Abstract

Controlled environment agriculture (CEA) enhances food resilience. However, CEA faces major challenges—high energy intensity and carbon footprints. Technological advancements are essential to reduce operational costs and promote CEA sustainability. This perspective article explores key technological innovations poised to enhance CEA sustainability, emphasizing the necessity of transdisciplinary approaches. We examine integrated decision-making frameworks informed by comprehensive life cycle analysis, distributed indoor agriculture, electricity demand flexibility, Digital Twins, and engineered microbiomes and plants optimized for CEA systems. For each area, we assess the current state of research, identify knowledge gaps, and outline future directions. For example, comprehensive life cycle analysis incorporates environmental, economic and social dimensions can inform both CEA decision making and community-scale circular economy planning; grid-integrated control strategies can enable CEA facilities to provide ancillary grid services, improving both economic viability and grid resilience. A holistic transdisciplinary approach is essential to drive a sustainable future for the CEA sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Overview

Traditional open-field agriculture production and food distribution are increasingly impacted by changing climate1, driven by such factors as arable land degradation, groundwater depletion, and extreme weather events. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)2 reports a global loss of 75 billion tons of soil from arable land each year due to soil erosion, nutrient leaching, spreading of soil contaminants, and desertification. In the United States (U.S.), 4.7 tons of topsoil are washed from every hectare of cropland per year, with a predicted increase of soil erosion from 8% to 21% by 20503. Major aquifers supplying 90% of water systems in the U.S. are rapidly being depleted, inflicting further harm on open-field agriculture4. Moreover, as natural disasters become more frequent, the food supply chain becomes even more vulnerable5,6. Globally, nearly one-third of food is wasted from farm to fork annually7,8,9,10. In the U.S., the retail industry, food services, and households generated 66.2 million tons of food waste in 201911, exacerbating food and nutrition insecurity challenges. We are seeking a new solution to boost crop productivity on limited arable land and ensure the resilience of food and nutrition security in the face of climate change while reducing food waste across agricultural production and food distribution.

Controlled environment agriculture (CEA) enhances food resilience through diversified sources, high productivity, water conservation, and protection against climate uncertainties, while promoting equitable food access for all communities. In CEA, crops grow under controlled conditions that include light (spectrum and intensity), temperature, and humidity. Crop yields (tons/hectare/year) in CEA are reported to range between 10 and 100 times higher than open-field agriculture12,13,14. Water use in CEA is typically about 4.5–16% of that from conventional farms per unit mass of produce15,16. CEA benefits communities by providing diversified food sources and the ability to shield food production from the uncertainties of climate conditions. CEA permits year-round crop growth with consistent quality and predictable output, shortens food miles), and provides social and health benefits to communities. This perspective article focuses on plant-based CEA production, rather than emerging novel food systems (e.g. cellular agriculture and microbial food17,18,19).

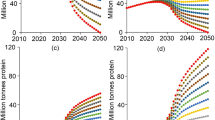

CEA is experiencing swift global growth, with each country tailoring it to meet its specific challenges. In China, CEA is driven by rising food demand, the need for pesticide-free produce, an aging agricultural workforce, heat stress, and food insecurity from natural disasters. Government policies support innovation in indoor agriculture and rural revitalization20. Singapore aims to meet 30% of its nutritional needs by 2030 through advanced CEA technology to enhance food production and security21. Canada’s vertical farming industry is driven by consumer preferences, environmental sustainability, and technological advancements, supported by government policies and research funding22. For developing countries such as Kenya, Nigeria, India, and Sri Lanka, CEA contributes to food security, safety and quality while promoting social equity and providing job opportunities23.

While fast-growing, CEA remains relatively immature as an industry, with many indoor farming companies having failed due to challenges in technology adoption, business model viability, and operational scalability24,25. CEA grapples with issues ranging from design and operation to workforce development. The energy-intensive nature and high carbon footprints of the industry26,27 make it difficult for CEA, especially vertical indoor farming, to be sustainable. Energy associated with artificial lighting, temperature control, and ventilation accounts for about 25% of the operating costs of large vertical farms in the United States. Energy is the second largest overhead cost in CEA, exceeded only by labor28,29,30. Carbon footprints were reported as 5.6–16.7 times and 2.3–3.3 times greater than that of open-field agriculture for indoor vertical farms and greenhouses, respectively31. Therefore, emerging technologies and advancements in fundamental science are essential for CEA to achieve significant resource efficiency32 and reduce operational costs while maximizing productivity33.

Current CEA technologies

Greenhouses and indoor vertical farms are among the most prominent CEA types, with greenhouses currently dominating the market34. Other systems—such as shipping container farms and hydroponic systems integrated in the built environment—also play an important role in CEA development and adoption. Greenhouses employ translucent structures that harness solar light, with energy-efficient light-emitting diode (LED) lighting as a supplement to support growth. However, external weather conditions can lead to high energy costs35,36. Indoor vertical farms, where crops grow hydroponically in stacked structures, are hermetically sealed and therefore require exclusive use of sole-sourced lighting systems. LED technology has empowered researchers to manipulate the specific spectrum and light intensity for crops; however, the significant capital investment and ongoing electricity costs—particularly at large scales—remain key challenges to economic viability. Over the past decade, there has been a surge in reported research investigating the effects of light environment and other key environmental conditions such as temperature and CO2 concentration, on crop yield, morphology, and nutritional quality37,38,39.

Nutritional quality of plant products is affected by the growing conditions such as temperature, light, and fertility management and measured by the concentrations of specific mineral elements and compounds like phenolics, vitamins, and antioxidants. Light was one of the main factors affecting metabolism and nutrient uptake of plants in CEA. Increasing light intensity can increase the concentration of nutritious phenolic compounds in many leafy greens40. Studies also showed that short-term supplemental lighting at the end of the production (EOP) can boost the nutritional quality and appearance of leafy greens41. However, current research, although extensive, is far from sufficient for optimizing production in CEA. The interaction between light spectrum and other key cardinal factors on crop performance remains largely untapped.

Soilless culture is a modern cultivation technology, which is used exclusively in CEA42. Hydroponics is a type of soilless culture and is often referred to as a solution culture where plant roots are immersed or partially immersed in a nutrient solution. The most widely used hydroponic systems are nutrient film technique (NFT) and deep-water culture (DWC) systems, while aeroponics is another variation of hydroponics, where plant roots are suspended in air and nutrient solution is misted onto plants roots intermittently. Generally, NFT and DWC are suitable for shallow root and short-term crops like leafy greens. NFT channels can vary greatly in size and length to suit different CEA production systems including vertical farms, while DWC is often used in greenhouses due to its heavy weight of solutions. Soilless substrate culture uses solid growing medium to anchor plant roots and is often used for long-term crops such as fruit vegetables and berry crops. In soilless substrate culture, many types of substrates such as coco coir, rockwool, etc. are used. Proper selection of growing substrates not only influences plant performance but also production costs. The key benefits of soilless substrate culture and hydroponics include the elimination of soil-borne diseases, prevention of soil fertility issues and salinity, and improved control and monitoring of nutrient levels. Over the past 40 years, advancements have focused on developing growing media with optimal physical, hydraulic, and chemical properties43, standardizing substrate analysis, improving plant nutrition and automated irrigation systems42, and developing various hydroponic systems44. Articles provide introductory reviews of CEA growing methods, artificial lighting, nutrition management, sensing technologies, automation, and substrates45,46,47,48.

This perspective article explores key technological innovations poised to enhance CEA sustainability, emphasizing the necessity of transdisciplinary approaches. We examine integrated decision-making frameworks informed by comprehensive life cycle analysis, distributed indoor agriculture, electricity demand flexibility, Digital Twins, and engineered microbiomes and plants optimized for CEA systems. We also envision the role of CEA in sustainable and resilient communities and propose a transdisciplinary education approach for future CEA workforce development. The selection of the technological innovations was based on expert engineering judgment aiming at addressing major challenges in CEA.

Decision-making tools and emerging technologies in CEA

Integrated decision making based on life cycle analysis

Life cycle analysis guides decision making and policy for CEA (Fig. 1). Early-stage assessment across the life cycle of CEA is essential to support integrated decision-making and minimize costs49. Life cycle analysis can be used to optimize key CEA design factors50, such as CEA size, location, envelope design, and heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, and guide research and development to identify critical technologies for the CEA industry51. However, there is a lack of comprehensive life cycle analysis, evaluating potential environmental, economic and social impacts of the new CEA designs at different settings.

This includes five key components as shown. a Crop production. b Post-processing and food packaging. c Transportation. d Food distribution. e End-use for consumers. Distributing food through retail community outlets is the most common practice. In the meantime, subscription services through e-delivery can be a better approach to reduce food waste in distribution.

Most existing CEA life cycle analyses, such as life cycle assessment (LCA)52, evaluate carbon footprints of resource use (e.g. fertilizer, energy, water)26,31,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 or both economic and environmental performance49,60,61,–62 through case studies. Linking LCA to a bioeconomic model has been proposed for analyzing area-based farming policy63. Most studies represent current CEA technologies and have well-defined CEA in terms of size, system, and location. Thus, these studies are limited to comparing the current CEA prototypes to open-field agriculture but have limited impacts on supporting new designs and decision making for CEA.

Advocates for an ecological-economic approach that considers the environmental dimensions of meeting human needs highlight the need for a comprehensive approach to LCA that integrates economic, social, and environmental aspects64. Weidema65 emphasizes the importance of integrating social aspects into LCA, while Arodudu et al.66 suggests the use of tools and methodologies to bridge methodological gaps in LCA application to agro-bioenergy systems and to integrate agronomic options and life cycle thinking approaches.

LCA can be further applied to fulfill the CEA circular economy, supporting the development of sustainable strategies for CEA industry, reduction in waste and cost, and enhancement of resource efficiency at community scales. The reuse and recycling opportunities include waste heat utilization, CO2 supply through co-location, water reuse and reclamation of nutrients from water treatment plants, and recycling of growing media and food packages67. Various case studies report their utilization of waste heat from combined heat and power plants68,69,70, data centers71,72,73,74, and plant factories75. Indoor farms reuse low-quality energy, in the form of warm water or air in a temperature range of 30–47 °C. Recirculating irrigation water has the potential to reduce water consumption by 20–40% and fertilizer costs by 40–50%76. Water reuse for crop growth conserves freshwater, promotes water circularity, and reduces the total need for chemical fertilizers77. Defining the water treatment and nutrient reclamation requirements for crop growth is an important research question for CEA78. Potential contamination risks such as microbial pathogens and chemical content should also be considered for irrigation79. Although waste resources may be limited by location, it is possible to create a CEA ecosystem through strategic planning of businesses and infrastructure within communities. The evaluation of the planning scenarios can be based on comprehensive life cycle analysis, integrating economic, social, and environmental aspects.

Distributed indoor agriculture

Distributed indoor agriculture (DIA) systems within buildings can support crop cultivation using hydroponic techniques—such as NFT and DWC, as discussed in Section “Current CEA technologies”. Each DIA system (Fig. 2) is equipped with integrated hardware and software solutions, including controls of grow lights and irrigation, monitoring of crop growth, and diagnosis of issues related to crop health and system operation.

Indoor living walls, a foundational prototype of the DIA system, have gained popularity by bringing nature indoors80, and indoor plants have become highly desirable with the rise of remote work81. Studies show measurable benefits of these systems on occupants’ thermal comfort and building cooling load reduction82,83,84. With living walls, the cooling setpoint can be increased by 0.9 K and still satisfy thermal comfort needs for the majority of the occupants83. In an experimental study of a hall with a floor area of 520 ft2 that was not equipped with air conditioning, an average temperature reduction of 4 K was observed85. In addition, indoor plants demonstrate the capability to improve indoor air quality86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93, productivity and creativity94, while reducing noise levels95, the negative effects of visual glare96,97, stresses98, and discomfort symptoms99,100. Plant leaves and their microbes purify indoor air through phytoremediation, absorbing pollutants via leaf stomata and degrading them through plant metabolism101. Plant elements like leaves and twigs reflect, scatter, and attenuate sound through mechanical vibration. A study of a 2.4 m2 living wall in a space with floor area of 19.6 m2 found a weighted sound reduction index of 15 dB and a weighted sound absorption coefficient of 0.4095. Moreover, people were more productive (12% quicker reaction time on a computer task) and less stressed (systolic blood pressure readings lowered by one to four units)94.

Can DIA systems be a potential integrated solution to food resilience, better indoor environmental quality, energy efficiency, and well-being? Broadly speaking, there are four broad markets to target (1) offices; (2) institutions; (3) hospitality; and (4) residential buildings. Dedicating 1% of floor area identified in the Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS)102 and Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS)103 to growing lettuce in existing buildings has a potential yield of 5.1–70.4 kg fresh weight lettuce per capita per growing cycle (about four weeks) based on the reported lettuce yield (6.9–95 kg fresh weight) per growing floor area (m2)104. This potential yield is much higher than the U.S. per capita consumption of fresh romaine and leaf lettuce (5.8 kg) in 2022105. DIA and CEA are distinct and potentially competitive models for food production, but their co-existence can provide mutual benefits. Successful DIA demonstrations promote mass-market acceptance of hydroponically grown foods through social impacts, public education, and easy accessibility of technology.

CEA electricity demand flexibility

Connecting CEA with microgrids can not only reduce CEA’s carbon footprint but also contribute to stabilizing microgrids through demand response and frequency control. Electricity demand from lights and HVAC systems and the associated carbon footprints have been significant for indoor vertical farms. CEA can be strategically co-located in areas with existing microgrid infrastructure or where dynamic electricity pricing creates opportunities for cost savings and load flexibility. Shifting LED lights from continuous to intermittent operation was implemented to reduce operational costs by responding to daily electricity price fluctuations106,107.

CEA can serve as a demand-side dispatchable load for microgrids to reduce the volatility of renewable energy resources (Fig. 3). Stable operation of electric systems requires frequency regulation; providing frequency regulation from demand side resources mitigates technical, economic, and political challenges108. Existing studies have tested the feasibility of using HVAC equipment as dispatchable loads on the demand side109,110,111. Due to the high volatility of such distributed energy resources (DERs) as wind turbines, photovoltaics, and hydroelectricity, balancing renewable energy generation and demands for microgrids is expensive in comparison to traditional power grid frequency regulation. CEA can potentially serve as an important dispatchable load on the demand side if crops can tolerate certain lighting fluctuations. Dynamic environmental variations trigger plants’ physiological response, yet they can maintain diurnal leaf carbon gain in comparison with plant growth in constant environments112. Further research is needed on how variations of LED light and temperature induced by dynamic variations in price signals from microgrids affect crop yield and quality.

a Both microgrid and CEA are considered as modern infrastructures in future communities. b CEA as dispatchable loads for ancillary services of utility companies through demand response and frequency control. c Future research direction on the impacts of the variations of temperature and lighting intensities in response to volatility of renewable energy systems on crop yield and quality.

Digital twins in CEA

A CEA Digital Twin (DT) framework integrates computer vision, edge computing, AI-enabled predictive analytics, and optimal control technologies (Fig. 4), forecasting and optimizing the behavior of the physical asset (crops) and resource management. DT frameworks have been explored in various contexts in CEA, including monitoring DT for tracking subsystems113, predictive DT for optimizing production and resource use efficiency114,115, supply chain DT to optimize agrifood supply chain116, DT for aquaponics production facilities117, and visualization DT118.

The DT framework integrates computer vision-based crop monitoring, edge and cloud data processing, AI-driven climate and growth prediction models, and Bayesian optimization for dynamic climate control. Real-time data acquisition and feedback enable continuous model calibration, facilitating adaptive resource management, crop growth forecasting, and energy optimization under variable environmental conditions.

Computer vision is the key component to acquire crop growth information and provide feedback to update crop model parameters for resource optimization119,120,121,122. Studies have focused on developing growth forecasting based on early-stage growth images using spatial transformation123 and spatial-temporal attention mechanisms124. State-of-the-art algorithms, such as YOLO series119, Mask-RCNN125, and Deepabv3+126, have been employed for growth monitoring, yield prediction, and spacing optimization. However, image-based systems encounter limitations. Occlusions and complex canopies create challenges in developing automation solutions for plant monitoring. Thus, advanced algorithms and approaches such as 3D reconstruction (via Neural Radiance Fields127, and Gaussian Splatting), and geometric DT128,129 are needed to enhance crop growth monitoring solutions for CEA. Furthermore, multispectral and hyperspectral imaging systems have been deployed to determine the nutrient concentration in CEA produce so that growers can develop mitigation strategies before deficiency symptoms arise130,131,132,133. However, the detection accuracy is limited due to the extremely complex workspace. Most deep learning-based networks require image normalization before images are input to the network, reducing the feature details and decreasing detection accuracy.

Intelligent climate controllers, driven by microclimate data, have advanced optimal energy use management. AI algorithms, such as reinforcement learning have been explored to optimize energy and water use in greenhouses134. A wide range of control algorithms has been explored to optimize variables such as light intensity, air velocity, shade curtain, vapor pressure deficits, and CO2 levels to minimize energy costs135,136,137,138. In addition, DT requests vast amounts of data, subject to issues like inaccuracies and cyberattacks. Blockchain has been applied in CEA applications139,140,141 to enhance information security.

A major obstacle to optimal outcomes in CEA lies in real-time crops’ response to environmental conditions and thus decoupled crop growth and resource optimization142. Although studies have been conducted for optimal resource allocation under fixed microclimate conditions143,144,145, forecasting growth based on training data from fixed conditions may limit its applicability in real CEA environments with dynamic climate conditions. A real-time feedback DT system must assess forecast accuracy and adjust model parameters, leading to efficient decision support for growers to optimize production and energy use.

Microbiome management in CEA

Growing plants in hydroponics rather than soil dramatically changes the challenges. One important facet of plant physiology and plant health is the contribution of the plant microbiota, which represents a largely untapped opportunity146. Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) reside in or around plants and can act as biostimulants, biofertilizers, and bioprotectants147. Plant-associated beneficial microorganisms – e.g., bacteria and fungi – promote growth, nutrient uptake, stress tolerance, and resistance to pathogens148. However, many plant-growth-promoting microbes found in soil cannot make the transition to hydroponic environments149. Moreover, many PGPB products are developed for field application and have not been optimized for specific conditions of CEA which include dense cropping of specifically optimized crops, controlled water and climate systems, and integrated sensors and controllers. While hydroponics has a range of advantages over soil-based cultivation, one of the disadvantages is the fast spread of infectious diseases due to the recirculating nature of nutrient solution in the whole system. In such a case, PGPB may offer a unique solution in hydroponic systems by sensing and preventing pathogen outbreaks, improving access to nutrients and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses and increasing crop yield. To date, there are reports that PGPB promotes plant growth in various hydroponic systems. For example, Pseudomonas psychrotolerans IALR632 increased shoot and root growth of green Oakleaf lettuce grown in nutrient film technique (NFT) in the greenhouse, indoor vertical NFT, and a deep-water culture system150.

Another group of beneficial microbial-based microorganisms is arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). AMF is known to form AMF-host plant symbiosis with more than 80% of plant species151. The primary positive impacts of AMF symbiosis are increasing availability of both macro- and micro-nutrients, increasing photosynthetic rate, and enhancing tolerance to stressful conditions through augmentation of antioxidant defense system. A recent study by Caser et al.152 for saffron in soilless systems in a glasshouse indicated that inoculation with one AMF species (Rhizophagus intraradices) or a mixture of R. intraradices and Funneliformis mosseae increased spice quality as evidenced by a superior content of several health-promoting compounds (polyphenols, anthocyanins, vitamin C, and antioxidant activity) in one cycle of growth in soilless systems compared to open field production, while spice yield was similar to that of open field. These results improve our understanding of microbial communities in soilless media. Nevertheless, such information is still limited, and future studies are needed to fully understand and optimize the benefits of microbes under controlled environments. There are also advanced opportunities for genetically engineering these communities for enhanced properties for the plant; better association with the plant and survival/persistence in the hydroponic environment, and for coupling to CEA control systems by reporting on water, microbiome and plant health through expression of environmentally-sensitive fluorescent and volatile organic reporters153. A growing body of literature has focused on defining, engineering and using laboratory evolution to evolve such synthetic communities for plants in both soil and artificial conditions154,155 —a focused effort to co-design microbial communities supporting optimized plants and coupling with control systems.

Engineered plants for CEA

Transgenic crops have revolutionized the scale and nature of agriculture; however, such efforts are largely focused on addressing producer-facing challenges associated with traditional methods of growing crops in fields (i.e., herbicide tolerance, insect resistance). Crops grown in CEAs may shift the focus of engineering efforts towards other consumer-facing traits that may benefit from indoor growth. Growing plants that are engineered to improve human health through the enhanced delivery of key phytonutrients has been a key pillar in plant engineering efforts156,157. Complex natural products ranging from edible health compounds to plant-derived pharmaceuticals may be developed as interesting targets for transgenic plants grown in CEA158,159,160,161. Nutrient management in CEA can significantly enhance the vitamin content in crops through precise control and optimization of nutrient solutions that meet the specific requirements of various plant species and growth stages. This targeted approach enables growers to enhance the uptake of specific nutrients that are precursors to vitamins, leading to increased vitamin content in crops162. One regulatory challenge of field-grown crops is the concern of outcrossing of transgenes; thus, the large-scale indoor growth of transgenic crops in CEA may open the door to safer implementation and growth of engineered plants, which may also expand the range of traits that could be pursued.

Optimizing and redesigning plant architecture within confined space limitations has the opportunity to dramatically enhance yield of indoor-grown crops. Kwon et al. leveraged CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to target and manipulate the physiology of tomato plants by engineering highly compact and rapid flowering plants163. The optimization of plant stature may enable the custom development of CEAs that are more space efficient and enable higher yield per footprint. The implications of such efforts are aligned with the challenges associated with growing plants indoors with limited space.

The role of CEA in communities

Community and CEA

CEA benefits communities from shortened food miles and better food quality to opportunities for education and employment (Fig. 5). Community-based CEA inherits demonstrated benefits from community gardens but offers a year-long growing environment and the opportunity to revitalize communities by repurposing abandoned warehouses. This industry offers employment opportunities for community members with physical or mental disabilities164 and educational opportunities for next generations. The involvements of community gardens increase students’ choice of healthy diet and their number of weekly physical activities165. In less favorable climate states, indoor farms enable school-age children to have year-round access to fresh salads. Akin to traditional community gardens, community-based CEA farms provide shared venues for community members to exchange culture and food knowledge and cultivating healthy social environments166,167. Studies show that the social interactions and quality of community gardens benefit elders’ well-being168.

CEA can be integrated with building design and operation to provide food security through a shorter and more resilient supply chain and enhance environmental quality. Resources such as heat, CO2, reclaimed nutrients and water required in CEA operation can be supplied with byproducts from combined heat and power, data center, factory, or water treatment plant.

CEA has strong synergy with urban agriculture initiatives, offering potential benefits in food security, sustainability, and local economic development. City-level programs such as Grow Boston and FarmPhilly in Philadelphia actively support CEA innovations and local food access. However, implementing CEA in dense urban environments introduces critical challenges, including prohibitive land costs, limited available space, and existing infrastructure constraints. Community-based CEA must therefore take into account not only logistics, crop selection, and resource efficiency but also the spatial and economic feasibility of deployment. These systems can align with urban planning frameworks such as the 15-min neighborhood concept, which emphasizes localized access to services169. Large-scale community modeling tools—integrating food demand, carbon emissions, energy flows, and socioeconomic impacts—can inform urban-scale CEA design and guide implementation strategies.

CEA education and workforce development

A holistic transdisciplinary education approach across agriculture, architecture, engineering, and business should be taken to design a structured curriculum or technical training for CEA and associated courses for higher education. The future success of CEA largely depends on training diverse workers fluent in engineering, plant science, and business management and skilled in working in transdisciplinary, collaborative environments. However, such advanced technological training for the future CEA workforce170,171,172 is rare in the US and other countries173,174, because such training is beyond traditional agriculture production and management and cannot be completed by a single traditional program such as plant science or horticulture170.

Engaging K-12 educators in CEA scientific research as professional development is essential to cultivate the interests of the next generations in CEA or STEM in general. The “Train the Trainers” model has proved that teachers’ professional development boosts students’ achievement175. Translating scientific research experience and knowledge in CEA into K-12 classroom education requires rapport with the K-12 education community on shared learning experience and scientists in higher education on technical skill training for teachers. Teachers have the opportunity to bring students hands-on experiences in school greenhouses and indoor growing facilities based on state-of-the-art research in CEA.

Conclusion

CEA represents many opportunities for future indoor agriculture and provides partial potential solutions to such grand challenges as food and nutrition insecurity. CEA allows crops to grow year-round under uncertain climate conditions, shortens food miles and associated food waste through transportation, and offers social and health benefits to communities. Innovative technologies are essential to make CEA sustainable. From a carbon footprint perspective, a significant reduction in carbon emissions of CEA operation is necessary. Technologies for collecting and distributing natural solar light in buildings can potentially reduce the electricity demand of intensive LED light through novel architectural designs. Plant photosynthesis efficiency176 can be improved through engineered plants and microbiome management, which may allow plants to grow in a relatively dark environment and reduce lighting demands. Robotics in CEA or agriculture in general may replace repetitive works such as pruning, planting and harvesting and require that the workers in agriculture have advanced skills. While CEA offers benefits, both open-field agriculture and CEA can complement each other, with CEA focusing on high-value and fresh produce, particularly in regions with a less favorable climate, while open field agriculture provides high energy demanding staple crops with relatively long lifespans. A holistic transdisciplinary approach is essential in both research and education to achieve sustainable, resilient, and scalable future CEA and would make a critical contribution and transform the current CEA industry.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

EPA. Climate impacts on agriculture and food supply. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/climate-change-impacts-agriculture-and-food-supply (2025).

FAO. Global Soil Partnership endorses guidelines on sustainable soil management. Available from: https://www.fao.org/global-soil-partnership/resources/highlights/detail/en/c/416516/ (2017).

Shojaeezadeh, S. A. et al. Soil erosion in the United States: present and future (2020–2050). CATENA 242, 108074 (2024).

Rojanasakul, M. et al. America is using up its groundwater like there’s no tomorrow (The New York Times, 2023).

FAO. The impact of disasters and crises 2021 on agriculture and food security (FAO, 2021).

Murphy, K. & Schlegelmilch, J. Secure the food supply chain before the next disaster strikes. Available from: https://thehill.com/opinion/white-house/3655657-secure-the-food-supply-chain-before-the-next-disaster-strikes/ (2022).

Borens, M. et al. Reducing food loss: what grocery retailers and manufacturers can do (McKinsey & Company, 2022).

Weinswig, D. Overcoming the food-waste challenge: improving profit wile doing good (Coresight Research, 2022).

Houghton, T. Reducing food waste across the supply chain: statistics & strategies (Center for Nutrition Studies, 2021).

Labs, W., Food loss & waste: it’s everywhere in the supply chain (Food Engineering, 2022).

United States Environmental Protection Agency [US-EPA]. 2019 Wasted Food Report: Estimates of generation and management of wasted food in the United States in 2019 April 2023. EPA 530-R-23-005 (2023).

Nederhoff, E. & Houter, B. Improving energy efficiency in greenhouse vegetable production (Final report on project SFF 03/158), (Horticulture New Zealand, Wellington, 2007).

Avgoustaki, D. D. & Xydis, G. Chapter One - How energy innovation in indoor vertical farming can improve food security, sustainability, and food safety? In Advances in food security and sustainability (ed. Cohen, M. J.) 1–51 (Elsevier, 2020). 1-51.

Padmanabhan, P., Cheema, A. & Paliyath, G. Solanaceous fruits including tomato, eggplant, and peppers. In Encyclopedia of food and health (eds Caballero, B. Finglas, P. M. & Toldrá, F.) 24–32 (Academic Press, 2016).

Barbosa, G. L. et al. Comparison of land, water, and energy requirements of lettuce grown using hydroponic vs. conventional agricultural methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12 (2015).

Pohl, P. I. B. et al. Systems assessment of water savings impact of controlled environment agriculture (CEA) utilizing wirelessly networked Sense Decide Act Communicate (SDAC) systems. SAND2005-0759, United States (Sandia National Laboratories, 2005).

Tzachor, A., Richards, C. E. & Holt, L. Future foods for risk-resilient diets. Nat. Food 2, 326–329 (2021).

Parodi, A. et al. The potential of future foods for sustainable and healthy diets. Nat. Sustain. 1, 782–789 (2018).

Graham, A. E. & Ledesma-Amaro, R. The microbial food revolution. Nat. Commun. 14, 2231 (2023).

The Economist. China is obsessed with food security. Climate change will challenge it. https://www.economist.com/china/2023/07/13/china-is-obsessed-with-food-security-climate-change-will-challenge-it (2023).

Tatum, M. Inside Singapore’s huge bet on vertical farming (MIT Technology Review, 2020).

Coleman, M., Graham, L. & Schatz, J. What is driving vertical farming in Canada? Available from: https://www.bennettjones.com/Blogs-Section/Whats-Driving-Vertical-Farming-in-Canada (2023).

Halliday, J., Kaufmann, R.V. & Herath, K. V. An assessment of Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) in low- and lower-middle income countries in Asia and Africa, and its potential contribution to sustainable development. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/117234 (2021).

Grower, P. Indoor Ag-Con: a plea for CEA advocacy, 6 reasons indoor farms fail. Available from: https://www.producegrower.com/news/indoor-ag-con-2022-wrap/ (2022).

FastCompany. The vertical farming bubble is finally popping. Available from: https://www.fastcompany.com/90824702/vertical-farming-failing-profitable-appharvest-aerofarms-bowery (2023).

Engler, N. & Krarti, M. Review of energy efficiency in controlled environment agriculture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 141, 110786 (2021).

Iddio, E. et al. Energy efficient operation and modeling for greenhouses: a literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 117, 109480 (2020).

Taki, M., Rohani, A. & Rahmati-Joneidabad, M. Solar thermal simulation and applications in greenhouse. Inf. Process. Agric. 5, 83–113 (2018).

Agrilyst. State of indoor farming. https://www.bayer.com/sites/default/files/stateofindoorfarming-report-2017.pdf (2017).

Valle de Souza, S., Peterson, H. C. & Seong, J. Chapter 14 - Emerging economics and profitability of PFALs. In Plant Factory Basics, Applications and Advances, (eds, Kozai, T., Niu, G. & Masabni, J.) 251–270 (Academic Press, 2022).

Blom, T. et al. The embodied carbon emissions of lettuce production in vertical farming, greenhouse horticulture, and open-field farming in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 377, 134443 (2022).

Kozai, T. et al. Chapter 12 - Productivity: definition and application. In Plant factory basics, applications and advances, (eds Kozai, T., Niu, G. & Masabni, J.) 197–216 (Academic Press, 2022).

Altland, J. et al. Multi-agency collaboration addressing challenges in controlled environment agriculture (University of Toledo, 2021).

StraitsResearch. Indoor farming market. Available from: https://straitsresearch.com/report/indoor-farming-market (2023).

Thipe, E. L. et al. Greenhouse technology for agriculture under arid conditions. In Sustainable agriculture reviews (ed. Lichtfouse, E.) 37–55 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Nasrollahi, H. et al. The greenhouse technology in different climate conditions: a comprehensive energy-saving analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 47, 101455 (2021).

Boros, I. F. et al. Effects of LED lighting environments on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) in PFAL systems – a review. Sci. Horticulturae 321, 112351 (2023).

Mitchell, C. A. History of controlled environment horticulture: indoor farming and its key technologies. HortScience 57, 247–256 (2022).

Sipos, L. et al. Optimization of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) production in LED light environments – a review. Sci. Horticulturae 289, 110486 (2021).

Dou, H. et al. Responses of sweet basil to different daily light integrals in photosynthesis, morphology, yield, and nutritional quality. HortScience horts 53, 496–503 (2018).

Hooks, T. et al. Short-term pre-harvest supplemental lighting with different light emitting diodes improves greenhouse lettuce quality. Horticulturae 8, 435 (2022).

Savvas, D. & Gruda, N. Application of soilless culture technologies in the modern greenhouse industry – a review. Eur. J. Horticultural Sci. 83, 280–293 (2018).

Gruda, N. S. Advances in soilless culture and growing media in today’s horticulture—an editorial. Agronomy 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12112773 (2022).

Velazquez-Gonzalez, R. S. et al. A Review on Hydroponics and the Technologies Associated for Medium- and Small-Scale Operations. Agriculture, 2022. 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12050646.

Oh, S. & Lu, C. Vertical farming - smart urban agriculture for enhancing resilience and sustainability in food security. J. Horticultural Sci. Biotechnol. 98, 133–140 (2023).

Sowmya, C. et al. Recent developments and inventive approaches in vertical farming. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8, 2024 (2024).

Hati, A. J. & Singh, R. R. Smart indoor farms: leveraging technological advancements to power a sustainable agricultural revolution. AgriEngineering 3, 728–767 (2021).

Ragaveena, S., Shirly Edward, A. & Surendran, U. Smart controlled environment agriculture methods: a holistic review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio Technol. 20, 887–913 (2021).

Li, L. et al. A decision support framework for the design and operation of sustainable urban farming systems. J. Clean. Prod. 268, 121928 (2020).

Wright, H. C. et al. Space controlled environment agriculture offers pathways to improve the sustainability of controlled environmental agriculture on Earth. Nat. Food 4, 648–653 (2023).

Notarnicola, B. et al. The role of life cycle assessment in supporting sustainable agri-food systems: a review of the challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 140, 399–409 (2017).

Curran, M. A. Board based environmental life cycle assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27, 430–436 (1993).

Kikuchi, Y. et al. Environmental and resource use analysis of plant factories with energy technology options: a case study in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 186, 703–717 (2018).

Maucieri, C. et al. Life cycle assessment of a micro aquaponic system for educational purposes built using recovered material. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 3119–3127 (2018).

Piezer, K. et al. Ecological network analysis of growing tomatoes in an urban rooftop greenhouse. Sci. Total Environ. 651, 1495–1504 (2019).

Sanjuan-Delmás, D. et al. Environmental assessment of an integrated rooftop greenhouse for food production in cities. J. Clean. Prod. 177, 326–337 (2018).

Benis, K., Reinhart, C. & Ferrão, P. Building-integrated agriculture (BIA) in urban contexts: testing a simulation-based decision support workflow (Building Simulation, San Francisco, USA, 2017).

Stoessel, F. et al. Life cycle inventory and carbon and water FoodPrint of fruits and vegetables: application to a Swiss retailer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3253–3262 (2012).

Parkes, M. G. et al. Life cycle assessment of microgreen production: effects of indoor vertical farm management on yield and environmental performance. Sci. Rep. 13, 11324 (2023).

Nicholson, C. F. et al. An economic and environmental comparison of conventional and controlled environment agriculture (CEA) Supply Chains for Leaf Lettuce to US Cities. In Food supply chains in cities: modern tools for circularity and sustainability (Aktas, E. & Bourlakis, M.) 33–68 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Sanyé-Mengual, E. et al. Techniques and crops for efficient rooftop gardens in Bologna, Italy. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 1477–1488 (2015).

Sanyé-Mengual, E. et al. An environmental and economic life cycle assessment of rooftop greenhouse (RTG) implementation in Barcelona, Spain. Assessing new forms of urban agriculture from the greenhouse structure to the final product level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 20, 350–366 (2015).

Nakashima, T. & Ishikawa, S. Linking life cycle assessment to bioeconomic modelling with positive mathematical programming: an alternative approach to calibration. J. Clean. Prod. 167, 875–884 (2017).

Pelletier, N. & Tyedmers, P. An ecological economic critique of the use of market information in life cycle assessment research. J. Ind. Ecol. 15, 342–354 (2011).

Weidema, B. P. The integration of economic and social aspects in life cycle impact assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 11, 89–96 (2006).

Arodudu, O. et al. Towards a more holistic sustainability assessment framework for agro-bioenergy systems — a review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 62, 61–75 (2017).

Cowan, N. et al. CEA systems: the means to achieve future food security and environmental sustainability? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6, 2022 (2022).

Katsaprakakis, D. A. et al. Feasibility for the introduction of decentralised combined heat and power plants in agricultural processes. A case study for the heating of algae cultivation ponds. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 53, 102757 (2022).

González-Briones, A. et al. Reuse of waste energy from power plants in greenhouses through MAS-based architecture. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 6170718 (2018).

Yu, M. G. & Nam, Y. Feasibility assessment of using power plant waste heat in large scale horticulture facility energy supply systems. Energies 9, 112 (2016).

Robinson, A. This Canadian company is planning to grow tomatoes using heat from computers. Available from: https://www.corporateknights.com/category-food/this-company-growing-food-using-heat-from-data-centres/ (2023).

Kommun, B. The 300 square meter smart greenhouse. The greenhouse is powered by waste heat. Available from: https://boden.se/nyheter/2021/det-300-kvadratmeter-smarta-vaxthuset-vaxthuset-drivs-pa-spillvarme (2021).

Ljungqvist, H. M. et al. Data center heated greenhouses, a matter for enhanced food self-sufficiency in sub-arctic regions. Energy 215, 119169 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Complementary waste heat utilization from data center to ecological farm: a technical, economic and environmental perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 435, 140495 (2024).

Thomas, Y., Wang, L. & Denzer, A. Energy savings analysis of a greenhouse heated by waste heat. In Proceedings of building simulation. (IBPSA, 2017).

Institute, R. I. Best practices guide water circularity for controlled environment agriculture operations (Resource Innovation Institute, 2023).

Rodda, N. et al. Use of domestic greywater for small-scale irrigation of food crops: effects on plants and soil. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C. 36, 1051–1062 (2011).

Helmecke, M., Fries, E. & Schulte, C. Regulating water reuse for agricultural irrigation: risks related to organic micro-contaminants. Environ. Sci. Eur. 32, 4 (2020).

Busgang, A. et al. Quantitative microbial risk analysis for various bacterial exposure scenarios involving greywater reuse for irrigation. Water 10, 413 (2018).

Strauss, A. Bringing the outside inside your home (The New York Times, 2020.

Chatakul, P. & Janpathompong, S. Interior plants: trends, species, and their benefits. Build. Environ. 222, 109325 (2022).

Wang, L., Iddio, E. & Ewers, B. Introductory overview: Evapotranspiration (ET) models for controlled environment agriculture (CEA). Comput. Electron. Agric. 190, 106447 (2021).

Iddio, E. et al. The effects of indoor living walls on occupant thermal comfort in office buildings. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 31, 398–414 (2025).

Wang, L. & Witte, M. J. Integrating building energy simulation with a machine learning algorithm for evaluating indoor living walls’ impacts on cooling energy use in commercial buildings. Energy Build. 272, 112322 (2022).

Fernandez-Canero, R., Urrestarazu, L. Perez & Franco Salas, A. Assessment of the cooling potential of an indoor living wall using different substrates in a warm climate. Indoor Built Environ. 21, 642–650 (2011).

Wetzel, T. A. & Doucette, W. J. Plant leaves as indoor air passive samplers for volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Chemosphere 122, 32–37 (2015).

Wild, E. et al. Direct observation of organic contaminant uptake, storage, and metabolism within plant roots. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 3695–3702 (2005).

Rodgers, K., Handy, R. & Hutzel, W. Indoor air quality improvements using Biofiltration in a highly efficient residential home. J. Green. Build. 8, 22–27 (2013).

Zhang, L., Routsong, R. & Strand, S. E. Greatly enhanced removal of volatile organic carcinogens by a genetically modified houseplant, Pothos Ivy (Epipremnum aureum) expressing the mammalian cytochrome P450 2e1 gene. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 325–331 (2019).

Wolverton, B. C., McDonald, R. C. & Watkins, E. A. Foliage plants for removing indoor air pollutants from energy-efficient homes. Econ. Bot. 38, 224–228 (1984).

Torpy, F. et al. Testing the single-pass VOC removal efficiency of an active green wall using methyl ethyl ketone (MEK). Air Qual. Atmos. Health 11, 163–170 (2018).

Pettit, T., Irga, P. J. & Torpy, F. R. The in situ pilot-scale phytoremediation of airborne VOCs and particulate matter with an active green wall. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 12, 33–44 (2019).

Irga, P. J., Pettit, T. J. & Torpy, F. R. The phytoremediation of indoor air pollution: a review on the technology development from the potted plant through to functional green wall biofilters. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio Technol. 17, 395–415 (2018).

Lohr, V. I., Pearson-Mims, C. H. & Goodwin, G. K. Interior plants may improve worker productivity and reduce stress in a windowless environment. J. Environ. Horticulture 14, 97–100 (1996).

Azkorra, Z. et al. Evaluation of green walls as a passive acoustic insulation system for buildings. Appl. Acoust. 89, 46–56 (2015).

Hellinga, H. & de Bruin-Hordijk, G. Assessment of daylight and view quality: a field study in office buildings, 326–331 (International Commission on Illumination, 2010).

Kristanto, L., Ekasiwi, S. & Dinapradipta, A. Implementing vertical greenery on office facade opening to improve indoor light quality. Architecture Built Environ. 49, 43–52 (2022).

Lee, S. Why indoor plants make you feel better (NBC news, 2017).

Tove, F. The effect of interior planting on health and discomfort among workers and school children. HortTechnology 10, 46–52 (2000).

Lohr, V. I. & Pearson-Mims, C. H. Physical discomfort may be reduced in the presence of interior plants. HortTechnology 10, 53–58 (2000).

Han, Y. et al. Plant-based remediation of air pollution: a review. J. Environ. Manag. 301, 113860 (2022).

EIA. 2018 Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey final results. Available from: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/ (2021).

EIA. 2020 Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS) Survey Data. Available from: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2020/ (2023).

Touliatos, D., Dodd, I. C. & McAinsh, M. Vertical farming increases lettuce yield per unit area compared to conventional horizontal hydroponics. Food Energy Secur. 5, 184–191 (2016).

Statista. Per capita consumption of fresh lettuce (romaine and leaf) in the United States from 2000 to 2022. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/257322/per-capita-consumption-of-fresh-lettuce-romaine-and-leaf-in-the-us/#:~:text=The%20timeline%20shows%20the%20per,approximately%2012.7%20pounds%20in%202022 (2023).

Avgoustaki, D. D. & Xydis, G. Energy cost reduction by shifting electricity demand in indoor vertical farms with artificial lighting. Biosyst. Eng. 211, 219–229 (2021).

Penuela, J. et al. The indoor agriculture industry: a promising player in demand response services. Appl. Energy 372, 123756 (2024).

Su, L. & Norford, L. K. Demonstration of HVAC chiller control for power grid frequency regulation—Part 1: controller development and experimental results. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 21, 1134–1142 (2015).

Su, L. & Norford, L. K. Demonstration of HVAC chiller control for power grid frequency regulation—Part 2: discussion of results and considerations for broader deployment. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 21, 1143–1153 (2015).

Wang, H. & Wang, S. The impact of providing frequency regulation service to power grids on indoor environment control and dedicated test signals for buildings. Build. Environ. 183, 107217 (2020).

Cai, J. & Braun, J. E. Laboratory-based assessment of HVAC equipment for power grid frequency regulation: methods, regulation performance, economics, indoor comfort and energy efficiency. Energy Build. 185, 148–161 (2019).

Kaiser, E. et al. Vertical farming goes dynamic: optimizing resource use efficiency, product quality, and energy costs. Front. Sci., 2 (2024).

González, J. P., Sanchez-Londoño, D. & Barbieri, G. A monitoring digital twin for services of controlled environment agriculture. IFAC-PapersOnLine 55, 85–90 (2022).

Chaux, J. D., Sanchez-Londono, D. & Barbieri, G. A digital twin architecture to optimize productivity within controlled environment agriculture. Appl. Sci. 11, 8875 (2021).

Zahid, A. & Ojo, M. Digital twin framework for optimizing crop growth and management in controlled environment agriculture (under review). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4860822 (2024).

Tzachor, A., Richards, C. E. & Jeen, S. Transforming agrifood production systems and supply chains with digital twins. npj Sci. Food 6, 47 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. Digital twin for aquaponics factory: analysis, opportunities, and research challenges. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 20, 5060–5073 (2024).

Archambault, P. Co-simulation and crop representation for digital twins of controlled environment agriculture systems. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 27th International Conference on Model Driven Engineering Languages and Systems, Association for Computing Machinery: Linz, Austria. 196–199 (IEEE, 2024).

Bashir, A., Ojo, M. & Zahid, A. Real-time estimation of strawberry maturity level and count using CNN in controlled environment agriculture. ASABE Paper No. 2300625 (ASABE, 2023).

Buxbaum, N., Lieth, J. H. & Earles, M. Non-destructive plant biomass monitoring with high spatio-temporal resolution via proximal RGB-D imagery and end-to-end deep learning. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 758818 (2022).

Shasteen, K. C. & Kacira, M. Predictive modeling and computer vision-based decision support to optimize resource use in vertical farms. Sustainability 15, 7812 (2023).

Ojo, M. O. & Zahid, A. Non-destructive biomass estimation for hydroponic lettuce production. ASABE Paper No. 2300776 (ASABE, 2023).

Kim, T., Lee, S. H. & Kim, J. O. A novel shape based plant growth prediction algorithm using deep learning and spatial transformation. IEEE Access 10, 37731–37742 (2022).

Hosoda, Y., Tada, T. & Goto, H. Lettuce fresh weight prediction in a plant factory using plant growth models. IEEE Access 12, 97226–97234 (2024).

Abbasi, R., Martinez, P. & Ahmad, R. Estimation of morphological traits of foliage and effective plant spac ing in NFT-based aquaponics system. Artif. Intell. Agric. 9, 76–88 (2023).

Petropoulou, A. S., et al., Lettuce production in intelligent greenhouses—3D imaging and computer vision for plant spacing decisions. Sensors, 23, 2929 (2023).

Mildenhall, B. et al. Nerf: representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Commun. ACM 65, 99–106 (2021).

Ferrari, A. & Willcox, K. Digital twins in mechanical and aerospace engineering. Nat. Computational Sci. 4, 178–183 (2024).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Foundational research gaps and future directions for digital twins (The National Academies Press, 2024).

Sun, G. et al. Nondestructive determination of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium con tents in greenhouse tomato plants based on multispectral three-dimensi onal imaging. Sensors 19, 5295 (2019).

Sanaeifar, A. et al. Noninvasive early detection of nutrient deficiencies in greenhouse-grown industrial hemp using hyperspectral imaging. Remote Sens. 16, 187 (2024).

Pandey, P. et al. Predicting foliar nutrient concentrations and nutrient deficiencies of hydroponic lettuce using hyperspectral imaging. Biosyst. Eng. 230, 458–469 (2023).

Schober, T., Präger, A. & Graeff-Hönninger, S. A non-destructive method to quantify the nutritional status of Cannabi s sativa L. using in situ hyperspectral imaging in combination with chemometrics. Comput. Electron. Agric. 218, 108656 (2024).

Goldenits, G. et al. Current applications and potential future directions of reinforcement learning-based Digital Twins in agriculture. Smart Agric. Technol. 8, 100512 (2024).

Chen, W. H., Mattson, N. S. & You, F. Intelligent control and energy optimization in controlled environment agriculture via nonlinear model predictive control of semi-closed gree nhouse. Appl. Energy 320, 119334 (2022).

Li, K., Mi, Y. & Zheng, W. An optimal control method for greenhouse climate management considering crop growth’s spatial distribution and energy consumption. Energies 16, 3925 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Study on optimization model control method of light and temperature coordination of greenhouse crops with benefit priority. Comput. Electron. Agric. 210, 107892 (2023).

Pahuja, R., Verma, H. K. & Uddin, M. An intelligent wireless sensor and actuator network system for greenhouse microenvironment control and assessment. J. Biosyst. Eng. 42, 23–43 (2017).

Patil, A. et al. A framework for blockchain based secure smart green house farming. In Advances in Computer Science and Ubiquitous Computing, Vol 474, 1162--1167 (eds: Park, J., Loia, V., Yi, G., Sung, Y.) Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering (Springer, Singapore, 2017).

Lin, J. et al. Blockchain and IoT based food traceability for smart agriculture. In proc. 3rd International Conference on Crowd Science and Engineering (ICCSE'18), 1–6 (2018).

Lin, Y.-P. et al. Blockchain: the evolutionary next step for ICT E-agriculture. Environments, 4, https://doi.org/10.3390/environments4030050 (2017).

Ojo, M. O., Zahid, A. & Masabni, J. G. Estimating hydroponic lettuce phenotypic parameters for efficient resource allocation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 218, 108642 (2024).

Sim, H. S. et al. Prediction of strawberry growth and fruit yield based on environmental and growth data in a greenhouse for soil cultivation with applied autonomous facilities. Horticultural Sci. Technol. 38, 840–849 (2020).

Shasteen, K. C. & Kacira, M. Predictive modeling and computer vision-based decision support to optimize resource use in vertical farms. Sustainability, 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107812 (2023).

Lin, D., Wei, R. & Xu, L. An integrated yield prediction model for greenhouse tomato. Agronomy, 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9120873 (2019).

Zhan, C. et al. Pathways to engineering the phyllosphere microbiome for sustainable crop production. Nat. Food 3, 997–1004 (2022).

Putra, A. M. et al. Growth performance and metabolic changes in lettuce inoculated with plant growth promoting bacteria in a hydroponic system. Sci. Horticulturae 327, 112868 (2024).

Trivedi, P. et al. Plant–microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 607–621 (2020).

Anzalone, A. et al. Soil and soilless tomato cultivation promote different microbial communities that provide new models for future crop interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8820 (2022).

Mei, C. et al. A potential application of Pseudomonas psychrotolerans IALR632 for lettuce growth promotion in hydroponics. Microorganisms 11, 376 (2023).

Amani Machiani, M. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and changes in primary and secondary metabolites. Plants 11, 2183 (2022).

Caser, M. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi modulate the crop performance and metabolic profile of saffron in soilless cultivation. Agronomy 9, 232 (2019).

Schlaeppi, K. et al. Quantitative divergence of the bacterial root microbiota in Arabidopsis thaliana relatives. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 585–592 (2014).

Herrera Paredes, S. et al. Design of synthetic bacterial communities for predictable plant phenotypes. PLOS Biol. 16, e2003962 (2018).

Bulgarelli, D. et al. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 807–838 (2013).

Barnum, C. R., Endelman, B. J. & Shih, P. M. Utilizing plant synthetic biology to improve human health and wellness. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 691462 (2021).

Sirirungruang, S., Markel, K. & Shih, P. M. Plant-based engineering for production of high-valued natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 39, 1492–1509 (2022).

Barnum, C. R. et al. Engineering brassica crops to optimize delivery of bioactive products postcooking. ACS Synth. Biol. 13, 736–744 (2024).

Barnum, C. R. et al. Optimization of heterologous glucoraphanin production in planta. ACS Synth. Biol. 11, 1865–1873 (2022).

Beyer, P. et al. Golden rice: introducing the β-carotene biosynthesis pathway into rice endosperm by genetic engineering to defeat vitamin a deficiency. J. Nutr. 132, 506S–510S (2002).

Lau, W. & Sattely, E. S. Six enzymes from mayapple that complete the biosynthetic pathway to the etoposide aglycone. Science 349, 1224–1228 (2015).

Kumar, S., Kumar, S. & Mohapatra, T. Interaction between macro‐ and micro-nutrients in plants. Front. plant Sci. ume 12, 2021 (2021).

Kwon, C.-T. et al. Rapid customization of Solanaceae fruit crops for urban agriculture. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 182–188 (2020).

Spencer, L. et al. Expanding community engagement and equitable access through all-abilities community gardens. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 55, 833–840 (2023).

Twiss, J. et al. Community gardens: lessons learned from California Healthy Cities and Communities. Am. J. Public Health 93, 1435–1438 (2003).

Apanovich, N. et al. Education for sustainable development: Societal benefits of a community garden project in Tucson, Arizona. Societal Impacts 1, 100011 (2023).

Ponstingel, D. Community gardens as commons through the lens of the diverse economies framework: a case study of Austin, TX. Appl. Geogr. 154, 102945 (2023).

Guo, J., Yanai, S. & Xu, G. Community gardens and psychological well-being among older people in elderly housing with care services: the role of the social environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 94, 102232 (2024).

Limerick, S. et al. Community gardens and the 15-minute city: scenario analysis of garden access in New York City. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 89, 128107 (2023).

Silverberg, C. & Ward, K. Growing labor pains (Greenhouse Product News, 2022).

Kuack, D. What are the production and training issues facing controlled environment agriculture growers? (Urban Ag News, 2018).

UrbanAgNews. Research For Workforce Development In Controlled Environment Ag: What Makes A Successful Indoor Farm Manager? Available from https://urbanagnews.com/blog/news/research-for-workforce-development-in-controlled-environment-ag-what-makes-a-successful-indoor-farm-manager/ (2020).

Gordon-Smith, H. UAE & Egypt will face a significant shortage of skilled labor for climate-smart farms. Here’s why that’s important. Available from: https://agfundernews.com/uae-egypt-will-face-a-significant-shortage-of-skilled-labor-for-climate-smart-farms-heres-why-thats-important (2022).

AgritechTomorrow. Securing our harvest: farm labour and a reduced workforce. Available from: https://www.agritechtomorrow.com/article/2020/06/securing-our-harvest-farm-labour-and-a-reduced-workforce/12207 (2020).

Monnier, E.-C. et al. From teacher to teacher-trainer: a qualitative study exploring factors contributing to a successful train-the-trainer digital education program. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 8, 100518 (2023).

South, P. F. et al. Synthetic glycolate metabolism pathways stimulate crop growth and productivity in the field. Science 363, eaat9077 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Science Foundation grant 1944823 to L.W.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W., L.N., and A.A. designed the concept and overall structure; L.W. wrote the overview, Section “Distributed indoor agriculture”, and conclusion and prepared Figs. 1–3 and 5; G.N. wrote Section “Current CEA technologies”; L.W. and S.V.D.S. wrote section “Integrated decision making based on life cycle analysis”; L.N., M.A.P. and L.W. wrote Section “CEA electricity demand flexibility”; A.Z. and B.G. wrote Section “Digital twins in CEA” and A.Z. prepared Fig. 4; A.A., P.S. and G.N. wrote Section “Microbiome management in CEA ”; P.S. wrote Section “Engineered plants for CEA”; L.W. and L.N. wrote Section “The role of CEA in communities”; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Norford, L., Arkin, A. et al. Finding sustainable, resilient, and scalable solutions for future indoor agriculture. npj Sci. Plants 1, 5 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44383-025-00006-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44383-025-00006-4