries

There are several types of lithium-ion batteries with different compositions of cathode metals, with the main chemistries currently in use for EVs being LFP, nickel–cobalt–aluminium and nickel–manganese–cobalt (NMC)43 (Box 1). The name of battery chemistry typically indicates the composition of the cathode. For example, an NMC811 battery has a cathode composition of 80% nickel, 10% manganese and 10% cobalt. The higher nickel content in NMC batteries tends to increase their energy density262, which helps to increase EV driving range. Cobalt and manganese act as stabilizers to help improve thermal stability263. LFP batteries offer lower energy density but at a lower cost owing to the use of iron and phosphate instead of nickel264. Additionally, lithium carbonate is used instead of the lithium hydroxide used in nickel-based batteries. LFP is considered one of the safest chemistries and LFP batteries are renowned for their longevity, typically enduring a substantially longer lifespan than many conventional lithium-ion chemistries265.

Materials used in EV batteries that attracting and experiencing global interest are lithium, nickel, cobalt and graphite (as well as copper, although batteries are a relatively small component of global copper demand, see Supplementary Table 6). Although lithium is the energy carrier, it represents a relatively modest amount of the total battery mass and value (Box 1). For several of these materials, lithium-ion battery already constitutes the majority of global demand (Supplementary Table 8), and so battery costs are tightly linked to the prices and supply of these materials. New and more diverse chemistries can address some supply-chain concerns by providing alternatives when specific material prices rise or supplies are disrupted266. For example, LFP batteries have no nickel or cobalt, silicon anode batteries have no graphite, and sodium-ion batteries replace lithium as the energy carrier. The global market has already seen an increasing interest towards LFP batteries, with their share growing to more than 40% during 2023, quadrupling from its share of about 10% during 2015 (ref. 1). Ninety-five percent of these batteries are destined for the Chinese market, but are now increasingly finding markets across the world, including the US market and under IIJA and IRA, now there are investments that are focused on processing LFP cathodes and cells in the USA267,268.

Supply-chain policies and investments

Investments in EVs and batteries have exceeded US$750 billion globally during 2024, the largest in clean energy and more than solar and wind combined38. So far, the investments in EVs turned into an export opportunity for China — also facilitated by foreign-policy instruments, particularly the Belt and Road Initiative269. Just two decades ago, China had little capacity to manufacture cars. Today, China produces more cars than any other country in the world and is the world’s largest car exporter270. During 2023, China exported about 5 million cars including 1.7 million EVs, nearly 50% more than the next largest exporter, Germany271. Both EVs and renewable electricity production from wind and solar have become key elements of a major global power competition for industrial growth, spurring responses that bear risks of industrial policy nationalism272. COVID-19-related stimulus packages included substantial investment to deploy infrastructure supporting the energy transition, including but not limited to EV charging and EV manufacturing273. Other major policy packages, including the US IIJA and IRA259 and several tools included in European Union’s Green Deal Industrial Plan274, clearly show a growing response to similar moves brought forward by China already a decade ago269.

The EV-battery supply chain includes mining minerals; processing minerals into material precursors, active materials and other subcomponents; manufacturing components such as the cathode, anode, separator and electrolyte; cell assembly; and combining cells into packs, including hardware and management systems. China has focused investments on EVs and the clean-energy supply chain for decades, leading to a global dominance in terms of critical mineral refining and battery manufacturing275. China leads every step of the global EV-battery supply chain and their markets, from refining materials to the production of cathode and anode materials and battery cell manufacturing (Fig. 6). Today, China produces more than 75% of global lithium-ion battery cells and its cell-production capacity is more than double the amount needed to meet the country’s battery-cell demand1. China also produces and purchases over half of the world’s EVs.

Electric vehicle (EV)-battery supply chains have a global coverage and include mining of multiple materials in several countries, processing and manufacturing of battery components and cells — which today are primarily based in China — and finally EV manufacturing and vehicle sales (registrations) that tend to be more diversified and correlated with one another1. DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo. Note: these data presented in this study are derived from International Energy Agency materials, and the authors of this study are solely liable and responsible for these derived data. The derived data presented in this study are not endorsed by the International Energy Agency in any manner.

Concerns around battery supply chains have led to efforts around the world, including in the USA, to develop alternative supply chains for minerals and domestic manufacturing capacity for EVs. The US strategy is informed by several strategic documents, including The National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries276, the Li-Bridge public–private initiative’s Building a Robust and Resilient U.S. Lithium Battery Supply Chain277 and A Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals278. The most extensive policies currently in place to increase investment in the USA and trade-partner capacity are through the 2021 IIJA and 2022 IRA. IIJA funded more than US$7 billion in direct investments throughout the supply chain, as well as novel research and demonstration of battery-recycling technology259. The US IRA updated the 30D new-vehicle tax credit to include increasing requirements for domestic content for battery components and domestic and free-trade partner content for critical minerals279. In addition, the IRA created a 45× tax credit for battery cells, modules and minerals worth more than US$45 kWh−1 of battery for US production280. Finally, the 48C tax credit provides up to 30% of the investment cost in facilities for many clean-energy sectors, including battery and EV manufacturing281. Some of these policies are under scrutiny and are being re-assessed at the time of writing48.

During the past 10 years, manufacturers have announced US$198 billion in investments in US EV-battery-manufacturing facilities (83% just during the past 3 years)282. Multiple sources estimate that by about 2030, US battery-manufacturing facilities have the potential of supplying batteries for over 10 million new EVs each year (comparable to today’s total US domestic vehicle manufacturing)283. Lithium-Ion Battery Supply Chain Database offers a directory of companies with facilities in North America representing the lithium-ion-battery supply chain284.

Recycling is another component of a supply-chain strategy, because it can lead to minerals from end-of-life batteries staying in the US markets285. Although the number of end-of-life EVs so far is low (because most EVs were built recently), recycling will continue to have a larger role and by the 2030s can meet a substantial share of demand for key minerals, such as nickel and cobalt286,287. The largest global markets for EVs, namely, China and European Union, have implemented or are in the process of implementing comprehensive polices surrounding EV-battery recycling288,289,290, but USA still has no federal policy for EV-battery recycling. At the state level, the biggest US market, California, does not have any recycling policies in place for EV batteries either. Despite the lack of policy, there has been rapid investment in US recycling capacity, and lead-acid batteries are recycled at as much as 99% (ref. 291). The success of lead-acid battery recycling sets a precedent for the EV end-of-life industry to achieve high lithium-battery recycling as well, if proper regulatory mechanisms are in place to encourage recycling and high recovery rates.

One key remaining area of focus is to create consistent mechanisms for providing battery information to stakeholders across the supply chain (a ‘battery passport’), including material traceability, as well as information to assist in handling and recycling during battery end of life292,293. Such information in a battery passport would enable more precise tracking of material flows and contributions, sustainability assessments and risk assessment for supply-chain vulnerabilities and dependencies.

Summary and future perspectives

The steady growth of global EV sales during the past few years (55× sales increase since 2014 and 6× since 2020)1 has been driven by technology progress enabled by supportive policies and massive industrial investments in EV and battery manufacturing and charging networks, providing strong indicators for continued growth in the EV market. Although most of this growth in the USA has been in the LDV sector, EVs have started to be adopted for MHDV on-road applications and there is growing interest around electrification of rail, maritime, aviation and off-road vehicles. Overall, EVs show strong potential for broader adoption across a range of transportation modes, based on current technological trends and market developments.

This growth has been driven in large part by continued improvement in EV technologies — most notably, the continued improvement in battery cost and energy density that is rapidly making EVs cheaper than ICE vehicles. Although considerable consumer scepticism remains in the USA, the reduction in purchase price and increased exposure to more EVs on the market and the expansion of charging infrastructure are starting to address some of these concerns1. Continued improvement is required to ensure that EVs can be an affordable and convenient solution for everyone. Perhaps, the largest remaining barrier to EV adoption is the ability to charge EVs conveniently, especially for garage orphans who do not have access to a private charger (for example, at home or a depot for commercial vehicles). Although most EV charging is expected to continue to be done at home or depot private chargers, where the vehicles are parked for longer periods of time294,295, there is a need for a ubiquitous network of convenient and reliable public charging stations25. Considerable progress has been made in the build-out of public charging infrastructure during the past several years. However, more work remains to ensure that the charging experience is reliable and comparable to the experience of fuelling an ICE vehicle at a gas station, and that stations are accessible to everyone.

EVs are the lowest life-cycle-emission options in motorized on-road transportation8. Although emissions during vehicle operation keep decreasing as the grid becomes cleaner, vehicle-production emissions today account for about 10% of total life-cycle EV emissions8 and there are studies exploring solutions to reduce emissions associated with vehicle and component manufacturing296,297,298.

Rapid growth of EVs would lead to increased demand for electricity and significant temporal and geographical changes in electricity–load profiles. Modelling studies and empirical analyses show that EVs offer opportunities to improve electricity-asset utilization and have been putting downward pressure on US electricity rates163,164,169,285,297,298. Moreover, several studies suggest that coordinated EV charging can yield substantial benefits and synergies including supporting other loads, enhancing electricity-system resilience and reducing electricity costs further170. However, exploiting fully the benefits of EV coordinated charging depends on addressing technical (especially real-time communication) and market barriers to enable full EV coordination with electricity systems and participation in electricity markets.

Finally, the transition from ICE vehicles to EVs offers a unique industrial opportunity: large investments in manufacturing capacity of EVs and EV components represent a major prospect to increase US automotive and component manufacturing, a sector that employs more than 4 million people in the USA, including manufacturing and retail299. Recent EV-related policies and investments reflect a greater awareness by governments and industry of the strategic value of vehicle electrification — not only as a solution for climate change, air quality and energy security but also as a strategic opportunity for industrial competitiveness, employment and control of global material resources58,260,261. Research and analysis at the intersection of energy, industrial policy and geopolitics has been growing, but many complex interactions and effects remain to be explored.

Although forecasting the future is impossible, the current trajectory of technology improvements, policy support and industrial investments points to continued acceleration of EVs for on-road vehicles and growing adoption of EVs for many non-road applications. This Review provides a summary of the recent progress made in the EV space, grounded in scientific and technical publications, and outlines many of the remaining barriers for long-term success of EVs. The authors of this Review conclude that these barriers can be addressed, increasing the likelihood of a mobility system that is efficient, affordable, clean and resilient.

References

International Energy Agency. Global EV outlook 2025. International Energy Agency https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025/outlook-for-electric-mobility (1025).

Al-Alawi, B. M. & Richard, J. Zeroing in on zero-emission trucks: May 2024 market update. CALSTART https://calstart.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/ZIO-ZET-May-2024-Market-Update_Final.pdf (2024).

Hynes, M., Crippen, A., Lemons, K. & Varnell, E. Zeroing in on zero-emission buses. CALSTART https://calstart.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Zeroing-in-on-ZEBs-2024_Final-022324a.pdf (2024).

Bhardwaj, S. & Mostofi, H. Technical and business aspects of battery electric trucks — a systematic review. Future Transp. 2, 382–401 (2022).

Manzolli, J. A., Trovão, J. P. & Antunes, C. H. A review of electric bus vehicles research topics — methods and trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 159, 112211 (2022).

US Department of Energy, US Department of Transportation, US Environmental Protection Agency & US Department of Housing and Urban Development. The U.S. National blueprint for transportation decarbonization: a joint strategy to transform transportation https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2023-01/the-us-national-blueprint-for-transportation-decarbonization.pdf (US DOE, 2023).

Hoehne, C. et al. Transportation in net-zero emissions futures: insights from the EMF-37 model intercomparison study. Energy Clim. Change https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egycc.2025.100211 (2025).

Kelly, J. C. et al. Cradle-to-grave lifecycle analysis of U.S. light-duty vehicle-fuel pathways: a greenhouse gas emissions and economic assessment of current (2020) and future (2030—2035) technologies. Report no. ANL-22/27 (Argonne National Laboratory, 2022).

BloombergNEF. Energy transition investment trends 2025. BloombergNEF https://about.bnef.com/insights/finance/energy-transition-investment-trends/ (2025).

Muratori, M. et al. The rise of electric vehicles — 2020 status and future expectations. Prog. Energy 3, 022002 (2021).

Plug in America. EV Driver Survey, June 2025 (Plug in America, 2025).

Plug in America and EPRI. EV Driver Annual Survey report, 2024 (Plug in America, 2024).

Probolsky Research. Veloz Electric Vehicle Survey (Probolsky Research, 2024).

J. D. Power. Majority of electric vehicle owners are intent on purchasing another one in the future, J.D. Power finds. J. D. Power https://www.jdpower.com/business/press-releases/2021-us-electric-vehicle-experience-evx-ownership-study?srsltid=AfmBOopTI0_365-lfqAHO8hfUaDfguRTttDBt21Y5Dsh9jBC7OA41xdD&utm_source=chatgpt.com (2021).

Ooi, S. K., Xu, Y. & Yeap, J. A. L. Beyond the first charge: understanding continuance intention among electric vehicle drivers in China. Res. Transport. Bus. Manag. 61, 101420 (2025).

Dixon, J., Andersen, P. B., Bell, K. & Træholt, C. On the ease of being green: an investigation of the inconvenience of electric vehicle charging. Appl. Energy 258, 114090 (2020).

Noailly, J., Nowzohour, L. & van den Heuvel, M. Does environmental policy uncertainty hinder investments towards a low-carbon economy? Preprint at National Bureau of Economic Research https://doi.org/10.3386/w30361 (2022).

Pamidimukkala, A., Kermanshachi, S., Rosenberger, J. M. & Hladik, G. Barriers and motivators to the adoption of electric vehicles: a global review. Green Energy Intell. Transport. 3, 100153 (2024).

Alliance for Automotive Innovation. Get connected: electric vehicle quarterly report, fourth quarter, 2023 https://www.autosinnovate.org/posts/papers-reports/Get%20Connected%20EV%20Quarterly%20Report%202023%20Q4.pdf (Alliance for Automative Innovation, 2024).

California Energy Commission. Light-duty vehicle population in California. California Energy Commission https://www.energy.ca.gov/data-reports/energy-almanac/zero-emission-vehicle-and-infrastructure-statistics-collection/light (2024).

California Energy Commission. New ZEV sales in California. California Energy Commission https://www.energy.ca.gov/data-reports/energy-almanac/zero-emission-vehicle-and-infrastructure-statistics-collection/new-zev.

Alternative Fuels Data Center. Availability of electric vehicles. US Department of Energy https://afdc.energy.gov/vehicles/electric-availability (2024).

US Environmental Protection Agency. Clean School Bus Program. US Environmental Protection Agency https://www.epa.gov/cleanschoolbus (2024).

Cazzola, P., Alfageme, M. S. & Ramji, A. Facilitating a transition to zero-emission vehicles in the global south. ZEV Transition Council, UC Davis ITS and FIA Foundation https://www.fiafoundation.org/resources/facilitating-a-transition-to-zero-emission-vehicles-in-the-global-south (2023).

Muratori, M., Borlaug, B., Ledna, C., Jadun, P. & Kailas, A. Road to zero: research and industry perspectives on zero-emission commercial vehicles. iScience 26, 106751 (2023).

Amazon. Everything you need to know about Amazon’s electric delivery vans from Rivian. Amazon https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/transportation/everything-you-need-to-know-about-amazons-electric-delivery-vans-from-rivian (2024).

Amazon. Amazon’s largest fleet of heavy-duty electric trucks hits the road. Amazon https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/sustainability/amazon-electric-trucks-southern-california-sustainability (2024).

Mahoney, N. Tesla plans to ramp up electric semi truck production in 2026. Freight Waves https://www.freightwaves.com/news/tesla-plans-to-ramp-up-electric-semi-truck-production-in-2026 (2024).

Ashraf, A. Tesla semi ready to replace diesel trucks, says unit head as he cheers EPA’s tough new standards. Benzinga https://www.benzinga.com/government/24/04/38039010/tesla-semi-ready-to-replace-diesel-trucks-says-unit-head-as-he-cheers-epas-tough-new-standards (2024).

Borlaug, B. et al. Heavy-duty truck electrification and the impacts of depot charging on electricity distribution systems. Nat. Energy 6, 673–682 (2021).

Ledna, C. et al. Assessing total cost of driving competitiveness of zero-emission trucks. iScience 27, 109385 (2024).

North American Council for Freight Efficiency. Electric truck depots are evolving: how 10 fleets grew their BEV populations. NACFE https://nacfe.org/research/run-on-less/run-on-less-electric-depot/ (2025).

BloombergNEF. Lithium-ion battery pack prices see largest drop since 2017, falling to $115 per kilowatt-hour. BloombergNEF https://about.bnef.com/blog/lithium-ion-battery-pack-prices-see-largest-drop-since-2017-falling-to-115-per-kilowatt-hour-bloombergnef/ (2024).

Soulopoulos, N. When will electric vehicles be cheaper than conventional vehicles? Bloomberg New Energy Finance https://www.blogmotori.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/EV-Price-Parity-Report_BlogMotori_COM_MobilitaSostenibile_IT.pdf (2017).

Slowik, P., Isenstadt, A., Pierce, L. & Searle, S. Assessment of light-duty electric vehicle costs and consumer benefits in the United States in the 2022–2035 time frame. International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) https://theicct.org/publication/ev-cost-benefits-2035-oct22/ (2022).

Knupfer, S. M., Hensley, R., Hertzke, P. & Schaufuss, P. Electrifying insights: how automakers can drive electrified vehicle sales and profitability. McKinsey & Company https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/electrifying-insights-how-automakers-can-drive-electrified-vehicle-sales-and-profitability#/ (2017).

Burke, A. F., Zhao, J. & Fulton, L. M. Projections of the costs of light-duty battery-electric and fuel cell vehicles (2020–2040) and related economic issues. Res. Transport. Econ. 105, 101440 (2024).

BloombergNEF. Energy transition investment trends 2024. BloombergNEF https://assets.bbhub.io/professional/sites/24/Energy-Transition-Investment-Trends-2024.pdf (2024).

McKerracher, C. China’s batteries are now cheap enough to power huge shifts. Bloomberg https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2024-07-09/china-s-batteries-are-now-cheap-enough-to-power-huge-shifts (2024).

BYD. BYD’s revolutionary blade battery: all you need to know. BYD https://www.byd.com/eu/blog/BYDs-revolutionary-Blade-Battery-all-you-need-to-know.html (2023).

Zhang, P. Battery price war: CATL, BYD pushing battery costs down further. CnEVPost https://cnevpost.com/2024/01/17/battery-price-war-catl-byd-costs-down/ (2024).

Abuelsamid, S. Lithium iron phosphate set to be the next big thing in EV batteries. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/samabuelsamid/2023/08/16/lithium-iron-phosphate-set-to-be-the-next-big-thing-in-ev-batteries/ (2023).

Seck, G. S., Hache, E. & Barnet, C. Potential bottleneck in the energy transition: the case of cobalt in an accelerating electro-mobility world. Resour. Policy 75, 102516 (2022).

Machín, A. & Márquez, F. The next frontier in energy storage: a game-changing guide to advances in solid-state battery cathodes. Batteries 10, 13 (2024).

Koech, A. K., Mwandila, G. & Mulolani, F. A review of improvements on electric vehicle battery. Heliyon 10, e34806 (2024).

An, C. et al. Advances in sensing technologies for monitoring states of lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Source 625, 235633 (2025).

Hatano, Y. et al. High-precision robust monitoring of charge/discharge current over a wide dynamic range for electric vehicle batteries using diamond quantum sensors. Sci. Rep. 12, 13991 (2022).

Buckberg, E. & Cole, C. Trump EV policy overhaul: what will happen to EV adoption, emissions, and the fiscal balance? https://salatainstitute.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Policy-Brief_Trump-EV-Policy-Overhaul.pdf (The Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability at Harvard University, 2025).

Alternative Fuels Data Center. Fleet electric vehicle (EV) procurement requirements. US Department Of Energy https://afdc.energy.gov/laws/12758 (2021).

US Department of Energy. New and used clean vehicle tax credits. US DOE https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/new-and-used-clean-vehicle-tax-credits (2024).

US Department of Energy. DOE unveils new interactive map showcasing clean energy investment announcements nationwide. US DOE https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-unveils-new-interactive-map-showcasing-clean-energy-investment-announcements (2023).

State of California Department of Justice Office of the Attorney General. California will not waver in defending itself from federal overreach: Attorney General Bonta Sues Trump administration for attack on California’s clean vehicles program. State of California Department of Justice https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/california-will-not-waver-defending-itself-federal-overreach-attorney-general (2025).

California Air Resources Board. States that have adopted California’s vehicle regulations. California Air Resources Board https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/advanced-clean-cars-program/states-have-adopted-californias-vehicle-regulations (2024).

Plötz, P., Axsen, J., Funke, S. A. & Gnann, T. Designing car bans for sustainable transportation. Nat. Sustain. 2, 534–536 (2019).

International Council on Clean Transportation. Summary of the alignment of light-duty vehicle standards with ZEV targets. International Council on Clean Transportation https://theicct.org/viz-summary-of-the-alignment-of-light-duty-vehicle-standards-with-zev-targets/ (2024).

Peter, E. M. Exercise of enforcement discretion for the heavy-duty engine and vehicle omnibus and advanced clean fleets regulations. California Air Resources Board https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/2024-12/Omnibus_ACF_Enforcement_Discretion_112124.pdf (2024).

Drive to Zero. Memorandum of understanding on zero-emission medium- and heavy-duty vehicles. Drive to Zero https://globaldrivetozero.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Signed-Signatories-2024.9.12_38.pdf (2024).

Buckberg, E. Clean vehicle tax credit: the new industrial policy and its impact. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) https://siepr.stanford.edu/publications/policy-brief/clean-vehicle-tax-credit-new-industrial-policy-and-its-impact?utm_source=chatgpt.com (2023).

Zhao, J., Burke, A. F., Miller, M. R. & Fulton, L. M. Integrating market penetration and cost technologies (impact): procurement incentives on fuel cell electric truck adoption in California. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 94, 1266–1287 (2024).

Günther, A. et al. Psychological and contextual determinants of clean energy technology adoption. Nat. Rev. Clean Technol. 1, 547–565 (2025).

Debnath, R., Bardhan, R., Reiner, D. M. & Miller, J. R. Political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental dimensions of electric vehicle adoption in the United States: a social-media interaction analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 152, 111707 (2021).

Loureiro, S. M. C., Sarmento, E. M. & Le Bellego, G. The effect of corporate brand reputation on brand attachment and brand loyalty: automobile sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 4, 1360031 (2017).